User login

CASE Seizures, amnesia

Ms. A, age 13, who has a history of seizures, presents to the emergency department (ED) with sudden onset of memory loss. Her family reports that she had been spending a normal evening at home with family and friends. After going to the bathroom, Ms. A became acutely confused and extremely upset, had slurred speech, and did not recognize anyone in the room except her mother.

Initial neurologic examination in the ED reports that Ms. A does not remember recent or remote past events. Her family denies any recent stressors.

Vital signs are within normal range. She has mild muscle soreness and gait instability, which is attributed to a presumed postictal phase. Her medication regimen includes: levetiracetam, 500 mg, 3 times a day; valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d; and oxcarbazepine, 2,400 mg/d, for seizure management.

Complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel are within normal limits. Pregnancy test is negative. Urine toxicology report is negative. Serum valproic acid level is 71 μg/mL; oxcarbazepine level, <2 μg/mL; ammonia level, 71 μg/dL (reference range, 15 to 45 μg/dL). Other than the aforementioned deficits, she is neurologically intact. The team thinks that her symptoms are part of a postictal phase of an unwitnessed seizure.

Ms. A is admitted to the inpatient medical unit for further work up. Along with the memory loss and seizures, she reports visual hallucinations.

What could be causing Ms. A’s amnesia?

a) a seizure disorder

b) malingering

c) posttraumatic stress disorder

d) traumatic brain injury

HISTORY Repeat ED visits

Ms. A’s mother reports that 3 years ago her daughter was treated for tics with quetiapine and aripiprazole, prescribed by a primary care physician. She received a short course of counseling 6 years ago after her sister was sexually abused by her grandfather. Approximately 6 months ago, Ms. A engaged in self-injurious behavior by cutting herself, and she briefly received counseling. There is no history of suicide attempts, psychiatric hospitalization, or a psychiatric diagnosis.

Medical and surgical history include viral meningitis at age 6 months. Medical records show a visit to the ED for abdominal pain after a classmate punched her in the abdomen, which resolved with supportive care. She was given a diagnosis of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections 6 years ago.

Ms. A developed multiple recurrent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus abscesses a year ago, which lasted for 4 months; it was noted that she was self-inoculating by scratching eczema. She had a possible syncopal episode 5 months ago, but the medical work-up was normal. The pediatric neurology service diagnosed and treated seizures 4 months ago.

Levetiracetam was prescribed after a possible syncopal episode followed by a tonic-clonic seizure. Because she was still having seizure-like episodes with a single antiepileptic drug (AED), oxcarbazepine, then valproic acid were added. Whether her seizures were generalized or partial was inconclusive. The seizures were followed by a postictal phase lasting 3 minutes to 1 hour. Her last generalized tonic-clonic seizure was 1 month before admission.

Ms. A had 3 MRI studies of the brain over the past 3 years, which showed consistent and unchanged multifocal punctate white matter lesions. The findings represented gliosis from an old perivascular inflammation, trauma, or ischemic damage. There is no history of traumatic brain injury.

Her perinatal history is unremarkable, with normal vaginal delivery at 36 weeks (pre-term birth). All developmental milestones were on target.

Ms. A lives at home with her mother, 6-year-old brother, and stepfather. Her parents are divorced, but her biological father has been involved in her upbringing. She is in seventh grade, but is home schooled after she withdrew from school because of multiple seizure episodes. Ms. A denied bullying at school although she had been punched by a peer. It was unclear if it was a single incident or bullying continued and she was hesitant to disclose it.

The authors’ observations

We focus on the amnesia because it has an acute onset and it seems this is the first time Ms. A presented with this symptom. There is no need to wait for neurology consultation, even though organic causes of amnesia need to be ruled out. Our plan is to develop rapport with Ms. A, and then administer a mental status examination focusing on memory assessment. We understand that, because Ms. A’s chief concern is amnesia, she might not be able to provide many details. We start the initial interview with the family in the patient’s room to understand family dynamics, and then interview Ms. A alone.

EVALUATION Memory problems

On initial psychiatric interview, Ms. A can recognize some of her family members. She is seen in clean attire, with short hair, lying in the bed with good eye contact and a calm demeanor. She seems to be difficult to engage because of her reserved nature.

Ms. A displays some psychomotor retardation. She reports her mood as tired, and her affect is flat and mood incongruent. She is alert and oriented to person only; not to place, time, or situation. She can do a simple spelling task, perform 5-minute recall of 3 words, complete serial 3 subtractions, repeat phrases, read aloud, focus on a coin task, and name simple objects. She does not compare similar objects or answer simple historical or factual questions.

Ms. A replies “I don’t know” to most historical questions, such as her birthday, favorite color, and family members; she does not answer when asked how many legs a dog has, who is the current or past president, what month the Fourth of July is in, or when Christmas is. She can complete some memory tasks on the Mini-Mental State Examination, but does not attempt many others. Ms. A says she is upset about her memory deficit, but her affect was flat. Her mood and her affect were incongruent. She describes a vision of a “girl with black holes [for eyes]” in the corner of her hospital room telling her not to believe anyone and that the interviewers are lying to her. Also, she reports that “the girl” tells her to hurt herself and others, but she is not going to act on the commands because she knows it is not the right thing to do. When we ask Ms. A about a history of substance abuse, she says she has never heard of drugs or alcohol.

Overall, she displays multiple apparent deficits in declarative memory, both episodic and semantic. Regarding non-declarative or procedural memory, she can dress herself, use the bathroom independently, order meals off the menu, and feed herself, among other routine tasks, without difficulty.

According to Ms. A’s mother, Ms. A has shown a decline in overall functioning and personality changes during the past 5 months. She started to cut herself superficially on her forearms 6 months ago and also tried to change her appearance with a new hairstyle when school started. She displayed noticeably intense and disturbing writings, artwork, and conversations with others over 3 to 4 months.

She started experiencing seizures, with 3 to 4 seizures a day; however, she could attend sleepovers seizure-free. She had prolonged periods of seizures lasting up to an hour, much longer than would be expected clinically. She also had requested to go to the cemetery for unclear reasons (because the spirit wanted her to visit), and was observed mumbling under her breath.

Six years ago, Ms. A’s 6-year-old sister tried to suffocate her infant brother. Child protective services was involved and the sister was hospitalized in a psychiatric facility, where she was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder; she was then transferred to foster care, and later placed in residential treatment. Her mother relinquished her parental rights and gave custody of Ms. A’s sister to the state.

