User login

Pathway appears critical to HSC aging

in the bone marrow

Scientists say they’ve identified a molecular pathway that is critical to hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) aging and can be manipulated to rejuvenate blood.

The researchers found that HSCs’ ability to repair damage caused by inappropriate protein folding in the mitochondria is essential for the cells’ survival and regenerative capacity.

The discovery has implications for research on reversing the signs of aging, a process thought to be caused by increased cellular stress and damage.

“Ultimately, a cell dies when it can’t deal well with stress,” said study author Danica Chen, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley.

“We found that by slowing down the activity of mitochondria in the blood stem cells of mice, we were able to enhance their capacity to handle stress and rejuvenate old blood. This confirms the significance of this pathway in the aging process.”

Mitochondria host a multitude of proteins that must be folded properly to function correctly. When the folding goes awry, the mitochondrial unfolded-protein response (UPRmt) kicks in to boost the production of specific proteins to fix or remove the misfolded protein.

There has been little research on the UPRmt pathway, but studies in roundworms suggest its activity increases when there is a burst of mitochondrial growth.

Dr Chen and her colleagues noted that adult stem cells are normally in a quiescent state with little mitochondrial activity. They are activated only when needed to replenish tissue.

At that time, the mitochondrial activity increases, and stem cells proliferate and differentiate. When protein-folding problems occur, this fast growth could lead to more harm.

Dr Chen’s lab stumbled upon the importance of UPRmt in HSC aging while studying sirtuins, a class of proteins recognized as stress-resistance regulators.

The researchers noticed that levels of one particular sirtuin, SIRT7, increase as a way to help cells cope with stress from misfolded proteins in the mitochondria. But SIRT7 levels decline with age.

“We isolated blood stem cells from aged mice and found that when we increased the levels of SIRT7, we were able to reduce mitochondrial protein-folding stress,” Dr Chen said. “We then transplanted the blood stem cells back into mice, and SIRT7 improved the blood stem cells’ regenerative capacity.”

The researchers also found that HSCs deficient in SIRT7 proliferate more. This faster growth is due to increased protein production and increased activity of the mitochondria, and slowing things down appears to be a critical step in giving cells time to recover from stress.

Dr Chen likened this to an auto accident or stalled car stopping traffic on a freeway.

“When there’s a mitochondrial protein-folding problem, there is a traffic jam in the mitochondria,” she said. “If you prevent more proteins from being created and added to the mitochondria, you are helping to reduce the jam.”

Until this study, it was unclear which stress signals regulate HSCs’ transition to and from the quiescent state and how that related to tissue regeneration during aging.

“Identifying the role of this mitochondrial pathway in blood stem cells gives us a new target for controlling the aging process,” Dr Chen said.

She and her colleagues described this work in Science. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Scientists say they’ve identified a molecular pathway that is critical to hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) aging and can be manipulated to rejuvenate blood.

The researchers found that HSCs’ ability to repair damage caused by inappropriate protein folding in the mitochondria is essential for the cells’ survival and regenerative capacity.

The discovery has implications for research on reversing the signs of aging, a process thought to be caused by increased cellular stress and damage.

“Ultimately, a cell dies when it can’t deal well with stress,” said study author Danica Chen, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley.

“We found that by slowing down the activity of mitochondria in the blood stem cells of mice, we were able to enhance their capacity to handle stress and rejuvenate old blood. This confirms the significance of this pathway in the aging process.”

Mitochondria host a multitude of proteins that must be folded properly to function correctly. When the folding goes awry, the mitochondrial unfolded-protein response (UPRmt) kicks in to boost the production of specific proteins to fix or remove the misfolded protein.

There has been little research on the UPRmt pathway, but studies in roundworms suggest its activity increases when there is a burst of mitochondrial growth.

Dr Chen and her colleagues noted that adult stem cells are normally in a quiescent state with little mitochondrial activity. They are activated only when needed to replenish tissue.

At that time, the mitochondrial activity increases, and stem cells proliferate and differentiate. When protein-folding problems occur, this fast growth could lead to more harm.

Dr Chen’s lab stumbled upon the importance of UPRmt in HSC aging while studying sirtuins, a class of proteins recognized as stress-resistance regulators.

The researchers noticed that levels of one particular sirtuin, SIRT7, increase as a way to help cells cope with stress from misfolded proteins in the mitochondria. But SIRT7 levels decline with age.

“We isolated blood stem cells from aged mice and found that when we increased the levels of SIRT7, we were able to reduce mitochondrial protein-folding stress,” Dr Chen said. “We then transplanted the blood stem cells back into mice, and SIRT7 improved the blood stem cells’ regenerative capacity.”

The researchers also found that HSCs deficient in SIRT7 proliferate more. This faster growth is due to increased protein production and increased activity of the mitochondria, and slowing things down appears to be a critical step in giving cells time to recover from stress.

Dr Chen likened this to an auto accident or stalled car stopping traffic on a freeway.

“When there’s a mitochondrial protein-folding problem, there is a traffic jam in the mitochondria,” she said. “If you prevent more proteins from being created and added to the mitochondria, you are helping to reduce the jam.”

Until this study, it was unclear which stress signals regulate HSCs’ transition to and from the quiescent state and how that related to tissue regeneration during aging.

“Identifying the role of this mitochondrial pathway in blood stem cells gives us a new target for controlling the aging process,” Dr Chen said.

She and her colleagues described this work in Science. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Scientists say they’ve identified a molecular pathway that is critical to hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) aging and can be manipulated to rejuvenate blood.

The researchers found that HSCs’ ability to repair damage caused by inappropriate protein folding in the mitochondria is essential for the cells’ survival and regenerative capacity.

The discovery has implications for research on reversing the signs of aging, a process thought to be caused by increased cellular stress and damage.

“Ultimately, a cell dies when it can’t deal well with stress,” said study author Danica Chen, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley.

“We found that by slowing down the activity of mitochondria in the blood stem cells of mice, we were able to enhance their capacity to handle stress and rejuvenate old blood. This confirms the significance of this pathway in the aging process.”

Mitochondria host a multitude of proteins that must be folded properly to function correctly. When the folding goes awry, the mitochondrial unfolded-protein response (UPRmt) kicks in to boost the production of specific proteins to fix or remove the misfolded protein.

There has been little research on the UPRmt pathway, but studies in roundworms suggest its activity increases when there is a burst of mitochondrial growth.

Dr Chen and her colleagues noted that adult stem cells are normally in a quiescent state with little mitochondrial activity. They are activated only when needed to replenish tissue.

At that time, the mitochondrial activity increases, and stem cells proliferate and differentiate. When protein-folding problems occur, this fast growth could lead to more harm.

Dr Chen’s lab stumbled upon the importance of UPRmt in HSC aging while studying sirtuins, a class of proteins recognized as stress-resistance regulators.

The researchers noticed that levels of one particular sirtuin, SIRT7, increase as a way to help cells cope with stress from misfolded proteins in the mitochondria. But SIRT7 levels decline with age.

“We isolated blood stem cells from aged mice and found that when we increased the levels of SIRT7, we were able to reduce mitochondrial protein-folding stress,” Dr Chen said. “We then transplanted the blood stem cells back into mice, and SIRT7 improved the blood stem cells’ regenerative capacity.”

The researchers also found that HSCs deficient in SIRT7 proliferate more. This faster growth is due to increased protein production and increased activity of the mitochondria, and slowing things down appears to be a critical step in giving cells time to recover from stress.

Dr Chen likened this to an auto accident or stalled car stopping traffic on a freeway.

“When there’s a mitochondrial protein-folding problem, there is a traffic jam in the mitochondria,” she said. “If you prevent more proteins from being created and added to the mitochondria, you are helping to reduce the jam.”

Until this study, it was unclear which stress signals regulate HSCs’ transition to and from the quiescent state and how that related to tissue regeneration during aging.

“Identifying the role of this mitochondrial pathway in blood stem cells gives us a new target for controlling the aging process,” Dr Chen said.

