User login

AAN: Facial nerve stimulator relieves cluster headaches

WASHINGTON – An implantable device that stimulates the sphenopalatine ganglion nerve bundle either reduced or eliminated pain in 68% of more than 5,000 cluster headaches, a 3-year study has determined.

The device, which is approved in Europe, was more effective in attacks of moderate severity, with a 78% rate of pain reduction or elimination, Dr. Jose Miguel Lainez reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

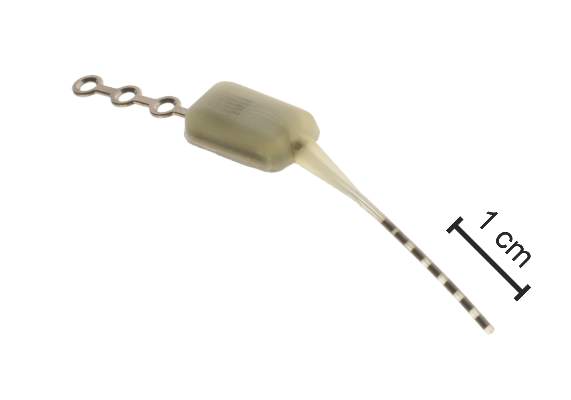

The Pulsante System, manufactured by Autonomic Technologiesof Redwood City, Calif., consists of a neurostimulator about the size of an almond, and a lead with six electrodes. It’s inserted under local anesthetic via a small incision in the upper gum on the side in which the patient experiences symptoms. The electrodes are positioned along the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) nerve and the neurostimulator is affixed to the zygomatic process.

A hand-held remote controller placed against the cheek activates the device and controls the intensity of stimulation, which is thought to work by blocking signals to the postganglionic parasympathetic fibers. Those fibers innervate facial structures and the cerebral and meningeal blood vessels and are implicated in the pain and accompanying autonomic symptoms of a cluster headache attack.

Dr. Lainez, professor of neurology at Catholic University of Valencia (Spain), presented 3-year follow-up data from Pathway CH-1, a randomized, sham-controlled trial of 43 patients with cluster headache. Of these, 33 completed the 3-year follow-up period. Of the remaining 10, 1 was lost from observation, 5 violated protocol, 1 had the device implanted incorrectly, and 3 had the device explanted because of incorrect placement or lead migration.

Most of the patients were male. Mean age was 41 years. They had a mean disease duration of 10 years and averaged 17 cluster headaches per week but ranged from 4 to 70 attacks per week. Over the 3 years, 5,130 attacks were treated; the mean stimulation duration for these was 14 minutes with a mean response time of 11 minutes. Therapy was considered effective in 65% (3,354) of these attacks based on a clinically meaningful reduction in pain or pain elimination.

Dr. Lainez did not parse these results. However, in the initial 28-week phase of the Pathway CH-1 study, pain was reduced in 68% of attacks treated with the device and 7% of those treated with the sham control. Pain freedom by 15 minutes was achieved in 34% of attacks with full stimulation, compared with 1.5% of those treated with sham.

In the follow-up study, the device seemed most effective in attacks of moderate severity (78% response rate of pain reduction or elimination). The response rate was 59% in mild attacks and 51% in severe attacks. Most attacks treated with the device (77%) did not involve the use of abortive therapy.

Dr. Lainez did not mention adverse events related to the device. However, in the 28-week study, there were 92, including parasthesias and numbness; facial and tooth pain; and swelling. Others were considered mild and included dry eye, nose bleed, and facial asymmetry.

The device is currently being investigated in a U.S. study. The open-label Pathway-CH2 study aims to recruit 120 patients. For information on Pathway CH-2, contact Anthony Caparso.

The trial was sponsored by Autonomic Technologies Inc. Dr. Lainez had no financial ties with the company.

On Twitter @alz_gal

WASHINGTON – An implantable device that stimulates the sphenopalatine ganglion nerve bundle either reduced or eliminated pain in 68% of more than 5,000 cluster headaches, a 3-year study has determined.

The device, which is approved in Europe, was more effective in attacks of moderate severity, with a 78% rate of pain reduction or elimination, Dr. Jose Miguel Lainez reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The Pulsante System, manufactured by Autonomic Technologiesof Redwood City, Calif., consists of a neurostimulator about the size of an almond, and a lead with six electrodes. It’s inserted under local anesthetic via a small incision in the upper gum on the side in which the patient experiences symptoms. The electrodes are positioned along the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) nerve and the neurostimulator is affixed to the zygomatic process.

A hand-held remote controller placed against the cheek activates the device and controls the intensity of stimulation, which is thought to work by blocking signals to the postganglionic parasympathetic fibers. Those fibers innervate facial structures and the cerebral and meningeal blood vessels and are implicated in the pain and accompanying autonomic symptoms of a cluster headache attack.

Dr. Lainez, professor of neurology at Catholic University of Valencia (Spain), presented 3-year follow-up data from Pathway CH-1, a randomized, sham-controlled trial of 43 patients with cluster headache. Of these, 33 completed the 3-year follow-up period. Of the remaining 10, 1 was lost from observation, 5 violated protocol, 1 had the device implanted incorrectly, and 3 had the device explanted because of incorrect placement or lead migration.

Most of the patients were male. Mean age was 41 years. They had a mean disease duration of 10 years and averaged 17 cluster headaches per week but ranged from 4 to 70 attacks per week. Over the 3 years, 5,130 attacks were treated; the mean stimulation duration for these was 14 minutes with a mean response time of 11 minutes. Therapy was considered effective in 65% (3,354) of these attacks based on a clinically meaningful reduction in pain or pain elimination.

Dr. Lainez did not parse these results. However, in the initial 28-week phase of the Pathway CH-1 study, pain was reduced in 68% of attacks treated with the device and 7% of those treated with the sham control. Pain freedom by 15 minutes was achieved in 34% of attacks with full stimulation, compared with 1.5% of those treated with sham.

In the follow-up study, the device seemed most effective in attacks of moderate severity (78% response rate of pain reduction or elimination). The response rate was 59% in mild attacks and 51% in severe attacks. Most attacks treated with the device (77%) did not involve the use of abortive therapy.

Dr. Lainez did not mention adverse events related to the device. However, in the 28-week study, there were 92, including parasthesias and numbness; facial and tooth pain; and swelling. Others were considered mild and included dry eye, nose bleed, and facial asymmetry.

The device is currently being investigated in a U.S. study. The open-label Pathway-CH2 study aims to recruit 120 patients. For information on Pathway CH-2, contact Anthony Caparso.

The trial was sponsored by Autonomic Technologies Inc. Dr. Lainez had no financial ties with the company.

On Twitter @alz_gal

WASHINGTON – An implantable device that stimulates the sphenopalatine ganglion nerve bundle either reduced or eliminated pain in 68% of more than 5,000 cluster headaches, a 3-year study has determined.

The device, which is approved in Europe, was more effective in attacks of moderate severity, with a 78% rate of pain reduction or elimination, Dr. Jose Miguel Lainez reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The Pulsante System, manufactured by Autonomic Technologiesof Redwood City, Calif., consists of a neurostimulator about the size of an almond, and a lead with six electrodes. It’s inserted under local anesthetic via a small incision in the upper gum on the side in which the patient experiences symptoms. The electrodes are positioned along the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) nerve and the neurostimulator is affixed to the zygomatic process.

A hand-held remote controller placed against the cheek activates the device and controls the intensity of stimulation, which is thought to work by blocking signals to the postganglionic parasympathetic fibers. Those fibers innervate facial structures and the cerebral and meningeal blood vessels and are implicated in the pain and accompanying autonomic symptoms of a cluster headache attack.

Dr. Lainez, professor of neurology at Catholic University of Valencia (Spain), presented 3-year follow-up data from Pathway CH-1, a randomized, sham-controlled trial of 43 patients with cluster headache. Of these, 33 completed the 3-year follow-up period. Of the remaining 10, 1 was lost from observation, 5 violated protocol, 1 had the device implanted incorrectly, and 3 had the device explanted because of incorrect placement or lead migration.

