User login

CASE A fainting spell

Ms. A, age 13, is admitted to a pediatric unit after fainting and losing consciousness for 5 minutes in the shower, during which time she was non-responsive. She reports feeling nauseated and having blurry vision before dropping to the floor.

Ms. A reports intentional self-restriction of calories, self-induced vomiting, and other purging behaviors, such as laxative abuse and excessive exercising.

During the mental status examination, Ms. A is lying in bed wearing hospital clothes, legs flexed at the knee, hands on her side, and a fixed gaze at the ceiling with poor eye contact. She is of slender stature and tall, seems slightly older than her stated age, and is poorly groomed.

Throughout the interview, Ms. A has significant psychomotor retardation, reports her mood as tired, and has a blunted affect. She speaks at a low volume and has poverty of speech; she takes deep sighs before answering questions. Her thought process is linear and she cooperates with the interview. She has poor recall, including delayed 3-minute recall and poor sustained attention. Her abstraction capacity is fair and her intellect is average and comparable with her age group. Ms. A is preoccupied that eating will cause weight gain. She denies hallucinations but reports passive death wishes with self-harm by scratching.

What is the differential diagnosis to explain Ms. A’s presentation?

a) syncope

b) seizures

c) dehydration

d) hypotension

HISTORY Preoccupied with weight

Ms. A reports vomiting twice a day, while showering and at night when no one is around, every day for 2 months. She stopped eating and taking in fluids 3 days before admission to the medical unit. Also, she reports restricting her diet to 700 to 1,000 calories a day, skipping lunch at school, and eating minimally at night. Ms. A uses raspberry ketones and green coffee beans, which are advertised to aid weight loss, and laxative pills from her mother’s medicine cabinet once or twice a week when her throat is sore from vomiting. She reports exercising excessively, which includes running, crunches, and lifting weights. She has lost approximately 30 lb in the last 2 months.

Ms. A says she fears gaining weight and feels increased guilt after eating a meal. She said that looking at food induced “anxiety attack” symptoms of increased heart rate, sweaty palms, feeling of choking, nervousness, and shakiness. She adds that she does not want to be “bigger” than her classmates. Her understanding of the consequences of not eating is, “It will get worse, I will shut down and die. I do not fear death, I only fear getting bigger than others.”

She reports that her fixation on avoiding food started when she realized that she was the tallest girl in her class and the only girl in her class running on the track team, after which she quit athletics. She reports that depression symptoms pre-dated her eating disorder symptoms; onset of significant depression likely was precipitated by her grandfather’s death a year earlier, and then exacerbated by the recent death of a family pet.

Ms. A’s depressive symptoms are described as anhedonia (avoiding being outside and not enjoying drawing anymore), decreased energy, tearfulness, sadness, decreased concentration, and passive suicidal thoughts. Her mother is supportive and motivates her daughter to “get better.” Ms. A denies any symptoms of psychosis, other anxiety symptoms, other mood disorder symptoms, substance abuse, or homicidality.

Ms. A’s mother says she felt that, recently, her daughter has been having some difficulty with confused thoughts and significantly delayed responses. However, the mother reports that her daughter always had somewhat delayed responses from what she felt is typical. Her mother adds that Ms. A’s suicidal thoughts have worsened since her daughter started restricting her diet.

Which diagnosis likely accounts for Ms. A’s presentation?

a) major depressive disorder (MDD)

b) eating disorder, not otherwise specified (NOS)

c) anorexia nervosa, purging type

d) catatonia, unspecified

e) anxiety disorder NOS

f) cognitive disorder

g) psychosis NOS

The authors’ observations

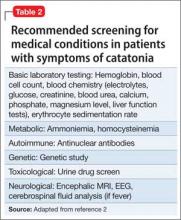

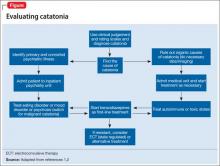

There are many reported causes of catatonia in children and adolescents, including those that are psychiatric, medical, or neurological, as well as drugs (Table 1).1,2 Affective disorders have been associated with catatonia in adults, but has not been widely reported in children and adolescents.1,3 Organic and neurologic causes, such as neurological tumors and cerebral hemorrhage, should be ruled out first because, although rare, they can be fatal (Table 2).2 If the cause of catatonia is not recognized quickly (Figure,1,2) effective treatment could be delayed.4

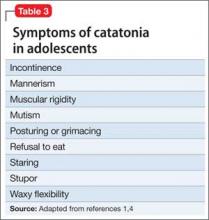

Catatonia involves psychomotor abnormalities, which are listed in Table 3.1,4

Presentation in adults and adolescents is similar.

An eating disorder could be comorbid with another psychiatric disorder, such as MDD, dysthymia, or panic disorder.5 Ms. A’s report of depression before she began restricting food favored a primary diagnosis of MDD. Her depressive symptoms of low appetite or low self-worth could have led to her preoccupation with body image.

There has been evidence that negative self-image and eating disorders are associated, but data are limited and the connection remains unclear.6 Ms. A’s self-esteem was very low. Her fixation on restricting food could have been perpetuated by her self-criticism and by being excluded from her peer group in school. Her weight loss could have brought anxiety symptoms to the forefront because of physiologic changes that accompany extreme weight loss.

The treatment team was concerned about her delayed responses, which could be explained by the catatonic features that reflected the severity of her depression. She had no obvious symptoms of psychosis, but her intrusive thoughts and obsessions with avoiding food did not completely rule out psychosis.

Childhood-onset schizophrenia, although rare, has been associated with catatonia; following up with a catatonia rating scale, such as the Catatonia Rating Scale or the Bush- Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS), would be useful for tracking symptom progress. In Ms. A’s case, her mood disorder was primary, but did not rule out psychosis-like prodromal symptoms.7

Ms. A is diagnosed with MDD, single episode, severe, with catatonic features, and without psychosis, and eating disorder, NOS.

EVALUATION Mostly normal

Ms. A does not have a history of mental illness and was not seeing a psychiatrist or therapist, nor did she have any prior psychiatric admissions. She denies suicide attempts, but reports self-injurious behavior involving scratching her skin, which started during the current mood episode. She has never taken any psychotropic medications. Ms. A lives at home with her biological mother and father and 17-year-old brother. She attends middle school with average grades and has no history of disciplinary actions. She has no history of bullying or teasing, although she did report some previous difficulty with relational aggression toward her peers in the 5th grade. Her mother has a history of anorexia nervosa that began when she was a teenager, but these symptoms are stable and under control. There is additionally a family history of bipolar disorder.

