User login

FDA approves adhesive treatment for superficial varicose veins

The VenaSeal closure system, which uses an adhesive directly injected into the vein, has been approved as a permanent treatment for symptomatic, superficial varicose veins, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Feb. 20.

“This new system is the first to permanently treat varicose veins by sealing them with an adhesive,” Dr. William Maisel, acting director of the Office of Device Evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the FDA’s statement. Because the system “does not incorporate heat application or cutting, the in-office procedure can allow patients to quickly return to their normal activities, with less bruising,” he added.

The VenaSeal system differs from other procedures used to treat varicose veins, which use drugs, lasers, radiofrequency, or incisions, the FDA statement points out. The complete sterile kit includes the adhesive (n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate), which solidifies when injected directly into the target vein via a catheter, under ultrasound guidance. The additional system components include the catheter, the adhesive, a guidewire, dispenser gun, dispenser tips, and syringes.

Approval was based on data from three clinical trials sponsored by the manufacturer. In the U.S. study that compared results in 108 patients treated with the VenaSeal system and 114 patients treated with radiofrequency ablation therapy, the device was shown “to be safe and effective for vein closure for the treatment of symptomatic superficial varicose veins of the legs,” according to the FDA. In the study, adverse events associated with the VenaSeal treatment included phlebitis and paresthesias in the treated areas, which are “generally associated with treatments of this condition,” the FDA statement noted.

The agency reviewed the VenaSeal System as a class III medical device, considered the highest risk type of medical devices that are subjected to the highest level of regulatory control, and which must be approved before marketing.

VenaSeal is manufactured by Covidien, which acquired Sapheon, the company that developed VenaSeal, in 2014. The system has also been approved in Canada, Europe, and Hong Kong, according to a Covidien statement issued last year.

The VenaSeal closure system, which uses an adhesive directly injected into the vein, has been approved as a permanent treatment for symptomatic, superficial varicose veins, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Feb. 20.

“This new system is the first to permanently treat varicose veins by sealing them with an adhesive,” Dr. William Maisel, acting director of the Office of Device Evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the FDA’s statement. Because the system “does not incorporate heat application or cutting, the in-office procedure can allow patients to quickly return to their normal activities, with less bruising,” he added.

The VenaSeal system differs from other procedures used to treat varicose veins, which use drugs, lasers, radiofrequency, or incisions, the FDA statement points out. The complete sterile kit includes the adhesive (n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate), which solidifies when injected directly into the target vein via a catheter, under ultrasound guidance. The additional system components include the catheter, the adhesive, a guidewire, dispenser gun, dispenser tips, and syringes.

Approval was based on data from three clinical trials sponsored by the manufacturer. In the U.S. study that compared results in 108 patients treated with the VenaSeal system and 114 patients treated with radiofrequency ablation therapy, the device was shown “to be safe and effective for vein closure for the treatment of symptomatic superficial varicose veins of the legs,” according to the FDA. In the study, adverse events associated with the VenaSeal treatment included phlebitis and paresthesias in the treated areas, which are “generally associated with treatments of this condition,” the FDA statement noted.

The agency reviewed the VenaSeal System as a class III medical device, considered the highest risk type of medical devices that are subjected to the highest level of regulatory control, and which must be approved before marketing.

VenaSeal is manufactured by Covidien, which acquired Sapheon, the company that developed VenaSeal, in 2014. The system has also been approved in Canada, Europe, and Hong Kong, according to a Covidien statement issued last year.

The VenaSeal closure system, which uses an adhesive directly injected into the vein, has been approved as a permanent treatment for symptomatic, superficial varicose veins, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Feb. 20.

“This new system is the first to permanently treat varicose veins by sealing them with an adhesive,” Dr. William Maisel, acting director of the Office of Device Evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the FDA’s statement. Because the system “does not incorporate heat application or cutting, the in-office procedure can allow patients to quickly return to their normal activities, with less bruising,” he added.

The VenaSeal system differs from other procedures used to treat varicose veins, which use drugs, lasers, radiofrequency, or incisions, the FDA statement points out. The complete sterile kit includes the adhesive (n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate), which solidifies when injected directly into the target vein via a catheter, under ultrasound guidance. The additional system components include the catheter, the adhesive, a guidewire, dispenser gun, dispenser tips, and syringes.

Approval was based on data from three clinical trials sponsored by the manufacturer. In the U.S. study that compared results in 108 patients treated with the VenaSeal system and 114 patients treated with radiofrequency ablation therapy, the device was shown “to be safe and effective for vein closure for the treatment of symptomatic superficial varicose veins of the legs,” according to the FDA. In the study, adverse events associated with the VenaSeal treatment included phlebitis and paresthesias in the treated areas, which are “generally associated with treatments of this condition,” the FDA statement noted.

The agency reviewed the VenaSeal System as a class III medical device, considered the highest risk type of medical devices that are subjected to the highest level of regulatory control, and which must be approved before marketing.

VenaSeal is manufactured by Covidien, which acquired Sapheon, the company that developed VenaSeal, in 2014. The system has also been approved in Canada, Europe, and Hong Kong, according to a Covidien statement issued last year.

Abnormal calcium level in a psychiatric presentation? Rule out parathyroid disease

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

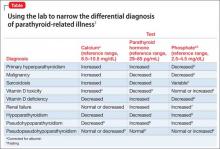

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

Can Vitamin D Supplements Help With Hypertension?

