User login

Bivalirudin in STEMI has low real-world stent thrombosis rate

PARIS – Antithrombotic therapy with bivalirudin for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction may have been unfairly tarnished as having a high stent thrombosis rate, according to a large, prospective, observational cohort study.

A new analysis from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) showed similarly low stent thrombosis rates within 30 days following primary PCI for STEMI regardless of whether the antithrombotic regimen involved bivalirudin (Angiomax), heparin only, or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, Dr. Per Grimfjard reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The SCAAR analysis captured all STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI in Sweden from 2007 through mid-2014. These data reflect real-world interventional practice in Sweden and elsewhere, where bivalirudin is typically administered in a prolonged infusion to protect against early stent thrombosis. In contrast, the randomized trials that linked bivalirudin to high stent thrombosis rates featured protocols in which the drug was stopped immediately after the procedure, noted Dr. Grimfjard, an interventional cardiologist at Uppsala (Sweden) University.

“These are nationwide Swedish numbers, and they are complete. We think the numbers are reassuring in that respect,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Andreas Baumbach said the Swedish data are consistent with his own experience in using bivalirudin in primary PCI for STEMI.

“The headline last year was that bivalirudin has a high stent thrombosis rate. It made the newspapers everywhere. But we never saw that, and we always thought that the difference might be in how we used the drug. There’s a new headline now, that this high stent thrombosis rate is not seen in clinical practice. The practice differs from the randomized trials, and the outcomes differ as well,” observed Dr. Baumbach, professor of interventional cardiology at the University of Bristol (England).

In SCAAR, the 30-day rate of definite, angiographically proven stent thrombosis was 0.84% in 16,860 bivalirudin-treated patients, 0.94% in 3,182 who got heparin only, and 0.83% in 11,216 glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor recipients. These numeric differences weren’t statistically significant.

All-cause mortality 1 year post-PCI was 9.1% in patients with no stent thrombosis, 16.1% in those who experienced stent thrombosis within 1 day post PCI, and 23.0% in those whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30. Dr. Grimfjard speculated that the explanation for the numerically higher 1-year all-cause mortality rate in patients whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30 as opposed to day 0-1 is probably that they were more likely to have left the hospital when stent thrombosis occurred. That would translate to a longer time to repeat revascularization, hence a larger MI, more heart failure and arrhythmia, and thus a higher long-term risk of death.

Several audience members commented that they weren’t sure what to make of the observational Swedish data because of the looming presence of several potential confounders. For one, clinical practice trends changed considerably during the 7-year time frame of the study, as evidenced by the fact that the use of drug-eluting stents was far more common in bivalirudin-treated patients than in the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor group. Also, Swedish cardiologists who put their STEMI patients on bivalirudin were more likely to utilize the more modern radial artery access in performing primary PCI; their practice may have differed from their colleagues’ in other, unrecorded ways as well, it was noted.

Dr. Grimfjard reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – Antithrombotic therapy with bivalirudin for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction may have been unfairly tarnished as having a high stent thrombosis rate, according to a large, prospective, observational cohort study.

A new analysis from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) showed similarly low stent thrombosis rates within 30 days following primary PCI for STEMI regardless of whether the antithrombotic regimen involved bivalirudin (Angiomax), heparin only, or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, Dr. Per Grimfjard reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The SCAAR analysis captured all STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI in Sweden from 2007 through mid-2014. These data reflect real-world interventional practice in Sweden and elsewhere, where bivalirudin is typically administered in a prolonged infusion to protect against early stent thrombosis. In contrast, the randomized trials that linked bivalirudin to high stent thrombosis rates featured protocols in which the drug was stopped immediately after the procedure, noted Dr. Grimfjard, an interventional cardiologist at Uppsala (Sweden) University.

“These are nationwide Swedish numbers, and they are complete. We think the numbers are reassuring in that respect,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Andreas Baumbach said the Swedish data are consistent with his own experience in using bivalirudin in primary PCI for STEMI.

“The headline last year was that bivalirudin has a high stent thrombosis rate. It made the newspapers everywhere. But we never saw that, and we always thought that the difference might be in how we used the drug. There’s a new headline now, that this high stent thrombosis rate is not seen in clinical practice. The practice differs from the randomized trials, and the outcomes differ as well,” observed Dr. Baumbach, professor of interventional cardiology at the University of Bristol (England).

In SCAAR, the 30-day rate of definite, angiographically proven stent thrombosis was 0.84% in 16,860 bivalirudin-treated patients, 0.94% in 3,182 who got heparin only, and 0.83% in 11,216 glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor recipients. These numeric differences weren’t statistically significant.

All-cause mortality 1 year post-PCI was 9.1% in patients with no stent thrombosis, 16.1% in those who experienced stent thrombosis within 1 day post PCI, and 23.0% in those whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30. Dr. Grimfjard speculated that the explanation for the numerically higher 1-year all-cause mortality rate in patients whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30 as opposed to day 0-1 is probably that they were more likely to have left the hospital when stent thrombosis occurred. That would translate to a longer time to repeat revascularization, hence a larger MI, more heart failure and arrhythmia, and thus a higher long-term risk of death.

Several audience members commented that they weren’t sure what to make of the observational Swedish data because of the looming presence of several potential confounders. For one, clinical practice trends changed considerably during the 7-year time frame of the study, as evidenced by the fact that the use of drug-eluting stents was far more common in bivalirudin-treated patients than in the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor group. Also, Swedish cardiologists who put their STEMI patients on bivalirudin were more likely to utilize the more modern radial artery access in performing primary PCI; their practice may have differed from their colleagues’ in other, unrecorded ways as well, it was noted.

Dr. Grimfjard reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – Antithrombotic therapy with bivalirudin for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction may have been unfairly tarnished as having a high stent thrombosis rate, according to a large, prospective, observational cohort study.

A new analysis from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) showed similarly low stent thrombosis rates within 30 days following primary PCI for STEMI regardless of whether the antithrombotic regimen involved bivalirudin (Angiomax), heparin only, or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, Dr. Per Grimfjard reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The SCAAR analysis captured all STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI in Sweden from 2007 through mid-2014. These data reflect real-world interventional practice in Sweden and elsewhere, where bivalirudin is typically administered in a prolonged infusion to protect against early stent thrombosis. In contrast, the randomized trials that linked bivalirudin to high stent thrombosis rates featured protocols in which the drug was stopped immediately after the procedure, noted Dr. Grimfjard, an interventional cardiologist at Uppsala (Sweden) University.

“These are nationwide Swedish numbers, and they are complete. We think the numbers are reassuring in that respect,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Andreas Baumbach said the Swedish data are consistent with his own experience in using bivalirudin in primary PCI for STEMI.

“The headline last year was that bivalirudin has a high stent thrombosis rate. It made the newspapers everywhere. But we never saw that, and we always thought that the difference might be in how we used the drug. There’s a new headline now, that this high stent thrombosis rate is not seen in clinical practice. The practice differs from the randomized trials, and the outcomes differ as well,” observed Dr. Baumbach, professor of interventional cardiology at the University of Bristol (England).

In SCAAR, the 30-day rate of definite, angiographically proven stent thrombosis was 0.84% in 16,860 bivalirudin-treated patients, 0.94% in 3,182 who got heparin only, and 0.83% in 11,216 glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor recipients. These numeric differences weren’t statistically significant.

All-cause mortality 1 year post-PCI was 9.1% in patients with no stent thrombosis, 16.1% in those who experienced stent thrombosis within 1 day post PCI, and 23.0% in those whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30. Dr. Grimfjard speculated that the explanation for the numerically higher 1-year all-cause mortality rate in patients whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30 as opposed to day 0-1 is probably that they were more likely to have left the hospital when stent thrombosis occurred. That would translate to a longer time to repeat revascularization, hence a larger MI, more heart failure and arrhythmia, and thus a higher long-term risk of death.

Several audience members commented that they weren’t sure what to make of the observational Swedish data because of the looming presence of several potential confounders. For one, clinical practice trends changed considerably during the 7-year time frame of the study, as evidenced by the fact that the use of drug-eluting stents was far more common in bivalirudin-treated patients than in the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor group. Also, Swedish cardiologists who put their STEMI patients on bivalirudin were more likely to utilize the more modern radial artery access in performing primary PCI; their practice may have differed from their colleagues’ in other, unrecorded ways as well, it was noted.

Dr. Grimfjard reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT EUROPCR 2015

Key clinical point: The 30-day incidence of stent thrombosis following primary PCI in a large, real-world STEMI population was reassuringly low regardless of the antithrombotic regimen.

Major finding: The stent thrombosis rate within 30 days after primary PCI for STEMI was 0.84% in patients who received bivalirudin for antithrombotic therapy, 0.94% with heparin only, and 0.83% with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor in this real-world nationwide Swedish registry.

Data source: A prospective observational cohort study which included all patients who underwent primary PCI for STEMI in Sweden during 2007-2014.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Doxorubicin, radiation doses predict heart risk in lymphoma survivors

Adult lymphoma survivors who were treated with autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation had a greater than sixfold increased risk of left ventricular systolic dysfunction compared with controls, according to a study published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Among 274 adult survivors of Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 16% had left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD): 11% had overt heart failure (HF) and 5% had asymptomatic LVSD, defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 50%.Heart symptoms were significantly associated with exposure to doxorubicin at a cumulative dose of 300 mg/m2 or more and with cardiac radiation therapy of more than 30 Gy. Recognizing these patient risk factors allows for more intensive follow-up with the goal of “identification and early treatment of asymptomatic LVSD [which] may prevent the development of HF,” wrote Dr. Klaus Murbraech of Oslo University Hospital and his colleagues (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 July 13 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8125]).

