User login

Stomach pain chalked up to flu; patient suffers fatal cardiac event ... More

Stomach pain chalked up to flu; patient suffers fatal cardiac event

A 40-YEAR-OLD MAN went to the emergency department (ED) after 2 days of stomach discomfort. The ED physician who evaluated him released him after 4 or 5 hours without testing for levels of troponin or other cardiac enzymes. The patient’s discomfort continued, and about 3 days later, he told his wife to call 911. He was transported to the ED but did not survive.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The decedent had been suffering from an acute cardiac event during the first ED visit. Testing to rule out cardiac problems should have been performed.

THE DEFENSE The patient had been suffering from a stomach flu during his initial ED visit. Any testing performed at that time would have been normal. The patient’s death was unrelated to the symptoms he was experiencing when he was first seen.

VERDICT $4 million Alabama verdict.

COMMENT Many questions come to mind with this case: How careful was the history? Did the patient’s discomfort get worse with activity? What were the characteristics of his pain? What were the patient’s cardiac risk factors? A colleague of mine missed a very similar case several years ago in a 67-year-old. The patient even had vomiting and diarrhea, but clearly had a myocardial infarction when diagnosed a few days later.

Follow-up failure on PSA results costs patient valuable Tx time

A PATIENT AT A GROUP PRACTICE underwent prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening, which revealed an abnormal result (4.1 ng/mL). The physician circled this value on the lab report, wrote, “Discuss next visit,” and placed the report in the patient’s chart. However, the patient switched to another physician in the group and was not told of the abnormal result for more than 2 years. When the patient went to a medical center for back pain, magnetic resonance imaging of his spine revealed the presence of cancer in his spine, shoulder blades, pelvis, and ribs. A PSA test performed at that time came back at 100 ng/mL. Two days later, a biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of prostate cancer (Gleason score, 9).

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM In addition to failing to inform the patient of his abnormal PSA test result, the physician did not perform digital rectal exams.

THE DEFENSE Earlier treatment would not have made a difference in the outcome.

VERDICT $934,000 Florida verdict.

COMMENT If you order a PSA, you must follow up on it. When a patient transfers to your care, be sure to obtain and review past testing and provide follow-up on abnormal results. We now send all test results directly to patients so they can serve as a safety check for their own care. Despite fears of being inundated with calls, most organizations that have instituted such a policy have not turned back.

Stomach pain chalked up to flu; patient suffers fatal cardiac event

A 40-YEAR-OLD MAN went to the emergency department (ED) after 2 days of stomach discomfort. The ED physician who evaluated him released him after 4 or 5 hours without testing for levels of troponin or other cardiac enzymes. The patient’s discomfort continued, and about 3 days later, he told his wife to call 911. He was transported to the ED but did not survive.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The decedent had been suffering from an acute cardiac event during the first ED visit. Testing to rule out cardiac problems should have been performed.

THE DEFENSE The patient had been suffering from a stomach flu during his initial ED visit. Any testing performed at that time would have been normal. The patient’s death was unrelated to the symptoms he was experiencing when he was first seen.

VERDICT $4 million Alabama verdict.

COMMENT Many questions come to mind with this case: How careful was the history? Did the patient’s discomfort get worse with activity? What were the characteristics of his pain? What were the patient’s cardiac risk factors? A colleague of mine missed a very similar case several years ago in a 67-year-old. The patient even had vomiting and diarrhea, but clearly had a myocardial infarction when diagnosed a few days later.

Follow-up failure on PSA results costs patient valuable Tx time

A PATIENT AT A GROUP PRACTICE underwent prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening, which revealed an abnormal result (4.1 ng/mL). The physician circled this value on the lab report, wrote, “Discuss next visit,” and placed the report in the patient’s chart. However, the patient switched to another physician in the group and was not told of the abnormal result for more than 2 years. When the patient went to a medical center for back pain, magnetic resonance imaging of his spine revealed the presence of cancer in his spine, shoulder blades, pelvis, and ribs. A PSA test performed at that time came back at 100 ng/mL. Two days later, a biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of prostate cancer (Gleason score, 9).

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM In addition to failing to inform the patient of his abnormal PSA test result, the physician did not perform digital rectal exams.

THE DEFENSE Earlier treatment would not have made a difference in the outcome.

VERDICT $934,000 Florida verdict.

COMMENT If you order a PSA, you must follow up on it. When a patient transfers to your care, be sure to obtain and review past testing and provide follow-up on abnormal results. We now send all test results directly to patients so they can serve as a safety check for their own care. Despite fears of being inundated with calls, most organizations that have instituted such a policy have not turned back.

Stomach pain chalked up to flu; patient suffers fatal cardiac event

A 40-YEAR-OLD MAN went to the emergency department (ED) after 2 days of stomach discomfort. The ED physician who evaluated him released him after 4 or 5 hours without testing for levels of troponin or other cardiac enzymes. The patient’s discomfort continued, and about 3 days later, he told his wife to call 911. He was transported to the ED but did not survive.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The decedent had been suffering from an acute cardiac event during the first ED visit. Testing to rule out cardiac problems should have been performed.

THE DEFENSE The patient had been suffering from a stomach flu during his initial ED visit. Any testing performed at that time would have been normal. The patient’s death was unrelated to the symptoms he was experiencing when he was first seen.

VERDICT $4 million Alabama verdict.

COMMENT Many questions come to mind with this case: How careful was the history? Did the patient’s discomfort get worse with activity? What were the characteristics of his pain? What were the patient’s cardiac risk factors? A colleague of mine missed a very similar case several years ago in a 67-year-old. The patient even had vomiting and diarrhea, but clearly had a myocardial infarction when diagnosed a few days later.

Follow-up failure on PSA results costs patient valuable Tx time

A PATIENT AT A GROUP PRACTICE underwent prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening, which revealed an abnormal result (4.1 ng/mL). The physician circled this value on the lab report, wrote, “Discuss next visit,” and placed the report in the patient’s chart. However, the patient switched to another physician in the group and was not told of the abnormal result for more than 2 years. When the patient went to a medical center for back pain, magnetic resonance imaging of his spine revealed the presence of cancer in his spine, shoulder blades, pelvis, and ribs. A PSA test performed at that time came back at 100 ng/mL. Two days later, a biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of prostate cancer (Gleason score, 9).

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM In addition to failing to inform the patient of his abnormal PSA test result, the physician did not perform digital rectal exams.

THE DEFENSE Earlier treatment would not have made a difference in the outcome.

VERDICT $934,000 Florida verdict.

COMMENT If you order a PSA, you must follow up on it. When a patient transfers to your care, be sure to obtain and review past testing and provide follow-up on abnormal results. We now send all test results directly to patients so they can serve as a safety check for their own care. Despite fears of being inundated with calls, most organizations that have instituted such a policy have not turned back.

What is the most effective topical treatment for allergic conjunctivitis?

Topical antihistamines and topical mast cell stabilizers appear to reduce conjunctival injection and itching effectively. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are also effective, but may sting on application (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both of these treatments relieve redness and itching

A 2004 systematic review of 40 RCTs (total N not provided) assessed the efficacy of topical treatment with mast cell stabilizers and antihistamines, comparing each with the other and placebo.1 Eleven trials that included 899 children and adults compared mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, nedocromil, and lodoxamide tromethamine) with placebo. Follow-up periods ranged from 4 to 9 weeks.

Because of study heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used and showed that topical mast cell stabilizers relieved symptoms (ocular itching, burning, and lacrimation) 4.9 times more effectively than placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5-9.6). Possible publication bias was cited as a limitation.

In the same systematic review, 9 RCTs with 313 patients compared topical antihistamines (levocabastine, azelastine hydrochloride, emedastine, and antazoline phosphate) with placebo. Signs and symptoms (itching, redness, burning, and swelling) were graded using symptom severity scales. Follow-up ranged from 30 minutes to 24 hours. A meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with these scores. Most individual studies, however, showed improvement in the cardinal symptom of itchiness.

Finally, 8 RCTs compared topical mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, lodoxamide, and nedocromil sodium) with levocabastine, a topical antihistamine. Two RCTs with 74 patients had follow-up periods of 15 minutes to 4 hours; the remaining 6 RCTs with 473 patients had follow-up periods of 14 days to 4 months. Subjective scoring of symptoms was done in 7 of the 8 studies.

