User login

American Psychological Association investigation proves value of dissent

In 2005, the American Psychological Association formed a task force to address the role of psychologists in the interrogation of Central Intelligence Agency and Department of Defense detainees. The task force was formed at the request of psychologists consulting with both entities and their supervisors to address the ethics of psychologist involvement in shaping interrogation practices. The task force concluded that psychologist participation was allowed in order to ensure that the process was “safe, legal, ethical, and effective.” The Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security (PENS) report drew immediate objection from within the organization and triggered a member-initiated movement to rescind the findings. Members alleged that those involved in the creation of the PENS report had conflicts of interest and that the task force was heavily weighted with psychologists who were already consulting with national security organizations.

These concerns were substantiated in a book entitled Pay Any Price: Greed, Power, and Endless War (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014) by New York Times reporter James Risen. In the spirit of the Watergate investigation, Risen “followed the money” as it flowed from the U.S. government to national security and defense agencies, and into the pockets of select psychologists who took active roles in harsh interrogation techniques.

Armed with this new evidence, the American Psychological Association initiated an independent investigation of the association’s role in November 2014. The results of that investigation were published recently in a 542-page report synopsized by James Risen in the New York Times. Also known as the Hoffman report, it confirmed numerous conflicts of interest between psychologists involved in the 2005 revision of the ethics guidelines, and both the C.I.A. and the D.O.D. The full implications of the Hoffman report remain to be seen, but the history and process of this problem are informative.

Both the American Medical Association and the American Psychiatric Association have position statements against participation in interrogation and torture. In 2006, the American Psychiatric Association issued a position statement in which it held that “that psychiatrists should not participate in, or otherwise assist or facilitate, the commission of torture of any person.” The American Medical Association similarly codified a prohibition against participation in interrogation in its ethical guidelines: “Physicians must oppose and must not participate in torture for any reason. Participation in torture includes, but is not limited to, providing or withholding any services, substances, or knowledge to facilitate the practice of torture. Physicians must not be present when torture is used or threatened.” Members who become aware of the practices are called upon to report them and to adhere to professional ethical standards.

But before psychiatry congratulates itself for its moral fortitude, we would do well to remember that the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of University Programs awarded $39 million to 12 academic institutions in 2011, to create “centers of excellence” related to cybersecurity, counterintelligence measures, disaster preparedness, prevention of terrorism, and research into the sociologic and psychological causes of radicalization. All mental health professionals should ensure that any research-related national security issues abide by international, ethical, and humanitarian standards, and should refrain from areas of investigation that target vulnerable individuals or groups.

The Hoffman report reminds us that everything that is legal is not necessarily ethical. It highlights the necessity of bright line standards over issues related to essential human rights and well-being. For these concerns, we should value internal challenge and dissent, and we must continually ask ourselves if we are on the right path. We must also create and protect avenues for our members who discover and report violations, even if this protection is given to the detriment of our organization. The purpose of a professional organization is to ensure the quality and integrity of its members and to protect the public from those members who fall short in either domain. As professionals, we are each responsible for ensuring that our organization carries out these duties.

Dr. Hanson is a forensic psychiatrist and coauthor of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

In 2005, the American Psychological Association formed a task force to address the role of psychologists in the interrogation of Central Intelligence Agency and Department of Defense detainees. The task force was formed at the request of psychologists consulting with both entities and their supervisors to address the ethics of psychologist involvement in shaping interrogation practices. The task force concluded that psychologist participation was allowed in order to ensure that the process was “safe, legal, ethical, and effective.” The Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security (PENS) report drew immediate objection from within the organization and triggered a member-initiated movement to rescind the findings. Members alleged that those involved in the creation of the PENS report had conflicts of interest and that the task force was heavily weighted with psychologists who were already consulting with national security organizations.

These concerns were substantiated in a book entitled Pay Any Price: Greed, Power, and Endless War (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014) by New York Times reporter James Risen. In the spirit of the Watergate investigation, Risen “followed the money” as it flowed from the U.S. government to national security and defense agencies, and into the pockets of select psychologists who took active roles in harsh interrogation techniques.

Armed with this new evidence, the American Psychological Association initiated an independent investigation of the association’s role in November 2014. The results of that investigation were published recently in a 542-page report synopsized by James Risen in the New York Times. Also known as the Hoffman report, it confirmed numerous conflicts of interest between psychologists involved in the 2005 revision of the ethics guidelines, and both the C.I.A. and the D.O.D. The full implications of the Hoffman report remain to be seen, but the history and process of this problem are informative.

Both the American Medical Association and the American Psychiatric Association have position statements against participation in interrogation and torture. In 2006, the American Psychiatric Association issued a position statement in which it held that “that psychiatrists should not participate in, or otherwise assist or facilitate, the commission of torture of any person.” The American Medical Association similarly codified a prohibition against participation in interrogation in its ethical guidelines: “Physicians must oppose and must not participate in torture for any reason. Participation in torture includes, but is not limited to, providing or withholding any services, substances, or knowledge to facilitate the practice of torture. Physicians must not be present when torture is used or threatened.” Members who become aware of the practices are called upon to report them and to adhere to professional ethical standards.

But before psychiatry congratulates itself for its moral fortitude, we would do well to remember that the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of University Programs awarded $39 million to 12 academic institutions in 2011, to create “centers of excellence” related to cybersecurity, counterintelligence measures, disaster preparedness, prevention of terrorism, and research into the sociologic and psychological causes of radicalization. All mental health professionals should ensure that any research-related national security issues abide by international, ethical, and humanitarian standards, and should refrain from areas of investigation that target vulnerable individuals or groups.

The Hoffman report reminds us that everything that is legal is not necessarily ethical. It highlights the necessity of bright line standards over issues related to essential human rights and well-being. For these concerns, we should value internal challenge and dissent, and we must continually ask ourselves if we are on the right path. We must also create and protect avenues for our members who discover and report violations, even if this protection is given to the detriment of our organization. The purpose of a professional organization is to ensure the quality and integrity of its members and to protect the public from those members who fall short in either domain. As professionals, we are each responsible for ensuring that our organization carries out these duties.

Dr. Hanson is a forensic psychiatrist and coauthor of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

In 2005, the American Psychological Association formed a task force to address the role of psychologists in the interrogation of Central Intelligence Agency and Department of Defense detainees. The task force was formed at the request of psychologists consulting with both entities and their supervisors to address the ethics of psychologist involvement in shaping interrogation practices. The task force concluded that psychologist participation was allowed in order to ensure that the process was “safe, legal, ethical, and effective.” The Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security (PENS) report drew immediate objection from within the organization and triggered a member-initiated movement to rescind the findings. Members alleged that those involved in the creation of the PENS report had conflicts of interest and that the task force was heavily weighted with psychologists who were already consulting with national security organizations.

These concerns were substantiated in a book entitled Pay Any Price: Greed, Power, and Endless War (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014) by New York Times reporter James Risen. In the spirit of the Watergate investigation, Risen “followed the money” as it flowed from the U.S. government to national security and defense agencies, and into the pockets of select psychologists who took active roles in harsh interrogation techniques.

Armed with this new evidence, the American Psychological Association initiated an independent investigation of the association’s role in November 2014. The results of that investigation were published recently in a 542-page report synopsized by James Risen in the New York Times. Also known as the Hoffman report, it confirmed numerous conflicts of interest between psychologists involved in the 2005 revision of the ethics guidelines, and both the C.I.A. and the D.O.D. The full implications of the Hoffman report remain to be seen, but the history and process of this problem are informative.

Both the American Medical Association and the American Psychiatric Association have position statements against participation in interrogation and torture. In 2006, the American Psychiatric Association issued a position statement in which it held that “that psychiatrists should not participate in, or otherwise assist or facilitate, the commission of torture of any person.” The American Medical Association similarly codified a prohibition against participation in interrogation in its ethical guidelines: “Physicians must oppose and must not participate in torture for any reason. Participation in torture includes, but is not limited to, providing or withholding any services, substances, or knowledge to facilitate the practice of torture. Physicians must not be present when torture is used or threatened.” Members who become aware of the practices are called upon to report them and to adhere to professional ethical standards.