Most of the patients were male. Mean age was 41 years. They had a mean disease duration of 10 years and averaged 17 cluster headaches per week but ranged from 4 to 70 attacks per week. Over the 3 years, 5,130 attacks were treated; the mean stimulation duration for these was 14 minutes with a mean response time of 11 minutes. Therapy was considered effective in 65% (3,354) of these attacks based on a clinically meaningful reduction in pain or pain elimination.

Dr. Lainez did not parse these results. However, in the initial 28-week phase of the Pathway CH-1 study, pain was reduced in 68% of attacks treated with the device and 7% of those treated with the sham control. Pain freedom by 15 minutes was achieved in 34% of attacks with full stimulation, compared with 1.5% of those treated with sham.

In the follow-up study, the device seemed most effective in attacks of moderate severity (78% response rate of pain reduction or elimination). The response rate was 59% in mild attacks and 51% in severe attacks. Most attacks treated with the device (77%) did not involve the use of abortive therapy.

Dr. Lainez did not mention adverse events related to the device. However, in the 28-week study, there were 92, including parasthesias and numbness; facial and tooth pain; and swelling. Others were considered mild and included dry eye, nose bleed, and facial asymmetry.

The device is currently being investigated in a U.S. study. The open-label Pathway-CH2 study aims to recruit 120 patients. For information on Pathway CH-2, contact Anthony Caparso.

The trial was sponsored by Autonomic Technologies Inc. Dr. Lainez had no financial ties with the company.

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE AAN 2015 ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: An implantable device that stimulates the sphenopalatine ganglion nerve provided pain relief in cluster headaches.

Major finding: The device reduced or eliminated pain in 68% of more than 5,000 cluster headaches.

Data source: A 3-year follow-up study that examined response in more than 5,000 cluster headaches.

Disclosures: The trial was sponsored by Autonomic Technologies Inc., which makes the Pulsante System. Dr. Lainez had no financial disclosures.

Drug shows promise for lower-risk MDS

WASHINGTON, DC—An investigational drug can increase hemoglobin levels and eliminate transfusion dependence in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), results of a phase 2 trial suggest.

The drug, luspatercept, is a modified activin receptor type IIB fusion protein that acts as a ligand trap for members in the TGF-β superfamily involved in the late stages of erythropoiesis.

Luspatercept regulates late-stage erythrocyte precursor differentiation and maturation.

Uwe Platzbecker, MD, of the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, presented results from an ongoing phase 2 study of luspatercept at the 13th International Symposium on Myelodysplastic Syndromes (abstract 53).

The trial is supported by Acceleron Pharma Inc. and Celgene Corporation, the companies developing luspatercept.

“We are excited by the results in lower-risk MDS patients, which confirm and extend our previous findings,” Dr Platzbecker said. “Luspatercept may be useful early in the treatment of lower-risk MDS patients, either as the initial treatment for anemia or in patients who do not respond or become refractory to treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents.”

Patient and dosing details

The researchers enrolled 58 patients in this study. Twenty-seven have completed treatment as part of the dose-escalation cohort. These patients received luspatercept at 7 doses ranging from 0.125 mg/kg to 1.75 mg/kg.

Thirty-one patients are still receiving treatment in the expansion cohort. The starting dose in this cohort is 1.0 mg/kg, and patients are receiving individual dose titration up to 1.75 mg/kg. Seventeen patients from this cohort received at least 4 cycles of treatment or discontinued early and were included in the analysis presented at the meeting.

In all, Dr Platzbecker presented results in 44 patients. Their median age was 71 (range, 27-88), and 57% were male. The median time since diagnosis was 2.5 years (range, 0.2-13.6 years). Sixty-one percent of patients had received prior treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and 21% had received lenalidomide.

Fifteen patients had a low transfusion burden (LTB), as they received less than 4 units of red blood cells (RBCs) over 8 weeks. For these patients, the median hemoglobin at baseline was 9.0 g/dL (range, 6.8-10.1), and the median number of RBCs transfused over 8 weeks was 2 (range, 2-2).

Twenty-nine patients had a high transfusion burden (HTB) and received 4 or more RBC units over 8 weeks. The median number of RBCs transfused in this group was 6 (range, 4-14).

Fifty percent of patients had low-risk MDS according to IPSS, 46% had intermediate-1-risk disease, and 4% had intermediate-2-risk MDS. Eighty-one percent of patients were positive for ring sideroblasts, and 58% had the SF3B1 splicing mutation.

Efficacy and safety

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was an increase in hemoglobin and/or a reduction in transfusion use. For LTB patients, the endpoint was a hemoglobin increase of 1.5 g/dL or more for 2 weeks or longer. For HTB patients, it was decrease in transfusion of 4 or more RBC units or a 50% or greater reduction in transfusion over 8 weeks.

Among the 9 patients who received lower doses of luspatercept (0.125-0.5 mg/kg), 33% met the primary efficacy endpoint. And 63% of the 35 patients in the higher dose group (0.75-1.75 mg/kg) achieved the primary efficacy endpoint.

Twenty-two percent of patients in the lower dose group achieved the International Working Group (IWG) hematologic improvement-erythroid (HI-E) threshold of efficacy, as did 54% of patients in the higher dose group.

Fourteen percent of patients in the lower dose group achieved transfusion independence, as did 36% of patients in the higher dose group. In the higher dose group, this included 4 of 6 patients with LTB and 6 of 22 patients with HTB.

Among patients who were ring-sideroblast-positive and received higher doses of luspatercept, 39% achieved transfusion independence, and 63% achieved IWG HI-E.

The majority of adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate (grade 1 or 2). AEs included nasopharyngitis (14%), diarrhea (14%), myalgia (11%), bone pain (9%), bronchitis (9%), headache (9%), and muscle spasms (9%).

There were 2 serious AEs—grade 3 muscle pain and grade 3 worsening of general condition—that were considered possibly related to treatment. One non-serious grade 3 AE of blast cell count increase was considered possibly treatment-related as well.

In closing, Dr Platzbecker said luspatercept was generally safe and well-tolerated, in addition to providing “robust hematologic improvement.” And these results support further study of the drug in patients with lower-risk MDS. ![]()

WASHINGTON, DC—An investigational drug can increase hemoglobin levels and eliminate transfusion dependence in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), results of a phase 2 trial suggest.

The drug, luspatercept, is a modified activin receptor type IIB fusion protein that acts as a ligand trap for members in the TGF-β superfamily involved in the late stages of erythropoiesis.

Luspatercept regulates late-stage erythrocyte precursor differentiation and maturation.

Uwe Platzbecker, MD, of the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, presented results from an ongoing phase 2 study of luspatercept at the 13th International Symposium on Myelodysplastic Syndromes (abstract 53).

The trial is supported by Acceleron Pharma Inc. and Celgene Corporation, the companies developing luspatercept.

“We are excited by the results in lower-risk MDS patients, which confirm and extend our previous findings,” Dr Platzbecker said. “Luspatercept may be useful early in the treatment of lower-risk MDS patients, either as the initial treatment for anemia or in patients who do not respond or become refractory to treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents.”

Patient and dosing details

The researchers enrolled 58 patients in this study. Twenty-seven have completed treatment as part of the dose-escalation cohort. These patients received luspatercept at 7 doses ranging from 0.125 mg/kg to 1.75 mg/kg.

Thirty-one patients are still receiving treatment in the expansion cohort. The starting dose in this cohort is 1.0 mg/kg, and patients are receiving individual dose titration up to 1.75 mg/kg. Seventeen patients from this cohort received at least 4 cycles of treatment or discontinued early and were included in the analysis presented at the meeting.

In all, Dr Platzbecker presented results in 44 patients. Their median age was 71 (range, 27-88), and 57% were male. The median time since diagnosis was 2.5 years (range, 0.2-13.6 years). Sixty-one percent of patients had received prior treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and 21% had received lenalidomide.

Fifteen patients had a low transfusion burden (LTB), as they received less than 4 units of red blood cells (RBCs) over 8 weeks. For these patients, the median hemoglobin at baseline was 9.0 g/dL (range, 6.8-10.1), and the median number of RBCs transfused over 8 weeks was 2 (range, 2-2).

