User login

Artemisinin-resistant malaria found across Myanmar

Photo by James Gathany

Resistance to the antimalarial drug artemisinin is present in Myanmar and has reached within 25 km of the Indian border, according to research published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Researchers believe the spread of artemisinin-resistant malaria parasites into neighboring India would pose a serious threat to the global control and eradication of malaria.

And if drug resistance continues to spread, millions of lives could be at risk.

Kyaw Myo Tun, MD, of the Myanmar Oxford Clinical Research Unit in Yangon, Myanmar, and colleagues uncovered artemisinin resistance by analyzing parasite samples collected at 55 malaria treatment centers across Myanmar.

The group set out to determine if the samples carried mutations in specific regions of the parasite’s kelch gene (K13)—a known genetic marker of artemisinin resistance. And they confirmed the existance of resistant parasites in Homalin, in the Sagaing Region, which is located only 25 km from the Indian border.

“Myanmar is considered the frontline in the battle against artemisinin resistance, as it forms a gateway for resistance to spread to the rest of the world,” said Charles Woodrow, MD, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“With artemisinins, we are in the unusual position of having molecular markers for resistance before resistance has spread globally. The more we understand about the current situation in the border regions, the better prepared we are to adapt and implement strategies to overcome the spread of further drug resistance.”

The researchers obtained the DNA sequences of 940 samples of Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites from across Myanmar and neighboring border regions in Thailand and Bangladesh between 2013 and 2014. Of those 940 samples, 371 (39%) carried a resistance-conferring K13 mutation.

“We were able to gather patient samples rapidly across Myanmar, sometimes using discarded malaria blood diagnostic tests, and then test these immediately for the K13 marker, and so generate real-time information on the spread of resistance” said Mallika Imwong, PhD, of Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand.

Using this information, the researchers developed maps to display the predicted extent of artemisinin resistance determined by the prevalence of K13 mutations. The maps suggested the overall prevalence of K13 mutations was greater than 10% in large areas of the east and north of Myanmar, including areas close to the border with India.

“The identification of the K13 markers of resistance has transformed our ability to monitor the spread and emergence of artemisinin resistance,” said Philippe Guerin, MD, of the Worldwide Antimalarial Resistance Network in Oxford, UK.

“However, this study highlights that the pace at which artemisinin resistance is spreading or emerging is alarming. We need a more vigorous international effort to address this issue in border regions.” ![]()

Photo by James Gathany

Resistance to the antimalarial drug artemisinin is present in Myanmar and has reached within 25 km of the Indian border, according to research published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Researchers believe the spread of artemisinin-resistant malaria parasites into neighboring India would pose a serious threat to the global control and eradication of malaria.

And if drug resistance continues to spread, millions of lives could be at risk.

Kyaw Myo Tun, MD, of the Myanmar Oxford Clinical Research Unit in Yangon, Myanmar, and colleagues uncovered artemisinin resistance by analyzing parasite samples collected at 55 malaria treatment centers across Myanmar.

The group set out to determine if the samples carried mutations in specific regions of the parasite’s kelch gene (K13)—a known genetic marker of artemisinin resistance. And they confirmed the existance of resistant parasites in Homalin, in the Sagaing Region, which is located only 25 km from the Indian border.

“Myanmar is considered the frontline in the battle against artemisinin resistance, as it forms a gateway for resistance to spread to the rest of the world,” said Charles Woodrow, MD, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“With artemisinins, we are in the unusual position of having molecular markers for resistance before resistance has spread globally. The more we understand about the current situation in the border regions, the better prepared we are to adapt and implement strategies to overcome the spread of further drug resistance.”

The researchers obtained the DNA sequences of 940 samples of Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites from across Myanmar and neighboring border regions in Thailand and Bangladesh between 2013 and 2014. Of those 940 samples, 371 (39%) carried a resistance-conferring K13 mutation.

“We were able to gather patient samples rapidly across Myanmar, sometimes using discarded malaria blood diagnostic tests, and then test these immediately for the K13 marker, and so generate real-time information on the spread of resistance” said Mallika Imwong, PhD, of Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand.

Using this information, the researchers developed maps to display the predicted extent of artemisinin resistance determined by the prevalence of K13 mutations. The maps suggested the overall prevalence of K13 mutations was greater than 10% in large areas of the east and north of Myanmar, including areas close to the border with India.

“The identification of the K13 markers of resistance has transformed our ability to monitor the spread and emergence of artemisinin resistance,” said Philippe Guerin, MD, of the Worldwide Antimalarial Resistance Network in Oxford, UK.

“However, this study highlights that the pace at which artemisinin resistance is spreading or emerging is alarming. We need a more vigorous international effort to address this issue in border regions.” ![]()

Photo by James Gathany

Resistance to the antimalarial drug artemisinin is present in Myanmar and has reached within 25 km of the Indian border, according to research published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Researchers believe the spread of artemisinin-resistant malaria parasites into neighboring India would pose a serious threat to the global control and eradication of malaria.

And if drug resistance continues to spread, millions of lives could be at risk.

Kyaw Myo Tun, MD, of the Myanmar Oxford Clinical Research Unit in Yangon, Myanmar, and colleagues uncovered artemisinin resistance by analyzing parasite samples collected at 55 malaria treatment centers across Myanmar.

The group set out to determine if the samples carried mutations in specific regions of the parasite’s kelch gene (K13)—a known genetic marker of artemisinin resistance. And they confirmed the existance of resistant parasites in Homalin, in the Sagaing Region, which is located only 25 km from the Indian border.

“Myanmar is considered the frontline in the battle against artemisinin resistance, as it forms a gateway for resistance to spread to the rest of the world,” said Charles Woodrow, MD, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“With artemisinins, we are in the unusual position of having molecular markers for resistance before resistance has spread globally. The more we understand about the current situation in the border regions, the better prepared we are to adapt and implement strategies to overcome the spread of further drug resistance.”

The researchers obtained the DNA sequences of 940 samples of Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites from across Myanmar and neighboring border regions in Thailand and Bangladesh between 2013 and 2014. Of those 940 samples, 371 (39%) carried a resistance-conferring K13 mutation.

“We were able to gather patient samples rapidly across Myanmar, sometimes using discarded malaria blood diagnostic tests, and then test these immediately for the K13 marker, and so generate real-time information on the spread of resistance” said Mallika Imwong, PhD, of Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand.

Using this information, the researchers developed maps to display the predicted extent of artemisinin resistance determined by the prevalence of K13 mutations. The maps suggested the overall prevalence of K13 mutations was greater than 10% in large areas of the east and north of Myanmar, including areas close to the border with India.

“The identification of the K13 markers of resistance has transformed our ability to monitor the spread and emergence of artemisinin resistance,” said Philippe Guerin, MD, of the Worldwide Antimalarial Resistance Network in Oxford, UK.

“However, this study highlights that the pace at which artemisinin resistance is spreading or emerging is alarming. We need a more vigorous international effort to address this issue in border regions.” ![]()

Psychotic symptoms in children and adolescents

Some of the more disturbing behavioral symptoms to present are psychotic symptoms such as auditory or visual hallucination, delusions such as paranoia, or grossly disorganized thought content. Similar to the worry many families will have that a headache is the result of a brain tumor, concern that the psychotic symptoms represent the onset of schizophrenia often creates considerable alarm for families and primary care clinicians alike. In most cases, however, further evaluation suggests causes of psychotic or psychotic-like symptoms other than primary thought disorders.

Case Summary

Ella is an 8-year-old girl who has lived with her adoptive parents for 5 years. She was removed from the care of her birth parents by child protective services because of a history of abuse and neglect. Ella has struggled for many years with a variety of emotional-behavioral problems including inattention, frequent and intense angry outbursts, anxiety, and mood instability. She currently takes a long-acting methylphenidate preparation. Her parents present to her pediatrician because Ella is now reporting that she is seeing “shadows” in her room at night that frighten her. She also has lately stated that she hears a “mean voice” in her head that tells her that she is a bad person. The parents are not aware of specific psychiatric diagnoses in the birth parents, but state that they did have a history of “mental health problems” and were homeless at times. The parents are worried that these symptoms might be early signs of schizophrenia.

