User login

Most Common Dermatologic Conditions Encountered by Dermatologists and Nondermatologists

Skin diseases are highly prevalent in the United States, affecting an estimated 1 in 3 Americans at any given time.1,2 In 2009 the direct medical costs associated with skin-related diseases, including health services and prescriptions, was approximately $22 billion; the annual total economic burden was estimated to be closer to $96 billion when factoring in the cost of lost productivity and pay for symptom relief.3,4 Effective and efficient management of skin disease is essential to minimizing cost and morbidity. Nondermatologists traditionally have diagnosed the majority of skin diseases.5,6 In particular, primary care physicians commonly manage dermatologic conditions and often are the first health care providers to encounter patients presenting with skin problems. A predicted shortage of dermatologists will likely contribute to an increase in this trend.7,8 Therefore, it is important to adequately prepare nondermatologists to evaluate and treat the skin conditions that they are most likely to encounter in their scope of practice.

Residents, particularly in primary care specialties, often have opportunities to spend 2 to 4 weeks with a dermatologist to learn about skin diseases; however, the skin conditions most often encountered by dermatologists may differ from those most often encountered by physicians in other specialties. For instance, one study demonstrated a disparity between the most common skin problems seen by dermatologists and internists.9 These dissimilarities should be recognized and addressed in curriculum content. The purpose of this study was to identify and compare the 20 most common dermatologic conditions reported by dermatologists versus those reported by nondermatologists (ie, internists, pediatricians, family physicians, emergency medicine physicians, general surgeons, otolaryngologists) from 2001 to 2010. Data also were analyzed to determine the top 20 conditions referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists as a potential indicator for areas of further improvement within medical education. With this knowledge, we hope educational curricula and self-study can be modified to reflect the current epidemiology of cutaneous diseases, thereby improving patient care.

Methods

Data from 2001 to 2010 were extracted from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), which is an ongoing survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. The NAMCS collects descriptive data regarding ambulatory visits to nonfederal office-based physicians in the United States. Participating physicians are instructed to record information about patient visits for a 1-week period, including patient demographics, insurance status, reason for visit, diagnoses, procedures, therapeutics, and referrals made at that time. Data collected for the NAMCS are entered into a multistage probability sample to produce national estimates. Within dermatology, an average of 118 dermatologists are sampled each year, and over the last 10 years, participation rates have ranged from 47% to 77%.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes were identified to determine the diagnoses that could be classified as dermatologic conditions. Select infectious and neoplastic disorders of the skin and mucous membrane conditions were included as well as the codes for skin diseases. Nondermatologic diagnoses and V codes were not included in the study. Data for all providers were studied to identify outpatient visits associated with the primary diagnosis of a dermatologic condition. Minor diagnoses that were considered to be subsets of major diagnoses were combined to allow better analysis of the data. For example, all tinea infections (ie, dermatophytosis of various sites, dermatomycosis unspecified) were combined into 1 diagnosis referred to as tinea because the recognition and treatment of this disease does not vary tremendously by anatomic location. Visits to dermatologists that listed nonspecific diagnoses and codes (eg, other postsurgical status [V45.89], neoplasm of uncertain behavior site unspecified [238.9]) were assumed to be for dermatologic problems.

Sampling weights were applied to obtain estimates for the number of each diagnosis made nationally. All data analyses were performed using SAS software and linear regression models were generated using SAS PROC SURVEYREG.

Data were analyzed to determine the dermatologic conditions most commonly encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists in emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, internal medicine, otolaryngology, and pediatrics; these specialties include physicians who are known to commonly diagnose and treat skin diseases.10 Data also were analyzed to determine the most common conditions referred to dermatologists for treatment by nondermatologists from the selected specialties. Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the Wake Forest University institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina).

Results

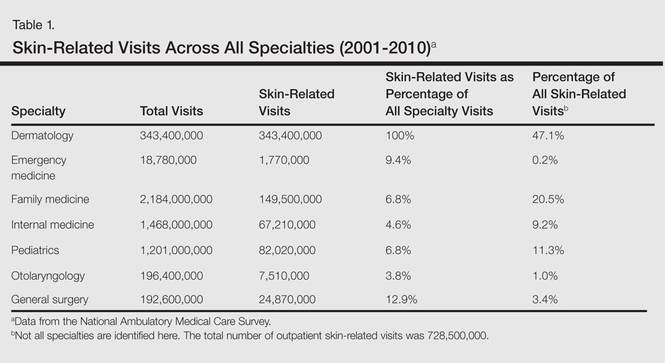

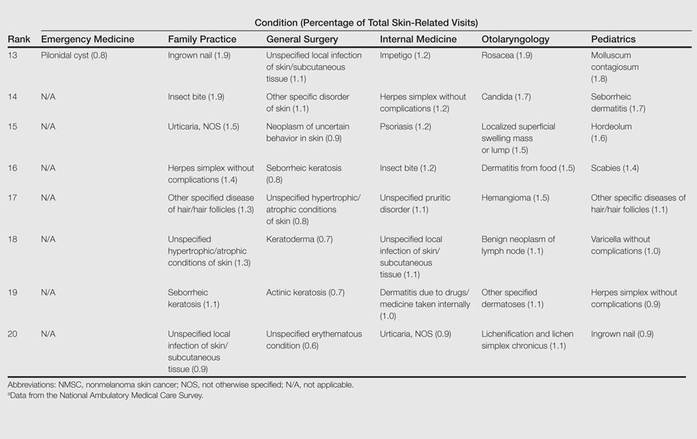

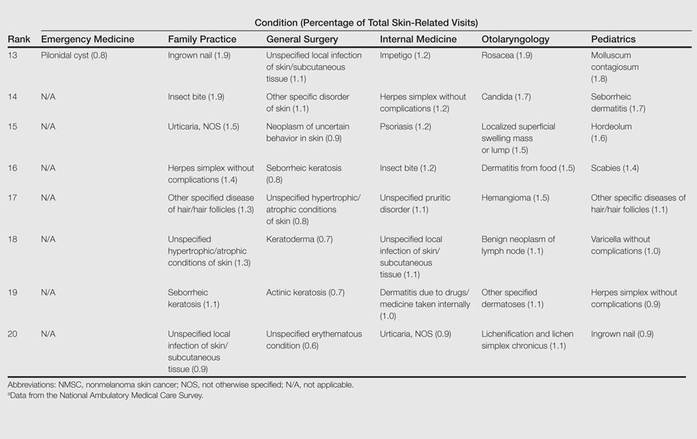

From 2001 to 2010, more than 700 million outpatient visits for skin-related problems were identified, with 676.3 million visits to dermatologists, emergency medicine physicians, family practitioners, general surgeons, internists, otolaryngologists, and pediatricians. More than half (52.9%) of all skin-related visits were addressed by nondermatologists during this time. Among nondermatologists, family practitioners encountered the greatest number of skin diseases (20.5%), followed by pediatricians (11.3%), internists (9.2%), general surgeons (3.4%), otolaryngologists (1.0%), and emergency medicine physicians (0.2%)(Table 1).

