User login

Pegylated rFVIII product produces favorable results in hemophilia A

An investigational recombinant factor VIII (rFVIII) product can safely treat and prevent bleeding in previously treated patients with hemophilia A, according to researchers.

The product, BAX 855, is a pegylated version of ADVATE, a full-length rFVIII product already approved to treat hemophilia A.

BAX 855 was designed to have a longer half-life than ADVATE, thereby allowing for fewer prophylactic infusions without affecting hemostatic efficacy.

Results of a phase 1 study showed that BAX 855 had a longer half-life and mean residence time than ADVATE. And results of a phase 2/3 study showed that twice-weekly prophylactic treatment with BAX 855 lowered the median annualized bleed rate (ABR) when compared to on-demand treatment with BAX 855.

None of the patients who received BAX 855 in either study developed inhibitors, and there were no serious adverse events (AEs) that were considered treatment-related.

Results from both trials were published in Blood. The research was funded by Baxalta, a spin-off of Baxter Healthcare Corporation.

Study characteristics

The phase 1 study included 19 previously treated patients with severe hemophilia A and a median age of 29 (range, 18-60). The patients received single infusions of ADVATE followed by BAX 855 (after a wash-out period) at 30 IU/kg or 60 IU/kg.

In the phase 2/3 trial, researchers evaluated BAX 855 in 137 previously treated patients with hemophilia A. These patients also had a median age of 29 (range, 12-58).

They were assigned to either twice-weekly prophylaxis (40-50 IU/kg, n=120) or on-demand treatment (10-60 IU/kg, n=17) with BAX 855. One hundred and twenty-six patients completed the study.

Pharmacokinetics and safety

In the phase 1 study, the mean residence time was higher with BAX 855 than with ADVATE—1.4-fold higher in the 30 IU/kg arm and 1.5-fold higher in the 60 IU/kg arm. The mean half-life was higher with BAX 855 as well—1.4-fold higher in the 30 IU/kg arm and 1.5-fold in the 60 IU/kg arm.

Results were similar in the phase 2/3 trial.

None of the subjects in the phase 1 study experienced a serious AE after their single infusion of BAX 855. Eight patients experienced a total of 11 non-serious AEs, none of which were considered related to BAX 855.

In the phase 2/3 study, there were 171 AEs in 73 patients who received BAX 855 for about 6 months. There were 7 AEs (occurring in 6 patients) that were considered possibly related to BAX 855. These included diarrhea, nausea, headache, and flushing.

There were 5 serious AEs (occurring in 5 patients) that were not considered treatment-related. These included osteoarthritis, herpes zoster infection, humerus fracture, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and muscle hemorrhage.

Efficacy: Prophylaxis and on-demand

The researchers only assessed the efficacy of BAX 855 prophylaxis and on-demand treatment in the phase 2/3 study.

Patients received a median dose of 44.6 IU/kg per prophylactic infusion. The mean reduction in dosing frequency from pre-study prophylaxis was 26.7%, and 70.4% of patients were able to reduce the frequency of dosing by 30% or more. This is roughly equivalent to at least 1 less prophylactic infusion per week.

Patients who received prophylaxis had a 90% reduction in ABR compared to those who received on-demand treatment. The median ABR was 1.9 in the prophylactic arm and 41.5 in the on-demand arm.

The ABRs for joint bleeds or spontaneous/unknown bleeds were both 0 in the prophylactic arm, compared to 38.1 and 21.6, respectively, in the on-demand treatment arm.

Patients who received on-demand treatment were given a median dose of 30.87 IU/kg per episode and 29.19 IU/kg for the maintenance of hemostasis.

Of the 518 bleeding episodes reported during the study, 95.9% were treated with 1 or 2 infusions of BAX 855. The mean number of infusions required to treat a bleeding episode was 1.2. ![]()

An investigational recombinant factor VIII (rFVIII) product can safely treat and prevent bleeding in previously treated patients with hemophilia A, according to researchers.

The product, BAX 855, is a pegylated version of ADVATE, a full-length rFVIII product already approved to treat hemophilia A.

BAX 855 was designed to have a longer half-life than ADVATE, thereby allowing for fewer prophylactic infusions without affecting hemostatic efficacy.

Results of a phase 1 study showed that BAX 855 had a longer half-life and mean residence time than ADVATE. And results of a phase 2/3 study showed that twice-weekly prophylactic treatment with BAX 855 lowered the median annualized bleed rate (ABR) when compared to on-demand treatment with BAX 855.

None of the patients who received BAX 855 in either study developed inhibitors, and there were no serious adverse events (AEs) that were considered treatment-related.

Results from both trials were published in Blood. The research was funded by Baxalta, a spin-off of Baxter Healthcare Corporation.

Study characteristics

The phase 1 study included 19 previously treated patients with severe hemophilia A and a median age of 29 (range, 18-60). The patients received single infusions of ADVATE followed by BAX 855 (after a wash-out period) at 30 IU/kg or 60 IU/kg.

In the phase 2/3 trial, researchers evaluated BAX 855 in 137 previously treated patients with hemophilia A. These patients also had a median age of 29 (range, 12-58).

They were assigned to either twice-weekly prophylaxis (40-50 IU/kg, n=120) or on-demand treatment (10-60 IU/kg, n=17) with BAX 855. One hundred and twenty-six patients completed the study.

Pharmacokinetics and safety

In the phase 1 study, the mean residence time was higher with BAX 855 than with ADVATE—1.4-fold higher in the 30 IU/kg arm and 1.5-fold higher in the 60 IU/kg arm. The mean half-life was higher with BAX 855 as well—1.4-fold higher in the 30 IU/kg arm and 1.5-fold in the 60 IU/kg arm.

Results were similar in the phase 2/3 trial.

None of the subjects in the phase 1 study experienced a serious AE after their single infusion of BAX 855. Eight patients experienced a total of 11 non-serious AEs, none of which were considered related to BAX 855.

In the phase 2/3 study, there were 171 AEs in 73 patients who received BAX 855 for about 6 months. There were 7 AEs (occurring in 6 patients) that were considered possibly related to BAX 855. These included diarrhea, nausea, headache, and flushing.

There were 5 serious AEs (occurring in 5 patients) that were not considered treatment-related. These included osteoarthritis, herpes zoster infection, humerus fracture, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and muscle hemorrhage.

Efficacy: Prophylaxis and on-demand

The researchers only assessed the efficacy of BAX 855 prophylaxis and on-demand treatment in the phase 2/3 study.

Patients received a median dose of 44.6 IU/kg per prophylactic infusion. The mean reduction in dosing frequency from pre-study prophylaxis was 26.7%, and 70.4% of patients were able to reduce the frequency of dosing by 30% or more. This is roughly equivalent to at least 1 less prophylactic infusion per week.

Patients who received prophylaxis had a 90% reduction in ABR compared to those who received on-demand treatment. The median ABR was 1.9 in the prophylactic arm and 41.5 in the on-demand arm.

The ABRs for joint bleeds or spontaneous/unknown bleeds were both 0 in the prophylactic arm, compared to 38.1 and 21.6, respectively, in the on-demand treatment arm.

Patients who received on-demand treatment were given a median dose of 30.87 IU/kg per episode and 29.19 IU/kg for the maintenance of hemostasis.

Of the 518 bleeding episodes reported during the study, 95.9% were treated with 1 or 2 infusions of BAX 855. The mean number of infusions required to treat a bleeding episode was 1.2. ![]()

An investigational recombinant factor VIII (rFVIII) product can safely treat and prevent bleeding in previously treated patients with hemophilia A, according to researchers.

The product, BAX 855, is a pegylated version of ADVATE, a full-length rFVIII product already approved to treat hemophilia A.

BAX 855 was designed to have a longer half-life than ADVATE, thereby allowing for fewer prophylactic infusions without affecting hemostatic efficacy.

Results of a phase 1 study showed that BAX 855 had a longer half-life and mean residence time than ADVATE. And results of a phase 2/3 study showed that twice-weekly prophylactic treatment with BAX 855 lowered the median annualized bleed rate (ABR) when compared to on-demand treatment with BAX 855.