Discussion

Accumulating data demonstrates that while psychotic symptoms are relatively common in children and adolescents, childhood-onset schizophrenia actually is quite rare. Estimates of psychotic symptoms in otherwise healthy children have been as high as 5%, with a recent study of adolescents reporting that 15% of the sample reported hearing a voice that commented on what the person was thinking or feeling (Schizophr. Bull. 2014;40:868-77). At the same time, the incidence of childhood-onset schizophrenia is thought to be less than 0.04% based on data from a group at the National Institute of Mental Health (Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013;22:539-55). This group has been actively evaluating and recruiting children with early onset psychosis and finds that more than 90% of their referrals end up with a diagnosis other than schizophrenia.

The differential diagnosis for psychosis is extensive. In terms of nonpsychiatric diagnoses (what in the past were referred to as “organic” causes), possible etiologies include CNS tumors, encephalitis, metabolic disorders, and various genetic conditions, among others. Some medications, such as corticosteroids, stimulants, and anticholinergic medications, also can result in psychotic symptoms, especially at higher doses. While the acute presence of psychotic symptoms in an otherwise healthy child should certainly prompt suspicion of a possible delirium or other nonpsychiatric condition, it is important to note that some of the above etiologies can be associated with other types of behavioral disturbances; thus, the presence of earlier behavioral problems does not rule out the possibility that one of these nonpsychiatric causes is present.

Clinical tip: From our experience at a busy outpatient child psychiatry clinic, it is often not clear whose job it is to rule out nonpsychiatric causes of behavior problems. There is a risk that the psychiatrist assumes that the pediatrician has done this work-up while the pediatrician assumes that this component is part of a psychiatric evaluation. Communication about this role is important. If a third specialist is needed, such as a pediatric neurologist or geneticist, then it is important to clarify who will initiate that consultation as well.

The differential for psychotic symptoms also includes a number of psychiatric conditions other than schizophrenia, such as bipolar or unipolar depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, autism, or an eating disorder. Substance use, particularly cannabis, also needs to be strongly considered. A child psychiatrist or other mental health professional can be very helpful here to help decipher what are sometimes subtle differences in the nature and content of the psychotic symptoms between various diagnoses. Receptive and expressive language disorders also can be present in many youth who experience psychotic symptoms.

The decision of if and when to begin treatment with an antipsychotic medication can be a difficult one and should be made very thoughtfully and with the help of consultation. The concern that a longer duration of untreated psychosis may be related to a more protracted course needs to be weighed against other data suggesting that using as little medication as possible may predict higher levels of future functioning (JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:913-20). It is important to note that there are many nonpharmacological interventions that also can be helpful, including individual and family psychotherapy, family education, school modifications, and other social supports.

Case follow-up

Ella was referred to a child psychologist who performed an evaluation and thought that the patient’s symptoms were most representative of posttraumatic stress disorder. She began treatment with trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) which led to a reduction in both her anxiety and psychotic-sounding symptoms.

Dr. Rettew is an associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Dr. Rettew said he has no relevant financial disclosures. Follow him on Twitter @pedipsych. E-mail him at [email protected].

Some of the more disturbing behavioral symptoms to present are psychotic symptoms such as auditory or visual hallucination, delusions such as paranoia, or grossly disorganized thought content. Similar to the worry many families will have that a headache is the result of a brain tumor, concern that the psychotic symptoms represent the onset of schizophrenia often creates considerable alarm for families and primary care clinicians alike. In most cases, however, further evaluation suggests causes of psychotic or psychotic-like symptoms other than primary thought disorders.

Case Summary

Ella is an 8-year-old girl who has lived with her adoptive parents for 5 years. She was removed from the care of her birth parents by child protective services because of a history of abuse and neglect. Ella has struggled for many years with a variety of emotional-behavioral problems including inattention, frequent and intense angry outbursts, anxiety, and mood instability. She currently takes a long-acting methylphenidate preparation. Her parents present to her pediatrician because Ella is now reporting that she is seeing “shadows” in her room at night that frighten her. She also has lately stated that she hears a “mean voice” in her head that tells her that she is a bad person. The parents are not aware of specific psychiatric diagnoses in the birth parents, but state that they did have a history of “mental health problems” and were homeless at times. The parents are worried that these symptoms might be early signs of schizophrenia.

Discussion

Accumulating data demonstrates that while psychotic symptoms are relatively common in children and adolescents, childhood-onset schizophrenia actually is quite rare. Estimates of psychotic symptoms in otherwise healthy children have been as high as 5%, with a recent study of adolescents reporting that 15% of the sample reported hearing a voice that commented on what the person was thinking or feeling (Schizophr. Bull. 2014;40:868-77). At the same time, the incidence of childhood-onset schizophrenia is thought to be less than 0.04% based on data from a group at the National Institute of Mental Health (Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013;22:539-55). This group has been actively evaluating and recruiting children with early onset psychosis and finds that more than 90% of their referrals end up with a diagnosis other than schizophrenia.

The differential diagnosis for psychosis is extensive. In terms of nonpsychiatric diagnoses (what in the past were referred to as “organic” causes), possible etiologies include CNS tumors, encephalitis, metabolic disorders, and various genetic conditions, among others. Some medications, such as corticosteroids, stimulants, and anticholinergic medications, also can result in psychotic symptoms, especially at higher doses. While the acute presence of psychotic symptoms in an otherwise healthy child should certainly prompt suspicion of a possible delirium or other nonpsychiatric condition, it is important to note that some of the above etiologies can be associated with other types of behavioral disturbances; thus, the presence of earlier behavioral problems does not rule out the possibility that one of these nonpsychiatric causes is present.

Clinical tip: From our experience at a busy outpatient child psychiatry clinic, it is often not clear whose job it is to rule out nonpsychiatric causes of behavior problems. There is a risk that the psychiatrist assumes that the pediatrician has done this work-up while the pediatrician assumes that this component is part of a psychiatric evaluation. Communication about this role is important. If a third specialist is needed, such as a pediatric neurologist or geneticist, then it is important to clarify who will initiate that consultation as well.

The differential for psychotic symptoms also includes a number of psychiatric conditions other than schizophrenia, such as bipolar or unipolar depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, autism, or an eating disorder. Substance use, particularly cannabis, also needs to be strongly considered. A child psychiatrist or other mental health professional can be very helpful here to help decipher what are sometimes subtle differences in the nature and content of the psychotic symptoms between various diagnoses. Receptive and expressive language disorders also can be present in many youth who experience psychotic symptoms.

The decision of if and when to begin treatment with an antipsychotic medication can be a difficult one and should be made very thoughtfully and with the help of consultation. The concern that a longer duration of untreated psychosis may be related to a more protracted course needs to be weighed against other data suggesting that using as little medication as possible may predict higher levels of future functioning (JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:913-20). It is important to note that there are many nonpharmacological interventions that also can be helpful, including individual and family psychotherapy, family education, school modifications, and other social supports.

Case follow-up

Ella was referred to a child psychologist who performed an evaluation and thought that the patient’s symptoms were most representative of posttraumatic stress disorder. She began treatment with trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) which led to a reduction in both her anxiety and psychotic-sounding symptoms.

Dr. Rettew is an associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Dr. Rettew said he has no relevant financial disclosures. Follow him on Twitter @pedipsych. E-mail him at [email protected].

Some of the more disturbing behavioral symptoms to present are psychotic symptoms such as auditory or visual hallucination, delusions such as paranoia, or grossly disorganized thought content. Similar to the worry many families will have that a headache is the result of a brain tumor, concern that the psychotic symptoms represent the onset of schizophrenia often creates considerable alarm for families and primary care clinicians alike. In most cases, however, further evaluation suggests causes of psychotic or psychotic-like symptoms other than primary thought disorders.