But before psychiatry congratulates itself for its moral fortitude, we would do well to remember that the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of University Programs awarded $39 million to 12 academic institutions in 2011, to create “centers of excellence” related to cybersecurity, counterintelligence measures, disaster preparedness, prevention of terrorism, and research into the sociologic and psychological causes of radicalization. All mental health professionals should ensure that any research-related national security issues abide by international, ethical, and humanitarian standards, and should refrain from areas of investigation that target vulnerable individuals or groups.

The Hoffman report reminds us that everything that is legal is not necessarily ethical. It highlights the necessity of bright line standards over issues related to essential human rights and well-being. For these concerns, we should value internal challenge and dissent, and we must continually ask ourselves if we are on the right path. We must also create and protect avenues for our members who discover and report violations, even if this protection is given to the detriment of our organization. The purpose of a professional organization is to ensure the quality and integrity of its members and to protect the public from those members who fall short in either domain. As professionals, we are each responsible for ensuring that our organization carries out these duties.

Dr. Hanson is a forensic psychiatrist and coauthor of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

Clustered Vesicles in a Blaschkoid Pattern

The Diagnosis: Linear Vesiculobullous Keratosis Follicularis (Darier Disease)

Darier disease (DD), or keratosis follicularis, is typically an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by greasy hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into warty plaques with a predilection for seborrheic areas. The lesions usually are pruritic; malodorous; and may be exacerbated by sunlight, heat, or sweating. Darier disease may be accompanied by oral mucosal involvement including fine white papules on the palate.1 The condition also can be accompanied by hand and nail involvement (95% of cases) including palmar pitting, punctate keratoses, hemorrhagic macules, palmoplantar keratoderma, and acrokeratosis verruciformis–like lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Nail changes predominately occur on the fingers, manifesting as longitudinal splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, or characteristic white and red longitudinal bands with V-shaped nicks at the free margin of the nail. In linear DD, hand and nail involvement is rare and, when present, ipsilateral to the primary lesions.1,2

The clinical variants of DD are classified by lesion morphology or distribution, or both. Morphological variants include vesiculobullous, cornified, erosive, acral hemorrhagic, and guttate leukodermic macular.1,2 The clinical features of chronic relapsing vesicular lesions and histologic findings described in this case are consistent with vesiculobullous DD, though genetic testing was not performed.3,4 As in our case, some patients lack a family history and the disease is thought to be the result of genetic mosaicism or somatic postzygotic mutations that affect a limited number of cells. These mosaic variants are named by their cutaneous distribution (ie, linear, segmental, unilateral, localized) and tend to course along the Blaschko lines, most commonly on the trunk. Studies have shown various types of mutations specific to the ATP2A2 gene in the affected tissue but not in the unaffected skin.5 This gene encodes for sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase SERCA2, which is responsible for intracellular calcium signaling. These mosaic forms of DD are unlikely to be inherited by offspring, in contrast to patients with mosaic epidermal nevi with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis who have a high likelihood of having children with generalized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.6

Darier disease is a chronic incurable disease. Topical corticosteroid, retinoid, 5-fluorouracil, keratolytics, and laser ablation or excision are used in mild and limited disease with mixed outcomes.7 Oral retinoids are effective in severe or systemic cases of DD by inhibiting hyperkeratosis.8 Individuals with DD are predisposed to infection, warranting regular surveillance and use of antimicrobials and bleach baths. In addition to prophylaxis for bacterial superinfection, patients also are predisposed to getting disseminated herpes simplex virus in the form of eczema herpeticum.

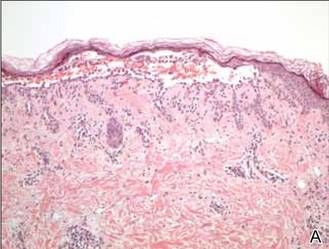

In our patient, the diagnosis was confirmed by performing a punch biopsy from one of the vesicular lesions. Histopathologic examination revealed suprabasal acantholytic dyskeratosis with superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammation with eosinophils (Figure). Immunohistochemical staining showed no evidence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2.

Histopathology revealed suprabasal acantholysis forming an intraepidermal cleft with superficial perivascular inflammation (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100) and acantholysis with dyskeratotic keratinocytes floating within the intraepidermal cleft (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Our patient was prescribed tretinoin cream 0.1% daily and was advised to use sun protection and stop valacyclovir. At follow-up she noted decreased frequency of outbreaks after starting the tretinoin cream and the patient has now been free of any outbreaks for 8 months.

1. Burge SM, Wilkinson JD. Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:40-50.

2. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105.

3. Kakar B, Kabir S, Garg VK, et al. A case of bullous Darier’s disease histologically mimicking Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:28.

4. Telfer NR, Burge SM, Ryan TJ. Vesiculo-bullous Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:831-834.

5. Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge SM, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

6. O’Malley MP, Haake A, Goldsmith L, et al. Localized Darier disease. implications for genetic studies. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1134-1138.

7. Le Bidre E, Delage M, Celerier P, et al. Efficacy and risks of topical 5-fluorouracil in Darier’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:455-459.

8. Abe M, Yasuda M, Yokoyama Y, et al. Successful treatment of combination therapy with tacalcitol lotion associated with sunscreen for localized Darier’s disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:718-721.

The Diagnosis: Linear Vesiculobullous Keratosis Follicularis (Darier Disease)

Darier disease (DD), or keratosis follicularis, is typically an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by greasy hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into warty plaques with a predilection for seborrheic areas. The lesions usually are pruritic; malodorous; and may be exacerbated by sunlight, heat, or sweating. Darier disease may be accompanied by oral mucosal involvement including fine white papules on the palate.1 The condition also can be accompanied by hand and nail involvement (95% of cases) including palmar pitting, punctate keratoses, hemorrhagic macules, palmoplantar keratoderma, and acrokeratosis verruciformis–like lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Nail changes predominately occur on the fingers, manifesting as longitudinal splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, or characteristic white and red longitudinal bands with V-shaped nicks at the free margin of the nail. In linear DD, hand and nail involvement is rare and, when present, ipsilateral to the primary lesions.1,2

The clinical variants of DD are classified by lesion morphology or distribution, or both. Morphological variants include vesiculobullous, cornified, erosive, acral hemorrhagic, and guttate leukodermic macular.1,2 The clinical features of chronic relapsing vesicular lesions and histologic findings described in this case are consistent with vesiculobullous DD, though genetic testing was not performed.3,4 As in our case, some patients lack a family history and the disease is thought to be the result of genetic mosaicism or somatic postzygotic mutations that affect a limited number of cells. These mosaic variants are named by their cutaneous distribution (ie, linear, segmental, unilateral, localized) and tend to course along the Blaschko lines, most commonly on the trunk. Studies have shown various types of mutations specific to the ATP2A2 gene in the affected tissue but not in the unaffected skin.5 This gene encodes for sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase SERCA2, which is responsible for intracellular calcium signaling. These mosaic forms of DD are unlikely to be inherited by offspring, in contrast to patients with mosaic epidermal nevi with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis who have a high likelihood of having children with generalized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.6

Darier disease is a chronic incurable disease. Topical corticosteroid, retinoid, 5-fluorouracil, keratolytics, and laser ablation or excision are used in mild and limited disease with mixed outcomes.7 Oral retinoids are effective in severe or systemic cases of DD by inhibiting hyperkeratosis.8 Individuals with DD are predisposed to infection, warranting regular surveillance and use of antimicrobials and bleach baths. In addition to prophylaxis for bacterial superinfection, patients also are predisposed to getting disseminated herpes simplex virus in the form of eczema herpeticum.