The investigators observed no association between lower-dose cardiac radiation therapy and LVSD. There was only a marginally significant association between the presence of two or more traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors and LVSD.

The cross-sectional multicenter cohort study is the first to assess the prevalence of LVSD, according to Dr. Murbraech and his colleagues. The study included adult survivors of Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma, median age 56 years, who underwent autologous stem-cell transplants in Norway from 1987 to 2008. The median observation time was 13 years (range, 4-34 years). The control group consisted of initially healthy patients in an echocardiographic follow-up study. Controls were matched to patients based on age, sex, systolic blood pressure, and body mass index.

The study was supported by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority and Extrastiftelsen. Dr. Murbraech reported having no disclosures.

Adult lymphoma survivors who were treated with autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation had a greater than sixfold increased risk of left ventricular systolic dysfunction compared with controls, according to a study published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Among 274 adult survivors of Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 16% had left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD): 11% had overt heart failure (HF) and 5% had asymptomatic LVSD, defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 50%.Heart symptoms were significantly associated with exposure to doxorubicin at a cumulative dose of 300 mg/m2 or more and with cardiac radiation therapy of more than 30 Gy. Recognizing these patient risk factors allows for more intensive follow-up with the goal of “identification and early treatment of asymptomatic LVSD [which] may prevent the development of HF,” wrote Dr. Klaus Murbraech of Oslo University Hospital and his colleagues (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 July 13 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8125]).

The investigators observed no association between lower-dose cardiac radiation therapy and LVSD. There was only a marginally significant association between the presence of two or more traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors and LVSD.

The cross-sectional multicenter cohort study is the first to assess the prevalence of LVSD, according to Dr. Murbraech and his colleagues. The study included adult survivors of Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma, median age 56 years, who underwent autologous stem-cell transplants in Norway from 1987 to 2008. The median observation time was 13 years (range, 4-34 years). The control group consisted of initially healthy patients in an echocardiographic follow-up study. Controls were matched to patients based on age, sex, systolic blood pressure, and body mass index.

The study was supported by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority and Extrastiftelsen. Dr. Murbraech reported having no disclosures.

Adult lymphoma survivors who were treated with autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation had a greater than sixfold increased risk of left ventricular systolic dysfunction compared with controls, according to a study published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Among 274 adult survivors of Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 16% had left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD): 11% had overt heart failure (HF) and 5% had asymptomatic LVSD, defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 50%.Heart symptoms were significantly associated with exposure to doxorubicin at a cumulative dose of 300 mg/m2 or more and with cardiac radiation therapy of more than 30 Gy. Recognizing these patient risk factors allows for more intensive follow-up with the goal of “identification and early treatment of asymptomatic LVSD [which] may prevent the development of HF,” wrote Dr. Klaus Murbraech of Oslo University Hospital and his colleagues (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 July 13 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8125]).

The investigators observed no association between lower-dose cardiac radiation therapy and LVSD. There was only a marginally significant association between the presence of two or more traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors and LVSD.

The cross-sectional multicenter cohort study is the first to assess the prevalence of LVSD, according to Dr. Murbraech and his colleagues. The study included adult survivors of Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma, median age 56 years, who underwent autologous stem-cell transplants in Norway from 1987 to 2008. The median observation time was 13 years (range, 4-34 years). The control group consisted of initially healthy patients in an echocardiographic follow-up study. Controls were matched to patients based on age, sex, systolic blood pressure, and body mass index.

The study was supported by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority and Extrastiftelsen. Dr. Murbraech reported having no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Lymphoma survivors treated with autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (auto-HSC) had a significantly higher risk of left ventricular systolic dysfunction than did controls.

Major finding: Treatment with at least 300 mg/m2 cumulative of doxorubicin and with over 30 Gy of cardiac radiation therapy were independent risk factors for LVSD.

Data source: A cross-sectional multicenter cohort study of 274 Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors.

Disclosures: Supported by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority and Extrastiftelsen. Dr. Murbraech reported having no disclosures.

JAK2 inhibitor could treat B-ALL

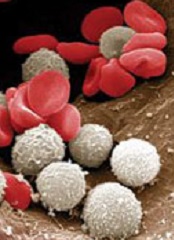

Photo courtesy of the

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

A type II JAK2 inhibitor has shown activity against B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) in preclinical experiments.

The inhibitor, known as CHZ868, works by binding JAK2 into a tightly clenched position, which prevents the protein from functioning.

Researchers tested CHZ868 in samples from patients with CRLF2-rearranged B-ALL, in mice with the disease, and in mice implanted with human B-ALL tissue.

“In each case, we saw good activity: leukemia cells died, JAK2 signaling was suspended, and survival rates increased,” said David Weinstock, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“When we combined CHZ868 with the steroid dexamethasone, the killing of leukemia cells was much more extensive, and the animals lived longer than they did with CHZ868 alone.”

Dr Weinstock and his colleagues reported these results in Cancer Cell. Some of the researchers involved in this work are employees of, or have received research funding from, Novartis.

The team found that CHZ868 inhibited JAK2 signaling in B-ALL, both in vitro and in vivo. CHZ868 could overcome persistent JAK2 signaling where type I JAK2 inhibitors (BSK805 and BVB808) could not.

However, the researchers also identified a mutation—JAK2 L884P—that conferred resistance to CHZ868 and another type II JAK2 inhibitor, BBT594.

Nevertheless, CHZ868 suppressed the growth of CRLF2-rearranged human B-ALL cells and improved survival in mice with human or murine B-ALL.

CHZ868 worked synergistically with dexamethasone to induce apoptosis in JAK2-dependent B-ALL. The combination also improved survival in mice with B-ALL, when compared to either dexamethasone or CHZ868 alone.

The researchers noted that, when given at 30 mg/kg/day, CHZ868 was tolerated in NSG mice for up to 25 days and in immunocompetent mice for up to 44 days. And the drug had “essentially no effects” on peripheral blood counts.

This result and the tolerability of dexamethasone make CHZ868 and dexamethasone a “particularly attractive” combination that should be investigated in clinical trials, the team said.

They also speculated that CHZ868 or other type II JAK2 inhibitors could prove effective against malignancies other than B-ALL.

“JAK2 abnormalities are found in some cases of triple-negative breast cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma,” Dr Weinstock noted. “The success of CHZ868 in B-ALL suggests that it, or a compound that works by a similar mechanism, may also be effective in these cancers.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of the

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

A type II JAK2 inhibitor has shown activity against B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) in preclinical experiments.

The inhibitor, known as CHZ868, works by binding JAK2 into a tightly clenched position, which prevents the protein from functioning.

Researchers tested CHZ868 in samples from patients with CRLF2-rearranged B-ALL, in mice with the disease, and in mice implanted with human B-ALL tissue.

“In each case, we saw good activity: leukemia cells died, JAK2 signaling was suspended, and survival rates increased,” said David Weinstock, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“When we combined CHZ868 with the steroid dexamethasone, the killing of leukemia cells was much more extensive, and the animals lived longer than they did with CHZ868 alone.”

Dr Weinstock and his colleagues reported these results in Cancer Cell. Some of the researchers involved in this work are employees of, or have received research funding from, Novartis.

The team found that CHZ868 inhibited JAK2 signaling in B-ALL, both in vitro and in vivo. CHZ868 could overcome persistent JAK2 signaling where type I JAK2 inhibitors (BSK805 and BVB808) could not.

However, the researchers also identified a mutation—JAK2 L884P—that conferred resistance to CHZ868 and another type II JAK2 inhibitor, BBT594.

Nevertheless, CHZ868 suppressed the growth of CRLF2-rearranged human B-ALL cells and improved survival in mice with human or murine B-ALL.

CHZ868 worked synergistically with dexamethasone to induce apoptosis in JAK2-dependent B-ALL. The combination also improved survival in mice with B-ALL, when compared to either dexamethasone or CHZ868 alone.

The researchers noted that, when given at 30 mg/kg/day, CHZ868 was tolerated in NSG mice for up to 25 days and in immunocompetent mice for up to 44 days. And the drug had “essentially no effects” on peripheral blood counts.

This result and the tolerability of dexamethasone make CHZ868 and dexamethasone a “particularly attractive” combination that should be investigated in clinical trials, the team said.

They also speculated that CHZ868 or other type II JAK2 inhibitors could prove effective against malignancies other than B-ALL.

“JAK2 abnormalities are found in some cases of triple-negative breast cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma,” Dr Weinstock noted. “The success of CHZ868 in B-ALL suggests that it, or a compound that works by a similar mechanism, may also be effective in these cancers.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of the

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

A type II JAK2 inhibitor has shown activity against B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) in preclinical experiments.

The inhibitor, known as CHZ868, works by binding JAK2 into a tightly clenched position, which prevents the protein from functioning.

Researchers tested CHZ868 in samples from patients with CRLF2-rearranged B-ALL, in mice with the disease, and in mice implanted with human B-ALL tissue.

