User login

Drug exhibits activity against myeloma, solid tumors

Image courtesy of PNAS

Researchers say they have determined how the investigational drug ONC201 is active against a range of malignancies.

The team found that ONC201 induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in multiple myeloma (MM) and solid tumor cell lines.

The drug triggered an increase in the anticancer protein TRAIL and induced cell death through an integrated stress response (ISR) involving the transcription factor ATF4, the transactivator CHOP, and the TRAIL receptor DR5.

The researchers reported these findings in Science Signaling. Some researchers involved in this study are affiliated with Oncoceutics Inc., the company developing ONC201.

“We have revealed, in unprecedented detail, exactly how ONC201 works across a broad range of tumor types, and this has important clinical implications,” said study author Wafik El-Deiry, MD, PhD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“For example, our findings suggest that patients with various solid tumors, as well as multiple myeloma, may be particularly sensitive to the effects of ONC201. We have identified a potential biomarker that could be used to select which patients are most likely to benefit therapeutically from this drug.”

Dr El-Deiry noted that TRAIL has been shown to induce cell death in a range of cancers while sparing normal cells. However, the therapeutic benefit of stimulating TRAIL is limited because of undesirable drug properties, such as a short half-life, difficult and expensive production, the need to give treatment as an intravenous infusion, and poor penetration into certain tissues like the brain.

“This prompted us to look for better options for therapeutics that can kill tumor cells,” Dr El-Deiry said.

He and his colleagues turned to ONC201, which has been shown to stimulate TRAIL. They tested the drug in 23 cancer cell lines representing 9 tumor types—MM, lymphoma, and glioma, as well as lung, colorectal, thyroid, liver, prostate, and breast cancer.

The team found that ONC201 triggers an increase in TRAIL and TRAIL receptor abundance, leading to tumor cell death through the ISR that tumor cells normally use to survive. ONC201 pushes the ISR too far, causing tumor cells to stop dividing and/or die.

ONC201 boosted expression of the gene encoding ATF4, a central component of the ISR, through a translation initiation factor called eIF2α. This process rapidly arrested the cancer’s cell cycle and resulted in cell death.

In essence, ONC201 delivers a double-whammy to tumor cells, Dr El-Deiry said, which may explain why it has such broad-spectrum anticancer activity.

The researchers believe this study has several clinical implications. For one, it suggests that solid tumors or MM cells that normally create large amounts of protein during growth may be particularly sensitive to ONC201. The ISR is often activated in these cells, and ONC201 may push them over the edge.

“Knowing how ONC201 works helps us look for its effects in patient’s tumor cells that have been treated,” Dr El-Deiry said. “Looking in a tumor or liquid biopsy before and after treatment may help predict who is most likely to benefit.”

“We are optimistic that, through basic and clinical research with ONC201, our findings will lead to improved TRAIL-based therapies for individual cancer patients in the future.”

Another study of ONC201, this one focusing only on hematologic malignancies, has been published in Science Signaling.

Early stage clinical trials for ONC201 are currently underway in patients with brain, colorectal, breast, and lung tumors, as well as leukemia and lymphoma. ![]()

Image courtesy of PNAS

Researchers say they have determined how the investigational drug ONC201 is active against a range of malignancies.

The team found that ONC201 induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in multiple myeloma (MM) and solid tumor cell lines.

The drug triggered an increase in the anticancer protein TRAIL and induced cell death through an integrated stress response (ISR) involving the transcription factor ATF4, the transactivator CHOP, and the TRAIL receptor DR5.

The researchers reported these findings in Science Signaling. Some researchers involved in this study are affiliated with Oncoceutics Inc., the company developing ONC201.

“We have revealed, in unprecedented detail, exactly how ONC201 works across a broad range of tumor types, and this has important clinical implications,” said study author Wafik El-Deiry, MD, PhD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“For example, our findings suggest that patients with various solid tumors, as well as multiple myeloma, may be particularly sensitive to the effects of ONC201. We have identified a potential biomarker that could be used to select which patients are most likely to benefit therapeutically from this drug.”

Dr El-Deiry noted that TRAIL has been shown to induce cell death in a range of cancers while sparing normal cells. However, the therapeutic benefit of stimulating TRAIL is limited because of undesirable drug properties, such as a short half-life, difficult and expensive production, the need to give treatment as an intravenous infusion, and poor penetration into certain tissues like the brain.

“This prompted us to look for better options for therapeutics that can kill tumor cells,” Dr El-Deiry said.

He and his colleagues turned to ONC201, which has been shown to stimulate TRAIL. They tested the drug in 23 cancer cell lines representing 9 tumor types—MM, lymphoma, and glioma, as well as lung, colorectal, thyroid, liver, prostate, and breast cancer.

The team found that ONC201 triggers an increase in TRAIL and TRAIL receptor abundance, leading to tumor cell death through the ISR that tumor cells normally use to survive. ONC201 pushes the ISR too far, causing tumor cells to stop dividing and/or die.

ONC201 boosted expression of the gene encoding ATF4, a central component of the ISR, through a translation initiation factor called eIF2α. This process rapidly arrested the cancer’s cell cycle and resulted in cell death.

In essence, ONC201 delivers a double-whammy to tumor cells, Dr El-Deiry said, which may explain why it has such broad-spectrum anticancer activity.

The researchers believe this study has several clinical implications. For one, it suggests that solid tumors or MM cells that normally create large amounts of protein during growth may be particularly sensitive to ONC201. The ISR is often activated in these cells, and ONC201 may push them over the edge.

“Knowing how ONC201 works helps us look for its effects in patient’s tumor cells that have been treated,” Dr El-Deiry said. “Looking in a tumor or liquid biopsy before and after treatment may help predict who is most likely to benefit.”

“We are optimistic that, through basic and clinical research with ONC201, our findings will lead to improved TRAIL-based therapies for individual cancer patients in the future.”

Another study of ONC201, this one focusing only on hematologic malignancies, has been published in Science Signaling.

Early stage clinical trials for ONC201 are currently underway in patients with brain, colorectal, breast, and lung tumors, as well as leukemia and lymphoma. ![]()

Image courtesy of PNAS

Researchers say they have determined how the investigational drug ONC201 is active against a range of malignancies.

The team found that ONC201 induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in multiple myeloma (MM) and solid tumor cell lines.

The drug triggered an increase in the anticancer protein TRAIL and induced cell death through an integrated stress response (ISR) involving the transcription factor ATF4, the transactivator CHOP, and the TRAIL receptor DR5.

The researchers reported these findings in Science Signaling. Some researchers involved in this study are affiliated with Oncoceutics Inc., the company developing ONC201.

“We have revealed, in unprecedented detail, exactly how ONC201 works across a broad range of tumor types, and this has important clinical implications,” said study author Wafik El-Deiry, MD, PhD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“For example, our findings suggest that patients with various solid tumors, as well as multiple myeloma, may be particularly sensitive to the effects of ONC201. We have identified a potential biomarker that could be used to select which patients are most likely to benefit therapeutically from this drug.”

Dr El-Deiry noted that TRAIL has been shown to induce cell death in a range of cancers while sparing normal cells. However, the therapeutic benefit of stimulating TRAIL is limited because of undesirable drug properties, such as a short half-life, difficult and expensive production, the need to give treatment as an intravenous infusion, and poor penetration into certain tissues like the brain.

“This prompted us to look for better options for therapeutics that can kill tumor cells,” Dr El-Deiry said.

He and his colleagues turned to ONC201, which has been shown to stimulate TRAIL. They tested the drug in 23 cancer cell lines representing 9 tumor types—MM, lymphoma, and glioma, as well as lung, colorectal, thyroid, liver, prostate, and breast cancer.

