User login

Man Finds Worst Way to Get Out of Shoveling Snow

ANSWER

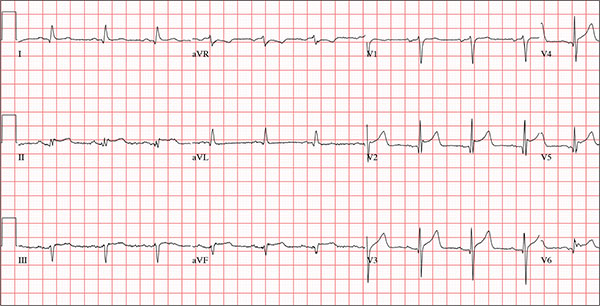

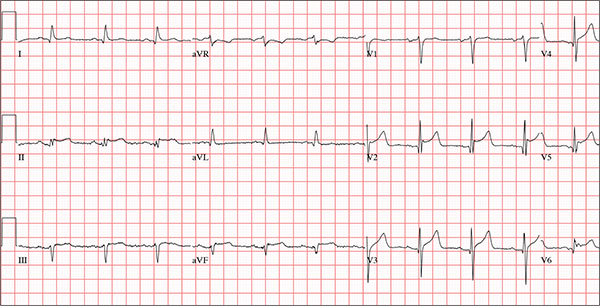

The correct answer is normal sinus rhythm, acute anterior myocardial infarction, and inferolateral injury.

A P wave for every QRS and a QRS for every P wave at a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min are indicative of normal sinus rhythm.

Acute anterior myocardial infarction is evidenced by the significant Q waves and ST elevations in leads I and V2 to V4 and inferolateral injury by ST elevations in limb leads II, III, and aVF and precordial leads V5 and V6.

Subsequent cardiac catheterization revealed an occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery, as well as significant lesions in the posterior descending artery and a marginal branch of the circumflex coronary artery.

ANSWER

The correct answer is normal sinus rhythm, acute anterior myocardial infarction, and inferolateral injury.

A P wave for every QRS and a QRS for every P wave at a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min are indicative of normal sinus rhythm.

Acute anterior myocardial infarction is evidenced by the significant Q waves and ST elevations in leads I and V2 to V4 and inferolateral injury by ST elevations in limb leads II, III, and aVF and precordial leads V5 and V6.

Subsequent cardiac catheterization revealed an occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery, as well as significant lesions in the posterior descending artery and a marginal branch of the circumflex coronary artery.

ANSWER

The correct answer is normal sinus rhythm, acute anterior myocardial infarction, and inferolateral injury.

A P wave for every QRS and a QRS for every P wave at a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min are indicative of normal sinus rhythm.

Acute anterior myocardial infarction is evidenced by the significant Q waves and ST elevations in leads I and V2 to V4 and inferolateral injury by ST elevations in limb leads II, III, and aVF and precordial leads V5 and V6.

Subsequent cardiac catheterization revealed an occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery, as well as significant lesions in the posterior descending artery and a marginal branch of the circumflex coronary artery.

A 66-year-old man presents with ongoing chest pain of 45 minutes’ duration followed by ventricular fibrillation. He was outside shoveling snow for about 30 minutes before his wife noticed that the sound of shoveling had ceased and her husband was nowhere to be seen. Upon investigation, she found him sitting on the porch, holding his chest and moaning, and she immediately called 911. Paramedics arrived within 10 minutes. When the ambulance pulled into the driveway, the patient stood up and collapsed. The paramedics identified ventricular fibrillation and resuscitated him with a single shock from the automatic external defibrillator. The patient quickly regained consciousness and did not require further intervention. According to the paramedics, the patient was in ventricular fibrillation for less than one minute. Oxygen and anti-angina therapy, started in the field, provided prompt relief of his chest pain. Upon arrival to the emergency department, the patient is awake, stable, and fully cognizant of what happened and where he is. History taking reveals that he has experienced chest pain with exertion for several weeks, beginning around Thanksgiving, but did not want to worry his family during the holiday season. All prior episodes stopped as soon as he ceased physical activity, unlike the one he experienced today. The patient has a history of hypertension but no other cardiac problems. Surgical history is remarkable for a right rotator cuff repair and removal of a melanoma from his nose. Family history is positive for myocardial infarction (both parents and paternal grandfather) and type 1 diabetes (mother). The patient, an only child, has two adult sons, both of whom are in good health. The patient is a retired attorney. He drinks approximately one bottle of wine per week, does not drink beer or hard liquor, and has never smoked. He has been quite active and runs 10K races three or four times per year. He denies recreational or herbal drug use. He currently takes no medications—not even the hydrochlorothiazide and metoprolol prescribed for his hypertension, neither of which he has taken for the past year. He says he occasionally takes ibuprofen for “typical muscle aches and pains.” He has no known drug allergies. The review of systems is unremarkable. The patient denies palpitations, shortness of breath, recent weight gain, and headaches. Physical exam reveals a well-nourished, well-groomed man with a blood pressure of 160/98 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; O2 saturation, 100% on 2 L of oxygen via nasal cannula; and temperature, 98.2°F. He reports his weight to be 189 lb and his height, 6 ft 2 in. There are no unusual findings: His lungs are clear; his cardiac exam reveals no murmurs, rubs, gallops, or arrhythmia; the abdomen is soft and not tender; there is no peripheral edema; and he is neurologically intact. An ECG, laboratory tests, and an echocardiogram are ordered. You review the ECG while the other tests are pending and note a ventricular rate of 80 beats/min; PR interval, 162 ms; QRS duration, 106 ms; QT/QTc interval, 390/426 ms; P axis, 51°; R axis, –20°; and T axis, 70°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Finding Spot-on Treatment for Acne

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

An 18-year-old woman is brought in by her mother for evaluation of longstanding acne. Although she is otherwise healthy, the patient has a significant family history of acne and recounts an extensive personal history of treatment attempts with both OTC and prescription products. Among these are several different benzoyl peroxide–based formulations (including one she bought after seeing an ad on TV) and devices including an electric scrub brush. None has had a significant impact. Tretinoin gel and oral erythromycin—prescribed by the patient’s primary care provider—haven’t helped much, either. The patient’s periods are regular and normal. She claims to be sexually abstinent. Examination reveals moderately severe acne confined to the patient’s face. Numerous open and closed comedones can be seen, as well as several pus-filled pimples. Scarring is minimal but present, especially on the sides of the face.

Axis I psychiatric disorders high in skin-restricted lupus patients

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders is high among people with skin-restricted lupus (SRL), compared with the general population, yet most do not receive specialist mental health care or appropriate psychotropic treatment, researchers report.

Investigators led by psychiatrist Isabelle Jalenques of the Clermont-Ferrand (France) University Hospital noted that psychiatric disorders had been extensively reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but no data existed on patients with skin-restricted disease (Br J Dermatol. 2016. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14392).

A previous exploratory study by the research group had shown that 60% of the 20 patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus studied had at least one psychiatric disorder. However the study was limited by its size and lack of a control group.

In the current multicenter study, the researchers compared 75 outpatients with SRL with 150 controls. Mean age of patients was 46 years and mean duration of disease was 10 years. They discovered that almost 49% of the patients with SRL fulfilled criteria for at least one current Axis I psychiatric disorder, compared with 13% of controls (OR, 5.0; P less than .001). Furthermore, 73% of patients fulfilled criteria for at least one lifetime Axis I psychiatric disorder, compared with 43% of controls (OR, 4.4; P less than .001).

The rates were close to that of patients with SLE for both current (42.2 and 46.7%) and lifetime psychiatric disorders (72%), Dr. Jalenques and her associates noted.