Twenty-nine patients had a high transfusion burden (HTB) and received 4 or more RBC units over 8 weeks. The median number of RBCs transfused in this group was 6 (range, 4-14).

Fifty percent of patients had low-risk MDS according to IPSS, 46% had intermediate-1-risk disease, and 4% had intermediate-2-risk MDS. Eighty-one percent of patients were positive for ring sideroblasts, and 58% had the SF3B1 splicing mutation.

Efficacy and safety

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was an increase in hemoglobin and/or a reduction in transfusion use. For LTB patients, the endpoint was a hemoglobin increase of 1.5 g/dL or more for 2 weeks or longer. For HTB patients, it was decrease in transfusion of 4 or more RBC units or a 50% or greater reduction in transfusion over 8 weeks.

Among the 9 patients who received lower doses of luspatercept (0.125-0.5 mg/kg), 33% met the primary efficacy endpoint. And 63% of the 35 patients in the higher dose group (0.75-1.75 mg/kg) achieved the primary efficacy endpoint.

Twenty-two percent of patients in the lower dose group achieved the International Working Group (IWG) hematologic improvement-erythroid (HI-E) threshold of efficacy, as did 54% of patients in the higher dose group.

Fourteen percent of patients in the lower dose group achieved transfusion independence, as did 36% of patients in the higher dose group. In the higher dose group, this included 4 of 6 patients with LTB and 6 of 22 patients with HTB.

Among patients who were ring-sideroblast-positive and received higher doses of luspatercept, 39% achieved transfusion independence, and 63% achieved IWG HI-E.

The majority of adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate (grade 1 or 2). AEs included nasopharyngitis (14%), diarrhea (14%), myalgia (11%), bone pain (9%), bronchitis (9%), headache (9%), and muscle spasms (9%).

There were 2 serious AEs—grade 3 muscle pain and grade 3 worsening of general condition—that were considered possibly related to treatment. One non-serious grade 3 AE of blast cell count increase was considered possibly treatment-related as well.

In closing, Dr Platzbecker said luspatercept was generally safe and well-tolerated, in addition to providing “robust hematologic improvement.” And these results support further study of the drug in patients with lower-risk MDS. ![]()

WASHINGTON, DC—An investigational drug can increase hemoglobin levels and eliminate transfusion dependence in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), results of a phase 2 trial suggest.

The drug, luspatercept, is a modified activin receptor type IIB fusion protein that acts as a ligand trap for members in the TGF-β superfamily involved in the late stages of erythropoiesis.

Luspatercept regulates late-stage erythrocyte precursor differentiation and maturation.

Uwe Platzbecker, MD, of the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, presented results from an ongoing phase 2 study of luspatercept at the 13th International Symposium on Myelodysplastic Syndromes (abstract 53).

The trial is supported by Acceleron Pharma Inc. and Celgene Corporation, the companies developing luspatercept.

“We are excited by the results in lower-risk MDS patients, which confirm and extend our previous findings,” Dr Platzbecker said. “Luspatercept may be useful early in the treatment of lower-risk MDS patients, either as the initial treatment for anemia or in patients who do not respond or become refractory to treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents.”

Patient and dosing details

The researchers enrolled 58 patients in this study. Twenty-seven have completed treatment as part of the dose-escalation cohort. These patients received luspatercept at 7 doses ranging from 0.125 mg/kg to 1.75 mg/kg.

Thirty-one patients are still receiving treatment in the expansion cohort. The starting dose in this cohort is 1.0 mg/kg, and patients are receiving individual dose titration up to 1.75 mg/kg. Seventeen patients from this cohort received at least 4 cycles of treatment or discontinued early and were included in the analysis presented at the meeting.

In all, Dr Platzbecker presented results in 44 patients. Their median age was 71 (range, 27-88), and 57% were male. The median time since diagnosis was 2.5 years (range, 0.2-13.6 years). Sixty-one percent of patients had received prior treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and 21% had received lenalidomide.

Fifteen patients had a low transfusion burden (LTB), as they received less than 4 units of red blood cells (RBCs) over 8 weeks. For these patients, the median hemoglobin at baseline was 9.0 g/dL (range, 6.8-10.1), and the median number of RBCs transfused over 8 weeks was 2 (range, 2-2).

Twenty-nine patients had a high transfusion burden (HTB) and received 4 or more RBC units over 8 weeks. The median number of RBCs transfused in this group was 6 (range, 4-14).

Fifty percent of patients had low-risk MDS according to IPSS, 46% had intermediate-1-risk disease, and 4% had intermediate-2-risk MDS. Eighty-one percent of patients were positive for ring sideroblasts, and 58% had the SF3B1 splicing mutation.

Efficacy and safety

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was an increase in hemoglobin and/or a reduction in transfusion use. For LTB patients, the endpoint was a hemoglobin increase of 1.5 g/dL or more for 2 weeks or longer. For HTB patients, it was decrease in transfusion of 4 or more RBC units or a 50% or greater reduction in transfusion over 8 weeks.

Among the 9 patients who received lower doses of luspatercept (0.125-0.5 mg/kg), 33% met the primary efficacy endpoint. And 63% of the 35 patients in the higher dose group (0.75-1.75 mg/kg) achieved the primary efficacy endpoint.

Twenty-two percent of patients in the lower dose group achieved the International Working Group (IWG) hematologic improvement-erythroid (HI-E) threshold of efficacy, as did 54% of patients in the higher dose group.

Fourteen percent of patients in the lower dose group achieved transfusion independence, as did 36% of patients in the higher dose group. In the higher dose group, this included 4 of 6 patients with LTB and 6 of 22 patients with HTB.

Among patients who were ring-sideroblast-positive and received higher doses of luspatercept, 39% achieved transfusion independence, and 63% achieved IWG HI-E.

The majority of adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate (grade 1 or 2). AEs included nasopharyngitis (14%), diarrhea (14%), myalgia (11%), bone pain (9%), bronchitis (9%), headache (9%), and muscle spasms (9%).

There were 2 serious AEs—grade 3 muscle pain and grade 3 worsening of general condition—that were considered possibly related to treatment. One non-serious grade 3 AE of blast cell count increase was considered possibly treatment-related as well.

In closing, Dr Platzbecker said luspatercept was generally safe and well-tolerated, in addition to providing “robust hematologic improvement.” And these results support further study of the drug in patients with lower-risk MDS. ![]()

Whole blood better for cardiac surgery in young children

Photo by Elise Amendola

Using fresh whole blood (FWB) from single donors for cardiac procedures in children younger than 2 years of age is better than using component blood from multiple donors, researchers say.

FWB reduces the risk of getting transfusion-related illnesses by reducing donor exposures.

“Currently, whole blood is not generally made available to hospitals for use in pediatric heart surgery,” said David R. Jobes, MD, of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania.

“Blood centers separate donated blood into component parts, which are then stored for use in medical transfusions as needed.”

At The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the standard preoperative blood order for elective pediatric heart surgery with cariopulmonary bypass is 2 units of FWB and 2 units of packed red blood cells. The FWB is to be used during and immediately after surgery and the components thereafter, if necessary.

The researchers set out to examine the effectiveness of this protocol. They conducted a retrospective study of patient records over a period of 15 years from a surgical registry and blood bank, comparing the cohort of 4111 patients to published reports.

The team defined donor exposures as transfusion requirements for the day of operation and the next postoperative day. All blood products issued were presumed to have been tranfused, and all aliquots from a single donor were counted as a single donor exposure.

Patients were a median age of 94 days and weighed a median of 4.4 kg.

Most (3836) patients received FWB, and 252 received components exclusively when no FWB was available. Twenty-three patients did not receive any blood products. A median of 2 whole blood units was transfused, for a total of 2 donor exposures for the entire cohort.

The researchers found that the youngest patients having complex procedures were exposed to the highest number of donors, while older patients having simpler procedures were exposed to fewer donors.

For example, 72 patients who were a median of 5 days old and underwent truncus arteriosus repair had a median of 4 donor exposures (range, 1-14). And 136 older patients who were a median of 610 days old and underwent fontan completion had a median of 1 donor exposure (range, 0-8).