Q) One of my patients came in and said he had read that vitamin D supplementation will help with hypertension. Now he wants to quit his blood pressure meds and use vitamin D instead. Do you have any background on this?

Vitamin D is critical for utilization of calcium, a vital nutrient for multiple metabolic and cellular processes; deficiency is associated with worsening of autoimmune disorders, osteoporosis, and certain cardiovascular conditions, among others.7 An association between vitamin D level and blood pressure has been recognized for some time, but the pathophysiology is not well understood.

A literature review of studies from 1988 to 2013 found contradictory results regarding vitamin D deficiency and concurrent elevated blood pressure (systolic and/or diastolic), as well as the impact on blood pressure with restoration of vitamin D levels. The findings were limited by several factors, including differences in study design, variables evaluated, and type of vitamin D compound used. The results suggested a link between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, fibroblast growth factor 23/klotho axis, and vitamin D level.8

A study of 158 subjects (98 with newly diagnosed essential hypertension, 60 with normal blood pressure) found significantly lower 25(OH)D3 serum levels in hypertensive patients. Furthermore, the 25(OH)D3 level was significantly correlated with both systolic (r = –0.33) and diastolic blood pressure (r = –0.26). Using multiple regression analysis, after adjustment for age, smoking status, and BMI, the impact of 25(OH)D3 level accounted for 10% of the variation in systolic blood pressure.9

In a mendelian randomization study of 108,173 subjects from 35 studies, an inverse association between vitamin D level and systolic blood pressure (P = .0003) was found. A reduced risk for essential hypertension with increased vitamin D level (P = .0003) was also noted. However, no association was found between increasing vitamin D level and a reduction in diastolic blood pressure

(P = .37).10

With the ever-increasing access to health information from sources such as “Doctor Google,” it can be difficult for a non–health care professional to separate hype from evidence-based recommendations. While current evidence suggests optimal vitamin D levels may be beneficial for improving blood pressure control and may be a useful adjunctive therapy, there is no evidence to support discontinuing antihypertensive therapy and replacing it with vitamin D therapy.

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC

Renal Consultants, South Charleston, West Virginia

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

Q) One of my patients came in and said he had read that vitamin D supplementation will help with hypertension. Now he wants to quit his blood pressure meds and use vitamin D instead. Do you have any background on this?

Vitamin D is critical for utilization of calcium, a vital nutrient for multiple metabolic and cellular processes; deficiency is associated with worsening of autoimmune disorders, osteoporosis, and certain cardiovascular conditions, among others.7 An association between vitamin D level and blood pressure has been recognized for some time, but the pathophysiology is not well understood.

A literature review of studies from 1988 to 2013 found contradictory results regarding vitamin D deficiency and concurrent elevated blood pressure (systolic and/or diastolic), as well as the impact on blood pressure with restoration of vitamin D levels. The findings were limited by several factors, including differences in study design, variables evaluated, and type of vitamin D compound used. The results suggested a link between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, fibroblast growth factor 23/klotho axis, and vitamin D level.8

A study of 158 subjects (98 with newly diagnosed essential hypertension, 60 with normal blood pressure) found significantly lower 25(OH)D3 serum levels in hypertensive patients. Furthermore, the 25(OH)D3 level was significantly correlated with both systolic (r = –0.33) and diastolic blood pressure (r = –0.26). Using multiple regression analysis, after adjustment for age, smoking status, and BMI, the impact of 25(OH)D3 level accounted for 10% of the variation in systolic blood pressure.9

In a mendelian randomization study of 108,173 subjects from 35 studies, an inverse association between vitamin D level and systolic blood pressure (P = .0003) was found. A reduced risk for essential hypertension with increased vitamin D level (P = .0003) was also noted. However, no association was found between increasing vitamin D level and a reduction in diastolic blood pressure

(P = .37).10

With the ever-increasing access to health information from sources such as “Doctor Google,” it can be difficult for a non–health care professional to separate hype from evidence-based recommendations. While current evidence suggests optimal vitamin D levels may be beneficial for improving blood pressure control and may be a useful adjunctive therapy, there is no evidence to support discontinuing antihypertensive therapy and replacing it with vitamin D therapy.

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC

Renal Consultants, South Charleston, West Virginia

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

Q) One of my patients came in and said he had read that vitamin D supplementation will help with hypertension. Now he wants to quit his blood pressure meds and use vitamin D instead. Do you have any background on this?

Vitamin D is critical for utilization of calcium, a vital nutrient for multiple metabolic and cellular processes; deficiency is associated with worsening of autoimmune disorders, osteoporosis, and certain cardiovascular conditions, among others.7 An association between vitamin D level and blood pressure has been recognized for some time, but the pathophysiology is not well understood.