Scores between treatment groups were reported as not statistically significant in the 6 longer-term studies. Meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with measures. The 2 short-term studies reported a statistically significant reduction in itching and redness (P<.05) in patients treated with the antihistamine (data not provided).

NSAIDs relieve itching but may sting when applied

A 2007 meta-analysis of 8 RCTs compared topical NSAIDs (ketorolac, diclofenac, aspirin, or steroid) with placebo for treating isolated allergic conjunctivitis in 712 children and adults.2 Primary outcomes were measured as subjective reductions in conjunctival injection and itching measured at 2 to 6 weeks using a 0-to-3 severity scale.

Topical NSAIDs produced significantly greater relief of conjunctival itching (4 trials, N=231; mean difference [MD]=-0.54; 95% CI, -0.84 to -0.24) and conjunctival injection (4 trials, N=208; MD=-0.51; 95% CI, -0.97 to -0.05). NSAIDs weren’t superior to placebo in treating other ocular symptoms of eyelid swelling, ocular burning, photophobia, or foreign body sensation, and they had a higher rate of stinging on application (odds ratio=4.0; 95% CI, 2.7-5.9).

Guideline recommends topical antihistamines or mast cell stabilizers

The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s 2012 evidence-based guideline recommends treating allergic conjunctivitis with topical antihistamines (Level A-1 evidence, defined as important evidence supported by at least one RCT or a meta-analysis) and using topical mast cell stabilizers if the condition is recurrent.3

1. Owen CG, Shah A, Henshaw K, et al. Topical treatments for seasonal allergic conjunctivitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and effectiveness. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:451-456.

2. Swamy BN, Chilov M, McClellan K, et al. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in allergic conjunctivitis: meta-analysis of randomized trial data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:311–319.

3. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Conjunctivitis Summary Benchmarks for Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. American Academy of Ophthalmology Web site. Available at: http://one.aao.org/summary-benchmark-detail/conjunctivitis-summary-benchmark--october-2012. Accessed October 18, 2013.

Topical antihistamines and topical mast cell stabilizers appear to reduce conjunctival injection and itching effectively. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are also effective, but may sting on application (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both of these treatments relieve redness and itching

A 2004 systematic review of 40 RCTs (total N not provided) assessed the efficacy of topical treatment with mast cell stabilizers and antihistamines, comparing each with the other and placebo.1 Eleven trials that included 899 children and adults compared mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, nedocromil, and lodoxamide tromethamine) with placebo. Follow-up periods ranged from 4 to 9 weeks.

Because of study heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used and showed that topical mast cell stabilizers relieved symptoms (ocular itching, burning, and lacrimation) 4.9 times more effectively than placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5-9.6). Possible publication bias was cited as a limitation.

In the same systematic review, 9 RCTs with 313 patients compared topical antihistamines (levocabastine, azelastine hydrochloride, emedastine, and antazoline phosphate) with placebo. Signs and symptoms (itching, redness, burning, and swelling) were graded using symptom severity scales. Follow-up ranged from 30 minutes to 24 hours. A meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with these scores. Most individual studies, however, showed improvement in the cardinal symptom of itchiness.

Finally, 8 RCTs compared topical mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, lodoxamide, and nedocromil sodium) with levocabastine, a topical antihistamine. Two RCTs with 74 patients had follow-up periods of 15 minutes to 4 hours; the remaining 6 RCTs with 473 patients had follow-up periods of 14 days to 4 months. Subjective scoring of symptoms was done in 7 of the 8 studies.

Scores between treatment groups were reported as not statistically significant in the 6 longer-term studies. Meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with measures. The 2 short-term studies reported a statistically significant reduction in itching and redness (P<.05) in patients treated with the antihistamine (data not provided).

NSAIDs relieve itching but may sting when applied

A 2007 meta-analysis of 8 RCTs compared topical NSAIDs (ketorolac, diclofenac, aspirin, or steroid) with placebo for treating isolated allergic conjunctivitis in 712 children and adults.2 Primary outcomes were measured as subjective reductions in conjunctival injection and itching measured at 2 to 6 weeks using a 0-to-3 severity scale.

Topical NSAIDs produced significantly greater relief of conjunctival itching (4 trials, N=231; mean difference [MD]=-0.54; 95% CI, -0.84 to -0.24) and conjunctival injection (4 trials, N=208; MD=-0.51; 95% CI, -0.97 to -0.05). NSAIDs weren’t superior to placebo in treating other ocular symptoms of eyelid swelling, ocular burning, photophobia, or foreign body sensation, and they had a higher rate of stinging on application (odds ratio=4.0; 95% CI, 2.7-5.9).

Guideline recommends topical antihistamines or mast cell stabilizers

The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s 2012 evidence-based guideline recommends treating allergic conjunctivitis with topical antihistamines (Level A-1 evidence, defined as important evidence supported by at least one RCT or a meta-analysis) and using topical mast cell stabilizers if the condition is recurrent.3

Topical antihistamines and topical mast cell stabilizers appear to reduce conjunctival injection and itching effectively. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are also effective, but may sting on application (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both of these treatments relieve redness and itching

A 2004 systematic review of 40 RCTs (total N not provided) assessed the efficacy of topical treatment with mast cell stabilizers and antihistamines, comparing each with the other and placebo.1 Eleven trials that included 899 children and adults compared mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, nedocromil, and lodoxamide tromethamine) with placebo. Follow-up periods ranged from 4 to 9 weeks.

Because of study heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used and showed that topical mast cell stabilizers relieved symptoms (ocular itching, burning, and lacrimation) 4.9 times more effectively than placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5-9.6). Possible publication bias was cited as a limitation.

In the same systematic review, 9 RCTs with 313 patients compared topical antihistamines (levocabastine, azelastine hydrochloride, emedastine, and antazoline phosphate) with placebo. Signs and symptoms (itching, redness, burning, and swelling) were graded using symptom severity scales. Follow-up ranged from 30 minutes to 24 hours. A meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with these scores. Most individual studies, however, showed improvement in the cardinal symptom of itchiness.

Finally, 8 RCTs compared topical mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, lodoxamide, and nedocromil sodium) with levocabastine, a topical antihistamine. Two RCTs with 74 patients had follow-up periods of 15 minutes to 4 hours; the remaining 6 RCTs with 473 patients had follow-up periods of 14 days to 4 months. Subjective scoring of symptoms was done in 7 of the 8 studies.

Scores between treatment groups were reported as not statistically significant in the 6 longer-term studies. Meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with measures. The 2 short-term studies reported a statistically significant reduction in itching and redness (P<.05) in patients treated with the antihistamine (data not provided).

NSAIDs relieve itching but may sting when applied

A 2007 meta-analysis of 8 RCTs compared topical NSAIDs (ketorolac, diclofenac, aspirin, or steroid) with placebo for treating isolated allergic conjunctivitis in 712 children and adults.2 Primary outcomes were measured as subjective reductions in conjunctival injection and itching measured at 2 to 6 weeks using a 0-to-3 severity scale.

Topical NSAIDs produced significantly greater relief of conjunctival itching (4 trials, N=231; mean difference [MD]=-0.54; 95% CI, -0.84 to -0.24) and conjunctival injection (4 trials, N=208; MD=-0.51; 95% CI, -0.97 to -0.05). NSAIDs weren’t superior to placebo in treating other ocular symptoms of eyelid swelling, ocular burning, photophobia, or foreign body sensation, and they had a higher rate of stinging on application (odds ratio=4.0; 95% CI, 2.7-5.9).

Guideline recommends topical antihistamines or mast cell stabilizers

The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s 2012 evidence-based guideline recommends treating allergic conjunctivitis with topical antihistamines (Level A-1 evidence, defined as important evidence supported by at least one RCT or a meta-analysis) and using topical mast cell stabilizers if the condition is recurrent.3

1. Owen CG, Shah A, Henshaw K, et al. Topical treatments for seasonal allergic conjunctivitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and effectiveness. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:451-456.

2. Swamy BN, Chilov M, McClellan K, et al. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in allergic conjunctivitis: meta-analysis of randomized trial data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:311–319.

3. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Conjunctivitis Summary Benchmarks for Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. American Academy of Ophthalmology Web site. Available at: http://one.aao.org/summary-benchmark-detail/conjunctivitis-summary-benchmark--october-2012. Accessed October 18, 2013.

1. Owen CG, Shah A, Henshaw K, et al. Topical treatments for seasonal allergic conjunctivitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and effectiveness. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:451-456.

2. Swamy BN, Chilov M, McClellan K, et al. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in allergic conjunctivitis: meta-analysis of randomized trial data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:311–319.

3. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Conjunctivitis Summary Benchmarks for Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. American Academy of Ophthalmology Web site. Available at: http://one.aao.org/summary-benchmark-detail/conjunctivitis-summary-benchmark--october-2012. Accessed October 18, 2013.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Consider These Medications to Help Patients Stay Sober

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider prescribing oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) for patients with alcohol use disorder who wish to maintain abstinence after a brief period of detoxification.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a meta-analysis of 95 randomized controlled trials.1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Your patient, a 42-year-old man with alcohol use disorder (AUD), detoxifies from alcohol during a recent hospitalization. He doesn’t want to resume drinking but reports frequent cravings. Are there any medications you can prescribe to help prevent relapse?

Excessive alcohol consumption is responsible for one of every 10 deaths among US adults ages 20 to 64.2 About 20% to 36% of patients seen in a primary care office have AUD.3 Up to 70% of people who quit with psychosocial support alone will relapse.3

The US Preventive Services Task Force gives a grade B recommendation to screening all adults for AUD, indicating that clinicians should provide this service.4 For patients with AUD who wish to abstain but struggle with cravings and relapse, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) recommends considering medication as an adjunct to brief behavioral counseling.5

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Evidence shows naltrexone can prevent a return to drinking

In a meta-analysis, Jonas et al1 reviewed 123 studies (N = 22,803) of pharmacotherapy for AUD. After excluding 28 studies (seven were the only study of a given drug, one was a prospective cohort, and 20 had insufficient data), 95 randomized controlled trials were included in the analysis. Twenty-two were placebo-controlled for acamprosate (1,000 to 3,000 mg/d), 44 for naltrexone (50 mg/d oral, 100 mg/d oral, or injectable) and four compared the two drugs. Additional studies evaluated disulfiram as well as 23 other off-label medications, such as valproic acid and topiramate.

Two investigators independently reviewed the studies, checking for completeness and accuracy. Studies were also analyzed for bias using predefined criteria; those with high or unclear risk for bias were excluded from the main analysis but included in the sensitivity analysis. Funnel plots showed no evidence of publication bias.

Participants were primarily recruited as inpatients, and in most studies the mean age was in the 40s. Most patients were diagnosed with alcohol dependence based on criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR); this diagnosis translates to likely moderate to severe AUD in DSM-5. Prior to starting medications, participants underwent detoxification or achieved at least three days of sobriety. Most studies included psychosocial intervention in addition to medication, but the types of intervention varied. The duration of the trials ranged from 12 to 52 weeks.

Researchers analyzed five drinking outcomes—return to any drinking, return to heavy drinking (defined as ≥ 4 drinks/d for women and ≥ 5 drinks/d for men), number of drinking days, number of heavy drinking days, and drinks per drinking day. They also evaluated health outcomes (accidents, injuries, quality of life, function, and mortality) and adverse effects.

Acamprosate and oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) significantly decreased return to any drinking, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 12 for acamprosate and 20 for naltrexone. Oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) also decreased return to heavy drinking (NNT, 12), while acamprosate did not. Neither medication showed a decrease in heavy drinking days.

In a post hoc subgroup analysis of acamprosate for return to any drinking, the drug appeared to be more effective in studies with a higher risk for bias and less effective in studies with a lower risk for bias. The two studies with the lowest risk for bias found no significant effect.

Disulfiram had no effect on any of the outcomes analyzed.

Of the off-label medications, topiramate showed a decrease in drinking days (weighted mean difference [WMD], –6.5%), heavy drinking days (WMD, –9.0%), and drinks per drinking day (WMD, –1.0).

There were no significant differences in health outcomes for any of the medications. Adverse events were greater in treatment groups than placebo groups. Acamprosate was associated with increased risk for diarrhea (number needed to harm [NNH], 11), vomiting (NNH, 42), and anxiety (NNH, 7). Naltrexone was associated with increased risk for nausea (NNH, 9), vomiting (NNH, 24), and dizziness (NNH, 16).

WHAT’S NEW

Consider prescribing naltrexone to prevent relapse

While previous studies suggested that pharmacotherapy could help patients with AUD remain abstinent, this methodologically rigorous meta-analysis compared the efficacy of several commonly used medications and found clear evidence favoring oral naltrexone. Prescribe oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) to help patients with moderate to severe AUD avoid returning to any drinking or heavy drinking after alcohol detoxification. Acamprosate may also decrease return to drinking, although the evidence is not as strong (the studies with low bias showed no effect).

Next page: Caveats >>

CAVEATS

Medication should be used with psychosocial treatments

Pharmacotherapy for AUD should be reserved for patients who want to quit drinking and should be used in conjunction with psychosocial intervention.3 Only one of the studies analyzed by Jonas et al1 was conducted in primary care. That said, many of the psychosocial interventions—such as regular follow-up visits to encourage adherence and monitor for adverse effects, in conjunction with attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings—could be done in primary care settings.

Comorbidities may limit therapy options. Naltrexone is contraindicated in acute hepatitis and liver failure and in combination with opioids.5 Acamprosate is contraindicated in renal disease.5

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost, adherence may be factors for some patients

Perhaps the greatest hurdle in pharmacotherapy for AUD in primary care is a lack of familiarity with these medications. For clinicians who are comfortable with prescribing these medications, implementation may be hindered by a lack of available psychosocial resources for successful abstinence.

Additionally, the medications are expensive. The branded version of naltrexone (50 mg) costs approximately $118 for a 30-day supply,6 and the branded version of acamprosate costs approximately $284 for a 30-day supply.7

As is the case with any chronic medical condition, medication adherence is a challenge. Naltrexone is taken once daily, while acamprosate is taken three times a day. The risk for relapse is high until six to 12 months of sobriety is achieved and then wanes over several years.5 The NIAAA recommends treatment for a minimum of three months.5

REFERENCES

1. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311:1889-1900.

2. CDC. Fact sheets - Alcohol use and your health. www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm. Accessed April 13, 2015.

3. Johnson BA. Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-alcohol-use-disorder. Accessed April 13, 2015.

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Alcohol misuse: Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/alcohol-misuse-screening-and-behavioral-counseling-interventions-in-primary-care. Accessed April 13, 2015.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Excerpt from Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/Clinicians Guide2005/PrescribingMeds.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2015.

6. Drugs.com. Revia prices, coupons and patient assistance programs. www.drugs.com/price-guide/revia. Accessed April 13, 2015.

7. Drugs.com. Campral prices, coupons and patient assistance programs. www.drugs.com/price-guide/campral. Accessed April 13, 2015.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2015. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2015;64(4):238-240.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider prescribing oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) for patients with alcohol use disorder who wish to maintain abstinence after a brief period of detoxification.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a meta-analysis of 95 randomized controlled trials.1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Your patient, a 42-year-old man with alcohol use disorder (AUD), detoxifies from alcohol during a recent hospitalization. He doesn’t want to resume drinking but reports frequent cravings. Are there any medications you can prescribe to help prevent relapse?

Excessive alcohol consumption is responsible for one of every 10 deaths among US adults ages 20 to 64.2 About 20% to 36% of patients seen in a primary care office have AUD.3 Up to 70% of people who quit with psychosocial support alone will relapse.3

The US Preventive Services Task Force gives a grade B recommendation to screening all adults for AUD, indicating that clinicians should provide this service.4 For patients with AUD who wish to abstain but struggle with cravings and relapse, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) recommends considering medication as an adjunct to brief behavioral counseling.5

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Evidence shows naltrexone can prevent a return to drinking

In a meta-analysis, Jonas et al1 reviewed 123 studies (N = 22,803) of pharmacotherapy for AUD. After excluding 28 studies (seven were the only study of a given drug, one was a prospective cohort, and 20 had insufficient data), 95 randomized controlled trials were included in the analysis. Twenty-two were placebo-controlled for acamprosate (1,000 to 3,000 mg/d), 44 for naltrexone (50 mg/d oral, 100 mg/d oral, or injectable) and four compared the two drugs. Additional studies evaluated disulfiram as well as 23 other off-label medications, such as valproic acid and topiramate.