The researchers concluded that the protocol resulted in fewer donor exposures compared with component use reported in the literature.

Dr Jobes said the risk for disease transmission in pediatric patients is essentially the same as the risk for adults, but it may be more costly for pediatric patients in the long run because infants and young children may live longer with chronic illness stemming from transfusion.

He added, “We hope that our research helps to re-examine current blood storage practice and make whole blood more readily available for pediatric patients.”

He and his colleagues described this research in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. ![]()

Photo by Elise Amendola

Using fresh whole blood (FWB) from single donors for cardiac procedures in children younger than 2 years of age is better than using component blood from multiple donors, researchers say.

FWB reduces the risk of getting transfusion-related illnesses by reducing donor exposures.

“Currently, whole blood is not generally made available to hospitals for use in pediatric heart surgery,” said David R. Jobes, MD, of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania.

“Blood centers separate donated blood into component parts, which are then stored for use in medical transfusions as needed.”

At The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the standard preoperative blood order for elective pediatric heart surgery with cariopulmonary bypass is 2 units of FWB and 2 units of packed red blood cells. The FWB is to be used during and immediately after surgery and the components thereafter, if necessary.

The researchers set out to examine the effectiveness of this protocol. They conducted a retrospective study of patient records over a period of 15 years from a surgical registry and blood bank, comparing the cohort of 4111 patients to published reports.

The team defined donor exposures as transfusion requirements for the day of operation and the next postoperative day. All blood products issued were presumed to have been tranfused, and all aliquots from a single donor were counted as a single donor exposure.

Patients were a median age of 94 days and weighed a median of 4.4 kg.

Most (3836) patients received FWB, and 252 received components exclusively when no FWB was available. Twenty-three patients did not receive any blood products. A median of 2 whole blood units was transfused, for a total of 2 donor exposures for the entire cohort.

The researchers found that the youngest patients having complex procedures were exposed to the highest number of donors, while older patients having simpler procedures were exposed to fewer donors.

For example, 72 patients who were a median of 5 days old and underwent truncus arteriosus repair had a median of 4 donor exposures (range, 1-14). And 136 older patients who were a median of 610 days old and underwent fontan completion had a median of 1 donor exposure (range, 0-8).

The researchers concluded that the protocol resulted in fewer donor exposures compared with component use reported in the literature.

Dr Jobes said the risk for disease transmission in pediatric patients is essentially the same as the risk for adults, but it may be more costly for pediatric patients in the long run because infants and young children may live longer with chronic illness stemming from transfusion.

He added, “We hope that our research helps to re-examine current blood storage practice and make whole blood more readily available for pediatric patients.”

He and his colleagues described this research in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. ![]()

Photo by Elise Amendola

Using fresh whole blood (FWB) from single donors for cardiac procedures in children younger than 2 years of age is better than using component blood from multiple donors, researchers say.

FWB reduces the risk of getting transfusion-related illnesses by reducing donor exposures.

“Currently, whole blood is not generally made available to hospitals for use in pediatric heart surgery,” said David R. Jobes, MD, of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania.

“Blood centers separate donated blood into component parts, which are then stored for use in medical transfusions as needed.”

At The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the standard preoperative blood order for elective pediatric heart surgery with cariopulmonary bypass is 2 units of FWB and 2 units of packed red blood cells. The FWB is to be used during and immediately after surgery and the components thereafter, if necessary.

The researchers set out to examine the effectiveness of this protocol. They conducted a retrospective study of patient records over a period of 15 years from a surgical registry and blood bank, comparing the cohort of 4111 patients to published reports.

The team defined donor exposures as transfusion requirements for the day of operation and the next postoperative day. All blood products issued were presumed to have been tranfused, and all aliquots from a single donor were counted as a single donor exposure.

Patients were a median age of 94 days and weighed a median of 4.4 kg.

Most (3836) patients received FWB, and 252 received components exclusively when no FWB was available. Twenty-three patients did not receive any blood products. A median of 2 whole blood units was transfused, for a total of 2 donor exposures for the entire cohort.

The researchers found that the youngest patients having complex procedures were exposed to the highest number of donors, while older patients having simpler procedures were exposed to fewer donors.

For example, 72 patients who were a median of 5 days old and underwent truncus arteriosus repair had a median of 4 donor exposures (range, 1-14). And 136 older patients who were a median of 610 days old and underwent fontan completion had a median of 1 donor exposure (range, 0-8).

The researchers concluded that the protocol resulted in fewer donor exposures compared with component use reported in the literature.

Dr Jobes said the risk for disease transmission in pediatric patients is essentially the same as the risk for adults, but it may be more costly for pediatric patients in the long run because infants and young children may live longer with chronic illness stemming from transfusion.

He added, “We hope that our research helps to re-examine current blood storage practice and make whole blood more readily available for pediatric patients.”

He and his colleagues described this research in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. ![]()

Study shows importance of VTE screening

Image by Kevin MacKenzie

SEATTLE—Routine screening for venous thromboembolism (VTE) may decrease morbidity and mortality among patients undergoing pneumonectomy for benign or malignant indications, according to researchers.

The group conducted a study that showed the rate of VTE diagnosis was 3 times higher for patients who underwent routine VTE screening post-pneumonectomy than for patients who were tested for VTE only after they exhibited symptoms.

Siva Raja MD, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, presented this finding at the 95th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

He and his colleagues analyzed 112 patients who underwent pneumonectomy for benign and malignant indications and were screened for VTE. The team compared the rate of VTE diagnosis in this group to the rate in a previously published group of 336 similar patients who did not undergo VTE screening.

The rate of in-hospital VTEs in the screened group was almost 3 times higher than the rate in patients who were not screened—8.9% and 3.0%, respectively (P=0.008).

Over the 30-day post-operative period, the rate of VTE for screened patients was more than double the rate for unscreened patients—13% and 5.1%, respectively (P=0.007).

In the screened group, 10 of 112 patients had VTE detected by screening just before discharge, and 4 additional patients developed symptomatic VTE within 30 days despite a negative pre-discharge screen. In all, 20 patients in this group developed a VTE.

In both the screened and unscreened cohorts, the risk of VTE peaked 6 days after surgery and plateaued after 30 days.

“We find that a large proportion (50%) of VTEs occurred prior to the time of discharge, and the risk of developing symptomatic VTE remained elevated for 30 days,” Dr Raja said. “It is possible that the prevalence of VTE may be even higher should a comprehensive serial screening program be initiated.”

Dr Raja also noted that VTEs are a particular problem after pneumonectomy, since these patients often have low pulmonary reserve to withstand the impact of pulmonary embolism.

Indeed, this study showed that post-pneumonectomy patients who developed VTE had worse long-term survival than patients who did not develop clots, although the difference was not statistically significant (hazard ratio=2.1, P=0.08).

Still, Dr Raja said these results suggest that patients undergoing pneumonectomy receive anticoagulants for a longer duration, as well as undergo repeat screening test for VTE even after hospital discharge. ![]()

Image by Kevin MacKenzie

SEATTLE—Routine screening for venous thromboembolism (VTE) may decrease morbidity and mortality among patients undergoing pneumonectomy for benign or malignant indications, according to researchers.

The group conducted a study that showed the rate of VTE diagnosis was 3 times higher for patients who underwent routine VTE screening post-pneumonectomy than for patients who were tested for VTE only after they exhibited symptoms.

Siva Raja MD, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, presented this finding at the 95th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

He and his colleagues analyzed 112 patients who underwent pneumonectomy for benign and malignant indications and were screened for VTE. The team compared the rate of VTE diagnosis in this group to the rate in a previously published group of 336 similar patients who did not undergo VTE screening.

The rate of in-hospital VTEs in the screened group was almost 3 times higher than the rate in patients who were not screened—8.9% and 3.0%, respectively (P=0.008).

Over the 30-day post-operative period, the rate of VTE for screened patients was more than double the rate for unscreened patients—13% and 5.1%, respectively (P=0.007).

