User login

Use of Cross-Leg Flap for Wound Complications Resulting From Open Pilon Fracture

Soft-tissue complications are a known problem in the treatment of pilon fractures of the distal end of the tibia. These fractures typically occur as the result of a high-energy mechanism, and axial load and shear forces often lead to a severe soft-tissue injury. In many cases, these injuries may require additional procedures to provide adequate soft-tissue coverage. These procedures can include use of either a rotational muscle flap or a free flap transfer. In some cases, however, these flaps are not possible secondary to vascular compromise.

In this article, we report the case of a pilon fracture combined with severe soft-tissue injury and vascular compromise of the leg. A cross-leg fasciocutaneous flap was performed as a salvage procedure for coverage of the soft-tissue defect. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 23-year-old man sustained a left grade III open pilon fracture after a fall off a cherry picker. He was initially treated with irrigation and débridement of the open anteromedial wound, wound closure, application of external fixation, and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the concomitant comminuted fibular fracture. Operative fixation of the pilon was performed 3 weeks after injury, once skin and soft tissues were in acceptable condition (Figure 1). Skin closure was performed with 2-0 Vicryl sutures (Ethicon, Inc, Somerville, New Jersey) followed by 3-0 nylon skin sutures and No. 2 nylon retention sutures to reduce tension at the incision.

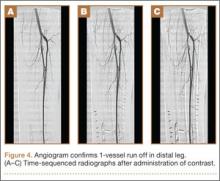

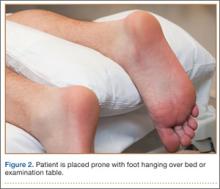

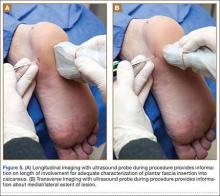

On postoperative day 17, the patient was found to have skin necrosis with exposed hardware over the medial laceration that had resulted from the open fracture (Figure 2). The wound measured 7×6 cm. The plastic surgery team was consulted, and a soft-tissue flap was recommended. Preoperative computed tomography angiogram (Figure 3) revealed 1 vessel runoff in the leg, constituting the peroneal artery, and a conventional angiogram confirmed this finding (Figure 4). Despite these findings, the patient was taken to the operating room 4 weeks after initial injury to try to find a vessel compatible with anastomosis. Intraoperative wound exploration confirmed no patent blood supply for local soft-tissue flap coverage. Therefore, the wound was irrigated and débrided, and a vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) dressing was applied despite exposed hardware and bone. A decision was then made to attempt a cross-leg flap as a salvage procedure, and VAC dressing therapy was continued for several weeks to prepare the recipient site (Figure 5).

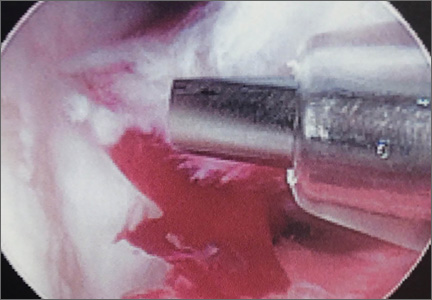

Seven weeks after injury, the patient was taken to the operating room by the orthopedic surgery and plastic surgery teams. After débridement, a fasciocutaneous flap was raised from the middle third of the contralateral leg (Figure 6) based on a posterior tibial artery perforator. The flap, which measured 7×7 cm (sufficient to cover the defect), was raised from lateral to medial from the posterior aspect of the leg with the pedicle located on the medial aspect of the right leg. Flap placement was facilitated by flexing the left knee to 80°. The flap was sutured into place with 4-0 Vicryl deep sutures followed by 4-0 nylon and superficial sutures in an interrupted fashion (Figure 7). Rigid external fixation was then applied to both extremities, bridging them together in optimal position (Figure 8). This construct included 2 short bars that would elevate the patient’s heels off the bed to reduce the chance of heel decubiti. Although including the feet in the external fixator construct may help prevent equinus contracture, we splinted the ankles in neutral position immediately after surgery so that we could begin early range-of-motion (ROM) exercises of the ankles to prevent stiffness. Ankle ROM exercises were started once the flap incorporated, 3 weeks after placement of the external fixator. Lacking medical insurance coverage, the patient could not be admitted to a rehabilitation facility or receive home care. He lived independently and had no help at home, so he had to remain hospitalized after placement of the external fixator. While hospitalized, the surgical site was treated with frequent dressing changes, including use of bacitracin and nonadherent dressing.

After flap coverage and 4 weeks of bed rest, a base clamping test confirmed the flap was incorporated into the recipient bed. The patient was then returned to the operating room for removal of the external fixator and skin grafting of the donor site. After surgery, he was started on physical therapy, including exercises for bilateral hip, knee, and ankle ROM and strengthening of the lower extremities. Four months after initial injury, the fracture was healed, based on bone consolidation, seen on radiographs, that is consistent with other pilon fractures treated at our institution. Six months after external fixator removal, the patient was able to ambulate independently with minimal discomfort (Figure 9). Passive and active ankle ROM was 20° of dorsiflexion and 25° of plantarflexion, compared with 25° of dorsiflexion and 45° of plantarflexion on the contralateral extremity. Subtalar motion had some stiffness with a 10° arc, compared with a 25° arc on the contralateral extremity. On simple manual testing, the patient had 5/5 motor strength with dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, inversion, and eversion. He returned to full duty as a landscaper about 1 year after initial injury and had no recurrence of wound complications or infection.

Discussion

Fractures of the distal tibia are commonly known as pilon or plafond fractures. They represent up to 10% of all tibial fractures. The injury consists of an intra-articular fracture of the tibiotalar joint with varying degrees of proximal extension into the tibial metaphysis. The etiology is an axial load on the tibia with or without a rotational force.1 Treatment is challenging. The literature includes many reports of wound and soft-tissue complications after ORIF. In 1969, Rüedi and Allgöwer2 published recommendations that have become the standard for treatment of pilon fractures. Twelve percent of the 84 fractures included in their study were associated with wound complications. In 2004, Sirkin and colleagues3 suggested that wound problems associated with ORIF of pilon fractures may be caused by attempts at immediate fixation through swollen soft tissue. They postulated that staging the procedure and waiting for decreased soft-tissue swelling may reduce the incidence of wound complications. In their series, only 2.9% of closed pilon fractures and only 9.1% of open fractures had any wound complications, and none of their patients required skin grafts, rotation flaps, or free tissue transfers.

However, soft-tissue complications still remain a significant threat in the treatment of pilon fracture, and cases that require additional procedures for soft-tissue coverage are common. In some cases, wound necrosis may lead to below-knee amputation.4 There are several coverage options, including local rotational flaps using the soleus muscle5,6 as well as free flaps using the latissimus dorsi, gracilis, or rectus abdominis muscles.7 These options require a sufficient blood supply to the region.

Many high-energy pilon fractures may be associated with vascular injury, and therefore flap survival may be compromised. We have reported such a case in the present article. Our patient’s preoperative angiogram indicated he had 1-vessel runoff to the distal leg—a situation incompatible with free tissue transfer. It is not clear whether this finding is secondary to trauma to the leg or is caused by an anatomical anomaly. Nevertheless, the poor vascularity posed a challenge to providing soft-tissue coverage. Cross-finger8 and cross-foot9 flaps have been described in upper and lower extremity injuries. In 2006, Zhao and colleagues10 reported on 5 patients with tibia and/or hardware exposure after operative fixation of tibia fractures. These patients had poor local soft tissue around the wound and therefore underwent cross-leg flap for coverage. It is not clear where the soft-tissue defects were located and whether any studies were performed to assess the local blood flow.

From our patient’s case, we learned that multiple factors should be considered when assessing such high-energy injuries. First, respecting the soft tissues is of paramount importance. Our initial management on presentation consisted of irrigation and débridement of the wound, fixation of the fibula, and application of an external fixator to allow for soft-tissue healing before definitive fixation of the pilon. Although ultimately the patient required soft-tissue coverage, soft-tissue healing and viability are important in preventing unnecessary soft-tissue procedures, and therefore we would not have handled our initial treatment differently.

