User login

Larger and more severe strokes seen with aspirin resistance

Patients with acute ischemic stroke who test positive for aspirin resistance had both larger stroke volume and increased severity, compared with patients without resistance, in an observational study of 311 patients at Korean centers.

Given that previous studies have shown that the use of aspirin is associated with lower stroke severity and decreased infarction growth, the current study’s findings may help to define the effect of aspirin resistance (AR) on stroke severity, since previous studies had provided inconclusive results, Dr. Mi Sun Oh and colleagues at Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, South Korea, wrote in their abstract. The findings were released Feb. 23 in advance of the annual meeting in April of the American Academy of Neurology.

The investigators enrolled patients with acute ischemic stroke confirmed by diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) who had received at least 7 days of aspirin therapy before initial stroke symptoms and had been checked for AR within 24 hours of hospital admission. Patients with high prestroke disability scores (modified Rankin Scale score > 2) were excluded, as were those who were taking another antiplatelet or anticoagulant medication concurrently with aspirin on hospital admission.

The abstract did not report detailed patient characteristics or information about type or dose of aspirin; the full results of the study will be presented at the meeting in Washington.

Enrollees were deemed aspirin resistant if a rapid assay detected greater than 550 Aspirin Reaction Units. DWI-observed stroke volume was assessed via a semiautomated threshold technique, and investigators employed the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score to measure initial stroke severity.

Seventy-eight of the 311 patients (25.1%) had AR. Dr. Oh and colleagues reported that median stroke volume was higher for these patients, compared with the aspirin-sensitive group (2.8 cc vs. 1.6 cc), as was least-square mean on multivariate analysis (1.6 cc [95% CI, 1.1-2.1] vs. 1.1 cc [95% CI, 0.7-1.4], P = .036). Median NIHSS scores were also higher for the AR group (4 vs. 3), indicating greater stroke severity, a result that was confirmed by multivariate analysis.

Aspirin resistance is a complicated and heterogeneous concept, and not a well defined entity, according to vascular neurologist Dr. Philip Gorelick, head of the Hauenstein Neuroscience Center at St. Mary’s Health Care in Grand Rapids, Mich. Dr. Gorelick is an honorary member of the Korean Stroke Society but was not involved in the present study. In an interview, he expanded on the diverse mechanisms that can impede the stroke prevention effect of antiplatelet agents such as aspirin (Stroke Res. Treat. 2013;Article ID 727842 [doi:10.1155/2013/727842]).

In contrast to the traditional notion of “resistance” as an inherent or acquired defense or chemical blockage of a drug, whether by a microbe or the host, aspirin resistance may be either a laboratory-defined lack of inhibition of thromboxane A2, or a clinically-defined entity. In either case, a host of factors may contribute, Dr. Gorelick said. Poor adherence to an aspirin therapy regimen may be a primary contributor to AR. Further, enterically coated aspirin may not be as well absorbed in the gut, leading to lower effective aspirin dosing. A host of other factors, including concurrent medication administration, comorbidities impacting platelet turnover, and genetic polymorphisms may also contribute to aspirin failure.

Although patient characteristics were not reported in this study, Dr. Gorelick did issue a general note of caution: “Another major issue in these types of studies,” he noted, is to determine if “patients are similar in terms of background factors. Patients on aspirin therapy may be more likely to have more severe preexisting vascular disease,” predisposing them to more severe stroke.

The Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and the Republic of Korea supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

Patients with acute ischemic stroke who test positive for aspirin resistance had both larger stroke volume and increased severity, compared with patients without resistance, in an observational study of 311 patients at Korean centers.

Given that previous studies have shown that the use of aspirin is associated with lower stroke severity and decreased infarction growth, the current study’s findings may help to define the effect of aspirin resistance (AR) on stroke severity, since previous studies had provided inconclusive results, Dr. Mi Sun Oh and colleagues at Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, South Korea, wrote in their abstract. The findings were released Feb. 23 in advance of the annual meeting in April of the American Academy of Neurology.

The investigators enrolled patients with acute ischemic stroke confirmed by diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) who had received at least 7 days of aspirin therapy before initial stroke symptoms and had been checked for AR within 24 hours of hospital admission. Patients with high prestroke disability scores (modified Rankin Scale score > 2) were excluded, as were those who were taking another antiplatelet or anticoagulant medication concurrently with aspirin on hospital admission.

The abstract did not report detailed patient characteristics or information about type or dose of aspirin; the full results of the study will be presented at the meeting in Washington.

Enrollees were deemed aspirin resistant if a rapid assay detected greater than 550 Aspirin Reaction Units. DWI-observed stroke volume was assessed via a semiautomated threshold technique, and investigators employed the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score to measure initial stroke severity.

Seventy-eight of the 311 patients (25.1%) had AR. Dr. Oh and colleagues reported that median stroke volume was higher for these patients, compared with the aspirin-sensitive group (2.8 cc vs. 1.6 cc), as was least-square mean on multivariate analysis (1.6 cc [95% CI, 1.1-2.1] vs. 1.1 cc [95% CI, 0.7-1.4], P = .036). Median NIHSS scores were also higher for the AR group (4 vs. 3), indicating greater stroke severity, a result that was confirmed by multivariate analysis.

Aspirin resistance is a complicated and heterogeneous concept, and not a well defined entity, according to vascular neurologist Dr. Philip Gorelick, head of the Hauenstein Neuroscience Center at St. Mary’s Health Care in Grand Rapids, Mich. Dr. Gorelick is an honorary member of the Korean Stroke Society but was not involved in the present study. In an interview, he expanded on the diverse mechanisms that can impede the stroke prevention effect of antiplatelet agents such as aspirin (Stroke Res. Treat. 2013;Article ID 727842 [doi:10.1155/2013/727842]).

In contrast to the traditional notion of “resistance” as an inherent or acquired defense or chemical blockage of a drug, whether by a microbe or the host, aspirin resistance may be either a laboratory-defined lack of inhibition of thromboxane A2, or a clinically-defined entity. In either case, a host of factors may contribute, Dr. Gorelick said. Poor adherence to an aspirin therapy regimen may be a primary contributor to AR. Further, enterically coated aspirin may not be as well absorbed in the gut, leading to lower effective aspirin dosing. A host of other factors, including concurrent medication administration, comorbidities impacting platelet turnover, and genetic polymorphisms may also contribute to aspirin failure.

Although patient characteristics were not reported in this study, Dr. Gorelick did issue a general note of caution: “Another major issue in these types of studies,” he noted, is to determine if “patients are similar in terms of background factors. Patients on aspirin therapy may be more likely to have more severe preexisting vascular disease,” predisposing them to more severe stroke.

The Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and the Republic of Korea supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

Patients with acute ischemic stroke who test positive for aspirin resistance had both larger stroke volume and increased severity, compared with patients without resistance, in an observational study of 311 patients at Korean centers.

Given that previous studies have shown that the use of aspirin is associated with lower stroke severity and decreased infarction growth, the current study’s findings may help to define the effect of aspirin resistance (AR) on stroke severity, since previous studies had provided inconclusive results, Dr. Mi Sun Oh and colleagues at Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, South Korea, wrote in their abstract. The findings were released Feb. 23 in advance of the annual meeting in April of the American Academy of Neurology.