“In each case, we saw good activity: leukemia cells died, JAK2 signaling was suspended, and survival rates increased,” said David Weinstock, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“When we combined CHZ868 with the steroid dexamethasone, the killing of leukemia cells was much more extensive, and the animals lived longer than they did with CHZ868 alone.”

Dr Weinstock and his colleagues reported these results in Cancer Cell. Some of the researchers involved in this work are employees of, or have received research funding from, Novartis.

The team found that CHZ868 inhibited JAK2 signaling in B-ALL, both in vitro and in vivo. CHZ868 could overcome persistent JAK2 signaling where type I JAK2 inhibitors (BSK805 and BVB808) could not.

However, the researchers also identified a mutation—JAK2 L884P—that conferred resistance to CHZ868 and another type II JAK2 inhibitor, BBT594.

Nevertheless, CHZ868 suppressed the growth of CRLF2-rearranged human B-ALL cells and improved survival in mice with human or murine B-ALL.

CHZ868 worked synergistically with dexamethasone to induce apoptosis in JAK2-dependent B-ALL. The combination also improved survival in mice with B-ALL, when compared to either dexamethasone or CHZ868 alone.

The researchers noted that, when given at 30 mg/kg/day, CHZ868 was tolerated in NSG mice for up to 25 days and in immunocompetent mice for up to 44 days. And the drug had “essentially no effects” on peripheral blood counts.

This result and the tolerability of dexamethasone make CHZ868 and dexamethasone a “particularly attractive” combination that should be investigated in clinical trials, the team said.

They also speculated that CHZ868 or other type II JAK2 inhibitors could prove effective against malignancies other than B-ALL.

“JAK2 abnormalities are found in some cases of triple-negative breast cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma,” Dr Weinstock noted. “The success of CHZ868 in B-ALL suggests that it, or a compound that works by a similar mechanism, may also be effective in these cancers.” ![]()

Length of cell-cycle phase affects HSC function

in the bone marrow

Shortening the G1 phase of the cell cycle can improve the production and function of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), according to research published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

When investigators shortened the G1 phase in human HSCs, they found the cells were better able to resist differentiation in vitro and exhibited enhanced engraftment in vivo.

However, these benefits only occurred when the team shortened the early phase of G1, not the late phase.

Claudia Waskow, PhD, of Technische Universitaet Dresden in Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research to determine whether the function of human HSCs is controlled by the kinetics of cell-cycle progression.

The investigators knew that the body’s pool of HSCs is maintained through self-renewing divisions tightly regulated by enzymatically active cyclin (CCN)/cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) complexes.

So they enforced expression of functional CCND1–CDK4 complexes, which are important for progression through the early G1 phase of the cell cycle, and CCNE1–CDK2 complexes, which are key in the transition from the G1 phase to the S phase.

Overexpression of CCND1–CDK4 complexes (also referred to as elevated 4D) promoted the transit from G0 to G1 and successfully shortened the G1 phase. However, the total length of the cell cycle did not change much, as the G2 or M phase was prolonged slightly.

The investigators also found that elevated 4D levels protected HSCs from differentiation-inducing signals in vitro and provided a “competitive advantage” in vivo.

When they transplanted HSCs with elevated 4D into mice, the team observed improved donor-leukocyte engraftment but no increase in the HSC pool. They said the improvement in engraftment was based on an elevated output of myeloid cells.

In contrast to elevated 4D, overexpression of CCNE1–CDK2 (also referred to as elevated 2E) conferred detrimental effects. Elevated 2E did accelerate cell-cycle progression, but it led to the loss of functional HSCs and poor engraftment.

The investigators said a large proportion of cells with elevated 2E contained fragmented DNA and underwent apoptosis after transduction.

In addition, many HSCs with elevated 2E exited G0 and shifted to the S–G2–M phases of the cell cycle. The G1 phase was significantly shortened, and the time HSCs spent in each cycle was reduced.

Dr Waskow and her colleagues said these results suggest transit velocity through the early and late G1 phase is an important regulator of HSC function and therefore makes an essential contribution to the maintenance of hematopoiesis.

Furthermore, alterations of G1 transition kinetics may be the basis for functional defects observed in HSCs from old mice or elderly humans. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Shortening the G1 phase of the cell cycle can improve the production and function of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), according to research published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

When investigators shortened the G1 phase in human HSCs, they found the cells were better able to resist differentiation in vitro and exhibited enhanced engraftment in vivo.

However, these benefits only occurred when the team shortened the early phase of G1, not the late phase.

Claudia Waskow, PhD, of Technische Universitaet Dresden in Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research to determine whether the function of human HSCs is controlled by the kinetics of cell-cycle progression.

The investigators knew that the body’s pool of HSCs is maintained through self-renewing divisions tightly regulated by enzymatically active cyclin (CCN)/cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) complexes.

So they enforced expression of functional CCND1–CDK4 complexes, which are important for progression through the early G1 phase of the cell cycle, and CCNE1–CDK2 complexes, which are key in the transition from the G1 phase to the S phase.

Overexpression of CCND1–CDK4 complexes (also referred to as elevated 4D) promoted the transit from G0 to G1 and successfully shortened the G1 phase. However, the total length of the cell cycle did not change much, as the G2 or M phase was prolonged slightly.

The investigators also found that elevated 4D levels protected HSCs from differentiation-inducing signals in vitro and provided a “competitive advantage” in vivo.

When they transplanted HSCs with elevated 4D into mice, the team observed improved donor-leukocyte engraftment but no increase in the HSC pool. They said the improvement in engraftment was based on an elevated output of myeloid cells.

In contrast to elevated 4D, overexpression of CCNE1–CDK2 (also referred to as elevated 2E) conferred detrimental effects. Elevated 2E did accelerate cell-cycle progression, but it led to the loss of functional HSCs and poor engraftment.

The investigators said a large proportion of cells with elevated 2E contained fragmented DNA and underwent apoptosis after transduction.

In addition, many HSCs with elevated 2E exited G0 and shifted to the S–G2–M phases of the cell cycle. The G1 phase was significantly shortened, and the time HSCs spent in each cycle was reduced.

Dr Waskow and her colleagues said these results suggest transit velocity through the early and late G1 phase is an important regulator of HSC function and therefore makes an essential contribution to the maintenance of hematopoiesis.

Furthermore, alterations of G1 transition kinetics may be the basis for functional defects observed in HSCs from old mice or elderly humans. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Shortening the G1 phase of the cell cycle can improve the production and function of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), according to research published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

When investigators shortened the G1 phase in human HSCs, they found the cells were better able to resist differentiation in vitro and exhibited enhanced engraftment in vivo.

However, these benefits only occurred when the team shortened the early phase of G1, not the late phase.

Claudia Waskow, PhD, of Technische Universitaet Dresden in Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research to determine whether the function of human HSCs is controlled by the kinetics of cell-cycle progression.

The investigators knew that the body’s pool of HSCs is maintained through self-renewing divisions tightly regulated by enzymatically active cyclin (CCN)/cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) complexes.

So they enforced expression of functional CCND1–CDK4 complexes, which are important for progression through the early G1 phase of the cell cycle, and CCNE1–CDK2 complexes, which are key in the transition from the G1 phase to the S phase.

Overexpression of CCND1–CDK4 complexes (also referred to as elevated 4D) promoted the transit from G0 to G1 and successfully shortened the G1 phase. However, the total length of the cell cycle did not change much, as the G2 or M phase was prolonged slightly.

The investigators also found that elevated 4D levels protected HSCs from differentiation-inducing signals in vitro and provided a “competitive advantage” in vivo.

When they transplanted HSCs with elevated 4D into mice, the team observed improved donor-leukocyte engraftment but no increase in the HSC pool. They said the improvement in engraftment was based on an elevated output of myeloid cells.

In contrast to elevated 4D, overexpression of CCNE1–CDK2 (also referred to as elevated 2E) conferred detrimental effects. Elevated 2E did accelerate cell-cycle progression, but it led to the loss of functional HSCs and poor engraftment.

The investigators said a large proportion of cells with elevated 2E contained fragmented DNA and underwent apoptosis after transduction.

In addition, many HSCs with elevated 2E exited G0 and shifted to the S–G2–M phases of the cell cycle. The G1 phase was significantly shortened, and the time HSCs spent in each cycle was reduced.

Dr Waskow and her colleagues said these results suggest transit velocity through the early and late G1 phase is an important regulator of HSC function and therefore makes an essential contribution to the maintenance of hematopoiesis.

Furthermore, alterations of G1 transition kinetics may be the basis for functional defects observed in HSCs from old mice or elderly humans. ![]()

ASCO updates guideline on CSFs

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has updated its clinical practice guideline on hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors (CSFs).

The guideline includes recommendations on the use of CSFs in the context of lymphoma, solid tumor malignancies, pediatric leukemia, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

There are no recommendations pertaining to adults with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes.

ASCO’s previous guideline on CSFs was issued in 2006. For the update, an ASCO expert panel conducted a formal systematic review of relevant articles from the medical literature published from October 2005 through September 2014.

Key recommendations from the resulting guideline are as follows.

Pegfilgrastim, filgrastim, tbo-filgrastim, and filgrastim-sndz (and other biosimilars, as they become available) can be used for the prevention of treatment-related febrile neutropenia.

For patients with lymphomas or solid tumors, primary prophylaxis with a CSF should be given during all cycles of chemotherapy in patients who have an approximately 20% or higher risk for febrile neutropenia on the basis of patient-, disease-, and treatment-related factors.