Patients with SRL were at a particularly high risk of the following psychiatric disorders, compared with controls:

• Major depressive disorder: current (9% vs. 0%; P = .0007) and lifetime (44% vs. 26%; P = .01).

• Generalized anxiety disorder: current (23% vs. 3%; P less than .001) and lifetime (35% vs. 19%; P = .03).

• Panic disorder: current (7% vs. 0%; P = .004) and lifetime (21 % vs. 3 %; P less than .001).

• Suicide risk: current (24% vs. 7%; P = .003).

• Alcohol dependence: current (7% vs. 0%; P = .004).

• Lifetime agoraphobia: (20% vs. 9%; P = .01).

Many patients were not receiving specialist mental health care or appropriate psychotropic treatment despite psychiatric disorders being a well-known cause of psychological distress, excess mortality, impaired global functioning, and poor compliance with medical treatment, Dr. Jalenques and her associates noted.

“Clinicians should be aware of the high prevalence of these disorders among SRL patients and not hesitate to refer such patients for psychiatric evaluation,” they concluded.

This study was supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Health and from Société Française de Dermatologie. The authors declared they have no conflicts of interest.

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders is high among people with skin-restricted lupus (SRL), compared with the general population, yet most do not receive specialist mental health care or appropriate psychotropic treatment, researchers report.

Investigators led by psychiatrist Isabelle Jalenques of the Clermont-Ferrand (France) University Hospital noted that psychiatric disorders had been extensively reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but no data existed on patients with skin-restricted disease (Br J Dermatol. 2016. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14392).

A previous exploratory study by the research group had shown that 60% of the 20 patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus studied had at least one psychiatric disorder. However the study was limited by its size and lack of a control group.

In the current multicenter study, the researchers compared 75 outpatients with SRL with 150 controls. Mean age of patients was 46 years and mean duration of disease was 10 years. They discovered that almost 49% of the patients with SRL fulfilled criteria for at least one current Axis I psychiatric disorder, compared with 13% of controls (OR, 5.0; P less than .001). Furthermore, 73% of patients fulfilled criteria for at least one lifetime Axis I psychiatric disorder, compared with 43% of controls (OR, 4.4; P less than .001).

The rates were close to that of patients with SLE for both current (42.2 and 46.7%) and lifetime psychiatric disorders (72%), Dr. Jalenques and her associates noted.

Patients with SRL were at a particularly high risk of the following psychiatric disorders, compared with controls:

• Major depressive disorder: current (9% vs. 0%; P = .0007) and lifetime (44% vs. 26%; P = .01).

• Generalized anxiety disorder: current (23% vs. 3%; P less than .001) and lifetime (35% vs. 19%; P = .03).

• Panic disorder: current (7% vs. 0%; P = .004) and lifetime (21 % vs. 3 %; P less than .001).

• Suicide risk: current (24% vs. 7%; P = .003).

• Alcohol dependence: current (7% vs. 0%; P = .004).

• Lifetime agoraphobia: (20% vs. 9%; P = .01).

Many patients were not receiving specialist mental health care or appropriate psychotropic treatment despite psychiatric disorders being a well-known cause of psychological distress, excess mortality, impaired global functioning, and poor compliance with medical treatment, Dr. Jalenques and her associates noted.

“Clinicians should be aware of the high prevalence of these disorders among SRL patients and not hesitate to refer such patients for psychiatric evaluation,” they concluded.

This study was supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Health and from Société Française de Dermatologie. The authors declared they have no conflicts of interest.

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders is high among people with skin-restricted lupus (SRL), compared with the general population, yet most do not receive specialist mental health care or appropriate psychotropic treatment, researchers report.

Investigators led by psychiatrist Isabelle Jalenques of the Clermont-Ferrand (France) University Hospital noted that psychiatric disorders had been extensively reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but no data existed on patients with skin-restricted disease (Br J Dermatol. 2016. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14392).

A previous exploratory study by the research group had shown that 60% of the 20 patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus studied had at least one psychiatric disorder. However the study was limited by its size and lack of a control group.

In the current multicenter study, the researchers compared 75 outpatients with SRL with 150 controls. Mean age of patients was 46 years and mean duration of disease was 10 years. They discovered that almost 49% of the patients with SRL fulfilled criteria for at least one current Axis I psychiatric disorder, compared with 13% of controls (OR, 5.0; P less than .001). Furthermore, 73% of patients fulfilled criteria for at least one lifetime Axis I psychiatric disorder, compared with 43% of controls (OR, 4.4; P less than .001).

The rates were close to that of patients with SLE for both current (42.2 and 46.7%) and lifetime psychiatric disorders (72%), Dr. Jalenques and her associates noted.

Patients with SRL were at a particularly high risk of the following psychiatric disorders, compared with controls:

• Major depressive disorder: current (9% vs. 0%; P = .0007) and lifetime (44% vs. 26%; P = .01).

• Generalized anxiety disorder: current (23% vs. 3%; P less than .001) and lifetime (35% vs. 19%; P = .03).

• Panic disorder: current (7% vs. 0%; P = .004) and lifetime (21 % vs. 3 %; P less than .001).

• Suicide risk: current (24% vs. 7%; P = .003).

• Alcohol dependence: current (7% vs. 0%; P = .004).

• Lifetime agoraphobia: (20% vs. 9%; P = .01).

Many patients were not receiving specialist mental health care or appropriate psychotropic treatment despite psychiatric disorders being a well-known cause of psychological distress, excess mortality, impaired global functioning, and poor compliance with medical treatment, Dr. Jalenques and her associates noted.

“Clinicians should be aware of the high prevalence of these disorders among SRL patients and not hesitate to refer such patients for psychiatric evaluation,” they concluded.

This study was supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Health and from Société Française de Dermatologie. The authors declared they have no conflicts of interest.

FROM BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The prevalence of psychiatric disorders is high among people with skin-restricted lupus, yet many do not receive specialist mental health care or appropriate psychotropic treatment.

Major finding: Almost half of the patients with SRL fulfilled criteria for at least one current Axis I psychiatric disorder, compared with 13% of controls (OR 5.0 [95% CI, 2.4-10.7], P less than .001).

Data source: A multicenter study of 75 outpatients with SRL and 150 control subjects.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Health and from Société Française de Dermatologie. The authors declared they have no conflicts of interest.

Organ transplant recipients face increased risk of BCC

Recipients of a solid organ transplant face up to a sixfold increase in the risk of developing a basal cell carcinoma – a risk that seems to increase as time passes.

A pretransplant history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) increased this risk to 55 times that seen in the general population, Dr. Britta Krynitz and her colleagues reported (Br J Dermatol. 2015. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14153).

But even when the pretransplant SCC group was removed from the final analysis, the risk of basal cell carcinoma after transplant was five times that of the general population, “indicating that a pretransplant SCC has limited effect on BCC risk overall and that organ transplantation per se is a strong driver of posttransplant BCC risk,” wrote Dr. Krynitz of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, and her coauthors.

“Our results strongly suggest tumor promoter effects of the immunosuppressive drugs in the pathogenesis of post-transplantation BCC,” the team said. “We speculate that calcineurin inhibitors and also antiproliferative drugs, often used in combination with corticosteroids, play a role.”

The researchers investigated the incidence of both BCC and SCC in a cohort of 4,023 patients who underwent solid organ transplant from 2004 to 2011. Their median age at the time of transplant was 53 years; most (59%) received a kidney. Other organs transplanted were liver (22%), heart and/or lung (15%), and other organs (4%). The median follow-up time was 3.4 years; the longest follow-up was 5.5 years.

