User login

Emergency hernia surgery risk predicted by access, age, and race

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Age and access to medical care may be key drivers of emergency surgery for ventral hernia repair, a large retrospective study has found.

Patients who do not have health insurance, are advanced in age, are black or Hispanic, or have unrelated health problems are at significantly higher risk than other patients with hernias of having emergency surgery for ventral hernia repair, facing a higher risk of death, a higher cost, and a longer hospital stay, Dr. Lindsey Wolf said at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress. “This study demonstrates persistent disparities in access to elective surgery care that must be understood and mitigated,” she said. “The strongest predictor was being uninsured. The self-pay group had an odds ratio of 3.5 for undergoing emergency surgery, compared with those who were primarily insured.”

The goal of the study was to identify patient and hospital factors associated with emergency ventral hernia surgery in the U.S. population, said Dr. Wolf of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “Prior studies that have been done on predictors of emergency repair are from universally insured populations,” she said. One was a national cohort study in Denmark, and another involved the Veterans Affairs population, she said. “Both of these identified several demographic and clinical risk factors for emergency hernia repair,” she said.

The current Brigham and Women’s study involved a retrospective cross-sectional data analysis of approximately 453,000 elective and emergency ventral hernia repairs performed from 2003 to 2011 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Any cases that involved a trauma diagnosis were excluded. Forty percent of the cases in the sample were emergency admissions.

When considering the effect of age, the investigators found that the aged 65-75 group had the lowest risk of emergency hernia surgery of all age groups with an odds ratio of 0.77, compared with those under 45 years. Those aged 85 and older, however, had the highest risk of all age groups with an odds ratio of 2.23. “The proportion of the cohort undergoing emergency surgery really increases drastically with age after 75 years,” Dr. Wolf said.

Other factors that had an impact on emergency hernia repair were Medicaid coverage (OR, 1.29, compared with private insurance), black race (OR, 1.64, compared with white race), Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.44, compared with non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity), and comorbidities, ranging from 1.13 for one comorbidity to 1.68 for three or more, compared with none.

The study also elucidated a few consequences of emergency ventral hernia repair: 2.58 times higher odds of death, a 15% greater cost per hospital stay, and 26% longer hospital stays.

“Looking forward there are both patient and provider areas to target,” Dr. Wolf said. “For patients, interventions must be designed to populations that may have poor access to elective surgical services.” She acknowledged that race was a strong predictor, “but race is a social construct that may be a proxy to many barriers to access and care.”

The study findings may also help inform surgeons on when to operate on ventral hernias. “In the absence of any clinical guidelines for when a hernia should be repaired, our results with regard to age and multiple comorbidities may assist surgeons in risk stratifying patients when considering [whether] to perform an elective repair,” she said.

Dr. Wolf and her coauthors had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Age and access to medical care may be key drivers of emergency surgery for ventral hernia repair, a large retrospective study has found.

Patients who do not have health insurance, are advanced in age, are black or Hispanic, or have unrelated health problems are at significantly higher risk than other patients with hernias of having emergency surgery for ventral hernia repair, facing a higher risk of death, a higher cost, and a longer hospital stay, Dr. Lindsey Wolf said at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress. “This study demonstrates persistent disparities in access to elective surgery care that must be understood and mitigated,” she said. “The strongest predictor was being uninsured. The self-pay group had an odds ratio of 3.5 for undergoing emergency surgery, compared with those who were primarily insured.”

The goal of the study was to identify patient and hospital factors associated with emergency ventral hernia surgery in the U.S. population, said Dr. Wolf of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “Prior studies that have been done on predictors of emergency repair are from universally insured populations,” she said. One was a national cohort study in Denmark, and another involved the Veterans Affairs population, she said. “Both of these identified several demographic and clinical risk factors for emergency hernia repair,” she said.

The current Brigham and Women’s study involved a retrospective cross-sectional data analysis of approximately 453,000 elective and emergency ventral hernia repairs performed from 2003 to 2011 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Any cases that involved a trauma diagnosis were excluded. Forty percent of the cases in the sample were emergency admissions.

When considering the effect of age, the investigators found that the aged 65-75 group had the lowest risk of emergency hernia surgery of all age groups with an odds ratio of 0.77, compared with those under 45 years. Those aged 85 and older, however, had the highest risk of all age groups with an odds ratio of 2.23. “The proportion of the cohort undergoing emergency surgery really increases drastically with age after 75 years,” Dr. Wolf said.

Other factors that had an impact on emergency hernia repair were Medicaid coverage (OR, 1.29, compared with private insurance), black race (OR, 1.64, compared with white race), Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.44, compared with non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity), and comorbidities, ranging from 1.13 for one comorbidity to 1.68 for three or more, compared with none.

The study also elucidated a few consequences of emergency ventral hernia repair: 2.58 times higher odds of death, a 15% greater cost per hospital stay, and 26% longer hospital stays.

“Looking forward there are both patient and provider areas to target,” Dr. Wolf said. “For patients, interventions must be designed to populations that may have poor access to elective surgical services.” She acknowledged that race was a strong predictor, “but race is a social construct that may be a proxy to many barriers to access and care.”

The study findings may also help inform surgeons on when to operate on ventral hernias. “In the absence of any clinical guidelines for when a hernia should be repaired, our results with regard to age and multiple comorbidities may assist surgeons in risk stratifying patients when considering [whether] to perform an elective repair,” she said.

Dr. Wolf and her coauthors had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Age and access to medical care may be key drivers of emergency surgery for ventral hernia repair, a large retrospective study has found.

Patients who do not have health insurance, are advanced in age, are black or Hispanic, or have unrelated health problems are at significantly higher risk than other patients with hernias of having emergency surgery for ventral hernia repair, facing a higher risk of death, a higher cost, and a longer hospital stay, Dr. Lindsey Wolf said at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress. “This study demonstrates persistent disparities in access to elective surgery care that must be understood and mitigated,” she said. “The strongest predictor was being uninsured. The self-pay group had an odds ratio of 3.5 for undergoing emergency surgery, compared with those who were primarily insured.”

The goal of the study was to identify patient and hospital factors associated with emergency ventral hernia surgery in the U.S. population, said Dr. Wolf of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “Prior studies that have been done on predictors of emergency repair are from universally insured populations,” she said. One was a national cohort study in Denmark, and another involved the Veterans Affairs population, she said. “Both of these identified several demographic and clinical risk factors for emergency hernia repair,” she said.

The current Brigham and Women’s study involved a retrospective cross-sectional data analysis of approximately 453,000 elective and emergency ventral hernia repairs performed from 2003 to 2011 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Any cases that involved a trauma diagnosis were excluded. Forty percent of the cases in the sample were emergency admissions.

When considering the effect of age, the investigators found that the aged 65-75 group had the lowest risk of emergency hernia surgery of all age groups with an odds ratio of 0.77, compared with those under 45 years. Those aged 85 and older, however, had the highest risk of all age groups with an odds ratio of 2.23. “The proportion of the cohort undergoing emergency surgery really increases drastically with age after 75 years,” Dr. Wolf said.