The investigators enrolled patients with acute ischemic stroke confirmed by diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) who had received at least 7 days of aspirin therapy before initial stroke symptoms and had been checked for AR within 24 hours of hospital admission. Patients with high prestroke disability scores (modified Rankin Scale score > 2) were excluded, as were those who were taking another antiplatelet or anticoagulant medication concurrently with aspirin on hospital admission.

The abstract did not report detailed patient characteristics or information about type or dose of aspirin; the full results of the study will be presented at the meeting in Washington.

Enrollees were deemed aspirin resistant if a rapid assay detected greater than 550 Aspirin Reaction Units. DWI-observed stroke volume was assessed via a semiautomated threshold technique, and investigators employed the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score to measure initial stroke severity.

Seventy-eight of the 311 patients (25.1%) had AR. Dr. Oh and colleagues reported that median stroke volume was higher for these patients, compared with the aspirin-sensitive group (2.8 cc vs. 1.6 cc), as was least-square mean on multivariate analysis (1.6 cc [95% CI, 1.1-2.1] vs. 1.1 cc [95% CI, 0.7-1.4], P = .036). Median NIHSS scores were also higher for the AR group (4 vs. 3), indicating greater stroke severity, a result that was confirmed by multivariate analysis.

Aspirin resistance is a complicated and heterogeneous concept, and not a well defined entity, according to vascular neurologist Dr. Philip Gorelick, head of the Hauenstein Neuroscience Center at St. Mary’s Health Care in Grand Rapids, Mich. Dr. Gorelick is an honorary member of the Korean Stroke Society but was not involved in the present study. In an interview, he expanded on the diverse mechanisms that can impede the stroke prevention effect of antiplatelet agents such as aspirin (Stroke Res. Treat. 2013;Article ID 727842 [doi:10.1155/2013/727842]).

In contrast to the traditional notion of “resistance” as an inherent or acquired defense or chemical blockage of a drug, whether by a microbe or the host, aspirin resistance may be either a laboratory-defined lack of inhibition of thromboxane A2, or a clinically-defined entity. In either case, a host of factors may contribute, Dr. Gorelick said. Poor adherence to an aspirin therapy regimen may be a primary contributor to AR. Further, enterically coated aspirin may not be as well absorbed in the gut, leading to lower effective aspirin dosing. A host of other factors, including concurrent medication administration, comorbidities impacting platelet turnover, and genetic polymorphisms may also contribute to aspirin failure.

Although patient characteristics were not reported in this study, Dr. Gorelick did issue a general note of caution: “Another major issue in these types of studies,” he noted, is to determine if “patients are similar in terms of background factors. Patients on aspirin therapy may be more likely to have more severe preexisting vascular disease,” predisposing them to more severe stroke.

The Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and the Republic of Korea supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

FROM THE AAN 2015 ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Volume and severity of ischemic stroke were larger in patients with aspirin resistance.

Major finding: Patients with acute ischemic stroke and aspirin resistance had greater median stroke volume than did aspirin-sensitive patients (2.8 cc vs. 1.6 cc) and had more severe strokes according to median NIHSS score (4 vs. 3).

Data source: Study of 311 patients with MRI-confirmed acute ischemic stroke and at least 7 days of aspirin therapy preceding stroke.

Disclosures: The Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and the Republic of Korea supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

Oral bisphosphonates linked with lower risk of endometrial cancer

A large prospective study found that among 89,918 women aged 50-79 years, bisphosphonate use was inversely associated with age-adjusted endometrial cancer risk, investigators reported. The study was published online Feb. 23 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Crude incidence of endometrial cancer was 12 per 10,000 person-years for nonusers and 8 per 10,000 years for bisphosphonate users (bisphosphonate users: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.94; P = .01). During the median 12.5-year follow up, 1,123 women (1,070 nonusers and 53 users) were diagnosed with endometrial cancer, reported Dr. Polly A. Newcomb and associates (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 Feb. 23 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6842]).

Bisphosphonate use was 2% at baseline and increased to 10% by year 6. It was treated as a time-varying never/ever variable that was updated at 1, 3, and 6 years. Compared with nonusers, bisphosphonate users were slightly older, leaner, more educated, and less likely to smoke.

This observational study is limited by the possibility of confounding factors. Women may have taken oral bisphosphonates because they had high fracture risk due to low endogenous estrogen from low weight, which is associated with low endometrial cancer risk. After the researchers controlled for weight and other confounding factors, such as fracture risk, the statistical analysis yielded similar measures of association (HR 0.80, 0.64 to 1.00; P = .05).

“In summary, our findings suggest that use of bisphosphonates is modestly associated with reduced endometrial cancer risk, a finding consistent with the inverse association between use of this medication and breast cancer risk,” wrote Dr. Newcomb of Fred Hutchinson Cancer and University of Washington Research Center, Seattle, and associates.

Dr. Newcomb and most coauthors had no disclosures. One coauthor reported consulting or advisory roles with Novartis, Pfizer, Genentech, Novo Nordisk, Genomic Health.

A large prospective study found that among 89,918 women aged 50-79 years, bisphosphonate use was inversely associated with age-adjusted endometrial cancer risk, investigators reported. The study was published online Feb. 23 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Crude incidence of endometrial cancer was 12 per 10,000 person-years for nonusers and 8 per 10,000 years for bisphosphonate users (bisphosphonate users: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.94; P = .01). During the median 12.5-year follow up, 1,123 women (1,070 nonusers and 53 users) were diagnosed with endometrial cancer, reported Dr. Polly A. Newcomb and associates (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 Feb. 23 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6842]).

Bisphosphonate use was 2% at baseline and increased to 10% by year 6. It was treated as a time-varying never/ever variable that was updated at 1, 3, and 6 years. Compared with nonusers, bisphosphonate users were slightly older, leaner, more educated, and less likely to smoke.

This observational study is limited by the possibility of confounding factors. Women may have taken oral bisphosphonates because they had high fracture risk due to low endogenous estrogen from low weight, which is associated with low endometrial cancer risk. After the researchers controlled for weight and other confounding factors, such as fracture risk, the statistical analysis yielded similar measures of association (HR 0.80, 0.64 to 1.00; P = .05).

“In summary, our findings suggest that use of bisphosphonates is modestly associated with reduced endometrial cancer risk, a finding consistent with the inverse association between use of this medication and breast cancer risk,” wrote Dr. Newcomb of Fred Hutchinson Cancer and University of Washington Research Center, Seattle, and associates.

Dr. Newcomb and most coauthors had no disclosures. One coauthor reported consulting or advisory roles with Novartis, Pfizer, Genentech, Novo Nordisk, Genomic Health.

A large prospective study found that among 89,918 women aged 50-79 years, bisphosphonate use was inversely associated with age-adjusted endometrial cancer risk, investigators reported. The study was published online Feb. 23 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Crude incidence of endometrial cancer was 12 per 10,000 person-years for nonusers and 8 per 10,000 years for bisphosphonate users (bisphosphonate users: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.94; P = .01). During the median 12.5-year follow up, 1,123 women (1,070 nonusers and 53 users) were diagnosed with endometrial cancer, reported Dr. Polly A. Newcomb and associates (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 Feb. 23 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6842]).