Only 17 of patients had a history of melanoma, and 19 patients a history of SCC – less than 1% for each skin cancer. Seven percent (301) of patients had experienced some form of nonskin cancer.

By the end of follow-up, 341 BCCs had developed among 175 patients – an incidence of 6.7%. About half developed more than one BCC.

The researchers compared these patients to a group of almost 200,000 nontransplant patients who had developed BCC. Among these, the median age at BCC appearance was significantly older (71 years); 39% had more than one lesion.

The overall relative risk of BCC was increased sixfold in transplant recipients and was similar between the genders. However, the risk varied according to the type of organ received. Kidney recipients were at the highest risk (relative risk, 7.2), and those who received other organs had a lower risk (heart/lung: RR, 5.8; liver: RR, 2.6).

The risk also appeared to increase over time, the authors noted. From 0 to 2 years, it was 5.8; from 3 to 5 years, it increased to 7.0.

Among men, 54% of lesions appeared in the head/neck area and 35% on the trunk – a similar distribution to that seen in the nontransplant control group. Among women, there were differences between transplant patients and controls: 44% of lesions appeared on patients’ head/neck, compared with 60% in the control group, and 34% appeared on the truck, compared with 24% in the control group.

Histology was similar, as were the proportions of aggressive type II and highly aggressive type III lesions.

A total of 199 SCCs developed among 87 patients during follow-up, a ratio to BCC of 1:1.7. “The low ratio was probably due to the short follow-up in our study,” the authors noted.

The Welander Foundation, the Westerberg Foundation, and the Strategic Research Program in Epidemiology at Karolinska Institute sponsored the study. None of the authors had any financial declarations.

Recipients of a solid organ transplant face up to a sixfold increase in the risk of developing a basal cell carcinoma – a risk that seems to increase as time passes.

A pretransplant history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) increased this risk to 55 times that seen in the general population, Dr. Britta Krynitz and her colleagues reported (Br J Dermatol. 2015. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14153).

But even when the pretransplant SCC group was removed from the final analysis, the risk of basal cell carcinoma after transplant was five times that of the general population, “indicating that a pretransplant SCC has limited effect on BCC risk overall and that organ transplantation per se is a strong driver of posttransplant BCC risk,” wrote Dr. Krynitz of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, and her coauthors.

“Our results strongly suggest tumor promoter effects of the immunosuppressive drugs in the pathogenesis of post-transplantation BCC,” the team said. “We speculate that calcineurin inhibitors and also antiproliferative drugs, often used in combination with corticosteroids, play a role.”

The researchers investigated the incidence of both BCC and SCC in a cohort of 4,023 patients who underwent solid organ transplant from 2004 to 2011. Their median age at the time of transplant was 53 years; most (59%) received a kidney. Other organs transplanted were liver (22%), heart and/or lung (15%), and other organs (4%). The median follow-up time was 3.4 years; the longest follow-up was 5.5 years.

Only 17 of patients had a history of melanoma, and 19 patients a history of SCC – less than 1% for each skin cancer. Seven percent (301) of patients had experienced some form of nonskin cancer.

By the end of follow-up, 341 BCCs had developed among 175 patients – an incidence of 6.7%. About half developed more than one BCC.

The researchers compared these patients to a group of almost 200,000 nontransplant patients who had developed BCC. Among these, the median age at BCC appearance was significantly older (71 years); 39% had more than one lesion.

The overall relative risk of BCC was increased sixfold in transplant recipients and was similar between the genders. However, the risk varied according to the type of organ received. Kidney recipients were at the highest risk (relative risk, 7.2), and those who received other organs had a lower risk (heart/lung: RR, 5.8; liver: RR, 2.6).

The risk also appeared to increase over time, the authors noted. From 0 to 2 years, it was 5.8; from 3 to 5 years, it increased to 7.0.

Among men, 54% of lesions appeared in the head/neck area and 35% on the trunk – a similar distribution to that seen in the nontransplant control group. Among women, there were differences between transplant patients and controls: 44% of lesions appeared on patients’ head/neck, compared with 60% in the control group, and 34% appeared on the truck, compared with 24% in the control group.

Histology was similar, as were the proportions of aggressive type II and highly aggressive type III lesions.

A total of 199 SCCs developed among 87 patients during follow-up, a ratio to BCC of 1:1.7. “The low ratio was probably due to the short follow-up in our study,” the authors noted.

The Welander Foundation, the Westerberg Foundation, and the Strategic Research Program in Epidemiology at Karolinska Institute sponsored the study. None of the authors had any financial declarations.

Recipients of a solid organ transplant face up to a sixfold increase in the risk of developing a basal cell carcinoma – a risk that seems to increase as time passes.

A pretransplant history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) increased this risk to 55 times that seen in the general population, Dr. Britta Krynitz and her colleagues reported (Br J Dermatol. 2015. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14153).

But even when the pretransplant SCC group was removed from the final analysis, the risk of basal cell carcinoma after transplant was five times that of the general population, “indicating that a pretransplant SCC has limited effect on BCC risk overall and that organ transplantation per se is a strong driver of posttransplant BCC risk,” wrote Dr. Krynitz of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, and her coauthors.

“Our results strongly suggest tumor promoter effects of the immunosuppressive drugs in the pathogenesis of post-transplantation BCC,” the team said. “We speculate that calcineurin inhibitors and also antiproliferative drugs, often used in combination with corticosteroids, play a role.”

The researchers investigated the incidence of both BCC and SCC in a cohort of 4,023 patients who underwent solid organ transplant from 2004 to 2011. Their median age at the time of transplant was 53 years; most (59%) received a kidney. Other organs transplanted were liver (22%), heart and/or lung (15%), and other organs (4%). The median follow-up time was 3.4 years; the longest follow-up was 5.5 years.

Only 17 of patients had a history of melanoma, and 19 patients a history of SCC – less than 1% for each skin cancer. Seven percent (301) of patients had experienced some form of nonskin cancer.

By the end of follow-up, 341 BCCs had developed among 175 patients – an incidence of 6.7%. About half developed more than one BCC.

The researchers compared these patients to a group of almost 200,000 nontransplant patients who had developed BCC. Among these, the median age at BCC appearance was significantly older (71 years); 39% had more than one lesion.

The overall relative risk of BCC was increased sixfold in transplant recipients and was similar between the genders. However, the risk varied according to the type of organ received. Kidney recipients were at the highest risk (relative risk, 7.2), and those who received other organs had a lower risk (heart/lung: RR, 5.8; liver: RR, 2.6).

The risk also appeared to increase over time, the authors noted. From 0 to 2 years, it was 5.8; from 3 to 5 years, it increased to 7.0.

Among men, 54% of lesions appeared in the head/neck area and 35% on the trunk – a similar distribution to that seen in the nontransplant control group. Among women, there were differences between transplant patients and controls: 44% of lesions appeared on patients’ head/neck, compared with 60% in the control group, and 34% appeared on the truck, compared with 24% in the control group.

Histology was similar, as were the proportions of aggressive type II and highly aggressive type III lesions.

A total of 199 SCCs developed among 87 patients during follow-up, a ratio to BCC of 1:1.7. “The low ratio was probably due to the short follow-up in our study,” the authors noted.

The Welander Foundation, the Westerberg Foundation, and the Strategic Research Program in Epidemiology at Karolinska Institute sponsored the study. None of the authors had any financial declarations.

FROM BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The risk of a basal cell carcinoma increases after solid organ transplant.

Major finding: Transplant patients have a sixfold increased risk of BCC.

Data source: A retrospective database study of 4,000 transplant patients and almost 200,000 controls.