Other factors that had an impact on emergency hernia repair were Medicaid coverage (OR, 1.29, compared with private insurance), black race (OR, 1.64, compared with white race), Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.44, compared with non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity), and comorbidities, ranging from 1.13 for one comorbidity to 1.68 for three or more, compared with none.

The study also elucidated a few consequences of emergency ventral hernia repair: 2.58 times higher odds of death, a 15% greater cost per hospital stay, and 26% longer hospital stays.

“Looking forward there are both patient and provider areas to target,” Dr. Wolf said. “For patients, interventions must be designed to populations that may have poor access to elective surgical services.” She acknowledged that race was a strong predictor, “but race is a social construct that may be a proxy to many barriers to access and care.”

The study findings may also help inform surgeons on when to operate on ventral hernias. “In the absence of any clinical guidelines for when a hernia should be repaired, our results with regard to age and multiple comorbidities may assist surgeons in risk stratifying patients when considering [whether] to perform an elective repair,” she said.

Dr. Wolf and her coauthors had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

AT THE ACADEMIC SURGICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Disparities among patients more likely to get emergency rather than elective ventral hernia repair include race, insurance status, and advanced age.

Major finding: Among demographic groups with a significantly higher likelihood of undergoing emergency ventral hernia repair were blacks (odds ratio, 1.64), Hispanics (OR, 1.44), and people over age 85 (OR, 2.23).

Data source: Nationwide Inpatient Sample of 453,000 adults who had inpatient ventral hernia repair from 2003 to 2011.

Disclosures: The study authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ACOG pushes for contraception measures in Core Quality Measures Collaborative

Disagreement over quality measures regarding contraception has led the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to withhold its imprimatur from the Core Quality Measures Collaborative.

“Although ACOG representatives did participate in the process to select measures to be included in the Core Quality Measures Collaborative process, ACOG did not choose to be recognized for participation until further agreement can be made regarding quality measures related to effective contraceptives and immediate postpartum contraception,” Dr. Barbara Levy, ACOG vice president of health policy, said in an interview. “ACOG believes that measures can help create accountability among health systems regarding contraceptive access, providing an opportunity to prevent unintended pregnancies.”

The Core Quality Measures Collaborative is lead by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and America’s Health Insurance Plans, with input from the National Quality Forum, medical societies, employer groups, and consumer groups, with the goal of building a uniform set of quality measures to be used by both public and private payers in value-based payment structures.

The first seven sets of measures under the collaborative were announced Feb. 16; ob.gyn. measures were included in this limited release.

For ob.gyn., the measures are blocked into two sets. Metrics in the ambulatory care setting look at frequency of ongoing prenatal care, cervical and breast cancer screening, chlamydia screening and follow-up, and appropriate work-up prior to endometrial ablation. Measures in the hospital/acute care setting include incidence of episiotomy, elective delivery, cesarean sections, antenatal steroids, and exclusive breastfeeding.

Four areas identified for future development include physician-level urinary incontinence screening, more on cesarean sections, Tdap/influenza administration in pregnancy, and HIV screening of STI patients.

ACOG said it will continue to push for the inclusion of contraception measures as part of the measures, particularly as access to them continues to be an issue.

“Although the Affordable Care Act requires insurance plans to cover the full range of Food and Drug Administration–approved contraceptive methods, we know that implementation of this provision has not been universal, and some women’s needs are currently unmet,” Dr. Levy said. “Because of this, ACOG continues to advocate for quality measures that will lead to meaningful improvements in access to effective contraception and immediate postpartum contraception. It is our hope that we can advance the commitment of commercial health insurance plans to promoting the most effective contraceptive methods in a way that meets the needs of more American women.”

Disagreement over quality measures regarding contraception has led the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to withhold its imprimatur from the Core Quality Measures Collaborative.

“Although ACOG representatives did participate in the process to select measures to be included in the Core Quality Measures Collaborative process, ACOG did not choose to be recognized for participation until further agreement can be made regarding quality measures related to effective contraceptives and immediate postpartum contraception,” Dr. Barbara Levy, ACOG vice president of health policy, said in an interview. “ACOG believes that measures can help create accountability among health systems regarding contraceptive access, providing an opportunity to prevent unintended pregnancies.”

The Core Quality Measures Collaborative is lead by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and America’s Health Insurance Plans, with input from the National Quality Forum, medical societies, employer groups, and consumer groups, with the goal of building a uniform set of quality measures to be used by both public and private payers in value-based payment structures.

The first seven sets of measures under the collaborative were announced Feb. 16; ob.gyn. measures were included in this limited release.

For ob.gyn., the measures are blocked into two sets. Metrics in the ambulatory care setting look at frequency of ongoing prenatal care, cervical and breast cancer screening, chlamydia screening and follow-up, and appropriate work-up prior to endometrial ablation. Measures in the hospital/acute care setting include incidence of episiotomy, elective delivery, cesarean sections, antenatal steroids, and exclusive breastfeeding.

Four areas identified for future development include physician-level urinary incontinence screening, more on cesarean sections, Tdap/influenza administration in pregnancy, and HIV screening of STI patients.

ACOG said it will continue to push for the inclusion of contraception measures as part of the measures, particularly as access to them continues to be an issue.

“Although the Affordable Care Act requires insurance plans to cover the full range of Food and Drug Administration–approved contraceptive methods, we know that implementation of this provision has not been universal, and some women’s needs are currently unmet,” Dr. Levy said. “Because of this, ACOG continues to advocate for quality measures that will lead to meaningful improvements in access to effective contraception and immediate postpartum contraception. It is our hope that we can advance the commitment of commercial health insurance plans to promoting the most effective contraceptive methods in a way that meets the needs of more American women.”

Disagreement over quality measures regarding contraception has led the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to withhold its imprimatur from the Core Quality Measures Collaborative.

“Although ACOG representatives did participate in the process to select measures to be included in the Core Quality Measures Collaborative process, ACOG did not choose to be recognized for participation until further agreement can be made regarding quality measures related to effective contraceptives and immediate postpartum contraception,” Dr. Barbara Levy, ACOG vice president of health policy, said in an interview. “ACOG believes that measures can help create accountability among health systems regarding contraceptive access, providing an opportunity to prevent unintended pregnancies.”

The Core Quality Measures Collaborative is lead by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and America’s Health Insurance Plans, with input from the National Quality Forum, medical societies, employer groups, and consumer groups, with the goal of building a uniform set of quality measures to be used by both public and private payers in value-based payment structures.

The first seven sets of measures under the collaborative were announced Feb. 16; ob.gyn. measures were included in this limited release.

