User login

Home-Based Video Telehealth for Veterans With Dementia

For nearly 4 decades, the unifying focus of the 2-site New England Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) has been on dementia and related disorders. Veterans with dementia are an extremely vulnerable population with high rates of health care use that is projected to total > $203 billion in the U.S. in 2013.1 Their caregivers are also among the most burdened, having provided about 17.5 billion hours of unpaid care in 2012, which is valued at more than $216 billion.1 Additionally, spouses, who are the most common caregivers of persons with dementia, often experience poor health outcomes related to the experience of living with the afflicted spouse.2

Currently > 200,000 VA patients have dementia, and that number is expected to increase.3 Dementia is largely a disease of the elderly; thus, many veterans with dementia also have other medical and orthopedic conditions that increase their frailty and decrease their mobility. Behavioral and psychological symptoms are present in > 75% of people with dementia, contributing to the relative isolation of both those with dementia and their families.4

Disruption in routine and removal from familiar surroundings can cause many patients, particularly in the moderate stages of dementia, to become disoriented and agitated. For these patients, VA clinics can be unsettling and may reveal behavior that is not the same as the veterans’ behavior at home. For these reasons, veterans with dementia likely may benefit from remote access to health care via telehealth. However, current telehealth applications for this population are vastly underdeveloped.

Video Dementia Management

Many GRECCs and other VA geriatric programs provide video-based dementia evaluations and management at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) affiliated with their medical centers. At this point, close to a dozen GRECC and geriatric programs nationally have geriatric psychiatrists, geriatricians, or neurologists conducting such visits from their office or clinic space with video links to a telehealth-enabled room in the corresponding CBOC.

The visits usually entail having the veteran and, when appropriate, a family member check in at the local CBOC for the appointment and receiving assistance throughout the video visit from the telehealth technician at the CBOC.

The technician assists with the technical aspects of the encounter, including establishing and maintaining the video link to the VA medical center (VAMC), and often is trained to administer a brief standardized mental status assessment. The telehealth technician also helps pass along the physician’s written recommendations to the veteran and family once the recommendation summary has been sent by e-mail or printed on the CBOC printer. These VAMC-CBOC video telehealth programs have been very popular with veterans, particularly those in rural settings, since traveling to the CBOC is usually more convenient.

Home-based Video Program

While CBOC-based video telehealth programs expand the population of veterans able to benefit from specialty dementia care, any travel out of the home can be challenging or disruptive for many veterans and their families. In addition, the performance and demeanor of a veteran with dementia in a clinic setting is sometimes different from that which the family describes as their more typical behavior at home.

A new in-home video telehealth program developed by the GRECC at the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital in Bedford is addressing these issues. The Bedford site of the New England GRECC offers in-home clinical video telehealth services to community-dwelling veterans and caregivers as an extension of their Interdisciplinary Memory Assessment Continuity Clinic (IMACC). Currently, the percentage of IMACC veterans/caregivers who have voluntarily signed up for the program is nearly 30%. About 70% of the families that have enrolled to date have their video visits with their spouse caregivers.

Veterans participating in the home video telehealth program have had at least 1 in-person visit at the Bedford IMACC before being invited to join. Veterans and their caregivers are invited to participate in the GRECC home telehealth program either at the time of an in-person IMACC visit or afterward via a telephone call from either a provider or a member of the telehealth staff.

Telehealth visits are offered as a supplement to regularly scheduled in-person visits, not as a substitute. The frequency of telehealth visits is individualized, depending on the medical status of the veteran and preferences of the caregiver. Some participating families, finding the telehealth format much more convenient, have asked whether they could postpone upcoming in-person visits at the VAMC. Many patients are particularly interested in minimizing medical visits in the winter months in New England.

Case Example

A male World War II veteran with moderate stage dementia lived with his wife in an apartment down the street from his adult son and daughter-in-law. His son and daughter-in-law visited and helped with the veteran’s care most days, but his wife was his primary caregiver. However, due to her own mobility issues, she was unable to attend the veteran’s in-person IMACC initial evaluation or subsequent follow-up visit.

This family enthusiastically embraced the opportunity to participate in the home video telehealth program and had multiple telehealth visits. During these video encounters, the veteran, his wife, and his son and daughter-in-law were present. The clinician, communicating via computer from the Bedford VAMC, was able to hear from all the caregivers, observe the veteran as he interacted with each person, and watch as he walked within the comfort and familiarity of his home.

Based on these observations, the veteran was clearly at risk for falls. The clinician ordered a home safety consultation as a result. Thus the home video telehealth program allowed this veteran’s mobility-impaired wife to participate directly in his dementia care. It gave the clinician an opportunity to spot potential fall risks within the veteran’s home before a disabling fall and provided the entire family with additional, convenient dementia-related care beyond the standard in-person VAMC visits.

Establishing Home Video Links

Veterans must already have broadband Internet access and a home computer or laptop to participate in the program. To assess the connectivity status and computer comfort level of the family, a Bedford VAMC telehealth technician calls the caregiver to assess their computer, operating system, presence of a webcam, and Internet service provider.

In addition to assessing the equipment necessary for the telehealth visit, the Bedford VAMC telehealth team also determines whether or not the caregiver has had experience with videoconferencing. Based on this information, the proper level of support is given to the family for both the initial software and, when necessary, VA-provided webcam installation.

On a few occasions, program staff have visited the veteran’s home to install the software and camera. Thus the telehealth program is fit to the family needs and resources to ensure a successful visit. The Bedford VAMC telehealth team provides enrolled families with live phone-based support for download and installation of the VA-approved videoconferencing software and webcam. For each scheduled video telehealth visit, a telehealth technician is available via phone to assist the caregiver with initiating the video call to the clinician.

Next Steps

GRECC neurologist Lauren Moo, MD, is leading this telehealth initiative as a clinical demonstration project and is studying implementation of the service. Dr. Moo is collecting data on whether IMACC veterans/caregivers accept or decline enrollment and their reasons for declining. The goal is to empirically determine the degree to which age, Internet access, and other variables are barriers to wider adoption.

Dr. Moo predicts that the improved access to clinical care offered by home video telehealth will translate into reduced hotline calls, emergency department visits, and delay in community living center placement. Easier access should facilitate earlier intervention for common dementia-related issues, such as fall risk, behavioral symptoms, and disruption of circadian rhythm, thereby improving quality of life and reducing overall health care utilization for this growing population of veterans.

There is the perception that geriatric veterans are not “wired” for Internet-based communications or lack the technical proficiency to use current and evolving technologies. However, a recent national survey suggests that while only 34% of those aged > 75 years use the Internet, there has been a significant jump in the percentage of Americans aged ≥ 65 years that use the Internet or e-mail: from 40% in 2010 to 53% in 2012.5

Once online, 70% of adults aged ≥ 65 years use the Internet on a typical day, suggesting that when given the necessary tools and training, seniors are enthusiastic technology adopters.5 Thus, it is anticipated that the number of geriatric veterans interested in and able to take advantage of the in-home video visit format will grow rapidly in the near future. The initial enrollment rate at Bedford of 30% is expected to grow as families and providers become more familiar with this modality.

The Bedford VAMC is in an urban/suburban region with multiple Internet service providers, a relatively educated population, and comparatively low levels of poverty. As such, the Bedford VAMC veterans with dementia and their caregivers are likely a best-case scenario population in which to pilot this dementia home telehealth program. If the preliminary success of this pilot program is sustained, expansion to a broader range of home telehealth services, such as social work and home safety assessments, to more rural settings would be the logical next steps.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Thies W, Bleiler L; Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):208-245.