A literature review of studies from 1988 to 2013 found contradictory results regarding vitamin D deficiency and concurrent elevated blood pressure (systolic and/or diastolic), as well as the impact on blood pressure with restoration of vitamin D levels. The findings were limited by several factors, including differences in study design, variables evaluated, and type of vitamin D compound used. The results suggested a link between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, fibroblast growth factor 23/klotho axis, and vitamin D level.8

A study of 158 subjects (98 with newly diagnosed essential hypertension, 60 with normal blood pressure) found significantly lower 25(OH)D3 serum levels in hypertensive patients. Furthermore, the 25(OH)D3 level was significantly correlated with both systolic (r = –0.33) and diastolic blood pressure (r = –0.26). Using multiple regression analysis, after adjustment for age, smoking status, and BMI, the impact of 25(OH)D3 level accounted for 10% of the variation in systolic blood pressure.9

In a mendelian randomization study of 108,173 subjects from 35 studies, an inverse association between vitamin D level and systolic blood pressure (P = .0003) was found. A reduced risk for essential hypertension with increased vitamin D level (P = .0003) was also noted. However, no association was found between increasing vitamin D level and a reduction in diastolic blood pressure

(P = .37).10

With the ever-increasing access to health information from sources such as “Doctor Google,” it can be difficult for a non–health care professional to separate hype from evidence-based recommendations. While current evidence suggests optimal vitamin D levels may be beneficial for improving blood pressure control and may be a useful adjunctive therapy, there is no evidence to support discontinuing antihypertensive therapy and replacing it with vitamin D therapy.

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC

Renal Consultants, South Charleston, West Virginia

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

How to write a suicide risk assessment that’s clinically sound and legally defensible

Suicidologists and legal experts implore clinicians to document their suicide risk assessments (SRAs) thoroughly. It’s difficult, however, to find practical guidance on how to write a clinically sound, legally defensible SRA.

The crux of every SRA is written justification of suicide risk. That justification should reveal your thinking and present a well-reasoned basis for your decision.

Reasoned vs right

It’s more important to provide a justification of suicide risk that’s well-reasoned rather than one that’s right. Suicide is impossible to predict. Instead of prediction, legally we are asked to reasonably anticipate suicide based on clinical facts. In hindsight, especially in the context of a courtroom, decisions might look ill-considered. You need to craft a logical argument, be clear, and avoid jargon.

Convey thoroughness by covering each component of an SRA. Use the mnemonic device CAIPS to help the reader (and you) understand how a conclusion was reached based on the facts of the case.

Chronic and Acute factors. Address the chronic and acute factors that weigh heaviest in your mind. Chronic factors are conditions, past events, and demographics that generally do not change. Acute factors are recent events or conditions that potentially are modifiable. Pay attention to combinations of factors that dramatically elevate risk (eg, previous attempts in the context of acute depression). Avoid repeating every factor, especially when these are documented elsewhere, such as on a checklist.

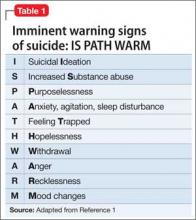

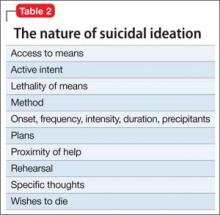

Imminent warning signs for suicide. Address warning signs (Table 1),1 the nature of current suicidal thoughts (Table 2), and other aspects of mental status (eg, future orientation) that influenced your decision. Use words like “moreover,” “however,” and “in addition” to draw the reader’s attention to the building blocks of your argument.

Protective factors. Discuss the protective factors last; they deserve the least weight because none has been shown to immunize people against suicide. Don’t solely rely on your judgment of what is protective (eg, children in the home). Instead, elicit the patient’s reasons for living and dying. Be concerned if he (she) reports more of the latter.

Summary statement. Make an explicit statement about risk, focusing on imminent risk (ie, the next few hours and days). Avoid a “plot twist,” which is a risk level inconsistent with the preceding evidence, because it suggests an error in judgment. The Box gives an example of a justification that follows the CAIPS method.

Additional tips

Consider these strategies:

• Bolster your argument by explicitly addressing hopelessness (the strongest psychological correlate of suicide); use quotes from the patient that support your decision; refer to consultation with family members and colleagues; and include pertinent negatives to show completeness2 (ie, “denied suicide plans”).

• Critically resolve discrepancies between what the patient says and behavior that suggests suicidal intent (eg, a patient who minimizes suicidal intent but shopped for a gun yesterday).

• Last, while reviewing your justification, imagine that your patient completed suicide after leaving your office and that you are in court for negligence. In our experience, this exercise reveals dangerous errors of judgment. A clear and reasoned justification will reduce the risk of litigation and help you make prudent treatment plans.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Association of Suicidology. Know the warning signs of suicide. http://www.suicidology.org/resources/ warning-signs. Accessed February 9, 2014.

2. Ballas C. How to write a suicide note: practical tips for documenting the evaluation of a suicidal patient. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/how-write-suicide-note-practical-tips-documenting-evaluation-suicidal-patient. Published May 1, 2007. Accessed July 29, 2013.

Suicidologists and legal experts implore clinicians to document their suicide risk assessments (SRAs) thoroughly. It’s difficult, however, to find practical guidance on how to write a clinically sound, legally defensible SRA.

The crux of every SRA is written justification of suicide risk. That justification should reveal your thinking and present a well-reasoned basis for your decision.

Reasoned vs right

It’s more important to provide a justification of suicide risk that’s well-reasoned rather than one that’s right. Suicide is impossible to predict. Instead of prediction, legally we are asked to reasonably anticipate suicide based on clinical facts. In hindsight, especially in the context of a courtroom, decisions might look ill-considered. You need to craft a logical argument, be clear, and avoid jargon.

Convey thoroughness by covering each component of an SRA. Use the mnemonic device CAIPS to help the reader (and you) understand how a conclusion was reached based on the facts of the case.