For ob.gyn., the measures are blocked into two sets. Metrics in the ambulatory care setting look at frequency of ongoing prenatal care, cervical and breast cancer screening, chlamydia screening and follow-up, and appropriate work-up prior to endometrial ablation. Measures in the hospital/acute care setting include incidence of episiotomy, elective delivery, cesarean sections, antenatal steroids, and exclusive breastfeeding.

Four areas identified for future development include physician-level urinary incontinence screening, more on cesarean sections, Tdap/influenza administration in pregnancy, and HIV screening of STI patients.

ACOG said it will continue to push for the inclusion of contraception measures as part of the measures, particularly as access to them continues to be an issue.

“Although the Affordable Care Act requires insurance plans to cover the full range of Food and Drug Administration–approved contraceptive methods, we know that implementation of this provision has not been universal, and some women’s needs are currently unmet,” Dr. Levy said. “Because of this, ACOG continues to advocate for quality measures that will lead to meaningful improvements in access to effective contraception and immediate postpartum contraception. It is our hope that we can advance the commitment of commercial health insurance plans to promoting the most effective contraceptive methods in a way that meets the needs of more American women.”

STS: Minimizing LVAD pump thrombosis poses new challenges

PHOENIX – Cardiothoracic surgeons who implant left ventricular assist devices in patients with failing hearts remain at a loss to fully explain why they started seeing a sharp increase in thrombus clogging in these devices in 2012, but nevertheless they are gaining a better sense of how to minimize the risk.

Three key principles for minimizing thrombosis risk are selecting the right patients to receive left ventricular assist devices (LVAD), applying optimal management strategies once patients receive a LVAD, and maintaining adequate flow of blood through the pump, Dr. Francis D. Pagani said in a talk at a session devoted to pump thrombosis at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Other critical aspects include optimal implantation technique, quick work-up of patients to rule out reversible LVAD inflow or outflow problems once pump thrombosis is suspected, and ceasing medical therapy of the thrombosis if it proves ineffective and instead progress to surgical pump exchange, pump explantation, or heart transplant when necessary, said Dr. Ahmet Kilic, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Ohio State University, Columbus.

Another key issue is that, now that the pump thrombosis incidence is averaging about 10% of LVAD recipients, with an incidence rate during 2-year follow-up as high as 24% reported from one series, surgeons and physicians who care for LVAD patients must have a high index of suspicion and routinely screen LVAD recipients for early signs of pump thrombosis. The best way to catch pump thrombosis early seems to be by regularly measuring patients’ serum level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), said Dr. Robert L. Kormos, professor of surgery and director of the artificial heart program at the University of Pittsburgh.

“We measure LDH on most clinic visits, whether or not the patient has an indication of pump thrombosis. We need to screen [LDH levels] much more routinely than we used to,” he said during the session. “Elevated LDH is probably the first and most reliable early sign, but you need to also assess LDH isoenzymes because we’ve had patients with an elevation but no sign of pump thrombosis, and their isoenzymes showed that the increased LDH was coming from their liver,” Dr. Kormos said in an interview.

Although serial measurements and isoenzyme analysis can establish a sharp rise in heart-specific LDH in an individual patient, a report at the meeting documented that in a series of 53 patients with pump thrombosis treated at either of two U.S. centers, an LDH level of at least 1,155 IU/L flagged pump thrombosis with a fairly high sensitivity and specificity. This LDH level is roughly five times the upper limit of normal, noted Dr. Pagani, professor of surgery and surgical director of adult heart transplantation at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a senior author on this report.

But prior to this report Dr. Kormos said that he regarded a LDH level of 600-800 IU/L as enough of an elevation above normal to prompt concern and investigation. And he criticized some LVAD programs that allow LDH levels to rise much higher.

“I know of clinicians who see a LDH of 1,500-2,000 IU/L but the patient seems okay and they wonder if they should change out the pump. For me, it’s a no brainer. Others try to list a patient like this for a heart transplant so they can avoid doing a pump exchange. I think that’s dangerous; it risks liver failure or renal failure. I would not sit on any LVAD that is starting to produce signs of hemolysis syndrome, but some places do this,” Dr. Kormos said in an interview.

“Pump thrombosis probably did not get addressed in as timely a fashion as it should have been” when it was first seen on the rise in 2012, noted Dr. James K. Kirklin, professor of surgery and director of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. “It is now being addressed, and we realize that this is not just a pump problem but also involves patient factors and management factors that we need to learn more about. We are quite ignorant of the patient factors and understanding their contributions to bleeding and thrombosis,” said Dr. Kirklin. He also acknowledged that whatever role the current generation of LVAD pumps play in causing thrombosis will not quickly resolve.

“I’m looking forward to a new generation of pumps, but the pumps we have today will probably remain for another 3-5 years.”

The issue of LVAD pump thrombosis first came into clear focus with publication at the start of 2014 of a report that tracked its incidence from 2004 to mid-2013 at three U.S. centers that had placed a total of 895 LVADs in 837 patients. The annual rate of new episodes of pump thrombosis jumped from about 1%-2% of LVAD recipients throughout the first part of the study period through the end of 2011, to an annual rate of about 10% by mid 2013 (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:33-40).

“The inflection occurred in about 2012,” noted Dr. Nicholas G. Smedira, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic. “No one has figured out why” the incidence suddenly spiked starting in 2012 and intensified in 2013, he said. This epidemic of pump thrombosis has produced “devastating complications” that have led to multiple readmissions and reduced cost-effectiveness of LVADs and has affected how the heart transplant community allocates hearts, Dr. Smedira said during his talk at the session. He noted that once the surge in pump thrombosis started, the timing of the appearance of significant thrombus shifted earlier, often occurring within 2-3 months after LVAD placement. There now is “increasing device-related pessimism” and increasing demoralization among clinicians because of this recurring complication, he said.

More recent data show the trend toward increasingly higher rates of pump thrombosis continuing through the end of 2013, with the situation during 2014 a bit less clear. Late last year, data from 9,808 U.S. patients who received an LVAD and entered the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) showed that the incidence of pump thrombosis during the first 6 months following an implant rose from 1% in 2008 to 2% in 2009 and in 2010, 4% in 2011, 7% in 2012, 8% in 2013, and then eased back to 5% in the first half of 2014 (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015 Dec;34[12]:1515-26). The annual rate rose from 2% in 2008 to a peak of 11% in 2013, with 12-month data from 2014 not yet available at the time of this report.

“The modest reduction of observed pump thrombosis at 6 months during 2014 has occurred in a milieu of heightened intensity of anti-coagulation management, greater surgical awareness of optimal pump implantation and positioning and pump speed management. Thus, one may speculate that current thrombosis risk-mitigation strategies have contributed to reducing but not eliminating the increased thrombosis risk observed since 2011,” concluded the authors of the report.

Surgeons and cardiologists must now have a high index of suspicion for pump thrombosis in LVAD recipients, and be especially on the lookout for four key flags of a problem, said Dr. Kormos. The first is a rising LDH level, but additional flags include an isolated power elevation that doesn’t correlate with anything else, evidence of hemolysis, and new-onset heart failure symptoms. These can occur individually or in some combination. He recommended following a diagnostic algorithm first presented in 2013 that remains very valid today (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013 July;32[7]:667-70).