In our patient, the diagnosis was confirmed by performing a punch biopsy from one of the vesicular lesions. Histopathologic examination revealed suprabasal acantholytic dyskeratosis with superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammation with eosinophils (Figure). Immunohistochemical staining showed no evidence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2.

Histopathology revealed suprabasal acantholysis forming an intraepidermal cleft with superficial perivascular inflammation (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100) and acantholysis with dyskeratotic keratinocytes floating within the intraepidermal cleft (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Our patient was prescribed tretinoin cream 0.1% daily and was advised to use sun protection and stop valacyclovir. At follow-up she noted decreased frequency of outbreaks after starting the tretinoin cream and the patient has now been free of any outbreaks for 8 months.

The Diagnosis: Linear Vesiculobullous Keratosis Follicularis (Darier Disease)

Darier disease (DD), or keratosis follicularis, is typically an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by greasy hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into warty plaques with a predilection for seborrheic areas. The lesions usually are pruritic; malodorous; and may be exacerbated by sunlight, heat, or sweating. Darier disease may be accompanied by oral mucosal involvement including fine white papules on the palate.1 The condition also can be accompanied by hand and nail involvement (95% of cases) including palmar pitting, punctate keratoses, hemorrhagic macules, palmoplantar keratoderma, and acrokeratosis verruciformis–like lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Nail changes predominately occur on the fingers, manifesting as longitudinal splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, or characteristic white and red longitudinal bands with V-shaped nicks at the free margin of the nail. In linear DD, hand and nail involvement is rare and, when present, ipsilateral to the primary lesions.1,2

The clinical variants of DD are classified by lesion morphology or distribution, or both. Morphological variants include vesiculobullous, cornified, erosive, acral hemorrhagic, and guttate leukodermic macular.1,2 The clinical features of chronic relapsing vesicular lesions and histologic findings described in this case are consistent with vesiculobullous DD, though genetic testing was not performed.3,4 As in our case, some patients lack a family history and the disease is thought to be the result of genetic mosaicism or somatic postzygotic mutations that affect a limited number of cells. These mosaic variants are named by their cutaneous distribution (ie, linear, segmental, unilateral, localized) and tend to course along the Blaschko lines, most commonly on the trunk. Studies have shown various types of mutations specific to the ATP2A2 gene in the affected tissue but not in the unaffected skin.5 This gene encodes for sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase SERCA2, which is responsible for intracellular calcium signaling. These mosaic forms of DD are unlikely to be inherited by offspring, in contrast to patients with mosaic epidermal nevi with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis who have a high likelihood of having children with generalized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.6

Darier disease is a chronic incurable disease. Topical corticosteroid, retinoid, 5-fluorouracil, keratolytics, and laser ablation or excision are used in mild and limited disease with mixed outcomes.7 Oral retinoids are effective in severe or systemic cases of DD by inhibiting hyperkeratosis.8 Individuals with DD are predisposed to infection, warranting regular surveillance and use of antimicrobials and bleach baths. In addition to prophylaxis for bacterial superinfection, patients also are predisposed to getting disseminated herpes simplex virus in the form of eczema herpeticum.

In our patient, the diagnosis was confirmed by performing a punch biopsy from one of the vesicular lesions. Histopathologic examination revealed suprabasal acantholytic dyskeratosis with superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammation with eosinophils (Figure). Immunohistochemical staining showed no evidence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2.

Histopathology revealed suprabasal acantholysis forming an intraepidermal cleft with superficial perivascular inflammation (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100) and acantholysis with dyskeratotic keratinocytes floating within the intraepidermal cleft (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Our patient was prescribed tretinoin cream 0.1% daily and was advised to use sun protection and stop valacyclovir. At follow-up she noted decreased frequency of outbreaks after starting the tretinoin cream and the patient has now been free of any outbreaks for 8 months.

1. Burge SM, Wilkinson JD. Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:40-50.

2. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105.

3. Kakar B, Kabir S, Garg VK, et al. A case of bullous Darier’s disease histologically mimicking Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:28.

4. Telfer NR, Burge SM, Ryan TJ. Vesiculo-bullous Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:831-834.

5. Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge SM, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

6. O’Malley MP, Haake A, Goldsmith L, et al. Localized Darier disease. implications for genetic studies. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1134-1138.

7. Le Bidre E, Delage M, Celerier P, et al. Efficacy and risks of topical 5-fluorouracil in Darier’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:455-459.

8. Abe M, Yasuda M, Yokoyama Y, et al. Successful treatment of combination therapy with tacalcitol lotion associated with sunscreen for localized Darier’s disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:718-721.

1. Burge SM, Wilkinson JD. Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:40-50.

2. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105.

3. Kakar B, Kabir S, Garg VK, et al. A case of bullous Darier’s disease histologically mimicking Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:28.

4. Telfer NR, Burge SM, Ryan TJ. Vesiculo-bullous Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:831-834.

5. Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge SM, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

6. O’Malley MP, Haake A, Goldsmith L, et al. Localized Darier disease. implications for genetic studies. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1134-1138.

7. Le Bidre E, Delage M, Celerier P, et al. Efficacy and risks of topical 5-fluorouracil in Darier’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:455-459.

8. Abe M, Yasuda M, Yokoyama Y, et al. Successful treatment of combination therapy with tacalcitol lotion associated with sunscreen for localized Darier’s disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:718-721.

A 42-year-old woman presented with an intermittent nontender and minimally pruritic rash localized to the left side of the trunk of 20 years’ duration. Four to 6 times per year blisters would develop and then resolve after 1 to 2 weeks with mildly pruritic brown patches. These patches would resolve within approximately 4 weeks. Most notably, the condition was exacerbated by sunlight and heat, though stress sometimes led to an outbreak of vesicles. The patient reported that the eruption, which she was told was recurrent shingles, would improve with oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and did not improve with topical steroid usage. She never had antecedent or concurrent fevers, shortness of breath, arthralgia, or cold sores. There was no family history of any blistering skin conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa, pemphigus, Darier disease, or bullous pemphigoid. Her partner also did not have a history of similar rashes, and the patient denied any history of travel outside of England and the southwestern United States. Initial physical examination revealed clustered vesicles surrounded by brown-pink patches in a blaschkoid pattern spanning from the anterior to posterior aspects of the left flank. Notably, the patient had no oral lesions and no changes of the hair or nails.

A new way to treat ITP?

Photo courtesy of

St. Michael’s Hospital

New research appears to explain why symptoms and treatment responses vary in patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). The work has also revealed a new potential treatment option.

Researchers previously thought that all ITP antibodies lead platelets to the spleen for destruction.

But the new study, published in Nature Communications, has shown that some ITP antibodies destroy platelets in the liver.

“Every existing treatment for ITP has been dedicated to stopping antibodies from destroying platelets in the spleen, but we’ve discovered that some antibodies actually destroy platelets in the liver,” said study author Heyu Ni, MD, of St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

The discovery was made by analyzing mice treated with two monoclonal antibodies, each targeting a different protein on the surface of platelets—GPIb or GPIIbIIIa.

The researchers found that antibodies targeting GPIb lead to platelet destruction in the liver, and those targeting GPIIbIIIa cause platelet destruction in the spleen.

“By detecting the specific antibodies present in someone with ITP, we may be able to detect where and how the immune system will attack,” Dr Ni said. “And because we now know the liver’s immune response destroys platelets covered with GPIb, we may be able to design new therapies to stop this type of platelet destruction.”

Dr Ni noted that sialidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu) may be able to inhibit the liver’s immune response to the platelets. In fact, he and his colleagues used human blood samples to test whether Tamiflu might inhibit antibodies targeting GPIb.

“Using healthy blood samples and ITP antibodies in a test tube, we showed that Tamiflu may impede platelet destruction for those with antibodies that target GPIb,” Dr Ni said.

Based on an early abstract of this research, some ITP patients around the world have been treated with oseltamivir phosphate. These patients were extremely resistant to existing treatments targeting the spleen, and their ITP was considered life-threatening.