2. Kolanowski AM, Fick D, Waller JL, Shea D. Spouses of persons with dementia: Their healthcare problems, utilization, and costs. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27(5):296-306.

3. Veterans Health Administration Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. Projections of the prevalence and incidence of dementias including Alzheimer’s Disease for the total, enrolled, and patient veteran populations age 65 or over. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www4.va.gov/healthpolicyplanning/dementia/Dem022004.pdf. Published February 20, 2004. Accessed October 10, 2014.

4. Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: Results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475-1483.

5. Zickuhr K, Madden M. Older adults and Internet use. Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project Website. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Older-adults-and-internet-use.aspx. Updated June 6, 2012. Accessed October 17, 2014.

For nearly 4 decades, the unifying focus of the 2-site New England Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) has been on dementia and related disorders. Veterans with dementia are an extremely vulnerable population with high rates of health care use that is projected to total > $203 billion in the U.S. in 2013.1 Their caregivers are also among the most burdened, having provided about 17.5 billion hours of unpaid care in 2012, which is valued at more than $216 billion.1 Additionally, spouses, who are the most common caregivers of persons with dementia, often experience poor health outcomes related to the experience of living with the afflicted spouse.2

Currently > 200,000 VA patients have dementia, and that number is expected to increase.3 Dementia is largely a disease of the elderly; thus, many veterans with dementia also have other medical and orthopedic conditions that increase their frailty and decrease their mobility. Behavioral and psychological symptoms are present in > 75% of people with dementia, contributing to the relative isolation of both those with dementia and their families.4

Disruption in routine and removal from familiar surroundings can cause many patients, particularly in the moderate stages of dementia, to become disoriented and agitated. For these patients, VA clinics can be unsettling and may reveal behavior that is not the same as the veterans’ behavior at home. For these reasons, veterans with dementia likely may benefit from remote access to health care via telehealth. However, current telehealth applications for this population are vastly underdeveloped.

Video Dementia Management

Many GRECCs and other VA geriatric programs provide video-based dementia evaluations and management at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) affiliated with their medical centers. At this point, close to a dozen GRECC and geriatric programs nationally have geriatric psychiatrists, geriatricians, or neurologists conducting such visits from their office or clinic space with video links to a telehealth-enabled room in the corresponding CBOC.

The visits usually entail having the veteran and, when appropriate, a family member check in at the local CBOC for the appointment and receiving assistance throughout the video visit from the telehealth technician at the CBOC.

The technician assists with the technical aspects of the encounter, including establishing and maintaining the video link to the VA medical center (VAMC), and often is trained to administer a brief standardized mental status assessment. The telehealth technician also helps pass along the physician’s written recommendations to the veteran and family once the recommendation summary has been sent by e-mail or printed on the CBOC printer. These VAMC-CBOC video telehealth programs have been very popular with veterans, particularly those in rural settings, since traveling to the CBOC is usually more convenient.

Home-based Video Program

While CBOC-based video telehealth programs expand the population of veterans able to benefit from specialty dementia care, any travel out of the home can be challenging or disruptive for many veterans and their families. In addition, the performance and demeanor of a veteran with dementia in a clinic setting is sometimes different from that which the family describes as their more typical behavior at home.

A new in-home video telehealth program developed by the GRECC at the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital in Bedford is addressing these issues. The Bedford site of the New England GRECC offers in-home clinical video telehealth services to community-dwelling veterans and caregivers as an extension of their Interdisciplinary Memory Assessment Continuity Clinic (IMACC). Currently, the percentage of IMACC veterans/caregivers who have voluntarily signed up for the program is nearly 30%. About 70% of the families that have enrolled to date have their video visits with their spouse caregivers.

Veterans participating in the home video telehealth program have had at least 1 in-person visit at the Bedford IMACC before being invited to join. Veterans and their caregivers are invited to participate in the GRECC home telehealth program either at the time of an in-person IMACC visit or afterward via a telephone call from either a provider or a member of the telehealth staff.

Telehealth visits are offered as a supplement to regularly scheduled in-person visits, not as a substitute. The frequency of telehealth visits is individualized, depending on the medical status of the veteran and preferences of the caregiver. Some participating families, finding the telehealth format much more convenient, have asked whether they could postpone upcoming in-person visits at the VAMC. Many patients are particularly interested in minimizing medical visits in the winter months in New England.

Case Example

A male World War II veteran with moderate stage dementia lived with his wife in an apartment down the street from his adult son and daughter-in-law. His son and daughter-in-law visited and helped with the veteran’s care most days, but his wife was his primary caregiver. However, due to her own mobility issues, she was unable to attend the veteran’s in-person IMACC initial evaluation or subsequent follow-up visit.

This family enthusiastically embraced the opportunity to participate in the home video telehealth program and had multiple telehealth visits. During these video encounters, the veteran, his wife, and his son and daughter-in-law were present. The clinician, communicating via computer from the Bedford VAMC, was able to hear from all the caregivers, observe the veteran as he interacted with each person, and watch as he walked within the comfort and familiarity of his home.

Based on these observations, the veteran was clearly at risk for falls. The clinician ordered a home safety consultation as a result. Thus the home video telehealth program allowed this veteran’s mobility-impaired wife to participate directly in his dementia care. It gave the clinician an opportunity to spot potential fall risks within the veteran’s home before a disabling fall and provided the entire family with additional, convenient dementia-related care beyond the standard in-person VAMC visits.

Establishing Home Video Links

Veterans must already have broadband Internet access and a home computer or laptop to participate in the program. To assess the connectivity status and computer comfort level of the family, a Bedford VAMC telehealth technician calls the caregiver to assess their computer, operating system, presence of a webcam, and Internet service provider.

In addition to assessing the equipment necessary for the telehealth visit, the Bedford VAMC telehealth team also determines whether or not the caregiver has had experience with videoconferencing. Based on this information, the proper level of support is given to the family for both the initial software and, when necessary, VA-provided webcam installation.

On a few occasions, program staff have visited the veteran’s home to install the software and camera. Thus the telehealth program is fit to the family needs and resources to ensure a successful visit. The Bedford VAMC telehealth team provides enrolled families with live phone-based support for download and installation of the VA-approved videoconferencing software and webcam. For each scheduled video telehealth visit, a telehealth technician is available via phone to assist the caregiver with initiating the video call to the clinician.

Next Steps

GRECC neurologist Lauren Moo, MD, is leading this telehealth initiative as a clinical demonstration project and is studying implementation of the service. Dr. Moo is collecting data on whether IMACC veterans/caregivers accept or decline enrollment and their reasons for declining. The goal is to empirically determine the degree to which age, Internet access, and other variables are barriers to wider adoption.

Dr. Moo predicts that the improved access to clinical care offered by home video telehealth will translate into reduced hotline calls, emergency department visits, and delay in community living center placement. Easier access should facilitate earlier intervention for common dementia-related issues, such as fall risk, behavioral symptoms, and disruption of circadian rhythm, thereby improving quality of life and reducing overall health care utilization for this growing population of veterans.