In the screened group, 10 of 112 patients had VTE detected by screening just before discharge, and 4 additional patients developed symptomatic VTE within 30 days despite a negative pre-discharge screen. In all, 20 patients in this group developed a VTE.

In both the screened and unscreened cohorts, the risk of VTE peaked 6 days after surgery and plateaued after 30 days.

“We find that a large proportion (50%) of VTEs occurred prior to the time of discharge, and the risk of developing symptomatic VTE remained elevated for 30 days,” Dr Raja said. “It is possible that the prevalence of VTE may be even higher should a comprehensive serial screening program be initiated.”

Dr Raja also noted that VTEs are a particular problem after pneumonectomy, since these patients often have low pulmonary reserve to withstand the impact of pulmonary embolism.

Indeed, this study showed that post-pneumonectomy patients who developed VTE had worse long-term survival than patients who did not develop clots, although the difference was not statistically significant (hazard ratio=2.1, P=0.08).

Still, Dr Raja said these results suggest that patients undergoing pneumonectomy receive anticoagulants for a longer duration, as well as undergo repeat screening test for VTE even after hospital discharge. ![]()

Image by Kevin MacKenzie

SEATTLE—Routine screening for venous thromboembolism (VTE) may decrease morbidity and mortality among patients undergoing pneumonectomy for benign or malignant indications, according to researchers.

The group conducted a study that showed the rate of VTE diagnosis was 3 times higher for patients who underwent routine VTE screening post-pneumonectomy than for patients who were tested for VTE only after they exhibited symptoms.

Siva Raja MD, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, presented this finding at the 95th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

He and his colleagues analyzed 112 patients who underwent pneumonectomy for benign and malignant indications and were screened for VTE. The team compared the rate of VTE diagnosis in this group to the rate in a previously published group of 336 similar patients who did not undergo VTE screening.

The rate of in-hospital VTEs in the screened group was almost 3 times higher than the rate in patients who were not screened—8.9% and 3.0%, respectively (P=0.008).

Over the 30-day post-operative period, the rate of VTE for screened patients was more than double the rate for unscreened patients—13% and 5.1%, respectively (P=0.007).

In the screened group, 10 of 112 patients had VTE detected by screening just before discharge, and 4 additional patients developed symptomatic VTE within 30 days despite a negative pre-discharge screen. In all, 20 patients in this group developed a VTE.

In both the screened and unscreened cohorts, the risk of VTE peaked 6 days after surgery and plateaued after 30 days.

“We find that a large proportion (50%) of VTEs occurred prior to the time of discharge, and the risk of developing symptomatic VTE remained elevated for 30 days,” Dr Raja said. “It is possible that the prevalence of VTE may be even higher should a comprehensive serial screening program be initiated.”

Dr Raja also noted that VTEs are a particular problem after pneumonectomy, since these patients often have low pulmonary reserve to withstand the impact of pulmonary embolism.

Indeed, this study showed that post-pneumonectomy patients who developed VTE had worse long-term survival than patients who did not develop clots, although the difference was not statistically significant (hazard ratio=2.1, P=0.08).

Still, Dr Raja said these results suggest that patients undergoing pneumonectomy receive anticoagulants for a longer duration, as well as undergo repeat screening test for VTE even after hospital discharge. ![]()

FDA approves new drug for hemophilia B

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an intravenous, recombinant, human coagulation factor IX product (Ixinity) for use in patients

with hemophilia B.

The drug is intended to control and prevent bleeding episodes and for perioperative management in adults and children age 12 and older.

Concurrent with the FDA’s approval, Emergent Biosolutions (the company developing Ixinity) launched the Ixinity IXperience Concierge. This resource, which consumers can access by calling 1-855-IXINITY, provides information on the drug.

About Ixinity

Ixinity contains trenonacog alfa, a purified, single-chain glycoprotein derived from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells that has an amino acid sequence comparable to the Thr148 allelic form of plasma-derived factor IX.

No human or animal proteins are added during any stage of manufacturing or formulation of Ixinity. The recombinant factor IX is purified by a chromatography purification process.

The process includes 3 validated steps for virus inactivation and removal. It also includes a validated manufacturing step to reduce the presence of CHO proteins in the final drug product.

Ixinity is contraindicated in patients who have known hypersensitivity to the drug or its excipients, including CHO protein. Hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, may occur following treatment with Ixinity. Patients who receive Ixinity are also at risk of developing nephrotic syndrome and thromboembolism.

Trial data

The FDA approved Ixinity based on results from a phase 1/3 trial of the drug in previously treated adults and children (age 12 and older) with severe to moderately severe (factor IX level < 2%) hemophilia B.

Seventy-seven patients received at least 1 dose of Ixinity. The drug was given as routine prophylaxis or on-demand treatment for bleeding episodes.

Fifty-five patients received treatment for more than 50 exposure days, and 45 received the drug for more than 100 exposure days. The median duration of treatment on study was 16.2 months (range, 2.4-39.6 months) for the routine treatment regimen and 14.1 months (range, 2.3-36.9 months) for the on-demand treatment regimen.

A total of 508 bleeding episodes were treated with Ixinity—286 bleeds for patients on routine treatment and 222 for patients receiving on-demand treatment. A majority of the bleeds (84%) were resolved by 1 or 2 infusions of the drug.

Patients rated hemostatic efficacy at the resolution of a bleed as “excellent” or “good” in 84% of all treated bleeding episodes. “Excellent” was defined as a dramatic response with abrupt pain relief and clear reduction in joint or hemorrhage site size. “Good” was defined as pain relief or reduction in hemorrhage site size that may have required an additional infusion for resolution.

Ixinity also induced hemostasis in patients who underwent major surgical procedures.

The drug exhibited similar pharmacokinetic behavior as nonacog alfa, another licensed recombinant coagulation factor IX product. There was no significant reduction in steady-state factor IX levels or alteration in pharmacokinetic behavior over time with Ixinity.

There were 14 adverse events reported in 6 patients. The most common event, observed in 2.6% of patients, was headache. Other adverse events were asthenia, apathy, depression, dysgeusia, influenza, injection site discomfort, lethargy, and skin rash.

None of the patients developed inhibitors to Ixinity, and there were no reports of thrombotic events or allergic reactions.

For more details on this research, see the full prescribing information for Ixinity, available at www.IXINITY.com. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an intravenous, recombinant, human coagulation factor IX product (Ixinity) for use in patients

with hemophilia B.

The drug is intended to control and prevent bleeding episodes and for perioperative management in adults and children age 12 and older.

Concurrent with the FDA’s approval, Emergent Biosolutions (the company developing Ixinity) launched the Ixinity IXperience Concierge. This resource, which consumers can access by calling 1-855-IXINITY, provides information on the drug.

About Ixinity

Ixinity contains trenonacog alfa, a purified, single-chain glycoprotein derived from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells that has an amino acid sequence comparable to the Thr148 allelic form of plasma-derived factor IX.

No human or animal proteins are added during any stage of manufacturing or formulation of Ixinity. The recombinant factor IX is purified by a chromatography purification process.

The process includes 3 validated steps for virus inactivation and removal. It also includes a validated manufacturing step to reduce the presence of CHO proteins in the final drug product.

Ixinity is contraindicated in patients who have known hypersensitivity to the drug or its excipients, including CHO protein. Hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, may occur following treatment with Ixinity. Patients who receive Ixinity are also at risk of developing nephrotic syndrome and thromboembolism.

Trial data

The FDA approved Ixinity based on results from a phase 1/3 trial of the drug in previously treated adults and children (age 12 and older) with severe to moderately severe (factor IX level < 2%) hemophilia B.

Seventy-seven patients received at least 1 dose of Ixinity. The drug was given as routine prophylaxis or on-demand treatment for bleeding episodes.

Fifty-five patients received treatment for more than 50 exposure days, and 45 received the drug for more than 100 exposure days. The median duration of treatment on study was 16.2 months (range, 2.4-39.6 months) for the routine treatment regimen and 14.1 months (range, 2.3-36.9 months) for the on-demand treatment regimen.

