User login

Your patient refuses a suicide risk assessment. Now what?

On occasion, a patient may refuse to cooperate with a suicide risk assessment or is unable to participate due to the severity of a psychiatric or medical condition. In such situations, how can we conduct an assessment that meets our ethical, professional, and legal obligations?

First, skipping a suicide risk assessment is never an option. A patient’s refusal or inability to cooperate does not release us from our duty of care. We are obligated to gather information about suicide risk to anticipate the likelihood and severity of harm.1 Furthermore, collecting information helps us evaluate what types of precautions are necessary to reduce or eliminate suicide risk.

Some clinicians may believe that a suicide risk assessment is only possible when they can ask patients about ideation, intent, plans, and past suicidal behavior. While the patient’s self-report is valuable, it is only one data point, and in some cases, it may not be reliable or credible.2 So how should you handle such situations? Here I describe 3 steps to take to estimate a patient’s suicide risk without their participation.

1. Obtain information from other sources.

These can include:

- your recent contacts with the patient

- the patient’s responses to previous inquiries about suicidality

- collateral reports from staff

- the patient’s chart and past medical records

- past suicide attempts (including the precipitants, the patient’s reasons for the attempt, details of the actions taken and methods used, any medical outcome, and the patient’s reaction to surviving)3

- past nonsuicidal self-injury

- past episodes of suicidal thinking

- treatment progress to date

- mental status.

Documenting your sources of information will indicate that you made reasonable efforts to appreciate the risk despite imperfect circumstances. Furthermore, these sources of data can support your work to assess the severity of the patient’s current suicidality, to clinically formulate why the patient is susceptible to suicidal thoughts and behavior, and to anticipate circumstances that could constitute a high-risk period for your patient to attempt suicide.

2. Document the reasons you were unable to interview the patient. For patients who are competent to refuse services, document the efforts you made to gain the patient’s cooperation. If the patient’s psychiatric condition (eg, florid psychosis) was the main impediment, note this.

3. Explain the limitations of your assessment. This might include acknowledging that your estimation of the patient’s suicide risk is missing important information but is the best possible estimate at the time. Explain how you determined the level of risk with a statement such as, “Because the patient was unable to participate, I estimated risk based on….” If the patient’s lack of participation lowers your confidence in your risk estimate, this also should be documented. Reduced confidence may indicate the need for additional steps to assure the patient’s safety (eg, admission, delaying discharge, initiating continuous observation).

1. Obegi JH. Probable standards of care for suicide risk assessment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(4):452-459.

2. Hom MA, Stanley IH, Duffy ME, et al. Investigating the reliability of suicide attempt history reporting across five measures: a study of US military service members at risk of suicide. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(7):1332-1349.

3. Rudd MD. Core competencies, warning signs, and a framework for suicide risk assessment in clinical practice. In: Nock MK, ed. The Oxford handbook of suicide and self-injury. Oxford University Press; 2014:323-336.

On occasion, a patient may refuse to cooperate with a suicide risk assessment or is unable to participate due to the severity of a psychiatric or medical condition. In such situations, how can we conduct an assessment that meets our ethical, professional, and legal obligations?

First, skipping a suicide risk assessment is never an option. A patient’s refusal or inability to cooperate does not release us from our duty of care. We are obligated to gather information about suicide risk to anticipate the likelihood and severity of harm.1 Furthermore, collecting information helps us evaluate what types of precautions are necessary to reduce or eliminate suicide risk.

Some clinicians may believe that a suicide risk assessment is only possible when they can ask patients about ideation, intent, plans, and past suicidal behavior. While the patient’s self-report is valuable, it is only one data point, and in some cases, it may not be reliable or credible.2 So how should you handle such situations? Here I describe 3 steps to take to estimate a patient’s suicide risk without their participation.

1. Obtain information from other sources.

These can include:

- your recent contacts with the patient

- the patient’s responses to previous inquiries about suicidality

- collateral reports from staff

- the patient’s chart and past medical records

- past suicide attempts (including the precipitants, the patient’s reasons for the attempt, details of the actions taken and methods used, any medical outcome, and the patient’s reaction to surviving)3

- past nonsuicidal self-injury

- past episodes of suicidal thinking

- treatment progress to date

- mental status.

Documenting your sources of information will indicate that you made reasonable efforts to appreciate the risk despite imperfect circumstances. Furthermore, these sources of data can support your work to assess the severity of the patient’s current suicidality, to clinically formulate why the patient is susceptible to suicidal thoughts and behavior, and to anticipate circumstances that could constitute a high-risk period for your patient to attempt suicide.