The team found that ONC201 triggers an increase in TRAIL and TRAIL receptor abundance, leading to tumor cell death through the ISR that tumor cells normally use to survive. ONC201 pushes the ISR too far, causing tumor cells to stop dividing and/or die.

ONC201 boosted expression of the gene encoding ATF4, a central component of the ISR, through a translation initiation factor called eIF2α. This process rapidly arrested the cancer’s cell cycle and resulted in cell death.

In essence, ONC201 delivers a double-whammy to tumor cells, Dr El-Deiry said, which may explain why it has such broad-spectrum anticancer activity.

The researchers believe this study has several clinical implications. For one, it suggests that solid tumors or MM cells that normally create large amounts of protein during growth may be particularly sensitive to ONC201. The ISR is often activated in these cells, and ONC201 may push them over the edge.

“Knowing how ONC201 works helps us look for its effects in patient’s tumor cells that have been treated,” Dr El-Deiry said. “Looking in a tumor or liquid biopsy before and after treatment may help predict who is most likely to benefit.”

“We are optimistic that, through basic and clinical research with ONC201, our findings will lead to improved TRAIL-based therapies for individual cancer patients in the future.”

Another study of ONC201, this one focusing only on hematologic malignancies, has been published in Science Signaling.

Early stage clinical trials for ONC201 are currently underway in patients with brain, colorectal, breast, and lung tumors, as well as leukemia and lymphoma. ![]()

Drug shows promise for treating resistant AML, MCL

Preclinical research suggests the investigational anticancer drug ONC201 can be effective against mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

ONC201 induced p53-independent apoptosis in AML and MCL cell lines and in samples from patients with either disease.

Investigators noted that p53 dysfunction occurs in more than half of malignancies and can promote resistance to standard chemotherapy.

“The clinical challenge posed by p53 abnormalities in blood malignancies is that therapeutic strategies other than standard chemotherapies are required,” said Michael Andreeff, MD, PhD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“We found that ONC201 caused p53-independent cell death and cell cycle arrest in cell lines and in lymphoma and acute leukemia patient samples.”

Dr Andreeff and his colleagues reported these findings in Science Signaling. Some of the investigators involved in this research are affiliated with Oncoceutics Inc., the company developing ONC201.

Dr Andreeff and his colleagues assessed the effects of ONC201 against AML and MCL, in both cultured cell lines and primary cells bearing either wild-type or mutant p53.

The patient samples included those that demonstrated genetic abnormalities linked to poor prognosis (FLT3 mutations, TP53 mutations) or resistance to ibrutinib. The team also tested ONC201 in a bortezomib-resistant myeloma cell line.

The experiments showed that ONC201 exerted anticancer activity regardless of p53 status, FLT3 mutations, or drug resistance. ONC201 proved active in the bortezomib-resistant myeloma cell line and in ibrutinib-resistant samples from MCL patients.

Experiments in mice showed that ONC201 caused cell death in AML and leukemia stem cells while sparing normal bone marrow cells.

And the investigators found that combining ONC201 with the BCL-2 antagonist venetoclax (ABT-199) synergistically increased apoptosis.

Further investigation revealed that ONC201 increased translation of the stress-induced protein ATF4 through stress signals similar to those caused by unfolded protein response (UPR) and integrated stress response (ISR).

“This increase in ATF4 in ONC201-treated hematopoietic cells promoted cell death,” Dr Andreeff explained. “However, unlike with UPR and ISR, the increase in ATF4 in ONC201-treated cells was not regulated by standard molecular signaling, indicating a novel mechanism of stressing cancer cells to death regardless of p53 status.”

The investigators noted that the mechanisms of ONC201 identified in solid tumors—namely, induction of TRAIL and DR5—were not operational in leukemia and lymphoma.

A study of ONC201 in solid tumors and multiple myeloma was published alongside this study in Science Signaling.

“There is clear evidence that ONC201 has clinical potential in hematological malignancies,” Dr Andreeff noted. “Clinical trials in leukemia and lymphoma patients have recently been initiated at MD Anderson.” ![]()

Preclinical research suggests the investigational anticancer drug ONC201 can be effective against mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

ONC201 induced p53-independent apoptosis in AML and MCL cell lines and in samples from patients with either disease.

Investigators noted that p53 dysfunction occurs in more than half of malignancies and can promote resistance to standard chemotherapy.

“The clinical challenge posed by p53 abnormalities in blood malignancies is that therapeutic strategies other than standard chemotherapies are required,” said Michael Andreeff, MD, PhD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“We found that ONC201 caused p53-independent cell death and cell cycle arrest in cell lines and in lymphoma and acute leukemia patient samples.”

Dr Andreeff and his colleagues reported these findings in Science Signaling. Some of the investigators involved in this research are affiliated with Oncoceutics Inc., the company developing ONC201.

Dr Andreeff and his colleagues assessed the effects of ONC201 against AML and MCL, in both cultured cell lines and primary cells bearing either wild-type or mutant p53.

The patient samples included those that demonstrated genetic abnormalities linked to poor prognosis (FLT3 mutations, TP53 mutations) or resistance to ibrutinib. The team also tested ONC201 in a bortezomib-resistant myeloma cell line.

The experiments showed that ONC201 exerted anticancer activity regardless of p53 status, FLT3 mutations, or drug resistance. ONC201 proved active in the bortezomib-resistant myeloma cell line and in ibrutinib-resistant samples from MCL patients.

Experiments in mice showed that ONC201 caused cell death in AML and leukemia stem cells while sparing normal bone marrow cells.

And the investigators found that combining ONC201 with the BCL-2 antagonist venetoclax (ABT-199) synergistically increased apoptosis.

Further investigation revealed that ONC201 increased translation of the stress-induced protein ATF4 through stress signals similar to those caused by unfolded protein response (UPR) and integrated stress response (ISR).

“This increase in ATF4 in ONC201-treated hematopoietic cells promoted cell death,” Dr Andreeff explained. “However, unlike with UPR and ISR, the increase in ATF4 in ONC201-treated cells was not regulated by standard molecular signaling, indicating a novel mechanism of stressing cancer cells to death regardless of p53 status.”

The investigators noted that the mechanisms of ONC201 identified in solid tumors—namely, induction of TRAIL and DR5—were not operational in leukemia and lymphoma.

A study of ONC201 in solid tumors and multiple myeloma was published alongside this study in Science Signaling.

“There is clear evidence that ONC201 has clinical potential in hematological malignancies,” Dr Andreeff noted. “Clinical trials in leukemia and lymphoma patients have recently been initiated at MD Anderson.” ![]()

Preclinical research suggests the investigational anticancer drug ONC201 can be effective against mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

ONC201 induced p53-independent apoptosis in AML and MCL cell lines and in samples from patients with either disease.

Investigators noted that p53 dysfunction occurs in more than half of malignancies and can promote resistance to standard chemotherapy.

“The clinical challenge posed by p53 abnormalities in blood malignancies is that therapeutic strategies other than standard chemotherapies are required,” said Michael Andreeff, MD, PhD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“We found that ONC201 caused p53-independent cell death and cell cycle arrest in cell lines and in lymphoma and acute leukemia patient samples.”

Dr Andreeff and his colleagues reported these findings in Science Signaling. Some of the investigators involved in this research are affiliated with Oncoceutics Inc., the company developing ONC201.

Dr Andreeff and his colleagues assessed the effects of ONC201 against AML and MCL, in both cultured cell lines and primary cells bearing either wild-type or mutant p53.

The patient samples included those that demonstrated genetic abnormalities linked to poor prognosis (FLT3 mutations, TP53 mutations) or resistance to ibrutinib. The team also tested ONC201 in a bortezomib-resistant myeloma cell line.

The experiments showed that ONC201 exerted anticancer activity regardless of p53 status, FLT3 mutations, or drug resistance. ONC201 proved active in the bortezomib-resistant myeloma cell line and in ibrutinib-resistant samples from MCL patients.