There is the perception that geriatric veterans are not “wired” for Internet-based communications or lack the technical proficiency to use current and evolving technologies. However, a recent national survey suggests that while only 34% of those aged > 75 years use the Internet, there has been a significant jump in the percentage of Americans aged ≥ 65 years that use the Internet or e-mail: from 40% in 2010 to 53% in 2012.5

Once online, 70% of adults aged ≥ 65 years use the Internet on a typical day, suggesting that when given the necessary tools and training, seniors are enthusiastic technology adopters.5 Thus, it is anticipated that the number of geriatric veterans interested in and able to take advantage of the in-home video visit format will grow rapidly in the near future. The initial enrollment rate at Bedford of 30% is expected to grow as families and providers become more familiar with this modality.

The Bedford VAMC is in an urban/suburban region with multiple Internet service providers, a relatively educated population, and comparatively low levels of poverty. As such, the Bedford VAMC veterans with dementia and their caregivers are likely a best-case scenario population in which to pilot this dementia home telehealth program. If the preliminary success of this pilot program is sustained, expansion to a broader range of home telehealth services, such as social work and home safety assessments, to more rural settings would be the logical next steps.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

For nearly 4 decades, the unifying focus of the 2-site New England Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) has been on dementia and related disorders. Veterans with dementia are an extremely vulnerable population with high rates of health care use that is projected to total > $203 billion in the U.S. in 2013.1 Their caregivers are also among the most burdened, having provided about 17.5 billion hours of unpaid care in 2012, which is valued at more than $216 billion.1 Additionally, spouses, who are the most common caregivers of persons with dementia, often experience poor health outcomes related to the experience of living with the afflicted spouse.2

Currently > 200,000 VA patients have dementia, and that number is expected to increase.3 Dementia is largely a disease of the elderly; thus, many veterans with dementia also have other medical and orthopedic conditions that increase their frailty and decrease their mobility. Behavioral and psychological symptoms are present in > 75% of people with dementia, contributing to the relative isolation of both those with dementia and their families.4

Disruption in routine and removal from familiar surroundings can cause many patients, particularly in the moderate stages of dementia, to become disoriented and agitated. For these patients, VA clinics can be unsettling and may reveal behavior that is not the same as the veterans’ behavior at home. For these reasons, veterans with dementia likely may benefit from remote access to health care via telehealth. However, current telehealth applications for this population are vastly underdeveloped.

Video Dementia Management

Many GRECCs and other VA geriatric programs provide video-based dementia evaluations and management at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) affiliated with their medical centers. At this point, close to a dozen GRECC and geriatric programs nationally have geriatric psychiatrists, geriatricians, or neurologists conducting such visits from their office or clinic space with video links to a telehealth-enabled room in the corresponding CBOC.

The visits usually entail having the veteran and, when appropriate, a family member check in at the local CBOC for the appointment and receiving assistance throughout the video visit from the telehealth technician at the CBOC.

The technician assists with the technical aspects of the encounter, including establishing and maintaining the video link to the VA medical center (VAMC), and often is trained to administer a brief standardized mental status assessment. The telehealth technician also helps pass along the physician’s written recommendations to the veteran and family once the recommendation summary has been sent by e-mail or printed on the CBOC printer. These VAMC-CBOC video telehealth programs have been very popular with veterans, particularly those in rural settings, since traveling to the CBOC is usually more convenient.

Home-based Video Program

While CBOC-based video telehealth programs expand the population of veterans able to benefit from specialty dementia care, any travel out of the home can be challenging or disruptive for many veterans and their families. In addition, the performance and demeanor of a veteran with dementia in a clinic setting is sometimes different from that which the family describes as their more typical behavior at home.

A new in-home video telehealth program developed by the GRECC at the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital in Bedford is addressing these issues. The Bedford site of the New England GRECC offers in-home clinical video telehealth services to community-dwelling veterans and caregivers as an extension of their Interdisciplinary Memory Assessment Continuity Clinic (IMACC). Currently, the percentage of IMACC veterans/caregivers who have voluntarily signed up for the program is nearly 30%. About 70% of the families that have enrolled to date have their video visits with their spouse caregivers.

Veterans participating in the home video telehealth program have had at least 1 in-person visit at the Bedford IMACC before being invited to join. Veterans and their caregivers are invited to participate in the GRECC home telehealth program either at the time of an in-person IMACC visit or afterward via a telephone call from either a provider or a member of the telehealth staff.

Telehealth visits are offered as a supplement to regularly scheduled in-person visits, not as a substitute. The frequency of telehealth visits is individualized, depending on the medical status of the veteran and preferences of the caregiver. Some participating families, finding the telehealth format much more convenient, have asked whether they could postpone upcoming in-person visits at the VAMC. Many patients are particularly interested in minimizing medical visits in the winter months in New England.

Case Example

A male World War II veteran with moderate stage dementia lived with his wife in an apartment down the street from his adult son and daughter-in-law. His son and daughter-in-law visited and helped with the veteran’s care most days, but his wife was his primary caregiver. However, due to her own mobility issues, she was unable to attend the veteran’s in-person IMACC initial evaluation or subsequent follow-up visit.

This family enthusiastically embraced the opportunity to participate in the home video telehealth program and had multiple telehealth visits. During these video encounters, the veteran, his wife, and his son and daughter-in-law were present. The clinician, communicating via computer from the Bedford VAMC, was able to hear from all the caregivers, observe the veteran as he interacted with each person, and watch as he walked within the comfort and familiarity of his home.

Based on these observations, the veteran was clearly at risk for falls. The clinician ordered a home safety consultation as a result. Thus the home video telehealth program allowed this veteran’s mobility-impaired wife to participate directly in his dementia care. It gave the clinician an opportunity to spot potential fall risks within the veteran’s home before a disabling fall and provided the entire family with additional, convenient dementia-related care beyond the standard in-person VAMC visits.

Establishing Home Video Links

Veterans must already have broadband Internet access and a home computer or laptop to participate in the program. To assess the connectivity status and computer comfort level of the family, a Bedford VAMC telehealth technician calls the caregiver to assess their computer, operating system, presence of a webcam, and Internet service provider.

In addition to assessing the equipment necessary for the telehealth visit, the Bedford VAMC telehealth team also determines whether or not the caregiver has had experience with videoconferencing. Based on this information, the proper level of support is given to the family for both the initial software and, when necessary, VA-provided webcam installation.

On a few occasions, program staff have visited the veteran’s home to install the software and camera. Thus the telehealth program is fit to the family needs and resources to ensure a successful visit. The Bedford VAMC telehealth team provides enrolled families with live phone-based support for download and installation of the VA-approved videoconferencing software and webcam. For each scheduled video telehealth visit, a telehealth technician is available via phone to assist the caregiver with initiating the video call to the clinician.

Next Steps

GRECC neurologist Lauren Moo, MD, is leading this telehealth initiative as a clinical demonstration project and is studying implementation of the service. Dr. Moo is collecting data on whether IMACC veterans/caregivers accept or decline enrollment and their reasons for declining. The goal is to empirically determine the degree to which age, Internet access, and other variables are barriers to wider adoption.

Dr. Moo predicts that the improved access to clinical care offered by home video telehealth will translate into reduced hotline calls, emergency department visits, and delay in community living center placement. Easier access should facilitate earlier intervention for common dementia-related issues, such as fall risk, behavioral symptoms, and disruption of circadian rhythm, thereby improving quality of life and reducing overall health care utilization for this growing population of veterans.