A total of 508 bleeding episodes were treated with Ixinity—286 bleeds for patients on routine treatment and 222 for patients receiving on-demand treatment. A majority of the bleeds (84%) were resolved by 1 or 2 infusions of the drug.

Patients rated hemostatic efficacy at the resolution of a bleed as “excellent” or “good” in 84% of all treated bleeding episodes. “Excellent” was defined as a dramatic response with abrupt pain relief and clear reduction in joint or hemorrhage site size. “Good” was defined as pain relief or reduction in hemorrhage site size that may have required an additional infusion for resolution.

Ixinity also induced hemostasis in patients who underwent major surgical procedures.

The drug exhibited similar pharmacokinetic behavior as nonacog alfa, another licensed recombinant coagulation factor IX product. There was no significant reduction in steady-state factor IX levels or alteration in pharmacokinetic behavior over time with Ixinity.

There were 14 adverse events reported in 6 patients. The most common event, observed in 2.6% of patients, was headache. Other adverse events were asthenia, apathy, depression, dysgeusia, influenza, injection site discomfort, lethargy, and skin rash.

None of the patients developed inhibitors to Ixinity, and there were no reports of thrombotic events or allergic reactions.

For more details on this research, see the full prescribing information for Ixinity, available at www.IXINITY.com. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an intravenous, recombinant, human coagulation factor IX product (Ixinity) for use in patients

with hemophilia B.

The drug is intended to control and prevent bleeding episodes and for perioperative management in adults and children age 12 and older.

Concurrent with the FDA’s approval, Emergent Biosolutions (the company developing Ixinity) launched the Ixinity IXperience Concierge. This resource, which consumers can access by calling 1-855-IXINITY, provides information on the drug.

About Ixinity

Ixinity contains trenonacog alfa, a purified, single-chain glycoprotein derived from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells that has an amino acid sequence comparable to the Thr148 allelic form of plasma-derived factor IX.

No human or animal proteins are added during any stage of manufacturing or formulation of Ixinity. The recombinant factor IX is purified by a chromatography purification process.

The process includes 3 validated steps for virus inactivation and removal. It also includes a validated manufacturing step to reduce the presence of CHO proteins in the final drug product.

Ixinity is contraindicated in patients who have known hypersensitivity to the drug or its excipients, including CHO protein. Hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, may occur following treatment with Ixinity. Patients who receive Ixinity are also at risk of developing nephrotic syndrome and thromboembolism.

Trial data

The FDA approved Ixinity based on results from a phase 1/3 trial of the drug in previously treated adults and children (age 12 and older) with severe to moderately severe (factor IX level < 2%) hemophilia B.

Seventy-seven patients received at least 1 dose of Ixinity. The drug was given as routine prophylaxis or on-demand treatment for bleeding episodes.

Fifty-five patients received treatment for more than 50 exposure days, and 45 received the drug for more than 100 exposure days. The median duration of treatment on study was 16.2 months (range, 2.4-39.6 months) for the routine treatment regimen and 14.1 months (range, 2.3-36.9 months) for the on-demand treatment regimen.

A total of 508 bleeding episodes were treated with Ixinity—286 bleeds for patients on routine treatment and 222 for patients receiving on-demand treatment. A majority of the bleeds (84%) were resolved by 1 or 2 infusions of the drug.

Patients rated hemostatic efficacy at the resolution of a bleed as “excellent” or “good” in 84% of all treated bleeding episodes. “Excellent” was defined as a dramatic response with abrupt pain relief and clear reduction in joint or hemorrhage site size. “Good” was defined as pain relief or reduction in hemorrhage site size that may have required an additional infusion for resolution.

Ixinity also induced hemostasis in patients who underwent major surgical procedures.

The drug exhibited similar pharmacokinetic behavior as nonacog alfa, another licensed recombinant coagulation factor IX product. There was no significant reduction in steady-state factor IX levels or alteration in pharmacokinetic behavior over time with Ixinity.

There were 14 adverse events reported in 6 patients. The most common event, observed in 2.6% of patients, was headache. Other adverse events were asthenia, apathy, depression, dysgeusia, influenza, injection site discomfort, lethargy, and skin rash.

None of the patients developed inhibitors to Ixinity, and there were no reports of thrombotic events or allergic reactions.

For more details on this research, see the full prescribing information for Ixinity, available at www.IXINITY.com. ![]()

Restrictive Transfusion Strategy No Benefit for Cardiac Surgery Patients

Clinical question: Does a restrictive transfusion strategy improve outcomes following nonemergent cardiac surgery?

Bottom line: For patients undergoing cardiac surgery, using a restrictive transfusion strategy with a hemoglobin threshold of 7.5 g/dL does not decrease serious infections or ischemic events and may lead to increased all-cause mortality at 90 days. (LOE = 1b)

Study design: Randomized controlled trial (single-blinded)

Funding source: Government

Allocation: Concealed

Setting: Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis

This is yet another study that compares restrictive and liberal transfusion strategies, this time in a cardiac surgery population. These investigators enrolled patients undergoing nonemergency cardiac surgery (mostly coronary artery bypass grafts or valvular procedures) who had a drop of hemoglobin level to below 9 g/dL following surgery.

Patients were randomized, using concealed allocation, to the restrictive transfusion threshold group (threshold hemoglobin 7.5 g/dL) or liberal transfusion threshold group (threshold hemoglobin 9 g/dL). Patients were masked but physicians and nurses were aware of the group assignments.

In the liberal group, patients received one unit of red cell transfusion immediately after randomization followed by an additional unit if the hemoglobin level remained below or dropped below 9 g/dL again during the hospitalization. In the restrictive group, patients received one unit of red cells only if the hemoglobin level dropped below 7.5 g/dL. An additional unit was then given if hemoglobin remained below or dropped below 7.5 g/dL again during the hospitalization. The 2 groups were similar at baseline and analysis was by intention to treat. Not surprisingly, more patients in the liberal strategy group received transfusions than did those in the restrictive strategy group (95% vs 64%).

For the primary outcome—a composite of sepsis, wound infection, stroke, myocardial infarction, gut infarction, or acute kidney injury within 3 months of randomization—there was no significant difference detected between the 2 groups. However, the restrictive group had a higher mortality rate than the liberal group (4.2% vs 2.6%; P = .045). Although this was a secondary outcome, it is possible that a restrictive strategy may be harmful in this cohort, given that they may have less cardiovascular reserve than the general patient population.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Does a restrictive transfusion strategy improve outcomes following nonemergent cardiac surgery?

Bottom line: For patients undergoing cardiac surgery, using a restrictive transfusion strategy with a hemoglobin threshold of 7.5 g/dL does not decrease serious infections or ischemic events and may lead to increased all-cause mortality at 90 days. (LOE = 1b)

Study design: Randomized controlled trial (single-blinded)

Funding source: Government

Allocation: Concealed

Setting: Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis

This is yet another study that compares restrictive and liberal transfusion strategies, this time in a cardiac surgery population. These investigators enrolled patients undergoing nonemergency cardiac surgery (mostly coronary artery bypass grafts or valvular procedures) who had a drop of hemoglobin level to below 9 g/dL following surgery.

Patients were randomized, using concealed allocation, to the restrictive transfusion threshold group (threshold hemoglobin 7.5 g/dL) or liberal transfusion threshold group (threshold hemoglobin 9 g/dL). Patients were masked but physicians and nurses were aware of the group assignments.

In the liberal group, patients received one unit of red cell transfusion immediately after randomization followed by an additional unit if the hemoglobin level remained below or dropped below 9 g/dL again during the hospitalization. In the restrictive group, patients received one unit of red cells only if the hemoglobin level dropped below 7.5 g/dL. An additional unit was then given if hemoglobin remained below or dropped below 7.5 g/dL again during the hospitalization. The 2 groups were similar at baseline and analysis was by intention to treat. Not surprisingly, more patients in the liberal strategy group received transfusions than did those in the restrictive strategy group (95% vs 64%).