Two investigators independently reviewed the studies, checking for completeness and accuracy. Studies were also analyzed for bias using predefined criteria; those with high or unclear risk for bias were excluded from the main analysis but included in the sensitivity analysis. Funnel plots showed no evidence of publication bias.

Participants were primarily recruited as inpatients, and in most studies the mean age was in the 40s. Most patients were diagnosed with alcohol dependence based on criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR); this diagnosis translates to likely moderate to severe AUD in DSM-5. Prior to starting medications, participants underwent detoxification or achieved at least three days of sobriety. Most studies included psychosocial intervention in addition to medication, but the types of intervention varied. The duration of the trials ranged from 12 to 52 weeks.

Researchers analyzed five drinking outcomes—return to any drinking, return to heavy drinking (defined as ≥ 4 drinks/d for women and ≥ 5 drinks/d for men), number of drinking days, number of heavy drinking days, and drinks per drinking day. They also evaluated health outcomes (accidents, injuries, quality of life, function, and mortality) and adverse effects.

Acamprosate and oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) significantly decreased return to any drinking, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 12 for acamprosate and 20 for naltrexone. Oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) also decreased return to heavy drinking (NNT, 12), while acamprosate did not. Neither medication showed a decrease in heavy drinking days.

In a post hoc subgroup analysis of acamprosate for return to any drinking, the drug appeared to be more effective in studies with a higher risk for bias and less effective in studies with a lower risk for bias. The two studies with the lowest risk for bias found no significant effect.

Disulfiram had no effect on any of the outcomes analyzed.

Of the off-label medications, topiramate showed a decrease in drinking days (weighted mean difference [WMD], –6.5%), heavy drinking days (WMD, –9.0%), and drinks per drinking day (WMD, –1.0).

There were no significant differences in health outcomes for any of the medications. Adverse events were greater in treatment groups than placebo groups. Acamprosate was associated with increased risk for diarrhea (number needed to harm [NNH], 11), vomiting (NNH, 42), and anxiety (NNH, 7). Naltrexone was associated with increased risk for nausea (NNH, 9), vomiting (NNH, 24), and dizziness (NNH, 16).

WHAT’S NEW

Consider prescribing naltrexone to prevent relapse

While previous studies suggested that pharmacotherapy could help patients with AUD remain abstinent, this methodologically rigorous meta-analysis compared the efficacy of several commonly used medications and found clear evidence favoring oral naltrexone. Prescribe oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) to help patients with moderate to severe AUD avoid returning to any drinking or heavy drinking after alcohol detoxification. Acamprosate may also decrease return to drinking, although the evidence is not as strong (the studies with low bias showed no effect).

Next page: Caveats >>

CAVEATS

Medication should be used with psychosocial treatments

Pharmacotherapy for AUD should be reserved for patients who want to quit drinking and should be used in conjunction with psychosocial intervention.3 Only one of the studies analyzed by Jonas et al1 was conducted in primary care. That said, many of the psychosocial interventions—such as regular follow-up visits to encourage adherence and monitor for adverse effects, in conjunction with attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings—could be done in primary care settings.

Comorbidities may limit therapy options. Naltrexone is contraindicated in acute hepatitis and liver failure and in combination with opioids.5 Acamprosate is contraindicated in renal disease.5

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost, adherence may be factors for some patients

Perhaps the greatest hurdle in pharmacotherapy for AUD in primary care is a lack of familiarity with these medications. For clinicians who are comfortable with prescribing these medications, implementation may be hindered by a lack of available psychosocial resources for successful abstinence.

Additionally, the medications are expensive. The branded version of naltrexone (50 mg) costs approximately $118 for a 30-day supply,6 and the branded version of acamprosate costs approximately $284 for a 30-day supply.7

As is the case with any chronic medical condition, medication adherence is a challenge. Naltrexone is taken once daily, while acamprosate is taken three times a day. The risk for relapse is high until six to 12 months of sobriety is achieved and then wanes over several years.5 The NIAAA recommends treatment for a minimum of three months.5

REFERENCES

1. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311:1889-1900.

2. CDC. Fact sheets - Alcohol use and your health. www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm. Accessed April 13, 2015.

3. Johnson BA. Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-alcohol-use-disorder. Accessed April 13, 2015.

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Alcohol misuse: Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/alcohol-misuse-screening-and-behavioral-counseling-interventions-in-primary-care. Accessed April 13, 2015.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Excerpt from Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/Clinicians Guide2005/PrescribingMeds.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2015.

6. Drugs.com. Revia prices, coupons and patient assistance programs. www.drugs.com/price-guide/revia. Accessed April 13, 2015.

7. Drugs.com. Campral prices, coupons and patient assistance programs. www.drugs.com/price-guide/campral. Accessed April 13, 2015.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2015. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2015;64(4):238-240.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider prescribing oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) for patients with alcohol use disorder who wish to maintain abstinence after a brief period of detoxification.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a meta-analysis of 95 randomized controlled trials.1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Your patient, a 42-year-old man with alcohol use disorder (AUD), detoxifies from alcohol during a recent hospitalization. He doesn’t want to resume drinking but reports frequent cravings. Are there any medications you can prescribe to help prevent relapse?

Excessive alcohol consumption is responsible for one of every 10 deaths among US adults ages 20 to 64.2 About 20% to 36% of patients seen in a primary care office have AUD.3 Up to 70% of people who quit with psychosocial support alone will relapse.3

The US Preventive Services Task Force gives a grade B recommendation to screening all adults for AUD, indicating that clinicians should provide this service.4 For patients with AUD who wish to abstain but struggle with cravings and relapse, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) recommends considering medication as an adjunct to brief behavioral counseling.5

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Evidence shows naltrexone can prevent a return to drinking

In a meta-analysis, Jonas et al1 reviewed 123 studies (N = 22,803) of pharmacotherapy for AUD. After excluding 28 studies (seven were the only study of a given drug, one was a prospective cohort, and 20 had insufficient data), 95 randomized controlled trials were included in the analysis. Twenty-two were placebo-controlled for acamprosate (1,000 to 3,000 mg/d), 44 for naltrexone (50 mg/d oral, 100 mg/d oral, or injectable) and four compared the two drugs. Additional studies evaluated disulfiram as well as 23 other off-label medications, such as valproic acid and topiramate.

Two investigators independently reviewed the studies, checking for completeness and accuracy. Studies were also analyzed for bias using predefined criteria; those with high or unclear risk for bias were excluded from the main analysis but included in the sensitivity analysis. Funnel plots showed no evidence of publication bias.

Participants were primarily recruited as inpatients, and in most studies the mean age was in the 40s. Most patients were diagnosed with alcohol dependence based on criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR); this diagnosis translates to likely moderate to severe AUD in DSM-5. Prior to starting medications, participants underwent detoxification or achieved at least three days of sobriety. Most studies included psychosocial intervention in addition to medication, but the types of intervention varied. The duration of the trials ranged from 12 to 52 weeks.

Researchers analyzed five drinking outcomes—return to any drinking, return to heavy drinking (defined as ≥ 4 drinks/d for women and ≥ 5 drinks/d for men), number of drinking days, number of heavy drinking days, and drinks per drinking day. They also evaluated health outcomes (accidents, injuries, quality of life, function, and mortality) and adverse effects.

Acamprosate and oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) significantly decreased return to any drinking, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 12 for acamprosate and 20 for naltrexone. Oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) also decreased return to heavy drinking (NNT, 12), while acamprosate did not. Neither medication showed a decrease in heavy drinking days.

In a post hoc subgroup analysis of acamprosate for return to any drinking, the drug appeared to be more effective in studies with a higher risk for bias and less effective in studies with a lower risk for bias. The two studies with the lowest risk for bias found no significant effect.