She and her colleagues described this work in Science. ![]()

Predicting pregnancy complications in SCD patients

Photo by Nina Matthews

Results of a new analysis may help physicians predict the likelihood of complications in pregnant women with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The research showed that pregnant women with SCD had an increased risk of stillbirth, pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, having infants who were born small for their gestational age, and other adverse outcomes.

Women with severe SCD, but not those with milder SCD, had a substantially higher risk of mortality than their healthy peers.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“While we know that women with sickle cell disease will have high-risk pregnancies, we have lacked the evidence that would allow us to confidently tell these patients how likely they are to experience one complication over another,” said study author Eugene Oteng-Ntim, MD, of the Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, England.

“This reality makes it difficult for us as care providers to properly counsel our sickle cell patients considering pregnancy.”

To better estimate pregnancy-related complications in women with SCD, Dr Oteng-Ntim and his colleagues examined 21 published observational studies.

The team analyzed data on 26,349 pregnant women with SCD and 26,151,746 pregnant women who shared attributes with the SCD population, such as ethnicity or location, but were otherwise healthy.

The researchers classified the SCD population based on genotype, including 1276 women with the classic form (HbSS genotype), 279 with a milder form (HbSC genotype), and 24,794 whose disease genotype was unreported (non-specified SCD).

Thirteen of the studies originated from high-income countries ($30,000 income per capita or greater), and the remaining were from low- to median-income countries.

Compared to women without SCD, patients with HbSS genotype had an increased risk of death, with a risk ratio (RR) of 5.98. Women with non-specified SCD had an increased risk of death as well, with an RR of 18.51. There was only 1 death among women who were known to have HbSC SCD.

There was an increased risk of stillbirth among women with SCD, compared to those without the disease. The RRs were 3.94 for HbSS disease, 1.78 for HbSC disease, and 3.49 for non-specified SCD.

The researchers found a significantly lower risk of maternal mortality (odds ratio [OR]=0.15) and stillbirth (OR=0.28) in SCD patients from countries with a gross national income of $30,000 or greater. But income had no significant impact on pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, or infants being small for their gestational age.

Women with all types of SCD had an increase in the risk of pre-eclampsia, compared to healthy women. The RRs were 2.43 for HbSS disease, 2.03 for HbSC disease, and 2.06 for non-specified SCD.

Women with SCD also had an increased risk of preterm delivery. The RRs were 2.21 for HbSS disease, 1.45 for HbSC disease, and 1.59 for non-specified SCD.

And women with SCD were more likely to have infants who were born small for their gestational age. The RRs were 3.72 for HbSS disease, 1.98 for HbSC disease, and 2.23 for non-specified SCD.

Analyses revealed that genotype (HbSS vs HbSC) had a significant impact on stillbirth, preterm delivery, and small infants, but it did not appear to impact the risk of pre-eclampsia.

The researchers said this study provides useful estimates of the morbidity and mortality associated with SCD in pregnancy.

“By improving care providers’ ability to more accurately predict adverse outcomes, this analysis is a first step toward improving universal care for all who suffer from this disease,” Dr Oteng-Ntim concluded. ![]()

Photo by Nina Matthews

Results of a new analysis may help physicians predict the likelihood of complications in pregnant women with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The research showed that pregnant women with SCD had an increased risk of stillbirth, pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, having infants who were born small for their gestational age, and other adverse outcomes.

Women with severe SCD, but not those with milder SCD, had a substantially higher risk of mortality than their healthy peers.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“While we know that women with sickle cell disease will have high-risk pregnancies, we have lacked the evidence that would allow us to confidently tell these patients how likely they are to experience one complication over another,” said study author Eugene Oteng-Ntim, MD, of the Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, England.

“This reality makes it difficult for us as care providers to properly counsel our sickle cell patients considering pregnancy.”

To better estimate pregnancy-related complications in women with SCD, Dr Oteng-Ntim and his colleagues examined 21 published observational studies.

The team analyzed data on 26,349 pregnant women with SCD and 26,151,746 pregnant women who shared attributes with the SCD population, such as ethnicity or location, but were otherwise healthy.

The researchers classified the SCD population based on genotype, including 1276 women with the classic form (HbSS genotype), 279 with a milder form (HbSC genotype), and 24,794 whose disease genotype was unreported (non-specified SCD).

Thirteen of the studies originated from high-income countries ($30,000 income per capita or greater), and the remaining were from low- to median-income countries.

Compared to women without SCD, patients with HbSS genotype had an increased risk of death, with a risk ratio (RR) of 5.98. Women with non-specified SCD had an increased risk of death as well, with an RR of 18.51. There was only 1 death among women who were known to have HbSC SCD.

There was an increased risk of stillbirth among women with SCD, compared to those without the disease. The RRs were 3.94 for HbSS disease, 1.78 for HbSC disease, and 3.49 for non-specified SCD.

The researchers found a significantly lower risk of maternal mortality (odds ratio [OR]=0.15) and stillbirth (OR=0.28) in SCD patients from countries with a gross national income of $30,000 or greater. But income had no significant impact on pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, or infants being small for their gestational age.

Women with all types of SCD had an increase in the risk of pre-eclampsia, compared to healthy women. The RRs were 2.43 for HbSS disease, 2.03 for HbSC disease, and 2.06 for non-specified SCD.

Women with SCD also had an increased risk of preterm delivery. The RRs were 2.21 for HbSS disease, 1.45 for HbSC disease, and 1.59 for non-specified SCD.

And women with SCD were more likely to have infants who were born small for their gestational age. The RRs were 3.72 for HbSS disease, 1.98 for HbSC disease, and 2.23 for non-specified SCD.

Analyses revealed that genotype (HbSS vs HbSC) had a significant impact on stillbirth, preterm delivery, and small infants, but it did not appear to impact the risk of pre-eclampsia.

The researchers said this study provides useful estimates of the morbidity and mortality associated with SCD in pregnancy.

“By improving care providers’ ability to more accurately predict adverse outcomes, this analysis is a first step toward improving universal care for all who suffer from this disease,” Dr Oteng-Ntim concluded. ![]()

Photo by Nina Matthews

Results of a new analysis may help physicians predict the likelihood of complications in pregnant women with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The research showed that pregnant women with SCD had an increased risk of stillbirth, pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, having infants who were born small for their gestational age, and other adverse outcomes.

Women with severe SCD, but not those with milder SCD, had a substantially higher risk of mortality than their healthy peers.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“While we know that women with sickle cell disease will have high-risk pregnancies, we have lacked the evidence that would allow us to confidently tell these patients how likely they are to experience one complication over another,” said study author Eugene Oteng-Ntim, MD, of the Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, England.

“This reality makes it difficult for us as care providers to properly counsel our sickle cell patients considering pregnancy.”

To better estimate pregnancy-related complications in women with SCD, Dr Oteng-Ntim and his colleagues examined 21 published observational studies.

The team analyzed data on 26,349 pregnant women with SCD and 26,151,746 pregnant women who shared attributes with the SCD population, such as ethnicity or location, but were otherwise healthy.

The researchers classified the SCD population based on genotype, including 1276 women with the classic form (HbSS genotype), 279 with a milder form (HbSC genotype), and 24,794 whose disease genotype was unreported (non-specified SCD).

Thirteen of the studies originated from high-income countries ($30,000 income per capita or greater), and the remaining were from low- to median-income countries.

Compared to women without SCD, patients with HbSS genotype had an increased risk of death, with a risk ratio (RR) of 5.98. Women with non-specified SCD had an increased risk of death as well, with an RR of 18.51. There was only 1 death among women who were known to have HbSC SCD.

There was an increased risk of stillbirth among women with SCD, compared to those without the disease. The RRs were 3.94 for HbSS disease, 1.78 for HbSC disease, and 3.49 for non-specified SCD.

The researchers found a significantly lower risk of maternal mortality (odds ratio [OR]=0.15) and stillbirth (OR=0.28) in SCD patients from countries with a gross national income of $30,000 or greater. But income had no significant impact on pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, or infants being small for their gestational age.