None of the patients who received BAX 855 in either study developed inhibitors, and there were no serious adverse events (AEs) that were considered treatment-related.

Results from both trials were published in Blood. The research was funded by Baxalta, a spin-off of Baxter Healthcare Corporation.

Study characteristics

The phase 1 study included 19 previously treated patients with severe hemophilia A and a median age of 29 (range, 18-60). The patients received single infusions of ADVATE followed by BAX 855 (after a wash-out period) at 30 IU/kg or 60 IU/kg.

In the phase 2/3 trial, researchers evaluated BAX 855 in 137 previously treated patients with hemophilia A. These patients also had a median age of 29 (range, 12-58).

They were assigned to either twice-weekly prophylaxis (40-50 IU/kg, n=120) or on-demand treatment (10-60 IU/kg, n=17) with BAX 855. One hundred and twenty-six patients completed the study.

Pharmacokinetics and safety

In the phase 1 study, the mean residence time was higher with BAX 855 than with ADVATE—1.4-fold higher in the 30 IU/kg arm and 1.5-fold higher in the 60 IU/kg arm. The mean half-life was higher with BAX 855 as well—1.4-fold higher in the 30 IU/kg arm and 1.5-fold in the 60 IU/kg arm.

Results were similar in the phase 2/3 trial.

None of the subjects in the phase 1 study experienced a serious AE after their single infusion of BAX 855. Eight patients experienced a total of 11 non-serious AEs, none of which were considered related to BAX 855.

In the phase 2/3 study, there were 171 AEs in 73 patients who received BAX 855 for about 6 months. There were 7 AEs (occurring in 6 patients) that were considered possibly related to BAX 855. These included diarrhea, nausea, headache, and flushing.

There were 5 serious AEs (occurring in 5 patients) that were not considered treatment-related. These included osteoarthritis, herpes zoster infection, humerus fracture, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and muscle hemorrhage.

Efficacy: Prophylaxis and on-demand

The researchers only assessed the efficacy of BAX 855 prophylaxis and on-demand treatment in the phase 2/3 study.

Patients received a median dose of 44.6 IU/kg per prophylactic infusion. The mean reduction in dosing frequency from pre-study prophylaxis was 26.7%, and 70.4% of patients were able to reduce the frequency of dosing by 30% or more. This is roughly equivalent to at least 1 less prophylactic infusion per week.

Patients who received prophylaxis had a 90% reduction in ABR compared to those who received on-demand treatment. The median ABR was 1.9 in the prophylactic arm and 41.5 in the on-demand arm.

The ABRs for joint bleeds or spontaneous/unknown bleeds were both 0 in the prophylactic arm, compared to 38.1 and 21.6, respectively, in the on-demand treatment arm.

Patients who received on-demand treatment were given a median dose of 30.87 IU/kg per episode and 29.19 IU/kg for the maintenance of hemostasis.

Of the 518 bleeding episodes reported during the study, 95.9% were treated with 1 or 2 infusions of BAX 855. The mean number of infusions required to treat a bleeding episode was 1.2. ![]()

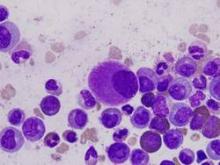

CML patients die from comorbidities, not leukemia

Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) treated with imatinib are much more likely to die from their comorbid conditions than from the leukemia, according to a report published in Blood.

During the past decade, CML has been transformed from a routinely fatal disease to a chronic condition controlled by regular drug therapy using imatinib and newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The influence of comorbidities on survival outcomes has not been studied until now, said Dr. Susanne Saussele of Heidelberg University, Mannheim (Germany), and her associates.

They used data from a large German study of first-line imatinib therapy, focusing on 1,519 CML patients who were evaluable after a median follow-up of 68 months. Approximately 40% of these study participants had one or more of 511 evaluable comorbidities. The most common conditions relevant to CML and its treatment were diabetes, nonactive cancer other than CML, chronic pulmonary disease, renal insufficiency, MI, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease.

Study participants were categorized by the number and severity of their comorbidities using the Charlson Comorbidity Index as CCI 2 (589 patients), CCI 3 or 4 (599 patients), CCI 5 or 6 (229 patients), or CCI 7 and above (102 patients), with higher levels indicating a greater burden of comorbidity. Overall 8-year survival probabilities directly correlated with CCI category, at 94% for CCI 2, 89% for CCI 3 or 4, 78% for CCI 5 or 6, and 46% for CCI 7 or above. In addition, CCI score was the most powerful predictor of overall survival, the researchers said (Blood 2015;126:42-9).

Comorbidities had no impact on the success of imatinib therapy. Even patients with multiple or severe comorbidities derived significant benefit from imatinib, and comorbidities had no negative effect on remission rates or disease progression. Taken together with comorbidities’ strong influence on mortality, this indicates that patients’ survival is determined more by their comorbidities than by CML itself, Dr. Saussele and her associates said.

Their findings also showed that overall survival alone is no longer an appropriate endpoint for assessing treatment efficacy in CML. Progression-free survival seems to be a more accurate measure of treatment effect, since it was not influenced by comorbidities in this study, they added.

Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) treated with imatinib are much more likely to die from their comorbid conditions than from the leukemia, according to a report published in Blood.

During the past decade, CML has been transformed from a routinely fatal disease to a chronic condition controlled by regular drug therapy using imatinib and newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The influence of comorbidities on survival outcomes has not been studied until now, said Dr. Susanne Saussele of Heidelberg University, Mannheim (Germany), and her associates.

They used data from a large German study of first-line imatinib therapy, focusing on 1,519 CML patients who were evaluable after a median follow-up of 68 months. Approximately 40% of these study participants had one or more of 511 evaluable comorbidities. The most common conditions relevant to CML and its treatment were diabetes, nonactive cancer other than CML, chronic pulmonary disease, renal insufficiency, MI, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease.

Study participants were categorized by the number and severity of their comorbidities using the Charlson Comorbidity Index as CCI 2 (589 patients), CCI 3 or 4 (599 patients), CCI 5 or 6 (229 patients), or CCI 7 and above (102 patients), with higher levels indicating a greater burden of comorbidity. Overall 8-year survival probabilities directly correlated with CCI category, at 94% for CCI 2, 89% for CCI 3 or 4, 78% for CCI 5 or 6, and 46% for CCI 7 or above. In addition, CCI score was the most powerful predictor of overall survival, the researchers said (Blood 2015;126:42-9).

Comorbidities had no impact on the success of imatinib therapy. Even patients with multiple or severe comorbidities derived significant benefit from imatinib, and comorbidities had no negative effect on remission rates or disease progression. Taken together with comorbidities’ strong influence on mortality, this indicates that patients’ survival is determined more by their comorbidities than by CML itself, Dr. Saussele and her associates said.

Their findings also showed that overall survival alone is no longer an appropriate endpoint for assessing treatment efficacy in CML. Progression-free survival seems to be a more accurate measure of treatment effect, since it was not influenced by comorbidities in this study, they added.

Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) treated with imatinib are much more likely to die from their comorbid conditions than from the leukemia, according to a report published in Blood.

During the past decade, CML has been transformed from a routinely fatal disease to a chronic condition controlled by regular drug therapy using imatinib and newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The influence of comorbidities on survival outcomes has not been studied until now, said Dr. Susanne Saussele of Heidelberg University, Mannheim (Germany), and her associates.

They used data from a large German study of first-line imatinib therapy, focusing on 1,519 CML patients who were evaluable after a median follow-up of 68 months. Approximately 40% of these study participants had one or more of 511 evaluable comorbidities. The most common conditions relevant to CML and its treatment were diabetes, nonactive cancer other than CML, chronic pulmonary disease, renal insufficiency, MI, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease.

Study participants were categorized by the number and severity of their comorbidities using the Charlson Comorbidity Index as CCI 2 (589 patients), CCI 3 or 4 (599 patients), CCI 5 or 6 (229 patients), or CCI 7 and above (102 patients), with higher levels indicating a greater burden of comorbidity. Overall 8-year survival probabilities directly correlated with CCI category, at 94% for CCI 2, 89% for CCI 3 or 4, 78% for CCI 5 or 6, and 46% for CCI 7 or above. In addition, CCI score was the most powerful predictor of overall survival, the researchers said (Blood 2015;126:42-9).