For the primary outcome—a composite of sepsis, wound infection, stroke, myocardial infarction, gut infarction, or acute kidney injury within 3 months of randomization—there was no significant difference detected between the 2 groups. However, the restrictive group had a higher mortality rate than the liberal group (4.2% vs 2.6%; P = .045). Although this was a secondary outcome, it is possible that a restrictive strategy may be harmful in this cohort, given that they may have less cardiovascular reserve than the general patient population.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Does a restrictive transfusion strategy improve outcomes following nonemergent cardiac surgery?

Bottom line: For patients undergoing cardiac surgery, using a restrictive transfusion strategy with a hemoglobin threshold of 7.5 g/dL does not decrease serious infections or ischemic events and may lead to increased all-cause mortality at 90 days. (LOE = 1b)

Study design: Randomized controlled trial (single-blinded)

Funding source: Government

Allocation: Concealed

Setting: Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis

This is yet another study that compares restrictive and liberal transfusion strategies, this time in a cardiac surgery population. These investigators enrolled patients undergoing nonemergency cardiac surgery (mostly coronary artery bypass grafts or valvular procedures) who had a drop of hemoglobin level to below 9 g/dL following surgery.

Patients were randomized, using concealed allocation, to the restrictive transfusion threshold group (threshold hemoglobin 7.5 g/dL) or liberal transfusion threshold group (threshold hemoglobin 9 g/dL). Patients were masked but physicians and nurses were aware of the group assignments.

In the liberal group, patients received one unit of red cell transfusion immediately after randomization followed by an additional unit if the hemoglobin level remained below or dropped below 9 g/dL again during the hospitalization. In the restrictive group, patients received one unit of red cells only if the hemoglobin level dropped below 7.5 g/dL. An additional unit was then given if hemoglobin remained below or dropped below 7.5 g/dL again during the hospitalization. The 2 groups were similar at baseline and analysis was by intention to treat. Not surprisingly, more patients in the liberal strategy group received transfusions than did those in the restrictive strategy group (95% vs 64%).

For the primary outcome—a composite of sepsis, wound infection, stroke, myocardial infarction, gut infarction, or acute kidney injury within 3 months of randomization—there was no significant difference detected between the 2 groups. However, the restrictive group had a higher mortality rate than the liberal group (4.2% vs 2.6%; P = .045). Although this was a secondary outcome, it is possible that a restrictive strategy may be harmful in this cohort, given that they may have less cardiovascular reserve than the general patient population.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke Decreases Mortality

Clinical question: Does endovascular treatment improve outcomes for patients with acute ischemic stroke?

Bottom line: For patients with acute ischemic stroke and imaging that suggests a proximal artery occlusion with evidence of good collateral circulation, the use of rapid endovascular treatment improves functional outcomes and reduces mortality. (LOE = 1b)

Study design: Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding source: Industry

Allocation: Concealed

Setting: Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

The recent MR CLEAN study showed improved functional outcomes with the use of endovascular therapy for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke (N Engl J Med 2015;372:11-20).

In this study, investigators enrolled patients with acute disabling ischemic strokes and computed tomographic evidence of a small infarct core, an occluded proximal artery in the anterior circulation, and moderate-to-good collateral circulation. Patients were randomized, using concealed allocation, to receive either usual care or usual care plus rapid endovascular treatment with the use of mechanical thrombectomy and retrievable stents.

The 2 groups had similar baseline characteristics with a mean age of 70 years and a median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 16 to 17. The median time from stroke onset to reperfusion was 4 hours in the intervention group. The trial was stopped early because of the efficacy of the endovascular therapy. The primary outcome was a common odds ratio, indicating the odds of improvement by 1 point on the modified Rankin scale of 0 to 6 (0 = no symptoms, 1–2 = slight disability, 6 = death). This ratio favored the intervention (common odds ratio 2.6, 95% CI 1.7-3.8; P < .001).

Overall, at 90-day follow-up, the intervention group had a greater proportion of patients with a modified Rankin score of 0–2 (53% vs. 29%; P < .001), as well as decreased mortality (10% vs 19% in control group, P = .04). There was no difference between the 2 groups in the rate of symptomatic intracerebral bleeds.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Does endovascular treatment improve outcomes for patients with acute ischemic stroke?

Bottom line: For patients with acute ischemic stroke and imaging that suggests a proximal artery occlusion with evidence of good collateral circulation, the use of rapid endovascular treatment improves functional outcomes and reduces mortality. (LOE = 1b)

Study design: Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding source: Industry

Allocation: Concealed

Setting: Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

The recent MR CLEAN study showed improved functional outcomes with the use of endovascular therapy for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke (N Engl J Med 2015;372:11-20).

In this study, investigators enrolled patients with acute disabling ischemic strokes and computed tomographic evidence of a small infarct core, an occluded proximal artery in the anterior circulation, and moderate-to-good collateral circulation. Patients were randomized, using concealed allocation, to receive either usual care or usual care plus rapid endovascular treatment with the use of mechanical thrombectomy and retrievable stents.

The 2 groups had similar baseline characteristics with a mean age of 70 years and a median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 16 to 17. The median time from stroke onset to reperfusion was 4 hours in the intervention group. The trial was stopped early because of the efficacy of the endovascular therapy. The primary outcome was a common odds ratio, indicating the odds of improvement by 1 point on the modified Rankin scale of 0 to 6 (0 = no symptoms, 1–2 = slight disability, 6 = death). This ratio favored the intervention (common odds ratio 2.6, 95% CI 1.7-3.8; P < .001).

Overall, at 90-day follow-up, the intervention group had a greater proportion of patients with a modified Rankin score of 0–2 (53% vs. 29%; P < .001), as well as decreased mortality (10% vs 19% in control group, P = .04). There was no difference between the 2 groups in the rate of symptomatic intracerebral bleeds.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Does endovascular treatment improve outcomes for patients with acute ischemic stroke?

Bottom line: For patients with acute ischemic stroke and imaging that suggests a proximal artery occlusion with evidence of good collateral circulation, the use of rapid endovascular treatment improves functional outcomes and reduces mortality. (LOE = 1b)

Study design: Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding source: Industry

Allocation: Concealed

Setting: Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

The recent MR CLEAN study showed improved functional outcomes with the use of endovascular therapy for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke (N Engl J Med 2015;372:11-20).

In this study, investigators enrolled patients with acute disabling ischemic strokes and computed tomographic evidence of a small infarct core, an occluded proximal artery in the anterior circulation, and moderate-to-good collateral circulation. Patients were randomized, using concealed allocation, to receive either usual care or usual care plus rapid endovascular treatment with the use of mechanical thrombectomy and retrievable stents.

The 2 groups had similar baseline characteristics with a mean age of 70 years and a median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 16 to 17. The median time from stroke onset to reperfusion was 4 hours in the intervention group. The trial was stopped early because of the efficacy of the endovascular therapy. The primary outcome was a common odds ratio, indicating the odds of improvement by 1 point on the modified Rankin scale of 0 to 6 (0 = no symptoms, 1–2 = slight disability, 6 = death). This ratio favored the intervention (common odds ratio 2.6, 95% CI 1.7-3.8; P < .001).

Overall, at 90-day follow-up, the intervention group had a greater proportion of patients with a modified Rankin score of 0–2 (53% vs. 29%; P < .001), as well as decreased mortality (10% vs 19% in control group, P = .04). There was no difference between the 2 groups in the rate of symptomatic intracerebral bleeds.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

NASPAG: Migraines don’t always preclude combined OCs

ORLANDO– Most adolescent girls who report having headaches – including some of those who report migraines with aura – can safely use combined oral contraceptive pills, according to Dr. Sari Kives.

The available literature suggests that there is some resistance to prescribing such contraception for adolescents with headaches, but most adolescents don’t have the types of headaches that are of concern, Dr. Kives of the University of Toronto said at the annual meeting of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

owever, it is important to get a good characterization of the headaches, keeping in mind that teens may have difficulty relating their symptoms, she said.

“It’s important to understand what the headache actually is. Is it a tension headache, which is by far the most common headache you will see in adolescents?” she said, noting that menstrual migraines and classical migraines are less common in adolescents.

