User login

Knee pain • no popping • no previous trauma • Dx?

THE CASE

A 36-year-old man sought care at our family medicine clinic for knee pain that he’d had for the past year. He denied any previous injury or trauma to the knee. The pain affected the posterolateral left knee and was aggravated by squatting and deep flexion. Daily activities did not bother him, but skiing, golfing, mountain biking, and lifting weights worsened the pain. His pain had gradually become more severe and frequent. He denied any mechanical symptoms such as catching, popping, or locking.

Examination of his left knee demonstrated range of motion from 0 to 120 degrees; further flexion caused significant pain. McMurray and Thessaly tests were positive for posterolateral pain, particularly with knee flexion >120 degrees. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Standard x-rays of the left knee were normal. Our patient completed a month of physical therapy, but his symptoms did not improve.

THE DIAGNOSIS

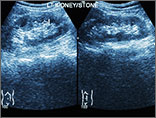

After the patient completed physical therapy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. The MRI did not reveal any left knee effusion, and the menisci, collateral ligaments, and cartilage surfaces were normal. And, while the cruciate ligaments were intact, a large pericruciate ganglion cyst was noted (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

DISCUSSION

Ganglion cysts are dense, encapsulated structures filled with clear viscous fluid that often arise adjacent to tendon sheaths or joint capsules, most commonly over the dorsum of the hand.1 Intra-articular ganglia involving the cruciate ligaments of the knee are relatively uncommon.2 The estimated prevalence of cruciate ligament ganglion cysts at arthroscopy is 0.2% to 1.9%; similar rates have been demonstrated with MRI.3-6 There are more reported cases of these cysts involving the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) compared to those affecting the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).2,6

Classification of these cysts is based on relative location with respect to the ligaments. Type 1 cysts originate anterior to the ACL; type 2, between the ACL and PCL; and type 3, posterior to the PCL.6,7 Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are more common in men, are typically discovered between age 20 and 40, and are usually incidental findings.8

The pathogenesis of ganglion cyst formation is unknown.1,6,7 The most widely accepted theory is that ganglion cysts result from mucinous degeneration of connective tissue in areas of repetitive stress.1,6,7 Other theories suggest hyaluronic acid production secondary to mesenchymal stem cell proliferation within the ligaments, synovial tissue herniation, or congenital translocation of synovial tissue as possible etiologies.2,6,7

Concurrent pathologies such as meniscal tears or chondral lesions may also be present; however, there is some disagreement as to what role, if any, antecedent trauma has in the pathogenesis of cyst formation.1,6 Several investigators have suggested that prior knee trauma is a likely risk factor.2,8,9

In most patients, cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are asymptomatic.7 The most common presenting symptom is nonspecific pain that is exacerbated by activity, such as stair climbing, squatting, or other activities that require extreme flexion or extension of the knee.6,9 Other possible symptoms include limited range of motion (extension block with ACL involvement, limited flexion with PCL lesions), a catching or locking sensation, instability, or joint line tenderness.5,6 A palpable mass on physical exam is not usually present.6 Some investigators suggest that larger lesions and those closer to the femoral ligamentous attachments are more likely to cause symptoms.5

Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts can be an easily overlooked source of a patient’s symptoms because they often mimic more common pathologies.2 The differential diagnosis of cruciate ligament ganglion cysts and posterior knee pain includes any other intra-articular cysts (eg, meniscal cysts), posterior meniscal tear, popliteus tendinopathy, or neoplasms (eg, hemangioma and synovial sarcoma).2,6

MRI is the best method of diagnosis

Because the symptoms of cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are variable and nonspecific, the diagnosis is rarely made on clinical grounds alone.1 The best method of evaluating suspected intra-articular pathologies such as cruciate ligament ganglion cysts is MRI.5,10

Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts typically follow fluid signal on all sequences, with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images.1,2,5,6 A pericruciate location with a multilocular appearance is usually sufficient evidence to make a diagnosis. However, solid or semi-solid pathologies (such as synovial cell sarcoma, synovial hemangioma, or synovial chondromatosis) can have similar signal intensity.

If necessary, intravenous contrast can be helpful; a lack of central contrast enhancement can differentiate ganglion cysts from other solid, enhancing, or partially enhancing lesions. Other diagnostic modalities, such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and diagnostic arthroscopy, are less practical and have a wide range of sensitivity and specificity.5,6,10

Arthroscopic excision is the treatment of choice

Asymptomatic cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are usually managed with clinical follow-up. For patients with symptomatic cysts, ultrasound- or CT-guided percutaneous cyst aspiration may temporarily improve symptoms, but recurrence rates have not been well studied.2,6,9,10 Additionally, accessibility to cysts in this location via these approaches is limited. Arthroscopic excision of the cyst is the treatment of choice for symptomatic cases.1,2,5,6,10

Our patient underwent arthroscopic cyst resection, which resulted in complete resolution of his symptoms. In 3 months, he returned to his regular physical activities with no pain or discomfort. One year later, he remained asymptomatic.

THE TAKEAWAY

Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are a rare cause of posterior knee pain. An MRI is the best diagnostic modality to evaluate and confirm the diagnosis, as well as rule out other pathologies. The treatment of choice for symptomatic cases is arthroscopic excision of the cyst.

1. Mao Y, Dong Q, Wang Y. Ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments: a series of 31 cases and review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:137.

2. Krudwig WK, Schulte KK, Heinemann C. Intra-articular ganglion cysts of the knee joint: a report of 85 cases and review of the literature. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:123-129.

3. Bergin D, Morrison WB, Carrino JA, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament ganglia and mucoid degeneration: coexistence and clinical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1283-1287.

4. Bui-Mansfield LT, Youngberg RA. Intraarticular ganglia of the knee: prevalence, presentation, etiology, and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:123-127.

5. Lunhao B, Yu S, Jiashi W. Diagnosis and treatment of ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:1053-1057.

6. Stein D, Cantlon M, Mackay B, et al. Cysts about the knee: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:469-479.

7. Zantop T, Rusch A, Hassenpflug J, et al. Intra-articular ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments: case report and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123:195-198.

8. Tsai TY, Yang YS, Tseng FJ, et al. Arthroscopic excision of ganglion cysts of the posterior cruciate ligaments using posterior trans-septal portal. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:95-99.

9. Huang GS, Lee CH, Chan WP, et al. Ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments. Acta Radiol. 2002;43:419-424.

10. Tyrrell PN, Cassar-Pullicino VN, McCall IW. Intra-articular ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1233-1238.

THE CASE

A 36-year-old man sought care at our family medicine clinic for knee pain that he’d had for the past year. He denied any previous injury or trauma to the knee. The pain affected the posterolateral left knee and was aggravated by squatting and deep flexion. Daily activities did not bother him, but skiing, golfing, mountain biking, and lifting weights worsened the pain. His pain had gradually become more severe and frequent. He denied any mechanical symptoms such as catching, popping, or locking.

Examination of his left knee demonstrated range of motion from 0 to 120 degrees; further flexion caused significant pain. McMurray and Thessaly tests were positive for posterolateral pain, particularly with knee flexion >120 degrees. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Standard x-rays of the left knee were normal. Our patient completed a month of physical therapy, but his symptoms did not improve.

