User login

FDA guidance focuses on infections with reusable devices, including duodenoscopes

Recommendations to manufacturers about improving the safety of reusable medical devices and an upcoming advisory committee meeting on duodenoscope-associated infections are two efforts recently announced by the Food and Drug Administration that address the risks associated with reusable devices.

A final guidance document for industry on reprocessing reusable medical devices includes recommendations “aimed at helping device manufacturers develop safer reusable devices, especially those devices that pose a greater risk of infection,” according to the March 12 announcement. Also included in the guidance are criteria that should be met in instructions for reprocessing reusable devices, “to ensure users understand and correctly follow the reprocessing instructions,” and recommendations that manufacturers should consider “reprocessing challenges” at the early stages of the design of such devices.

The same announcement said that in mid-May, the FDA was convening a 2-day meeting of the agency’s Gastroenterology and Urology Devices Panel to discuss the recent reports of infections associated with the use of duodenoscopes in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures in U.S. hospitals.

The announcement was issued less than a month after the agency alerted health care professionals and the public about the association with duodenoscopes and the transmission of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in patients who had undergone ERCP procedures, despite proper cleaning and disinfection of the devices. Between January 2013 and December 2014, the agency received 75 medical device adverse event reports for about 135 patients in the United States “relating to possible microbial transmission from reprocessed duodenoscopes,” according to the safety communication issued by the FDA on Feb. 19.

These reports and cases described in the medical literature have occurred even when manufacturer instructions for cleaning and sterilization were followed.

“Although the complex design of duodenoscopes improves the efficiency and effectiveness of ERCP, it causes challenges for cleaning and high-level disinfection,” according to the statement, which pointed out that it can be difficult to access some parts of the duodenoscopes when they are cleaned. Problems include the “elevator” mechanism at the tip of the duodenoscope, which should be manually brushed, but a brush may not be able to reach microscopic crevices in this mechanism and “residual body fluids and organic debris may remain in these crevices after cleaning and disinfection,” possibly exposing patients to serious infections if the fluids are contaminated with microbes.

The infections reported include carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), according to the first FDA statement, which did not mention whether any of the reports were fatal.

But on Feb. 18, the UCLA Health System announced that CRE may have been transmitted to seven patients during ERCP procedures, and may have contributed to the death of two of the patients. The two devices implicated in these cases are no longer used and the medical center has started to use a decontamination process “that goes above and beyond manufacturer and national standards” for the devices, the statement said. More than 100 patients who had an ERCP between October 2014 and January 2015 at UCLA have been notified they may have been infected with CRE.

The FDA statement includes recommendations for facilities and staff that reprocess duodenoscopes, for patients, and for health care professionals. One recommendation is to take a duodenoscope out of service if there is any suspicion it may be linked to a multidrug-resistant infection in a patient who has undergone ERCP.

In early March, another outbreak was reported at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, which announced that four patients who had undergone an ERCP procedure between August 2014 and January 2015 with the same duodenoscope had been infected with CRE, “despite the fact that Cedars-Sinai meticulously followed the disinfection procedure for duodenoscopes recommended in instructions provided by the manufacturer (Olympus Corporation) and the FDA.” This duodenoscope was the TJF-Q180 V model, a Cedars-Sinai spokesperson confirmed.

This particular duodenoscope has not yet been cleared for marketing, but has been used commercially, according to an FDA statement March 4 updating the duodenoscope-associated infection issue. The statement said that there was “no evidence” that the lack of clearance was associated with infections, and that the reported infections were associated with duodenoscopes from all three manufacturers of the devices used in the United States. In addition, the FDA statement noted that if the TJF-Q180 V duodenoscope was removed from the market, there may not be enough duodenoscopes to meet “the clinical demand in the United States of approximately 500,000 procedures per year.”

At the advisory panel meeting May 14-15, the FDA will ask the expert panel to discuss and make recommendations on various issues, including approaches that ensure patient safety during ERCP procedures and the effectiveness of the cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization procedures for duodenoscopes.

The FDA is asking health care professionals to report any infections possibly related to ERCP duodenoscopes to the manufacturers and the FDA’s MedWatch program.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has provided an interim protocol for health care facilities, with information on monitoring for bacterial contamination of duodenoscopes after reprocessing and other reprocessing issues.

Recommendations to manufacturers about improving the safety of reusable medical devices and an upcoming advisory committee meeting on duodenoscope-associated infections are two efforts recently announced by the Food and Drug Administration that address the risks associated with reusable devices.

A final guidance document for industry on reprocessing reusable medical devices includes recommendations “aimed at helping device manufacturers develop safer reusable devices, especially those devices that pose a greater risk of infection,” according to the March 12 announcement. Also included in the guidance are criteria that should be met in instructions for reprocessing reusable devices, “to ensure users understand and correctly follow the reprocessing instructions,” and recommendations that manufacturers should consider “reprocessing challenges” at the early stages of the design of such devices.

The same announcement said that in mid-May, the FDA was convening a 2-day meeting of the agency’s Gastroenterology and Urology Devices Panel to discuss the recent reports of infections associated with the use of duodenoscopes in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures in U.S. hospitals.

The announcement was issued less than a month after the agency alerted health care professionals and the public about the association with duodenoscopes and the transmission of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in patients who had undergone ERCP procedures, despite proper cleaning and disinfection of the devices. Between January 2013 and December 2014, the agency received 75 medical device adverse event reports for about 135 patients in the United States “relating to possible microbial transmission from reprocessed duodenoscopes,” according to the safety communication issued by the FDA on Feb. 19.

These reports and cases described in the medical literature have occurred even when manufacturer instructions for cleaning and sterilization were followed.

“Although the complex design of duodenoscopes improves the efficiency and effectiveness of ERCP, it causes challenges for cleaning and high-level disinfection,” according to the statement, which pointed out that it can be difficult to access some parts of the duodenoscopes when they are cleaned. Problems include the “elevator” mechanism at the tip of the duodenoscope, which should be manually brushed, but a brush may not be able to reach microscopic crevices in this mechanism and “residual body fluids and organic debris may remain in these crevices after cleaning and disinfection,” possibly exposing patients to serious infections if the fluids are contaminated with microbes.

The infections reported include carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), according to the first FDA statement, which did not mention whether any of the reports were fatal.

But on Feb. 18, the UCLA Health System announced that CRE may have been transmitted to seven patients during ERCP procedures, and may have contributed to the death of two of the patients. The two devices implicated in these cases are no longer used and the medical center has started to use a decontamination process “that goes above and beyond manufacturer and national standards” for the devices, the statement said. More than 100 patients who had an ERCP between October 2014 and January 2015 at UCLA have been notified they may have been infected with CRE.

The FDA statement includes recommendations for facilities and staff that reprocess duodenoscopes, for patients, and for health care professionals. One recommendation is to take a duodenoscope out of service if there is any suspicion it may be linked to a multidrug-resistant infection in a patient who has undergone ERCP.

In early March, another outbreak was reported at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, which announced that four patients who had undergone an ERCP procedure between August 2014 and January 2015 with the same duodenoscope had been infected with CRE, “despite the fact that Cedars-Sinai meticulously followed the disinfection procedure for duodenoscopes recommended in instructions provided by the manufacturer (Olympus Corporation) and the FDA.” This duodenoscope was the TJF-Q180 V model, a Cedars-Sinai spokesperson confirmed.

This particular duodenoscope has not yet been cleared for marketing, but has been used commercially, according to an FDA statement March 4 updating the duodenoscope-associated infection issue. The statement said that there was “no evidence” that the lack of clearance was associated with infections, and that the reported infections were associated with duodenoscopes from all three manufacturers of the devices used in the United States. In addition, the FDA statement noted that if the TJF-Q180 V duodenoscope was removed from the market, there may not be enough duodenoscopes to meet “the clinical demand in the United States of approximately 500,000 procedures per year.”

At the advisory panel meeting May 14-15, the FDA will ask the expert panel to discuss and make recommendations on various issues, including approaches that ensure patient safety during ERCP procedures and the effectiveness of the cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization procedures for duodenoscopes.

The FDA is asking health care professionals to report any infections possibly related to ERCP duodenoscopes to the manufacturers and the FDA’s MedWatch program.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has provided an interim protocol for health care facilities, with information on monitoring for bacterial contamination of duodenoscopes after reprocessing and other reprocessing issues.