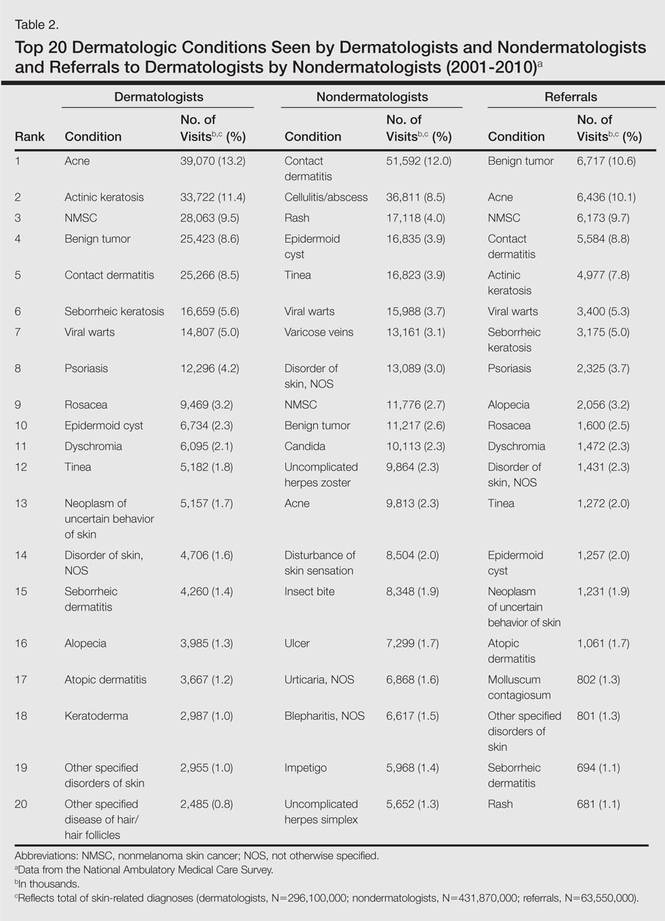

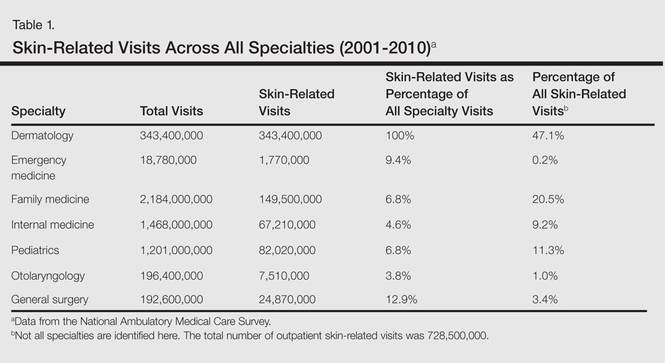

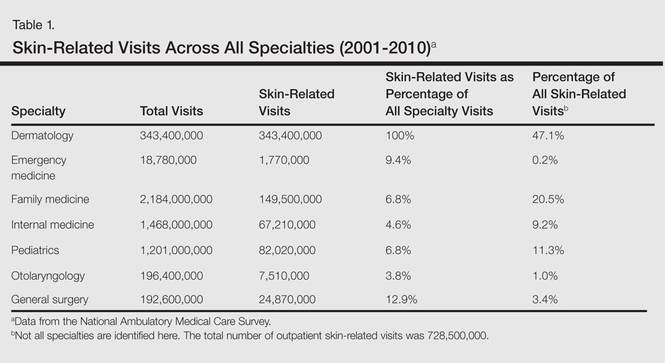

Benign tumors and acne were the most common cutaneous conditions referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists (10.6% and 10.1% of all dermatology referrals, respectively), followed by nonmelanoma skin cancers (9.7%), contact dermatitis (8.8%), and actinic keratosis (7.8%)(Table 2). The top 20 conditions referred to dermatologists accounted for 83.7% of all outpatient referrals to dermatologists.

Among the diseases most frequently reported by nondermatologists, contact dermatitis was the most common (12.0%), with twice the number of visits to nondermatologists for contact dermatitis than to dermatologists (51.6 million vs 25.3 million). In terms of disease categories, infectious skin diseases (ie, bacterial [cellulitis/abscess], viral [warts, herpesvirus], fungal [tinea] and yeast [candida] etiologies) were the most common dermatologic conditions reported by nondermatologists (Table 2).