THE DIAGNOSIS

After the patient completed physical therapy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. The MRI did not reveal any left knee effusion, and the menisci, collateral ligaments, and cartilage surfaces were normal. And, while the cruciate ligaments were intact, a large pericruciate ganglion cyst was noted (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

DISCUSSION

Ganglion cysts are dense, encapsulated structures filled with clear viscous fluid that often arise adjacent to tendon sheaths or joint capsules, most commonly over the dorsum of the hand.1 Intra-articular ganglia involving the cruciate ligaments of the knee are relatively uncommon.2 The estimated prevalence of cruciate ligament ganglion cysts at arthroscopy is 0.2% to 1.9%; similar rates have been demonstrated with MRI.3-6 There are more reported cases of these cysts involving the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) compared to those affecting the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).2,6

Classification of these cysts is based on relative location with respect to the ligaments. Type 1 cysts originate anterior to the ACL; type 2, between the ACL and PCL; and type 3, posterior to the PCL.6,7 Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are more common in men, are typically discovered between age 20 and 40, and are usually incidental findings.8

The pathogenesis of ganglion cyst formation is unknown.1,6,7 The most widely accepted theory is that ganglion cysts result from mucinous degeneration of connective tissue in areas of repetitive stress.1,6,7 Other theories suggest hyaluronic acid production secondary to mesenchymal stem cell proliferation within the ligaments, synovial tissue herniation, or congenital translocation of synovial tissue as possible etiologies.2,6,7

Concurrent pathologies such as meniscal tears or chondral lesions may also be present; however, there is some disagreement as to what role, if any, antecedent trauma has in the pathogenesis of cyst formation.1,6 Several investigators have suggested that prior knee trauma is a likely risk factor.2,8,9

In most patients, cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are asymptomatic.7 The most common presenting symptom is nonspecific pain that is exacerbated by activity, such as stair climbing, squatting, or other activities that require extreme flexion or extension of the knee.6,9 Other possible symptoms include limited range of motion (extension block with ACL involvement, limited flexion with PCL lesions), a catching or locking sensation, instability, or joint line tenderness.5,6 A palpable mass on physical exam is not usually present.6 Some investigators suggest that larger lesions and those closer to the femoral ligamentous attachments are more likely to cause symptoms.5

Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts can be an easily overlooked source of a patient’s symptoms because they often mimic more common pathologies.2 The differential diagnosis of cruciate ligament ganglion cysts and posterior knee pain includes any other intra-articular cysts (eg, meniscal cysts), posterior meniscal tear, popliteus tendinopathy, or neoplasms (eg, hemangioma and synovial sarcoma).2,6

MRI is the best method of diagnosis

Because the symptoms of cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are variable and nonspecific, the diagnosis is rarely made on clinical grounds alone.1 The best method of evaluating suspected intra-articular pathologies such as cruciate ligament ganglion cysts is MRI.5,10

Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts typically follow fluid signal on all sequences, with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images.1,2,5,6 A pericruciate location with a multilocular appearance is usually sufficient evidence to make a diagnosis. However, solid or semi-solid pathologies (such as synovial cell sarcoma, synovial hemangioma, or synovial chondromatosis) can have similar signal intensity.

If necessary, intravenous contrast can be helpful; a lack of central contrast enhancement can differentiate ganglion cysts from other solid, enhancing, or partially enhancing lesions. Other diagnostic modalities, such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and diagnostic arthroscopy, are less practical and have a wide range of sensitivity and specificity.5,6,10

Arthroscopic excision is the treatment of choice

Asymptomatic cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are usually managed with clinical follow-up. For patients with symptomatic cysts, ultrasound- or CT-guided percutaneous cyst aspiration may temporarily improve symptoms, but recurrence rates have not been well studied.2,6,9,10 Additionally, accessibility to cysts in this location via these approaches is limited. Arthroscopic excision of the cyst is the treatment of choice for symptomatic cases.1,2,5,6,10

Our patient underwent arthroscopic cyst resection, which resulted in complete resolution of his symptoms. In 3 months, he returned to his regular physical activities with no pain or discomfort. One year later, he remained asymptomatic.

THE TAKEAWAY

Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are a rare cause of posterior knee pain. An MRI is the best diagnostic modality to evaluate and confirm the diagnosis, as well as rule out other pathologies. The treatment of choice for symptomatic cases is arthroscopic excision of the cyst.

THE CASE

A 36-year-old man sought care at our family medicine clinic for knee pain that he’d had for the past year. He denied any previous injury or trauma to the knee. The pain affected the posterolateral left knee and was aggravated by squatting and deep flexion. Daily activities did not bother him, but skiing, golfing, mountain biking, and lifting weights worsened the pain. His pain had gradually become more severe and frequent. He denied any mechanical symptoms such as catching, popping, or locking.

Examination of his left knee demonstrated range of motion from 0 to 120 degrees; further flexion caused significant pain. McMurray and Thessaly tests were positive for posterolateral pain, particularly with knee flexion >120 degrees. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Standard x-rays of the left knee were normal. Our patient completed a month of physical therapy, but his symptoms did not improve.

THE DIAGNOSIS

After the patient completed physical therapy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. The MRI did not reveal any left knee effusion, and the menisci, collateral ligaments, and cartilage surfaces were normal. And, while the cruciate ligaments were intact, a large pericruciate ganglion cyst was noted (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

DISCUSSION

Ganglion cysts are dense, encapsulated structures filled with clear viscous fluid that often arise adjacent to tendon sheaths or joint capsules, most commonly over the dorsum of the hand.1 Intra-articular ganglia involving the cruciate ligaments of the knee are relatively uncommon.2 The estimated prevalence of cruciate ligament ganglion cysts at arthroscopy is 0.2% to 1.9%; similar rates have been demonstrated with MRI.3-6 There are more reported cases of these cysts involving the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) compared to those affecting the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).2,6

Classification of these cysts is based on relative location with respect to the ligaments. Type 1 cysts originate anterior to the ACL; type 2, between the ACL and PCL; and type 3, posterior to the PCL.6,7 Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are more common in men, are typically discovered between age 20 and 40, and are usually incidental findings.8

The pathogenesis of ganglion cyst formation is unknown.1,6,7 The most widely accepted theory is that ganglion cysts result from mucinous degeneration of connective tissue in areas of repetitive stress.1,6,7 Other theories suggest hyaluronic acid production secondary to mesenchymal stem cell proliferation within the ligaments, synovial tissue herniation, or congenital translocation of synovial tissue as possible etiologies.2,6,7

Concurrent pathologies such as meniscal tears or chondral lesions may also be present; however, there is some disagreement as to what role, if any, antecedent trauma has in the pathogenesis of cyst formation.1,6 Several investigators have suggested that prior knee trauma is a likely risk factor.2,8,9

In most patients, cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are asymptomatic.7 The most common presenting symptom is nonspecific pain that is exacerbated by activity, such as stair climbing, squatting, or other activities that require extreme flexion or extension of the knee.6,9 Other possible symptoms include limited range of motion (extension block with ACL involvement, limited flexion with PCL lesions), a catching or locking sensation, instability, or joint line tenderness.5,6 A palpable mass on physical exam is not usually present.6 Some investigators suggest that larger lesions and those closer to the femoral ligamentous attachments are more likely to cause symptoms.5

Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts can be an easily overlooked source of a patient’s symptoms because they often mimic more common pathologies.2 The differential diagnosis of cruciate ligament ganglion cysts and posterior knee pain includes any other intra-articular cysts (eg, meniscal cysts), posterior meniscal tear, popliteus tendinopathy, or neoplasms (eg, hemangioma and synovial sarcoma).2,6

MRI is the best method of diagnosis

Because the symptoms of cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are variable and nonspecific, the diagnosis is rarely made on clinical grounds alone.1 The best method of evaluating suspected intra-articular pathologies such as cruciate ligament ganglion cysts is MRI.5,10

Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts typically follow fluid signal on all sequences, with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images.1,2,5,6 A pericruciate location with a multilocular appearance is usually sufficient evidence to make a diagnosis. However, solid or semi-solid pathologies (such as synovial cell sarcoma, synovial hemangioma, or synovial chondromatosis) can have similar signal intensity.