Bisphosphonate use was 2% at baseline and increased to 10% by year 6. It was treated as a time-varying never/ever variable that was updated at 1, 3, and 6 years. Compared with nonusers, bisphosphonate users were slightly older, leaner, more educated, and less likely to smoke.

This observational study is limited by the possibility of confounding factors. Women may have taken oral bisphosphonates because they had high fracture risk due to low endogenous estrogen from low weight, which is associated with low endometrial cancer risk. After the researchers controlled for weight and other confounding factors, such as fracture risk, the statistical analysis yielded similar measures of association (HR 0.80, 0.64 to 1.00; P = .05).

“In summary, our findings suggest that use of bisphosphonates is modestly associated with reduced endometrial cancer risk, a finding consistent with the inverse association between use of this medication and breast cancer risk,” wrote Dr. Newcomb of Fred Hutchinson Cancer and University of Washington Research Center, Seattle, and associates.

Dr. Newcomb and most coauthors had no disclosures. One coauthor reported consulting or advisory roles with Novartis, Pfizer, Genentech, Novo Nordisk, Genomic Health.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Oral bisphosphonate use was modestly associated with reduced risk of endometrial cancer.

Major finding: Risk of endometrial cancer was lower among bisphosphonate users: hazard ratio 0.76, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.94, P = .01.

Data source: The Women’s Health Initiative prospective cohort of 89,918 women with 1,123 cases of incident endometrial cancer.

Disclosures: Dr. Newcomb and most coauthors had no disclosures. One coauthor reported consulting or advisory roles with Novartis, Pfizer, Genentech, Novo Nordisk, Genomic Health.

Outcomes: Getting to the patient’s bottom line

It’s easy to get so caught up in our day-to-day routines. At the hospital, we’re meeting core measures, documenting correctly, following clinical guidelines, and simply striving to stay up to date with the literature. At home, there are soccer games, recitals, and homework – and some rare personal time. We often shift to automatic pilot in a desperate attempt to balance the seemingly never-ending demands.

But does the very nature of our hectic lives sometimes prevent us from seeing the bigger picture, especially when it comes to the things that are really important to our patients? Yes, we know what lab values automatically trigger an order for a statin, and what ejection fraction on the echocardiogram warrants an ACE inhibitor, but how often do we really take the time to find out about the outcomes that are important to our patients? Sometimes they aren’t the evidence-based clinical outcomes we are trying to reproduce with our treatments.

For many patients, the desired outcome is to feel better, plain and simple. All the fancy lingo and drugs with unpronounceable names and unintelligible indications can be overwhelming. They make some patients shut down, and ultimately shut us out. We may not even realize it until our patients are readmitted as a result of noncompliance with our well-thought-out treatment plans.

There are our male patients who rarely take their blood pressure medicine because of the side effect of sexual dysfunction. And then there are those patients who don’t take their medications or see their doctors regularly because they just cannot afford it. While they seem to be in agreement with the follow-up plan for medical visits and testing, patients may be ashamed to admit they are uninsured or underinsured. They know they will never be adherent because they just cannot afford the costs of our treatment plan.

Instead of getting frustrated with our noncompliant patients, we could better serve them by getting more personal – gaining their trust as we carefully and respectfully uncover the layers of the limitations they face and the outcomes that matter to them. We need to aim to be viewed as our patients’ caring advocates and not just aloof professionals with no clue about their daily struggles.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

It’s easy to get so caught up in our day-to-day routines. At the hospital, we’re meeting core measures, documenting correctly, following clinical guidelines, and simply striving to stay up to date with the literature. At home, there are soccer games, recitals, and homework – and some rare personal time. We often shift to automatic pilot in a desperate attempt to balance the seemingly never-ending demands.

But does the very nature of our hectic lives sometimes prevent us from seeing the bigger picture, especially when it comes to the things that are really important to our patients? Yes, we know what lab values automatically trigger an order for a statin, and what ejection fraction on the echocardiogram warrants an ACE inhibitor, but how often do we really take the time to find out about the outcomes that are important to our patients? Sometimes they aren’t the evidence-based clinical outcomes we are trying to reproduce with our treatments.

For many patients, the desired outcome is to feel better, plain and simple. All the fancy lingo and drugs with unpronounceable names and unintelligible indications can be overwhelming. They make some patients shut down, and ultimately shut us out. We may not even realize it until our patients are readmitted as a result of noncompliance with our well-thought-out treatment plans.

There are our male patients who rarely take their blood pressure medicine because of the side effect of sexual dysfunction. And then there are those patients who don’t take their medications or see their doctors regularly because they just cannot afford it. While they seem to be in agreement with the follow-up plan for medical visits and testing, patients may be ashamed to admit they are uninsured or underinsured. They know they will never be adherent because they just cannot afford the costs of our treatment plan.

Instead of getting frustrated with our noncompliant patients, we could better serve them by getting more personal – gaining their trust as we carefully and respectfully uncover the layers of the limitations they face and the outcomes that matter to them. We need to aim to be viewed as our patients’ caring advocates and not just aloof professionals with no clue about their daily struggles.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

It’s easy to get so caught up in our day-to-day routines. At the hospital, we’re meeting core measures, documenting correctly, following clinical guidelines, and simply striving to stay up to date with the literature. At home, there are soccer games, recitals, and homework – and some rare personal time. We often shift to automatic pilot in a desperate attempt to balance the seemingly never-ending demands.

But does the very nature of our hectic lives sometimes prevent us from seeing the bigger picture, especially when it comes to the things that are really important to our patients? Yes, we know what lab values automatically trigger an order for a statin, and what ejection fraction on the echocardiogram warrants an ACE inhibitor, but how often do we really take the time to find out about the outcomes that are important to our patients? Sometimes they aren’t the evidence-based clinical outcomes we are trying to reproduce with our treatments.

For many patients, the desired outcome is to feel better, plain and simple. All the fancy lingo and drugs with unpronounceable names and unintelligible indications can be overwhelming. They make some patients shut down, and ultimately shut us out. We may not even realize it until our patients are readmitted as a result of noncompliance with our well-thought-out treatment plans.

There are our male patients who rarely take their blood pressure medicine because of the side effect of sexual dysfunction. And then there are those patients who don’t take their medications or see their doctors regularly because they just cannot afford it. While they seem to be in agreement with the follow-up plan for medical visits and testing, patients may be ashamed to admit they are uninsured or underinsured. They know they will never be adherent because they just cannot afford the costs of our treatment plan.

Instead of getting frustrated with our noncompliant patients, we could better serve them by getting more personal – gaining their trust as we carefully and respectfully uncover the layers of the limitations they face and the outcomes that matter to them. We need to aim to be viewed as our patients’ caring advocates and not just aloof professionals with no clue about their daily struggles.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

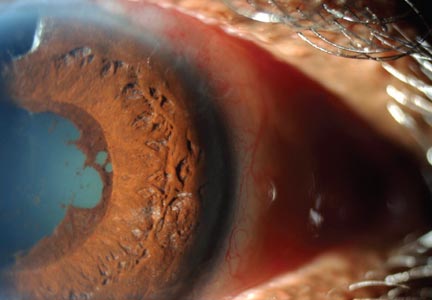

Woman, 64, With Eye Pain, Swelling, and Tearing

A 64-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a two-to-three-week history of significant pain, swelling, and excessive tearing of the left eye. The patient had a persistent cough but denied wheezing or shortness of breath.