Experiments in mice showed that ONC201 caused cell death in AML and leukemia stem cells while sparing normal bone marrow cells.

And the investigators found that combining ONC201 with the BCL-2 antagonist venetoclax (ABT-199) synergistically increased apoptosis.

Further investigation revealed that ONC201 increased translation of the stress-induced protein ATF4 through stress signals similar to those caused by unfolded protein response (UPR) and integrated stress response (ISR).

“This increase in ATF4 in ONC201-treated hematopoietic cells promoted cell death,” Dr Andreeff explained. “However, unlike with UPR and ISR, the increase in ATF4 in ONC201-treated cells was not regulated by standard molecular signaling, indicating a novel mechanism of stressing cancer cells to death regardless of p53 status.”

The investigators noted that the mechanisms of ONC201 identified in solid tumors—namely, induction of TRAIL and DR5—were not operational in leukemia and lymphoma.

A study of ONC201 in solid tumors and multiple myeloma was published alongside this study in Science Signaling.

“There is clear evidence that ONC201 has clinical potential in hematological malignancies,” Dr Andreeff noted. “Clinical trials in leukemia and lymphoma patients have recently been initiated at MD Anderson.” ![]()

NIH’s peer-review process is flawed, team says

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The peer-review process the National Institutes of Health (NIH) use to allocate government research funds to US scientists may work no better than distributing those dollars at random, according to a group of researchers.

The group said their findings, published in eLife, suggest that peer review is not necessarily funding the best science, and awarding grants by lottery might actually produce equally good, if not better, results.

“The NIH claims that they are funding the best grants by the best scientists,” said study author Arturo Casadevall, MD, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland.

“While [our] data would argue that the NIH is funding a lot of very good science, they are also leaving a lot of very good science on the table. The government can’t afford to fund every good grant proposal, but the problems with the current system make it worse than awarding grants through a lottery.”

The researchers noted that the NIH rejects the majority of research grant proposals it receives. To decide which proposals to fund, the organization relies on expert panels whose members score each application. Funding decisions are made on the basis of these scores and the amount of available funds.

In recent years, the NIH has only funded those proposals ranked around the top 10%. The 2015 annual research budget for the NIH was $30.1 billion.

For their study, Dr Casadevall and his colleagues reanalyzed data on the 102,740 research project grants funded by the NIH from 1980 through 2008.

Another group of researchers previously collected the data. Their research, published in Science in 2015, suggested that peer review works, as the highest ranked research projects funded by the NIH earned the most citations.

For the current study, Dr Casadevall and his colleagues decided to look only at the top 20% of grants awarded. They found very little difference between the top-ranked projects and those projects ranked in the 20th percentile when it came to citations.

What the peer-review process can do, they determined, is discriminate between very good science and very bad science—that is, those in the top 20% versus those below the 50th percentile.

“We are not criticizing the peer reviewers,” said study author Ferric Fang, MD, of the University of Washington in Seattle.

“We are simply showing that there are limits to the ability of peer review to predict future productivity based on grant applications. This suggests that some of the resources and effort spent on ranking applications might be better spent elsewhere. While the average productivity of grants with better scores was somewhat higher, the differences were extremely small, raising questions as to whether the effort is worthwhile.”

The researchers noted that peer review isn’t cheap. The annual budget of the NIH Center for Scientific Review is $110 million. Individual NIH institutes and centers also spend money on peer review. The team said that money could be used toward more grants.

They also noted that peer review allows for substantial subjectivity. The objection of a single member of the committee can effectively kill a grant proposal, whether that objection is legitimate or not.

“When people’s opinions count a lot, we may be doing worse than choosing at random,” Dr Casadevall said. “A negative word at the table can often swing the debate. And this is how we allocate research funding in this country.”

However, Dr Casadevall and his colleagues do not recommend abandoning the peer-review process completely. They believe a way to improve the system might be to continue using peer review to identify the top proposals but then place those proposals into a lottery, with grants awarded at random. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The peer-review process the National Institutes of Health (NIH) use to allocate government research funds to US scientists may work no better than distributing those dollars at random, according to a group of researchers.

The group said their findings, published in eLife, suggest that peer review is not necessarily funding the best science, and awarding grants by lottery might actually produce equally good, if not better, results.

“The NIH claims that they are funding the best grants by the best scientists,” said study author Arturo Casadevall, MD, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland.

“While [our] data would argue that the NIH is funding a lot of very good science, they are also leaving a lot of very good science on the table. The government can’t afford to fund every good grant proposal, but the problems with the current system make it worse than awarding grants through a lottery.”

The researchers noted that the NIH rejects the majority of research grant proposals it receives. To decide which proposals to fund, the organization relies on expert panels whose members score each application. Funding decisions are made on the basis of these scores and the amount of available funds.

In recent years, the NIH has only funded those proposals ranked around the top 10%. The 2015 annual research budget for the NIH was $30.1 billion.

For their study, Dr Casadevall and his colleagues reanalyzed data on the 102,740 research project grants funded by the NIH from 1980 through 2008.

Another group of researchers previously collected the data. Their research, published in Science in 2015, suggested that peer review works, as the highest ranked research projects funded by the NIH earned the most citations.

For the current study, Dr Casadevall and his colleagues decided to look only at the top 20% of grants awarded. They found very little difference between the top-ranked projects and those projects ranked in the 20th percentile when it came to citations.

What the peer-review process can do, they determined, is discriminate between very good science and very bad science—that is, those in the top 20% versus those below the 50th percentile.

“We are not criticizing the peer reviewers,” said study author Ferric Fang, MD, of the University of Washington in Seattle.

“We are simply showing that there are limits to the ability of peer review to predict future productivity based on grant applications. This suggests that some of the resources and effort spent on ranking applications might be better spent elsewhere. While the average productivity of grants with better scores was somewhat higher, the differences were extremely small, raising questions as to whether the effort is worthwhile.”

The researchers noted that peer review isn’t cheap. The annual budget of the NIH Center for Scientific Review is $110 million. Individual NIH institutes and centers also spend money on peer review. The team said that money could be used toward more grants.

They also noted that peer review allows for substantial subjectivity. The objection of a single member of the committee can effectively kill a grant proposal, whether that objection is legitimate or not.

“When people’s opinions count a lot, we may be doing worse than choosing at random,” Dr Casadevall said. “A negative word at the table can often swing the debate. And this is how we allocate research funding in this country.”

However, Dr Casadevall and his colleagues do not recommend abandoning the peer-review process completely. They believe a way to improve the system might be to continue using peer review to identify the top proposals but then place those proposals into a lottery, with grants awarded at random. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The peer-review process the National Institutes of Health (NIH) use to allocate government research funds to US scientists may work no better than distributing those dollars at random, according to a group of researchers.

The group said their findings, published in eLife, suggest that peer review is not necessarily funding the best science, and awarding grants by lottery might actually produce equally good, if not better, results.

“The NIH claims that they are funding the best grants by the best scientists,” said study author Arturo Casadevall, MD, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland.

“While [our] data would argue that the NIH is funding a lot of very good science, they are also leaving a lot of very good science on the table. The government can’t afford to fund every good grant proposal, but the problems with the current system make it worse than awarding grants through a lottery.”

The researchers noted that the NIH rejects the majority of research grant proposals it receives. To decide which proposals to fund, the organization relies on expert panels whose members score each application. Funding decisions are made on the basis of these scores and the amount of available funds.

In recent years, the NIH has only funded those proposals ranked around the top 10%. The 2015 annual research budget for the NIH was $30.1 billion.

For their study, Dr Casadevall and his colleagues reanalyzed data on the 102,740 research project grants funded by the NIH from 1980 through 2008.

Another group of researchers previously collected the data. Their research, published in Science in 2015, suggested that peer review works, as the highest ranked research projects funded by the NIH earned the most citations.