Disclosures: The Welander Foundation, the Westerberg Foundation, and the Strategic Research Program in Epidemiology at Karolinska Institute sponsored the study. None of the authors had any financial declarations.

A better way to relieve rib fracture pain in the ICU

SAN ANTONIO – A new pain relief option for multiple rib fractures means that you might not have to wait around anymore for anesthesiology to place thoracic epidurals.

It’s called posterior paramedian subrhomboidal (PoPS) analgesia. A skin incision is made below the lowest fractured rib just paramedian to the spinus processes; a tunneling device is then used to work a catheter upwards under the rhomboids just past the highest fractured rib. The catheter has multiple openings along its length – like a sprinkler hose – so analgesic bathes the intercostal nerves as it runs down from a reservoir into the patient. The reservoir can be set to a desired flow rate or for on-demand use (ON-Q Pain Relief System – Halyard).

A pilot study at the University of Kansas, Kansas City, found that pain control from PoPS was at least equivalent to standard thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA), and that the system can be placed by a variety of hospital staff, not just anesthesiologists.

The 11 PoPS patients also used fewer rescue narcotics than the 19 TEA patients and had less hypotension. Because they weren’t at risk for epidural hematomas, they started venous thromboembolism prophylaxis without delay and at full dose.

“Our results are very promising. PoPS provides pain control similar to that of TEA,” with several “other benefits. You are not relying on one specialty for pain control,” so patients probably get faster relief. “PoPS can also be placed in patients whose injuries prohibit TEA, such as those with spinal cord injuries or increased intracranial pressure,” said investigator Dr. Casey Shelley, a University of Kansas general surgery resident.

PoPS was placed in the study either by anesthesiologists or by a trauma surgeon who practiced placement beforehand in the cadaver lab. The do-it-yourself potential for surgeons “is key. Most of us trauma surgeons are sick of begging anesthesiologists to come place thoracic epidurals,” said an audience member after Dr. Shelley’s presentation at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Ropivacaine 0.2% was used in both PoPS and TEA patients, all of whom had at least three broken ribs.

Median pain scores dropped from 8.5 to 2.5 on a 10-point scale an hour after PoPS placement, versus a median drop from 8 to 5 points an hour after TEA (P = .03). Although not statistically significant, median pain scores were about 1.5 points better with PoPS over the next several days, hovering around 3.5 versus around 5 points with TEA. Anesthesiology “usually won’t place high thoracic epidurals. With PoPS, you can tunnel up as far as you need to go to get to higher ribs,” which might explain the better pain control, Dr. Shelley said.

PoPS patients used about 70 mg/day oral morphine equivalents versus about 90 mg/day with TEA through day 6, but again the difference was not statistically significant. Even so, it might explain why six TEA patients (32%) were hypotensive over that time, compared with two PoPS patients (18%).

PoPS patients were a little older on average (mean 63 versus 55 years), with more fractured ribs (mean eight versus seven), and higher Injury Severity Scale scores (mean 20 versus 16). They were also more likely to have bilateral fractures, longer ICU stays (mean 4.9 versus 3.1 days), and longer overall lengths of stay (mean 14.8 versus 9.8 days), but none of those trends were statistically significant.

Both groups had mean chest Abbreviated Injury Scale scores of 3, and there were no statistical differences in daily spirometry readings. The majority of patients in both groups were men.

Favorable results were also reported in 2010 for ON-Q rib pain control, but the investigators did not compare the system to TEA (World J Surg. 2010 Oct;34:2359-62).

Dr. Shelley said Halyard was not involved in the study, and that she has no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – A new pain relief option for multiple rib fractures means that you might not have to wait around anymore for anesthesiology to place thoracic epidurals.

It’s called posterior paramedian subrhomboidal (PoPS) analgesia. A skin incision is made below the lowest fractured rib just paramedian to the spinus processes; a tunneling device is then used to work a catheter upwards under the rhomboids just past the highest fractured rib. The catheter has multiple openings along its length – like a sprinkler hose – so analgesic bathes the intercostal nerves as it runs down from a reservoir into the patient. The reservoir can be set to a desired flow rate or for on-demand use (ON-Q Pain Relief System – Halyard).

A pilot study at the University of Kansas, Kansas City, found that pain control from PoPS was at least equivalent to standard thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA), and that the system can be placed by a variety of hospital staff, not just anesthesiologists.

The 11 PoPS patients also used fewer rescue narcotics than the 19 TEA patients and had less hypotension. Because they weren’t at risk for epidural hematomas, they started venous thromboembolism prophylaxis without delay and at full dose.

“Our results are very promising. PoPS provides pain control similar to that of TEA,” with several “other benefits. You are not relying on one specialty for pain control,” so patients probably get faster relief. “PoPS can also be placed in patients whose injuries prohibit TEA, such as those with spinal cord injuries or increased intracranial pressure,” said investigator Dr. Casey Shelley, a University of Kansas general surgery resident.

PoPS was placed in the study either by anesthesiologists or by a trauma surgeon who practiced placement beforehand in the cadaver lab. The do-it-yourself potential for surgeons “is key. Most of us trauma surgeons are sick of begging anesthesiologists to come place thoracic epidurals,” said an audience member after Dr. Shelley’s presentation at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Ropivacaine 0.2% was used in both PoPS and TEA patients, all of whom had at least three broken ribs.

Median pain scores dropped from 8.5 to 2.5 on a 10-point scale an hour after PoPS placement, versus a median drop from 8 to 5 points an hour after TEA (P = .03). Although not statistically significant, median pain scores were about 1.5 points better with PoPS over the next several days, hovering around 3.5 versus around 5 points with TEA. Anesthesiology “usually won’t place high thoracic epidurals. With PoPS, you can tunnel up as far as you need to go to get to higher ribs,” which might explain the better pain control, Dr. Shelley said.

PoPS patients used about 70 mg/day oral morphine equivalents versus about 90 mg/day with TEA through day 6, but again the difference was not statistically significant. Even so, it might explain why six TEA patients (32%) were hypotensive over that time, compared with two PoPS patients (18%).

PoPS patients were a little older on average (mean 63 versus 55 years), with more fractured ribs (mean eight versus seven), and higher Injury Severity Scale scores (mean 20 versus 16). They were also more likely to have bilateral fractures, longer ICU stays (mean 4.9 versus 3.1 days), and longer overall lengths of stay (mean 14.8 versus 9.8 days), but none of those trends were statistically significant.

Both groups had mean chest Abbreviated Injury Scale scores of 3, and there were no statistical differences in daily spirometry readings. The majority of patients in both groups were men.

Favorable results were also reported in 2010 for ON-Q rib pain control, but the investigators did not compare the system to TEA (World J Surg. 2010 Oct;34:2359-62).

Dr. Shelley said Halyard was not involved in the study, and that she has no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – A new pain relief option for multiple rib fractures means that you might not have to wait around anymore for anesthesiology to place thoracic epidurals.

It’s called posterior paramedian subrhomboidal (PoPS) analgesia. A skin incision is made below the lowest fractured rib just paramedian to the spinus processes; a tunneling device is then used to work a catheter upwards under the rhomboids just past the highest fractured rib. The catheter has multiple openings along its length – like a sprinkler hose – so analgesic bathes the intercostal nerves as it runs down from a reservoir into the patient. The reservoir can be set to a desired flow rate or for on-demand use (ON-Q Pain Relief System – Halyard).

A pilot study at the University of Kansas, Kansas City, found that pain control from PoPS was at least equivalent to standard thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA), and that the system can be placed by a variety of hospital staff, not just anesthesiologists.