Medical history was remarkable for uveitis, severe recurrent sinusitis, and allergic rhinitis. The patient reported that she had been exposed to benzene and burning paint fumes about 10 years ago but had no known symptoms or problems at the time.

Vital signs included a temperature of 97.0°F; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; pulse, 100 beats/min; and blood pressure, 144/80 mm Hg. Her height was 65 in; weight, 122 lb; and O2 saturation, 100% on room air.

Physical examination revealed a left palpebral lacrimal mass with an enlarged lacrimal gland. The left lacrimal gland and conjunctiva were mildly erythematous, with a cobblestone appearance. The right eye was stable, with no significant inflammation. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light and accommodation. Extraocular movements were intact. Nasal turbinates were swollen and mildly erythematous. Oropharynx was stable and tonsils absent. Left parotid gland was slightly swollen and tender.

The neck was supple with no jugular venous distension. Palpable cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, measuring approximately 1.5 x 1.5 cm bilaterally, was present. The lungs were clear to auscultation and percussion. The heart rate and rhythm were regular, with normal S1 and S2 sounds. The abdomen was soft, nontender, and without hepatosplenomegaly. Extremities were stable, with no rashes, lesions, or cutaneous skin nodules.

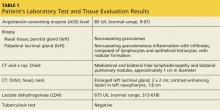

The patient was referred to a specialist for a complete ophthalmologic examination and further work-up. This included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, tissue biopsies of the affected lacrimal gland and parotid gland, CT, and x-rays; results are shown in Table 1. In addition, the patient’s persistent nasosinus congestion was determined, by otolaryngologic consultation, to be the result of a deviated septum, for which she underwent endoscopic nasal septal repair with tissue biopsy.

The lacrimal gland biopsy led to a diagnosis of chronic noncaseating granulomatous dacryoadenitis, with an extensive area of necrosis. Significant findings included histiocytes and discrete nodules in the gland. Biopsies of the parotid gland and nasal tissue also identified noncaseating granulomas.

The patient’s test results suggested several possible diagnoses, including

• Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

• Tuberculosis (TB) or similar pulmonary infectious disease

• Sarcoidosis (ocular and/or pulmonary)

Continue for differential diagnosis >>

DISCUSSION

Differential diagnosis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis. GPA, also known as Wegener granulomatosis, is characterized by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with necrotizing vasculitis, usually of small and medium vessels; ocular involvement is frequent.1 Ocular granulomas of GPA can be mistaken for those caused by other diseases, such as mycobacterial or syphilitic infection or idiopathic uveitis.2

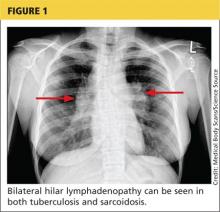

Tuberculosis. Common symptoms of TB include fever, cough, dyspnea, weight loss, malaise, and fatigue. Granulomas are typically necrotizing but are occasionally nonnecrotizing.3 TB can manifest with hilar and diffuse lymphadenopathy,4 which the patient’s chest imaging revealed (see Figure 1). Granulomas produced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and atypical mycobacteria are similar histopathologically to sarcoidosis granulomas, complicating the diagnostic process.5

Next page: Sarcoidosis >>

Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease characterized by noncaseating epithelioid granulomas in affected organs.6 More than 90% of patients with sarcoidosis present with pulmonary symptoms, including shortness of breath, cough, and pleuritic chest pain.6-8 Ocular manifestations, such as uveitis, iritis, or conjunctivitis, are less common, developing in 30% to 60% of patients.2,9,10 In addition, rashes, lesions, or cutaneous skin nodules, including erythema nodosum and lupus pernio, are seen in 25% to 35% of patients.2,6

In up to two-thirds of patients, sarcoidosis resolves spontaneously2; in others, it may become chronic and progressive.4 Patients may have few or no symptoms; some require no treatment, while others may be severely affected by the disease.

Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis generally manifests as uveitis, most commonly in the anterior chamber. Uveitis is a potentially vision-threatening inflammatory disease involving both the uveal tract and adjacent structures.11 In a review of records for 2,619 patients with uveitis, 59.9% had anterior disease, of whom 2.1% were diagnosed with sarcoidosis.11

While the etiology of sarcoidosis continues to be studied,7 the prevailing theory is that, in genetically predisposed individuals, sarcoidosis is a cell-mediated immune response to as-yet unknown antigen triggers that leads to granuloma formation.3,6,7

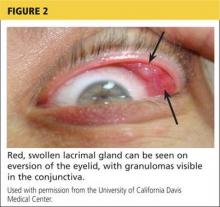

CD4+ activated T-cells stimulate the immune reaction against an antigen, producing cytokines that activate immune cells (eg, B cells, macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils).2 Immune cells accumulate and aggregate at antigen sites in an exaggerated response, resulting in the formation of granulomas (see Figure 2).7,12,13

Infectious agents have long been investigated as possible causative agents in sarcoidosis, with Mycobacterium species most frequently identified.5 Additional possibilities include Propionibacterium acnes (found predominantly in skin lesions) and herpesviruses, although viruses are not known to cause epitheliod granulomas.14

Environmental triggers have also been explored. One large study found a possible association between exposure to insecticides, agricultural environments, and microbial bioaerosols and sarcoidosis.15

The difficulty of pinpointing a single etiology for sarcoidosis—with its varying clinical manifestations, severity, and disease course—suggests that sarcoidosis may be a spectrum of disorders caused by the interaction of genetic, immunologic, infectious, and environmental factors.14

Next page: Diagnosis of sarcoidosis >>

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is based on clinical and radiologic features, histologic evidence of noncaseating granulomas, and exclusion of other possible causes of granulomas.2,12 In addition, when ocular sarcoidosis is suspected, other possible causes of uveitis must be excluded.

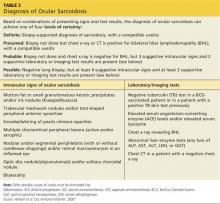

In an effort to address these challenges, the International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) developed a standardized approach to diagnosis.9 The group first identified seven intraocular signs of ocular sarcoidosis and then five laboratory or imaging tests that are of value in making the diagnosis in patients with these signs. Last, they established four levels of certainty for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis, based on these signs, tests, and biopsy results, if available (see Table 2).