Patient selection is also important. The ideal candidate for a cross-leg flap is a young, healthy person who is compliant and has a strong support system to help with activities of daily living. Unfortunately, because of financial issues and lack of home support, our patient remained hospitalized during his treatment course. For a patient who has support, it is possible to be discharged either home or to a rehabilitation facility once flap viability has been confirmed after surgery.

Another consideration is type of immobilization. Immobilization options include casting, use of Kirschner wires (K-wires), and use of rigid external fixation. For cross-leg flaps, external fixation is superior to casting and K-wires, as it provides a more rigid construct and easier access to the flap for serial evaluation. Further, it is easier for the patient to maintain personal hygiene, and it can provide heel rises to avoid pressure ulcers.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, there have been no reports of using a cross-leg flap for wound complications in high-energy pilon fractures. As already mentioned, many of these fractures may be associated with severe soft-tissue injury and may need flap coverage. A cross-leg flap with external fixation of both legs provides a limb salvage option with satisfactory patient outcomes.

1. McCann PA, Jackson M, Mitchell ST, Atkins RM. Complications of definitive open reduction and internal fixation of pilon fractures of the distal tibia. Int Orthop. 2011;35(3):413-418.

2. Rüedi TP, Allgöwer M. Fractures of the lower end of the tibia into the ankle joint. Injury. 1969;1:92-99.

3. Sirkin M, Sanders R, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D Jr. A staged protocol for soft tissue management in the treatment of complex pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(8 suppl):S32-S38.

4. Boraiah S, Kemp TJ, Erwteman A, Lucas PA, Asprinio DE. Outcome following open reduction and internal fixation of open pilon fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(2):346-352.

5. Cheng C, Li X, Abudu S. Repairing postoperative soft tissue defects of tibia and ankle open fractures with muscle flap pedicled with medial half of soleus [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2009;23(12):1440-1442.

6. Yunus A, Yusuf A, Chen G. Repair of soft tissue defect by reverse soleus muscle flap after pilon fracture fixation [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2007;21(9):925-927.

7. Conroy J, Agarwal M, Giannoudis PV, Matthews SJ. Early internal fixation and soft tissue cover of severe open tibial pilon fractures. Int Orthop. 2003;27(6):343-347.

8. Megerle K, Palm-Bröking K, Germann G. The cross-finger flap [in German]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2008;20(2):97-102.

9. Largey A, Faline A, Hebrard W, Hamoui M, Canovas F. Management of massive traumatic compound defects of the foot. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(4):301-304.

10. Zhao L, Wan L, Wang S. Clinical studies on maintenance of cross-leg position through internal fixation with Kirschner wire after cross-leg flap procedure. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006;20(12):1211-1213.

Soft-tissue complications are a known problem in the treatment of pilon fractures of the distal end of the tibia. These fractures typically occur as the result of a high-energy mechanism, and axial load and shear forces often lead to a severe soft-tissue injury. In many cases, these injuries may require additional procedures to provide adequate soft-tissue coverage. These procedures can include use of either a rotational muscle flap or a free flap transfer. In some cases, however, these flaps are not possible secondary to vascular compromise.

In this article, we report the case of a pilon fracture combined with severe soft-tissue injury and vascular compromise of the leg. A cross-leg fasciocutaneous flap was performed as a salvage procedure for coverage of the soft-tissue defect. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 23-year-old man sustained a left grade III open pilon fracture after a fall off a cherry picker. He was initially treated with irrigation and débridement of the open anteromedial wound, wound closure, application of external fixation, and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the concomitant comminuted fibular fracture. Operative fixation of the pilon was performed 3 weeks after injury, once skin and soft tissues were in acceptable condition (Figure 1). Skin closure was performed with 2-0 Vicryl sutures (Ethicon, Inc, Somerville, New Jersey) followed by 3-0 nylon skin sutures and No. 2 nylon retention sutures to reduce tension at the incision.

On postoperative day 17, the patient was found to have skin necrosis with exposed hardware over the medial laceration that had resulted from the open fracture (Figure 2). The wound measured 7×6 cm. The plastic surgery team was consulted, and a soft-tissue flap was recommended. Preoperative computed tomography angiogram (Figure 3) revealed 1 vessel runoff in the leg, constituting the peroneal artery, and a conventional angiogram confirmed this finding (Figure 4). Despite these findings, the patient was taken to the operating room 4 weeks after initial injury to try to find a vessel compatible with anastomosis. Intraoperative wound exploration confirmed no patent blood supply for local soft-tissue flap coverage. Therefore, the wound was irrigated and débrided, and a vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) dressing was applied despite exposed hardware and bone. A decision was then made to attempt a cross-leg flap as a salvage procedure, and VAC dressing therapy was continued for several weeks to prepare the recipient site (Figure 5).

Seven weeks after injury, the patient was taken to the operating room by the orthopedic surgery and plastic surgery teams. After débridement, a fasciocutaneous flap was raised from the middle third of the contralateral leg (Figure 6) based on a posterior tibial artery perforator. The flap, which measured 7×7 cm (sufficient to cover the defect), was raised from lateral to medial from the posterior aspect of the leg with the pedicle located on the medial aspect of the right leg. Flap placement was facilitated by flexing the left knee to 80°. The flap was sutured into place with 4-0 Vicryl deep sutures followed by 4-0 nylon and superficial sutures in an interrupted fashion (Figure 7). Rigid external fixation was then applied to both extremities, bridging them together in optimal position (Figure 8). This construct included 2 short bars that would elevate the patient’s heels off the bed to reduce the chance of heel decubiti. Although including the feet in the external fixator construct may help prevent equinus contracture, we splinted the ankles in neutral position immediately after surgery so that we could begin early range-of-motion (ROM) exercises of the ankles to prevent stiffness. Ankle ROM exercises were started once the flap incorporated, 3 weeks after placement of the external fixator. Lacking medical insurance coverage, the patient could not be admitted to a rehabilitation facility or receive home care. He lived independently and had no help at home, so he had to remain hospitalized after placement of the external fixator. While hospitalized, the surgical site was treated with frequent dressing changes, including use of bacitracin and nonadherent dressing.

After flap coverage and 4 weeks of bed rest, a base clamping test confirmed the flap was incorporated into the recipient bed. The patient was then returned to the operating room for removal of the external fixator and skin grafting of the donor site. After surgery, he was started on physical therapy, including exercises for bilateral hip, knee, and ankle ROM and strengthening of the lower extremities. Four months after initial injury, the fracture was healed, based on bone consolidation, seen on radiographs, that is consistent with other pilon fractures treated at our institution. Six months after external fixator removal, the patient was able to ambulate independently with minimal discomfort (Figure 9). Passive and active ankle ROM was 20° of dorsiflexion and 25° of plantarflexion, compared with 25° of dorsiflexion and 45° of plantarflexion on the contralateral extremity. Subtalar motion had some stiffness with a 10° arc, compared with a 25° arc on the contralateral extremity. On simple manual testing, the patient had 5/5 motor strength with dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, inversion, and eversion. He returned to full duty as a landscaper about 1 year after initial injury and had no recurrence of wound complications or infection.

Discussion

Fractures of the distal tibia are commonly known as pilon or plafond fractures. They represent up to 10% of all tibial fractures. The injury consists of an intra-articular fracture of the tibiotalar joint with varying degrees of proximal extension into the tibial metaphysis. The etiology is an axial load on the tibia with or without a rotational force.1 Treatment is challenging. The literature includes many reports of wound and soft-tissue complications after ORIF. In 1969, Rüedi and Allgöwer2 published recommendations that have become the standard for treatment of pilon fractures. Twelve percent of the 84 fractures included in their study were associated with wound complications. In 2004, Sirkin and colleagues3 suggested that wound problems associated with ORIF of pilon fractures may be caused by attempts at immediate fixation through swollen soft tissue. They postulated that staging the procedure and waiting for decreased soft-tissue swelling may reduce the incidence of wound complications. In their series, only 2.9% of closed pilon fractures and only 9.1% of open fractures had any wound complications, and none of their patients required skin grafts, rotation flaps, or free tissue transfers.

However, soft-tissue complications still remain a significant threat in the treatment of pilon fracture, and cases that require additional procedures for soft-tissue coverage are common. In some cases, wound necrosis may lead to below-knee amputation.4 There are several coverage options, including local rotational flaps using the soleus muscle5,6 as well as free flaps using the latissimus dorsi, gracilis, or rectus abdominis muscles.7 These options require a sufficient blood supply to the region.

Many high-energy pilon fractures may be associated with vascular injury, and therefore flap survival may be compromised. We have reported such a case in the present article. Our patient’s preoperative angiogram indicated he had 1-vessel runoff to the distal leg—a situation incompatible with free tissue transfer. It is not clear whether this finding is secondary to trauma to the leg or is caused by an anatomical anomaly. Nevertheless, the poor vascularity posed a challenge to providing soft-tissue coverage. Cross-finger8 and cross-foot9 flaps have been described in upper and lower extremity injuries. In 2006, Zhao and colleagues10 reported on 5 patients with tibia and/or hardware exposure after operative fixation of tibia fractures. These patients had poor local soft tissue around the wound and therefore underwent cross-leg flap for coverage. It is not clear where the soft-tissue defects were located and whether any studies were performed to assess the local blood flow.

From our patient’s case, we learned that multiple factors should be considered when assessing such high-energy injuries. First, respecting the soft tissues is of paramount importance. Our initial management on presentation consisted of irrigation and débridement of the wound, fixation of the fibula, and application of an external fixator to allow for soft-tissue healing before definitive fixation of the pilon. Although ultimately the patient required soft-tissue coverage, soft-tissue healing and viability are important in preventing unnecessary soft-tissue procedures, and therefore we would not have handled our initial treatment differently.

Patient selection is also important. The ideal candidate for a cross-leg flap is a young, healthy person who is compliant and has a strong support system to help with activities of daily living. Unfortunately, because of financial issues and lack of home support, our patient remained hospitalized during his treatment course. For a patient who has support, it is possible to be discharged either home or to a rehabilitation facility once flap viability has been confirmed after surgery.

Another consideration is type of immobilization. Immobilization options include casting, use of Kirschner wires (K-wires), and use of rigid external fixation. For cross-leg flaps, external fixation is superior to casting and K-wires, as it provides a more rigid construct and easier access to the flap for serial evaluation. Further, it is easier for the patient to maintain personal hygiene, and it can provide heel rises to avoid pressure ulcers.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, there have been no reports of using a cross-leg flap for wound complications in high-energy pilon fractures. As already mentioned, many of these fractures may be associated with severe soft-tissue injury and may need flap coverage. A cross-leg flap with external fixation of both legs provides a limb salvage option with satisfactory patient outcomes.

Soft-tissue complications are a known problem in the treatment of pilon fractures of the distal end of the tibia. These fractures typically occur as the result of a high-energy mechanism, and axial load and shear forces often lead to a severe soft-tissue injury. In many cases, these injuries may require additional procedures to provide adequate soft-tissue coverage. These procedures can include use of either a rotational muscle flap or a free flap transfer. In some cases, however, these flaps are not possible secondary to vascular compromise.

In this article, we report the case of a pilon fracture combined with severe soft-tissue injury and vascular compromise of the leg. A cross-leg fasciocutaneous flap was performed as a salvage procedure for coverage of the soft-tissue defect. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 23-year-old man sustained a left grade III open pilon fracture after a fall off a cherry picker. He was initially treated with irrigation and débridement of the open anteromedial wound, wound closure, application of external fixation, and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the concomitant comminuted fibular fracture. Operative fixation of the pilon was performed 3 weeks after injury, once skin and soft tissues were in acceptable condition (Figure 1). Skin closure was performed with 2-0 Vicryl sutures (Ethicon, Inc, Somerville, New Jersey) followed by 3-0 nylon skin sutures and No. 2 nylon retention sutures to reduce tension at the incision.

On postoperative day 17, the patient was found to have skin necrosis with exposed hardware over the medial laceration that had resulted from the open fracture (Figure 2). The wound measured 7×6 cm. The plastic surgery team was consulted, and a soft-tissue flap was recommended. Preoperative computed tomography angiogram (Figure 3) revealed 1 vessel runoff in the leg, constituting the peroneal artery, and a conventional angiogram confirmed this finding (Figure 4). Despite these findings, the patient was taken to the operating room 4 weeks after initial injury to try to find a vessel compatible with anastomosis. Intraoperative wound exploration confirmed no patent blood supply for local soft-tissue flap coverage. Therefore, the wound was irrigated and débrided, and a vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) dressing was applied despite exposed hardware and bone. A decision was then made to attempt a cross-leg flap as a salvage procedure, and VAC dressing therapy was continued for several weeks to prepare the recipient site (Figure 5).

Seven weeks after injury, the patient was taken to the operating room by the orthopedic surgery and plastic surgery teams. After débridement, a fasciocutaneous flap was raised from the middle third of the contralateral leg (Figure 6) based on a posterior tibial artery perforator. The flap, which measured 7×7 cm (sufficient to cover the defect), was raised from lateral to medial from the posterior aspect of the leg with the pedicle located on the medial aspect of the right leg. Flap placement was facilitated by flexing the left knee to 80°. The flap was sutured into place with 4-0 Vicryl deep sutures followed by 4-0 nylon and superficial sutures in an interrupted fashion (Figure 7). Rigid external fixation was then applied to both extremities, bridging them together in optimal position (Figure 8). This construct included 2 short bars that would elevate the patient’s heels off the bed to reduce the chance of heel decubiti. Although including the feet in the external fixator construct may help prevent equinus contracture, we splinted the ankles in neutral position immediately after surgery so that we could begin early range-of-motion (ROM) exercises of the ankles to prevent stiffness. Ankle ROM exercises were started once the flap incorporated, 3 weeks after placement of the external fixator. Lacking medical insurance coverage, the patient could not be admitted to a rehabilitation facility or receive home care. He lived independently and had no help at home, so he had to remain hospitalized after placement of the external fixator. While hospitalized, the surgical site was treated with frequent dressing changes, including use of bacitracin and nonadherent dressing.

After flap coverage and 4 weeks of bed rest, a base clamping test confirmed the flap was incorporated into the recipient bed. The patient was then returned to the operating room for removal of the external fixator and skin grafting of the donor site. After surgery, he was started on physical therapy, including exercises for bilateral hip, knee, and ankle ROM and strengthening of the lower extremities. Four months after initial injury, the fracture was healed, based on bone consolidation, seen on radiographs, that is consistent with other pilon fractures treated at our institution. Six months after external fixator removal, the patient was able to ambulate independently with minimal discomfort (Figure 9). Passive and active ankle ROM was 20° of dorsiflexion and 25° of plantarflexion, compared with 25° of dorsiflexion and 45° of plantarflexion on the contralateral extremity. Subtalar motion had some stiffness with a 10° arc, compared with a 25° arc on the contralateral extremity. On simple manual testing, the patient had 5/5 motor strength with dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, inversion, and eversion. He returned to full duty as a landscaper about 1 year after initial injury and had no recurrence of wound complications or infection.

Discussion

Fractures of the distal tibia are commonly known as pilon or plafond fractures. They represent up to 10% of all tibial fractures. The injury consists of an intra-articular fracture of the tibiotalar joint with varying degrees of proximal extension into the tibial metaphysis. The etiology is an axial load on the tibia with or without a rotational force.1 Treatment is challenging. The literature includes many reports of wound and soft-tissue complications after ORIF. In 1969, Rüedi and Allgöwer2 published recommendations that have become the standard for treatment of pilon fractures. Twelve percent of the 84 fractures included in their study were associated with wound complications. In 2004, Sirkin and colleagues3 suggested that wound problems associated with ORIF of pilon fractures may be caused by attempts at immediate fixation through swollen soft tissue. They postulated that staging the procedure and waiting for decreased soft-tissue swelling may reduce the incidence of wound complications. In their series, only 2.9% of closed pilon fractures and only 9.1% of open fractures had any wound complications, and none of their patients required skin grafts, rotation flaps, or free tissue transfers.

However, soft-tissue complications still remain a significant threat in the treatment of pilon fracture, and cases that require additional procedures for soft-tissue coverage are common. In some cases, wound necrosis may lead to below-knee amputation.4 There are several coverage options, including local rotational flaps using the soleus muscle5,6 as well as free flaps using the latissimus dorsi, gracilis, or rectus abdominis muscles.7 These options require a sufficient blood supply to the region.

Many high-energy pilon fractures may be associated with vascular injury, and therefore flap survival may be compromised. We have reported such a case in the present article. Our patient’s preoperative angiogram indicated he had 1-vessel runoff to the distal leg—a situation incompatible with free tissue transfer. It is not clear whether this finding is secondary to trauma to the leg or is caused by an anatomical anomaly. Nevertheless, the poor vascularity posed a challenge to providing soft-tissue coverage. Cross-finger8 and cross-foot9 flaps have been described in upper and lower extremity injuries. In 2006, Zhao and colleagues10 reported on 5 patients with tibia and/or hardware exposure after operative fixation of tibia fractures. These patients had poor local soft tissue around the wound and therefore underwent cross-leg flap for coverage. It is not clear where the soft-tissue defects were located and whether any studies were performed to assess the local blood flow.

From our patient’s case, we learned that multiple factors should be considered when assessing such high-energy injuries. First, respecting the soft tissues is of paramount importance. Our initial management on presentation consisted of irrigation and débridement of the wound, fixation of the fibula, and application of an external fixator to allow for soft-tissue healing before definitive fixation of the pilon. Although ultimately the patient required soft-tissue coverage, soft-tissue healing and viability are important in preventing unnecessary soft-tissue procedures, and therefore we would not have handled our initial treatment differently.

Patient selection is also important. The ideal candidate for a cross-leg flap is a young, healthy person who is compliant and has a strong support system to help with activities of daily living. Unfortunately, because of financial issues and lack of home support, our patient remained hospitalized during his treatment course. For a patient who has support, it is possible to be discharged either home or to a rehabilitation facility once flap viability has been confirmed after surgery.

Another consideration is type of immobilization. Immobilization options include casting, use of Kirschner wires (K-wires), and use of rigid external fixation. For cross-leg flaps, external fixation is superior to casting and K-wires, as it provides a more rigid construct and easier access to the flap for serial evaluation. Further, it is easier for the patient to maintain personal hygiene, and it can provide heel rises to avoid pressure ulcers.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, there have been no reports of using a cross-leg flap for wound complications in high-energy pilon fractures. As already mentioned, many of these fractures may be associated with severe soft-tissue injury and may need flap coverage. A cross-leg flap with external fixation of both legs provides a limb salvage option with satisfactory patient outcomes.

1. McCann PA, Jackson M, Mitchell ST, Atkins RM. Complications of definitive open reduction and internal fixation of pilon fractures of the distal tibia. Int Orthop. 2011;35(3):413-418.

2. Rüedi TP, Allgöwer M. Fractures of the lower end of the tibia into the ankle joint. Injury. 1969;1:92-99.

3. Sirkin M, Sanders R, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D Jr. A staged protocol for soft tissue management in the treatment of complex pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(8 suppl):S32-S38.

4. Boraiah S, Kemp TJ, Erwteman A, Lucas PA, Asprinio DE. Outcome following open reduction and internal fixation of open pilon fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(2):346-352.

5. Cheng C, Li X, Abudu S. Repairing postoperative soft tissue defects of tibia and ankle open fractures with muscle flap pedicled with medial half of soleus [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2009;23(12):1440-1442.

6. Yunus A, Yusuf A, Chen G. Repair of soft tissue defect by reverse soleus muscle flap after pilon fracture fixation [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2007;21(9):925-927.

7. Conroy J, Agarwal M, Giannoudis PV, Matthews SJ. Early internal fixation and soft tissue cover of severe open tibial pilon fractures. Int Orthop. 2003;27(6):343-347.

8. Megerle K, Palm-Bröking K, Germann G. The cross-finger flap [in German]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2008;20(2):97-102.

9. Largey A, Faline A, Hebrard W, Hamoui M, Canovas F. Management of massive traumatic compound defects of the foot. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(4):301-304.

10. Zhao L, Wan L, Wang S. Clinical studies on maintenance of cross-leg position through internal fixation with Kirschner wire after cross-leg flap procedure. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006;20(12):1211-1213.

1. McCann PA, Jackson M, Mitchell ST, Atkins RM. Complications of definitive open reduction and internal fixation of pilon fractures of the distal tibia. Int Orthop. 2011;35(3):413-418.

2. Rüedi TP, Allgöwer M. Fractures of the lower end of the tibia into the ankle joint. Injury. 1969;1:92-99.

3. Sirkin M, Sanders R, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D Jr. A staged protocol for soft tissue management in the treatment of complex pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(8 suppl):S32-S38.

4. Boraiah S, Kemp TJ, Erwteman A, Lucas PA, Asprinio DE. Outcome following open reduction and internal fixation of open pilon fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(2):346-352.

5. Cheng C, Li X, Abudu S. Repairing postoperative soft tissue defects of tibia and ankle open fractures with muscle flap pedicled with medial half of soleus [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2009;23(12):1440-1442.

6. Yunus A, Yusuf A, Chen G. Repair of soft tissue defect by reverse soleus muscle flap after pilon fracture fixation [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2007;21(9):925-927.

7. Conroy J, Agarwal M, Giannoudis PV, Matthews SJ. Early internal fixation and soft tissue cover of severe open tibial pilon fractures. Int Orthop. 2003;27(6):343-347.

8. Megerle K, Palm-Bröking K, Germann G. The cross-finger flap [in German]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2008;20(2):97-102.

9. Largey A, Faline A, Hebrard W, Hamoui M, Canovas F. Management of massive traumatic compound defects of the foot. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(4):301-304.

10. Zhao L, Wan L, Wang S. Clinical studies on maintenance of cross-leg position through internal fixation with Kirschner wire after cross-leg flap procedure. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006;20(12):1211-1213.

Complications of Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Ankle Fractures in Patients With Positive Urine Drug Screen

Open treatment of ankle fractures is one of the most common procedures performed by orthopedic surgeons.1 Among the younger patient population, ankle fractures represent a significant proportion of orthopedic injuries.2 The reported incidence of illicit drug and alcohol use in the urban trauma population ranges from 36% to 86%,2 and medical and anesthetic complications associated with illicit drug use have been well documented in surgical patients.2 However, patients with a recent history of drug abuse may be subject to a separate but related set of complications of open treatment of ankle fractures.

The perioperative complications associated with open treatment of ankle fractures in patients with diabetes mellitus have been well described.3-6 Similarly, previous studies have suggested that peripheral vascular disease, complicated diabetes, and smoking are risk factors for poor outcomes in patients who require open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in lower extremity trauma.7-9 However, there are few data on the complications specifically associated with illicit drug use and orthopedic surgery. Properly identifying these high-risk groups and being cognizant of commonly associated complications are likely important in ensuring proper perioperative care and may alter follow-up protocols in these patients.

We conducted a study to identify the complications associated with open treatment of ankle fractures in patients who tested positive for illicit drugs on urine drug screen (UDS). We hypothesized that patients who had a history of positive UDS and underwent ORIF of an ankle fracture would have a higher incidence of major and minor complications.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of 142 patients who underwent open treatment of an ankle fracture between 2006 and 2010. Data sources included patient demographic information, radiographs, preoperative UDS, attending surgeons’ clinical office notes, and clinical laboratory data. Our institution’s standard protocol for ankle fractures was followed for all patients in the study. All patients were evaluated by an orthopedic physician, in either the emergency department or the office, during application of a well-padded Jones splint before surgery. Oral narcotic pain medication was routinely prescribed. All patients were seen, within 10 days of injury, for surgery planning. A board-certified orthopedic surgeon surgically stabilized the ankle fractures. The postoperative treatment regimen, per protocol, included non-weight-bearing in a padded Jones splint dressing; oral narcotic pain medication; physical therapy; and routine scheduled follow-up. In open fracture cases, patients were taken urgently to the operating room for irrigation and débridement with stabilization. Which treatment would be initially used—external fixation or ORIF—was determined on a case-by-case basis.

The sample consisted of adults (age, >18 years) who had undergone definitive ORIF of a lateral malleolar, bimalleolar, or trimalleolar ankle fracture during the study period. Polytrauma patients, patients with external fixation as definitive treatment, and patients with nonoperative treatment were excluded. Before surgical management, all patients were tested for recent illicit drug use by UDS (standard protocol at our institution). UDS, measured for cocaine, marijuana, PCP (phencyclidine), opiates, and barbiturates, was obtained in the office setting or emergency department or on day of surgery. The patients were divided into 2 groups, positive and negative UDS. Patients with documented receipt of narcotic pain medication before UDS were excluded.

The outcomes identified as dependent variables included nonunion, malunion, superficial or deep infection, amputation, delay in treatment, days to healing, repeat surgery, long-term bracing, and loss to follow-up. A nonunion was defined as lasting longer than 9 months and not showing radiographic signs of progression toward healing for 3 consecutive months. These complications were identified with use of attending surgeon clinical progress notes, laboratory values, radiographic parameters, and inpatient readmissions/surgeries associated with these outcomes. Nonunion, malunion, superficial or deep infection, and amputation were then grouped as major complications and analyzed as pooled major complications.

The Fisher exact test was used to analyze categorical variables with respect to UDS. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to determine statistical significance for continuous variables. Univariate logistic regression examined both continuous and categorical variables to evaluate predictors for a selected outcome. Statistical significance was set a priori at P ≤ .05, with significant factors indicating an increase (or decrease) in the outcome variable being tested.

Results

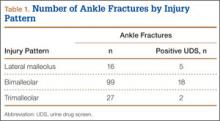

We retrospectively reviewed the cases of 142 patients. Table 1 lists the number of cases by fracture type. Bimalleolar fractures were most common, accounting for 99 (69.8%) of the 142 cases. Isolated lateral malleolar fractures accounted for 16 cases (11.2%), and trimalleolar fractures accounted for 27 cases (19%).

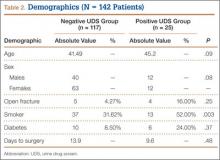

Twenty-five (18%) of the 142 patients tested positive for illicit drugs. Mean age was 45.2 years for positive UDS patients and 41.5 years for negative UDS patients. Open fracture cases represented 4.3% of negative UDS patients and 16% of positive UDS patients. Fifty-two percent of positive UDS patients and 32% of negative UDS patients were also tobacco users. These data were statistically significant (P = .003) There were no significant differences in age, sex, incidence of diabetes, incidence of open fracture, or time to surgery between the groups (Table 2).

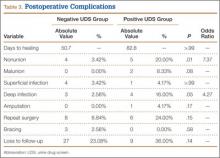

Incidence of nonunion was higher in positive UDS patients (n = 5; P = .01), as was incidence of deep infection (n = 4; P = .05) (Table 3).

Mean time to radiographic healing was 50.7 days in negative UDS patients and 82.8 days in positive UDS patients (P > .99). Incidence of nonunion was 3.5% in negative UDS patients and 20% in positive UDS patients (P = .01). There were no malunions in negative UDS patients and 2 malunions in positive UDS patients. Incidence of deep infections was 2.5% in negative UDS patients and 16% in positive UDS patients (P = .04). No significant differences were found in incidence of malunions, superficial infections, amputations, need for repeat surgery, continued bracing, or loss to follow-up.

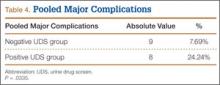

Major complications were defined as superficial or deep infections, amputations, malunions, and nonunions. The rate of major complication was significantly (P = .03) higher in positive UDS patients (24.24%) than in negative UDS patients (7.69%) (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of patients treated with ORIF for varying types of ankle fractures. Important major and minor complications were analyzed. The overall incidence of major complications in negative UDS patients was only 7.69%, consistent with previously reported results in patients with ankle fractures.6,10 However, a statistically significant (P = .03) increased incidence of major complications—an alarmingly high rate of almost 1 in 4—was found in positive UDS patients. Our results also demonstrated a significantly higher rate of nonunion and deep infection in positive UDS patients. Calculated odds ratios were 7.37 and 4.27 for nonunion and deep infection, respectively—arguably 2 of the most devastating postoperative complications in positive UDS patients.

Previous studies have found that open fractures, age, and medical comorbidities are significant predictors of short-term complications, such as wound healing, infection, persistent pain, and delayed union.3-6 Levy and colleagues11 examined the incidence of orthopedic trauma in positive UDS patients. These patients had orthopedic injuries that were more severe and required longer hospitalization. However, the study did not address patients with ankle fractures or the incidence of major complications. Diabetes and peripheral vascular disease are significant risk factors for many surgical procedures in orthopedic surgery.3,7-9,12,13 Tight glycemic control and optimization of medical comorbidities decrease postoperative complications.12,13 SooHoo and colleagues6 found that history of diabetes and history of peripheral vascular disease were significant predictors of short-term complications of mortality, infection, reoperation, and amputation. The rate of infection in the complicated diabetes group was statistically higher as well. The effect of illicit drug use was not analyzed in that study. We think the findings of the present study highlight the importance of screening for high-risk populations (eg, patients with diabetes, patients with peripheral vascular disease, drug abusers) before orthopedic surgery, especially during definitive treatment of ankle fracture.

Recently, Nåsell and colleagues10 found that a well-implemented smoking cessation program was associated with a statistically significant reduction in complications 6 and 12 weeks after surgery. The target treatment groups were patients who underwent major lower extremity and upper extremity orthopedic surgery. The most common surgery performed in the study was ORIF of ankle fractures. The authors concluded that a smoking cessation intervention program during the first 6 weeks after acute fracture surgery decreases the risk for postoperative complications. However, no recommendations were made for treating patients with other addictions, such as alcohol and illicit drug addictions.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to critically examine postoperative complications in ankle fracture patients with a history of illicit drug abuse as determined by preoperative positive UDS. These data suggest the importance of critically evaluating this patient population. The rates of deep infection, nonunion, and pooled major complications were all notable. Furthermore, compared with negative UDS patients, positive UDS patients were more than 7 times likely to develop a nonunion and more than 4 times likely to develop a deep infection. The reasons are likely multifactorial but may involve factors such as injury severity, poor nutrition, suboptimal living conditions, difficulty complying with weight-bearing restrictions, and, possibly, poor compliance with wound-care recommendations. Determining the influence of each factor was beyond the scope of this study. However, further investigation is warranted.

The difference in incidence of smoking between the 2 groups was statistically significant. As smoking has been well documented as contributing to poor wound and bone healing,14-16 it is likely to have been a contributory factor. However, nicotine levels are not routinely part of UDS, and people who quit smoking typically take 7 to 10 days to demonstrate a measurable drop in cotinine levels. On the other hand, screening for drugs takes only a few minutes and can provide useful information during the preoperative period. It was suggested that positive UDS patients were significantly likely to be tobacco users as well.

The 2 groups were not significantly different with respect to mean follow-up time or loss to follow-up. Although mean follow-up was longer in negative UDS patients, the standard deviation was large in both groups. Given the positive UDS patients’ higher incidence of deep infection and nonunion, both of which typically prolong the course of treatment, the results were likely deceptive. Patients with a history of illicit drug use have confounding variables (eg, psychiatric disorders, financial strife) that make treatment compliance and follow-up difficult.17

Some of the weaknesses of this study are inherent to its retrospective design and limited sample size. Furthermore, patient satisfaction scores and ankle-specific outcome measures, such as AOFAS (American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society) scores, were not considered. Prospective collection of data that include patient satisfaction scores and ankle-specific outcome measures would be optimal. Our current recommendation is to obtain preoperative UDS and illicit drug use history for all trauma patients. In addition, operating surgeons should exercise caution when caring for patients who test positive for illicit drugs.

Conclusion

We evaluated the incidence of complications experienced by positive UDS patients undergoing surgical treatment of ankle fractures. It is well documented that illicit drug users who receive general anesthesia have complications. However, little is known about the untoward effects of illicit drugs on postoperative complications. Furthermore, the efficacy of drug cessation programs in minimizing these complications has not been fully explored.

In conclusion, similar to patients with diabetes, patients with a history of recent illicit drug use, as evidenced by preoperative positive UDS, are at increased risk for complications during treatment for ankle fracture. These data suggest that practicing orthopedists should be more vigilant when caring for ankle fracture patients with preoperative positive UDS.

1. Michelson JD. Fractures about the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(1):142-152.

2. Culver JL, Walker JR. Anesthetic implications of illicit drug use. J Perianesth Nurs. 1999;14(2):82-90.

3. Bibbo C, Lin SS, Beam HA, Behrens FF. Complications of ankle fractures in diabetic patients. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;32(1):113-133.

4. Leininger RE, Knox CL, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of 1.6 million pediatric soccer-related injuries presenting to US emergency departments from 1990 to 2003. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2);288-293.

5. Clark RF, Harchelroad F. Toxicology screening of the trauma patient: a changing profile. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(2):151-153.

6. SooHoo NF, Krenek L, Eagan MJ, Gurbani B, Ko CY, Zingmond DS. Complication rates following open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(5):1042-1049.

7. Wukich DK, Kline AJ. The management of ankle fractures in patients with diabetes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(7):1570-1578.

8. Egol KA, Tejwani NC, Walsh MG, Capla EL, Koval KJ. Predictors of short-term functional outcome following ankle fracture surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(5):974-979.

9. Jones KB, Maiers-Yelden KA, Marsh JL, Zimmerman MB, Estin M, Saltzman CL. Ankle fractures in patients with diabetes mellitus J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(4):489-495.

10. Nåsell H, Adami J, Samnegård E, Tønnesen H, Ponzer S. Effect of smoking cessation intervention on results of acute fracture surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(6):1335-1342.

11. Levy RS, Hebert CK, Munn BG, Barrack RL. Drug and alcohol use in orthopedic trauma patients: a prospective study. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10(1):21-27.

12. Flynn JM, Rodriguez-del Rio F, Pizá PA. Closed ankle fractures in the diabetic patient. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21(4):311-319.

13. Dronge AS, Perkal MF, Kancir S, Concato J, Aslan M, Rosenthal RA. Long-term glycemic control and postoperative infectious complications. Arch Surg. 2006;141(4):375-380.

14. Sorensen LT, Karlsmark T, Gottrup F. Abstinence from smoking reduces incisional wound infection: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2003;238(1):1-5.

15. Møller AM, Pedersen T, Villebro N, Munksgaard A. Effect of smoking on early complications after elective orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(2):178-181.

16. Castillo RC, Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Patterson BM; LEAP Study Group. Impact of smoking on fracture healing and risk of complications in limb-threatening open tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(3):151-157.

17. Torrens M, Gilchrist G, Domingo-Salvany A; PsyCoBarcelona Group. Psychiatric comorbidity in illicit drug users: substance-induced versus independent disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;113(2-3):147-156.

Open treatment of ankle fractures is one of the most common procedures performed by orthopedic surgeons.1 Among the younger patient population, ankle fractures represent a significant proportion of orthopedic injuries.2 The reported incidence of illicit drug and alcohol use in the urban trauma population ranges from 36% to 86%,2 and medical and anesthetic complications associated with illicit drug use have been well documented in surgical patients.2 However, patients with a recent history of drug abuse may be subject to a separate but related set of complications of open treatment of ankle fractures.

The perioperative complications associated with open treatment of ankle fractures in patients with diabetes mellitus have been well described.3-6 Similarly, previous studies have suggested that peripheral vascular disease, complicated diabetes, and smoking are risk factors for poor outcomes in patients who require open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in lower extremity trauma.7-9 However, there are few data on the complications specifically associated with illicit drug use and orthopedic surgery. Properly identifying these high-risk groups and being cognizant of commonly associated complications are likely important in ensuring proper perioperative care and may alter follow-up protocols in these patients.

We conducted a study to identify the complications associated with open treatment of ankle fractures in patients who tested positive for illicit drugs on urine drug screen (UDS). We hypothesized that patients who had a history of positive UDS and underwent ORIF of an ankle fracture would have a higher incidence of major and minor complications.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of 142 patients who underwent open treatment of an ankle fracture between 2006 and 2010. Data sources included patient demographic information, radiographs, preoperative UDS, attending surgeons’ clinical office notes, and clinical laboratory data. Our institution’s standard protocol for ankle fractures was followed for all patients in the study. All patients were evaluated by an orthopedic physician, in either the emergency department or the office, during application of a well-padded Jones splint before surgery. Oral narcotic pain medication was routinely prescribed. All patients were seen, within 10 days of injury, for surgery planning. A board-certified orthopedic surgeon surgically stabilized the ankle fractures. The postoperative treatment regimen, per protocol, included non-weight-bearing in a padded Jones splint dressing; oral narcotic pain medication; physical therapy; and routine scheduled follow-up. In open fracture cases, patients were taken urgently to the operating room for irrigation and débridement with stabilization. Which treatment would be initially used—external fixation or ORIF—was determined on a case-by-case basis.

The sample consisted of adults (age, >18 years) who had undergone definitive ORIF of a lateral malleolar, bimalleolar, or trimalleolar ankle fracture during the study period. Polytrauma patients, patients with external fixation as definitive treatment, and patients with nonoperative treatment were excluded. Before surgical management, all patients were tested for recent illicit drug use by UDS (standard protocol at our institution). UDS, measured for cocaine, marijuana, PCP (phencyclidine), opiates, and barbiturates, was obtained in the office setting or emergency department or on day of surgery. The patients were divided into 2 groups, positive and negative UDS. Patients with documented receipt of narcotic pain medication before UDS were excluded.

The outcomes identified as dependent variables included nonunion, malunion, superficial or deep infection, amputation, delay in treatment, days to healing, repeat surgery, long-term bracing, and loss to follow-up. A nonunion was defined as lasting longer than 9 months and not showing radiographic signs of progression toward healing for 3 consecutive months. These complications were identified with use of attending surgeon clinical progress notes, laboratory values, radiographic parameters, and inpatient readmissions/surgeries associated with these outcomes. Nonunion, malunion, superficial or deep infection, and amputation were then grouped as major complications and analyzed as pooled major complications.

The Fisher exact test was used to analyze categorical variables with respect to UDS. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to determine statistical significance for continuous variables. Univariate logistic regression examined both continuous and categorical variables to evaluate predictors for a selected outcome. Statistical significance was set a priori at P ≤ .05, with significant factors indicating an increase (or decrease) in the outcome variable being tested.

Results

We retrospectively reviewed the cases of 142 patients. Table 1 lists the number of cases by fracture type. Bimalleolar fractures were most common, accounting for 99 (69.8%) of the 142 cases. Isolated lateral malleolar fractures accounted for 16 cases (11.2%), and trimalleolar fractures accounted for 27 cases (19%).

Twenty-five (18%) of the 142 patients tested positive for illicit drugs. Mean age was 45.2 years for positive UDS patients and 41.5 years for negative UDS patients. Open fracture cases represented 4.3% of negative UDS patients and 16% of positive UDS patients. Fifty-two percent of positive UDS patients and 32% of negative UDS patients were also tobacco users. These data were statistically significant (P = .003) There were no significant differences in age, sex, incidence of diabetes, incidence of open fracture, or time to surgery between the groups (Table 2).

Incidence of nonunion was higher in positive UDS patients (n = 5; P = .01), as was incidence of deep infection (n = 4; P = .05) (Table 3).

Mean time to radiographic healing was 50.7 days in negative UDS patients and 82.8 days in positive UDS patients (P > .99). Incidence of nonunion was 3.5% in negative UDS patients and 20% in positive UDS patients (P = .01). There were no malunions in negative UDS patients and 2 malunions in positive UDS patients. Incidence of deep infections was 2.5% in negative UDS patients and 16% in positive UDS patients (P = .04). No significant differences were found in incidence of malunions, superficial infections, amputations, need for repeat surgery, continued bracing, or loss to follow-up.

Major complications were defined as superficial or deep infections, amputations, malunions, and nonunions. The rate of major complication was significantly (P = .03) higher in positive UDS patients (24.24%) than in negative UDS patients (7.69%) (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of patients treated with ORIF for varying types of ankle fractures. Important major and minor complications were analyzed. The overall incidence of major complications in negative UDS patients was only 7.69%, consistent with previously reported results in patients with ankle fractures.6,10 However, a statistically significant (P = .03) increased incidence of major complications—an alarmingly high rate of almost 1 in 4—was found in positive UDS patients. Our results also demonstrated a significantly higher rate of nonunion and deep infection in positive UDS patients. Calculated odds ratios were 7.37 and 4.27 for nonunion and deep infection, respectively—arguably 2 of the most devastating postoperative complications in positive UDS patients.

Previous studies have found that open fractures, age, and medical comorbidities are significant predictors of short-term complications, such as wound healing, infection, persistent pain, and delayed union.3-6 Levy and colleagues11 examined the incidence of orthopedic trauma in positive UDS patients. These patients had orthopedic injuries that were more severe and required longer hospitalization. However, the study did not address patients with ankle fractures or the incidence of major complications. Diabetes and peripheral vascular disease are significant risk factors for many surgical procedures in orthopedic surgery.3,7-9,12,13 Tight glycemic control and optimization of medical comorbidities decrease postoperative complications.12,13 SooHoo and colleagues6 found that history of diabetes and history of peripheral vascular disease were significant predictors of short-term complications of mortality, infection, reoperation, and amputation. The rate of infection in the complicated diabetes group was statistically higher as well. The effect of illicit drug use was not analyzed in that study. We think the findings of the present study highlight the importance of screening for high-risk populations (eg, patients with diabetes, patients with peripheral vascular disease, drug abusers) before orthopedic surgery, especially during definitive treatment of ankle fracture.

Recently, Nåsell and colleagues10 found that a well-implemented smoking cessation program was associated with a statistically significant reduction in complications 6 and 12 weeks after surgery. The target treatment groups were patients who underwent major lower extremity and upper extremity orthopedic surgery. The most common surgery performed in the study was ORIF of ankle fractures. The authors concluded that a smoking cessation intervention program during the first 6 weeks after acute fracture surgery decreases the risk for postoperative complications. However, no recommendations were made for treating patients with other addictions, such as alcohol and illicit drug addictions.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to critically examine postoperative complications in ankle fracture patients with a history of illicit drug abuse as determined by preoperative positive UDS. These data suggest the importance of critically evaluating this patient population. The rates of deep infection, nonunion, and pooled major complications were all notable. Furthermore, compared with negative UDS patients, positive UDS patients were more than 7 times likely to develop a nonunion and more than 4 times likely to develop a deep infection. The reasons are likely multifactorial but may involve factors such as injury severity, poor nutrition, suboptimal living conditions, difficulty complying with weight-bearing restrictions, and, possibly, poor compliance with wound-care recommendations. Determining the influence of each factor was beyond the scope of this study. However, further investigation is warranted.

The difference in incidence of smoking between the 2 groups was statistically significant. As smoking has been well documented as contributing to poor wound and bone healing,14-16 it is likely to have been a contributory factor. However, nicotine levels are not routinely part of UDS, and people who quit smoking typically take 7 to 10 days to demonstrate a measurable drop in cotinine levels. On the other hand, screening for drugs takes only a few minutes and can provide useful information during the preoperative period. It was suggested that positive UDS patients were significantly likely to be tobacco users as well.

The 2 groups were not significantly different with respect to mean follow-up time or loss to follow-up. Although mean follow-up was longer in negative UDS patients, the standard deviation was large in both groups. Given the positive UDS patients’ higher incidence of deep infection and nonunion, both of which typically prolong the course of treatment, the results were likely deceptive. Patients with a history of illicit drug use have confounding variables (eg, psychiatric disorders, financial strife) that make treatment compliance and follow-up difficult.17

Some of the weaknesses of this study are inherent to its retrospective design and limited sample size. Furthermore, patient satisfaction scores and ankle-specific outcome measures, such as AOFAS (American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society) scores, were not considered. Prospective collection of data that include patient satisfaction scores and ankle-specific outcome measures would be optimal. Our current recommendation is to obtain preoperative UDS and illicit drug use history for all trauma patients. In addition, operating surgeons should exercise caution when caring for patients who test positive for illicit drugs.

Conclusion

We evaluated the incidence of complications experienced by positive UDS patients undergoing surgical treatment of ankle fractures. It is well documented that illicit drug users who receive general anesthesia have complications. However, little is known about the untoward effects of illicit drugs on postoperative complications. Furthermore, the efficacy of drug cessation programs in minimizing these complications has not been fully explored.

In conclusion, similar to patients with diabetes, patients with a history of recent illicit drug use, as evidenced by preoperative positive UDS, are at increased risk for complications during treatment for ankle fracture. These data suggest that practicing orthopedists should be more vigilant when caring for ankle fracture patients with preoperative positive UDS.

Open treatment of ankle fractures is one of the most common procedures performed by orthopedic surgeons.1 Among the younger patient population, ankle fractures represent a significant proportion of orthopedic injuries.2 The reported incidence of illicit drug and alcohol use in the urban trauma population ranges from 36% to 86%,2 and medical and anesthetic complications associated with illicit drug use have been well documented in surgical patients.2 However, patients with a recent history of drug abuse may be subject to a separate but related set of complications of open treatment of ankle fractures.

The perioperative complications associated with open treatment of ankle fractures in patients with diabetes mellitus have been well described.3-6 Similarly, previous studies have suggested that peripheral vascular disease, complicated diabetes, and smoking are risk factors for poor outcomes in patients who require open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in lower extremity trauma.7-9 However, there are few data on the complications specifically associated with illicit drug use and orthopedic surgery. Properly identifying these high-risk groups and being cognizant of commonly associated complications are likely important in ensuring proper perioperative care and may alter follow-up protocols in these patients.

We conducted a study to identify the complications associated with open treatment of ankle fractures in patients who tested positive for illicit drugs on urine drug screen (UDS). We hypothesized that patients who had a history of positive UDS and underwent ORIF of an ankle fracture would have a higher incidence of major and minor complications.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of 142 patients who underwent open treatment of an ankle fracture between 2006 and 2010. Data sources included patient demographic information, radiographs, preoperative UDS, attending surgeons’ clinical office notes, and clinical laboratory data. Our institution’s standard protocol for ankle fractures was followed for all patients in the study. All patients were evaluated by an orthopedic physician, in either the emergency department or the office, during application of a well-padded Jones splint before surgery. Oral narcotic pain medication was routinely prescribed. All patients were seen, within 10 days of injury, for surgery planning. A board-certified orthopedic surgeon surgically stabilized the ankle fractures. The postoperative treatment regimen, per protocol, included non-weight-bearing in a padded Jones splint dressing; oral narcotic pain medication; physical therapy; and routine scheduled follow-up. In open fracture cases, patients were taken urgently to the operating room for irrigation and débridement with stabilization. Which treatment would be initially used—external fixation or ORIF—was determined on a case-by-case basis.

The sample consisted of adults (age, >18 years) who had undergone definitive ORIF of a lateral malleolar, bimalleolar, or trimalleolar ankle fracture during the study period. Polytrauma patients, patients with external fixation as definitive treatment, and patients with nonoperative treatment were excluded. Before surgical management, all patients were tested for recent illicit drug use by UDS (standard protocol at our institution). UDS, measured for cocaine, marijuana, PCP (phencyclidine), opiates, and barbiturates, was obtained in the office setting or emergency department or on day of surgery. The patients were divided into 2 groups, positive and negative UDS. Patients with documented receipt of narcotic pain medication before UDS were excluded.

The outcomes identified as dependent variables included nonunion, malunion, superficial or deep infection, amputation, delay in treatment, days to healing, repeat surgery, long-term bracing, and loss to follow-up. A nonunion was defined as lasting longer than 9 months and not showing radiographic signs of progression toward healing for 3 consecutive months. These complications were identified with use of attending surgeon clinical progress notes, laboratory values, radiographic parameters, and inpatient readmissions/surgeries associated with these outcomes. Nonunion, malunion, superficial or deep infection, and amputation were then grouped as major complications and analyzed as pooled major complications.

The Fisher exact test was used to analyze categorical variables with respect to UDS. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to determine statistical significance for continuous variables. Univariate logistic regression examined both continuous and categorical variables to evaluate predictors for a selected outcome. Statistical significance was set a priori at P ≤ .05, with significant factors indicating an increase (or decrease) in the outcome variable being tested.

Results

We retrospectively reviewed the cases of 142 patients. Table 1 lists the number of cases by fracture type. Bimalleolar fractures were most common, accounting for 99 (69.8%) of the 142 cases. Isolated lateral malleolar fractures accounted for 16 cases (11.2%), and trimalleolar fractures accounted for 27 cases (19%).

Twenty-five (18%) of the 142 patients tested positive for illicit drugs. Mean age was 45.2 years for positive UDS patients and 41.5 years for negative UDS patients. Open fracture cases represented 4.3% of negative UDS patients and 16% of positive UDS patients. Fifty-two percent of positive UDS patients and 32% of negative UDS patients were also tobacco users. These data were statistically significant (P = .003) There were no significant differences in age, sex, incidence of diabetes, incidence of open fracture, or time to surgery between the groups (Table 2).

Incidence of nonunion was higher in positive UDS patients (n = 5; P = .01), as was incidence of deep infection (n = 4; P = .05) (Table 3).

Mean time to radiographic healing was 50.7 days in negative UDS patients and 82.8 days in positive UDS patients (P > .99). Incidence of nonunion was 3.5% in negative UDS patients and 20% in positive UDS patients (P = .01). There were no malunions in negative UDS patients and 2 malunions in positive UDS patients. Incidence of deep infections was 2.5% in negative UDS patients and 16% in positive UDS patients (P = .04). No significant differences were found in incidence of malunions, superficial infections, amputations, need for repeat surgery, continued bracing, or loss to follow-up.

Major complications were defined as superficial or deep infections, amputations, malunions, and nonunions. The rate of major complication was significantly (P = .03) higher in positive UDS patients (24.24%) than in negative UDS patients (7.69%) (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of patients treated with ORIF for varying types of ankle fractures. Important major and minor complications were analyzed. The overall incidence of major complications in negative UDS patients was only 7.69%, consistent with previously reported results in patients with ankle fractures.6,10 However, a statistically significant (P = .03) increased incidence of major complications—an alarmingly high rate of almost 1 in 4—was found in positive UDS patients. Our results also demonstrated a significantly higher rate of nonunion and deep infection in positive UDS patients. Calculated odds ratios were 7.37 and 4.27 for nonunion and deep infection, respectively—arguably 2 of the most devastating postoperative complications in positive UDS patients.

Previous studies have found that open fractures, age, and medical comorbidities are significant predictors of short-term complications, such as wound healing, infection, persistent pain, and delayed union.3-6 Levy and colleagues11 examined the incidence of orthopedic trauma in positive UDS patients. These patients had orthopedic injuries that were more severe and required longer hospitalization. However, the study did not address patients with ankle fractures or the incidence of major complications. Diabetes and peripheral vascular disease are significant risk factors for many surgical procedures in orthopedic surgery.3,7-9,12,13 Tight glycemic control and optimization of medical comorbidities decrease postoperative complications.12,13 SooHoo and colleagues6 found that history of diabetes and history of peripheral vascular disease were significant predictors of short-term complications of mortality, infection, reoperation, and amputation. The rate of infection in the complicated diabetes group was statistically higher as well. The effect of illicit drug use was not analyzed in that study. We think the findings of the present study highlight the importance of screening for high-risk populations (eg, patients with diabetes, patients with peripheral vascular disease, drug abusers) before orthopedic surgery, especially during definitive treatment of ankle fracture.

Recently, Nåsell and colleagues10 found that a well-implemented smoking cessation program was associated with a statistically significant reduction in complications 6 and 12 weeks after surgery. The target treatment groups were patients who underwent major lower extremity and upper extremity orthopedic surgery. The most common surgery performed in the study was ORIF of ankle fractures. The authors concluded that a smoking cessation intervention program during the first 6 weeks after acute fracture surgery decreases the risk for postoperative complications. However, no recommendations were made for treating patients with other addictions, such as alcohol and illicit drug addictions.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to critically examine postoperative complications in ankle fracture patients with a history of illicit drug abuse as determined by preoperative positive UDS. These data suggest the importance of critically evaluating this patient population. The rates of deep infection, nonunion, and pooled major complications were all notable. Furthermore, compared with negative UDS patients, positive UDS patients were more than 7 times likely to develop a nonunion and more than 4 times likely to develop a deep infection. The reasons are likely multifactorial but may involve factors such as injury severity, poor nutrition, suboptimal living conditions, difficulty complying with weight-bearing restrictions, and, possibly, poor compliance with wound-care recommendations. Determining the influence of each factor was beyond the scope of this study. However, further investigation is warranted.

The difference in incidence of smoking between the 2 groups was statistically significant. As smoking has been well documented as contributing to poor wound and bone healing,14-16 it is likely to have been a contributory factor. However, nicotine levels are not routinely part of UDS, and people who quit smoking typically take 7 to 10 days to demonstrate a measurable drop in cotinine levels. On the other hand, screening for drugs takes only a few minutes and can provide useful information during the preoperative period. It was suggested that positive UDS patients were significantly likely to be tobacco users as well.

The 2 groups were not significantly different with respect to mean follow-up time or loss to follow-up. Although mean follow-up was longer in negative UDS patients, the standard deviation was large in both groups. Given the positive UDS patients’ higher incidence of deep infection and nonunion, both of which typically prolong the course of treatment, the results were likely deceptive. Patients with a history of illicit drug use have confounding variables (eg, psychiatric disorders, financial strife) that make treatment compliance and follow-up difficult.17

Some of the weaknesses of this study are inherent to its retrospective design and limited sample size. Furthermore, patient satisfaction scores and ankle-specific outcome measures, such as AOFAS (American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society) scores, were not considered. Prospective collection of data that include patient satisfaction scores and ankle-specific outcome measures would be optimal. Our current recommendation is to obtain preoperative UDS and illicit drug use history for all trauma patients. In addition, operating surgeons should exercise caution when caring for patients who test positive for illicit drugs.

Conclusion

We evaluated the incidence of complications experienced by positive UDS patients undergoing surgical treatment of ankle fractures. It is well documented that illicit drug users who receive general anesthesia have complications. However, little is known about the untoward effects of illicit drugs on postoperative complications. Furthermore, the efficacy of drug cessation programs in minimizing these complications has not been fully explored.

In conclusion, similar to patients with diabetes, patients with a history of recent illicit drug use, as evidenced by preoperative positive UDS, are at increased risk for complications during treatment for ankle fracture. These data suggest that practicing orthopedists should be more vigilant when caring for ankle fracture patients with preoperative positive UDS.

1. Michelson JD. Fractures about the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(1):142-152.

2. Culver JL, Walker JR. Anesthetic implications of illicit drug use. J Perianesth Nurs. 1999;14(2):82-90.

3. Bibbo C, Lin SS, Beam HA, Behrens FF. Complications of ankle fractures in diabetic patients. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;32(1):113-133.