Women with all types of SCD had an increase in the risk of pre-eclampsia, compared to healthy women. The RRs were 2.43 for HbSS disease, 2.03 for HbSC disease, and 2.06 for non-specified SCD.

Women with SCD also had an increased risk of preterm delivery. The RRs were 2.21 for HbSS disease, 1.45 for HbSC disease, and 1.59 for non-specified SCD.

And women with SCD were more likely to have infants who were born small for their gestational age. The RRs were 3.72 for HbSS disease, 1.98 for HbSC disease, and 2.23 for non-specified SCD.

Analyses revealed that genotype (HbSS vs HbSC) had a significant impact on stillbirth, preterm delivery, and small infants, but it did not appear to impact the risk of pre-eclampsia.

The researchers said this study provides useful estimates of the morbidity and mortality associated with SCD in pregnancy.

“By improving care providers’ ability to more accurately predict adverse outcomes, this analysis is a first step toward improving universal care for all who suffer from this disease,” Dr Oteng-Ntim concluded. ![]()

Drug granted orphan designation for GVHD

The European Commission has granted orphan drug designation for intravenous (IV) alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) to treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

AAT is a protein derived from human plasma that has demonstrated immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, tissue-protective, antimicrobial, and anti-apoptotic properties.

AAT may attenuate inflammation by lowering levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, and proteases associated with GVHD.

The European Commission granted IV AAT orphan designation based on preliminary clinical and preclinical research.

Orphan designation is granted to a medicine intended to treat a rare condition occurring in not more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union. The designation allows the drug’s maker to benefit from incentives such as a 10-year period of market exclusivity, reduced regulatory fees, and protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency.

IV AAT also has orphan designation to treat GVHD in the US.

Studies of AAT

AAT is being investigated in a phase 1/2 study involving 24 patients with GVHD who had an inadequate response to steroid treatment. The patients are enrolled in 4 dose cohorts, in which they receive up to 8 doses of AAT.

Interim results from this study were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3927). Preliminary results indicated that continuous administration of AAT as therapy for steroid-resistant gut GVHD is feasible in the subject population.

Following AAT administration, the researchers observed a decrease in diarrhea, a decrease in intestinal AAT loss, and improvement in endoscopic evaluation. In addition, AAT administration suppressed serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and interfered with GVHD biomarkers.

Investigators have also published research on AAT in Blood. This study suggested that AAT has a protective effect against GVHD and enhances graft-vs-leukemia effects.

Kamada Ltd., the company developing IV AAT, plans to begin a phase 3 trial of the treatment in 2016 and get the product to market in 2019 or later. ![]()

The European Commission has granted orphan drug designation for intravenous (IV) alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) to treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

AAT is a protein derived from human plasma that has demonstrated immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, tissue-protective, antimicrobial, and anti-apoptotic properties.

AAT may attenuate inflammation by lowering levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, and proteases associated with GVHD.

The European Commission granted IV AAT orphan designation based on preliminary clinical and preclinical research.

Orphan designation is granted to a medicine intended to treat a rare condition occurring in not more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union. The designation allows the drug’s maker to benefit from incentives such as a 10-year period of market exclusivity, reduced regulatory fees, and protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency.

IV AAT also has orphan designation to treat GVHD in the US.

Studies of AAT

AAT is being investigated in a phase 1/2 study involving 24 patients with GVHD who had an inadequate response to steroid treatment. The patients are enrolled in 4 dose cohorts, in which they receive up to 8 doses of AAT.

Interim results from this study were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3927). Preliminary results indicated that continuous administration of AAT as therapy for steroid-resistant gut GVHD is feasible in the subject population.

Following AAT administration, the researchers observed a decrease in diarrhea, a decrease in intestinal AAT loss, and improvement in endoscopic evaluation. In addition, AAT administration suppressed serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and interfered with GVHD biomarkers.

Investigators have also published research on AAT in Blood. This study suggested that AAT has a protective effect against GVHD and enhances graft-vs-leukemia effects.

Kamada Ltd., the company developing IV AAT, plans to begin a phase 3 trial of the treatment in 2016 and get the product to market in 2019 or later. ![]()

The European Commission has granted orphan drug designation for intravenous (IV) alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) to treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

AAT is a protein derived from human plasma that has demonstrated immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, tissue-protective, antimicrobial, and anti-apoptotic properties.

AAT may attenuate inflammation by lowering levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, and proteases associated with GVHD.

The European Commission granted IV AAT orphan designation based on preliminary clinical and preclinical research.

Orphan designation is granted to a medicine intended to treat a rare condition occurring in not more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union. The designation allows the drug’s maker to benefit from incentives such as a 10-year period of market exclusivity, reduced regulatory fees, and protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency.

IV AAT also has orphan designation to treat GVHD in the US.

Studies of AAT

AAT is being investigated in a phase 1/2 study involving 24 patients with GVHD who had an inadequate response to steroid treatment. The patients are enrolled in 4 dose cohorts, in which they receive up to 8 doses of AAT.

Interim results from this study were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3927). Preliminary results indicated that continuous administration of AAT as therapy for steroid-resistant gut GVHD is feasible in the subject population.

Following AAT administration, the researchers observed a decrease in diarrhea, a decrease in intestinal AAT loss, and improvement in endoscopic evaluation. In addition, AAT administration suppressed serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and interfered with GVHD biomarkers.

Investigators have also published research on AAT in Blood. This study suggested that AAT has a protective effect against GVHD and enhances graft-vs-leukemia effects.

Kamada Ltd., the company developing IV AAT, plans to begin a phase 3 trial of the treatment in 2016 and get the product to market in 2019 or later. ![]()

Team advocates liver MRI to measure iron

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be the gold standard for measuring liver iron concentration (LIC) in patients receiving ongoing transfusion therapy, according to a group of researchers.

The team found evidence suggesting that liver MRI is more accurate than liver biopsy in determining total body iron balance in patients with sickle cell disease and other disorders requiring regular blood transfusions.

The findings have been published in Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

“Measuring total body iron using MRI is safer and less painful than biopsy,” said study author John Wood, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“In this study, we’ve demonstrated that it is also more accurate. MRI should be recognized as the new gold standard for determining iron accumulation in the body.”

Dr Wood and his colleagues came to this conclusion after analyzing data from 49 patients who were undergoing treatment with deferitazole, an experimental chelating agent.

The team looked at the amount of iron the patients were receiving by transfusion and the amount of chelating agent they consumed, providing insights into the expected changes in iron levels at 12, 24, and 48 weeks after the start of deferitazole.

To compare MRI and liver biopsy, the researchers used serial estimates of iron chelation efficiency (ICE) calculated by R2 and R2* MRI LIC estimates as well as by simulated liver biopsy (over all physically reasonable sampling variability).

The estimates suggested that MRI liver iron measurements (R2 and R2*) are more accurate than a physically realizable liver biopsy (which has a sampling error of 10% or higher).

For R2, the standard deviation of ICE was 44.8% at 12 weeks, 14.8% at 24 weeks, and 7.4% at 48 weeks. For R2*, the standard deviation was 22.9% at 12 weeks, 9.3% at 24 weeks, and 5.7% at 48 weeks.

For a biopsy with a sampling error of 0%, the standard deviation of ICE was 25.9% at 12 weeks, 12.8% at 24 weeks, and 6.7% at 48 weeks. For a biopsy with a sampling error of 10%, it was 32.8%, 16.5%, and 8.7%, respectively.

For a biopsy with a sampling error of 20%, the standard deviation of ICE was 49.1% at 12 weeks, 24.9% at 24 weeks, and 13% at 48 weeks. For a biopsy with a sampling error of 30%, it was 68.1%, 34.5%, and 18%, respectively. And for a biopsy with a sampling error of 40%, it was 88.1%, 44.6%, and 23.2%, respectively.