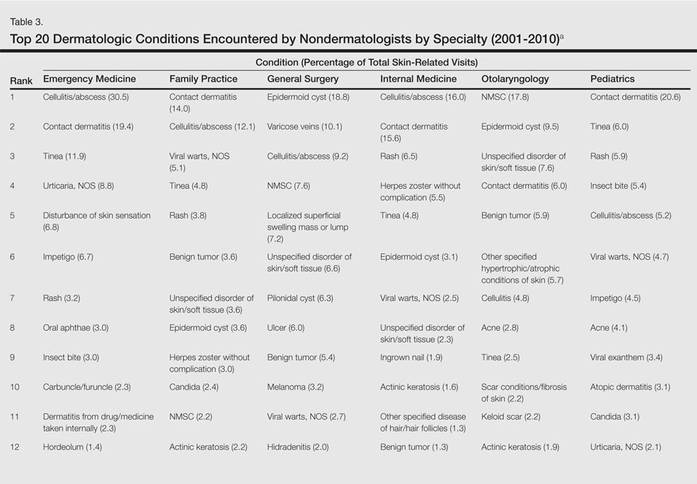

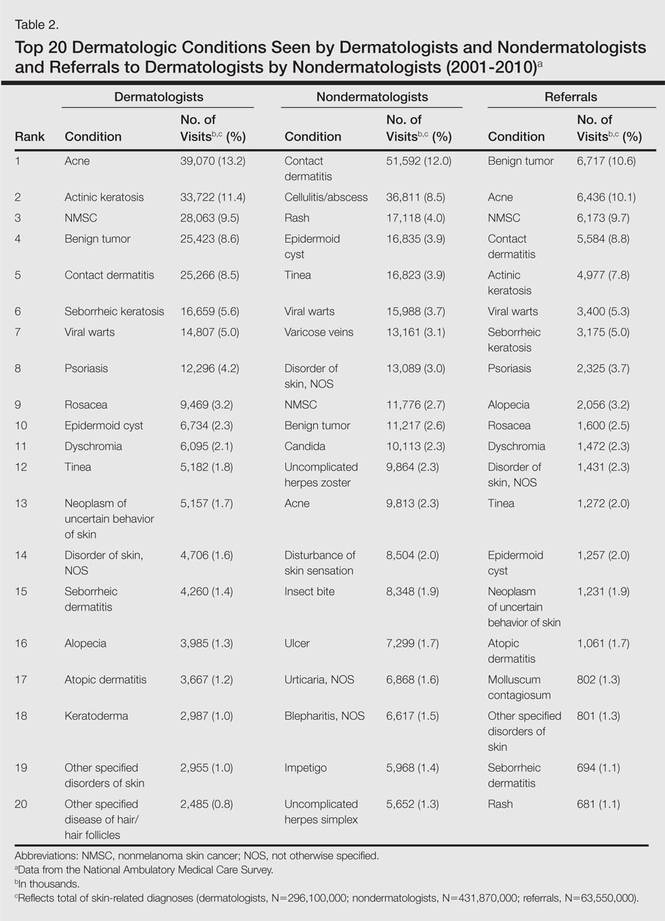

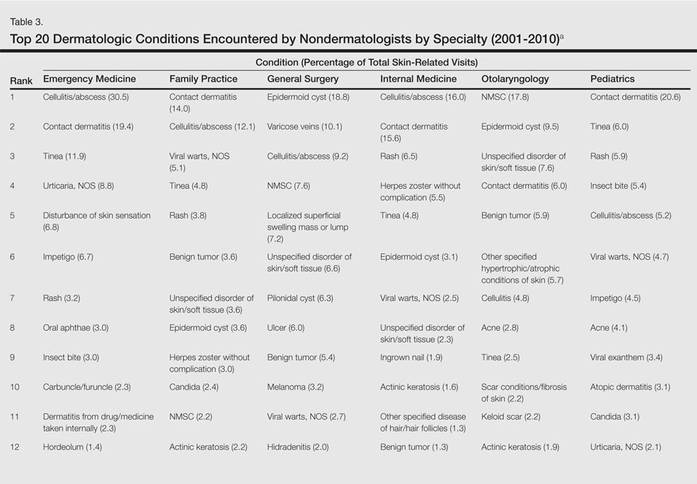

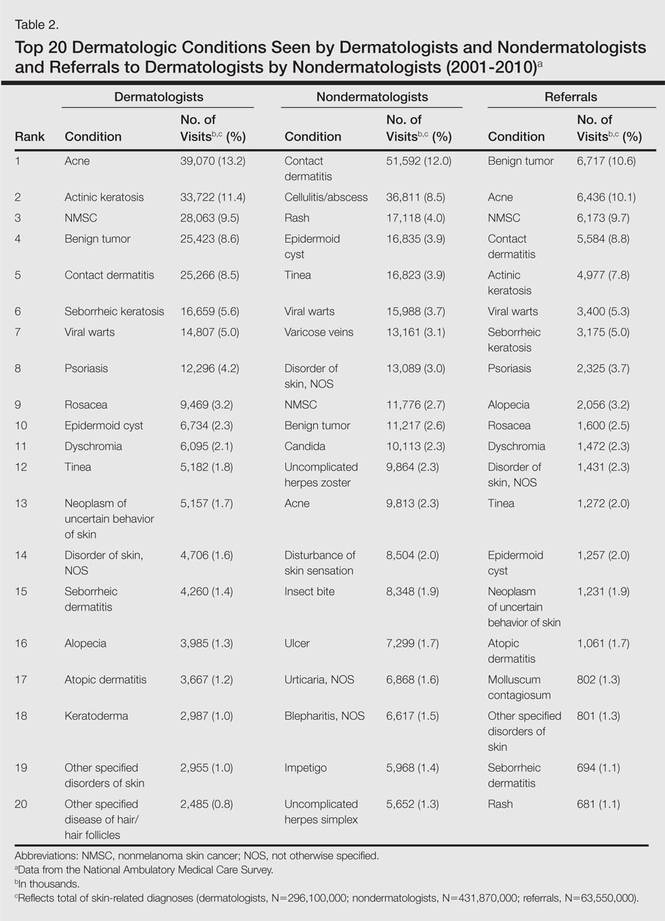

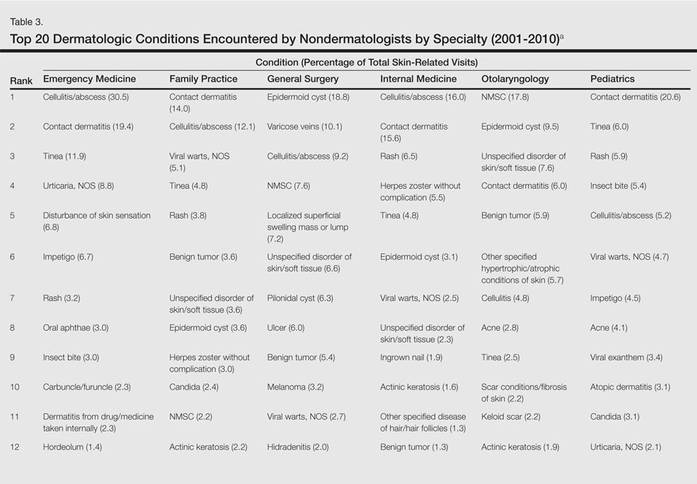

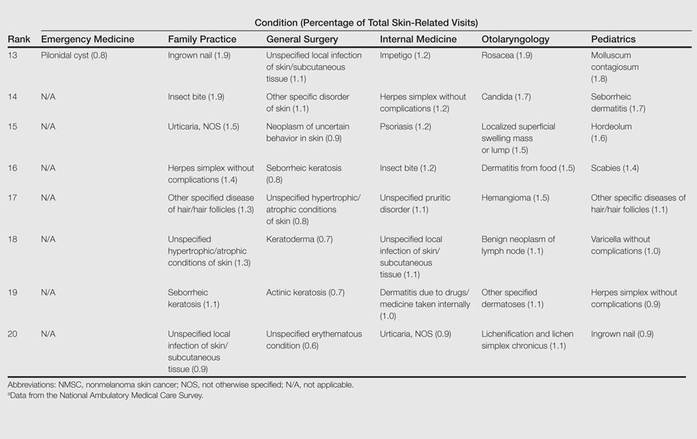

The top 20 dermatologic conditions reported by dermatologists accounted for 85.4% of all diagnoses made by dermatologists. Diseases that were among the top 20 conditions encountered by dermatologists but were not among the top 20 for nondermatologists included actinic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia, rosacea, dyschromia, seborrheic dermatitis, follicular disease, and neoplasm of uncertain behavior of skin. Additionally, 5 of the top 20 conditions encountered by dermatologists also were among the top 20 for only 1 individual nondermatologic specialty; these included atopic dermatitis (pediatrics), seborrheic dermatitis (pediatrics), psoriasis (internal medicine), rosacea (otolaryngology), and keratoderma (general surgery). Seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and rosacea also were among the top 20 conditions most commonly referred to dermatologists for treatment by nondermatologists. Table 3 shows the top 20 dermatologic conditions encountered by nondermatologists by comparison.

Comment

According to NAMCS data from 2001 to 2010, visits to nondermatologists accounted for more than half of total outpatient visits for cutaneous diseases in the United States, whereas visits to dermatologists accounted for 47.1%. These findings are consistent with historical data indicating that 30% to 40% of skin-related visits are to dermatologists, and the majority of patients with skin disease are diagnosed by nondermatologists.5,6

Past data indicate that most visits to dermatologists were for evaluation of acne, infections, psoriasis, and neoplasms, whereas most visits to nondermatologists were for evaluation of epidermoid cysts, impetigo, plant dermatitis, cellulitis, and diaper rash.9 Over the last 10 years, acne has been more commonly encountered by nondermatologists, especially pediatricians. Additionally, infectious etiologies have been seen in larger volume by nondermatologists.9 Together, infectious cutaneous conditions make up nearly one-fourth of dermatologic encounters by emergency medicine physicians, internists, and family practitioners but are not within the top 20 diagnoses referred to dermatologists, which suggests that uncomplicated cases of cellulitis, herpes zoster, and other skin-related infections are largely managed by nondermatologists.5,6 Contact dermatitis, often caused by specific allergens such as detergents, solvents, and topical products, was one of the most common reported dermatologic encounters among dermatologists and nondermatologists and also was the fourth most common condition referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists for treatment; however, there may be an element of overuse of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code, as any presumed contact dermatitis of unspecified cause can be reported under 692.9 defined as contact dermatitis and other eczema, unspecified cause. The high rate of referrals to dermatologists by nondermatologists may be for patch testing and further management. Additionally, there are no specific codes for allergic or irritant dermatitis, thus these diseases may be lumped together.

Although nearly half of all dermatologic encounters were seen by nondermatologists, dermatologists see a much larger proportion of patients with skin disease than nondermatologists and nondermatologists often have limited exposure to the field of dermatology during residency training. Studies have demonstrated differences in the abilities of dermatologists and nondermatologists to correctly diagnose common cutaneous diseases, which unsurprisingly revealed greater diagnostic accuracy demonstrated by dermatologists.11-16 The increase in acne and skin-related infections reported by nondermatologists is consistent with possible efforts to increase formal training in frequently encountered skin diseases. In one study evaluating the impact of a formal 3-week dermatology curriculum on an internal medicine department, internists demonstrated 100% accuracy in the diagnosis of acne and herpes zoster in contrast to 29% for tinea and 12% for lichen planus.5,6

The current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education guidelines place little emphasis on exposure to dermatology training during residency for internists and pediatricians, as this training is not a required component of these programs.17 Two core problems with current training regarding the evaluation and management of cutaneous disease are minimal exposure to dermatologic conditions in medical school and residency and lack of consensus on the core topics that should be taught to nondermatologists.18 Exposure to dermatologic conditions through rotations in medical school has been shown to increase residents’ self-reported confidence in diagnosing and treating alopecia, cutaneous drug eruptions, warts, acne, rosacea, nonmelanoma skin cancers, sun damage, psoriasis, seborrhea, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis; however, the majority of primary care residents surveyed still felt that this exposure in medical school was inadequate.19

In creating a core curriculum for dermatology training for nondermatologists, it is important to consider the dermatologic conditions that are most frequently encountered by these specialties. Our study revealed that the most commonly encountered dermatologic conditions differ among dermatologists and nondermatologists, with a fair degree of variation even among individual specialties. Failure to recognize these discrepancies has likely contributed to the challenges faced by nondermatologists in the diagnosis and management of dermatologic disease. In this study, contact dermatitis, epidermoid cysts, and skin infections were the most common dermatologic conditions encountered by nondermatologists and also were among the top skin diseases referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists. This finding suggests that nondermatologists are able to identify these conditions but have a tendency to refer approximately 10% of these patients to dermatology for further management. Clinical evaluation and medical management of these cutaneous diseases may be an important area of focus for medical school curricula, as the treatment of these diseases is within the capabilities of the nondermatologist. For example, initial management of dermatitis requires determination of the type of dermatitis (ie, essential, contact, atopic, seborrheic, stasis) and selection of an appropriate topical steroid, with referral to a dermatologist needed for questionable or refractory cases. Although a curriculum cannot be built solely on a list of the top 20 diagnoses provided here, these data may serve as a preliminary platform for medical school dermatology curriculum design. The curriculum also should include serious skin diseases, such as melanoma and severe drug eruptions. Although these conditions are less commonly encountered by nondermatologists, missed diagnosis and/or improper management can be life threatening.

The use of NAMCS data presents a few limitations. For instance, these data only represent outpatient management of skin disease. There is the potential for misdiagnosis and coding errors by the reporting physicians. The volume of data (ie, billions of office visits) prevents verification of diagnostic accuracy. The coding system requires physicians to give a diagnosis but does not provide any means by which to determine the physician’s confidence in that diagnosis. There is no code for “uncertain” or “diagnosis not determined.” Additionally, an “unspecified” diagnosis may reflect uncertainty or may simply imply that no other code accurately described the condition. Despite these limitations, the NAMCS database is a large, nationally representative survey of actual patient visits and represents some of the best data available for a study such as ours.

Conclusion

This study provides an important analysis of the most common outpatient dermatologic conditions encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists of various specialties and offers a foundation from which to construct curricula for dermatology training tailored to individual specialties based on their needs. In the future, identification of the most common inpatient dermatologic conditions managed by each specialty also may benefit curriculum design.

- Thorpe KE, Florence CS, Joski P. Which medical conditions account for the rise in health care spending? Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;(suppl web exclusives):W4-437-445.

- Johnson ML. Defining the burden of skin disease in the United States—a historical perspective. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:108-110.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical expenditure panel survey. US Department of Health & Human Services Web site. http://meps.ahrq.gov. Accessed November 17, 2014.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500.

- Johnson ML. On teaching dermatology to nondermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:850-852.

- Ramsay DL, Weary PE. Primary care in dermatology: whose role should it be? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:1005-1008.

- Kimball AB, Resneck JS Jr. The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:741-745.

- Resneck JS Jr, Kimball AB. Who else is providing care in dermatology practices? trends in the use of nonphysician clinicians. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:211-216.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, McConnell RC. Most common dermatologic problems identified by internists, 1990-1994. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:726-730.

- Ahn CS, Davis SA, Debade TS, et al. Noncosmetic skin-related procedures performed in the United States: an analysis of national ambulatory medical care survey data from 1995 to 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1912-1921.

- Antic M, Conen D, Itin PH. Teaching effects of dermatological consultations on nondermatologists in the field of internal medicine. a study of 1290 inpatients. Dermatology. 2004;208:32-37.

- Federman DG, Concato J, Kirsner RS. Comparison of dermatologic diagnoses by primary care practitioners and dermatologists. a review of the literature. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:170-172.

- Fleischer AB Jr, Herbert CR, Feldman SR, et al. Diagnosis of skin disease by nondermatologists. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:1149-1156.

- Kirsner RS, Federman DG. Lack of correlation between internists’ ability in dermatology and their patterns of treating patients with skin disease. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1043-1046.