Ms. A has a family history of coronary artery disease and diabetes in the mother and maternal relatives. Her grandfather died from liver cancer. She was allergic to sulfa drugs and was taking a multivitamin and minocycline for acne.

Physical examination reveals some superficial scratches but otherwise was within normal limits. Initial lab results reveal a normal complete blood count and differential. Thyroid-stimulating hormone is 1.29 mIU/L and free T4 is 0.96 mg/dL, both within normal limits. Urinalysis is within normal limits and urine pregnancy test is negative. A comprehensive metabolic panel shows mild elevation in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 60 U/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 92 U/L, respectively. Phosphorus level is within normal limits. Prealbumin level is slightly low at 15.1 mg/dL.

Which treatment plan would you recommend for Ms. A?

a) discharge with outpatient psychiatric treatment

b) recommend medical stabilization with follow-up from the psychosomatic team and then outpatient psychiatric follow-up

c) admit her to the psychiatric acute inpatient hospital with psychiatric outpatient discharge follow-up plan

d) discharge her home with follow-up with her primary care physician

e) recommend follow-up from the psychosomatic team while on medical floor with acute inpatient admission and psychiatric outpatient follow-up at discharge

The authors’ observations

Scarcity of data and reporting of cases of adolescent catatonia limits guidance for diagnosis and treatment.8 There are several rating scales with variability in definition, but that overall provide a guiding tool for detecting catatonia. The Brief Cognitive Rating Scale is considered the most versatile because it is more valid, reliable, and requires less time to complete than other rating scales.9

Ms. A’s symptoms were a combination of depressive symptoms with severity defined by catatonic features, eating disorder with worsening course, anxiety symptoms, and genetic loading of eating disorder in her mother. The challenge of this case was making an accurate diagnosis and treating Ms. A, which required continuous observation following an eating disorder protocol, resolution of her catatonia, resuming a normal diet, and decreasing her suicidality. Retrospectively, her scores on the BFCRS were high on screening items 1 to 14, which measure presence or absence and severity of symptoms.

The best option was to admit Ms. A to an inpatient psychiatric facility after she is cleared medically with outpatient services to follow up.

How would you treat Ms. A’s symptoms?

a) aggressively treat catatonia

b) address her eating disorder

c) work to resolve her depression

The authors’ observations

The challenge was to choose the psychotropic medication that would target her depression, obsessive, rigid thoughts, and catatonia. Administering an antidepressant with an antipsychotic would have relieved her depressive and obsessive symptoms but would not have improved her catatonia. The psychosomatic medicine team recommended starting a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a benzodiazepine to target both the depression and the catatonic symptoms. Ms. A received sertraline, 12.5 mg/d, which was increased to 25 mg/d on the third day. IV lorazepam, 1 mg, 3 times a day, was recommended but the pediatric team prescribed an oral formulation. The hospital’s eating disorder protocol was instituted on the day of admission.

Treatment options for catatonia

Benzodiazepines are the first line of treatment for catatonia and other neuroleptics, specifically antipsychotics, have been considered dangerous.10 Benzodiazepine-resistant catatonia, which is sometimes seen in patients with autism, might respond to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT),11 although in some states it cannot be administered to children age <18.12 Benzodiazepines have shown dramatic improvement within hours, as has ECT.8,13 Additionally, if patients do not respond to a benzodiazepine or ECT, consider other options such as zolpidem, olanzapine,14 or sensory integration system (in adolescents with autism).15

Ms. A did not need ECT or an alternative treatment because she responded well to 3 doses of oral lorazepam. Her amotivation, negativism, and rigidity with prolonged posturing improved. Her psychomotor retardation improved overall, although she reported some dizziness and had some postural hypotension, which was attributed to her eating issues and dehydration.

OUTCOME Feeling motivated

Ms. A is transferred to psychiatric inpatient unit. She tolerates sertraline, which is titrated to 50 mg/d. She is placed on the hospital’s standard eating disorder protocol. She continues to eat well with adequate intake of solids and liquid and exhibits only some anxiety associated with meals. During the course of hospitalization, she attends group therapy and her catatonic symptoms completely resolve. She says she thinks that her thoughts are improving and that she is not longer feeling confused. She reports being motivated to continue to improve her eating disorder symptoms.

The treatment team holds a family session during which family dynamic issues that are stressful to Ms. A are discussed, such as some conflict with her parents as well as some negative interactions between Ms. A and her father. Repeat comprehensive metabolic panel on admission to the inpatient psychiatric hospital reveals persistent elevation of AST at 92 U/L and ALT at 143 U/L. Ms. A is discharged home with follow-up with a psychiatrist and a therapist. The treatment team also recommends that she follow up in a program that specializes in eating disorders.

4-month follow-up. Ms. A returns to inpatient psychiatric hospital after overdose of sertraline and aripiprazole, which were started by an outpatient psychiatrist. She reports severe depressive symptoms because of school stressors. She denies any problems eating and did not show any symptoms of catatonia. In her chart, there is a mention of “cloudy thoughts” and quietness. At this admission, her ALT is 17 U/L and AST is 19 U/L. Sertraline is increased to 150 mg/d and aripiprazole is reduced to 2 mg/d and then later increased to 5 mg/d, after which she is discharged home with an outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

1-year follow-up. Ms. A has been following up with an outpatient psychiatrist and is receiving sertraline, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 2.5 mg/d, and extended-release methylphenidate, 36 mg/d, along with L-methylfolate, multivitamins, and omega-3 fish oil as adjuvants for her depressive symptoms. Ms. A does not show symptoms of an eating disorder or catatonia, and her depression and psychomotor activity have improved, with better overall functionality, after adding the stimulant and adjunctives to the antidepressant.