2. Document the reasons you were unable to interview the patient. For patients who are competent to refuse services, document the efforts you made to gain the patient’s cooperation. If the patient’s psychiatric condition (eg, florid psychosis) was the main impediment, note this.

3. Explain the limitations of your assessment. This might include acknowledging that your estimation of the patient’s suicide risk is missing important information but is the best possible estimate at the time. Explain how you determined the level of risk with a statement such as, “Because the patient was unable to participate, I estimated risk based on….” If the patient’s lack of participation lowers your confidence in your risk estimate, this also should be documented. Reduced confidence may indicate the need for additional steps to assure the patient’s safety (eg, admission, delaying discharge, initiating continuous observation).

On occasion, a patient may refuse to cooperate with a suicide risk assessment or is unable to participate due to the severity of a psychiatric or medical condition. In such situations, how can we conduct an assessment that meets our ethical, professional, and legal obligations?

First, skipping a suicide risk assessment is never an option. A patient’s refusal or inability to cooperate does not release us from our duty of care. We are obligated to gather information about suicide risk to anticipate the likelihood and severity of harm.1 Furthermore, collecting information helps us evaluate what types of precautions are necessary to reduce or eliminate suicide risk.

Some clinicians may believe that a suicide risk assessment is only possible when they can ask patients about ideation, intent, plans, and past suicidal behavior. While the patient’s self-report is valuable, it is only one data point, and in some cases, it may not be reliable or credible.2 So how should you handle such situations? Here I describe 3 steps to take to estimate a patient’s suicide risk without their participation.

1. Obtain information from other sources.

These can include:

- your recent contacts with the patient

- the patient’s responses to previous inquiries about suicidality

- collateral reports from staff

- the patient’s chart and past medical records

- past suicide attempts (including the precipitants, the patient’s reasons for the attempt, details of the actions taken and methods used, any medical outcome, and the patient’s reaction to surviving)3

- past nonsuicidal self-injury

- past episodes of suicidal thinking

- treatment progress to date

- mental status.

Documenting your sources of information will indicate that you made reasonable efforts to appreciate the risk despite imperfect circumstances. Furthermore, these sources of data can support your work to assess the severity of the patient’s current suicidality, to clinically formulate why the patient is susceptible to suicidal thoughts and behavior, and to anticipate circumstances that could constitute a high-risk period for your patient to attempt suicide.

2. Document the reasons you were unable to interview the patient. For patients who are competent to refuse services, document the efforts you made to gain the patient’s cooperation. If the patient’s psychiatric condition (eg, florid psychosis) was the main impediment, note this.

3. Explain the limitations of your assessment. This might include acknowledging that your estimation of the patient’s suicide risk is missing important information but is the best possible estimate at the time. Explain how you determined the level of risk with a statement such as, “Because the patient was unable to participate, I estimated risk based on….” If the patient’s lack of participation lowers your confidence in your risk estimate, this also should be documented. Reduced confidence may indicate the need for additional steps to assure the patient’s safety (eg, admission, delaying discharge, initiating continuous observation).

1. Obegi JH. Probable standards of care for suicide risk assessment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(4):452-459.

2. Hom MA, Stanley IH, Duffy ME, et al. Investigating the reliability of suicide attempt history reporting across five measures: a study of US military service members at risk of suicide. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(7):1332-1349.

3. Rudd MD. Core competencies, warning signs, and a framework for suicide risk assessment in clinical practice. In: Nock MK, ed. The Oxford handbook of suicide and self-injury. Oxford University Press; 2014:323-336.

1. Obegi JH. Probable standards of care for suicide risk assessment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(4):452-459.

2. Hom MA, Stanley IH, Duffy ME, et al. Investigating the reliability of suicide attempt history reporting across five measures: a study of US military service members at risk of suicide. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(7):1332-1349.

3. Rudd MD. Core competencies, warning signs, and a framework for suicide risk assessment in clinical practice. In: Nock MK, ed. The Oxford handbook of suicide and self-injury. Oxford University Press; 2014:323-336.

How to write a suicide risk assessment that’s clinically sound and legally defensible

Suicidologists and legal experts implore clinicians to document their suicide risk assessments (SRAs) thoroughly. It’s difficult, however, to find practical guidance on how to write a clinically sound, legally defensible SRA.

The crux of every SRA is written justification of suicide risk. That justification should reveal your thinking and present a well-reasoned basis for your decision.

Reasoned vs right

It’s more important to provide a justification of suicide risk that’s well-reasoned rather than one that’s right. Suicide is impossible to predict. Instead of prediction, legally we are asked to reasonably anticipate suicide based on clinical facts. In hindsight, especially in the context of a courtroom, decisions might look ill-considered. You need to craft a logical argument, be clear, and avoid jargon.