Ms. A’s mother has a history of depression, but her younger brother is healthy. There is no history of autism, attention problems, tics, substance abuse, brain tumor, or intellectual disabilities in the family.

Which diagnosis does Ms. A’s presentation and history suggest?

a) dissociative amnesia

b) factitious disorder imposed on self

c) conversion disorder (neurological symptom disorder)

d) psychosis not otherwise specified

e) malingering

The authors’ observations

The history of unwitnessed seizures, sudden onset of visual hallucinations, and transient amnesia points to a possible postictal cause. Selective amnesia brings up the question of whether psychological components are driving the symptoms.

Her psychotic symptoms appear to be mediated by anxiety and possibly related to the trauma of losing her only sister when her mother relinquished custody to the state; the circumstances might have aroused feelings of insecurity or fear of abandonment and raised questions about her mother’s love toward her. Her sister’s abuse by a family member might have created reticence to trust others. These background experiences could be intensely conflicting at this age when the second separation individuation process commences, especially in an emotionally immature adolescent.

OUTCOME Medication change

The neurology team recommends discontinuing levetiracetam because the visual hallucinations, mood disturbance, and personality change could be adverse effects of the drug. Because of generalized uncontrolled body movements with staring episodes and unresponsiveness, an EEG is ordered to rule out ongoing seizures.

Ms. A recognizes the psychosomatic medicine team members when they interview her again. The team employs consistent reassurance and a non-confrontational approach. She spends 3 days in the medical unit during which she reports that the frequency of visual and auditory hallucinations decreases and her memory symptoms resolve. Her 24-hour EEG is negative for seizure activity, and the 24-hour video EEG does not show any signs of epileptogenic foci. Ms. A’s family declines inpatient psychiatric hospitalization.

Because of gradual improvement in Ms. A’s symptoms and no imminent safety concerns, she is discharged home with valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and oxcarbazepine, 1,200 mg/d, and follow-up appointments with her primary care physician, a neurologist, and a psychiatrist.

The authors’ observations

Dissociative amnesia

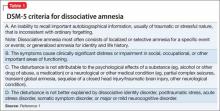

Generalized dissociative amnesia is difficult to differentiate from factitious disorder or malingering. According to DSM-5, there is loss of episodic memory in dissociative amnesia, in which the person is unable to recall the stressful event after trauma (Table 1).1 Although there have been case reports of dissociative amnesia with loss of semantic and procedural memory, episodic memory is the last to return.2 In Ms. A’s case, there was no immediate basis to explain amnesia onset, although she had experienced the trauma of losing her sister. She had episodic and mostly semantic memory loss.

Although organic causes can precipitate amnesia,3 Ms. A’s EEG and MRI results did not reflect that. Patients with a dissociative disorder often report some physical, sexual, or emotional abuse.4 Although Ms. A did not report any abuse, it cannot be completely ruled out because of her sister’s history of abuse.

Suicidality or self-injurious behavior is common among adults with dissociative amnesia, although it is not well studied in children.4,5 Generally, the constellation of primary dissociative symptoms that patients develop are forgetfulness, fragmentation, and emotional numbing. Ms. A presented with some of these features; did she, in fact, have dissociative amnesia?

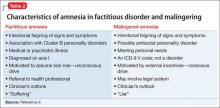

Factitious amnesia

Factious amnesia (Table 2)6 is a symptom of factious disorder in which amnesia appears with the motivation to assume a sick role.3 Ms. A’s amnesia garnered significant attention from her mother and other family members; this may have been related to insecurity in her family relationships because her sister was given up to the state. She also could be afraid of entering adolescence and leaving her sister behind. Did she want more time to bond with her mother? Did she experience emotional benefit from being cared for by medical professionals?7 Her affect during interviews was blunted and her attitude was nonchalant, and her multiple visits to the hospital since childhood for abdominal pain, abscesses (it isn’t clear whether the abscesses were related to self-injury and scratching), tics, seizures, and, recently, amnesia and hallucinations indicated some desire to occupy a sick role. Furthermore, the severity of her symptoms seemed to be increasing over time, from somatic to neurologic (seizure-like episodes) to significant and less frequent psychiatric symptoms (amnesia and hallucinations). One could speculate that her symptoms were escalating because she was not receiving the attention she needed.

Malingered amnesia

Although malingering is not a psychiatric diagnosis, it can be a focus of clinical attention. It is challenging to identify malingered cognitive impairments.8 Children often have difficulty malingering symptoms because they have limited understanding of the illness they are trying to simulate.9 Many malingerers do not want to participate in their medical work up and might exhibit a hostile attitude toward examiners (Table 26). Clinicians could rely on family to provide information regarding history and inconsistencies in clinical deficits.9 The clinical interview, mental status examination, and collateral information are crucial for identifying malingering.

Most of Ms. A’s seizure-like episodes happened in specific contexts, such as in school, but not at friends’ houses, raising the question of whether she is aware of her episodes. Ms. A’s grades are consistently good; because she is being home schooled, there is no secondary gain from not going to school. There is no other reason to speculate that she was malingering.

The inconsistency of Ms. A’s symptoms and her compliance with assessment and treatment did not reflect malingering. Interestingly, Ms. A’s amnesia was retrograde in nature. There have been more studies on malingered anterograde amnesia8 than on retrograde amnesia, making her presentation even more unusual.

Amnesia presenting as conversion disorder

Amnesia as a symptom of conversion disorder is referred as psychogenic amnesia; the memory loss mostly is isolated retrograde amnesia.10 Ms. A likely had unconsciously produced symptoms of non-epileptic seizures, followed by auditory and visual hallucinations not related to her seizures, and then later developed selective transient amnesia. Conversion disorder seemed to be the diagnosis most consistent with her indifference (“la belle indifference”) and the significant attention she gained from the acute memory loss (Table 3).1 It seemed that she developed multiple symptoms in progression leading toward a conversion disorder diagnosis. The question arises whether Ms. A’s presentation is a gradually increasing cry for help or reflects depressive or anxiety symptoms, which often are comorbid with conversion disorder.

FOLLOW-UP Suicide attempt

Ms. A has frequent visits to the ED with symptoms of syncope and seizures and undergoes medical work-up and multiple EEGs. A prolonged 5-day video EEG is performed to assess seizure episodes after AEDs were withdrawn, but no seizure activity is elicited. She also has an ED visit for recurrent tic emergence.