Disulfiram had no effect on any of the outcomes analyzed.

Of the off-label medications, topiramate showed a decrease in drinking days (weighted mean difference [WMD], –6.5%), heavy drinking days (WMD, –9.0%), and drinks per drinking day (WMD, –1.0).

There were no significant differences in health outcomes for any of the medications. Adverse events were greater in treatment groups than placebo groups. Acamprosate was associated with increased risk for diarrhea (number needed to harm [NNH], 11), vomiting (NNH, 42), and anxiety (NNH, 7). Naltrexone was associated with increased risk for nausea (NNH, 9), vomiting (NNH, 24), and dizziness (NNH, 16).

WHAT’S NEW

Consider prescribing naltrexone to prevent relapse

While previous studies suggested that pharmacotherapy could help patients with AUD remain abstinent, this methodologically rigorous meta-analysis compared the efficacy of several commonly used medications and found clear evidence favoring oral naltrexone. Prescribe oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) to help patients with moderate to severe AUD avoid returning to any drinking or heavy drinking after alcohol detoxification. Acamprosate may also decrease return to drinking, although the evidence is not as strong (the studies with low bias showed no effect).

Next page: Caveats >>

CAVEATS

Medication should be used with psychosocial treatments

Pharmacotherapy for AUD should be reserved for patients who want to quit drinking and should be used in conjunction with psychosocial intervention.3 Only one of the studies analyzed by Jonas et al1 was conducted in primary care. That said, many of the psychosocial interventions—such as regular follow-up visits to encourage adherence and monitor for adverse effects, in conjunction with attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings—could be done in primary care settings.

Comorbidities may limit therapy options. Naltrexone is contraindicated in acute hepatitis and liver failure and in combination with opioids.5 Acamprosate is contraindicated in renal disease.5

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost, adherence may be factors for some patients

Perhaps the greatest hurdle in pharmacotherapy for AUD in primary care is a lack of familiarity with these medications. For clinicians who are comfortable with prescribing these medications, implementation may be hindered by a lack of available psychosocial resources for successful abstinence.

Additionally, the medications are expensive. The branded version of naltrexone (50 mg) costs approximately $118 for a 30-day supply,6 and the branded version of acamprosate costs approximately $284 for a 30-day supply.7

As is the case with any chronic medical condition, medication adherence is a challenge. Naltrexone is taken once daily, while acamprosate is taken three times a day. The risk for relapse is high until six to 12 months of sobriety is achieved and then wanes over several years.5 The NIAAA recommends treatment for a minimum of three months.5

REFERENCES

1. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311:1889-1900.

2. CDC. Fact sheets - Alcohol use and your health. www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm. Accessed April 13, 2015.

3. Johnson BA. Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-alcohol-use-disorder. Accessed April 13, 2015.

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Alcohol misuse: Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/alcohol-misuse-screening-and-behavioral-counseling-interventions-in-primary-care. Accessed April 13, 2015.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Excerpt from Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/Clinicians Guide2005/PrescribingMeds.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2015.

6. Drugs.com. Revia prices, coupons and patient assistance programs. www.drugs.com/price-guide/revia. Accessed April 13, 2015.

7. Drugs.com. Campral prices, coupons and patient assistance programs. www.drugs.com/price-guide/campral. Accessed April 13, 2015.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2015. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2015;64(4):238-240.

Is nonoperative therapy as effective as surgery for meniscal injuries?

Yes. There is no significant difference in symptom or functional improvement between adult patients with symptomatic meniscal injury who are treated with operative vs nonoperative therapy (strength of recommendation: A, consistent randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both approaches resulted in function and pain improvement

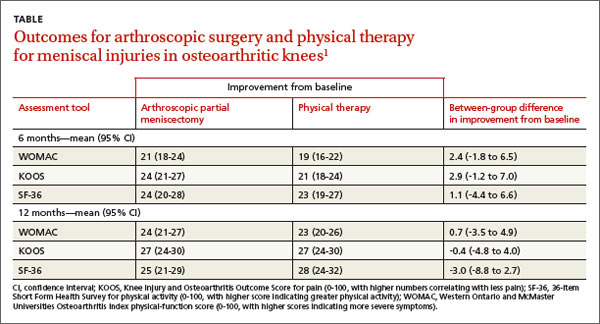

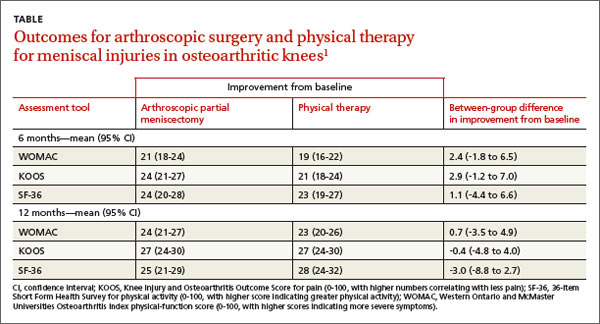

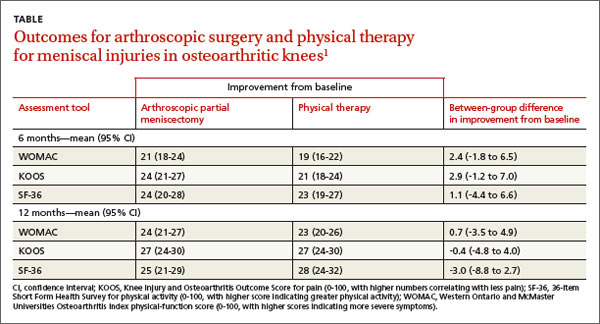

A 2013 multicenter RCT evaluated 351 adults, 45 years and older, with a meniscal tear and mild to moderate osteoarthritis confirmed by imaging, for functional improvement by physical therapy alone compared with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy and physical therapy.1

At the beginning of the study and 6 and 12 months after treatment, researchers assessed symptoms using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index physical-function score (0-100, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms), the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) for pain (0-100, with higher numbers correlating with less pain), and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) for physical activity (0-100, with higher scores indicating greater physical activity).

Modified intention to treat analysis showed no significant difference in function and pain improvement at 6 and 12 months between patients with meniscal injury who underwent arthroscopic repair and physical therapy and patients who underwent physical therapy alone (TABLE1). A limitation of the study was the crossover of 30% of patients from the nonoperative group to the operative group.

No differences found in Tx outcomes for nontraumatic tears

A 2007 prospective RCT evaluated 90 adults ages 45 to 64 with nontraumatic meniscal tears confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging for improvement in knee pain and function with arthroscopic treatment and supervised exercise (AE) or supervised exercise (E) alone.2 Knee pain and function were assessed before intervention, after 8 weeks, and after 6 months of treatment using 3 surveys: the KOOS, the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale (LKSS; 0-100, with higher scores correlating with good knee function), and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for knee pain (0-10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating maximum pain).

The KOOS revealed that at 8 weeks and 6 months both groups had significant improvement from the initial evaluation in all subscale scores. In the AE group, the 8-week pain score increased from a baseline of 56 to 89 (P<.001) and remained at 89 at 6 months (P<.001). For the E group, the 8-week pain score improved from a baseline of 62 to 86 (P<.001) and continued at 86 after 6 months (P<.001).

The LKSS score for both groups showed significant improvement from baseline at 8 weeks: 34% of the AE group and 42% of the E group scored higher than 91 (P<.001).

VAS scores showed a significant decrease in pain at 8 weeks for both the AE and E groups: beginning median value for both groups was 5.5 and decreased to 1.0 at 8 weeks and 6 months (P<.001).

The authors concluded that both groups improved significantly from initial evaluation regardless of treatment method and that no statistically significant difference existed between treatment results.

1. Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1675-1684.

2. Herrlin S, Hallander M, Wange P, et al. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:393-401.

Yes. There is no significant difference in symptom or functional improvement between adult patients with symptomatic meniscal injury who are treated with operative vs nonoperative therapy (strength of recommendation: A, consistent randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both approaches resulted in function and pain improvement

A 2013 multicenter RCT evaluated 351 adults, 45 years and older, with a meniscal tear and mild to moderate osteoarthritis confirmed by imaging, for functional improvement by physical therapy alone compared with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy and physical therapy.1

At the beginning of the study and 6 and 12 months after treatment, researchers assessed symptoms using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index physical-function score (0-100, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms), the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) for pain (0-100, with higher numbers correlating with less pain), and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) for physical activity (0-100, with higher scores indicating greater physical activity).