If necessary, intravenous contrast can be helpful; a lack of central contrast enhancement can differentiate ganglion cysts from other solid, enhancing, or partially enhancing lesions. Other diagnostic modalities, such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and diagnostic arthroscopy, are less practical and have a wide range of sensitivity and specificity.5,6,10

Arthroscopic excision is the treatment of choice

Asymptomatic cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are usually managed with clinical follow-up. For patients with symptomatic cysts, ultrasound- or CT-guided percutaneous cyst aspiration may temporarily improve symptoms, but recurrence rates have not been well studied.2,6,9,10 Additionally, accessibility to cysts in this location via these approaches is limited. Arthroscopic excision of the cyst is the treatment of choice for symptomatic cases.1,2,5,6,10

Our patient underwent arthroscopic cyst resection, which resulted in complete resolution of his symptoms. In 3 months, he returned to his regular physical activities with no pain or discomfort. One year later, he remained asymptomatic.

THE TAKEAWAY

Cruciate ligament ganglion cysts are a rare cause of posterior knee pain. An MRI is the best diagnostic modality to evaluate and confirm the diagnosis, as well as rule out other pathologies. The treatment of choice for symptomatic cases is arthroscopic excision of the cyst.

1. Mao Y, Dong Q, Wang Y. Ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments: a series of 31 cases and review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:137.

2. Krudwig WK, Schulte KK, Heinemann C. Intra-articular ganglion cysts of the knee joint: a report of 85 cases and review of the literature. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:123-129.

3. Bergin D, Morrison WB, Carrino JA, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament ganglia and mucoid degeneration: coexistence and clinical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1283-1287.

4. Bui-Mansfield LT, Youngberg RA. Intraarticular ganglia of the knee: prevalence, presentation, etiology, and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:123-127.

5. Lunhao B, Yu S, Jiashi W. Diagnosis and treatment of ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:1053-1057.

6. Stein D, Cantlon M, Mackay B, et al. Cysts about the knee: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:469-479.

7. Zantop T, Rusch A, Hassenpflug J, et al. Intra-articular ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments: case report and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123:195-198.

8. Tsai TY, Yang YS, Tseng FJ, et al. Arthroscopic excision of ganglion cysts of the posterior cruciate ligaments using posterior trans-septal portal. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:95-99.

9. Huang GS, Lee CH, Chan WP, et al. Ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments. Acta Radiol. 2002;43:419-424.

10. Tyrrell PN, Cassar-Pullicino VN, McCall IW. Intra-articular ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1233-1238.

1. Mao Y, Dong Q, Wang Y. Ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments: a series of 31 cases and review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:137.

2. Krudwig WK, Schulte KK, Heinemann C. Intra-articular ganglion cysts of the knee joint: a report of 85 cases and review of the literature. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:123-129.

3. Bergin D, Morrison WB, Carrino JA, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament ganglia and mucoid degeneration: coexistence and clinical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1283-1287.

4. Bui-Mansfield LT, Youngberg RA. Intraarticular ganglia of the knee: prevalence, presentation, etiology, and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:123-127.

5. Lunhao B, Yu S, Jiashi W. Diagnosis and treatment of ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:1053-1057.

6. Stein D, Cantlon M, Mackay B, et al. Cysts about the knee: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:469-479.

7. Zantop T, Rusch A, Hassenpflug J, et al. Intra-articular ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments: case report and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123:195-198.

8. Tsai TY, Yang YS, Tseng FJ, et al. Arthroscopic excision of ganglion cysts of the posterior cruciate ligaments using posterior trans-septal portal. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:95-99.

9. Huang GS, Lee CH, Chan WP, et al. Ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments. Acta Radiol. 2002;43:419-424.

10. Tyrrell PN, Cassar-Pullicino VN, McCall IW. Intra-articular ganglion cysts of the cruciate ligaments. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1233-1238.

These umbilical lesions weren't granulomas after all

THE CASES

CASE 1 › A 15-month-old boy was brought to our center for plastic surgery after being referred by his general practitioner (GP). The patient had a non-healing lesion on his umbilicus that had been present since birth. It had remained the same size, but bled occasionally. The GP initially presumed the lesion was a granuloma and treated it with silver nitrate cautery, but this did not eradicate it.

After talking with the boy’s mother further, we learned that there had been a constant oozing from the area since birth and that the lesion protruded slightly from the abdomen when the child cried. The boy had congenital heart disease, but his bowel and genitourinary history were normal. A clinical examination revealed pink, moist tissue herniating from the umbilicus with surrounding abdominal fullness when the boy stood up (FIGURE 1A). An ultrasound showed a focal 19 x 7 mm complex area around the umbilicus with no definite track. The lesion was surgically removed. Histology revealed a completely excised vitellointestinal duct remnant.

CASE 2 › A 6-year-old boy with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder was brought to our clinic with a non-healing umbilical lesion after being referred by his GP. The lesion had been present since birth and had failed to resolve despite several attempts to treat it with silver nitrate cautery. Clinically, the patient appeared to have a granulomatous umbilical polyp (FIGURE 1B). The patient underwent surgical excision of the lesion. Histological analysis revealed a completely excised vitellointestinal duct remnant (FIGURE 2).

DISCUSSION

The vitellointestinal duct (VID), also called the omphalomesenteric duct (OMD), connects the alimentary canal and the yolk sac in early embryogenesis. Failure of involution of the duct results in abnormalities such as Meckel’s diverticulum, cysts, and polyps.

VID anomalies occur in approximately 2% of newborns; a small percentage of these have patent connections to the intestine.1 Parents are often the first to notice the abnormality and will typically see a reddish protrusion around the umbilicus or a persistent serous discharge around the umbilicus soon after birth.

VID remnants are similar in presentation to benign granulomas or granulation tissue, which are benign lesions that present in the first few weeks of life. Granulomas are reddish in color, bleed minimally when irritated by trauma, and respond well to silver nitrate cautery.2 When the lesion fails to respond to treatment, an alternative diagnosis should be investigated further.

Ultrasonography is the best way to evaluate a suspected VID remnant

A suspected VID remnant should first be assessed with ultrasonography to determine the extent of the remnant and guide surgical treatment. Ultrasonography can also delineate the relationship of these congenital remnants with the umbilicus and bladder.3

Potential complications that can arise from these lesions include an intestinal hernia, intussusception, volvulus, abdominal pain, or a persistent discharge that can lead to infection.3 Mortality following complications is significantly high.4

Although the etiology of patent VIDs and their remnants remains unknown, the presence of such ducts is associated with other congenital anomalies, including Down Syndrome, structural cardiac malformation, conduction abnormalities, and cleft lip and palate.5-7 Therefore, additional history taking and examinations may be required to identify these associated pathologies. In Case 1, the 15-month-old boy had congenital heart disease.

Surgical excision will prevent complications

A simple surgical excision should be performed for VID remnants. The prognosis is excellent when such procedures are performed in the non-acute setting. Some debate exists as to whether all remnants require formal abdominal exploration.8,9

Treatment of patent VIDs requires surgical excision of the duct, with or without a segment of the small bowel, to obliterate the connection.10 Reconstruction of the umbilicus is then performed, depending on the surgical technique used.

Our patients both made complete recoveries following their surgeries with resolution of their symptoms.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consider a VID remnant as part of the differential diagnosis for any patient who has what appears to be a granulomatous umbilical lesion. Order ultrasonography to evaluate a suspected VID, especially for lesions that fail to respond to 2 or 3 silver nitrate treatments. Surgical excision of a VID remnant is usually curative.

1. Vane DW, West KW, Grosfeld JL. Vitelline duct anomalies. Experience with 217 childhood cases. Arch Surg. 1987;122:542-547.

2. Piparsaliya S, Joshi M, Rajput N, et al. Patent vitellointestinal duct: A close differential diagnosis of umbilical granuloma: A case report and review of literature. Surgical Science. 2011;2:134-136.

3. Khati NJ, Enquist EG, Javitt MC. Imaging of the umbilicus and periumbilical region. Radiographics. 1998;18:413-431.

4. Yamada T, Seiki Y, Ueda M, et al. Patent omphalomesenteric duct: a case report and review of Japanese literature. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;15:229-236.