Chronic and Acute factors. Address the chronic and acute factors that weigh heaviest in your mind. Chronic factors are conditions, past events, and demographics that generally do not change. Acute factors are recent events or conditions that potentially are modifiable. Pay attention to combinations of factors that dramatically elevate risk (eg, previous attempts in the context of acute depression). Avoid repeating every factor, especially when these are documented elsewhere, such as on a checklist.

Imminent warning signs for suicide. Address warning signs (Table 1),1 the nature of current suicidal thoughts (Table 2), and other aspects of mental status (eg, future orientation) that influenced your decision. Use words like “moreover,” “however,” and “in addition” to draw the reader’s attention to the building blocks of your argument.

Protective factors. Discuss the protective factors last; they deserve the least weight because none has been shown to immunize people against suicide. Don’t solely rely on your judgment of what is protective (eg, children in the home). Instead, elicit the patient’s reasons for living and dying. Be concerned if he (she) reports more of the latter.

Summary statement. Make an explicit statement about risk, focusing on imminent risk (ie, the next few hours and days). Avoid a “plot twist,” which is a risk level inconsistent with the preceding evidence, because it suggests an error in judgment. The Box gives an example of a justification that follows the CAIPS method.

Additional tips

Consider these strategies:

• Bolster your argument by explicitly addressing hopelessness (the strongest psychological correlate of suicide); use quotes from the patient that support your decision; refer to consultation with family members and colleagues; and include pertinent negatives to show completeness2 (ie, “denied suicide plans”).

• Critically resolve discrepancies between what the patient says and behavior that suggests suicidal intent (eg, a patient who minimizes suicidal intent but shopped for a gun yesterday).

• Last, while reviewing your justification, imagine that your patient completed suicide after leaving your office and that you are in court for negligence. In our experience, this exercise reveals dangerous errors of judgment. A clear and reasoned justification will reduce the risk of litigation and help you make prudent treatment plans.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Suicidologists and legal experts implore clinicians to document their suicide risk assessments (SRAs) thoroughly. It’s difficult, however, to find practical guidance on how to write a clinically sound, legally defensible SRA.

The crux of every SRA is written justification of suicide risk. That justification should reveal your thinking and present a well-reasoned basis for your decision.

Reasoned vs right

It’s more important to provide a justification of suicide risk that’s well-reasoned rather than one that’s right. Suicide is impossible to predict. Instead of prediction, legally we are asked to reasonably anticipate suicide based on clinical facts. In hindsight, especially in the context of a courtroom, decisions might look ill-considered. You need to craft a logical argument, be clear, and avoid jargon.

Convey thoroughness by covering each component of an SRA. Use the mnemonic device CAIPS to help the reader (and you) understand how a conclusion was reached based on the facts of the case.

Chronic and Acute factors. Address the chronic and acute factors that weigh heaviest in your mind. Chronic factors are conditions, past events, and demographics that generally do not change. Acute factors are recent events or conditions that potentially are modifiable. Pay attention to combinations of factors that dramatically elevate risk (eg, previous attempts in the context of acute depression). Avoid repeating every factor, especially when these are documented elsewhere, such as on a checklist.

Imminent warning signs for suicide. Address warning signs (Table 1),1 the nature of current suicidal thoughts (Table 2), and other aspects of mental status (eg, future orientation) that influenced your decision. Use words like “moreover,” “however,” and “in addition” to draw the reader’s attention to the building blocks of your argument.

Protective factors. Discuss the protective factors last; they deserve the least weight because none has been shown to immunize people against suicide. Don’t solely rely on your judgment of what is protective (eg, children in the home). Instead, elicit the patient’s reasons for living and dying. Be concerned if he (she) reports more of the latter.

Summary statement. Make an explicit statement about risk, focusing on imminent risk (ie, the next few hours and days). Avoid a “plot twist,” which is a risk level inconsistent with the preceding evidence, because it suggests an error in judgment. The Box gives an example of a justification that follows the CAIPS method.

Additional tips

Consider these strategies:

• Bolster your argument by explicitly addressing hopelessness (the strongest psychological correlate of suicide); use quotes from the patient that support your decision; refer to consultation with family members and colleagues; and include pertinent negatives to show completeness2 (ie, “denied suicide plans”).

• Critically resolve discrepancies between what the patient says and behavior that suggests suicidal intent (eg, a patient who minimizes suicidal intent but shopped for a gun yesterday).

• Last, while reviewing your justification, imagine that your patient completed suicide after leaving your office and that you are in court for negligence. In our experience, this exercise reveals dangerous errors of judgment. A clear and reasoned justification will reduce the risk of litigation and help you make prudent treatment plans.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Association of Suicidology. Know the warning signs of suicide. http://www.suicidology.org/resources/ warning-signs. Accessed February 9, 2014.

2. Ballas C. How to write a suicide note: practical tips for documenting the evaluation of a suicidal patient. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/how-write-suicide-note-practical-tips-documenting-evaluation-suicidal-patient. Published May 1, 2007. Accessed July 29, 2013.

1. American Association of Suicidology. Know the warning signs of suicide. http://www.suicidology.org/resources/ warning-signs. Accessed February 9, 2014.

2. Ballas C. How to write a suicide note: practical tips for documenting the evaluation of a suicidal patient. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/how-write-suicide-note-practical-tips-documenting-evaluation-suicidal-patient. Published May 1, 2007. Accessed July 29, 2013.

When your diagnosis is questioned

When patients question your diagnosis, how do you react?

