User login

Headway being made in developing biomarkers for PTSD

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Researchers are making significant headway in developing objective, reliable, and valid biomarkers to discriminate individuals with warzone post traumatic stress disorder from healthy controls, according to Dr. Charles R. Marmar.

“It’s clear that over the next four or five years we will identify very clear biological, psychological, and other behavioral risk and resilience profiles,” Dr. Marmar told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

Currently, clinicians largely rely on patient self-reports and clinical observations to diagnose PTSD in military personnel, said Dr. Marmar, professor and chair of the department of psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center and director of NYU’s Steven and Alexandra Cohen Veterans Center.

“The problem from the military and law enforcement perspective is that the majority of war fighters experience tremendous stigma in acknowledging their symptoms, particularly active duty military personnel,” he said. “A minority will exaggerate to avoid service or for compensation. Given that we’ve had nearly three million men and women serve in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the fact that we have no objective way yet of determining which ones continue to be fit for redeployment, which ones are in urgent need of help, and which ones deserve compensation, we need to develop better ways to determine if treatments are effective, to inform new treatment selection, and to define new targets for treatment.”

The scope of the problem is underscored in an analysis of data from 289,328 veterans entering VA Healthcare for the first time beginning on April 1, 2002 through March 31, 2006 (Am J. Pub. Health 2009;99[9]:1651-8). Prior to the invasion of Iraq, the distribution of mental health problems was very similar among veterans as in the general population: depression being most common, and low rates of PTSD and alcohol and drug abuse. However, “with each quarter since the invasion of Iraq, there’s been an incubative growth in the prevalence of PTSD, which has now eclipsed depression,” Dr. Marmar said. “We have a toll, a generational effect which looks similar in magnitude with the Vietnam War, both in the number of men and women who serve and in the prevalence of PTSD, depression and alcohol- and drug-related disorders.”

In the general population, risk factors include female sex, child abuse, genetics, which in twin studies account for 30-40% of the risk, lower IQ and lower educational attainment, stressful life events in the prior and following year, and panic reaction at the time of event, such as racing heart, shaking, and sweating.

According to findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study, risk factors for chronic warzone PTSD include high school dropout rate, history of child abuse, high warzone exposure, serious warzone injury, killing combatants, prisoners, and civilians, peritraumatic dissociation, hostile homecoming, post-discharge trauma, and genetics. “These are the risk profiles, and they should give us some clues about where to look for biological factors,” Dr. Marmar said.

The risks of service are not limited to stress, anxiety, depression, alcohol and drug abuse, or traumatic brain injury (TBI). “If you compare men and women returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with no mental health issues to those who have a diagnosis of either PTSD, depression, or the combination, the [diagnosed] cases have 2.5 times the risk of tobacco use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, and type 2 diabetes,” he said. “These are people in their late 20s and early 30s. So the costs of warzone-related stress and depression are enormous on general health.”

Dr. Marmar presented preliminary findings from the ongoing PTSD Systems Biology Consortium, an effort by researchers at seven universities to establish biomarkers for PTSD. Funded by the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health, and other sources, the consortium is comprised of integrated cores including neurocognition, genetics, structural and functional brain imaging, endocrinology, metabolism, genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and bioinformatics.

To date, the researchers have screened 2,215 veterans from service in Iraq and Afghanistan, all of whom have been deployed to war at least once. Cases were PTSD positive and had a CAPS (Clinician-Administered PTSD scale) score of 20 or greater. Controls were PTSD negative and had a CAPS score of less than 20. They excluded subjects with lifetime psychosis, bipolar disorder, or OCD, as well as alcohol dependence in the past eight months, and drug abuse in the past year. They also excluded veterans with TBI “because we’re trying to be very careful to see if we can get a biological signal comparing combat PTSD cases with controls,” Dr. Marmar noted.

Dr. Marmar presented preliminary findings from 52 PTSD cases and 52 controls that were matched for sex, ethnicity, and age. The sample was entirely men, their mean age was 34 years, and they had a mean of 14.8 years of education. The researchers covaried for depression and other known confounders. “It’s very difficult to disentangle the effects of PTSD and depression because 50% of the cases of warzone PTSD also meet criteria for current major depression, and over 80% meet criteria for lifetime depression,” he said.

In results from the clinical diagnostic evaluation, PTSD cases, compared with controls, were significantly more likely to have current anxiety (7% vs. 0%, respectively; P = .041); lifetime anxiety (9.6% vs. 0%; P = .022); current major depressive disorder (51.5% vs. 1.9%; P<.001); lifetime MDD (84.6% vs. 23.1%; P<.001); and lifetime alcohol abuse dependence (63.5% vs. 25%; P = .001). There was also a non-signficant trend toward lifetime substance abuse/dependence (13.5% vs. 3.9%; P = .081).

Results from the neurocognitive assessments revealed that PTSD positive men had a significantly lower estimated IQ, compared with their PTSD negative counterparts (a mean of 99.3 vs. 107.9, respectively; P = .031). Other significant differences between the two groups were observed in tests of auditory and working memory, specifically digit span (8.67 vs. 10.04; P = .02), and the visual memory sum (9.1 vs. 10.67; P = .01).

One of the consortium collaborators developed a test to compare reward and punishment learning. For the test, “the subject is required to understand what the meaning of a symbol is in a task, and they have no prior knowledge [of the meaning],” Dr. Marmar explained. “They’re either rewarded for guessing correctly or punished for guessing incorrectly.” So far, the healthy controls “are performing much better in identifying the symbols when they’re rewarded, compared with the PTSD cases, and there’s no difference in punishment,” he said. “So there’s impaired reward learning and intact punishment learning in PTSD cases compared to controls, which likely reflects underlying disturbances in dopamine reward circuitry.”

Investigators in the neurogenetics core hypothesized that DNA variants in stress-response genes identified from previous medical studies will be associated with PTSD. These included FKBP5, COMT, APOE, BDNF, PACAP/PAC1R, and OPRL1. Initial analysis revealed that there were a greater number of BDNF allele frequencies among cases, compared with controls (P = .008). “It would appear that BDNF variants confer resilience for combat-related PTSD,” Dr. Marmar said.

The researchers also found a single nucleotide polymorphism never previously described on Chromosome 4. “It’s in a region between genes, probably a micro-RNA regulatory gene on the 4th chromosome,” he said. “That gene in our sample was associated with higher levels of PTSD. In addition, fMRI studies found that carrying this allele was associated with weaker activation of prefrontal cortical areas in the brain to empirical faces tasks.”

The endocrine core found that PTSD cases had lower ambient cortisol levels, compared with controls (P = .051). They also had significantly greater cortisol suppression following dexamethasone administration, compared with controls (P = .013). “This is evidence that there is increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity in PTSD expressing as elevated cortisol suppression,” Dr. Marmar said.

Investigators from the structural imaging core found no significant differences in overall hippocampal volume or in the five major hippocampal subfields between PTSD cases and controls, nor in difference in the volume of other brain structures previously implicated in PTSD, such as the amygdala and the thalamus. However, the researchers are finding some differences between cases and controls on functional imaging, including increased spontaneous activity in the amygdala and the insula, and decreased spontaneous activity in the precuneus. “The overall findings on fMRI are that there’s increased activity in the regions [of the brain] associated with fear and decreased connectivity between the frontal cortex and the amygdala,” he said. “This is consistent with the model of dysregulated fear activity in PTSD.”

Researchers have also observed that many markers of metabolic syndrome are significantly elevated between PTSD cases and controls, including fasting glucose (P = .001), weight (P = .03), and resting pulse (P = .003). “When you covary for depression, these findings remain,” Dr. Marmar said. “It’s important to note that these are men mostly in their early 30s recently returned from war and recently in military training, physically fit to be deployed to war.”