For the current study, Dr Casadevall and his colleagues decided to look only at the top 20% of grants awarded. They found very little difference between the top-ranked projects and those projects ranked in the 20th percentile when it came to citations.

What the peer-review process can do, they determined, is discriminate between very good science and very bad science—that is, those in the top 20% versus those below the 50th percentile.

“We are not criticizing the peer reviewers,” said study author Ferric Fang, MD, of the University of Washington in Seattle.

“We are simply showing that there are limits to the ability of peer review to predict future productivity based on grant applications. This suggests that some of the resources and effort spent on ranking applications might be better spent elsewhere. While the average productivity of grants with better scores was somewhat higher, the differences were extremely small, raising questions as to whether the effort is worthwhile.”

The researchers noted that peer review isn’t cheap. The annual budget of the NIH Center for Scientific Review is $110 million. Individual NIH institutes and centers also spend money on peer review. The team said that money could be used toward more grants.

They also noted that peer review allows for substantial subjectivity. The objection of a single member of the committee can effectively kill a grant proposal, whether that objection is legitimate or not.

“When people’s opinions count a lot, we may be doing worse than choosing at random,” Dr Casadevall said. “A negative word at the table can often swing the debate. And this is how we allocate research funding in this country.”

However, Dr Casadevall and his colleagues do not recommend abandoning the peer-review process completely. They believe a way to improve the system might be to continue using peer review to identify the top proposals but then place those proposals into a lottery, with grants awarded at random. ![]()

Group identifies genes that may impact HSCT

Photo by Aaron Logan

A new screening method has revealed genes that regulate how hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) grow and thrive in mice.

Researchers used this method to uncover 17 genes that are regulators of hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Thirteen of these genes had never before been linked to HSPC engraftment.

The researchers reported their findings in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

“We recognized that one barrier to improving [HSCT] is a lack of understanding of how [HSPCs] successfully grow in the challenged environment of transplant, so we set out to identify the genes that control this process,” said Shannon McKinney-Freeman, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Dr McKinney-Freeman and her colleagues transplanted more than 1300 mice with shRNA-transduced HSPCs and searched for genes that regulate HSPC repopulation.

The team identified 17 such genes—Arhgef5, Armcx1, Cadps2, Crispld1, Emcn, Foxa3, Fstl1, Glis2, Gprasp2, Gpr56, Myct1, Nbea, P2ry14, Smarca2, Sox4, Stat4, and Zfp251.

For most of these genes, knockdown yielded a loss of function. The exceptions were Armcx1 and Gprasp2, whose loss enhanced HSPC repopulation.

“Our functional screen in mice is a first step to enhancing [HSCT],” Dr McKinney-Freeman said. “If we are to improve transplant outcomes in patients, we next need to study these identified genes and the molecules they specify in much more detail.”

“The more we understand the full scope of the molecular mechanisms that regulate stable engraftment of [HSPCs], the better equipped we will be to develop and clinically test novel therapies to improve health outcomes.” ![]()

Photo by Aaron Logan

A new screening method has revealed genes that regulate how hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) grow and thrive in mice.

Researchers used this method to uncover 17 genes that are regulators of hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Thirteen of these genes had never before been linked to HSPC engraftment.

The researchers reported their findings in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

“We recognized that one barrier to improving [HSCT] is a lack of understanding of how [HSPCs] successfully grow in the challenged environment of transplant, so we set out to identify the genes that control this process,” said Shannon McKinney-Freeman, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Dr McKinney-Freeman and her colleagues transplanted more than 1300 mice with shRNA-transduced HSPCs and searched for genes that regulate HSPC repopulation.

The team identified 17 such genes—Arhgef5, Armcx1, Cadps2, Crispld1, Emcn, Foxa3, Fstl1, Glis2, Gprasp2, Gpr56, Myct1, Nbea, P2ry14, Smarca2, Sox4, Stat4, and Zfp251.

For most of these genes, knockdown yielded a loss of function. The exceptions were Armcx1 and Gprasp2, whose loss enhanced HSPC repopulation.

“Our functional screen in mice is a first step to enhancing [HSCT],” Dr McKinney-Freeman said. “If we are to improve transplant outcomes in patients, we next need to study these identified genes and the molecules they specify in much more detail.”

“The more we understand the full scope of the molecular mechanisms that regulate stable engraftment of [HSPCs], the better equipped we will be to develop and clinically test novel therapies to improve health outcomes.” ![]()

Photo by Aaron Logan

A new screening method has revealed genes that regulate how hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) grow and thrive in mice.

Researchers used this method to uncover 17 genes that are regulators of hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Thirteen of these genes had never before been linked to HSPC engraftment.

The researchers reported their findings in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

“We recognized that one barrier to improving [HSCT] is a lack of understanding of how [HSPCs] successfully grow in the challenged environment of transplant, so we set out to identify the genes that control this process,” said Shannon McKinney-Freeman, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Dr McKinney-Freeman and her colleagues transplanted more than 1300 mice with shRNA-transduced HSPCs and searched for genes that regulate HSPC repopulation.

The team identified 17 such genes—Arhgef5, Armcx1, Cadps2, Crispld1, Emcn, Foxa3, Fstl1, Glis2, Gprasp2, Gpr56, Myct1, Nbea, P2ry14, Smarca2, Sox4, Stat4, and Zfp251.

For most of these genes, knockdown yielded a loss of function. The exceptions were Armcx1 and Gprasp2, whose loss enhanced HSPC repopulation.

“Our functional screen in mice is a first step to enhancing [HSCT],” Dr McKinney-Freeman said. “If we are to improve transplant outcomes in patients, we next need to study these identified genes and the molecules they specify in much more detail.”

“The more we understand the full scope of the molecular mechanisms that regulate stable engraftment of [HSPCs], the better equipped we will be to develop and clinically test novel therapies to improve health outcomes.” ![]()

MI Patients who Receive Followup Care are Less Likely to be Readmitted

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Myocardial infarction (MI) patients who are transferred to another hospital for care are less likely to be followed up and more likely to be readmitted to the hospital, new findings show.

"This group of patients may represent a vulnerable population and we really need to come up with specific strategies to make their post-discharge transition back to their local community as seamless as possible," corresponding author Dr. Amit Vora, of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, told Reuters Health.

Many patients admitted to their local hospital for acute MI must be transferred to another hospital for care, for example, to receive revascularization, Dr. Vora and his team note in their report, to be published online in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and outcomes. Logistical factors may lead to poor communication and coordination when it's time for the patient to be transferred back to their community, they add, which could be particularly problematic for older patients who may have more comorbidity and require closer follow-up after discharge.

To investigate, the researchers looked at outcomes for 39,136 acute MI patients 65 and older who were treated between 2007 and 2010 at 451 hospitals participating in Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network Registry-Get With the Guidelines.

Thirty-six percent of patients were transferred to another hospital for acute MI care, traveling a median of 43 miles.Within 30 days of discharge, 69.9% of the transferred patients had received outpatient follow-up, versus 78.2% of direct-arrival patients.

The adjusted risk of readmission for any cause was 14.5% for transferred patients versus 14% for direct-admit patients, while the risk of readmission for cardiovascular causes was 9.5% for

transferred patients and 9.1% for the direct-admit patients.However, the risk adjusted 30-day mortality was 1.6% for each group.

"Post-discharge care for acute MI patients is a performance measure, and we do track how often these patients are admitted

to the hospital following their discharge," Dr. Vora said. "A big focus of quality improvement is identifying strategies to reduce rehospitalization."

The next step in the research will be to identify the specific barriers to receiving follow-up care for transferred patients, he added, and then "define clear pathways and clear plans following discharge to ensure that these patients receive the care and the follow-up that they need."

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded this research. Three coauthors reported relevant relationships.