5. Martin RH, Doublestein GL, Jarvis MR. Concurrent ectopic pregnancy, Meckel’s diverticulum with vitelline duct remnant, cecal volvulus, and congenital complete heart block: report of a case. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1986;86:589-591.

6. Elebute EA, Ransome-Kuti O. Patent vitello-intestinal duct with ileal prolapse. Arch Surg. 1965;91:456-460.

7. Blair SP, Beasley SW. Intussusception of vitello-intestinal tract through an exomphalos in trisomy 13. Pediatric Surgery International. 1989;4:422-423.

8. Kutin ND, Allen JE, Jewett TC. The umbilical polyp. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:741-744.

9. Pacilli M, Sebire NJ, Maritsi D, et al. Umbilical polyp in infants and children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2007;17:397-399.

10. Storms P, Pexsters J, Vandekerkhof J. Small omphalocele with ileal prolapse through a patent omphalomesenteric duct. A case report and review of literature. Acta Chir Belg. 1988;88:392-394.

THE CASES

CASE 1 › A 15-month-old boy was brought to our center for plastic surgery after being referred by his general practitioner (GP). The patient had a non-healing lesion on his umbilicus that had been present since birth. It had remained the same size, but bled occasionally. The GP initially presumed the lesion was a granuloma and treated it with silver nitrate cautery, but this did not eradicate it.

After talking with the boy’s mother further, we learned that there had been a constant oozing from the area since birth and that the lesion protruded slightly from the abdomen when the child cried. The boy had congenital heart disease, but his bowel and genitourinary history were normal. A clinical examination revealed pink, moist tissue herniating from the umbilicus with surrounding abdominal fullness when the boy stood up (FIGURE 1A). An ultrasound showed a focal 19 x 7 mm complex area around the umbilicus with no definite track. The lesion was surgically removed. Histology revealed a completely excised vitellointestinal duct remnant.

CASE 2 › A 6-year-old boy with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder was brought to our clinic with a non-healing umbilical lesion after being referred by his GP. The lesion had been present since birth and had failed to resolve despite several attempts to treat it with silver nitrate cautery. Clinically, the patient appeared to have a granulomatous umbilical polyp (FIGURE 1B). The patient underwent surgical excision of the lesion. Histological analysis revealed a completely excised vitellointestinal duct remnant (FIGURE 2).

DISCUSSION

The vitellointestinal duct (VID), also called the omphalomesenteric duct (OMD), connects the alimentary canal and the yolk sac in early embryogenesis. Failure of involution of the duct results in abnormalities such as Meckel’s diverticulum, cysts, and polyps.

VID anomalies occur in approximately 2% of newborns; a small percentage of these have patent connections to the intestine.1 Parents are often the first to notice the abnormality and will typically see a reddish protrusion around the umbilicus or a persistent serous discharge around the umbilicus soon after birth.

VID remnants are similar in presentation to benign granulomas or granulation tissue, which are benign lesions that present in the first few weeks of life. Granulomas are reddish in color, bleed minimally when irritated by trauma, and respond well to silver nitrate cautery.2 When the lesion fails to respond to treatment, an alternative diagnosis should be investigated further.

Ultrasonography is the best way to evaluate a suspected VID remnant

A suspected VID remnant should first be assessed with ultrasonography to determine the extent of the remnant and guide surgical treatment. Ultrasonography can also delineate the relationship of these congenital remnants with the umbilicus and bladder.3

Potential complications that can arise from these lesions include an intestinal hernia, intussusception, volvulus, abdominal pain, or a persistent discharge that can lead to infection.3 Mortality following complications is significantly high.4

Although the etiology of patent VIDs and their remnants remains unknown, the presence of such ducts is associated with other congenital anomalies, including Down Syndrome, structural cardiac malformation, conduction abnormalities, and cleft lip and palate.5-7 Therefore, additional history taking and examinations may be required to identify these associated pathologies. In Case 1, the 15-month-old boy had congenital heart disease.

Surgical excision will prevent complications

A simple surgical excision should be performed for VID remnants. The prognosis is excellent when such procedures are performed in the non-acute setting. Some debate exists as to whether all remnants require formal abdominal exploration.8,9

Treatment of patent VIDs requires surgical excision of the duct, with or without a segment of the small bowel, to obliterate the connection.10 Reconstruction of the umbilicus is then performed, depending on the surgical technique used.

Our patients both made complete recoveries following their surgeries with resolution of their symptoms.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consider a VID remnant as part of the differential diagnosis for any patient who has what appears to be a granulomatous umbilical lesion. Order ultrasonography to evaluate a suspected VID, especially for lesions that fail to respond to 2 or 3 silver nitrate treatments. Surgical excision of a VID remnant is usually curative.

THE CASES

CASE 1 › A 15-month-old boy was brought to our center for plastic surgery after being referred by his general practitioner (GP). The patient had a non-healing lesion on his umbilicus that had been present since birth. It had remained the same size, but bled occasionally. The GP initially presumed the lesion was a granuloma and treated it with silver nitrate cautery, but this did not eradicate it.

After talking with the boy’s mother further, we learned that there had been a constant oozing from the area since birth and that the lesion protruded slightly from the abdomen when the child cried. The boy had congenital heart disease, but his bowel and genitourinary history were normal. A clinical examination revealed pink, moist tissue herniating from the umbilicus with surrounding abdominal fullness when the boy stood up (FIGURE 1A). An ultrasound showed a focal 19 x 7 mm complex area around the umbilicus with no definite track. The lesion was surgically removed. Histology revealed a completely excised vitellointestinal duct remnant.

CASE 2 › A 6-year-old boy with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder was brought to our clinic with a non-healing umbilical lesion after being referred by his GP. The lesion had been present since birth and had failed to resolve despite several attempts to treat it with silver nitrate cautery. Clinically, the patient appeared to have a granulomatous umbilical polyp (FIGURE 1B). The patient underwent surgical excision of the lesion. Histological analysis revealed a completely excised vitellointestinal duct remnant (FIGURE 2).

DISCUSSION

The vitellointestinal duct (VID), also called the omphalomesenteric duct (OMD), connects the alimentary canal and the yolk sac in early embryogenesis. Failure of involution of the duct results in abnormalities such as Meckel’s diverticulum, cysts, and polyps.

VID anomalies occur in approximately 2% of newborns; a small percentage of these have patent connections to the intestine.1 Parents are often the first to notice the abnormality and will typically see a reddish protrusion around the umbilicus or a persistent serous discharge around the umbilicus soon after birth.

VID remnants are similar in presentation to benign granulomas or granulation tissue, which are benign lesions that present in the first few weeks of life. Granulomas are reddish in color, bleed minimally when irritated by trauma, and respond well to silver nitrate cautery.2 When the lesion fails to respond to treatment, an alternative diagnosis should be investigated further.

Ultrasonography is the best way to evaluate a suspected VID remnant

A suspected VID remnant should first be assessed with ultrasonography to determine the extent of the remnant and guide surgical treatment. Ultrasonography can also delineate the relationship of these congenital remnants with the umbilicus and bladder.3

Potential complications that can arise from these lesions include an intestinal hernia, intussusception, volvulus, abdominal pain, or a persistent discharge that can lead to infection.3 Mortality following complications is significantly high.4

Although the etiology of patent VIDs and their remnants remains unknown, the presence of such ducts is associated with other congenital anomalies, including Down Syndrome, structural cardiac malformation, conduction abnormalities, and cleft lip and palate.5-7 Therefore, additional history taking and examinations may be required to identify these associated pathologies. In Case 1, the 15-month-old boy had congenital heart disease.