Convey thoroughness by covering each component of an SRA. Use the mnemonic device CAIPS to help the reader (and you) understand how a conclusion was reached based on the facts of the case.

Chronic and Acute factors. Address the chronic and acute factors that weigh heaviest in your mind. Chronic factors are conditions, past events, and demographics that generally do not change. Acute factors are recent events or conditions that potentially are modifiable. Pay attention to combinations of factors that dramatically elevate risk (eg, previous attempts in the context of acute depression). Avoid repeating every factor, especially when these are documented elsewhere, such as on a checklist.

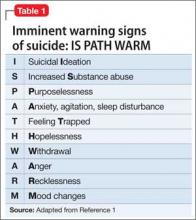

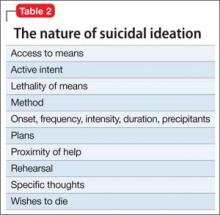

Imminent warning signs for suicide. Address warning signs (Table 1),1 the nature of current suicidal thoughts (Table 2), and other aspects of mental status (eg, future orientation) that influenced your decision. Use words like “moreover,” “however,” and “in addition” to draw the reader’s attention to the building blocks of your argument.

Protective factors. Discuss the protective factors last; they deserve the least weight because none has been shown to immunize people against suicide. Don’t solely rely on your judgment of what is protective (eg, children in the home). Instead, elicit the patient’s reasons for living and dying. Be concerned if he (she) reports more of the latter.

Summary statement. Make an explicit statement about risk, focusing on imminent risk (ie, the next few hours and days). Avoid a “plot twist,” which is a risk level inconsistent with the preceding evidence, because it suggests an error in judgment. The Box gives an example of a justification that follows the CAIPS method.

Additional tips

Consider these strategies:

• Bolster your argument by explicitly addressing hopelessness (the strongest psychological correlate of suicide); use quotes from the patient that support your decision; refer to consultation with family members and colleagues; and include pertinent negatives to show completeness2 (ie, “denied suicide plans”).

• Critically resolve discrepancies between what the patient says and behavior that suggests suicidal intent (eg, a patient who minimizes suicidal intent but shopped for a gun yesterday).

• Last, while reviewing your justification, imagine that your patient completed suicide after leaving your office and that you are in court for negligence. In our experience, this exercise reveals dangerous errors of judgment. A clear and reasoned justification will reduce the risk of litigation and help you make prudent treatment plans.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Association of Suicidology. Know the warning signs of suicide. http://www.suicidology.org/resources/ warning-signs. Accessed February 9, 2014.

2. Ballas C. How to write a suicide note: practical tips for documenting the evaluation of a suicidal patient. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/how-write-suicide-note-practical-tips-documenting-evaluation-suicidal-patient. Published May 1, 2007. Accessed July 29, 2013.

Suicidologists and legal experts implore clinicians to document their suicide risk assessments (SRAs) thoroughly. It’s difficult, however, to find practical guidance on how to write a clinically sound, legally defensible SRA.

The crux of every SRA is written justification of suicide risk. That justification should reveal your thinking and present a well-reasoned basis for your decision.

Reasoned vs right

It’s more important to provide a justification of suicide risk that’s well-reasoned rather than one that’s right. Suicide is impossible to predict. Instead of prediction, legally we are asked to reasonably anticipate suicide based on clinical facts. In hindsight, especially in the context of a courtroom, decisions might look ill-considered. You need to craft a logical argument, be clear, and avoid jargon.

Convey thoroughness by covering each component of an SRA. Use the mnemonic device CAIPS to help the reader (and you) understand how a conclusion was reached based on the facts of the case.

Chronic and Acute factors. Address the chronic and acute factors that weigh heaviest in your mind. Chronic factors are conditions, past events, and demographics that generally do not change. Acute factors are recent events or conditions that potentially are modifiable. Pay attention to combinations of factors that dramatically elevate risk (eg, previous attempts in the context of acute depression). Avoid repeating every factor, especially when these are documented elsewhere, such as on a checklist.

Imminent warning signs for suicide. Address warning signs (Table 1),1 the nature of current suicidal thoughts (Table 2), and other aspects of mental status (eg, future orientation) that influenced your decision. Use words like “moreover,” “however,” and “in addition” to draw the reader’s attention to the building blocks of your argument.

Protective factors. Discuss the protective factors last; they deserve the least weight because none has been shown to immunize people against suicide. Don’t solely rely on your judgment of what is protective (eg, children in the home). Instead, elicit the patient’s reasons for living and dying. Be concerned if he (she) reports more of the latter.