Recommendations to manufacturers about improving the safety of reusable medical devices and an upcoming advisory committee meeting on duodenoscope-associated infections are two efforts recently announced by the Food and Drug Administration that address the risks associated with reusable devices.

A final guidance document for industry on reprocessing reusable medical devices includes recommendations “aimed at helping device manufacturers develop safer reusable devices, especially those devices that pose a greater risk of infection,” according to the March 12 announcement. Also included in the guidance are criteria that should be met in instructions for reprocessing reusable devices, “to ensure users understand and correctly follow the reprocessing instructions,” and recommendations that manufacturers should consider “reprocessing challenges” at the early stages of the design of such devices.

The same announcement said that in mid-May, the FDA was convening a 2-day meeting of the agency’s Gastroenterology and Urology Devices Panel to discuss the recent reports of infections associated with the use of duodenoscopes in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures in U.S. hospitals.

The announcement was issued less than a month after the agency alerted health care professionals and the public about the association with duodenoscopes and the transmission of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in patients who had undergone ERCP procedures, despite proper cleaning and disinfection of the devices. Between January 2013 and December 2014, the agency received 75 medical device adverse event reports for about 135 patients in the United States “relating to possible microbial transmission from reprocessed duodenoscopes,” according to the safety communication issued by the FDA on Feb. 19.

These reports and cases described in the medical literature have occurred even when manufacturer instructions for cleaning and sterilization were followed.

“Although the complex design of duodenoscopes improves the efficiency and effectiveness of ERCP, it causes challenges for cleaning and high-level disinfection,” according to the statement, which pointed out that it can be difficult to access some parts of the duodenoscopes when they are cleaned. Problems include the “elevator” mechanism at the tip of the duodenoscope, which should be manually brushed, but a brush may not be able to reach microscopic crevices in this mechanism and “residual body fluids and organic debris may remain in these crevices after cleaning and disinfection,” possibly exposing patients to serious infections if the fluids are contaminated with microbes.

The infections reported include carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), according to the first FDA statement, which did not mention whether any of the reports were fatal.

But on Feb. 18, the UCLA Health System announced that CRE may have been transmitted to seven patients during ERCP procedures, and may have contributed to the death of two of the patients. The two devices implicated in these cases are no longer used and the medical center has started to use a decontamination process “that goes above and beyond manufacturer and national standards” for the devices, the statement said. More than 100 patients who had an ERCP between October 2014 and January 2015 at UCLA have been notified they may have been infected with CRE.

The FDA statement includes recommendations for facilities and staff that reprocess duodenoscopes, for patients, and for health care professionals. One recommendation is to take a duodenoscope out of service if there is any suspicion it may be linked to a multidrug-resistant infection in a patient who has undergone ERCP.

In early March, another outbreak was reported at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, which announced that four patients who had undergone an ERCP procedure between August 2014 and January 2015 with the same duodenoscope had been infected with CRE, “despite the fact that Cedars-Sinai meticulously followed the disinfection procedure for duodenoscopes recommended in instructions provided by the manufacturer (Olympus Corporation) and the FDA.” This duodenoscope was the TJF-Q180 V model, a Cedars-Sinai spokesperson confirmed.

This particular duodenoscope has not yet been cleared for marketing, but has been used commercially, according to an FDA statement March 4 updating the duodenoscope-associated infection issue. The statement said that there was “no evidence” that the lack of clearance was associated with infections, and that the reported infections were associated with duodenoscopes from all three manufacturers of the devices used in the United States. In addition, the FDA statement noted that if the TJF-Q180 V duodenoscope was removed from the market, there may not be enough duodenoscopes to meet “the clinical demand in the United States of approximately 500,000 procedures per year.”

At the advisory panel meeting May 14-15, the FDA will ask the expert panel to discuss and make recommendations on various issues, including approaches that ensure patient safety during ERCP procedures and the effectiveness of the cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization procedures for duodenoscopes.

The FDA is asking health care professionals to report any infections possibly related to ERCP duodenoscopes to the manufacturers and the FDA’s MedWatch program.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has provided an interim protocol for health care facilities, with information on monitoring for bacterial contamination of duodenoscopes after reprocessing and other reprocessing issues.

Keeping your religious belief outside the office

Religion isn’t an uncommon topic in a doctor’s office, and mine is no exception. Patients often express their personal beliefs in difficult situations, and part of my job is to listen and support.

But when they ask me about my own, I don’t answer. I simply tell them that I don’t discuss such things with patients.

People can have pretty strong feelings about religion, and whether I agree or disagree with them doesn’t have a place in my office. Religion, like politics, opens a can of personal opinion worms that disrupts the doctor-patient relationship. It can make things unworkable.

The last thing I want, or need, during an appointment is a debate over evolution, the perennial Middle East crisis, or belief (or lack thereof) in a deity. There are plenty of good forums to argue such subjects, but my office isn’t one of them.

On rare occasions, someone calling for an appointment will ask about my religious orientation. My secretary has been told to say “I don’t know.” If that matters to you when you’re looking for a doctor, you’re probably better off going elsewhere.

I have nothing against social pleasantries. They’re part of the ordinary patter in my office, and help maintain a degree of doctor-patient comfort to let us talk openly. But religious beliefs are a topic that, with some people, can rapidly spiral out of control. On the rare occasions where they become acrimonious, it pretty much destroys the fabric of the professional relationship. So, my belief is that it’s best not to start in the first place.

Some find religion to be an important part of who they are, and I’m willing to listen to that and not be judgmental. But don’t expect me to share my own thoughts at an appointment. It’s not why either of us is there.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Religion isn’t an uncommon topic in a doctor’s office, and mine is no exception. Patients often express their personal beliefs in difficult situations, and part of my job is to listen and support.

But when they ask me about my own, I don’t answer. I simply tell them that I don’t discuss such things with patients.

People can have pretty strong feelings about religion, and whether I agree or disagree with them doesn’t have a place in my office. Religion, like politics, opens a can of personal opinion worms that disrupts the doctor-patient relationship. It can make things unworkable.

The last thing I want, or need, during an appointment is a debate over evolution, the perennial Middle East crisis, or belief (or lack thereof) in a deity. There are plenty of good forums to argue such subjects, but my office isn’t one of them.

On rare occasions, someone calling for an appointment will ask about my religious orientation. My secretary has been told to say “I don’t know.” If that matters to you when you’re looking for a doctor, you’re probably better off going elsewhere.

I have nothing against social pleasantries. They’re part of the ordinary patter in my office, and help maintain a degree of doctor-patient comfort to let us talk openly. But religious beliefs are a topic that, with some people, can rapidly spiral out of control. On the rare occasions where they become acrimonious, it pretty much destroys the fabric of the professional relationship. So, my belief is that it’s best not to start in the first place.

Some find religion to be an important part of who they are, and I’m willing to listen to that and not be judgmental. But don’t expect me to share my own thoughts at an appointment. It’s not why either of us is there.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Religion isn’t an uncommon topic in a doctor’s office, and mine is no exception. Patients often express their personal beliefs in difficult situations, and part of my job is to listen and support.

But when they ask me about my own, I don’t answer. I simply tell them that I don’t discuss such things with patients.

People can have pretty strong feelings about religion, and whether I agree or disagree with them doesn’t have a place in my office. Religion, like politics, opens a can of personal opinion worms that disrupts the doctor-patient relationship. It can make things unworkable.

The last thing I want, or need, during an appointment is a debate over evolution, the perennial Middle East crisis, or belief (or lack thereof) in a deity. There are plenty of good forums to argue such subjects, but my office isn’t one of them.

On rare occasions, someone calling for an appointment will ask about my religious orientation. My secretary has been told to say “I don’t know.” If that matters to you when you’re looking for a doctor, you’re probably better off going elsewhere.

I have nothing against social pleasantries. They’re part of the ordinary patter in my office, and help maintain a degree of doctor-patient comfort to let us talk openly. But religious beliefs are a topic that, with some people, can rapidly spiral out of control. On the rare occasions where they become acrimonious, it pretty much destroys the fabric of the professional relationship. So, my belief is that it’s best not to start in the first place.

Some find religion to be an important part of who they are, and I’m willing to listen to that and not be judgmental. But don’t expect me to share my own thoughts at an appointment. It’s not why either of us is there.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Storage time doesn’t affect blood quality, study shows

Photo by Elise Amendola

The length of time red blood cells (RBCs) are stored does not affect transfusion outcomes in critically ill patients, results of the ABLE study suggest.