Surgical excision will prevent complications

A simple surgical excision should be performed for VID remnants. The prognosis is excellent when such procedures are performed in the non-acute setting. Some debate exists as to whether all remnants require formal abdominal exploration.8,9

Treatment of patent VIDs requires surgical excision of the duct, with or without a segment of the small bowel, to obliterate the connection.10 Reconstruction of the umbilicus is then performed, depending on the surgical technique used.

Our patients both made complete recoveries following their surgeries with resolution of their symptoms.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consider a VID remnant as part of the differential diagnosis for any patient who has what appears to be a granulomatous umbilical lesion. Order ultrasonography to evaluate a suspected VID, especially for lesions that fail to respond to 2 or 3 silver nitrate treatments. Surgical excision of a VID remnant is usually curative.

1. Vane DW, West KW, Grosfeld JL. Vitelline duct anomalies. Experience with 217 childhood cases. Arch Surg. 1987;122:542-547.

2. Piparsaliya S, Joshi M, Rajput N, et al. Patent vitellointestinal duct: A close differential diagnosis of umbilical granuloma: A case report and review of literature. Surgical Science. 2011;2:134-136.

3. Khati NJ, Enquist EG, Javitt MC. Imaging of the umbilicus and periumbilical region. Radiographics. 1998;18:413-431.

4. Yamada T, Seiki Y, Ueda M, et al. Patent omphalomesenteric duct: a case report and review of Japanese literature. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;15:229-236.

5. Martin RH, Doublestein GL, Jarvis MR. Concurrent ectopic pregnancy, Meckel’s diverticulum with vitelline duct remnant, cecal volvulus, and congenital complete heart block: report of a case. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1986;86:589-591.

6. Elebute EA, Ransome-Kuti O. Patent vitello-intestinal duct with ileal prolapse. Arch Surg. 1965;91:456-460.

7. Blair SP, Beasley SW. Intussusception of vitello-intestinal tract through an exomphalos in trisomy 13. Pediatric Surgery International. 1989;4:422-423.

8. Kutin ND, Allen JE, Jewett TC. The umbilical polyp. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:741-744.

9. Pacilli M, Sebire NJ, Maritsi D, et al. Umbilical polyp in infants and children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2007;17:397-399.

10. Storms P, Pexsters J, Vandekerkhof J. Small omphalocele with ileal prolapse through a patent omphalomesenteric duct. A case report and review of literature. Acta Chir Belg. 1988;88:392-394.

1. Vane DW, West KW, Grosfeld JL. Vitelline duct anomalies. Experience with 217 childhood cases. Arch Surg. 1987;122:542-547.

2. Piparsaliya S, Joshi M, Rajput N, et al. Patent vitellointestinal duct: A close differential diagnosis of umbilical granuloma: A case report and review of literature. Surgical Science. 2011;2:134-136.

3. Khati NJ, Enquist EG, Javitt MC. Imaging of the umbilicus and periumbilical region. Radiographics. 1998;18:413-431.

4. Yamada T, Seiki Y, Ueda M, et al. Patent omphalomesenteric duct: a case report and review of Japanese literature. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;15:229-236.

5. Martin RH, Doublestein GL, Jarvis MR. Concurrent ectopic pregnancy, Meckel’s diverticulum with vitelline duct remnant, cecal volvulus, and congenital complete heart block: report of a case. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1986;86:589-591.

6. Elebute EA, Ransome-Kuti O. Patent vitello-intestinal duct with ileal prolapse. Arch Surg. 1965;91:456-460.

7. Blair SP, Beasley SW. Intussusception of vitello-intestinal tract through an exomphalos in trisomy 13. Pediatric Surgery International. 1989;4:422-423.

8. Kutin ND, Allen JE, Jewett TC. The umbilical polyp. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:741-744.

9. Pacilli M, Sebire NJ, Maritsi D, et al. Umbilical polyp in infants and children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2007;17:397-399.

10. Storms P, Pexsters J, Vandekerkhof J. Small omphalocele with ileal prolapse through a patent omphalomesenteric duct. A case report and review of literature. Acta Chir Belg. 1988;88:392-394.

The solution to EHR woes: A team-based care model

For some time, electronic health records (EHRs) have been the focus of many articles (“EHR use and patient satisfaction: What we learned.” J Fam Pract. 2015;64:687-696) and the source of great debate (and frustration) in the health care community. But there’s a logical solution to the dilemmas created by EHRs: A team-based care model.1

A fundamental principle of team-based care is that all members of the team work at the top of their skill set. So, with that in mind, most of the duties of EHR management should be delegated to other team members, rather than to the physicians. In our system, every physician works with 2 other people—certified medical assistants or licensed practical nurses—who help with standing orders, protocols, templates, and many of the EHR duties, including a significant portion of team documentation. They do this while recognizing and respecting guidelines from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other payers. That leaves the physicians and advanced practice clinicians the time they need to focus on the patient during the visit.

Not surprisingly, patient satisfaction, staff satisfaction, and quality measures are all improving with this model of care. It is proving financially viable, as well. This model may well be the future of health care delivery for office-based practices.2

Jim Jerzak, MD

Green Bay, Wis

1. Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

2. Ghorob A, Bodenheimer T. Building teams in primary care: A practical guide. Fam Syst Health. 2015;33:182-192.

For some time, electronic health records (EHRs) have been the focus of many articles (“EHR use and patient satisfaction: What we learned.” J Fam Pract. 2015;64:687-696) and the source of great debate (and frustration) in the health care community. But there’s a logical solution to the dilemmas created by EHRs: A team-based care model.1

A fundamental principle of team-based care is that all members of the team work at the top of their skill set. So, with that in mind, most of the duties of EHR management should be delegated to other team members, rather than to the physicians. In our system, every physician works with 2 other people—certified medical assistants or licensed practical nurses—who help with standing orders, protocols, templates, and many of the EHR duties, including a significant portion of team documentation. They do this while recognizing and respecting guidelines from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other payers. That leaves the physicians and advanced practice clinicians the time they need to focus on the patient during the visit.

Not surprisingly, patient satisfaction, staff satisfaction, and quality measures are all improving with this model of care. It is proving financially viable, as well. This model may well be the future of health care delivery for office-based practices.2

Jim Jerzak, MD

Green Bay, Wis

1. Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

2. Ghorob A, Bodenheimer T. Building teams in primary care: A practical guide. Fam Syst Health. 2015;33:182-192.

For some time, electronic health records (EHRs) have been the focus of many articles (“EHR use and patient satisfaction: What we learned.” J Fam Pract. 2015;64:687-696) and the source of great debate (and frustration) in the health care community. But there’s a logical solution to the dilemmas created by EHRs: A team-based care model.1

A fundamental principle of team-based care is that all members of the team work at the top of their skill set. So, with that in mind, most of the duties of EHR management should be delegated to other team members, rather than to the physicians. In our system, every physician works with 2 other people—certified medical assistants or licensed practical nurses—who help with standing orders, protocols, templates, and many of the EHR duties, including a significant portion of team documentation. They do this while recognizing and respecting guidelines from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other payers. That leaves the physicians and advanced practice clinicians the time they need to focus on the patient during the visit.

Not surprisingly, patient satisfaction, staff satisfaction, and quality measures are all improving with this model of care. It is proving financially viable, as well. This model may well be the future of health care delivery for office-based practices.2

Jim Jerzak, MD

Green Bay, Wis

1. Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

2. Ghorob A, Bodenheimer T. Building teams in primary care: A practical guide. Fam Syst Health. 2015;33:182-192.

Personality disorders: A measured response

› Maintain a high index of suspicion for personality disorders (PDs) in patients who appear to be “difficult,” and take care to distinguish these diagnoses from primary mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. C

› Refer patients with PDs for psychotherapy, as it is considered the mainstay of treatment—particularly for borderline PD. B

› Use pharmacotherapy judiciously as an adjunctive treatment for PD. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Personality disorders (PDs) are common, affecting up to 15% of US adults, and are associated with comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions and increased utilization of health care resources.1,2 Having a basic understanding of these patterns of thinking and behaving can help family physicians (FPs) identify specific PD diagnoses, ensure appropriate treatment, and reduce the frustration that arises when an individual is viewed as a “difficult patient.”