The last visit in the ED is for a suicide attempt with overdose of an unknown quantity of unspecified pills. Ms. A talks to a social worker, who reports that Ms. A needed answers to such questions as why her grandfather abused her sister? Could she have stopped them and made a difference for the family?

The authors’ observations

Conversion disorder arises from unconscious psychological conflicts, needs, or responses to trauma. Ms. A’s consistent conflict about her sister and grandfather’s relationship was evident from occasions when she tried to confide in hospital staff. During an ED visit, she reported her sister’s abuse to a staff member. Another time, while recovering from sedation, she spontaneously spoke about her sister’s abuse. When asked again, she said she did not remember saying it.

Freud said that patients develop conversion disorder to avoid unacceptable conflicting thoughts and feelings.10 It appeared that Ms. A was struggling with these questions because she brought them up again when she visited the ED after the suicide attempt.

Dissociative symptoms arise from unstable parenting and disciplining styles with variable family dynamics. Patients show extreme detachment and emotional unresponsiveness akin to attachment disorder.11 Ms. A had inconsistent parenting because both her stepfather and biological father were involved with her care. Her mother had relinquished her parental rights to her sister, which indicated some attachment issues.

Ms. A’s idea that her mother was indifferent stemmed from her uncaring approach toward her sister and not able to understand her emotionally. Her amnesia could be thought of as “I don’t know you because I don’t remember that I am related to you.” The traumas of infancy (referred to as hidden traumas) that were a result of parent-child mismatch of needs and availability at times of distress might not be obvious to the examiner.11

Although Ms. A’s infancy was reported to be unremarkable, there always is a question, especially in a consultation-liaison setting, of whether conversion disorder might be masking an attachment problem. Perhaps with long-term psychotherapy, an attachment issue would be revealed.

Excluding an organic cause or a neurologic disorder is important when diagnosing conversion disorder10; Ms. A’s negative neurologic tests favored a diagnosis of amnesia due to conversion disorder. It appears that, although Ms. A presented with “transient amnesia,” she had underlying psychiatric symptoms, likely depression or anxiety. We were concerned about possible psychiatric comorbidity and recommended inpatient hospitalization to clarify the diagnosis and provide intensive therapy, but her family declined. She may have received outpatient services, but that was not documented.

Bottom Line

Psychogenic amnesia can be a form of conversion disorder or a symptom of

malingering; can occur in dissociative disorder; and can be factitious in nature.

Regardless of the cause, the condition requires continuous close follow up. Although organic causes of amnesia should be ruled out, mental health care can help address comorbid psychiatric symptoms and might change the course of the illness.

Related Resources

• Byatt N, Toor R. Young, pregnant, ataxic—and jilted. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):44-49.

• Leipsic J. A teen who is wasting away. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(6):40-45.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Quetiapine • Seroquel

Levetiracetam • Keppra Valproic acid • Depakote

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. van der Hart O, Nijenhuis E. Generalized dissociative amnesia: episodic, semantic and procedural memories lost and found. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(5):589-560.

3. Ehrlich S, Pfeiffer E, Salbach H, et al. Factitious disorder in children and adolescents: a retrospective study. Psychosomatics. 2008;45(5):392-398.

4. Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, et al. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271-2276.

5. Kisiel CL, Lyons JS. Dissociation as a mediator of psychopathology among sexually abused children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1034-1039.

6. Worley CB, Feldman MD, Hamilton JC. The case of factitious disorder versus malingering. http://www.psychiatrictimes. com/munchausen-syndrome/case-factitious-disorder-versus-malingering. Published October 30, 2009. Accessed January 27, 2015.

7. Hagglund LA. Challenges in the treatment of factitious disorder: a case study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23(1):58-64.

8. Jenkins KG, Kapur N, Kopelman MD. Retrograde amnesia and malingering. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22(6):601-605.

9. Walker JS. Malingering in children: fibs and faking. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20(3):547-556.

10. Levenson JL. Psychiatric issues in neurology, part 4: amnestic syndromes and conversion disorder. Primary Psychiatry. http://primarypsychiatry.com/psychiatric-issues-in-neurology-part-4-amnestic-syndromes-and-conversion-disorder. Published March 1, 2008. Accessed February 3, 2015.

11. Lyons-Ruth K, Dutra L, Schuder MR, et al. From infant attachment disorganization to adult dissociation: relational adaptations or traumatic experiences? Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29(1):63-86, viii.

CASE Seizures, amnesia

Ms. A, age 13, who has a history of seizures, presents to the emergency department (ED) with sudden onset of memory loss. Her family reports that she had been spending a normal evening at home with family and friends. After going to the bathroom, Ms. A became acutely confused and extremely upset, had slurred speech, and did not recognize anyone in the room except her mother.

Initial neurologic examination in the ED reports that Ms. A does not remember recent or remote past events. Her family denies any recent stressors.

Vital signs are within normal range. She has mild muscle soreness and gait instability, which is attributed to a presumed postictal phase. Her medication regimen includes: levetiracetam, 500 mg, 3 times a day; valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d; and oxcarbazepine, 2,400 mg/d, for seizure management.

Complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel are within normal limits. Pregnancy test is negative. Urine toxicology report is negative. Serum valproic acid level is 71 μg/mL; oxcarbazepine level, <2 μg/mL; ammonia level, 71 μg/dL (reference range, 15 to 45 μg/dL). Other than the aforementioned deficits, she is neurologically intact. The team thinks that her symptoms are part of a postictal phase of an unwitnessed seizure.

Ms. A is admitted to the inpatient medical unit for further work up. Along with the memory loss and seizures, she reports visual hallucinations.

What could be causing Ms. A’s amnesia?

a) a seizure disorder

b) malingering

c) posttraumatic stress disorder

d) traumatic brain injury

HISTORY Repeat ED visits

Ms. A’s mother reports that 3 years ago her daughter was treated for tics with quetiapine and aripiprazole, prescribed by a primary care physician. She received a short course of counseling 6 years ago after her sister was sexually abused by her grandfather. Approximately 6 months ago, Ms. A engaged in self-injurious behavior by cutting herself, and she briefly received counseling. There is no history of suicide attempts, psychiatric hospitalization, or a psychiatric diagnosis.

Medical and surgical history include viral meningitis at age 6 months. Medical records show a visit to the ED for abdominal pain after a classmate punched her in the abdomen, which resolved with supportive care. She was given a diagnosis of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections 6 years ago.