Dr. Kormos also highlighted that the presentation of pump thrombosis can differ between the two LVADs most commonly used in U.S. practice, the HeartMate II and the HeartWare devices. A LDH elevation is primarily an indicator for HeartMate II, while both that model and the HeartWare device show sustained, isolated power elevations when thrombosis occurs.

Dr. Pagani, Dr. Kirklin, and Dr. Smedira had no disclosures. Dr. Kormos has received travel support from HeartWare. Dr. Kilic has been a consultant to Thoratec and a speaker on behalf of Baxter International.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Dr. Hossein Almassi, FCCP, comments: With improvements in technology and development of rotary pumps, there has been a significant growth in the use of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) for treatment of end stage heart failure with a parallel improvement in patients’ survival and the quality of life.

|

| Dr. Hossein Almassi |

The authors of this report presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the STS, are authorities in the field of MCS outlining the observed increase in pump thrombosis noted in 2012. The sharp increase in the thrombosis rate is different from the lower incidence seen in the preapproval stage of the pump trial.

It should be noted that the report is related mainly to the HeatMate II left ventricular assist device (LVAD) and not the more recently implanted HeartWare device.

The diagnostic algorithm outlined in the accompanying reference (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013 July;32[7]:667-70) regarding the diagnosis and management of suspected pump thrombosis is worth reading with the main criteria heralding a potential pump thrombosis being 1)sustained pump power elevation, 2) elevation of cardiac LDH or plasma-free hemoglobin, 3) hemolysis, and 4) symptoms of heart failure.

With further refinements in technology, the field of MCS is awaiting the development of newer LVAD devices that would mitigate the serious problem of pump thrombosis.

Dr. Hossein Almassi, FCCP, comments: With improvements in technology and development of rotary pumps, there has been a significant growth in the use of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) for treatment of end stage heart failure with a parallel improvement in patients’ survival and the quality of life.

|

| Dr. Hossein Almassi |

The authors of this report presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the STS, are authorities in the field of MCS outlining the observed increase in pump thrombosis noted in 2012. The sharp increase in the thrombosis rate is different from the lower incidence seen in the preapproval stage of the pump trial.

It should be noted that the report is related mainly to the HeatMate II left ventricular assist device (LVAD) and not the more recently implanted HeartWare device.

The diagnostic algorithm outlined in the accompanying reference (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013 July;32[7]:667-70) regarding the diagnosis and management of suspected pump thrombosis is worth reading with the main criteria heralding a potential pump thrombosis being 1)sustained pump power elevation, 2) elevation of cardiac LDH or plasma-free hemoglobin, 3) hemolysis, and 4) symptoms of heart failure.

With further refinements in technology, the field of MCS is awaiting the development of newer LVAD devices that would mitigate the serious problem of pump thrombosis.

Dr. Hossein Almassi, FCCP, comments: With improvements in technology and development of rotary pumps, there has been a significant growth in the use of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) for treatment of end stage heart failure with a parallel improvement in patients’ survival and the quality of life.

|

| Dr. Hossein Almassi |

The authors of this report presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the STS, are authorities in the field of MCS outlining the observed increase in pump thrombosis noted in 2012. The sharp increase in the thrombosis rate is different from the lower incidence seen in the preapproval stage of the pump trial.

It should be noted that the report is related mainly to the HeatMate II left ventricular assist device (LVAD) and not the more recently implanted HeartWare device.

The diagnostic algorithm outlined in the accompanying reference (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013 July;32[7]:667-70) regarding the diagnosis and management of suspected pump thrombosis is worth reading with the main criteria heralding a potential pump thrombosis being 1)sustained pump power elevation, 2) elevation of cardiac LDH or plasma-free hemoglobin, 3) hemolysis, and 4) symptoms of heart failure.

With further refinements in technology, the field of MCS is awaiting the development of newer LVAD devices that would mitigate the serious problem of pump thrombosis.

PHOENIX – Cardiothoracic surgeons who implant left ventricular assist devices in patients with failing hearts remain at a loss to fully explain why they started seeing a sharp increase in thrombus clogging in these devices in 2012, but nevertheless they are gaining a better sense of how to minimize the risk.

Three key principles for minimizing thrombosis risk are selecting the right patients to receive left ventricular assist devices (LVAD), applying optimal management strategies once patients receive a LVAD, and maintaining adequate flow of blood through the pump, Dr. Francis D. Pagani said in a talk at a session devoted to pump thrombosis at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Other critical aspects include optimal implantation technique, quick work-up of patients to rule out reversible LVAD inflow or outflow problems once pump thrombosis is suspected, and ceasing medical therapy of the thrombosis if it proves ineffective and instead progress to surgical pump exchange, pump explantation, or heart transplant when necessary, said Dr. Ahmet Kilic, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Ohio State University, Columbus.

Another key issue is that, now that the pump thrombosis incidence is averaging about 10% of LVAD recipients, with an incidence rate during 2-year follow-up as high as 24% reported from one series, surgeons and physicians who care for LVAD patients must have a high index of suspicion and routinely screen LVAD recipients for early signs of pump thrombosis. The best way to catch pump thrombosis early seems to be by regularly measuring patients’ serum level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), said Dr. Robert L. Kormos, professor of surgery and director of the artificial heart program at the University of Pittsburgh.

“We measure LDH on most clinic visits, whether or not the patient has an indication of pump thrombosis. We need to screen [LDH levels] much more routinely than we used to,” he said during the session. “Elevated LDH is probably the first and most reliable early sign, but you need to also assess LDH isoenzymes because we’ve had patients with an elevation but no sign of pump thrombosis, and their isoenzymes showed that the increased LDH was coming from their liver,” Dr. Kormos said in an interview.

Although serial measurements and isoenzyme analysis can establish a sharp rise in heart-specific LDH in an individual patient, a report at the meeting documented that in a series of 53 patients with pump thrombosis treated at either of two U.S. centers, an LDH level of at least 1,155 IU/L flagged pump thrombosis with a fairly high sensitivity and specificity. This LDH level is roughly five times the upper limit of normal, noted Dr. Pagani, professor of surgery and surgical director of adult heart transplantation at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a senior author on this report.

But prior to this report Dr. Kormos said that he regarded a LDH level of 600-800 IU/L as enough of an elevation above normal to prompt concern and investigation. And he criticized some LVAD programs that allow LDH levels to rise much higher.

“I know of clinicians who see a LDH of 1,500-2,000 IU/L but the patient seems okay and they wonder if they should change out the pump. For me, it’s a no brainer. Others try to list a patient like this for a heart transplant so they can avoid doing a pump exchange. I think that’s dangerous; it risks liver failure or renal failure. I would not sit on any LVAD that is starting to produce signs of hemolysis syndrome, but some places do this,” Dr. Kormos said in an interview.