Researchers compared critically ill patients who received RBCs stored for an average of about 3 weeks to those who received RBCs stored for less than a week.

And there were no significant differences between the groups with regard to mortality, transfusion reactions, and other outcomes.

“Previous observational and laboratory studies have suggested that fresh blood may be better because of the breakdown of red blood cells and accumulation of toxins during storage,” said Alan Tinmouth, MD, of the University of Ottawa in Ontario, Canada.

“But this definitive clinical trial clearly shows that these changes do not affect the quality of blood.”

Dr Tinmouth and his colleagues reported these results in NEJM.

The researchers enrolled 2430 adult intensive care patients in the trial, comparing patients who received fresh RBCs (n=1211) to those who received older RBCs (n=1219). Fresh RBCs were stored for a median of 6.1±4.9 days, and older RBCs were stored for a median of 22.0±8.4 days.

There was no significant difference between the arms with regard to the primary outcome, 90-day mortality. This endpoint was met by 37% of patients who received fresh blood and 35.3% of those who received older blood.

There were no significant differences between the fresh and older RBC arms for other mortality outcomes, either. This included death in the intensive care unit (26.7% vs 24.2%), in-hospital death (33.3% vs 31.9%), and death by day 28 (30.6% vs 28.8%).

Similarly, there were no significant differences between the fresh and older blood arms with regard to major illnesses, including multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (13.4% vs 13%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (5.7% vs 6.6%), cardiovascular failure (5.1% vs 4.2%), cardiac ischemia or infarction (4.5% vs 3.6%), venous thromboembolism (3.6% for both), nosocomial infection (34.1% vs 31.3%), and acute transfusion reaction (0.3% vs 0.5%).

In addition, there was no significant difference between the fresh RBC arm and the older RBC arm in the length of time patients required mechanical ventilation (15.0±18.0 days vs 14.7±14.9 days), cardiac or vasoactive drugs (7.1±10.2 days vs 7.5±11.2 days), or extrarenal epuration (2.5±10.1 days vs 2.5±8.3 days).

And there was no significant difference between the fresh and older blood arms in patients’ length of stay in the hospital (34.4±39.5 days vs 33.9±38.8 days) or the intensive care unit (15.3±15.4 days vs 15.3±14.8 days).

Based on these results, the researchers said there is no need to worry about the age of blood routinely used in hospitals. The team is now conducting a trial to determine if the same can be said for transfusions in pediatric patients. ![]()

Photo by Elise Amendola

The length of time red blood cells (RBCs) are stored does not affect transfusion outcomes in critically ill patients, results of the ABLE study suggest.

Researchers compared critically ill patients who received RBCs stored for an average of about 3 weeks to those who received RBCs stored for less than a week.

And there were no significant differences between the groups with regard to mortality, transfusion reactions, and other outcomes.

“Previous observational and laboratory studies have suggested that fresh blood may be better because of the breakdown of red blood cells and accumulation of toxins during storage,” said Alan Tinmouth, MD, of the University of Ottawa in Ontario, Canada.

“But this definitive clinical trial clearly shows that these changes do not affect the quality of blood.”

Dr Tinmouth and his colleagues reported these results in NEJM.

The researchers enrolled 2430 adult intensive care patients in the trial, comparing patients who received fresh RBCs (n=1211) to those who received older RBCs (n=1219). Fresh RBCs were stored for a median of 6.1±4.9 days, and older RBCs were stored for a median of 22.0±8.4 days.

There was no significant difference between the arms with regard to the primary outcome, 90-day mortality. This endpoint was met by 37% of patients who received fresh blood and 35.3% of those who received older blood.

There were no significant differences between the fresh and older RBC arms for other mortality outcomes, either. This included death in the intensive care unit (26.7% vs 24.2%), in-hospital death (33.3% vs 31.9%), and death by day 28 (30.6% vs 28.8%).

Similarly, there were no significant differences between the fresh and older blood arms with regard to major illnesses, including multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (13.4% vs 13%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (5.7% vs 6.6%), cardiovascular failure (5.1% vs 4.2%), cardiac ischemia or infarction (4.5% vs 3.6%), venous thromboembolism (3.6% for both), nosocomial infection (34.1% vs 31.3%), and acute transfusion reaction (0.3% vs 0.5%).

In addition, there was no significant difference between the fresh RBC arm and the older RBC arm in the length of time patients required mechanical ventilation (15.0±18.0 days vs 14.7±14.9 days), cardiac or vasoactive drugs (7.1±10.2 days vs 7.5±11.2 days), or extrarenal epuration (2.5±10.1 days vs 2.5±8.3 days).

And there was no significant difference between the fresh and older blood arms in patients’ length of stay in the hospital (34.4±39.5 days vs 33.9±38.8 days) or the intensive care unit (15.3±15.4 days vs 15.3±14.8 days).

Based on these results, the researchers said there is no need to worry about the age of blood routinely used in hospitals. The team is now conducting a trial to determine if the same can be said for transfusions in pediatric patients. ![]()

Photo by Elise Amendola

The length of time red blood cells (RBCs) are stored does not affect transfusion outcomes in critically ill patients, results of the ABLE study suggest.

Researchers compared critically ill patients who received RBCs stored for an average of about 3 weeks to those who received RBCs stored for less than a week.

And there were no significant differences between the groups with regard to mortality, transfusion reactions, and other outcomes.

“Previous observational and laboratory studies have suggested that fresh blood may be better because of the breakdown of red blood cells and accumulation of toxins during storage,” said Alan Tinmouth, MD, of the University of Ottawa in Ontario, Canada.

“But this definitive clinical trial clearly shows that these changes do not affect the quality of blood.”

Dr Tinmouth and his colleagues reported these results in NEJM.

The researchers enrolled 2430 adult intensive care patients in the trial, comparing patients who received fresh RBCs (n=1211) to those who received older RBCs (n=1219). Fresh RBCs were stored for a median of 6.1±4.9 days, and older RBCs were stored for a median of 22.0±8.4 days.

There was no significant difference between the arms with regard to the primary outcome, 90-day mortality. This endpoint was met by 37% of patients who received fresh blood and 35.3% of those who received older blood.

There were no significant differences between the fresh and older RBC arms for other mortality outcomes, either. This included death in the intensive care unit (26.7% vs 24.2%), in-hospital death (33.3% vs 31.9%), and death by day 28 (30.6% vs 28.8%).

Similarly, there were no significant differences between the fresh and older blood arms with regard to major illnesses, including multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (13.4% vs 13%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (5.7% vs 6.6%), cardiovascular failure (5.1% vs 4.2%), cardiac ischemia or infarction (4.5% vs 3.6%), venous thromboembolism (3.6% for both), nosocomial infection (34.1% vs 31.3%), and acute transfusion reaction (0.3% vs 0.5%).

In addition, there was no significant difference between the fresh RBC arm and the older RBC arm in the length of time patients required mechanical ventilation (15.0±18.0 days vs 14.7±14.9 days), cardiac or vasoactive drugs (7.1±10.2 days vs 7.5±11.2 days), or extrarenal epuration (2.5±10.1 days vs 2.5±8.3 days).

And there was no significant difference between the fresh and older blood arms in patients’ length of stay in the hospital (34.4±39.5 days vs 33.9±38.8 days) or the intensive care unit (15.3±15.4 days vs 15.3±14.8 days).

Based on these results, the researchers said there is no need to worry about the age of blood routinely used in hospitals. The team is now conducting a trial to determine if the same can be said for transfusions in pediatric patients. ![]()

Bivalirudin bests heparin in patients with AMI

Data from the BRIGHT trial suggest bivalirudin may be more suitable than heparin alone or heparin plus tirofiban as anticoagulant therapy for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who are undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

At 30 days and 1 year after PCI, patients who received bivalirudin had a lower rate of net adverse clinical events (NACE)—death, reinfarction, bleeding, and

other events—than patients who received heparin.

Complete results from this study were published in JAMA alongside a related editorial.

Research has yet to reveal the optimal anticoagulant strategy for patients with AMI. Previous multicenter trials, such as HORIZONS-AMI and EUROMAX, have suggested that bivalirudin is superior to heparin plus glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. But a recent single-center trial, HEAT-PPCI, indicated that heparin monotherapy was superior to bivalirudin alone.