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Myocardial infarction (MI) patients who are transferred to another hospital for care are less likely to be followed up and more likely to be readmitted to the hospital, new findings show.

"This group of patients may represent a vulnerable population and we really need to come up with specific strategies to make their post-discharge transition back to their local community as seamless as possible," corresponding author Dr. Amit Vora, of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, told Reuters Health.

Many patients admitted to their local hospital for acute MI must be transferred to another hospital for care, for example, to receive revascularization, Dr. Vora and his team note in their report, to be published online in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and outcomes. Logistical factors may lead to poor communication and coordination when it's time for the patient to be transferred back to their community, they add, which could be particularly problematic for older patients who may have more comorbidity and require closer follow-up after discharge.

To investigate, the researchers looked at outcomes for 39,136 acute MI patients 65 and older who were treated between 2007 and 2010 at 451 hospitals participating in Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network Registry-Get With the Guidelines.

Thirty-six percent of patients were transferred to another hospital for acute MI care, traveling a median of 43 miles.Within 30 days of discharge, 69.9% of the transferred patients had received outpatient follow-up, versus 78.2% of direct-arrival patients.

The adjusted risk of readmission for any cause was 14.5% for transferred patients versus 14% for direct-admit patients, while the risk of readmission for cardiovascular causes was 9.5% for

transferred patients and 9.1% for the direct-admit patients.However, the risk adjusted 30-day mortality was 1.6% for each group.

"Post-discharge care for acute MI patients is a performance measure, and we do track how often these patients are admitted

to the hospital following their discharge," Dr. Vora said. "A big focus of quality improvement is identifying strategies to reduce rehospitalization."

The next step in the research will be to identify the specific barriers to receiving follow-up care for transferred patients, he added, and then "define clear pathways and clear plans following discharge to ensure that these patients receive the care and the follow-up that they need."

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded this research. Three coauthors reported relevant relationships.

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Myocardial infarction (MI) patients who are transferred to another hospital for care are less likely to be followed up and more likely to be readmitted to the hospital, new findings show.

"This group of patients may represent a vulnerable population and we really need to come up with specific strategies to make their post-discharge transition back to their local community as seamless as possible," corresponding author Dr. Amit Vora, of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, told Reuters Health.

Many patients admitted to their local hospital for acute MI must be transferred to another hospital for care, for example, to receive revascularization, Dr. Vora and his team note in their report, to be published online in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and outcomes. Logistical factors may lead to poor communication and coordination when it's time for the patient to be transferred back to their community, they add, which could be particularly problematic for older patients who may have more comorbidity and require closer follow-up after discharge.

To investigate, the researchers looked at outcomes for 39,136 acute MI patients 65 and older who were treated between 2007 and 2010 at 451 hospitals participating in Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network Registry-Get With the Guidelines.

Thirty-six percent of patients were transferred to another hospital for acute MI care, traveling a median of 43 miles.Within 30 days of discharge, 69.9% of the transferred patients had received outpatient follow-up, versus 78.2% of direct-arrival patients.

The adjusted risk of readmission for any cause was 14.5% for transferred patients versus 14% for direct-admit patients, while the risk of readmission for cardiovascular causes was 9.5% for

transferred patients and 9.1% for the direct-admit patients.However, the risk adjusted 30-day mortality was 1.6% for each group.

"Post-discharge care for acute MI patients is a performance measure, and we do track how often these patients are admitted

to the hospital following their discharge," Dr. Vora said. "A big focus of quality improvement is identifying strategies to reduce rehospitalization."

The next step in the research will be to identify the specific barriers to receiving follow-up care for transferred patients, he added, and then "define clear pathways and clear plans following discharge to ensure that these patients receive the care and the follow-up that they need."

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded this research. Three coauthors reported relevant relationships.

The Epidemiology of Hip and Groin Injuries in Professional Baseball Players

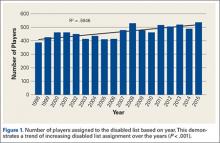

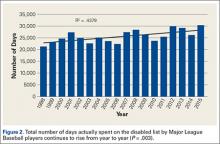

Injuries around the hip and groin occurring in professional baseball players can present as muscle strains, avulsions, contusions, hip subluxations or dislocations, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) causing labral tears or chondral defects, and athletic pubalgia.1-9 Several recent articles have reported on the epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries in Major League Baseball (MLB) players4,8,10 but with little attention to injuries to the hip and groin, likely because prior studies show only a 6.3% overall incidence for these injuries, much less than the more commonly discussed shoulder or elbow injuries.8 Despite the lower proportion of hip and groin injuries overall, these injuries lead to a relatively long period of disability for the players and often have a high rate of recurrence.4,8,9

The important contribution of hip mechanics and the surrounding muscular function in the kinetic chain during overhead athletic activities, such as a tennis serve or throwing, has recently been discussed.11,12 In sports requiring overhead activities, trunk rotation is a key component to generating force, and hip internal and external rotation is necessary for this trunk rotation to occur.12,13 Alterations in hip morphology causing constrained motion, as seen in FAI, may predispose an overhead throwing athlete to intra-articular injury such as labral tears or chondral injuries, or to a compensatory movement pattern causing an extra-articular soft tissue injury about the hip.12 Decreased hip range of motion may also lead to increased forces across the upper extremity during the throwing motion, which puts the shoulder and elbow at increased risk of injury.12

Increased awareness of hip and groin injuries, advances in diagnostic imaging, and an understanding of the relationship between the throwing motion in baseball and hip mechanics have improved our ability to appropriately identify and treat athletes with injuries of the hip and groin. Several studies on hip and groin injuries in elite athletes treated both operatively and nonoperatively have reported a high rate of return to sport.3,7,14-19 A systematic review on return to sport following hip arthroscopy for intra-articular pathology associated with FAI showed a 95% return to sport rate and a 92% rate of return to pre-injury level of play in a subgroup of professional athletes in 9 studies.20

Despite the large body of literature on upper extremity injuries, there is no study specifically focusing on the epidemiology of hip and groin injuries in MLB or Minor League Baseball (MiLB) players. The incidence of all injuries in professional baseball players has steadily increased over the last 2 decades,8 and the reported incidence of hip and groin injuries will likely increase as well. The current incidence of this injury, the positions most at risk, the mechanism of injury, and the time to return to sport are important to understand given the large number of players who participate in baseball not only at a professional level, but also at an amateur level, where this information may also be applicable. This information could improve our efforts at prevention and rehabilitation of these injuries, and can guide efforts to counsel and train players at high risk of a hip or groin injury. To address this gap in the literature, the purpose of this study was to describe the epidemiology of hip and groin injuries in MLB and MiLB players from 2011 to 2014.

Materials and Methods

Population and Sample

US MLB is comprised of the major and minor leagues. The major leagues are divided into 30 clubs, with 25 active players, for a total of 750 active players. Each club has a 40-man roster consisting of 25 active players and up to 15 additional players who are either not active or optioned to the minor leagues. The minor leagues are comprised of a network of over 200 clubs that are each affiliated with a major league club, and organized by geography and level of play. The minor leagues consist of roughly 7500 players, of whom about 6500 are actively playing at any given time. The entire population of players in the MLB who sustained a hip or groin injury over the study period was eligible for this study.

Data

The MLB’s Health and Injury Tracking System (HITS) is a centralized database that contains the de-identified medical data from the electronic medical record (EMR) system. Data on all injuries are entered into the EMR by each team’s certified athletic trainer. An injury is defined as any physical complaint sustained by a player that affects or limits participation in any aspect of baseball-related activity (eg, game, practice, warm-up, conditioning, weight training). The data extracted from HITS only relates to injuries that resulted in lost game time for a player and that occurred during spring training, regular season, or postseason play; off-season injuries were not included. Injury events that were classified as “season-ending” were not included in the analysis of assessing days missed because many of these players may not have been cleared to play until the beginning of the following season. For each injury, data were collected on the diagnosis, body part, activity, location, and date of injury.