He closed his presentation by noting that mounting evidence from animal and human studies suggests evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction in PTSD. In the current analysis, researchers observed a reduced abundance of citrate and other mitochondrial metabolites in PTSD cases compared with controls, as well as an increased abundance of “premitochondrial” metabolites such as pyruvate and lactate. “These findings stand when you covary for depression and for metabolic syndrome,” Dr. Marmar said.

“We believe that these may be very important potential future candidate biomarkers to differentiate PTSD cases from controls.”

The next step in this effort, he added, is to replicate the consortium’s overall findings in a cross-validation sample of 50 male cases and 50 male controls. “We also have a sample of 40 female cases and 40 controls to see if the markers are the same or different,” he said. The researchers are also conducting a prospective study of 1,200 active duty military personnel, who will be evaluated before and after deployment.

For now, some clinicians wonder what should be done for men and women who carry the PTSD risk alleles, or carry the endocrine or metabolism vulnerability to develop complications from combat exposure. “That’s a very sensitive national question,” Dr. Marmar said. “People want to serve their country. The answer may be to allow service but to have a more nuanced approach to what people’s roles should be within the military, to match individuals’ stress resilience with the responsibilities they have.”

Dr. Marmar reported that he had no relevant financial conflicts.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Researchers are making significant headway in developing objective, reliable, and valid biomarkers to discriminate individuals with warzone post traumatic stress disorder from healthy controls, according to Dr. Charles R. Marmar.

“It’s clear that over the next four or five years we will identify very clear biological, psychological, and other behavioral risk and resilience profiles,” Dr. Marmar told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

Currently, clinicians largely rely on patient self-reports and clinical observations to diagnose PTSD in military personnel, said Dr. Marmar, professor and chair of the department of psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center and director of NYU’s Steven and Alexandra Cohen Veterans Center.

“The problem from the military and law enforcement perspective is that the majority of war fighters experience tremendous stigma in acknowledging their symptoms, particularly active duty military personnel,” he said. “A minority will exaggerate to avoid service or for compensation. Given that we’ve had nearly three million men and women serve in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the fact that we have no objective way yet of determining which ones continue to be fit for redeployment, which ones are in urgent need of help, and which ones deserve compensation, we need to develop better ways to determine if treatments are effective, to inform new treatment selection, and to define new targets for treatment.”

The scope of the problem is underscored in an analysis of data from 289,328 veterans entering VA Healthcare for the first time beginning on April 1, 2002 through March 31, 2006 (Am J. Pub. Health 2009;99[9]:1651-8). Prior to the invasion of Iraq, the distribution of mental health problems was very similar among veterans as in the general population: depression being most common, and low rates of PTSD and alcohol and drug abuse. However, “with each quarter since the invasion of Iraq, there’s been an incubative growth in the prevalence of PTSD, which has now eclipsed depression,” Dr. Marmar said. “We have a toll, a generational effect which looks similar in magnitude with the Vietnam War, both in the number of men and women who serve and in the prevalence of PTSD, depression and alcohol- and drug-related disorders.”

In the general population, risk factors include female sex, child abuse, genetics, which in twin studies account for 30-40% of the risk, lower IQ and lower educational attainment, stressful life events in the prior and following year, and panic reaction at the time of event, such as racing heart, shaking, and sweating.

According to findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study, risk factors for chronic warzone PTSD include high school dropout rate, history of child abuse, high warzone exposure, serious warzone injury, killing combatants, prisoners, and civilians, peritraumatic dissociation, hostile homecoming, post-discharge trauma, and genetics. “These are the risk profiles, and they should give us some clues about where to look for biological factors,” Dr. Marmar said.

The risks of service are not limited to stress, anxiety, depression, alcohol and drug abuse, or traumatic brain injury (TBI). “If you compare men and women returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with no mental health issues to those who have a diagnosis of either PTSD, depression, or the combination, the [diagnosed] cases have 2.5 times the risk of tobacco use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, and type 2 diabetes,” he said. “These are people in their late 20s and early 30s. So the costs of warzone-related stress and depression are enormous on general health.”

Dr. Marmar presented preliminary findings from the ongoing PTSD Systems Biology Consortium, an effort by researchers at seven universities to establish biomarkers for PTSD. Funded by the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health, and other sources, the consortium is comprised of integrated cores including neurocognition, genetics, structural and functional brain imaging, endocrinology, metabolism, genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and bioinformatics.

To date, the researchers have screened 2,215 veterans from service in Iraq and Afghanistan, all of whom have been deployed to war at least once. Cases were PTSD positive and had a CAPS (Clinician-Administered PTSD scale) score of 20 or greater. Controls were PTSD negative and had a CAPS score of less than 20. They excluded subjects with lifetime psychosis, bipolar disorder, or OCD, as well as alcohol dependence in the past eight months, and drug abuse in the past year. They also excluded veterans with TBI “because we’re trying to be very careful to see if we can get a biological signal comparing combat PTSD cases with controls,” Dr. Marmar noted.

Dr. Marmar presented preliminary findings from 52 PTSD cases and 52 controls that were matched for sex, ethnicity, and age. The sample was entirely men, their mean age was 34 years, and they had a mean of 14.8 years of education. The researchers covaried for depression and other known confounders. “It’s very difficult to disentangle the effects of PTSD and depression because 50% of the cases of warzone PTSD also meet criteria for current major depression, and over 80% meet criteria for lifetime depression,” he said.

In results from the clinical diagnostic evaluation, PTSD cases, compared with controls, were significantly more likely to have current anxiety (7% vs. 0%, respectively; P = .041); lifetime anxiety (9.6% vs. 0%; P = .022); current major depressive disorder (51.5% vs. 1.9%; P<.001); lifetime MDD (84.6% vs. 23.1%; P<.001); and lifetime alcohol abuse dependence (63.5% vs. 25%; P = .001). There was also a non-signficant trend toward lifetime substance abuse/dependence (13.5% vs. 3.9%; P = .081).

Results from the neurocognitive assessments revealed that PTSD positive men had a significantly lower estimated IQ, compared with their PTSD negative counterparts (a mean of 99.3 vs. 107.9, respectively; P = .031). Other significant differences between the two groups were observed in tests of auditory and working memory, specifically digit span (8.67 vs. 10.04; P = .02), and the visual memory sum (9.1 vs. 10.67; P = .01).

One of the consortium collaborators developed a test to compare reward and punishment learning. For the test, “the subject is required to understand what the meaning of a symbol is in a task, and they have no prior knowledge [of the meaning],” Dr. Marmar explained. “They’re either rewarded for guessing correctly or punished for guessing incorrectly.” So far, the healthy controls “are performing much better in identifying the symbols when they’re rewarded, compared with the PTSD cases, and there’s no difference in punishment,” he said. “So there’s impaired reward learning and intact punishment learning in PTSD cases compared to controls, which likely reflects underlying disturbances in dopamine reward circuitry.”

Investigators in the neurogenetics core hypothesized that DNA variants in stress-response genes identified from previous medical studies will be associated with PTSD. These included FKBP5, COMT, APOE, BDNF, PACAP/PAC1R, and OPRL1. Initial analysis revealed that there were a greater number of BDNF allele frequencies among cases, compared with controls (P = .008). “It would appear that BDNF variants confer resilience for combat-related PTSD,” Dr. Marmar said.

The researchers also found a single nucleotide polymorphism never previously described on Chromosome 4. “It’s in a region between genes, probably a micro-RNA regulatory gene on the 4th chromosome,” he said. “That gene in our sample was associated with higher levels of PTSD. In addition, fMRI studies found that carrying this allele was associated with weaker activation of prefrontal cortical areas in the brain to empirical faces tasks.”

The endocrine core found that PTSD cases had lower ambient cortisol levels, compared with controls (P = .051). They also had significantly greater cortisol suppression following dexamethasone administration, compared with controls (P = .013). “This is evidence that there is increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity in PTSD expressing as elevated cortisol suppression,” Dr. Marmar said.