There is the perception that geriatric veterans are not “wired” for Internet-based communications or lack the technical proficiency to use current and evolving technologies. However, a recent national survey suggests that while only 34% of those aged > 75 years use the Internet, there has been a significant jump in the percentage of Americans aged ≥ 65 years that use the Internet or e-mail: from 40% in 2010 to 53% in 2012.5

Once online, 70% of adults aged ≥ 65 years use the Internet on a typical day, suggesting that when given the necessary tools and training, seniors are enthusiastic technology adopters.5 Thus, it is anticipated that the number of geriatric veterans interested in and able to take advantage of the in-home video visit format will grow rapidly in the near future. The initial enrollment rate at Bedford of 30% is expected to grow as families and providers become more familiar with this modality.

The Bedford VAMC is in an urban/suburban region with multiple Internet service providers, a relatively educated population, and comparatively low levels of poverty. As such, the Bedford VAMC veterans with dementia and their caregivers are likely a best-case scenario population in which to pilot this dementia home telehealth program. If the preliminary success of this pilot program is sustained, expansion to a broader range of home telehealth services, such as social work and home safety assessments, to more rural settings would be the logical next steps.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Thies W, Bleiler L; Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):208-245.

2. Kolanowski AM, Fick D, Waller JL, Shea D. Spouses of persons with dementia: Their healthcare problems, utilization, and costs. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27(5):296-306.

3. Veterans Health Administration Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. Projections of the prevalence and incidence of dementias including Alzheimer’s Disease for the total, enrolled, and patient veteran populations age 65 or over. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www4.va.gov/healthpolicyplanning/dementia/Dem022004.pdf. Published February 20, 2004. Accessed October 10, 2014.

4. Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: Results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475-1483.

5. Zickuhr K, Madden M. Older adults and Internet use. Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project Website. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Older-adults-and-internet-use.aspx. Updated June 6, 2012. Accessed October 17, 2014.

1. Thies W, Bleiler L; Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):208-245.

2. Kolanowski AM, Fick D, Waller JL, Shea D. Spouses of persons with dementia: Their healthcare problems, utilization, and costs. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27(5):296-306.

3. Veterans Health Administration Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. Projections of the prevalence and incidence of dementias including Alzheimer’s Disease for the total, enrolled, and patient veteran populations age 65 or over. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www4.va.gov/healthpolicyplanning/dementia/Dem022004.pdf. Published February 20, 2004. Accessed October 10, 2014.

4. Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: Results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475-1483.

5. Zickuhr K, Madden M. Older adults and Internet use. Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project Website. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Older-adults-and-internet-use.aspx. Updated June 6, 2012. Accessed October 17, 2014.

Introducing a better bleeding risk score in atrial fib

CHICAGO – The ORBIT-AF bleeding risk score is a simple, user-friendly new tool for assessing the risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation, Emily C. O’Brien, Ph.D., announced at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This novel score offers significant advantages over existing bleeding risk scores, including HAS-BLED and ATRIA. Those scores were developed on the basis of small numbers of bleeding events, they show inconsistent performance, and their calculation requires data that’s often not readily accessible in busy daily practice, according to Dr. O’Brien of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C.

The new score was derived from the ORBIT-AF registry, the largest prospective U.S. registry of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

The score was constructed using data on 7,411 AF patients in community practice settings at 173 U.S. sites. All subjects were on oral anticoagulant therapy at baseline. During 2 years of prospective follow-up, 581 patients (7.8%) experienced a major bleeding event as defined by International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria.

After sifting through numerous potential candidate variables, Dr. O’Brien and coinvestigators settled upon five they identified as the most potent and practical baseline predictors of major bleeding risk while on oral anticoagulation. Then they packaged them in a convenient acronym: ORBIT, for Older than 74, Renal insufficiency with an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/minute per/1.73 m2, Bleeding history, Insufficient hemoglobin/hematocrit or anemia, and Treatment with an antiplatelet agent. The two strongest predictors – renal insufficiency and bleeding history– were awarded two points each; the others are worth one point each.

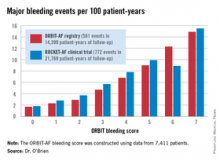

The observed major bleeding rate among patients enrolled in the ORBIT-AF registry rose with an increasing risk score. The same was true upon application of the ORBIT bleeding score to an independent study sample comprised of participants in the ROCKET-AF randomized clinical trial.

Dr. O’Brien also compared the performance of the ORBIT bleeding score to that of two existing bleeding risk scores – HAS-BLED and ATRIA – in the ORBIT-AF and ROCKET-AF cohorts. The simpler, more user friendly ORBIT bleeding score had a C-statistic of 0.67, similar to the 0.64 for HAS-BLED and 0.66 for ATRIA.

Thus, the ORBIT bleeding score is a practical new tool for use alongside the CHA2DS2-VASc stroke risk score to support clinical decision making regarding whether or not to place an individual AF patient on oral anticoagulation, Dr. O’Brien concluded.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study. The ORBIT-AF registry is sponsored by Janssen.

CHICAGO – The ORBIT-AF bleeding risk score is a simple, user-friendly new tool for assessing the risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation, Emily C. O’Brien, Ph.D., announced at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This novel score offers significant advantages over existing bleeding risk scores, including HAS-BLED and ATRIA. Those scores were developed on the basis of small numbers of bleeding events, they show inconsistent performance, and their calculation requires data that’s often not readily accessible in busy daily practice, according to Dr. O’Brien of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C.

The new score was derived from the ORBIT-AF registry, the largest prospective U.S. registry of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

The score was constructed using data on 7,411 AF patients in community practice settings at 173 U.S. sites. All subjects were on oral anticoagulant therapy at baseline. During 2 years of prospective follow-up, 581 patients (7.8%) experienced a major bleeding event as defined by International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria.

After sifting through numerous potential candidate variables, Dr. O’Brien and coinvestigators settled upon five they identified as the most potent and practical baseline predictors of major bleeding risk while on oral anticoagulation. Then they packaged them in a convenient acronym: ORBIT, for Older than 74, Renal insufficiency with an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/minute per/1.73 m2, Bleeding history, Insufficient hemoglobin/hematocrit or anemia, and Treatment with an antiplatelet agent. The two strongest predictors – renal insufficiency and bleeding history– were awarded two points each; the others are worth one point each.

The observed major bleeding rate among patients enrolled in the ORBIT-AF registry rose with an increasing risk score. The same was true upon application of the ORBIT bleeding score to an independent study sample comprised of participants in the ROCKET-AF randomized clinical trial.

Dr. O’Brien also compared the performance of the ORBIT bleeding score to that of two existing bleeding risk scores – HAS-BLED and ATRIA – in the ORBIT-AF and ROCKET-AF cohorts. The simpler, more user friendly ORBIT bleeding score had a C-statistic of 0.67, similar to the 0.64 for HAS-BLED and 0.66 for ATRIA.

Thus, the ORBIT bleeding score is a practical new tool for use alongside the CHA2DS2-VASc stroke risk score to support clinical decision making regarding whether or not to place an individual AF patient on oral anticoagulation, Dr. O’Brien concluded.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study. The ORBIT-AF registry is sponsored by Janssen.

CHICAGO – The ORBIT-AF bleeding risk score is a simple, user-friendly new tool for assessing the risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation, Emily C. O’Brien, Ph.D., announced at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This novel score offers significant advantages over existing bleeding risk scores, including HAS-BLED and ATRIA. Those scores were developed on the basis of small numbers of bleeding events, they show inconsistent performance, and their calculation requires data that’s often not readily accessible in busy daily practice, according to Dr. O’Brien of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C.