Here we describe the diagnostic features of the disorders in the 3 major clusters of PDs and review an effective approach to the management of the most common disorder in each cluster, using a case study patient.

Defense mechanisms offer clues that your patient may have a PD

Personality is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviors that is relatively stable across time and in different situations. Such traits comprise an individual’s inherent makeup.1 PDs are diagnosed when an individual’s personality traits create significant distress or impairment in daily functioning. Specifically, PDs have a negative impact on cognition, affect, interpersonal relationships, and/or impulse control.1

One of the ways people alleviate distress is by using defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms are unconscious mental processes that individuals use to resolve conflicts, and thereby reduce anxiety and depression on a conscious level. Taken alone, defense mechanisms are not pathologic, but they may become maladaptive in certain stressful circumstances, such as when receiving medical treatment. Recognizing patterns of chronic use of certain defense mechanisms may be a clue that your patient has a PD. TABLE 13,4 and TABLE 23,4 provide an overview of common defense mechanisms used by patients with PDs.

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) organizes PDs into 3 clusters based on similar and often overlapping symptoms.1TABLE 31 provides a brief summary of the characteristic features of each disorder in these clusters.

Cluster A: Odd, eccentric

Patients with one of these disorders are odd, eccentric, or bizarre in their behavior and thinking. There appears to be a genetic link between cluster A PDs (especially schizotypal) and schizophrenia.5 These patients rarely seek treatment for their disorder because they have limited insight into their maladaptive traits.5,6

CASE 1 › Daniel A, age 57, has hypertension and hyperlipidemia and comes in to see his FP for a 6-month follow-up appointment. He never misses appointments, but has a history of poor adherence with prescribed medications. He enjoys his discussions with you in the office, although he often perseverates on conspiracy theories. He lives alone and has never been married. He believes that some of the previously prescribed medications, including a statin and a thiazide diuretic, were interfering with the absorption of “positive nutrients” in his diet. He also refuses to take the generic form of a statin, which he believes was adulterated by the government to be sold at lower cost.

Mr. A demonstrates the odd and eccentric beliefs that characterize schizotypal personality disorder. How can his FP best help him adhere to his medication regimen? (For the answer, click here.)

Schizotypal personality disorder shares certain disturbances of thought with schizophrenia, and is believed to exist on a spectrum with other primary psychotic disorders. Support for this theory comes from the higher rates of schizotypal PD among family members of patients with schizophrenia. There is a genetic component to the disorder.3,5,6

Clinically, these patients appear odd and eccentric with unusual beliefs. They may have a fascination with magic, clairvoyance, telepathy, or other such notions.1,5 Although the perceptual disturbances are unusual and often bizarre, they are not frank delusions: patients with schizotypal PD are willing to consider alternative explanations for their beliefs and can engage in rational discussion. Cognitive deficits, particularly of memory and attention, are common and distressing to patients. Frequently, the presenting complaint is depression and anxiety due to the emotional discord and isolation from others.1,3,5,6

Continue to cluster B >>

Cluster B: Dramatic, erratic

Patients with cluster B PDs are dramatic, excessively emotional, confrontational, erratic, and impulsive in their behaviors.1 They often have comorbid mood and anxiety disorders, as well as a disproportionately high co-occurrence of functional disorders.3,7 Their rates of health care utilization can be substantial. Because individuals with one of these PDs sometimes exhibit reckless and impulsive behavior, physicians should be aware these patients have a high risk of physical injuries (fights, accidents, self-injurious behavior), suicide attempts, risky sexual behaviors, and unplanned pregnancy.8,9

CASE 2 › Sheryl B is a 34-year-old new patient with a history of irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, depression, and anxiety who shows up for her appointment an hour late. She is upset and blames the office scheduler for not reminding her of the appointment. She brings a list of medications from her previous physician that includes sertraline, clonazepam, gabapentin, oxycodone, and as-needed alprazolam. She insists that her physician increase the dose of the benzodiazepines.

A review of her medical history reveals diagnoses of anxiety, bipolar disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Ms. B has also engaged in superficial cutting since adolescence, often triggered by arguments with her boyfriend. Currently, she attributes her anxiety and pain to not receiving the “correct medications” because of her transition from a previous physician who “knew her better than any other doctor.” After the FP explains to Ms. B that he would have to carefully review her case before continuing to prescribe benzodiazepines, she becomes tearful and argumentative, proclaiming, “You won’t give me the only thing that will help me because you want me to be miserable!”

Ms. B exhibits many cluster B personality traits consistent with borderline PD. How should the FP respond to her claims? (For the answer, click here.)

Borderline PD is the most studied of the PDs. It can be a stigmatizing diagnosis, and even experienced psychiatrists may hesitate to inform patients of this diagnosis.10 Patients with borderline PD may be erroneously diagnosed with bipolar disorder, treatment-resistant depression, or posttraumatic stress disorder because of a complicated clinical presentation, physician unfamiliarity with diagnostic criteria, or the presence of genuine comorbid conditions.3,11

The etiology of this disorder appears to be multifactorial, and includes genetic predisposition, disruptive parent-child relationships (especially separation), and, often, past sexual or physical trauma.9,12

Predominant clinical features include emotional lability, efforts to avoid abandonment, extremes of idealization and devaluation, unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, and impulsivity.1 Characteristically, these patients also engage in self-injurious behaviors.13,14 Common defense mechanisms used by patients with borderline PD include splitting (viewing others as either all good or all bad), acting out (yelling, agitation, or violence), and passive aggression (TABLE 13,4).

Cluster C: Anxious, fearful

Individuals with cluster C PDs appear anxious, fearful, and worried. They have features that overlap with anxiety disorders.15

CASE 3 › Judy C is a 40-year-old lawyer with a history of gastroesophageal reflux disorder, hypertension, and anxiety who presents for a 3-week follow-up visit after starting sertraline. The patient describes herself as a perfectionist who has increased work-related stress recently because she has to “do extra work for my colleagues who don’t know how to get things done right.” She recently fired her assistant for “not understanding my filing system.” She appears formal and serious, often looking at her watch during the evaluation.

Ms. C demonstrates a pattern of perfectionism, formality, and rigidity in thought and behavior characteristic of obsessive-compulsive PD. What treatment should her physician recommend? (For the answer, click here.)

Obsessive-compulsive PD. Although this disorder is associated with significant anxiety, patients often view the specific traits of obsessive-compulsive PD, such as perfectionism, as desirable. Neurotic defense mechanisms are common, especially rationalization, intellectualization, and isolation of affect (TABLE 23,4). These patients appear formal, rigid, and serious, and are preoccupied with rules and orderliness to achieve perfection.1 Significant anxiety often arises from fear of making mistakes and ruminating on decision-making.1,11,15

Although some overlap exists between obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and obsessive-compulsive PD, patients with OCD exhibit distinct obsessions and associated compulsive behavior, whereas those with obsessive-compulsive PD do not.1

In terms of treatment, it is generally appropriate to recognize the 2 conditions as distinct entities.15 OCD responds well to cognitive behavioral therapies and high-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).16 In contrast, there is little data that suggests antidepressants are effective for obsessive-compulsive PD, and treatment is aimed at addressing comorbid anxiety with psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, if needed.11,15

Continue to psychotherapy for PD is the first-line treatment >>

Psychotherapy for PD is the first-line treatment

Psychotherapy is the most effective treatment for PDs.11,17,18 Several psychotherapies are used to treat these disorders, including dialectical behavioral therapy, schema therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). A recent study demonstrated the superiority of several evidence-based psychotherapies for PD compared to treatment-as-usual.17 Even more promising is that certain benefits have been demonstrated when psychotherapy is provided by clinicians without advanced mental health training.19-21 However, the benefits of therapies for specific disorders are often limited by lack of available data, patient preference, and accessibility of resources.