Comorbidities had no impact on the success of imatinib therapy. Even patients with multiple or severe comorbidities derived significant benefit from imatinib, and comorbidities had no negative effect on remission rates or disease progression. Taken together with comorbidities’ strong influence on mortality, this indicates that patients’ survival is determined more by their comorbidities than by CML itself, Dr. Saussele and her associates said.

Their findings also showed that overall survival alone is no longer an appropriate endpoint for assessing treatment efficacy in CML. Progression-free survival seems to be a more accurate measure of treatment effect, since it was not influenced by comorbidities in this study, they added.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with imatinib are much more likely to die from comorbid conditions than from leukemia.

Major finding: Overall 8-year survival probabilities directly correlated with CCI category, at 94% for CCI 2, 89% for CCI 3 or 4, 78% for CCI 5 or 6, and 46% for CCI 7 or above.

Data source: A secondary analysis of data in a nationwide German study involving 1,519 patients treated with imatinib and followed for a median of 68 months.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe, Novartis, Kompetenznetz für Akute und Chronische Leukämien, Deutsche Jose-Carreras Leukämiestiftung, European LeukemiaNet, Roche, and Essex Pharma. Dr. Saussele reported honoraria and research funding from Pfizer, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and her associates reported ties to these companies and ARIAD.

Moderate THST was most effective at treating thyroid cancer

Moderate thyroid hormone suppression therapy (THST) is associated with the best outcomes for patients with all stages of thyroid cancer, according to a prospective analysis of a multi-institutional registry published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

The researchers examined the outcomes of initial treatment for 4,941 patients with differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC), according to registry data from the National Thyroid Cancer Treatment Cooperative Study Group. The treatments included total/near total thyroidectomy (T/NTT), postoperative radioactive iodine-131 (131I), and THST. The median duration between treatment and follow-up for a patient was 6 years, with follow-up information available for all but 94 (1.9%) of the patients in the cohort.

Overall improvement was noted in stage III patients who received 131I (risk ratio, 0.66; P = .04) and stage IV patients who received both T/NTT and 131I (RR, 0.66; P = .049). In all stages, moderate THST was associated with significantly improved overall survival (RR stages I-IV: 0.13, 0.09, 0.13, and 0.33, respectively) and disease-free survival (DFS) (RR stages I-III: 0.52, 0.40, and 0.18, respectively); no additional survival benefit was achieved with more aggressive THST, even when distant metastatic disease was diagnosed during follow-up.

Lower initial stage and moderate THST were independent predictors of improved overall survival during follow-up years 1-3.

Consistent with previous research, this study also showed that T/NTT followed by 131I is associated with benefit in high-risk, but not low-risk patients.

“We report for the first time, in multivariate analysis of primary treatments for DTC, across all stages, only THST was associated with both improved stage-adjusted OS and DFS,” noted Dr. Aubrey A. Carhill and his colleagues.

“This analysis of the larger, more mature registry database extends and refines earlier observations regarding the impact of initial therapies on patient outcomes and further justifies the need for prospective, long-term, controlled studies,” the researchers noted.

Read the full study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (doi:10.1210/JC.2015-1346).

Moderate thyroid hormone suppression therapy (THST) is associated with the best outcomes for patients with all stages of thyroid cancer, according to a prospective analysis of a multi-institutional registry published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

The researchers examined the outcomes of initial treatment for 4,941 patients with differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC), according to registry data from the National Thyroid Cancer Treatment Cooperative Study Group. The treatments included total/near total thyroidectomy (T/NTT), postoperative radioactive iodine-131 (131I), and THST. The median duration between treatment and follow-up for a patient was 6 years, with follow-up information available for all but 94 (1.9%) of the patients in the cohort.

Overall improvement was noted in stage III patients who received 131I (risk ratio, 0.66; P = .04) and stage IV patients who received both T/NTT and 131I (RR, 0.66; P = .049). In all stages, moderate THST was associated with significantly improved overall survival (RR stages I-IV: 0.13, 0.09, 0.13, and 0.33, respectively) and disease-free survival (DFS) (RR stages I-III: 0.52, 0.40, and 0.18, respectively); no additional survival benefit was achieved with more aggressive THST, even when distant metastatic disease was diagnosed during follow-up.

Lower initial stage and moderate THST were independent predictors of improved overall survival during follow-up years 1-3.

Consistent with previous research, this study also showed that T/NTT followed by 131I is associated with benefit in high-risk, but not low-risk patients.

“We report for the first time, in multivariate analysis of primary treatments for DTC, across all stages, only THST was associated with both improved stage-adjusted OS and DFS,” noted Dr. Aubrey A. Carhill and his colleagues.

“This analysis of the larger, more mature registry database extends and refines earlier observations regarding the impact of initial therapies on patient outcomes and further justifies the need for prospective, long-term, controlled studies,” the researchers noted.

Read the full study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (doi:10.1210/JC.2015-1346).

Moderate thyroid hormone suppression therapy (THST) is associated with the best outcomes for patients with all stages of thyroid cancer, according to a prospective analysis of a multi-institutional registry published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

The researchers examined the outcomes of initial treatment for 4,941 patients with differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC), according to registry data from the National Thyroid Cancer Treatment Cooperative Study Group. The treatments included total/near total thyroidectomy (T/NTT), postoperative radioactive iodine-131 (131I), and THST. The median duration between treatment and follow-up for a patient was 6 years, with follow-up information available for all but 94 (1.9%) of the patients in the cohort.

Overall improvement was noted in stage III patients who received 131I (risk ratio, 0.66; P = .04) and stage IV patients who received both T/NTT and 131I (RR, 0.66; P = .049). In all stages, moderate THST was associated with significantly improved overall survival (RR stages I-IV: 0.13, 0.09, 0.13, and 0.33, respectively) and disease-free survival (DFS) (RR stages I-III: 0.52, 0.40, and 0.18, respectively); no additional survival benefit was achieved with more aggressive THST, even when distant metastatic disease was diagnosed during follow-up.

Lower initial stage and moderate THST were independent predictors of improved overall survival during follow-up years 1-3.

Consistent with previous research, this study also showed that T/NTT followed by 131I is associated with benefit in high-risk, but not low-risk patients.

“We report for the first time, in multivariate analysis of primary treatments for DTC, across all stages, only THST was associated with both improved stage-adjusted OS and DFS,” noted Dr. Aubrey A. Carhill and his colleagues.

“This analysis of the larger, more mature registry database extends and refines earlier observations regarding the impact of initial therapies on patient outcomes and further justifies the need for prospective, long-term, controlled studies,” the researchers noted.

Read the full study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (doi:10.1210/JC.2015-1346).

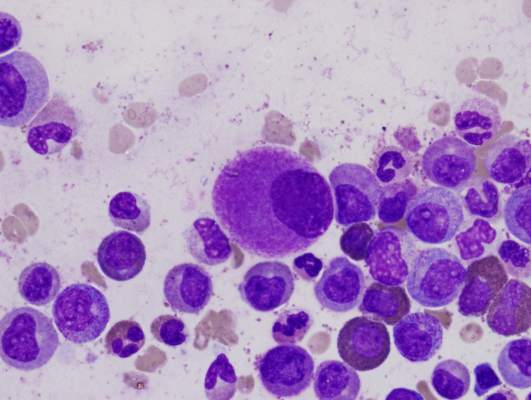

Carrier Screening for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an X-linked condition, is the most common muscular dystrophy in children and affects families of all ethnicities. Incidence is about 1 in 3,500 boys. Approximately two-thirds of clinically diagnosed cases of DMD are attributable to a carrier mother, who is likely unaware that she is a carrier. In addition to providing information about reproductive risks, carrier screening can identify women who are, themselves, at risk of health effects caused by defects in the DMD gene.

This supplement examines the latest crucial advances in DMD carrier screening.

Click here to download the PDF.