Treatment

Anterior uveitis in sarcoidosis is usually treated initially with a topical corticosteroid (eg, prednisolone or difluprednate drops), particularly if the patient’s symptoms are mild. In more severe cases (eg, posterior or bilateral uveitis) or when topical corticosteroids are ineffective, systemic (oral) corticosteroids (eg, prednisone) may be initiated. Topical therapy can also be added to an oral regimen as a means of decreasing the oral dosage and thereby reducing the adverse effects of systemic corticosteroids. When the patient’s disease is refractory to corticosteroids or there are concerns about long-term adverse effects, chronic cases may be treated with immunosuppressive agents (eg, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil). Finally, refractory cases of ocular sarcoidosis may be treated with anti–tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) biologic agents such as infliximab and adalimumab.10,17

Continue for case patient outcome >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

Histologic evaluation of tissue from the lacrimal gland, parotid gland, and sinus cavity revealed inflammatory noncaseating granulomas, strongly suggestive of sarcoidosis. Diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis was based on the noncaseating granulomas in the lacrimal gland.9,16 Pulmonary sarcoidosis was also diagnosed, based on the presence of hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.7

The mass in the patient’s lacrimal gland was surgically removed. She was treated with a combination of topical and oral corticosteroids tapered over two weeks, which induced remission of her ocular disease. The patient will be seen annually by an ophthalmologic specialist and was advised to contact her clinician immediately if acute ocular symptoms recurred.10,17

The patient’s persistent cough was determined to be secondary to acute bronchitis, rather than to her pulmonary sarcoidosis, which required no treatment. She received a short course of antibiotics and antitussives for her bronchitis. Systemic corticosteroid treatment of her ocular sarcoidosis also had the benefit of decreasing the size of her pulmonary nodules. She will be followed with annual CT and chest x-rays to monitor the status of her hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and the nodules.3 Periodic pulmonary function testing will also be performed.7

Continue for conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

The elusive nature of the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is well documented in the medical literature. In this case, histologic evaluation of biopsied tissue, correlated with clinical symptoms and radiographic findings, were essential in making the diagnosis.

Primary care providers may be the first to evaluate patients with ocular sarcoidosis and will oversee long-term management. Patients who present with symptoms of eye pain, visual disturbances, abnormal inflammatory ocular features, or swollen lacrimal glands should be referred to an ophthalmologic specialist for further evaluation.

REFERENCES

1. Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1-11.

2. Culver DA. Sarcoidosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2012;32(4):487-511.

3. Spagnolo P, Luppi F, Roversi P, et al. Sarcoidosis: challenging diagnostic aspects of an old disease. Am J Med. 2012;125(2):118-125.

4. Dempsey OJ, Peterson EW, Kerr KM, Denison AR. Sarcoidosis. BMJ. 2009;339:620-625.

5. Brownell I, Ramirez-Valle F, Sanchez M, Prystowsky S. Evidence for mycobacteria in sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45(5):899-905.

6. Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305(4):391-399.

7. Baughman MD, Culver DA, Judson MA. A concise review of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(5):573-581.

8. Koyama T, Ueda H, Togashi K, et al. Radiologic manifestations of sarcoidosis in various organs. Radiographics. 2004;24(1):87-104.

9. Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M; for the Scientific Committee of First International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: results of the first International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS). Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009; 17(3):160-169.

10. Jamilloux Y, Kodjikian L, Broussolle C, Seve P. Sarcoidosis and uveitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(8):840-849.

11. Barisani-Asenbauer T, Maca SM, Mejdoubi L, et al. Uveitis—a rare disease often associated with systemic diseases and infections—a systematic review of 2619 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:57.

12. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. New Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2153-2165.

13. Fontenot A, King T. Pathogenesis of sarcoidosis. www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-of-sarcoidosis?source=search_result&search=Pathogenesis+of+sarcoidosis&selectedTitle=1%7E150. Accessed February 17, 2015.

14. Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, Eckstein C. Etiology of sarcoidosis: does infection play a role? Yale J Biol Med. 2012;85(1):133-141.

15. Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, et al; for the ACCESS Research Group. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis. Environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1324-1330.

16. Kawaguchi T, Hanada A, Horie S, et al. Evaluation of characteristic ocular signs and systemic investigations in ocular sarcoidosis patients. Jpn J Opthalmol. 2007;51(2):121-126.

17. Bodaghi B, Touitou V, Fardeau C, et al. Ocular sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41(6 Pt 2):e349-e354.

A 64-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a two-to-three-week history of significant pain, swelling, and excessive tearing of the left eye. The patient had a persistent cough but denied wheezing or shortness of breath.

Medical history was remarkable for uveitis, severe recurrent sinusitis, and allergic rhinitis. The patient reported that she had been exposed to benzene and burning paint fumes about 10 years ago but had no known symptoms or problems at the time.

Vital signs included a temperature of 97.0°F; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; pulse, 100 beats/min; and blood pressure, 144/80 mm Hg. Her height was 65 in; weight, 122 lb; and O2 saturation, 100% on room air.

Physical examination revealed a left palpebral lacrimal mass with an enlarged lacrimal gland. The left lacrimal gland and conjunctiva were mildly erythematous, with a cobblestone appearance. The right eye was stable, with no significant inflammation. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light and accommodation. Extraocular movements were intact. Nasal turbinates were swollen and mildly erythematous. Oropharynx was stable and tonsils absent. Left parotid gland was slightly swollen and tender.

The neck was supple with no jugular venous distension. Palpable cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, measuring approximately 1.5 x 1.5 cm bilaterally, was present. The lungs were clear to auscultation and percussion. The heart rate and rhythm were regular, with normal S1 and S2 sounds. The abdomen was soft, nontender, and without hepatosplenomegaly. Extremities were stable, with no rashes, lesions, or cutaneous skin nodules.

The patient was referred to a specialist for a complete ophthalmologic examination and further work-up. This included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, tissue biopsies of the affected lacrimal gland and parotid gland, CT, and x-rays; results are shown in Table 1. In addition, the patient’s persistent nasosinus congestion was determined, by otolaryngologic consultation, to be the result of a deviated septum, for which she underwent endoscopic nasal septal repair with tissue biopsy.

The lacrimal gland biopsy led to a diagnosis of chronic noncaseating granulomatous dacryoadenitis, with an extensive area of necrosis. Significant findings included histiocytes and discrete nodules in the gland. Biopsies of the parotid gland and nasal tissue also identified noncaseating granulomas.

The patient’s test results suggested several possible diagnoses, including

• Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

• Tuberculosis (TB) or similar pulmonary infectious disease

• Sarcoidosis (ocular and/or pulmonary)

Continue for differential diagnosis >>

DISCUSSION

Differential diagnosis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis. GPA, also known as Wegener granulomatosis, is characterized by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with necrotizing vasculitis, usually of small and medium vessels; ocular involvement is frequent.1 Ocular granulomas of GPA can be mistaken for those caused by other diseases, such as mycobacterial or syphilitic infection or idiopathic uveitis.2

Tuberculosis. Common symptoms of TB include fever, cough, dyspnea, weight loss, malaise, and fatigue. Granulomas are typically necrotizing but are occasionally nonnecrotizing.3 TB can manifest with hilar and diffuse lymphadenopathy,4 which the patient’s chest imaging revealed (see Figure 1). Granulomas produced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and atypical mycobacteria are similar histopathologically to sarcoidosis granulomas, complicating the diagnostic process.5

Next page: Sarcoidosis >>

Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease characterized by noncaseating epithelioid granulomas in affected organs.6 More than 90% of patients with sarcoidosis present with pulmonary symptoms, including shortness of breath, cough, and pleuritic chest pain.6-8 Ocular manifestations, such as uveitis, iritis, or conjunctivitis, are less common, developing in 30% to 60% of patients.2,9,10 In addition, rashes, lesions, or cutaneous skin nodules, including erythema nodosum and lupus pernio, are seen in 25% to 35% of patients.2,6

In up to two-thirds of patients, sarcoidosis resolves spontaneously2; in others, it may become chronic and progressive.4 Patients may have few or no symptoms; some require no treatment, while others may be severely affected by the disease.

Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis generally manifests as uveitis, most commonly in the anterior chamber. Uveitis is a potentially vision-threatening inflammatory disease involving both the uveal tract and adjacent structures.11 In a review of records for 2,619 patients with uveitis, 59.9% had anterior disease, of whom 2.1% were diagnosed with sarcoidosis.11

While the etiology of sarcoidosis continues to be studied,7 the prevailing theory is that, in genetically predisposed individuals, sarcoidosis is a cell-mediated immune response to as-yet unknown antigen triggers that leads to granuloma formation.3,6,7

CD4+ activated T-cells stimulate the immune reaction against an antigen, producing cytokines that activate immune cells (eg, B cells, macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils).2 Immune cells accumulate and aggregate at antigen sites in an exaggerated response, resulting in the formation of granulomas (see Figure 2).7,12,13

Infectious agents have long been investigated as possible causative agents in sarcoidosis, with Mycobacterium species most frequently identified.5 Additional possibilities include Propionibacterium acnes (found predominantly in skin lesions) and herpesviruses, although viruses are not known to cause epitheliod granulomas.14

Environmental triggers have also been explored. One large study found a possible association between exposure to insecticides, agricultural environments, and microbial bioaerosols and sarcoidosis.15

The difficulty of pinpointing a single etiology for sarcoidosis—with its varying clinical manifestations, severity, and disease course—suggests that sarcoidosis may be a spectrum of disorders caused by the interaction of genetic, immunologic, infectious, and environmental factors.14

Next page: Diagnosis of sarcoidosis >>

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is based on clinical and radiologic features, histologic evidence of noncaseating granulomas, and exclusion of other possible causes of granulomas.2,12 In addition, when ocular sarcoidosis is suspected, other possible causes of uveitis must be excluded.

In an effort to address these challenges, the International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) developed a standardized approach to diagnosis.9 The group first identified seven intraocular signs of ocular sarcoidosis and then five laboratory or imaging tests that are of value in making the diagnosis in patients with these signs. Last, they established four levels of certainty for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis, based on these signs, tests, and biopsy results, if available (see Table 2).

Treatment

Anterior uveitis in sarcoidosis is usually treated initially with a topical corticosteroid (eg, prednisolone or difluprednate drops), particularly if the patient’s symptoms are mild. In more severe cases (eg, posterior or bilateral uveitis) or when topical corticosteroids are ineffective, systemic (oral) corticosteroids (eg, prednisone) may be initiated. Topical therapy can also be added to an oral regimen as a means of decreasing the oral dosage and thereby reducing the adverse effects of systemic corticosteroids. When the patient’s disease is refractory to corticosteroids or there are concerns about long-term adverse effects, chronic cases may be treated with immunosuppressive agents (eg, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil). Finally, refractory cases of ocular sarcoidosis may be treated with anti–tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) biologic agents such as infliximab and adalimumab.10,17

Continue for case patient outcome >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

Histologic evaluation of tissue from the lacrimal gland, parotid gland, and sinus cavity revealed inflammatory noncaseating granulomas, strongly suggestive of sarcoidosis. Diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis was based on the noncaseating granulomas in the lacrimal gland.9,16 Pulmonary sarcoidosis was also diagnosed, based on the presence of hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.7

The mass in the patient’s lacrimal gland was surgically removed. She was treated with a combination of topical and oral corticosteroids tapered over two weeks, which induced remission of her ocular disease. The patient will be seen annually by an ophthalmologic specialist and was advised to contact her clinician immediately if acute ocular symptoms recurred.10,17

The patient’s persistent cough was determined to be secondary to acute bronchitis, rather than to her pulmonary sarcoidosis, which required no treatment. She received a short course of antibiotics and antitussives for her bronchitis. Systemic corticosteroid treatment of her ocular sarcoidosis also had the benefit of decreasing the size of her pulmonary nodules. She will be followed with annual CT and chest x-rays to monitor the status of her hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and the nodules.3 Periodic pulmonary function testing will also be performed.7

Continue for conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

The elusive nature of the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is well documented in the medical literature. In this case, histologic evaluation of biopsied tissue, correlated with clinical symptoms and radiographic findings, were essential in making the diagnosis.

Primary care providers may be the first to evaluate patients with ocular sarcoidosis and will oversee long-term management. Patients who present with symptoms of eye pain, visual disturbances, abnormal inflammatory ocular features, or swollen lacrimal glands should be referred to an ophthalmologic specialist for further evaluation.

REFERENCES

1. Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1-11.

2. Culver DA. Sarcoidosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2012;32(4):487-511.

3. Spagnolo P, Luppi F, Roversi P, et al. Sarcoidosis: challenging diagnostic aspects of an old disease. Am J Med. 2012;125(2):118-125.

4. Dempsey OJ, Peterson EW, Kerr KM, Denison AR. Sarcoidosis. BMJ. 2009;339:620-625.

5. Brownell I, Ramirez-Valle F, Sanchez M, Prystowsky S. Evidence for mycobacteria in sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45(5):899-905.

6. Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305(4):391-399.

7. Baughman MD, Culver DA, Judson MA. A concise review of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(5):573-581.

8. Koyama T, Ueda H, Togashi K, et al. Radiologic manifestations of sarcoidosis in various organs. Radiographics. 2004;24(1):87-104.

9. Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M; for the Scientific Committee of First International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: results of the first International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS). Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009; 17(3):160-169.

10. Jamilloux Y, Kodjikian L, Broussolle C, Seve P. Sarcoidosis and uveitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(8):840-849.

11. Barisani-Asenbauer T, Maca SM, Mejdoubi L, et al. Uveitis—a rare disease often associated with systemic diseases and infections—a systematic review of 2619 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:57.

12. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. New Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2153-2165.

13. Fontenot A, King T. Pathogenesis of sarcoidosis. www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-of-sarcoidosis?source=search_result&search=Pathogenesis+of+sarcoidosis&selectedTitle=1%7E150. Accessed February 17, 2015.

14. Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, Eckstein C. Etiology of sarcoidosis: does infection play a role? Yale J Biol Med. 2012;85(1):133-141.

15. Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, et al; for the ACCESS Research Group. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis. Environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1324-1330.

16. Kawaguchi T, Hanada A, Horie S, et al. Evaluation of characteristic ocular signs and systemic investigations in ocular sarcoidosis patients. Jpn J Opthalmol. 2007;51(2):121-126.

17. Bodaghi B, Touitou V, Fardeau C, et al. Ocular sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41(6 Pt 2):e349-e354.

A 64-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a two-to-three-week history of significant pain, swelling, and excessive tearing of the left eye. The patient had a persistent cough but denied wheezing or shortness of breath.

Medical history was remarkable for uveitis, severe recurrent sinusitis, and allergic rhinitis. The patient reported that she had been exposed to benzene and burning paint fumes about 10 years ago but had no known symptoms or problems at the time.

Vital signs included a temperature of 97.0°F; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; pulse, 100 beats/min; and blood pressure, 144/80 mm Hg. Her height was 65 in; weight, 122 lb; and O2 saturation, 100% on room air.

Physical examination revealed a left palpebral lacrimal mass with an enlarged lacrimal gland. The left lacrimal gland and conjunctiva were mildly erythematous, with a cobblestone appearance. The right eye was stable, with no significant inflammation. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light and accommodation. Extraocular movements were intact. Nasal turbinates were swollen and mildly erythematous. Oropharynx was stable and tonsils absent. Left parotid gland was slightly swollen and tender.