However, clinicians should also consider using chemotherapy regimens that do not require CSF administration but are as effective as regimens that do require a CSF.

Patients with lymphomas or solid tumors should receive secondary febrile neutropenia prophylaxis with a CSF if they experienced a neutropenic complication from a previous cycle of chemotherapy (for which they did not receive primary prophylaxis) when a reduced dose or treatment delay may compromise disease-free survival, overall survival, or treatment outcome.

However, the guideline also says that, in many clinical situations, dose reductions or delays may be a reasonable alternative.

CSFs should not be routinely used for patients with neutropenia who are afebrile or as adjunctive treatment with antibiotic therapy for patients with fever and neutropenia.

Dose-dense regimens with CSF support should only be used within an appropriately designed clinical trial or if use of the regimen is supported by convincing efficacy data. The guideline says that, for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, data on the value of dose-dense regimens with CSF support are limited and conflicting.

In the context of transplant, CSFs may be used alone, after chemotherapy, or in combination with plerixafor to mobilize peripheral blood stem cells. To reduce the duration of severe neutropenia, CSFs should be administered after autologous stem cell transplant and may be administered after allogeneic stem cell transplant.

CSFs should be avoided in patients receiving concomitant chemotherapy and radiation, particularly involving the mediastinum. CSFs may be considered in patients receiving radiation alone if the clinician expects prolonged treatment delays due to neutropenia.

Patients who are exposed to lethal doses of total-body radiotherapy, but not doses high enough to lead to certain death resulting from injury to other organs, should promptly receive CSFs or pegylated granulocyte CSFs.

Clinicians should consider prophylactic CSF for patients with diffuse aggressive lymphoma who are 65 or older and are receiving curative chemotherapy (R-CHOP), particularly if they have comorbidities.

The guideline also says the use of CSFs in pediatric patients will almost always be guided by clinical protocols. But CSFs should not be used in pediatric patients with nonrelapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia or nonrelapsed acute myeloid leukemia who do not have an infection.

For more details, see the complete guideline. ASCO said it encourages feedback on its guidelines from oncologists, practitioners, and patients through the ASCO Guidelines Wiki. ![]()

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has updated its clinical practice guideline on hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors (CSFs).

The guideline includes recommendations on the use of CSFs in the context of lymphoma, solid tumor malignancies, pediatric leukemia, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

There are no recommendations pertaining to adults with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes.

ASCO’s previous guideline on CSFs was issued in 2006. For the update, an ASCO expert panel conducted a formal systematic review of relevant articles from the medical literature published from October 2005 through September 2014.

Key recommendations from the resulting guideline are as follows.

Pegfilgrastim, filgrastim, tbo-filgrastim, and filgrastim-sndz (and other biosimilars, as they become available) can be used for the prevention of treatment-related febrile neutropenia.

For patients with lymphomas or solid tumors, primary prophylaxis with a CSF should be given during all cycles of chemotherapy in patients who have an approximately 20% or higher risk for febrile neutropenia on the basis of patient-, disease-, and treatment-related factors.

However, clinicians should also consider using chemotherapy regimens that do not require CSF administration but are as effective as regimens that do require a CSF.

Patients with lymphomas or solid tumors should receive secondary febrile neutropenia prophylaxis with a CSF if they experienced a neutropenic complication from a previous cycle of chemotherapy (for which they did not receive primary prophylaxis) when a reduced dose or treatment delay may compromise disease-free survival, overall survival, or treatment outcome.

However, the guideline also says that, in many clinical situations, dose reductions or delays may be a reasonable alternative.

CSFs should not be routinely used for patients with neutropenia who are afebrile or as adjunctive treatment with antibiotic therapy for patients with fever and neutropenia.

Dose-dense regimens with CSF support should only be used within an appropriately designed clinical trial or if use of the regimen is supported by convincing efficacy data. The guideline says that, for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, data on the value of dose-dense regimens with CSF support are limited and conflicting.

In the context of transplant, CSFs may be used alone, after chemotherapy, or in combination with plerixafor to mobilize peripheral blood stem cells. To reduce the duration of severe neutropenia, CSFs should be administered after autologous stem cell transplant and may be administered after allogeneic stem cell transplant.

CSFs should be avoided in patients receiving concomitant chemotherapy and radiation, particularly involving the mediastinum. CSFs may be considered in patients receiving radiation alone if the clinician expects prolonged treatment delays due to neutropenia.

Patients who are exposed to lethal doses of total-body radiotherapy, but not doses high enough to lead to certain death resulting from injury to other organs, should promptly receive CSFs or pegylated granulocyte CSFs.

Clinicians should consider prophylactic CSF for patients with diffuse aggressive lymphoma who are 65 or older and are receiving curative chemotherapy (R-CHOP), particularly if they have comorbidities.

The guideline also says the use of CSFs in pediatric patients will almost always be guided by clinical protocols. But CSFs should not be used in pediatric patients with nonrelapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia or nonrelapsed acute myeloid leukemia who do not have an infection.

For more details, see the complete guideline. ASCO said it encourages feedback on its guidelines from oncologists, practitioners, and patients through the ASCO Guidelines Wiki. ![]()

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has updated its clinical practice guideline on hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors (CSFs).

The guideline includes recommendations on the use of CSFs in the context of lymphoma, solid tumor malignancies, pediatric leukemia, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

There are no recommendations pertaining to adults with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes.

ASCO’s previous guideline on CSFs was issued in 2006. For the update, an ASCO expert panel conducted a formal systematic review of relevant articles from the medical literature published from October 2005 through September 2014.

Key recommendations from the resulting guideline are as follows.

Pegfilgrastim, filgrastim, tbo-filgrastim, and filgrastim-sndz (and other biosimilars, as they become available) can be used for the prevention of treatment-related febrile neutropenia.

For patients with lymphomas or solid tumors, primary prophylaxis with a CSF should be given during all cycles of chemotherapy in patients who have an approximately 20% or higher risk for febrile neutropenia on the basis of patient-, disease-, and treatment-related factors.

However, clinicians should also consider using chemotherapy regimens that do not require CSF administration but are as effective as regimens that do require a CSF.

Patients with lymphomas or solid tumors should receive secondary febrile neutropenia prophylaxis with a CSF if they experienced a neutropenic complication from a previous cycle of chemotherapy (for which they did not receive primary prophylaxis) when a reduced dose or treatment delay may compromise disease-free survival, overall survival, or treatment outcome.

However, the guideline also says that, in many clinical situations, dose reductions or delays may be a reasonable alternative.

CSFs should not be routinely used for patients with neutropenia who are afebrile or as adjunctive treatment with antibiotic therapy for patients with fever and neutropenia.

Dose-dense regimens with CSF support should only be used within an appropriately designed clinical trial or if use of the regimen is supported by convincing efficacy data. The guideline says that, for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, data on the value of dose-dense regimens with CSF support are limited and conflicting.

In the context of transplant, CSFs may be used alone, after chemotherapy, or in combination with plerixafor to mobilize peripheral blood stem cells. To reduce the duration of severe neutropenia, CSFs should be administered after autologous stem cell transplant and may be administered after allogeneic stem cell transplant.

CSFs should be avoided in patients receiving concomitant chemotherapy and radiation, particularly involving the mediastinum. CSFs may be considered in patients receiving radiation alone if the clinician expects prolonged treatment delays due to neutropenia.

Patients who are exposed to lethal doses of total-body radiotherapy, but not doses high enough to lead to certain death resulting from injury to other organs, should promptly receive CSFs or pegylated granulocyte CSFs.

Clinicians should consider prophylactic CSF for patients with diffuse aggressive lymphoma who are 65 or older and are receiving curative chemotherapy (R-CHOP), particularly if they have comorbidities.

The guideline also says the use of CSFs in pediatric patients will almost always be guided by clinical protocols. But CSFs should not be used in pediatric patients with nonrelapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia or nonrelapsed acute myeloid leukemia who do not have an infection.

For more details, see the complete guideline. ASCO said it encourages feedback on its guidelines from oncologists, practitioners, and patients through the ASCO Guidelines Wiki. ![]()

Restrictive transfusion may be safe for AUGIB

Photo by Elise Amendola

Results of a pilot study suggest a restrictive transfusion strategy may be safe for patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB), but investigators say more research is needed.

In this study, known as TRIGGER, use of a restrictive transfusion strategy led to a 13% reduction in red blood cell (RBC) transfusions compared to the liberal strategy, but this difference was not statistically significant.

Likewise, there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes whether AUGIB patients received transfusions according to the restrictive strategy or the liberal one.

These results suggest a need for a large, randomized trial, according to investigators.

“If restrictive practice is proven to be safe in a large study, it could potentially safely reduce the use of red blood cell transfusions and produce cost savings . . . ,” said Vipul Jairath, MBChB, DPhil, of Oxford University Hospitals in the UK.

He and his colleagues conducted the TRIGGER trial and reported the results in The Lancet.

The study included 6 hospitals that had more than 20 AUGIB admissions monthly, more than 400 adult beds, 24-hour endoscopy, and onsite intensive care and surgery. Patients were eligible if they presented with new AUGIB (defined by hematemesis or melena) and were 18 or older. The only exclusion criterion was exsanguinating hemorrhage.