In practice, the accuracy of MRI compared to liver biopsy is likely even greater than these estimates suggest, Dr Wood said. ![]()

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be the gold standard for measuring liver iron concentration (LIC) in patients receiving ongoing transfusion therapy, according to a group of researchers.

The team found evidence suggesting that liver MRI is more accurate than liver biopsy in determining total body iron balance in patients with sickle cell disease and other disorders requiring regular blood transfusions.

The findings have been published in Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

“Measuring total body iron using MRI is safer and less painful than biopsy,” said study author John Wood, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“In this study, we’ve demonstrated that it is also more accurate. MRI should be recognized as the new gold standard for determining iron accumulation in the body.”

Dr Wood and his colleagues came to this conclusion after analyzing data from 49 patients who were undergoing treatment with deferitazole, an experimental chelating agent.

The team looked at the amount of iron the patients were receiving by transfusion and the amount of chelating agent they consumed, providing insights into the expected changes in iron levels at 12, 24, and 48 weeks after the start of deferitazole.

To compare MRI and liver biopsy, the researchers used serial estimates of iron chelation efficiency (ICE) calculated by R2 and R2* MRI LIC estimates as well as by simulated liver biopsy (over all physically reasonable sampling variability).

The estimates suggested that MRI liver iron measurements (R2 and R2*) are more accurate than a physically realizable liver biopsy (which has a sampling error of 10% or higher).

For R2, the standard deviation of ICE was 44.8% at 12 weeks, 14.8% at 24 weeks, and 7.4% at 48 weeks. For R2*, the standard deviation was 22.9% at 12 weeks, 9.3% at 24 weeks, and 5.7% at 48 weeks.

For a biopsy with a sampling error of 0%, the standard deviation of ICE was 25.9% at 12 weeks, 12.8% at 24 weeks, and 6.7% at 48 weeks. For a biopsy with a sampling error of 10%, it was 32.8%, 16.5%, and 8.7%, respectively.

For a biopsy with a sampling error of 20%, the standard deviation of ICE was 49.1% at 12 weeks, 24.9% at 24 weeks, and 13% at 48 weeks. For a biopsy with a sampling error of 30%, it was 68.1%, 34.5%, and 18%, respectively. And for a biopsy with a sampling error of 40%, it was 88.1%, 44.6%, and 23.2%, respectively.

In practice, the accuracy of MRI compared to liver biopsy is likely even greater than these estimates suggest, Dr Wood said. ![]()

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be the gold standard for measuring liver iron concentration (LIC) in patients receiving ongoing transfusion therapy, according to a group of researchers.

The team found evidence suggesting that liver MRI is more accurate than liver biopsy in determining total body iron balance in patients with sickle cell disease and other disorders requiring regular blood transfusions.

The findings have been published in Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

“Measuring total body iron using MRI is safer and less painful than biopsy,” said study author John Wood, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“In this study, we’ve demonstrated that it is also more accurate. MRI should be recognized as the new gold standard for determining iron accumulation in the body.”

Dr Wood and his colleagues came to this conclusion after analyzing data from 49 patients who were undergoing treatment with deferitazole, an experimental chelating agent.

The team looked at the amount of iron the patients were receiving by transfusion and the amount of chelating agent they consumed, providing insights into the expected changes in iron levels at 12, 24, and 48 weeks after the start of deferitazole.

To compare MRI and liver biopsy, the researchers used serial estimates of iron chelation efficiency (ICE) calculated by R2 and R2* MRI LIC estimates as well as by simulated liver biopsy (over all physically reasonable sampling variability).

The estimates suggested that MRI liver iron measurements (R2 and R2*) are more accurate than a physically realizable liver biopsy (which has a sampling error of 10% or higher).

For R2, the standard deviation of ICE was 44.8% at 12 weeks, 14.8% at 24 weeks, and 7.4% at 48 weeks. For R2*, the standard deviation was 22.9% at 12 weeks, 9.3% at 24 weeks, and 5.7% at 48 weeks.

For a biopsy with a sampling error of 0%, the standard deviation of ICE was 25.9% at 12 weeks, 12.8% at 24 weeks, and 6.7% at 48 weeks. For a biopsy with a sampling error of 10%, it was 32.8%, 16.5%, and 8.7%, respectively.

For a biopsy with a sampling error of 20%, the standard deviation of ICE was 49.1% at 12 weeks, 24.9% at 24 weeks, and 13% at 48 weeks. For a biopsy with a sampling error of 30%, it was 68.1%, 34.5%, and 18%, respectively. And for a biopsy with a sampling error of 40%, it was 88.1%, 44.6%, and 23.2%, respectively.

In practice, the accuracy of MRI compared to liver biopsy is likely even greater than these estimates suggest, Dr Wood said. ![]()

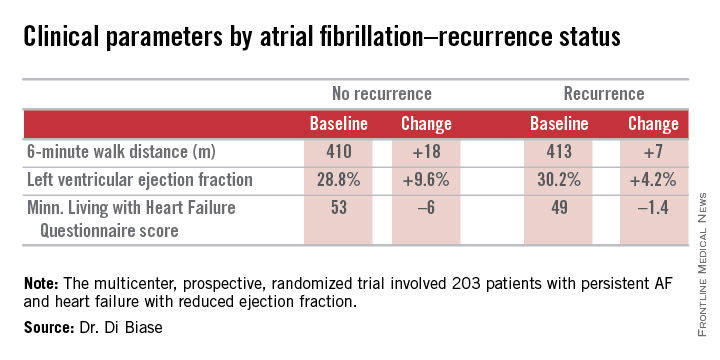

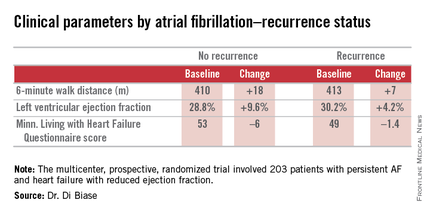

Ablation cuts AF recurrence 2.5-fold vs. amiodarone in heart failure

SAN DIEGO – Catheter ablation proved superior to amiodarone for treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with systolic heart failure in the randomized AATAC-AF trial.

The rate of the primary study endpoint – freedom from recurrent AF through 26 months of prospective follow-up– was 70% in the catheter ablation group, twice the 34% rate with amiodarone, Dr. Luigi Di Biase reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. After covariate adjustment, the investigators found that recurrence was 2.5 times more likely in the patients treated with amiodarone.

But he added a major caveat: pulmonary vein antrum isolation (PVI) alone was no better than the antiarrhythmic drug. The high overall treatment success rate seen with catheter ablation in the trial was achieved by operators who performed PVI plus some additional form of ablation of their own choosing, such as elimination of non–pulmonary vein triggers, ablation of complex fractionated electrograms, and/or additional linear ablation lesions, according to Dr. Di Biase, head of electrophysiology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

AATAC-AF (Ablation versus Amiodarone for Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Congestive Heart Failure and an Implanted ICD/CRTD) was a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial involving 203 patients with persistent AF and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Patients randomized to ablation had to receive PVI at a minimum; operators could perform additional ablation according to their preference. Twenty percent of patients randomized to ablation received PVI alone; 80% underwent additional posterior wall and non–pulmonary vein trigger ablation. The 26-month rate of freedom from recurrence of AF was 36% in patients who received PVI alone and 79% in those who underwent more extensive ablations. A particular strength of the AATAC study was that all participants had an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and/or cardiac resynchronization therapy device, permitting detection of AF with a much higher degree of accuracy than possible in most AF ablation trials.

Any recurrent AF episodes during the first 3 months of follow-up were excluded from the analysis, regardless of whether patients were in the ablation or amiodarone arms, in accord with the 3-month blanking period that’s standard among electrophysiologists. Patients averaged 1.4 ablation sessions during the first 3 months of the trial.