The neck was supple with no jugular venous distension. Palpable cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, measuring approximately 1.5 x 1.5 cm bilaterally, was present. The lungs were clear to auscultation and percussion. The heart rate and rhythm were regular, with normal S1 and S2 sounds. The abdomen was soft, nontender, and without hepatosplenomegaly. Extremities were stable, with no rashes, lesions, or cutaneous skin nodules.

The patient was referred to a specialist for a complete ophthalmologic examination and further work-up. This included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, tissue biopsies of the affected lacrimal gland and parotid gland, CT, and x-rays; results are shown in Table 1. In addition, the patient’s persistent nasosinus congestion was determined, by otolaryngologic consultation, to be the result of a deviated septum, for which she underwent endoscopic nasal septal repair with tissue biopsy.

The lacrimal gland biopsy led to a diagnosis of chronic noncaseating granulomatous dacryoadenitis, with an extensive area of necrosis. Significant findings included histiocytes and discrete nodules in the gland. Biopsies of the parotid gland and nasal tissue also identified noncaseating granulomas.

The patient’s test results suggested several possible diagnoses, including

• Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

• Tuberculosis (TB) or similar pulmonary infectious disease

• Sarcoidosis (ocular and/or pulmonary)

Continue for differential diagnosis >>

DISCUSSION

Differential diagnosis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis. GPA, also known as Wegener granulomatosis, is characterized by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with necrotizing vasculitis, usually of small and medium vessels; ocular involvement is frequent.1 Ocular granulomas of GPA can be mistaken for those caused by other diseases, such as mycobacterial or syphilitic infection or idiopathic uveitis.2

Tuberculosis. Common symptoms of TB include fever, cough, dyspnea, weight loss, malaise, and fatigue. Granulomas are typically necrotizing but are occasionally nonnecrotizing.3 TB can manifest with hilar and diffuse lymphadenopathy,4 which the patient’s chest imaging revealed (see Figure 1). Granulomas produced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and atypical mycobacteria are similar histopathologically to sarcoidosis granulomas, complicating the diagnostic process.5

Next page: Sarcoidosis >>

Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease characterized by noncaseating epithelioid granulomas in affected organs.6 More than 90% of patients with sarcoidosis present with pulmonary symptoms, including shortness of breath, cough, and pleuritic chest pain.6-8 Ocular manifestations, such as uveitis, iritis, or conjunctivitis, are less common, developing in 30% to 60% of patients.2,9,10 In addition, rashes, lesions, or cutaneous skin nodules, including erythema nodosum and lupus pernio, are seen in 25% to 35% of patients.2,6

In up to two-thirds of patients, sarcoidosis resolves spontaneously2; in others, it may become chronic and progressive.4 Patients may have few or no symptoms; some require no treatment, while others may be severely affected by the disease.

Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis generally manifests as uveitis, most commonly in the anterior chamber. Uveitis is a potentially vision-threatening inflammatory disease involving both the uveal tract and adjacent structures.11 In a review of records for 2,619 patients with uveitis, 59.9% had anterior disease, of whom 2.1% were diagnosed with sarcoidosis.11

While the etiology of sarcoidosis continues to be studied,7 the prevailing theory is that, in genetically predisposed individuals, sarcoidosis is a cell-mediated immune response to as-yet unknown antigen triggers that leads to granuloma formation.3,6,7

CD4+ activated T-cells stimulate the immune reaction against an antigen, producing cytokines that activate immune cells (eg, B cells, macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils).2 Immune cells accumulate and aggregate at antigen sites in an exaggerated response, resulting in the formation of granulomas (see Figure 2).7,12,13

Infectious agents have long been investigated as possible causative agents in sarcoidosis, with Mycobacterium species most frequently identified.5 Additional possibilities include Propionibacterium acnes (found predominantly in skin lesions) and herpesviruses, although viruses are not known to cause epitheliod granulomas.14

Environmental triggers have also been explored. One large study found a possible association between exposure to insecticides, agricultural environments, and microbial bioaerosols and sarcoidosis.15

The difficulty of pinpointing a single etiology for sarcoidosis—with its varying clinical manifestations, severity, and disease course—suggests that sarcoidosis may be a spectrum of disorders caused by the interaction of genetic, immunologic, infectious, and environmental factors.14

Next page: Diagnosis of sarcoidosis >>

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is based on clinical and radiologic features, histologic evidence of noncaseating granulomas, and exclusion of other possible causes of granulomas.2,12 In addition, when ocular sarcoidosis is suspected, other possible causes of uveitis must be excluded.

In an effort to address these challenges, the International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) developed a standardized approach to diagnosis.9 The group first identified seven intraocular signs of ocular sarcoidosis and then five laboratory or imaging tests that are of value in making the diagnosis in patients with these signs. Last, they established four levels of certainty for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis, based on these signs, tests, and biopsy results, if available (see Table 2).

Treatment

Anterior uveitis in sarcoidosis is usually treated initially with a topical corticosteroid (eg, prednisolone or difluprednate drops), particularly if the patient’s symptoms are mild. In more severe cases (eg, posterior or bilateral uveitis) or when topical corticosteroids are ineffective, systemic (oral) corticosteroids (eg, prednisone) may be initiated. Topical therapy can also be added to an oral regimen as a means of decreasing the oral dosage and thereby reducing the adverse effects of systemic corticosteroids. When the patient’s disease is refractory to corticosteroids or there are concerns about long-term adverse effects, chronic cases may be treated with immunosuppressive agents (eg, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil). Finally, refractory cases of ocular sarcoidosis may be treated with anti–tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) biologic agents such as infliximab and adalimumab.10,17

Continue for case patient outcome >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

Histologic evaluation of tissue from the lacrimal gland, parotid gland, and sinus cavity revealed inflammatory noncaseating granulomas, strongly suggestive of sarcoidosis. Diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis was based on the noncaseating granulomas in the lacrimal gland.9,16 Pulmonary sarcoidosis was also diagnosed, based on the presence of hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.7

The mass in the patient’s lacrimal gland was surgically removed. She was treated with a combination of topical and oral corticosteroids tapered over two weeks, which induced remission of her ocular disease. The patient will be seen annually by an ophthalmologic specialist and was advised to contact her clinician immediately if acute ocular symptoms recurred.10,17

The patient’s persistent cough was determined to be secondary to acute bronchitis, rather than to her pulmonary sarcoidosis, which required no treatment. She received a short course of antibiotics and antitussives for her bronchitis. Systemic corticosteroid treatment of her ocular sarcoidosis also had the benefit of decreasing the size of her pulmonary nodules. She will be followed with annual CT and chest x-rays to monitor the status of her hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and the nodules.3 Periodic pulmonary function testing will also be performed.7

Continue for conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

The elusive nature of the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is well documented in the medical literature. In this case, histologic evaluation of biopsied tissue, correlated with clinical symptoms and radiographic findings, were essential in making the diagnosis.

Primary care providers may be the first to evaluate patients with ocular sarcoidosis and will oversee long-term management. Patients who present with symptoms of eye pain, visual disturbances, abnormal inflammatory ocular features, or swollen lacrimal glands should be referred to an ophthalmologic specialist for further evaluation.

REFERENCES

1. Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1-11.