The 11 PoPS patients also used fewer rescue narcotics than the 19 TEA patients and had less hypotension. Because they weren’t at risk for epidural hematomas, they started venous thromboembolism prophylaxis without delay and at full dose.

“Our results are very promising. PoPS provides pain control similar to that of TEA,” with several “other benefits. You are not relying on one specialty for pain control,” so patients probably get faster relief. “PoPS can also be placed in patients whose injuries prohibit TEA, such as those with spinal cord injuries or increased intracranial pressure,” said investigator Dr. Casey Shelley, a University of Kansas general surgery resident.

PoPS was placed in the study either by anesthesiologists or by a trauma surgeon who practiced placement beforehand in the cadaver lab. The do-it-yourself potential for surgeons “is key. Most of us trauma surgeons are sick of begging anesthesiologists to come place thoracic epidurals,” said an audience member after Dr. Shelley’s presentation at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Ropivacaine 0.2% was used in both PoPS and TEA patients, all of whom had at least three broken ribs.

Median pain scores dropped from 8.5 to 2.5 on a 10-point scale an hour after PoPS placement, versus a median drop from 8 to 5 points an hour after TEA (P = .03). Although not statistically significant, median pain scores were about 1.5 points better with PoPS over the next several days, hovering around 3.5 versus around 5 points with TEA. Anesthesiology “usually won’t place high thoracic epidurals. With PoPS, you can tunnel up as far as you need to go to get to higher ribs,” which might explain the better pain control, Dr. Shelley said.

PoPS patients used about 70 mg/day oral morphine equivalents versus about 90 mg/day with TEA through day 6, but again the difference was not statistically significant. Even so, it might explain why six TEA patients (32%) were hypotensive over that time, compared with two PoPS patients (18%).

PoPS patients were a little older on average (mean 63 versus 55 years), with more fractured ribs (mean eight versus seven), and higher Injury Severity Scale scores (mean 20 versus 16). They were also more likely to have bilateral fractures, longer ICU stays (mean 4.9 versus 3.1 days), and longer overall lengths of stay (mean 14.8 versus 9.8 days), but none of those trends were statistically significant.

Both groups had mean chest Abbreviated Injury Scale scores of 3, and there were no statistical differences in daily spirometry readings. The majority of patients in both groups were men.

Favorable results were also reported in 2010 for ON-Q rib pain control, but the investigators did not compare the system to TEA (World J Surg. 2010 Oct;34:2359-62).

Dr. Shelley said Halyard was not involved in the study, and that she has no disclosures.

AT THE EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY

Key clinical point: You might not have to wait around anymore for anesthesiology to place thoracic epidurals.

Major finding: Median pain scores dropped from 8.5 to 2.5 on a 10-point scale an hour after posterior PoPS placement, versus a median drop from 8 to 5 points an hour after thoracic epidural analgesia (P = .03).

Data source: Pilot study of 30 adults with at least three fractured ribs.

Disclosures: The maker of the PoPS system was not involved in the study, and the presenter had no disclosures.

Is lower BP worth it in higher-risk patients with diabetes or coronary disease?

There is no simple answer; the risk/benefit picture is complicated. Controlling blood pressure to a target of 130/80 mm Hg or lower produces mixed results in patients with diabetes and coronary disease equivalents (chronic kidney disease [CKD], coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, and previous stroke).

No evidence indicates that patients with diabetes or most patients with CKD have better outcomes if their blood pressure is controlled below 140/90 mm Hg. Patients with diabetes controlled to lower systolic blood pressure targets (below 120 mm Hg) have fewer strokes, but more serious adverse events. Achieving diastolic blood pressure targets below 80 mm Hg doesn’t reduce mortality, strokes, myocardial infarction, or congestive heart failure (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Tight blood pressure control (approximately 130/80 mm Hg or lower) reduces the risk of kidney failure by 27% in CKD patients with proteinuria at baseline. In patients without proteinuria, it doesn’t add benefit over standard blood pressure control (140/90 mm Hg) for reducing kidney failure, mortality, or cardiovascular events (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Controlling hypertension to 130/80 mm Hg or lower in patients with coronary artery disease reduces heart failure (27%) and stroke (18%) but increases the incidence of hypotensive episodes (220%) when compared with standard 140/90 mm Hg target blood pressure. Lower target pressures don’t affect total or cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, or angina, but do increase the need for revascularization in 6% of patients (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Controlling systolic blood pressure to a target of 120 mm Hg, compared with the standard target of 140 mm Hg, reduces a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, congestive heart failure, or cardiovascular death) by 25% and a secondary outcome of all-cause mortality by 27% in patients ages 50 and older with cardiovascular risk factors (but not diabetes or previous stroke).

However, intensive control doesn’t significantly improve the composite outcome in patients who are female, black, or younger than 75 years, or who have systolic blood pressures above 132 mm Hg, previous CKD, or previous cardiovascular disease. Intensive control causes more hypotension, syncope, and electrolyte abnormalities, but not falls resulting in injuries (SOR: B, large RCT).

No evidence-based studies exist to guide BP control in patients with peripheral artery disease or previous stroke. Current guidelines recommend treating hypertension to a target of 140/90 mm Hg in these patients.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane systematic review of 5 RCTs with a total of 7314 patients evaluated cardiovascular outcomes after 4.7 years follow-up in patients with diabetes who were treated for hypertension to either “lower” or “standard” target blood pressures.1 One trial in the review (ACCORD, 4734 patients) compared outcomes from significantly lower and standard systolic blood pressures (119/64 mm Hg vs 134/71 mm Hg; P<.0001) in patients with diabetes and either cardiovascular disease or 2 risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The authors evaluated outcomes based on achieved systolic blood pressures rather than intention to treat.

They found a reduced incidence of stroke (risk ratio [RR]=0.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.39-0.88; P=.009; number needed to treat [NNT]=91) but no change in mortality (RR=1.05; 95% CI, 0.84-1.30) at lower blood pressures. Achieving the lower systolic blood pressure increased the number of serious adverse effects, however (RR=2.58; 95% CI, 1.70-3.91; P<.0001; absolute risk increase=2%; number needed to harm=50).

Four RCTs (2580 patients) in the systematic review compared clinical outcomes produced by achieving significantly lower or standard diastolic blood pressure targets (128/76 mm Hg vs 135/83 mm Hg; P<.0001). The trials found no significant difference in total mortality (RR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.53-1.01), stroke (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.42-1.05), myocardial infarction (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.64-1.40), or congestive heart failure (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.58-1.92). Sensitivity analysis of trials comparing diastolic blood pressure targets below 80 mm Hg and below 90 mm Hg showed similar results.

The 4 RCTs didn’t report end-stage renal failure or total serious adverse events. The authors stated that there was a high risk of selection bias in favor of lower blood pressure targets.

Patients with CKD

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (9287 patients) compared outcomes of achieving lower blood pressure targets or standard targets in patients with CKD. Intensive blood pressure treatment reduced the risk of kidney failure only in patients with proteinuria at baseline (hazard ratio [HR]=0.73; 95% CI, 0.62-0.86; 5 trials, 1703 patients).2 Investigators didn’t report the degree of proteinuria for all the trials, but in one trial, patients had proteinuria of 1 to 3 g/d.

Achieved blood pressures in the intensive therapy group averaged 7.7/4.9 mm Hg lower, with pressures typically ranging from 75 to 80 mm Hg diastolic and 125 to 135 mm Hg systolic. Intensive blood pressure lowering didn’t reduce kidney failure in patients without baseline proteinuria (HR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.67-1.87; 3 trials, 1218 patients). Nor did it reduce death (RR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.84-1.05; 10 trials, 6788 patients) or major cardiovascular outcomes (RR=1.09; 95% CI, 0.83-1.42; 5 trials, 5308 patients).