Materials and Methods

Hip and groin injuries were defined as cases having a body region variable classified as “hip/groin” or a Sports Medicine Diagnostic Coding System (SMDCS) that included any “adductor” or “hernia” or “hip pointer” labels. Cases categorized as inguinal and femoral hernia (n = 26) and testicular contusions (n = 87) were excluded. Characteristics about each hip and groin injury were also extracted from HITS. These variables included level of play, player position (activity at the time of injury), field location, injury mechanism, chronicity of the injury, and days missed. Chronicity of the injury was documented as acute, overuse, or undetermined. For level of play, the injury event was categorized as the league in which the game was played when the injury occurred. Players were excluded if they had an unknown level of play or were in the amateur league. The injuries of the hip and groin were further classified as intra-articular and extra-articular. Treatment for each injury was characterized as surgical or nonsurgical, and correlated with days missed for each type of injury.

Statistical Analysis

Data for the 2011-2014 seasons were combined, and results presented for all players and separately for MiLB and MLB. Frequencies and comparative analyses for hip and groin injuries were performed across the aforementioned injury characteristics. The distribution of days missed for the variables considered was often skewed to the right, even after excluding the season-ending injuries; hence, the mean days missed was often larger than the median days missed. Reporting the median would allow for a robust estimate of the expected number of days missed, but would down weight those instances when hip and groin injuries result in much longer missed days, as reflected by the mean. Because of the importance of the days missed measure for professional baseball, both the mean and median are presented. Chi-square tests were used to test the hypothesis of equal proportions between the various categories of hip and groin characteristics, with statistical significance determined at the P = .05 level.

In order to estimate exposure, the average number of players per team per game was calculated based on analysis of regular season game participation via box scores that are publicly available. This average number over a season, multiplied by the number of team games at each professional level of baseball, was used as an estimate of athlete exposures in order to provide rates comparable to those of other injury surveillance systems. Injury rates were reported as injuries per 1000 athlete-exposures (AE) for those hip and groin injuries that occurred during the regular season. It should be noted that the number of regular season hip and groin injuries and the subsequent AE rates are based on injuries that were deemed work-related during the regular season. This does not necessarily only include injuries occurring during the course of a game, but injuries in game preparation as well. Due to the variations in spring training games and fluctuating rosters, an exposure rate could not be calculated for spring training hip and groin injuries.

Data analysis was performed in the R statistical computing Environment (R Core Team 2014). Study procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Results

Overall Summary

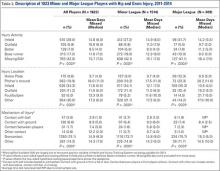

A total of 1823 hip and groin injuries occurred from 2011-2014, with 83% occurring in MiLB and 17% occurring in MLB (Table 1). There were 1146 acute injuries, 252 overuse injuries, and 425 injuries of undetermined chronicity. The average age of players experiencing a hip and groin injury in MiLB was 22.9 years compared to 29.7 years in MLB. Of the 1514 hip and groin injuries in MiLB, 76 (5.0%) required surgery and of the 309 hip and groin injuries in MLB, 24 (7.8%) required surgery. Compared to league-wide injury events, hip and groin injuries ranked 6th highest in prevalence in MiLB and 8th highest in prevalence in MLB, accounting for 5.4% and 5.6%, respectively, of the 28,116 MiLB and 5507 MLB injury events that occurred between 2011-2014.

For regular season games, it was estimated that there were 1,197,738 MiLB and 276,608 MLB AE from 2011-2014. The overall hip and groin rate across both MLB and MiLB was 1.2 per 1000 AE, based on the 238 and 1152 regular season hip and groin injuries in MLB and MiLB, respectively. The rate of hip and groin injury was 1.5 times more likely in MiLB than in MLB (P < .0001) (rate of 1.26 per 1000 AE in MiLB and 0.86 per 1000 AE in MLB).

Characteristics of Injuries

Injury activity was based on the position being played at the time of injury, with categories of infield and outfield corresponding to fielding activities (defense), with batting and base runner categories corresponding to activities while on offense (Table 2). The occurrence of hip and groin injuries while players are fielding on defense (MiLB 33.0%, MLB 37.2%, all players 33.8%) was significantly greater compared to injuries while batting and base running on offense (MiLB 24.9%, MLB 21.7%, all players 24.3%) (all P values < .001). There was a high percentage of missing data for the event position variable, which resulted from this field not being available in HITS for 2011. Time lost due to hip and groin injuries was similar across leagues with respect to injury activity, ranging on average between 8 and 18 days.

There were statistically significant differences for MiLB and MLB separately, and combined, in the number of hip and groin injuries by field location (all P values < .0001) (Table 2). For MiLB, MLB, and across both leagues, by injury location, the majority of hip and groin injuries occurred in the infield (MiLB 34.1%, MLB 35.3%, all players 34.3%). As a single location, the pitcher’s mound accounted for a large proportion of hip and groin injuries (MiLB 19.2%, MLB 23.3%, all players 19.9%). Time lost due to hip and groin injuries was similar across leagues with respect to field location, ranging on average between about 10 and 22 days. Among all players, injuries on the pitcher’s mound resulted in the largest mean days missed after injury.

There were statistically significant differences across the mechanisms of injury for MiLB and MLB, as well as both leagues combined (all P values < .0001) (Table 2). The majority of hip and groin injuries were noncontact-related (MiLB 73.7%, MLB 75.7%, all players 74.1%) compared to those resulting from some form of contact (MiLB 11.4%, MLB 12.6%, all players 11.7%) or other mechanisms. Time lost across these mechanisms varied, ranging on average between 4 and 15 days with noncontact-related hip and groin injuries resulting in the largest time lost.

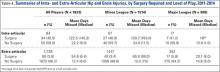

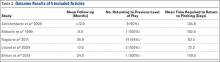

Surgery

The 1823 hip and groin injuries across both leagues were further classified using the SMDCS descriptions as intra-articular (N = 84) or extra-articular (N = 1739) (Table 3). A much larger percentage of hip and groin injuries were extra-articular (MiLB 95.6%, MLB 94.4%, all players 95.4%) compared to those classified as intra-articular (Table 3). The most common extra-articular injuries were strains or contusions of the adductor, iliopsoas, or gluteal muscles, making up 79.1% of this group of injuries. The most common intra-articular injuries were FAI and a labral tear, accounting for 80.9% of these injuries. Only a small percentage of the extra-articular cases required surgery (MiLB 3.4%, MLB 5.8%, all players 3.8%) (Table 4). This finding was in contrast to the larger percentage of intra-articular cases requiring surgery (MiLB 40.3%, MLB 41.2%, all players 40.5%). Time lost varied greatly by surgery status, as well as extra-articular or intra-articular, as would be expected even after excluding season-ending injuries. For both types of injuries, the average time lost was consistently greater for injuries that required surgery versus the ones that did not result in surgery.

Discussion

The incidence of overall injuries in MLB players is increasing.8 Injuries to the hip and groin for professional baseball players continue to be of concern both in the number of injuries and the potential for these injuries to be debilitating or to recur. The correct diagnosis of hip injuries can be challenging in these athletes due to the complex anatomy of the region. However, our understanding of the pathoanatomy of hip and groin injuries, combined with the utilization of improved magnetic resonance imaging (MRI,) has aided in making the correct diagnosis more reliable. Although upper extremity injuries have traditionally been the focus of MLB injury reporting, hip injuries have been shown to cause an average of 23 days missed per player.4 This was similar to the more commonly highlighted elbow and knee injuries in the same study (23 and 27 days, respectively). The purpose of this study was to explore the epidemiology of hip and groin injuries in MLB. The lack of existing data on this issue is important for sports injury research. Exploring these injuries increases the understanding of which players are at risk, and how we can tailor training programs for prevention or rehabilitation programs for those players who suffer these injuries.