So Gregg W. Stone, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center in New York, New York, and his colleagues conducted the BRIGHT trial to gain some insight into the issue.

The team analyzed 2194 patients with AMI who underwent emergency PCI at 82 Chinese sites. The patients were randomized to receive bivalirudin with a post-PCI infusion (n=735), heparin alone (n=729), or heparin plus tirofiban with a post-PCI infusion (n=730).

The primary endpoint was 30-day NACE, a composite of major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCE) and bleeding. The secondary endpoints were NACE at 1 year, as well as MACCE and bleeding at 30 days and 1 year.

MACCE includes all-cause death, reinfarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, and stroke. Bleeding was defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) definition.

At 30 days, NACE had occurred in 8.8% of bivalirudin-treated patients, 13.2% of heparin-treated patients, and 17.0% of patients who received heparin plus tirofiban. The relative risk (RR) for bivalirudin vs heparin was 0.67 (P=0.008), and the RR for bivalirudin vs heparin plus tirofiban was 0.52 (P<0.001).

Patients who received bivalirudin had a lower rate of bleeding at 30 days than patients who received heparin or heparin plus tirofiban—4.1%, 7.5%, and 12.3% respectively (P<0.001).

There were no significant differences between treatments in the 30-day rates of MACCE (5.0%, 5.8%, and 4.9% respectively, P=0.74) and stent thrombosis (0.6%, 0.9%, and 0.7%, respectively, P=0.77). And there was no significant difference in acute (<24 hour) stent thrombosis (0.3% in each group).

At 1 year, patients in the bivalirudin arm still had a lower rate of NACE compared to patients in the heparin arm (12.8% vs 16.5%, RR=0.78, P=0.048) or patients who received heparin plus tirofiban (12.8% vs 20.5%, RR=0.62, P<0.001), due to lower rates of bleeding.

Rates of MACCE and stent thrombosis at 1 year were not significantly different between the treatment arms.

“By reducing bleeding with comparable rates of MACCE and stent thrombosis, bivalirudin significantly improved overall 30-day and 1-year outcomes, compared with both heparin alone and heparin plus tirofiban in patients with AMI undergoing primary PCI,” Dr Stone concluded.

The BRIGHT trial was funded, in part, by Salubris Pharmaceutical Co., makers of bivalirudin. Other funding came from the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region and the Chinese Government National Key R&D project for the 12th five-year plan. ![]()

Data from the BRIGHT trial suggest bivalirudin may be more suitable than heparin alone or heparin plus tirofiban as anticoagulant therapy for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who are undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

At 30 days and 1 year after PCI, patients who received bivalirudin had a lower rate of net adverse clinical events (NACE)—death, reinfarction, bleeding, and

other events—than patients who received heparin.

Complete results from this study were published in JAMA alongside a related editorial.

Research has yet to reveal the optimal anticoagulant strategy for patients with AMI. Previous multicenter trials, such as HORIZONS-AMI and EUROMAX, have suggested that bivalirudin is superior to heparin plus glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. But a recent single-center trial, HEAT-PPCI, indicated that heparin monotherapy was superior to bivalirudin alone.

So Gregg W. Stone, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center in New York, New York, and his colleagues conducted the BRIGHT trial to gain some insight into the issue.

The team analyzed 2194 patients with AMI who underwent emergency PCI at 82 Chinese sites. The patients were randomized to receive bivalirudin with a post-PCI infusion (n=735), heparin alone (n=729), or heparin plus tirofiban with a post-PCI infusion (n=730).

The primary endpoint was 30-day NACE, a composite of major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCE) and bleeding. The secondary endpoints were NACE at 1 year, as well as MACCE and bleeding at 30 days and 1 year.

MACCE includes all-cause death, reinfarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, and stroke. Bleeding was defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) definition.

At 30 days, NACE had occurred in 8.8% of bivalirudin-treated patients, 13.2% of heparin-treated patients, and 17.0% of patients who received heparin plus tirofiban. The relative risk (RR) for bivalirudin vs heparin was 0.67 (P=0.008), and the RR for bivalirudin vs heparin plus tirofiban was 0.52 (P<0.001).

Patients who received bivalirudin had a lower rate of bleeding at 30 days than patients who received heparin or heparin plus tirofiban—4.1%, 7.5%, and 12.3% respectively (P<0.001).

There were no significant differences between treatments in the 30-day rates of MACCE (5.0%, 5.8%, and 4.9% respectively, P=0.74) and stent thrombosis (0.6%, 0.9%, and 0.7%, respectively, P=0.77). And there was no significant difference in acute (<24 hour) stent thrombosis (0.3% in each group).

At 1 year, patients in the bivalirudin arm still had a lower rate of NACE compared to patients in the heparin arm (12.8% vs 16.5%, RR=0.78, P=0.048) or patients who received heparin plus tirofiban (12.8% vs 20.5%, RR=0.62, P<0.001), due to lower rates of bleeding.

Rates of MACCE and stent thrombosis at 1 year were not significantly different between the treatment arms.

“By reducing bleeding with comparable rates of MACCE and stent thrombosis, bivalirudin significantly improved overall 30-day and 1-year outcomes, compared with both heparin alone and heparin plus tirofiban in patients with AMI undergoing primary PCI,” Dr Stone concluded.

The BRIGHT trial was funded, in part, by Salubris Pharmaceutical Co., makers of bivalirudin. Other funding came from the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region and the Chinese Government National Key R&D project for the 12th five-year plan. ![]()

Data from the BRIGHT trial suggest bivalirudin may be more suitable than heparin alone or heparin plus tirofiban as anticoagulant therapy for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who are undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

At 30 days and 1 year after PCI, patients who received bivalirudin had a lower rate of net adverse clinical events (NACE)—death, reinfarction, bleeding, and

other events—than patients who received heparin.

Complete results from this study were published in JAMA alongside a related editorial.

Research has yet to reveal the optimal anticoagulant strategy for patients with AMI. Previous multicenter trials, such as HORIZONS-AMI and EUROMAX, have suggested that bivalirudin is superior to heparin plus glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. But a recent single-center trial, HEAT-PPCI, indicated that heparin monotherapy was superior to bivalirudin alone.

So Gregg W. Stone, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center in New York, New York, and his colleagues conducted the BRIGHT trial to gain some insight into the issue.

The team analyzed 2194 patients with AMI who underwent emergency PCI at 82 Chinese sites. The patients were randomized to receive bivalirudin with a post-PCI infusion (n=735), heparin alone (n=729), or heparin plus tirofiban with a post-PCI infusion (n=730).

The primary endpoint was 30-day NACE, a composite of major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCE) and bleeding. The secondary endpoints were NACE at 1 year, as well as MACCE and bleeding at 30 days and 1 year.

MACCE includes all-cause death, reinfarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, and stroke. Bleeding was defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) definition.

At 30 days, NACE had occurred in 8.8% of bivalirudin-treated patients, 13.2% of heparin-treated patients, and 17.0% of patients who received heparin plus tirofiban. The relative risk (RR) for bivalirudin vs heparin was 0.67 (P=0.008), and the RR for bivalirudin vs heparin plus tirofiban was 0.52 (P<0.001).

Patients who received bivalirudin had a lower rate of bleeding at 30 days than patients who received heparin or heparin plus tirofiban—4.1%, 7.5%, and 12.3% respectively (P<0.001).

There were no significant differences between treatments in the 30-day rates of MACCE (5.0%, 5.8%, and 4.9% respectively, P=0.74) and stent thrombosis (0.6%, 0.9%, and 0.7%, respectively, P=0.77). And there was no significant difference in acute (<24 hour) stent thrombosis (0.3% in each group).

At 1 year, patients in the bivalirudin arm still had a lower rate of NACE compared to patients in the heparin arm (12.8% vs 16.5%, RR=0.78, P=0.048) or patients who received heparin plus tirofiban (12.8% vs 20.5%, RR=0.62, P<0.001), due to lower rates of bleeding.

Rates of MACCE and stent thrombosis at 1 year were not significantly different between the treatment arms.

“By reducing bleeding with comparable rates of MACCE and stent thrombosis, bivalirudin significantly improved overall 30-day and 1-year outcomes, compared with both heparin alone and heparin plus tirofiban in patients with AMI undergoing primary PCI,” Dr Stone concluded.