Menstrual migraines account for about 7%-8% of migraines, occur 2-3 days before menses, can last throughout the period, don’t occur any other time of the month, and can be quite debilitating. They usually are secondary to estrogen withdrawal, Dr. Kives said, adding that a decade ago, add-back estrogen was commonly given during the week off of oral contraceptives in those with menstrual headaches.

Now it is common practice to use continuous pills or extended-cycle pills, she said, explaining that eliminating the estrogen fluctuation improves the headaches.

Classical migraines also occur commonly in adolescent girls. Some may include focal neurological symptoms that may be triggered by hormonal changes, stress, certain foods and beverages, certain scents or fumes, fatigue, hunger, or trauma.

It is important to ask about such symptoms, Dr. Kives said.

“And that’s probably the most important question you can ask. For me, a focal neurological symptom is, ‘I go blind in my left eye. I lose sensation in my right arm,’ ” she said, providing examples.

Some symptoms are characteristic of “atypical aura,” and some are associated with “typical aura” – an important distinction when determining whether combined OCs are safe for a given patient.

Atypical aura usually has sudden unilateral onset and lasts more than 30-60 minutes. Headache may or may not be present, and visual symptoms may include loss of vision, amaurosis fugax (painless transient monocular visual loss), and visual field anomaly. Sensory and motor symptoms can include lower limb anesthesia or hypoesthesia (decrease in sensation).

Typical aura has more progressive onset, lasts less than an hour, and precedes migraine. Patients may experience bilateral scintillating scotoma, fortification spectra, and blurred vision. These are usually limited to visual symptoms, Dr. Kives said, but sensory and motor symptoms can occur. They tend to occur in relation to the visual symptoms, and may affect the upper limbs, mouth, and tongue – causing tingling or pinching sensations.

Individuals who have migraine with aura account for only about 20% of those with migraine headaches, and the vast majority are going to have visual aura.

“They can have sensory and motor symptoms, but the visual ones are the ones where you have to be very specific,” she said, noting that in her experience, 99% of cases are visual.

“If it’s a short visual aura, less than an hour, and it’s not repetitive, I will consider an oral contraceptive pill in this group of patients, but you have to balance it against what their history sounds like,” she said.

Typically, combined OCs are contraindicated in patients with migraine with aura because of an increased risk of cerebrovascular accident, but in Canada, guidelines provide allowances for this “unique group of individuals with migraines with aura that are limited to visual symptoms and that last less than 1 hour,” she said.

Remember that photophobia, phonophobia, nausea and vomiting, visual blurring, and generalized visual spots/flashing lights do not constitute aura, she said.

This is important, because using too stringent a definition of “migraine with aura” will leave a substantial number of individuals with limited contraceptive options, particularly options that are effective and promote cycle control and compliance, she said.

Although there is a definite risk associated with combined OCs in those with migraine with aura – with an added risk in those who smoke, the risks are low in adolescents, compared with older patients.

“The adult women who walks in with hypertension, or who is a smoker who gets oral contraception – that is a very different patient than the 14-year-old who says, ‘I may get flashing lights before my headache, but not on a regular basis.’ Those are completely different entity patients, in my opinion,” Dr. Kives said.

If she does prescribe combined OCs for an adolescent with migraines, she advises the patient to stop the pills if the headaches get worse, she said. In many cases, however, headaches improve, because they were menstrual migraines and not classical migraines, she said, adding that “improvement in headaches is a reassuring sign.” The bottom line, Dr. Kives said, is that migraine without aura doesn’t preclude prescribing of any contraceptive options in adolescents, and that migraine with aura is a relative contraindication; low-dose combined oral contraceptive pills are safe for those with migraine with aura that primarily includes visual symptoms lasting less than an hour.

However, the risk of cerebrovascular accidents is increased in those with migraines, so other risk factors, such as family history, obesity, hypertension, and smoking, should be considered.

“If they have no other risk factors, their risk probably is quite low,” Dr. Kives said.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO– Most adolescent girls who report having headaches – including some of those who report migraines with aura – can safely use combined oral contraceptive pills, according to Dr. Sari Kives.

The available literature suggests that there is some resistance to prescribing such contraception for adolescents with headaches, but most adolescents don’t have the types of headaches that are of concern, Dr. Kives of the University of Toronto said at the annual meeting of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

owever, it is important to get a good characterization of the headaches, keeping in mind that teens may have difficulty relating their symptoms, she said.

“It’s important to understand what the headache actually is. Is it a tension headache, which is by far the most common headache you will see in adolescents?” she said, noting that menstrual migraines and classical migraines are less common in adolescents.

Menstrual migraines account for about 7%-8% of migraines, occur 2-3 days before menses, can last throughout the period, don’t occur any other time of the month, and can be quite debilitating. They usually are secondary to estrogen withdrawal, Dr. Kives said, adding that a decade ago, add-back estrogen was commonly given during the week off of oral contraceptives in those with menstrual headaches.

Now it is common practice to use continuous pills or extended-cycle pills, she said, explaining that eliminating the estrogen fluctuation improves the headaches.

Classical migraines also occur commonly in adolescent girls. Some may include focal neurological symptoms that may be triggered by hormonal changes, stress, certain foods and beverages, certain scents or fumes, fatigue, hunger, or trauma.

It is important to ask about such symptoms, Dr. Kives said.

“And that’s probably the most important question you can ask. For me, a focal neurological symptom is, ‘I go blind in my left eye. I lose sensation in my right arm,’ ” she said, providing examples.

Some symptoms are characteristic of “atypical aura,” and some are associated with “typical aura” – an important distinction when determining whether combined OCs are safe for a given patient.

Atypical aura usually has sudden unilateral onset and lasts more than 30-60 minutes. Headache may or may not be present, and visual symptoms may include loss of vision, amaurosis fugax (painless transient monocular visual loss), and visual field anomaly. Sensory and motor symptoms can include lower limb anesthesia or hypoesthesia (decrease in sensation).

Typical aura has more progressive onset, lasts less than an hour, and precedes migraine. Patients may experience bilateral scintillating scotoma, fortification spectra, and blurred vision. These are usually limited to visual symptoms, Dr. Kives said, but sensory and motor symptoms can occur. They tend to occur in relation to the visual symptoms, and may affect the upper limbs, mouth, and tongue – causing tingling or pinching sensations.

Individuals who have migraine with aura account for only about 20% of those with migraine headaches, and the vast majority are going to have visual aura.

“They can have sensory and motor symptoms, but the visual ones are the ones where you have to be very specific,” she said, noting that in her experience, 99% of cases are visual.

“If it’s a short visual aura, less than an hour, and it’s not repetitive, I will consider an oral contraceptive pill in this group of patients, but you have to balance it against what their history sounds like,” she said.

Typically, combined OCs are contraindicated in patients with migraine with aura because of an increased risk of cerebrovascular accident, but in Canada, guidelines provide allowances for this “unique group of individuals with migraines with aura that are limited to visual symptoms and that last less than 1 hour,” she said.

Remember that photophobia, phonophobia, nausea and vomiting, visual blurring, and generalized visual spots/flashing lights do not constitute aura, she said.

This is important, because using too stringent a definition of “migraine with aura” will leave a substantial number of individuals with limited contraceptive options, particularly options that are effective and promote cycle control and compliance, she said.

Although there is a definite risk associated with combined OCs in those with migraine with aura – with an added risk in those who smoke, the risks are low in adolescents, compared with older patients.

“The adult women who walks in with hypertension, or who is a smoker who gets oral contraception – that is a very different patient than the 14-year-old who says, ‘I may get flashing lights before my headache, but not on a regular basis.’ Those are completely different entity patients, in my opinion,” Dr. Kives said.

If she does prescribe combined OCs for an adolescent with migraines, she advises the patient to stop the pills if the headaches get worse, she said. In many cases, however, headaches improve, because they were menstrual migraines and not classical migraines, she said, adding that “improvement in headaches is a reassuring sign.” The bottom line, Dr. Kives said, is that migraine without aura doesn’t preclude prescribing of any contraceptive options in adolescents, and that migraine with aura is a relative contraindication; low-dose combined oral contraceptive pills are safe for those with migraine with aura that primarily includes visual symptoms lasting less than an hour.