“Pump thrombosis probably did not get addressed in as timely a fashion as it should have been” when it was first seen on the rise in 2012, noted Dr. James K. Kirklin, professor of surgery and director of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. “It is now being addressed, and we realize that this is not just a pump problem but also involves patient factors and management factors that we need to learn more about. We are quite ignorant of the patient factors and understanding their contributions to bleeding and thrombosis,” said Dr. Kirklin. He also acknowledged that whatever role the current generation of LVAD pumps play in causing thrombosis will not quickly resolve.

“I’m looking forward to a new generation of pumps, but the pumps we have today will probably remain for another 3-5 years.”

The issue of LVAD pump thrombosis first came into clear focus with publication at the start of 2014 of a report that tracked its incidence from 2004 to mid-2013 at three U.S. centers that had placed a total of 895 LVADs in 837 patients. The annual rate of new episodes of pump thrombosis jumped from about 1%-2% of LVAD recipients throughout the first part of the study period through the end of 2011, to an annual rate of about 10% by mid 2013 (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:33-40).

“The inflection occurred in about 2012,” noted Dr. Nicholas G. Smedira, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic. “No one has figured out why” the incidence suddenly spiked starting in 2012 and intensified in 2013, he said. This epidemic of pump thrombosis has produced “devastating complications” that have led to multiple readmissions and reduced cost-effectiveness of LVADs and has affected how the heart transplant community allocates hearts, Dr. Smedira said during his talk at the session. He noted that once the surge in pump thrombosis started, the timing of the appearance of significant thrombus shifted earlier, often occurring within 2-3 months after LVAD placement. There now is “increasing device-related pessimism” and increasing demoralization among clinicians because of this recurring complication, he said.

More recent data show the trend toward increasingly higher rates of pump thrombosis continuing through the end of 2013, with the situation during 2014 a bit less clear. Late last year, data from 9,808 U.S. patients who received an LVAD and entered the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) showed that the incidence of pump thrombosis during the first 6 months following an implant rose from 1% in 2008 to 2% in 2009 and in 2010, 4% in 2011, 7% in 2012, 8% in 2013, and then eased back to 5% in the first half of 2014 (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015 Dec;34[12]:1515-26). The annual rate rose from 2% in 2008 to a peak of 11% in 2013, with 12-month data from 2014 not yet available at the time of this report.

“The modest reduction of observed pump thrombosis at 6 months during 2014 has occurred in a milieu of heightened intensity of anti-coagulation management, greater surgical awareness of optimal pump implantation and positioning and pump speed management. Thus, one may speculate that current thrombosis risk-mitigation strategies have contributed to reducing but not eliminating the increased thrombosis risk observed since 2011,” concluded the authors of the report.

Surgeons and cardiologists must now have a high index of suspicion for pump thrombosis in LVAD recipients, and be especially on the lookout for four key flags of a problem, said Dr. Kormos. The first is a rising LDH level, but additional flags include an isolated power elevation that doesn’t correlate with anything else, evidence of hemolysis, and new-onset heart failure symptoms. These can occur individually or in some combination. He recommended following a diagnostic algorithm first presented in 2013 that remains very valid today (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013 July;32[7]:667-70).

Dr. Kormos also highlighted that the presentation of pump thrombosis can differ between the two LVADs most commonly used in U.S. practice, the HeartMate II and the HeartWare devices. A LDH elevation is primarily an indicator for HeartMate II, while both that model and the HeartWare device show sustained, isolated power elevations when thrombosis occurs.

Dr. Pagani, Dr. Kirklin, and Dr. Smedira had no disclosures. Dr. Kormos has received travel support from HeartWare. Dr. Kilic has been a consultant to Thoratec and a speaker on behalf of Baxter International.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – Cardiothoracic surgeons who implant left ventricular assist devices in patients with failing hearts remain at a loss to fully explain why they started seeing a sharp increase in thrombus clogging in these devices in 2012, but nevertheless they are gaining a better sense of how to minimize the risk.

Three key principles for minimizing thrombosis risk are selecting the right patients to receive left ventricular assist devices (LVAD), applying optimal management strategies once patients receive a LVAD, and maintaining adequate flow of blood through the pump, Dr. Francis D. Pagani said in a talk at a session devoted to pump thrombosis at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Other critical aspects include optimal implantation technique, quick work-up of patients to rule out reversible LVAD inflow or outflow problems once pump thrombosis is suspected, and ceasing medical therapy of the thrombosis if it proves ineffective and instead progress to surgical pump exchange, pump explantation, or heart transplant when necessary, said Dr. Ahmet Kilic, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Ohio State University, Columbus.

Another key issue is that, now that the pump thrombosis incidence is averaging about 10% of LVAD recipients, with an incidence rate during 2-year follow-up as high as 24% reported from one series, surgeons and physicians who care for LVAD patients must have a high index of suspicion and routinely screen LVAD recipients for early signs of pump thrombosis. The best way to catch pump thrombosis early seems to be by regularly measuring patients’ serum level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), said Dr. Robert L. Kormos, professor of surgery and director of the artificial heart program at the University of Pittsburgh.

“We measure LDH on most clinic visits, whether or not the patient has an indication of pump thrombosis. We need to screen [LDH levels] much more routinely than we used to,” he said during the session. “Elevated LDH is probably the first and most reliable early sign, but you need to also assess LDH isoenzymes because we’ve had patients with an elevation but no sign of pump thrombosis, and their isoenzymes showed that the increased LDH was coming from their liver,” Dr. Kormos said in an interview.

Although serial measurements and isoenzyme analysis can establish a sharp rise in heart-specific LDH in an individual patient, a report at the meeting documented that in a series of 53 patients with pump thrombosis treated at either of two U.S. centers, an LDH level of at least 1,155 IU/L flagged pump thrombosis with a fairly high sensitivity and specificity. This LDH level is roughly five times the upper limit of normal, noted Dr. Pagani, professor of surgery and surgical director of adult heart transplantation at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a senior author on this report.

But prior to this report Dr. Kormos said that he regarded a LDH level of 600-800 IU/L as enough of an elevation above normal to prompt concern and investigation. And he criticized some LVAD programs that allow LDH levels to rise much higher.

“I know of clinicians who see a LDH of 1,500-2,000 IU/L but the patient seems okay and they wonder if they should change out the pump. For me, it’s a no brainer. Others try to list a patient like this for a heart transplant so they can avoid doing a pump exchange. I think that’s dangerous; it risks liver failure or renal failure. I would not sit on any LVAD that is starting to produce signs of hemolysis syndrome, but some places do this,” Dr. Kormos said in an interview.

“Pump thrombosis probably did not get addressed in as timely a fashion as it should have been” when it was first seen on the rise in 2012, noted Dr. James K. Kirklin, professor of surgery and director of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. “It is now being addressed, and we realize that this is not just a pump problem but also involves patient factors and management factors that we need to learn more about. We are quite ignorant of the patient factors and understanding their contributions to bleeding and thrombosis,” said Dr. Kirklin. He also acknowledged that whatever role the current generation of LVAD pumps play in causing thrombosis will not quickly resolve.