The authors’ observations

The importance of including catatonia NOS with its various specifiers, such as medical, metabolic, toxic, affective, etc., has been discussed.16,17 In Ms. A’s case, instead of treating the specific symptoms—affective or eating disorder or obsessive quality of thought content, mimicking psychotic-like symptoms—addressing the catatonia initially had a better outcome. More studies related to chronic and acute catatonia in adolescents are needed because of the risk of increased morbidity and premature death.18 Early recognition of catatonia is needed19 because it often is underdiagnosed.20

Eating disorders often become worse over the first 5 years, and close monitoring and assessment is needed for adolescents.21 Also, prodromal psychotic symptoms require follow-up because techniques for early detection and intervention for children and adolescents are still in their infancy.22

Bottom Line

Catatonia in adolescents should be addressed early, when it is treatable and the outcome is favorable. It is important to recognize catatonia in an emergency department or inpatient medical unit setting in a hospital because it is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. The presentation of catatonia is similar in adolescents and adults. Benzodiazepines are first-line treatment for catatonia; consider electroconvulsive therapy if patients do not respond to drug therapy.

Related Resources

• Roberto AJ, Pinnaka S, Mohan A, et al. Adolescent catatonia successfully treated with lorazepam and aripiprazole. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2014;2014:309517. doi: 10.1155/2014/309517.

• Raffin M, Zugaj-Bensaou L, Bodeau N, et al. Treatment use in a prospective naturalistic cohort of children and adolescents with catatonia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(4):441-449.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Minocycline • Minocin

L-methylfolate • Deplin Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Lorazepam • Ativan Sertraline • Zoloft

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta Zolpidem • Ambien, Intermezzo

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Dhossche D, Wilson C, Wachtel LE. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence: implications for the DSM-5. Primary Psychiatry. http://primarypsychiatry.com/catatonia-in-childhood-and-adolescence-implications-for-the-dsm-5. Published May 21, 2013. Accessed July 2, 2015.

2. Lahutte B, Cornic F, Bonnot O, et al. Multidisciplinary approach of organic catatonia in children and adolescents may improve treatment decision making. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):1393-1398.

3. Brake JA, Abidi S. A case of adolescent catatonia. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):138-140.

4. Consoli A, Raffin M, Laurent C, et al. Medical and developmental risk factors of catatonia in children and adolescents: a prospective case-control study. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):151-158.

5. Zaider TI, Johnson JG, Cockell SJ. Psychiatric comorbidity associated with eating disorder symptomatology among adolescents in the community. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(1):58-67.

6. Forsén Mantilla E, Bergsten K, Birgegård A. Self-image and eating disorder symptoms in normal and clinical adolescents. Eat Behav. 2014;15(1):125-131.

7. Bonnot O, Tanguy ML, Consoli A, et al. Does catatonia influence the phenomenology of childhood onset schizophrenia beyond motor symptoms? Psychiatry Res. 2008;158(3):356-362.

8. Singh LK, Praharaj SK. Immediate response to lorazepam in a patient with 17 years of chronic catatonia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(3):E47-E48.

9. Sienaert P, Rooseleer J, De Fruyt J. Measuring catatonia: a systematic review of rating scales. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):1-9.

10. Cottencin O, Warembourg F, de Chouly de Lenclave MB, et al. Catatonia and consultation-liaison psychiatry study of 12 cases. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(6):1170-1176.

11. Wachtel LE, Hermida A, Dhossche DM. Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in autistic catatonia: a case series review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):581-587.

12. Wachtel LE, Dhossche DM, Kellner CH. When is electroconvulsive therapy appropriate for children and adolescents? Med Hypotheses. 2011;76(3):395-399.

13. Takaoka K, Takata T. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57(2):129-137.

14. Ceylan MF, Kul M, Kultur SE, et al. Major depression with catatonic features in a child remitted with olanzapine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(3):225-227.

15. Consoli A, Gheorghiev C, Jutard C, et al. Lorazepam, fluoxetine and packing therapy in an adolescent with pervasive developmental disorder and catatonia. J Physiol Paris. 2010;104(6):309-314.

16. Dhossche D, Cohen D, Ghaziuddin N, et al. The study of pediatric catatonia supports a home of its own for catatonia in DSM-5. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75(6):558-560.

17. Taylor MA, Fink M. Catatonia in psychiatric classification: a home of its own. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1233-1241.

18. Cornic F, Consoli A, Tanguy ML, et al. Association of adolescent catatonia with increased mortality and morbidity: evidence from a prospective follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):233-240.

19. Quigley J, Lommel KM, Coffey B. Catatonia in an adolescent with Asperger’s disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):93-96.

20. Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):33-38.

21. Ackard DM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Stability of eating disorder diagnostic classifications in adolescents: five-year longitudinal findings from a population-based study. Eat Disord. 2011;19(4):308-322.

22. Schimmelmann BG, Schultze-Lutter F. Early detection and intervention of psychosis in children and adolescents: urgent need for studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(5):239-241.

CASE A fainting spell

Ms. A, age 13, is admitted to a pediatric unit after fainting and losing consciousness for 5 minutes in the shower, during which time she was non-responsive. She reports feeling nauseated and having blurry vision before dropping to the floor.

Ms. A reports intentional self-restriction of calories, self-induced vomiting, and other purging behaviors, such as laxative abuse and excessive exercising.

During the mental status examination, Ms. A is lying in bed wearing hospital clothes, legs flexed at the knee, hands on her side, and a fixed gaze at the ceiling with poor eye contact. She is of slender stature and tall, seems slightly older than her stated age, and is poorly groomed.

Throughout the interview, Ms. A has significant psychomotor retardation, reports her mood as tired, and has a blunted affect. She speaks at a low volume and has poverty of speech; she takes deep sighs before answering questions. Her thought process is linear and she cooperates with the interview. She has poor recall, including delayed 3-minute recall and poor sustained attention. Her abstraction capacity is fair and her intellect is average and comparable with her age group. Ms. A is preoccupied that eating will cause weight gain. She denies hallucinations but reports passive death wishes with self-harm by scratching.

What is the differential diagnosis to explain Ms. A’s presentation?

a) syncope

b) seizures

c) dehydration

d) hypotension

HISTORY Preoccupied with weight

Ms. A reports vomiting twice a day, while showering and at night when no one is around, every day for 2 months. She stopped eating and taking in fluids 3 days before admission to the medical unit. Also, she reports restricting her diet to 700 to 1,000 calories a day, skipping lunch at school, and eating minimally at night. Ms. A uses raspberry ketones and green coffee beans, which are advertised to aid weight loss, and laxative pills from her mother’s medicine cabinet once or twice a week when her throat is sore from vomiting. She reports exercising excessively, which includes running, crunches, and lifting weights. She has lost approximately 30 lb in the last 2 months.