Case Summary

Ella is an 8-year-old girl who has lived with her adoptive parents for 5 years. She was removed from the care of her birth parents by child protective services because of a history of abuse and neglect. Ella has struggled for many years with a variety of emotional-behavioral problems including inattention, frequent and intense angry outbursts, anxiety, and mood instability. She currently takes a long-acting methylphenidate preparation. Her parents present to her pediatrician because Ella is now reporting that she is seeing “shadows” in her room at night that frighten her. She also has lately stated that she hears a “mean voice” in her head that tells her that she is a bad person. The parents are not aware of specific psychiatric diagnoses in the birth parents, but state that they did have a history of “mental health problems” and were homeless at times. The parents are worried that these symptoms might be early signs of schizophrenia.

Discussion

Accumulating data demonstrates that while psychotic symptoms are relatively common in children and adolescents, childhood-onset schizophrenia actually is quite rare. Estimates of psychotic symptoms in otherwise healthy children have been as high as 5%, with a recent study of adolescents reporting that 15% of the sample reported hearing a voice that commented on what the person was thinking or feeling (Schizophr. Bull. 2014;40:868-77). At the same time, the incidence of childhood-onset schizophrenia is thought to be less than 0.04% based on data from a group at the National Institute of Mental Health (Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013;22:539-55). This group has been actively evaluating and recruiting children with early onset psychosis and finds that more than 90% of their referrals end up with a diagnosis other than schizophrenia.

The differential diagnosis for psychosis is extensive. In terms of nonpsychiatric diagnoses (what in the past were referred to as “organic” causes), possible etiologies include CNS tumors, encephalitis, metabolic disorders, and various genetic conditions, among others. Some medications, such as corticosteroids, stimulants, and anticholinergic medications, also can result in psychotic symptoms, especially at higher doses. While the acute presence of psychotic symptoms in an otherwise healthy child should certainly prompt suspicion of a possible delirium or other nonpsychiatric condition, it is important to note that some of the above etiologies can be associated with other types of behavioral disturbances; thus, the presence of earlier behavioral problems does not rule out the possibility that one of these nonpsychiatric causes is present.

Clinical tip: From our experience at a busy outpatient child psychiatry clinic, it is often not clear whose job it is to rule out nonpsychiatric causes of behavior problems. There is a risk that the psychiatrist assumes that the pediatrician has done this work-up while the pediatrician assumes that this component is part of a psychiatric evaluation. Communication about this role is important. If a third specialist is needed, such as a pediatric neurologist or geneticist, then it is important to clarify who will initiate that consultation as well.

The differential for psychotic symptoms also includes a number of psychiatric conditions other than schizophrenia, such as bipolar or unipolar depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, autism, or an eating disorder. Substance use, particularly cannabis, also needs to be strongly considered. A child psychiatrist or other mental health professional can be very helpful here to help decipher what are sometimes subtle differences in the nature and content of the psychotic symptoms between various diagnoses. Receptive and expressive language disorders also can be present in many youth who experience psychotic symptoms.

The decision of if and when to begin treatment with an antipsychotic medication can be a difficult one and should be made very thoughtfully and with the help of consultation. The concern that a longer duration of untreated psychosis may be related to a more protracted course needs to be weighed against other data suggesting that using as little medication as possible may predict higher levels of future functioning (JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:913-20). It is important to note that there are many nonpharmacological interventions that also can be helpful, including individual and family psychotherapy, family education, school modifications, and other social supports.

Case follow-up

Ella was referred to a child psychologist who performed an evaluation and thought that the patient’s symptoms were most representative of posttraumatic stress disorder. She began treatment with trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) which led to a reduction in both her anxiety and psychotic-sounding symptoms.

Dr. Rettew is an associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Dr. Rettew said he has no relevant financial disclosures. Follow him on Twitter @pedipsych. E-mail him at [email protected].

EC expands indication for lenalidomide in MM

Photo courtesy of Celgene

The European Commission (EC) has expanded the marketing authorization for lenalidomide (Revlimid), just 2 days after the US Food and Drug Administration did the same.

Lenalidomide is now approved in the European Union (EU) to treat adults with previously untreated multiple myeloma (MM) who are not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant. These patients can receive the drug continuously until

disease progression.

Lenalidomide was already approved in the EU for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat adults with MM who have received at least 1 prior therapy.

Lenalidomide is also approved in the EU to treat patients with transfusion-dependent anemia due to low- or intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes associated with 5q deletion when other therapeutic options are insufficient or inadequate.

“Having a new treatment option now available for patients newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma is a real step forward,” said Thierry Facon, MD, of CHRU Lille in France.

“Treating patients continuously until disease progression is supported by several clinical studies and will have an important impact on how we manage the disease over the long-term.”

The EC’s decision to extend the approved use of lenalidomide was based on the results of 2 studies: MM-015 and MM-020, also known as FIRST.

The FIRST trial

In the phase 3 FIRST trial, researchers enrolled 1623 patients who were newly diagnosed with MM and not eligible for transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), 18 cycles of lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd18) for 72 weeks (n=541), or melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT) for 72 weeks (n=547).

Response rates were significantly better with continuous Rd (75%) and Rd18 (73%) than with MPT (62%, P<0.001 for both comparisons). Complete response rates were 15%, 14%, and 9%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival was 25.5 months with continuous Rd, 20.7 months with Rd18, and 21.2 months with MPT.

This resulted in a 28% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients treated with continuous Rd compared with those treated with MPT (hazard ratio[HR]=0.72, P<0.001) and a 30% reduction compared with Rd18 (HR=0.70, P<0.001).

The pre-planned interim analysis of overall survival showed a 22% reduction in the risk of death for continuous Rd vs MPT (HR=0.78, P=0.02), but the difference did not cross the pre-specified superiority boundary (P<0.0096).

Adverse events reported in 20% or more of patients in the continuous Rd, Rd18, or MPT arms included diarrhea (45.5%, 38.5%, 16.5%), anemia (43.8%, 35.7%, 42.3%), neutropenia (35.0%, 33.0%, 60.6%), fatigue (32.5%, 32.8%, 28.5%), back pain (32.0%, 26.9%, 21.4%), insomnia (27.6%, 23.5%, 9.8%), asthenia (28.2%, 22.8%, 22.9%), rash (26.1%, 28.0%, 19.4%), decreased appetite (23.1%, 21.3%, 13.3%), cough (22.7%, 17.4%, 12.6%), pyrexia (21.4%, 18.9%, 14.0%), muscle spasms (20.5%, 18.9%, 11.3%), and abdominal pain (20.5%, 14.4%, 11.1%).

The incidence of invasive second primary malignancies was 3% in patients taking continuous Rd, 6% in patients taking Rd18, and 5% in those taking MPT. The overall incidence of solid tumors was identical in the continuous Rd and MPT arms (3%) and 5% in the Rd18 arm.

The MM-015 trial

In the phase 3 MM-015 study, researchers enrolled 459 patients who were 65 or older and newly diagnosed with MM.

The team compared melphalan-prednisone-lenalidomide induction followed by lenalidomide maintenance (MPR-R) with melphalan-prednisone-lenalidomide (MPR) or melphalan-prednisone (MP) followed by placebo maintenance.

Patients who received MPR-R or MPR had significantly better response rates than patients who received MP, at 77%, 68%, and 50%, respectively (P<0.001 and P=0.002, respectively, for the comparison with MP).

And the median progression-free survival was significantly longer with MPR-R (31 months) than with MPR (14 months, HR=0.49, P<0.001) or MP (13 months, HR=0.40, P<0.001).

During induction, the most frequent adverse events were hematologic. Grade 4 neutropenia occurred in 35% of patients in the MPR-R arm, 32% in the MPR arm, and 8% in the MP arm. The 3-year rate of second primary malignancies was 7%, 7%, and 3%, respectively. ![]()

Photo courtesy of Celgene

The European Commission (EC) has expanded the marketing authorization for lenalidomide (Revlimid), just 2 days after the US Food and Drug Administration did the same.

Lenalidomide is now approved in the European Union (EU) to treat adults with previously untreated multiple myeloma (MM) who are not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant. These patients can receive the drug continuously until

disease progression.