Ms. A developed multiple recurrent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus abscesses a year ago, which lasted for 4 months; it was noted that she was self-inoculating by scratching eczema. She had a possible syncopal episode 5 months ago, but the medical work-up was normal. The pediatric neurology service diagnosed and treated seizures 4 months ago.

Levetiracetam was prescribed after a possible syncopal episode followed by a tonic-clonic seizure. Because she was still having seizure-like episodes with a single antiepileptic drug (AED), oxcarbazepine, then valproic acid were added. Whether her seizures were generalized or partial was inconclusive. The seizures were followed by a postictal phase lasting 3 minutes to 1 hour. Her last generalized tonic-clonic seizure was 1 month before admission.

Ms. A had 3 MRI studies of the brain over the past 3 years, which showed consistent and unchanged multifocal punctate white matter lesions. The findings represented gliosis from an old perivascular inflammation, trauma, or ischemic damage. There is no history of traumatic brain injury.

Her perinatal history is unremarkable, with normal vaginal delivery at 36 weeks (pre-term birth). All developmental milestones were on target.

Ms. A lives at home with her mother, 6-year-old brother, and stepfather. Her parents are divorced, but her biological father has been involved in her upbringing. She is in seventh grade, but is home schooled after she withdrew from school because of multiple seizure episodes. Ms. A denied bullying at school although she had been punched by a peer. It was unclear if it was a single incident or bullying continued and she was hesitant to disclose it.

The authors’ observations

We focus on the amnesia because it has an acute onset and it seems this is the first time Ms. A presented with this symptom. There is no need to wait for neurology consultation, even though organic causes of amnesia need to be ruled out. Our plan is to develop rapport with Ms. A, and then administer a mental status examination focusing on memory assessment. We understand that, because Ms. A’s chief concern is amnesia, she might not be able to provide many details. We start the initial interview with the family in the patient’s room to understand family dynamics, and then interview Ms. A alone.

EVALUATION Memory problems

On initial psychiatric interview, Ms. A can recognize some of her family members. She is seen in clean attire, with short hair, lying in the bed with good eye contact and a calm demeanor. She seems to be difficult to engage because of her reserved nature.

Ms. A displays some psychomotor retardation. She reports her mood as tired, and her affect is flat and mood incongruent. She is alert and oriented to person only; not to place, time, or situation. She can do a simple spelling task, perform 5-minute recall of 3 words, complete serial 3 subtractions, repeat phrases, read aloud, focus on a coin task, and name simple objects. She does not compare similar objects or answer simple historical or factual questions.

Ms. A replies “I don’t know” to most historical questions, such as her birthday, favorite color, and family members; she does not answer when asked how many legs a dog has, who is the current or past president, what month the Fourth of July is in, or when Christmas is. She can complete some memory tasks on the Mini-Mental State Examination, but does not attempt many others. Ms. A says she is upset about her memory deficit, but her affect was flat. Her mood and her affect were incongruent. She describes a vision of a “girl with black holes [for eyes]” in the corner of her hospital room telling her not to believe anyone and that the interviewers are lying to her. Also, she reports that “the girl” tells her to hurt herself and others, but she is not going to act on the commands because she knows it is not the right thing to do. When we ask Ms. A about a history of substance abuse, she says she has never heard of drugs or alcohol.

Overall, she displays multiple apparent deficits in declarative memory, both episodic and semantic. Regarding non-declarative or procedural memory, she can dress herself, use the bathroom independently, order meals off the menu, and feed herself, among other routine tasks, without difficulty.

According to Ms. A’s mother, Ms. A has shown a decline in overall functioning and personality changes during the past 5 months. She started to cut herself superficially on her forearms 6 months ago and also tried to change her appearance with a new hairstyle when school started. She displayed noticeably intense and disturbing writings, artwork, and conversations with others over 3 to 4 months.

She started experiencing seizures, with 3 to 4 seizures a day; however, she could attend sleepovers seizure-free. She had prolonged periods of seizures lasting up to an hour, much longer than would be expected clinically. She also had requested to go to the cemetery for unclear reasons (because the spirit wanted her to visit), and was observed mumbling under her breath.

Six years ago, Ms. A’s 6-year-old sister tried to suffocate her infant brother. Child protective services was involved and the sister was hospitalized in a psychiatric facility, where she was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder; she was then transferred to foster care, and later placed in residential treatment. Her mother relinquished her parental rights and gave custody of Ms. A’s sister to the state.

Ms. A’s mother has a history of depression, but her younger brother is healthy. There is no history of autism, attention problems, tics, substance abuse, brain tumor, or intellectual disabilities in the family.

Which diagnosis does Ms. A’s presentation and history suggest?

a) dissociative amnesia

b) factitious disorder imposed on self

c) conversion disorder (neurological symptom disorder)

d) psychosis not otherwise specified

e) malingering

The authors’ observations

The history of unwitnessed seizures, sudden onset of visual hallucinations, and transient amnesia points to a possible postictal cause. Selective amnesia brings up the question of whether psychological components are driving the symptoms.

Her psychotic symptoms appear to be mediated by anxiety and possibly related to the trauma of losing her only sister when her mother relinquished custody to the state; the circumstances might have aroused feelings of insecurity or fear of abandonment and raised questions about her mother’s love toward her. Her sister’s abuse by a family member might have created reticence to trust others. These background experiences could be intensely conflicting at this age when the second separation individuation process commences, especially in an emotionally immature adolescent.

OUTCOME Medication change

The neurology team recommends discontinuing levetiracetam because the visual hallucinations, mood disturbance, and personality change could be adverse effects of the drug. Because of generalized uncontrolled body movements with staring episodes and unresponsiveness, an EEG is ordered to rule out ongoing seizures.

Ms. A recognizes the psychosomatic medicine team members when they interview her again. The team employs consistent reassurance and a non-confrontational approach. She spends 3 days in the medical unit during which she reports that the frequency of visual and auditory hallucinations decreases and her memory symptoms resolve. Her 24-hour EEG is negative for seizure activity, and the 24-hour video EEG does not show any signs of epileptogenic foci. Ms. A’s family declines inpatient psychiatric hospitalization.

Because of gradual improvement in Ms. A’s symptoms and no imminent safety concerns, she is discharged home with valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and oxcarbazepine, 1,200 mg/d, and follow-up appointments with her primary care physician, a neurologist, and a psychiatrist.