“I’m looking forward to a new generation of pumps, but the pumps we have today will probably remain for another 3-5 years.”

The issue of LVAD pump thrombosis first came into clear focus with publication at the start of 2014 of a report that tracked its incidence from 2004 to mid-2013 at three U.S. centers that had placed a total of 895 LVADs in 837 patients. The annual rate of new episodes of pump thrombosis jumped from about 1%-2% of LVAD recipients throughout the first part of the study period through the end of 2011, to an annual rate of about 10% by mid 2013 (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:33-40).

“The inflection occurred in about 2012,” noted Dr. Nicholas G. Smedira, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic. “No one has figured out why” the incidence suddenly spiked starting in 2012 and intensified in 2013, he said. This epidemic of pump thrombosis has produced “devastating complications” that have led to multiple readmissions and reduced cost-effectiveness of LVADs and has affected how the heart transplant community allocates hearts, Dr. Smedira said during his talk at the session. He noted that once the surge in pump thrombosis started, the timing of the appearance of significant thrombus shifted earlier, often occurring within 2-3 months after LVAD placement. There now is “increasing device-related pessimism” and increasing demoralization among clinicians because of this recurring complication, he said.

More recent data show the trend toward increasingly higher rates of pump thrombosis continuing through the end of 2013, with the situation during 2014 a bit less clear. Late last year, data from 9,808 U.S. patients who received an LVAD and entered the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) showed that the incidence of pump thrombosis during the first 6 months following an implant rose from 1% in 2008 to 2% in 2009 and in 2010, 4% in 2011, 7% in 2012, 8% in 2013, and then eased back to 5% in the first half of 2014 (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015 Dec;34[12]:1515-26). The annual rate rose from 2% in 2008 to a peak of 11% in 2013, with 12-month data from 2014 not yet available at the time of this report.

“The modest reduction of observed pump thrombosis at 6 months during 2014 has occurred in a milieu of heightened intensity of anti-coagulation management, greater surgical awareness of optimal pump implantation and positioning and pump speed management. Thus, one may speculate that current thrombosis risk-mitigation strategies have contributed to reducing but not eliminating the increased thrombosis risk observed since 2011,” concluded the authors of the report.

Surgeons and cardiologists must now have a high index of suspicion for pump thrombosis in LVAD recipients, and be especially on the lookout for four key flags of a problem, said Dr. Kormos. The first is a rising LDH level, but additional flags include an isolated power elevation that doesn’t correlate with anything else, evidence of hemolysis, and new-onset heart failure symptoms. These can occur individually or in some combination. He recommended following a diagnostic algorithm first presented in 2013 that remains very valid today (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013 July;32[7]:667-70).

Dr. Kormos also highlighted that the presentation of pump thrombosis can differ between the two LVADs most commonly used in U.S. practice, the HeartMate II and the HeartWare devices. A LDH elevation is primarily an indicator for HeartMate II, while both that model and the HeartWare device show sustained, isolated power elevations when thrombosis occurs.

Dr. Pagani, Dr. Kirklin, and Dr. Smedira had no disclosures. Dr. Kormos has received travel support from HeartWare. Dr. Kilic has been a consultant to Thoratec and a speaker on behalf of Baxter International.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

Exciting Program Set for AATS Week 2016, Register Today!

Be a part of an extraordinary week of science, sharing the latest advances in cardiothoracic surgery with colleagues from around the world -- AATS Week 2016. The week starts off with the two-day Aortic Symposium (May 12–13/New York City) followed by the 96th AATS Annual Meeting (May 14-18/Baltimore, MD). Register now!

Be a part of an extraordinary week of science, sharing the latest advances in cardiothoracic surgery with colleagues from around the world -- AATS Week 2016. The week starts off with the two-day Aortic Symposium (May 12–13/New York City) followed by the 96th AATS Annual Meeting (May 14-18/Baltimore, MD). Register now!

Be a part of an extraordinary week of science, sharing the latest advances in cardiothoracic surgery with colleagues from around the world -- AATS Week 2016. The week starts off with the two-day Aortic Symposium (May 12–13/New York City) followed by the 96th AATS Annual Meeting (May 14-18/Baltimore, MD). Register now!

End of life care

As the busy days of a long, gray winter drag on and an early season of Lent has begun, this column flows from reflections on life, death, and the promise of a new season of spring and green trees, hopefully coming soon – no matter what that groundhog saw.

Clinical ethics consultation often involves end of life (EOL) care. When I recall patients from my career, many memories are of patients who died. I trained with an intensivist who said he felt he was under less stress than the general pediatricians. While his patients were sicker, if one of his patients died, it was not unexpected. The presumption was that in the ICU everything possible had been done. General pediatricians rarely have a patient who dies. When they do, everyone, including the pediatrician, will ponder over whether something might have been caught earlier or something could have been done differently. But the most difficult problems in pediatric EOL care involve deciding when to stop aggressive care and let nature take its course.

I think the natural tendency for scholars is to approach difficult decisions by seeking more information. The delusion (which scholars can usually elucidate in great postmodern detail as long as it doesn’t apply to our own behavior) is that extensive information and deep reflection will lead to the best, most accurate, immutable, and nonambivalent declaration of goals, desires, values, and intents. To even make this delusion plausible, a sci-fi writer had to create a nonhuman species of Vulcans. But medical ethicists routinely apply this paradigm to existentially frightening EOL matters in a medical world full of prognostic uncertainty. Ethicists have recommended that this method of decision making be adopted by a population with low health literacy and a predilection to using Tinder.

For the internists, EOL care is mostly about specifying which modalities to use and which to limit. Over time, it became evident that a single check box, labeled Do Not Resuscitate yes/no, was insufficient to capture patient preferences. I recall once seeing a draft document with 49 boxes. It was clearly unwieldy. Most states that have adopted a POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) paradigm have settled for forms with five to seven options. I think that if it were possible to capture advance directives better than that, eharmony.com, with its plethora of questions, would have already created an app for it. In adult medicine, we always can lament that the conversation about EOL care was too brief, but in my experience raising expectations of a more comprehensive discussion usually lowers the likelihood of people ever undertaking even an abbreviated conversation. In ethics, if you raise the bar high enough, people seem to walk under it.

Pediatrics at the EOL tends to focus discussion more on the goals of care, the likely outcomes, and the quality of life. These perspectives are then sometimes mapped, with poor reliability, onto the POLST paradigm designed for adults. Parents are usually at the bedside often enough to recognize their child’s suffering during aggressive care. Surrogate decision makers for adult EOL care occasionally lack that insight.