Lenalidomide was already approved in the EU for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat adults with MM who have received at least 1 prior therapy.

Lenalidomide is also approved in the EU to treat patients with transfusion-dependent anemia due to low- or intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes associated with 5q deletion when other therapeutic options are insufficient or inadequate.

“Having a new treatment option now available for patients newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma is a real step forward,” said Thierry Facon, MD, of CHRU Lille in France.

“Treating patients continuously until disease progression is supported by several clinical studies and will have an important impact on how we manage the disease over the long-term.”

The EC’s decision to extend the approved use of lenalidomide was based on the results of 2 studies: MM-015 and MM-020, also known as FIRST.

The FIRST trial

In the phase 3 FIRST trial, researchers enrolled 1623 patients who were newly diagnosed with MM and not eligible for transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), 18 cycles of lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd18) for 72 weeks (n=541), or melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT) for 72 weeks (n=547).

Response rates were significantly better with continuous Rd (75%) and Rd18 (73%) than with MPT (62%, P<0.001 for both comparisons). Complete response rates were 15%, 14%, and 9%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival was 25.5 months with continuous Rd, 20.7 months with Rd18, and 21.2 months with MPT.

This resulted in a 28% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients treated with continuous Rd compared with those treated with MPT (hazard ratio[HR]=0.72, P<0.001) and a 30% reduction compared with Rd18 (HR=0.70, P<0.001).

The pre-planned interim analysis of overall survival showed a 22% reduction in the risk of death for continuous Rd vs MPT (HR=0.78, P=0.02), but the difference did not cross the pre-specified superiority boundary (P<0.0096).

Adverse events reported in 20% or more of patients in the continuous Rd, Rd18, or MPT arms included diarrhea (45.5%, 38.5%, 16.5%), anemia (43.8%, 35.7%, 42.3%), neutropenia (35.0%, 33.0%, 60.6%), fatigue (32.5%, 32.8%, 28.5%), back pain (32.0%, 26.9%, 21.4%), insomnia (27.6%, 23.5%, 9.8%), asthenia (28.2%, 22.8%, 22.9%), rash (26.1%, 28.0%, 19.4%), decreased appetite (23.1%, 21.3%, 13.3%), cough (22.7%, 17.4%, 12.6%), pyrexia (21.4%, 18.9%, 14.0%), muscle spasms (20.5%, 18.9%, 11.3%), and abdominal pain (20.5%, 14.4%, 11.1%).

The incidence of invasive second primary malignancies was 3% in patients taking continuous Rd, 6% in patients taking Rd18, and 5% in those taking MPT. The overall incidence of solid tumors was identical in the continuous Rd and MPT arms (3%) and 5% in the Rd18 arm.

The MM-015 trial

In the phase 3 MM-015 study, researchers enrolled 459 patients who were 65 or older and newly diagnosed with MM.

The team compared melphalan-prednisone-lenalidomide induction followed by lenalidomide maintenance (MPR-R) with melphalan-prednisone-lenalidomide (MPR) or melphalan-prednisone (MP) followed by placebo maintenance.

Patients who received MPR-R or MPR had significantly better response rates than patients who received MP, at 77%, 68%, and 50%, respectively (P<0.001 and P=0.002, respectively, for the comparison with MP).

And the median progression-free survival was significantly longer with MPR-R (31 months) than with MPR (14 months, HR=0.49, P<0.001) or MP (13 months, HR=0.40, P<0.001).

During induction, the most frequent adverse events were hematologic. Grade 4 neutropenia occurred in 35% of patients in the MPR-R arm, 32% in the MPR arm, and 8% in the MP arm. The 3-year rate of second primary malignancies was 7%, 7%, and 3%, respectively. ![]()

Photo courtesy of Celgene

The European Commission (EC) has expanded the marketing authorization for lenalidomide (Revlimid), just 2 days after the US Food and Drug Administration did the same.

Lenalidomide is now approved in the European Union (EU) to treat adults with previously untreated multiple myeloma (MM) who are not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant. These patients can receive the drug continuously until

disease progression.

Lenalidomide was already approved in the EU for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat adults with MM who have received at least 1 prior therapy.

Lenalidomide is also approved in the EU to treat patients with transfusion-dependent anemia due to low- or intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes associated with 5q deletion when other therapeutic options are insufficient or inadequate.

“Having a new treatment option now available for patients newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma is a real step forward,” said Thierry Facon, MD, of CHRU Lille in France.

“Treating patients continuously until disease progression is supported by several clinical studies and will have an important impact on how we manage the disease over the long-term.”

The EC’s decision to extend the approved use of lenalidomide was based on the results of 2 studies: MM-015 and MM-020, also known as FIRST.

The FIRST trial

In the phase 3 FIRST trial, researchers enrolled 1623 patients who were newly diagnosed with MM and not eligible for transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), 18 cycles of lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd18) for 72 weeks (n=541), or melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT) for 72 weeks (n=547).

Response rates were significantly better with continuous Rd (75%) and Rd18 (73%) than with MPT (62%, P<0.001 for both comparisons). Complete response rates were 15%, 14%, and 9%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival was 25.5 months with continuous Rd, 20.7 months with Rd18, and 21.2 months with MPT.

This resulted in a 28% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients treated with continuous Rd compared with those treated with MPT (hazard ratio[HR]=0.72, P<0.001) and a 30% reduction compared with Rd18 (HR=0.70, P<0.001).

The pre-planned interim analysis of overall survival showed a 22% reduction in the risk of death for continuous Rd vs MPT (HR=0.78, P=0.02), but the difference did not cross the pre-specified superiority boundary (P<0.0096).

Adverse events reported in 20% or more of patients in the continuous Rd, Rd18, or MPT arms included diarrhea (45.5%, 38.5%, 16.5%), anemia (43.8%, 35.7%, 42.3%), neutropenia (35.0%, 33.0%, 60.6%), fatigue (32.5%, 32.8%, 28.5%), back pain (32.0%, 26.9%, 21.4%), insomnia (27.6%, 23.5%, 9.8%), asthenia (28.2%, 22.8%, 22.9%), rash (26.1%, 28.0%, 19.4%), decreased appetite (23.1%, 21.3%, 13.3%), cough (22.7%, 17.4%, 12.6%), pyrexia (21.4%, 18.9%, 14.0%), muscle spasms (20.5%, 18.9%, 11.3%), and abdominal pain (20.5%, 14.4%, 11.1%).

The incidence of invasive second primary malignancies was 3% in patients taking continuous Rd, 6% in patients taking Rd18, and 5% in those taking MPT. The overall incidence of solid tumors was identical in the continuous Rd and MPT arms (3%) and 5% in the Rd18 arm.

The MM-015 trial

In the phase 3 MM-015 study, researchers enrolled 459 patients who were 65 or older and newly diagnosed with MM.

The team compared melphalan-prednisone-lenalidomide induction followed by lenalidomide maintenance (MPR-R) with melphalan-prednisone-lenalidomide (MPR) or melphalan-prednisone (MP) followed by placebo maintenance.

Patients who received MPR-R or MPR had significantly better response rates than patients who received MP, at 77%, 68%, and 50%, respectively (P<0.001 and P=0.002, respectively, for the comparison with MP).

And the median progression-free survival was significantly longer with MPR-R (31 months) than with MPR (14 months, HR=0.49, P<0.001) or MP (13 months, HR=0.40, P<0.001).