The new score was derived from the ORBIT-AF registry, the largest prospective U.S. registry of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

The score was constructed using data on 7,411 AF patients in community practice settings at 173 U.S. sites. All subjects were on oral anticoagulant therapy at baseline. During 2 years of prospective follow-up, 581 patients (7.8%) experienced a major bleeding event as defined by International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria.

After sifting through numerous potential candidate variables, Dr. O’Brien and coinvestigators settled upon five they identified as the most potent and practical baseline predictors of major bleeding risk while on oral anticoagulation. Then they packaged them in a convenient acronym: ORBIT, for Older than 74, Renal insufficiency with an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/minute per/1.73 m2, Bleeding history, Insufficient hemoglobin/hematocrit or anemia, and Treatment with an antiplatelet agent. The two strongest predictors – renal insufficiency and bleeding history– were awarded two points each; the others are worth one point each.

The observed major bleeding rate among patients enrolled in the ORBIT-AF registry rose with an increasing risk score. The same was true upon application of the ORBIT bleeding score to an independent study sample comprised of participants in the ROCKET-AF randomized clinical trial.

Dr. O’Brien also compared the performance of the ORBIT bleeding score to that of two existing bleeding risk scores – HAS-BLED and ATRIA – in the ORBIT-AF and ROCKET-AF cohorts. The simpler, more user friendly ORBIT bleeding score had a C-statistic of 0.67, similar to the 0.64 for HAS-BLED and 0.66 for ATRIA.

Thus, the ORBIT bleeding score is a practical new tool for use alongside the CHA2DS2-VASc stroke risk score to support clinical decision making regarding whether or not to place an individual AF patient on oral anticoagulation, Dr. O’Brien concluded.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study. The ORBIT-AF registry is sponsored by Janssen.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A simple new score is available to assess major bleeding risk in patients with atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation.

Major finding: The major bleeding risk in patients with atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation ranged from 1.7 per 100 patient-years in those with an ORBIT risk score of 0% to 14.9% in those with a maximum score of 7.

Data source: The risk score was derived by analyzing prospective 2-year follow-up data on 7,411 U.S. patients with atrial fibrillation in a large registry.

Disclosures: The ORBIT-AF registry is sponsored by Janssen. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Weak magnetic fields not responsible for leukemia, study suggests

Research first carried out in the 1970s revealed an association between living near overhead power lines and an increased risk of childhood leukemia.

Although some later studies failed to find such a link, the International Agency for Research on Cancer has categorized low-frequency magnetic fields as “possibly carcinogenic.”

However, a mechanism for this association has never been found, and, now, researchers have ruled out one of the prime candidates.

The team studied the effects of weak magnetic fields (WMFs) on key human proteins, including those

crucial for health, and found they have no detectable impact.

The researchers detailed this discovery in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Alex Jones, PhD, of The University of Manchester in the UK, and his colleagues looked at how WMFs affect flavoproteins, which are key to processes vital for healthy human function, such as the nervous system, DNA repair, and the biological clock.

If these proteins malfunction, there are serious knock-on effects for human health. But after subjecting flavoproteins to WMFs in the lab, the researchers found that WMFs have no detectable impact on these proteins.

“There is still some concern among the public about this potential link, which has been found in some studies into cases of childhood leukemia, but without any clear mechanism for why,” Dr Jones said.

“Flavoproteins transfer electrons from one place to another. Along the path the electrons take, very short-lived chemical species known as radical pairs are often created. Biochemical reactions involving radical pairs are considered the most plausible candidates for sensitivity to WMFs, but for them to be so, the reaction conditions have to be right. This research suggests that the correct conditions for biochemical effects of WMFs are likely to be rare in human biology.”

“More work on other possible links will need to be done,” noted study author Nigel Scrutton, PhD, also of the University of Manchester.

“But this study definitely takes us nearer to the point where we can say that power lines, mobile phones, and other similar devices are likely to be safe for humans.” ![]()

Research first carried out in the 1970s revealed an association between living near overhead power lines and an increased risk of childhood leukemia.

Although some later studies failed to find such a link, the International Agency for Research on Cancer has categorized low-frequency magnetic fields as “possibly carcinogenic.”

However, a mechanism for this association has never been found, and, now, researchers have ruled out one of the prime candidates.

The team studied the effects of weak magnetic fields (WMFs) on key human proteins, including those

crucial for health, and found they have no detectable impact.

The researchers detailed this discovery in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Alex Jones, PhD, of The University of Manchester in the UK, and his colleagues looked at how WMFs affect flavoproteins, which are key to processes vital for healthy human function, such as the nervous system, DNA repair, and the biological clock.

If these proteins malfunction, there are serious knock-on effects for human health. But after subjecting flavoproteins to WMFs in the lab, the researchers found that WMFs have no detectable impact on these proteins.

“There is still some concern among the public about this potential link, which has been found in some studies into cases of childhood leukemia, but without any clear mechanism for why,” Dr Jones said.

“Flavoproteins transfer electrons from one place to another. Along the path the electrons take, very short-lived chemical species known as radical pairs are often created. Biochemical reactions involving radical pairs are considered the most plausible candidates for sensitivity to WMFs, but for them to be so, the reaction conditions have to be right. This research suggests that the correct conditions for biochemical effects of WMFs are likely to be rare in human biology.”

“More work on other possible links will need to be done,” noted study author Nigel Scrutton, PhD, also of the University of Manchester.

“But this study definitely takes us nearer to the point where we can say that power lines, mobile phones, and other similar devices are likely to be safe for humans.” ![]()

Research first carried out in the 1970s revealed an association between living near overhead power lines and an increased risk of childhood leukemia.

Although some later studies failed to find such a link, the International Agency for Research on Cancer has categorized low-frequency magnetic fields as “possibly carcinogenic.”

However, a mechanism for this association has never been found, and, now, researchers have ruled out one of the prime candidates.

The team studied the effects of weak magnetic fields (WMFs) on key human proteins, including those

crucial for health, and found they have no detectable impact.

The researchers detailed this discovery in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Alex Jones, PhD, of The University of Manchester in the UK, and his colleagues looked at how WMFs affect flavoproteins, which are key to processes vital for healthy human function, such as the nervous system, DNA repair, and the biological clock.

If these proteins malfunction, there are serious knock-on effects for human health. But after subjecting flavoproteins to WMFs in the lab, the researchers found that WMFs have no detectable impact on these proteins.

“There is still some concern among the public about this potential link, which has been found in some studies into cases of childhood leukemia, but without any clear mechanism for why,” Dr Jones said.

“Flavoproteins transfer electrons from one place to another. Along the path the electrons take, very short-lived chemical species known as radical pairs are often created. Biochemical reactions involving radical pairs are considered the most plausible candidates for sensitivity to WMFs, but for them to be so, the reaction conditions have to be right. This research suggests that the correct conditions for biochemical effects of WMFs are likely to be rare in human biology.”

“More work on other possible links will need to be done,” noted study author Nigel Scrutton, PhD, also of the University of Manchester.

“But this study definitely takes us nearer to the point where we can say that power lines, mobile phones, and other similar devices are likely to be safe for humans.” ![]()

CDC offers pediatric health care providers resources on Ebola in children

Children’s needs differ significantly from the needs of adults, especially when it comes to handling dire situations like the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa that has resulted in a few cases in the United States.