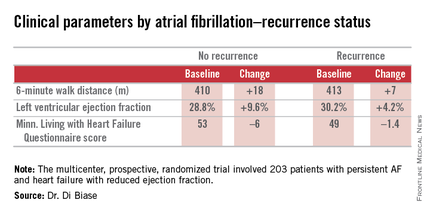

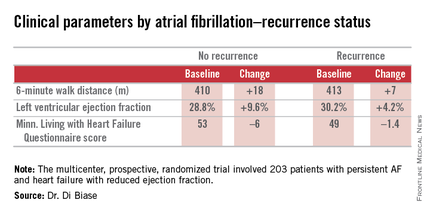

Regardless of treatment, patients in whom AF did not recur showed significantly greater improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction, exercise capacity, and heart failure–related quality of life.

In addition, all-cause mortality during follow-up was significantly lower in the ablation group: 8%, compared with 18% in patients assigned to amiodarone. Moreover, the rate of hospitalization for arrhythmia or worsening heart failure was 31% in the ablation group versus 57% in patients on amiodarone. The economic implications of this sharp reduction in hospitalizations will be the subject of further study, according to Dr. Di Biase.

Also noteworthy was the finding that seven patients had to discontinue amiodarone due to serious side effects: four because of thyroid toxicity, two for pulmonary toxicity, and one owing to hepatic dysfunction, he continued.

Discussant Dr. Richard I. Fogel, current president of the Heart Rhythm Society, commented that “the 70% arrhythmia-free follow-up was a little surprising to me.”

“That seems a little bit high, particularly in a group with persistent atrial fibrillation,” observed Dr. Fogel, who is chief executive officer at St. Vincent Medical Group, Indianapolis.

Dr. Di Biase attributed the high success rate to two factors: One, only highly experienced operators participated in AATAC, and two, most of them weren’t content to stick to PVI alone.

“If you try to do a more extensive procedure addressing non–pulmonary vein triggers in other areas in the left atrium, the success rate is increased by far,” the electrophysiologist said.

As for a possible mechanism for the mortality benefit seen with ablation, “several studies have shown that in a population with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, atrial fibrillation is an independent predictor of mortality,” Dr. Di Biase said. “So I believe that staying in sinus rhythm may have affected the long-term mortality. If you have a treatment that reduces the amount of time in atrial fibrillation, you may reduce mortality.”

While catheter ablation is an increasingly popular treatment strategy in patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal AF, it has been understudied in the setting of AF and comorbid heart failure. These two conditions are commonly coexistent, and they feed on each other in a destructive way: AF worsens heart failure, and heart failure tends to make AF worse.

AATAC was funded by the participating investigators and institutions without external financial support. Dr. Di Biase reported serving as a consultant to Biosense Webster and St. Jude Medical and serving as a paid speaker for Atricure, Biotronik, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Epi EP.

SAN DIEGO – Catheter ablation proved superior to amiodarone for treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with systolic heart failure in the randomized AATAC-AF trial.

The rate of the primary study endpoint – freedom from recurrent AF through 26 months of prospective follow-up– was 70% in the catheter ablation group, twice the 34% rate with amiodarone, Dr. Luigi Di Biase reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. After covariate adjustment, the investigators found that recurrence was 2.5 times more likely in the patients treated with amiodarone.

But he added a major caveat: pulmonary vein antrum isolation (PVI) alone was no better than the antiarrhythmic drug. The high overall treatment success rate seen with catheter ablation in the trial was achieved by operators who performed PVI plus some additional form of ablation of their own choosing, such as elimination of non–pulmonary vein triggers, ablation of complex fractionated electrograms, and/or additional linear ablation lesions, according to Dr. Di Biase, head of electrophysiology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

AATAC-AF (Ablation versus Amiodarone for Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Congestive Heart Failure and an Implanted ICD/CRTD) was a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial involving 203 patients with persistent AF and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Patients randomized to ablation had to receive PVI at a minimum; operators could perform additional ablation according to their preference. Twenty percent of patients randomized to ablation received PVI alone; 80% underwent additional posterior wall and non–pulmonary vein trigger ablation. The 26-month rate of freedom from recurrence of AF was 36% in patients who received PVI alone and 79% in those who underwent more extensive ablations. A particular strength of the AATAC study was that all participants had an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and/or cardiac resynchronization therapy device, permitting detection of AF with a much higher degree of accuracy than possible in most AF ablation trials.

Any recurrent AF episodes during the first 3 months of follow-up were excluded from the analysis, regardless of whether patients were in the ablation or amiodarone arms, in accord with the 3-month blanking period that’s standard among electrophysiologists. Patients averaged 1.4 ablation sessions during the first 3 months of the trial.

Regardless of treatment, patients in whom AF did not recur showed significantly greater improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction, exercise capacity, and heart failure–related quality of life.

In addition, all-cause mortality during follow-up was significantly lower in the ablation group: 8%, compared with 18% in patients assigned to amiodarone. Moreover, the rate of hospitalization for arrhythmia or worsening heart failure was 31% in the ablation group versus 57% in patients on amiodarone. The economic implications of this sharp reduction in hospitalizations will be the subject of further study, according to Dr. Di Biase.

Also noteworthy was the finding that seven patients had to discontinue amiodarone due to serious side effects: four because of thyroid toxicity, two for pulmonary toxicity, and one owing to hepatic dysfunction, he continued.

Discussant Dr. Richard I. Fogel, current president of the Heart Rhythm Society, commented that “the 70% arrhythmia-free follow-up was a little surprising to me.”

“That seems a little bit high, particularly in a group with persistent atrial fibrillation,” observed Dr. Fogel, who is chief executive officer at St. Vincent Medical Group, Indianapolis.

Dr. Di Biase attributed the high success rate to two factors: One, only highly experienced operators participated in AATAC, and two, most of them weren’t content to stick to PVI alone.

“If you try to do a more extensive procedure addressing non–pulmonary vein triggers in other areas in the left atrium, the success rate is increased by far,” the electrophysiologist said.

As for a possible mechanism for the mortality benefit seen with ablation, “several studies have shown that in a population with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, atrial fibrillation is an independent predictor of mortality,” Dr. Di Biase said. “So I believe that staying in sinus rhythm may have affected the long-term mortality. If you have a treatment that reduces the amount of time in atrial fibrillation, you may reduce mortality.”

While catheter ablation is an increasingly popular treatment strategy in patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal AF, it has been understudied in the setting of AF and comorbid heart failure. These two conditions are commonly coexistent, and they feed on each other in a destructive way: AF worsens heart failure, and heart failure tends to make AF worse.

AATAC was funded by the participating investigators and institutions without external financial support. Dr. Di Biase reported serving as a consultant to Biosense Webster and St. Jude Medical and serving as a paid speaker for Atricure, Biotronik, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Epi EP.

SAN DIEGO – Catheter ablation proved superior to amiodarone for treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with systolic heart failure in the randomized AATAC-AF trial.

The rate of the primary study endpoint – freedom from recurrent AF through 26 months of prospective follow-up– was 70% in the catheter ablation group, twice the 34% rate with amiodarone, Dr. Luigi Di Biase reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. After covariate adjustment, the investigators found that recurrence was 2.5 times more likely in the patients treated with amiodarone.

But he added a major caveat: pulmonary vein antrum isolation (PVI) alone was no better than the antiarrhythmic drug. The high overall treatment success rate seen with catheter ablation in the trial was achieved by operators who performed PVI plus some additional form of ablation of their own choosing, such as elimination of non–pulmonary vein triggers, ablation of complex fractionated electrograms, and/or additional linear ablation lesions, according to Dr. Di Biase, head of electrophysiology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

AATAC-AF (Ablation versus Amiodarone for Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Congestive Heart Failure and an Implanted ICD/CRTD) was a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial involving 203 patients with persistent AF and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Patients randomized to ablation had to receive PVI at a minimum; operators could perform additional ablation according to their preference. Twenty percent of patients randomized to ablation received PVI alone; 80% underwent additional posterior wall and non–pulmonary vein trigger ablation. The 26-month rate of freedom from recurrence of AF was 36% in patients who received PVI alone and 79% in those who underwent more extensive ablations. A particular strength of the AATAC study was that all participants had an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and/or cardiac resynchronization therapy device, permitting detection of AF with a much higher degree of accuracy than possible in most AF ablation trials.