During induction, the most frequent adverse events were hematologic. Grade 4 neutropenia occurred in 35% of patients in the MPR-R arm, 32% in the MPR arm, and 8% in the MP arm. The 3-year rate of second primary malignancies was 7%, 7%, and 3%, respectively. ![]()

March 2015 Quiz 2

ANSWER: B

Critique

This patient has evidence of an acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (known as Ogilvie’s syndrome). This is seen most commonly after non-GI related surgeries such as cardiac or orthopedic surgeries. The exact etiology is uncertain but increased inhibitory sympathetic and/or decreased stimulatory, parasympathetic innervations of the distal colon have been incriminated. The most appropriate first step in management of this patient is a thorough clinical evaluation to ensure there is no evidence of peritonitis to suggest a perforation complication. The next step is to exclude an obstruction and the CT had no clear evidence of obstruction. One could consider a water soluble enema to exclude obstruction but should avoid the use of barium in the event of a perforation. The next steps include restricting all possible culprit medications such as opiates and anticholinergics, encouraging ambulation (although often clinical circumstances limit ambulation), and correcting any potential electrolyte abnormalities.

Placement of a nasogastric tube to low intermittent suction, keeping the patient NPO (nothing by mouth), and placing a rectal tube to gravity are practical measure that can facilitate decompression. If the patient cannot ambulate, some clinicians also advocate rotating the patient into the right lateral decubitus position for several hours, alternating with the supine position, to facilitate gas evacuation. Such conservative measures are appropriate if there is no evidence of clinical toxicity or progression of the condition. Cecal diameters may be monitored on plain abdominal x-rays. If there is no clinical response to the above measures, then further treatments may be considered. Use of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor has been shown to be beneficial in a placebo-controlled trial. If use of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor is unsuccessful, colonic decompression can be considered though this typically provides only transient benefit. Finally, an emergent cecostomy can be considered if colonic decompression is unsuccessful.

References

1. De Giorgio R., Cogliandro R.F., Barbara G., Corinaldesi R., Stanghellini V. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: clinical features, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2011;40:787-807.

2. Ponec R.J., Saunders M.D., KImmey M.B. Neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:137-41.

- Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut 2005;54:449–54.

- Smith J, Woodcock A, Houghton L. New developments in reflux-associated cough. Lung 2010;188(Suppl1)S81-6.

- Sifrim D, Barnes N. GERD related chronic cough: How to identify patients who will respond to antireflux therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;44:234-6.

ANSWER: B

Critique

This patient has evidence of an acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (known as Ogilvie’s syndrome). This is seen most commonly after non-GI related surgeries such as cardiac or orthopedic surgeries. The exact etiology is uncertain but increased inhibitory sympathetic and/or decreased stimulatory, parasympathetic innervations of the distal colon have been incriminated. The most appropriate first step in management of this patient is a thorough clinical evaluation to ensure there is no evidence of peritonitis to suggest a perforation complication. The next step is to exclude an obstruction and the CT had no clear evidence of obstruction. One could consider a water soluble enema to exclude obstruction but should avoid the use of barium in the event of a perforation. The next steps include restricting all possible culprit medications such as opiates and anticholinergics, encouraging ambulation (although often clinical circumstances limit ambulation), and correcting any potential electrolyte abnormalities.

Placement of a nasogastric tube to low intermittent suction, keeping the patient NPO (nothing by mouth), and placing a rectal tube to gravity are practical measure that can facilitate decompression. If the patient cannot ambulate, some clinicians also advocate rotating the patient into the right lateral decubitus position for several hours, alternating with the supine position, to facilitate gas evacuation. Such conservative measures are appropriate if there is no evidence of clinical toxicity or progression of the condition. Cecal diameters may be monitored on plain abdominal x-rays. If there is no clinical response to the above measures, then further treatments may be considered. Use of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor has been shown to be beneficial in a placebo-controlled trial. If use of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor is unsuccessful, colonic decompression can be considered though this typically provides only transient benefit. Finally, an emergent cecostomy can be considered if colonic decompression is unsuccessful.

References

1. De Giorgio R., Cogliandro R.F., Barbara G., Corinaldesi R., Stanghellini V. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: clinical features, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2011;40:787-807.

2. Ponec R.J., Saunders M.D., KImmey M.B. Neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:137-41.

ANSWER: B

Critique

This patient has evidence of an acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (known as Ogilvie’s syndrome). This is seen most commonly after non-GI related surgeries such as cardiac or orthopedic surgeries. The exact etiology is uncertain but increased inhibitory sympathetic and/or decreased stimulatory, parasympathetic innervations of the distal colon have been incriminated. The most appropriate first step in management of this patient is a thorough clinical evaluation to ensure there is no evidence of peritonitis to suggest a perforation complication. The next step is to exclude an obstruction and the CT had no clear evidence of obstruction. One could consider a water soluble enema to exclude obstruction but should avoid the use of barium in the event of a perforation. The next steps include restricting all possible culprit medications such as opiates and anticholinergics, encouraging ambulation (although often clinical circumstances limit ambulation), and correcting any potential electrolyte abnormalities.

Placement of a nasogastric tube to low intermittent suction, keeping the patient NPO (nothing by mouth), and placing a rectal tube to gravity are practical measure that can facilitate decompression. If the patient cannot ambulate, some clinicians also advocate rotating the patient into the right lateral decubitus position for several hours, alternating with the supine position, to facilitate gas evacuation. Such conservative measures are appropriate if there is no evidence of clinical toxicity or progression of the condition. Cecal diameters may be monitored on plain abdominal x-rays. If there is no clinical response to the above measures, then further treatments may be considered. Use of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor has been shown to be beneficial in a placebo-controlled trial. If use of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor is unsuccessful, colonic decompression can be considered though this typically provides only transient benefit. Finally, an emergent cecostomy can be considered if colonic decompression is unsuccessful.

References

1. De Giorgio R., Cogliandro R.F., Barbara G., Corinaldesi R., Stanghellini V. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: clinical features, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2011;40:787-807.

2. Ponec R.J., Saunders M.D., KImmey M.B. Neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:137-41.

- Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut 2005;54:449–54.

- Smith J, Woodcock A, Houghton L. New developments in reflux-associated cough. Lung 2010;188(Suppl1)S81-6.

- Sifrim D, Barnes N. GERD related chronic cough: How to identify patients who will respond to antireflux therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;44:234-6.

- Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut 2005;54:449–54.

- Smith J, Woodcock A, Houghton L. New developments in reflux-associated cough. Lung 2010;188(Suppl1)S81-6.

- Sifrim D, Barnes N. GERD related chronic cough: How to identify patients who will respond to antireflux therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;44:234-6.

March 2015 Quiz 1

ANSWER: D

Critique

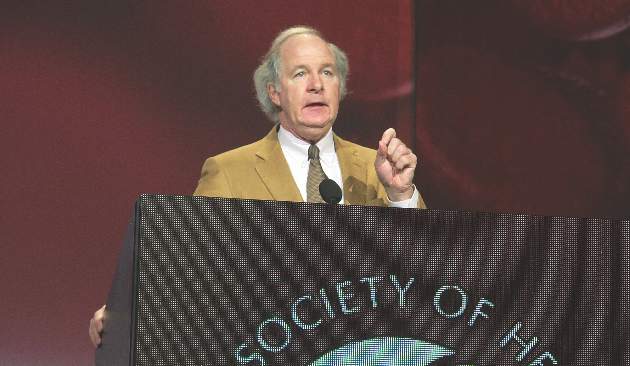

The patient is most likely to have Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES), a condition caused by a gastrinoma. In 25% of cases, ZES is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1). Clinical features of MEN-1 include gastrinoma or other islet cell tumor, hyperparathyroidism, and anterior pituitary tumors. ZES should be especially considered in a patient with multiple, refractory, or recurrent peptic ulcer disease, especially if accompanied by diarrhea or hypercalcemia. Diarrhea is often a predominant symptom and is caused by the large volume of acid that inactivates pancreatic lipase and damages the absorptive mucosa of the proximal gut. Tests to diagnose ZES include serum gastrin radioimmunoassay, secretin stimulation test, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, and endoscopic ultrasound. Almost all gastrinomas contain somatostatin receptors on the gastrin cells and somatostatin scintigraphy using [111In-DPTA-Dphe1]-octreotide is considered the initial localization study of choice. It has 71% sensitivity and 86% specificity for primary tumors and 92% sensitivity for detection of metastatic disease.