- McCarthy GM, Lamb GC, Russell TJ, et al. Primary care-based dermatology practice: internists need more training. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:52-56.

- Sellheyer K, Bergfeld WF. A retrospective biopsy study of the clinical diagnostic accuracy of common skin diseases by different specialties compared with dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:823-830.

- Medical specialties. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Web site. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/368ProgramandInstitutionalGuidelines/MedicalAccreditation.aspx. Accessed November 17, 2014.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.

Skin diseases are highly prevalent in the United States, affecting an estimated 1 in 3 Americans at any given time.1,2 In 2009 the direct medical costs associated with skin-related diseases, including health services and prescriptions, was approximately $22 billion; the annual total economic burden was estimated to be closer to $96 billion when factoring in the cost of lost productivity and pay for symptom relief.3,4 Effective and efficient management of skin disease is essential to minimizing cost and morbidity. Nondermatologists traditionally have diagnosed the majority of skin diseases.5,6 In particular, primary care physicians commonly manage dermatologic conditions and often are the first health care providers to encounter patients presenting with skin problems. A predicted shortage of dermatologists will likely contribute to an increase in this trend.7,8 Therefore, it is important to adequately prepare nondermatologists to evaluate and treat the skin conditions that they are most likely to encounter in their scope of practice.

Residents, particularly in primary care specialties, often have opportunities to spend 2 to 4 weeks with a dermatologist to learn about skin diseases; however, the skin conditions most often encountered by dermatologists may differ from those most often encountered by physicians in other specialties. For instance, one study demonstrated a disparity between the most common skin problems seen by dermatologists and internists.9 These dissimilarities should be recognized and addressed in curriculum content. The purpose of this study was to identify and compare the 20 most common dermatologic conditions reported by dermatologists versus those reported by nondermatologists (ie, internists, pediatricians, family physicians, emergency medicine physicians, general surgeons, otolaryngologists) from 2001 to 2010. Data also were analyzed to determine the top 20 conditions referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists as a potential indicator for areas of further improvement within medical education. With this knowledge, we hope educational curricula and self-study can be modified to reflect the current epidemiology of cutaneous diseases, thereby improving patient care.

Methods

Data from 2001 to 2010 were extracted from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), which is an ongoing survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. The NAMCS collects descriptive data regarding ambulatory visits to nonfederal office-based physicians in the United States. Participating physicians are instructed to record information about patient visits for a 1-week period, including patient demographics, insurance status, reason for visit, diagnoses, procedures, therapeutics, and referrals made at that time. Data collected for the NAMCS are entered into a multistage probability sample to produce national estimates. Within dermatology, an average of 118 dermatologists are sampled each year, and over the last 10 years, participation rates have ranged from 47% to 77%.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes were identified to determine the diagnoses that could be classified as dermatologic conditions. Select infectious and neoplastic disorders of the skin and mucous membrane conditions were included as well as the codes for skin diseases. Nondermatologic diagnoses and V codes were not included in the study. Data for all providers were studied to identify outpatient visits associated with the primary diagnosis of a dermatologic condition. Minor diagnoses that were considered to be subsets of major diagnoses were combined to allow better analysis of the data. For example, all tinea infections (ie, dermatophytosis of various sites, dermatomycosis unspecified) were combined into 1 diagnosis referred to as tinea because the recognition and treatment of this disease does not vary tremendously by anatomic location. Visits to dermatologists that listed nonspecific diagnoses and codes (eg, other postsurgical status [V45.89], neoplasm of uncertain behavior site unspecified [238.9]) were assumed to be for dermatologic problems.

Sampling weights were applied to obtain estimates for the number of each diagnosis made nationally. All data analyses were performed using SAS software and linear regression models were generated using SAS PROC SURVEYREG.

Data were analyzed to determine the dermatologic conditions most commonly encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists in emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, internal medicine, otolaryngology, and pediatrics; these specialties include physicians who are known to commonly diagnose and treat skin diseases.10 Data also were analyzed to determine the most common conditions referred to dermatologists for treatment by nondermatologists from the selected specialties. Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the Wake Forest University institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina).

Results

From 2001 to 2010, more than 700 million outpatient visits for skin-related problems were identified, with 676.3 million visits to dermatologists, emergency medicine physicians, family practitioners, general surgeons, internists, otolaryngologists, and pediatricians. More than half (52.9%) of all skin-related visits were addressed by nondermatologists during this time. Among nondermatologists, family practitioners encountered the greatest number of skin diseases (20.5%), followed by pediatricians (11.3%), internists (9.2%), general surgeons (3.4%), otolaryngologists (1.0%), and emergency medicine physicians (0.2%)(Table 1).

Benign tumors and acne were the most common cutaneous conditions referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists (10.6% and 10.1% of all dermatology referrals, respectively), followed by nonmelanoma skin cancers (9.7%), contact dermatitis (8.8%), and actinic keratosis (7.8%)(Table 2). The top 20 conditions referred to dermatologists accounted for 83.7% of all outpatient referrals to dermatologists.

Among the diseases most frequently reported by nondermatologists, contact dermatitis was the most common (12.0%), with twice the number of visits to nondermatologists for contact dermatitis than to dermatologists (51.6 million vs 25.3 million). In terms of disease categories, infectious skin diseases (ie, bacterial [cellulitis/abscess], viral [warts, herpesvirus], fungal [tinea] and yeast [candida] etiologies) were the most common dermatologic conditions reported by nondermatologists (Table 2).

The top 20 dermatologic conditions reported by dermatologists accounted for 85.4% of all diagnoses made by dermatologists. Diseases that were among the top 20 conditions encountered by dermatologists but were not among the top 20 for nondermatologists included actinic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia, rosacea, dyschromia, seborrheic dermatitis, follicular disease, and neoplasm of uncertain behavior of skin. Additionally, 5 of the top 20 conditions encountered by dermatologists also were among the top 20 for only 1 individual nondermatologic specialty; these included atopic dermatitis (pediatrics), seborrheic dermatitis (pediatrics), psoriasis (internal medicine), rosacea (otolaryngology), and keratoderma (general surgery). Seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and rosacea also were among the top 20 conditions most commonly referred to dermatologists for treatment by nondermatologists. Table 3 shows the top 20 dermatologic conditions encountered by nondermatologists by comparison.

Comment

According to NAMCS data from 2001 to 2010, visits to nondermatologists accounted for more than half of total outpatient visits for cutaneous diseases in the United States, whereas visits to dermatologists accounted for 47.1%. These findings are consistent with historical data indicating that 30% to 40% of skin-related visits are to dermatologists, and the majority of patients with skin disease are diagnosed by nondermatologists.5,6

Past data indicate that most visits to dermatologists were for evaluation of acne, infections, psoriasis, and neoplasms, whereas most visits to nondermatologists were for evaluation of epidermoid cysts, impetigo, plant dermatitis, cellulitis, and diaper rash.9 Over the last 10 years, acne has been more commonly encountered by nondermatologists, especially pediatricians. Additionally, infectious etiologies have been seen in larger volume by nondermatologists.9 Together, infectious cutaneous conditions make up nearly one-fourth of dermatologic encounters by emergency medicine physicians, internists, and family practitioners but are not within the top 20 diagnoses referred to dermatologists, which suggests that uncomplicated cases of cellulitis, herpes zoster, and other skin-related infections are largely managed by nondermatologists.5,6 Contact dermatitis, often caused by specific allergens such as detergents, solvents, and topical products, was one of the most common reported dermatologic encounters among dermatologists and nondermatologists and also was the fourth most common condition referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists for treatment; however, there may be an element of overuse of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code, as any presumed contact dermatitis of unspecified cause can be reported under 692.9 defined as contact dermatitis and other eczema, unspecified cause. The high rate of referrals to dermatologists by nondermatologists may be for patch testing and further management. Additionally, there are no specific codes for allergic or irritant dermatitis, thus these diseases may be lumped together.