As physicians, we take great pride in our ability to diagnose and treat disease, and as hospitalists, our patients are sicker, so we need to make the right diagnosis and make it fast. A diagnostic delay of even a few days can sometimes cost a patient his life.

So when the patient or a family member disagrees with your diagnosis – especially when they have no remote understanding of the condition – it can be easy to dismiss their concerns. And then there are the times when you’ve missed something and they are right.

I will never forget a 60-year-old male patient I encountered early in my career as a hospitalist. He had presented with diffuse abdominal pain which later localized to both lower quadrants, diarrhea, and CT scan evidence of gastroenteritis. Multiple doctors who saw the patient before me all had the same diagnosis, a simple case of gastroenteritis. By day 2, he was afebrile, had a normal white blood cell count, was eating, and was ambulating down the hallway with his large family, seemingly in no distress.

He related that he still had abdominal pain, but felt comfortable with his diagnosis and was amenable to being discharged to follow-up with the gastroenterologist who had consulted on him during his stay in the hospital. His niece, on the other hand, was not happy with the diagnosis. The look on her face was intense, not disrespectful, as she related her conviction that her uncle had something more going on than a bout of gastroenteritis. She knew her uncle far better than I did, and his pain was concerning to her.

So I went back to the drawing board to make sure nothing had been missed, and there, hidden in plain sight, was a vital piece of information that we had all overlooked. The CT scan report that showed signs consistent with gastroenteritis made no mention whatsoever of his appendix.

Not satisfied with simply having another radiologist read the film, I insisted that a surgeon see the patient. To the surgeon’s great surprise, and mine, he found evidence of appendicitis. By 10 a.m. the next morning, the patient was in the OR having a now-perforated appendix removed. After numerous apologies to the family and patient, he was discharged home on postop day 2, doing well.

That very scary near miss taught me a valuable lesson: Sometimes the gut instinct of patients and their family members is just as accurate as the gut instinct of a physician, and we need to fully respect their input, whether or not we agree with them.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

When patients question your diagnosis, how do you react?

As physicians, we take great pride in our ability to diagnose and treat disease, and as hospitalists, our patients are sicker, so we need to make the right diagnosis and make it fast. A diagnostic delay of even a few days can sometimes cost a patient his life.

So when the patient or a family member disagrees with your diagnosis – especially when they have no remote understanding of the condition – it can be easy to dismiss their concerns. And then there are the times when you’ve missed something and they are right.

I will never forget a 60-year-old male patient I encountered early in my career as a hospitalist. He had presented with diffuse abdominal pain which later localized to both lower quadrants, diarrhea, and CT scan evidence of gastroenteritis. Multiple doctors who saw the patient before me all had the same diagnosis, a simple case of gastroenteritis. By day 2, he was afebrile, had a normal white blood cell count, was eating, and was ambulating down the hallway with his large family, seemingly in no distress.

He related that he still had abdominal pain, but felt comfortable with his diagnosis and was amenable to being discharged to follow-up with the gastroenterologist who had consulted on him during his stay in the hospital. His niece, on the other hand, was not happy with the diagnosis. The look on her face was intense, not disrespectful, as she related her conviction that her uncle had something more going on than a bout of gastroenteritis. She knew her uncle far better than I did, and his pain was concerning to her.

So I went back to the drawing board to make sure nothing had been missed, and there, hidden in plain sight, was a vital piece of information that we had all overlooked. The CT scan report that showed signs consistent with gastroenteritis made no mention whatsoever of his appendix.

Not satisfied with simply having another radiologist read the film, I insisted that a surgeon see the patient. To the surgeon’s great surprise, and mine, he found evidence of appendicitis. By 10 a.m. the next morning, the patient was in the OR having a now-perforated appendix removed. After numerous apologies to the family and patient, he was discharged home on postop day 2, doing well.

That very scary near miss taught me a valuable lesson: Sometimes the gut instinct of patients and their family members is just as accurate as the gut instinct of a physician, and we need to fully respect their input, whether or not we agree with them.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

When patients question your diagnosis, how do you react?

As physicians, we take great pride in our ability to diagnose and treat disease, and as hospitalists, our patients are sicker, so we need to make the right diagnosis and make it fast. A diagnostic delay of even a few days can sometimes cost a patient his life.

So when the patient or a family member disagrees with your diagnosis – especially when they have no remote understanding of the condition – it can be easy to dismiss their concerns. And then there are the times when you’ve missed something and they are right.

I will never forget a 60-year-old male patient I encountered early in my career as a hospitalist. He had presented with diffuse abdominal pain which later localized to both lower quadrants, diarrhea, and CT scan evidence of gastroenteritis. Multiple doctors who saw the patient before me all had the same diagnosis, a simple case of gastroenteritis. By day 2, he was afebrile, had a normal white blood cell count, was eating, and was ambulating down the hallway with his large family, seemingly in no distress.

He related that he still had abdominal pain, but felt comfortable with his diagnosis and was amenable to being discharged to follow-up with the gastroenterologist who had consulted on him during his stay in the hospital. His niece, on the other hand, was not happy with the diagnosis. The look on her face was intense, not disrespectful, as she related her conviction that her uncle had something more going on than a bout of gastroenteritis. She knew her uncle far better than I did, and his pain was concerning to her.

So I went back to the drawing board to make sure nothing had been missed, and there, hidden in plain sight, was a vital piece of information that we had all overlooked. The CT scan report that showed signs consistent with gastroenteritis made no mention whatsoever of his appendix.