Investigators from the structural imaging core found no significant differences in overall hippocampal volume or in the five major hippocampal subfields between PTSD cases and controls, nor in difference in the volume of other brain structures previously implicated in PTSD, such as the amygdala and the thalamus. However, the researchers are finding some differences between cases and controls on functional imaging, including increased spontaneous activity in the amygdala and the insula, and decreased spontaneous activity in the precuneus. “The overall findings on fMRI are that there’s increased activity in the regions [of the brain] associated with fear and decreased connectivity between the frontal cortex and the amygdala,” he said. “This is consistent with the model of dysregulated fear activity in PTSD.”

Researchers have also observed that many markers of metabolic syndrome are significantly elevated between PTSD cases and controls, including fasting glucose (P = .001), weight (P = .03), and resting pulse (P = .003). “When you covary for depression, these findings remain,” Dr. Marmar said. “It’s important to note that these are men mostly in their early 30s recently returned from war and recently in military training, physically fit to be deployed to war.”

He closed his presentation by noting that mounting evidence from animal and human studies suggests evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction in PTSD. In the current analysis, researchers observed a reduced abundance of citrate and other mitochondrial metabolites in PTSD cases compared with controls, as well as an increased abundance of “premitochondrial” metabolites such as pyruvate and lactate. “These findings stand when you covary for depression and for metabolic syndrome,” Dr. Marmar said.

“We believe that these may be very important potential future candidate biomarkers to differentiate PTSD cases from controls.”

The next step in this effort, he added, is to replicate the consortium’s overall findings in a cross-validation sample of 50 male cases and 50 male controls. “We also have a sample of 40 female cases and 40 controls to see if the markers are the same or different,” he said. The researchers are also conducting a prospective study of 1,200 active duty military personnel, who will be evaluated before and after deployment.

For now, some clinicians wonder what should be done for men and women who carry the PTSD risk alleles, or carry the endocrine or metabolism vulnerability to develop complications from combat exposure. “That’s a very sensitive national question,” Dr. Marmar said. “People want to serve their country. The answer may be to allow service but to have a more nuanced approach to what people’s roles should be within the military, to match individuals’ stress resilience with the responsibilities they have.”

Dr. Marmar reported that he had no relevant financial conflicts.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Researchers are making significant headway in developing objective, reliable, and valid biomarkers to discriminate individuals with warzone post traumatic stress disorder from healthy controls, according to Dr. Charles R. Marmar.

“It’s clear that over the next four or five years we will identify very clear biological, psychological, and other behavioral risk and resilience profiles,” Dr. Marmar told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

Currently, clinicians largely rely on patient self-reports and clinical observations to diagnose PTSD in military personnel, said Dr. Marmar, professor and chair of the department of psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center and director of NYU’s Steven and Alexandra Cohen Veterans Center.

“The problem from the military and law enforcement perspective is that the majority of war fighters experience tremendous stigma in acknowledging their symptoms, particularly active duty military personnel,” he said. “A minority will exaggerate to avoid service or for compensation. Given that we’ve had nearly three million men and women serve in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the fact that we have no objective way yet of determining which ones continue to be fit for redeployment, which ones are in urgent need of help, and which ones deserve compensation, we need to develop better ways to determine if treatments are effective, to inform new treatment selection, and to define new targets for treatment.”

The scope of the problem is underscored in an analysis of data from 289,328 veterans entering VA Healthcare for the first time beginning on April 1, 2002 through March 31, 2006 (Am J. Pub. Health 2009;99[9]:1651-8). Prior to the invasion of Iraq, the distribution of mental health problems was very similar among veterans as in the general population: depression being most common, and low rates of PTSD and alcohol and drug abuse. However, “with each quarter since the invasion of Iraq, there’s been an incubative growth in the prevalence of PTSD, which has now eclipsed depression,” Dr. Marmar said. “We have a toll, a generational effect which looks similar in magnitude with the Vietnam War, both in the number of men and women who serve and in the prevalence of PTSD, depression and alcohol- and drug-related disorders.”

In the general population, risk factors include female sex, child abuse, genetics, which in twin studies account for 30-40% of the risk, lower IQ and lower educational attainment, stressful life events in the prior and following year, and panic reaction at the time of event, such as racing heart, shaking, and sweating.

According to findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study, risk factors for chronic warzone PTSD include high school dropout rate, history of child abuse, high warzone exposure, serious warzone injury, killing combatants, prisoners, and civilians, peritraumatic dissociation, hostile homecoming, post-discharge trauma, and genetics. “These are the risk profiles, and they should give us some clues about where to look for biological factors,” Dr. Marmar said.

The risks of service are not limited to stress, anxiety, depression, alcohol and drug abuse, or traumatic brain injury (TBI). “If you compare men and women returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with no mental health issues to those who have a diagnosis of either PTSD, depression, or the combination, the [diagnosed] cases have 2.5 times the risk of tobacco use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, and type 2 diabetes,” he said. “These are people in their late 20s and early 30s. So the costs of warzone-related stress and depression are enormous on general health.”

Dr. Marmar presented preliminary findings from the ongoing PTSD Systems Biology Consortium, an effort by researchers at seven universities to establish biomarkers for PTSD. Funded by the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health, and other sources, the consortium is comprised of integrated cores including neurocognition, genetics, structural and functional brain imaging, endocrinology, metabolism, genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and bioinformatics.

To date, the researchers have screened 2,215 veterans from service in Iraq and Afghanistan, all of whom have been deployed to war at least once. Cases were PTSD positive and had a CAPS (Clinician-Administered PTSD scale) score of 20 or greater. Controls were PTSD negative and had a CAPS score of less than 20. They excluded subjects with lifetime psychosis, bipolar disorder, or OCD, as well as alcohol dependence in the past eight months, and drug abuse in the past year. They also excluded veterans with TBI “because we’re trying to be very careful to see if we can get a biological signal comparing combat PTSD cases with controls,” Dr. Marmar noted.

Dr. Marmar presented preliminary findings from 52 PTSD cases and 52 controls that were matched for sex, ethnicity, and age. The sample was entirely men, their mean age was 34 years, and they had a mean of 14.8 years of education. The researchers covaried for depression and other known confounders. “It’s very difficult to disentangle the effects of PTSD and depression because 50% of the cases of warzone PTSD also meet criteria for current major depression, and over 80% meet criteria for lifetime depression,” he said.

In results from the clinical diagnostic evaluation, PTSD cases, compared with controls, were significantly more likely to have current anxiety (7% vs. 0%, respectively; P = .041); lifetime anxiety (9.6% vs. 0%; P = .022); current major depressive disorder (51.5% vs. 1.9%; P<.001); lifetime MDD (84.6% vs. 23.1%; P<.001); and lifetime alcohol abuse dependence (63.5% vs. 25%; P = .001). There was also a non-signficant trend toward lifetime substance abuse/dependence (13.5% vs. 3.9%; P = .081).

Results from the neurocognitive assessments revealed that PTSD positive men had a significantly lower estimated IQ, compared with their PTSD negative counterparts (a mean of 99.3 vs. 107.9, respectively; P = .031). Other significant differences between the two groups were observed in tests of auditory and working memory, specifically digit span (8.67 vs. 10.04; P = .02), and the visual memory sum (9.1 vs. 10.67; P = .01).

One of the consortium collaborators developed a test to compare reward and punishment learning. For the test, “the subject is required to understand what the meaning of a symbol is in a task, and they have no prior knowledge [of the meaning],” Dr. Marmar explained. “They’re either rewarded for guessing correctly or punished for guessing incorrectly.” So far, the healthy controls “are performing much better in identifying the symbols when they’re rewarded, compared with the PTSD cases, and there’s no difference in punishment,” he said. “So there’s impaired reward learning and intact punishment learning in PTSD cases compared to controls, which likely reflects underlying disturbances in dopamine reward circuitry.”