Although nearly half of all dermatologic encounters were seen by nondermatologists, dermatologists see a much larger proportion of patients with skin disease than nondermatologists and nondermatologists often have limited exposure to the field of dermatology during residency training. Studies have demonstrated differences in the abilities of dermatologists and nondermatologists to correctly diagnose common cutaneous diseases, which unsurprisingly revealed greater diagnostic accuracy demonstrated by dermatologists.11-16 The increase in acne and skin-related infections reported by nondermatologists is consistent with possible efforts to increase formal training in frequently encountered skin diseases. In one study evaluating the impact of a formal 3-week dermatology curriculum on an internal medicine department, internists demonstrated 100% accuracy in the diagnosis of acne and herpes zoster in contrast to 29% for tinea and 12% for lichen planus.5,6

The current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education guidelines place little emphasis on exposure to dermatology training during residency for internists and pediatricians, as this training is not a required component of these programs.17 Two core problems with current training regarding the evaluation and management of cutaneous disease are minimal exposure to dermatologic conditions in medical school and residency and lack of consensus on the core topics that should be taught to nondermatologists.18 Exposure to dermatologic conditions through rotations in medical school has been shown to increase residents’ self-reported confidence in diagnosing and treating alopecia, cutaneous drug eruptions, warts, acne, rosacea, nonmelanoma skin cancers, sun damage, psoriasis, seborrhea, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis; however, the majority of primary care residents surveyed still felt that this exposure in medical school was inadequate.19

In creating a core curriculum for dermatology training for nondermatologists, it is important to consider the dermatologic conditions that are most frequently encountered by these specialties. Our study revealed that the most commonly encountered dermatologic conditions differ among dermatologists and nondermatologists, with a fair degree of variation even among individual specialties. Failure to recognize these discrepancies has likely contributed to the challenges faced by nondermatologists in the diagnosis and management of dermatologic disease. In this study, contact dermatitis, epidermoid cysts, and skin infections were the most common dermatologic conditions encountered by nondermatologists and also were among the top skin diseases referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists. This finding suggests that nondermatologists are able to identify these conditions but have a tendency to refer approximately 10% of these patients to dermatology for further management. Clinical evaluation and medical management of these cutaneous diseases may be an important area of focus for medical school curricula, as the treatment of these diseases is within the capabilities of the nondermatologist. For example, initial management of dermatitis requires determination of the type of dermatitis (ie, essential, contact, atopic, seborrheic, stasis) and selection of an appropriate topical steroid, with referral to a dermatologist needed for questionable or refractory cases. Although a curriculum cannot be built solely on a list of the top 20 diagnoses provided here, these data may serve as a preliminary platform for medical school dermatology curriculum design. The curriculum also should include serious skin diseases, such as melanoma and severe drug eruptions. Although these conditions are less commonly encountered by nondermatologists, missed diagnosis and/or improper management can be life threatening.

The use of NAMCS data presents a few limitations. For instance, these data only represent outpatient management of skin disease. There is the potential for misdiagnosis and coding errors by the reporting physicians. The volume of data (ie, billions of office visits) prevents verification of diagnostic accuracy. The coding system requires physicians to give a diagnosis but does not provide any means by which to determine the physician’s confidence in that diagnosis. There is no code for “uncertain” or “diagnosis not determined.” Additionally, an “unspecified” diagnosis may reflect uncertainty or may simply imply that no other code accurately described the condition. Despite these limitations, the NAMCS database is a large, nationally representative survey of actual patient visits and represents some of the best data available for a study such as ours.

Conclusion

This study provides an important analysis of the most common outpatient dermatologic conditions encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists of various specialties and offers a foundation from which to construct curricula for dermatology training tailored to individual specialties based on their needs. In the future, identification of the most common inpatient dermatologic conditions managed by each specialty also may benefit curriculum design.

Skin diseases are highly prevalent in the United States, affecting an estimated 1 in 3 Americans at any given time.1,2 In 2009 the direct medical costs associated with skin-related diseases, including health services and prescriptions, was approximately $22 billion; the annual total economic burden was estimated to be closer to $96 billion when factoring in the cost of lost productivity and pay for symptom relief.3,4 Effective and efficient management of skin disease is essential to minimizing cost and morbidity. Nondermatologists traditionally have diagnosed the majority of skin diseases.5,6 In particular, primary care physicians commonly manage dermatologic conditions and often are the first health care providers to encounter patients presenting with skin problems. A predicted shortage of dermatologists will likely contribute to an increase in this trend.7,8 Therefore, it is important to adequately prepare nondermatologists to evaluate and treat the skin conditions that they are most likely to encounter in their scope of practice.

Residents, particularly in primary care specialties, often have opportunities to spend 2 to 4 weeks with a dermatologist to learn about skin diseases; however, the skin conditions most often encountered by dermatologists may differ from those most often encountered by physicians in other specialties. For instance, one study demonstrated a disparity between the most common skin problems seen by dermatologists and internists.9 These dissimilarities should be recognized and addressed in curriculum content. The purpose of this study was to identify and compare the 20 most common dermatologic conditions reported by dermatologists versus those reported by nondermatologists (ie, internists, pediatricians, family physicians, emergency medicine physicians, general surgeons, otolaryngologists) from 2001 to 2010. Data also were analyzed to determine the top 20 conditions referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists as a potential indicator for areas of further improvement within medical education. With this knowledge, we hope educational curricula and self-study can be modified to reflect the current epidemiology of cutaneous diseases, thereby improving patient care.

Methods

Data from 2001 to 2010 were extracted from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), which is an ongoing survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. The NAMCS collects descriptive data regarding ambulatory visits to nonfederal office-based physicians in the United States. Participating physicians are instructed to record information about patient visits for a 1-week period, including patient demographics, insurance status, reason for visit, diagnoses, procedures, therapeutics, and referrals made at that time. Data collected for the NAMCS are entered into a multistage probability sample to produce national estimates. Within dermatology, an average of 118 dermatologists are sampled each year, and over the last 10 years, participation rates have ranged from 47% to 77%.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes were identified to determine the diagnoses that could be classified as dermatologic conditions. Select infectious and neoplastic disorders of the skin and mucous membrane conditions were included as well as the codes for skin diseases. Nondermatologic diagnoses and V codes were not included in the study. Data for all providers were studied to identify outpatient visits associated with the primary diagnosis of a dermatologic condition. Minor diagnoses that were considered to be subsets of major diagnoses were combined to allow better analysis of the data. For example, all tinea infections (ie, dermatophytosis of various sites, dermatomycosis unspecified) were combined into 1 diagnosis referred to as tinea because the recognition and treatment of this disease does not vary tremendously by anatomic location. Visits to dermatologists that listed nonspecific diagnoses and codes (eg, other postsurgical status [V45.89], neoplasm of uncertain behavior site unspecified [238.9]) were assumed to be for dermatologic problems.

Sampling weights were applied to obtain estimates for the number of each diagnosis made nationally. All data analyses were performed using SAS software and linear regression models were generated using SAS PROC SURVEYREG.

Data were analyzed to determine the dermatologic conditions most commonly encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists in emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, internal medicine, otolaryngology, and pediatrics; these specialties include physicians who are known to commonly diagnose and treat skin diseases.10 Data also were analyzed to determine the most common conditions referred to dermatologists for treatment by nondermatologists from the selected specialties. Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the Wake Forest University institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina).

Results

From 2001 to 2010, more than 700 million outpatient visits for skin-related problems were identified, with 676.3 million visits to dermatologists, emergency medicine physicians, family practitioners, general surgeons, internists, otolaryngologists, and pediatricians. More than half (52.9%) of all skin-related visits were addressed by nondermatologists during this time. Among nondermatologists, family practitioners encountered the greatest number of skin diseases (20.5%), followed by pediatricians (11.3%), internists (9.2%), general surgeons (3.4%), otolaryngologists (1.0%), and emergency medicine physicians (0.2%)(Table 1).

Benign tumors and acne were the most common cutaneous conditions referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists (10.6% and 10.1% of all dermatology referrals, respectively), followed by nonmelanoma skin cancers (9.7%), contact dermatitis (8.8%), and actinic keratosis (7.8%)(Table 2). The top 20 conditions referred to dermatologists accounted for 83.7% of all outpatient referrals to dermatologists.

Among the diseases most frequently reported by nondermatologists, contact dermatitis was the most common (12.0%), with twice the number of visits to nondermatologists for contact dermatitis than to dermatologists (51.6 million vs 25.3 million). In terms of disease categories, infectious skin diseases (ie, bacterial [cellulitis/abscess], viral [warts, herpesvirus], fungal [tinea] and yeast [candida] etiologies) were the most common dermatologic conditions reported by nondermatologists (Table 2).

The top 20 dermatologic conditions reported by dermatologists accounted for 85.4% of all diagnoses made by dermatologists. Diseases that were among the top 20 conditions encountered by dermatologists but were not among the top 20 for nondermatologists included actinic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia, rosacea, dyschromia, seborrheic dermatitis, follicular disease, and neoplasm of uncertain behavior of skin. Additionally, 5 of the top 20 conditions encountered by dermatologists also were among the top 20 for only 1 individual nondermatologic specialty; these included atopic dermatitis (pediatrics), seborrheic dermatitis (pediatrics), psoriasis (internal medicine), rosacea (otolaryngology), and keratoderma (general surgery). Seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and rosacea also were among the top 20 conditions most commonly referred to dermatologists for treatment by nondermatologists. Table 3 shows the top 20 dermatologic conditions encountered by nondermatologists by comparison.

Comment

According to NAMCS data from 2001 to 2010, visits to nondermatologists accounted for more than half of total outpatient visits for cutaneous diseases in the United States, whereas visits to dermatologists accounted for 47.1%. These findings are consistent with historical data indicating that 30% to 40% of skin-related visits are to dermatologists, and the majority of patients with skin disease are diagnosed by nondermatologists.5,6

Past data indicate that most visits to dermatologists were for evaluation of acne, infections, psoriasis, and neoplasms, whereas most visits to nondermatologists were for evaluation of epidermoid cysts, impetigo, plant dermatitis, cellulitis, and diaper rash.9 Over the last 10 years, acne has been more commonly encountered by nondermatologists, especially pediatricians. Additionally, infectious etiologies have been seen in larger volume by nondermatologists.9 Together, infectious cutaneous conditions make up nearly one-fourth of dermatologic encounters by emergency medicine physicians, internists, and family practitioners but are not within the top 20 diagnoses referred to dermatologists, which suggests that uncomplicated cases of cellulitis, herpes zoster, and other skin-related infections are largely managed by nondermatologists.5,6 Contact dermatitis, often caused by specific allergens such as detergents, solvents, and topical products, was one of the most common reported dermatologic encounters among dermatologists and nondermatologists and also was the fourth most common condition referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists for treatment; however, there may be an element of overuse of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code, as any presumed contact dermatitis of unspecified cause can be reported under 692.9 defined as contact dermatitis and other eczema, unspecified cause. The high rate of referrals to dermatologists by nondermatologists may be for patch testing and further management. Additionally, there are no specific codes for allergic or irritant dermatitis, thus these diseases may be lumped together.