To view an exclusive video on the pivotal findings discussed in this supplement, click here.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an X-linked condition, is the most common muscular dystrophy in children and affects families of all ethnicities. Incidence is about 1 in 3,500 boys. Approximately two-thirds of clinically diagnosed cases of DMD are attributable to a carrier mother, who is likely unaware that she is a carrier. In addition to providing information about reproductive risks, carrier screening can identify women who are, themselves, at risk of health effects caused by defects in the DMD gene.

This supplement examines the latest crucial advances in DMD carrier screening.

Click here to download the PDF.

To view an exclusive video on the pivotal findings discussed in this supplement, click here.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an X-linked condition, is the most common muscular dystrophy in children and affects families of all ethnicities. Incidence is about 1 in 3,500 boys. Approximately two-thirds of clinically diagnosed cases of DMD are attributable to a carrier mother, who is likely unaware that she is a carrier. In addition to providing information about reproductive risks, carrier screening can identify women who are, themselves, at risk of health effects caused by defects in the DMD gene.

This supplement examines the latest crucial advances in DMD carrier screening.

Click here to download the PDF.

To view an exclusive video on the pivotal findings discussed in this supplement, click here.

Corpus callosum functioning, structural integrity impaired in some TBI patients

Half of moderate to severe traumatic brain injury patients had markedly impaired corpus callosum (CC) functioning and structural integrity that is associated with poor neurocognitive functioning, according to a study of children aged 8-19 years.

The researchers used high angular resolution diffusion-weighted imaging to determine the structural integrities of the CC in 32 children who had suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) and of the CC in 31 healthy children. Patients in the experimental group had suffered from a moderate to severe TBI 1-5 months prior to the study. The researchers assessed CC function through interhemispheric transfer time (IHTT) – the time required to transfer stimulus-locked neural activity between the left and right brain hemispheres. Each participant’s IHTT was calculated from recording electroencephalography, while he or she completed a computerized, pattern-matching task with bilateral field advantage.

Half of the TBI patients had significantly slower IHTTs than did the control group. The IHTTs of this so-called IHTT-slow TBI group deviated by at least 1.5 standard deviations from data for the healthy control group.

The IHTT-slow TBI group also demonstrated lower CC integrity and poorer neurocognitive functioning than did both the control group and the remaining members of the experimental group. Lower fractional anisotropy (FA) – a common sign of impaired white matter (WM) – and slower IHTTs also predicted poor neurocognitive function.

“When we compared the IHTT-slow TBI group to the healthy control group, we found significant differences in callosal WM integrity, as well as the integrity of the association and projection tract systems tested. Lower FA and higher mean diffusivity (MD) in the IHTT-slow group suggests myelin disruption,” noted Emily L Dennis of the University of Southern California, Marina del Rey, and her colleagues. “When we compared the IHTT-normal TBI group to the healthy control group, we found only a few areas where the TBI group had significantly lower FA and no significant differences in MD [mean diffusivity].”

Read the full study in the Journal of Neuroscience (doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1595-15.2015).

Half of moderate to severe traumatic brain injury patients had markedly impaired corpus callosum (CC) functioning and structural integrity that is associated with poor neurocognitive functioning, according to a study of children aged 8-19 years.

The researchers used high angular resolution diffusion-weighted imaging to determine the structural integrities of the CC in 32 children who had suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) and of the CC in 31 healthy children. Patients in the experimental group had suffered from a moderate to severe TBI 1-5 months prior to the study. The researchers assessed CC function through interhemispheric transfer time (IHTT) – the time required to transfer stimulus-locked neural activity between the left and right brain hemispheres. Each participant’s IHTT was calculated from recording electroencephalography, while he or she completed a computerized, pattern-matching task with bilateral field advantage.

Half of the TBI patients had significantly slower IHTTs than did the control group. The IHTTs of this so-called IHTT-slow TBI group deviated by at least 1.5 standard deviations from data for the healthy control group.

The IHTT-slow TBI group also demonstrated lower CC integrity and poorer neurocognitive functioning than did both the control group and the remaining members of the experimental group. Lower fractional anisotropy (FA) – a common sign of impaired white matter (WM) – and slower IHTTs also predicted poor neurocognitive function.

“When we compared the IHTT-slow TBI group to the healthy control group, we found significant differences in callosal WM integrity, as well as the integrity of the association and projection tract systems tested. Lower FA and higher mean diffusivity (MD) in the IHTT-slow group suggests myelin disruption,” noted Emily L Dennis of the University of Southern California, Marina del Rey, and her colleagues. “When we compared the IHTT-normal TBI group to the healthy control group, we found only a few areas where the TBI group had significantly lower FA and no significant differences in MD [mean diffusivity].”

Read the full study in the Journal of Neuroscience (doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1595-15.2015).

Half of moderate to severe traumatic brain injury patients had markedly impaired corpus callosum (CC) functioning and structural integrity that is associated with poor neurocognitive functioning, according to a study of children aged 8-19 years.

The researchers used high angular resolution diffusion-weighted imaging to determine the structural integrities of the CC in 32 children who had suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) and of the CC in 31 healthy children. Patients in the experimental group had suffered from a moderate to severe TBI 1-5 months prior to the study. The researchers assessed CC function through interhemispheric transfer time (IHTT) – the time required to transfer stimulus-locked neural activity between the left and right brain hemispheres. Each participant’s IHTT was calculated from recording electroencephalography, while he or she completed a computerized, pattern-matching task with bilateral field advantage.

Half of the TBI patients had significantly slower IHTTs than did the control group. The IHTTs of this so-called IHTT-slow TBI group deviated by at least 1.5 standard deviations from data for the healthy control group.

The IHTT-slow TBI group also demonstrated lower CC integrity and poorer neurocognitive functioning than did both the control group and the remaining members of the experimental group. Lower fractional anisotropy (FA) – a common sign of impaired white matter (WM) – and slower IHTTs also predicted poor neurocognitive function.

“When we compared the IHTT-slow TBI group to the healthy control group, we found significant differences in callosal WM integrity, as well as the integrity of the association and projection tract systems tested. Lower FA and higher mean diffusivity (MD) in the IHTT-slow group suggests myelin disruption,” noted Emily L Dennis of the University of Southern California, Marina del Rey, and her colleagues. “When we compared the IHTT-normal TBI group to the healthy control group, we found only a few areas where the TBI group had significantly lower FA and no significant differences in MD [mean diffusivity].”

Read the full study in the Journal of Neuroscience (doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1595-15.2015).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF NEUROSCIENCE

Could Lesion Become a Pain in the Neck?

At the insistence of his wife, a 39-year-old man presents to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his neck that manifested three years ago. As the lesion has grown, darkened, and become more irregular in outline, she has urged him to have it checked. Her efforts finally succeeded when several of his coworkers also commented on it.

The patient has a history of sun exposure but says he tolerates it well and tans easily. He is otherwise healthy.

EXAMINATION

The irregularly pigmented and bordered dark brown macule, located on the lateral aspect of the left side of his neck, measures about 2 cm in its greatest dimension. The rest of his neck shows definite signs of chronic UV overexposure, in the form of poikilodermatous changes.

Dermatoscopic examination of the lesion shows focal areas of pigment streaming and blue veiling—both indicative of melanoma. In light of these findings and in the context of his heavily sun-damaged skin, the patient is scheduled for excision. This is performed one week later; the lesion is removed with 5-mm margins, producing a curved, elliptiform defect to match local skin lines, with a two-layer closure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report showed the lesion to be an early lentigo maligna (LM). Most authorities in the field do not consider this a true melanoma, although it is probably best considered a type of melanoma in situ. LM definitely involves cellular atypia, but at a very superficial level. Only a tiny fraction of LMs ever become invasive—and only after several years of being left in place.

LM isn’t always as obvious as this patient’s lesion is. It can be brown, red, or even bluish and can blend into surrounding mottled skin lesions (eg, solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses or actinic keratosis). The key to diagnosis is to observe for change in size and/or color, especially on sun-exposed areas of skin in older, sun-damaged patients.