Summary statement. Make an explicit statement about risk, focusing on imminent risk (ie, the next few hours and days). Avoid a “plot twist,” which is a risk level inconsistent with the preceding evidence, because it suggests an error in judgment. The Box gives an example of a justification that follows the CAIPS method.

Additional tips

Consider these strategies:

• Bolster your argument by explicitly addressing hopelessness (the strongest psychological correlate of suicide); use quotes from the patient that support your decision; refer to consultation with family members and colleagues; and include pertinent negatives to show completeness2 (ie, “denied suicide plans”).

• Critically resolve discrepancies between what the patient says and behavior that suggests suicidal intent (eg, a patient who minimizes suicidal intent but shopped for a gun yesterday).

• Last, while reviewing your justification, imagine that your patient completed suicide after leaving your office and that you are in court for negligence. In our experience, this exercise reveals dangerous errors of judgment. A clear and reasoned justification will reduce the risk of litigation and help you make prudent treatment plans.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Suicidologists and legal experts implore clinicians to document their suicide risk assessments (SRAs) thoroughly. It’s difficult, however, to find practical guidance on how to write a clinically sound, legally defensible SRA.

The crux of every SRA is written justification of suicide risk. That justification should reveal your thinking and present a well-reasoned basis for your decision.

Reasoned vs right

It’s more important to provide a justification of suicide risk that’s well-reasoned rather than one that’s right. Suicide is impossible to predict. Instead of prediction, legally we are asked to reasonably anticipate suicide based on clinical facts. In hindsight, especially in the context of a courtroom, decisions might look ill-considered. You need to craft a logical argument, be clear, and avoid jargon.

Convey thoroughness by covering each component of an SRA. Use the mnemonic device CAIPS to help the reader (and you) understand how a conclusion was reached based on the facts of the case.

Chronic and Acute factors. Address the chronic and acute factors that weigh heaviest in your mind. Chronic factors are conditions, past events, and demographics that generally do not change. Acute factors are recent events or conditions that potentially are modifiable. Pay attention to combinations of factors that dramatically elevate risk (eg, previous attempts in the context of acute depression). Avoid repeating every factor, especially when these are documented elsewhere, such as on a checklist.

Imminent warning signs for suicide. Address warning signs (Table 1),1 the nature of current suicidal thoughts (Table 2), and other aspects of mental status (eg, future orientation) that influenced your decision. Use words like “moreover,” “however,” and “in addition” to draw the reader’s attention to the building blocks of your argument.

Protective factors. Discuss the protective factors last; they deserve the least weight because none has been shown to immunize people against suicide. Don’t solely rely on your judgment of what is protective (eg, children in the home). Instead, elicit the patient’s reasons for living and dying. Be concerned if he (she) reports more of the latter.

Summary statement. Make an explicit statement about risk, focusing on imminent risk (ie, the next few hours and days). Avoid a “plot twist,” which is a risk level inconsistent with the preceding evidence, because it suggests an error in judgment. The Box gives an example of a justification that follows the CAIPS method.

Additional tips

Consider these strategies:

• Bolster your argument by explicitly addressing hopelessness (the strongest psychological correlate of suicide); use quotes from the patient that support your decision; refer to consultation with family members and colleagues; and include pertinent negatives to show completeness2 (ie, “denied suicide plans”).

• Critically resolve discrepancies between what the patient says and behavior that suggests suicidal intent (eg, a patient who minimizes suicidal intent but shopped for a gun yesterday).

• Last, while reviewing your justification, imagine that your patient completed suicide after leaving your office and that you are in court for negligence. In our experience, this exercise reveals dangerous errors of judgment. A clear and reasoned justification will reduce the risk of litigation and help you make prudent treatment plans.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Association of Suicidology. Know the warning signs of suicide. http://www.suicidology.org/resources/ warning-signs. Accessed February 9, 2014.

2. Ballas C. How to write a suicide note: practical tips for documenting the evaluation of a suicidal patient. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/how-write-suicide-note-practical-tips-documenting-evaluation-suicidal-patient. Published May 1, 2007. Accessed July 29, 2013.

1. American Association of Suicidology. Know the warning signs of suicide. http://www.suicidology.org/resources/ warning-signs. Accessed February 9, 2014.

2. Ballas C. How to write a suicide note: practical tips for documenting the evaluation of a suicidal patient. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/how-write-suicide-note-practical-tips-documenting-evaluation-suicidal-patient. Published May 1, 2007. Accessed July 29, 2013.