Although nearly half of all dermatologic encounters were seen by nondermatologists, dermatologists see a much larger proportion of patients with skin disease than nondermatologists and nondermatologists often have limited exposure to the field of dermatology during residency training. Studies have demonstrated differences in the abilities of dermatologists and nondermatologists to correctly diagnose common cutaneous diseases, which unsurprisingly revealed greater diagnostic accuracy demonstrated by dermatologists.11-16 The increase in acne and skin-related infections reported by nondermatologists is consistent with possible efforts to increase formal training in frequently encountered skin diseases. In one study evaluating the impact of a formal 3-week dermatology curriculum on an internal medicine department, internists demonstrated 100% accuracy in the diagnosis of acne and herpes zoster in contrast to 29% for tinea and 12% for lichen planus.5,6

The current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education guidelines place little emphasis on exposure to dermatology training during residency for internists and pediatricians, as this training is not a required component of these programs.17 Two core problems with current training regarding the evaluation and management of cutaneous disease are minimal exposure to dermatologic conditions in medical school and residency and lack of consensus on the core topics that should be taught to nondermatologists.18 Exposure to dermatologic conditions through rotations in medical school has been shown to increase residents’ self-reported confidence in diagnosing and treating alopecia, cutaneous drug eruptions, warts, acne, rosacea, nonmelanoma skin cancers, sun damage, psoriasis, seborrhea, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis; however, the majority of primary care residents surveyed still felt that this exposure in medical school was inadequate.19

In creating a core curriculum for dermatology training for nondermatologists, it is important to consider the dermatologic conditions that are most frequently encountered by these specialties. Our study revealed that the most commonly encountered dermatologic conditions differ among dermatologists and nondermatologists, with a fair degree of variation even among individual specialties. Failure to recognize these discrepancies has likely contributed to the challenges faced by nondermatologists in the diagnosis and management of dermatologic disease. In this study, contact dermatitis, epidermoid cysts, and skin infections were the most common dermatologic conditions encountered by nondermatologists and also were among the top skin diseases referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists. This finding suggests that nondermatologists are able to identify these conditions but have a tendency to refer approximately 10% of these patients to dermatology for further management. Clinical evaluation and medical management of these cutaneous diseases may be an important area of focus for medical school curricula, as the treatment of these diseases is within the capabilities of the nondermatologist. For example, initial management of dermatitis requires determination of the type of dermatitis (ie, essential, contact, atopic, seborrheic, stasis) and selection of an appropriate topical steroid, with referral to a dermatologist needed for questionable or refractory cases. Although a curriculum cannot be built solely on a list of the top 20 diagnoses provided here, these data may serve as a preliminary platform for medical school dermatology curriculum design. The curriculum also should include serious skin diseases, such as melanoma and severe drug eruptions. Although these conditions are less commonly encountered by nondermatologists, missed diagnosis and/or improper management can be life threatening.

The use of NAMCS data presents a few limitations. For instance, these data only represent outpatient management of skin disease. There is the potential for misdiagnosis and coding errors by the reporting physicians. The volume of data (ie, billions of office visits) prevents verification of diagnostic accuracy. The coding system requires physicians to give a diagnosis but does not provide any means by which to determine the physician’s confidence in that diagnosis. There is no code for “uncertain” or “diagnosis not determined.” Additionally, an “unspecified” diagnosis may reflect uncertainty or may simply imply that no other code accurately described the condition. Despite these limitations, the NAMCS database is a large, nationally representative survey of actual patient visits and represents some of the best data available for a study such as ours.

Conclusion

This study provides an important analysis of the most common outpatient dermatologic conditions encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists of various specialties and offers a foundation from which to construct curricula for dermatology training tailored to individual specialties based on their needs. In the future, identification of the most common inpatient dermatologic conditions managed by each specialty also may benefit curriculum design.

- Thorpe KE, Florence CS, Joski P. Which medical conditions account for the rise in health care spending? Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;(suppl web exclusives):W4-437-445.

- Johnson ML. Defining the burden of skin disease in the United States—a historical perspective. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:108-110.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical expenditure panel survey. US Department of Health & Human Services Web site. http://meps.ahrq.gov. Accessed November 17, 2014.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500.

- Johnson ML. On teaching dermatology to nondermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:850-852.

- Ramsay DL, Weary PE. Primary care in dermatology: whose role should it be? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:1005-1008.

- Kimball AB, Resneck JS Jr. The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:741-745.

- Resneck JS Jr, Kimball AB. Who else is providing care in dermatology practices? trends in the use of nonphysician clinicians. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:211-216.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, McConnell RC. Most common dermatologic problems identified by internists, 1990-1994. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:726-730.

- Ahn CS, Davis SA, Debade TS, et al. Noncosmetic skin-related procedures performed in the United States: an analysis of national ambulatory medical care survey data from 1995 to 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1912-1921.

- Antic M, Conen D, Itin PH. Teaching effects of dermatological consultations on nondermatologists in the field of internal medicine. a study of 1290 inpatients. Dermatology. 2004;208:32-37.

- Federman DG, Concato J, Kirsner RS. Comparison of dermatologic diagnoses by primary care practitioners and dermatologists. a review of the literature. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:170-172.

- Fleischer AB Jr, Herbert CR, Feldman SR, et al. Diagnosis of skin disease by nondermatologists. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:1149-1156.

- Kirsner RS, Federman DG. Lack of correlation between internists’ ability in dermatology and their patterns of treating patients with skin disease. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1043-1046.

- McCarthy GM, Lamb GC, Russell TJ, et al. Primary care-based dermatology practice: internists need more training. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:52-56.

- Sellheyer K, Bergfeld WF. A retrospective biopsy study of the clinical diagnostic accuracy of common skin diseases by different specialties compared with dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:823-830.

- Medical specialties. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Web site. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/368ProgramandInstitutionalGuidelines/MedicalAccreditation.aspx. Accessed November 17, 2014.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.

- Thorpe KE, Florence CS, Joski P. Which medical conditions account for the rise in health care spending? Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;(suppl web exclusives):W4-437-445.

- Johnson ML. Defining the burden of skin disease in the United States—a historical perspective. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:108-110.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical expenditure panel survey. US Department of Health & Human Services Web site. http://meps.ahrq.gov. Accessed November 17, 2014.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500.

- Johnson ML. On teaching dermatology to nondermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:850-852.

- Ramsay DL, Weary PE. Primary care in dermatology: whose role should it be? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:1005-1008.

- Kimball AB, Resneck JS Jr. The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:741-745.

- Resneck JS Jr, Kimball AB. Who else is providing care in dermatology practices? trends in the use of nonphysician clinicians. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:211-216.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, McConnell RC. Most common dermatologic problems identified by internists, 1990-1994. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:726-730.

- Ahn CS, Davis SA, Debade TS, et al. Noncosmetic skin-related procedures performed in the United States: an analysis of national ambulatory medical care survey data from 1995 to 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1912-1921.

- Antic M, Conen D, Itin PH. Teaching effects of dermatological consultations on nondermatologists in the field of internal medicine. a study of 1290 inpatients. Dermatology. 2004;208:32-37.

- Federman DG, Concato J, Kirsner RS. Comparison of dermatologic diagnoses by primary care practitioners and dermatologists. a review of the literature. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:170-172.

- Fleischer AB Jr, Herbert CR, Feldman SR, et al. Diagnosis of skin disease by nondermatologists. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:1149-1156.

- Kirsner RS, Federman DG. Lack of correlation between internists’ ability in dermatology and their patterns of treating patients with skin disease. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1043-1046.

- McCarthy GM, Lamb GC, Russell TJ, et al. Primary care-based dermatology practice: internists need more training. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:52-56.

- Sellheyer K, Bergfeld WF. A retrospective biopsy study of the clinical diagnostic accuracy of common skin diseases by different specialties compared with dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:823-830.

- Medical specialties. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Web site. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/368ProgramandInstitutionalGuidelines/MedicalAccreditation.aspx. Accessed November 17, 2014.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.

Practice Points

- Approximately half of skin-related visits are to nondermatologists, such as family medicine physicians, pediatricians, and internists.

- Skin conditions that most frequently present to nondermatologists are different from those seen by dermatologists.

- Education efforts in nondermatology specialties should be targeted toward the common skin diseases that present to these specialties to maximize the yield of medical education and improve diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes.

Lower Transfusion Threshold for Sepsis Equals Fewer Transfusions, No Effect on Mortality

Clinical question

Does a lower transfusion threshold for critically ill patients with septic shock affect outcomes?

