User login

Model helps explain chaotic angiogenesis

Image by Louis Heiser

and Robert Ackland

Scientists say they have developed a model that provides new insight into chaotic angiogenesis, a hallmark of cancer.

The model shows how proteins involved in angiogenesis communicate with each other and how tumors take charge of the protein signaling chain that controls blood vessel growth.

The work, published in PNAS, suggests that Jagged ligands play a major role in the chaotic vessel growth observed around tumors.

In normal growth, an endothelial cell sprouts from an existing blood vessel as a tip. Others that follow the tip cell become the stalk cells that ultimately form vessel walls. The Notch signaling pathway directs the endothelial cell’s decision to become a tip or stalk.

Notch receptors bind with Delta ligand or Jagged ligand molecules produced by cells. How they interact determines the cell’s fate.

When Notch and Delta bind, they prompt a few cells to be tips and adjacent ones to be stalks. The Notch-Delta pathway has been studied extensively and is the target of many angiogenesis inhibitors now in use, according to the scientists.

“We wondered exactly what Notch-Jagged signaling does that is not done in Notch-Delta signaling,” said study author Marcelo Boareto, PhD, of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

“We find that when the cells communicate mostly via Jagged, we see a new kind of cell that is not exactly tip and not exactly stalk, but somewhere in between. This compromised cell is the major difference between normal and tumor angiogenesis and suggests that if Notch-Jagged signaling can be somehow suppressed without affecting Notch-Delta, we can probably disrupt tumor angiogenesis.”

The scientists found the tip/stalk hybrid cells do form new blood vessels, but these vessels rarely mature.

“High levels of Jagged in the environment can trigger the formation of blood vessels that are useful to the tumor: fast-developing, leaky, and spread chaotically all over the tumor mass,” Dr Boareto said.

“Tumors don’t have to wait for the vessels to develop,” added study author José Onuchic, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas. “They take advantage of the leakiness of the structure.”

The scientists’ model also takes into account the effect of vascular endothelial growth factor, which triggers angiogenesis and is overexpressed by tumor cells.

“It is very interesting how the tumor hijacks this important mechanism, which is needed for the development of a functional vessel, and amplifies it to generate pathological angiogenesis that leads to uncontrolled growth,” Dr Onuchic said. ![]()

Image by Louis Heiser

and Robert Ackland

Scientists say they have developed a model that provides new insight into chaotic angiogenesis, a hallmark of cancer.

The model shows how proteins involved in angiogenesis communicate with each other and how tumors take charge of the protein signaling chain that controls blood vessel growth.

The work, published in PNAS, suggests that Jagged ligands play a major role in the chaotic vessel growth observed around tumors.

In normal growth, an endothelial cell sprouts from an existing blood vessel as a tip. Others that follow the tip cell become the stalk cells that ultimately form vessel walls. The Notch signaling pathway directs the endothelial cell’s decision to become a tip or stalk.

Notch receptors bind with Delta ligand or Jagged ligand molecules produced by cells. How they interact determines the cell’s fate.

When Notch and Delta bind, they prompt a few cells to be tips and adjacent ones to be stalks. The Notch-Delta pathway has been studied extensively and is the target of many angiogenesis inhibitors now in use, according to the scientists.

“We wondered exactly what Notch-Jagged signaling does that is not done in Notch-Delta signaling,” said study author Marcelo Boareto, PhD, of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

“We find that when the cells communicate mostly via Jagged, we see a new kind of cell that is not exactly tip and not exactly stalk, but somewhere in between. This compromised cell is the major difference between normal and tumor angiogenesis and suggests that if Notch-Jagged signaling can be somehow suppressed without affecting Notch-Delta, we can probably disrupt tumor angiogenesis.”

The scientists found the tip/stalk hybrid cells do form new blood vessels, but these vessels rarely mature.

“High levels of Jagged in the environment can trigger the formation of blood vessels that are useful to the tumor: fast-developing, leaky, and spread chaotically all over the tumor mass,” Dr Boareto said.

“Tumors don’t have to wait for the vessels to develop,” added study author José Onuchic, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas. “They take advantage of the leakiness of the structure.”

The scientists’ model also takes into account the effect of vascular endothelial growth factor, which triggers angiogenesis and is overexpressed by tumor cells.

“It is very interesting how the tumor hijacks this important mechanism, which is needed for the development of a functional vessel, and amplifies it to generate pathological angiogenesis that leads to uncontrolled growth,” Dr Onuchic said. ![]()

Image by Louis Heiser

and Robert Ackland

Scientists say they have developed a model that provides new insight into chaotic angiogenesis, a hallmark of cancer.

The model shows how proteins involved in angiogenesis communicate with each other and how tumors take charge of the protein signaling chain that controls blood vessel growth.

The work, published in PNAS, suggests that Jagged ligands play a major role in the chaotic vessel growth observed around tumors.

In normal growth, an endothelial cell sprouts from an existing blood vessel as a tip. Others that follow the tip cell become the stalk cells that ultimately form vessel walls. The Notch signaling pathway directs the endothelial cell’s decision to become a tip or stalk.

Notch receptors bind with Delta ligand or Jagged ligand molecules produced by cells. How they interact determines the cell’s fate.

When Notch and Delta bind, they prompt a few cells to be tips and adjacent ones to be stalks. The Notch-Delta pathway has been studied extensively and is the target of many angiogenesis inhibitors now in use, according to the scientists.

“We wondered exactly what Notch-Jagged signaling does that is not done in Notch-Delta signaling,” said study author Marcelo Boareto, PhD, of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

“We find that when the cells communicate mostly via Jagged, we see a new kind of cell that is not exactly tip and not exactly stalk, but somewhere in between. This compromised cell is the major difference between normal and tumor angiogenesis and suggests that if Notch-Jagged signaling can be somehow suppressed without affecting Notch-Delta, we can probably disrupt tumor angiogenesis.”

The scientists found the tip/stalk hybrid cells do form new blood vessels, but these vessels rarely mature.

“High levels of Jagged in the environment can trigger the formation of blood vessels that are useful to the tumor: fast-developing, leaky, and spread chaotically all over the tumor mass,” Dr Boareto said.

“Tumors don’t have to wait for the vessels to develop,” added study author José Onuchic, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas. “They take advantage of the leakiness of the structure.”

The scientists’ model also takes into account the effect of vascular endothelial growth factor, which triggers angiogenesis and is overexpressed by tumor cells.

“It is very interesting how the tumor hijacks this important mechanism, which is needed for the development of a functional vessel, and amplifies it to generate pathological angiogenesis that leads to uncontrolled growth,” Dr Onuchic said. ![]()

Sepsis readmissions common and costly, group says

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Hospital readmissions for sepsis are under-recognized, and additional measures are needed to prevent these readmissions, researchers say.

The group conducted a study of California hospitals that showed sepsis accounts for roughly the same percentage of readmissions as heart attacks and congestive heart failure.

However, sepsis readmissions cost the healthcare system more than heart attack and congestive heart failure readmissions combined.

The research was published in Critical Care Medicine.

“Our study shows how common sepsis readmissions are and [elucidates] some of the factors that are associated with higher risk of readmission after these severe infections,” said study author Dong Chang, MD, of Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, California.

“In addition, we show that sepsis readmissions have a significant impact on healthcare expenditures relative to other high-risk conditions that are receiving active attention and interventions. Based on these results, we believe that sepsis readmissions are under-recognized and should be among the conditions that are targeted for intervention by policymakers.”

The researchers analyzed data on sepsis admissions for adults 18 years of age and older at all California hospitals from 2009 through 2011. The team also analyzed data for congestive heart failure and heart attack admissions during the same period.

There were 240,198 admissions for sepsis, 193,153 for congestive heart failure, and 105,684 for heart attacks. The all-cause, 30-day readmission rate was 20.4% for sepsis, 23.6% for congestive heart failure, and 17.7% for heart attacks.

Patients with sepsis were readmitted because of respiratory failure; pneumonia; urinary tract infections; renal infections; renal failure; intestinal infections; complications with devices, implants, or grafts; and other causes.

Sepsis readmission rates were higher among young adults than older adults, among men than women, among black and Native American patients than other racial groups, and among lower-income patients than those with higher incomes. In addition, patients with other concurrent health problems were more likely to be readmitted than those with sepsis alone.

The estimated annual cost of sepsis-related readmissions in California during the study period was $500 million, compared with $229 million for congestive heart failure and $142 million for heart attacks.