Investigators in the neurogenetics core hypothesized that DNA variants in stress-response genes identified from previous medical studies will be associated with PTSD. These included FKBP5, COMT, APOE, BDNF, PACAP/PAC1R, and OPRL1. Initial analysis revealed that there were a greater number of BDNF allele frequencies among cases, compared with controls (P = .008). “It would appear that BDNF variants confer resilience for combat-related PTSD,” Dr. Marmar said.

The researchers also found a single nucleotide polymorphism never previously described on Chromosome 4. “It’s in a region between genes, probably a micro-RNA regulatory gene on the 4th chromosome,” he said. “That gene in our sample was associated with higher levels of PTSD. In addition, fMRI studies found that carrying this allele was associated with weaker activation of prefrontal cortical areas in the brain to empirical faces tasks.”

The endocrine core found that PTSD cases had lower ambient cortisol levels, compared with controls (P = .051). They also had significantly greater cortisol suppression following dexamethasone administration, compared with controls (P = .013). “This is evidence that there is increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity in PTSD expressing as elevated cortisol suppression,” Dr. Marmar said.

Investigators from the structural imaging core found no significant differences in overall hippocampal volume or in the five major hippocampal subfields between PTSD cases and controls, nor in difference in the volume of other brain structures previously implicated in PTSD, such as the amygdala and the thalamus. However, the researchers are finding some differences between cases and controls on functional imaging, including increased spontaneous activity in the amygdala and the insula, and decreased spontaneous activity in the precuneus. “The overall findings on fMRI are that there’s increased activity in the regions [of the brain] associated with fear and decreased connectivity between the frontal cortex and the amygdala,” he said. “This is consistent with the model of dysregulated fear activity in PTSD.”

Researchers have also observed that many markers of metabolic syndrome are significantly elevated between PTSD cases and controls, including fasting glucose (P = .001), weight (P = .03), and resting pulse (P = .003). “When you covary for depression, these findings remain,” Dr. Marmar said. “It’s important to note that these are men mostly in their early 30s recently returned from war and recently in military training, physically fit to be deployed to war.”

He closed his presentation by noting that mounting evidence from animal and human studies suggests evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction in PTSD. In the current analysis, researchers observed a reduced abundance of citrate and other mitochondrial metabolites in PTSD cases compared with controls, as well as an increased abundance of “premitochondrial” metabolites such as pyruvate and lactate. “These findings stand when you covary for depression and for metabolic syndrome,” Dr. Marmar said.

“We believe that these may be very important potential future candidate biomarkers to differentiate PTSD cases from controls.”

The next step in this effort, he added, is to replicate the consortium’s overall findings in a cross-validation sample of 50 male cases and 50 male controls. “We also have a sample of 40 female cases and 40 controls to see if the markers are the same or different,” he said. The researchers are also conducting a prospective study of 1,200 active duty military personnel, who will be evaluated before and after deployment.

For now, some clinicians wonder what should be done for men and women who carry the PTSD risk alleles, or carry the endocrine or metabolism vulnerability to develop complications from combat exposure. “That’s a very sensitive national question,” Dr. Marmar said. “People want to serve their country. The answer may be to allow service but to have a more nuanced approach to what people’s roles should be within the military, to match individuals’ stress resilience with the responsibilities they have.”

Dr. Marmar reported that he had no relevant financial conflicts.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF PSYCHIATRISTS

Telltale sonographic features of simple and hemorrhagic cysts

Pelvic ultrasonography remains the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts, given its ability to accurately characterize their various aspects:

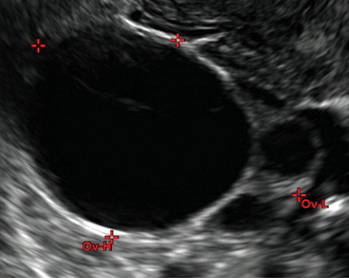

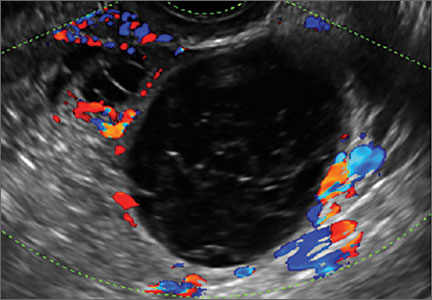

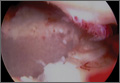

- Simple cysts are uniformly hypoechoic, with thin walls and no blood flow on color Doppler (FIGURE 1).

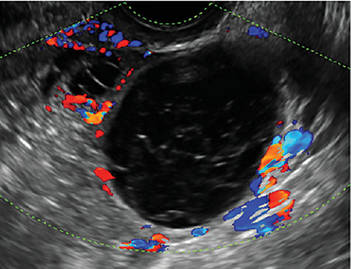

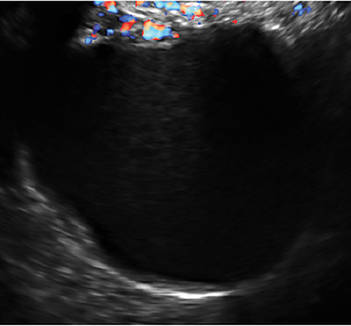

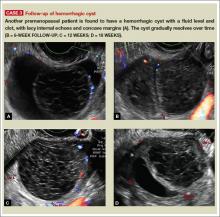

- Hemorrhagic cysts produce lacy/reticular echoes and clot with concave margins

(FIGURE 2). - Mature cystic teratomas produce hyperechoic lines and dots, sometimes known as “dermoid mesh,” acoustic shadowing, and a hyperechoic nodule (FIGURE 3).

- Endometriomas produce diffuse, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance (FIGURE 4).

In the first of this 4-part series on the sonographic features of cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on simple and hemorrhagic cysts. In the following parts we will highlight:

- mature cystic teratomas and endometriomas (Part 2)

- hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts (Part 3)

- cystadenoma and ovarian neoplasia (Part 4).

An earlier installment of this series entitled “Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: one entity with many appearances” (May 2014) also focused on cystic pathology.

Figure 1: Simple cyst

A simple cyst in a 32-year-old patient. Figure 2: Hemorrhagic cyst

Note the lacy/reticular internal echoes and lack of internal blood flow on color Doppler. Figure 3: Cystic teratoma

This cyst exhibits the “dermoid mesh” and hyperechoic lines that correspond with hair. Figure 4: Endometrioma

Note diffuse low-level internal echoes (“ground glass”) and no “ring of fire” on color Doppler. |

Characteristics of simple cysts

A simple cyst typically is round or oval, anechoic, and has smooth, thin walls. It contains no solid component or septation (with rare exceptions), and no internal flow is visible on color Doppler imaging.

Levine and colleagues observed that simple adnexal cysts as large as 10 cm carry a risk of malignancy of less than 1%, regardless of the age of the patient. In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement,1 the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies for women with simple cysts:

Reproductive-aged women

- Cyst <3 cm: No action necessary; the cyst is a normal physiologic finding and should be referred to as a follicle.

- 3–5 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 5–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is highly likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Postmenopausal women

- <1 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 1–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Characteristics of hemorrhagic cysts

These cysts can be quite variable in appearance. Among their sonographic features:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, or fishnet) internal echoes, due to fibrin strands

- solid-appearing areas with concave margins

- on color Doppler, there may be circumferential peripheral flow (“ring of fire”) and no internal flow.

In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies1:

Premenopausal women

- ≤5 cm: No follow-up imaging unless the diagnosis is uncertain.

- >5 cm: Short-interval follow-up ultrasound (6–12 weeks).

Recently menopausal women

- Any size: Follow-up ultrasound in 6–12 weeks to ensure resolution.

Later postmenopausal women

- Any size: Consider surgical removal, as the cyst may be neoplastic.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

Pelvic ultrasonography remains the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts, given its ability to accurately characterize their various aspects:

- Simple cysts are uniformly hypoechoic, with thin walls and no blood flow on color Doppler (FIGURE 1).