Limited evidence supports pharmacotherapy

The use of pharmacotherapy for treating PDs is common, although there’s limited evidence to support the practice.11,22 Certain circumstances may allow for the judicious use of medication, although prescribing strategies are based largely on clinical experience and expert opinion.

Prescribers should emphasize a realistic perspective on treatment response, because research suggests at best a mild-moderate response of some personality traits to pharmacotherapy.11,22-25 There is no evidence for polypharmacy in treating PDs, and FPs should allow for sufficient treatment duration, switch medications rather than augment ineffective treatments, and resist the urge to prescribe for every psychological crisis.11,22,25,26

Patient safety should always be a consideration when prescribing medication. Because use of second-generation antipsychotics is associated with the metabolic syndrome, the patient’s baseline weight and fasting glucose, lipids, and hemoglobin A1c levels should be obtained and monitored regularly. Weight gain can be particularly distressing to patients, increase stress and anxiety, and hinder the doctor-patient relationship.25 Finally, medications with abuse potential or that can be lethal in overdose (eg, tricyclic antidepressants and benzodiazepines) are best avoided in patients with emotional lability and impulsivity.25,26

Tailor treatment to the specific PD

Tx for cluster A disorders. Few studies have examined the effectiveness of psychotherapies for cluster A disorders. Cognitive therapy may have benefit in addressing cognitive distortions and social impairment in schizotypal PD.11,12,22 There is little evidence supporting psychotherapy for paranoid PD, because challenging patients’ beliefs in this form is likely to exacerbate paranoia. Low-dose risperidone has demonstrated some beneficial effects on perceptual disturbances; however, the adverse metabolic effects of this medication may outweigh any potential benefit, as these symptoms are often not distressing to patients.6,27 In comparison, patients often find deficits in memory and attention to be more bothersome, and some data suggest that the alpha-2 agonist guanfacine may help treat these symptoms.28

Tx for cluster B disorders. Several forms of psychotherapy have proven effective in managing symptoms and improving overall functioning in patients with borderline PD, including dialectical behavioral therapy, mentalization-based therapy, transference-focused therapy, and schema therapy.29 Dialectical behavioral therapy is often the initial treatment because it emphasizes reducing self-harm behaviors and emotion regulation.11,17,26

Gunderson19 developed a more basic approach to treating borderline PD that is intended to be used by all clinicians who treat the disorder, and not just mental health professionals with advanced training in psychotherapy. A large, multisite randomized controlled trial found that the clinical efficacy of the technique, known as good psychiatric management, rivaled that of dialectical behavioral therapy.20,21

The general premise is that clinicians foster a therapeutic relationship that is supportive, engaging, and flexible. Physicians are encouraged to educate patients about the disorder and emphasize improvement in daily functioning. Clinicians should share the diagnosis with patients, which may give patients a sense of relief in having an accurate diagnosis and allow them to fully invest in diagnosis-specific treatments.19

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluated pharmacotherapy for borderline PD often have had conflicting conclusions as a result of analyzing data from underpowered studies with varying study designs.23,24,26,30,31 In targeting specific symptoms of the disorder, the most consistent evidence has supported the use of antipsychotics for cognitive perceptual disturbances; patients commonly experience depersonalization or out-of-body experiences.25 Additionally, the use of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers (lamotrigine and topiramate) appears to be somewhat effective for managing emotional lability and impulsivity.26,32,33 Despite the widespread use of SSRIs, a recent systematic review found the least support for these and other antidepressants for management of borderline PD.25

Tx for cluster C disorders. Some evidence supports using cognitive and interpersonal psychotherapies to treat cluster C PDs.34 In contrast, there is little evidence to support the use of pharmacotherapy.35 However, given the significant overlap among these disorders (especially avoidant PD) and social phobia and generalized anxiety disorder, effective pharmacologic strategies can be inferred based on data for those conditions.11 SSRIs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (eg, venlafaxine), and gabapentin have demonstrated efficacy in anxiety disorders and are reasonable and safe initial treatments for patients with a cluster C PD.11,34

Continue for the answers >>

CASE 1 › Mr. A’s schizotypal PD symptoms interfere with medication adherence because of his unusual belief system. Importantly, unlike patients with frank delusions, patients with schizotypal PD are willing to consider alternative explanations for their unusual beliefs. Mr. A’s intense suspiciousness may indicate some degree of overlap between paranoid and schizotypal PDs.

The FP is patient and willing to listen to Mr. A’s beliefs without devaluing them. To improve medication adherence, the FP offers him reasonable alternatives with clear explanations. (“I understand you have concerns about previous medications. At the same time, it seems that managing your blood pressure and cholesterol is important to you. Can we discuss alternative treatments?”)

CASE 2 › In response to Ms. B’s borderline PD, the FP must be cautious to avoid reacting out of frustration, which may upset the patient and validate her mistrust. The FP first reflects her anger (“I can tell you are upset because you don’t think I want to help you”), which may allow her to calmly engage in a discussion. He wants to recognize Ms. B’s dramatic behavior, but not reward it with added attention and unreasonable concessions. To help establish rapport, he provides a statement to legitimize Ms. B’s concerns (“Many patients would be frustrated during the process of changing physicians”).

The FP listens empathically to Ms. B, sets clear limits, and provides consistent and evidence-based treatments. He also provides early referral to psychotherapy, but to mitigate any perceived abandonment, he assures Ms. B he will remain involved with her treatment. (“It sounds like managing your anxiety is important to you, and often psychiatrists or therapists can help give additional options for treatment. I want you to know that I am still your doctor and we can review their recommendations together at our next visit.”)

CASE 3 › The FP recognizes that Ms. C’s pattern of perfectionism, formality, and rigidity in thought and behavior are likely a manifestation of obsessive-compulsive PD, and that the maladaptive psychological traits underlying her anxiety are distinct from a primary anxiety disorder.

An SSRI may be a reasonable option to treat Ms. B’s anxiety, and the FP also refers her for CBT. (“I can tell you are feeling really anxious and many people feel that way, especially with work. I think the medication is a good start, but I wonder if we could discuss other forms of therapy to maximize your symptom improvement.”) Because of their exacting nature, many patients with cluster C personality traits are willing to engage in treatments, especially if they are supported by data and recommended by a knowledgeable physician.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicholas Morcos, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan Health System, 1500 East Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; [email protected].

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Zimmerman M, Rothschild L, Chelminski I. The prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1911-1918.

3. Cloninger C, Svrakie D. Personality disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:2197-2240.

4. Bowins B. Personality disorders: a dimensional defense mechanism approach. Am J Psychother. 2010;64:153-169.

5. Raine A. Schizotypal personality: neurodevelopmental and psychosocial trajectories. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:291-326.

6. Rosell DR, Futterman SE, McMaster A, et al. Schizotypal personality disorder: a current review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16:452.

7. Gabbard GO, Simonsen E. Complex Case: The impact of personality and personality disorders on the treatment of depression. Personal Ment Health. 2007;1:161-175.

8. Caspi A, Begg D, Dickson N, et al. Personality differences predict health-risk behaviors in young adulthood: evidence from a longitudinal study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:1052-1063.

9. Tomko RL, Trull TJ, Wood PK, et al. Characteristics of borderline personality disorder in a community sample: comorbidity, treatment utilization, and general functioning. J Pers Disord. 2014;28:734-750.

10. Vaillant GE. The beginning of wisdom is never calling a patient a borderline; or, the clinical management of immature defenses in the treatment of individuals with personality disorders. J Psychother Pract Res. 1992;1:117-134.