“These findings suggest that efforts to reduce hospital readmissions need to include sepsis prominently, at least on par with heart failure and myocardial infarction,” said study author Martin Shapiro, MD, PhD, of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

Next, the researchers plan to examine why patients are readmitted after sepsis and the percentage of those readmissions that are due to processes that can be improved upon, such as discharge practices, follow-up care, and teaching patients how to take their medications. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Hospital readmissions for sepsis are under-recognized, and additional measures are needed to prevent these readmissions, researchers say.

The group conducted a study of California hospitals that showed sepsis accounts for roughly the same percentage of readmissions as heart attacks and congestive heart failure.

However, sepsis readmissions cost the healthcare system more than heart attack and congestive heart failure readmissions combined.

The research was published in Critical Care Medicine.

“Our study shows how common sepsis readmissions are and [elucidates] some of the factors that are associated with higher risk of readmission after these severe infections,” said study author Dong Chang, MD, of Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, California.

“In addition, we show that sepsis readmissions have a significant impact on healthcare expenditures relative to other high-risk conditions that are receiving active attention and interventions. Based on these results, we believe that sepsis readmissions are under-recognized and should be among the conditions that are targeted for intervention by policymakers.”

The researchers analyzed data on sepsis admissions for adults 18 years of age and older at all California hospitals from 2009 through 2011. The team also analyzed data for congestive heart failure and heart attack admissions during the same period.

There were 240,198 admissions for sepsis, 193,153 for congestive heart failure, and 105,684 for heart attacks. The all-cause, 30-day readmission rate was 20.4% for sepsis, 23.6% for congestive heart failure, and 17.7% for heart attacks.

Patients with sepsis were readmitted because of respiratory failure; pneumonia; urinary tract infections; renal infections; renal failure; intestinal infections; complications with devices, implants, or grafts; and other causes.

Sepsis readmission rates were higher among young adults than older adults, among men than women, among black and Native American patients than other racial groups, and among lower-income patients than those with higher incomes. In addition, patients with other concurrent health problems were more likely to be readmitted than those with sepsis alone.

The estimated annual cost of sepsis-related readmissions in California during the study period was $500 million, compared with $229 million for congestive heart failure and $142 million for heart attacks.

“These findings suggest that efforts to reduce hospital readmissions need to include sepsis prominently, at least on par with heart failure and myocardial infarction,” said study author Martin Shapiro, MD, PhD, of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

Next, the researchers plan to examine why patients are readmitted after sepsis and the percentage of those readmissions that are due to processes that can be improved upon, such as discharge practices, follow-up care, and teaching patients how to take their medications. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Hospital readmissions for sepsis are under-recognized, and additional measures are needed to prevent these readmissions, researchers say.

The group conducted a study of California hospitals that showed sepsis accounts for roughly the same percentage of readmissions as heart attacks and congestive heart failure.

However, sepsis readmissions cost the healthcare system more than heart attack and congestive heart failure readmissions combined.

The research was published in Critical Care Medicine.

“Our study shows how common sepsis readmissions are and [elucidates] some of the factors that are associated with higher risk of readmission after these severe infections,” said study author Dong Chang, MD, of Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, California.

“In addition, we show that sepsis readmissions have a significant impact on healthcare expenditures relative to other high-risk conditions that are receiving active attention and interventions. Based on these results, we believe that sepsis readmissions are under-recognized and should be among the conditions that are targeted for intervention by policymakers.”

The researchers analyzed data on sepsis admissions for adults 18 years of age and older at all California hospitals from 2009 through 2011. The team also analyzed data for congestive heart failure and heart attack admissions during the same period.

There were 240,198 admissions for sepsis, 193,153 for congestive heart failure, and 105,684 for heart attacks. The all-cause, 30-day readmission rate was 20.4% for sepsis, 23.6% for congestive heart failure, and 17.7% for heart attacks.

Patients with sepsis were readmitted because of respiratory failure; pneumonia; urinary tract infections; renal infections; renal failure; intestinal infections; complications with devices, implants, or grafts; and other causes.

Sepsis readmission rates were higher among young adults than older adults, among men than women, among black and Native American patients than other racial groups, and among lower-income patients than those with higher incomes. In addition, patients with other concurrent health problems were more likely to be readmitted than those with sepsis alone.

The estimated annual cost of sepsis-related readmissions in California during the study period was $500 million, compared with $229 million for congestive heart failure and $142 million for heart attacks.

“These findings suggest that efforts to reduce hospital readmissions need to include sepsis prominently, at least on par with heart failure and myocardial infarction,” said study author Martin Shapiro, MD, PhD, of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

Next, the researchers plan to examine why patients are readmitted after sepsis and the percentage of those readmissions that are due to processes that can be improved upon, such as discharge practices, follow-up care, and teaching patients how to take their medications. ![]()

Early progression predicts overall survival in FL

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The goal for many cancer patients is to reach the 5-year mark without progression, but a new study suggests 2 years might be a more appropriate goal for patients with follicular lymphoma (FL).

Previous research indicated that about 20% of FL patients relapse within 2 years of treatment.

Now, researchers have found these patients have a significantly worse 5-year survival rate than patients who make it past the 2-year mark without progressing.

Carla Casulo, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, and her colleagues recounted these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The team analyzed data from 588 patients with stage 2-4 FL who received first-line therapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP).

These patients could be separated into 2 groups: those with disease progression within 2 years of diagnosis (19%, n=110) and those who did not progress within the 2-year period (71%, n=420).

Eight percent of patients (n=46) were lost to follow-up, and 2% (n=12) died of causes other than progression within the 2-year period.

At 2 years, the overall survival (OS) rate was 68% in the early progression group and 97% in the group that did not progress. At 5 years, OS rates were 50% and 90%, respectively.

In unadjusted Cox regression analysis, early progression was associated with lower OS (hazard ratio[HR]=7.17). The same was true after the researchers adjusted for FLIPI score (HR=6.44).

The team observed similar results in a validation cohort of 147 FL patients who received first-line R-CHOP. At 2 years, the OS rate was 64% in the early progression group and 98% in the group that did not progress. At 5 years, OS rates were 34% and 94%, respectively.

Again, in an unadjusted analysis, early progression was associated with lower OS (HR=20.0). And this trend was maintained after the researchers adjusted for FLIPI score (HR=19.8).

The researchers also found that, for patients in the early progression group, clinical factors that were predictive of inferior OS were age, ECOG performance score, nodal sites, and disease stage. For the group that did not progress within 2 years, clinical factors that were predictive of OS were age and extranodal sites.

In a Cox regression analysis that encompassed these factors and early progression, only early progression, age, and ECOG performance scores remained significantly predictive of OS.

“[W]e have confirmed that all relapsed patients are not equal and therefore should not be approached the same at diagnosis, nor at the time of relapse, in terms of therapies,” Dr Casulo said.

“It will be critical to predict who is most likely to relapse early. We believe that targeted sequencing or gene-expression profiling will be important to understanding how to improve the outcomes of this group.” ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The goal for many cancer patients is to reach the 5-year mark without progression, but a new study suggests 2 years might be a more appropriate goal for patients with follicular lymphoma (FL).

Previous research indicated that about 20% of FL patients relapse within 2 years of treatment.

Now, researchers have found these patients have a significantly worse 5-year survival rate than patients who make it past the 2-year mark without progressing.

Carla Casulo, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, and her colleagues recounted these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The team analyzed data from 588 patients with stage 2-4 FL who received first-line therapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP).

These patients could be separated into 2 groups: those with disease progression within 2 years of diagnosis (19%, n=110) and those who did not progress within the 2-year period (71%, n=420).

Eight percent of patients (n=46) were lost to follow-up, and 2% (n=12) died of causes other than progression within the 2-year period.

At 2 years, the overall survival (OS) rate was 68% in the early progression group and 97% in the group that did not progress. At 5 years, OS rates were 50% and 90%, respectively.

In unadjusted Cox regression analysis, early progression was associated with lower OS (hazard ratio[HR]=7.17). The same was true after the researchers adjusted for FLIPI score (HR=6.44).

The team observed similar results in a validation cohort of 147 FL patients who received first-line R-CHOP. At 2 years, the OS rate was 64% in the early progression group and 98% in the group that did not progress. At 5 years, OS rates were 34% and 94%, respectively.

Again, in an unadjusted analysis, early progression was associated with lower OS (HR=20.0). And this trend was maintained after the researchers adjusted for FLIPI score (HR=19.8).