Although these instances of experimental treatment have been successful, Dr Ni said more research is needed to verify the safety and efficacy of this approach. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

St. Michael’s Hospital

New research appears to explain why symptoms and treatment responses vary in patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). The work has also revealed a new potential treatment option.

Researchers previously thought that all ITP antibodies lead platelets to the spleen for destruction.

But the new study, published in Nature Communications, has shown that some ITP antibodies destroy platelets in the liver.

“Every existing treatment for ITP has been dedicated to stopping antibodies from destroying platelets in the spleen, but we’ve discovered that some antibodies actually destroy platelets in the liver,” said study author Heyu Ni, MD, of St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

The discovery was made by analyzing mice treated with two monoclonal antibodies, each targeting a different protein on the surface of platelets—GPIb or GPIIbIIIa.

The researchers found that antibodies targeting GPIb lead to platelet destruction in the liver, and those targeting GPIIbIIIa cause platelet destruction in the spleen.

“By detecting the specific antibodies present in someone with ITP, we may be able to detect where and how the immune system will attack,” Dr Ni said. “And because we now know the liver’s immune response destroys platelets covered with GPIb, we may be able to design new therapies to stop this type of platelet destruction.”

Dr Ni noted that sialidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu) may be able to inhibit the liver’s immune response to the platelets. In fact, he and his colleagues used human blood samples to test whether Tamiflu might inhibit antibodies targeting GPIb.

“Using healthy blood samples and ITP antibodies in a test tube, we showed that Tamiflu may impede platelet destruction for those with antibodies that target GPIb,” Dr Ni said.

Based on an early abstract of this research, some ITP patients around the world have been treated with oseltamivir phosphate. These patients were extremely resistant to existing treatments targeting the spleen, and their ITP was considered life-threatening.

Although these instances of experimental treatment have been successful, Dr Ni said more research is needed to verify the safety and efficacy of this approach. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

St. Michael’s Hospital

New research appears to explain why symptoms and treatment responses vary in patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). The work has also revealed a new potential treatment option.

Researchers previously thought that all ITP antibodies lead platelets to the spleen for destruction.

But the new study, published in Nature Communications, has shown that some ITP antibodies destroy platelets in the liver.

“Every existing treatment for ITP has been dedicated to stopping antibodies from destroying platelets in the spleen, but we’ve discovered that some antibodies actually destroy platelets in the liver,” said study author Heyu Ni, MD, of St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

The discovery was made by analyzing mice treated with two monoclonal antibodies, each targeting a different protein on the surface of platelets—GPIb or GPIIbIIIa.

The researchers found that antibodies targeting GPIb lead to platelet destruction in the liver, and those targeting GPIIbIIIa cause platelet destruction in the spleen.

“By detecting the specific antibodies present in someone with ITP, we may be able to detect where and how the immune system will attack,” Dr Ni said. “And because we now know the liver’s immune response destroys platelets covered with GPIb, we may be able to design new therapies to stop this type of platelet destruction.”

Dr Ni noted that sialidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu) may be able to inhibit the liver’s immune response to the platelets. In fact, he and his colleagues used human blood samples to test whether Tamiflu might inhibit antibodies targeting GPIb.

“Using healthy blood samples and ITP antibodies in a test tube, we showed that Tamiflu may impede platelet destruction for those with antibodies that target GPIb,” Dr Ni said.

Based on an early abstract of this research, some ITP patients around the world have been treated with oseltamivir phosphate. These patients were extremely resistant to existing treatments targeting the spleen, and their ITP was considered life-threatening.

Although these instances of experimental treatment have been successful, Dr Ni said more research is needed to verify the safety and efficacy of this approach. ![]()

Group creates mouse model of RUNX1-mutated AML

Researchers have developed a mouse model to help them understand why patients with RUNX1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) respond poorly to chemotherapy.

Approximately 15% of AML patients harbor a mutation in the RUNX1 gene.

In these patients, anthracycline/cytarabine-based chemotherapy does not eradicate AML cells from the bone marrow.

But scientists don’t fully understand the underlying mechanisms protecting these residual cells.

Jason H. Mendler, MD, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York, and his colleagues have suggested that a genetically defined mouse model of RUNX1-mutated AML is the ideal platform to investigate the cellular mechanisms protecting residual AML cells in this disease subtype.

“Like all cancers, leukemia is not a one-size-fits-all, and, therefore, it’s important to find better ways to study high-risk subtypes of the disease,” Dr Mendler said. “We believe our mouse model will allow us to quickly define new ways to target this challenging disease.”

Dr Mendler and his colleagues described their model in PLOS ONE.

The researchers began with a patient-derived cell line of RUNX1-mutated, cytogenetically normal AML. They injected these cells into NOD-SCID-γ mice and observed leukemic engraftment in the bone marrow, spleen, and peripheral blood within 6 weeks.

When the researchers treated the mice with anthracycline/cytarabine-based chemotherapy, they saw AML clearance in the spleen and peripheral blood. But leukemic cells remained in the bone marrow.

Dr Mendler and his colleagues also found their mouse model contained mutations in 5 genes aside from RUNX1—ASXL1, CEBPA, GATA2, NRAS, and SETBP1.

The team said further investigation will be focused on identifying the interplay of genes and pathways that are critical to mediating chemotherapy resistance in this model. ![]()

Researchers have developed a mouse model to help them understand why patients with RUNX1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) respond poorly to chemotherapy.

Approximately 15% of AML patients harbor a mutation in the RUNX1 gene.

In these patients, anthracycline/cytarabine-based chemotherapy does not eradicate AML cells from the bone marrow.

But scientists don’t fully understand the underlying mechanisms protecting these residual cells.

Jason H. Mendler, MD, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York, and his colleagues have suggested that a genetically defined mouse model of RUNX1-mutated AML is the ideal platform to investigate the cellular mechanisms protecting residual AML cells in this disease subtype.

“Like all cancers, leukemia is not a one-size-fits-all, and, therefore, it’s important to find better ways to study high-risk subtypes of the disease,” Dr Mendler said. “We believe our mouse model will allow us to quickly define new ways to target this challenging disease.”

Dr Mendler and his colleagues described their model in PLOS ONE.

The researchers began with a patient-derived cell line of RUNX1-mutated, cytogenetically normal AML. They injected these cells into NOD-SCID-γ mice and observed leukemic engraftment in the bone marrow, spleen, and peripheral blood within 6 weeks.

When the researchers treated the mice with anthracycline/cytarabine-based chemotherapy, they saw AML clearance in the spleen and peripheral blood. But leukemic cells remained in the bone marrow.

Dr Mendler and his colleagues also found their mouse model contained mutations in 5 genes aside from RUNX1—ASXL1, CEBPA, GATA2, NRAS, and SETBP1.

The team said further investigation will be focused on identifying the interplay of genes and pathways that are critical to mediating chemotherapy resistance in this model. ![]()

Researchers have developed a mouse model to help them understand why patients with RUNX1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) respond poorly to chemotherapy.

Approximately 15% of AML patients harbor a mutation in the RUNX1 gene.

In these patients, anthracycline/cytarabine-based chemotherapy does not eradicate AML cells from the bone marrow.

But scientists don’t fully understand the underlying mechanisms protecting these residual cells.

Jason H. Mendler, MD, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York, and his colleagues have suggested that a genetically defined mouse model of RUNX1-mutated AML is the ideal platform to investigate the cellular mechanisms protecting residual AML cells in this disease subtype.

“Like all cancers, leukemia is not a one-size-fits-all, and, therefore, it’s important to find better ways to study high-risk subtypes of the disease,” Dr Mendler said. “We believe our mouse model will allow us to quickly define new ways to target this challenging disease.”

Dr Mendler and his colleagues described their model in PLOS ONE.

The researchers began with a patient-derived cell line of RUNX1-mutated, cytogenetically normal AML. They injected these cells into NOD-SCID-γ mice and observed leukemic engraftment in the bone marrow, spleen, and peripheral blood within 6 weeks.