- Hemorrhagic cysts produce lacy/reticular echoes and clot with concave margins

(FIGURE 2). - Mature cystic teratomas produce hyperechoic lines and dots, sometimes known as “dermoid mesh,” acoustic shadowing, and a hyperechoic nodule (FIGURE 3).

- Endometriomas produce diffuse, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance (FIGURE 4).

In the first of this 4-part series on the sonographic features of cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on simple and hemorrhagic cysts. In the following parts we will highlight:

- mature cystic teratomas and endometriomas (Part 2)

- hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts (Part 3)

- cystadenoma and ovarian neoplasia (Part 4).

An earlier installment of this series entitled “Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: one entity with many appearances” (May 2014) also focused on cystic pathology.

Figure 1: Simple cyst

A simple cyst in a 32-year-old patient. Figure 2: Hemorrhagic cyst

Note the lacy/reticular internal echoes and lack of internal blood flow on color Doppler. Figure 3: Cystic teratoma

This cyst exhibits the “dermoid mesh” and hyperechoic lines that correspond with hair. Figure 4: Endometrioma

Note diffuse low-level internal echoes (“ground glass”) and no “ring of fire” on color Doppler. |

Characteristics of simple cysts

A simple cyst typically is round or oval, anechoic, and has smooth, thin walls. It contains no solid component or septation (with rare exceptions), and no internal flow is visible on color Doppler imaging.

Levine and colleagues observed that simple adnexal cysts as large as 10 cm carry a risk of malignancy of less than 1%, regardless of the age of the patient. In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement,1 the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies for women with simple cysts:

Reproductive-aged women

- Cyst <3 cm: No action necessary; the cyst is a normal physiologic finding and should be referred to as a follicle.

- 3–5 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 5–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is highly likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Postmenopausal women

- <1 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 1–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Characteristics of hemorrhagic cysts

These cysts can be quite variable in appearance. Among their sonographic features:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, or fishnet) internal echoes, due to fibrin strands

- solid-appearing areas with concave margins

- on color Doppler, there may be circumferential peripheral flow (“ring of fire”) and no internal flow.

In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies1:

Premenopausal women

- ≤5 cm: No follow-up imaging unless the diagnosis is uncertain.

- >5 cm: Short-interval follow-up ultrasound (6–12 weeks).

Recently menopausal women

- Any size: Follow-up ultrasound in 6–12 weeks to ensure resolution.

Later postmenopausal women

- Any size: Consider surgical removal, as the cyst may be neoplastic.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Pelvic ultrasonography remains the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts, given its ability to accurately characterize their various aspects:

- Simple cysts are uniformly hypoechoic, with thin walls and no blood flow on color Doppler (FIGURE 1).

- Hemorrhagic cysts produce lacy/reticular echoes and clot with concave margins

(FIGURE 2). - Mature cystic teratomas produce hyperechoic lines and dots, sometimes known as “dermoid mesh,” acoustic shadowing, and a hyperechoic nodule (FIGURE 3).

- Endometriomas produce diffuse, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance (FIGURE 4).

In the first of this 4-part series on the sonographic features of cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on simple and hemorrhagic cysts. In the following parts we will highlight:

- mature cystic teratomas and endometriomas (Part 2)

- hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts (Part 3)

- cystadenoma and ovarian neoplasia (Part 4).

An earlier installment of this series entitled “Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: one entity with many appearances” (May 2014) also focused on cystic pathology.

Figure 1: Simple cyst

A simple cyst in a 32-year-old patient. Figure 2: Hemorrhagic cyst

Note the lacy/reticular internal echoes and lack of internal blood flow on color Doppler. Figure 3: Cystic teratoma

This cyst exhibits the “dermoid mesh” and hyperechoic lines that correspond with hair. Figure 4: Endometrioma

Note diffuse low-level internal echoes (“ground glass”) and no “ring of fire” on color Doppler. |

Characteristics of simple cysts

A simple cyst typically is round or oval, anechoic, and has smooth, thin walls. It contains no solid component or septation (with rare exceptions), and no internal flow is visible on color Doppler imaging.

Levine and colleagues observed that simple adnexal cysts as large as 10 cm carry a risk of malignancy of less than 1%, regardless of the age of the patient. In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement,1 the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies for women with simple cysts:

Reproductive-aged women

- Cyst <3 cm: No action necessary; the cyst is a normal physiologic finding and should be referred to as a follicle.

- 3–5 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 5–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is highly likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Postmenopausal women

- <1 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 1–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Characteristics of hemorrhagic cysts

These cysts can be quite variable in appearance. Among their sonographic features:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, or fishnet) internal echoes, due to fibrin strands

- solid-appearing areas with concave margins

- on color Doppler, there may be circumferential peripheral flow (“ring of fire”) and no internal flow.

In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies1:

Premenopausal women

- ≤5 cm: No follow-up imaging unless the diagnosis is uncertain.

- >5 cm: Short-interval follow-up ultrasound (6–12 weeks).

Recently menopausal women

- Any size: Follow-up ultrasound in 6–12 weeks to ensure resolution.

Later postmenopausal women

- Any size: Consider surgical removal, as the cyst may be neoplastic.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

Reference

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

Product Update: InTone, E-Sacs, traxi, Saliva Fertility Monitor

FEMALE URINARY INCONTINENCE DEVICE

The InTone® system from InControl Medical™ is a noninvasive home-based pelvic-floor rehabilitation program to treat female urinary incontinence. InControl offers two customizable probes. Apex, for women with mild to moderate stress urinary incontinence, delivers electro-stimulation to strengthen pelvic floor muscles and eliminate leakage associated with coughing, laughing, or exercise. ApexM, for women with urgency and mixed urinary incontinence, provides alternating-frequency stimulation to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles and calm detrusor muscle spasms.

The InTone system for moderate to severe incontinence combines muscle stimulation with pelvic-floor exercises. A hand-held control unit allows the patient to listen to prerecorded exercises at home. The control unit also offers visual biofeedback to ensure that the exercises are being completed properly. The patient can present the data from her workouts, stored by the handheld control unit, to her physician, who can then individualize the exercise plan. InTone is indicated for use in 12-minute sessions, six times a week, for 90 days to treat stress urinary incontinence, and for 180 days for urgency or mixed incontinence.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.incontrolmedical.com

TISSUE RETRIEVAL SACS

Espiner Medical offers E-Sacs, a variety of tissue retrieval sacs for minimally invasive surgery. E-Sacs are manufactured from Superamine66™ fabric, a lightweight, ripstop nylon coated with polyurethane designed to make them strong, rupture proof, leak resistant, easy to deploy, and x-ray opaque. Standard E-Sacs, made of one-piece construction with an integral tail that can be deployed using 5-mm instruments, do not require claw forceps to extract. Super E-Sacs are ideal for larger specimens and have colored tabs to facilitate placement. Master E-Sacs open automatically, have stronger arms to reinforce the mouth opening, a drawstring closure, and can accept tissue sizes up to a large spleen, ovary, or kidney. EcoSacs, for bottom-first abdominal entry, have a large open mouth to facilitate tissue capture with a drawstring closure.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.espinermedical.com

PANNICULUS RETRACTOR

traxi can be applied and used as a sterile or nonsterile product in conjunction with both external and internal retractors. The manufacturer explains that traxi works by anchoring at the xiphoid and distributing the patient’s weight rather than applying it fully on the sternum, which can make it difficult for the patient to breathe. traxi should not be left on the patient for longer than 24 hours. traxi is labeled with HOLD and PULL HERE tabs, as well as A, B, and C tabs to guide the clinician through the retractor application process.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.clinicalinnovations.com

SALIVA FERTILITY MONITOR

The KNOWHEN® Saliva Fertility Monitor is a handheld mini-microscope that monitors a woman’s ovulation using just a single drop of saliva. A woman’s daily test results can be tracked on an ovulation mobile app provided with the product, allowing her to better plan her sexual activity to achieve fertility goals.