The researchers also found that, for patients in the early progression group, clinical factors that were predictive of inferior OS were age, ECOG performance score, nodal sites, and disease stage. For the group that did not progress within 2 years, clinical factors that were predictive of OS were age and extranodal sites.

In a Cox regression analysis that encompassed these factors and early progression, only early progression, age, and ECOG performance scores remained significantly predictive of OS.

“[W]e have confirmed that all relapsed patients are not equal and therefore should not be approached the same at diagnosis, nor at the time of relapse, in terms of therapies,” Dr Casulo said.

“It will be critical to predict who is most likely to relapse early. We believe that targeted sequencing or gene-expression profiling will be important to understanding how to improve the outcomes of this group.” ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The goal for many cancer patients is to reach the 5-year mark without progression, but a new study suggests 2 years might be a more appropriate goal for patients with follicular lymphoma (FL).

Previous research indicated that about 20% of FL patients relapse within 2 years of treatment.

Now, researchers have found these patients have a significantly worse 5-year survival rate than patients who make it past the 2-year mark without progressing.

Carla Casulo, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, and her colleagues recounted these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The team analyzed data from 588 patients with stage 2-4 FL who received first-line therapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP).

These patients could be separated into 2 groups: those with disease progression within 2 years of diagnosis (19%, n=110) and those who did not progress within the 2-year period (71%, n=420).

Eight percent of patients (n=46) were lost to follow-up, and 2% (n=12) died of causes other than progression within the 2-year period.

At 2 years, the overall survival (OS) rate was 68% in the early progression group and 97% in the group that did not progress. At 5 years, OS rates were 50% and 90%, respectively.

In unadjusted Cox regression analysis, early progression was associated with lower OS (hazard ratio[HR]=7.17). The same was true after the researchers adjusted for FLIPI score (HR=6.44).

The team observed similar results in a validation cohort of 147 FL patients who received first-line R-CHOP. At 2 years, the OS rate was 64% in the early progression group and 98% in the group that did not progress. At 5 years, OS rates were 34% and 94%, respectively.

Again, in an unadjusted analysis, early progression was associated with lower OS (HR=20.0). And this trend was maintained after the researchers adjusted for FLIPI score (HR=19.8).

The researchers also found that, for patients in the early progression group, clinical factors that were predictive of inferior OS were age, ECOG performance score, nodal sites, and disease stage. For the group that did not progress within 2 years, clinical factors that were predictive of OS were age and extranodal sites.

In a Cox regression analysis that encompassed these factors and early progression, only early progression, age, and ECOG performance scores remained significantly predictive of OS.

“[W]e have confirmed that all relapsed patients are not equal and therefore should not be approached the same at diagnosis, nor at the time of relapse, in terms of therapies,” Dr Casulo said.

“It will be critical to predict who is most likely to relapse early. We believe that targeted sequencing or gene-expression profiling will be important to understanding how to improve the outcomes of this group.” ![]()

Interim PET results guide ongoing therapy in Hodgkin lymphoma

Bleomycin can be eliminated after two cycles of the ABVD chemotherapeutic regimen based on a negative interim PET scan finding in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, according to the 3-year findings of the RATHL study.

Being able to omit bleomycin after a negative interim PET scan was associated with a lower rate of pulmonary toxicity, but no loss in efficacy. For patients with positive interim PET scans, a more aggressive therapy was associated with good outcomes, suggesting that response-adapted therapy can yield good results, Dr. Peter Johnson said at the International Congress on Malignant Lymphoma in Lugano, Switzerland.

In the large international RATHL study (Response-Adapted Therapy in Hodgkin Lymphoma study) 1,137 adults with newly diagnosed disease (41% stage II, 31% stage III, 28% stage IV) underwent PET-CT scans at baseline and after completing two cycles of ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine). The patients’ PET images were centrally reviewed using a 5-point scale as either negative (1-3) or positive (4-5),

The majority of patients (84%) had negative scans after two cycles of the ABVD regimen and were randomized to receive four additional cycles either with or without bleomycin (ABVD or AVD). Consolidation radiotherapy was not advised for patients whose interim PET scans were negative, regardless of baseline bulk or residual masses, Dr. Johnson, of the Cancer Research UK Centre at University of Southampton, England, reported.

Patients with positive interim PET scans received escalated therapy with a BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin [Adriamycin], cyclophosphamide, vincristine [Oncovin], procarbazine, prednisolone) regimen. They received either eBEACOPP and BEASCOPP-14.

At the 3-year follow-up, progression-free survival in the PET-negative group was 85% for both the ABVD- and AVD-treated patients. Similarly, overall survival was 97% for both groups.

Factors that predicted treatment failure after a negative interim PET scan were initial tumor stage and international prognostic score, but not bulk, B symptoms, or score of the interim PET scan.

ABVD was associated with more pulmonary toxicity than was AVD.

Of 174 patients who had a positive interim PET scan and received escalated therapy, 74% had a subsequent negative PET scan after treatment. Their 3-year, progression-free survival rate was 68%, and their overall survival was 86% with no difference in outcome between two variations of BEACOPP (eBEACOPP and BEASCOPP-14).

Of the 53 deaths in the study, 19 were caused by Hodgkin lymphoma. The overall 3-year progression-free survival is 83%, and overall survival is 95%.

The results of the RATHL study have important implications for therapy of Hodgkin lymphoma, Dr. Johnson stated. First, interim PET scans are highly predictive for response to ABVD, providing valuable prognostic information to support decisions related to escalation of therapy. Secondly, after two cycles of ABVD, “it is safe to omit bleomycin from subsequent cycles, without consolidation radiotherapy,” he reported.

Omitting bleomycin has the potential to reduce pulmonary toxicity from chemotherapy, especially dyspnea, thromboembolism, and neutropenic fever, Dr. Johnson added. In the RATHL study, rates of pulmonary toxicity were significantly higher in the group receiving bleomycin.

This large randomized phase 3 RATHL trial has practice changing implications for advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma. This trial had a simple straightforward design uniting two themes in Hodgkin research: (1) desire to minimizeor omit bleomycin due to its somewhat unpredictable pulmonary toxicity; and (2) utilizing early PET response- adapted strategies, though most such studies have focused on early stage patients. This trial demonstrates that patients with advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma who achieve PET negativity after 2 cycles of ABVD, representing 84% of patients, do not need to be exposed to bleomycin during the last 4 cycles, reducing pulmonary toxicity. This has immediate clinical utility. Whether this can be extrapolated to early stage patients remains an interesting research question.

This large randomized phase 3 RATHL trial has practice changing implications for advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma. This trial had a simple straightforward design uniting two themes in Hodgkin research: (1) desire to minimizeor omit bleomycin due to its somewhat unpredictable pulmonary toxicity; and (2) utilizing early PET response- adapted strategies, though most such studies have focused on early stage patients. This trial demonstrates that patients with advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma who achieve PET negativity after 2 cycles of ABVD, representing 84% of patients, do not need to be exposed to bleomycin during the last 4 cycles, reducing pulmonary toxicity. This has immediate clinical utility. Whether this can be extrapolated to early stage patients remains an interesting research question.

This large randomized phase 3 RATHL trial has practice changing implications for advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma. This trial had a simple straightforward design uniting two themes in Hodgkin research: (1) desire to minimizeor omit bleomycin due to its somewhat unpredictable pulmonary toxicity; and (2) utilizing early PET response- adapted strategies, though most such studies have focused on early stage patients. This trial demonstrates that patients with advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma who achieve PET negativity after 2 cycles of ABVD, representing 84% of patients, do not need to be exposed to bleomycin during the last 4 cycles, reducing pulmonary toxicity. This has immediate clinical utility. Whether this can be extrapolated to early stage patients remains an interesting research question.

Bleomycin can be eliminated after two cycles of the ABVD chemotherapeutic regimen based on a negative interim PET scan finding in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, according to the 3-year findings of the RATHL study.

Being able to omit bleomycin after a negative interim PET scan was associated with a lower rate of pulmonary toxicity, but no loss in efficacy. For patients with positive interim PET scans, a more aggressive therapy was associated with good outcomes, suggesting that response-adapted therapy can yield good results, Dr. Peter Johnson said at the International Congress on Malignant Lymphoma in Lugano, Switzerland.