When the researchers treated the mice with anthracycline/cytarabine-based chemotherapy, they saw AML clearance in the spleen and peripheral blood. But leukemic cells remained in the bone marrow.

Dr Mendler and his colleagues also found their mouse model contained mutations in 5 genes aside from RUNX1—ASXL1, CEBPA, GATA2, NRAS, and SETBP1.

The team said further investigation will be focused on identifying the interplay of genes and pathways that are critical to mediating chemotherapy resistance in this model. ![]()

Sepsis and Septic Shock Readmission Risk

Despite its decreasing mortality, sepsis remains a leading reason for intensive care unit (ICU) admission and is associated with crude mortality in excess of 25%.[1, 2] In the United States there are between 660,000 and 750,000 sepsis hospitalizations annually, with the direct costs surpassing $24 billion.[3, 4, 5] As mortality rates have begun to fall, attention has shifted to issues of morbidity and recovery, the intermediate and longer‐term consequences associated with survivorship, and how interventions made while the patient is acutely ill in the ICU alter later health outcomes.[3, 5, 6, 7, 8]

One area of particular interest is the need for healthcare utilization following an acute admission for sepsis, and specifically rehospitalization within 30 days of discharge. This outcome is important not just from the perspective of the patient's well‐being, but also from the point of view of healthcare financing. Through the establishment of Hospital Readmission Reduction Program, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have sharply reduced reimbursement to hospitals for excessive rates of 30‐day readmissions.[9]

For sepsis, little is known about such readmissions, and even less about how to prevent them. A handful of studies suggest that this rate is between 5% and 26%.[10, 11, 12, 13] Whereas some of these studies looked at some of the factors that impact readmissions,[11, 12] none examined the potential contribution of microbiology of sepsis to this outcome.

To explore these questions, we conducted a single‐center retrospective cohort study among critically ill patients admitted to the ICU with severe culture‐positive sepsis and/or septic shock and determined the rate of early posthospital discharge readmission. In addition, we sought to elucidate predictors of subsequent readmission.

METHODS

Study Design and Ethical Standards

We conducted a single‐center retrospective cohort study from January 2008 to December 2012. The study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee, and informed consent was waived because the data collection was retrospective without any patient‐identifying information. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Aspects of our methodology have been previously published.[14]

Primary Endpoint

All‐cause readmission to an acute‐care facility in the 30 days following discharge after the index hospitalization with sepsis served as the primary endpoint. The index hospitalizations occurred at the Barnes‐Jewish Hospital, a 1200‐bed inner‐city academic institution that serves as the main teaching institution for BJC HealthCare, a large integrated healthcare system of both inpatient and outpatient care. BJC includes a total of 13 hospitals in a compact geographic region surrounding and including St. Louis, Missouri, and we included readmission to any of these hospitals in our analysis. Persons treated within this healthcare system are, in nearly all cases, readmitted to 1 of the system's participating 13 hospitals. If a patient who receives healthcare in the system presents to an out‐of‐system hospital, he/she is often transferred back into the integrated system because of issues of insurance coverage.

Study Cohort

All consecutive adult ICU patients were included if (1) They had a positive blood culture for a pathogen (Cultures positive only for coagulase negative Staphylococcus aureus were excluded as contaminants.), (2) there was an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) code corresponding to an acute organ dysfunction,[4] and (3) they survived their index hospitalization. Only the first episode of sepsis was included as the index hospitalization.

Definitions

All‐cause 30‐day readmission, was defined as a repeat hospitalization within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization among survivors of culture‐positive severe sepsis or septic shock. The definition of severe sepsis was based on discharge ICD‐9‐CM codes for acute organ dysfunction.[3] Patients were classified as having septic shock if vasopressors (norepinephrine, dopamine, epinephrine, phenylephrine, or vasopressin) were initiated within 24 hours of the blood culture collection date and time.

Initially appropriate antimicrobial treatment (IAAT) was deemed appropriate if the initially prescribed antibiotic regimen was active against the identified pathogen based on in vitro susceptibility testing and administered for at least 24 hours within 24 hours following blood culture collection. All other regimens were classified as non‐IAAT. Combination antimicrobial treatment was not required for IAAT designation.[15] Prior antibiotic exposure and prior hospitalization occurred within the preceding 90 days, and prior bacteremia within 30 days of the index episode. Multidrug resistance (MDR) among Gram‐negative bacteria was defined as nonsusceptibility to at least 1 antimicrobial agent from at least 3 different antimicrobial classes.[16] Both extended spectrum ‐lactamase (ESBL) organisms and carbapenemase‐producing Enterobacteriaceae were identified via molecular testing.

Healthcare‐associated (HCA) infections were defined by the presence of at least 1 of the following: (1) recent hospitalization, (2) immune suppression (defined as any primary immune deficiency or acquired immune deficiency syndrome or exposure within 3 prior months to immunosuppressive treatmentschemotherapy, radiation therapy, or steroids), (3) nursing home residence, (4) hemodialysis, (5) prior antibiotics. and (6) index bacteremia deemed a hospital‐acquired bloodstream infection (occurring >2 days following index admission date). Acute kidney injury (AKI) was defined according to the RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End‐stage) criteria based on the greatest change in serum creatinine (SCr).[17]

Data Elements

Patient‐specific baseline characteristics and process of care variables were collected from the automated hospital medical record, microbiology database, and pharmacy database of Barnes‐Jewish Hospital. Electronic inpatient and outpatient medical records available for all patients in the BJC HealthCare system were reviewed to determine prior antibiotic exposure. The baseline characteristics collected during the index hospitalization included demographics and comorbid conditions. The comorbidities were identified based on their corresponding ICD‐9‐CM codes. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II and Charlson comorbidity scores were calculated based on clinical data present during the 24 hours after the positive blood cultures were obtained.[18] This was done to accommodate patients with community‐acquired and healthcare‐associated community‐onset infections who only had clinical data available after blood cultures were drawn. Lowest and highest SCr levels were collected during the index hospitalization to determine each patient's AKI status.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations and as medians with 25th and 75th percentiles. Differences between mean values were tested via the Student t test, and between medians using the Mann‐Whitney U test. Categorical data were summarized as proportions, and the 2 test or Fisher exact test for small samples was used to examine differences between groups. We developed multiple logistic regression models to identify clinical risk factors that were associated with 30‐day all‐cause readmission. All risk factors that were significant at 0.20 in the univariate analyses, as well as all biologically plausible factors even if they did not reach this level of significance, were included in the models. All variables entered into the models were assessed for collinearity, and interaction terms were tested. The most parsimonious models were derived using the backward manual elimination method, and the best‐fitting model was chosen based on the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUROC or the C statistic). The model's calibration was assessed with the Hosmer‐Lemeshow goodness‐of‐fit test. All tests were 2‐tailed, and a P value <0.05 represented statistical significance.

All computations were performed in Stata/SE, version 9 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Role of Sponsor

The sponsor had no role in the design, analyses, interpretation, or publication of the study.