First thing each morning, before eating, drinking, smoking, or brushing teeth, a woman applies a thick drop of saliva to the glass surface and waits for it to dry (5–15 minutes). Then she compares the image she sees through the lens to the chart supplied with the kit and inputs her results on the KNOWHEN app. If she is not ovulating, dots and circles may appear. When she sees a few fernlike crystals, it means she is starting to ovulate, or has just finished ovulating. Consistent fern-like crystals in the viewer indicate that she is ovulating. During ovulation, high estrogen levels raise the percentage of salt in a woman’s body. In saliva, these salts take the shape of ferns under the 60X magnification of the KNOWHEN microscope. The kit includes the app and educational material, including an instructional video.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.knowhen.com

FEMALE URINARY INCONTINENCE DEVICE

The InTone® system from InControl Medical™ is a noninvasive home-based pelvic-floor rehabilitation program to treat female urinary incontinence. InControl offers two customizable probes. Apex, for women with mild to moderate stress urinary incontinence, delivers electro-stimulation to strengthen pelvic floor muscles and eliminate leakage associated with coughing, laughing, or exercise. ApexM, for women with urgency and mixed urinary incontinence, provides alternating-frequency stimulation to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles and calm detrusor muscle spasms.

The InTone system for moderate to severe incontinence combines muscle stimulation with pelvic-floor exercises. A hand-held control unit allows the patient to listen to prerecorded exercises at home. The control unit also offers visual biofeedback to ensure that the exercises are being completed properly. The patient can present the data from her workouts, stored by the handheld control unit, to her physician, who can then individualize the exercise plan. InTone is indicated for use in 12-minute sessions, six times a week, for 90 days to treat stress urinary incontinence, and for 180 days for urgency or mixed incontinence.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.incontrolmedical.com

TISSUE RETRIEVAL SACS

Espiner Medical offers E-Sacs, a variety of tissue retrieval sacs for minimally invasive surgery. E-Sacs are manufactured from Superamine66™ fabric, a lightweight, ripstop nylon coated with polyurethane designed to make them strong, rupture proof, leak resistant, easy to deploy, and x-ray opaque. Standard E-Sacs, made of one-piece construction with an integral tail that can be deployed using 5-mm instruments, do not require claw forceps to extract. Super E-Sacs are ideal for larger specimens and have colored tabs to facilitate placement. Master E-Sacs open automatically, have stronger arms to reinforce the mouth opening, a drawstring closure, and can accept tissue sizes up to a large spleen, ovary, or kidney. EcoSacs, for bottom-first abdominal entry, have a large open mouth to facilitate tissue capture with a drawstring closure.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.espinermedical.com

PANNICULUS RETRACTOR

traxi can be applied and used as a sterile or nonsterile product in conjunction with both external and internal retractors. The manufacturer explains that traxi works by anchoring at the xiphoid and distributing the patient’s weight rather than applying it fully on the sternum, which can make it difficult for the patient to breathe. traxi should not be left on the patient for longer than 24 hours. traxi is labeled with HOLD and PULL HERE tabs, as well as A, B, and C tabs to guide the clinician through the retractor application process.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.clinicalinnovations.com

SALIVA FERTILITY MONITOR

The KNOWHEN® Saliva Fertility Monitor is a handheld mini-microscope that monitors a woman’s ovulation using just a single drop of saliva. A woman’s daily test results can be tracked on an ovulation mobile app provided with the product, allowing her to better plan her sexual activity to achieve fertility goals.

First thing each morning, before eating, drinking, smoking, or brushing teeth, a woman applies a thick drop of saliva to the glass surface and waits for it to dry (5–15 minutes). Then she compares the image she sees through the lens to the chart supplied with the kit and inputs her results on the KNOWHEN app. If she is not ovulating, dots and circles may appear. When she sees a few fernlike crystals, it means she is starting to ovulate, or has just finished ovulating. Consistent fern-like crystals in the viewer indicate that she is ovulating. During ovulation, high estrogen levels raise the percentage of salt in a woman’s body. In saliva, these salts take the shape of ferns under the 60X magnification of the KNOWHEN microscope. The kit includes the app and educational material, including an instructional video.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.knowhen.com

FEMALE URINARY INCONTINENCE DEVICE

The InTone® system from InControl Medical™ is a noninvasive home-based pelvic-floor rehabilitation program to treat female urinary incontinence. InControl offers two customizable probes. Apex, for women with mild to moderate stress urinary incontinence, delivers electro-stimulation to strengthen pelvic floor muscles and eliminate leakage associated with coughing, laughing, or exercise. ApexM, for women with urgency and mixed urinary incontinence, provides alternating-frequency stimulation to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles and calm detrusor muscle spasms.

The InTone system for moderate to severe incontinence combines muscle stimulation with pelvic-floor exercises. A hand-held control unit allows the patient to listen to prerecorded exercises at home. The control unit also offers visual biofeedback to ensure that the exercises are being completed properly. The patient can present the data from her workouts, stored by the handheld control unit, to her physician, who can then individualize the exercise plan. InTone is indicated for use in 12-minute sessions, six times a week, for 90 days to treat stress urinary incontinence, and for 180 days for urgency or mixed incontinence.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.incontrolmedical.com

TISSUE RETRIEVAL SACS

Espiner Medical offers E-Sacs, a variety of tissue retrieval sacs for minimally invasive surgery. E-Sacs are manufactured from Superamine66™ fabric, a lightweight, ripstop nylon coated with polyurethane designed to make them strong, rupture proof, leak resistant, easy to deploy, and x-ray opaque. Standard E-Sacs, made of one-piece construction with an integral tail that can be deployed using 5-mm instruments, do not require claw forceps to extract. Super E-Sacs are ideal for larger specimens and have colored tabs to facilitate placement. Master E-Sacs open automatically, have stronger arms to reinforce the mouth opening, a drawstring closure, and can accept tissue sizes up to a large spleen, ovary, or kidney. EcoSacs, for bottom-first abdominal entry, have a large open mouth to facilitate tissue capture with a drawstring closure.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.espinermedical.com

PANNICULUS RETRACTOR

traxi can be applied and used as a sterile or nonsterile product in conjunction with both external and internal retractors. The manufacturer explains that traxi works by anchoring at the xiphoid and distributing the patient’s weight rather than applying it fully on the sternum, which can make it difficult for the patient to breathe. traxi should not be left on the patient for longer than 24 hours. traxi is labeled with HOLD and PULL HERE tabs, as well as A, B, and C tabs to guide the clinician through the retractor application process.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.clinicalinnovations.com

SALIVA FERTILITY MONITOR

The KNOWHEN® Saliva Fertility Monitor is a handheld mini-microscope that monitors a woman’s ovulation using just a single drop of saliva. A woman’s daily test results can be tracked on an ovulation mobile app provided with the product, allowing her to better plan her sexual activity to achieve fertility goals.

First thing each morning, before eating, drinking, smoking, or brushing teeth, a woman applies a thick drop of saliva to the glass surface and waits for it to dry (5–15 minutes). Then she compares the image she sees through the lens to the chart supplied with the kit and inputs her results on the KNOWHEN app. If she is not ovulating, dots and circles may appear. When she sees a few fernlike crystals, it means she is starting to ovulate, or has just finished ovulating. Consistent fern-like crystals in the viewer indicate that she is ovulating. During ovulation, high estrogen levels raise the percentage of salt in a woman’s body. In saliva, these salts take the shape of ferns under the 60X magnification of the KNOWHEN microscope. The kit includes the app and educational material, including an instructional video.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.knowhen.com

David Henry's JCSO podcast, February 2015

The line-up for David Henry’s monthly podcast for The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology includes an Original Report in which investigators report complete response rates (no emesis, no rescue medication) APF530, a sustained-release granisetron, during the acute and delayed phases of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting over multiple cycles of the therapy. He also discusses the findings from a study on joint breast and colorectal cancer screenings in medically underserved women, and another in women with self-reported lower limb lymphedema after treatment for gynecological cancers and their use of services. A fourth Original Report examines perceptions about participation in cancer clinical trials in New York state and how increased outreach and a team approach to educating and enrolling patients in trials are important to increase participation and ensure a diverse sample of participants. Finally, a feature article on new therapies looks at the significant challenges – and recent advances – in the treatment of head and neck cancers.

The line-up for David Henry’s monthly podcast for The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology includes an Original Report in which investigators report complete response rates (no emesis, no rescue medication) APF530, a sustained-release granisetron, during the acute and delayed phases of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting over multiple cycles of the therapy. He also discusses the findings from a study on joint breast and colorectal cancer screenings in medically underserved women, and another in women with self-reported lower limb lymphedema after treatment for gynecological cancers and their use of services. A fourth Original Report examines perceptions about participation in cancer clinical trials in New York state and how increased outreach and a team approach to educating and enrolling patients in trials are important to increase participation and ensure a diverse sample of participants. Finally, a feature article on new therapies looks at the significant challenges – and recent advances – in the treatment of head and neck cancers.

The line-up for David Henry’s monthly podcast for The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology includes an Original Report in which investigators report complete response rates (no emesis, no rescue medication) APF530, a sustained-release granisetron, during the acute and delayed phases of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting over multiple cycles of the therapy. He also discusses the findings from a study on joint breast and colorectal cancer screenings in medically underserved women, and another in women with self-reported lower limb lymphedema after treatment for gynecological cancers and their use of services. A fourth Original Report examines perceptions about participation in cancer clinical trials in New York state and how increased outreach and a team approach to educating and enrolling patients in trials are important to increase participation and ensure a diverse sample of participants. Finally, a feature article on new therapies looks at the significant challenges – and recent advances – in the treatment of head and neck cancers.

Factor Xa antidote gets orphan designation

Photo by Piotr Bodzek

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to andexanet alfa for reversing the anticoagulant effect of factor Xa inhibitors in patients experiencing a serious, uncontrolled bleeding event and those who require urgent or emergent surgery.

At present, there is no approved antidote for these patients.

Andexanet alfa is the only compound being studied as a reversal agent for factor Xa inhibitors that directly and specifically corrects anti-factor Xa activity.

The drug is a modified human factor Xa molecule that acts as a decoy to target and sequester both oral and injectable factor Xa inhibitors in the blood. Once bound, the inhibitors are unable to bind to and inhibit native factor Xa, thus allowing for the restoration of normal hemostatic processes.

Andexanet alfa has the potential to address several clinical scenarios where a factor Xa antidote is needed by allowing for flexible and controlled reversal. This can be short-acting, through the administration of an intravenous (IV) bolus, or longer-acting with the addition of an extended infusion.

The FDA previously granted andexanet alfa breakthrough therapy designation, which is intended to expedite the development and review of a drug candidate intended to treat a serious or life-threatening condition.

“Orphan drug designation for andexanet alfa recognizes its potential to address a significant unmet medical need and to advance the field by helping patients who currently have no treatment options,” said Bill Lis, chief executive officer of Portola Pharmaceuticals, the company developing andexanet alfa.

The FDA’s orphan drug designation program provides orphan status to drugs and biologics that are intended for the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of rare diseases/disorders that currently affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation qualifies a company for certain benefits, including an accelerated approval process, 7 years of market exclusivity following the drug’s approval, tax credits on US clinical trials, eligibility for orphan drug grants, and a waiver of certain administrative fees.

Clinical development of andexanet alfa

Researchers are currently evaluating andexanet alfa in 2 randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials—ANNEXA-A and ANNEXA-R.

They previously reported promising results from the first part of the ANNEXA-A study, a test of andexanet alfa’s ability to reverse the effects of apixaban in healthy subjects when the antidote was given as a single IV bolus.

Researchers also reported favorable results from the first part of the ANNEXA-R study, in which they evaluated andexanet alfa’s ability to reverse the effects of rivaroxaban in healthy subjects when the antidote was given as a single IV bolus.

The second parts of the ANNEXA-A and ANNEXA-R studies are ongoing. The researchers are evaluating the use of andexanet alfa given as a bolus and a continuous infusion.

ANNEXA-4, a phase 4, single-arm, confirmatory study is also ongoing. Researchers are evaluating the drug in patients receiving apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, or enoxaparin who present with an acute major bleed. ![]()

Photo by Piotr Bodzek

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to andexanet alfa for reversing the anticoagulant effect of factor Xa inhibitors in patients experiencing a serious, uncontrolled bleeding event and those who require urgent or emergent surgery.

At present, there is no approved antidote for these patients.

Andexanet alfa is the only compound being studied as a reversal agent for factor Xa inhibitors that directly and specifically corrects anti-factor Xa activity.

The drug is a modified human factor Xa molecule that acts as a decoy to target and sequester both oral and injectable factor Xa inhibitors in the blood. Once bound, the inhibitors are unable to bind to and inhibit native factor Xa, thus allowing for the restoration of normal hemostatic processes.

Andexanet alfa has the potential to address several clinical scenarios where a factor Xa antidote is needed by allowing for flexible and controlled reversal. This can be short-acting, through the administration of an intravenous (IV) bolus, or longer-acting with the addition of an extended infusion.

The FDA previously granted andexanet alfa breakthrough therapy designation, which is intended to expedite the development and review of a drug candidate intended to treat a serious or life-threatening condition.

“Orphan drug designation for andexanet alfa recognizes its potential to address a significant unmet medical need and to advance the field by helping patients who currently have no treatment options,” said Bill Lis, chief executive officer of Portola Pharmaceuticals, the company developing andexanet alfa.

The FDA’s orphan drug designation program provides orphan status to drugs and biologics that are intended for the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of rare diseases/disorders that currently affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation qualifies a company for certain benefits, including an accelerated approval process, 7 years of market exclusivity following the drug’s approval, tax credits on US clinical trials, eligibility for orphan drug grants, and a waiver of certain administrative fees.

Clinical development of andexanet alfa

Researchers are currently evaluating andexanet alfa in 2 randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials—ANNEXA-A and ANNEXA-R.

They previously reported promising results from the first part of the ANNEXA-A study, a test of andexanet alfa’s ability to reverse the effects of apixaban in healthy subjects when the antidote was given as a single IV bolus.

Researchers also reported favorable results from the first part of the ANNEXA-R study, in which they evaluated andexanet alfa’s ability to reverse the effects of rivaroxaban in healthy subjects when the antidote was given as a single IV bolus.

The second parts of the ANNEXA-A and ANNEXA-R studies are ongoing. The researchers are evaluating the use of andexanet alfa given as a bolus and a continuous infusion.

ANNEXA-4, a phase 4, single-arm, confirmatory study is also ongoing. Researchers are evaluating the drug in patients receiving apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, or enoxaparin who present with an acute major bleed. ![]()

Photo by Piotr Bodzek

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to andexanet alfa for reversing the anticoagulant effect of factor Xa inhibitors in patients experiencing a serious, uncontrolled bleeding event and those who require urgent or emergent surgery.

At present, there is no approved antidote for these patients.

Andexanet alfa is the only compound being studied as a reversal agent for factor Xa inhibitors that directly and specifically corrects anti-factor Xa activity.

The drug is a modified human factor Xa molecule that acts as a decoy to target and sequester both oral and injectable factor Xa inhibitors in the blood. Once bound, the inhibitors are unable to bind to and inhibit native factor Xa, thus allowing for the restoration of normal hemostatic processes.

Andexanet alfa has the potential to address several clinical scenarios where a factor Xa antidote is needed by allowing for flexible and controlled reversal. This can be short-acting, through the administration of an intravenous (IV) bolus, or longer-acting with the addition of an extended infusion.

The FDA previously granted andexanet alfa breakthrough therapy designation, which is intended to expedite the development and review of a drug candidate intended to treat a serious or life-threatening condition.