Patients with coronary artery disease

A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs (66,504 patients) that evaluated tight control of hypertension (≤130/80 mm Hg) compared with standard control (<140/90 mm Hg) in patients with coronary artery disease found reduced rates of heart failure (RR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.64-0.84; 10 trials, 37,990 patients) and stroke (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.98; 9 trials, 8344 patients) but increased rates of hypotension (RR=2.19; 95% CI, 1.80-2.66; 6 trials, 17,836 patients).3

Achieving lower blood pressure targets didn’t reduce all-cause mortality (RR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.89-1.04; 13 trials, 39,262 patients), cardiovascular mortality (RR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.07; 11 trials, 38,452 patients), myocardial infarction (RR=0.92; 95% CI, 0.85-1.00; 14 trials, 39,696 patients), or angina (RR=0.92; 95% CI, 0.84-1.0; 11 trials, 28,007 patients). But it slightly increased the need for revascularization (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 1.01-1.12; 11 trials, 38,450 patients).

The SPRINT trial: Promising results for intensive treatment of some patients

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT), a large RCT, found that targeting systolic blood pressures below 120 mm Hg (compared with a target below 140 mm Hg) in middle-aged and older patients with increased cardiovascular risk reduced a composite outcome that included cardiovascular death by 25%.4

Researchers recruited 9361 patients older than 50 years (mean age 68 years; >28% older than 75 years) with systolic blood pressure between 130 and 180 mm Hg and increased cardiovascular risk defined by one or more of the following: preexisting cardiovascular disease, CKD with estimated glomerular filtration rate between 20 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, age >75 years, and Framingham 10-year risk of 15% or more. They excluded patients with diabetes or previous stroke.

Patients were randomized to intensive treatment (target systolic BP <120; mean achieved 121.4) or standard treatment (target systolic BP <140; mean achieved 136.2). Treatment typically comprised 3 (intensive) or 2 (standard) agents. The primary outcome was a composite of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, congestive heart failure, or cardiovascular death.

The study, which was originally intended to run for 5 years, was stopped at 3.26 years based on positive results. Intensive treatment improved the primary composite outcome overall (1.65% vs 2.19%; HR=0.75; 95% CI, 0.64-0.89; P<.001; NNT=61 over 3.26 years), all-cause mortality (HR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.60-0.90; P=.003; NNT=90), and cardiovascular death (HR=0.57; 95% CI, 0.38-0.85; P=.005; NNT=172).

However, intensive treatment didn’t significantly improve the primary composite outcome in these subgroups:

- female patients (HR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.62-1.14)

- black patients (HR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.55-1.06)

- patients with preexisting CKD (HR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.63-1.07) or cardiovascular disease (HR=0.83; 95% CI, 0.62-1.09)

- patients younger than 75 years (HR=0.80; 95% CI, 0.64-1.00)

- patients with systolic blood pressures higher than 132 mm Hg (BP >132 to <145 mm Hg, HR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.57-1.03; BP ≥145 mm Hg, HR=0.83; 95% CI, 0.63-1.09).

Intensive treatment also produced more net serious adverse events (HR=1.88; 4.7% vs 2.5%; P<.001), including: ≥30% decrease of glomerular filtration rates to values below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (HR=3.49; 95% CI, 2.44-5.10; P<.001), syncope (HR=1.44; 3.5% vs 2.4%; P=.003), hypotension (HR=1.70; 3.4% vs 2.0%; P<.001), and electrolyte abnormalities (HR=1.38; 3.8% vs 2.8%; P=.006). It didn’t cause injurious falls (HR=1.00; P=.97) or orthostatic hypotension in clinic (HR=0.88; 16.6% vs 18.3%; P=.01).

Guidelines for patients with peripheral artery disease, previous stroke

A national guideline by an expert panel recommended treating patients with hypertension who have peripheral artery disease or previous stroke to standard values for the general population: <140/90 mm Hg if ages 60 years or younger, <150/90 mm Hg if older than 60 years.5

1. Arguedas JA, Leiva V, Wright JM. Blood pressure targets for hypertension in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD008277.

2. Lv J, Ehteshami P, Sarnak M, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on the progression of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2013;185:949-957.

3. Bangalore S, Kumar S, Volodarskiy A, et al. Blood pressure targets in patients with coronary artery disease: observations from traditional and Bayesian random effects meta-analysis of randomised trials. Heart. 2013;99:601-613.

4. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

5. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

There is no simple answer; the risk/benefit picture is complicated. Controlling blood pressure to a target of 130/80 mm Hg or lower produces mixed results in patients with diabetes and coronary disease equivalents (chronic kidney disease [CKD], coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, and previous stroke).

No evidence indicates that patients with diabetes or most patients with CKD have better outcomes if their blood pressure is controlled below 140/90 mm Hg. Patients with diabetes controlled to lower systolic blood pressure targets (below 120 mm Hg) have fewer strokes, but more serious adverse events. Achieving diastolic blood pressure targets below 80 mm Hg doesn’t reduce mortality, strokes, myocardial infarction, or congestive heart failure (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Tight blood pressure control (approximately 130/80 mm Hg or lower) reduces the risk of kidney failure by 27% in CKD patients with proteinuria at baseline. In patients without proteinuria, it doesn’t add benefit over standard blood pressure control (140/90 mm Hg) for reducing kidney failure, mortality, or cardiovascular events (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Controlling hypertension to 130/80 mm Hg or lower in patients with coronary artery disease reduces heart failure (27%) and stroke (18%) but increases the incidence of hypotensive episodes (220%) when compared with standard 140/90 mm Hg target blood pressure. Lower target pressures don’t affect total or cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, or angina, but do increase the need for revascularization in 6% of patients (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Controlling systolic blood pressure to a target of 120 mm Hg, compared with the standard target of 140 mm Hg, reduces a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, congestive heart failure, or cardiovascular death) by 25% and a secondary outcome of all-cause mortality by 27% in patients ages 50 and older with cardiovascular risk factors (but not diabetes or previous stroke).

However, intensive control doesn’t significantly improve the composite outcome in patients who are female, black, or younger than 75 years, or who have systolic blood pressures above 132 mm Hg, previous CKD, or previous cardiovascular disease. Intensive control causes more hypotension, syncope, and electrolyte abnormalities, but not falls resulting in injuries (SOR: B, large RCT).

No evidence-based studies exist to guide BP control in patients with peripheral artery disease or previous stroke. Current guidelines recommend treating hypertension to a target of 140/90 mm Hg in these patients.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane systematic review of 5 RCTs with a total of 7314 patients evaluated cardiovascular outcomes after 4.7 years follow-up in patients with diabetes who were treated for hypertension to either “lower” or “standard” target blood pressures.1 One trial in the review (ACCORD, 4734 patients) compared outcomes from significantly lower and standard systolic blood pressures (119/64 mm Hg vs 134/71 mm Hg; P<.0001) in patients with diabetes and either cardiovascular disease or 2 risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The authors evaluated outcomes based on achieved systolic blood pressures rather than intention to treat.

They found a reduced incidence of stroke (risk ratio [RR]=0.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.39-0.88; P=.009; number needed to treat [NNT]=91) but no change in mortality (RR=1.05; 95% CI, 0.84-1.30) at lower blood pressures. Achieving the lower systolic blood pressure increased the number of serious adverse effects, however (RR=2.58; 95% CI, 1.70-3.91; P<.0001; absolute risk increase=2%; number needed to harm=50).