11. Bateman AW, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorder. Lancet. 2015;385:735-743.

12. Beck AT, Davis DD, Freeman A, eds. Cognitive therapy of personality disorders. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2015.

13. O’Connor RC, Nock MK. The psychology of suicidal behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:73-85.

14. Paris J. Understanding self-mutilation in borderline personality disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13:179-185.

15. Diedrich A, Voderholzer U. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: a current review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17:2.

16. Pittenger C, Bloch MH. Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37:375-391.

17. Budge SL, Moore JT, Del Re AC, et al. The effectiveness of evidence-based treatments for personality disorders when comparing treatment-as-usual and bona fide treatments. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1057-1066.

18. Leichsenring F, Leibing E. The effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of personality disorders: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1223-1232.

19. Gunderson JG, Links PS. Handbook of good psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2014.

20. McMain SF, Links PS, Gnam WH, et al. A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1365-1374.

21. McMain SF, Guimond T, Streiner DL, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy compared with general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder: clinical outcomes and functioning over a 2-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:650-661.

22. Ripoll LH, Triebwasser J, Siever LJ. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:1257-1288.

23. Coccaro EF. Clinical outcome of psychopharmacologic treatment of borderline and schizotypal personality disordered subjects. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:30-35.

24. Soloff PH. Algorithms for pharmacological treatment of personality dimensions: symptom-specific treatments for cognitive-perceptual, affective, and impulsive-behavioral dysregulation. Bull Menninger Clin. 1998;62:195-214.

25. Silk KR. The process of managing medications in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17:311-319.

26. Saunders EF, Silk KR. Personality trait dimensions and the pharmacological treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:461-467.

27. Koenigsberg HW, Reynolds D, Goodman M, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of schizotypal personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:628-634.

28. McClure MM, Barch DM, Romero MJ, et al. The effects of guanfacine on context processing abnormalities in schizotypal personality disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1157-1160.

29. Stoffers JM, Vollm BA, Rucker G, et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD005652.

30. Siever LJ, Davis KL. A psychobiological perspective on the personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1647-1658.

31. Binks CA, Fenton M, McCarthy L, et al. Pharmacological interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD005653.

32. Nickel MK, Nickel C, Kaplan P, et al. Treatment of aggression with topiramate in male borderline patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:495-499.

33. Tritt K, Nickel C, Lahmann C, et al. Lamotrigine treatment of aggression in female borderline-patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19:287-291.

34. Simon W. Follow-up psychotherapy outcome of patients with dependent, avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: A meta-analytic review. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2009;13:153-165.

35. Ansseau M, Troisfontaines B, Papart P, et al. Compulsive personality as predictor of response to serotoninergic antidepressants. BMJ. 1991;303:760-761.

› Maintain a high index of suspicion for personality disorders (PDs) in patients who appear to be “difficult,” and take care to distinguish these diagnoses from primary mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. C

› Refer patients with PDs for psychotherapy, as it is considered the mainstay of treatment—particularly for borderline PD. B

› Use pharmacotherapy judiciously as an adjunctive treatment for PD. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Personality disorders (PDs) are common, affecting up to 15% of US adults, and are associated with comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions and increased utilization of health care resources.1,2 Having a basic understanding of these patterns of thinking and behaving can help family physicians (FPs) identify specific PD diagnoses, ensure appropriate treatment, and reduce the frustration that arises when an individual is viewed as a “difficult patient.”

Here we describe the diagnostic features of the disorders in the 3 major clusters of PDs and review an effective approach to the management of the most common disorder in each cluster, using a case study patient.

Defense mechanisms offer clues that your patient may have a PD

Personality is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviors that is relatively stable across time and in different situations. Such traits comprise an individual’s inherent makeup.1 PDs are diagnosed when an individual’s personality traits create significant distress or impairment in daily functioning. Specifically, PDs have a negative impact on cognition, affect, interpersonal relationships, and/or impulse control.1

One of the ways people alleviate distress is by using defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms are unconscious mental processes that individuals use to resolve conflicts, and thereby reduce anxiety and depression on a conscious level. Taken alone, defense mechanisms are not pathologic, but they may become maladaptive in certain stressful circumstances, such as when receiving medical treatment. Recognizing patterns of chronic use of certain defense mechanisms may be a clue that your patient has a PD. TABLE 13,4 and TABLE 23,4 provide an overview of common defense mechanisms used by patients with PDs.

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) organizes PDs into 3 clusters based on similar and often overlapping symptoms.1TABLE 31 provides a brief summary of the characteristic features of each disorder in these clusters.

Cluster A: Odd, eccentric

Patients with one of these disorders are odd, eccentric, or bizarre in their behavior and thinking. There appears to be a genetic link between cluster A PDs (especially schizotypal) and schizophrenia.5 These patients rarely seek treatment for their disorder because they have limited insight into their maladaptive traits.5,6

CASE 1 › Daniel A, age 57, has hypertension and hyperlipidemia and comes in to see his FP for a 6-month follow-up appointment. He never misses appointments, but has a history of poor adherence with prescribed medications. He enjoys his discussions with you in the office, although he often perseverates on conspiracy theories. He lives alone and has never been married. He believes that some of the previously prescribed medications, including a statin and a thiazide diuretic, were interfering with the absorption of “positive nutrients” in his diet. He also refuses to take the generic form of a statin, which he believes was adulterated by the government to be sold at lower cost.

Mr. A demonstrates the odd and eccentric beliefs that characterize schizotypal personality disorder. How can his FP best help him adhere to his medication regimen? (For the answer, click here.)

Schizotypal personality disorder shares certain disturbances of thought with schizophrenia, and is believed to exist on a spectrum with other primary psychotic disorders. Support for this theory comes from the higher rates of schizotypal PD among family members of patients with schizophrenia. There is a genetic component to the disorder.3,5,6

Clinically, these patients appear odd and eccentric with unusual beliefs. They may have a fascination with magic, clairvoyance, telepathy, or other such notions.1,5 Although the perceptual disturbances are unusual and often bizarre, they are not frank delusions: patients with schizotypal PD are willing to consider alternative explanations for their beliefs and can engage in rational discussion. Cognitive deficits, particularly of memory and attention, are common and distressing to patients. Frequently, the presenting complaint is depression and anxiety due to the emotional discord and isolation from others.1,3,5,6

Continue to cluster B >>

Cluster B: Dramatic, erratic

Patients with cluster B PDs are dramatic, excessively emotional, confrontational, erratic, and impulsive in their behaviors.1 They often have comorbid mood and anxiety disorders, as well as a disproportionately high co-occurrence of functional disorders.3,7 Their rates of health care utilization can be substantial. Because individuals with one of these PDs sometimes exhibit reckless and impulsive behavior, physicians should be aware these patients have a high risk of physical injuries (fights, accidents, self-injurious behavior), suicide attempts, risky sexual behaviors, and unplanned pregnancy.8,9

CASE 2 › Sheryl B is a 34-year-old new patient with a history of irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, depression, and anxiety who shows up for her appointment an hour late. She is upset and blames the office scheduler for not reminding her of the appointment. She brings a list of medications from her previous physician that includes sertraline, clonazepam, gabapentin, oxycodone, and as-needed alprazolam. She insists that her physician increase the dose of the benzodiazepines.

A review of her medical history reveals diagnoses of anxiety, bipolar disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Ms. B has also engaged in superficial cutting since adolescence, often triggered by arguments with her boyfriend. Currently, she attributes her anxiety and pain to not receiving the “correct medications” because of her transition from a previous physician who “knew her better than any other doctor.” After the FP explains to Ms. B that he would have to carefully review her case before continuing to prescribe benzodiazepines, she becomes tearful and argumentative, proclaiming, “You won’t give me the only thing that will help me because you want me to be miserable!”

Ms. B exhibits many cluster B personality traits consistent with borderline PD. How should the FP respond to her claims? (For the answer, click here.)