Bottom line

Using a lower threshold for transfusion for patients with septic shock in the intensive care unit (ICU) decreases the number of transfusions received without affecting mortality.

Reference

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded); (LOE: 1b)

Setting

Inpatient (ICU only)

Synopsis

Using partial blinding and concealed allocation, these investigators randomized ICU patients with septic shock and a hemoglobin level of less than 9 g/dL to receive red blood cell transfusions at either a higher threshold (< 9 g/dL) or a lower threshold (< 7 g/dL). The intervention continued for the entire ICU stay, to a maximum of 90 days. The 2 groups were similar at baseline with an average age of 67 years and a median Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 10 out of 24. Analysis was by intention to treat. Not suprisingly, patients in the higher threshold group received twice as many transfusions as those in the lower threshold group (3088 transfusions vs 1545; P < .001). Notably, one third of the patients in the lower-threshold group required no transfusions at all compared with only 1% in the higher-threshold group (P < .001). For the primary outcome of death at 90 days, there was no significant difference detected between the 2 groups. The per-protocol analysis, which excluded patients with major protocol violations, also showed the same result. Secondary outcomes, including the use of life support and the number of ischemic events in the ICU (eg, acute myocardial or cerebral ischemia), were also similar in the 2 groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Does a lower transfusion threshold for critically ill patients with septic shock affect outcomes?

Bottom line

Using a lower threshold for transfusion for patients with septic shock in the intensive care unit (ICU) decreases the number of transfusions received without affecting mortality.

Reference

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded); (LOE: 1b)

Setting

Inpatient (ICU only)

Synopsis

Using partial blinding and concealed allocation, these investigators randomized ICU patients with septic shock and a hemoglobin level of less than 9 g/dL to receive red blood cell transfusions at either a higher threshold (< 9 g/dL) or a lower threshold (< 7 g/dL). The intervention continued for the entire ICU stay, to a maximum of 90 days. The 2 groups were similar at baseline with an average age of 67 years and a median Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 10 out of 24. Analysis was by intention to treat. Not suprisingly, patients in the higher threshold group received twice as many transfusions as those in the lower threshold group (3088 transfusions vs 1545; P < .001). Notably, one third of the patients in the lower-threshold group required no transfusions at all compared with only 1% in the higher-threshold group (P < .001). For the primary outcome of death at 90 days, there was no significant difference detected between the 2 groups. The per-protocol analysis, which excluded patients with major protocol violations, also showed the same result. Secondary outcomes, including the use of life support and the number of ischemic events in the ICU (eg, acute myocardial or cerebral ischemia), were also similar in the 2 groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Does a lower transfusion threshold for critically ill patients with septic shock affect outcomes?

Bottom line

Using a lower threshold for transfusion for patients with septic shock in the intensive care unit (ICU) decreases the number of transfusions received without affecting mortality.

Reference

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded); (LOE: 1b)

Setting

Inpatient (ICU only)

Synopsis

Using partial blinding and concealed allocation, these investigators randomized ICU patients with septic shock and a hemoglobin level of less than 9 g/dL to receive red blood cell transfusions at either a higher threshold (< 9 g/dL) or a lower threshold (< 7 g/dL). The intervention continued for the entire ICU stay, to a maximum of 90 days. The 2 groups were similar at baseline with an average age of 67 years and a median Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 10 out of 24. Analysis was by intention to treat. Not suprisingly, patients in the higher threshold group received twice as many transfusions as those in the lower threshold group (3088 transfusions vs 1545; P < .001). Notably, one third of the patients in the lower-threshold group required no transfusions at all compared with only 1% in the higher-threshold group (P < .001). For the primary outcome of death at 90 days, there was no significant difference detected between the 2 groups. The per-protocol analysis, which excluded patients with major protocol violations, also showed the same result. Secondary outcomes, including the use of life support and the number of ischemic events in the ICU (eg, acute myocardial or cerebral ischemia), were also similar in the 2 groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Targeted Therapy for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

This presentation by Adrian Wiestner, MD, PhD, from the 2014 AVAHO Meeting in Portland, Oregon, provides an overview of new insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of CLL, how to interpret molecular targets during treatment, and the advantages and disadvantages of these treatment options for patients.

"The standard of care today is really chemo-immunotherapy," Wiestner said. "Ideally, we would like to have a more disease-directed therapy that is tolerable and active."

This presentation by Adrian Wiestner, MD, PhD, from the 2014 AVAHO Meeting in Portland, Oregon, provides an overview of new insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of CLL, how to interpret molecular targets during treatment, and the advantages and disadvantages of these treatment options for patients.

"The standard of care today is really chemo-immunotherapy," Wiestner said. "Ideally, we would like to have a more disease-directed therapy that is tolerable and active."

This presentation by Adrian Wiestner, MD, PhD, from the 2014 AVAHO Meeting in Portland, Oregon, provides an overview of new insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of CLL, how to interpret molecular targets during treatment, and the advantages and disadvantages of these treatment options for patients.

"The standard of care today is really chemo-immunotherapy," Wiestner said. "Ideally, we would like to have a more disease-directed therapy that is tolerable and active."

The Rural Surgeon: A new column

Surgeons who treat patients in rural areas are a unique group, distinct from other surgeons because of scope of practice, environment, and resources. These surgeons address a vast range of surgical problems, work in relative professional isolation, and have fewer resources available to get the job done. Nevertheless, these physicians play critical roles in their profession and are irreplaceable assets in their communities.

Although poorly defined, often misunderstood, arguably unfairly characterized, and inadequately documented, surgery has a long distinguished history and tradition in rural communities.

What are the main challenges faced by rural surgeons and what can be done to strengthen their practices, professional lives, and longevity in the field? Rural patients are more likely than urban patients to be elderly and poor and have chronic illnesses (J. Am Coll. Surg. 2014;219:814-8). The average age of rural surgeons suggests that many will retire in the coming decade. Who will replace them and care for 60 million citizens who reside in rural America? How will the gradual decline of residents choosing general surgery and rural practice affect patient care?

This new monthly column, Rural Surgeons Speak, focuses on these questions and searches for answers. Rural Surgeons Speak will introduce to all readers the voices, concerns, questions, and opinions of surgeons practicing in the small towns and rural regions of the United States. Although many of the challenges faced by rural surgeons are unique to this group, there is overlap with issues encountered by urban surgeons and those in academic settings. In spite of problems ranging from a shift from independent practice to hospital employment and to treating the poor with pronounced chronic illnesses, rural surgeons are dedicated and committed. Although these matters are common to all surgeons, rural surgeons’ experiences tend to be singular because of the high percentages of such patients and fewer institutional resources.

I have practiced surgery in small and large rural locations for 37 years. Rural surgery is not a specialty. My case log, filled with endoscopies, laparoscopies, laparotomies, and breast operations, may be even more varied than the logs of urban colleagues. In my early years of practice, I did orthopaedic surgery and gynecology. As a conscious choice, I practiced surgery where I wanted, and how I wanted. My choice was not by default. When I started, I sought a location that would allow me to “have a more complete life with less tension, excellent schools, opportunity for economical living,” and a fulfilling surgery practice. Unknown to me, Dr. Edwin F. Cave, ACS president, made those statements about rural surgery in the Daily Clinical Bulletin for the 37th Annual Clinical Congress decades before I started.

Like other rural surgeons, I wanted to embrace and be embraced by my community. I also saw opportunities for personal advancement (involvement with ACS), and for the development of my surgical talents (lasers, laparoscopies, endoscopies). I live just a mile from the hospital. I know my patients by their first names. They speak to me on the telephone. My number is in the book. When they meet me in church or at the grocery store, I am “Doc.” Occasionally a PEx is performed in such locations. It is personal. It is comfortable. There is a real sense of community and of belonging. I am involved. I provide an invaluable service “right at home,” where my patients want to be treated. In return, I am valued and supported.

After becoming a FACS in 1979, I involved myself in many activities of the ACS. Most recently, I participated in the rural surgery renaissance from its beginning. As part of my participation, I routinely contacted rural surgeons around the United States and gained intimate and detailed knowledge about their practices, successes, and concerns. I bring insights from my background to the writing of this column.

While glamour is at a minimum in rural America, personal satisfaction for many of these surgeons is at a maximum. Unfortunately, isolation is a given in most rural practices, and therein lies the problem. In spite of offering much to their patients and, in turn, to the profession, rural surgeons are easy targets of negative assessments, ill-conceived policy changes, and misunderstandings.

Despite their vital role in treating patients, rural surgeons often regard themselves as unrecognized and unappreciated by their peers. There is a subtle bias in the profession against a surgeon who would choose this life of relative isolation, alleged nonspecialized surgery, and overwork in communities with fewer cultural resources and fewer employment options for spouses. Yet their work is essential to the health of millions of people who live in rural areas. Thankfully, the profession as a whole has stopped ignoring rural surgery in recent years as the ACS leadership has stepped in and begun to increase support for rural surgeons.