Modified intention to treat analysis showed no significant difference in function and pain improvement at 6 and 12 months between patients with meniscal injury who underwent arthroscopic repair and physical therapy and patients who underwent physical therapy alone (TABLE1). A limitation of the study was the crossover of 30% of patients from the nonoperative group to the operative group.

No differences found in Tx outcomes for nontraumatic tears

A 2007 prospective RCT evaluated 90 adults ages 45 to 64 with nontraumatic meniscal tears confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging for improvement in knee pain and function with arthroscopic treatment and supervised exercise (AE) or supervised exercise (E) alone.2 Knee pain and function were assessed before intervention, after 8 weeks, and after 6 months of treatment using 3 surveys: the KOOS, the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale (LKSS; 0-100, with higher scores correlating with good knee function), and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for knee pain (0-10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating maximum pain).

The KOOS revealed that at 8 weeks and 6 months both groups had significant improvement from the initial evaluation in all subscale scores. In the AE group, the 8-week pain score increased from a baseline of 56 to 89 (P<.001) and remained at 89 at 6 months (P<.001). For the E group, the 8-week pain score improved from a baseline of 62 to 86 (P<.001) and continued at 86 after 6 months (P<.001).

The LKSS score for both groups showed significant improvement from baseline at 8 weeks: 34% of the AE group and 42% of the E group scored higher than 91 (P<.001).

VAS scores showed a significant decrease in pain at 8 weeks for both the AE and E groups: beginning median value for both groups was 5.5 and decreased to 1.0 at 8 weeks and 6 months (P<.001).

The authors concluded that both groups improved significantly from initial evaluation regardless of treatment method and that no statistically significant difference existed between treatment results.

Yes. There is no significant difference in symptom or functional improvement between adult patients with symptomatic meniscal injury who are treated with operative vs nonoperative therapy (strength of recommendation: A, consistent randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both approaches resulted in function and pain improvement

A 2013 multicenter RCT evaluated 351 adults, 45 years and older, with a meniscal tear and mild to moderate osteoarthritis confirmed by imaging, for functional improvement by physical therapy alone compared with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy and physical therapy.1

At the beginning of the study and 6 and 12 months after treatment, researchers assessed symptoms using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index physical-function score (0-100, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms), the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) for pain (0-100, with higher numbers correlating with less pain), and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) for physical activity (0-100, with higher scores indicating greater physical activity).

Modified intention to treat analysis showed no significant difference in function and pain improvement at 6 and 12 months between patients with meniscal injury who underwent arthroscopic repair and physical therapy and patients who underwent physical therapy alone (TABLE1). A limitation of the study was the crossover of 30% of patients from the nonoperative group to the operative group.

No differences found in Tx outcomes for nontraumatic tears

A 2007 prospective RCT evaluated 90 adults ages 45 to 64 with nontraumatic meniscal tears confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging for improvement in knee pain and function with arthroscopic treatment and supervised exercise (AE) or supervised exercise (E) alone.2 Knee pain and function were assessed before intervention, after 8 weeks, and after 6 months of treatment using 3 surveys: the KOOS, the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale (LKSS; 0-100, with higher scores correlating with good knee function), and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for knee pain (0-10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating maximum pain).

The KOOS revealed that at 8 weeks and 6 months both groups had significant improvement from the initial evaluation in all subscale scores. In the AE group, the 8-week pain score increased from a baseline of 56 to 89 (P<.001) and remained at 89 at 6 months (P<.001). For the E group, the 8-week pain score improved from a baseline of 62 to 86 (P<.001) and continued at 86 after 6 months (P<.001).

The LKSS score for both groups showed significant improvement from baseline at 8 weeks: 34% of the AE group and 42% of the E group scored higher than 91 (P<.001).

VAS scores showed a significant decrease in pain at 8 weeks for both the AE and E groups: beginning median value for both groups was 5.5 and decreased to 1.0 at 8 weeks and 6 months (P<.001).

The authors concluded that both groups improved significantly from initial evaluation regardless of treatment method and that no statistically significant difference existed between treatment results.

1. Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1675-1684.

2. Herrlin S, Hallander M, Wange P, et al. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:393-401.

1. Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1675-1684.

2. Herrlin S, Hallander M, Wange P, et al. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:393-401.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Child With “Distressing” Problem

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “a”). This benign hamartomatous lesion is derived from local tissue and grows at the same rate.

It differs considerably from the other items in the differential, including aplasia cutis congenita (choice “b”). In this condition, a focal area of epidermis simply fails to develop, leaving a permanent hairless scar that contrasts sharply with the raised, mammillated plaque of nevus sebaceous.

Epidermal nevus (choice “c”) is usually a collection of tan to brown superficial nevoid papules that can be linear, agminated, or plaque-like. These lesions lack the color and mammillated surface of those seen in nevus sebaceous.

Neonatal lupus (choice “d”) can present at birth with hairless, cicatricial inflamed lesions. However, these tend to resolve quickly, often leaving focal scarring alopecia but no plaque formation.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS), first described by Jadassohn in 1895, has long been recognized as an unusual but by no means rare congenital lesion. Occurring equally in both sexes and comprising sebaceous glands in a nevoid morphologic context, NS is considered a variant of sebaceous nevi and verrucous epidermal nevi in some circles. All three are derived from overgrowth of local, normal tissues that typically grow at the same rate as surrounding structures.

The vast majority of NS lesions are found in the scalp, although they can also develop on the ear or neck and, rarely, elsewhere on the body. This patient’s plaque—with its uniform surface; tiny, smooth, shiny papules; and (perhaps most important) total lack of hair—is typical. Other classic features are congenital onset and permanent nature, which distinguish them from the rest of the differential.

Focal malignant transformation of NS lesions has been reported—in fact, this author has seen two such cases in 30 years. Both were small basal cell carcinomas, although cases of melanoma and other malignancies have been reported.

Such changes are rare enough that most experts consider prophylactic removal to be unwarranted. Watching the lesions for change over the years is certainly reasonable, as is protecting them from sun exposure.

Surgical removal—usually performed by a plastic surgeon—is occasionally necessary for cosmetic reasons. This is particularly so when NS covers a portion of the face, or when the cosmetic implications of having a hairless plaque in the scalp are sufficiently distressing.

This patient and her parents were educated about the nature of the diagnosis and apprised of their options.

Editor's note: For a similar presentation with a very different diagnosis, see the March 2015 DermaDiagnosis case (http://bit.ly/1ye69Ym).

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “a”). This benign hamartomatous lesion is derived from local tissue and grows at the same rate.

It differs considerably from the other items in the differential, including aplasia cutis congenita (choice “b”). In this condition, a focal area of epidermis simply fails to develop, leaving a permanent hairless scar that contrasts sharply with the raised, mammillated plaque of nevus sebaceous.

Epidermal nevus (choice “c”) is usually a collection of tan to brown superficial nevoid papules that can be linear, agminated, or plaque-like. These lesions lack the color and mammillated surface of those seen in nevus sebaceous.

Neonatal lupus (choice “d”) can present at birth with hairless, cicatricial inflamed lesions. However, these tend to resolve quickly, often leaving focal scarring alopecia but no plaque formation.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS), first described by Jadassohn in 1895, has long been recognized as an unusual but by no means rare congenital lesion. Occurring equally in both sexes and comprising sebaceous glands in a nevoid morphologic context, NS is considered a variant of sebaceous nevi and verrucous epidermal nevi in some circles. All three are derived from overgrowth of local, normal tissues that typically grow at the same rate as surrounding structures.

The vast majority of NS lesions are found in the scalp, although they can also develop on the ear or neck and, rarely, elsewhere on the body. This patient’s plaque—with its uniform surface; tiny, smooth, shiny papules; and (perhaps most important) total lack of hair—is typical. Other classic features are congenital onset and permanent nature, which distinguish them from the rest of the differential.