The BRIGHT trial was funded, in part, by Salubris Pharmaceutical Co., makers of bivalirudin. Other funding came from the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region and the Chinese Government National Key R&D project for the 12th five-year plan. ![]()

EC approves drug for polycythemia vera

Image courtesy of AFIP

The European Commission (EC) has approved ruxolitinib (Jakavi) to treat adults with polycythemia vera (PV) who are resistant to or cannot tolerate hydroxyurea.

This is the first targeted treatment the EC has approved for these patients.

The approval applies to all 28 member states of the European Union (EU), plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

Ruxolitinib is already approved to treat PV in the US, and additional regulatory applications for ruxolitinib in PV are ongoing worldwide.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with primary myelofibrosis (MF), post-PV MF, or post-essential thrombocythemia MF in more than 70 countries, including EU member states and the US.

“The European Commission’s approval of Jakavi [for PV] is encouraging news for patients,” said Claire Harrison, MD, a consultant hematologist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, England.

“Jakavi will fill an unmet need as the first treatment shown to significantly improve hematocrit, as well as symptom control and reduce spleen size in patients with polycythemia vera resistant to or intolerant of hydroxyurea.”

RESPONSE trial

The EC’s approval is based on data from the phase 3 RESPONSE trial. The study included 222 patients who had PV for at least 24 weeks. All patients had an inadequate response to or could not tolerate hydroxyurea, had undergone a phlebotomy, and had splenomegaly.

Patients were randomized to receive ruxolitinib starting at 10 mg twice daily or best available therapy (BAT) as determined by the investigator. The ruxolitinib dose was adjusted as needed.

The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of hematocrit control and spleen reduction. To meet the endpoint, patients had to experience a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume from baseline, as assessed by imaging at week 32.

And a patient’s hematocrit was considered under control if he was not eligible for phlebotomy from week 8 through 32 (and had no more than one instance of phlebotomy eligibility between randomization and week 8). Patients who were deemed eligible for phlebotomy had hematocrit that was greater than 45% or had increased 3 or more percentage points from the time they entered the study.

Twenty-one percent of ruxolitinib-treated patients met this endpoint (achieving hematocrit control and spleen reduction), compared to 1% of patients who received BAT (P<0.001).

And the researchers said ruxolitinib was well-tolerated. Common adverse events included headache, diarrhea, and fatigue.

Grade 3/4 anemia, grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia, and herpes zoster infections of all grades were more common in the ruxolitinib arm than the BAT arm. But thromboembolic events were more common with BAT than ruxolitinib.

This trial was funded by the Incyte Corporation, which markets ruxolitinib in the US. Novartis licensed ruxolitinib from Incyte for development and commercialization outside the US.

For more details on ruxolitinib, see the full prescribing information, available at www.jakavi.com. ![]()

Image courtesy of AFIP

The European Commission (EC) has approved ruxolitinib (Jakavi) to treat adults with polycythemia vera (PV) who are resistant to or cannot tolerate hydroxyurea.

This is the first targeted treatment the EC has approved for these patients.

The approval applies to all 28 member states of the European Union (EU), plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

Ruxolitinib is already approved to treat PV in the US, and additional regulatory applications for ruxolitinib in PV are ongoing worldwide.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with primary myelofibrosis (MF), post-PV MF, or post-essential thrombocythemia MF in more than 70 countries, including EU member states and the US.

“The European Commission’s approval of Jakavi [for PV] is encouraging news for patients,” said Claire Harrison, MD, a consultant hematologist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, England.

“Jakavi will fill an unmet need as the first treatment shown to significantly improve hematocrit, as well as symptom control and reduce spleen size in patients with polycythemia vera resistant to or intolerant of hydroxyurea.”

RESPONSE trial

The EC’s approval is based on data from the phase 3 RESPONSE trial. The study included 222 patients who had PV for at least 24 weeks. All patients had an inadequate response to or could not tolerate hydroxyurea, had undergone a phlebotomy, and had splenomegaly.

Patients were randomized to receive ruxolitinib starting at 10 mg twice daily or best available therapy (BAT) as determined by the investigator. The ruxolitinib dose was adjusted as needed.

The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of hematocrit control and spleen reduction. To meet the endpoint, patients had to experience a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume from baseline, as assessed by imaging at week 32.

And a patient’s hematocrit was considered under control if he was not eligible for phlebotomy from week 8 through 32 (and had no more than one instance of phlebotomy eligibility between randomization and week 8). Patients who were deemed eligible for phlebotomy had hematocrit that was greater than 45% or had increased 3 or more percentage points from the time they entered the study.

Twenty-one percent of ruxolitinib-treated patients met this endpoint (achieving hematocrit control and spleen reduction), compared to 1% of patients who received BAT (P<0.001).

And the researchers said ruxolitinib was well-tolerated. Common adverse events included headache, diarrhea, and fatigue.

Grade 3/4 anemia, grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia, and herpes zoster infections of all grades were more common in the ruxolitinib arm than the BAT arm. But thromboembolic events were more common with BAT than ruxolitinib.

This trial was funded by the Incyte Corporation, which markets ruxolitinib in the US. Novartis licensed ruxolitinib from Incyte for development and commercialization outside the US.

For more details on ruxolitinib, see the full prescribing information, available at www.jakavi.com. ![]()

Image courtesy of AFIP

The European Commission (EC) has approved ruxolitinib (Jakavi) to treat adults with polycythemia vera (PV) who are resistant to or cannot tolerate hydroxyurea.

This is the first targeted treatment the EC has approved for these patients.

The approval applies to all 28 member states of the European Union (EU), plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

Ruxolitinib is already approved to treat PV in the US, and additional regulatory applications for ruxolitinib in PV are ongoing worldwide.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with primary myelofibrosis (MF), post-PV MF, or post-essential thrombocythemia MF in more than 70 countries, including EU member states and the US.

“The European Commission’s approval of Jakavi [for PV] is encouraging news for patients,” said Claire Harrison, MD, a consultant hematologist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, England.

“Jakavi will fill an unmet need as the first treatment shown to significantly improve hematocrit, as well as symptom control and reduce spleen size in patients with polycythemia vera resistant to or intolerant of hydroxyurea.”

RESPONSE trial

The EC’s approval is based on data from the phase 3 RESPONSE trial. The study included 222 patients who had PV for at least 24 weeks. All patients had an inadequate response to or could not tolerate hydroxyurea, had undergone a phlebotomy, and had splenomegaly.

Patients were randomized to receive ruxolitinib starting at 10 mg twice daily or best available therapy (BAT) as determined by the investigator. The ruxolitinib dose was adjusted as needed.

The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of hematocrit control and spleen reduction. To meet the endpoint, patients had to experience a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume from baseline, as assessed by imaging at week 32.

And a patient’s hematocrit was considered under control if he was not eligible for phlebotomy from week 8 through 32 (and had no more than one instance of phlebotomy eligibility between randomization and week 8). Patients who were deemed eligible for phlebotomy had hematocrit that was greater than 45% or had increased 3 or more percentage points from the time they entered the study.

Twenty-one percent of ruxolitinib-treated patients met this endpoint (achieving hematocrit control and spleen reduction), compared to 1% of patients who received BAT (P<0.001).

And the researchers said ruxolitinib was well-tolerated. Common adverse events included headache, diarrhea, and fatigue.

Grade 3/4 anemia, grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia, and herpes zoster infections of all grades were more common in the ruxolitinib arm than the BAT arm. But thromboembolic events were more common with BAT than ruxolitinib.

This trial was funded by the Incyte Corporation, which markets ruxolitinib in the US. Novartis licensed ruxolitinib from Incyte for development and commercialization outside the US.

For more details on ruxolitinib, see the full prescribing information, available at www.jakavi.com. ![]()

4F-PCC proves more effective than plasma

Photo by Cristina Granados

Results of a phase 3 trial indicate that a 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (4F-PCC) is more effective than plasma for reversing acquired coagulation factor deficiency induced by vitamin K antagonist therapy in adults who require urgent surgery or an invasive procedure.

4F-PCC induced hemostasis in more patients and reduced international normalized ratios (INRs) more quickly than plasma.

And the rates of adverse events (AEs) were similar in the 2 groups.