While advance directive documents are helpful, I don’t think there is a substitute for a physician motivated by empathy and a caring, involved surrogate decision maker at bedside. Providing information is not the key focus. The process should emphasize building trusting relationships, clear understanding, and reasonable expectations. I am reminded in those situations of an ancient quote: Medical care is “to cure sometimes, to relieve often, and to comfort always.”

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Dr. Powell said he had no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest. E-mail him at [email protected].

As the busy days of a long, gray winter drag on and an early season of Lent has begun, this column flows from reflections on life, death, and the promise of a new season of spring and green trees, hopefully coming soon – no matter what that groundhog saw.

Clinical ethics consultation often involves end of life (EOL) care. When I recall patients from my career, many memories are of patients who died. I trained with an intensivist who said he felt he was under less stress than the general pediatricians. While his patients were sicker, if one of his patients died, it was not unexpected. The presumption was that in the ICU everything possible had been done. General pediatricians rarely have a patient who dies. When they do, everyone, including the pediatrician, will ponder over whether something might have been caught earlier or something could have been done differently. But the most difficult problems in pediatric EOL care involve deciding when to stop aggressive care and let nature take its course.

I think the natural tendency for scholars is to approach difficult decisions by seeking more information. The delusion (which scholars can usually elucidate in great postmodern detail as long as it doesn’t apply to our own behavior) is that extensive information and deep reflection will lead to the best, most accurate, immutable, and nonambivalent declaration of goals, desires, values, and intents. To even make this delusion plausible, a sci-fi writer had to create a nonhuman species of Vulcans. But medical ethicists routinely apply this paradigm to existentially frightening EOL matters in a medical world full of prognostic uncertainty. Ethicists have recommended that this method of decision making be adopted by a population with low health literacy and a predilection to using Tinder.

For the internists, EOL care is mostly about specifying which modalities to use and which to limit. Over time, it became evident that a single check box, labeled Do Not Resuscitate yes/no, was insufficient to capture patient preferences. I recall once seeing a draft document with 49 boxes. It was clearly unwieldy. Most states that have adopted a POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) paradigm have settled for forms with five to seven options. I think that if it were possible to capture advance directives better than that, eharmony.com, with its plethora of questions, would have already created an app for it. In adult medicine, we always can lament that the conversation about EOL care was too brief, but in my experience raising expectations of a more comprehensive discussion usually lowers the likelihood of people ever undertaking even an abbreviated conversation. In ethics, if you raise the bar high enough, people seem to walk under it.

Pediatrics at the EOL tends to focus discussion more on the goals of care, the likely outcomes, and the quality of life. These perspectives are then sometimes mapped, with poor reliability, onto the POLST paradigm designed for adults. Parents are usually at the bedside often enough to recognize their child’s suffering during aggressive care. Surrogate decision makers for adult EOL care occasionally lack that insight.

While advance directive documents are helpful, I don’t think there is a substitute for a physician motivated by empathy and a caring, involved surrogate decision maker at bedside. Providing information is not the key focus. The process should emphasize building trusting relationships, clear understanding, and reasonable expectations. I am reminded in those situations of an ancient quote: Medical care is “to cure sometimes, to relieve often, and to comfort always.”

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Dr. Powell said he had no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest. E-mail him at [email protected].

As the busy days of a long, gray winter drag on and an early season of Lent has begun, this column flows from reflections on life, death, and the promise of a new season of spring and green trees, hopefully coming soon – no matter what that groundhog saw.

Clinical ethics consultation often involves end of life (EOL) care. When I recall patients from my career, many memories are of patients who died. I trained with an intensivist who said he felt he was under less stress than the general pediatricians. While his patients were sicker, if one of his patients died, it was not unexpected. The presumption was that in the ICU everything possible had been done. General pediatricians rarely have a patient who dies. When they do, everyone, including the pediatrician, will ponder over whether something might have been caught earlier or something could have been done differently. But the most difficult problems in pediatric EOL care involve deciding when to stop aggressive care and let nature take its course.

I think the natural tendency for scholars is to approach difficult decisions by seeking more information. The delusion (which scholars can usually elucidate in great postmodern detail as long as it doesn’t apply to our own behavior) is that extensive information and deep reflection will lead to the best, most accurate, immutable, and nonambivalent declaration of goals, desires, values, and intents. To even make this delusion plausible, a sci-fi writer had to create a nonhuman species of Vulcans. But medical ethicists routinely apply this paradigm to existentially frightening EOL matters in a medical world full of prognostic uncertainty. Ethicists have recommended that this method of decision making be adopted by a population with low health literacy and a predilection to using Tinder.

For the internists, EOL care is mostly about specifying which modalities to use and which to limit. Over time, it became evident that a single check box, labeled Do Not Resuscitate yes/no, was insufficient to capture patient preferences. I recall once seeing a draft document with 49 boxes. It was clearly unwieldy. Most states that have adopted a POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) paradigm have settled for forms with five to seven options. I think that if it were possible to capture advance directives better than that, eharmony.com, with its plethora of questions, would have already created an app for it. In adult medicine, we always can lament that the conversation about EOL care was too brief, but in my experience raising expectations of a more comprehensive discussion usually lowers the likelihood of people ever undertaking even an abbreviated conversation. In ethics, if you raise the bar high enough, people seem to walk under it.

Pediatrics at the EOL tends to focus discussion more on the goals of care, the likely outcomes, and the quality of life. These perspectives are then sometimes mapped, with poor reliability, onto the POLST paradigm designed for adults. Parents are usually at the bedside often enough to recognize their child’s suffering during aggressive care. Surrogate decision makers for adult EOL care occasionally lack that insight.

While advance directive documents are helpful, I don’t think there is a substitute for a physician motivated by empathy and a caring, involved surrogate decision maker at bedside. Providing information is not the key focus. The process should emphasize building trusting relationships, clear understanding, and reasonable expectations. I am reminded in those situations of an ancient quote: Medical care is “to cure sometimes, to relieve often, and to comfort always.”

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Dr. Powell said he had no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest. E-mail him at [email protected].

Cryo-Compression Therapy

CoolSystems, Inc. (www.gameready.com)

The Game Ready Injury Treatment System

Peter Millett, MD, The Steadman Clinic, Vail, CO; Consultant, Major League Baseball Players’ Association

At the Steadman Clinic, we have developed best-practice techniques and protocols to accelerate our patients’ recoveries. Game Ready helps my patients recover faster. The Game Ready device has the most advanced level of rehab technology with the cost-effective cryotherapy delivery system, intermittent compression, and ergonomically designed wraps tailored for specific areas of the body. It just works better than ice alone or other cryotherapy devices. Game Ready reduces swelling and gets patients back faster.

I prescribe Game Ready after surgical procedures because it decreases pain, reduces the need for pain medication, and results in a faster recovery. For my overhead athletes, I routinely use the shoulder and elbow wraps for labral tears, shoulder instability, biceps tendon disorders, and rotator cuff problems.