The authors’ observations

Dissociative amnesia

Generalized dissociative amnesia is difficult to differentiate from factitious disorder or malingering. According to DSM-5, there is loss of episodic memory in dissociative amnesia, in which the person is unable to recall the stressful event after trauma (Table 1).1 Although there have been case reports of dissociative amnesia with loss of semantic and procedural memory, episodic memory is the last to return.2 In Ms. A’s case, there was no immediate basis to explain amnesia onset, although she had experienced the trauma of losing her sister. She had episodic and mostly semantic memory loss.

Although organic causes can precipitate amnesia,3 Ms. A’s EEG and MRI results did not reflect that. Patients with a dissociative disorder often report some physical, sexual, or emotional abuse.4 Although Ms. A did not report any abuse, it cannot be completely ruled out because of her sister’s history of abuse.

Suicidality or self-injurious behavior is common among adults with dissociative amnesia, although it is not well studied in children.4,5 Generally, the constellation of primary dissociative symptoms that patients develop are forgetfulness, fragmentation, and emotional numbing. Ms. A presented with some of these features; did she, in fact, have dissociative amnesia?

Factitious amnesia

Factious amnesia (Table 2)6 is a symptom of factious disorder in which amnesia appears with the motivation to assume a sick role.3 Ms. A’s amnesia garnered significant attention from her mother and other family members; this may have been related to insecurity in her family relationships because her sister was given up to the state. She also could be afraid of entering adolescence and leaving her sister behind. Did she want more time to bond with her mother? Did she experience emotional benefit from being cared for by medical professionals?7 Her affect during interviews was blunted and her attitude was nonchalant, and her multiple visits to the hospital since childhood for abdominal pain, abscesses (it isn’t clear whether the abscesses were related to self-injury and scratching), tics, seizures, and, recently, amnesia and hallucinations indicated some desire to occupy a sick role. Furthermore, the severity of her symptoms seemed to be increasing over time, from somatic to neurologic (seizure-like episodes) to significant and less frequent psychiatric symptoms (amnesia and hallucinations). One could speculate that her symptoms were escalating because she was not receiving the attention she needed.

Malingered amnesia

Although malingering is not a psychiatric diagnosis, it can be a focus of clinical attention. It is challenging to identify malingered cognitive impairments.8 Children often have difficulty malingering symptoms because they have limited understanding of the illness they are trying to simulate.9 Many malingerers do not want to participate in their medical work up and might exhibit a hostile attitude toward examiners (Table 26). Clinicians could rely on family to provide information regarding history and inconsistencies in clinical deficits.9 The clinical interview, mental status examination, and collateral information are crucial for identifying malingering.

Most of Ms. A’s seizure-like episodes happened in specific contexts, such as in school, but not at friends’ houses, raising the question of whether she is aware of her episodes. Ms. A’s grades are consistently good; because she is being home schooled, there is no secondary gain from not going to school. There is no other reason to speculate that she was malingering.

The inconsistency of Ms. A’s symptoms and her compliance with assessment and treatment did not reflect malingering. Interestingly, Ms. A’s amnesia was retrograde in nature. There have been more studies on malingered anterograde amnesia8 than on retrograde amnesia, making her presentation even more unusual.

Amnesia presenting as conversion disorder

Amnesia as a symptom of conversion disorder is referred as psychogenic amnesia; the memory loss mostly is isolated retrograde amnesia.10 Ms. A likely had unconsciously produced symptoms of non-epileptic seizures, followed by auditory and visual hallucinations not related to her seizures, and then later developed selective transient amnesia. Conversion disorder seemed to be the diagnosis most consistent with her indifference (“la belle indifference”) and the significant attention she gained from the acute memory loss (Table 3).1 It seemed that she developed multiple symptoms in progression leading toward a conversion disorder diagnosis. The question arises whether Ms. A’s presentation is a gradually increasing cry for help or reflects depressive or anxiety symptoms, which often are comorbid with conversion disorder.

FOLLOW-UP Suicide attempt

Ms. A has frequent visits to the ED with symptoms of syncope and seizures and undergoes medical work-up and multiple EEGs. A prolonged 5-day video EEG is performed to assess seizure episodes after AEDs were withdrawn, but no seizure activity is elicited. She also has an ED visit for recurrent tic emergence.

The last visit in the ED is for a suicide attempt with overdose of an unknown quantity of unspecified pills. Ms. A talks to a social worker, who reports that Ms. A needed answers to such questions as why her grandfather abused her sister? Could she have stopped them and made a difference for the family?

The authors’ observations

Conversion disorder arises from unconscious psychological conflicts, needs, or responses to trauma. Ms. A’s consistent conflict about her sister and grandfather’s relationship was evident from occasions when she tried to confide in hospital staff. During an ED visit, she reported her sister’s abuse to a staff member. Another time, while recovering from sedation, she spontaneously spoke about her sister’s abuse. When asked again, she said she did not remember saying it.

Freud said that patients develop conversion disorder to avoid unacceptable conflicting thoughts and feelings.10 It appeared that Ms. A was struggling with these questions because she brought them up again when she visited the ED after the suicide attempt.

Dissociative symptoms arise from unstable parenting and disciplining styles with variable family dynamics. Patients show extreme detachment and emotional unresponsiveness akin to attachment disorder.11 Ms. A had inconsistent parenting because both her stepfather and biological father were involved with her care. Her mother had relinquished her parental rights to her sister, which indicated some attachment issues.

Ms. A’s idea that her mother was indifferent stemmed from her uncaring approach toward her sister and not able to understand her emotionally. Her amnesia could be thought of as “I don’t know you because I don’t remember that I am related to you.” The traumas of infancy (referred to as hidden traumas) that were a result of parent-child mismatch of needs and availability at times of distress might not be obvious to the examiner.11

Although Ms. A’s infancy was reported to be unremarkable, there always is a question, especially in a consultation-liaison setting, of whether conversion disorder might be masking an attachment problem. Perhaps with long-term psychotherapy, an attachment issue would be revealed.

Excluding an organic cause or a neurologic disorder is important when diagnosing conversion disorder10; Ms. A’s negative neurologic tests favored a diagnosis of amnesia due to conversion disorder. It appears that, although Ms. A presented with “transient amnesia,” she had underlying psychiatric symptoms, likely depression or anxiety. We were concerned about possible psychiatric comorbidity and recommended inpatient hospitalization to clarify the diagnosis and provide intensive therapy, but her family declined. She may have received outpatient services, but that was not documented.