In the large international RATHL study (Response-Adapted Therapy in Hodgkin Lymphoma study) 1,137 adults with newly diagnosed disease (41% stage II, 31% stage III, 28% stage IV) underwent PET-CT scans at baseline and after completing two cycles of ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine). The patients’ PET images were centrally reviewed using a 5-point scale as either negative (1-3) or positive (4-5),

The majority of patients (84%) had negative scans after two cycles of the ABVD regimen and were randomized to receive four additional cycles either with or without bleomycin (ABVD or AVD). Consolidation radiotherapy was not advised for patients whose interim PET scans were negative, regardless of baseline bulk or residual masses, Dr. Johnson, of the Cancer Research UK Centre at University of Southampton, England, reported.

Patients with positive interim PET scans received escalated therapy with a BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin [Adriamycin], cyclophosphamide, vincristine [Oncovin], procarbazine, prednisolone) regimen. They received either eBEACOPP and BEASCOPP-14.

At the 3-year follow-up, progression-free survival in the PET-negative group was 85% for both the ABVD- and AVD-treated patients. Similarly, overall survival was 97% for both groups.

Factors that predicted treatment failure after a negative interim PET scan were initial tumor stage and international prognostic score, but not bulk, B symptoms, or score of the interim PET scan.

ABVD was associated with more pulmonary toxicity than was AVD.

Of 174 patients who had a positive interim PET scan and received escalated therapy, 74% had a subsequent negative PET scan after treatment. Their 3-year, progression-free survival rate was 68%, and their overall survival was 86% with no difference in outcome between two variations of BEACOPP (eBEACOPP and BEASCOPP-14).

Of the 53 deaths in the study, 19 were caused by Hodgkin lymphoma. The overall 3-year progression-free survival is 83%, and overall survival is 95%.

The results of the RATHL study have important implications for therapy of Hodgkin lymphoma, Dr. Johnson stated. First, interim PET scans are highly predictive for response to ABVD, providing valuable prognostic information to support decisions related to escalation of therapy. Secondly, after two cycles of ABVD, “it is safe to omit bleomycin from subsequent cycles, without consolidation radiotherapy,” he reported.

Omitting bleomycin has the potential to reduce pulmonary toxicity from chemotherapy, especially dyspnea, thromboembolism, and neutropenic fever, Dr. Johnson added. In the RATHL study, rates of pulmonary toxicity were significantly higher in the group receiving bleomycin.

Bleomycin can be eliminated after two cycles of the ABVD chemotherapeutic regimen based on a negative interim PET scan finding in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, according to the 3-year findings of the RATHL study.

Being able to omit bleomycin after a negative interim PET scan was associated with a lower rate of pulmonary toxicity, but no loss in efficacy. For patients with positive interim PET scans, a more aggressive therapy was associated with good outcomes, suggesting that response-adapted therapy can yield good results, Dr. Peter Johnson said at the International Congress on Malignant Lymphoma in Lugano, Switzerland.

In the large international RATHL study (Response-Adapted Therapy in Hodgkin Lymphoma study) 1,137 adults with newly diagnosed disease (41% stage II, 31% stage III, 28% stage IV) underwent PET-CT scans at baseline and after completing two cycles of ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine). The patients’ PET images were centrally reviewed using a 5-point scale as either negative (1-3) or positive (4-5),

The majority of patients (84%) had negative scans after two cycles of the ABVD regimen and were randomized to receive four additional cycles either with or without bleomycin (ABVD or AVD). Consolidation radiotherapy was not advised for patients whose interim PET scans were negative, regardless of baseline bulk or residual masses, Dr. Johnson, of the Cancer Research UK Centre at University of Southampton, England, reported.

Patients with positive interim PET scans received escalated therapy with a BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin [Adriamycin], cyclophosphamide, vincristine [Oncovin], procarbazine, prednisolone) regimen. They received either eBEACOPP and BEASCOPP-14.

At the 3-year follow-up, progression-free survival in the PET-negative group was 85% for both the ABVD- and AVD-treated patients. Similarly, overall survival was 97% for both groups.

Factors that predicted treatment failure after a negative interim PET scan were initial tumor stage and international prognostic score, but not bulk, B symptoms, or score of the interim PET scan.

ABVD was associated with more pulmonary toxicity than was AVD.

Of 174 patients who had a positive interim PET scan and received escalated therapy, 74% had a subsequent negative PET scan after treatment. Their 3-year, progression-free survival rate was 68%, and their overall survival was 86% with no difference in outcome between two variations of BEACOPP (eBEACOPP and BEASCOPP-14).

Of the 53 deaths in the study, 19 were caused by Hodgkin lymphoma. The overall 3-year progression-free survival is 83%, and overall survival is 95%.

The results of the RATHL study have important implications for therapy of Hodgkin lymphoma, Dr. Johnson stated. First, interim PET scans are highly predictive for response to ABVD, providing valuable prognostic information to support decisions related to escalation of therapy. Secondly, after two cycles of ABVD, “it is safe to omit bleomycin from subsequent cycles, without consolidation radiotherapy,” he reported.

Omitting bleomycin has the potential to reduce pulmonary toxicity from chemotherapy, especially dyspnea, thromboembolism, and neutropenic fever, Dr. Johnson added. In the RATHL study, rates of pulmonary toxicity were significantly higher in the group receiving bleomycin.

AT 13-ICML

Key clinical point: Bleomycin can be eliminated after two cycles of the ABVD chemotherapeutic regimen based on a negative interim PET scan finding in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Major finding: At the 3-year follow-up, progression-free survival in the PET-negative group was 85% for both the ABVD- and AVD-treated patients. Similarly, overall survival was 97% for both groups.

Data source: The international RATHL study (Response-Adapted Therapy in Hodgkin Lymphoma study).

Disclosures: The study was supported by Cancer Research UK, Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre (ECMC), and the National Institute for Health Research Cancer Research Network (NCRN). The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

Listen Now: Teaching Value-Based Care: A Med-Ed Perspective

Adolescent cancer survivors report more emotional, neurocognitive impairment than do siblings

Adult survivors of cancer who were diagnosed between the ages of 11 and 21 years self-reported higher rates of impairment in emotional and neurocognitive outcomes compared with their sibling counterparts, according to researchers.

Compared with siblings, survivors reported greater anxiety (odds ratio [OR], 2.0; 95% CI, 1.17-3.43), somatization (2.36; 1.55-3.60), and depression (1.55; 1.04-2.30). Higher rates of neurocognitive problems included task efficiency (1.72; 1.21-2.43), emotional regulation (1.74; 1.26-2.40), and memory (1.44; 1.09-1.89). Survivors were significantly less likely to be employed (P < .001).

Previous reports have shown that survivors of childhood cancers have increased risk for impaired neurocognitive functioning, but this is the first study to examine outcomes in survivors who were diagnosed during adolescence and early young adulthood.

“Cancer treatment during this time has the potential to interfere with adolescents’ separation from caregivers, autonomy with regard to planning social and academic schedules, participation in social activities, and maintaining privacy, particularly of their bodies,” wrote Dr. Pinki Prasad, assistant professor of pediatrics at Louisiana State University, New Orleans.

Survivors who were diagnosed with CNS tumors or leukemia during adolescence reported rates of emotional distress and neurocognitive dysfunction similar to rates of those diagnosed during early childhood, whereas diagnoses of lymphoma/sarcoma during adolescence resulted in lower risk of impairment compared with early childhood diagnoses. This may be due to the fact that the leukemia/CNS tumor group was more likely to receive cranial radiation therapy, a predictor of neurocognitive late effects, Dr. Prasad and colleagues wrote (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 July 6 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.57.7528]).

Among those diagnosed with lymphomas or sarcomas during adolescence, treatment with corticosteroids was associated with greater risk of self-reported difficulties with somatization, anxiety, task efficiency, and memory.

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) is a multicenter, retrospective cohort study that comprised 2,589 survivors who were diagnosed from 1970 through 1986 when they were between the ages 11 and 21 years, and 360 sibling counterparts. Participants completed the Brief Symptom Inventory–18, which measures symptoms of emotional distress, and the CCSS Neurocognitive Questionnaire.

The authors noted that the results indicate “high rates of self-reported impairment in neurocognitive function and psychological distress that are associated with limitation in development of adult social milestones,” and that further follow-up with survivors of adolescent and early young adult cancers may be necessary.