RESULTS

Among the 1697 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock who were discharged alive from the hospital, 543 (32.0%) required a rehospitalization within 30 days. There were no differences in age or gender distribution between the groups (Table 1). All comorbidities examined were more prevalent among those with a 30‐day readmission than among those without, with the median Charlson comorbidity score reflecting this imbalance (5 vs 4, P<0.001). Similarly, most of the HCA risk factors were more prevalent among the readmitted group than the comparator group, with HCA sepsis among 94.2% of the former and 90.7% of the latter (P = 0.014).

| 30‐Day Readmission = Yes | 30‐Day Readmission = No | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 543 | % = 32.00% | N = 1,154 | % = 68.00% | P Value | |

| |||||

| Baseline characteristics | |||||

| Age, y | |||||

| Mean SD | 58.5 15.7 | 59.5 15.8 | |||

| Median (25, 75) | 60 (49, 69) | 60 (50, 70) | 0.297 | ||

| Race | |||||

| Caucasian | 335 | 61.69% | 769 | 66.64% | 0.046 |

| African American | 157 | 28.91% | 305 | 26.43% | 0.284 |

| Other | 9 | 1.66% | 22 | 1.91% | 0.721 |

| Sex, female | 244 | 44.94% | 537 | 46.53% | 0.538 |

| Admission source | |||||

| Home | 374 | 68.88% | 726 | 62.91% | 0.016 |

| Nursing home, rehab, or LTAC | 39 | 7.81% | 104 | 9.01% | 0.206 |

| Transfer from another hospital | 117 | 21.55% | 297 | 25.74% | 0.061 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| CHF | 131 | 24.13% | 227 | 19.67% | 0.036 |

| COPD | 156 | 28.73% | 253 | 21.92% | 0.002 |

| CLD | 83 | 15.29% | 144 | 12.48% | 0.113 |

| DM | 175 | 32.23% | 296 | 25.65% | 0.005 |

| CKD | 137 | 25.23% | 199 | 17.24% | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 225 | 41.44% | 395 | 34.23% | 0.004 |

| HIV | 11 | 2.03% | 10 | 0.87% | 0.044 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||||

| Mean SD | 5.24 3.32 | 4.48 3.35 | |||

| Median (25, 75) | 5 (3, 8) | 4 (2, 7) | <0.001 | ||

| HCA RF | 503 | 94.19% | 1,019 | 90.66% | 0.014 |

| Hemodialysis | 65 | 12.01% | 114 | 9.92% | 0.192 |

| Immune suppression | 193 | 36.07% | 352 | 31.21% | 0.044 |

| Prior hospitalization | 339 | 65.07% | 620 | 57.09% | 0.002 |

| Nursing home residence | 39 | 7.81% | 104 | 9.01% | 0.206 |

| Prior antibiotics | 301 | 55.43% | 568 | 49.22% | 0.017 |

| Hospital‐acquired BSI* | 240 | 44.20% | 485 | 42.03% | 0.399 |

| Prior bacteremia within 30 days | 88 | 16.21% | 154 | 13.34% | 0.116 |

| Sepsis‐related parameters | |||||

| LOS prior to bacteremia, d | |||||

| Mean SD | 6.65 11.22 | 5.88 10.81 | |||

| Median (25, 75) | 1 (0, 10) | 0 (0, 8) | 0.250 | ||

| Surgery | |||||

| None | 362 | 66.67% | 836 | 72.44% | 0.015 |

| Abdominal | 104 | 19.15% | 167 | 14.47% | 0.014 |

| Extra‐abdominal | 73 | 13.44% | 135 | 11.70% | 0.306 |

| Status unknown | 4 | 0.74% | 16 | 1.39% | 0.247 |

| Central line | 333 | 64.41% | 637 | 57.80% | 0.011 |

| TPN at the time of bacteremia or prior to it during index hospitalization | 52 | 9.74% | 74 | 5.45% | 0.017 |

| APACHE II | |||||

| Mean SD | 15.08 5.47 | 15.35 5.43 | |||

| Median (25, 75) | 15 (11, 18) | 15 (12, 19) | 0.275 | ||

| Severe sepsis | 361 | 66.48% | 747 | 64.73% | 0.480 |

| Septic shock requiring vasopressors | 182 | 33.52% | 407 | 35.27% | |

| On MV | 104 | 19.22% | 251 | 21.90% | 0.208 |

| Peak WBC (103/L) | |||||

| Mean SD | 22.26 25.20 | 22.14 17.99 | |||

| Median (25, 75) | 17.1 (8.9, 30.6) | 16.9 (10, 31) | 0.654 | ||

| Lowest serum SCr, mg/dL | |||||

| Mean SD | 1.02 1.05 | 0.96 1.03 | |||

| Median (25, 75) | 0.68 (0.5, 1.06) | 0.66 (0.49, 0.96) | 0.006 | ||

| Highest serum SCr, mg/dL | |||||

| Mean SD | 2.81 2.79 | 2.46 2.67 | |||

| Median (25, 75) | 1.68 (1.04, 3.3) | 1.41 (0.94, 2.61) | 0.001 | ||

| RIFLE category | |||||

| None | 81 | 14.92% | 213 | 18.46% | 0.073 |

| Risk | 112 | 20.63% | 306 | 26.52% | 0.009 |

| Injury | 133 | 24.49% | 247 | 21.40% | 0.154 |

| Failure | 120 | 22.10% | 212 | 18.37% | 0.071 |

| Loss | 50 | 9.21% | 91 | 7.89% | 0.357 |

| End‐stage | 47 | 8.66% | 85 | 7.37% | 0.355 |

| Infection source | |||||

| Urine | 95 | 17.50% | 258 | 22.36% | 0.021 |

| Abdomen | 69 | 12.71% | 113 | 9.79% | 0.070 |

| Lung | 93 | 17.13% | 232 | 20.10% | 0.146 |

| Line | 91 | 16.76% | 150 | 13.00% | 0.038 |

| CNS | 1 | 0.18% | 16 | 1.39% | 0.012 |

| Skin | 51 | 9.39% | 82 | 7.11% | 0.102 |

| Unknown | 173 | 31.86% | 375 | 32.50% | 0.794 |

During the index hospitalization, 589 patients (34.7%) suffered from septic shock requiring vasopressors; this did not impact the 30‐day readmission risk (Table 1). Commensurately, markers of severity of acute illness (APACHE II score, mechanical ventilation, peak white blood cell count) did not differ between the groups. With respect to the primary source of sepsis, urine was less, whereas central nervous system was more likely among those readmitted within 30 days. Similarly, there was a significant imbalance between the groups in the prevalence of AKI (Table 1). Specifically, those who did require a readmission were slightly less likely to have sustained no AKI (RIFLE: None; 14.9% vs 18.5%, P = 0.073). Those requiring readmission were also less likely to be in the category RIFLE: Risk (20.6% vs 26.5%, P = 0.009). The direction of this disparity was reversed for the Injury and Failure categories. No differences between groups were seen among those with categories Loss and end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) (Table 1).

The microbiology of sepsis did not differ in most respects between the 30‐day readmission groups, save for several organisms (Table 2). Most strikingly, those who required a readmission were more likely than those who did not to be infected with Bacteroides spp, Candida spp, an MDR or an ESBL organism (Table 2). As for the outcomes of the index hospitalization, those with a repeat admission had a longer overall and postonset of sepsis initial hospital length of stay, and were less likely to be discharged either home without home health care or transferred to another hospital at the end of their index hospitalization (Table 3).

| 30‐Day Readmission = Yes | 30‐Day Readmission = No | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| |||||

| 543 | 32.00% | 1,154 | 68.00% | ||

| Gram‐positive BSI | 260 | 47.88% | 580 | 50.26% | 0.376 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 138 | 25.41% | 287 | 24.87% | 0.810 |

| MRSA | 78 | 14.36% | 147 | 12.74% | 0.358 |

| VISA | 6 | 1.10% | 9 | 0.78% | 0.580 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 7 | 1.29% | 33 | 2.86% | 0.058 |

| Streptococcus spp | 34 | 6.26% | 81 | 7.02% | 0.606 |

| Peptostreptococcus spp | 5 | 0.92% | 15 | 1.30% | 0.633 |

| Clostridium perfringens | 4 | 0.74% | 10 | 0.87% | 1.000 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 54 | 9.94% | 108 | 9.36% | 0.732 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 29 | 5.34% | 63 | 5.46% | 1.000 |

| VRE | 36 | 6.63% | 70 | 6.07% | 0.668 |

| Gram‐negative BSI | 231 | 42.54% | 515 | 44.63% | 0.419 |

| Escherichia coli | 54 | 9.94% | 151 | 13.08% | 0.067 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 54 | 9.94% | 108 | 9.36% | 0.723 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 11 | 2.03% | 18 | 1.56% | 0.548 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 6 | 1.10% | 13 | 1.13% | 1.000 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 21 | 3.87% | 44 | 3.81% | 1.000 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 28 | 5.16% | 65 | 5.63% | 0.733 |