Focal malignant transformation of NS lesions has been reported—in fact, this author has seen two such cases in 30 years. Both were small basal cell carcinomas, although cases of melanoma and other malignancies have been reported.

Such changes are rare enough that most experts consider prophylactic removal to be unwarranted. Watching the lesions for change over the years is certainly reasonable, as is protecting them from sun exposure.

Surgical removal—usually performed by a plastic surgeon—is occasionally necessary for cosmetic reasons. This is particularly so when NS covers a portion of the face, or when the cosmetic implications of having a hairless plaque in the scalp are sufficiently distressing.

This patient and her parents were educated about the nature of the diagnosis and apprised of their options.

Editor's note: For a similar presentation with a very different diagnosis, see the March 2015 DermaDiagnosis case (http://bit.ly/1ye69Ym).

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “a”). This benign hamartomatous lesion is derived from local tissue and grows at the same rate.

It differs considerably from the other items in the differential, including aplasia cutis congenita (choice “b”). In this condition, a focal area of epidermis simply fails to develop, leaving a permanent hairless scar that contrasts sharply with the raised, mammillated plaque of nevus sebaceous.

Epidermal nevus (choice “c”) is usually a collection of tan to brown superficial nevoid papules that can be linear, agminated, or plaque-like. These lesions lack the color and mammillated surface of those seen in nevus sebaceous.

Neonatal lupus (choice “d”) can present at birth with hairless, cicatricial inflamed lesions. However, these tend to resolve quickly, often leaving focal scarring alopecia but no plaque formation.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS), first described by Jadassohn in 1895, has long been recognized as an unusual but by no means rare congenital lesion. Occurring equally in both sexes and comprising sebaceous glands in a nevoid morphologic context, NS is considered a variant of sebaceous nevi and verrucous epidermal nevi in some circles. All three are derived from overgrowth of local, normal tissues that typically grow at the same rate as surrounding structures.

The vast majority of NS lesions are found in the scalp, although they can also develop on the ear or neck and, rarely, elsewhere on the body. This patient’s plaque—with its uniform surface; tiny, smooth, shiny papules; and (perhaps most important) total lack of hair—is typical. Other classic features are congenital onset and permanent nature, which distinguish them from the rest of the differential.

Focal malignant transformation of NS lesions has been reported—in fact, this author has seen two such cases in 30 years. Both were small basal cell carcinomas, although cases of melanoma and other malignancies have been reported.

Such changes are rare enough that most experts consider prophylactic removal to be unwarranted. Watching the lesions for change over the years is certainly reasonable, as is protecting them from sun exposure.

Surgical removal—usually performed by a plastic surgeon—is occasionally necessary for cosmetic reasons. This is particularly so when NS covers a portion of the face, or when the cosmetic implications of having a hairless plaque in the scalp are sufficiently distressing.

This patient and her parents were educated about the nature of the diagnosis and apprised of their options.

Editor's note: For a similar presentation with a very different diagnosis, see the March 2015 DermaDiagnosis case (http://bit.ly/1ye69Ym).

A “bald spot” is the chief complaint of a 12-year-old girl brought for evaluation by her mother. The lesion in her left parietal scalp has been there since birth, slowly growing but producing no symptoms. Although the child’s primary care provider has reassured the family that the “birthmark” is benign, they remain concerned. Furthermore, the patient has become increasingly distressed by the hairlessness. The child is otherwise healthy. There is no history of excessive sun exposure. The lesion is a roughly oval, uniformly pink, hairless 3.6-cm plaque with a faintly mammillated surface and well-defined margins. It is only visible when the surrounding hair is parted sufficiently to reveal it. Examination of the rest of the patient’s skin is unremarkable.

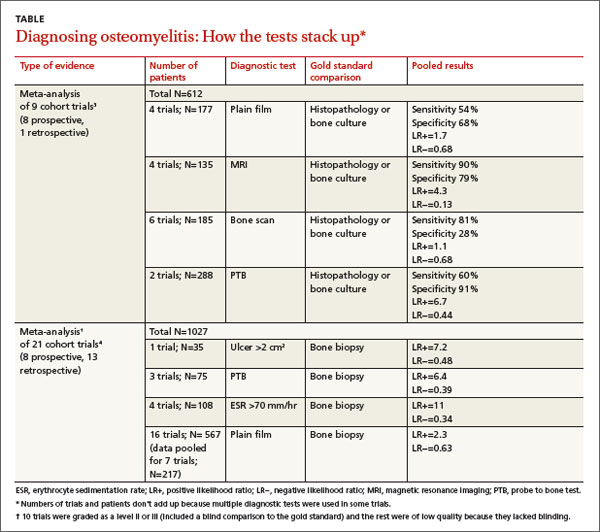

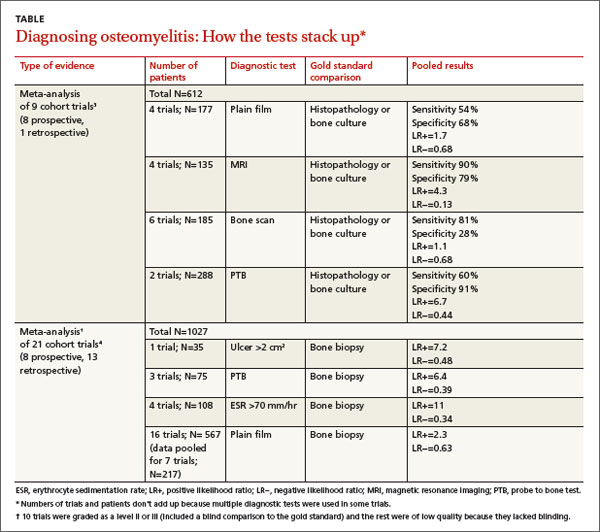

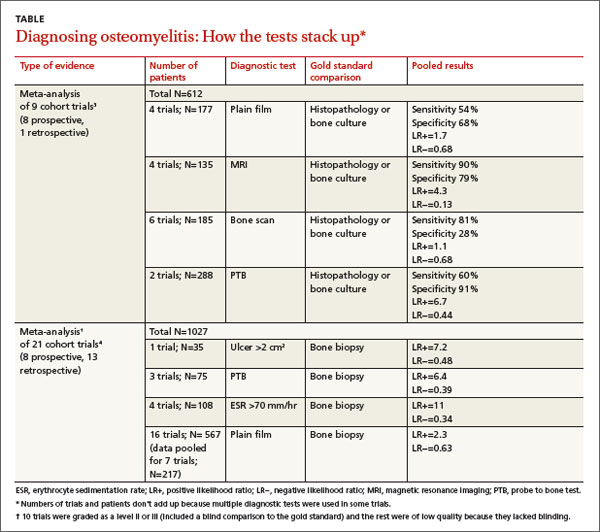

What’s the best test for underlying osteomyelitis in patients with diabetic foot ulcers?

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a higher sensitivity and specificity (90% and 79%) than plain radiography (54% and 68%) for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis. MRI performs somewhat better than any of several common tests—probe to bone (PTB), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >70 mm/hr, C-reactive protein (CRP) >14 mg/L, procalcitonin >0.3 ng/mL, and ulcer size >2 cm2—although PTB has the highest specificity of any test and is commonly used together with MRI. No studies have directly compared MRI with a combination of these tests, which may assist in diagnosis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of cohort trials and individual cohort and case control trial).

Experts recommend obtaining plain films when considering diabetic foot ulcers to evaluate for bony abnormalities, soft tissue gas, and foreign body; MRI should be considered in most situations when infection is suspected (SOR: B, evidence-based guidelines).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

One-fifth of patients with diabetes who have foot ulcerations will develop osteomyelitis.1,2 Most cases of diabetic foot osteomyelitis result from the spread of a foot infection to underlying bone.2

MRI has highest sensitivity, probe to bone test is most specific

A meta-analysis3 of 9 cohort trials (8 prospective, 1 retrospective) of 612 patients with diabetes and a foot ulcer examined the accuracy of diagnostic methods for osteomyelitis (TABLE3,4). MRI had the highest sensitivity (90%), followed by bone scan (81%). Bone scan was the least specific (28%), however. Plain film radiography had the lowest sensitivity (54%). A PTB test was highly specific (91%) but had moderate sensitivity (60%). (PTB involves inserting a sterile, blunt stainless steel probe into an ulcerated lesion. If the probe comes to a hard stop, considered to be bone, the test is positive.)

