User login

Isolating Suture Slippage During Cadaveric Testing of Knotless Anchors

Knotless suture anchor fixation techniques continue to evolve as efficient, low-profile options for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR).1,2 Excellent outcomes have been reported for constructs that use knotless fixation laterally, typically in suture bridge-type configurations.2-4 Early comparative biomechanical and clinical studies have also demonstrated equivalent results for all-knotless versus conventional constructs for arthroscopic RCR.5-10 Given the increased use and availability of multiple implant designs, it is important to supplement our clinical knowledge of these devices with laboratory studies delineating the biomechanical properties of the anchors that are used to help guide appropriate clinical use of the implants in specific patient populations.

Several biomechanical studies have shown suture slippage to be the weak but crucial link in the design of knotless anchors and the most likely mode of in vivo failure.11,12 Other studies have demonstrated frequent anchor dislodgement from bone, but these analyses involved use of elderly cadaveric specimens and relatively high-force testing protocols.12,13 Because suture-retention force may have exceeded anchor resistance to pullout (imparted by weak cadaveric bone in such biomechanical settings), the focus on suture-retention properties was limited.11 It is thought that, in clinical practice, the majority of patients who undergo RCR tend not to generate the high forces (relative to resistance to bone pullout) used to cause the anchor pullouts observed in biomechanical studies, particularly in the early postoperative setting.11-15 Cadaveric testing, however, often involves use of specimens with diminished bone mineral density (BMD), relative to age, because of the illness and other factors leading to death and donation.

Using a novel testing apparatus, we isolated, analyzed, and compared suture slippage in 2 anchor designs, one with entirely press-fit suture clamping and the other reliant on an intrinsic suture-locking mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Six human cadaveric proximal humeri specimens were used for this biomechanical study. Mean (SD) age was 53.3 (5.7) years (range, 46-59 years). Middle-aged specimens were used in order to best represent the quality of bone typically encountered in RCR surgery. To approximate tissue in clinical use, we used fresh-frozen cadaver tissue. Specimens were maintained at –20°C until about 24 hours before use and then were thawed to room temperature for testing. Specimens were included only if they had a completely intact humeral head and no prior surgery or hardware placement. Before instrumentation, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry with a QDR-1000 scanner (Hologic) was used to determine BMD of all proximal humeri.

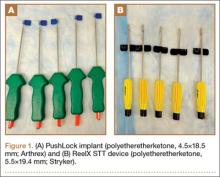

Two knotless suture anchors were compared: PushLock (4.5×18.5 mm; Arthrex) and ReelX STT (5.5×19.4 mm; Stryker). These anchors have multiple surgical indications (including RCR), allow patient-specific tissue tensioning, and use polyetheretherketone eyelets. The clamping force for PushLock depends entirely on the interference fit achieved for the suture between the outside of the anchor and the surrounding trabecular/cortical bone after device insertion, whereas the suture in ReelX is secured within the anchor shaft entirely by an internal ratchet-locking mechanism.

For anchor insertion, shoulders were dissected down to the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus, and all implants were inserted (by a fellowship-trained surgeon in accordance with manufacturer guidelines) at a 25° insertion angle with manufacturer-supplied instruments. One anchor of each type (Figure 1) was inserted into the center of the rotator cuff footprint on the greater tuberosity of each specimen. Anterior and posterior positions were randomized, and an anchor from the other group was inserted into the matching location on the contralateral matched-pair specimen. In all instances, distance between the anterior and posterior anchors was 2 cm, and anchors were placed midway between the articular margin and the lateral edge of the greater tuberosity (Figure 2). Two strands of size 2 ultrahigh-molecular-weight–polyethylene Force Fiber (Stryker) were loaded into all anchors.

A custom urethane fixture was secured over the center of each anchor to allow testing to focus on suture slippage by minimizing anchor migration (Figure 3). The small aperture of this device allowed suture tails to pass freely through the center of the fixture but prevented disengagement and proximal migration of the suture anchor from the underlying bone through contact of the urethane fixture with the anchor perimeter. Any system deformation observed during testing was restricted to the suture and/or the anchor’s suture-locking mechanism. Testing fixtures also oriented the suture anchor coaxial with the axis of tension, creating a worst-case loading scenario (Figure 3).

PushLock implants were inserted with 5 pounds of tension, as indicated, using a manufacturer-supplied suture tensioner, and ReelX devices were inserted and locked with 2 full rotations, as specified by the manufacturer. After one end of each suture was cut, as would be done in vivo, the 2 other suture ends, which would have been part of the RCR in vivo, were tied together to form an 8-cm circumference loop that was brought through the urethane fixture. Humeri were then mounted in a materials testing system (MTS 810; MTS Systems) servohydraulic load frame, and the suture loop was passed around a cross-bar on the actuator of the testing device. A mechanical testing protocol consisting of modest repetitive forces was carefully chosen to simulate expected activity during rehabilitation after RCR.15 In this protocol, a 60-second preload of 10 N was followed by tensile loading between 10 N and 90 N at a frequency of 0.5 Hz for 500 cycles.15 Cycle duration at 3 mm and 5 mm of suture slippage (threshold for clinical failure) was recorded.12,16,17 In addition, suture slippage was measured after 1, 10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 cycles. The first 5 test cycles were not counted in the analysis to control for initial knot slippage. Finally, after completion of dynamic testing, samples were loaded at a displacement rate of 0.5 mm/s for tension-to-failure testing in the custom fixtures. Maximum failure load, stiffness, and failure mode were recorded. Ultimate failure was defined as suture breakage or gross suture slippage.

Paired Student t test was used to determine significant differences in suture slippage distance between the 2 groups at various cycle durations. In addition, Kaplan-Meier survival test was used to determine statistical differences in sample survival during the dynamic loading test.

Results

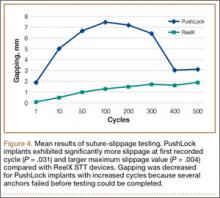

Mean (SD) BMD of the cadaveric shoulder specimens was 0.55 (0.13) g/cm2 (range, 0.29-0.68 g/cm2). The testing fixtures isolated suture slippage from anchor–bone disengagement. All 6 PushLock implants demonstrated slippage of more than 3 mm, and 5 of the 6 demonstrated slippage of more than 5 mm. All 6 ReelX devices exhibited slippage of less than 3 mm. In addition, PushLock demonstrated more suture slippage at cycles 1, 10, and 100 (P < .05) and more maximum slippage after 500 cycles (mean, 11.2 mm; SD, 4.7 mm) compared with ReelX (mean, 1.9 mm; SD, 0.5 mm) (P = .004). Figure 4 shows mean suture slippage at each cycle.

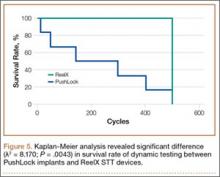

Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed significantly (λ2 = 8.170; P = .0043) decreased survival after dynamic testing for PushLock versus ReelX (Figure 5). Survival was defined as suture slippage of less than 5 mm after completion of dynamic testing. Only 1 of the 6 PushLock anchors completed dynamic testing; the other 5 failed via complete suture slippage from the anchor before testing could be completed. All 6 ReelX devices survived dynamic testing.

Therefore, 1 PushLock implant and all 6 ReelX devices were available for subsequent load-to-failure testing. Failure in this setting was defined as suture slippage of more than 10 mm or suture breakage. The PushLock implant failed at a maximum force of 171.8 N with a stiffness of 74.4 N/mm and eventually exhibited gross suture slippage. All 6 ReelX devices failed at a mean (SD) maximum of 273.5 (20.2) N, with a mean (SD) stiffness of 74.1 (17) N/mm. Mechanism of failure for all ReelX devices was suture breakage during the tensile load-to-failure test.

Discussion

We evaluated a new technique designed to isolate suture slippage in knotless anchors used for RCR. The impetus for developing this new method was to provide a means for better analyzing the ability of a knotless anchor to resist suture slippage in the cadaveric biomechanical testing setting. Suture slippage is an important mode of failure during such analyses.11,12 Significant slippage occurred in a range of implants before half the anchor–bone pullout strength was reached in a study using young bovine femoral heads.11 In another study, using young, high-BMD cadaveric humeral heads, initial slippage and maximum failure loads were equivalent among numerous devices using various suture-retention mechanisms, and suture slippage was the most common failure mode.12 Nevertheless, other biomechanical studies have demonstrated frequent failure caused by anchor pullout in elderly human cadaveric specimens with diminished BMD, often with high-force testing protocols.12,13 In the more modest-force, in vivo rehabilitative environment, suture slippage rather than anchor dislodgement may be the main failure mode.11-15

We compared the PushLock implant and its entirely press-fit suture clamping design with the ReelX device, which relies on an intrinsic suture-locking mechanism. Middle-aged (mean, 53.3 years; SD, 5.7 years) cadaveric humeri were tested under physiologically relevant biomechanical conditions to begin to help identify how relatively osteopenic bone may affect suture-retention properties for a given implant. The results showed that the study methodology prevented implant failure via anchor–bone pullout. To our knowledge, this was the first study to exclusively analyze suture slippage in knotless anchors. The findings indicated that implants that rely heavily on a tight interference fit of the suture between the anchor and the surrounding bone may exhibit early slippage and failure after RCR in middle-aged patients with relative osteopenia.11,12 However, this study also demonstrated that devices with intrinsic clamping mechanisms that do not depend on the quality of surrounding bone may better resist suture slippage. It is not clear that all knotless anchors with intrinsic locking mechanisms function equivalently. For instance, Pietschmann and colleagues12 found that 2 of 10 implants with a different internal clamping device were unable to resist failure via suture slippage, even in healthy bone. Similarly, in a study comparing ReelX devices with implants having a different internal suture-retention mechanism, ReelX failed at higher ultimate loads, and typically via anchor dislodgement, versus suture slippage in the other implants.18

It is important to note that, in the present study, the loads at which sutures broke in the intrinsic clamping anchors approached the maximum contractile force of the supraspinatus muscle (302 N).19,20 In addition, these loads were above the resistance of the rotator cuff tendon to cut out with modern suture material.21

This study’s limitations include use of an in vitro human cadaveric model that precluded analysis of the effects of postoperative healing. Biomechanical testing was also performed in a single row-type suture configuration with the rotator cuff tendon removed. Fixtures used during testing oriented the load coaxially with the axis of tension, creating a worst-case loading scenario. Although this form of testing may limit its clinical applicability, its purpose was to critically isolate how well a knotless anchor could resist suture slippage. The methods we used were also limited because the stability of the bone–anchor interface was not assessed. For patients with osteopenia, anchor pullout rather than suture slippage could be the most limiting factor for knotless anchor construct failure, and therefore further testing of both failure modes is needed. Future biomechanical studies should compare various knotless anchors’ suture-slippage characteristics in other constructs in physiologic testing orientations, including double-row and suture-bridge configurations, as well as with intact rotator cuff tendons. In addition, use of labral tape as a substitute for polyblend suture has been suggested to limit suture slippage, and this technique theoretically could have changed the results of this study.22

Conclusion

An implant with an internal ratcheting mechanism for suture retention demonstrated significantly less suture slippage in an axial tension evaluation protocol than a device reliant on interference fit of the suture between the anchor and surrounding bone. In the clinical setting, this may allow for less gap formation during the healing phase following RCR with a knotless anchor. There was also increased maximum load to failure, demonstrating an increased load until catastrophic failure using a device with a ratcheting internal locking mechanism.

1. Thal R. A knotless suture anchor. Design, function, and biomechanical testing. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):646-649.

2. Cole BJ, ElAttrache NS, Anbari A. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs: an anatomic and biomechanical rationale for different suture-anchor repair configurations. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(6):662-669.

3. Kim KC, Shin HD, Cha SM, Lee WY. Comparison of repair integrity and functional outcomes for 3 arthroscopic suture bridge rotator cuff repair techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):271-277.

4. Choi CH, Kim SK, Cho MR, et al. Functional outcomes and structural integrity after double-pulley suture bridge rotator cuff repair using serial ultrasonographic examination. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(12):1753-1763.

5. Brown BS, Cooper AD, McIff TE, Key VH, Toby EB. Initial fixation and cyclic loading stability of knotless suture anchors for rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):313-318.

6. Burkhart SS, Adams CR, Burkhart SS, Schoolfield JD. A biomechanical comparison of 2 techniques of footprint reconstruction for rotator cuff repair: the SwiveLock-FiberChain construct versus standard double-row repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(3):274-281.

7. Hepp P, Osterhoff G, Engel T, Marquass B, Klink T, Josten C. Biomechanical evaluation of knotless anatomical double-layer double-row rotator cuff repair: a comparative ex vivo study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(7):1363-1369.

8. Maguire M, Goldberg J, Bokor D, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of four different transosseous-equivalent/suture bridge rotator cuff repairs. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1582-1587.

9. Millar NL, Wu X, Tantau R, Silverstone E, Murrell GA. Open versus two forms of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(4):966-978.

10. Rhee YG, Cho NS, Parke CS. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using modified Mason-Allen medial row stitch: knotless versus knot-tying suture bridge technique. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2440-2447.

11. Wieser K, Farshad M, Vlachopoulos L, Ruffieux K, Gerber C, Meyer DC. Suture slippage in knotless suture anchors as a potential failure mechanism in rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1622-1627.

12. Pietschmann MF, Gülecyüz MF, Fieseler S, et al. Biomechanical stability of knotless suture anchors used in rotator cuff repair in healthy and osteopenic bone. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(8):1035-1044.

13. Barber FA, Hapa O, Bynum JA. Comparative testing by cyclic loading of rotator cuff suture anchors containing multiple high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(9 suppl):S134-S141.

14. Barber FA, Coons DA, Ruiz-Suarez M. Cyclic load testing of biodegradable suture anchors containing 2 high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(4):355-360.

15. Bynum CK, Lee S, Mahar A, Tasto J, Pedowitz R. Failure mode of suture anchors as a function of insertion depth. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(7):1030-1034.

16. Gerber C, Schneeberger AG, Beck M, Schlegel U. Mechanical strength of repairs of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(3):371-380.

17. Schneeberger AG, von Roll A, Kalberer F, Jacob HA, Gerber C. Mechanical strength of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair techniques: an in vitro study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(12):2152-2160.

18. Efird C, Traub S, Baldini T, et al. Knotless single-row rotator cuff repair: a comparative biomechanical study of 2 knotless suture anchors. Orthopedics. 2013;36(8):e1033-e1037.

19. Wright PB, Budoff JE, Yeh ML, Kelm ZS, Luo ZP. Strength of damaged suture: an in vitro study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(12):1270-1275.

20. Burkhart SS. A stepwise approach to arthroscopic rotator cuff repair based on biomechanical principles. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(1):82-90.

21. Bisson LJ, Manohar LM. A biomechanical comparison of the pullout strength of No. 2 FiberWire suture and 2-mm FiberWire tape in bovine rotator cuff tendons. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(11):1463-1468.

22. Burkhart SS, Denard PJ, Konicek J, Hanypsiak BT. Biomechanical validation of load-sharing rip-stop fixation for the repair of tissue-deficient rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):457-462.

Knotless suture anchor fixation techniques continue to evolve as efficient, low-profile options for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR).1,2 Excellent outcomes have been reported for constructs that use knotless fixation laterally, typically in suture bridge-type configurations.2-4 Early comparative biomechanical and clinical studies have also demonstrated equivalent results for all-knotless versus conventional constructs for arthroscopic RCR.5-10 Given the increased use and availability of multiple implant designs, it is important to supplement our clinical knowledge of these devices with laboratory studies delineating the biomechanical properties of the anchors that are used to help guide appropriate clinical use of the implants in specific patient populations.

Several biomechanical studies have shown suture slippage to be the weak but crucial link in the design of knotless anchors and the most likely mode of in vivo failure.11,12 Other studies have demonstrated frequent anchor dislodgement from bone, but these analyses involved use of elderly cadaveric specimens and relatively high-force testing protocols.12,13 Because suture-retention force may have exceeded anchor resistance to pullout (imparted by weak cadaveric bone in such biomechanical settings), the focus on suture-retention properties was limited.11 It is thought that, in clinical practice, the majority of patients who undergo RCR tend not to generate the high forces (relative to resistance to bone pullout) used to cause the anchor pullouts observed in biomechanical studies, particularly in the early postoperative setting.11-15 Cadaveric testing, however, often involves use of specimens with diminished bone mineral density (BMD), relative to age, because of the illness and other factors leading to death and donation.

Using a novel testing apparatus, we isolated, analyzed, and compared suture slippage in 2 anchor designs, one with entirely press-fit suture clamping and the other reliant on an intrinsic suture-locking mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Six human cadaveric proximal humeri specimens were used for this biomechanical study. Mean (SD) age was 53.3 (5.7) years (range, 46-59 years). Middle-aged specimens were used in order to best represent the quality of bone typically encountered in RCR surgery. To approximate tissue in clinical use, we used fresh-frozen cadaver tissue. Specimens were maintained at –20°C until about 24 hours before use and then were thawed to room temperature for testing. Specimens were included only if they had a completely intact humeral head and no prior surgery or hardware placement. Before instrumentation, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry with a QDR-1000 scanner (Hologic) was used to determine BMD of all proximal humeri.

Two knotless suture anchors were compared: PushLock (4.5×18.5 mm; Arthrex) and ReelX STT (5.5×19.4 mm; Stryker). These anchors have multiple surgical indications (including RCR), allow patient-specific tissue tensioning, and use polyetheretherketone eyelets. The clamping force for PushLock depends entirely on the interference fit achieved for the suture between the outside of the anchor and the surrounding trabecular/cortical bone after device insertion, whereas the suture in ReelX is secured within the anchor shaft entirely by an internal ratchet-locking mechanism.

For anchor insertion, shoulders were dissected down to the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus, and all implants were inserted (by a fellowship-trained surgeon in accordance with manufacturer guidelines) at a 25° insertion angle with manufacturer-supplied instruments. One anchor of each type (Figure 1) was inserted into the center of the rotator cuff footprint on the greater tuberosity of each specimen. Anterior and posterior positions were randomized, and an anchor from the other group was inserted into the matching location on the contralateral matched-pair specimen. In all instances, distance between the anterior and posterior anchors was 2 cm, and anchors were placed midway between the articular margin and the lateral edge of the greater tuberosity (Figure 2). Two strands of size 2 ultrahigh-molecular-weight–polyethylene Force Fiber (Stryker) were loaded into all anchors.

A custom urethane fixture was secured over the center of each anchor to allow testing to focus on suture slippage by minimizing anchor migration (Figure 3). The small aperture of this device allowed suture tails to pass freely through the center of the fixture but prevented disengagement and proximal migration of the suture anchor from the underlying bone through contact of the urethane fixture with the anchor perimeter. Any system deformation observed during testing was restricted to the suture and/or the anchor’s suture-locking mechanism. Testing fixtures also oriented the suture anchor coaxial with the axis of tension, creating a worst-case loading scenario (Figure 3).

PushLock implants were inserted with 5 pounds of tension, as indicated, using a manufacturer-supplied suture tensioner, and ReelX devices were inserted and locked with 2 full rotations, as specified by the manufacturer. After one end of each suture was cut, as would be done in vivo, the 2 other suture ends, which would have been part of the RCR in vivo, were tied together to form an 8-cm circumference loop that was brought through the urethane fixture. Humeri were then mounted in a materials testing system (MTS 810; MTS Systems) servohydraulic load frame, and the suture loop was passed around a cross-bar on the actuator of the testing device. A mechanical testing protocol consisting of modest repetitive forces was carefully chosen to simulate expected activity during rehabilitation after RCR.15 In this protocol, a 60-second preload of 10 N was followed by tensile loading between 10 N and 90 N at a frequency of 0.5 Hz for 500 cycles.15 Cycle duration at 3 mm and 5 mm of suture slippage (threshold for clinical failure) was recorded.12,16,17 In addition, suture slippage was measured after 1, 10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 cycles. The first 5 test cycles were not counted in the analysis to control for initial knot slippage. Finally, after completion of dynamic testing, samples were loaded at a displacement rate of 0.5 mm/s for tension-to-failure testing in the custom fixtures. Maximum failure load, stiffness, and failure mode were recorded. Ultimate failure was defined as suture breakage or gross suture slippage.

Paired Student t test was used to determine significant differences in suture slippage distance between the 2 groups at various cycle durations. In addition, Kaplan-Meier survival test was used to determine statistical differences in sample survival during the dynamic loading test.

Results

Mean (SD) BMD of the cadaveric shoulder specimens was 0.55 (0.13) g/cm2 (range, 0.29-0.68 g/cm2). The testing fixtures isolated suture slippage from anchor–bone disengagement. All 6 PushLock implants demonstrated slippage of more than 3 mm, and 5 of the 6 demonstrated slippage of more than 5 mm. All 6 ReelX devices exhibited slippage of less than 3 mm. In addition, PushLock demonstrated more suture slippage at cycles 1, 10, and 100 (P < .05) and more maximum slippage after 500 cycles (mean, 11.2 mm; SD, 4.7 mm) compared with ReelX (mean, 1.9 mm; SD, 0.5 mm) (P = .004). Figure 4 shows mean suture slippage at each cycle.

Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed significantly (λ2 = 8.170; P = .0043) decreased survival after dynamic testing for PushLock versus ReelX (Figure 5). Survival was defined as suture slippage of less than 5 mm after completion of dynamic testing. Only 1 of the 6 PushLock anchors completed dynamic testing; the other 5 failed via complete suture slippage from the anchor before testing could be completed. All 6 ReelX devices survived dynamic testing.

Therefore, 1 PushLock implant and all 6 ReelX devices were available for subsequent load-to-failure testing. Failure in this setting was defined as suture slippage of more than 10 mm or suture breakage. The PushLock implant failed at a maximum force of 171.8 N with a stiffness of 74.4 N/mm and eventually exhibited gross suture slippage. All 6 ReelX devices failed at a mean (SD) maximum of 273.5 (20.2) N, with a mean (SD) stiffness of 74.1 (17) N/mm. Mechanism of failure for all ReelX devices was suture breakage during the tensile load-to-failure test.

Discussion

We evaluated a new technique designed to isolate suture slippage in knotless anchors used for RCR. The impetus for developing this new method was to provide a means for better analyzing the ability of a knotless anchor to resist suture slippage in the cadaveric biomechanical testing setting. Suture slippage is an important mode of failure during such analyses.11,12 Significant slippage occurred in a range of implants before half the anchor–bone pullout strength was reached in a study using young bovine femoral heads.11 In another study, using young, high-BMD cadaveric humeral heads, initial slippage and maximum failure loads were equivalent among numerous devices using various suture-retention mechanisms, and suture slippage was the most common failure mode.12 Nevertheless, other biomechanical studies have demonstrated frequent failure caused by anchor pullout in elderly human cadaveric specimens with diminished BMD, often with high-force testing protocols.12,13 In the more modest-force, in vivo rehabilitative environment, suture slippage rather than anchor dislodgement may be the main failure mode.11-15

We compared the PushLock implant and its entirely press-fit suture clamping design with the ReelX device, which relies on an intrinsic suture-locking mechanism. Middle-aged (mean, 53.3 years; SD, 5.7 years) cadaveric humeri were tested under physiologically relevant biomechanical conditions to begin to help identify how relatively osteopenic bone may affect suture-retention properties for a given implant. The results showed that the study methodology prevented implant failure via anchor–bone pullout. To our knowledge, this was the first study to exclusively analyze suture slippage in knotless anchors. The findings indicated that implants that rely heavily on a tight interference fit of the suture between the anchor and the surrounding bone may exhibit early slippage and failure after RCR in middle-aged patients with relative osteopenia.11,12 However, this study also demonstrated that devices with intrinsic clamping mechanisms that do not depend on the quality of surrounding bone may better resist suture slippage. It is not clear that all knotless anchors with intrinsic locking mechanisms function equivalently. For instance, Pietschmann and colleagues12 found that 2 of 10 implants with a different internal clamping device were unable to resist failure via suture slippage, even in healthy bone. Similarly, in a study comparing ReelX devices with implants having a different internal suture-retention mechanism, ReelX failed at higher ultimate loads, and typically via anchor dislodgement, versus suture slippage in the other implants.18

It is important to note that, in the present study, the loads at which sutures broke in the intrinsic clamping anchors approached the maximum contractile force of the supraspinatus muscle (302 N).19,20 In addition, these loads were above the resistance of the rotator cuff tendon to cut out with modern suture material.21

This study’s limitations include use of an in vitro human cadaveric model that precluded analysis of the effects of postoperative healing. Biomechanical testing was also performed in a single row-type suture configuration with the rotator cuff tendon removed. Fixtures used during testing oriented the load coaxially with the axis of tension, creating a worst-case loading scenario. Although this form of testing may limit its clinical applicability, its purpose was to critically isolate how well a knotless anchor could resist suture slippage. The methods we used were also limited because the stability of the bone–anchor interface was not assessed. For patients with osteopenia, anchor pullout rather than suture slippage could be the most limiting factor for knotless anchor construct failure, and therefore further testing of both failure modes is needed. Future biomechanical studies should compare various knotless anchors’ suture-slippage characteristics in other constructs in physiologic testing orientations, including double-row and suture-bridge configurations, as well as with intact rotator cuff tendons. In addition, use of labral tape as a substitute for polyblend suture has been suggested to limit suture slippage, and this technique theoretically could have changed the results of this study.22

Conclusion

An implant with an internal ratcheting mechanism for suture retention demonstrated significantly less suture slippage in an axial tension evaluation protocol than a device reliant on interference fit of the suture between the anchor and surrounding bone. In the clinical setting, this may allow for less gap formation during the healing phase following RCR with a knotless anchor. There was also increased maximum load to failure, demonstrating an increased load until catastrophic failure using a device with a ratcheting internal locking mechanism.

Knotless suture anchor fixation techniques continue to evolve as efficient, low-profile options for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR).1,2 Excellent outcomes have been reported for constructs that use knotless fixation laterally, typically in suture bridge-type configurations.2-4 Early comparative biomechanical and clinical studies have also demonstrated equivalent results for all-knotless versus conventional constructs for arthroscopic RCR.5-10 Given the increased use and availability of multiple implant designs, it is important to supplement our clinical knowledge of these devices with laboratory studies delineating the biomechanical properties of the anchors that are used to help guide appropriate clinical use of the implants in specific patient populations.

Several biomechanical studies have shown suture slippage to be the weak but crucial link in the design of knotless anchors and the most likely mode of in vivo failure.11,12 Other studies have demonstrated frequent anchor dislodgement from bone, but these analyses involved use of elderly cadaveric specimens and relatively high-force testing protocols.12,13 Because suture-retention force may have exceeded anchor resistance to pullout (imparted by weak cadaveric bone in such biomechanical settings), the focus on suture-retention properties was limited.11 It is thought that, in clinical practice, the majority of patients who undergo RCR tend not to generate the high forces (relative to resistance to bone pullout) used to cause the anchor pullouts observed in biomechanical studies, particularly in the early postoperative setting.11-15 Cadaveric testing, however, often involves use of specimens with diminished bone mineral density (BMD), relative to age, because of the illness and other factors leading to death and donation.

Using a novel testing apparatus, we isolated, analyzed, and compared suture slippage in 2 anchor designs, one with entirely press-fit suture clamping and the other reliant on an intrinsic suture-locking mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Six human cadaveric proximal humeri specimens were used for this biomechanical study. Mean (SD) age was 53.3 (5.7) years (range, 46-59 years). Middle-aged specimens were used in order to best represent the quality of bone typically encountered in RCR surgery. To approximate tissue in clinical use, we used fresh-frozen cadaver tissue. Specimens were maintained at –20°C until about 24 hours before use and then were thawed to room temperature for testing. Specimens were included only if they had a completely intact humeral head and no prior surgery or hardware placement. Before instrumentation, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry with a QDR-1000 scanner (Hologic) was used to determine BMD of all proximal humeri.

Two knotless suture anchors were compared: PushLock (4.5×18.5 mm; Arthrex) and ReelX STT (5.5×19.4 mm; Stryker). These anchors have multiple surgical indications (including RCR), allow patient-specific tissue tensioning, and use polyetheretherketone eyelets. The clamping force for PushLock depends entirely on the interference fit achieved for the suture between the outside of the anchor and the surrounding trabecular/cortical bone after device insertion, whereas the suture in ReelX is secured within the anchor shaft entirely by an internal ratchet-locking mechanism.

For anchor insertion, shoulders were dissected down to the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus, and all implants were inserted (by a fellowship-trained surgeon in accordance with manufacturer guidelines) at a 25° insertion angle with manufacturer-supplied instruments. One anchor of each type (Figure 1) was inserted into the center of the rotator cuff footprint on the greater tuberosity of each specimen. Anterior and posterior positions were randomized, and an anchor from the other group was inserted into the matching location on the contralateral matched-pair specimen. In all instances, distance between the anterior and posterior anchors was 2 cm, and anchors were placed midway between the articular margin and the lateral edge of the greater tuberosity (Figure 2). Two strands of size 2 ultrahigh-molecular-weight–polyethylene Force Fiber (Stryker) were loaded into all anchors.

A custom urethane fixture was secured over the center of each anchor to allow testing to focus on suture slippage by minimizing anchor migration (Figure 3). The small aperture of this device allowed suture tails to pass freely through the center of the fixture but prevented disengagement and proximal migration of the suture anchor from the underlying bone through contact of the urethane fixture with the anchor perimeter. Any system deformation observed during testing was restricted to the suture and/or the anchor’s suture-locking mechanism. Testing fixtures also oriented the suture anchor coaxial with the axis of tension, creating a worst-case loading scenario (Figure 3).

PushLock implants were inserted with 5 pounds of tension, as indicated, using a manufacturer-supplied suture tensioner, and ReelX devices were inserted and locked with 2 full rotations, as specified by the manufacturer. After one end of each suture was cut, as would be done in vivo, the 2 other suture ends, which would have been part of the RCR in vivo, were tied together to form an 8-cm circumference loop that was brought through the urethane fixture. Humeri were then mounted in a materials testing system (MTS 810; MTS Systems) servohydraulic load frame, and the suture loop was passed around a cross-bar on the actuator of the testing device. A mechanical testing protocol consisting of modest repetitive forces was carefully chosen to simulate expected activity during rehabilitation after RCR.15 In this protocol, a 60-second preload of 10 N was followed by tensile loading between 10 N and 90 N at a frequency of 0.5 Hz for 500 cycles.15 Cycle duration at 3 mm and 5 mm of suture slippage (threshold for clinical failure) was recorded.12,16,17 In addition, suture slippage was measured after 1, 10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 cycles. The first 5 test cycles were not counted in the analysis to control for initial knot slippage. Finally, after completion of dynamic testing, samples were loaded at a displacement rate of 0.5 mm/s for tension-to-failure testing in the custom fixtures. Maximum failure load, stiffness, and failure mode were recorded. Ultimate failure was defined as suture breakage or gross suture slippage.

Paired Student t test was used to determine significant differences in suture slippage distance between the 2 groups at various cycle durations. In addition, Kaplan-Meier survival test was used to determine statistical differences in sample survival during the dynamic loading test.

Results

Mean (SD) BMD of the cadaveric shoulder specimens was 0.55 (0.13) g/cm2 (range, 0.29-0.68 g/cm2). The testing fixtures isolated suture slippage from anchor–bone disengagement. All 6 PushLock implants demonstrated slippage of more than 3 mm, and 5 of the 6 demonstrated slippage of more than 5 mm. All 6 ReelX devices exhibited slippage of less than 3 mm. In addition, PushLock demonstrated more suture slippage at cycles 1, 10, and 100 (P < .05) and more maximum slippage after 500 cycles (mean, 11.2 mm; SD, 4.7 mm) compared with ReelX (mean, 1.9 mm; SD, 0.5 mm) (P = .004). Figure 4 shows mean suture slippage at each cycle.

Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed significantly (λ2 = 8.170; P = .0043) decreased survival after dynamic testing for PushLock versus ReelX (Figure 5). Survival was defined as suture slippage of less than 5 mm after completion of dynamic testing. Only 1 of the 6 PushLock anchors completed dynamic testing; the other 5 failed via complete suture slippage from the anchor before testing could be completed. All 6 ReelX devices survived dynamic testing.

Therefore, 1 PushLock implant and all 6 ReelX devices were available for subsequent load-to-failure testing. Failure in this setting was defined as suture slippage of more than 10 mm or suture breakage. The PushLock implant failed at a maximum force of 171.8 N with a stiffness of 74.4 N/mm and eventually exhibited gross suture slippage. All 6 ReelX devices failed at a mean (SD) maximum of 273.5 (20.2) N, with a mean (SD) stiffness of 74.1 (17) N/mm. Mechanism of failure for all ReelX devices was suture breakage during the tensile load-to-failure test.

Discussion

We evaluated a new technique designed to isolate suture slippage in knotless anchors used for RCR. The impetus for developing this new method was to provide a means for better analyzing the ability of a knotless anchor to resist suture slippage in the cadaveric biomechanical testing setting. Suture slippage is an important mode of failure during such analyses.11,12 Significant slippage occurred in a range of implants before half the anchor–bone pullout strength was reached in a study using young bovine femoral heads.11 In another study, using young, high-BMD cadaveric humeral heads, initial slippage and maximum failure loads were equivalent among numerous devices using various suture-retention mechanisms, and suture slippage was the most common failure mode.12 Nevertheless, other biomechanical studies have demonstrated frequent failure caused by anchor pullout in elderly human cadaveric specimens with diminished BMD, often with high-force testing protocols.12,13 In the more modest-force, in vivo rehabilitative environment, suture slippage rather than anchor dislodgement may be the main failure mode.11-15

We compared the PushLock implant and its entirely press-fit suture clamping design with the ReelX device, which relies on an intrinsic suture-locking mechanism. Middle-aged (mean, 53.3 years; SD, 5.7 years) cadaveric humeri were tested under physiologically relevant biomechanical conditions to begin to help identify how relatively osteopenic bone may affect suture-retention properties for a given implant. The results showed that the study methodology prevented implant failure via anchor–bone pullout. To our knowledge, this was the first study to exclusively analyze suture slippage in knotless anchors. The findings indicated that implants that rely heavily on a tight interference fit of the suture between the anchor and the surrounding bone may exhibit early slippage and failure after RCR in middle-aged patients with relative osteopenia.11,12 However, this study also demonstrated that devices with intrinsic clamping mechanisms that do not depend on the quality of surrounding bone may better resist suture slippage. It is not clear that all knotless anchors with intrinsic locking mechanisms function equivalently. For instance, Pietschmann and colleagues12 found that 2 of 10 implants with a different internal clamping device were unable to resist failure via suture slippage, even in healthy bone. Similarly, in a study comparing ReelX devices with implants having a different internal suture-retention mechanism, ReelX failed at higher ultimate loads, and typically via anchor dislodgement, versus suture slippage in the other implants.18

It is important to note that, in the present study, the loads at which sutures broke in the intrinsic clamping anchors approached the maximum contractile force of the supraspinatus muscle (302 N).19,20 In addition, these loads were above the resistance of the rotator cuff tendon to cut out with modern suture material.21

This study’s limitations include use of an in vitro human cadaveric model that precluded analysis of the effects of postoperative healing. Biomechanical testing was also performed in a single row-type suture configuration with the rotator cuff tendon removed. Fixtures used during testing oriented the load coaxially with the axis of tension, creating a worst-case loading scenario. Although this form of testing may limit its clinical applicability, its purpose was to critically isolate how well a knotless anchor could resist suture slippage. The methods we used were also limited because the stability of the bone–anchor interface was not assessed. For patients with osteopenia, anchor pullout rather than suture slippage could be the most limiting factor for knotless anchor construct failure, and therefore further testing of both failure modes is needed. Future biomechanical studies should compare various knotless anchors’ suture-slippage characteristics in other constructs in physiologic testing orientations, including double-row and suture-bridge configurations, as well as with intact rotator cuff tendons. In addition, use of labral tape as a substitute for polyblend suture has been suggested to limit suture slippage, and this technique theoretically could have changed the results of this study.22

Conclusion

An implant with an internal ratcheting mechanism for suture retention demonstrated significantly less suture slippage in an axial tension evaluation protocol than a device reliant on interference fit of the suture between the anchor and surrounding bone. In the clinical setting, this may allow for less gap formation during the healing phase following RCR with a knotless anchor. There was also increased maximum load to failure, demonstrating an increased load until catastrophic failure using a device with a ratcheting internal locking mechanism.

1. Thal R. A knotless suture anchor. Design, function, and biomechanical testing. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):646-649.

2. Cole BJ, ElAttrache NS, Anbari A. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs: an anatomic and biomechanical rationale for different suture-anchor repair configurations. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(6):662-669.

3. Kim KC, Shin HD, Cha SM, Lee WY. Comparison of repair integrity and functional outcomes for 3 arthroscopic suture bridge rotator cuff repair techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):271-277.

4. Choi CH, Kim SK, Cho MR, et al. Functional outcomes and structural integrity after double-pulley suture bridge rotator cuff repair using serial ultrasonographic examination. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(12):1753-1763.

5. Brown BS, Cooper AD, McIff TE, Key VH, Toby EB. Initial fixation and cyclic loading stability of knotless suture anchors for rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):313-318.

6. Burkhart SS, Adams CR, Burkhart SS, Schoolfield JD. A biomechanical comparison of 2 techniques of footprint reconstruction for rotator cuff repair: the SwiveLock-FiberChain construct versus standard double-row repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(3):274-281.

7. Hepp P, Osterhoff G, Engel T, Marquass B, Klink T, Josten C. Biomechanical evaluation of knotless anatomical double-layer double-row rotator cuff repair: a comparative ex vivo study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(7):1363-1369.

8. Maguire M, Goldberg J, Bokor D, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of four different transosseous-equivalent/suture bridge rotator cuff repairs. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1582-1587.

9. Millar NL, Wu X, Tantau R, Silverstone E, Murrell GA. Open versus two forms of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(4):966-978.

10. Rhee YG, Cho NS, Parke CS. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using modified Mason-Allen medial row stitch: knotless versus knot-tying suture bridge technique. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2440-2447.

11. Wieser K, Farshad M, Vlachopoulos L, Ruffieux K, Gerber C, Meyer DC. Suture slippage in knotless suture anchors as a potential failure mechanism in rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1622-1627.

12. Pietschmann MF, Gülecyüz MF, Fieseler S, et al. Biomechanical stability of knotless suture anchors used in rotator cuff repair in healthy and osteopenic bone. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(8):1035-1044.

13. Barber FA, Hapa O, Bynum JA. Comparative testing by cyclic loading of rotator cuff suture anchors containing multiple high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(9 suppl):S134-S141.

14. Barber FA, Coons DA, Ruiz-Suarez M. Cyclic load testing of biodegradable suture anchors containing 2 high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(4):355-360.

15. Bynum CK, Lee S, Mahar A, Tasto J, Pedowitz R. Failure mode of suture anchors as a function of insertion depth. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(7):1030-1034.

16. Gerber C, Schneeberger AG, Beck M, Schlegel U. Mechanical strength of repairs of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(3):371-380.

17. Schneeberger AG, von Roll A, Kalberer F, Jacob HA, Gerber C. Mechanical strength of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair techniques: an in vitro study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(12):2152-2160.

18. Efird C, Traub S, Baldini T, et al. Knotless single-row rotator cuff repair: a comparative biomechanical study of 2 knotless suture anchors. Orthopedics. 2013;36(8):e1033-e1037.

19. Wright PB, Budoff JE, Yeh ML, Kelm ZS, Luo ZP. Strength of damaged suture: an in vitro study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(12):1270-1275.

20. Burkhart SS. A stepwise approach to arthroscopic rotator cuff repair based on biomechanical principles. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(1):82-90.

21. Bisson LJ, Manohar LM. A biomechanical comparison of the pullout strength of No. 2 FiberWire suture and 2-mm FiberWire tape in bovine rotator cuff tendons. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(11):1463-1468.

22. Burkhart SS, Denard PJ, Konicek J, Hanypsiak BT. Biomechanical validation of load-sharing rip-stop fixation for the repair of tissue-deficient rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):457-462.

1. Thal R. A knotless suture anchor. Design, function, and biomechanical testing. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):646-649.

2. Cole BJ, ElAttrache NS, Anbari A. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs: an anatomic and biomechanical rationale for different suture-anchor repair configurations. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(6):662-669.

3. Kim KC, Shin HD, Cha SM, Lee WY. Comparison of repair integrity and functional outcomes for 3 arthroscopic suture bridge rotator cuff repair techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):271-277.

4. Choi CH, Kim SK, Cho MR, et al. Functional outcomes and structural integrity after double-pulley suture bridge rotator cuff repair using serial ultrasonographic examination. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(12):1753-1763.

5. Brown BS, Cooper AD, McIff TE, Key VH, Toby EB. Initial fixation and cyclic loading stability of knotless suture anchors for rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):313-318.

6. Burkhart SS, Adams CR, Burkhart SS, Schoolfield JD. A biomechanical comparison of 2 techniques of footprint reconstruction for rotator cuff repair: the SwiveLock-FiberChain construct versus standard double-row repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(3):274-281.

7. Hepp P, Osterhoff G, Engel T, Marquass B, Klink T, Josten C. Biomechanical evaluation of knotless anatomical double-layer double-row rotator cuff repair: a comparative ex vivo study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(7):1363-1369.

8. Maguire M, Goldberg J, Bokor D, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of four different transosseous-equivalent/suture bridge rotator cuff repairs. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1582-1587.

9. Millar NL, Wu X, Tantau R, Silverstone E, Murrell GA. Open versus two forms of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(4):966-978.

10. Rhee YG, Cho NS, Parke CS. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using modified Mason-Allen medial row stitch: knotless versus knot-tying suture bridge technique. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2440-2447.

11. Wieser K, Farshad M, Vlachopoulos L, Ruffieux K, Gerber C, Meyer DC. Suture slippage in knotless suture anchors as a potential failure mechanism in rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1622-1627.

12. Pietschmann MF, Gülecyüz MF, Fieseler S, et al. Biomechanical stability of knotless suture anchors used in rotator cuff repair in healthy and osteopenic bone. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(8):1035-1044.

13. Barber FA, Hapa O, Bynum JA. Comparative testing by cyclic loading of rotator cuff suture anchors containing multiple high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(9 suppl):S134-S141.

14. Barber FA, Coons DA, Ruiz-Suarez M. Cyclic load testing of biodegradable suture anchors containing 2 high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(4):355-360.

15. Bynum CK, Lee S, Mahar A, Tasto J, Pedowitz R. Failure mode of suture anchors as a function of insertion depth. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(7):1030-1034.

16. Gerber C, Schneeberger AG, Beck M, Schlegel U. Mechanical strength of repairs of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(3):371-380.

17. Schneeberger AG, von Roll A, Kalberer F, Jacob HA, Gerber C. Mechanical strength of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair techniques: an in vitro study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(12):2152-2160.

18. Efird C, Traub S, Baldini T, et al. Knotless single-row rotator cuff repair: a comparative biomechanical study of 2 knotless suture anchors. Orthopedics. 2013;36(8):e1033-e1037.

19. Wright PB, Budoff JE, Yeh ML, Kelm ZS, Luo ZP. Strength of damaged suture: an in vitro study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(12):1270-1275.

20. Burkhart SS. A stepwise approach to arthroscopic rotator cuff repair based on biomechanical principles. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(1):82-90.

21. Bisson LJ, Manohar LM. A biomechanical comparison of the pullout strength of No. 2 FiberWire suture and 2-mm FiberWire tape in bovine rotator cuff tendons. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(11):1463-1468.

22. Burkhart SS, Denard PJ, Konicek J, Hanypsiak BT. Biomechanical validation of load-sharing rip-stop fixation for the repair of tissue-deficient rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):457-462.

Second pathology review boosts diagnostic accuracy in lymphoma

In patients with newly diagnosed lymphoma and suspected lymphoma, a second pathological review found inaccuracies in the original diagnosis among 17% of more than 42,000 cases, based on data presented at the International Congress on Malignant Lymphoma in Lugano, Switzerland.

In more than 25% of all discrepancies, tumors were reclassified at the second pathology review as the result of findings from additional immunostaining and molecular studies – polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization.

In 15% of cases, diagnostic changes were expected to result in a change in patient management.

“Our study highlights the importance of specialized centralized review of lymphoma diagnosis, not only in the setting of clinical trials but also in routine clinical practice, for optimal patient management,” reported Dr. Camille Laurent of the Institut Universitaire du Cancer Oncopole, Toulouse, France.

In 2010, the French National Cancer Agency (INCa) established the Lymphopath Network, comprising 33 reference centers, to provide a review by expert hematopathologists of every newly diagnosed lymphoma or suspected lymphoma prior to treatment. These new diagnoses were entered in a central national database. Between 2010 and 2015, 42,146 samples were reviewed: 35,753 were newly diagnosed as lymphomas, while the remaining 6,393 cases included 4,610 reactive lymphoid conditions and 1,783 nonlymphoid malignancies, including especially myeloma and leukemic disorders.

Discordant diagnoses among extra-cutaneous lymphomas were carefully examined by a hematologist and recorded as major or minor depending on the expected therapeutic impact. Dr. Laurent said.

The discordance rate between the referral diagnosis and the final diagnosis was 17.2%. Small B-cell lymphomas and peripheral T-cell lymphoma subtyping were the most common discrepancies; 6.4% of discordances were due to an unspecified lymphoma diagnosis, Dr. Laurent stated.

Less than 2% of discrepancies were due to misclassifications of benign versus malignant lymphoid conditions and of Hodgkin lymphoma versus non-Hodgkin lymphoma. There were minor discrepancies (2.2%) in follicular lymphoma misgrading and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subtypes.

Given the complexity of lymphoma classification, it is not surprising that expert hematopathologists can refine diagnoses. As we progress in understanding the specific pathogenesis of lymphoma subtypes and utility of targeted therapy, it becomes even more critical to make correct diagnoses. This study reiterates the importance of expert review for many, if not all, lymphoma samples, particularly any T-cell lymphoma and non—follicular small B-cell lymphoma.

Given the complexity of lymphoma classification, it is not surprising that expert hematopathologists can refine diagnoses. As we progress in understanding the specific pathogenesis of lymphoma subtypes and utility of targeted therapy, it becomes even more critical to make correct diagnoses. This study reiterates the importance of expert review for many, if not all, lymphoma samples, particularly any T-cell lymphoma and non—follicular small B-cell lymphoma.

Given the complexity of lymphoma classification, it is not surprising that expert hematopathologists can refine diagnoses. As we progress in understanding the specific pathogenesis of lymphoma subtypes and utility of targeted therapy, it becomes even more critical to make correct diagnoses. This study reiterates the importance of expert review for many, if not all, lymphoma samples, particularly any T-cell lymphoma and non—follicular small B-cell lymphoma.

In patients with newly diagnosed lymphoma and suspected lymphoma, a second pathological review found inaccuracies in the original diagnosis among 17% of more than 42,000 cases, based on data presented at the International Congress on Malignant Lymphoma in Lugano, Switzerland.

In more than 25% of all discrepancies, tumors were reclassified at the second pathology review as the result of findings from additional immunostaining and molecular studies – polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization.

In 15% of cases, diagnostic changes were expected to result in a change in patient management.

“Our study highlights the importance of specialized centralized review of lymphoma diagnosis, not only in the setting of clinical trials but also in routine clinical practice, for optimal patient management,” reported Dr. Camille Laurent of the Institut Universitaire du Cancer Oncopole, Toulouse, France.

In 2010, the French National Cancer Agency (INCa) established the Lymphopath Network, comprising 33 reference centers, to provide a review by expert hematopathologists of every newly diagnosed lymphoma or suspected lymphoma prior to treatment. These new diagnoses were entered in a central national database. Between 2010 and 2015, 42,146 samples were reviewed: 35,753 were newly diagnosed as lymphomas, while the remaining 6,393 cases included 4,610 reactive lymphoid conditions and 1,783 nonlymphoid malignancies, including especially myeloma and leukemic disorders.

Discordant diagnoses among extra-cutaneous lymphomas were carefully examined by a hematologist and recorded as major or minor depending on the expected therapeutic impact. Dr. Laurent said.

The discordance rate between the referral diagnosis and the final diagnosis was 17.2%. Small B-cell lymphomas and peripheral T-cell lymphoma subtyping were the most common discrepancies; 6.4% of discordances were due to an unspecified lymphoma diagnosis, Dr. Laurent stated.

Less than 2% of discrepancies were due to misclassifications of benign versus malignant lymphoid conditions and of Hodgkin lymphoma versus non-Hodgkin lymphoma. There were minor discrepancies (2.2%) in follicular lymphoma misgrading and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subtypes.

In patients with newly diagnosed lymphoma and suspected lymphoma, a second pathological review found inaccuracies in the original diagnosis among 17% of more than 42,000 cases, based on data presented at the International Congress on Malignant Lymphoma in Lugano, Switzerland.

In more than 25% of all discrepancies, tumors were reclassified at the second pathology review as the result of findings from additional immunostaining and molecular studies – polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization.

In 15% of cases, diagnostic changes were expected to result in a change in patient management.

“Our study highlights the importance of specialized centralized review of lymphoma diagnosis, not only in the setting of clinical trials but also in routine clinical practice, for optimal patient management,” reported Dr. Camille Laurent of the Institut Universitaire du Cancer Oncopole, Toulouse, France.

In 2010, the French National Cancer Agency (INCa) established the Lymphopath Network, comprising 33 reference centers, to provide a review by expert hematopathologists of every newly diagnosed lymphoma or suspected lymphoma prior to treatment. These new diagnoses were entered in a central national database. Between 2010 and 2015, 42,146 samples were reviewed: 35,753 were newly diagnosed as lymphomas, while the remaining 6,393 cases included 4,610 reactive lymphoid conditions and 1,783 nonlymphoid malignancies, including especially myeloma and leukemic disorders.

Discordant diagnoses among extra-cutaneous lymphomas were carefully examined by a hematologist and recorded as major or minor depending on the expected therapeutic impact. Dr. Laurent said.

The discordance rate between the referral diagnosis and the final diagnosis was 17.2%. Small B-cell lymphomas and peripheral T-cell lymphoma subtyping were the most common discrepancies; 6.4% of discordances were due to an unspecified lymphoma diagnosis, Dr. Laurent stated.

Less than 2% of discrepancies were due to misclassifications of benign versus malignant lymphoid conditions and of Hodgkin lymphoma versus non-Hodgkin lymphoma. There were minor discrepancies (2.2%) in follicular lymphoma misgrading and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subtypes.

FROM 13-ICML

Key clinical point: A second pathological review of newly-diagnosed lymphoma or suspected lymphoma found discrepancies in 17% of cases.

Major finding: Small B-cell lymphomas and peripheral T-cell lymphoma subtyping were the most common discrepancies; 6.4% of discordances were due to an unspecified lymphoma diagnosis.

Data source: 42,146 samples from the French National Cancer Agency’s Lymphopath Network, comprising 33 reference centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Laurent had no relevant financial disclosures.

LISTEN NOW: Hospitalist, Edwin Lopez, PA-C, on Post-Acute Care in the U.S. Health System

Edwin Lopez, PA-C, of St. Elizabeth Hospital in Enumclaw, Wash., offers his views on post-acute care in the U.S. health system, and how his work as a hospitalist has expanded to the nursing home across the street.

Edwin Lopez, PA-C, of St. Elizabeth Hospital in Enumclaw, Wash., offers his views on post-acute care in the U.S. health system, and how his work as a hospitalist has expanded to the nursing home across the street.

Edwin Lopez, PA-C, of St. Elizabeth Hospital in Enumclaw, Wash., offers his views on post-acute care in the U.S. health system, and how his work as a hospitalist has expanded to the nursing home across the street.

Methotrexate could treat MPNs cheaply, team says

Photo courtesy of the

National Cancer Institute

Preclinical research suggests the antineoplastic agent methotrexate (MTX) could be used to treat patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

Experiments in Drosophila and human cell lines showed that MTX reduces JAK/STAT pathway activity and MPN-associated pathway signaling.

Researchers therefore speculated that low doses of MTX might treat MPNs as effectively as the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, but for a lower cost.

“Given that a year’s course of low-dose MTX costs around £30, the potential to repurpose MTX could provide thousands of patients with a much-needed treatment option and also generate substantial savings for healthcare systems,” said study author Martin Zeidler, DPhil, of The University of Sheffield in the UK.

He and his colleagues noted that, in comparison, ruxolitinib costs more than £40,000 per year per patient.

The researchers made this comparison and described their work with MTX in PLOS ONE.

The team used cells from the fruit fly Drosophila to screen for small molecules that suppress the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, which is central to the development of MPNs in humans. The screen suggested that MTX and a related molecule, aminopterin, suppress STAT activation.

So the researchers conducted experiments in human cell lines and found that MTX suppresses human JAK/STAT signaling without affecting other phosphorylation-dependent pathways.

The team also found that MTX significantly reduces STAT5 phosphorylation in cells expressing JAK2 V617F. However, MTX-treated cells can still respond to physiological levels of erythropoietin.

The researchers are now looking to undertake clinical trials to examine the possibility of repurposing low-dose MTX for the treatment of MPNs.

“We have the potential to revolutionize the treatment of this group of chronic diseases—a breakthrough that may ultimately represent a new treatment option able to bring relief to both patients and health funders,” Dr Zeidler said. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the

National Cancer Institute

Preclinical research suggests the antineoplastic agent methotrexate (MTX) could be used to treat patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

Experiments in Drosophila and human cell lines showed that MTX reduces JAK/STAT pathway activity and MPN-associated pathway signaling.

Researchers therefore speculated that low doses of MTX might treat MPNs as effectively as the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, but for a lower cost.

“Given that a year’s course of low-dose MTX costs around £30, the potential to repurpose MTX could provide thousands of patients with a much-needed treatment option and also generate substantial savings for healthcare systems,” said study author Martin Zeidler, DPhil, of The University of Sheffield in the UK.

He and his colleagues noted that, in comparison, ruxolitinib costs more than £40,000 per year per patient.

The researchers made this comparison and described their work with MTX in PLOS ONE.

The team used cells from the fruit fly Drosophila to screen for small molecules that suppress the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, which is central to the development of MPNs in humans. The screen suggested that MTX and a related molecule, aminopterin, suppress STAT activation.

So the researchers conducted experiments in human cell lines and found that MTX suppresses human JAK/STAT signaling without affecting other phosphorylation-dependent pathways.

The team also found that MTX significantly reduces STAT5 phosphorylation in cells expressing JAK2 V617F. However, MTX-treated cells can still respond to physiological levels of erythropoietin.

The researchers are now looking to undertake clinical trials to examine the possibility of repurposing low-dose MTX for the treatment of MPNs.

“We have the potential to revolutionize the treatment of this group of chronic diseases—a breakthrough that may ultimately represent a new treatment option able to bring relief to both patients and health funders,” Dr Zeidler said. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the

National Cancer Institute

Preclinical research suggests the antineoplastic agent methotrexate (MTX) could be used to treat patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

Experiments in Drosophila and human cell lines showed that MTX reduces JAK/STAT pathway activity and MPN-associated pathway signaling.

Researchers therefore speculated that low doses of MTX might treat MPNs as effectively as the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, but for a lower cost.

“Given that a year’s course of low-dose MTX costs around £30, the potential to repurpose MTX could provide thousands of patients with a much-needed treatment option and also generate substantial savings for healthcare systems,” said study author Martin Zeidler, DPhil, of The University of Sheffield in the UK.

He and his colleagues noted that, in comparison, ruxolitinib costs more than £40,000 per year per patient.

The researchers made this comparison and described their work with MTX in PLOS ONE.

The team used cells from the fruit fly Drosophila to screen for small molecules that suppress the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, which is central to the development of MPNs in humans. The screen suggested that MTX and a related molecule, aminopterin, suppress STAT activation.

So the researchers conducted experiments in human cell lines and found that MTX suppresses human JAK/STAT signaling without affecting other phosphorylation-dependent pathways.

The team also found that MTX significantly reduces STAT5 phosphorylation in cells expressing JAK2 V617F. However, MTX-treated cells can still respond to physiological levels of erythropoietin.

The researchers are now looking to undertake clinical trials to examine the possibility of repurposing low-dose MTX for the treatment of MPNs.

“We have the potential to revolutionize the treatment of this group of chronic diseases—a breakthrough that may ultimately represent a new treatment option able to bring relief to both patients and health funders,” Dr Zeidler said. ![]()

Healthcare professionals work while sick despite risk to patients

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Results of a small survey showed that many healthcare professionals reported to work while sick, despite recognizing that this could put their patients at risk.

About 95% of survey respondents acknowledged that working while sick puts patients at risk, but 83% of respondents said they had worked while sick at least once in the past year.

About 9% of respondents reported working while sick at least 5 times.

Julia E. Szymczak, PhD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, and her colleagues reported these results in JAMA Pediatrics alongside a related editorial.

The researchers administered an anonymous survey to attending physicians and advanced practice clinicians (APCs) at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. APCs included certified registered nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse midwives.

Overall, 280 attending physicians (61%) and 256 APCs (54.5%) responded. Most respondents (504, 95.3%) said working while sick put patients at risk.

However, 446 respondents (83.1%) reported working while sick at least once in the past year, and 50 respondents (9.3%) reported working while sick at least 5 times.

Respondents reported working with symptoms that included diarrhea, fever, and the onset of significant respiratory symptoms.

The reasons physicians and APCs worked while sick included not wanting to let colleagues down (98.7%), staffing concerns (94.9%), not wanting to let patients down (92.5%), fear of being ostracized by colleagues (64%), and concerns about the continuity of care (63.8%).

An analysis of written comments about why respondents work while sick highlighted 3 areas: challenges in identifying and arranging someone to cover their work and a lack of resources to accommodate sick leave, a strong cultural norm in the hospital to report for work unless one is extremely ill, and ambiguity about what symptoms constitute being too sick to work.

Dr Szymczak and her colleagues said this study suggests complex social and logistical factors cause healthcare workers to report to work sick. But these results could inform efforts to help workers make the right choice to keep their patients and colleagues safe while caring for themselves. ![]()

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Results of a small survey showed that many healthcare professionals reported to work while sick, despite recognizing that this could put their patients at risk.

About 95% of survey respondents acknowledged that working while sick puts patients at risk, but 83% of respondents said they had worked while sick at least once in the past year.

About 9% of respondents reported working while sick at least 5 times.

Julia E. Szymczak, PhD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, and her colleagues reported these results in JAMA Pediatrics alongside a related editorial.

The researchers administered an anonymous survey to attending physicians and advanced practice clinicians (APCs) at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. APCs included certified registered nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse midwives.

Overall, 280 attending physicians (61%) and 256 APCs (54.5%) responded. Most respondents (504, 95.3%) said working while sick put patients at risk.

However, 446 respondents (83.1%) reported working while sick at least once in the past year, and 50 respondents (9.3%) reported working while sick at least 5 times.

Respondents reported working with symptoms that included diarrhea, fever, and the onset of significant respiratory symptoms.

The reasons physicians and APCs worked while sick included not wanting to let colleagues down (98.7%), staffing concerns (94.9%), not wanting to let patients down (92.5%), fear of being ostracized by colleagues (64%), and concerns about the continuity of care (63.8%).

An analysis of written comments about why respondents work while sick highlighted 3 areas: challenges in identifying and arranging someone to cover their work and a lack of resources to accommodate sick leave, a strong cultural norm in the hospital to report for work unless one is extremely ill, and ambiguity about what symptoms constitute being too sick to work.

Dr Szymczak and her colleagues said this study suggests complex social and logistical factors cause healthcare workers to report to work sick. But these results could inform efforts to help workers make the right choice to keep their patients and colleagues safe while caring for themselves. ![]()

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Results of a small survey showed that many healthcare professionals reported to work while sick, despite recognizing that this could put their patients at risk.

About 95% of survey respondents acknowledged that working while sick puts patients at risk, but 83% of respondents said they had worked while sick at least once in the past year.

About 9% of respondents reported working while sick at least 5 times.

Julia E. Szymczak, PhD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, and her colleagues reported these results in JAMA Pediatrics alongside a related editorial.

The researchers administered an anonymous survey to attending physicians and advanced practice clinicians (APCs) at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. APCs included certified registered nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse midwives.

Overall, 280 attending physicians (61%) and 256 APCs (54.5%) responded. Most respondents (504, 95.3%) said working while sick put patients at risk.

However, 446 respondents (83.1%) reported working while sick at least once in the past year, and 50 respondents (9.3%) reported working while sick at least 5 times.

Respondents reported working with symptoms that included diarrhea, fever, and the onset of significant respiratory symptoms.

The reasons physicians and APCs worked while sick included not wanting to let colleagues down (98.7%), staffing concerns (94.9%), not wanting to let patients down (92.5%), fear of being ostracized by colleagues (64%), and concerns about the continuity of care (63.8%).

An analysis of written comments about why respondents work while sick highlighted 3 areas: challenges in identifying and arranging someone to cover their work and a lack of resources to accommodate sick leave, a strong cultural norm in the hospital to report for work unless one is extremely ill, and ambiguity about what symptoms constitute being too sick to work.

Dr Szymczak and her colleagues said this study suggests complex social and logistical factors cause healthcare workers to report to work sick. But these results could inform efforts to help workers make the right choice to keep their patients and colleagues safe while caring for themselves. ![]()

NICE supports use of apixaban for VTE

Photo courtesy of the CDC

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final guidance recommending the anticoagulant apixaban (Eliquis) as an option for treating and preventing venous thromboembolism (VTE) in adults.

According to NICE, data from the AMPLIFY and AMPLIFY-EXT studies suggest apixaban is clinically effective for treating and preventing VTE.

And cost analyses indicate that apixaban is a cost-effective use of National Health Service (NHS) resources.

NICE said apixaban should be available on the NHS within 3 months of the guidance release date. The guidance was made available in June.

Dosing

To treat deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), 10 mg of apixaban should be taken twice a day for the first 7 days, followed by 5 mg twice a day for at least 3 months.

To prevent recurrent VTE, patients who have completed 6 months of treatment for DVT or PE should take apixaban at 2.5 mg twice a day.

“[A]pixaban is the only oral anticoagulant for which the licensed dose is lower for secondary prevention than for initial treatment of VTE,” said Carole Longson, NICE Health Technology Evaluation Centre Director.

“This could also be of potential benefit in terms of reducing the risk of bleeding where treatment is continued and therefore increase the chance that a person would take apixaban long-term.”

Clinical effectiveness

To assess the clinical effectiveness of apixaban, a committee advising NICE evaluated data from the AMPLIFY and AMPLIFY-EXT studies.

Results of the AMPLIFY study indicated that apixaban is noninferior to standard treatment for recurrent VTE—initial parenteral enoxaparin overlapped with warfarin. Apixaban was comparable in efficacy to standard therapy and induced significantly less bleeding.

In AMPLIFY-EXT, researchers compared 12 months of treatment with apixaban at 2 doses—2.5 mg and 5 mg—to placebo in patients who had previously received anticoagulant therapy for 6 to 12 months to treat a prior VTE.

Both doses of apixaban effectively prevented VTE, VTE-related events, and death. And the incidence of bleeding events was low in all treatment arms.

The NICE committee noted that there were limited data in these trials pertaining to patients who needed less than 6 months of treatment and for patients still at high risk of recurrent VTE after 6 months of treatment.

However, the committee concluded that, despite these limitations, the AMPLIFY trials were the pivotal trials that informed the marketing authorization for apixaban. As such, they were sufficient to inform a recommendation for the whole population covered by the marketing authorization.

The committee also pointed out that there were no head-to-head trials evaluating the relative effectiveness of apixaban compared with rivaroxaban and dabigatran etexilate for treating and preventing VTE.

In addition, there were insufficient data to assess the effectiveness and safety of apixaban in patients with active cancer who had VTE, so it was not possible to make a specific recommendation for this group.

Cost-effectiveness

The cost of apixaban is £1.10 per tablet for either the 2.5 mg or 5 mg dose (excluding tax). The daily cost of apixaban is £2.20. (Costs may vary in different settings because of negotiated procurement discounts.)

Analyses suggested that the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of apixaban was less than £20,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained for either 6 months or life-long treatment. Therefore, NICE concluded that apixaban is a cost-effective use of NHS resources. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final guidance recommending the anticoagulant apixaban (Eliquis) as an option for treating and preventing venous thromboembolism (VTE) in adults.