Any recurrent AF episodes during the first 3 months of follow-up were excluded from the analysis, regardless of whether patients were in the ablation or amiodarone arms, in accord with the 3-month blanking period that’s standard among electrophysiologists. Patients averaged 1.4 ablation sessions during the first 3 months of the trial.

Regardless of treatment, patients in whom AF did not recur showed significantly greater improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction, exercise capacity, and heart failure–related quality of life.

In addition, all-cause mortality during follow-up was significantly lower in the ablation group: 8%, compared with 18% in patients assigned to amiodarone. Moreover, the rate of hospitalization for arrhythmia or worsening heart failure was 31% in the ablation group versus 57% in patients on amiodarone. The economic implications of this sharp reduction in hospitalizations will be the subject of further study, according to Dr. Di Biase.

Also noteworthy was the finding that seven patients had to discontinue amiodarone due to serious side effects: four because of thyroid toxicity, two for pulmonary toxicity, and one owing to hepatic dysfunction, he continued.

Discussant Dr. Richard I. Fogel, current president of the Heart Rhythm Society, commented that “the 70% arrhythmia-free follow-up was a little surprising to me.”

“That seems a little bit high, particularly in a group with persistent atrial fibrillation,” observed Dr. Fogel, who is chief executive officer at St. Vincent Medical Group, Indianapolis.

Dr. Di Biase attributed the high success rate to two factors: One, only highly experienced operators participated in AATAC, and two, most of them weren’t content to stick to PVI alone.

“If you try to do a more extensive procedure addressing non–pulmonary vein triggers in other areas in the left atrium, the success rate is increased by far,” the electrophysiologist said.

As for a possible mechanism for the mortality benefit seen with ablation, “several studies have shown that in a population with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, atrial fibrillation is an independent predictor of mortality,” Dr. Di Biase said. “So I believe that staying in sinus rhythm may have affected the long-term mortality. If you have a treatment that reduces the amount of time in atrial fibrillation, you may reduce mortality.”

While catheter ablation is an increasingly popular treatment strategy in patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal AF, it has been understudied in the setting of AF and comorbid heart failure. These two conditions are commonly coexistent, and they feed on each other in a destructive way: AF worsens heart failure, and heart failure tends to make AF worse.

AATAC was funded by the participating investigators and institutions without external financial support. Dr. Di Biase reported serving as a consultant to Biosense Webster and St. Jude Medical and serving as a paid speaker for Atricure, Biotronik, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Epi EP.

AT ACC 15

Key clinical point: Catheter ablation is hands down more effective than amiodarone for the treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with systolic heart failure.

Major finding: The rate of freedom from recurrent atrial fibrillation during 26 months of follow-up was 70% in patients randomized to catheter ablation, compared with 34% in those assigned to amiodarone.

Data source: The AATAC-AF study was a multicenter, randomized, prospective clinical trial inc 203 patients.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by the participating investigators and institutions without commercial support. Dr. Di Biase reported serving as a consultant to Biosense Webster and St. Jude Medical and serving as a paid speaker for Atricure, Biotronik, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Epi EP.

Uncompensated hospital care declines by $7 billion

Uncompensated hospital care costs fell by an estimated $7 billion in 2014 because of marketplace coverage and state Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act, according to a March 23 report by the Department of Health & Human Services. State Medicaid expansions accounted for an estimated $5 billion of the reduction, the HHS analysis found.

U.S. hospitals provided $50 billion in uncompensated care in 2013, the report found. Based on estimated coverage gains in 2014, the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) estimates that uncompensated care costs were $7.4 billion lower in 2014 than they would have been had insurance coverage remained at 2013 levels. Hospitals spent an estimated $27 billion in uncompensated care in 2014, compared with an estimated $35 billion at 2013 coverage levels, a 21% reduction in uncompensated care spending. To arrive at the figures, ASPE analyzed uncompensated hospital care levels and cost reports from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, census data, estimates from Gallup-Healthways, and Medicaid enrollment data.

While $5 billion of the reduction came from the 28 states that have expanded Medicaid, $2 billion resulted from the 22 states that have not expanded Medicaid, according to ASPE. The government noted that if the nonexpansion states had increases proportionately as large in Medicaid coverage as did the expansion states, their uncompensated care costs would have declined by an additional $1.4 billion.

March 23 marked the fifth anniversary of President Obama’s signing the ACA into law. In a statement by the White House, the president praised the law’s success, and its impact on patients and the country.

On Twitter @legal_med

Uncompensated hospital care costs fell by an estimated $7 billion in 2014 because of marketplace coverage and state Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act, according to a March 23 report by the Department of Health & Human Services. State Medicaid expansions accounted for an estimated $5 billion of the reduction, the HHS analysis found.

U.S. hospitals provided $50 billion in uncompensated care in 2013, the report found. Based on estimated coverage gains in 2014, the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) estimates that uncompensated care costs were $7.4 billion lower in 2014 than they would have been had insurance coverage remained at 2013 levels. Hospitals spent an estimated $27 billion in uncompensated care in 2014, compared with an estimated $35 billion at 2013 coverage levels, a 21% reduction in uncompensated care spending. To arrive at the figures, ASPE analyzed uncompensated hospital care levels and cost reports from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, census data, estimates from Gallup-Healthways, and Medicaid enrollment data.

While $5 billion of the reduction came from the 28 states that have expanded Medicaid, $2 billion resulted from the 22 states that have not expanded Medicaid, according to ASPE. The government noted that if the nonexpansion states had increases proportionately as large in Medicaid coverage as did the expansion states, their uncompensated care costs would have declined by an additional $1.4 billion.

March 23 marked the fifth anniversary of President Obama’s signing the ACA into law. In a statement by the White House, the president praised the law’s success, and its impact on patients and the country.

On Twitter @legal_med

Uncompensated hospital care costs fell by an estimated $7 billion in 2014 because of marketplace coverage and state Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act, according to a March 23 report by the Department of Health & Human Services. State Medicaid expansions accounted for an estimated $5 billion of the reduction, the HHS analysis found.

U.S. hospitals provided $50 billion in uncompensated care in 2013, the report found. Based on estimated coverage gains in 2014, the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) estimates that uncompensated care costs were $7.4 billion lower in 2014 than they would have been had insurance coverage remained at 2013 levels. Hospitals spent an estimated $27 billion in uncompensated care in 2014, compared with an estimated $35 billion at 2013 coverage levels, a 21% reduction in uncompensated care spending. To arrive at the figures, ASPE analyzed uncompensated hospital care levels and cost reports from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, census data, estimates from Gallup-Healthways, and Medicaid enrollment data.

While $5 billion of the reduction came from the 28 states that have expanded Medicaid, $2 billion resulted from the 22 states that have not expanded Medicaid, according to ASPE. The government noted that if the nonexpansion states had increases proportionately as large in Medicaid coverage as did the expansion states, their uncompensated care costs would have declined by an additional $1.4 billion.

March 23 marked the fifth anniversary of President Obama’s signing the ACA into law. In a statement by the White House, the president praised the law’s success, and its impact on patients and the country.

On Twitter @legal_med

Use psychoeducational family therapy to help families cope with autism

Treating a family in crisis because of a difficult-to-manage family member with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be overwhelming. The family often is desperate and exhausted and, therefore, can be overly needy, demanding, and disorganized. Psychiatrists often are asked to intervene with medication, even though there are no drugs to treat core symptoms of ASD. At best, medication can ease associated symptoms, such as insomnia. However, when coupled with reasonable medication management, psychoeducational family therapy can be an effective, powerful intervention during initial and follow-up medication visits.