The investigators enrolled 936 patients—403 on the restrictive transfusion arm and 533 on the liberal arm. Patients in the restrictive arm were eligible to receive RBCs when their hemoglobin concentration fell below 80 g/L, with a post-transfusion target of 81-100 g/L.

Patients in the liberal arm were eligible for transfusion when their hemoglobin concentration fell below 100 g/L, with a post-transfusion target of 101-120 g/L. These thresholds were informed by UK transfusion practices.

Protocol adherence was 96% in the restrictive arm and 83% in the liberal arm. The mean last recorded hemoglobin concentration was 116 g/L for the restrictive arm and 118 g/L for the liberal arm.

The investigators noted that there was a 13% absolute reduction in the proportion of patients transfused in the restrictive arm, a reduction in the amount of RBCs transfused between the arms, and a separation in hemoglobin concentration between the arms, but none of these differences were significant.

In addition, there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes between the arms, although the trial was not powered to assess these outcomes.

All-cause mortality at day 28 was 7% in the liberal transfusion arm and 5% in the restrictive arm. The rate of serious adverse events at day 28 was 22% and 18%, respectively.

At hospital discharge, further bleeding had occurred in 6% of patients in the liberal arm and 4% in the restrictive arm. At day 28, further bleeding had occurred in 9% and 5%, respectively.

At discharge, thromboembolic or ischemic events had occurred in 5% of patients in the liberal arm and 3% in the restrictive arm. At day 28, these events had occurred in 7% and 4%, respectively.

At discharge, acute transfusion reactions had occurred in 2% of patients in the liberal arm and 1% in the restrictive arm, and infections had occurred in 24% and 26%, respectively.

By discharge, 38% of patients in the liberal arm and 32% in the restrictive arm had required some therapeutic intervention. Surgical or radiological intervention was required in 3% and 4%, respectively.

Considering these results, the investigators said the TRIGGER trial has paved the way for a phase 3 trial that could provide evidence to inform transfusion guidelines for patients with AUGIB. ![]()

Photo by Elise Amendola

Results of a pilot study suggest a restrictive transfusion strategy may be safe for patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB), but investigators say more research is needed.

In this study, known as TRIGGER, use of a restrictive transfusion strategy led to a 13% reduction in red blood cell (RBC) transfusions compared to the liberal strategy, but this difference was not statistically significant.

Likewise, there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes whether AUGIB patients received transfusions according to the restrictive strategy or the liberal one.

These results suggest a need for a large, randomized trial, according to investigators.

“If restrictive practice is proven to be safe in a large study, it could potentially safely reduce the use of red blood cell transfusions and produce cost savings . . . ,” said Vipul Jairath, MBChB, DPhil, of Oxford University Hospitals in the UK.

He and his colleagues conducted the TRIGGER trial and reported the results in The Lancet.

The study included 6 hospitals that had more than 20 AUGIB admissions monthly, more than 400 adult beds, 24-hour endoscopy, and onsite intensive care and surgery. Patients were eligible if they presented with new AUGIB (defined by hematemesis or melena) and were 18 or older. The only exclusion criterion was exsanguinating hemorrhage.

The investigators enrolled 936 patients—403 on the restrictive transfusion arm and 533 on the liberal arm. Patients in the restrictive arm were eligible to receive RBCs when their hemoglobin concentration fell below 80 g/L, with a post-transfusion target of 81-100 g/L.

Patients in the liberal arm were eligible for transfusion when their hemoglobin concentration fell below 100 g/L, with a post-transfusion target of 101-120 g/L. These thresholds were informed by UK transfusion practices.

Protocol adherence was 96% in the restrictive arm and 83% in the liberal arm. The mean last recorded hemoglobin concentration was 116 g/L for the restrictive arm and 118 g/L for the liberal arm.

The investigators noted that there was a 13% absolute reduction in the proportion of patients transfused in the restrictive arm, a reduction in the amount of RBCs transfused between the arms, and a separation in hemoglobin concentration between the arms, but none of these differences were significant.

In addition, there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes between the arms, although the trial was not powered to assess these outcomes.

All-cause mortality at day 28 was 7% in the liberal transfusion arm and 5% in the restrictive arm. The rate of serious adverse events at day 28 was 22% and 18%, respectively.

At hospital discharge, further bleeding had occurred in 6% of patients in the liberal arm and 4% in the restrictive arm. At day 28, further bleeding had occurred in 9% and 5%, respectively.

At discharge, thromboembolic or ischemic events had occurred in 5% of patients in the liberal arm and 3% in the restrictive arm. At day 28, these events had occurred in 7% and 4%, respectively.

At discharge, acute transfusion reactions had occurred in 2% of patients in the liberal arm and 1% in the restrictive arm, and infections had occurred in 24% and 26%, respectively.

By discharge, 38% of patients in the liberal arm and 32% in the restrictive arm had required some therapeutic intervention. Surgical or radiological intervention was required in 3% and 4%, respectively.

Considering these results, the investigators said the TRIGGER trial has paved the way for a phase 3 trial that could provide evidence to inform transfusion guidelines for patients with AUGIB. ![]()

Photo by Elise Amendola

Results of a pilot study suggest a restrictive transfusion strategy may be safe for patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB), but investigators say more research is needed.

In this study, known as TRIGGER, use of a restrictive transfusion strategy led to a 13% reduction in red blood cell (RBC) transfusions compared to the liberal strategy, but this difference was not statistically significant.

Likewise, there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes whether AUGIB patients received transfusions according to the restrictive strategy or the liberal one.

These results suggest a need for a large, randomized trial, according to investigators.

“If restrictive practice is proven to be safe in a large study, it could potentially safely reduce the use of red blood cell transfusions and produce cost savings . . . ,” said Vipul Jairath, MBChB, DPhil, of Oxford University Hospitals in the UK.

He and his colleagues conducted the TRIGGER trial and reported the results in The Lancet.

The study included 6 hospitals that had more than 20 AUGIB admissions monthly, more than 400 adult beds, 24-hour endoscopy, and onsite intensive care and surgery. Patients were eligible if they presented with new AUGIB (defined by hematemesis or melena) and were 18 or older. The only exclusion criterion was exsanguinating hemorrhage.

The investigators enrolled 936 patients—403 on the restrictive transfusion arm and 533 on the liberal arm. Patients in the restrictive arm were eligible to receive RBCs when their hemoglobin concentration fell below 80 g/L, with a post-transfusion target of 81-100 g/L.

Patients in the liberal arm were eligible for transfusion when their hemoglobin concentration fell below 100 g/L, with a post-transfusion target of 101-120 g/L. These thresholds were informed by UK transfusion practices.

Protocol adherence was 96% in the restrictive arm and 83% in the liberal arm. The mean last recorded hemoglobin concentration was 116 g/L for the restrictive arm and 118 g/L for the liberal arm.

The investigators noted that there was a 13% absolute reduction in the proportion of patients transfused in the restrictive arm, a reduction in the amount of RBCs transfused between the arms, and a separation in hemoglobin concentration between the arms, but none of these differences were significant.

In addition, there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes between the arms, although the trial was not powered to assess these outcomes.

All-cause mortality at day 28 was 7% in the liberal transfusion arm and 5% in the restrictive arm. The rate of serious adverse events at day 28 was 22% and 18%, respectively.

At hospital discharge, further bleeding had occurred in 6% of patients in the liberal arm and 4% in the restrictive arm. At day 28, further bleeding had occurred in 9% and 5%, respectively.

At discharge, thromboembolic or ischemic events had occurred in 5% of patients in the liberal arm and 3% in the restrictive arm. At day 28, these events had occurred in 7% and 4%, respectively.

At discharge, acute transfusion reactions had occurred in 2% of patients in the liberal arm and 1% in the restrictive arm, and infections had occurred in 24% and 26%, respectively.

By discharge, 38% of patients in the liberal arm and 32% in the restrictive arm had required some therapeutic intervention. Surgical or radiological intervention was required in 3% and 4%, respectively.

Considering these results, the investigators said the TRIGGER trial has paved the way for a phase 3 trial that could provide evidence to inform transfusion guidelines for patients with AUGIB. ![]()

Taking the Detour

A 60‐year‐old woman presented to a community hospital's emergency department with 4 days of right‐sided abdominal pain and multiple episodes of black stools. She reported nausea without vomiting. She denied light‐headedness, chest pain, or shortness of breath. She also denied difficulty in swallowing, weight loss, jaundice, or other bleeding.

The first priority when assessing a patient with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is to ensure hemodynamic stability. Next, it is important to carefully characterize the stools to help narrow the differential diagnosis. As blood is a cathartic, frequent, loose, and black stools suggest vigorous bleeding. It is essential to establish that the stools are actually black, as some patients will mistake dark brown stools for melena. Using a visual aid like a black pen or shoes as a point of reference can help the patient differentiate between dark stool and melena. It is also important to obtain a thorough medication history because iron supplements or bismuth‐containing remedies can turn stool black. The use of any antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants should also be noted. The right‐sided abdominal pain should be characterized by establishing the frequency, severity, and association with eating, movement, and position. For this patient's presentation, increased pain with eating would rapidly heighten concern for mesenteric ischemia.

The patient reported having 1 to 2 semiformed, tarry, black bowel movements per day. The night prior to admission she had passed some bright red blood along with the melena. The abdominal pain had increased gradually over 4 days, was dull, constant, did not radiate, and there were no evident aggravating or relieving factors. She rated the pain as 4 out of 10 in intensity, worst in her right upper quadrant.