In this case, the decision to excise the lesion was made easier by its size and location. Larger lesions of uncertain dimensions may be assessed with multiple punch biopsies.

Once LM is diagnosed, the problem becomes obtaining adequate margins surgically, given the often ill-defined dimensions of the lesion. Failure rates, even when Mohs surgery is performed, are all too high. Surgery has therefore been combined with the application of immune-enhancing creams (eg, imiquimod), a method that shows promise but yields conflicting results in studies.

Since many LMs appear on truly elderly patients, and since their evolution to invasive status is so slow, they don’t command the same urgency as a truly invasive melanoma. Clinically, however, this patient’s lesion met the criteria by which we judge potentially malignant lesions: asymmetry, irregular borders, odd color, and large size. It could easily have been an invasive melanoma, either at the time or in future. Finding and identifying it not only delivered peace of mind but also provided a warning that the patient had some serious sun damage—and therefore the potential to develop other cutaneous malignancies.

Fortunately, a whole-body check revealed no other worrisome lesions. The patient has, however, been scheduled for twice-yearly skin checks. He also received education on the recognition of melanoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• The prognosis for a melanoma is determined by numerous factors, most notably the vertical thickness of the lesion, as measured under the microscope by the examining pathologist.

• The lentigo maligna lesion, as seen in this case, can be so thin and superficial that some experts don’t consider it a true melanoma.

• Nonetheless, the gross appearance of such lesions typifies the main diagnostic features (ABCDs) of melanoma: Asymmetry, odd Borders, odd Colors, and Diameter (large size).

• The finding of an LM means the patient has increased risk for invasive melanoma in the future.

At the insistence of his wife, a 39-year-old man presents to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his neck that manifested three years ago. As the lesion has grown, darkened, and become more irregular in outline, she has urged him to have it checked. Her efforts finally succeeded when several of his coworkers also commented on it.

The patient has a history of sun exposure but says he tolerates it well and tans easily. He is otherwise healthy.

EXAMINATION

The irregularly pigmented and bordered dark brown macule, located on the lateral aspect of the left side of his neck, measures about 2 cm in its greatest dimension. The rest of his neck shows definite signs of chronic UV overexposure, in the form of poikilodermatous changes.

Dermatoscopic examination of the lesion shows focal areas of pigment streaming and blue veiling—both indicative of melanoma. In light of these findings and in the context of his heavily sun-damaged skin, the patient is scheduled for excision. This is performed one week later; the lesion is removed with 5-mm margins, producing a curved, elliptiform defect to match local skin lines, with a two-layer closure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report showed the lesion to be an early lentigo maligna (LM). Most authorities in the field do not consider this a true melanoma, although it is probably best considered a type of melanoma in situ. LM definitely involves cellular atypia, but at a very superficial level. Only a tiny fraction of LMs ever become invasive—and only after several years of being left in place.

LM isn’t always as obvious as this patient’s lesion is. It can be brown, red, or even bluish and can blend into surrounding mottled skin lesions (eg, solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses or actinic keratosis). The key to diagnosis is to observe for change in size and/or color, especially on sun-exposed areas of skin in older, sun-damaged patients.

In this case, the decision to excise the lesion was made easier by its size and location. Larger lesions of uncertain dimensions may be assessed with multiple punch biopsies.

Once LM is diagnosed, the problem becomes obtaining adequate margins surgically, given the often ill-defined dimensions of the lesion. Failure rates, even when Mohs surgery is performed, are all too high. Surgery has therefore been combined with the application of immune-enhancing creams (eg, imiquimod), a method that shows promise but yields conflicting results in studies.

Since many LMs appear on truly elderly patients, and since their evolution to invasive status is so slow, they don’t command the same urgency as a truly invasive melanoma. Clinically, however, this patient’s lesion met the criteria by which we judge potentially malignant lesions: asymmetry, irregular borders, odd color, and large size. It could easily have been an invasive melanoma, either at the time or in future. Finding and identifying it not only delivered peace of mind but also provided a warning that the patient had some serious sun damage—and therefore the potential to develop other cutaneous malignancies.

Fortunately, a whole-body check revealed no other worrisome lesions. The patient has, however, been scheduled for twice-yearly skin checks. He also received education on the recognition of melanoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• The prognosis for a melanoma is determined by numerous factors, most notably the vertical thickness of the lesion, as measured under the microscope by the examining pathologist.

• The lentigo maligna lesion, as seen in this case, can be so thin and superficial that some experts don’t consider it a true melanoma.

• Nonetheless, the gross appearance of such lesions typifies the main diagnostic features (ABCDs) of melanoma: Asymmetry, odd Borders, odd Colors, and Diameter (large size).

• The finding of an LM means the patient has increased risk for invasive melanoma in the future.

At the insistence of his wife, a 39-year-old man presents to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his neck that manifested three years ago. As the lesion has grown, darkened, and become more irregular in outline, she has urged him to have it checked. Her efforts finally succeeded when several of his coworkers also commented on it.

The patient has a history of sun exposure but says he tolerates it well and tans easily. He is otherwise healthy.

EXAMINATION

The irregularly pigmented and bordered dark brown macule, located on the lateral aspect of the left side of his neck, measures about 2 cm in its greatest dimension. The rest of his neck shows definite signs of chronic UV overexposure, in the form of poikilodermatous changes.

Dermatoscopic examination of the lesion shows focal areas of pigment streaming and blue veiling—both indicative of melanoma. In light of these findings and in the context of his heavily sun-damaged skin, the patient is scheduled for excision. This is performed one week later; the lesion is removed with 5-mm margins, producing a curved, elliptiform defect to match local skin lines, with a two-layer closure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report showed the lesion to be an early lentigo maligna (LM). Most authorities in the field do not consider this a true melanoma, although it is probably best considered a type of melanoma in situ. LM definitely involves cellular atypia, but at a very superficial level. Only a tiny fraction of LMs ever become invasive—and only after several years of being left in place.

LM isn’t always as obvious as this patient’s lesion is. It can be brown, red, or even bluish and can blend into surrounding mottled skin lesions (eg, solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses or actinic keratosis). The key to diagnosis is to observe for change in size and/or color, especially on sun-exposed areas of skin in older, sun-damaged patients.

In this case, the decision to excise the lesion was made easier by its size and location. Larger lesions of uncertain dimensions may be assessed with multiple punch biopsies.

Once LM is diagnosed, the problem becomes obtaining adequate margins surgically, given the often ill-defined dimensions of the lesion. Failure rates, even when Mohs surgery is performed, are all too high. Surgery has therefore been combined with the application of immune-enhancing creams (eg, imiquimod), a method that shows promise but yields conflicting results in studies.

Since many LMs appear on truly elderly patients, and since their evolution to invasive status is so slow, they don’t command the same urgency as a truly invasive melanoma. Clinically, however, this patient’s lesion met the criteria by which we judge potentially malignant lesions: asymmetry, irregular borders, odd color, and large size. It could easily have been an invasive melanoma, either at the time or in future. Finding and identifying it not only delivered peace of mind but also provided a warning that the patient had some serious sun damage—and therefore the potential to develop other cutaneous malignancies.

Fortunately, a whole-body check revealed no other worrisome lesions. The patient has, however, been scheduled for twice-yearly skin checks. He also received education on the recognition of melanoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• The prognosis for a melanoma is determined by numerous factors, most notably the vertical thickness of the lesion, as measured under the microscope by the examining pathologist.

• The lentigo maligna lesion, as seen in this case, can be so thin and superficial that some experts don’t consider it a true melanoma.

• Nonetheless, the gross appearance of such lesions typifies the main diagnostic features (ABCDs) of melanoma: Asymmetry, odd Borders, odd Colors, and Diameter (large size).

• The finding of an LM means the patient has increased risk for invasive melanoma in the future.

Cold iron truth: The high value quotient of dermatology

I have been a traveling road show for the last 2 years, explaining the value of dermatology to insurers. It is amazing how poorly understood we are by payers.