“[4F-PCC] is more effective than plasma for INR reduction and periprocedural hemostasis in adults who are taking warfarin and require an urgent procedure,” said Joshua N. Goldstein, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

He and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet.

The study included 181 patients, but only 168 were evaluable for efficacy. Eighty-seven of these patients received 4F-PCC, and 81 received plasma.

Ninety percent of patients treated with 4F-PCC achieved effective hemostasis, compared to 75% of patients treated with plasma (P=0.0142).

Fifty-five percent of patients who received 4F-PCC achieved rapid INR reduction (to ≤ 1.3 at 30 minutes after the end of infusion), compared to 10% of patients treated with plasma (P<0.0001).

In post-hoc analysis, the median time from the start of infusion to the start of the urgent surgical procedure was shorter in the 4F-PCC group than in the plasma group—3.6 hours and 8.5 hours, respectively (P=0.0098).

Eighty-eight patients in each group were evaluable for safety. And the incidence of AEs was similar in the 4F-PCC and plasma groups, at 56% and 60%, respectively.

Treatment-related AEs occurred in 9% of 4F-PCC-treated patients and 17% of plasma-treated patients. In both groups, 3% of these AEs were serious.

The rate of death at day 45 was 3% in the 4F-PCC group and 9% in the plasma group. The rates of thromboembolic AEs were 7% and 8%, respectively.

The rates of fluid overload or similar cardiac events were 3% and 13%, respectively. And the rates of bleeding after the primary outcome assessment were 3% and 5%, respectively.

This study was funded by CSL Behring, makers of 4F-PCC, which is marketed as Kcentra, Beriplex, or Confidex. ![]()

Photo by Cristina Granados

Results of a phase 3 trial indicate that a 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (4F-PCC) is more effective than plasma for reversing acquired coagulation factor deficiency induced by vitamin K antagonist therapy in adults who require urgent surgery or an invasive procedure.

4F-PCC induced hemostasis in more patients and reduced international normalized ratios (INRs) more quickly than plasma.

And the rates of adverse events (AEs) were similar in the 2 groups.

“[4F-PCC] is more effective than plasma for INR reduction and periprocedural hemostasis in adults who are taking warfarin and require an urgent procedure,” said Joshua N. Goldstein, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

He and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet.

The study included 181 patients, but only 168 were evaluable for efficacy. Eighty-seven of these patients received 4F-PCC, and 81 received plasma.

Ninety percent of patients treated with 4F-PCC achieved effective hemostasis, compared to 75% of patients treated with plasma (P=0.0142).

Fifty-five percent of patients who received 4F-PCC achieved rapid INR reduction (to ≤ 1.3 at 30 minutes after the end of infusion), compared to 10% of patients treated with plasma (P<0.0001).

In post-hoc analysis, the median time from the start of infusion to the start of the urgent surgical procedure was shorter in the 4F-PCC group than in the plasma group—3.6 hours and 8.5 hours, respectively (P=0.0098).

Eighty-eight patients in each group were evaluable for safety. And the incidence of AEs was similar in the 4F-PCC and plasma groups, at 56% and 60%, respectively.

Treatment-related AEs occurred in 9% of 4F-PCC-treated patients and 17% of plasma-treated patients. In both groups, 3% of these AEs were serious.

The rate of death at day 45 was 3% in the 4F-PCC group and 9% in the plasma group. The rates of thromboembolic AEs were 7% and 8%, respectively.

The rates of fluid overload or similar cardiac events were 3% and 13%, respectively. And the rates of bleeding after the primary outcome assessment were 3% and 5%, respectively.

This study was funded by CSL Behring, makers of 4F-PCC, which is marketed as Kcentra, Beriplex, or Confidex. ![]()

Photo by Cristina Granados

Results of a phase 3 trial indicate that a 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (4F-PCC) is more effective than plasma for reversing acquired coagulation factor deficiency induced by vitamin K antagonist therapy in adults who require urgent surgery or an invasive procedure.

4F-PCC induced hemostasis in more patients and reduced international normalized ratios (INRs) more quickly than plasma.

And the rates of adverse events (AEs) were similar in the 2 groups.

“[4F-PCC] is more effective than plasma for INR reduction and periprocedural hemostasis in adults who are taking warfarin and require an urgent procedure,” said Joshua N. Goldstein, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

He and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet.

The study included 181 patients, but only 168 were evaluable for efficacy. Eighty-seven of these patients received 4F-PCC, and 81 received plasma.

Ninety percent of patients treated with 4F-PCC achieved effective hemostasis, compared to 75% of patients treated with plasma (P=0.0142).

Fifty-five percent of patients who received 4F-PCC achieved rapid INR reduction (to ≤ 1.3 at 30 minutes after the end of infusion), compared to 10% of patients treated with plasma (P<0.0001).

In post-hoc analysis, the median time from the start of infusion to the start of the urgent surgical procedure was shorter in the 4F-PCC group than in the plasma group—3.6 hours and 8.5 hours, respectively (P=0.0098).

Eighty-eight patients in each group were evaluable for safety. And the incidence of AEs was similar in the 4F-PCC and plasma groups, at 56% and 60%, respectively.

Treatment-related AEs occurred in 9% of 4F-PCC-treated patients and 17% of plasma-treated patients. In both groups, 3% of these AEs were serious.

The rate of death at day 45 was 3% in the 4F-PCC group and 9% in the plasma group. The rates of thromboembolic AEs were 7% and 8%, respectively.

The rates of fluid overload or similar cardiac events were 3% and 13%, respectively. And the rates of bleeding after the primary outcome assessment were 3% and 5%, respectively.

This study was funded by CSL Behring, makers of 4F-PCC, which is marketed as Kcentra, Beriplex, or Confidex. ![]()

LISTEN NOW: My iPad Went to Medical School

Mobile devices put information in the palm of your hand. For hospitalists, this presents real opportunities to engage patients, improve care, and streamline hospital workflows. Two hospitalists who were early adopters of mobile tech in their practices, Dr. Henry Feldman of Beth Israel Deaconess and Dr. Richard Pittman of Emory University/Grady share their lessons learned, and their advice for other hospital clinicians and informaticists on using mobile tech in their practices.

Mobile devices put information in the palm of your hand. For hospitalists, this presents real opportunities to engage patients, improve care, and streamline hospital workflows. Two hospitalists who were early adopters of mobile tech in their practices, Dr. Henry Feldman of Beth Israel Deaconess and Dr. Richard Pittman of Emory University/Grady share their lessons learned, and their advice for other hospital clinicians and informaticists on using mobile tech in their practices.

Mobile devices put information in the palm of your hand. For hospitalists, this presents real opportunities to engage patients, improve care, and streamline hospital workflows. Two hospitalists who were early adopters of mobile tech in their practices, Dr. Henry Feldman of Beth Israel Deaconess and Dr. Richard Pittman of Emory University/Grady share their lessons learned, and their advice for other hospital clinicians and informaticists on using mobile tech in their practices.