Families of ASD patients often show dysfunctional patterns: poor interpersonal and generational boundaries, closed family systems, pathological triangulations, fused and disengaged relationships, resentments, etc. It is easy to assume that an autistic patient’s behavior problems are related to these dysfunctional patterns, and these patterns are caused by psychopathology within the family. In the 1970s and 1980s researchers began to challenge this same assumption in families of patients with schizophrenia and found that the illness shaped family patterns, not the reverse. Illness exacerbations could be minimized by teaching families to reduce their expressed emotions. In addition, research clinicians stopped blaming family members and began describing family dysfunction as a “normal response” to severe psychiatric illness.1

Families of autistic individuals should learn to avoid coercive patterns and clarify interpersonal boundaries. Family members also should understand that dysfunctional patterns are a normal response to illness, these patterns can be corrected, and the correction can lead to improved management of ASD.

Psychoeducational family therapy provides an excellent framework for this family-psychiatrist interaction. Time-consuming, complex, expressive family therapies are not recommended because they tend to heighten expressed emotions.

Consider the following tips when providing psychoeducational family therapy:

• Remember that the extreme stress these families experience is based in reality. Lower functioning ASD patients might not sleep, require constant supervision, and cannot tolerate even minor frustrations.

• Respect the family’s ego defenses as a normal response to stress. Expect to feel some initial frustration and anxiety when working with overwhelmed families.

• Normalize negative feelings within the family. Everyone goes through anger, grief, and hopelessness when handling such a stressful situation.

• Avoid blaming dysfunctional patterns on individuals. Dysfunctional behavior is a normal response to the stress of caring for a family member with ASD.

• Empower the family. Remind the family that they know the patient best, so help them to find their own solutions to behavioral problems.

• Focus on the basics including establishing normal sleeping patterns and regular household routines.

• Educate the family about low sensory stimulation in the home. ASD patients are easily overwhelmed by sensory stimulation which can lead to lower frustration tolerance.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Nichols MP. Family therapy: concepts and methods. 7th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2006.

Treating a family in crisis because of a difficult-to-manage family member with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be overwhelming. The family often is desperate and exhausted and, therefore, can be overly needy, demanding, and disorganized. Psychiatrists often are asked to intervene with medication, even though there are no drugs to treat core symptoms of ASD. At best, medication can ease associated symptoms, such as insomnia. However, when coupled with reasonable medication management, psychoeducational family therapy can be an effective, powerful intervention during initial and follow-up medication visits.

Families of ASD patients often show dysfunctional patterns: poor interpersonal and generational boundaries, closed family systems, pathological triangulations, fused and disengaged relationships, resentments, etc. It is easy to assume that an autistic patient’s behavior problems are related to these dysfunctional patterns, and these patterns are caused by psychopathology within the family. In the 1970s and 1980s researchers began to challenge this same assumption in families of patients with schizophrenia and found that the illness shaped family patterns, not the reverse. Illness exacerbations could be minimized by teaching families to reduce their expressed emotions. In addition, research clinicians stopped blaming family members and began describing family dysfunction as a “normal response” to severe psychiatric illness.1

Families of autistic individuals should learn to avoid coercive patterns and clarify interpersonal boundaries. Family members also should understand that dysfunctional patterns are a normal response to illness, these patterns can be corrected, and the correction can lead to improved management of ASD.

Psychoeducational family therapy provides an excellent framework for this family-psychiatrist interaction. Time-consuming, complex, expressive family therapies are not recommended because they tend to heighten expressed emotions.

Consider the following tips when providing psychoeducational family therapy:

• Remember that the extreme stress these families experience is based in reality. Lower functioning ASD patients might not sleep, require constant supervision, and cannot tolerate even minor frustrations.

• Respect the family’s ego defenses as a normal response to stress. Expect to feel some initial frustration and anxiety when working with overwhelmed families.

• Normalize negative feelings within the family. Everyone goes through anger, grief, and hopelessness when handling such a stressful situation.

• Avoid blaming dysfunctional patterns on individuals. Dysfunctional behavior is a normal response to the stress of caring for a family member with ASD.

• Empower the family. Remind the family that they know the patient best, so help them to find their own solutions to behavioral problems.

• Focus on the basics including establishing normal sleeping patterns and regular household routines.

• Educate the family about low sensory stimulation in the home. ASD patients are easily overwhelmed by sensory stimulation which can lead to lower frustration tolerance.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Treating a family in crisis because of a difficult-to-manage family member with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be overwhelming. The family often is desperate and exhausted and, therefore, can be overly needy, demanding, and disorganized. Psychiatrists often are asked to intervene with medication, even though there are no drugs to treat core symptoms of ASD. At best, medication can ease associated symptoms, such as insomnia. However, when coupled with reasonable medication management, psychoeducational family therapy can be an effective, powerful intervention during initial and follow-up medication visits.

Families of ASD patients often show dysfunctional patterns: poor interpersonal and generational boundaries, closed family systems, pathological triangulations, fused and disengaged relationships, resentments, etc. It is easy to assume that an autistic patient’s behavior problems are related to these dysfunctional patterns, and these patterns are caused by psychopathology within the family. In the 1970s and 1980s researchers began to challenge this same assumption in families of patients with schizophrenia and found that the illness shaped family patterns, not the reverse. Illness exacerbations could be minimized by teaching families to reduce their expressed emotions. In addition, research clinicians stopped blaming family members and began describing family dysfunction as a “normal response” to severe psychiatric illness.1

Families of autistic individuals should learn to avoid coercive patterns and clarify interpersonal boundaries. Family members also should understand that dysfunctional patterns are a normal response to illness, these patterns can be corrected, and the correction can lead to improved management of ASD.

Psychoeducational family therapy provides an excellent framework for this family-psychiatrist interaction. Time-consuming, complex, expressive family therapies are not recommended because they tend to heighten expressed emotions.

Consider the following tips when providing psychoeducational family therapy:

• Remember that the extreme stress these families experience is based in reality. Lower functioning ASD patients might not sleep, require constant supervision, and cannot tolerate even minor frustrations.

• Respect the family’s ego defenses as a normal response to stress. Expect to feel some initial frustration and anxiety when working with overwhelmed families.

• Normalize negative feelings within the family. Everyone goes through anger, grief, and hopelessness when handling such a stressful situation.

• Avoid blaming dysfunctional patterns on individuals. Dysfunctional behavior is a normal response to the stress of caring for a family member with ASD.

• Empower the family. Remind the family that they know the patient best, so help them to find their own solutions to behavioral problems.

• Focus on the basics including establishing normal sleeping patterns and regular household routines.

• Educate the family about low sensory stimulation in the home. ASD patients are easily overwhelmed by sensory stimulation which can lead to lower frustration tolerance.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Nichols MP. Family therapy: concepts and methods. 7th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2006.

Reference

1. Nichols MP. Family therapy: concepts and methods. 7th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2006.

Depressed and sick with ‘nothing to live for’

CASE ‘I’ve had enough’

The psychiatry consultation team is asked to evaluate Mr. M, age 76, for a passive death wish and depression 2 months after he was admitted to the hospital after a traumatic fall.

Mr. M has several chronic medical conditions, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease. Within 2 weeks of his admission, he developed Proteus mirabilis pneumonia and persistent respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy. Records indicate that Mr. M has told family and his treatment team, “I’m tired, just let me go.” He then developed antibiotic-induced Clostridium difficile colitis and acute renal failure requiring temporary renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Mr. M’s clinical status improves, allowing his transfer to a transitional unit, where he continues to state, “I have had enough. I’m done.” He asks for the tracheostomy tube to be removed and RRT discontinued. He is treated again for persistent C. difficile colitis and, within 2 weeks, develops hypotension, hypoxia, emesis, and abdominal distension, requiring transfer to the ICU for management of ileus.

He is stabilized with vasopressors and artificial nutritional support by nasogastric tube. Renal function improves, RRT is discontinued, and he is transferred to the general medical floor.