A meta-analysis of 21 prospective and retrospective trials with 1027 diabetic patients with foot ulcers or suspected osteomyelitis found that ulcer size >2 cm2, PTB, and ESR >70 mm/hr were helpful in making the diagnosis.4

Combining ESR with ulcer size increases specificity

A prospective trial of 46 diabetic patients hospitalized with a foot infection examined the accuracy of a combination of clinical and laboratory diagnostic features in patients with diabetic foot osteomyelitis that had been diagnosed by MRI or histopathology.5 (Twenty-four patients had osteomyelitis, and 22 didn’t.)

ESR >70 mm/hr had a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 77% (positive likelihood ratio [LR+]=3.6; negative likelihood ratio [LR−]=0.22). Ulcer size >2 cm2 had a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 77% (LR+=3.8; LR−=0.16). Combined, an ESR >70 mm/hr and ulcer size >2cm2 had a slightly better specificity than either finding alone, 82%, but a lower sensitivity of 79% (LR+=4.4; LR−= 0.26).

Serum markers accurately distinguish osteomyelitis from infection

An individual prospective cohort trial of 61 adult patients with diabetes and a foot infection, published after the meta-analysis4 described previously, examined the accuracy of serum markers (ESR, CRP, procalcitonin) for diagnosing osteomyelitis.6 A positive PTB test and imaging study (plain film, MRI, or nuclear scintigraphy) were used as the diagnostic gold standard.

Thirty-four patients had a soft tissue infection and 27 had osteomyelitis. All markers were higher in patients with osteomyelitis than in patients with a soft tissue infection (ESR=76 mm/hr vs 66 mm/hr; P<.001; CRP=25 mg/L vs 8.7 mg/L; P<.001; procalcitonin=2.4 ng/mL vs 0.71 ng/mL; P<.001). The sensitivity and specificity for each marker at its optimum points were: ESR >67 mm/hr (sensitivity 84%; specificity 75%; LR+=3.4; LR−=0.21); CRP >14 mg/L (sensitivity 85%; specificity 83%; LR+=5; LR−=0.18); and procalcitonin >0.3 ng/mL (sensitivity 81%; specificity 71%; LR+=2.8; LR−=0.27).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends performing the PTB test on any diabetic foot infection with an open wound (level of evidence: strong moderate).7 It also recommends performing plain radiography on all patients presenting with a new infection to evaluate for bony abnormalities, soft tissue gas, and foreign bodies (level of evidence: strong moderate).

The IDSA, the American College of Radiology diagnostic imaging expert panel, and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommend using MRI in most clinical scenarios when osteomyelitis is suspected (level of evidence: strong moderate).8,9

1. Gemechu FW, Seemant F, Curley CA. Diabetic foot infections. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:177-184.

2. Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Peters EJ, et al. Probe-to-bone test for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis: reliable or relic? Diabetes Care. 2007;30:270-274.

3. Dinh MT, Abad CL, Safdar N. Diagnostic accuracy of the physical examination and imaging tests for osteomyelitis underlying diabetic foot ulcers: meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:519-527.

4. Butalia S, Palda VA, Sargeant RJ, et al. Does this patient with diabetes have osteomyelitis of the lower extremity? JAMA. 2008;299:806-813.

5. Ertugrul BM, Savk O, Ozturk B, et al. The diagnosis of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: examination findings and laboratory values. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:CR307-CR312.

6. Michail M, Jude E, Liaskos C, et al. The performance of serum inflammatory markers for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with osteomyelitis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2013;12:94-99.

7. Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e132-e173.

8. Schweitzer ME, Daffner RH, Weissman BN, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria on suspected osteomyelitis in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5:881-886.

9. Tan T, Shaw EJ, Siddiqui F, et al; Guideline Development Group. Inpatient management of diabetic foot problems: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;342:d1280.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a higher sensitivity and specificity (90% and 79%) than plain radiography (54% and 68%) for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis. MRI performs somewhat better than any of several common tests—probe to bone (PTB), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >70 mm/hr, C-reactive protein (CRP) >14 mg/L, procalcitonin >0.3 ng/mL, and ulcer size >2 cm2—although PTB has the highest specificity of any test and is commonly used together with MRI. No studies have directly compared MRI with a combination of these tests, which may assist in diagnosis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of cohort trials and individual cohort and case control trial).

Experts recommend obtaining plain films when considering diabetic foot ulcers to evaluate for bony abnormalities, soft tissue gas, and foreign body; MRI should be considered in most situations when infection is suspected (SOR: B, evidence-based guidelines).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

One-fifth of patients with diabetes who have foot ulcerations will develop osteomyelitis.1,2 Most cases of diabetic foot osteomyelitis result from the spread of a foot infection to underlying bone.2

MRI has highest sensitivity, probe to bone test is most specific

A meta-analysis3 of 9 cohort trials (8 prospective, 1 retrospective) of 612 patients with diabetes and a foot ulcer examined the accuracy of diagnostic methods for osteomyelitis (TABLE3,4). MRI had the highest sensitivity (90%), followed by bone scan (81%). Bone scan was the least specific (28%), however. Plain film radiography had the lowest sensitivity (54%). A PTB test was highly specific (91%) but had moderate sensitivity (60%). (PTB involves inserting a sterile, blunt stainless steel probe into an ulcerated lesion. If the probe comes to a hard stop, considered to be bone, the test is positive.)

A meta-analysis of 21 prospective and retrospective trials with 1027 diabetic patients with foot ulcers or suspected osteomyelitis found that ulcer size >2 cm2, PTB, and ESR >70 mm/hr were helpful in making the diagnosis.4

Combining ESR with ulcer size increases specificity

A prospective trial of 46 diabetic patients hospitalized with a foot infection examined the accuracy of a combination of clinical and laboratory diagnostic features in patients with diabetic foot osteomyelitis that had been diagnosed by MRI or histopathology.5 (Twenty-four patients had osteomyelitis, and 22 didn’t.)

ESR >70 mm/hr had a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 77% (positive likelihood ratio [LR+]=3.6; negative likelihood ratio [LR−]=0.22). Ulcer size >2 cm2 had a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 77% (LR+=3.8; LR−=0.16). Combined, an ESR >70 mm/hr and ulcer size >2cm2 had a slightly better specificity than either finding alone, 82%, but a lower sensitivity of 79% (LR+=4.4; LR−= 0.26).

Serum markers accurately distinguish osteomyelitis from infection

An individual prospective cohort trial of 61 adult patients with diabetes and a foot infection, published after the meta-analysis4 described previously, examined the accuracy of serum markers (ESR, CRP, procalcitonin) for diagnosing osteomyelitis.6 A positive PTB test and imaging study (plain film, MRI, or nuclear scintigraphy) were used as the diagnostic gold standard.

Thirty-four patients had a soft tissue infection and 27 had osteomyelitis. All markers were higher in patients with osteomyelitis than in patients with a soft tissue infection (ESR=76 mm/hr vs 66 mm/hr; P<.001; CRP=25 mg/L vs 8.7 mg/L; P<.001; procalcitonin=2.4 ng/mL vs 0.71 ng/mL; P<.001). The sensitivity and specificity for each marker at its optimum points were: ESR >67 mm/hr (sensitivity 84%; specificity 75%; LR+=3.4; LR−=0.21); CRP >14 mg/L (sensitivity 85%; specificity 83%; LR+=5; LR−=0.18); and procalcitonin >0.3 ng/mL (sensitivity 81%; specificity 71%; LR+=2.8; LR−=0.27).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends performing the PTB test on any diabetic foot infection with an open wound (level of evidence: strong moderate).7 It also recommends performing plain radiography on all patients presenting with a new infection to evaluate for bony abnormalities, soft tissue gas, and foreign bodies (level of evidence: strong moderate).

The IDSA, the American College of Radiology diagnostic imaging expert panel, and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommend using MRI in most clinical scenarios when osteomyelitis is suspected (level of evidence: strong moderate).8,9