Let me give you an example. Currently, dermatologists treat about 70% of all skin cancers. This is up from the 10% we treated 30 years ago, but if you think about it, it should be 98% or 99%. There were 5.4 million skin cancers in the United States in 2012. The great majority were nonmelanoma skin cancers (at an interesting ratio of 1:1 for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma), and only about 75,000 were melanomas. About 80% of all melanomas are less than 1 mm in thickness and undoubtedly appropriate for local excision in the office. Dermatologists treat these skin cancers at less than 1/5 the cost of treatment in a facility. We, and a few primary care physicians, are the only physicians who are not operating room dependent. We can remove these cancers under local anesthesia in the office, without an anesthesiologist, multiple nurses, intravenous lines, preop labs, and the other high fixed costs associated with a hospital procedure, and we can do it promptly. Insurers should be pounding their drums to demand that the vast majority of skin cancers be treated in the office setting, rather than in a hospital. Maybe all skin cancer patients should be required to get “precertified” by a dermatologist before they are sent to a hospital for a procedure. This would improve quality and greatly cut costs.

Insurers always drop their jaws when I explain this to them. They have never matched up the costs of the physicians and the costs of the facilities where procedures are performed. They need to consider the value of the dermatologist in providing an accurate, quick diagnosis, with immediate exclusion of benign lesions and elimination of the long wait times to get a cancer removed. It costs less to get a skin cancer diagnosed and removed by a dermatologist than to get a new set of car tires installed, and we can often do it in about the same amount of time. Compare that with $150,000 spent annually to treat metastatic melanoma.

In addition, fewer dermatologists mean longer wait times to see the dermatologist, causing what I call the “spillover” effect. When patients cannot get in to see the dermatologist, they call their primary care physician, who sends them down to the hospital to see their general surgeon on lumps and bumps day. Everything gets removed, benign or not, in the hospital outpatient department.

That is why it is insane for insurers to be eliminating dermatologists wholesale from their “tight” networks. Their software tells them they will save money in the short term, but they won’t because of the spillover, and it is very foolish in the long term. With the advent of the Affordable Care Act, patients cannot be excluded for preexisting conditions, and these patients all become long-term clients of one insurer or another. What is neglected today becomes a nightmare tomorrow. Dermatology offers an extraordinarily high value quotient, but only if insurers have enough sense to let the patients see us.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati. Email him at [email protected].

I have been a traveling road show for the last 2 years, explaining the value of dermatology to insurers. It is amazing how poorly understood we are by payers.

Let me give you an example. Currently, dermatologists treat about 70% of all skin cancers. This is up from the 10% we treated 30 years ago, but if you think about it, it should be 98% or 99%. There were 5.4 million skin cancers in the United States in 2012. The great majority were nonmelanoma skin cancers (at an interesting ratio of 1:1 for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma), and only about 75,000 were melanomas. About 80% of all melanomas are less than 1 mm in thickness and undoubtedly appropriate for local excision in the office. Dermatologists treat these skin cancers at less than 1/5 the cost of treatment in a facility. We, and a few primary care physicians, are the only physicians who are not operating room dependent. We can remove these cancers under local anesthesia in the office, without an anesthesiologist, multiple nurses, intravenous lines, preop labs, and the other high fixed costs associated with a hospital procedure, and we can do it promptly. Insurers should be pounding their drums to demand that the vast majority of skin cancers be treated in the office setting, rather than in a hospital. Maybe all skin cancer patients should be required to get “precertified” by a dermatologist before they are sent to a hospital for a procedure. This would improve quality and greatly cut costs.

Insurers always drop their jaws when I explain this to them. They have never matched up the costs of the physicians and the costs of the facilities where procedures are performed. They need to consider the value of the dermatologist in providing an accurate, quick diagnosis, with immediate exclusion of benign lesions and elimination of the long wait times to get a cancer removed. It costs less to get a skin cancer diagnosed and removed by a dermatologist than to get a new set of car tires installed, and we can often do it in about the same amount of time. Compare that with $150,000 spent annually to treat metastatic melanoma.

In addition, fewer dermatologists mean longer wait times to see the dermatologist, causing what I call the “spillover” effect. When patients cannot get in to see the dermatologist, they call their primary care physician, who sends them down to the hospital to see their general surgeon on lumps and bumps day. Everything gets removed, benign or not, in the hospital outpatient department.

That is why it is insane for insurers to be eliminating dermatologists wholesale from their “tight” networks. Their software tells them they will save money in the short term, but they won’t because of the spillover, and it is very foolish in the long term. With the advent of the Affordable Care Act, patients cannot be excluded for preexisting conditions, and these patients all become long-term clients of one insurer or another. What is neglected today becomes a nightmare tomorrow. Dermatology offers an extraordinarily high value quotient, but only if insurers have enough sense to let the patients see us.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati. Email him at [email protected].

I have been a traveling road show for the last 2 years, explaining the value of dermatology to insurers. It is amazing how poorly understood we are by payers.

Let me give you an example. Currently, dermatologists treat about 70% of all skin cancers. This is up from the 10% we treated 30 years ago, but if you think about it, it should be 98% or 99%. There were 5.4 million skin cancers in the United States in 2012. The great majority were nonmelanoma skin cancers (at an interesting ratio of 1:1 for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma), and only about 75,000 were melanomas. About 80% of all melanomas are less than 1 mm in thickness and undoubtedly appropriate for local excision in the office. Dermatologists treat these skin cancers at less than 1/5 the cost of treatment in a facility. We, and a few primary care physicians, are the only physicians who are not operating room dependent. We can remove these cancers under local anesthesia in the office, without an anesthesiologist, multiple nurses, intravenous lines, preop labs, and the other high fixed costs associated with a hospital procedure, and we can do it promptly. Insurers should be pounding their drums to demand that the vast majority of skin cancers be treated in the office setting, rather than in a hospital. Maybe all skin cancer patients should be required to get “precertified” by a dermatologist before they are sent to a hospital for a procedure. This would improve quality and greatly cut costs.

Insurers always drop their jaws when I explain this to them. They have never matched up the costs of the physicians and the costs of the facilities where procedures are performed. They need to consider the value of the dermatologist in providing an accurate, quick diagnosis, with immediate exclusion of benign lesions and elimination of the long wait times to get a cancer removed. It costs less to get a skin cancer diagnosed and removed by a dermatologist than to get a new set of car tires installed, and we can often do it in about the same amount of time. Compare that with $150,000 spent annually to treat metastatic melanoma.

In addition, fewer dermatologists mean longer wait times to see the dermatologist, causing what I call the “spillover” effect. When patients cannot get in to see the dermatologist, they call their primary care physician, who sends them down to the hospital to see their general surgeon on lumps and bumps day. Everything gets removed, benign or not, in the hospital outpatient department.

That is why it is insane for insurers to be eliminating dermatologists wholesale from their “tight” networks. Their software tells them they will save money in the short term, but they won’t because of the spillover, and it is very foolish in the long term. With the advent of the Affordable Care Act, patients cannot be excluded for preexisting conditions, and these patients all become long-term clients of one insurer or another. What is neglected today becomes a nightmare tomorrow. Dermatology offers an extraordinarily high value quotient, but only if insurers have enough sense to let the patients see us.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati. Email him at [email protected].

Rivaroxaban safe, effective after ED admission

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Patients admitted to the emergency department (ED) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) can be placed on oral anticoagulation and discharged immediately, according to research published in Academic Emergency Medicine.

The study showed that patients who received anticoagulation with rivaroxaban, were discharged from the ED right away, and did not undergo weekly monitoring had a low rate of VTE recurrence and major or clinically relevant bleeding.

A related study suggested this approach was less costly than standard treatment with heparin and warfarin.

The prospect of being able to send patients home from the ED on the day of admission is a quality of life issue, according to Jeffrey A. Kline, MD, a professor at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis and an author of both studies.

“We really do empower the patient more with [rivaroxaban],” he said. “Patients say treatment with no injections is a much better option. [Rivaroxaban] takes a condition that is life-threatening and makes it something the patient can control.”

Safety and efficacy

For the first study, Dr Kline and his colleagues evaluated 106 low-risk patients who were diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) at 2 metropolitan EDs.