Four RCTs (2580 patients) in the systematic review compared clinical outcomes produced by achieving significantly lower or standard diastolic blood pressure targets (128/76 mm Hg vs 135/83 mm Hg; P<.0001). The trials found no significant difference in total mortality (RR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.53-1.01), stroke (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.42-1.05), myocardial infarction (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.64-1.40), or congestive heart failure (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.58-1.92). Sensitivity analysis of trials comparing diastolic blood pressure targets below 80 mm Hg and below 90 mm Hg showed similar results.

The 4 RCTs didn’t report end-stage renal failure or total serious adverse events. The authors stated that there was a high risk of selection bias in favor of lower blood pressure targets.

Patients with CKD

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (9287 patients) compared outcomes of achieving lower blood pressure targets or standard targets in patients with CKD. Intensive blood pressure treatment reduced the risk of kidney failure only in patients with proteinuria at baseline (hazard ratio [HR]=0.73; 95% CI, 0.62-0.86; 5 trials, 1703 patients).2 Investigators didn’t report the degree of proteinuria for all the trials, but in one trial, patients had proteinuria of 1 to 3 g/d.

Achieved blood pressures in the intensive therapy group averaged 7.7/4.9 mm Hg lower, with pressures typically ranging from 75 to 80 mm Hg diastolic and 125 to 135 mm Hg systolic. Intensive blood pressure lowering didn’t reduce kidney failure in patients without baseline proteinuria (HR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.67-1.87; 3 trials, 1218 patients). Nor did it reduce death (RR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.84-1.05; 10 trials, 6788 patients) or major cardiovascular outcomes (RR=1.09; 95% CI, 0.83-1.42; 5 trials, 5308 patients).

Patients with coronary artery disease

A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs (66,504 patients) that evaluated tight control of hypertension (≤130/80 mm Hg) compared with standard control (<140/90 mm Hg) in patients with coronary artery disease found reduced rates of heart failure (RR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.64-0.84; 10 trials, 37,990 patients) and stroke (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.98; 9 trials, 8344 patients) but increased rates of hypotension (RR=2.19; 95% CI, 1.80-2.66; 6 trials, 17,836 patients).3

Achieving lower blood pressure targets didn’t reduce all-cause mortality (RR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.89-1.04; 13 trials, 39,262 patients), cardiovascular mortality (RR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.07; 11 trials, 38,452 patients), myocardial infarction (RR=0.92; 95% CI, 0.85-1.00; 14 trials, 39,696 patients), or angina (RR=0.92; 95% CI, 0.84-1.0; 11 trials, 28,007 patients). But it slightly increased the need for revascularization (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 1.01-1.12; 11 trials, 38,450 patients).

The SPRINT trial: Promising results for intensive treatment of some patients

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT), a large RCT, found that targeting systolic blood pressures below 120 mm Hg (compared with a target below 140 mm Hg) in middle-aged and older patients with increased cardiovascular risk reduced a composite outcome that included cardiovascular death by 25%.4

Researchers recruited 9361 patients older than 50 years (mean age 68 years; >28% older than 75 years) with systolic blood pressure between 130 and 180 mm Hg and increased cardiovascular risk defined by one or more of the following: preexisting cardiovascular disease, CKD with estimated glomerular filtration rate between 20 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, age >75 years, and Framingham 10-year risk of 15% or more. They excluded patients with diabetes or previous stroke.

Patients were randomized to intensive treatment (target systolic BP <120; mean achieved 121.4) or standard treatment (target systolic BP <140; mean achieved 136.2). Treatment typically comprised 3 (intensive) or 2 (standard) agents. The primary outcome was a composite of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, congestive heart failure, or cardiovascular death.

The study, which was originally intended to run for 5 years, was stopped at 3.26 years based on positive results. Intensive treatment improved the primary composite outcome overall (1.65% vs 2.19%; HR=0.75; 95% CI, 0.64-0.89; P<.001; NNT=61 over 3.26 years), all-cause mortality (HR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.60-0.90; P=.003; NNT=90), and cardiovascular death (HR=0.57; 95% CI, 0.38-0.85; P=.005; NNT=172).

However, intensive treatment didn’t significantly improve the primary composite outcome in these subgroups:

- female patients (HR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.62-1.14)

- black patients (HR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.55-1.06)

- patients with preexisting CKD (HR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.63-1.07) or cardiovascular disease (HR=0.83; 95% CI, 0.62-1.09)

- patients younger than 75 years (HR=0.80; 95% CI, 0.64-1.00)

- patients with systolic blood pressures higher than 132 mm Hg (BP >132 to <145 mm Hg, HR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.57-1.03; BP ≥145 mm Hg, HR=0.83; 95% CI, 0.63-1.09).

Intensive treatment also produced more net serious adverse events (HR=1.88; 4.7% vs 2.5%; P<.001), including: ≥30% decrease of glomerular filtration rates to values below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (HR=3.49; 95% CI, 2.44-5.10; P<.001), syncope (HR=1.44; 3.5% vs 2.4%; P=.003), hypotension (HR=1.70; 3.4% vs 2.0%; P<.001), and electrolyte abnormalities (HR=1.38; 3.8% vs 2.8%; P=.006). It didn’t cause injurious falls (HR=1.00; P=.97) or orthostatic hypotension in clinic (HR=0.88; 16.6% vs 18.3%; P=.01).

Guidelines for patients with peripheral artery disease, previous stroke

A national guideline by an expert panel recommended treating patients with hypertension who have peripheral artery disease or previous stroke to standard values for the general population: <140/90 mm Hg if ages 60 years or younger, <150/90 mm Hg if older than 60 years.5

There is no simple answer; the risk/benefit picture is complicated. Controlling blood pressure to a target of 130/80 mm Hg or lower produces mixed results in patients with diabetes and coronary disease equivalents (chronic kidney disease [CKD], coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, and previous stroke).

No evidence indicates that patients with diabetes or most patients with CKD have better outcomes if their blood pressure is controlled below 140/90 mm Hg. Patients with diabetes controlled to lower systolic blood pressure targets (below 120 mm Hg) have fewer strokes, but more serious adverse events. Achieving diastolic blood pressure targets below 80 mm Hg doesn’t reduce mortality, strokes, myocardial infarction, or congestive heart failure (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Tight blood pressure control (approximately 130/80 mm Hg or lower) reduces the risk of kidney failure by 27% in CKD patients with proteinuria at baseline. In patients without proteinuria, it doesn’t add benefit over standard blood pressure control (140/90 mm Hg) for reducing kidney failure, mortality, or cardiovascular events (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Controlling hypertension to 130/80 mm Hg or lower in patients with coronary artery disease reduces heart failure (27%) and stroke (18%) but increases the incidence of hypotensive episodes (220%) when compared with standard 140/90 mm Hg target blood pressure. Lower target pressures don’t affect total or cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, or angina, but do increase the need for revascularization in 6% of patients (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Controlling systolic blood pressure to a target of 120 mm Hg, compared with the standard target of 140 mm Hg, reduces a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, congestive heart failure, or cardiovascular death) by 25% and a secondary outcome of all-cause mortality by 27% in patients ages 50 and older with cardiovascular risk factors (but not diabetes or previous stroke).

However, intensive control doesn’t significantly improve the composite outcome in patients who are female, black, or younger than 75 years, or who have systolic blood pressures above 132 mm Hg, previous CKD, or previous cardiovascular disease. Intensive control causes more hypotension, syncope, and electrolyte abnormalities, but not falls resulting in injuries (SOR: B, large RCT).