Children may be at increased risk for developing the infection if they have recently traveled to one of the countries experiencing an outbreak. However, since they are very unlikely to be caregivers or participate in funeral activities that raise the risk of exposure, the chances of a child in the United States developing Ebola is very low, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because information about Ebola can be scary and alarming for children, it is important for healthcare providers to recognize and address their developmental and psychological needs to help them better understand facts about the illness and their risk of exposure. It also helps to be prepared just in case the need arises to address a potential Ebola case.

The CDC recommends the following resources to guide health care providers who work with children:

1. Ebola Virus Disease and Children: What US Pediatricians Need to Know

2. What Obstetrician–Gynecologists Should Know About Ebola

3. Information for Healthcare Workers and Settings

4. Algorithm for Evaluation of the Returned Traveler

5. Checklist for Patients Being Evaluated for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in the United States

6. Interim Guidance for Environmental Infection Control in Hospitals for Ebola Virus

7. Ebola Preparedness Considerations for Outpatient/Ambulatory Care Centers

8. Ebola Screening Criteria for Outpatient/Ambulatory Care Centers

Children’s needs differ significantly from the needs of adults, especially when it comes to handling dire situations like the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa that has resulted in a few cases in the United States.

Children may be at increased risk for developing the infection if they have recently traveled to one of the countries experiencing an outbreak. However, since they are very unlikely to be caregivers or participate in funeral activities that raise the risk of exposure, the chances of a child in the United States developing Ebola is very low, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because information about Ebola can be scary and alarming for children, it is important for healthcare providers to recognize and address their developmental and psychological needs to help them better understand facts about the illness and their risk of exposure. It also helps to be prepared just in case the need arises to address a potential Ebola case.

The CDC recommends the following resources to guide health care providers who work with children:

1. Ebola Virus Disease and Children: What US Pediatricians Need to Know

2. What Obstetrician–Gynecologists Should Know About Ebola

3. Information for Healthcare Workers and Settings

4. Algorithm for Evaluation of the Returned Traveler

5. Checklist for Patients Being Evaluated for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in the United States

6. Interim Guidance for Environmental Infection Control in Hospitals for Ebola Virus

7. Ebola Preparedness Considerations for Outpatient/Ambulatory Care Centers

8. Ebola Screening Criteria for Outpatient/Ambulatory Care Centers

Children’s needs differ significantly from the needs of adults, especially when it comes to handling dire situations like the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa that has resulted in a few cases in the United States.

Children may be at increased risk for developing the infection if they have recently traveled to one of the countries experiencing an outbreak. However, since they are very unlikely to be caregivers or participate in funeral activities that raise the risk of exposure, the chances of a child in the United States developing Ebola is very low, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because information about Ebola can be scary and alarming for children, it is important for healthcare providers to recognize and address their developmental and psychological needs to help them better understand facts about the illness and their risk of exposure. It also helps to be prepared just in case the need arises to address a potential Ebola case.

The CDC recommends the following resources to guide health care providers who work with children:

1. Ebola Virus Disease and Children: What US Pediatricians Need to Know

2. What Obstetrician–Gynecologists Should Know About Ebola

3. Information for Healthcare Workers and Settings

4. Algorithm for Evaluation of the Returned Traveler

5. Checklist for Patients Being Evaluated for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in the United States

6. Interim Guidance for Environmental Infection Control in Hospitals for Ebola Virus

7. Ebola Preparedness Considerations for Outpatient/Ambulatory Care Centers

8. Ebola Screening Criteria for Outpatient/Ambulatory Care Centers

Product controls bleeding in kids with hemophilia A

the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN FRANCISCO—A recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) Fc fusion protein is effective for routine prophylaxis and control of bleeding in previously treated children with severe hemophilia A, according to the first phase 3 study of a long-acting FVIII in very young patients.

Prophylactic treatment of hemophilia A with recombinant FVIII requires frequent infusions, up to 3 to 4 per week.

Conventional FVIII replacement therapies have circulating half-lives of 8 to 12 hours.

And children exhibit faster clearance than adults, which may necessitate even more frequent infusions.

Recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein (Eloctate) has been shown to have a 1.5-fold longer half-life when compared with recombinant FVIII (Advate) in a phase 3 study of adults and adolescents.

“In a pediatric population, we demonstrated similar pharmacokinetic safety and efficacy in terms of annualized bleeding rate, with no inhibitors and no adverse events related to the drug,” said Guy Young, MD, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

At the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting, Dr Young and his colleagues reported results observed with recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein in the KIDS A-LONG study (abstract 1494). This phase 3 trial was sponsored by Biogen Idec and Sobi, the companies developing recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein.

The study enrolled 71 males under the age of 12 with severe hemophilia A (< 1 IU/dL endogenous FVIII activity), who had at least 50 prior exposure days to FVIII and no history of FVIII inhibitors.

The patients received twice-weekly prophylactic infusions of the drug, 25 IU/kg on day 1 and 50 IU/kg on day 4. Adjustments to dosing frequency up to once every 2 days and dose to ≤ 80 IU/kg were made as needed.

A subset of 25 patients under age 6 and 35 patients ages 6 to 11 underwent sequential pharmacokinetic evaluations with their prior FVIII therapy (50 IU/kg), followed by the recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein (50 IU/kg).

“The recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein was effective for routine prophylaxis and for control of bleeding,” Dr Young said. “A low annualized bleeding rate was observed in both age cohorts.”

About three-quarters of the patients had a longer dosing interval with recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein compared with their prior FVIII prophylactic dosing interval.

About 90% of the patients were on twice-weekly dosing at the end of the study compared with about 75% infusing at least 3 times a week pre-study, Dr Young said. Some 93% of bleeding episodes were controlled with 1 or 2 injections.

“The recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein had a prolonged half-life and reduced clearance compared with conventional FVIII,” Dr Young noted.

Half-life extension was comparable to that observed in adults and adolescents.

Adverse events were generally similar to those expected for the pediatric hemophilia population.

Some 85.5% of subjects reported at least one adverse event, but no patient discontinued treatment due to an adverse event. Two non-serious events (myalgia and erythematous rash) were related to recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein.

Five patients (7.2%) experienced a total of 7 serious adverse events, which were not related to treatment. There were no reports of anaphylaxis, vascular thrombotic events, or death.

Dr Young said the next step is to test the recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein in previously untreated young hemophilia A patients to determine the rate of immunogenicity.

“We don’t expect to see antibodies in these patients,” he said. ![]()

the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN FRANCISCO—A recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) Fc fusion protein is effective for routine prophylaxis and control of bleeding in previously treated children with severe hemophilia A, according to the first phase 3 study of a long-acting FVIII in very young patients.

Prophylactic treatment of hemophilia A with recombinant FVIII requires frequent infusions, up to 3 to 4 per week.

Conventional FVIII replacement therapies have circulating half-lives of 8 to 12 hours.

And children exhibit faster clearance than adults, which may necessitate even more frequent infusions.

Recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein (Eloctate) has been shown to have a 1.5-fold longer half-life when compared with recombinant FVIII (Advate) in a phase 3 study of adults and adolescents.

“In a pediatric population, we demonstrated similar pharmacokinetic safety and efficacy in terms of annualized bleeding rate, with no inhibitors and no adverse events related to the drug,” said Guy Young, MD, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

At the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting, Dr Young and his colleagues reported results observed with recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein in the KIDS A-LONG study (abstract 1494). This phase 3 trial was sponsored by Biogen Idec and Sobi, the companies developing recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein.

The study enrolled 71 males under the age of 12 with severe hemophilia A (< 1 IU/dL endogenous FVIII activity), who had at least 50 prior exposure days to FVIII and no history of FVIII inhibitors.