| Acinetobacter spp | 8 | 1.47% | 27 | 2.34% | 0.276 |

| Bacteroides spp | 25 | 4.60% | 30 | 2.60% | 0.039 |

| Serratia marcescens | 14 | 2.58% | 21 | 1.82% | 0.360 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 3 | 0.55% | 8 | 0.69% | 1.000 |

| Achromobacter spp | 2 | 0.37% | 3 | 0.17% | 0.597 |

| Aeromonas spp | 2 | 0.37% | 1 | 0.09% | 0.241 |

| Burkholderia cepacia | 0 | 0.00% | 6 | 0.52% | 0.186 |

| Citrobacter freundii | 2 | 0.37% | 15 | 1.39% | 0.073 |

| Fusobacterium spp | 7 | 1.29% | 10 | 0.87% | 0.438 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1 | 0.18% | 4 | 0.35% | 1.000 |

| Prevotella spp | 1 | 0.18% | 6 | 0.52% | 0.441 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 9 | 1.66% | 39 | 3.38% | 0.058 |

| MDR PA | 2 | 0.37% | 7 | 0.61% | 0.727 |

| ESBL | 10 | 6.25% | 8 | 2.06% | 0.017 |

| CRE | 2 | 1.25% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.028 |

| MDR Gram‐negative or Gram‐positive | 231 | 47.53% | 450 | 41.86% | 0.036 |

| Candida spp | 58 | 10.68% | 76 | 6.59% | 0.004 |

| Polymicrobal BSI | 50 | 9.21% | 111 | 9.62% | 0.788 |

| Initially inappropriate treatment | 119 | 21.92% | 207 | 17.94% | 0.052 |

| 30‐Day Readmission = Yes | 30‐Day Readmission = No | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 543 | % = 32.00% | N = 1,154 | % = 68.00% | P Value | |

| |||||

| Hospital LOS, days | |||||

| Mean SD | 26.44 23.27 | 23.58 21.79 | 0.019 | ||

| Median (25, 75) | 19.16 (9.66, 35.86) | 17.77 (8.9, 30.69) | |||

| Hospital LOS following BSI onset, days | |||||

| Mean SD | 19.80 18.54 | 17.69 17.08 | 0.022 | ||

| Median (25, 75) | 13.9 (7.9, 25.39) | 12.66 (7.05, 22.66) | |||

| Discharge destination | |||||

| Home | 125 | 23.02% | 334 | 28.94% | 0.010 |

| Home with home care | 163 | 30.02% | 303 | 26.26% | 0.105 |

| Rehab | 81 | 14.92% | 149 | 12.91% | 0.260 |

| LTAC | 41 | 7.55% | 87 | 7.54% | 0.993 |

| Transfer to another hospital | 1 | 0.18% | 19 | 1.65% | 0.007 |

| SNF | 132 | 24.31% | 262 | 22.70% | 0.465 |

In a logistic regression model, 5 factors emerged as predictors of 30‐day readmission (Table 4). Having RIFLE: Injury or RIFLE: Failure carried an approximately 2‐fold increase in the odds of 30‐day rehospitalization (odds ratio: 1.95, 95% confidence interval: 1.302.93, P = 0.001) relative to having a RIFLE: None or RIFLE: Risk. Although having strong association with this outcome, harboring an ESBL organism or Bacteroides spp were both relatively infrequent events (3.3% ESBL and 3.2% Bacteroides spp). Infection with Escherichia coli and urine as the source of sepsis both appeared to be significantly protective against a readmission (Table 4). The model's discrimination was moderate (AUROC = 0.653) and its calibration adequate (Hosmer‐Lemeshow P = 0.907). (See Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article for the steps in the development of the final model.)

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| ESBL | 4.503 | 1.42914.190 | 0.010 |

| RIFLE: Injury or Failure (reference: RIFLE: None or Risk) | 1.951 | 1.2972.933 | 0.001 |

| Bacteroides spp | 2.044 | 1.0583.948 | 0.033 |

| Source: urine | 0.583 | 0.3470.979 | 0.041 |

| Escherichia coli | 0.494 | 0.2700.904 | 0.022 |

DISCUSSION

In this single‐center retrospective cohort study, nearly one‐third of survivors of culture‐positive severe sepsis or septic shock required a rehospitalization within 30 days of discharge from their index admission. Factors that contributed to a higher odds of rehospitalization were having mild‐to‐moderate AKI (RIFLE: Injury or RIFLE: Failure) and infection with ESBL organisms or Bacteroides spp, whereas urine as the source of sepsis and E coli as the pathogen appeared to be protective.

A recent study by Hua and colleagues examining the New York Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System for the years 2008 to 2010 noted a 16.2% overall rate of 30‐day rehospitalization among survivors of initial critical illness.[11] Just as we observed, Hua et al. concluded that development of AKI correlated with readmission. Because they relied on administrative data for their analysis, AKI was diagnosed when hemodialysis was utilized. Examining AKI using SCr changes, our findings add a layer of granularity to the relationship between AKI stages and early readmission. Specifically, we failed to detect any rise in the odds of rehospitalization when either very mild (RIFLE: Risk) or severe (RIFLE: Loss or RIFLE: ESKD) AKI was present. Only when either RIFLE: Injury or RIFLE: Failure developed did the odds of readmission rise. In addition to diverging definitions between our studies, differences in populations also likely yielded different results.[11] Although Hua et al. examined all admissions to the ICU regardless of the diagnosis or illness severity, our cohort consisted of only those ICU patients who survived culture‐positive severe sepsis/septic shock. Because AKI is a known risk factor for mortality in sepsis,[19] the potential for immortal time bias leaves a smaller pool of surviving patients with ESKD at risk for readmission. Regardless of the explanation, it may be prudent to focus on preventing AKI not only to improve survival, but also from the standpoint of diminishing the risk of an early readmission.

Four additional studies have examined the frequency of early readmissions among survivors of critical illness. Liu et al. noted 17.9% 30‐day rehospitalization rate among sepsis survivors.[12] Factors associated with the risk of early readmission included acute and chronic diseases burdens, index hospital LOS, and the need for the ICU in the index sepsis admission. In contrast to our cohort, all of whom were in the ICU during their index episode, less than two‐thirds of the entire population studied by Liu had required an ICU admission. Additionally, Liu's study did not specifically examine the potential impact of AKI or of microbiology on this outcome.

Prescott and coworkers examined healthcare utilization following an episode of severe sepsis.[13] Among other findings, they reported a 30‐day readmission rate of 26.5% among survivors. Although closer to our estimate, this study included all patients surviving a severe sepsis hospitalization, and not only those with a positive culture. These investigators did not examine predictors of readmission.[13]

Horkan et al. examined specifically whether there was an association between AKI and postdischarge outcomes, including 30‐day readmission risk, in a large cohort of patients who survived their critical illness.[20] In it they found that readmission risk ranged from 19% to 21%, depending on the extent of the AKI. Moreover, similar to our findings, they reported that in an adjusted analysis RIFLE: Injury and RIFLE: Failure were associated with a rise in the odds of a 30‐day rehospitalizaiton. In contrast to our study, Horkan et al. did detect an increase in the odds of this outcome associated with RIFLE: Risk. There are likely at least 3 reasons for this difference. First, we focused only on patients with severe sepsis or septic shock, whereas Horkan and colleagues included all critical illness survivors. Second, we were able to explore the impact of microbiology on this outcome. Third, Horkan's study included an order of magnitude more patients than did ours, thus making it more likely either to have the power to detect a true association that we may have lacked or to be more susceptible to type I error.