References

1. Murugesan S.V., Varro A., Pritchard D.M. Review article: Strategies to determine whether hypergastrinaemia is due to Zollinger-Ellison syndrome rather than a more common benign cause. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;29:1055-68.

2. Jensen R.T., Niederle B., Mitry E., et al. Frascati Consensus Conference; European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Gastrinoma (duodenal and pancreatic). Neuroendocrinology 2006;84:173-82.

3. Hung, P.D., Schubert, M.L., Mihas, A.A. Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology 2003;6:163-70.

4. Gibril F., Reynolds J.C., Doppman J.L., et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: Its sensitivity compared with that of other imaging methods in detecting primary and metastatic gastrinomas - A prospective study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;125:26-34.

5. Hung, P.D., Schubert, M.L., Mihas, A.A. Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology 2003;6:163-70.

- Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut 2005;54:449–54.

- Smith J, Woodcock A, Houghton L. New developments in reflux-associated cough. Lung 2010;188(Suppl1)S81-6.

- Sifrim D, Barnes N. GERD related chronic cough: How to identify patients who will respond to antireflux therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;44:234-6.

ANSWER: D

Critique

The patient is most likely to have Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES), a condition caused by a gastrinoma. In 25% of cases, ZES is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1). Clinical features of MEN-1 include gastrinoma or other islet cell tumor, hyperparathyroidism, and anterior pituitary tumors. ZES should be especially considered in a patient with multiple, refractory, or recurrent peptic ulcer disease, especially if accompanied by diarrhea or hypercalcemia. Diarrhea is often a predominant symptom and is caused by the large volume of acid that inactivates pancreatic lipase and damages the absorptive mucosa of the proximal gut. Tests to diagnose ZES include serum gastrin radioimmunoassay, secretin stimulation test, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, and endoscopic ultrasound. Almost all gastrinomas contain somatostatin receptors on the gastrin cells and somatostatin scintigraphy using [111In-DPTA-Dphe1]-octreotide is considered the initial localization study of choice. It has 71% sensitivity and 86% specificity for primary tumors and 92% sensitivity for detection of metastatic disease.

References

1. Murugesan S.V., Varro A., Pritchard D.M. Review article: Strategies to determine whether hypergastrinaemia is due to Zollinger-Ellison syndrome rather than a more common benign cause. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;29:1055-68.

2. Jensen R.T., Niederle B., Mitry E., et al. Frascati Consensus Conference; European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Gastrinoma (duodenal and pancreatic). Neuroendocrinology 2006;84:173-82.

3. Hung, P.D., Schubert, M.L., Mihas, A.A. Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology 2003;6:163-70.

4. Gibril F., Reynolds J.C., Doppman J.L., et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: Its sensitivity compared with that of other imaging methods in detecting primary and metastatic gastrinomas - A prospective study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;125:26-34.

5. Hung, P.D., Schubert, M.L., Mihas, A.A. Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology 2003;6:163-70.

ANSWER: D

Critique

The patient is most likely to have Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES), a condition caused by a gastrinoma. In 25% of cases, ZES is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1). Clinical features of MEN-1 include gastrinoma or other islet cell tumor, hyperparathyroidism, and anterior pituitary tumors. ZES should be especially considered in a patient with multiple, refractory, or recurrent peptic ulcer disease, especially if accompanied by diarrhea or hypercalcemia. Diarrhea is often a predominant symptom and is caused by the large volume of acid that inactivates pancreatic lipase and damages the absorptive mucosa of the proximal gut. Tests to diagnose ZES include serum gastrin radioimmunoassay, secretin stimulation test, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, and endoscopic ultrasound. Almost all gastrinomas contain somatostatin receptors on the gastrin cells and somatostatin scintigraphy using [111In-DPTA-Dphe1]-octreotide is considered the initial localization study of choice. It has 71% sensitivity and 86% specificity for primary tumors and 92% sensitivity for detection of metastatic disease.

References

1. Murugesan S.V., Varro A., Pritchard D.M. Review article: Strategies to determine whether hypergastrinaemia is due to Zollinger-Ellison syndrome rather than a more common benign cause. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;29:1055-68.

2. Jensen R.T., Niederle B., Mitry E., et al. Frascati Consensus Conference; European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Gastrinoma (duodenal and pancreatic). Neuroendocrinology 2006;84:173-82.

3. Hung, P.D., Schubert, M.L., Mihas, A.A. Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology 2003;6:163-70.

4. Gibril F., Reynolds J.C., Doppman J.L., et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: Its sensitivity compared with that of other imaging methods in detecting primary and metastatic gastrinomas - A prospective study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;125:26-34.

5. Hung, P.D., Schubert, M.L., Mihas, A.A. Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology 2003;6:163-70.

- Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut 2005;54:449–54.

- Smith J, Woodcock A, Houghton L. New developments in reflux-associated cough. Lung 2010;188(Suppl1)S81-6.

- Sifrim D, Barnes N. GERD related chronic cough: How to identify patients who will respond to antireflux therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;44:234-6.

- Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut 2005;54:449–54.

- Smith J, Woodcock A, Houghton L. New developments in reflux-associated cough. Lung 2010;188(Suppl1)S81-6.

- Sifrim D, Barnes N. GERD related chronic cough: How to identify patients who will respond to antireflux therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;44:234-6.

Factor XI inhibitor trims DVTs after knee replacement surgery

SAN FRANCISCO – Reducing factor XI levels with the experimental antisense oligonucleotide FXI-ASO lowered venous thromboembolism rates after total knee arthroplasty without increasing bleeding in a phase II study.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) rates were 30% among controls (21/69) on enoxaparin (Lovenox) 40 mg, compared with 27% for patients (36/134) given FXI-ASO 200 mg and 4% for those (3/71) given FXI-ASO 300 mg. Low-dose FXI-ASO was noninferior to enoxaparin (P = .59), while the high-dose regimen was superior (P < .001).

A 4% VTE rate “has never ever been seen before in patients undergoing knee surgery,” Dr. Harry Büller said during the late-breaking abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The strategy of targeting factor XI is based on the understanding that patients with factor XI deficiency (plasma levels < 20% of normal) have a reduced risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Experimental data in mice and primates also suggest that reducing factor XI attenuates thrombosis without excess bleeding.

Among the 300 patients in the open-label study, major or clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 3% of both FXI-ASO groups and 8% of the enoxaparin group (P = .09).

The findings provide the first evidence in humans that the factor XI intrinsic pathway is one of the drivers of postoperative thrombosis and support the concept that thrombosis and hemostasis can be dissociated, said Dr. Büller of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam.

“FXI-ASO is a promising new investigational antithrombotic agent and I believe you are witnessing the birth of a new class of antithrombotic agents,” he concluded.

During a press conference, Dr. Büller confided to reporters that he felt like a boy in a candy store, finally able to reveal the superb study findings.

Dr. Robert Flaumenhaft of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was far less effusive in an editorial that accompanied the simultaneous publication of the study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Do these finding prove that reduction in factor XI levels inhibits thrombosis without affecting bleeding? The conservative answer is no,” he wrote.

Dr. Flaumenhaft observed that the incidence of clinically relevant bleeding is relatively low after knee arthroplasty, even when patients receive anticoagulants, and that this safety outcome did not differ significantly between the enoxaparin and 300-mg FXI-ASO groups.

“These results also do not make a compelling case for the clinical use of the factor XI antisense oligonucleotide over anticoagulants that are currently used for prophylaxis in patients undergoing knee arthroplasty,” he wrote.

Central to this argument are issues of convenience and questions regarding reversibility. Treatment began 36 days before surgery and was associated with a high incidence of adverse events at the injection site and factor XI levels remained about 60% lower 70 days after initiation of therapy.

The half-life of FXI-ASO is about 22 days, “which in the classical setting in terms of bleeding could be seen as something of a disadvantage,” Dr. Büller told reporters. “But if we do the next study and it shows to be safe, it turns into an advantage” … because there is the possibility of giving FXI-ASO once every 3 weeks.