Her past medical history was notable for recurrent deep venous thromboses and pulmonary emboli that had occurred even while on oral anticoagulation. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters had twice been placed many years prior; anticoagulation had been subsequently discontinued. Additionally, she was known to have chronic superior vena cava (SVC) occlusion, presumably related to hypercoagulability. Previous evaluation had identified only hyperhomocysteinemia as a risk factor for recurrent thromboses. Other medical problems included hemorrhoids, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and asthma. Her only surgical history was an abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy many years ago for nonmalignant disease. Home medications were omeprazole, ranitidine, albuterol, and fluticasone‐salmeterol. She denied using nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, aspirin, or any dietary supplements. She denied smoking, alcohol, or recreational drug use.

Because melena is confirmed, an upper GI tract bleeding source is most likely. The more recent appearance of bright red blood is concerning for acceleration of bleeding, or may point to a distal small bowel or right colonic source. Given the history of thromboembolic disease and likely underlying hypercoagulability, vascular occlusion is a leading possibility. Thus, mesenteric arterial insufficiency or mesenteric venous thrombosis should be considered, even though the patient does not report the characteristic postprandial exacerbation of pain. Ischemic colitis due to arterial insufficiency typically presents with severe, acute pain, with or without hematochezia. This syndrome is typically manifested in vascular watershed areas such as the splenic flexure, but can also affect the right colon. Mesenteric venous thrombosis is a rare condition that most often occurs in patients with hypercoagulability. Patients present with variable degrees of abdominal pain and often with GI bleeding. Finally, portal venous thrombosis may be seen alongside thromboses of other mesenteric veins or may occur independently. Portal hypertension due to portal vein thrombosis can result in esophageal and/or gastric varices. Although variceal bleeding classically presents with dramatic hematemesis, the absence of hematemesis does not rule out a variceal bleed in this patient.

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 37.1C with a pulse of 90 beats per minute and blood pressure of 161/97 mm Hg. Orthostatics were not performed. No blood was seen on nasal and oropharyngeal exam. Respiratory and cardiovascular exams were normal. On abdominal exam, there was tenderness to palpation of the right upper quadrant without rebound or guarding. The spleen and the liver were not palpable. There was a lower midline incisional scar. Rectal exam revealed nonbleeding hemorrhoids and heme‐positive stool without gross blood. Bilateral lower extremities had trace pitting edema, hyperpigmentation, and superficial venous varicosities. On skin exam, there were distended subcutaneous veins radiating outward from around the umbilicus as well as prominent subcutaneous venous collaterals over the chest and lateral abdomen.

The collateral veins over the chest and lateral abdomen are consistent with central venous obstruction from the patient's known SVC thrombus. However, the presence of paraumbilical venous collaterals (caput medusa) is highly suggestive of portal hypertension. This evidence, in addition to the known central venous occlusion and history of thromboembolic disease, raises the suspicion for mesenteric thrombosis as a cause of her bleeding and pain. The first diagnostic procedure should be an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to identify and potentially treat the source of bleeding, whether it is portal hypertension related (portal gastropathy, variceal bleed) or from a more common cause (peptic ulcer disease, stress gastritis). If the EGD is not diagnostic, the next step should be to obtain computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast. In many patients with GI bleed, a colonoscopy would typically be performed as the next diagnostic study after EGD. However, in this patient, a CT scan is likely to be of higher yield because it could help assess the mesenteric and portal vessels for patency and characterize the appearance of the small intestine and colon. Depending on the findings of the CT, additional dedicated vascular diagnostics might be needed.

Hemoglobin was 8.5 g/dL (12.4 g/dL 6 weeks prior) with a normal mean corpuscular volume and red cell distribution. The white cell count was normal, and the platelet count was 142,000/mm3. The blood urea nitrogen was 27 mg/dL, with a creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL. Routine chemistries, liver enzymes, bilirubin, and coagulation parameters were normal. Ferritin was 15 ng/mL (normal: 15200 ng/mL).

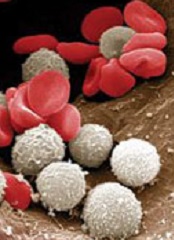

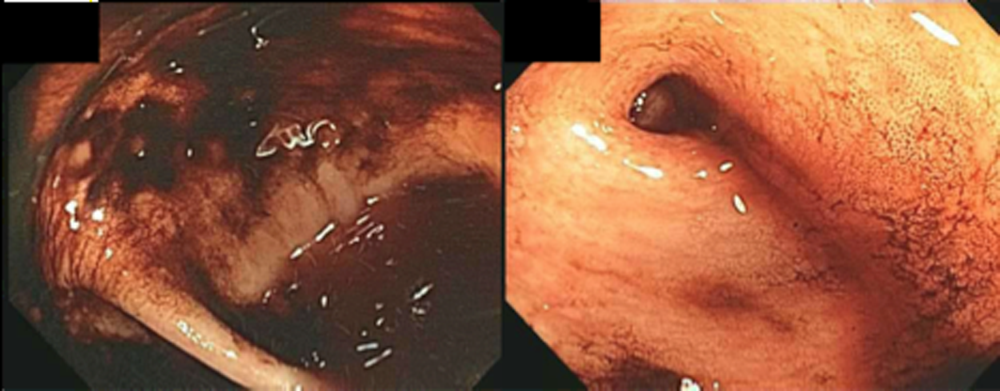

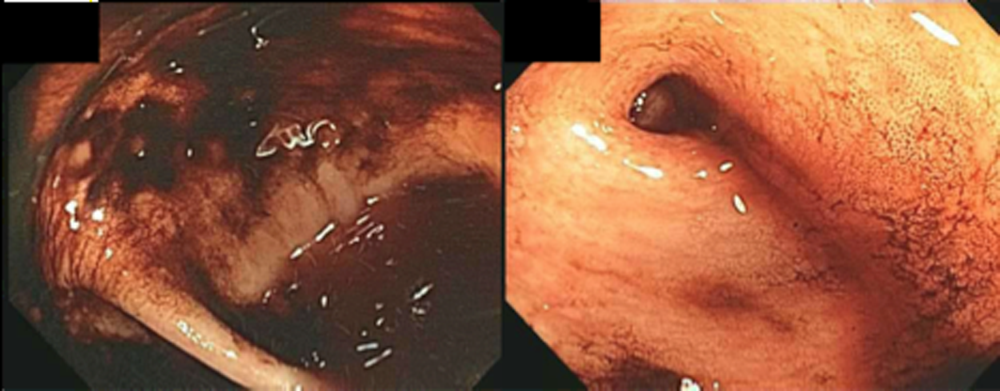

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. An EGD revealed a hiatal hernia and grade II nonbleeding esophageal varices with normal=appearing stomach and duodenum. The varices did not have stigmata of a recent bleed and were not ligated. The patient continued to bleed and received 2 U of packed red blood cells (RBCs), as her hemoglobin had decreased to 7.3 g/dL. On hospital day 3, a colonoscopy was done that showed blood clots in the ascending colon but was otherwise normal. The patient had ongoing abdominal pain, melena, and hematochezia, and continued to require blood transfusions every other day.

Esophageal varices were confirmed on EGD. However, no high‐risk stigmata were seen. Findings that suggest either recent bleeding or are risk factors for subsequent bleeding include large size of the varices, nipple sign referring to a protruding vessel from an underlying varix, or red wale sign, referring to a longitudinal red streak on a varix. The lack of evidence for an esophageal, gastric, or duodenal bleeding source correlates with lack of clinical signs of upper GI tract hemorrhage such as hematemesis or coffee ground emesis. Because the colonoscopy also did not identify a bleeding source, the bleeding remains unexplained. The absence of significant abnormalities in liver function or liver inflammation labs suggests that the patient does not have advanced cirrhosis and supports the suspicion of a vascular cause of the portal hypertension. At this point, it would be most useful to obtain a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