The patients were admitted between March 2013 and April 2014. Seventy-one patients had DVT, 30 had PE, and 5 had both.

The standard of care for these patients is heparin injections, followed by oral warfarin and close monitoring to ensure safe dosage levels.

But patients in this study received rivaroxaban, which does not require blood monitoring, and were released from the hospital on the day of admission. The patients did undergo follow up-monitoring at 2 weeks, 5 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months.

The researchers followed patients for a mean of 389 days (range, 213 to 594 days). None of the patients had a VTE recurrence, major bleeding, or clinically relevant bleeding while on therapy.

However, 3 patients (2.8%) experienced DVT recurrence within a year of stopping treatment. All 3 had completed their prescribed treatment.

“This study is about giving patients a new option,” Dr Kline said. “Treating patients at home for blood clots was found to have fewer errors than the standard of care and better outcomes. Patients [receiving standard therapy] have to be taught to give themselves injections, and it scares them to death. Almost everyone has taken a pill, so there is no learning curve for patients [with rivaroxaban].”

Treatment costs

In the second study, Dr Kline and his colleagues compared costs associated with standard treatment and rivaroxaban. Total hospital charges with the rivaroxaban protocol were about half the cost of charges for standard therapy.

The researchers evaluated 97 patients, matching them for age, sex, and the severity of their illness. At 6 months after ED admission, the median cost was $4787 (interquartile range=$3042 to $7596) for the rivaroxaban group and $11,128 (interquartile range=$8110 to $23,390) for the group treated with standard care (P<0.001).

Among patients with PE, costs were 57% lower in the rivaroxaban group than the standard therapy group (P<0.001). For patients with DVT, costs were 56% lower in the rivaroxaban group (P=0.003). ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Patients admitted to the emergency department (ED) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) can be placed on oral anticoagulation and discharged immediately, according to research published in Academic Emergency Medicine.

The study showed that patients who received anticoagulation with rivaroxaban, were discharged from the ED right away, and did not undergo weekly monitoring had a low rate of VTE recurrence and major or clinically relevant bleeding.

A related study suggested this approach was less costly than standard treatment with heparin and warfarin.

The prospect of being able to send patients home from the ED on the day of admission is a quality of life issue, according to Jeffrey A. Kline, MD, a professor at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis and an author of both studies.

“We really do empower the patient more with [rivaroxaban],” he said. “Patients say treatment with no injections is a much better option. [Rivaroxaban] takes a condition that is life-threatening and makes it something the patient can control.”

Safety and efficacy

For the first study, Dr Kline and his colleagues evaluated 106 low-risk patients who were diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) at 2 metropolitan EDs.

The patients were admitted between March 2013 and April 2014. Seventy-one patients had DVT, 30 had PE, and 5 had both.

The standard of care for these patients is heparin injections, followed by oral warfarin and close monitoring to ensure safe dosage levels.

But patients in this study received rivaroxaban, which does not require blood monitoring, and were released from the hospital on the day of admission. The patients did undergo follow up-monitoring at 2 weeks, 5 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months.

The researchers followed patients for a mean of 389 days (range, 213 to 594 days). None of the patients had a VTE recurrence, major bleeding, or clinically relevant bleeding while on therapy.

However, 3 patients (2.8%) experienced DVT recurrence within a year of stopping treatment. All 3 had completed their prescribed treatment.

“This study is about giving patients a new option,” Dr Kline said. “Treating patients at home for blood clots was found to have fewer errors than the standard of care and better outcomes. Patients [receiving standard therapy] have to be taught to give themselves injections, and it scares them to death. Almost everyone has taken a pill, so there is no learning curve for patients [with rivaroxaban].”

Treatment costs

In the second study, Dr Kline and his colleagues compared costs associated with standard treatment and rivaroxaban. Total hospital charges with the rivaroxaban protocol were about half the cost of charges for standard therapy.

The researchers evaluated 97 patients, matching them for age, sex, and the severity of their illness. At 6 months after ED admission, the median cost was $4787 (interquartile range=$3042 to $7596) for the rivaroxaban group and $11,128 (interquartile range=$8110 to $23,390) for the group treated with standard care (P<0.001).

Among patients with PE, costs were 57% lower in the rivaroxaban group than the standard therapy group (P<0.001). For patients with DVT, costs were 56% lower in the rivaroxaban group (P=0.003). ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Patients admitted to the emergency department (ED) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) can be placed on oral anticoagulation and discharged immediately, according to research published in Academic Emergency Medicine.

The study showed that patients who received anticoagulation with rivaroxaban, were discharged from the ED right away, and did not undergo weekly monitoring had a low rate of VTE recurrence and major or clinically relevant bleeding.

A related study suggested this approach was less costly than standard treatment with heparin and warfarin.

The prospect of being able to send patients home from the ED on the day of admission is a quality of life issue, according to Jeffrey A. Kline, MD, a professor at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis and an author of both studies.

“We really do empower the patient more with [rivaroxaban],” he said. “Patients say treatment with no injections is a much better option. [Rivaroxaban] takes a condition that is life-threatening and makes it something the patient can control.”

Safety and efficacy

For the first study, Dr Kline and his colleagues evaluated 106 low-risk patients who were diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) at 2 metropolitan EDs.

The patients were admitted between March 2013 and April 2014. Seventy-one patients had DVT, 30 had PE, and 5 had both.

The standard of care for these patients is heparin injections, followed by oral warfarin and close monitoring to ensure safe dosage levels.

But patients in this study received rivaroxaban, which does not require blood monitoring, and were released from the hospital on the day of admission. The patients did undergo follow up-monitoring at 2 weeks, 5 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months.

The researchers followed patients for a mean of 389 days (range, 213 to 594 days). None of the patients had a VTE recurrence, major bleeding, or clinically relevant bleeding while on therapy.

However, 3 patients (2.8%) experienced DVT recurrence within a year of stopping treatment. All 3 had completed their prescribed treatment.

“This study is about giving patients a new option,” Dr Kline said. “Treating patients at home for blood clots was found to have fewer errors than the standard of care and better outcomes. Patients [receiving standard therapy] have to be taught to give themselves injections, and it scares them to death. Almost everyone has taken a pill, so there is no learning curve for patients [with rivaroxaban].”

Treatment costs

In the second study, Dr Kline and his colleagues compared costs associated with standard treatment and rivaroxaban. Total hospital charges with the rivaroxaban protocol were about half the cost of charges for standard therapy.

The researchers evaluated 97 patients, matching them for age, sex, and the severity of their illness. At 6 months after ED admission, the median cost was $4787 (interquartile range=$3042 to $7596) for the rivaroxaban group and $11,128 (interquartile range=$8110 to $23,390) for the group treated with standard care (P<0.001).

Among patients with PE, costs were 57% lower in the rivaroxaban group than the standard therapy group (P<0.001). For patients with DVT, costs were 56% lower in the rivaroxaban group (P=0.003). ![]()

Polyphenols may enhance doxorubicin treatment

Photo by Rhoda Baer

New research suggests the polyphenols resveratrol and quercetin could be used to augment treatment with the anthracycline doxorubicin.

Investigators found they could increase the bioavailability of resveratrol and quercetin using copolymers that make the compounds water soluble and allow for their injection into the blood stream.

The team then showed the compounds synergize with doxorubicin while also reducing cardiac toxicity.

Although doxorubicin has proven effective against lymphomas, leukemias, and other cancers, the drug can only be used for a limited time because it confers cardiotoxicity.

The co-administration of resveratrol and quercetin might allow for much more extensive use of doxorubicin, while at the same time improving its efficacy and demonstrating the polyphenols’ own anticancer properties, investigators said.

They described research supporting this idea in the Journal of Controlled Release.

“This has great potential to improve chemotherapeutic cancer treatment,” said Adam Alani, PhD, of Oregon State University in Portland.

“The co-administration of high levels of resveratrol and quercetin, in both in vitro and in vivo studies, shows that it significantly reduces the cardiac toxicity of [doxorubicin]. And these compounds have a synergistic effect that enhances the efficacy of the cancer drug, by sensitizing the cancer cells to the effects of the drug.”