Ms. A says she fears gaining weight and feels increased guilt after eating a meal. She said that looking at food induced “anxiety attack” symptoms of increased heart rate, sweaty palms, feeling of choking, nervousness, and shakiness. She adds that she does not want to be “bigger” than her classmates. Her understanding of the consequences of not eating is, “It will get worse, I will shut down and die. I do not fear death, I only fear getting bigger than others.”

She reports that her fixation on avoiding food started when she realized that she was the tallest girl in her class and the only girl in her class running on the track team, after which she quit athletics. She reports that depression symptoms pre-dated her eating disorder symptoms; onset of significant depression likely was precipitated by her grandfather’s death a year earlier, and then exacerbated by the recent death of a family pet.

Ms. A’s depressive symptoms are described as anhedonia (avoiding being outside and not enjoying drawing anymore), decreased energy, tearfulness, sadness, decreased concentration, and passive suicidal thoughts. Her mother is supportive and motivates her daughter to “get better.” Ms. A denies any symptoms of psychosis, other anxiety symptoms, other mood disorder symptoms, substance abuse, or homicidality.

Ms. A’s mother says she felt that, recently, her daughter has been having some difficulty with confused thoughts and significantly delayed responses. However, the mother reports that her daughter always had somewhat delayed responses from what she felt is typical. Her mother adds that Ms. A’s suicidal thoughts have worsened since her daughter started restricting her diet.

Which diagnosis likely accounts for Ms. A’s presentation?

a) major depressive disorder (MDD)

b) eating disorder, not otherwise specified (NOS)

c) anorexia nervosa, purging type

d) catatonia, unspecified

e) anxiety disorder NOS

f) cognitive disorder

g) psychosis NOS

The authors’ observations

There are many reported causes of catatonia in children and adolescents, including those that are psychiatric, medical, or neurological, as well as drugs (Table 1).1,2 Affective disorders have been associated with catatonia in adults, but has not been widely reported in children and adolescents.1,3 Organic and neurologic causes, such as neurological tumors and cerebral hemorrhage, should be ruled out first because, although rare, they can be fatal (Table 2).2 If the cause of catatonia is not recognized quickly (Figure,1,2) effective treatment could be delayed.4

Catatonia involves psychomotor abnormalities, which are listed in Table 3.1,4

Presentation in adults and adolescents is similar.

An eating disorder could be comorbid with another psychiatric disorder, such as MDD, dysthymia, or panic disorder.5 Ms. A’s report of depression before she began restricting food favored a primary diagnosis of MDD. Her depressive symptoms of low appetite or low self-worth could have led to her preoccupation with body image.

There has been evidence that negative self-image and eating disorders are associated, but data are limited and the connection remains unclear.6 Ms. A’s self-esteem was very low. Her fixation on restricting food could have been perpetuated by her self-criticism and by being excluded from her peer group in school. Her weight loss could have brought anxiety symptoms to the forefront because of physiologic changes that accompany extreme weight loss.

The treatment team was concerned about her delayed responses, which could be explained by the catatonic features that reflected the severity of her depression. She had no obvious symptoms of psychosis, but her intrusive thoughts and obsessions with avoiding food did not completely rule out psychosis.

Childhood-onset schizophrenia, although rare, has been associated with catatonia; following up with a catatonia rating scale, such as the Catatonia Rating Scale or the Bush- Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS), would be useful for tracking symptom progress. In Ms. A’s case, her mood disorder was primary, but did not rule out psychosis-like prodromal symptoms.7

Ms. A is diagnosed with MDD, single episode, severe, with catatonic features, and without psychosis, and eating disorder, NOS.

EVALUATION Mostly normal

Ms. A does not have a history of mental illness and was not seeing a psychiatrist or therapist, nor did she have any prior psychiatric admissions. She denies suicide attempts, but reports self-injurious behavior involving scratching her skin, which started during the current mood episode. She has never taken any psychotropic medications. Ms. A lives at home with her biological mother and father and 17-year-old brother. She attends middle school with average grades and has no history of disciplinary actions. She has no history of bullying or teasing, although she did report some previous difficulty with relational aggression toward her peers in the 5th grade. Her mother has a history of anorexia nervosa that began when she was a teenager, but these symptoms are stable and under control. There is additionally a family history of bipolar disorder.

Ms. A has a family history of coronary artery disease and diabetes in the mother and maternal relatives. Her grandfather died from liver cancer. She was allergic to sulfa drugs and was taking a multivitamin and minocycline for acne.

Physical examination reveals some superficial scratches but otherwise was within normal limits. Initial lab results reveal a normal complete blood count and differential. Thyroid-stimulating hormone is 1.29 mIU/L and free T4 is 0.96 mg/dL, both within normal limits. Urinalysis is within normal limits and urine pregnancy test is negative. A comprehensive metabolic panel shows mild elevation in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 60 U/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 92 U/L, respectively. Phosphorus level is within normal limits. Prealbumin level is slightly low at 15.1 mg/dL.

Which treatment plan would you recommend for Ms. A?

a) discharge with outpatient psychiatric treatment

b) recommend medical stabilization with follow-up from the psychosomatic team and then outpatient psychiatric follow-up

c) admit her to the psychiatric acute inpatient hospital with psychiatric outpatient discharge follow-up plan

d) discharge her home with follow-up with her primary care physician

e) recommend follow-up from the psychosomatic team while on medical floor with acute inpatient admission and psychiatric outpatient follow-up at discharge

The authors’ observations

Scarcity of data and reporting of cases of adolescent catatonia limits guidance for diagnosis and treatment.8 There are several rating scales with variability in definition, but that overall provide a guiding tool for detecting catatonia. The Brief Cognitive Rating Scale is considered the most versatile because it is more valid, reliable, and requires less time to complete than other rating scales.9

Ms. A’s symptoms were a combination of depressive symptoms with severity defined by catatonic features, eating disorder with worsening course, anxiety symptoms, and genetic loading of eating disorder in her mother. The challenge of this case was making an accurate diagnosis and treating Ms. A, which required continuous observation following an eating disorder protocol, resolution of her catatonia, resuming a normal diet, and decreasing her suicidality. Retrospectively, her scores on the BFCRS were high on screening items 1 to 14, which measure presence or absence and severity of symptoms.