Not satisfied with simply having another radiologist read the film, I insisted that a surgeon see the patient. To the surgeon’s great surprise, and mine, he found evidence of appendicitis. By 10 a.m. the next morning, the patient was in the OR having a now-perforated appendix removed. After numerous apologies to the family and patient, he was discharged home on postop day 2, doing well.

That very scary near miss taught me a valuable lesson: Sometimes the gut instinct of patients and their family members is just as accurate as the gut instinct of a physician, and we need to fully respect their input, whether or not we agree with them.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

Maternal age, cardioseptal defects are major risk factors for peripartum thrombosis

NASHVILLE, TENN. – The risk of a peripartum thrombotic event is rare, but significantly increased for women who have a cardioseptal defect. In a large national sample, the rate of thrombotic events was seven times higher among women with an atrial or ventral septal defect.

Advanced maternal age also was a significant independent predictor of this complication; among more than 7,000 women who developed a thrombotic complication, 81% were older than 45 years.

Dr. Ali Razmara of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, mined the National Inpatient Sample for data linking peripartum thrombotic events to patient demographics and medical comorbidities. His cohort comprised 4.3 million normal vaginal and cesarean deliveries from 2000 to 2010. Events of interest included transient ischemic attack, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, acute MI, and venous thromboembolism.

There were 7,242 peripartum thrombotic events (0.17%).The majority occurred in women who were older than 45 years (81%); white (58%); and admitted through the emergency department (67%). Women with thrombotic events were more likely to have hypertension (52% vs. 2%), dyslipidemia (26% vs. 0.52%), diabetes (20% vs. 2%), atrial fibrillation (10% vs. 0.23%), and heart failure (10% vs. 0.26%), he said at the International Stroke Conference.

A multivariate regression model controlled for patient demographics and comorbidities, including, among others, preeclampsia, hypercoagulable states, chorioamnionitis, renal and liver disease, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders including atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and atrial/ventral septal defects.

In a multivariate regression analysis, maternal age shook out as the most powerful independent risk factor; the rate of thrombosis was 91 times greater among women older than age 45 years.

Other significant independent predictors included emergency vs. routine admission (RR 3.3), cardiac septal defect (RR 7), preeclampsia (RR 3.3), and hypercoagulability (RR 3).

Dyslipidemia and hypertension doubled the rate of a thrombotic event. Hypertension, migraine, renal disease, heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure were also significant factors, increasing the rate of thrombosis by 40%-50%, Dr. Razmara said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“Our goal is development of targeted interventions for screening, prevention, and treatment of thrombosis related to pregnancy.”

Dr. Razmara had no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – The risk of a peripartum thrombotic event is rare, but significantly increased for women who have a cardioseptal defect. In a large national sample, the rate of thrombotic events was seven times higher among women with an atrial or ventral septal defect.

Advanced maternal age also was a significant independent predictor of this complication; among more than 7,000 women who developed a thrombotic complication, 81% were older than 45 years.

Dr. Ali Razmara of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, mined the National Inpatient Sample for data linking peripartum thrombotic events to patient demographics and medical comorbidities. His cohort comprised 4.3 million normal vaginal and cesarean deliveries from 2000 to 2010. Events of interest included transient ischemic attack, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, acute MI, and venous thromboembolism.

There were 7,242 peripartum thrombotic events (0.17%).The majority occurred in women who were older than 45 years (81%); white (58%); and admitted through the emergency department (67%). Women with thrombotic events were more likely to have hypertension (52% vs. 2%), dyslipidemia (26% vs. 0.52%), diabetes (20% vs. 2%), atrial fibrillation (10% vs. 0.23%), and heart failure (10% vs. 0.26%), he said at the International Stroke Conference.

A multivariate regression model controlled for patient demographics and comorbidities, including, among others, preeclampsia, hypercoagulable states, chorioamnionitis, renal and liver disease, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders including atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and atrial/ventral septal defects.

In a multivariate regression analysis, maternal age shook out as the most powerful independent risk factor; the rate of thrombosis was 91 times greater among women older than age 45 years.

Other significant independent predictors included emergency vs. routine admission (RR 3.3), cardiac septal defect (RR 7), preeclampsia (RR 3.3), and hypercoagulability (RR 3).

Dyslipidemia and hypertension doubled the rate of a thrombotic event. Hypertension, migraine, renal disease, heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure were also significant factors, increasing the rate of thrombosis by 40%-50%, Dr. Razmara said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“Our goal is development of targeted interventions for screening, prevention, and treatment of thrombosis related to pregnancy.”

Dr. Razmara had no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – The risk of a peripartum thrombotic event is rare, but significantly increased for women who have a cardioseptal defect. In a large national sample, the rate of thrombotic events was seven times higher among women with an atrial or ventral septal defect.

Advanced maternal age also was a significant independent predictor of this complication; among more than 7,000 women who developed a thrombotic complication, 81% were older than 45 years.

Dr. Ali Razmara of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, mined the National Inpatient Sample for data linking peripartum thrombotic events to patient demographics and medical comorbidities. His cohort comprised 4.3 million normal vaginal and cesarean deliveries from 2000 to 2010. Events of interest included transient ischemic attack, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, acute MI, and venous thromboembolism.