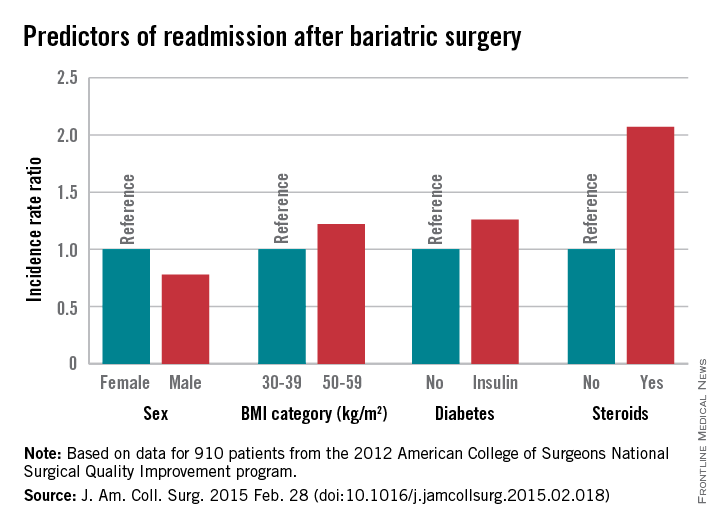

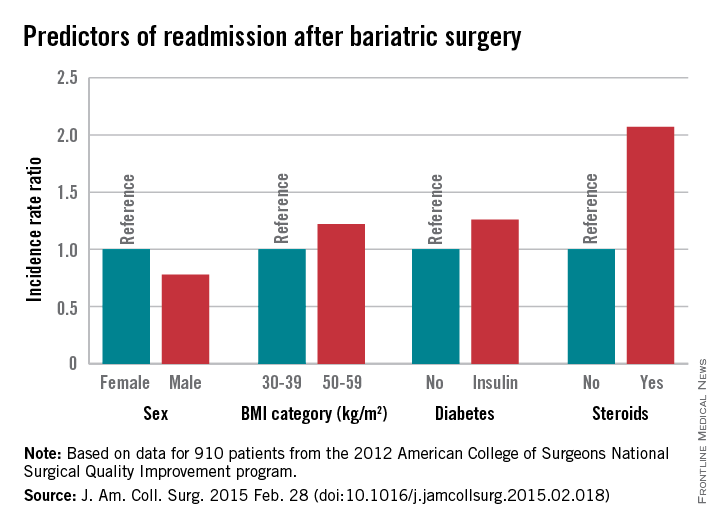

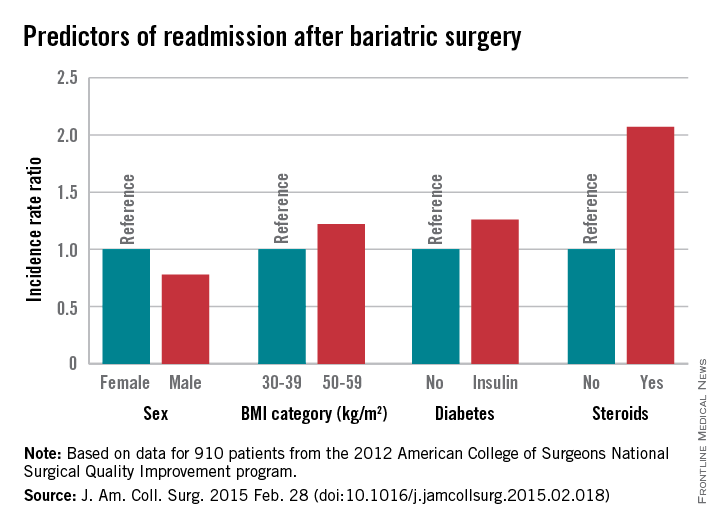

Several factors predict postbariatric surgery readmission

Bariatric surgery is generally safe and readmissions are rare, but prolonged operative time, operation complexity, and major postoperative complications are among several risk factors for readmission identified in a large retrospective cohort.

Of 18,186 patients from the 2012 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement program (ACS NSQIP) database who had bariatric surgery as a primary procedure, 5% were readmitted. Of 815 patients with any major complication, 31% were readmitted. Factors found on multivariate analysis to significantly predict readmission within 30 days were age, sex, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) risk class, diabetes status, hypertension, and steroid use, Dr. Christa R. Abraham of Albany (N.Y.) Medical College and her colleagues reported online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Further, all major postoperative complications were significant predictors of readmission, including bleeding requiring transfusion, urinary tract infections, and superficial surgical site infection (SSI). Other significant predictors were deep SSI, organ space SSI, wound disruption, pneumonia, unplanned intubation, mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and sepsis, the investigators said (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.018]).

Of the patients included in the study, 1,819 had a laparoscopic gastric band, 9,613 had laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 6,439 had gastroplasties, and 315 had open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. All had a BMI of at least 30 kg/m2, and had a postsurgery length of stay of 14 days or fewer. Most were ASA risk class 3 or lower, and most were functionally independent.

Complications were more common with laparoscopic and open Roux-en-y gastric bypass (5.5% and 11.8%, respectively) rather than with gastroplasty and sleeve (3.4%) and laparoscopic banding (1.4%).

The findings are of value, because while bariatric surgery is a low-risk procedure, and it is extremely common; in 2013 there were 179,000 such surgeries performed in the United States.

“Bariatric surgery is one of the fastest-growing surgical interest areas, making analysis of patient outcomes and reasons for readmission important,” the investigators explained.

The ability to identify high-risk patients could allow for targeted interventions to prevent readmission, they said.

For example, steroid use, which was identified as a risk factor in the current study, is modifiable.

“In our practice, steroids are discontinued for 6 weeks prior to bariatric surgery and patients who are steroid dependent are unlikely to undergo bariatric surgery,” they said.

Additionally, they “try to minimize readmission for patients with infections by treating with antibiotics following operation and continuing antibiotics at discharge.”

The investigators noted that the ACS NSQIP MORBPROB (estimated probability of morbidity) tool is a good tool for predicting readmission among prospective bariatric patients, although it may not fully capture the effect of preexisting conditions.

“These data led us to change our own practice by risk-stratifying patients with higher ASA and BMI to consider surgical options, and to begin early surveillance soon after discharge,” they said.

The authors reported having no disclosures.

Bariatric surgery is generally safe and readmissions are rare, but prolonged operative time, operation complexity, and major postoperative complications are among several risk factors for readmission identified in a large retrospective cohort.

Of 18,186 patients from the 2012 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement program (ACS NSQIP) database who had bariatric surgery as a primary procedure, 5% were readmitted. Of 815 patients with any major complication, 31% were readmitted. Factors found on multivariate analysis to significantly predict readmission within 30 days were age, sex, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) risk class, diabetes status, hypertension, and steroid use, Dr. Christa R. Abraham of Albany (N.Y.) Medical College and her colleagues reported online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Further, all major postoperative complications were significant predictors of readmission, including bleeding requiring transfusion, urinary tract infections, and superficial surgical site infection (SSI). Other significant predictors were deep SSI, organ space SSI, wound disruption, pneumonia, unplanned intubation, mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and sepsis, the investigators said (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.018]).

Of the patients included in the study, 1,819 had a laparoscopic gastric band, 9,613 had laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 6,439 had gastroplasties, and 315 had open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. All had a BMI of at least 30 kg/m2, and had a postsurgery length of stay of 14 days or fewer. Most were ASA risk class 3 or lower, and most were functionally independent.

Complications were more common with laparoscopic and open Roux-en-y gastric bypass (5.5% and 11.8%, respectively) rather than with gastroplasty and sleeve (3.4%) and laparoscopic banding (1.4%).

The findings are of value, because while bariatric surgery is a low-risk procedure, and it is extremely common; in 2013 there were 179,000 such surgeries performed in the United States.

“Bariatric surgery is one of the fastest-growing surgical interest areas, making analysis of patient outcomes and reasons for readmission important,” the investigators explained.

The ability to identify high-risk patients could allow for targeted interventions to prevent readmission, they said.

For example, steroid use, which was identified as a risk factor in the current study, is modifiable.

“In our practice, steroids are discontinued for 6 weeks prior to bariatric surgery and patients who are steroid dependent are unlikely to undergo bariatric surgery,” they said.

Additionally, they “try to minimize readmission for patients with infections by treating with antibiotics following operation and continuing antibiotics at discharge.”

The investigators noted that the ACS NSQIP MORBPROB (estimated probability of morbidity) tool is a good tool for predicting readmission among prospective bariatric patients, although it may not fully capture the effect of preexisting conditions.

“These data led us to change our own practice by risk-stratifying patients with higher ASA and BMI to consider surgical options, and to begin early surveillance soon after discharge,” they said.

The authors reported having no disclosures.

Bariatric surgery is generally safe and readmissions are rare, but prolonged operative time, operation complexity, and major postoperative complications are among several risk factors for readmission identified in a large retrospective cohort.

Of 18,186 patients from the 2012 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement program (ACS NSQIP) database who had bariatric surgery as a primary procedure, 5% were readmitted. Of 815 patients with any major complication, 31% were readmitted. Factors found on multivariate analysis to significantly predict readmission within 30 days were age, sex, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) risk class, diabetes status, hypertension, and steroid use, Dr. Christa R. Abraham of Albany (N.Y.) Medical College and her colleagues reported online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Further, all major postoperative complications were significant predictors of readmission, including bleeding requiring transfusion, urinary tract infections, and superficial surgical site infection (SSI). Other significant predictors were deep SSI, organ space SSI, wound disruption, pneumonia, unplanned intubation, mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and sepsis, the investigators said (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.018]).