The best option was to admit Ms. A to an inpatient psychiatric facility after she is cleared medically with outpatient services to follow up.

How would you treat Ms. A’s symptoms?

a) aggressively treat catatonia

b) address her eating disorder

c) work to resolve her depression

The authors’ observations

The challenge was to choose the psychotropic medication that would target her depression, obsessive, rigid thoughts, and catatonia. Administering an antidepressant with an antipsychotic would have relieved her depressive and obsessive symptoms but would not have improved her catatonia. The psychosomatic medicine team recommended starting a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a benzodiazepine to target both the depression and the catatonic symptoms. Ms. A received sertraline, 12.5 mg/d, which was increased to 25 mg/d on the third day. IV lorazepam, 1 mg, 3 times a day, was recommended but the pediatric team prescribed an oral formulation. The hospital’s eating disorder protocol was instituted on the day of admission.

Treatment options for catatonia

Benzodiazepines are the first line of treatment for catatonia and other neuroleptics, specifically antipsychotics, have been considered dangerous.10 Benzodiazepine-resistant catatonia, which is sometimes seen in patients with autism, might respond to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT),11 although in some states it cannot be administered to children age <18.12 Benzodiazepines have shown dramatic improvement within hours, as has ECT.8,13 Additionally, if patients do not respond to a benzodiazepine or ECT, consider other options such as zolpidem, olanzapine,14 or sensory integration system (in adolescents with autism).15

Ms. A did not need ECT or an alternative treatment because she responded well to 3 doses of oral lorazepam. Her amotivation, negativism, and rigidity with prolonged posturing improved. Her psychomotor retardation improved overall, although she reported some dizziness and had some postural hypotension, which was attributed to her eating issues and dehydration.

OUTCOME Feeling motivated

Ms. A is transferred to psychiatric inpatient unit. She tolerates sertraline, which is titrated to 50 mg/d. She is placed on the hospital’s standard eating disorder protocol. She continues to eat well with adequate intake of solids and liquid and exhibits only some anxiety associated with meals. During the course of hospitalization, she attends group therapy and her catatonic symptoms completely resolve. She says she thinks that her thoughts are improving and that she is not longer feeling confused. She reports being motivated to continue to improve her eating disorder symptoms.

The treatment team holds a family session during which family dynamic issues that are stressful to Ms. A are discussed, such as some conflict with her parents as well as some negative interactions between Ms. A and her father. Repeat comprehensive metabolic panel on admission to the inpatient psychiatric hospital reveals persistent elevation of AST at 92 U/L and ALT at 143 U/L. Ms. A is discharged home with follow-up with a psychiatrist and a therapist. The treatment team also recommends that she follow up in a program that specializes in eating disorders.

4-month follow-up. Ms. A returns to inpatient psychiatric hospital after overdose of sertraline and aripiprazole, which were started by an outpatient psychiatrist. She reports severe depressive symptoms because of school stressors. She denies any problems eating and did not show any symptoms of catatonia. In her chart, there is a mention of “cloudy thoughts” and quietness. At this admission, her ALT is 17 U/L and AST is 19 U/L. Sertraline is increased to 150 mg/d and aripiprazole is reduced to 2 mg/d and then later increased to 5 mg/d, after which she is discharged home with an outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

1-year follow-up. Ms. A has been following up with an outpatient psychiatrist and is receiving sertraline, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 2.5 mg/d, and extended-release methylphenidate, 36 mg/d, along with L-methylfolate, multivitamins, and omega-3 fish oil as adjuvants for her depressive symptoms. Ms. A does not show symptoms of an eating disorder or catatonia, and her depression and psychomotor activity have improved, with better overall functionality, after adding the stimulant and adjunctives to the antidepressant.

The authors’ observations

The importance of including catatonia NOS with its various specifiers, such as medical, metabolic, toxic, affective, etc., has been discussed.16,17 In Ms. A’s case, instead of treating the specific symptoms—affective or eating disorder or obsessive quality of thought content, mimicking psychotic-like symptoms—addressing the catatonia initially had a better outcome. More studies related to chronic and acute catatonia in adolescents are needed because of the risk of increased morbidity and premature death.18 Early recognition of catatonia is needed19 because it often is underdiagnosed.20

Eating disorders often become worse over the first 5 years, and close monitoring and assessment is needed for adolescents.21 Also, prodromal psychotic symptoms require follow-up because techniques for early detection and intervention for children and adolescents are still in their infancy.22

Bottom Line

Catatonia in adolescents should be addressed early, when it is treatable and the outcome is favorable. It is important to recognize catatonia in an emergency department or inpatient medical unit setting in a hospital because it is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. The presentation of catatonia is similar in adolescents and adults. Benzodiazepines are first-line treatment for catatonia; consider electroconvulsive therapy if patients do not respond to drug therapy.

Related Resources

• Roberto AJ, Pinnaka S, Mohan A, et al. Adolescent catatonia successfully treated with lorazepam and aripiprazole. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2014;2014:309517. doi: 10.1155/2014/309517.

• Raffin M, Zugaj-Bensaou L, Bodeau N, et al. Treatment use in a prospective naturalistic cohort of children and adolescents with catatonia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(4):441-449.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Minocycline • Minocin

L-methylfolate • Deplin Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Lorazepam • Ativan Sertraline • Zoloft

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta Zolpidem • Ambien, Intermezzo

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE A fainting spell

Ms. A, age 13, is admitted to a pediatric unit after fainting and losing consciousness for 5 minutes in the shower, during which time she was non-responsive. She reports feeling nauseated and having blurry vision before dropping to the floor.

Ms. A reports intentional self-restriction of calories, self-induced vomiting, and other purging behaviors, such as laxative abuse and excessive exercising.

During the mental status examination, Ms. A is lying in bed wearing hospital clothes, legs flexed at the knee, hands on her side, and a fixed gaze at the ceiling with poor eye contact. She is of slender stature and tall, seems slightly older than her stated age, and is poorly groomed.

Throughout the interview, Ms. A has significant psychomotor retardation, reports her mood as tired, and has a blunted affect. She speaks at a low volume and has poverty of speech; she takes deep sighs before answering questions. Her thought process is linear and she cooperates with the interview. She has poor recall, including delayed 3-minute recall and poor sustained attention. Her abstraction capacity is fair and her intellect is average and comparable with her age group. Ms. A is preoccupied that eating will cause weight gain. She denies hallucinations but reports passive death wishes with self-harm by scratching.

What is the differential diagnosis to explain Ms. A’s presentation?

a) syncope

b) seizures

c) dehydration

d) hypotension

HISTORY Preoccupied with weight

Ms. A reports vomiting twice a day, while showering and at night when no one is around, every day for 2 months. She stopped eating and taking in fluids 3 days before admission to the medical unit. Also, she reports restricting her diet to 700 to 1,000 calories a day, skipping lunch at school, and eating minimally at night. Ms. A uses raspberry ketones and green coffee beans, which are advertised to aid weight loss, and laxative pills from her mother’s medicine cabinet once or twice a week when her throat is sore from vomiting. She reports exercising excessively, which includes running, crunches, and lifting weights. She has lost approximately 30 lb in the last 2 months.

Ms. A says she fears gaining weight and feels increased guilt after eating a meal. She said that looking at food induced “anxiety attack” symptoms of increased heart rate, sweaty palms, feeling of choking, nervousness, and shakiness. She adds that she does not want to be “bigger” than her classmates. Her understanding of the consequences of not eating is, “It will get worse, I will shut down and die. I do not fear death, I only fear getting bigger than others.”

She reports that her fixation on avoiding food started when she realized that she was the tallest girl in her class and the only girl in her class running on the track team, after which she quit athletics. She reports that depression symptoms pre-dated her eating disorder symptoms; onset of significant depression likely was precipitated by her grandfather’s death a year earlier, and then exacerbated by the recent death of a family pet.

Ms. A’s depressive symptoms are described as anhedonia (avoiding being outside and not enjoying drawing anymore), decreased energy, tearfulness, sadness, decreased concentration, and passive suicidal thoughts. Her mother is supportive and motivates her daughter to “get better.” Ms. A denies any symptoms of psychosis, other anxiety symptoms, other mood disorder symptoms, substance abuse, or homicidality.

Ms. A’s mother says she felt that, recently, her daughter has been having some difficulty with confused thoughts and significantly delayed responses. However, the mother reports that her daughter always had somewhat delayed responses from what she felt is typical. Her mother adds that Ms. A’s suicidal thoughts have worsened since her daughter started restricting her diet.

Which diagnosis likely accounts for Ms. A’s presentation?

a) major depressive disorder (MDD)

b) eating disorder, not otherwise specified (NOS)

c) anorexia nervosa, purging type

d) catatonia, unspecified

e) anxiety disorder NOS

f) cognitive disorder

g) psychosis NOS

The authors’ observations

There are many reported causes of catatonia in children and adolescents, including those that are psychiatric, medical, or neurological, as well as drugs (Table 1).1,2 Affective disorders have been associated with catatonia in adults, but has not been widely reported in children and adolescents.1,3 Organic and neurologic causes, such as neurological tumors and cerebral hemorrhage, should be ruled out first because, although rare, they can be fatal (Table 2).2 If the cause of catatonia is not recognized quickly (Figure,1,2) effective treatment could be delayed.4

Catatonia involves psychomotor abnormalities, which are listed in Table 3.1,4

Presentation in adults and adolescents is similar.

An eating disorder could be comorbid with another psychiatric disorder, such as MDD, dysthymia, or panic disorder.5 Ms. A’s report of depression before she began restricting food favored a primary diagnosis of MDD. Her depressive symptoms of low appetite or low self-worth could have led to her preoccupation with body image.

There has been evidence that negative self-image and eating disorders are associated, but data are limited and the connection remains unclear.6 Ms. A’s self-esteem was very low. Her fixation on restricting food could have been perpetuated by her self-criticism and by being excluded from her peer group in school. Her weight loss could have brought anxiety symptoms to the forefront because of physiologic changes that accompany extreme weight loss.

The treatment team was concerned about her delayed responses, which could be explained by the catatonic features that reflected the severity of her depression. She had no obvious symptoms of psychosis, but her intrusive thoughts and obsessions with avoiding food did not completely rule out psychosis.

Childhood-onset schizophrenia, although rare, has been associated with catatonia; following up with a catatonia rating scale, such as the Catatonia Rating Scale or the Bush- Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS), would be useful for tracking symptom progress. In Ms. A’s case, her mood disorder was primary, but did not rule out psychosis-like prodromal symptoms.7

Ms. A is diagnosed with MDD, single episode, severe, with catatonic features, and without psychosis, and eating disorder, NOS.

EVALUATION Mostly normal

Ms. A does not have a history of mental illness and was not seeing a psychiatrist or therapist, nor did she have any prior psychiatric admissions. She denies suicide attempts, but reports self-injurious behavior involving scratching her skin, which started during the current mood episode. She has never taken any psychotropic medications. Ms. A lives at home with her biological mother and father and 17-year-old brother. She attends middle school with average grades and has no history of disciplinary actions. She has no history of bullying or teasing, although she did report some previous difficulty with relational aggression toward her peers in the 5th grade. Her mother has a history of anorexia nervosa that began when she was a teenager, but these symptoms are stable and under control. There is additionally a family history of bipolar disorder.

Ms. A has a family history of coronary artery disease and diabetes in the mother and maternal relatives. Her grandfather died from liver cancer. She was allergic to sulfa drugs and was taking a multivitamin and minocycline for acne.

Physical examination reveals some superficial scratches but otherwise was within normal limits. Initial lab results reveal a normal complete blood count and differential. Thyroid-stimulating hormone is 1.29 mIU/L and free T4 is 0.96 mg/dL, both within normal limits. Urinalysis is within normal limits and urine pregnancy test is negative. A comprehensive metabolic panel shows mild elevation in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 60 U/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 92 U/L, respectively. Phosphorus level is within normal limits. Prealbumin level is slightly low at 15.1 mg/dL.

Which treatment plan would you recommend for Ms. A?

a) discharge with outpatient psychiatric treatment

b) recommend medical stabilization with follow-up from the psychosomatic team and then outpatient psychiatric follow-up

c) admit her to the psychiatric acute inpatient hospital with psychiatric outpatient discharge follow-up plan

d) discharge her home with follow-up with her primary care physician

e) recommend follow-up from the psychosomatic team while on medical floor with acute inpatient admission and psychiatric outpatient follow-up at discharge

The authors’ observations

Scarcity of data and reporting of cases of adolescent catatonia limits guidance for diagnosis and treatment.8 There are several rating scales with variability in definition, but that overall provide a guiding tool for detecting catatonia. The Brief Cognitive Rating Scale is considered the most versatile because it is more valid, reliable, and requires less time to complete than other rating scales.9

Ms. A’s symptoms were a combination of depressive symptoms with severity defined by catatonic features, eating disorder with worsening course, anxiety symptoms, and genetic loading of eating disorder in her mother. The challenge of this case was making an accurate diagnosis and treating Ms. A, which required continuous observation following an eating disorder protocol, resolution of her catatonia, resuming a normal diet, and decreasing her suicidality. Retrospectively, her scores on the BFCRS were high on screening items 1 to 14, which measure presence or absence and severity of symptoms.

The best option was to admit Ms. A to an inpatient psychiatric facility after she is cleared medically with outpatient services to follow up.

How would you treat Ms. A’s symptoms?

a) aggressively treat catatonia

b) address her eating disorder

c) work to resolve her depression

The authors’ observations

The challenge was to choose the psychotropic medication that would target her depression, obsessive, rigid thoughts, and catatonia. Administering an antidepressant with an antipsychotic would have relieved her depressive and obsessive symptoms but would not have improved her catatonia. The psychosomatic medicine team recommended starting a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a benzodiazepine to target both the depression and the catatonic symptoms. Ms. A received sertraline, 12.5 mg/d, which was increased to 25 mg/d on the third day. IV lorazepam, 1 mg, 3 times a day, was recommended but the pediatric team prescribed an oral formulation. The hospital’s eating disorder protocol was instituted on the day of admission.

Treatment options for catatonia

Benzodiazepines are the first line of treatment for catatonia and other neuroleptics, specifically antipsychotics, have been considered dangerous.10 Benzodiazepine-resistant catatonia, which is sometimes seen in patients with autism, might respond to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT),11 although in some states it cannot be administered to children age <18.12 Benzodiazepines have shown dramatic improvement within hours, as has ECT.8,13 Additionally, if patients do not respond to a benzodiazepine or ECT, consider other options such as zolpidem, olanzapine,14 or sensory integration system (in adolescents with autism).15

Ms. A did not need ECT or an alternative treatment because she responded well to 3 doses of oral lorazepam. Her amotivation, negativism, and rigidity with prolonged posturing improved. Her psychomotor retardation improved overall, although she reported some dizziness and had some postural hypotension, which was attributed to her eating issues and dehydration.

OUTCOME Feeling motivated

Ms. A is transferred to psychiatric inpatient unit. She tolerates sertraline, which is titrated to 50 mg/d. She is placed on the hospital’s standard eating disorder protocol. She continues to eat well with adequate intake of solids and liquid and exhibits only some anxiety associated with meals. During the course of hospitalization, she attends group therapy and her catatonic symptoms completely resolve. She says she thinks that her thoughts are improving and that she is not longer feeling confused. She reports being motivated to continue to improve her eating disorder symptoms.

The treatment team holds a family session during which family dynamic issues that are stressful to Ms. A are discussed, such as some conflict with her parents as well as some negative interactions between Ms. A and her father. Repeat comprehensive metabolic panel on admission to the inpatient psychiatric hospital reveals persistent elevation of AST at 92 U/L and ALT at 143 U/L. Ms. A is discharged home with follow-up with a psychiatrist and a therapist. The treatment team also recommends that she follow up in a program that specializes in eating disorders.

4-month follow-up. Ms. A returns to inpatient psychiatric hospital after overdose of sertraline and aripiprazole, which were started by an outpatient psychiatrist. She reports severe depressive symptoms because of school stressors. She denies any problems eating and did not show any symptoms of catatonia. In her chart, there is a mention of “cloudy thoughts” and quietness. At this admission, her ALT is 17 U/L and AST is 19 U/L. Sertraline is increased to 150 mg/d and aripiprazole is reduced to 2 mg/d and then later increased to 5 mg/d, after which she is discharged home with an outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

1-year follow-up. Ms. A has been following up with an outpatient psychiatrist and is receiving sertraline, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 2.5 mg/d, and extended-release methylphenidate, 36 mg/d, along with L-methylfolate, multivitamins, and omega-3 fish oil as adjuvants for her depressive symptoms. Ms. A does not show symptoms of an eating disorder or catatonia, and her depression and psychomotor activity have improved, with better overall functionality, after adding the stimulant and adjunctives to the antidepressant.

The authors’ observations

The importance of including catatonia NOS with its various specifiers, such as medical, metabolic, toxic, affective, etc., has been discussed.16,17 In Ms. A’s case, instead of treating the specific symptoms—affective or eating disorder or obsessive quality of thought content, mimicking psychotic-like symptoms—addressing the catatonia initially had a better outcome. More studies related to chronic and acute catatonia in adolescents are needed because of the risk of increased morbidity and premature death.18 Early recognition of catatonia is needed19 because it often is underdiagnosed.20

Eating disorders often become worse over the first 5 years, and close monitoring and assessment is needed for adolescents.21 Also, prodromal psychotic symptoms require follow-up because techniques for early detection and intervention for children and adolescents are still in their infancy.22

Bottom Line

Catatonia in adolescents should be addressed early, when it is treatable and the outcome is favorable. It is important to recognize catatonia in an emergency department or inpatient medical unit setting in a hospital because it is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. The presentation of catatonia is similar in adolescents and adults. Benzodiazepines are first-line treatment for catatonia; consider electroconvulsive therapy if patients do not respond to drug therapy.

Related Resources

• Roberto AJ, Pinnaka S, Mohan A, et al. Adolescent catatonia successfully treated with lorazepam and aripiprazole. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2014;2014:309517. doi: 10.1155/2014/309517.

• Raffin M, Zugaj-Bensaou L, Bodeau N, et al. Treatment use in a prospective naturalistic cohort of children and adolescents with catatonia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(4):441-449.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Minocycline • Minocin

L-methylfolate • Deplin Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Lorazepam • Ativan Sertraline • Zoloft

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta Zolpidem • Ambien, Intermezzo

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Dhossche D, Wilson C, Wachtel LE. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence: implications for the DSM-5. Primary Psychiatry. http://primarypsychiatry.com/catatonia-in-childhood-and-adolescence-implications-for-the-dsm-5. Published May 21, 2013. Accessed July 2, 2015.