Bottom Line

Psychogenic amnesia can be a form of conversion disorder or a symptom of

malingering; can occur in dissociative disorder; and can be factitious in nature.

Regardless of the cause, the condition requires continuous close follow up. Although organic causes of amnesia should be ruled out, mental health care can help address comorbid psychiatric symptoms and might change the course of the illness.

Related Resources

• Byatt N, Toor R. Young, pregnant, ataxic—and jilted. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):44-49.

• Leipsic J. A teen who is wasting away. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(6):40-45.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Quetiapine • Seroquel

Levetiracetam • Keppra Valproic acid • Depakote

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Seizures, amnesia

Ms. A, age 13, who has a history of seizures, presents to the emergency department (ED) with sudden onset of memory loss. Her family reports that she had been spending a normal evening at home with family and friends. After going to the bathroom, Ms. A became acutely confused and extremely upset, had slurred speech, and did not recognize anyone in the room except her mother.

Initial neurologic examination in the ED reports that Ms. A does not remember recent or remote past events. Her family denies any recent stressors.

Vital signs are within normal range. She has mild muscle soreness and gait instability, which is attributed to a presumed postictal phase. Her medication regimen includes: levetiracetam, 500 mg, 3 times a day; valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d; and oxcarbazepine, 2,400 mg/d, for seizure management.

Complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel are within normal limits. Pregnancy test is negative. Urine toxicology report is negative. Serum valproic acid level is 71 μg/mL; oxcarbazepine level, <2 μg/mL; ammonia level, 71 μg/dL (reference range, 15 to 45 μg/dL). Other than the aforementioned deficits, she is neurologically intact. The team thinks that her symptoms are part of a postictal phase of an unwitnessed seizure.

Ms. A is admitted to the inpatient medical unit for further work up. Along with the memory loss and seizures, she reports visual hallucinations.

What could be causing Ms. A’s amnesia?

a) a seizure disorder

b) malingering

c) posttraumatic stress disorder

d) traumatic brain injury

HISTORY Repeat ED visits

Ms. A’s mother reports that 3 years ago her daughter was treated for tics with quetiapine and aripiprazole, prescribed by a primary care physician. She received a short course of counseling 6 years ago after her sister was sexually abused by her grandfather. Approximately 6 months ago, Ms. A engaged in self-injurious behavior by cutting herself, and she briefly received counseling. There is no history of suicide attempts, psychiatric hospitalization, or a psychiatric diagnosis.

Medical and surgical history include viral meningitis at age 6 months. Medical records show a visit to the ED for abdominal pain after a classmate punched her in the abdomen, which resolved with supportive care. She was given a diagnosis of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections 6 years ago.

Ms. A developed multiple recurrent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus abscesses a year ago, which lasted for 4 months; it was noted that she was self-inoculating by scratching eczema. She had a possible syncopal episode 5 months ago, but the medical work-up was normal. The pediatric neurology service diagnosed and treated seizures 4 months ago.

Levetiracetam was prescribed after a possible syncopal episode followed by a tonic-clonic seizure. Because she was still having seizure-like episodes with a single antiepileptic drug (AED), oxcarbazepine, then valproic acid were added. Whether her seizures were generalized or partial was inconclusive. The seizures were followed by a postictal phase lasting 3 minutes to 1 hour. Her last generalized tonic-clonic seizure was 1 month before admission.

Ms. A had 3 MRI studies of the brain over the past 3 years, which showed consistent and unchanged multifocal punctate white matter lesions. The findings represented gliosis from an old perivascular inflammation, trauma, or ischemic damage. There is no history of traumatic brain injury.

Her perinatal history is unremarkable, with normal vaginal delivery at 36 weeks (pre-term birth). All developmental milestones were on target.

Ms. A lives at home with her mother, 6-year-old brother, and stepfather. Her parents are divorced, but her biological father has been involved in her upbringing. She is in seventh grade, but is home schooled after she withdrew from school because of multiple seizure episodes. Ms. A denied bullying at school although she had been punched by a peer. It was unclear if it was a single incident or bullying continued and she was hesitant to disclose it.

The authors’ observations

We focus on the amnesia because it has an acute onset and it seems this is the first time Ms. A presented with this symptom. There is no need to wait for neurology consultation, even though organic causes of amnesia need to be ruled out. Our plan is to develop rapport with Ms. A, and then administer a mental status examination focusing on memory assessment. We understand that, because Ms. A’s chief concern is amnesia, she might not be able to provide many details. We start the initial interview with the family in the patient’s room to understand family dynamics, and then interview Ms. A alone.

EVALUATION Memory problems

On initial psychiatric interview, Ms. A can recognize some of her family members. She is seen in clean attire, with short hair, lying in the bed with good eye contact and a calm demeanor. She seems to be difficult to engage because of her reserved nature.

Ms. A displays some psychomotor retardation. She reports her mood as tired, and her affect is flat and mood incongruent. She is alert and oriented to person only; not to place, time, or situation. She can do a simple spelling task, perform 5-minute recall of 3 words, complete serial 3 subtractions, repeat phrases, read aloud, focus on a coin task, and name simple objects. She does not compare similar objects or answer simple historical or factual questions.

Ms. A replies “I don’t know” to most historical questions, such as her birthday, favorite color, and family members; she does not answer when asked how many legs a dog has, who is the current or past president, what month the Fourth of July is in, or when Christmas is. She can complete some memory tasks on the Mini-Mental State Examination, but does not attempt many others. Ms. A says she is upset about her memory deficit, but her affect was flat. Her mood and her affect were incongruent. She describes a vision of a “girl with black holes [for eyes]” in the corner of her hospital room telling her not to believe anyone and that the interviewers are lying to her. Also, she reports that “the girl” tells her to hurt herself and others, but she is not going to act on the commands because she knows it is not the right thing to do. When we ask Ms. A about a history of substance abuse, she says she has never heard of drugs or alcohol.

Overall, she displays multiple apparent deficits in declarative memory, both episodic and semantic. Regarding non-declarative or procedural memory, she can dress herself, use the bathroom independently, order meals off the menu, and feed herself, among other routine tasks, without difficulty.

According to Ms. A’s mother, Ms. A has shown a decline in overall functioning and personality changes during the past 5 months. She started to cut herself superficially on her forearms 6 months ago and also tried to change her appearance with a new hairstyle when school started. She displayed noticeably intense and disturbing writings, artwork, and conversations with others over 3 to 4 months.