Of the patients included in the study, 1,819 had a laparoscopic gastric band, 9,613 had laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 6,439 had gastroplasties, and 315 had open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. All had a BMI of at least 30 kg/m2, and had a postsurgery length of stay of 14 days or fewer. Most were ASA risk class 3 or lower, and most were functionally independent.

Complications were more common with laparoscopic and open Roux-en-y gastric bypass (5.5% and 11.8%, respectively) rather than with gastroplasty and sleeve (3.4%) and laparoscopic banding (1.4%).

The findings are of value, because while bariatric surgery is a low-risk procedure, and it is extremely common; in 2013 there were 179,000 such surgeries performed in the United States.

“Bariatric surgery is one of the fastest-growing surgical interest areas, making analysis of patient outcomes and reasons for readmission important,” the investigators explained.

The ability to identify high-risk patients could allow for targeted interventions to prevent readmission, they said.

For example, steroid use, which was identified as a risk factor in the current study, is modifiable.

“In our practice, steroids are discontinued for 6 weeks prior to bariatric surgery and patients who are steroid dependent are unlikely to undergo bariatric surgery,” they said.

Additionally, they “try to minimize readmission for patients with infections by treating with antibiotics following operation and continuing antibiotics at discharge.”

The investigators noted that the ACS NSQIP MORBPROB (estimated probability of morbidity) tool is a good tool for predicting readmission among prospective bariatric patients, although it may not fully capture the effect of preexisting conditions.

“These data led us to change our own practice by risk-stratifying patients with higher ASA and BMI to consider surgical options, and to begin early surveillance soon after discharge,” they said.

The authors reported having no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point: Knowing risk factors for readmission after bariatric surgery can allow for targeted interventions.

Major finding: Steroid use is among several risk factors for readmission following bariatric surgery (incidence rate ratio, 2.07)

Data source: A retrospective cohort study involving 18,186 patients.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no disclosures.

Huntington’s Disease: Emerging Concepts in Diagnosis and Treatment

Trading in work-life balance for a well-balanced life

My residency supervisor candidly asked me today – Isn’t stressing out about writing an article on work-life balance kind of missing the point? Well, yeah, that’s why she’s my supervisor. This brings me to one of the lesser advertised tips to avoiding burnout, which is: Get yourself a great mensch. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. The plan was to have 10 perfectly delineated rules, because if it worked for Letterman and Moses, it should work for residency. More to come on that.

Another part of the plan was to have this article finished by last weekend, but long call was Saturday. This was followed by long call recovery consisting of sleeping in so late my dad texted and left a voicemail asking, what happened? I haven’t heard from you all weekend. Then there was the obligatory run on the treadmill so the gooey cinnamon rolls the nurses baked and generously invited me to on Thursday would not stick around long enough for my husband to wonder if this was the beginning of me letting myself go. Isn’t that a lovely phrase?

Monday was Monday. How does anyone get anything done on Mondays? I had a new team, two new patients to learn and discharge. Plus, it was the first day that cracked 50 degrees in 5 months. I had to meet up with a friend, grab some coffee, and gossip walk around the lake. This was before we found out another friend was being slammed with consults in the emergency room. So there I was right back at the hospital Monday night with a cream cheese cherry pastry to cheer up my compatriot in the struggle.

This brings me to Tuesday. I had planned to be at the editing stage of this article on Tuesday. But didactics ran long due to everyone being so engaged in our formulations lecture, I didn’t have a shot at looking at this thing until lunchtime. Lunchtime came, and as I opened Microsoft Word among my dollar turkey sandwich and mini Purell bottles stationed around me like glorious little sergeants, I heard the gingerly utterings of a medical student: Um, if you have a moment, could you tell me the difference between the side-effect profile of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics?

An hour later, I was informed that an admit was on the way and was traveling from out of state, set to arrive a half-hour before shift’s end. Did I mention he arrived with two family members in tow who wanted to talk about how things went wrong starting 20 years ago? Then there was the patient to see who I knew would pout if I didn’t spend at least a half-hour checking in. You know, the one the nurses always try to save me from even though I secretly never wanted to be saved.

I finally drove home 2 hours later than anticipated with a smile on my face. I should repeat that, WITH A SMILE ON MY FACE. I felt good because I’d done good. After all, there’s even a little sunlight left. When I walk in the front door, I kiss my husband and then immediately delve into a new story from the day. We laugh. We warm up leftovers, sit on the couch with our bare feet on the table, and catch an hour of American Idol (talent never gets old). Then it’s time to meet this maker.

The strange thing is, the person who began this column with all of her well-intentioned plans feels very different from the person who has made it to the deadline. There is a whole life lived in between. All of the readings I had done, notations I had made, seem kind of beside the point. I could pepper you with statistics and evidence-based outcomes warning of divorce, substance abuse, physician suicide, patient errors, and the like, which are all very real outcomes of poorly balanced lives. But I think we know all of that. It’s the in between space, the living part where so many of us lose our way. So instead of referenced journals, I offer you my journey. Because I can truly say that for the last 3 months of the most difficult year of residency, I have been happy. May this piece be also with you.

Dr. Schmidt, a second-year psychiatry resident at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., is interested in psychodynamic therapy and in pursuing a fellowship in addictions. After obtaining a bachelor of arts at the University of California, Berkeley, she earned a master of arts degree in philosophy and humanities at the University of Chicago. She attended medical school at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria.

My residency supervisor candidly asked me today – Isn’t stressing out about writing an article on work-life balance kind of missing the point? Well, yeah, that’s why she’s my supervisor. This brings me to one of the lesser advertised tips to avoiding burnout, which is: Get yourself a great mensch. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. The plan was to have 10 perfectly delineated rules, because if it worked for Letterman and Moses, it should work for residency. More to come on that.

Another part of the plan was to have this article finished by last weekend, but long call was Saturday. This was followed by long call recovery consisting of sleeping in so late my dad texted and left a voicemail asking, what happened? I haven’t heard from you all weekend. Then there was the obligatory run on the treadmill so the gooey cinnamon rolls the nurses baked and generously invited me to on Thursday would not stick around long enough for my husband to wonder if this was the beginning of me letting myself go. Isn’t that a lovely phrase?

Monday was Monday. How does anyone get anything done on Mondays? I had a new team, two new patients to learn and discharge. Plus, it was the first day that cracked 50 degrees in 5 months. I had to meet up with a friend, grab some coffee, and gossip walk around the lake. This was before we found out another friend was being slammed with consults in the emergency room. So there I was right back at the hospital Monday night with a cream cheese cherry pastry to cheer up my compatriot in the struggle.

This brings me to Tuesday. I had planned to be at the editing stage of this article on Tuesday. But didactics ran long due to everyone being so engaged in our formulations lecture, I didn’t have a shot at looking at this thing until lunchtime. Lunchtime came, and as I opened Microsoft Word among my dollar turkey sandwich and mini Purell bottles stationed around me like glorious little sergeants, I heard the gingerly utterings of a medical student: Um, if you have a moment, could you tell me the difference between the side-effect profile of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics?

An hour later, I was informed that an admit was on the way and was traveling from out of state, set to arrive a half-hour before shift’s end. Did I mention he arrived with two family members in tow who wanted to talk about how things went wrong starting 20 years ago? Then there was the patient to see who I knew would pout if I didn’t spend at least a half-hour checking in. You know, the one the nurses always try to save me from even though I secretly never wanted to be saved.

I finally drove home 2 hours later than anticipated with a smile on my face. I should repeat that, WITH A SMILE ON MY FACE. I felt good because I’d done good. After all, there’s even a little sunlight left. When I walk in the front door, I kiss my husband and then immediately delve into a new story from the day. We laugh. We warm up leftovers, sit on the couch with our bare feet on the table, and catch an hour of American Idol (talent never gets old). Then it’s time to meet this maker.

The strange thing is, the person who began this column with all of her well-intentioned plans feels very different from the person who has made it to the deadline. There is a whole life lived in between. All of the readings I had done, notations I had made, seem kind of beside the point. I could pepper you with statistics and evidence-based outcomes warning of divorce, substance abuse, physician suicide, patient errors, and the like, which are all very real outcomes of poorly balanced lives. But I think we know all of that. It’s the in between space, the living part where so many of us lose our way. So instead of referenced journals, I offer you my journey. Because I can truly say that for the last 3 months of the most difficult year of residency, I have been happy. May this piece be also with you.