Adult survivors of cancer who were diagnosed between the ages of 11 and 21 years self-reported higher rates of impairment in emotional and neurocognitive outcomes compared with their sibling counterparts, according to researchers.

Compared with siblings, survivors reported greater anxiety (odds ratio [OR], 2.0; 95% CI, 1.17-3.43), somatization (2.36; 1.55-3.60), and depression (1.55; 1.04-2.30). Higher rates of neurocognitive problems included task efficiency (1.72; 1.21-2.43), emotional regulation (1.74; 1.26-2.40), and memory (1.44; 1.09-1.89). Survivors were significantly less likely to be employed (P < .001).

Previous reports have shown that survivors of childhood cancers have increased risk for impaired neurocognitive functioning, but this is the first study to examine outcomes in survivors who were diagnosed during adolescence and early young adulthood.

“Cancer treatment during this time has the potential to interfere with adolescents’ separation from caregivers, autonomy with regard to planning social and academic schedules, participation in social activities, and maintaining privacy, particularly of their bodies,” wrote Dr. Pinki Prasad, assistant professor of pediatrics at Louisiana State University, New Orleans.

Survivors who were diagnosed with CNS tumors or leukemia during adolescence reported rates of emotional distress and neurocognitive dysfunction similar to rates of those diagnosed during early childhood, whereas diagnoses of lymphoma/sarcoma during adolescence resulted in lower risk of impairment compared with early childhood diagnoses. This may be due to the fact that the leukemia/CNS tumor group was more likely to receive cranial radiation therapy, a predictor of neurocognitive late effects, Dr. Prasad and colleagues wrote (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 July 6 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.57.7528]).

Among those diagnosed with lymphomas or sarcomas during adolescence, treatment with corticosteroids was associated with greater risk of self-reported difficulties with somatization, anxiety, task efficiency, and memory.

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) is a multicenter, retrospective cohort study that comprised 2,589 survivors who were diagnosed from 1970 through 1986 when they were between the ages 11 and 21 years, and 360 sibling counterparts. Participants completed the Brief Symptom Inventory–18, which measures symptoms of emotional distress, and the CCSS Neurocognitive Questionnaire.

The authors noted that the results indicate “high rates of self-reported impairment in neurocognitive function and psychological distress that are associated with limitation in development of adult social milestones,” and that further follow-up with survivors of adolescent and early young adult cancers may be necessary.

Adult survivors of cancer who were diagnosed between the ages of 11 and 21 years self-reported higher rates of impairment in emotional and neurocognitive outcomes compared with their sibling counterparts, according to researchers.

Compared with siblings, survivors reported greater anxiety (odds ratio [OR], 2.0; 95% CI, 1.17-3.43), somatization (2.36; 1.55-3.60), and depression (1.55; 1.04-2.30). Higher rates of neurocognitive problems included task efficiency (1.72; 1.21-2.43), emotional regulation (1.74; 1.26-2.40), and memory (1.44; 1.09-1.89). Survivors were significantly less likely to be employed (P < .001).

Previous reports have shown that survivors of childhood cancers have increased risk for impaired neurocognitive functioning, but this is the first study to examine outcomes in survivors who were diagnosed during adolescence and early young adulthood.

“Cancer treatment during this time has the potential to interfere with adolescents’ separation from caregivers, autonomy with regard to planning social and academic schedules, participation in social activities, and maintaining privacy, particularly of their bodies,” wrote Dr. Pinki Prasad, assistant professor of pediatrics at Louisiana State University, New Orleans.

Survivors who were diagnosed with CNS tumors or leukemia during adolescence reported rates of emotional distress and neurocognitive dysfunction similar to rates of those diagnosed during early childhood, whereas diagnoses of lymphoma/sarcoma during adolescence resulted in lower risk of impairment compared with early childhood diagnoses. This may be due to the fact that the leukemia/CNS tumor group was more likely to receive cranial radiation therapy, a predictor of neurocognitive late effects, Dr. Prasad and colleagues wrote (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 July 6 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.57.7528]).

Among those diagnosed with lymphomas or sarcomas during adolescence, treatment with corticosteroids was associated with greater risk of self-reported difficulties with somatization, anxiety, task efficiency, and memory.

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) is a multicenter, retrospective cohort study that comprised 2,589 survivors who were diagnosed from 1970 through 1986 when they were between the ages 11 and 21 years, and 360 sibling counterparts. Participants completed the Brief Symptom Inventory–18, which measures symptoms of emotional distress, and the CCSS Neurocognitive Questionnaire.

The authors noted that the results indicate “high rates of self-reported impairment in neurocognitive function and psychological distress that are associated with limitation in development of adult social milestones,” and that further follow-up with survivors of adolescent and early young adult cancers may be necessary.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Adult cancer survivors diagnosed between ages 11 and 21 years self-reported higher rates of emotional distress and neurocognitive dysfunction compared with sibling counterparts.

Major finding: Compared with siblings, survivors reported greater anxiety (odds ratio, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.17-3.43), somatization (2.36; 1.55-3.60), and depression (1.55; 1.04-2.30). Higher rates of neurocognitive problems included task efficiency (1.72; 1.21-2.43), emotional regulation (1.74; 1.26-2.40), and memory (1.44; 1.09-1.89).

Data source: The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, a multicenter, retrospective cohort study of 2,589 survivors diagnosed from 1970 through 1986 when they were between the ages 11 and 21 years, and 360 sibling counterparts.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute supported the study. Dr. Prasad reported having no disclosures.

Repigmentation of Gray Hair in Lesions of Annular Elastolytic Giant Cell Granuloma

Hair pigmentation is a complex phenomenon that involves many hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, growth factors, eicosanoids, cyclic nucleotides, nutrients, and a physicochemical milieu.1 Repigmentation of gray hair has been associated with herpes zoster infection,2 use of systemic corticosteroids,3 thyroid hormone therapy,4 or treatment with interferon and ribavirin.5 We report a case of repigmentation of gray hairs in lesions of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG) on the scalp of a 67-year-old man.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of pruritic lesions on the face and scalp of 1 year’s duration. The patient reported that hairs in the involved areas of the scalp had turned from gray to a dark color since the appearance of the lesions. The patient had a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. His current medications included irbesartan, atorvastatin, metformin, acetylsalicylic acid, omeprazole, and repaglinide.

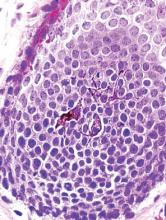

Physical examination revealed plaques on the scalp and cheeks that were 2 to 10 mm in diameter. Some of the plaques had an atrophic center and a desquamative peripheral border. The patient had androgenetic alopecia. The remaining hair was dark in the areas affected by the inflammatory plaques while it remained white-gray in the uninvolved areas (Figure 1).