Dr. Flaumenhaft closed the editorial by acknowledging that the study challenges “the current paradigm” regarding the primary mechanism responsible for fibrin formation during thrombosis. “The striking observation that reducing factor XI levels prevents thrombosis after knee arthroplasty provides the best clinical evidence to date that the intrinsic pathway is essential for thrombus formation,” he wrote.

The study was conducted at 19 centers in five countries and randomly assigned 300 patients scheduled for elective primary unilateral total-knee arthroplasty to daily enoxaparin 40 mg or three doses of FXI-ASO. The protocol was amended early on to exclude a 100-mg FXI-ASO dose.

FXI-ASO 200 mg or 300 mg was given subcutaneously beginning 36 days before surgery on days 1, 3, 5, 8, 15, 22, and 29, and 6 hours postoperatively, with a final dose on day 39.

Enoxaparin 40 mg was given subcutaneously once daily, beginning the evening before or 6-8 hours after surgery, according to investigator preference, and was continued for at least 8 days postoperatively.

The primary efficacy point was a composite of asymptomatic DVT, detected by venography, and confirmed symptomatic VTE.

At baseline, the average factor XI level was 1.23 units/mL in the enoxaparin group, 1.20 U/mL in the 200-mg group, and 1.16 U/mL in the 300-mg group.

In patients with an average factor XI level of 0.2 U/mL or less, the incidence of the primary efficacy outcome was 5%.

Isis Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Büller disclosed ties with Isis, Daiichi-Sankyo, Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Flaumenhaft reported having no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Reducing factor XI levels with the experimental antisense oligonucleotide FXI-ASO lowered venous thromboembolism rates after total knee arthroplasty without increasing bleeding in a phase II study.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) rates were 30% among controls (21/69) on enoxaparin (Lovenox) 40 mg, compared with 27% for patients (36/134) given FXI-ASO 200 mg and 4% for those (3/71) given FXI-ASO 300 mg. Low-dose FXI-ASO was noninferior to enoxaparin (P = .59), while the high-dose regimen was superior (P < .001).

A 4% VTE rate “has never ever been seen before in patients undergoing knee surgery,” Dr. Harry Büller said during the late-breaking abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The strategy of targeting factor XI is based on the understanding that patients with factor XI deficiency (plasma levels < 20% of normal) have a reduced risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Experimental data in mice and primates also suggest that reducing factor XI attenuates thrombosis without excess bleeding.

Among the 300 patients in the open-label study, major or clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 3% of both FXI-ASO groups and 8% of the enoxaparin group (P = .09).

The findings provide the first evidence in humans that the factor XI intrinsic pathway is one of the drivers of postoperative thrombosis and support the concept that thrombosis and hemostasis can be dissociated, said Dr. Büller of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam.

“FXI-ASO is a promising new investigational antithrombotic agent and I believe you are witnessing the birth of a new class of antithrombotic agents,” he concluded.

During a press conference, Dr. Büller confided to reporters that he felt like a boy in a candy store, finally able to reveal the superb study findings.

Dr. Robert Flaumenhaft of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was far less effusive in an editorial that accompanied the simultaneous publication of the study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Do these finding prove that reduction in factor XI levels inhibits thrombosis without affecting bleeding? The conservative answer is no,” he wrote.

Dr. Flaumenhaft observed that the incidence of clinically relevant bleeding is relatively low after knee arthroplasty, even when patients receive anticoagulants, and that this safety outcome did not differ significantly between the enoxaparin and 300-mg FXI-ASO groups.

“These results also do not make a compelling case for the clinical use of the factor XI antisense oligonucleotide over anticoagulants that are currently used for prophylaxis in patients undergoing knee arthroplasty,” he wrote.

Central to this argument are issues of convenience and questions regarding reversibility. Treatment began 36 days before surgery and was associated with a high incidence of adverse events at the injection site and factor XI levels remained about 60% lower 70 days after initiation of therapy.

The half-life of FXI-ASO is about 22 days, “which in the classical setting in terms of bleeding could be seen as something of a disadvantage,” Dr. Büller told reporters. “But if we do the next study and it shows to be safe, it turns into an advantage” … because there is the possibility of giving FXI-ASO once every 3 weeks.

Dr. Flaumenhaft closed the editorial by acknowledging that the study challenges “the current paradigm” regarding the primary mechanism responsible for fibrin formation during thrombosis. “The striking observation that reducing factor XI levels prevents thrombosis after knee arthroplasty provides the best clinical evidence to date that the intrinsic pathway is essential for thrombus formation,” he wrote.

The study was conducted at 19 centers in five countries and randomly assigned 300 patients scheduled for elective primary unilateral total-knee arthroplasty to daily enoxaparin 40 mg or three doses of FXI-ASO. The protocol was amended early on to exclude a 100-mg FXI-ASO dose.

FXI-ASO 200 mg or 300 mg was given subcutaneously beginning 36 days before surgery on days 1, 3, 5, 8, 15, 22, and 29, and 6 hours postoperatively, with a final dose on day 39.

Enoxaparin 40 mg was given subcutaneously once daily, beginning the evening before or 6-8 hours after surgery, according to investigator preference, and was continued for at least 8 days postoperatively.

The primary efficacy point was a composite of asymptomatic DVT, detected by venography, and confirmed symptomatic VTE.

At baseline, the average factor XI level was 1.23 units/mL in the enoxaparin group, 1.20 U/mL in the 200-mg group, and 1.16 U/mL in the 300-mg group.

In patients with an average factor XI level of 0.2 U/mL or less, the incidence of the primary efficacy outcome was 5%.

Isis Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Büller disclosed ties with Isis, Daiichi-Sankyo, Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Flaumenhaft reported having no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Reducing factor XI levels with the experimental antisense oligonucleotide FXI-ASO lowered venous thromboembolism rates after total knee arthroplasty without increasing bleeding in a phase II study.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) rates were 30% among controls (21/69) on enoxaparin (Lovenox) 40 mg, compared with 27% for patients (36/134) given FXI-ASO 200 mg and 4% for those (3/71) given FXI-ASO 300 mg. Low-dose FXI-ASO was noninferior to enoxaparin (P = .59), while the high-dose regimen was superior (P < .001).

A 4% VTE rate “has never ever been seen before in patients undergoing knee surgery,” Dr. Harry Büller said during the late-breaking abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The strategy of targeting factor XI is based on the understanding that patients with factor XI deficiency (plasma levels < 20% of normal) have a reduced risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Experimental data in mice and primates also suggest that reducing factor XI attenuates thrombosis without excess bleeding.

Among the 300 patients in the open-label study, major or clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 3% of both FXI-ASO groups and 8% of the enoxaparin group (P = .09).

The findings provide the first evidence in humans that the factor XI intrinsic pathway is one of the drivers of postoperative thrombosis and support the concept that thrombosis and hemostasis can be dissociated, said Dr. Büller of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam.

“FXI-ASO is a promising new investigational antithrombotic agent and I believe you are witnessing the birth of a new class of antithrombotic agents,” he concluded.

During a press conference, Dr. Büller confided to reporters that he felt like a boy in a candy store, finally able to reveal the superb study findings.

Dr. Robert Flaumenhaft of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was far less effusive in an editorial that accompanied the simultaneous publication of the study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Do these finding prove that reduction in factor XI levels inhibits thrombosis without affecting bleeding? The conservative answer is no,” he wrote.

Dr. Flaumenhaft observed that the incidence of clinically relevant bleeding is relatively low after knee arthroplasty, even when patients receive anticoagulants, and that this safety outcome did not differ significantly between the enoxaparin and 300-mg FXI-ASO groups.

“These results also do not make a compelling case for the clinical use of the factor XI antisense oligonucleotide over anticoagulants that are currently used for prophylaxis in patients undergoing knee arthroplasty,” he wrote.

Central to this argument are issues of convenience and questions regarding reversibility. Treatment began 36 days before surgery and was associated with a high incidence of adverse events at the injection site and factor XI levels remained about 60% lower 70 days after initiation of therapy.