No evidence-based studies exist to guide BP control in patients with peripheral artery disease or previous stroke. Current guidelines recommend treating hypertension to a target of 140/90 mm Hg in these patients.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane systematic review of 5 RCTs with a total of 7314 patients evaluated cardiovascular outcomes after 4.7 years follow-up in patients with diabetes who were treated for hypertension to either “lower” or “standard” target blood pressures.1 One trial in the review (ACCORD, 4734 patients) compared outcomes from significantly lower and standard systolic blood pressures (119/64 mm Hg vs 134/71 mm Hg; P<.0001) in patients with diabetes and either cardiovascular disease or 2 risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The authors evaluated outcomes based on achieved systolic blood pressures rather than intention to treat.

They found a reduced incidence of stroke (risk ratio [RR]=0.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.39-0.88; P=.009; number needed to treat [NNT]=91) but no change in mortality (RR=1.05; 95% CI, 0.84-1.30) at lower blood pressures. Achieving the lower systolic blood pressure increased the number of serious adverse effects, however (RR=2.58; 95% CI, 1.70-3.91; P<.0001; absolute risk increase=2%; number needed to harm=50).

Four RCTs (2580 patients) in the systematic review compared clinical outcomes produced by achieving significantly lower or standard diastolic blood pressure targets (128/76 mm Hg vs 135/83 mm Hg; P<.0001). The trials found no significant difference in total mortality (RR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.53-1.01), stroke (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.42-1.05), myocardial infarction (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.64-1.40), or congestive heart failure (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.58-1.92). Sensitivity analysis of trials comparing diastolic blood pressure targets below 80 mm Hg and below 90 mm Hg showed similar results.

The 4 RCTs didn’t report end-stage renal failure or total serious adverse events. The authors stated that there was a high risk of selection bias in favor of lower blood pressure targets.

Patients with CKD

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (9287 patients) compared outcomes of achieving lower blood pressure targets or standard targets in patients with CKD. Intensive blood pressure treatment reduced the risk of kidney failure only in patients with proteinuria at baseline (hazard ratio [HR]=0.73; 95% CI, 0.62-0.86; 5 trials, 1703 patients).2 Investigators didn’t report the degree of proteinuria for all the trials, but in one trial, patients had proteinuria of 1 to 3 g/d.

Achieved blood pressures in the intensive therapy group averaged 7.7/4.9 mm Hg lower, with pressures typically ranging from 75 to 80 mm Hg diastolic and 125 to 135 mm Hg systolic. Intensive blood pressure lowering didn’t reduce kidney failure in patients without baseline proteinuria (HR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.67-1.87; 3 trials, 1218 patients). Nor did it reduce death (RR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.84-1.05; 10 trials, 6788 patients) or major cardiovascular outcomes (RR=1.09; 95% CI, 0.83-1.42; 5 trials, 5308 patients).

Patients with coronary artery disease

A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs (66,504 patients) that evaluated tight control of hypertension (≤130/80 mm Hg) compared with standard control (<140/90 mm Hg) in patients with coronary artery disease found reduced rates of heart failure (RR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.64-0.84; 10 trials, 37,990 patients) and stroke (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.98; 9 trials, 8344 patients) but increased rates of hypotension (RR=2.19; 95% CI, 1.80-2.66; 6 trials, 17,836 patients).3

Achieving lower blood pressure targets didn’t reduce all-cause mortality (RR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.89-1.04; 13 trials, 39,262 patients), cardiovascular mortality (RR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.07; 11 trials, 38,452 patients), myocardial infarction (RR=0.92; 95% CI, 0.85-1.00; 14 trials, 39,696 patients), or angina (RR=0.92; 95% CI, 0.84-1.0; 11 trials, 28,007 patients). But it slightly increased the need for revascularization (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 1.01-1.12; 11 trials, 38,450 patients).

The SPRINT trial: Promising results for intensive treatment of some patients

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT), a large RCT, found that targeting systolic blood pressures below 120 mm Hg (compared with a target below 140 mm Hg) in middle-aged and older patients with increased cardiovascular risk reduced a composite outcome that included cardiovascular death by 25%.4

Researchers recruited 9361 patients older than 50 years (mean age 68 years; >28% older than 75 years) with systolic blood pressure between 130 and 180 mm Hg and increased cardiovascular risk defined by one or more of the following: preexisting cardiovascular disease, CKD with estimated glomerular filtration rate between 20 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, age >75 years, and Framingham 10-year risk of 15% or more. They excluded patients with diabetes or previous stroke.

Patients were randomized to intensive treatment (target systolic BP <120; mean achieved 121.4) or standard treatment (target systolic BP <140; mean achieved 136.2). Treatment typically comprised 3 (intensive) or 2 (standard) agents. The primary outcome was a composite of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, congestive heart failure, or cardiovascular death.

The study, which was originally intended to run for 5 years, was stopped at 3.26 years based on positive results. Intensive treatment improved the primary composite outcome overall (1.65% vs 2.19%; HR=0.75; 95% CI, 0.64-0.89; P<.001; NNT=61 over 3.26 years), all-cause mortality (HR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.60-0.90; P=.003; NNT=90), and cardiovascular death (HR=0.57; 95% CI, 0.38-0.85; P=.005; NNT=172).

However, intensive treatment didn’t significantly improve the primary composite outcome in these subgroups:

- female patients (HR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.62-1.14)

- black patients (HR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.55-1.06)

- patients with preexisting CKD (HR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.63-1.07) or cardiovascular disease (HR=0.83; 95% CI, 0.62-1.09)

- patients younger than 75 years (HR=0.80; 95% CI, 0.64-1.00)

- patients with systolic blood pressures higher than 132 mm Hg (BP >132 to <145 mm Hg, HR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.57-1.03; BP ≥145 mm Hg, HR=0.83; 95% CI, 0.63-1.09).

Intensive treatment also produced more net serious adverse events (HR=1.88; 4.7% vs 2.5%; P<.001), including: ≥30% decrease of glomerular filtration rates to values below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (HR=3.49; 95% CI, 2.44-5.10; P<.001), syncope (HR=1.44; 3.5% vs 2.4%; P=.003), hypotension (HR=1.70; 3.4% vs 2.0%; P<.001), and electrolyte abnormalities (HR=1.38; 3.8% vs 2.8%; P=.006). It didn’t cause injurious falls (HR=1.00; P=.97) or orthostatic hypotension in clinic (HR=0.88; 16.6% vs 18.3%; P=.01).

Guidelines for patients with peripheral artery disease, previous stroke

A national guideline by an expert panel recommended treating patients with hypertension who have peripheral artery disease or previous stroke to standard values for the general population: <140/90 mm Hg if ages 60 years or younger, <150/90 mm Hg if older than 60 years.5

1. Arguedas JA, Leiva V, Wright JM. Blood pressure targets for hypertension in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD008277.

2. Lv J, Ehteshami P, Sarnak M, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on the progression of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2013;185:949-957.

3. Bangalore S, Kumar S, Volodarskiy A, et al. Blood pressure targets in patients with coronary artery disease: observations from traditional and Bayesian random effects meta-analysis of randomised trials. Heart. 2013;99:601-613.

4. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

5. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

1. Arguedas JA, Leiva V, Wright JM. Blood pressure targets for hypertension in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD008277.

2. Lv J, Ehteshami P, Sarnak M, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on the progression of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2013;185:949-957.

3. Bangalore S, Kumar S, Volodarskiy A, et al. Blood pressure targets in patients with coronary artery disease: observations from traditional and Bayesian random effects meta-analysis of randomised trials. Heart. 2013;99:601-613.

4. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

5. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Do corticosteroid injections improve carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms?