User login

A depressed adolescent who won’t eat and reacts slowly

CASE A fainting spell

Ms. A, age 13, is admitted to a pediatric unit after fainting and losing consciousness for 5 minutes in the shower, during which time she was non-responsive. She reports feeling nauseated and having blurry vision before dropping to the floor.

Ms. A reports intentional self-restriction of calories, self-induced vomiting, and other purging behaviors, such as laxative abuse and excessive exercising.

During the mental status examination, Ms. A is lying in bed wearing hospital clothes, legs flexed at the knee, hands on her side, and a fixed gaze at the ceiling with poor eye contact. She is of slender stature and tall, seems slightly older than her stated age, and is poorly groomed.

Throughout the interview, Ms. A has significant psychomotor retardation, reports her mood as tired, and has a blunted affect. She speaks at a low volume and has poverty of speech; she takes deep sighs before answering questions. Her thought process is linear and she cooperates with the interview. She has poor recall, including delayed 3-minute recall and poor sustained attention. Her abstraction capacity is fair and her intellect is average and comparable with her age group. Ms. A is preoccupied that eating will cause weight gain. She denies hallucinations but reports passive death wishes with self-harm by scratching.

What is the differential diagnosis to explain Ms. A’s presentation?

a) syncope

b) seizures

c) dehydration

d) hypotension

HISTORY Preoccupied with weight

Ms. A reports vomiting twice a day, while showering and at night when no one is around, every day for 2 months. She stopped eating and taking in fluids 3 days before admission to the medical unit. Also, she reports restricting her diet to 700 to 1,000 calories a day, skipping lunch at school, and eating minimally at night. Ms. A uses raspberry ketones and green coffee beans, which are advertised to aid weight loss, and laxative pills from her mother’s medicine cabinet once or twice a week when her throat is sore from vomiting. She reports exercising excessively, which includes running, crunches, and lifting weights. She has lost approximately 30 lb in the last 2 months.

Ms. A says she fears gaining weight and feels increased guilt after eating a meal. She said that looking at food induced “anxiety attack” symptoms of increased heart rate, sweaty palms, feeling of choking, nervousness, and shakiness. She adds that she does not want to be “bigger” than her classmates. Her understanding of the consequences of not eating is, “It will get worse, I will shut down and die. I do not fear death, I only fear getting bigger than others.”

She reports that her fixation on avoiding food started when she realized that she was the tallest girl in her class and the only girl in her class running on the track team, after which she quit athletics. She reports that depression symptoms pre-dated her eating disorder symptoms; onset of significant depression likely was precipitated by her grandfather’s death a year earlier, and then exacerbated by the recent death of a family pet.

Ms. A’s depressive symptoms are described as anhedonia (avoiding being outside and not enjoying drawing anymore), decreased energy, tearfulness, sadness, decreased concentration, and passive suicidal thoughts. Her mother is supportive and motivates her daughter to “get better.” Ms. A denies any symptoms of psychosis, other anxiety symptoms, other mood disorder symptoms, substance abuse, or homicidality.

Ms. A’s mother says she felt that, recently, her daughter has been having some difficulty with confused thoughts and significantly delayed responses. However, the mother reports that her daughter always had somewhat delayed responses from what she felt is typical. Her mother adds that Ms. A’s suicidal thoughts have worsened since her daughter started restricting her diet.

Which diagnosis likely accounts for Ms. A’s presentation?

a) major depressive disorder (MDD)

b) eating disorder, not otherwise specified (NOS)

c) anorexia nervosa, purging type

d) catatonia, unspecified

e) anxiety disorder NOS

f) cognitive disorder

g) psychosis NOS

The authors’ observations

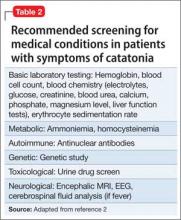

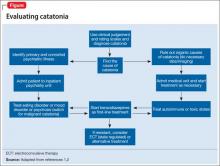

There are many reported causes of catatonia in children and adolescents, including those that are psychiatric, medical, or neurological, as well as drugs (Table 1).1,2 Affective disorders have been associated with catatonia in adults, but has not been widely reported in children and adolescents.1,3 Organic and neurologic causes, such as neurological tumors and cerebral hemorrhage, should be ruled out first because, although rare, they can be fatal (Table 2).2 If the cause of catatonia is not recognized quickly (Figure,1,2) effective treatment could be delayed.4

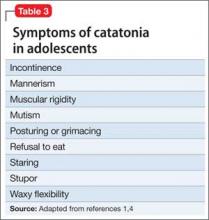

Catatonia involves psychomotor abnormalities, which are listed in Table 3.1,4

Presentation in adults and adolescents is similar.

An eating disorder could be comorbid with another psychiatric disorder, such as MDD, dysthymia, or panic disorder.5 Ms. A’s report of depression before she began restricting food favored a primary diagnosis of MDD. Her depressive symptoms of low appetite or low self-worth could have led to her preoccupation with body image.

There has been evidence that negative self-image and eating disorders are associated, but data are limited and the connection remains unclear.6 Ms. A’s self-esteem was very low. Her fixation on restricting food could have been perpetuated by her self-criticism and by being excluded from her peer group in school. Her weight loss could have brought anxiety symptoms to the forefront because of physiologic changes that accompany extreme weight loss.

The treatment team was concerned about her delayed responses, which could be explained by the catatonic features that reflected the severity of her depression. She had no obvious symptoms of psychosis, but her intrusive thoughts and obsessions with avoiding food did not completely rule out psychosis.

Childhood-onset schizophrenia, although rare, has been associated with catatonia; following up with a catatonia rating scale, such as the Catatonia Rating Scale or the Bush- Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS), would be useful for tracking symptom progress. In Ms. A’s case, her mood disorder was primary, but did not rule out psychosis-like prodromal symptoms.7

Ms. A is diagnosed with MDD, single episode, severe, with catatonic features, and without psychosis, and eating disorder, NOS.

EVALUATION Mostly normal

Ms. A does not have a history of mental illness and was not seeing a psychiatrist or therapist, nor did she have any prior psychiatric admissions. She denies suicide attempts, but reports self-injurious behavior involving scratching her skin, which started during the current mood episode. She has never taken any psychotropic medications. Ms. A lives at home with her biological mother and father and 17-year-old brother. She attends middle school with average grades and has no history of disciplinary actions. She has no history of bullying or teasing, although she did report some previous difficulty with relational aggression toward her peers in the 5th grade. Her mother has a history of anorexia nervosa that began when she was a teenager, but these symptoms are stable and under control. There is additionally a family history of bipolar disorder.

Ms. A has a family history of coronary artery disease and diabetes in the mother and maternal relatives. Her grandfather died from liver cancer. She was allergic to sulfa drugs and was taking a multivitamin and minocycline for acne.

Physical examination reveals some superficial scratches but otherwise was within normal limits. Initial lab results reveal a normal complete blood count and differential. Thyroid-stimulating hormone is 1.29 mIU/L and free T4 is 0.96 mg/dL, both within normal limits. Urinalysis is within normal limits and urine pregnancy test is negative. A comprehensive metabolic panel shows mild elevation in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 60 U/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 92 U/L, respectively. Phosphorus level is within normal limits. Prealbumin level is slightly low at 15.1 mg/dL.

Which treatment plan would you recommend for Ms. A?

a) discharge with outpatient psychiatric treatment

b) recommend medical stabilization with follow-up from the psychosomatic team and then outpatient psychiatric follow-up

c) admit her to the psychiatric acute inpatient hospital with psychiatric outpatient discharge follow-up plan

d) discharge her home with follow-up with her primary care physician

e) recommend follow-up from the psychosomatic team while on medical floor with acute inpatient admission and psychiatric outpatient follow-up at discharge

The authors’ observations

Scarcity of data and reporting of cases of adolescent catatonia limits guidance for diagnosis and treatment.8 There are several rating scales with variability in definition, but that overall provide a guiding tool for detecting catatonia. The Brief Cognitive Rating Scale is considered the most versatile because it is more valid, reliable, and requires less time to complete than other rating scales.9

Ms. A’s symptoms were a combination of depressive symptoms with severity defined by catatonic features, eating disorder with worsening course, anxiety symptoms, and genetic loading of eating disorder in her mother. The challenge of this case was making an accurate diagnosis and treating Ms. A, which required continuous observation following an eating disorder protocol, resolution of her catatonia, resuming a normal diet, and decreasing her suicidality. Retrospectively, her scores on the BFCRS were high on screening items 1 to 14, which measure presence or absence and severity of symptoms.

The best option was to admit Ms. A to an inpatient psychiatric facility after she is cleared medically with outpatient services to follow up.

How would you treat Ms. A’s symptoms?

a) aggressively treat catatonia

b) address her eating disorder

c) work to resolve her depression

The authors’ observations

The challenge was to choose the psychotropic medication that would target her depression, obsessive, rigid thoughts, and catatonia. Administering an antidepressant with an antipsychotic would have relieved her depressive and obsessive symptoms but would not have improved her catatonia. The psychosomatic medicine team recommended starting a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a benzodiazepine to target both the depression and the catatonic symptoms. Ms. A received sertraline, 12.5 mg/d, which was increased to 25 mg/d on the third day. IV lorazepam, 1 mg, 3 times a day, was recommended but the pediatric team prescribed an oral formulation. The hospital’s eating disorder protocol was instituted on the day of admission.

Treatment options for catatonia

Benzodiazepines are the first line of treatment for catatonia and other neuroleptics, specifically antipsychotics, have been considered dangerous.10 Benzodiazepine-resistant catatonia, which is sometimes seen in patients with autism, might respond to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT),11 although in some states it cannot be administered to children age <18.12 Benzodiazepines have shown dramatic improvement within hours, as has ECT.8,13 Additionally, if patients do not respond to a benzodiazepine or ECT, consider other options such as zolpidem, olanzapine,14 or sensory integration system (in adolescents with autism).15

Ms. A did not need ECT or an alternative treatment because she responded well to 3 doses of oral lorazepam. Her amotivation, negativism, and rigidity with prolonged posturing improved. Her psychomotor retardation improved overall, although she reported some dizziness and had some postural hypotension, which was attributed to her eating issues and dehydration.

OUTCOME Feeling motivated

Ms. A is transferred to psychiatric inpatient unit. She tolerates sertraline, which is titrated to 50 mg/d. She is placed on the hospital’s standard eating disorder protocol. She continues to eat well with adequate intake of solids and liquid and exhibits only some anxiety associated with meals. During the course of hospitalization, she attends group therapy and her catatonic symptoms completely resolve. She says she thinks that her thoughts are improving and that she is not longer feeling confused. She reports being motivated to continue to improve her eating disorder symptoms.

The treatment team holds a family session during which family dynamic issues that are stressful to Ms. A are discussed, such as some conflict with her parents as well as some negative interactions between Ms. A and her father. Repeat comprehensive metabolic panel on admission to the inpatient psychiatric hospital reveals persistent elevation of AST at 92 U/L and ALT at 143 U/L. Ms. A is discharged home with follow-up with a psychiatrist and a therapist. The treatment team also recommends that she follow up in a program that specializes in eating disorders.

4-month follow-up. Ms. A returns to inpatient psychiatric hospital after overdose of sertraline and aripiprazole, which were started by an outpatient psychiatrist. She reports severe depressive symptoms because of school stressors. She denies any problems eating and did not show any symptoms of catatonia. In her chart, there is a mention of “cloudy thoughts” and quietness. At this admission, her ALT is 17 U/L and AST is 19 U/L. Sertraline is increased to 150 mg/d and aripiprazole is reduced to 2 mg/d and then later increased to 5 mg/d, after which she is discharged home with an outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

1-year follow-up. Ms. A has been following up with an outpatient psychiatrist and is receiving sertraline, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 2.5 mg/d, and extended-release methylphenidate, 36 mg/d, along with L-methylfolate, multivitamins, and omega-3 fish oil as adjuvants for her depressive symptoms. Ms. A does not show symptoms of an eating disorder or catatonia, and her depression and psychomotor activity have improved, with better overall functionality, after adding the stimulant and adjunctives to the antidepressant.

The authors’ observations

The importance of including catatonia NOS with its various specifiers, such as medical, metabolic, toxic, affective, etc., has been discussed.16,17 In Ms. A’s case, instead of treating the specific symptoms—affective or eating disorder or obsessive quality of thought content, mimicking psychotic-like symptoms—addressing the catatonia initially had a better outcome. More studies related to chronic and acute catatonia in adolescents are needed because of the risk of increased morbidity and premature death.18 Early recognition of catatonia is needed19 because it often is underdiagnosed.20

Eating disorders often become worse over the first 5 years, and close monitoring and assessment is needed for adolescents.21 Also, prodromal psychotic symptoms require follow-up because techniques for early detection and intervention for children and adolescents are still in their infancy.22

Bottom Line

Catatonia in adolescents should be addressed early, when it is treatable and the outcome is favorable. It is important to recognize catatonia in an emergency department or inpatient medical unit setting in a hospital because it is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. The presentation of catatonia is similar in adolescents and adults. Benzodiazepines are first-line treatment for catatonia; consider electroconvulsive therapy if patients do not respond to drug therapy.

Related Resources

• Roberto AJ, Pinnaka S, Mohan A, et al. Adolescent catatonia successfully treated with lorazepam and aripiprazole. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2014;2014:309517. doi: 10.1155/2014/309517.

• Raffin M, Zugaj-Bensaou L, Bodeau N, et al. Treatment use in a prospective naturalistic cohort of children and adolescents with catatonia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(4):441-449.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Minocycline • Minocin

L-methylfolate • Deplin Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Lorazepam • Ativan Sertraline • Zoloft

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta Zolpidem • Ambien, Intermezzo

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Dhossche D, Wilson C, Wachtel LE. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence: implications for the DSM-5. Primary Psychiatry. http://primarypsychiatry.com/catatonia-in-childhood-and-adolescence-implications-for-the-dsm-5. Published May 21, 2013. Accessed July 2, 2015.

2. Lahutte B, Cornic F, Bonnot O, et al. Multidisciplinary approach of organic catatonia in children and adolescents may improve treatment decision making. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):1393-1398.

3. Brake JA, Abidi S. A case of adolescent catatonia. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):138-140.

4. Consoli A, Raffin M, Laurent C, et al. Medical and developmental risk factors of catatonia in children and adolescents: a prospective case-control study. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):151-158.

5. Zaider TI, Johnson JG, Cockell SJ. Psychiatric comorbidity associated with eating disorder symptomatology among adolescents in the community. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(1):58-67.

6. Forsén Mantilla E, Bergsten K, Birgegård A. Self-image and eating disorder symptoms in normal and clinical adolescents. Eat Behav. 2014;15(1):125-131.

7. Bonnot O, Tanguy ML, Consoli A, et al. Does catatonia influence the phenomenology of childhood onset schizophrenia beyond motor symptoms? Psychiatry Res. 2008;158(3):356-362.

8. Singh LK, Praharaj SK. Immediate response to lorazepam in a patient with 17 years of chronic catatonia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(3):E47-E48.

9. Sienaert P, Rooseleer J, De Fruyt J. Measuring catatonia: a systematic review of rating scales. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):1-9.

10. Cottencin O, Warembourg F, de Chouly de Lenclave MB, et al. Catatonia and consultation-liaison psychiatry study of 12 cases. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(6):1170-1176.

11. Wachtel LE, Hermida A, Dhossche DM. Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in autistic catatonia: a case series review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):581-587.

12. Wachtel LE, Dhossche DM, Kellner CH. When is electroconvulsive therapy appropriate for children and adolescents? Med Hypotheses. 2011;76(3):395-399.

13. Takaoka K, Takata T. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57(2):129-137.

14. Ceylan MF, Kul M, Kultur SE, et al. Major depression with catatonic features in a child remitted with olanzapine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(3):225-227.

15. Consoli A, Gheorghiev C, Jutard C, et al. Lorazepam, fluoxetine and packing therapy in an adolescent with pervasive developmental disorder and catatonia. J Physiol Paris. 2010;104(6):309-314.

16. Dhossche D, Cohen D, Ghaziuddin N, et al. The study of pediatric catatonia supports a home of its own for catatonia in DSM-5. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75(6):558-560.

17. Taylor MA, Fink M. Catatonia in psychiatric classification: a home of its own. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1233-1241.

18. Cornic F, Consoli A, Tanguy ML, et al. Association of adolescent catatonia with increased mortality and morbidity: evidence from a prospective follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):233-240.

19. Quigley J, Lommel KM, Coffey B. Catatonia in an adolescent with Asperger’s disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):93-96.

20. Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):33-38.

21. Ackard DM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Stability of eating disorder diagnostic classifications in adolescents: five-year longitudinal findings from a population-based study. Eat Disord. 2011;19(4):308-322.

22. Schimmelmann BG, Schultze-Lutter F. Early detection and intervention of psychosis in children and adolescents: urgent need for studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(5):239-241.

CASE A fainting spell

Ms. A, age 13, is admitted to a pediatric unit after fainting and losing consciousness for 5 minutes in the shower, during which time she was non-responsive. She reports feeling nauseated and having blurry vision before dropping to the floor.

Ms. A reports intentional self-restriction of calories, self-induced vomiting, and other purging behaviors, such as laxative abuse and excessive exercising.

During the mental status examination, Ms. A is lying in bed wearing hospital clothes, legs flexed at the knee, hands on her side, and a fixed gaze at the ceiling with poor eye contact. She is of slender stature and tall, seems slightly older than her stated age, and is poorly groomed.

Throughout the interview, Ms. A has significant psychomotor retardation, reports her mood as tired, and has a blunted affect. She speaks at a low volume and has poverty of speech; she takes deep sighs before answering questions. Her thought process is linear and she cooperates with the interview. She has poor recall, including delayed 3-minute recall and poor sustained attention. Her abstraction capacity is fair and her intellect is average and comparable with her age group. Ms. A is preoccupied that eating will cause weight gain. She denies hallucinations but reports passive death wishes with self-harm by scratching.

What is the differential diagnosis to explain Ms. A’s presentation?

a) syncope

b) seizures

c) dehydration

d) hypotension

HISTORY Preoccupied with weight

Ms. A reports vomiting twice a day, while showering and at night when no one is around, every day for 2 months. She stopped eating and taking in fluids 3 days before admission to the medical unit. Also, she reports restricting her diet to 700 to 1,000 calories a day, skipping lunch at school, and eating minimally at night. Ms. A uses raspberry ketones and green coffee beans, which are advertised to aid weight loss, and laxative pills from her mother’s medicine cabinet once or twice a week when her throat is sore from vomiting. She reports exercising excessively, which includes running, crunches, and lifting weights. She has lost approximately 30 lb in the last 2 months.

Ms. A says she fears gaining weight and feels increased guilt after eating a meal. She said that looking at food induced “anxiety attack” symptoms of increased heart rate, sweaty palms, feeling of choking, nervousness, and shakiness. She adds that she does not want to be “bigger” than her classmates. Her understanding of the consequences of not eating is, “It will get worse, I will shut down and die. I do not fear death, I only fear getting bigger than others.”

She reports that her fixation on avoiding food started when she realized that she was the tallest girl in her class and the only girl in her class running on the track team, after which she quit athletics. She reports that depression symptoms pre-dated her eating disorder symptoms; onset of significant depression likely was precipitated by her grandfather’s death a year earlier, and then exacerbated by the recent death of a family pet.

Ms. A’s depressive symptoms are described as anhedonia (avoiding being outside and not enjoying drawing anymore), decreased energy, tearfulness, sadness, decreased concentration, and passive suicidal thoughts. Her mother is supportive and motivates her daughter to “get better.” Ms. A denies any symptoms of psychosis, other anxiety symptoms, other mood disorder symptoms, substance abuse, or homicidality.

Ms. A’s mother says she felt that, recently, her daughter has been having some difficulty with confused thoughts and significantly delayed responses. However, the mother reports that her daughter always had somewhat delayed responses from what she felt is typical. Her mother adds that Ms. A’s suicidal thoughts have worsened since her daughter started restricting her diet.

Which diagnosis likely accounts for Ms. A’s presentation?

a) major depressive disorder (MDD)

b) eating disorder, not otherwise specified (NOS)

c) anorexia nervosa, purging type

d) catatonia, unspecified

e) anxiety disorder NOS

f) cognitive disorder

g) psychosis NOS

The authors’ observations

There are many reported causes of catatonia in children and adolescents, including those that are psychiatric, medical, or neurological, as well as drugs (Table 1).1,2 Affective disorders have been associated with catatonia in adults, but has not been widely reported in children and adolescents.1,3 Organic and neurologic causes, such as neurological tumors and cerebral hemorrhage, should be ruled out first because, although rare, they can be fatal (Table 2).2 If the cause of catatonia is not recognized quickly (Figure,1,2) effective treatment could be delayed.4

Catatonia involves psychomotor abnormalities, which are listed in Table 3.1,4

Presentation in adults and adolescents is similar.

An eating disorder could be comorbid with another psychiatric disorder, such as MDD, dysthymia, or panic disorder.5 Ms. A’s report of depression before she began restricting food favored a primary diagnosis of MDD. Her depressive symptoms of low appetite or low self-worth could have led to her preoccupation with body image.

There has been evidence that negative self-image and eating disorders are associated, but data are limited and the connection remains unclear.6 Ms. A’s self-esteem was very low. Her fixation on restricting food could have been perpetuated by her self-criticism and by being excluded from her peer group in school. Her weight loss could have brought anxiety symptoms to the forefront because of physiologic changes that accompany extreme weight loss.

The treatment team was concerned about her delayed responses, which could be explained by the catatonic features that reflected the severity of her depression. She had no obvious symptoms of psychosis, but her intrusive thoughts and obsessions with avoiding food did not completely rule out psychosis.

Childhood-onset schizophrenia, although rare, has been associated with catatonia; following up with a catatonia rating scale, such as the Catatonia Rating Scale or the Bush- Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS), would be useful for tracking symptom progress. In Ms. A’s case, her mood disorder was primary, but did not rule out psychosis-like prodromal symptoms.7

Ms. A is diagnosed with MDD, single episode, severe, with catatonic features, and without psychosis, and eating disorder, NOS.

EVALUATION Mostly normal

Ms. A does not have a history of mental illness and was not seeing a psychiatrist or therapist, nor did she have any prior psychiatric admissions. She denies suicide attempts, but reports self-injurious behavior involving scratching her skin, which started during the current mood episode. She has never taken any psychotropic medications. Ms. A lives at home with her biological mother and father and 17-year-old brother. She attends middle school with average grades and has no history of disciplinary actions. She has no history of bullying or teasing, although she did report some previous difficulty with relational aggression toward her peers in the 5th grade. Her mother has a history of anorexia nervosa that began when she was a teenager, but these symptoms are stable and under control. There is additionally a family history of bipolar disorder.

Ms. A has a family history of coronary artery disease and diabetes in the mother and maternal relatives. Her grandfather died from liver cancer. She was allergic to sulfa drugs and was taking a multivitamin and minocycline for acne.

Physical examination reveals some superficial scratches but otherwise was within normal limits. Initial lab results reveal a normal complete blood count and differential. Thyroid-stimulating hormone is 1.29 mIU/L and free T4 is 0.96 mg/dL, both within normal limits. Urinalysis is within normal limits and urine pregnancy test is negative. A comprehensive metabolic panel shows mild elevation in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 60 U/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 92 U/L, respectively. Phosphorus level is within normal limits. Prealbumin level is slightly low at 15.1 mg/dL.

Which treatment plan would you recommend for Ms. A?

a) discharge with outpatient psychiatric treatment

b) recommend medical stabilization with follow-up from the psychosomatic team and then outpatient psychiatric follow-up

c) admit her to the psychiatric acute inpatient hospital with psychiatric outpatient discharge follow-up plan

d) discharge her home with follow-up with her primary care physician

e) recommend follow-up from the psychosomatic team while on medical floor with acute inpatient admission and psychiatric outpatient follow-up at discharge

The authors’ observations

Scarcity of data and reporting of cases of adolescent catatonia limits guidance for diagnosis and treatment.8 There are several rating scales with variability in definition, but that overall provide a guiding tool for detecting catatonia. The Brief Cognitive Rating Scale is considered the most versatile because it is more valid, reliable, and requires less time to complete than other rating scales.9

Ms. A’s symptoms were a combination of depressive symptoms with severity defined by catatonic features, eating disorder with worsening course, anxiety symptoms, and genetic loading of eating disorder in her mother. The challenge of this case was making an accurate diagnosis and treating Ms. A, which required continuous observation following an eating disorder protocol, resolution of her catatonia, resuming a normal diet, and decreasing her suicidality. Retrospectively, her scores on the BFCRS were high on screening items 1 to 14, which measure presence or absence and severity of symptoms.

The best option was to admit Ms. A to an inpatient psychiatric facility after she is cleared medically with outpatient services to follow up.

How would you treat Ms. A’s symptoms?

a) aggressively treat catatonia

b) address her eating disorder

c) work to resolve her depression

The authors’ observations

The challenge was to choose the psychotropic medication that would target her depression, obsessive, rigid thoughts, and catatonia. Administering an antidepressant with an antipsychotic would have relieved her depressive and obsessive symptoms but would not have improved her catatonia. The psychosomatic medicine team recommended starting a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a benzodiazepine to target both the depression and the catatonic symptoms. Ms. A received sertraline, 12.5 mg/d, which was increased to 25 mg/d on the third day. IV lorazepam, 1 mg, 3 times a day, was recommended but the pediatric team prescribed an oral formulation. The hospital’s eating disorder protocol was instituted on the day of admission.

Treatment options for catatonia

Benzodiazepines are the first line of treatment for catatonia and other neuroleptics, specifically antipsychotics, have been considered dangerous.10 Benzodiazepine-resistant catatonia, which is sometimes seen in patients with autism, might respond to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT),11 although in some states it cannot be administered to children age <18.12 Benzodiazepines have shown dramatic improvement within hours, as has ECT.8,13 Additionally, if patients do not respond to a benzodiazepine or ECT, consider other options such as zolpidem, olanzapine,14 or sensory integration system (in adolescents with autism).15

Ms. A did not need ECT or an alternative treatment because she responded well to 3 doses of oral lorazepam. Her amotivation, negativism, and rigidity with prolonged posturing improved. Her psychomotor retardation improved overall, although she reported some dizziness and had some postural hypotension, which was attributed to her eating issues and dehydration.

OUTCOME Feeling motivated

Ms. A is transferred to psychiatric inpatient unit. She tolerates sertraline, which is titrated to 50 mg/d. She is placed on the hospital’s standard eating disorder protocol. She continues to eat well with adequate intake of solids and liquid and exhibits only some anxiety associated with meals. During the course of hospitalization, she attends group therapy and her catatonic symptoms completely resolve. She says she thinks that her thoughts are improving and that she is not longer feeling confused. She reports being motivated to continue to improve her eating disorder symptoms.

The treatment team holds a family session during which family dynamic issues that are stressful to Ms. A are discussed, such as some conflict with her parents as well as some negative interactions between Ms. A and her father. Repeat comprehensive metabolic panel on admission to the inpatient psychiatric hospital reveals persistent elevation of AST at 92 U/L and ALT at 143 U/L. Ms. A is discharged home with follow-up with a psychiatrist and a therapist. The treatment team also recommends that she follow up in a program that specializes in eating disorders.

4-month follow-up. Ms. A returns to inpatient psychiatric hospital after overdose of sertraline and aripiprazole, which were started by an outpatient psychiatrist. She reports severe depressive symptoms because of school stressors. She denies any problems eating and did not show any symptoms of catatonia. In her chart, there is a mention of “cloudy thoughts” and quietness. At this admission, her ALT is 17 U/L and AST is 19 U/L. Sertraline is increased to 150 mg/d and aripiprazole is reduced to 2 mg/d and then later increased to 5 mg/d, after which she is discharged home with an outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

1-year follow-up. Ms. A has been following up with an outpatient psychiatrist and is receiving sertraline, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 2.5 mg/d, and extended-release methylphenidate, 36 mg/d, along with L-methylfolate, multivitamins, and omega-3 fish oil as adjuvants for her depressive symptoms. Ms. A does not show symptoms of an eating disorder or catatonia, and her depression and psychomotor activity have improved, with better overall functionality, after adding the stimulant and adjunctives to the antidepressant.

The authors’ observations

The importance of including catatonia NOS with its various specifiers, such as medical, metabolic, toxic, affective, etc., has been discussed.16,17 In Ms. A’s case, instead of treating the specific symptoms—affective or eating disorder or obsessive quality of thought content, mimicking psychotic-like symptoms—addressing the catatonia initially had a better outcome. More studies related to chronic and acute catatonia in adolescents are needed because of the risk of increased morbidity and premature death.18 Early recognition of catatonia is needed19 because it often is underdiagnosed.20

Eating disorders often become worse over the first 5 years, and close monitoring and assessment is needed for adolescents.21 Also, prodromal psychotic symptoms require follow-up because techniques for early detection and intervention for children and adolescents are still in their infancy.22

Bottom Line

Catatonia in adolescents should be addressed early, when it is treatable and the outcome is favorable. It is important to recognize catatonia in an emergency department or inpatient medical unit setting in a hospital because it is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. The presentation of catatonia is similar in adolescents and adults. Benzodiazepines are first-line treatment for catatonia; consider electroconvulsive therapy if patients do not respond to drug therapy.

Related Resources

• Roberto AJ, Pinnaka S, Mohan A, et al. Adolescent catatonia successfully treated with lorazepam and aripiprazole. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2014;2014:309517. doi: 10.1155/2014/309517.

• Raffin M, Zugaj-Bensaou L, Bodeau N, et al. Treatment use in a prospective naturalistic cohort of children and adolescents with catatonia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(4):441-449.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Minocycline • Minocin

L-methylfolate • Deplin Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Lorazepam • Ativan Sertraline • Zoloft

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta Zolpidem • Ambien, Intermezzo

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE A fainting spell

Ms. A, age 13, is admitted to a pediatric unit after fainting and losing consciousness for 5 minutes in the shower, during which time she was non-responsive. She reports feeling nauseated and having blurry vision before dropping to the floor.

Ms. A reports intentional self-restriction of calories, self-induced vomiting, and other purging behaviors, such as laxative abuse and excessive exercising.

During the mental status examination, Ms. A is lying in bed wearing hospital clothes, legs flexed at the knee, hands on her side, and a fixed gaze at the ceiling with poor eye contact. She is of slender stature and tall, seems slightly older than her stated age, and is poorly groomed.

Throughout the interview, Ms. A has significant psychomotor retardation, reports her mood as tired, and has a blunted affect. She speaks at a low volume and has poverty of speech; she takes deep sighs before answering questions. Her thought process is linear and she cooperates with the interview. She has poor recall, including delayed 3-minute recall and poor sustained attention. Her abstraction capacity is fair and her intellect is average and comparable with her age group. Ms. A is preoccupied that eating will cause weight gain. She denies hallucinations but reports passive death wishes with self-harm by scratching.

What is the differential diagnosis to explain Ms. A’s presentation?

a) syncope

b) seizures

c) dehydration

d) hypotension

HISTORY Preoccupied with weight

Ms. A reports vomiting twice a day, while showering and at night when no one is around, every day for 2 months. She stopped eating and taking in fluids 3 days before admission to the medical unit. Also, she reports restricting her diet to 700 to 1,000 calories a day, skipping lunch at school, and eating minimally at night. Ms. A uses raspberry ketones and green coffee beans, which are advertised to aid weight loss, and laxative pills from her mother’s medicine cabinet once or twice a week when her throat is sore from vomiting. She reports exercising excessively, which includes running, crunches, and lifting weights. She has lost approximately 30 lb in the last 2 months.

Ms. A says she fears gaining weight and feels increased guilt after eating a meal. She said that looking at food induced “anxiety attack” symptoms of increased heart rate, sweaty palms, feeling of choking, nervousness, and shakiness. She adds that she does not want to be “bigger” than her classmates. Her understanding of the consequences of not eating is, “It will get worse, I will shut down and die. I do not fear death, I only fear getting bigger than others.”

She reports that her fixation on avoiding food started when she realized that she was the tallest girl in her class and the only girl in her class running on the track team, after which she quit athletics. She reports that depression symptoms pre-dated her eating disorder symptoms; onset of significant depression likely was precipitated by her grandfather’s death a year earlier, and then exacerbated by the recent death of a family pet.

Ms. A’s depressive symptoms are described as anhedonia (avoiding being outside and not enjoying drawing anymore), decreased energy, tearfulness, sadness, decreased concentration, and passive suicidal thoughts. Her mother is supportive and motivates her daughter to “get better.” Ms. A denies any symptoms of psychosis, other anxiety symptoms, other mood disorder symptoms, substance abuse, or homicidality.

Ms. A’s mother says she felt that, recently, her daughter has been having some difficulty with confused thoughts and significantly delayed responses. However, the mother reports that her daughter always had somewhat delayed responses from what she felt is typical. Her mother adds that Ms. A’s suicidal thoughts have worsened since her daughter started restricting her diet.

Which diagnosis likely accounts for Ms. A’s presentation?

a) major depressive disorder (MDD)

b) eating disorder, not otherwise specified (NOS)

c) anorexia nervosa, purging type

d) catatonia, unspecified

e) anxiety disorder NOS

f) cognitive disorder

g) psychosis NOS

The authors’ observations

There are many reported causes of catatonia in children and adolescents, including those that are psychiatric, medical, or neurological, as well as drugs (Table 1).1,2 Affective disorders have been associated with catatonia in adults, but has not been widely reported in children and adolescents.1,3 Organic and neurologic causes, such as neurological tumors and cerebral hemorrhage, should be ruled out first because, although rare, they can be fatal (Table 2).2 If the cause of catatonia is not recognized quickly (Figure,1,2) effective treatment could be delayed.4

Catatonia involves psychomotor abnormalities, which are listed in Table 3.1,4

Presentation in adults and adolescents is similar.

An eating disorder could be comorbid with another psychiatric disorder, such as MDD, dysthymia, or panic disorder.5 Ms. A’s report of depression before she began restricting food favored a primary diagnosis of MDD. Her depressive symptoms of low appetite or low self-worth could have led to her preoccupation with body image.

There has been evidence that negative self-image and eating disorders are associated, but data are limited and the connection remains unclear.6 Ms. A’s self-esteem was very low. Her fixation on restricting food could have been perpetuated by her self-criticism and by being excluded from her peer group in school. Her weight loss could have brought anxiety symptoms to the forefront because of physiologic changes that accompany extreme weight loss.

The treatment team was concerned about her delayed responses, which could be explained by the catatonic features that reflected the severity of her depression. She had no obvious symptoms of psychosis, but her intrusive thoughts and obsessions with avoiding food did not completely rule out psychosis.

Childhood-onset schizophrenia, although rare, has been associated with catatonia; following up with a catatonia rating scale, such as the Catatonia Rating Scale or the Bush- Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS), would be useful for tracking symptom progress. In Ms. A’s case, her mood disorder was primary, but did not rule out psychosis-like prodromal symptoms.7

Ms. A is diagnosed with MDD, single episode, severe, with catatonic features, and without psychosis, and eating disorder, NOS.

EVALUATION Mostly normal

Ms. A does not have a history of mental illness and was not seeing a psychiatrist or therapist, nor did she have any prior psychiatric admissions. She denies suicide attempts, but reports self-injurious behavior involving scratching her skin, which started during the current mood episode. She has never taken any psychotropic medications. Ms. A lives at home with her biological mother and father and 17-year-old brother. She attends middle school with average grades and has no history of disciplinary actions. She has no history of bullying or teasing, although she did report some previous difficulty with relational aggression toward her peers in the 5th grade. Her mother has a history of anorexia nervosa that began when she was a teenager, but these symptoms are stable and under control. There is additionally a family history of bipolar disorder.

Ms. A has a family history of coronary artery disease and diabetes in the mother and maternal relatives. Her grandfather died from liver cancer. She was allergic to sulfa drugs and was taking a multivitamin and minocycline for acne.

Physical examination reveals some superficial scratches but otherwise was within normal limits. Initial lab results reveal a normal complete blood count and differential. Thyroid-stimulating hormone is 1.29 mIU/L and free T4 is 0.96 mg/dL, both within normal limits. Urinalysis is within normal limits and urine pregnancy test is negative. A comprehensive metabolic panel shows mild elevation in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 60 U/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 92 U/L, respectively. Phosphorus level is within normal limits. Prealbumin level is slightly low at 15.1 mg/dL.

Which treatment plan would you recommend for Ms. A?

a) discharge with outpatient psychiatric treatment

b) recommend medical stabilization with follow-up from the psychosomatic team and then outpatient psychiatric follow-up

c) admit her to the psychiatric acute inpatient hospital with psychiatric outpatient discharge follow-up plan

d) discharge her home with follow-up with her primary care physician

e) recommend follow-up from the psychosomatic team while on medical floor with acute inpatient admission and psychiatric outpatient follow-up at discharge

The authors’ observations

Scarcity of data and reporting of cases of adolescent catatonia limits guidance for diagnosis and treatment.8 There are several rating scales with variability in definition, but that overall provide a guiding tool for detecting catatonia. The Brief Cognitive Rating Scale is considered the most versatile because it is more valid, reliable, and requires less time to complete than other rating scales.9

Ms. A’s symptoms were a combination of depressive symptoms with severity defined by catatonic features, eating disorder with worsening course, anxiety symptoms, and genetic loading of eating disorder in her mother. The challenge of this case was making an accurate diagnosis and treating Ms. A, which required continuous observation following an eating disorder protocol, resolution of her catatonia, resuming a normal diet, and decreasing her suicidality. Retrospectively, her scores on the BFCRS were high on screening items 1 to 14, which measure presence or absence and severity of symptoms.

The best option was to admit Ms. A to an inpatient psychiatric facility after she is cleared medically with outpatient services to follow up.

How would you treat Ms. A’s symptoms?

a) aggressively treat catatonia

b) address her eating disorder

c) work to resolve her depression

The authors’ observations

The challenge was to choose the psychotropic medication that would target her depression, obsessive, rigid thoughts, and catatonia. Administering an antidepressant with an antipsychotic would have relieved her depressive and obsessive symptoms but would not have improved her catatonia. The psychosomatic medicine team recommended starting a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a benzodiazepine to target both the depression and the catatonic symptoms. Ms. A received sertraline, 12.5 mg/d, which was increased to 25 mg/d on the third day. IV lorazepam, 1 mg, 3 times a day, was recommended but the pediatric team prescribed an oral formulation. The hospital’s eating disorder protocol was instituted on the day of admission.

Treatment options for catatonia

Benzodiazepines are the first line of treatment for catatonia and other neuroleptics, specifically antipsychotics, have been considered dangerous.10 Benzodiazepine-resistant catatonia, which is sometimes seen in patients with autism, might respond to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT),11 although in some states it cannot be administered to children age <18.12 Benzodiazepines have shown dramatic improvement within hours, as has ECT.8,13 Additionally, if patients do not respond to a benzodiazepine or ECT, consider other options such as zolpidem, olanzapine,14 or sensory integration system (in adolescents with autism).15

Ms. A did not need ECT or an alternative treatment because she responded well to 3 doses of oral lorazepam. Her amotivation, negativism, and rigidity with prolonged posturing improved. Her psychomotor retardation improved overall, although she reported some dizziness and had some postural hypotension, which was attributed to her eating issues and dehydration.

OUTCOME Feeling motivated

Ms. A is transferred to psychiatric inpatient unit. She tolerates sertraline, which is titrated to 50 mg/d. She is placed on the hospital’s standard eating disorder protocol. She continues to eat well with adequate intake of solids and liquid and exhibits only some anxiety associated with meals. During the course of hospitalization, she attends group therapy and her catatonic symptoms completely resolve. She says she thinks that her thoughts are improving and that she is not longer feeling confused. She reports being motivated to continue to improve her eating disorder symptoms.

The treatment team holds a family session during which family dynamic issues that are stressful to Ms. A are discussed, such as some conflict with her parents as well as some negative interactions between Ms. A and her father. Repeat comprehensive metabolic panel on admission to the inpatient psychiatric hospital reveals persistent elevation of AST at 92 U/L and ALT at 143 U/L. Ms. A is discharged home with follow-up with a psychiatrist and a therapist. The treatment team also recommends that she follow up in a program that specializes in eating disorders.

4-month follow-up. Ms. A returns to inpatient psychiatric hospital after overdose of sertraline and aripiprazole, which were started by an outpatient psychiatrist. She reports severe depressive symptoms because of school stressors. She denies any problems eating and did not show any symptoms of catatonia. In her chart, there is a mention of “cloudy thoughts” and quietness. At this admission, her ALT is 17 U/L and AST is 19 U/L. Sertraline is increased to 150 mg/d and aripiprazole is reduced to 2 mg/d and then later increased to 5 mg/d, after which she is discharged home with an outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

1-year follow-up. Ms. A has been following up with an outpatient psychiatrist and is receiving sertraline, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 2.5 mg/d, and extended-release methylphenidate, 36 mg/d, along with L-methylfolate, multivitamins, and omega-3 fish oil as adjuvants for her depressive symptoms. Ms. A does not show symptoms of an eating disorder or catatonia, and her depression and psychomotor activity have improved, with better overall functionality, after adding the stimulant and adjunctives to the antidepressant.

The authors’ observations

The importance of including catatonia NOS with its various specifiers, such as medical, metabolic, toxic, affective, etc., has been discussed.16,17 In Ms. A’s case, instead of treating the specific symptoms—affective or eating disorder or obsessive quality of thought content, mimicking psychotic-like symptoms—addressing the catatonia initially had a better outcome. More studies related to chronic and acute catatonia in adolescents are needed because of the risk of increased morbidity and premature death.18 Early recognition of catatonia is needed19 because it often is underdiagnosed.20

Eating disorders often become worse over the first 5 years, and close monitoring and assessment is needed for adolescents.21 Also, prodromal psychotic symptoms require follow-up because techniques for early detection and intervention for children and adolescents are still in their infancy.22

Bottom Line

Catatonia in adolescents should be addressed early, when it is treatable and the outcome is favorable. It is important to recognize catatonia in an emergency department or inpatient medical unit setting in a hospital because it is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. The presentation of catatonia is similar in adolescents and adults. Benzodiazepines are first-line treatment for catatonia; consider electroconvulsive therapy if patients do not respond to drug therapy.

Related Resources

• Roberto AJ, Pinnaka S, Mohan A, et al. Adolescent catatonia successfully treated with lorazepam and aripiprazole. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2014;2014:309517. doi: 10.1155/2014/309517.

• Raffin M, Zugaj-Bensaou L, Bodeau N, et al. Treatment use in a prospective naturalistic cohort of children and adolescents with catatonia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(4):441-449.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Minocycline • Minocin

L-methylfolate • Deplin Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Lorazepam • Ativan Sertraline • Zoloft

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta Zolpidem • Ambien, Intermezzo

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Dhossche D, Wilson C, Wachtel LE. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence: implications for the DSM-5. Primary Psychiatry. http://primarypsychiatry.com/catatonia-in-childhood-and-adolescence-implications-for-the-dsm-5. Published May 21, 2013. Accessed July 2, 2015.

2. Lahutte B, Cornic F, Bonnot O, et al. Multidisciplinary approach of organic catatonia in children and adolescents may improve treatment decision making. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):1393-1398.

3. Brake JA, Abidi S. A case of adolescent catatonia. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):138-140.

4. Consoli A, Raffin M, Laurent C, et al. Medical and developmental risk factors of catatonia in children and adolescents: a prospective case-control study. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):151-158.

5. Zaider TI, Johnson JG, Cockell SJ. Psychiatric comorbidity associated with eating disorder symptomatology among adolescents in the community. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(1):58-67.

6. Forsén Mantilla E, Bergsten K, Birgegård A. Self-image and eating disorder symptoms in normal and clinical adolescents. Eat Behav. 2014;15(1):125-131.

7. Bonnot O, Tanguy ML, Consoli A, et al. Does catatonia influence the phenomenology of childhood onset schizophrenia beyond motor symptoms? Psychiatry Res. 2008;158(3):356-362.

8. Singh LK, Praharaj SK. Immediate response to lorazepam in a patient with 17 years of chronic catatonia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(3):E47-E48.

9. Sienaert P, Rooseleer J, De Fruyt J. Measuring catatonia: a systematic review of rating scales. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):1-9.

10. Cottencin O, Warembourg F, de Chouly de Lenclave MB, et al. Catatonia and consultation-liaison psychiatry study of 12 cases. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(6):1170-1176.

11. Wachtel LE, Hermida A, Dhossche DM. Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in autistic catatonia: a case series review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):581-587.

12. Wachtel LE, Dhossche DM, Kellner CH. When is electroconvulsive therapy appropriate for children and adolescents? Med Hypotheses. 2011;76(3):395-399.

13. Takaoka K, Takata T. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57(2):129-137.

14. Ceylan MF, Kul M, Kultur SE, et al. Major depression with catatonic features in a child remitted with olanzapine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(3):225-227.

15. Consoli A, Gheorghiev C, Jutard C, et al. Lorazepam, fluoxetine and packing therapy in an adolescent with pervasive developmental disorder and catatonia. J Physiol Paris. 2010;104(6):309-314.

16. Dhossche D, Cohen D, Ghaziuddin N, et al. The study of pediatric catatonia supports a home of its own for catatonia in DSM-5. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75(6):558-560.

17. Taylor MA, Fink M. Catatonia in psychiatric classification: a home of its own. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1233-1241.

18. Cornic F, Consoli A, Tanguy ML, et al. Association of adolescent catatonia with increased mortality and morbidity: evidence from a prospective follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):233-240.

19. Quigley J, Lommel KM, Coffey B. Catatonia in an adolescent with Asperger’s disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):93-96.

20. Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):33-38.

21. Ackard DM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Stability of eating disorder diagnostic classifications in adolescents: five-year longitudinal findings from a population-based study. Eat Disord. 2011;19(4):308-322.

22. Schimmelmann BG, Schultze-Lutter F. Early detection and intervention of psychosis in children and adolescents: urgent need for studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(5):239-241.

1. Dhossche D, Wilson C, Wachtel LE. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence: implications for the DSM-5. Primary Psychiatry. http://primarypsychiatry.com/catatonia-in-childhood-and-adolescence-implications-for-the-dsm-5. Published May 21, 2013. Accessed July 2, 2015.

2. Lahutte B, Cornic F, Bonnot O, et al. Multidisciplinary approach of organic catatonia in children and adolescents may improve treatment decision making. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):1393-1398.

3. Brake JA, Abidi S. A case of adolescent catatonia. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):138-140.

4. Consoli A, Raffin M, Laurent C, et al. Medical and developmental risk factors of catatonia in children and adolescents: a prospective case-control study. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):151-158.

5. Zaider TI, Johnson JG, Cockell SJ. Psychiatric comorbidity associated with eating disorder symptomatology among adolescents in the community. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(1):58-67.

6. Forsén Mantilla E, Bergsten K, Birgegård A. Self-image and eating disorder symptoms in normal and clinical adolescents. Eat Behav. 2014;15(1):125-131.

7. Bonnot O, Tanguy ML, Consoli A, et al. Does catatonia influence the phenomenology of childhood onset schizophrenia beyond motor symptoms? Psychiatry Res. 2008;158(3):356-362.

8. Singh LK, Praharaj SK. Immediate response to lorazepam in a patient with 17 years of chronic catatonia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(3):E47-E48.

9. Sienaert P, Rooseleer J, De Fruyt J. Measuring catatonia: a systematic review of rating scales. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):1-9.

10. Cottencin O, Warembourg F, de Chouly de Lenclave MB, et al. Catatonia and consultation-liaison psychiatry study of 12 cases. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(6):1170-1176.

11. Wachtel LE, Hermida A, Dhossche DM. Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in autistic catatonia: a case series review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):581-587.

12. Wachtel LE, Dhossche DM, Kellner CH. When is electroconvulsive therapy appropriate for children and adolescents? Med Hypotheses. 2011;76(3):395-399.

13. Takaoka K, Takata T. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57(2):129-137.

14. Ceylan MF, Kul M, Kultur SE, et al. Major depression with catatonic features in a child remitted with olanzapine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(3):225-227.

15. Consoli A, Gheorghiev C, Jutard C, et al. Lorazepam, fluoxetine and packing therapy in an adolescent with pervasive developmental disorder and catatonia. J Physiol Paris. 2010;104(6):309-314.

16. Dhossche D, Cohen D, Ghaziuddin N, et al. The study of pediatric catatonia supports a home of its own for catatonia in DSM-5. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75(6):558-560.

17. Taylor MA, Fink M. Catatonia in psychiatric classification: a home of its own. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1233-1241.

18. Cornic F, Consoli A, Tanguy ML, et al. Association of adolescent catatonia with increased mortality and morbidity: evidence from a prospective follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):233-240.

19. Quigley J, Lommel KM, Coffey B. Catatonia in an adolescent with Asperger’s disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):93-96.

20. Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):33-38.

21. Ackard DM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Stability of eating disorder diagnostic classifications in adolescents: five-year longitudinal findings from a population-based study. Eat Disord. 2011;19(4):308-322.

22. Schimmelmann BG, Schultze-Lutter F. Early detection and intervention of psychosis in children and adolescents: urgent need for studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(5):239-241.

A teen with seizures, amnesia, and troubled family dynamics

CASE Seizures, amnesia

Ms. A, age 13, who has a history of seizures, presents to the emergency department (ED) with sudden onset of memory loss. Her family reports that she had been spending a normal evening at home with family and friends. After going to the bathroom, Ms. A became acutely confused and extremely upset, had slurred speech, and did not recognize anyone in the room except her mother.

Initial neurologic examination in the ED reports that Ms. A does not remember recent or remote past events. Her family denies any recent stressors.

Vital signs are within normal range. She has mild muscle soreness and gait instability, which is attributed to a presumed postictal phase. Her medication regimen includes: levetiracetam, 500 mg, 3 times a day; valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d; and oxcarbazepine, 2,400 mg/d, for seizure management.

Complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel are within normal limits. Pregnancy test is negative. Urine toxicology report is negative. Serum valproic acid level is 71 μg/mL; oxcarbazepine level, <2 μg/mL; ammonia level, 71 μg/dL (reference range, 15 to 45 μg/dL). Other than the aforementioned deficits, she is neurologically intact. The team thinks that her symptoms are part of a postictal phase of an unwitnessed seizure.

Ms. A is admitted to the inpatient medical unit for further work up. Along with the memory loss and seizures, she reports visual hallucinations.

What could be causing Ms. A’s amnesia?

a) a seizure disorder

b) malingering

c) posttraumatic stress disorder

d) traumatic brain injury

HISTORY Repeat ED visits

Ms. A’s mother reports that 3 years ago her daughter was treated for tics with quetiapine and aripiprazole, prescribed by a primary care physician. She received a short course of counseling 6 years ago after her sister was sexually abused by her grandfather. Approximately 6 months ago, Ms. A engaged in self-injurious behavior by cutting herself, and she briefly received counseling. There is no history of suicide attempts, psychiatric hospitalization, or a psychiatric diagnosis.

Medical and surgical history include viral meningitis at age 6 months. Medical records show a visit to the ED for abdominal pain after a classmate punched her in the abdomen, which resolved with supportive care. She was given a diagnosis of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections 6 years ago.

Ms. A developed multiple recurrent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus abscesses a year ago, which lasted for 4 months; it was noted that she was self-inoculating by scratching eczema. She had a possible syncopal episode 5 months ago, but the medical work-up was normal. The pediatric neurology service diagnosed and treated seizures 4 months ago.

Levetiracetam was prescribed after a possible syncopal episode followed by a tonic-clonic seizure. Because she was still having seizure-like episodes with a single antiepileptic drug (AED), oxcarbazepine, then valproic acid were added. Whether her seizures were generalized or partial was inconclusive. The seizures were followed by a postictal phase lasting 3 minutes to 1 hour. Her last generalized tonic-clonic seizure was 1 month before admission.

Ms. A had 3 MRI studies of the brain over the past 3 years, which showed consistent and unchanged multifocal punctate white matter lesions. The findings represented gliosis from an old perivascular inflammation, trauma, or ischemic damage. There is no history of traumatic brain injury.

Her perinatal history is unremarkable, with normal vaginal delivery at 36 weeks (pre-term birth). All developmental milestones were on target.

Ms. A lives at home with her mother, 6-year-old brother, and stepfather. Her parents are divorced, but her biological father has been involved in her upbringing. She is in seventh grade, but is home schooled after she withdrew from school because of multiple seizure episodes. Ms. A denied bullying at school although she had been punched by a peer. It was unclear if it was a single incident or bullying continued and she was hesitant to disclose it.

The authors’ observations

We focus on the amnesia because it has an acute onset and it seems this is the first time Ms. A presented with this symptom. There is no need to wait for neurology consultation, even though organic causes of amnesia need to be ruled out. Our plan is to develop rapport with Ms. A, and then administer a mental status examination focusing on memory assessment. We understand that, because Ms. A’s chief concern is amnesia, she might not be able to provide many details. We start the initial interview with the family in the patient’s room to understand family dynamics, and then interview Ms. A alone.

EVALUATION Memory problems

On initial psychiatric interview, Ms. A can recognize some of her family members. She is seen in clean attire, with short hair, lying in the bed with good eye contact and a calm demeanor. She seems to be difficult to engage because of her reserved nature.

Ms. A displays some psychomotor retardation. She reports her mood as tired, and her affect is flat and mood incongruent. She is alert and oriented to person only; not to place, time, or situation. She can do a simple spelling task, perform 5-minute recall of 3 words, complete serial 3 subtractions, repeat phrases, read aloud, focus on a coin task, and name simple objects. She does not compare similar objects or answer simple historical or factual questions.

Ms. A replies “I don’t know” to most historical questions, such as her birthday, favorite color, and family members; she does not answer when asked how many legs a dog has, who is the current or past president, what month the Fourth of July is in, or when Christmas is. She can complete some memory tasks on the Mini-Mental State Examination, but does not attempt many others. Ms. A says she is upset about her memory deficit, but her affect was flat. Her mood and her affect were incongruent. She describes a vision of a “girl with black holes [for eyes]” in the corner of her hospital room telling her not to believe anyone and that the interviewers are lying to her. Also, she reports that “the girl” tells her to hurt herself and others, but she is not going to act on the commands because she knows it is not the right thing to do. When we ask Ms. A about a history of substance abuse, she says she has never heard of drugs or alcohol.

Overall, she displays multiple apparent deficits in declarative memory, both episodic and semantic. Regarding non-declarative or procedural memory, she can dress herself, use the bathroom independently, order meals off the menu, and feed herself, among other routine tasks, without difficulty.

According to Ms. A’s mother, Ms. A has shown a decline in overall functioning and personality changes during the past 5 months. She started to cut herself superficially on her forearms 6 months ago and also tried to change her appearance with a new hairstyle when school started. She displayed noticeably intense and disturbing writings, artwork, and conversations with others over 3 to 4 months.

She started experiencing seizures, with 3 to 4 seizures a day; however, she could attend sleepovers seizure-free. She had prolonged periods of seizures lasting up to an hour, much longer than would be expected clinically. She also had requested to go to the cemetery for unclear reasons (because the spirit wanted her to visit), and was observed mumbling under her breath.

Six years ago, Ms. A’s 6-year-old sister tried to suffocate her infant brother. Child protective services was involved and the sister was hospitalized in a psychiatric facility, where she was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder; she was then transferred to foster care, and later placed in residential treatment. Her mother relinquished her parental rights and gave custody of Ms. A’s sister to the state.