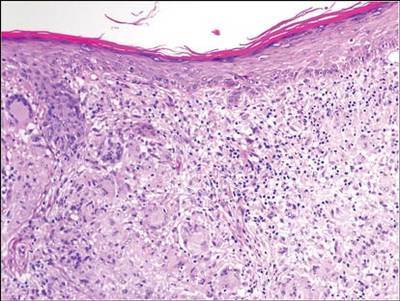

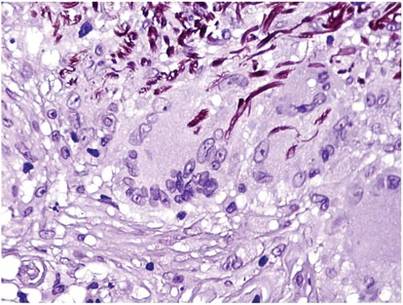

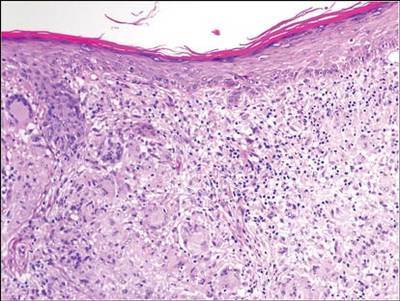

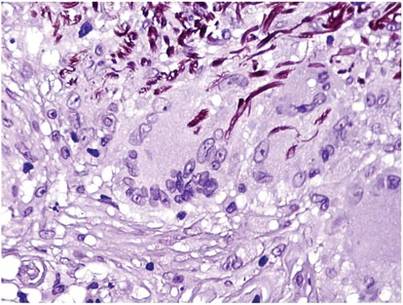

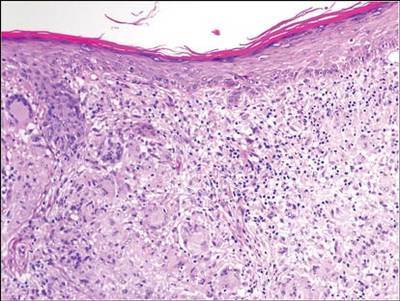

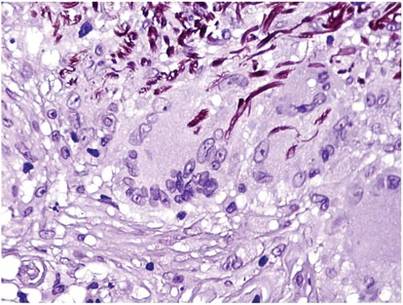

A biopsy of one of the lesions was performed. Histopathology revealed a granulomatous dermatitis involving mostly the upper and mid dermis (Figure 2). Granulomas were epithelioid with many giant cells, some of which contained many nuclei. A ringed array of nuclei was noted in some histiocytes. Elastic fibers were absent in the central zone of the granulomas, a finding that was better evidenced on orcein staining (Figure 3). On the contrary, the peripheral zone of the granulomas showed an increased amount of thick elastotic material. Elastophagocytosis was observed, but no asteroid bodies, Schaumann bodies, or mucin deposits were noted. Histochemistry for microorganisms with Ziehl-Neelsen and periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Other findings included a mild infiltrate of melanophages in the papillary dermis as well as a mild superficial dermal inflammatory infiltrate that was rich in plasma cells. Immunostaining for Treponema pallidum was negative. The lymphocytic infiltrate was CD4+predominant. A prominent dermal elastosis also was noted. Hair follicles within the plaques were small in size, penetrating just the dermis. Immunostaining for HMB-45, melan-A, and S-100 demonstrated preserved melanocytes in the hair bulbs (Figure 4). CD68 immunostaining made the infiltrate of macrophages stand out. Based on the results of the histopathologic evaluation, a diagnosis of AEGCG was made.

|

|

Comment

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is a controversial entity that was first described by O’Brien6 in 1975 as actinic granuloma. Hanke et al7 proposed the term annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma to encompass lesions previously called actinic granuloma, atypical necrobiosis lipoidica, and Miescher granuloma. Some researchers have claimed that AEGCG is an independent entity, therefore separate and distinguishable from granuloma annulare. Histopathologic clues to distinguish AEGCG from granuloma annulare have been noted in the literature.7-9 Other investigators believe AEGCG is a type of granuloma annulare that appears on exposed skin.10 There are several variants of the classic clinical presentation of AEGCG, such as cases including presentation in unexposed areas of the skin,11 a papular variant,12 a rapidly regressive variant,13 a reticular variant,14 a variant of early childhood,15 a generalized variant,16 presentation in a necklace distribution,17 presentation as alopecia,18 a sarcoid variant,19 or presentation as reticulate erythema.20 However, no variant has been associated with hair repigmentation.

Melanin units from the proximal hair bulb are responsible for pigmentation in adult hair follicles and are integrated by the hair matrix, melanocytes, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts.21 Hair bulb melanocytes are larger and more dendritic than epidermal melanocytes (Figure 5). The hair only pigments during the anagen phase; therefore, its pigmentation is cyclic, as opposed to epidermal pigmentation, which is ongoing. Hair pigmentation is the result of a complex interaction between the epithelium, the mesenchyme, and the neuroectoderm. This complex pigmentation results from the interaction between follicular melanocytes, keratinocytes, and the fibroblasts from the hair papilla.22 Hair pigmentation involves many hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, growth factors, eicosanoids, cyclic nucleotides, nutrients, and a physicochemical milieu1,23-25 (Table), and it is regulated by autocrines, paracrines, or intracrines.21 Therefore, it is likely that many environmental factors may affect hair pigmentation, which may explain why repigmentation of the hair has been seen in the setting of herpes zoster infection,2 use of systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of bullous pemphigoid,3 thyroid hormone therapy,4 treatment with interferon and ribavirin,5 porphyria cutanea tarda,26 or lentigo maligna.27 In our patient, AEGCG might have induced some changes in the dermal environment that were responsible for the repigmentation of the patient’s gray hair. It is speculated that solar radiation and other factors can transform the antigenicity of elastic fibers and induce an immune response in AEGCG.12,15 The lymphocytic infiltrate in these lesions is predominantly CD4+, as seen in our patient, which is consistent with an autoimmune hypothesis.15 Nevertheless, it most likely is too simplistic to attribute the repigmentation to the influence of just these cells.

1. Slominski A, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, et al. Melanin pigmentation in mammalian skin and its hormonal regulation. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1155-1228.

2. Adiga GU, Rehman KL, Wiernik PH. Permanent localized hair repigmentation following herpes zoster infection. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:569-570.

3. Khaled A, Trojjets S, Zeglaoui F, et al. Repigmentation of the white hair after systemic corticosteroids for bullous pemphigoid. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1018-1020.

4. Redondo P, Guzmán M, Marquina M, et al. Repigmentation of gray hair after thyroid hormone treatment [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:603-610.

5. Kavak A, Akcan Y, Korkmaz U. Hair repigmentation in a hepatitis C patient treated with interferon and ribavirin. Dermatology. 2005;211:171-172.

6. O’Brien JP. Actinic granuloma. an annular connective tissue disorder affecting sun- and heat-damaged (elastotic) skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:460-466.

7. Hanke CW, Bailin PL, Roenigk HH Jr. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. a clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of similar entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:413-421.

8. Al-Hoqail IA, Al-Ghamdi AM, Martinka M, et al. Actinic granuloma is a unique and distinct entity: a comparative study with granuloma annulare. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:209-212.

9. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282.

10. Ragaz A, Ackerman AB. Is actinic granuloma a specific condition? Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:43-50.

11. Muramatsu T, Shirai T, Yamashina Y, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: an unusual case with lesions arising in non-sun-exposed areas. J Dermatol. 1987;14:54-58.

12. Kelly BJ, Mrstik ME, Ramos-Caro FA, et al. Papular elastolytic giant cell granuloma responding to hydroxychloroquine and quinacrine. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:964-966.

13. Misago N, Ohtsuka Y, Ishii K, et al. Papular and reticular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: rapid spontaneous regression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:89-90.

14. Hinrichs R, Weiss T, Peschke E, et al. A reticular variant of elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:42-44.

15. Lee HW, Lee MW, Choi JH, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in an infant: improvement after treatment with oral tranilast andtopical pimecrolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(5, suppl 1):S244-S246.

16. Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422.

17. Meadows KP, O’Reilly MA, Harris RM, et al. Erythematous annular plaques in a necklace distribution. annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1647-1652.

18. Delgado-Jimenez Y, Perez-Gala S, Peñas PF, et al. O’Brien actinic granuloma presenting as alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:226-227.

19. Gambichler T, Herde M, Hoffmann K, et al. Sarcoid variant of actinic granuloma: is it annular sarcoidosis? Dermatology. 2001;203:353-354.

20. Bannister MJ, Rubel DM, Kossard S. Mid-dermal elastophagocytosis presenting as a persistent reticulate erythema. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:50-54.

21. Slominski A, Paus R. Melanogenesis is coupled to murine anagen: toward new concepts for the role of melanocytes and the regulation of melanogenesis in hair growth. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101(1 suppl):90S-97S.

22. Slominski A, Wortsman J, Plonka PM, et al. Hair follicle pigmentation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:13-21.

23. Hearing VJ. Biochemical control of melanogenesis and melanosomal organization. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:24-28.

24. Slominski A, Wortsman J. Neuroendocrinology of the skin [published correction appears in Endocr Rev. 2002;23:364]. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:457-487.

25. Slominski A, Wortsman J, Luger T, et al. Corticotropin releasing hormone and proopiomelanocortin involvement in the cutaneous response to stress. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:979-1020.

26. Shaffrali FC, McDonagh AJ, Messenger AG. Hair darkening in porphyria cutanea tarda. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:325-329.

27. Dummer R. Clinical picture: hair repigmentation in lentigo maligna. Lancet. 2001;357:598.

Hair pigmentation is a complex phenomenon that involves many hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, growth factors, eicosanoids, cyclic nucleotides, nutrients, and a physicochemical milieu.1 Repigmentation of gray hair has been associated with herpes zoster infection,2 use of systemic corticosteroids,3 thyroid hormone therapy,4 or treatment with interferon and ribavirin.5 We report a case of repigmentation of gray hairs in lesions of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG) on the scalp of a 67-year-old man.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of pruritic lesions on the face and scalp of 1 year’s duration. The patient reported that hairs in the involved areas of the scalp had turned from gray to a dark color since the appearance of the lesions. The patient had a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. His current medications included irbesartan, atorvastatin, metformin, acetylsalicylic acid, omeprazole, and repaglinide.

Physical examination revealed plaques on the scalp and cheeks that were 2 to 10 mm in diameter. Some of the plaques had an atrophic center and a desquamative peripheral border. The patient had androgenetic alopecia. The remaining hair was dark in the areas affected by the inflammatory plaques while it remained white-gray in the uninvolved areas (Figure 1).

A biopsy of one of the lesions was performed. Histopathology revealed a granulomatous dermatitis involving mostly the upper and mid dermis (Figure 2). Granulomas were epithelioid with many giant cells, some of which contained many nuclei. A ringed array of nuclei was noted in some histiocytes. Elastic fibers were absent in the central zone of the granulomas, a finding that was better evidenced on orcein staining (Figure 3). On the contrary, the peripheral zone of the granulomas showed an increased amount of thick elastotic material. Elastophagocytosis was observed, but no asteroid bodies, Schaumann bodies, or mucin deposits were noted. Histochemistry for microorganisms with Ziehl-Neelsen and periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Other findings included a mild infiltrate of melanophages in the papillary dermis as well as a mild superficial dermal inflammatory infiltrate that was rich in plasma cells. Immunostaining for Treponema pallidum was negative. The lymphocytic infiltrate was CD4+predominant. A prominent dermal elastosis also was noted. Hair follicles within the plaques were small in size, penetrating just the dermis. Immunostaining for HMB-45, melan-A, and S-100 demonstrated preserved melanocytes in the hair bulbs (Figure 4). CD68 immunostaining made the infiltrate of macrophages stand out. Based on the results of the histopathologic evaluation, a diagnosis of AEGCG was made.

|

|

Comment

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is a controversial entity that was first described by O’Brien6 in 1975 as actinic granuloma. Hanke et al7 proposed the term annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma to encompass lesions previously called actinic granuloma, atypical necrobiosis lipoidica, and Miescher granuloma. Some researchers have claimed that AEGCG is an independent entity, therefore separate and distinguishable from granuloma annulare. Histopathologic clues to distinguish AEGCG from granuloma annulare have been noted in the literature.7-9 Other investigators believe AEGCG is a type of granuloma annulare that appears on exposed skin.10 There are several variants of the classic clinical presentation of AEGCG, such as cases including presentation in unexposed areas of the skin,11 a papular variant,12 a rapidly regressive variant,13 a reticular variant,14 a variant of early childhood,15 a generalized variant,16 presentation in a necklace distribution,17 presentation as alopecia,18 a sarcoid variant,19 or presentation as reticulate erythema.20 However, no variant has been associated with hair repigmentation.

Melanin units from the proximal hair bulb are responsible for pigmentation in adult hair follicles and are integrated by the hair matrix, melanocytes, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts.21 Hair bulb melanocytes are larger and more dendritic than epidermal melanocytes (Figure 5). The hair only pigments during the anagen phase; therefore, its pigmentation is cyclic, as opposed to epidermal pigmentation, which is ongoing. Hair pigmentation is the result of a complex interaction between the epithelium, the mesenchyme, and the neuroectoderm. This complex pigmentation results from the interaction between follicular melanocytes, keratinocytes, and the fibroblasts from the hair papilla.22 Hair pigmentation involves many hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, growth factors, eicosanoids, cyclic nucleotides, nutrients, and a physicochemical milieu1,23-25 (Table), and it is regulated by autocrines, paracrines, or intracrines.21 Therefore, it is likely that many environmental factors may affect hair pigmentation, which may explain why repigmentation of the hair has been seen in the setting of herpes zoster infection,2 use of systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of bullous pemphigoid,3 thyroid hormone therapy,4 treatment with interferon and ribavirin,5 porphyria cutanea tarda,26 or lentigo maligna.27 In our patient, AEGCG might have induced some changes in the dermal environment that were responsible for the repigmentation of the patient’s gray hair. It is speculated that solar radiation and other factors can transform the antigenicity of elastic fibers and induce an immune response in AEGCG.12,15 The lymphocytic infiltrate in these lesions is predominantly CD4+, as seen in our patient, which is consistent with an autoimmune hypothesis.15 Nevertheless, it most likely is too simplistic to attribute the repigmentation to the influence of just these cells.

Hair pigmentation is a complex phenomenon that involves many hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, growth factors, eicosanoids, cyclic nucleotides, nutrients, and a physicochemical milieu.1 Repigmentation of gray hair has been associated with herpes zoster infection,2 use of systemic corticosteroids,3 thyroid hormone therapy,4 or treatment with interferon and ribavirin.5 We report a case of repigmentation of gray hairs in lesions of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG) on the scalp of a 67-year-old man.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of pruritic lesions on the face and scalp of 1 year’s duration. The patient reported that hairs in the involved areas of the scalp had turned from gray to a dark color since the appearance of the lesions. The patient had a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. His current medications included irbesartan, atorvastatin, metformin, acetylsalicylic acid, omeprazole, and repaglinide.

Physical examination revealed plaques on the scalp and cheeks that were 2 to 10 mm in diameter. Some of the plaques had an atrophic center and a desquamative peripheral border. The patient had androgenetic alopecia. The remaining hair was dark in the areas affected by the inflammatory plaques while it remained white-gray in the uninvolved areas (Figure 1).

A biopsy of one of the lesions was performed. Histopathology revealed a granulomatous dermatitis involving mostly the upper and mid dermis (Figure 2). Granulomas were epithelioid with many giant cells, some of which contained many nuclei. A ringed array of nuclei was noted in some histiocytes. Elastic fibers were absent in the central zone of the granulomas, a finding that was better evidenced on orcein staining (Figure 3). On the contrary, the peripheral zone of the granulomas showed an increased amount of thick elastotic material. Elastophagocytosis was observed, but no asteroid bodies, Schaumann bodies, or mucin deposits were noted. Histochemistry for microorganisms with Ziehl-Neelsen and periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Other findings included a mild infiltrate of melanophages in the papillary dermis as well as a mild superficial dermal inflammatory infiltrate that was rich in plasma cells. Immunostaining for Treponema pallidum was negative. The lymphocytic infiltrate was CD4+predominant. A prominent dermal elastosis also was noted. Hair follicles within the plaques were small in size, penetrating just the dermis. Immunostaining for HMB-45, melan-A, and S-100 demonstrated preserved melanocytes in the hair bulbs (Figure 4). CD68 immunostaining made the infiltrate of macrophages stand out. Based on the results of the histopathologic evaluation, a diagnosis of AEGCG was made.

|

|

Comment

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is a controversial entity that was first described by O’Brien6 in 1975 as actinic granuloma. Hanke et al7 proposed the term annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma to encompass lesions previously called actinic granuloma, atypical necrobiosis lipoidica, and Miescher granuloma. Some researchers have claimed that AEGCG is an independent entity, therefore separate and distinguishable from granuloma annulare. Histopathologic clues to distinguish AEGCG from granuloma annulare have been noted in the literature.7-9 Other investigators believe AEGCG is a type of granuloma annulare that appears on exposed skin.10 There are several variants of the classic clinical presentation of AEGCG, such as cases including presentation in unexposed areas of the skin,11 a papular variant,12 a rapidly regressive variant,13 a reticular variant,14 a variant of early childhood,15 a generalized variant,16 presentation in a necklace distribution,17 presentation as alopecia,18 a sarcoid variant,19 or presentation as reticulate erythema.20 However, no variant has been associated with hair repigmentation.