Finally, Goodwin and colleagues utilized 3 states' databases included in the Health Care and Utilization Project (HCUP) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to study frequency and risk factors for 30‐day readmission among survivors of severe sepsis.[21] Patients were identified based on the use of the severe sepsis (995.92) and septic shock (785.52). These authors found a 30‐day readmission rate of 26%. Although chronic renal disease, among several other factors, was associated with an increase in this risk, the data source did not permit these investigators to examine the impact of AKI on the outcomes. Similarly, HCUP data do not contain microbiology, a distinct difference from our analysis.

If clinicians are to pursue strategies to reduce the risk of an all‐cause 30‐day readmission, the key goal is not simply to identify all variables associated with readmission, but to focus on factors that are potentially modifiable. Although neither Hua nor Liu and their teams identified any additional factors that are potentially modifiable,[11, 12] in the present study, among the 5 factors we identified, the development of mild to moderate AKI during the index hospitalization may deserve stronger consideration for efforts at prevention. Although one cannot conclude automatically that preventing AKI in this population could mitigate some of the early rehospitalization risk, critically ill patients are frequently exposed to a multitude of nephrotoxic agents. Those caring for subjects with sepsis should reevaluate the risk‐benefit equation of these factors more cautiously and apply guideline‐recommended AKI prevention strategies more aggressively, particularly because a relatively minor change in SCr resulted in an excess risk of readmission.[22]

In addition to AKI, which is potentially modifiable, we identified several other clinical factors predictive of 30‐day readmission, which are admittedly not preventable. Thus, microbiology was predictive of this outcome, with E coli engendering fewer and Bacteroides spp and ESBL organisms more early rehospitalizations. Similarly, urine as the source of sepsis was associated with a lower risk for this endpoint.

Our study has a number of limitations. As a retrospective cohort, it is subject to bias, most notably a selection bias. Specifically, because the flagship hospital of the BJC HealthCare system is a referral center, it is possible that we did not capture all readmissions. However, generally, if a patient who receives healthcare within 1 of the BJC hospitals presents to a nonsystem hospital, that patient is nearly always transferred back into the integrated system because of issues of insurance coverage. Analysis of certain diagnosis‐related groups has indicated that 73% of all patients overall discharged from 4 of the large BJC system institutions who require a readmission within 30 days of discharge return to a BJC hospital (personal communication, Financial Analysis and Decision Support Department at BJC to Dr. Kollef May 12, 2015). Therefore, we may have misclassified the outcome in as many as 180 patients. The fact that our readmission rate was fully double that seen in Hua et al.'s and Liu et al.'s studies, and somewhat higher than that reported by Prescott et al., attests not only to the population differences, but also to the fact that we are unlikely to have missed a substantial percentage of readmissions.[11, 12, 13] Furthermore, to mitigate biases, we enrolled all consecutive patients meeting the predetermined criteria. Missing from our analysis are events that occurred between the index discharge and the readmission. Likewise, we were unable to obtain such potentially important variables as code status or outpatient mortality following discharge. These intervening factors, if included in subsequent studies, may increase the predictive power of the model. Because we relied on administrative coding to identify cases of severe sepsis and septic shock, it is possible that there is misclassification within our cohort. Recent studies indicate, however, that the Angus definition, used in our study, has high negative and positive predictive values for severe sepsis identification.[23] It is still possible that our cohort is skewed toward a more severely ill population, making our results less generalizable to the less severely ill septic patients.[24] The study was performed at a single healthcare system and included only cases of severe sepsis or septic shock that had a positive blood culture, and thus the findings may not be broadly generalizable either to patients without a positive blood culture or to institutions that do not resemble it.

In summary, we have demonstrated that survivors of culture‐positive severe sepsis or septic shock have a high rate of 30‐day rehospitalization. Because the US federal government's initiatives deem 30‐day readmissions to be a quality metric and penalize institutions with higher‐than average readmission rates, a high volume of critically ill patients with culture‐positive severe sepsis and septic shock may disproportionately put an institution at risk for such penalties. Unfortunately, not many of the determinants of readmission are amenable to prevention. As sepsis survival continues to improve, hospitals will need to concentrate their resources on coordinating care of these complex patients so as to improve both individual quality of life and the quality of care that they provide.

Disclosures

This study was supported by a research grant from Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Lexington, Massachusetts. Dr. Kollef's time was in part supported by the Barnes‐Jewish Hospital Foundation. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , et al; Sepsis Occurrence in Acutely Ill Patients Investigators. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:344–353

- , , , et al. Death in the United States, 2007. NCHS Data Brief. 2009;26:1–8.

- , , , et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1548–1564.

- , , , , , . Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310.

- , , , et al: Hospitalizations, costs, and outcomes of severe sepsis in the United States 2003 to 2007. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:754–761.

- , , , et al. Facing the challenge: decreasing case fatality rates in severe sepsis despite increasing hospitalization. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2555–2562.

- , , , et al. Rapid increase in hospitalization and mortality rates for severe sepsis in the United States: a trend analysis from 1993 to 2003. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1244–1250.

- , , , , . Two decades of mortality trends among patients with severe sepsis: a comparative meta‐analysis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:625–631.

- , , , et al. Preventing 30‐day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1095–1107.

- , . Trends in septicemia hospitalizations and readmissions in selected HCUP states, 2005 and 2010. HCUP Statistical Brief #161. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb161.pdf. Published September 2013, Accessed January 13, 2015.

- , , , . Early and late unplanned rehospitalizations for survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:430–438.

- , , , , , . Hospital readmission and healthcare utilization following sepsis in community settings. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:502–507.

- , , , , . Increased 1‐year healthcare use in survivors of severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:62–69.

- , , , , . Multi‐drug resistance, inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy and mortality in Gram‐negative severe sepsis and septic shock: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2014;18:596.

- , , . Does combination antimicrobial therapy reduce mortality in Gram‐negative bacteraemia? A meta‐analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:519–527.

- , , , et al. Multidrug‐resistant, extensively drug‐resistant and pandrug‐resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–281.

- , , , , ; Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative Workgroup. Acute renal failure—definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–R212.

- , , , . APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829.

- , , , et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73

- , , , , , . The association of acute kidney injury in the critically ill and postdischarge outcomes: a cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:354–364.

- , , , . Frequency, cost, and risk factors of readmissions among severe sepsis survivors. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:738–746.

- Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. Kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO). KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138. Available at: http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/KDIGO%20AKI%20Guideline.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2015.

- , , , , , . Validity of administrative data in recording sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):139.

- , , , , , . Severe sepsis cohorts derived from claims‐based strategies appear to be biased toward a more severely ill patient population. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:945–953.

Despite its decreasing mortality, sepsis remains a leading reason for intensive care unit (ICU) admission and is associated with crude mortality in excess of 25%.[1, 2] In the United States there are between 660,000 and 750,000 sepsis hospitalizations annually, with the direct costs surpassing $24 billion.[3, 4, 5] As mortality rates have begun to fall, attention has shifted to issues of morbidity and recovery, the intermediate and longer‐term consequences associated with survivorship, and how interventions made while the patient is acutely ill in the ICU alter later health outcomes.[3, 5, 6, 7, 8]

One area of particular interest is the need for healthcare utilization following an acute admission for sepsis, and specifically rehospitalization within 30 days of discharge. This outcome is important not just from the perspective of the patient's well‐being, but also from the point of view of healthcare financing. Through the establishment of Hospital Readmission Reduction Program, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have sharply reduced reimbursement to hospitals for excessive rates of 30‐day readmissions.[9]

For sepsis, little is known about such readmissions, and even less about how to prevent them. A handful of studies suggest that this rate is between 5% and 26%.[10, 11, 12, 13] Whereas some of these studies looked at some of the factors that impact readmissions,[11, 12] none examined the potential contribution of microbiology of sepsis to this outcome.

To explore these questions, we conducted a single‐center retrospective cohort study among critically ill patients admitted to the ICU with severe culture‐positive sepsis and/or septic shock and determined the rate of early posthospital discharge readmission. In addition, we sought to elucidate predictors of subsequent readmission.

METHODS

Study Design and Ethical Standards