In addition to the increased awareness of hip injuries, there has been a recent focus on the contribution of hip range of motion, leg drive, and pelvic rotation to the overall mechanics of overhead activities such as throwing, a tennis serve, or pitching.12 Pelvic rotation and leg drive have been correlated to throwing velocity,21 and therefore if hip range of motion is inhibited by pain or a structural issue such as FAI, there will likely be altered upper extremity mechanics leading to less power and possibly injury.12 Additionally, it has been shown that limited hip range of motion due to FAI is correlated with compensatory lower extremity muscular injuries such as hamstring and adductor strains as well as overload of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint.22

In the current study, extra-articular injuries about the hip were the most common, making up 95.4% of the total injuries. Many (79.1%) of these were strains or contusions of the adductor, iliopsoas, or gluteal muscles. This is consistent with other articles reporting hip injuries in athletes.3,9 A study on hip injuries in the National Football League found that strains and contusions comprised 92% of all hip injuries.3 Another report on European professional football found that 72% of hip injuries over a 7-season period were adductor or iliopsoas injuries.9 This prior study also reported that 15% of the hip and groin strains were re-injuries. Intra-articular injuries comprised only 4.6% of the hip injuries in our study. FAI and labral tears were the most common intra-articular diagnosis at 80.9%.

Almost all (96.2%) of the extra-articular hip injuries in this series were able to be treated nonoperatively and caused a mean of 12.4 days missed. Those which required operative treatment caused a mean of 54.6 days missed. For intra-articular injuries, 40.5% were treated surgically and these players missed a mean 122.5 days. Those treated nonsurgically missed an average of 22.2 days. Whether treated surgically or nonsurgically, the mean days missed following an intra-articular injury was approximately twice that of extra-articular injuries. Our findings regarding time or games missed are similar to other reports studying hip injuries in professional athletes.2,3,9 Intra-articular injuries such as FAI, chondral injuries, or labral tears caused between 46 and 64 days missed compared to 3 to 27 days missed for extra-articular injuries in professional soccer players.9 Feeley and colleagues3 found a mean of 5.07 to 33.6 days missed for extra-articular injuries such as strains or contusions, and 63.5 to 126.2 days missed for intra-articular injuries including arthritis, labral tears, subluxations, dislocations, and fractures. A report on National Hockey League players found that intra-articular injuries made up 10.6% of all hip and groin injuries and caused significantly more games missed than extra-articular injuries.2

In both minor and major league players, for all reported positions at the time of hip or groin injury, infield players collectively were more commonly injured than outfielders, batters, or base runners, and fielding was the most common activity being performed at the time of injury. The pitcher’s mound was the most common single location for injuries and these players had the longest time missed following injury. The correlation between hip and groin pathology and upper extremity injuries in overhead athletes has been discussed in previous studies.12,21 Interestingly, we found that the specific location on the field with the highest incidence of hip and groin injuries was the pitcher’s mound. As we follow these players over time, a future correlation between the incidence of hip and groin injuries and the incidence of shoulder and elbow injuries may be noted. A noncontact injury was the most frequent mechanism of injury. This corroborates the finding that muscle strains and contusions made up the majority of injuries in this series. Other series on hip injuries have also found that noncontact mechanisms are common.3

Although this was one of the first studies exploring the epidemiology of hip and groin injury, there are some limitations of this study. The retrospective nature of this study relied upon the reporting of injuries in the MLB database. As such, there may be underreporting of injuries into the official database by players or medical staff for a variety of reasons. Differences in technique for diagnosis and treatment among the medical staff for different teams were not controlled for. Due to the wide range of hip and groin pathology, and the often difficult diagnosis, a specific injury was not always provided. Therefore, the category of “other” hip injury was entered in to the database when symptoms were nonspecific or not all details were provided. Fortunately, this category made up a small percentage of the reported injuries, but does remain a confounding factor in describing the etiology of hip injuries in these players. Our data were taken from professional baseball players only, and so we cannot recommend extrapolation to other sports or nonprofessional baseball athletes.

Despite the inherent limitations of reporting registry data, this study serves as the initial report of the occurrence of hip and groin injuries in professional baseball players, and improves our knowledge of the positions and situations that put players at most risk for these injuries. An understanding of the overall epidemiology of these injuries serves as a platform for more focused research in this area in the future. We can now focus research on specific positions, such as pitchers, that have a high incidence of injury to determine the physiologic and environmental factors which put them at higher risk for injury in general and for more significant injuries with more days missed. This information can help to guide position-specific training programs for injury prevention as well as improve rehabilitation protocols for more efficient recovery and return to sports.

1. Amenabar T, O’Donnell J. Return to sport in Australian football league footballers after hip arthroscopy and midterm outcome. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(7):1188-1194.

2. Epstein DM, McHugh M, Yorio M, Neri B. Intra-articular hip injuries in national hockey league players: a descriptive epidemiological study. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):343-348.

3. Feeley BT, Powell JW, Muller MS, Barnes RP, Warren RF, Kelly BT. Hip injuries and labral tears in the national football league. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(11):2187-2195.

4. Li X, Zhou H, Williams P, et al. The epidemiology of single season musculoskeletal injuries in professional baseball. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2013;5(1):e3.

5. Meyers WC, Foley DP, Garrett WE, Lohnes JH, Mandlebaum BR. Management of severe lower abdominal or inguinal pain in high-performance athletes. PAIN (Performing Athletes with Abdominal or Inguinal Neuromuscular Pain Study Group). Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(1):2-8.

6. Moorman CT 3rd, Warren RF, Hershman EB, et al. Traumatic posterior hip subluxation in American football. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(7):1190-1196.

7. Philippon M, Schenker M, Briggs K, Kuppersmith D. Femoroacetabular impingement in 45 professional athletes: associated pathologies and return to sport following arthroscopic decompression. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(7):908-914.

8. Posner M, Cameron KL, Wolf JM, Belmont PJ Jr, Owens BD. Epidemiology of Major League Baseball injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(8):1676-1680.

9. Werner J, Hagglund M, Walden M, Ekstrand J. UEFA injury study: a prospective study of hip and groin injuries in professional football over seven consecutive seasons. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(13):1036-1040.

10. Conte S, Requa RK, Garrick JG. Disability days in major league baseball. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):431-436.

11. Ellenbecker TS, Ellenbecker GA, Roetert EP, Silva RT, Keuter G, Sperling F. Descriptive profile of hip rotation range of motion in elite tennis players and professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(8):1371-1376.

12. Klingenstein GG, Martin R, Kivlan B, Kelly BT. Hip injuries in the overhead athlete. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(6):1579-1585.

13. McCarthy J, Barsoum W, Puri L, Lee JA, Murphy S, Cooke P. The role of hip arthroscopy in the elite athlete. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003(406):71-74.

14. Anderson K, Strickland SM, Warren R. Hip and groin injuries in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):521-533.

15. Boykin RE, Patterson D, Briggs KK, Dee A, Philippon MJ. Results of arthroscopic labral reconstruction of the hip in elite athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2296-2301.

16. Malviya A, Paliobeis CP, Villar RN. Do professional athletes perform better than recreational athletes after arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(8):2477-2483.

17. McDonald JE, Herzog MM, Philippon MJ. Performance outcomes in professional hockey players following arthroscopic treatment of FAI and microfracture of the hip. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):915-919.

18. McDonald JE, Herzog MM, Philippon MJ. Return to play after hip arthroscopy with microfracture in elite athletes. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(2):330-335.