There were 7,242 peripartum thrombotic events (0.17%).The majority occurred in women who were older than 45 years (81%); white (58%); and admitted through the emergency department (67%). Women with thrombotic events were more likely to have hypertension (52% vs. 2%), dyslipidemia (26% vs. 0.52%), diabetes (20% vs. 2%), atrial fibrillation (10% vs. 0.23%), and heart failure (10% vs. 0.26%), he said at the International Stroke Conference.

A multivariate regression model controlled for patient demographics and comorbidities, including, among others, preeclampsia, hypercoagulable states, chorioamnionitis, renal and liver disease, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders including atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and atrial/ventral septal defects.

In a multivariate regression analysis, maternal age shook out as the most powerful independent risk factor; the rate of thrombosis was 91 times greater among women older than age 45 years.

Other significant independent predictors included emergency vs. routine admission (RR 3.3), cardiac septal defect (RR 7), preeclampsia (RR 3.3), and hypercoagulability (RR 3).

Dyslipidemia and hypertension doubled the rate of a thrombotic event. Hypertension, migraine, renal disease, heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure were also significant factors, increasing the rate of thrombosis by 40%-50%, Dr. Razmara said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“Our goal is development of targeted interventions for screening, prevention, and treatment of thrombosis related to pregnancy.”

Dr. Razmara had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Advanced maternal age and a cardioseptal defect increase the risk of a peripartum thrombotic event.

Major finding: The rate of peripartum thrombotic events was 0.17%; cardioseptal defects increased the rate of a peripartum thombotic event by more than seven times.

Data source: A sample that comprised 4.5 million deliveries during 2000-2010.

Disclosures: Dr. Razmara had no relevant disclosures.

Megestrol Acetate for CKD and Dialysis Patients

Q) Some of my CKD patients are malnourished; in fact, some of those on dialysis do not eat well and have low albumin levels. Previously in this column, it was stated that higher albumin levels (> 4 g/dL) confer survival benefits to dialysis patients. Should I consider prescribing megestrol acetate to improve appetite? If I do prescribe it, what dose is safe for CKD and dialysis patients?

Malnutrition affects one-third of dialysis patients,1 and malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) is common in those with stage 5 CKD. Albumin is used as an indicator of MICS in dialysis patients; however, since other factors (stress, infection, inflammation, comorbidities) affect nutritional status,2 serum albumin alone may not be sufficient to assess it.

In fact, a recent consensus statement on malnutrition from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition excluded serum albumin as a diagnostic characteristic; the criteria included percentage of energy requirement, percentage of weight loss and time frame, loss of body fat and muscle mass, presence of edema, and reduced grip strength.3 These may be better measures of malnutrition in dialysis patients and could be used as criteria for determining when to prescribe an appetite stimulant, such as megestrol acetate.

In recent years, megestrol acetate (an antineoplastic drug) has been used to improve appetite, weight, albumin levels, and MICS in patients receiving maintenance dialysis.1,4-6 Rammohan et al found significant increases in weight, BMI, body fat, triceps skinfold thickness, protein/energy intake, and serum albumin in 10 dialysis patients who took megestrol acetate (400 mg/d) for 16 weeks.4

Continue for megestrol acetate's effects >>

In a 20-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Yeh et al found significant increases in weight, body fat, and fat-free mass in elderly hemodialysis patients receiving megestrol acetate (800 mg/d). The treatment group also demonstrated greater improvement in ability to exercise.5

Monfared and colleagues looked specifically at megestrol acetate’s effect on serum albumin levels in dialysis patients.1 Using a much lower dose (40 mg bid for two months), they found a significant increase in serum albumin in the treatment group. Although an increase in appetite was noted, the researchers did not observe any significant change in total weight following treatment.1

In a letter to the editor of the Journal of Renal Nutrition, Golebiewska et al reported their use of megestrol acetate in maintenance hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients.6 Hypoalbuminemic patients were given megestrol acetate (160 mg/d). Significant increases in weight, BMI, subjective global assessment scores (a measure of nutritional status based on clinical indices such as weight, appetite, muscle, and fat mass), and serum albumin levels were seen. Only 12 of the 32 patients completed the study; the others dropped out due to adverse effects, including high intradialytic weight gain (the amount of fluid gained between dialysis sessions), dyspnea, diarrhea, and nausea.6

Currently, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the most effective dosage of megestrol acetate. Furthermore, evidence is lacking as to whether megestrol acetate–induced increases in appetite, oral intake, weight, and serum albumin level bestow any survival benefit or affect outcomes in dialysis patients.4 However, the increased sense of well-being a patient experiences when appetite returns and weight is restored may be worth the effort.

Luanne DiGuglielmo, MS, RD, CSR

DaVita Summit Renal Center

Mountainside, New Jersey

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

Q) Some of my CKD patients are malnourished; in fact, some of those on dialysis do not eat well and have low albumin levels. Previously in this column, it was stated that higher albumin levels (> 4 g/dL) confer survival benefits to dialysis patients. Should I consider prescribing megestrol acetate to improve appetite? If I do prescribe it, what dose is safe for CKD and dialysis patients?

Malnutrition affects one-third of dialysis patients,1 and malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) is common in those with stage 5 CKD. Albumin is used as an indicator of MICS in dialysis patients; however, since other factors (stress, infection, inflammation, comorbidities) affect nutritional status,2 serum albumin alone may not be sufficient to assess it.