The half-life of FXI-ASO is about 22 days, “which in the classical setting in terms of bleeding could be seen as something of a disadvantage,” Dr. Büller told reporters. “But if we do the next study and it shows to be safe, it turns into an advantage” … because there is the possibility of giving FXI-ASO once every 3 weeks.

Dr. Flaumenhaft closed the editorial by acknowledging that the study challenges “the current paradigm” regarding the primary mechanism responsible for fibrin formation during thrombosis. “The striking observation that reducing factor XI levels prevents thrombosis after knee arthroplasty provides the best clinical evidence to date that the intrinsic pathway is essential for thrombus formation,” he wrote.

The study was conducted at 19 centers in five countries and randomly assigned 300 patients scheduled for elective primary unilateral total-knee arthroplasty to daily enoxaparin 40 mg or three doses of FXI-ASO. The protocol was amended early on to exclude a 100-mg FXI-ASO dose.

FXI-ASO 200 mg or 300 mg was given subcutaneously beginning 36 days before surgery on days 1, 3, 5, 8, 15, 22, and 29, and 6 hours postoperatively, with a final dose on day 39.

Enoxaparin 40 mg was given subcutaneously once daily, beginning the evening before or 6-8 hours after surgery, according to investigator preference, and was continued for at least 8 days postoperatively.

The primary efficacy point was a composite of asymptomatic DVT, detected by venography, and confirmed symptomatic VTE.

At baseline, the average factor XI level was 1.23 units/mL in the enoxaparin group, 1.20 U/mL in the 200-mg group, and 1.16 U/mL in the 300-mg group.

In patients with an average factor XI level of 0.2 U/mL or less, the incidence of the primary efficacy outcome was 5%.

Isis Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Büller disclosed ties with Isis, Daiichi-Sankyo, Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Flaumenhaft reported having no disclosures.

AT ASH 2014

Key clinical point: Reducing factor XI levels with FXI-ASO was effective in preventing VTE in patients undergoing knee arthroplasty and appeared safe with respect to bleeding risk.

Major finding: The primary VTE endpoint occurred in 4% of patients on FXI-ASO 300 mg, 27% on FXI-ASO 200 mg, and 30% on enoxaparin.

Data source: Open-label, parallel-group phase II study of 300 patients undergoing primary unilateral total-knee arthroplasty.

Disclosures: Isis Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Büller disclosed ties with Isis, Daiichi-Sankyo, Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Flaumenhaft reported having no disclosures.

Postexposure smallpox vaccination not recommended for immunodeficient patients

Persons exposed to smallpox should be vaccinated with a replication-competent vaccine, unless they are severely immunodeficient, according to a guideline from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Severely immunodeficient persons won’t benefit from a smallpox vaccination because there will likely be a poor immune response and heightened risk of negative events. These include bone marrow transplant recipients within 4 months of transplantation, people infected with HIV with CD4 cell counts <50 cells/mm3, persons with severe combined immunodeficiency, complete DiGeorge syndrome patients, and people with other severely immunocompromised states requiring isolation.

“If antivirals are not immediately available, it is reasonable to consider the use of Imvamune in the setting of a smallpox virus exposure in persons with severe immunodeficiency,” the CDC added.

Find the full guideline in the MMWR (February 20, 2015 / 64(RR02);1-26).

Persons exposed to smallpox should be vaccinated with a replication-competent vaccine, unless they are severely immunodeficient, according to a guideline from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Severely immunodeficient persons won’t benefit from a smallpox vaccination because there will likely be a poor immune response and heightened risk of negative events. These include bone marrow transplant recipients within 4 months of transplantation, people infected with HIV with CD4 cell counts <50 cells/mm3, persons with severe combined immunodeficiency, complete DiGeorge syndrome patients, and people with other severely immunocompromised states requiring isolation.

“If antivirals are not immediately available, it is reasonable to consider the use of Imvamune in the setting of a smallpox virus exposure in persons with severe immunodeficiency,” the CDC added.

Find the full guideline in the MMWR (February 20, 2015 / 64(RR02);1-26).

Persons exposed to smallpox should be vaccinated with a replication-competent vaccine, unless they are severely immunodeficient, according to a guideline from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Severely immunodeficient persons won’t benefit from a smallpox vaccination because there will likely be a poor immune response and heightened risk of negative events. These include bone marrow transplant recipients within 4 months of transplantation, people infected with HIV with CD4 cell counts <50 cells/mm3, persons with severe combined immunodeficiency, complete DiGeorge syndrome patients, and people with other severely immunocompromised states requiring isolation.

“If antivirals are not immediately available, it is reasonable to consider the use of Imvamune in the setting of a smallpox virus exposure in persons with severe immunodeficiency,” the CDC added.

Find the full guideline in the MMWR (February 20, 2015 / 64(RR02);1-26).

Bleeding complications following femoral angiographic access

Bleeding complications following angiographic interventions have recently become an increasing cause of medical malpractice litigation. The reason for this increase is likely a result of several factors including the controversy surrounding the multiple approaches that are currently employed for the treatment of this type of bleeding, as well as the significant morbidity and mortality associated with these treatment paradigms. Allegations in these lawsuits usually include failure to diagnose, failure to treat, failure to transfuse, negligence in the use of an endovascular approach, and negligence in open surgical treatment. Physical examination, close observation, and an aggressive approach to intervention are necessary if litigation is to be avoided in this patient population.

Case 1

The patient underwent cardiac catheterization with placement of a coronary stent. The patient was placed on Integrilin. Following the catheterization, the patient had multiple episodes of hypotension. Each episode responded to fluid boluses and transfusion. No surgical consultation was obtained. The patient’s hemoglobin never fell below 8 grams. The patient was transfused approximately 8 units of blood. The patient’s Integrilin was discontinued. However, the patient progressed to multisystem organ failure and died. Autopsy revealed a massive hematoma of the retroperitoneum and a patent coronary stent. A medical malpractice suit was filed. The case was settled.

Case 2

A patient underwent cardiac catheterization and subsequently developed severe bleeding. She received approximately 10 units of blood prior to vascular surgical consultation. By the time the vascular surgeon saw the patient, the patient was intubated and on vasopressors. The vascular surgeon stated that the patient was not a candidate for surgery. The patient subsequently died. A lawsuit was filed against both the cardiologist and the vascular surgeon. This case was settled by both physicians.

Case 3

A cardiologist calls a vascular surgeon who is at home at 10 p.m. to let her know that he has a patient with a retroperitoneal hematoma following a cardiac cath. He informs the surgeon that the patient is stable. He “just wants her to be aware in case the patient’s condition deteriorates.”

During the night the patient has repeated hypotensive episodes which the cardiologist manages with transfusions. At 5 a.m. the patient arrests and is resuscitated. The surgeon is called, and she takes the patient to surgery but the patient succumbs. The surgeon is sued for not coming in to see the patient and being more involved during the night.

The jury finds in favor of the surgeon. However, the trial took 2 weeks during which time the surgeon had to attend the deliberations and so she was unable work.

Discussion

Unfortunately, the above examples represent the all too often complication of postprocedure bleeding following femoral access.

In case 1, early exploration would more likely than not, and within a reasonable degree of medical certainty, prevented the patient’s death. The presumption is that the patient died from the untreated complication of postcatheterization hemorrhage. The defendant’s claim that the patient’s hemoglobin was never lower than 8 mg did not serve as an adequate defense. Even if the patient was found at autopsy to have an occluded stent which caused an acute MI, the plaintiff’s attorney would likely argue successfully that if the bleeding had been appropriately treated, the stent would have remained patent. The cardiologist was found culpable for not consulting a vascular surgeon.

In the second example, the plaintiff’s expert explained to the jury that without surgery, the patient would continue to bleed and certainly die. He went on to opine that the only possible chance of the patient surviving was with surgical intervention, and this chance was denied to the patient by the vascular surgeon who refused to operate. In these types of cases, the surgeon incorrectly believes that he/she can avoid liability and involvement in the case by not operating on the patient. However, as this case demonstrated, the surgeon is still likely to be named as a defendant in the law suit.