“Orphan drug designation for andexanet alfa recognizes its potential to address a significant unmet medical need and to advance the field by helping patients who currently have no treatment options,” said Bill Lis, chief executive officer of Portola Pharmaceuticals, the company developing andexanet alfa.

The FDA’s orphan drug designation program provides orphan status to drugs and biologics that are intended for the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of rare diseases/disorders that currently affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation qualifies a company for certain benefits, including an accelerated approval process, 7 years of market exclusivity following the drug’s approval, tax credits on US clinical trials, eligibility for orphan drug grants, and a waiver of certain administrative fees.

Clinical development of andexanet alfa

Researchers are currently evaluating andexanet alfa in 2 randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials—ANNEXA-A and ANNEXA-R.

They previously reported promising results from the first part of the ANNEXA-A study, a test of andexanet alfa’s ability to reverse the effects of apixaban in healthy subjects when the antidote was given as a single IV bolus.

Researchers also reported favorable results from the first part of the ANNEXA-R study, in which they evaluated andexanet alfa’s ability to reverse the effects of rivaroxaban in healthy subjects when the antidote was given as a single IV bolus.

The second parts of the ANNEXA-A and ANNEXA-R studies are ongoing. The researchers are evaluating the use of andexanet alfa given as a bolus and a continuous infusion.

ANNEXA-4, a phase 4, single-arm, confirmatory study is also ongoing. Researchers are evaluating the drug in patients receiving apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, or enoxaparin who present with an acute major bleed. ![]()

Nanotechnology: Why Should We Care?

The orthopedic community is increasingly deluged with advancements in the basic sciences. With each step, we must evaluate the necessity of new information and the relevance of these topics for clinical practice. Since the late 1990s, the promise of nanotechnology to effect significant changes in the medical field has been heralded. However, in this coming decade, we as a profession will see unprecedented advances in the movement of this technology “from the bench to the bedside.” Not unlike many other basic science advancements in our field, nanotechnology is poorly understood among clinicians and residents. As the use of biologics and drug delivery systems expands in orthopedics, nanoparticle-based devices will become more prevalent and have a momentous impact on the way we treat and diagnose orthopedic patients.

A nanoparticle is generally defined as a particle in which at least 1 dimension is between 1 to 100 nanometers and has material properties consistent with quantum mechanics.1 Nanomaterials can be composed of organic and inorganic chemical elements that enable basic chemical processes to create more complex systems. Individual nanoparticle units can be synthesized to form nanostructures, including nanotubes, nanoscaffolds, nanofibers, and even nanodiamonds.2-4 Nanoparticles at this scale display unique optical, chemical, and physical properties that can be manipulated to create specific end-use applications. Such uses may include glass fabrication, optical probes, television screens, drug delivery, gene delivery, and multiplex diagnostic assays.5-7 By crossing disciplines of physics, engineering, and medical sciences, we can create novel technology that includes nanomanufacturing, targeted drug delivery, nanorobotics in conjunction with artificial intelligence, and point-of-care diagnostics.7-9

The field of orthopedics has benefited from nanotechnologic advances, such as new therapeutics and implant-related technology. Nanotubes are hollow nanosized cylinders that are commonly created from titania, silica, or carbon-based substrates. They have garnered significant interest for their high tensile and shear strength, favorable microstructure for bony ingrowth, and their capacity to hold antibiotics or growth factors, such as bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs).10 The current local delivery limitations of BMPs via a collagen sponge have the potential to be maximized and better controlled with a nanotechnology-based approach. The size, internal structure, and shape of the nanoparticle can be manipulated to control the release of these growth factors, and certain nanoparticles can be dual-layered, allowing for release of multiple growth factors at once or in succession.11,12 A more powerful and targeted delivery system of these types of growth factors may result in improved or more robust outcomes, and further research is warranted.

It is possible that carbon-based nanotubes can be categorized as a biomedical implant secondary to their mechanical properties.13 Their strength and ability to be augmented with osteogenic materials has made them an attractive area of research as alternative implant surfaces and stand-alone implants. Nanotubes are capable of acting as a scaffold for antibiotic-loaded, carbon-based nanodiamonds for localized treatment of periprosthetic infection, and research has been directed toward controlled release of the nanodiamond-antibiotic construct from these scaffolds or hydrogels.4,14 Technologies like this may allow the clinician to treat periprosthetic infections locally and minimize the use of systemic antibiotics. The perfection of this type of delivery system may augment the role of antibiotic-laden cement and improve our treatment success rates, even in traditionally hard-to-treat organisms.

Nanoscaffolds and nanofibers are created from nanosized polymers and rendered into a 3-dimensional structure that can be loaded with biologic particles or acting as a scaffold/template for tissue or bone ingrowth. Nanofibers created using biodegradable substrates such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and chitosan have been extensively studied for their delayed-release properties and biocompatibility.15 These scaffolds are often soaked or loaded with chondrogenic, osteogenic, or antibacterial agents, and have been evaluated in both in vitro and in vivo studies with promising results.15,16 They have been an exciting area of research in tissue engineering, and have been accepted as an adjunct in tendon-repair treatments and local bone regeneration.3,17 As this technology is perfected, the potential to treat more effectively massive rotator cuff tears or tears with poor tissue integrity will dramatically improve and expand the indications for rotator cuff repair.

Augmentation of implant surfaces with nanomaterials that improve osseointegration, or that act as antimicrobial agents have also been a focus of research in hopes of decreasing the rates of aseptic failure and periprosthetic infection in arthroplasty procedures. Nanocrystalline surfaces made of hydroxyapatite and cobalt chromium have been evaluated for their enhanced osteoconductive properties, and may replace standard surfaces.18-20 Recent work evaluating nanoparticle-antibiotic constructs that have been covalently bound to implant surfaces for delayed release of antibiotics during the perioperative period has shown promise, and may allow a more targeted and localized treatment strategy for periprosthetic infection.21,22

Major limitations regarding successful clinical implementation of nanotechnology include both cost and regulatory processes. Currently, pharmaceutical companies estimate that, on average, successful clinical trials from phase 1 to completion for new drugs can cost hundreds of millions of dollars.23 Such high costs result partially from the laborious and capital-intensive process of conducting clinical trials that meet US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirements. These regulations would apply to both surface-coated implants and nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems. These types of implants would not be expedited into the market secondary to their drug delivery component and would likely require lengthy clinical studies. Implant companies may be reluctant to invest millions of dollars in multiple FDA trials when they have lucrative implants on the market.

Other limitations include the particles’ complex 3-dimensional structure, which can present challenges for mass production. Producing large quantities of nanoparticles at a consistent quality may be a major limitation to the more unique and target-based nanotherapies. Recent concerns with the toxicity profile of nanotechnology-based medicines have resulted in more intense scrutiny of the nanotechnology safety profile.24,25 Currently, nanoparticle technology is evaluated case by case with each technology requiring its own toxicology and safety profile testing if it is intended for human use. These tests can be cost-prohibitive and require extensive private and government capital for successful market entry. Despite these limitations, nanotechnology will impact the next generation of orthopedic surgeons. Current estimates project the nanomedicine market to be worth $177.6 billion by 2019.26

Advances in nanobased orthopedic technologies have expanded dramatically in the past decade, and we, as the treating physicians, must make educated decisions on how and when to use nanoparticle-based therapies and treatment options. Nanotechnology’s basic science is confusing and often burdensome, but contemporary review articles may be helpful in keeping the orthopedic resident and clinician current with advancements.10,27,28 The more we educate ourselves about evolving nanotechnologies, the less reluctance we will have when evaluating new diagnostic and therapeutic treatment modalities.

1. Hewakuruppu YL, Dombrovsky LA, Chen C, et al. Plasmonic “pump-probe” method to study semi-transparent nanofluids. Appl Opt. 2013;52(24):6041-6050.