2. Lahutte B, Cornic F, Bonnot O, et al. Multidisciplinary approach of organic catatonia in children and adolescents may improve treatment decision making. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):1393-1398.

3. Brake JA, Abidi S. A case of adolescent catatonia. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):138-140.

4. Consoli A, Raffin M, Laurent C, et al. Medical and developmental risk factors of catatonia in children and adolescents: a prospective case-control study. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):151-158.

5. Zaider TI, Johnson JG, Cockell SJ. Psychiatric comorbidity associated with eating disorder symptomatology among adolescents in the community. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(1):58-67.

6. Forsén Mantilla E, Bergsten K, Birgegård A. Self-image and eating disorder symptoms in normal and clinical adolescents. Eat Behav. 2014;15(1):125-131.

7. Bonnot O, Tanguy ML, Consoli A, et al. Does catatonia influence the phenomenology of childhood onset schizophrenia beyond motor symptoms? Psychiatry Res. 2008;158(3):356-362.

8. Singh LK, Praharaj SK. Immediate response to lorazepam in a patient with 17 years of chronic catatonia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(3):E47-E48.

9. Sienaert P, Rooseleer J, De Fruyt J. Measuring catatonia: a systematic review of rating scales. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):1-9.

10. Cottencin O, Warembourg F, de Chouly de Lenclave MB, et al. Catatonia and consultation-liaison psychiatry study of 12 cases. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(6):1170-1176.

11. Wachtel LE, Hermida A, Dhossche DM. Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in autistic catatonia: a case series review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):581-587.

12. Wachtel LE, Dhossche DM, Kellner CH. When is electroconvulsive therapy appropriate for children and adolescents? Med Hypotheses. 2011;76(3):395-399.

13. Takaoka K, Takata T. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57(2):129-137.

14. Ceylan MF, Kul M, Kultur SE, et al. Major depression with catatonic features in a child remitted with olanzapine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(3):225-227.

15. Consoli A, Gheorghiev C, Jutard C, et al. Lorazepam, fluoxetine and packing therapy in an adolescent with pervasive developmental disorder and catatonia. J Physiol Paris. 2010;104(6):309-314.

16. Dhossche D, Cohen D, Ghaziuddin N, et al. The study of pediatric catatonia supports a home of its own for catatonia in DSM-5. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75(6):558-560.

17. Taylor MA, Fink M. Catatonia in psychiatric classification: a home of its own. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1233-1241.

18. Cornic F, Consoli A, Tanguy ML, et al. Association of adolescent catatonia with increased mortality and morbidity: evidence from a prospective follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):233-240.

19. Quigley J, Lommel KM, Coffey B. Catatonia in an adolescent with Asperger’s disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):93-96.

20. Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):33-38.

21. Ackard DM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Stability of eating disorder diagnostic classifications in adolescents: five-year longitudinal findings from a population-based study. Eat Disord. 2011;19(4):308-322.

22. Schimmelmann BG, Schultze-Lutter F. Early detection and intervention of psychosis in children and adolescents: urgent need for studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(5):239-241.

1. Dhossche D, Wilson C, Wachtel LE. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence: implications for the DSM-5. Primary Psychiatry. http://primarypsychiatry.com/catatonia-in-childhood-and-adolescence-implications-for-the-dsm-5. Published May 21, 2013. Accessed July 2, 2015.

2. Lahutte B, Cornic F, Bonnot O, et al. Multidisciplinary approach of organic catatonia in children and adolescents may improve treatment decision making. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):1393-1398.

3. Brake JA, Abidi S. A case of adolescent catatonia. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):138-140.

4. Consoli A, Raffin M, Laurent C, et al. Medical and developmental risk factors of catatonia in children and adolescents: a prospective case-control study. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):151-158.

5. Zaider TI, Johnson JG, Cockell SJ. Psychiatric comorbidity associated with eating disorder symptomatology among adolescents in the community. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(1):58-67.

6. Forsén Mantilla E, Bergsten K, Birgegård A. Self-image and eating disorder symptoms in normal and clinical adolescents. Eat Behav. 2014;15(1):125-131.

7. Bonnot O, Tanguy ML, Consoli A, et al. Does catatonia influence the phenomenology of childhood onset schizophrenia beyond motor symptoms? Psychiatry Res. 2008;158(3):356-362.

8. Singh LK, Praharaj SK. Immediate response to lorazepam in a patient with 17 years of chronic catatonia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(3):E47-E48.

9. Sienaert P, Rooseleer J, De Fruyt J. Measuring catatonia: a systematic review of rating scales. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):1-9.

10. Cottencin O, Warembourg F, de Chouly de Lenclave MB, et al. Catatonia and consultation-liaison psychiatry study of 12 cases. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(6):1170-1176.

11. Wachtel LE, Hermida A, Dhossche DM. Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in autistic catatonia: a case series review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):581-587.

12. Wachtel LE, Dhossche DM, Kellner CH. When is electroconvulsive therapy appropriate for children and adolescents? Med Hypotheses. 2011;76(3):395-399.

13. Takaoka K, Takata T. Catatonia in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57(2):129-137.

14. Ceylan MF, Kul M, Kultur SE, et al. Major depression with catatonic features in a child remitted with olanzapine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(3):225-227.

15. Consoli A, Gheorghiev C, Jutard C, et al. Lorazepam, fluoxetine and packing therapy in an adolescent with pervasive developmental disorder and catatonia. J Physiol Paris. 2010;104(6):309-314.

16. Dhossche D, Cohen D, Ghaziuddin N, et al. The study of pediatric catatonia supports a home of its own for catatonia in DSM-5. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75(6):558-560.

17. Taylor MA, Fink M. Catatonia in psychiatric classification: a home of its own. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1233-1241.

18. Cornic F, Consoli A, Tanguy ML, et al. Association of adolescent catatonia with increased mortality and morbidity: evidence from a prospective follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):233-240.

19. Quigley J, Lommel KM, Coffey B. Catatonia in an adolescent with Asperger’s disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):93-96.

20. Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):33-38.

21. Ackard DM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Stability of eating disorder diagnostic classifications in adolescents: five-year longitudinal findings from a population-based study. Eat Disord. 2011;19(4):308-322.

22. Schimmelmann BG, Schultze-Lutter F. Early detection and intervention of psychosis in children and adolescents: urgent need for studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(5):239-241.