In May 2011, during the 5th Annual Rural Surgery Symposium and Workshop, I presented a talk, “The ACS and the Rural Surgeon.” Past President Dr. LaMar McGinnis acknowledged the educational value of the presentation, which then went on to wider distribution. The Board of Regents received another talk about rural surgery in February 2012: “Us vs. Them.” Based on the talk and because of their keen insights, the Regents formed the Advisory Council on Rural Surgery – the first new advisory council in 50 years. Subsequently, a College-developed rural listserv became the most highly successful communications program in ACS history and led to the creation of the rural surgery community. In the following 2 years, rural surgeons exchanged 9 million emails on numerous, varied topics. An article in the July 2014 ACS Bulletin describes the program (http://bulletin.facs.org/2014/07/acs-rural-listserv-an-underdog-success-story/). Finally, in his inaugural address at the 2012 Clinical Congress, Dr. Brent Eastman identified rural surgery as one of the four fundamental components of surgery for the next 100 years (http://bulletin.facs.org/2012/12/presidential-address/). Recognition of rural surgery obviously has increased.

My experience of moderating the rural listserv with nearly 1,000 subscribers has revealed the amazing diversity, passion, commitment, and perseverance of rural surgeons who have united in a true community. Their perspectives on their professional lives and the lives of their patients are well worth closer acquaintance by surgeons from all sectors. They have a lot to teach us all. To learn about rural surgery will be to learn about all surgery. Understand rural surgery in 2014 and, consequently, understand all surgery. Recognize the benefits of rural surgery and then instill them in all practices. Supporting rural surgery today supports all surgery.

The column aims to offer commentary on diverse topics confronting rural surgeons today. Opinions, editorials, letters, economics, and clinical matters, all from the rural perspective, will be included. Over 60 individual “threads” appeared on the listserv this year and the subjects of many of these threads could be covered in future columns. Uncommon subjects such as YKYAARSI (“You know you are a rural surgeon if…”) should be entertaining and informative. Guest authors who are experts on varying subjects will contribute articles.

While its roots are in the rural surgery community, the column’s scope will touch all surgical practices. Rural surgery will be better defined, positively characterized, and documented. In partnership with the ACS to achieve the general goal of supporting rural surgery, Rural Surgeons Speak aims to enable all ACS Fellows to realize that they belong to a community of all surgeons, regardless of location or practice type.

Dr. Caropreso is a general surgeon at Keokuk (Iowa) Area Hospital and Clinical Professor of Surgery at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine. He has practiced surgery in the rural communities of Mason City, Iowa; Keokuk, Iowa; and Carthage, Ill., for 37 years.

Surgeons who treat patients in rural areas are a unique group, distinct from other surgeons because of scope of practice, environment, and resources. These surgeons address a vast range of surgical problems, work in relative professional isolation, and have fewer resources available to get the job done. Nevertheless, these physicians play critical roles in their profession and are irreplaceable assets in their communities.

Although poorly defined, often misunderstood, arguably unfairly characterized, and inadequately documented, surgery has a long distinguished history and tradition in rural communities.

What are the main challenges faced by rural surgeons and what can be done to strengthen their practices, professional lives, and longevity in the field? Rural patients are more likely than urban patients to be elderly and poor and have chronic illnesses (J. Am Coll. Surg. 2014;219:814-8). The average age of rural surgeons suggests that many will retire in the coming decade. Who will replace them and care for 60 million citizens who reside in rural America? How will the gradual decline of residents choosing general surgery and rural practice affect patient care?

This new monthly column, Rural Surgeons Speak, focuses on these questions and searches for answers. Rural Surgeons Speak will introduce to all readers the voices, concerns, questions, and opinions of surgeons practicing in the small towns and rural regions of the United States. Although many of the challenges faced by rural surgeons are unique to this group, there is overlap with issues encountered by urban surgeons and those in academic settings. In spite of problems ranging from a shift from independent practice to hospital employment and to treating the poor with pronounced chronic illnesses, rural surgeons are dedicated and committed. Although these matters are common to all surgeons, rural surgeons’ experiences tend to be singular because of the high percentages of such patients and fewer institutional resources.

I have practiced surgery in small and large rural locations for 37 years. Rural surgery is not a specialty. My case log, filled with endoscopies, laparoscopies, laparotomies, and breast operations, may be even more varied than the logs of urban colleagues. In my early years of practice, I did orthopaedic surgery and gynecology. As a conscious choice, I practiced surgery where I wanted, and how I wanted. My choice was not by default. When I started, I sought a location that would allow me to “have a more complete life with less tension, excellent schools, opportunity for economical living,” and a fulfilling surgery practice. Unknown to me, Dr. Edwin F. Cave, ACS president, made those statements about rural surgery in the Daily Clinical Bulletin for the 37th Annual Clinical Congress decades before I started.

Like other rural surgeons, I wanted to embrace and be embraced by my community. I also saw opportunities for personal advancement (involvement with ACS), and for the development of my surgical talents (lasers, laparoscopies, endoscopies). I live just a mile from the hospital. I know my patients by their first names. They speak to me on the telephone. My number is in the book. When they meet me in church or at the grocery store, I am “Doc.” Occasionally a PEx is performed in such locations. It is personal. It is comfortable. There is a real sense of community and of belonging. I am involved. I provide an invaluable service “right at home,” where my patients want to be treated. In return, I am valued and supported.

After becoming a FACS in 1979, I involved myself in many activities of the ACS. Most recently, I participated in the rural surgery renaissance from its beginning. As part of my participation, I routinely contacted rural surgeons around the United States and gained intimate and detailed knowledge about their practices, successes, and concerns. I bring insights from my background to the writing of this column.

While glamour is at a minimum in rural America, personal satisfaction for many of these surgeons is at a maximum. Unfortunately, isolation is a given in most rural practices, and therein lies the problem. In spite of offering much to their patients and, in turn, to the profession, rural surgeons are easy targets of negative assessments, ill-conceived policy changes, and misunderstandings.

Despite their vital role in treating patients, rural surgeons often regard themselves as unrecognized and unappreciated by their peers. There is a subtle bias in the profession against a surgeon who would choose this life of relative isolation, alleged nonspecialized surgery, and overwork in communities with fewer cultural resources and fewer employment options for spouses. Yet their work is essential to the health of millions of people who live in rural areas. Thankfully, the profession as a whole has stopped ignoring rural surgery in recent years as the ACS leadership has stepped in and begun to increase support for rural surgeons.

In May 2011, during the 5th Annual Rural Surgery Symposium and Workshop, I presented a talk, “The ACS and the Rural Surgeon.” Past President Dr. LaMar McGinnis acknowledged the educational value of the presentation, which then went on to wider distribution. The Board of Regents received another talk about rural surgery in February 2012: “Us vs. Them.” Based on the talk and because of their keen insights, the Regents formed the Advisory Council on Rural Surgery – the first new advisory council in 50 years. Subsequently, a College-developed rural listserv became the most highly successful communications program in ACS history and led to the creation of the rural surgery community. In the following 2 years, rural surgeons exchanged 9 million emails on numerous, varied topics. An article in the July 2014 ACS Bulletin describes the program (http://bulletin.facs.org/2014/07/acs-rural-listserv-an-underdog-success-story/). Finally, in his inaugural address at the 2012 Clinical Congress, Dr. Brent Eastman identified rural surgery as one of the four fundamental components of surgery for the next 100 years (http://bulletin.facs.org/2012/12/presidential-address/). Recognition of rural surgery obviously has increased.

My experience of moderating the rural listserv with nearly 1,000 subscribers has revealed the amazing diversity, passion, commitment, and perseverance of rural surgeons who have united in a true community. Their perspectives on their professional lives and the lives of their patients are well worth closer acquaintance by surgeons from all sectors. They have a lot to teach us all. To learn about rural surgery will be to learn about all surgery. Understand rural surgery in 2014 and, consequently, understand all surgery. Recognize the benefits of rural surgery and then instill them in all practices. Supporting rural surgery today supports all surgery.

The column aims to offer commentary on diverse topics confronting rural surgeons today. Opinions, editorials, letters, economics, and clinical matters, all from the rural perspective, will be included. Over 60 individual “threads” appeared on the listserv this year and the subjects of many of these threads could be covered in future columns. Uncommon subjects such as YKYAARSI (“You know you are a rural surgeon if…”) should be entertaining and informative. Guest authors who are experts on varying subjects will contribute articles.

While its roots are in the rural surgery community, the column’s scope will touch all surgical practices. Rural surgery will be better defined, positively characterized, and documented. In partnership with the ACS to achieve the general goal of supporting rural surgery, Rural Surgeons Speak aims to enable all ACS Fellows to realize that they belong to a community of all surgeons, regardless of location or practice type.

Dr. Caropreso is a general surgeon at Keokuk (Iowa) Area Hospital and Clinical Professor of Surgery at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine. He has practiced surgery in the rural communities of Mason City, Iowa; Keokuk, Iowa; and Carthage, Ill., for 37 years.

Surgeons who treat patients in rural areas are a unique group, distinct from other surgeons because of scope of practice, environment, and resources. These surgeons address a vast range of surgical problems, work in relative professional isolation, and have fewer resources available to get the job done. Nevertheless, these physicians play critical roles in their profession and are irreplaceable assets in their communities.

Although poorly defined, often misunderstood, arguably unfairly characterized, and inadequately documented, surgery has a long distinguished history and tradition in rural communities.