She started experiencing seizures, with 3 to 4 seizures a day; however, she could attend sleepovers seizure-free. She had prolonged periods of seizures lasting up to an hour, much longer than would be expected clinically. She also had requested to go to the cemetery for unclear reasons (because the spirit wanted her to visit), and was observed mumbling under her breath.

Six years ago, Ms. A’s 6-year-old sister tried to suffocate her infant brother. Child protective services was involved and the sister was hospitalized in a psychiatric facility, where she was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder; she was then transferred to foster care, and later placed in residential treatment. Her mother relinquished her parental rights and gave custody of Ms. A’s sister to the state.

Ms. A’s mother has a history of depression, but her younger brother is healthy. There is no history of autism, attention problems, tics, substance abuse, brain tumor, or intellectual disabilities in the family.

Which diagnosis does Ms. A’s presentation and history suggest?

a) dissociative amnesia

b) factitious disorder imposed on self

c) conversion disorder (neurological symptom disorder)

d) psychosis not otherwise specified

e) malingering

The authors’ observations

The history of unwitnessed seizures, sudden onset of visual hallucinations, and transient amnesia points to a possible postictal cause. Selective amnesia brings up the question of whether psychological components are driving the symptoms.

Her psychotic symptoms appear to be mediated by anxiety and possibly related to the trauma of losing her only sister when her mother relinquished custody to the state; the circumstances might have aroused feelings of insecurity or fear of abandonment and raised questions about her mother’s love toward her. Her sister’s abuse by a family member might have created reticence to trust others. These background experiences could be intensely conflicting at this age when the second separation individuation process commences, especially in an emotionally immature adolescent.

OUTCOME Medication change

The neurology team recommends discontinuing levetiracetam because the visual hallucinations, mood disturbance, and personality change could be adverse effects of the drug. Because of generalized uncontrolled body movements with staring episodes and unresponsiveness, an EEG is ordered to rule out ongoing seizures.

Ms. A recognizes the psychosomatic medicine team members when they interview her again. The team employs consistent reassurance and a non-confrontational approach. She spends 3 days in the medical unit during which she reports that the frequency of visual and auditory hallucinations decreases and her memory symptoms resolve. Her 24-hour EEG is negative for seizure activity, and the 24-hour video EEG does not show any signs of epileptogenic foci. Ms. A’s family declines inpatient psychiatric hospitalization.

Because of gradual improvement in Ms. A’s symptoms and no imminent safety concerns, she is discharged home with valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and oxcarbazepine, 1,200 mg/d, and follow-up appointments with her primary care physician, a neurologist, and a psychiatrist.

The authors’ observations

Dissociative amnesia

Generalized dissociative amnesia is difficult to differentiate from factitious disorder or malingering. According to DSM-5, there is loss of episodic memory in dissociative amnesia, in which the person is unable to recall the stressful event after trauma (Table 1).1 Although there have been case reports of dissociative amnesia with loss of semantic and procedural memory, episodic memory is the last to return.2 In Ms. A’s case, there was no immediate basis to explain amnesia onset, although she had experienced the trauma of losing her sister. She had episodic and mostly semantic memory loss.

Although organic causes can precipitate amnesia,3 Ms. A’s EEG and MRI results did not reflect that. Patients with a dissociative disorder often report some physical, sexual, or emotional abuse.4 Although Ms. A did not report any abuse, it cannot be completely ruled out because of her sister’s history of abuse.

Suicidality or self-injurious behavior is common among adults with dissociative amnesia, although it is not well studied in children.4,5 Generally, the constellation of primary dissociative symptoms that patients develop are forgetfulness, fragmentation, and emotional numbing. Ms. A presented with some of these features; did she, in fact, have dissociative amnesia?

Factitious amnesia

Factious amnesia (Table 2)6 is a symptom of factious disorder in which amnesia appears with the motivation to assume a sick role.3 Ms. A’s amnesia garnered significant attention from her mother and other family members; this may have been related to insecurity in her family relationships because her sister was given up to the state. She also could be afraid of entering adolescence and leaving her sister behind. Did she want more time to bond with her mother? Did she experience emotional benefit from being cared for by medical professionals?7 Her affect during interviews was blunted and her attitude was nonchalant, and her multiple visits to the hospital since childhood for abdominal pain, abscesses (it isn’t clear whether the abscesses were related to self-injury and scratching), tics, seizures, and, recently, amnesia and hallucinations indicated some desire to occupy a sick role. Furthermore, the severity of her symptoms seemed to be increasing over time, from somatic to neurologic (seizure-like episodes) to significant and less frequent psychiatric symptoms (amnesia and hallucinations). One could speculate that her symptoms were escalating because she was not receiving the attention she needed.

Malingered amnesia

Although malingering is not a psychiatric diagnosis, it can be a focus of clinical attention. It is challenging to identify malingered cognitive impairments.8 Children often have difficulty malingering symptoms because they have limited understanding of the illness they are trying to simulate.9 Many malingerers do not want to participate in their medical work up and might exhibit a hostile attitude toward examiners (Table 26). Clinicians could rely on family to provide information regarding history and inconsistencies in clinical deficits.9 The clinical interview, mental status examination, and collateral information are crucial for identifying malingering.

Most of Ms. A’s seizure-like episodes happened in specific contexts, such as in school, but not at friends’ houses, raising the question of whether she is aware of her episodes. Ms. A’s grades are consistently good; because she is being home schooled, there is no secondary gain from not going to school. There is no other reason to speculate that she was malingering.

The inconsistency of Ms. A’s symptoms and her compliance with assessment and treatment did not reflect malingering. Interestingly, Ms. A’s amnesia was retrograde in nature. There have been more studies on malingered anterograde amnesia8 than on retrograde amnesia, making her presentation even more unusual.

Amnesia presenting as conversion disorder

Amnesia as a symptom of conversion disorder is referred as psychogenic amnesia; the memory loss mostly is isolated retrograde amnesia.10 Ms. A likely had unconsciously produced symptoms of non-epileptic seizures, followed by auditory and visual hallucinations not related to her seizures, and then later developed selective transient amnesia. Conversion disorder seemed to be the diagnosis most consistent with her indifference (“la belle indifference”) and the significant attention she gained from the acute memory loss (Table 3).1 It seemed that she developed multiple symptoms in progression leading toward a conversion disorder diagnosis. The question arises whether Ms. A’s presentation is a gradually increasing cry for help or reflects depressive or anxiety symptoms, which often are comorbid with conversion disorder.