Melanin units from the proximal hair bulb are responsible for pigmentation in adult hair follicles and are integrated by the hair matrix, melanocytes, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts.21 Hair bulb melanocytes are larger and more dendritic than epidermal melanocytes (Figure 5). The hair only pigments during the anagen phase; therefore, its pigmentation is cyclic, as opposed to epidermal pigmentation, which is ongoing. Hair pigmentation is the result of a complex interaction between the epithelium, the mesenchyme, and the neuroectoderm. This complex pigmentation results from the interaction between follicular melanocytes, keratinocytes, and the fibroblasts from the hair papilla.22 Hair pigmentation involves many hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, growth factors, eicosanoids, cyclic nucleotides, nutrients, and a physicochemical milieu1,23-25 (Table), and it is regulated by autocrines, paracrines, or intracrines.21 Therefore, it is likely that many environmental factors may affect hair pigmentation, which may explain why repigmentation of the hair has been seen in the setting of herpes zoster infection,2 use of systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of bullous pemphigoid,3 thyroid hormone therapy,4 treatment with interferon and ribavirin,5 porphyria cutanea tarda,26 or lentigo maligna.27 In our patient, AEGCG might have induced some changes in the dermal environment that were responsible for the repigmentation of the patient’s gray hair. It is speculated that solar radiation and other factors can transform the antigenicity of elastic fibers and induce an immune response in AEGCG.12,15 The lymphocytic infiltrate in these lesions is predominantly CD4+, as seen in our patient, which is consistent with an autoimmune hypothesis.15 Nevertheless, it most likely is too simplistic to attribute the repigmentation to the influence of just these cells.

1. Slominski A, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, et al. Melanin pigmentation in mammalian skin and its hormonal regulation. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1155-1228.

2. Adiga GU, Rehman KL, Wiernik PH. Permanent localized hair repigmentation following herpes zoster infection. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:569-570.

3. Khaled A, Trojjets S, Zeglaoui F, et al. Repigmentation of the white hair after systemic corticosteroids for bullous pemphigoid. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1018-1020.

4. Redondo P, Guzmán M, Marquina M, et al. Repigmentation of gray hair after thyroid hormone treatment [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:603-610.

5. Kavak A, Akcan Y, Korkmaz U. Hair repigmentation in a hepatitis C patient treated with interferon and ribavirin. Dermatology. 2005;211:171-172.

6. O’Brien JP. Actinic granuloma. an annular connective tissue disorder affecting sun- and heat-damaged (elastotic) skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:460-466.

7. Hanke CW, Bailin PL, Roenigk HH Jr. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. a clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of similar entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:413-421.

8. Al-Hoqail IA, Al-Ghamdi AM, Martinka M, et al. Actinic granuloma is a unique and distinct entity: a comparative study with granuloma annulare. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:209-212.

9. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282.

10. Ragaz A, Ackerman AB. Is actinic granuloma a specific condition? Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:43-50.

11. Muramatsu T, Shirai T, Yamashina Y, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: an unusual case with lesions arising in non-sun-exposed areas. J Dermatol. 1987;14:54-58.

12. Kelly BJ, Mrstik ME, Ramos-Caro FA, et al. Papular elastolytic giant cell granuloma responding to hydroxychloroquine and quinacrine. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:964-966.

13. Misago N, Ohtsuka Y, Ishii K, et al. Papular and reticular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: rapid spontaneous regression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:89-90.

14. Hinrichs R, Weiss T, Peschke E, et al. A reticular variant of elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:42-44.

15. Lee HW, Lee MW, Choi JH, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in an infant: improvement after treatment with oral tranilast andtopical pimecrolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(5, suppl 1):S244-S246.

16. Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422.

17. Meadows KP, O’Reilly MA, Harris RM, et al. Erythematous annular plaques in a necklace distribution. annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1647-1652.

18. Delgado-Jimenez Y, Perez-Gala S, Peñas PF, et al. O’Brien actinic granuloma presenting as alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:226-227.

19. Gambichler T, Herde M, Hoffmann K, et al. Sarcoid variant of actinic granuloma: is it annular sarcoidosis? Dermatology. 2001;203:353-354.

20. Bannister MJ, Rubel DM, Kossard S. Mid-dermal elastophagocytosis presenting as a persistent reticulate erythema. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:50-54.

21. Slominski A, Paus R. Melanogenesis is coupled to murine anagen: toward new concepts for the role of melanocytes and the regulation of melanogenesis in hair growth. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101(1 suppl):90S-97S.

22. Slominski A, Wortsman J, Plonka PM, et al. Hair follicle pigmentation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:13-21.

23. Hearing VJ. Biochemical control of melanogenesis and melanosomal organization. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:24-28.

24. Slominski A, Wortsman J. Neuroendocrinology of the skin [published correction appears in Endocr Rev. 2002;23:364]. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:457-487.

25. Slominski A, Wortsman J, Luger T, et al. Corticotropin releasing hormone and proopiomelanocortin involvement in the cutaneous response to stress. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:979-1020.

26. Shaffrali FC, McDonagh AJ, Messenger AG. Hair darkening in porphyria cutanea tarda. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:325-329.

27. Dummer R. Clinical picture: hair repigmentation in lentigo maligna. Lancet. 2001;357:598.

1. Slominski A, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, et al. Melanin pigmentation in mammalian skin and its hormonal regulation. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1155-1228.

2. Adiga GU, Rehman KL, Wiernik PH. Permanent localized hair repigmentation following herpes zoster infection. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:569-570.

3. Khaled A, Trojjets S, Zeglaoui F, et al. Repigmentation of the white hair after systemic corticosteroids for bullous pemphigoid. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1018-1020.

4. Redondo P, Guzmán M, Marquina M, et al. Repigmentation of gray hair after thyroid hormone treatment [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:603-610.

5. Kavak A, Akcan Y, Korkmaz U. Hair repigmentation in a hepatitis C patient treated with interferon and ribavirin. Dermatology. 2005;211:171-172.

6. O’Brien JP. Actinic granuloma. an annular connective tissue disorder affecting sun- and heat-damaged (elastotic) skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:460-466.

7. Hanke CW, Bailin PL, Roenigk HH Jr. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. a clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of similar entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:413-421.

8. Al-Hoqail IA, Al-Ghamdi AM, Martinka M, et al. Actinic granuloma is a unique and distinct entity: a comparative study with granuloma annulare. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:209-212.

9. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282.

10. Ragaz A, Ackerman AB. Is actinic granuloma a specific condition? Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:43-50.

11. Muramatsu T, Shirai T, Yamashina Y, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: an unusual case with lesions arising in non-sun-exposed areas. J Dermatol. 1987;14:54-58.

12. Kelly BJ, Mrstik ME, Ramos-Caro FA, et al. Papular elastolytic giant cell granuloma responding to hydroxychloroquine and quinacrine. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:964-966.

13. Misago N, Ohtsuka Y, Ishii K, et al. Papular and reticular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: rapid spontaneous regression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:89-90.

14. Hinrichs R, Weiss T, Peschke E, et al. A reticular variant of elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:42-44.

15. Lee HW, Lee MW, Choi JH, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in an infant: improvement after treatment with oral tranilast andtopical pimecrolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(5, suppl 1):S244-S246.

16. Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422.

17. Meadows KP, O’Reilly MA, Harris RM, et al. Erythematous annular plaques in a necklace distribution. annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1647-1652.

18. Delgado-Jimenez Y, Perez-Gala S, Peñas PF, et al. O’Brien actinic granuloma presenting as alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:226-227.

19. Gambichler T, Herde M, Hoffmann K, et al. Sarcoid variant of actinic granuloma: is it annular sarcoidosis? Dermatology. 2001;203:353-354.

20. Bannister MJ, Rubel DM, Kossard S. Mid-dermal elastophagocytosis presenting as a persistent reticulate erythema. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:50-54.

21. Slominski A, Paus R. Melanogenesis is coupled to murine anagen: toward new concepts for the role of melanocytes and the regulation of melanogenesis in hair growth. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101(1 suppl):90S-97S.

22. Slominski A, Wortsman J, Plonka PM, et al. Hair follicle pigmentation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:13-21.

23. Hearing VJ. Biochemical control of melanogenesis and melanosomal organization. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:24-28.

24. Slominski A, Wortsman J. Neuroendocrinology of the skin [published correction appears in Endocr Rev. 2002;23:364]. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:457-487.

25. Slominski A, Wortsman J, Luger T, et al. Corticotropin releasing hormone and proopiomelanocortin involvement in the cutaneous response to stress. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:979-1020.

26. Shaffrali FC, McDonagh AJ, Messenger AG. Hair darkening in porphyria cutanea tarda. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:325-329.

27. Dummer R. Clinical picture: hair repigmentation in lentigo maligna. Lancet. 2001;357:598.

Practice Points

- Hair repigmentation can be a clinical clue to a subjacent inflammatory disease.