After a few days on the general medical floor, Mr. M develops a urinary tract infection and develops antibiotic-induced acute renal failure requiring re-initiation of RRT. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is placed for nutrition when he shows little improvement with swallowing exercises. Two days after placing the PEG tube, he develops respiratory failure secondary to a left-sided pneumothorax and is transferred to the ICU for the third time, where he undergoes repeated bronchoscopies and requires pressure support ventilation.

One week later, Mr. M is weaned off the ventilator and transferred to the general medical floor with aggressive respiratory therapy, tube feeding, and RRT. Mr. M’s chart indicates that he expresses an ongoing desire to withdraw RRT, the tracheostomy, and feeding tube.

Which of the following would you consider when assessing Mr. M’s decision-making capacity (DMC)?

a) his ability to understand information relevant to treatment decision-making

b) his ability to appreciate the significance of his diagnoses and treatment options and consequences in the context of his own life circumstances

c) his ability to communicate a preference

d) his ability to reason through the relevant information to weigh the potential costs and benefits of treatment options

e) all of the above

HISTORY Guilt and regret

Mr. M reports a 30-year history of depression that has responded poorly to a variety of medications, outpatient psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy. Before admission, he says, he was adherent to citalopram, 20 mg/d, and buspirone, 30 mg/d. Citalopram is continued throughout his hospitalization, although buspirone was discontinued for unknown reasons during admission.

Mr. M is undergoing hemodialysis during his initial encounter with the psychiatry team. He struggles to communicate clearly because of the tracheostomy but is alert, oriented to person and location, answers questions appropriately, maintains good eye contact, and does not demonstrate any psychomotor abnormalities. He describes his disposition as “tired,” and is on the verge of tears during the interview.

Mr. M denies physical discomfort and states, “I have just had enough. I do not want all of this done.” He clarifies that he is not suicidal and denies a history of suicidal or self-injurious behaviors.

Mr. M describes having low mood, anhedonia, and insomnia to varying degrees throughout his adult life. He also reports feeling guilt and regret about earlier experiences, but does not elaborate. He denies symptoms of panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, mania, or hypomania. He reports an episode of visual hallucinations during an earlier hospitalization, likely a symptom of delirium, but denies any recent visual disturbances.

Mr. M’s thought process is linear and logical, with intact abstract reasoning and no evidence of delusions. Attention and concentration are intact for most of the interview but diminish as he becomes fatigued. Mr. M can describe past treatments in detail and recounts the events leading to this hospitalization.

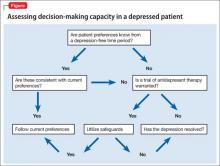

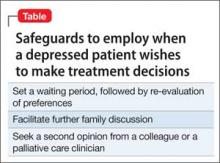

The authors’ observations

Literature on assessment of DMC recently has centered on the 4-ability model, proposed by Grisso and Appelbaum.1 With this approach, impairment to any of the 4 processes of understanding, appreciation, ability to express a choice, and ability to use reasoning to weigh treatment options could interfere with capacity to make decisions. Few studies have clarified the mechanism and degree to which depression may impair these 4 elements, making capacity assessments in a depressed patient challenging.

Preliminary evidence suggests that depression severity, not the presence of depression, determines the degree to which DMC is impaired, if at all. In several studies, depressed patients did not demonstrate more impaired DMC compared with non-depressed patients based on standardized assessments.2-4 In depressed patients who lack DMC, case reports5-7 and cross-sectional studies8 indicate that appreciation—one’s ability to comprehend the personal relevance of illness and potential consequences of treatments in the context of one’s life—is most often impaired. Other studies suggest that the ability to reason through decision-specific information and weigh the risks and benefits of treatment options is commonly impaired in depressed patients.9,10

Even when a depressed patient demonstrates the 4 elements of DMC, providers might be concerned that the patient’s preferences are skewed by the negative emotions associated with depression.11-13 In such a case, the patient’s expressed wishes might not be consistent with views and priorities that were expressed during an earlier, euthymic period.

Rather than focusing on whether cognitive elements of DMC are impaired, some experts advocate for assessing how depression might lead to “unbalanced” decision-making that is impaired by a patient’s tendency to undervalue positive outcomes and overvalue negative ones.14 Some depressed patients will decide to forego additional medical interventions because they do not see the potential benefits of treatment, view events through a negative lens, and lack hope for the future; however, studies indicate this is not typically the case.15-17

In a study of >2,500 patients age >65 with chronic medical conditions, Garrett et al15 found that those who were depressed communicated a desire for more treatment compared with non-depressed patients. Another study of patients’ wishes for life-sustaining treatment among those who had mild or moderate depression found that most patients did not express a greater desire for life-sustaining medical interventions after their depressive episode remitted. An increased desire for life-sustaining medical interventions occurred only among the most severely depressed patients.16 Similarly, Lee and Ganzini17 found that treatment preferences among patients with mild or moderate depression and serious physical illness were unchanged after the mood disorder was treated.

These findings demonstrate that a clinician charged with assessing DMC must evaluate the severity of a patient’s depression and carefully consider how mood is influencing his (her) perspective and cognitive abilities. It is important to observe how the depressed patient perceives feelings of sadness or hopelessness in the context of decision-making, and how he (she) integrates these feelings when assigning relative value to potential outcomes and alternative treatment options. Because the intensity of depression could vary over time, assessment of the depressed patient’s decision-making abilities must be viewed as a dynamic process.

Clinical application

Recent studies indicate that, although the in-hospital mortality rate for critically ill patients who develop acute renal failure is high, it is variable, ranging from 28% to 90%.18 In one study, patients who required more interventions over the course of a hospital stay (eg, mechanical ventilation, vasopressors) had an in-hospital mortality rate closer to 60% after initiating RRT.19 In a similar trial,20,21 mean survival for critically ill patients with acute renal failure was 32 days from initiation of dialysis; only 27% of these patients were alive 6 months later.21

Given his complicated hospital course, the medical team estimates that Mr. M has a reasonable chance of surviving to discharge, although his longer-term prognosis is poor.

EVALUATION Conflicting preferences

Mr. M expresses reasonable understanding of the medical indications for temporary RRT, respiratory therapy, and enteral tube feedings, and the consequences of withdrawing these interventions. He understands that the primary team recommended ongoing but temporary use of life-sustaining interventions, anticipating that he would recover from his acute medical conditions. Mr. M clearly articulates that he wants to terminate RRT knowing that this would cause a buildup of urea and other toxins, to resume eating by mouth despite the risk of aspiration, and to be allowed to die “naturally.”

Mr. M declines to speak with a clergy member, explaining that he preferred direct contact with God and had reconciled himself to the “consequences” of his actions. He reports having “nothing left to live for” and “nothing left to do.” He says that he is “tired of being a burden” to his wife and son, regrets the way he treated them in the past, and believes they would be better off without him.

Although Mr. M’s abilities to understand, reason, and express a preference are intact, the psychiatry team is concerned that depression could be influencing his perspective, thereby compromising his appreciation for the personal relevance of his request to withdraw life-sustaining treatments. The psychiatrist shares this concern with Mr. M, who voices an understanding that undertreated depression could lead him to make irreversible decisions about his medical treatment that he might not make if he were not depressed; nevertheless, he continues to state that he is “ready” to die. With his permission, the team seeks additional information from Mr. M’s family.

Mr. M’s wife recalls a conversation with her husband 5 years ago in which he said that, were he to become seriously ill, “he would want everything done.” However, she also reports that Mr. M has been expressing a passive death wish “for years,” as he was struggling with chronic medical conditions that led to recurrent hospital admissions.

“He has always been a negative person,” she adds, and confirms that he has been depressed for most of their marriage.

The conflict between Mr. M’s earlier expressed preference for full care and his current wish to withdraw life-sustaining therapies and experience a “natural death” raises significant concern that depression could explain this change in perspective. When asked about this discrepancy, Mr. M admits that he “wanted everything done” in the past, when he was younger and healthier, but his preferences changed as his chronic medical problems progressed.

OUTCOME Better mood, discharge