In fact, a recent consensus statement on malnutrition from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition excluded serum albumin as a diagnostic characteristic; the criteria included percentage of energy requirement, percentage of weight loss and time frame, loss of body fat and muscle mass, presence of edema, and reduced grip strength.3 These may be better measures of malnutrition in dialysis patients and could be used as criteria for determining when to prescribe an appetite stimulant, such as megestrol acetate.

In recent years, megestrol acetate (an antineoplastic drug) has been used to improve appetite, weight, albumin levels, and MICS in patients receiving maintenance dialysis.1,4-6 Rammohan et al found significant increases in weight, BMI, body fat, triceps skinfold thickness, protein/energy intake, and serum albumin in 10 dialysis patients who took megestrol acetate (400 mg/d) for 16 weeks.4

Continue for megestrol acetate's effects >>

In a 20-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Yeh et al found significant increases in weight, body fat, and fat-free mass in elderly hemodialysis patients receiving megestrol acetate (800 mg/d). The treatment group also demonstrated greater improvement in ability to exercise.5

Monfared and colleagues looked specifically at megestrol acetate’s effect on serum albumin levels in dialysis patients.1 Using a much lower dose (40 mg bid for two months), they found a significant increase in serum albumin in the treatment group. Although an increase in appetite was noted, the researchers did not observe any significant change in total weight following treatment.1

In a letter to the editor of the Journal of Renal Nutrition, Golebiewska et al reported their use of megestrol acetate in maintenance hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients.6 Hypoalbuminemic patients were given megestrol acetate (160 mg/d). Significant increases in weight, BMI, subjective global assessment scores (a measure of nutritional status based on clinical indices such as weight, appetite, muscle, and fat mass), and serum albumin levels were seen. Only 12 of the 32 patients completed the study; the others dropped out due to adverse effects, including high intradialytic weight gain (the amount of fluid gained between dialysis sessions), dyspnea, diarrhea, and nausea.6

Currently, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the most effective dosage of megestrol acetate. Furthermore, evidence is lacking as to whether megestrol acetate–induced increases in appetite, oral intake, weight, and serum albumin level bestow any survival benefit or affect outcomes in dialysis patients.4 However, the increased sense of well-being a patient experiences when appetite returns and weight is restored may be worth the effort.

Luanne DiGuglielmo, MS, RD, CSR

DaVita Summit Renal Center

Mountainside, New Jersey

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

Q) Some of my CKD patients are malnourished; in fact, some of those on dialysis do not eat well and have low albumin levels. Previously in this column, it was stated that higher albumin levels (> 4 g/dL) confer survival benefits to dialysis patients. Should I consider prescribing megestrol acetate to improve appetite? If I do prescribe it, what dose is safe for CKD and dialysis patients?

Malnutrition affects one-third of dialysis patients,1 and malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) is common in those with stage 5 CKD. Albumin is used as an indicator of MICS in dialysis patients; however, since other factors (stress, infection, inflammation, comorbidities) affect nutritional status,2 serum albumin alone may not be sufficient to assess it.

In fact, a recent consensus statement on malnutrition from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition excluded serum albumin as a diagnostic characteristic; the criteria included percentage of energy requirement, percentage of weight loss and time frame, loss of body fat and muscle mass, presence of edema, and reduced grip strength.3 These may be better measures of malnutrition in dialysis patients and could be used as criteria for determining when to prescribe an appetite stimulant, such as megestrol acetate.

In recent years, megestrol acetate (an antineoplastic drug) has been used to improve appetite, weight, albumin levels, and MICS in patients receiving maintenance dialysis.1,4-6 Rammohan et al found significant increases in weight, BMI, body fat, triceps skinfold thickness, protein/energy intake, and serum albumin in 10 dialysis patients who took megestrol acetate (400 mg/d) for 16 weeks.4

Continue for megestrol acetate's effects >>

In a 20-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Yeh et al found significant increases in weight, body fat, and fat-free mass in elderly hemodialysis patients receiving megestrol acetate (800 mg/d). The treatment group also demonstrated greater improvement in ability to exercise.5

Monfared and colleagues looked specifically at megestrol acetate’s effect on serum albumin levels in dialysis patients.1 Using a much lower dose (40 mg bid for two months), they found a significant increase in serum albumin in the treatment group. Although an increase in appetite was noted, the researchers did not observe any significant change in total weight following treatment.1

In a letter to the editor of the Journal of Renal Nutrition, Golebiewska et al reported their use of megestrol acetate in maintenance hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients.6 Hypoalbuminemic patients were given megestrol acetate (160 mg/d). Significant increases in weight, BMI, subjective global assessment scores (a measure of nutritional status based on clinical indices such as weight, appetite, muscle, and fat mass), and serum albumin levels were seen. Only 12 of the 32 patients completed the study; the others dropped out due to adverse effects, including high intradialytic weight gain (the amount of fluid gained between dialysis sessions), dyspnea, diarrhea, and nausea.6

Currently, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the most effective dosage of megestrol acetate. Furthermore, evidence is lacking as to whether megestrol acetate–induced increases in appetite, oral intake, weight, and serum albumin level bestow any survival benefit or affect outcomes in dialysis patients.4 However, the increased sense of well-being a patient experiences when appetite returns and weight is restored may be worth the effort.

Luanne DiGuglielmo, MS, RD, CSR

DaVita Summit Renal Center

Mountainside, New Jersey

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.