19. Philippon MJ, Weiss DR, Kuppersmith DA, Briggs KK, Hay CJ. Arthroscopic labral repair and treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in professional hockey players. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):99-104.

20. Alradwan H, Philippon MJ, Farrokhyar F, et al. Return to preinjury activity levels after surgical management of femoroacetabular impingement in athletes. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(10):1567-1576.

21. Stodden DF, Langendorfer SJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Kinematic constraints associated with the acquisition of overarm throwing part I: step and trunk actions. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2006;77(4):417-427.

22. Hammoud S, Bedi A, Voos JE, Mauro CS, Kelly BT. The recognition and evaluation of patterns of compensatory injury in patients with mechanical hip pain. Sports Health. 2014;6(2):108-118.

Injuries around the hip and groin occurring in professional baseball players can present as muscle strains, avulsions, contusions, hip subluxations or dislocations, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) causing labral tears or chondral defects, and athletic pubalgia.1-9 Several recent articles have reported on the epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries in Major League Baseball (MLB) players4,8,10 but with little attention to injuries to the hip and groin, likely because prior studies show only a 6.3% overall incidence for these injuries, much less than the more commonly discussed shoulder or elbow injuries.8 Despite the lower proportion of hip and groin injuries overall, these injuries lead to a relatively long period of disability for the players and often have a high rate of recurrence.4,8,9

The important contribution of hip mechanics and the surrounding muscular function in the kinetic chain during overhead athletic activities, such as a tennis serve or throwing, has recently been discussed.11,12 In sports requiring overhead activities, trunk rotation is a key component to generating force, and hip internal and external rotation is necessary for this trunk rotation to occur.12,13 Alterations in hip morphology causing constrained motion, as seen in FAI, may predispose an overhead throwing athlete to intra-articular injury such as labral tears or chondral injuries, or to a compensatory movement pattern causing an extra-articular soft tissue injury about the hip.12 Decreased hip range of motion may also lead to increased forces across the upper extremity during the throwing motion, which puts the shoulder and elbow at increased risk of injury.12

Increased awareness of hip and groin injuries, advances in diagnostic imaging, and an understanding of the relationship between the throwing motion in baseball and hip mechanics have improved our ability to appropriately identify and treat athletes with injuries of the hip and groin. Several studies on hip and groin injuries in elite athletes treated both operatively and nonoperatively have reported a high rate of return to sport.3,7,14-19 A systematic review on return to sport following hip arthroscopy for intra-articular pathology associated with FAI showed a 95% return to sport rate and a 92% rate of return to pre-injury level of play in a subgroup of professional athletes in 9 studies.20

Despite the large body of literature on upper extremity injuries, there is no study specifically focusing on the epidemiology of hip and groin injuries in MLB or Minor League Baseball (MiLB) players. The incidence of all injuries in professional baseball players has steadily increased over the last 2 decades,8 and the reported incidence of hip and groin injuries will likely increase as well. The current incidence of this injury, the positions most at risk, the mechanism of injury, and the time to return to sport are important to understand given the large number of players who participate in baseball not only at a professional level, but also at an amateur level, where this information may also be applicable. This information could improve our efforts at prevention and rehabilitation of these injuries, and can guide efforts to counsel and train players at high risk of a hip or groin injury. To address this gap in the literature, the purpose of this study was to describe the epidemiology of hip and groin injuries in MLB and MiLB players from 2011 to 2014.

Materials and Methods

Population and Sample

US MLB is comprised of the major and minor leagues. The major leagues are divided into 30 clubs, with 25 active players, for a total of 750 active players. Each club has a 40-man roster consisting of 25 active players and up to 15 additional players who are either not active or optioned to the minor leagues. The minor leagues are comprised of a network of over 200 clubs that are each affiliated with a major league club, and organized by geography and level of play. The minor leagues consist of roughly 7500 players, of whom about 6500 are actively playing at any given time. The entire population of players in the MLB who sustained a hip or groin injury over the study period was eligible for this study.

Data

The MLB’s Health and Injury Tracking System (HITS) is a centralized database that contains the de-identified medical data from the electronic medical record (EMR) system. Data on all injuries are entered into the EMR by each team’s certified athletic trainer. An injury is defined as any physical complaint sustained by a player that affects or limits participation in any aspect of baseball-related activity (eg, game, practice, warm-up, conditioning, weight training). The data extracted from HITS only relates to injuries that resulted in lost game time for a player and that occurred during spring training, regular season, or postseason play; off-season injuries were not included. Injury events that were classified as “season-ending” were not included in the analysis of assessing days missed because many of these players may not have been cleared to play until the beginning of the following season. For each injury, data were collected on the diagnosis, body part, activity, location, and date of injury.

Materials and Methods

Hip and groin injuries were defined as cases having a body region variable classified as “hip/groin” or a Sports Medicine Diagnostic Coding System (SMDCS) that included any “adductor” or “hernia” or “hip pointer” labels. Cases categorized as inguinal and femoral hernia (n = 26) and testicular contusions (n = 87) were excluded. Characteristics about each hip and groin injury were also extracted from HITS. These variables included level of play, player position (activity at the time of injury), field location, injury mechanism, chronicity of the injury, and days missed. Chronicity of the injury was documented as acute, overuse, or undetermined. For level of play, the injury event was categorized as the league in which the game was played when the injury occurred. Players were excluded if they had an unknown level of play or were in the amateur league. The injuries of the hip and groin were further classified as intra-articular and extra-articular. Treatment for each injury was characterized as surgical or nonsurgical, and correlated with days missed for each type of injury.

Statistical Analysis

Data for the 2011-2014 seasons were combined, and results presented for all players and separately for MiLB and MLB. Frequencies and comparative analyses for hip and groin injuries were performed across the aforementioned injury characteristics. The distribution of days missed for the variables considered was often skewed to the right, even after excluding the season-ending injuries; hence, the mean days missed was often larger than the median days missed. Reporting the median would allow for a robust estimate of the expected number of days missed, but would down weight those instances when hip and groin injuries result in much longer missed days, as reflected by the mean. Because of the importance of the days missed measure for professional baseball, both the mean and median are presented. Chi-square tests were used to test the hypothesis of equal proportions between the various categories of hip and groin characteristics, with statistical significance determined at the P = .05 level.

In order to estimate exposure, the average number of players per team per game was calculated based on analysis of regular season game participation via box scores that are publicly available. This average number over a season, multiplied by the number of team games at each professional level of baseball, was used as an estimate of athlete exposures in order to provide rates comparable to those of other injury surveillance systems. Injury rates were reported as injuries per 1000 athlete-exposures (AE) for those hip and groin injuries that occurred during the regular season. It should be noted that the number of regular season hip and groin injuries and the subsequent AE rates are based on injuries that were deemed work-related during the regular season. This does not necessarily only include injuries occurring during the course of a game, but injuries in game preparation as well. Due to the variations in spring training games and fluctuating rosters, an exposure rate could not be calculated for spring training hip and groin injuries.

Data analysis was performed in the R statistical computing Environment (R Core Team 2014). Study procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Results

Overall Summary

A total of 1823 hip and groin injuries occurred from 2011-2014, with 83% occurring in MiLB and 17% occurring in MLB (Table 1). There were 1146 acute injuries, 252 overuse injuries, and 425 injuries of undetermined chronicity. The average age of players experiencing a hip and groin injury in MiLB was 22.9 years compared to 29.7 years in MLB. Of the 1514 hip and groin injuries in MiLB, 76 (5.0%) required surgery and of the 309 hip and groin injuries in MLB, 24 (7.8%) required surgery. Compared to league-wide injury events, hip and groin injuries ranked 6th highest in prevalence in MiLB and 8th highest in prevalence in MLB, accounting for 5.4% and 5.6%, respectively, of the 28,116 MiLB and 5507 MLB injury events that occurred between 2011-2014.