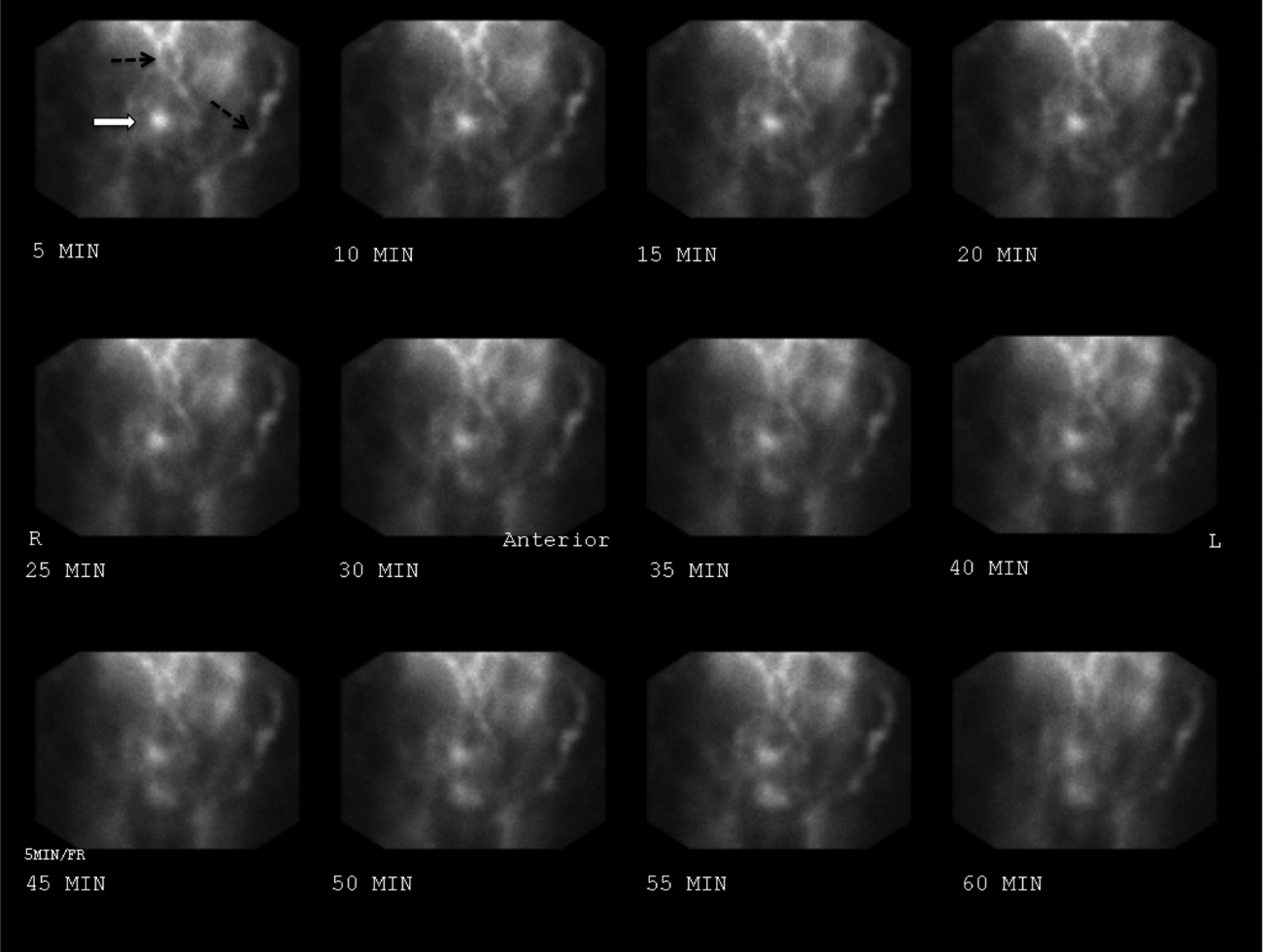

The patient continued to bleed, requiring a total of 7 U of packed RBCs over 7 days. On hospital day 4, a repeat EGD showed nonbleeding varices with a red wale sign that were banded. Despite this, the hemoglobin continued to drop. A technetium‐tagged RBC study showed a small area of subumbilical activity, which appeared to indicate transverse colonic or small bowel bleeding (Figure 1). A subsequent mesenteric angiogram failed to show active bleeding.

A red wale sign confers a higher risk of bleeding from esophageal varices. However, this finding can be subjective, and the endoscopist must individualize the decision for banding based on the size and appearance of the varices. It was reasonable to proceed with banding this time because the varices were large, had a red wale sign, and there was otherwise unexplained ongoing bleeding. Because her hemoglobin continued to drop after the banding and a tagged RBC study best localized the bleeding to the small intestine or transverse colon, it is unlikely that the varices are the primary source of bleeding. It is not surprising that the mesenteric angiogram did not show a source of bleeding, because this study requires active bleeding at a sufficient rate to radiographically identify the source.

The leading diagnosis remains an as yet uncharacterized small bowel bleeding source related to mesenteric thrombotic disease. Cross‐sectional imaging with IV contrast to identify significant vascular occlusion should be the next diagnostic step. Capsule endoscopy would be a more expensive and time‐consuming option, and although this could reveal the source of bleeding, it might not characterize the underlying vascular nature of the problem.

Due to persistent abdominal pain, a CT without intravenous contrast was done on hospital day 10. This showed extensive collateral vessels along the chest and abdominal wall with a distended azygos vein. The study was otherwise unrevealing. Her bloody stools cleared, so she was discharged with a plan for capsule endoscopy and outpatient follow‐up with her gastroenterologist. On the day of discharge (hospital day 11), hemoglobin was 7.5 g/dL and she received an eighth unit of packed RBCs. Overt bleeding was absent.

As an outpatient, intermittent hematochezia and melena recurred. The capsule endoscopy showed active bleeding approximately 45 minutes after the capsule exited the stomach. The lesion was not precisely located or characterized, but was believed to be in the distal small bowel.

The capsule finding supports the growing body of evidence implicating a small bowel source of bleeding. Furthermore, the ongoing but slow rate of blood loss makes a venous bleed more likely than an arterial bleed. A CT scan was performed prior to capsule study, but this was done without intravenous contrast. The brief description of the CT findings emphasizes the subcutaneous venous changes; a contraindication to IV contrast is not mentioned. Certainly IV contrast would have been very helpful to characterize the mesenteric arterial and venous vasculature. If there is no contraindication, a repeat CT scan with IV contrast should be performed. If there is a contraindication to IV contrast, it would be beneficial to revisit the noncontrast study with the specific purpose of searching for clues suggesting mesenteric or portal thrombosis. If the source still remains unclear, the next steps should be to perform push enteroscopy to assess the small intestine from the luminal side and magnetic resonance angiogram with venous phase imaging (or CT venogram if there is no contraindication to contrast) to evaluate the venous circulation.