Dr Alani said further research may demonstrate that these compounds can completely eliminate the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin, as they scavenge the toxic free radicals produced by this drug.

It’s also possible, he said, that administration of these natural polyphenols could have value in cancer therapy by themselves or in combination with a wider range of other chemotherapeutic drugs.

Increasing bioavailability

Resveratrol is a natural compound found in foods such as grapes, red wine, green tea, berries, and dark chocolate. Quercetin reaches some of its highest natural levels in capers, some berries, and leafy greens.

When consumed via food or taken as supplements, these polyphenol compounds reach only a tiny fraction of the level that’s possible with direct injection. Such injection was not possible until Dr Alani and his colleagues adapted the use of polymeric micelles.

Specifically, the investigators combined resveratrol and quercetin in Pluronic F127 micelles (mRQ). Pluronics are triblock copolymers consisting of a polypropylene oxide chain flanked with 2 polyethylene oxide chains that can self-assemble into polymeric micelles. The micelles have hydrophobic cores that help solubilize compounds with poor aqueous solubility.

“There are several advantages with this system,” Dr Alani said. “We can finally reach clinical levels of these polyphenols in the body. We can load both the compounds at one time to help control the cardiotoxicity of the cancer drug, and we can help the polyphenols accumulate in cancer cells where they have their own anticancer properties.”

In combination with doxorubicin

The investigators prepared mRQ micelles that were capable of retaining 1.1 mg/mL of resveratrol and 1.42 mg/mL of quercetin. They then tested mRQ in combination with doxorubicin in human ovarian cancer cells (SKOV-3) and rat cardiomyocytes (H9C2).

The team found that a resveratrol-quercetin-doxorubicin ratio of 10:10:1 was synergistic in SKOV-3 cells and antagonistic in H9C2 cells.

mRQ did not interfere with doxorubicin’s caspase activity in SKOV-3 cells but significantly decreased the activity in H9C2 cells. Likewise, there were no changes in the generation of reactive oxygen species in SKOV-3 cells, but there was significant scavenging in H9C2 cells.

The investigators also administered doxorubicin, with or without mRQ, to healthy mice and found that mRQ “conferred full cardioprotection.”

Dr Alani noted that previous research suggested resveratrol and quercetin are safe when given at high concentrations, but additional research is needed. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

New research suggests the polyphenols resveratrol and quercetin could be used to augment treatment with the anthracycline doxorubicin.

Investigators found they could increase the bioavailability of resveratrol and quercetin using copolymers that make the compounds water soluble and allow for their injection into the blood stream.

The team then showed the compounds synergize with doxorubicin while also reducing cardiac toxicity.

Although doxorubicin has proven effective against lymphomas, leukemias, and other cancers, the drug can only be used for a limited time because it confers cardiotoxicity.

The co-administration of resveratrol and quercetin might allow for much more extensive use of doxorubicin, while at the same time improving its efficacy and demonstrating the polyphenols’ own anticancer properties, investigators said.

They described research supporting this idea in the Journal of Controlled Release.

“This has great potential to improve chemotherapeutic cancer treatment,” said Adam Alani, PhD, of Oregon State University in Portland.

“The co-administration of high levels of resveratrol and quercetin, in both in vitro and in vivo studies, shows that it significantly reduces the cardiac toxicity of [doxorubicin]. And these compounds have a synergistic effect that enhances the efficacy of the cancer drug, by sensitizing the cancer cells to the effects of the drug.”

Dr Alani said further research may demonstrate that these compounds can completely eliminate the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin, as they scavenge the toxic free radicals produced by this drug.

It’s also possible, he said, that administration of these natural polyphenols could have value in cancer therapy by themselves or in combination with a wider range of other chemotherapeutic drugs.

Increasing bioavailability

Resveratrol is a natural compound found in foods such as grapes, red wine, green tea, berries, and dark chocolate. Quercetin reaches some of its highest natural levels in capers, some berries, and leafy greens.

When consumed via food or taken as supplements, these polyphenol compounds reach only a tiny fraction of the level that’s possible with direct injection. Such injection was not possible until Dr Alani and his colleagues adapted the use of polymeric micelles.

Specifically, the investigators combined resveratrol and quercetin in Pluronic F127 micelles (mRQ). Pluronics are triblock copolymers consisting of a polypropylene oxide chain flanked with 2 polyethylene oxide chains that can self-assemble into polymeric micelles. The micelles have hydrophobic cores that help solubilize compounds with poor aqueous solubility.

“There are several advantages with this system,” Dr Alani said. “We can finally reach clinical levels of these polyphenols in the body. We can load both the compounds at one time to help control the cardiotoxicity of the cancer drug, and we can help the polyphenols accumulate in cancer cells where they have their own anticancer properties.”

In combination with doxorubicin

The investigators prepared mRQ micelles that were capable of retaining 1.1 mg/mL of resveratrol and 1.42 mg/mL of quercetin. They then tested mRQ in combination with doxorubicin in human ovarian cancer cells (SKOV-3) and rat cardiomyocytes (H9C2).

The team found that a resveratrol-quercetin-doxorubicin ratio of 10:10:1 was synergistic in SKOV-3 cells and antagonistic in H9C2 cells.

mRQ did not interfere with doxorubicin’s caspase activity in SKOV-3 cells but significantly decreased the activity in H9C2 cells. Likewise, there were no changes in the generation of reactive oxygen species in SKOV-3 cells, but there was significant scavenging in H9C2 cells.

The investigators also administered doxorubicin, with or without mRQ, to healthy mice and found that mRQ “conferred full cardioprotection.”

Dr Alani noted that previous research suggested resveratrol and quercetin are safe when given at high concentrations, but additional research is needed. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

New research suggests the polyphenols resveratrol and quercetin could be used to augment treatment with the anthracycline doxorubicin.

Investigators found they could increase the bioavailability of resveratrol and quercetin using copolymers that make the compounds water soluble and allow for their injection into the blood stream.

The team then showed the compounds synergize with doxorubicin while also reducing cardiac toxicity.

Although doxorubicin has proven effective against lymphomas, leukemias, and other cancers, the drug can only be used for a limited time because it confers cardiotoxicity.

The co-administration of resveratrol and quercetin might allow for much more extensive use of doxorubicin, while at the same time improving its efficacy and demonstrating the polyphenols’ own anticancer properties, investigators said.

They described research supporting this idea in the Journal of Controlled Release.

“This has great potential to improve chemotherapeutic cancer treatment,” said Adam Alani, PhD, of Oregon State University in Portland.

“The co-administration of high levels of resveratrol and quercetin, in both in vitro and in vivo studies, shows that it significantly reduces the cardiac toxicity of [doxorubicin]. And these compounds have a synergistic effect that enhances the efficacy of the cancer drug, by sensitizing the cancer cells to the effects of the drug.”

Dr Alani said further research may demonstrate that these compounds can completely eliminate the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin, as they scavenge the toxic free radicals produced by this drug.

It’s also possible, he said, that administration of these natural polyphenols could have value in cancer therapy by themselves or in combination with a wider range of other chemotherapeutic drugs.

Increasing bioavailability

Resveratrol is a natural compound found in foods such as grapes, red wine, green tea, berries, and dark chocolate. Quercetin reaches some of its highest natural levels in capers, some berries, and leafy greens.

When consumed via food or taken as supplements, these polyphenol compounds reach only a tiny fraction of the level that’s possible with direct injection. Such injection was not possible until Dr Alani and his colleagues adapted the use of polymeric micelles.

Specifically, the investigators combined resveratrol and quercetin in Pluronic F127 micelles (mRQ). Pluronics are triblock copolymers consisting of a polypropylene oxide chain flanked with 2 polyethylene oxide chains that can self-assemble into polymeric micelles. The micelles have hydrophobic cores that help solubilize compounds with poor aqueous solubility.

“There are several advantages with this system,” Dr Alani said. “We can finally reach clinical levels of these polyphenols in the body. We can load both the compounds at one time to help control the cardiotoxicity of the cancer drug, and we can help the polyphenols accumulate in cancer cells where they have their own anticancer properties.”

In combination with doxorubicin