2. Culver DA. Sarcoidosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2012;32(4):487-511.

3. Spagnolo P, Luppi F, Roversi P, et al. Sarcoidosis: challenging diagnostic aspects of an old disease. Am J Med. 2012;125(2):118-125.

4. Dempsey OJ, Peterson EW, Kerr KM, Denison AR. Sarcoidosis. BMJ. 2009;339:620-625.

5. Brownell I, Ramirez-Valle F, Sanchez M, Prystowsky S. Evidence for mycobacteria in sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45(5):899-905.

6. Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305(4):391-399.

7. Baughman MD, Culver DA, Judson MA. A concise review of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(5):573-581.

8. Koyama T, Ueda H, Togashi K, et al. Radiologic manifestations of sarcoidosis in various organs. Radiographics. 2004;24(1):87-104.

9. Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M; for the Scientific Committee of First International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: results of the first International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS). Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009; 17(3):160-169.

10. Jamilloux Y, Kodjikian L, Broussolle C, Seve P. Sarcoidosis and uveitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(8):840-849.

11. Barisani-Asenbauer T, Maca SM, Mejdoubi L, et al. Uveitis—a rare disease often associated with systemic diseases and infections—a systematic review of 2619 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:57.

12. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. New Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2153-2165.

13. Fontenot A, King T. Pathogenesis of sarcoidosis. www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-of-sarcoidosis?source=search_result&search=Pathogenesis+of+sarcoidosis&selectedTitle=1%7E150. Accessed February 17, 2015.

14. Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, Eckstein C. Etiology of sarcoidosis: does infection play a role? Yale J Biol Med. 2012;85(1):133-141.

15. Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, et al; for the ACCESS Research Group. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis. Environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1324-1330.

16. Kawaguchi T, Hanada A, Horie S, et al. Evaluation of characteristic ocular signs and systemic investigations in ocular sarcoidosis patients. Jpn J Opthalmol. 2007;51(2):121-126.

17. Bodaghi B, Touitou V, Fardeau C, et al. Ocular sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41(6 Pt 2):e349-e354.

FDA approves adhesive treatment for superficial varicose veins

The VenaSeal closure system, which uses an adhesive directly injected into the vein, has been approved as a permanent treatment for symptomatic, superficial varicose veins, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Feb. 20.

“This new system is the first to permanently treat varicose veins by sealing them with an adhesive,” Dr. William Maisel, acting director of the Office of Device Evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the FDA’s statement. Because the system “does not incorporate heat application or cutting, the in-office procedure can allow patients to quickly return to their normal activities, with less bruising,” he added.

The VenaSeal system differs from other procedures used to treat varicose veins, which use drugs, lasers, radiofrequency, or incisions, the FDA statement points out. The complete sterile kit includes the adhesive (n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate), which solidifies when injected directly into the target vein via a catheter, under ultrasound guidance. The additional system components include the catheter, the adhesive, a guidewire, dispenser gun, dispenser tips, and syringes.

Approval was based on data from three clinical trials sponsored by the manufacturer. In the U.S. study that compared results in 108 patients treated with the VenaSeal system and 114 patients treated with radiofrequency ablation therapy, the device was shown “to be safe and effective for vein closure for the treatment of symptomatic superficial varicose veins of the legs,” according to the FDA. In the study, adverse events associated with the VenaSeal treatment included phlebitis and paresthesias in the treated areas, which are “generally associated with treatments of this condition,” the FDA statement noted.

The agency reviewed the VenaSeal System as a class III medical device, considered the highest risk type of medical devices that are subjected to the highest level of regulatory control, and which must be approved before marketing.

VenaSeal is manufactured by Covidien, which acquired Sapheon, the company that developed VenaSeal, in 2014. The system has also been approved in Canada, Europe, and Hong Kong, according to a Covidien statement issued last year.

The VenaSeal closure system, which uses an adhesive directly injected into the vein, has been approved as a permanent treatment for symptomatic, superficial varicose veins, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Feb. 20.

“This new system is the first to permanently treat varicose veins by sealing them with an adhesive,” Dr. William Maisel, acting director of the Office of Device Evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the FDA’s statement. Because the system “does not incorporate heat application or cutting, the in-office procedure can allow patients to quickly return to their normal activities, with less bruising,” he added.

The VenaSeal system differs from other procedures used to treat varicose veins, which use drugs, lasers, radiofrequency, or incisions, the FDA statement points out. The complete sterile kit includes the adhesive (n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate), which solidifies when injected directly into the target vein via a catheter, under ultrasound guidance. The additional system components include the catheter, the adhesive, a guidewire, dispenser gun, dispenser tips, and syringes.

Approval was based on data from three clinical trials sponsored by the manufacturer. In the U.S. study that compared results in 108 patients treated with the VenaSeal system and 114 patients treated with radiofrequency ablation therapy, the device was shown “to be safe and effective for vein closure for the treatment of symptomatic superficial varicose veins of the legs,” according to the FDA. In the study, adverse events associated with the VenaSeal treatment included phlebitis and paresthesias in the treated areas, which are “generally associated with treatments of this condition,” the FDA statement noted.

The agency reviewed the VenaSeal System as a class III medical device, considered the highest risk type of medical devices that are subjected to the highest level of regulatory control, and which must be approved before marketing.

VenaSeal is manufactured by Covidien, which acquired Sapheon, the company that developed VenaSeal, in 2014. The system has also been approved in Canada, Europe, and Hong Kong, according to a Covidien statement issued last year.

The VenaSeal closure system, which uses an adhesive directly injected into the vein, has been approved as a permanent treatment for symptomatic, superficial varicose veins, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Feb. 20.

“This new system is the first to permanently treat varicose veins by sealing them with an adhesive,” Dr. William Maisel, acting director of the Office of Device Evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the FDA’s statement. Because the system “does not incorporate heat application or cutting, the in-office procedure can allow patients to quickly return to their normal activities, with less bruising,” he added.

The VenaSeal system differs from other procedures used to treat varicose veins, which use drugs, lasers, radiofrequency, or incisions, the FDA statement points out. The complete sterile kit includes the adhesive (n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate), which solidifies when injected directly into the target vein via a catheter, under ultrasound guidance. The additional system components include the catheter, the adhesive, a guidewire, dispenser gun, dispenser tips, and syringes.

Approval was based on data from three clinical trials sponsored by the manufacturer. In the U.S. study that compared results in 108 patients treated with the VenaSeal system and 114 patients treated with radiofrequency ablation therapy, the device was shown “to be safe and effective for vein closure for the treatment of symptomatic superficial varicose veins of the legs,” according to the FDA. In the study, adverse events associated with the VenaSeal treatment included phlebitis and paresthesias in the treated areas, which are “generally associated with treatments of this condition,” the FDA statement noted.

The agency reviewed the VenaSeal System as a class III medical device, considered the highest risk type of medical devices that are subjected to the highest level of regulatory control, and which must be approved before marketing.

VenaSeal is manufactured by Covidien, which acquired Sapheon, the company that developed VenaSeal, in 2014. The system has also been approved in Canada, Europe, and Hong Kong, according to a Covidien statement issued last year.

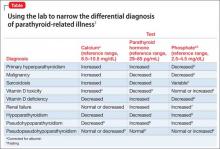

Abnormal calcium level in a psychiatric presentation? Rule out parathyroid disease

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.