FOLLOW-UP Suicide attempt

Ms. A has frequent visits to the ED with symptoms of syncope and seizures and undergoes medical work-up and multiple EEGs. A prolonged 5-day video EEG is performed to assess seizure episodes after AEDs were withdrawn, but no seizure activity is elicited. She also has an ED visit for recurrent tic emergence.

The last visit in the ED is for a suicide attempt with overdose of an unknown quantity of unspecified pills. Ms. A talks to a social worker, who reports that Ms. A needed answers to such questions as why her grandfather abused her sister? Could she have stopped them and made a difference for the family?

The authors’ observations

Conversion disorder arises from unconscious psychological conflicts, needs, or responses to trauma. Ms. A’s consistent conflict about her sister and grandfather’s relationship was evident from occasions when she tried to confide in hospital staff. During an ED visit, she reported her sister’s abuse to a staff member. Another time, while recovering from sedation, she spontaneously spoke about her sister’s abuse. When asked again, she said she did not remember saying it.

Freud said that patients develop conversion disorder to avoid unacceptable conflicting thoughts and feelings.10 It appeared that Ms. A was struggling with these questions because she brought them up again when she visited the ED after the suicide attempt.

Dissociative symptoms arise from unstable parenting and disciplining styles with variable family dynamics. Patients show extreme detachment and emotional unresponsiveness akin to attachment disorder.11 Ms. A had inconsistent parenting because both her stepfather and biological father were involved with her care. Her mother had relinquished her parental rights to her sister, which indicated some attachment issues.

Ms. A’s idea that her mother was indifferent stemmed from her uncaring approach toward her sister and not able to understand her emotionally. Her amnesia could be thought of as “I don’t know you because I don’t remember that I am related to you.” The traumas of infancy (referred to as hidden traumas) that were a result of parent-child mismatch of needs and availability at times of distress might not be obvious to the examiner.11

Although Ms. A’s infancy was reported to be unremarkable, there always is a question, especially in a consultation-liaison setting, of whether conversion disorder might be masking an attachment problem. Perhaps with long-term psychotherapy, an attachment issue would be revealed.

Excluding an organic cause or a neurologic disorder is important when diagnosing conversion disorder10; Ms. A’s negative neurologic tests favored a diagnosis of amnesia due to conversion disorder. It appears that, although Ms. A presented with “transient amnesia,” she had underlying psychiatric symptoms, likely depression or anxiety. We were concerned about possible psychiatric comorbidity and recommended inpatient hospitalization to clarify the diagnosis and provide intensive therapy, but her family declined. She may have received outpatient services, but that was not documented.

Bottom Line

Psychogenic amnesia can be a form of conversion disorder or a symptom of

malingering; can occur in dissociative disorder; and can be factitious in nature.

Regardless of the cause, the condition requires continuous close follow up. Although organic causes of amnesia should be ruled out, mental health care can help address comorbid psychiatric symptoms and might change the course of the illness.

Related Resources

• Byatt N, Toor R. Young, pregnant, ataxic—and jilted. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):44-49.

• Leipsic J. A teen who is wasting away. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(6):40-45.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Quetiapine • Seroquel

Levetiracetam • Keppra Valproic acid • Depakote

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. van der Hart O, Nijenhuis E. Generalized dissociative amnesia: episodic, semantic and procedural memories lost and found. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(5):589-560.

3. Ehrlich S, Pfeiffer E, Salbach H, et al. Factitious disorder in children and adolescents: a retrospective study. Psychosomatics. 2008;45(5):392-398.

4. Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, et al. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271-2276.

5. Kisiel CL, Lyons JS. Dissociation as a mediator of psychopathology among sexually abused children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1034-1039.

6. Worley CB, Feldman MD, Hamilton JC. The case of factitious disorder versus malingering. http://www.psychiatrictimes. com/munchausen-syndrome/case-factitious-disorder-versus-malingering. Published October 30, 2009. Accessed January 27, 2015.

7. Hagglund LA. Challenges in the treatment of factitious disorder: a case study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23(1):58-64.

8. Jenkins KG, Kapur N, Kopelman MD. Retrograde amnesia and malingering. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22(6):601-605.

9. Walker JS. Malingering in children: fibs and faking. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20(3):547-556.

10. Levenson JL. Psychiatric issues in neurology, part 4: amnestic syndromes and conversion disorder. Primary Psychiatry. http://primarypsychiatry.com/psychiatric-issues-in-neurology-part-4-amnestic-syndromes-and-conversion-disorder. Published March 1, 2008. Accessed February 3, 2015.

11. Lyons-Ruth K, Dutra L, Schuder MR, et al. From infant attachment disorganization to adult dissociation: relational adaptations or traumatic experiences? Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29(1):63-86, viii.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. van der Hart O, Nijenhuis E. Generalized dissociative amnesia: episodic, semantic and procedural memories lost and found. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(5):589-560.

3. Ehrlich S, Pfeiffer E, Salbach H, et al. Factitious disorder in children and adolescents: a retrospective study. Psychosomatics. 2008;45(5):392-398.

4. Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, et al. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271-2276.

5. Kisiel CL, Lyons JS. Dissociation as a mediator of psychopathology among sexually abused children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1034-1039.

6. Worley CB, Feldman MD, Hamilton JC. The case of factitious disorder versus malingering. http://www.psychiatrictimes. com/munchausen-syndrome/case-factitious-disorder-versus-malingering. Published October 30, 2009. Accessed January 27, 2015.

7. Hagglund LA. Challenges in the treatment of factitious disorder: a case study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23(1):58-64.

8. Jenkins KG, Kapur N, Kopelman MD. Retrograde amnesia and malingering. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22(6):601-605.

9. Walker JS. Malingering in children: fibs and faking. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20(3):547-556.

10. Levenson JL. Psychiatric issues in neurology, part 4: amnestic syndromes and conversion disorder. Primary Psychiatry. http://primarypsychiatry.com/psychiatric-issues-in-neurology-part-4-amnestic-syndromes-and-conversion-disorder. Published March 1, 2008. Accessed February 3, 2015.

11. Lyons-Ruth K, Dutra L, Schuder MR, et al. From infant attachment disorganization to adult dissociation: relational adaptations or traumatic experiences? Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29(1):63-86, viii.