The patients received twice-weekly prophylactic infusions of the drug, 25 IU/kg on day 1 and 50 IU/kg on day 4. Adjustments to dosing frequency up to once every 2 days and dose to ≤ 80 IU/kg were made as needed.

A subset of 25 patients under age 6 and 35 patients ages 6 to 11 underwent sequential pharmacokinetic evaluations with their prior FVIII therapy (50 IU/kg), followed by the recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein (50 IU/kg).

“The recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein was effective for routine prophylaxis and for control of bleeding,” Dr Young said. “A low annualized bleeding rate was observed in both age cohorts.”

About three-quarters of the patients had a longer dosing interval with recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein compared with their prior FVIII prophylactic dosing interval.

About 90% of the patients were on twice-weekly dosing at the end of the study compared with about 75% infusing at least 3 times a week pre-study, Dr Young said. Some 93% of bleeding episodes were controlled with 1 or 2 injections.

“The recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein had a prolonged half-life and reduced clearance compared with conventional FVIII,” Dr Young noted.

Half-life extension was comparable to that observed in adults and adolescents.

Adverse events were generally similar to those expected for the pediatric hemophilia population.

Some 85.5% of subjects reported at least one adverse event, but no patient discontinued treatment due to an adverse event. Two non-serious events (myalgia and erythematous rash) were related to recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein.

Five patients (7.2%) experienced a total of 7 serious adverse events, which were not related to treatment. There were no reports of anaphylaxis, vascular thrombotic events, or death.

Dr Young said the next step is to test the recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein in previously untreated young hemophilia A patients to determine the rate of immunogenicity.

“We don’t expect to see antibodies in these patients,” he said. ![]()

the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN FRANCISCO—A recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) Fc fusion protein is effective for routine prophylaxis and control of bleeding in previously treated children with severe hemophilia A, according to the first phase 3 study of a long-acting FVIII in very young patients.

Prophylactic treatment of hemophilia A with recombinant FVIII requires frequent infusions, up to 3 to 4 per week.

Conventional FVIII replacement therapies have circulating half-lives of 8 to 12 hours.

And children exhibit faster clearance than adults, which may necessitate even more frequent infusions.

Recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein (Eloctate) has been shown to have a 1.5-fold longer half-life when compared with recombinant FVIII (Advate) in a phase 3 study of adults and adolescents.

“In a pediatric population, we demonstrated similar pharmacokinetic safety and efficacy in terms of annualized bleeding rate, with no inhibitors and no adverse events related to the drug,” said Guy Young, MD, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

At the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting, Dr Young and his colleagues reported results observed with recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein in the KIDS A-LONG study (abstract 1494). This phase 3 trial was sponsored by Biogen Idec and Sobi, the companies developing recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein.

The study enrolled 71 males under the age of 12 with severe hemophilia A (< 1 IU/dL endogenous FVIII activity), who had at least 50 prior exposure days to FVIII and no history of FVIII inhibitors.

The patients received twice-weekly prophylactic infusions of the drug, 25 IU/kg on day 1 and 50 IU/kg on day 4. Adjustments to dosing frequency up to once every 2 days and dose to ≤ 80 IU/kg were made as needed.

A subset of 25 patients under age 6 and 35 patients ages 6 to 11 underwent sequential pharmacokinetic evaluations with their prior FVIII therapy (50 IU/kg), followed by the recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein (50 IU/kg).

“The recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein was effective for routine prophylaxis and for control of bleeding,” Dr Young said. “A low annualized bleeding rate was observed in both age cohorts.”

About three-quarters of the patients had a longer dosing interval with recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein compared with their prior FVIII prophylactic dosing interval.

About 90% of the patients were on twice-weekly dosing at the end of the study compared with about 75% infusing at least 3 times a week pre-study, Dr Young said. Some 93% of bleeding episodes were controlled with 1 or 2 injections.

“The recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein had a prolonged half-life and reduced clearance compared with conventional FVIII,” Dr Young noted.

Half-life extension was comparable to that observed in adults and adolescents.

Adverse events were generally similar to those expected for the pediatric hemophilia population.

Some 85.5% of subjects reported at least one adverse event, but no patient discontinued treatment due to an adverse event. Two non-serious events (myalgia and erythematous rash) were related to recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein.

Five patients (7.2%) experienced a total of 7 serious adverse events, which were not related to treatment. There were no reports of anaphylaxis, vascular thrombotic events, or death.

Dr Young said the next step is to test the recombinant FVIII Fc fusion protein in previously untreated young hemophilia A patients to determine the rate of immunogenicity.

“We don’t expect to see antibodies in these patients,” he said. ![]()

Granular Cell Tumor

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) tend to present as solitary nodules, not uncommonly affecting the dorsum of the tongue but also involving the skin, breasts, and internal organs.1 Cutaneous GCTs typically present as 0.5- to 3-cm firm nodules with a verrucous or eroded surface.2 They most commonly present in dark-skinned, middle-aged women but have been reported in all age groups and in both sexes.3 Multiple GCTs are reported in up to 25% of cases, rarely in association with LEOPARD syndrome (consisting of lentigines, electrocardiographic abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness).4 Granular cell tumors generally are benign with a metastatic rate of approximately 3%.2

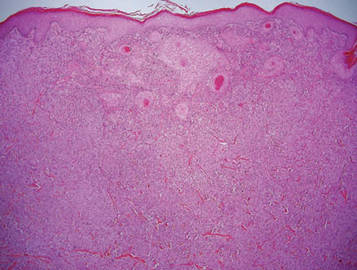

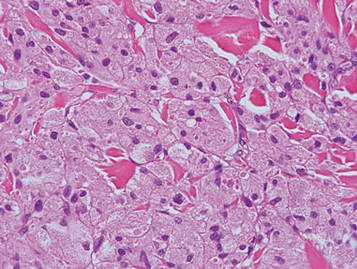

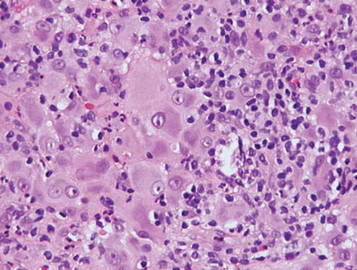

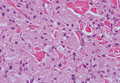

Granular cell tumors are histopathologically characterized by sheets of large polygonal cells with small, round, central nuclei; cytoplasm that is eosinophilic, coarse, and granular, as well as periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant; and distinct cytoplasmic membranes (Figure 1). Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian often generally appear as larger eosinophilic granules surrounded by a clear halo (Figure 2).5 Increased mitotic activity, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphism, and necrosis suggest malignancy.6

|

|

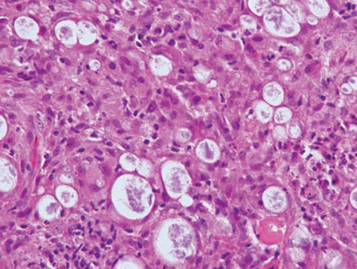

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by sheets of histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm, some with clumped amphophilic bacilli known as globi (Figure 3). Mastocytoma can be distinguished from GCTs by the “fried egg” appearance of the mast cells (Figure 4). Although mast cells have a pale granular cytoplasm, they are smaller and lack pustulo-ovoid bodies and the polygonal shape of GCT cells. Reticulohistiocytoma, on the other hand, has two-toned dusty rose ground glass histiocytes (Figure 5), and xanthelasma can be distinguished histologically from GCT by the presence of a foamy rather than granular cytoplasm (Figure 6).

|

|

|

|

1. Elston DM, Ko C, Ferringer TC, et al, eds. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

3. van de Loo S, Thunnissen E, Postmus P, et al. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity; a case series including a case of metachronous occurrence in the tongue and the lung [published online ahead of print June 1, 2014]. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. doi:10.4317/medoral.19867.

4. Schrader KA, Nelson TN, De Luca A, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors are an associated feature of LEOPARD syndrome caused by mutation in PTPN11. Clin Genet. 2009;75:185-189.

5. Epstein DS, Pashaei S, Hunt E Jr, et al. Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian in granular cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:405-409.

6. Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) tend to present as solitary nodules, not uncommonly affecting the dorsum of the tongue but also involving the skin, breasts, and internal organs.1 Cutaneous GCTs typically present as 0.5- to 3-cm firm nodules with a verrucous or eroded surface.2 They most commonly present in dark-skinned, middle-aged women but have been reported in all age groups and in both sexes.3 Multiple GCTs are reported in up to 25% of cases, rarely in association with LEOPARD syndrome (consisting of lentigines, electrocardiographic abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness).4 Granular cell tumors generally are benign with a metastatic rate of approximately 3%.2

Granular cell tumors are histopathologically characterized by sheets of large polygonal cells with small, round, central nuclei; cytoplasm that is eosinophilic, coarse, and granular, as well as periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant; and distinct cytoplasmic membranes (Figure 1). Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian often generally appear as larger eosinophilic granules surrounded by a clear halo (Figure 2).5 Increased mitotic activity, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphism, and necrosis suggest malignancy.6

|

|

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by sheets of histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm, some with clumped amphophilic bacilli known as globi (Figure 3). Mastocytoma can be distinguished from GCTs by the “fried egg” appearance of the mast cells (Figure 4). Although mast cells have a pale granular cytoplasm, they are smaller and lack pustulo-ovoid bodies and the polygonal shape of GCT cells. Reticulohistiocytoma, on the other hand, has two-toned dusty rose ground glass histiocytes (Figure 5), and xanthelasma can be distinguished histologically from GCT by the presence of a foamy rather than granular cytoplasm (Figure 6).

|

|

|

|

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) tend to present as solitary nodules, not uncommonly affecting the dorsum of the tongue but also involving the skin, breasts, and internal organs.1 Cutaneous GCTs typically present as 0.5- to 3-cm firm nodules with a verrucous or eroded surface.2 They most commonly present in dark-skinned, middle-aged women but have been reported in all age groups and in both sexes.3 Multiple GCTs are reported in up to 25% of cases, rarely in association with LEOPARD syndrome (consisting of lentigines, electrocardiographic abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness).4 Granular cell tumors generally are benign with a metastatic rate of approximately 3%.2

Granular cell tumors are histopathologically characterized by sheets of large polygonal cells with small, round, central nuclei; cytoplasm that is eosinophilic, coarse, and granular, as well as periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant; and distinct cytoplasmic membranes (Figure 1). Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian often generally appear as larger eosinophilic granules surrounded by a clear halo (Figure 2).5 Increased mitotic activity, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphism, and necrosis suggest malignancy.6

|

|

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by sheets of histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm, some with clumped amphophilic bacilli known as globi (Figure 3). Mastocytoma can be distinguished from GCTs by the “fried egg” appearance of the mast cells (Figure 4). Although mast cells have a pale granular cytoplasm, they are smaller and lack pustulo-ovoid bodies and the polygonal shape of GCT cells. Reticulohistiocytoma, on the other hand, has two-toned dusty rose ground glass histiocytes (Figure 5), and xanthelasma can be distinguished histologically from GCT by the presence of a foamy rather than granular cytoplasm (Figure 6).

|

|

|

|

1. Elston DM, Ko C, Ferringer TC, et al, eds. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

3. van de Loo S, Thunnissen E, Postmus P, et al. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity; a case series including a case of metachronous occurrence in the tongue and the lung [published online ahead of print June 1, 2014]. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. doi:10.4317/medoral.19867.

4. Schrader KA, Nelson TN, De Luca A, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors are an associated feature of LEOPARD syndrome caused by mutation in PTPN11. Clin Genet. 2009;75:185-189.

5. Epstein DS, Pashaei S, Hunt E Jr, et al. Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian in granular cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:405-409.

6. Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

1. Elston DM, Ko C, Ferringer TC, et al, eds. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

3. van de Loo S, Thunnissen E, Postmus P, et al. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity; a case series including a case of metachronous occurrence in the tongue and the lung [published online ahead of print June 1, 2014]. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. doi:10.4317/medoral.19867.

4. Schrader KA, Nelson TN, De Luca A, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors are an associated feature of LEOPARD syndrome caused by mutation in PTPN11. Clin Genet. 2009;75:185-189.

5. Epstein DS, Pashaei S, Hunt E Jr, et al. Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian in granular cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:405-409.

6. Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

Two activin receptor fusion proteins show promise in anemia

site of the ASH Annual Meeting

Photo courtesy of ASH

SAN FRANCISCO—Two activin receptor fusion proteins, luspatercept and sotatercept, increased hemoglobin levels and transfusion independence in patients with β-thalassemia and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)/chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), respectively, in phase 2 trials.

Luspatercept is a type IIB activin receptor, while sotatercept is type IIA. Both impact late-stage erythropoiesis and improve anemia.

Investigators reported the trial results at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting.

Luspatercept in β-thalassemia

Antonio G. Piga, MD, of Turin University in Italy, explained that luspatercept binds to GDF11 and other ligands in the TGF-β superfamily and promotes late-stage erythroid maturation.

The study was designed in the US and conducted abroad, he said, because while β-thalassemia is rare in the US, it is not so in Europe.

Investigators evaluated whether luspatercept could increase hemoglobin levels 1.5 g/dL or more for at least 2 weeks in non-transfusion-dependent (NTD) patients.

And in transfusion-dependent (TD) patients, luspatercept was expected to decrease the transfusion burden by 20% or more over 12 weeks.

Thirty patients, 7 TD and 23 NTD, received an injection of luspatercept every 3 weeks for 3 months at doses ranging from 0.2 to 1.0 mg/kg.

The median age was 35, and 53% of patients were male. Eighty-three percent had had a splenectomy.

Luspatercept efficacy

Three-quarters of patients treated with 0.8 to 1.0 mg/kg increased their hemoglobin levels or reduced their transfusion burden.

Of the NTD patients, 8 of 12 with iron overload at baseline experienced a reduction in liver iron concentration of 1 mg or more at 16 weeks.

And in the TD group, “All patients had clinically improved reduction of transfusion dependence,” Dr Piga said.

They had a more than 60% reduction in transfusion burden over 12 weeks. This included 2 patients with β0 β0 genotype, who experienced a 79% and 75% reduction.

“There was a trend to lower liver iron concentration in TD patients,” Dr Piga noted, “except in 1 patient.”

And 5 of 5 TD patients experienced decreases in serum ferritin ranging from 12% to 60%.

Luspatercept safety

Luspatercept did not cause any treatment-related serious or severe adverse events. The most common adverse events were bone pain (20%), headache (17%), myalgia (13%), and asthenia (10%).