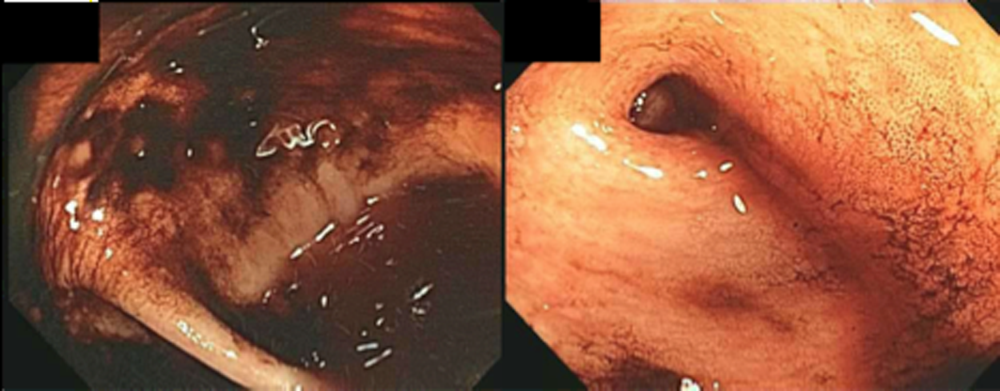

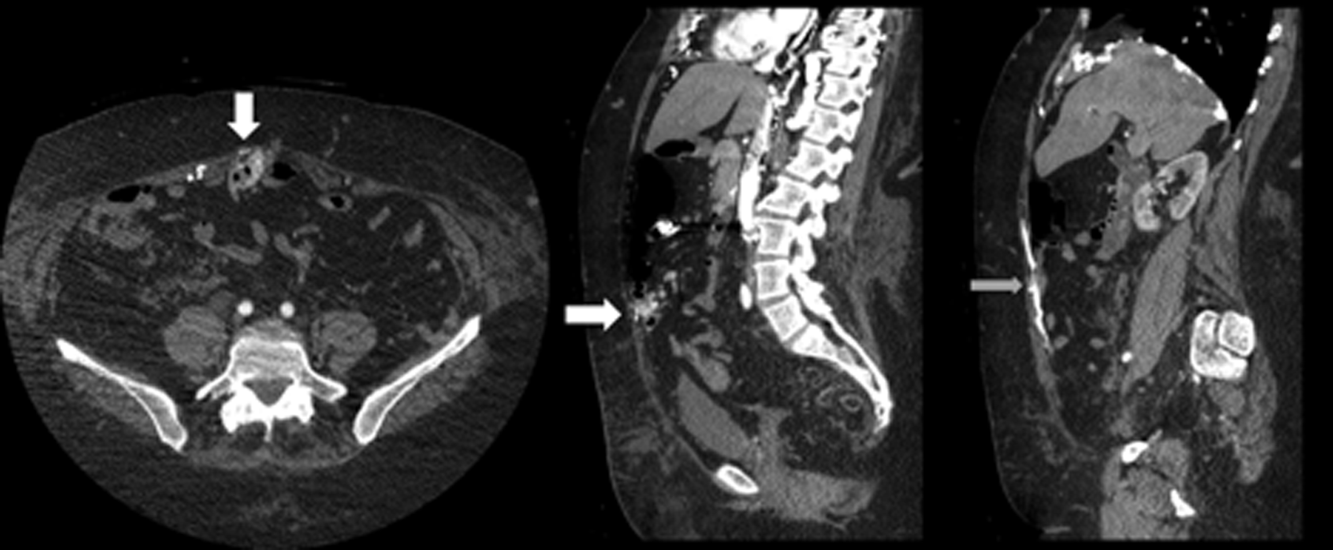

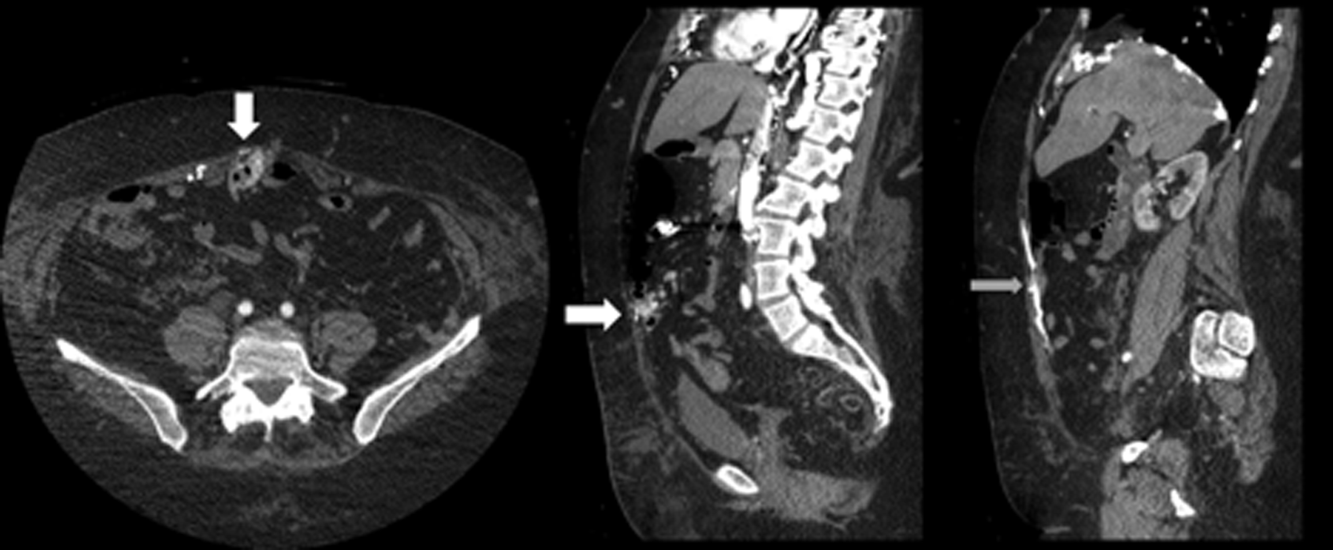

The patient was readmitted 9 days after discharge with persistent melena and hematochezia. Her hemoglobin was 7.2 g/dL. Given the lack of a diagnosis, the patient was transferred to a tertiary care hospital, where a second colonoscopy and mesenteric angiogram were negative for bleeding. Small bowel enteroscopy showed no source of bleeding up to 60 cm past the pylorus. A third colonoscopy was performed due to recurrent bleeding; this showed a large amount of dark blood and clots throughout the entire colon including the cecum (Figure 2). After copious irrigation, the underlying mucosa was seen to be normal. At this point, a CT angiogram with both venous and arterial phases was done due to the high suspicion for a distal jejunal bleeding source. The CT angiogram showed numerous venous collaterals encasing a loop of midsmall bowel demonstrating progressive submucosal venous enhancement. In addition, a venous collateral ran down the right side of the sternum to the infraumbilical area and drained through the encasing collaterals into the portal venous system (Figure 3). The CT scan also revealed IVC obstruction below the distal IVC filter and an enlarged portal vein measuring 18 mm (normal 12 mm).

The CT angiogram provides much‐needed clarity. The continued bleeding is likely due to ectopic varices in the small bowel. The venous phase of the CT angiogram shows thrombosis of key venous structures and evidence of a dilated portal vein (indicating portal hypertension) leading to ectopic varices in the abdominal wall and jejunum. Given the prior studies that suggest a small bowel source of bleeding, jejunal varices are the most likely cause of recurrent GI bleeding in this patient.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy. Loops of small bowel were found to be adherent to the hysterectomy scar. There were many venous collaterals from the abdominal wall to these loops of bowel, dilating the veins both in intestinal walls and those in the adjacent mesentery. After clamping these veins, the small bowel was detached from the abdominal wall. On unclamping, the collaterals bled with a high venous pressure. Because these systemic‐portal shunts were responsible for the bleeding, the collaterals were sutured, stopping the bleeding. Thus, partial small bowel resection was not necessary. Postoperatively, her bleeding resolved completely and she maintained normal hemoglobin at 1‐year follow‐up.

COMMENTARY

The axiom common ailments are encountered most frequently underpins the classical stepwise approach to GI bleeding. First, a focused history helps localize the source of bleeding to the upper or lower GI tract. Next, endoscopy is performed to identify and treat the cause of bleeding. Finally, advanced tests such as angiography and capsule endoscopy are performed if needed. For this patient, following the usual algorithm failed to make the diagnosis or stop the bleeding. Despite historical and examination features suggesting that her case fell outside of the common patterns of GI bleeding, this patient underwent 3 upper endoscopies, 3 colonoscopies, a capsule endoscopy, a technetium‐tagged RBC study, 2 mesenteric angiograms, and a noncontrast CT scan before the study that was ultimately diagnostic was performed. The clinicians caring for this patient struggled to incorporate the atypical features of her history and presentation and failed to take an earlier detour from the usual algorithm. Instead, the same studies that had not previously led to the diagnosis were repeated multiple times.

Ectopic varices are enlarged portosystemic venous collaterals located anywhere outside the gastroesophageal region.[1] They occur in the setting of portal hypertension, surgical procedures involving abdominal viscera and vasculature, and venous occlusion. Ectopic varices account for 4% to 5% of all variceal bleeding episodes.[1] The most common sites include the anorectal junction (44%), duodenum (17%33%), jejunum/emleum (5%17%), colon (3.5%14%), and sites of previous abdominal surgery.[2, 3] Ectopic varices can cause either luminal or extraluminal (i.e., peritoneal) bleeding.[3] Luminal bleeding, seen in this case, is caused by venous protrusion into the submucosa. Ectopic varices present as a slow venous ooze, which explains this patient's ongoing requirement for recurrent blood transfusions.[4]

In this patient, submucosal ectopic varices developed as a result of a combination of known risk factors: portal hypertension in the setting of chronic venous occlusion from her hypercoagulability and a history of abdominal surgery (hysterectomy). [5] The apposition of her abdominal wall structures (drained by the systemic veins) to the bowel (drained by the portal veins) resulted in adhesion formation, detour of venous flow, collateralization, and submucosal varix formation.[1, 2, 6]

The key diagnostic study for this patient was a CT angiogram, with both arterial and venous phases. The prior 2 mesenteric angiograms had been limited to the arterial phase, which had missed identifying the venous abnormalities altogether. This highlights an important lesson from this case: contrast‐enhanced CT may have a higher yield in diagnosing ectopic varices compared to repeated endoscopiesespecially when captured in the late venous phaseand should strongly be considered for unexplained bleeding in patients with stigmata of liver disease or portal hypertension.[7, 8] Another clue for ectopic varices in a bleeding patient are nonbleeding esophageal or gastric varices, as was the case in this patient.[9]

The initial management of ectopic varices is similar to bleeding secondary to esophageal varices.[1] Definitive treatment includes endoscopic embolization or ligation, interventional radiological procedures such as portosystemic shunting or percutaneous embolization, and exploratory laparotomy to either resect the segment of bowel that is the source of bleeding or to decompress the collaterals surgically.[9] Although endoscopic ligation has been shown to have a lower rebleeding rate and mortality compared to endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in patients with esophageal varices, the data are too sparse in jejunal varices to recommend 1 treatment over another. Both have been used successfully either alone or in combination with each other, and can be useful alternatives for patients who are unable to undergo laparotomy.[9]

Diagnostic errors due to cognitive biases can be avoided by following diagnostic algorithms. However, over‐reliance on algorithms can result in vertical line failure, a form of cognitive bias in which the clinician subconsciously adheres to an inflexible diagnostic approach.[10] To overcome this bias, clinicians need to think laterally and consider alternative diagnoses when algorithms do not lead to expected outcomes. This case highlights the challenges of knowing when to break free of conventional approaches and the rewards of taking a well‐chosen detour that leads to the diagnosis.

KEY POINTS

- Recurrent, occult gastrointestinal bleeding should raise concern for a small bowel source, and clinicians may need to take a detour away from the usual workup to arrive at a diagnosis.

- CT angiography of the abdomen and pelvis may miss venous sources of bleeding, unless a venous phase is specifically requested.

- Ectopic varices can occur in patients with portal hypertension who have had a history of abdominal surgery; these patients can develop venous collaterals for decompression into the systemic circulation through the abdominal wall.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:322–334.

- , , . Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. 1998;28:1154–1158.

- , , , et al. Current status of ectopic varices in Japan: results of a survey by the Japan Society for Portal Hypertension. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:763–766.

- , , . Stomal Varices: Management with decompression TIPS and transvenous obliteration or sclerosis. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16:126–134.

- , , , et al. Jejunal varices as a cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:514–517.

- , . Ectopic varices in portal hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;14:105–121.

- , , , et al. Ectopic varices in portal hypertension: computed tomographic angiography instead of repeated endoscopies for diagnosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:620–622.

- , , , et al. ACR appropriateness criteria. Radiologic management of lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2011. Available at: http://www.acr.org/Quality‐Safety/Appropriateness‐Criteria/∼/media/5F9CB95C164E4DA19DCBCFBBA790BB3C.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- , . Diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Gastrointest Interv. 2012;1:3–10.

- . Achieving quality in clinical decision making: cognitive strategies and detection of bias. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1184–1204.