Ms. A’s mother has a history of depression, but her younger brother is healthy. There is no history of autism, attention problems, tics, substance abuse, brain tumor, or intellectual disabilities in the family.

Which diagnosis does Ms. A’s presentation and history suggest?

a) dissociative amnesia

b) factitious disorder imposed on self

c) conversion disorder (neurological symptom disorder)

d) psychosis not otherwise specified

e) malingering

The authors’ observations

The history of unwitnessed seizures, sudden onset of visual hallucinations, and transient amnesia points to a possible postictal cause. Selective amnesia brings up the question of whether psychological components are driving the symptoms.

Her psychotic symptoms appear to be mediated by anxiety and possibly related to the trauma of losing her only sister when her mother relinquished custody to the state; the circumstances might have aroused feelings of insecurity or fear of abandonment and raised questions about her mother’s love toward her. Her sister’s abuse by a family member might have created reticence to trust others. These background experiences could be intensely conflicting at this age when the second separation individuation process commences, especially in an emotionally immature adolescent.

OUTCOME Medication change

The neurology team recommends discontinuing levetiracetam because the visual hallucinations, mood disturbance, and personality change could be adverse effects of the drug. Because of generalized uncontrolled body movements with staring episodes and unresponsiveness, an EEG is ordered to rule out ongoing seizures.

Ms. A recognizes the psychosomatic medicine team members when they interview her again. The team employs consistent reassurance and a non-confrontational approach. She spends 3 days in the medical unit during which she reports that the frequency of visual and auditory hallucinations decreases and her memory symptoms resolve. Her 24-hour EEG is negative for seizure activity, and the 24-hour video EEG does not show any signs of epileptogenic foci. Ms. A’s family declines inpatient psychiatric hospitalization.

Because of gradual improvement in Ms. A’s symptoms and no imminent safety concerns, she is discharged home with valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and oxcarbazepine, 1,200 mg/d, and follow-up appointments with her primary care physician, a neurologist, and a psychiatrist.

The authors’ observations

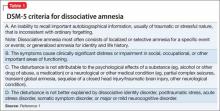

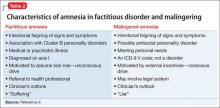

Dissociative amnesia

Generalized dissociative amnesia is difficult to differentiate from factitious disorder or malingering. According to DSM-5, there is loss of episodic memory in dissociative amnesia, in which the person is unable to recall the stressful event after trauma (Table 1).1 Although there have been case reports of dissociative amnesia with loss of semantic and procedural memory, episodic memory is the last to return.2 In Ms. A’s case, there was no immediate basis to explain amnesia onset, although she had experienced the trauma of losing her sister. She had episodic and mostly semantic memory loss.

Although organic causes can precipitate amnesia,3 Ms. A’s EEG and MRI results did not reflect that. Patients with a dissociative disorder often report some physical, sexual, or emotional abuse.4 Although Ms. A did not report any abuse, it cannot be completely ruled out because of her sister’s history of abuse.

Suicidality or self-injurious behavior is common among adults with dissociative amnesia, although it is not well studied in children.4,5 Generally, the constellation of primary dissociative symptoms that patients develop are forgetfulness, fragmentation, and emotional numbing. Ms. A presented with some of these features; did she, in fact, have dissociative amnesia?

Factitious amnesia

Factious amnesia (Table 2)6 is a symptom of factious disorder in which amnesia appears with the motivation to assume a sick role.3 Ms. A’s amnesia garnered significant attention from her mother and other family members; this may have been related to insecurity in her family relationships because her sister was given up to the state. She also could be afraid of entering adolescence and leaving her sister behind. Did she want more time to bond with her mother? Did she experience emotional benefit from being cared for by medical professionals?7 Her affect during interviews was blunted and her attitude was nonchalant, and her multiple visits to the hospital since childhood for abdominal pain, abscesses (it isn’t clear whether the abscesses were related to self-injury and scratching), tics, seizures, and, recently, amnesia and hallucinations indicated some desire to occupy a sick role. Furthermore, the severity of her symptoms seemed to be increasing over time, from somatic to neurologic (seizure-like episodes) to significant and less frequent psychiatric symptoms (amnesia and hallucinations). One could speculate that her symptoms were escalating because she was not receiving the attention she needed.

Malingered amnesia

Although malingering is not a psychiatric diagnosis, it can be a focus of clinical attention. It is challenging to identify malingered cognitive impairments.8 Children often have difficulty malingering symptoms because they have limited understanding of the illness they are trying to simulate.9 Many malingerers do not want to participate in their medical work up and might exhibit a hostile attitude toward examiners (Table 26). Clinicians could rely on family to provide information regarding history and inconsistencies in clinical deficits.9 The clinical interview, mental status examination, and collateral information are crucial for identifying malingering.

Most of Ms. A’s seizure-like episodes happened in specific contexts, such as in school, but not at friends’ houses, raising the question of whether she is aware of her episodes. Ms. A’s grades are consistently good; because she is being home schooled, there is no secondary gain from not going to school. There is no other reason to speculate that she was malingering.

The inconsistency of Ms. A’s symptoms and her compliance with assessment and treatment did not reflect malingering. Interestingly, Ms. A’s amnesia was retrograde in nature. There have been more studies on malingered anterograde amnesia8 than on retrograde amnesia, making her presentation even more unusual.

Amnesia presenting as conversion disorder

Amnesia as a symptom of conversion disorder is referred as psychogenic amnesia; the memory loss mostly is isolated retrograde amnesia.10 Ms. A likely had unconsciously produced symptoms of non-epileptic seizures, followed by auditory and visual hallucinations not related to her seizures, and then later developed selective transient amnesia. Conversion disorder seemed to be the diagnosis most consistent with her indifference (“la belle indifference”) and the significant attention she gained from the acute memory loss (Table 3).1 It seemed that she developed multiple symptoms in progression leading toward a conversion disorder diagnosis. The question arises whether Ms. A’s presentation is a gradually increasing cry for help or reflects depressive or anxiety symptoms, which often are comorbid with conversion disorder.

FOLLOW-UP Suicide attempt

Ms. A has frequent visits to the ED with symptoms of syncope and seizures and undergoes medical work-up and multiple EEGs. A prolonged 5-day video EEG is performed to assess seizure episodes after AEDs were withdrawn, but no seizure activity is elicited. She also has an ED visit for recurrent tic emergence.

The last visit in the ED is for a suicide attempt with overdose of an unknown quantity of unspecified pills. Ms. A talks to a social worker, who reports that Ms. A needed answers to such questions as why her grandfather abused her sister? Could she have stopped them and made a difference for the family?

The authors’ observations

Conversion disorder arises from unconscious psychological conflicts, needs, or responses to trauma. Ms. A’s consistent conflict about her sister and grandfather’s relationship was evident from occasions when she tried to confide in hospital staff. During an ED visit, she reported her sister’s abuse to a staff member. Another time, while recovering from sedation, she spontaneously spoke about her sister’s abuse. When asked again, she said she did not remember saying it.

Freud said that patients develop conversion disorder to avoid unacceptable conflicting thoughts and feelings.10 It appeared that Ms. A was struggling with these questions because she brought them up again when she visited the ED after the suicide attempt.

Dissociative symptoms arise from unstable parenting and disciplining styles with variable family dynamics. Patients show extreme detachment and emotional unresponsiveness akin to attachment disorder.11 Ms. A had inconsistent parenting because both her stepfather and biological father were involved with her care. Her mother had relinquished her parental rights to her sister, which indicated some attachment issues.

Ms. A’s idea that her mother was indifferent stemmed from her uncaring approach toward her sister and not able to understand her emotionally. Her amnesia could be thought of as “I don’t know you because I don’t remember that I am related to you.” The traumas of infancy (referred to as hidden traumas) that were a result of parent-child mismatch of needs and availability at times of distress might not be obvious to the examiner.11

Although Ms. A’s infancy was reported to be unremarkable, there always is a question, especially in a consultation-liaison setting, of whether conversion disorder might be masking an attachment problem. Perhaps with long-term psychotherapy, an attachment issue would be revealed.