J.W. Thomas Byrd, MD, Nashville Sports Medicine and Orthopaedics, Orthopaedic Surgical Consultant, various Major League Baseball Clubs

Performing hip arthroscopy procedures for Major League Baseball pitchers over the last 3 decades, I have come to realize the importance of choosing the most effective recovery therapy device. We have trialed numerous products and found the Game Ready cold-intermittent-compression device to be an incredible asset in the recovery and pain management strategy.

During the rehab process, pain control is essential to the athlete’s ability to participate and achieve optimal recovery. Hip procedures can be painful because they usually revolve around restoring the acetabular labrum, which is richly innervated with nociceptive fibers. In order to control discomfort following surgery, regional anesthetic nerve blocks are sometimes necessary. However, these blocks can hinder an athlete’s ability to participate in, and benefit from, the early postoperative rehabilitation process. Applying the Game Ready led to a noticeable drop in postoperative pain, obviating the need for a block.

Kenneth Akizuki, MD, SOAR, San Francisco, CA, Team Physician, San Francisco Giants

Among pro players, Tommy John surgery is a common procedure. The day after surgery, we start the player on the Game Ready system to relieve pain and quickly control swelling. We typically start with cold therapy, then add compression about a week in, and use it throughout recovery.

The players love the comfort of the ergonomic wrap designs and I really like the flexed elbow wrap. The cold is adjustable so we don’t get overcooling, and the wrap design keeps the surgery site dry, which cuts the risk of infection. The pre-set treatment programs are another big advantage. They take the hassle out of application. Whether a professional athlete or not, all our patients want convenience, and we want to see progress. Progress is motivating, it encourages compliance—and that improves outcomes.

CoolSystems, Inc. (www.gameready.com)

The Game Ready Injury Treatment System

Peter Millett, MD, The Steadman Clinic, Vail, CO; Consultant, Major League Baseball Players’ Association

At the Steadman Clinic, we have developed best-practice techniques and protocols to accelerate our patients’ recoveries. Game Ready helps my patients recover faster. The Game Ready device has the most advanced level of rehab technology with the cost-effective cryotherapy delivery system, intermittent compression, and ergonomically designed wraps tailored for specific areas of the body. It just works better than ice alone or other cryotherapy devices. Game Ready reduces swelling and gets patients back faster.

I prescribe Game Ready after surgical procedures because it decreases pain, reduces the need for pain medication, and results in a faster recovery. For my overhead athletes, I routinely use the shoulder and elbow wraps for labral tears, shoulder instability, biceps tendon disorders, and rotator cuff problems.

J.W. Thomas Byrd, MD, Nashville Sports Medicine and Orthopaedics, Orthopaedic Surgical Consultant, various Major League Baseball Clubs

Performing hip arthroscopy procedures for Major League Baseball pitchers over the last 3 decades, I have come to realize the importance of choosing the most effective recovery therapy device. We have trialed numerous products and found the Game Ready cold-intermittent-compression device to be an incredible asset in the recovery and pain management strategy.

During the rehab process, pain control is essential to the athlete’s ability to participate and achieve optimal recovery. Hip procedures can be painful because they usually revolve around restoring the acetabular labrum, which is richly innervated with nociceptive fibers. In order to control discomfort following surgery, regional anesthetic nerve blocks are sometimes necessary. However, these blocks can hinder an athlete’s ability to participate in, and benefit from, the early postoperative rehabilitation process. Applying the Game Ready led to a noticeable drop in postoperative pain, obviating the need for a block.

Kenneth Akizuki, MD, SOAR, San Francisco, CA, Team Physician, San Francisco Giants

Among pro players, Tommy John surgery is a common procedure. The day after surgery, we start the player on the Game Ready system to relieve pain and quickly control swelling. We typically start with cold therapy, then add compression about a week in, and use it throughout recovery.

The players love the comfort of the ergonomic wrap designs and I really like the flexed elbow wrap. The cold is adjustable so we don’t get overcooling, and the wrap design keeps the surgery site dry, which cuts the risk of infection. The pre-set treatment programs are another big advantage. They take the hassle out of application. Whether a professional athlete or not, all our patients want convenience, and we want to see progress. Progress is motivating, it encourages compliance—and that improves outcomes.

CoolSystems, Inc. (www.gameready.com)

The Game Ready Injury Treatment System

Peter Millett, MD, The Steadman Clinic, Vail, CO; Consultant, Major League Baseball Players’ Association

At the Steadman Clinic, we have developed best-practice techniques and protocols to accelerate our patients’ recoveries. Game Ready helps my patients recover faster. The Game Ready device has the most advanced level of rehab technology with the cost-effective cryotherapy delivery system, intermittent compression, and ergonomically designed wraps tailored for specific areas of the body. It just works better than ice alone or other cryotherapy devices. Game Ready reduces swelling and gets patients back faster.

I prescribe Game Ready after surgical procedures because it decreases pain, reduces the need for pain medication, and results in a faster recovery. For my overhead athletes, I routinely use the shoulder and elbow wraps for labral tears, shoulder instability, biceps tendon disorders, and rotator cuff problems.

J.W. Thomas Byrd, MD, Nashville Sports Medicine and Orthopaedics, Orthopaedic Surgical Consultant, various Major League Baseball Clubs

Performing hip arthroscopy procedures for Major League Baseball pitchers over the last 3 decades, I have come to realize the importance of choosing the most effective recovery therapy device. We have trialed numerous products and found the Game Ready cold-intermittent-compression device to be an incredible asset in the recovery and pain management strategy.

During the rehab process, pain control is essential to the athlete’s ability to participate and achieve optimal recovery. Hip procedures can be painful because they usually revolve around restoring the acetabular labrum, which is richly innervated with nociceptive fibers. In order to control discomfort following surgery, regional anesthetic nerve blocks are sometimes necessary. However, these blocks can hinder an athlete’s ability to participate in, and benefit from, the early postoperative rehabilitation process. Applying the Game Ready led to a noticeable drop in postoperative pain, obviating the need for a block.

Kenneth Akizuki, MD, SOAR, San Francisco, CA, Team Physician, San Francisco Giants

Among pro players, Tommy John surgery is a common procedure. The day after surgery, we start the player on the Game Ready system to relieve pain and quickly control swelling. We typically start with cold therapy, then add compression about a week in, and use it throughout recovery.

The players love the comfort of the ergonomic wrap designs and I really like the flexed elbow wrap. The cold is adjustable so we don’t get overcooling, and the wrap design keeps the surgery site dry, which cuts the risk of infection. The pre-set treatment programs are another big advantage. They take the hassle out of application. Whether a professional athlete or not, all our patients want convenience, and we want to see progress. Progress is motivating, it encourages compliance—and that improves outcomes.

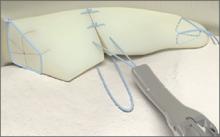

All-Inside Meniscal Repair Devices

Tools of the Trade features reviews of the hottest new products, with surgical pearls written by surgeons who know these products best.

Arthrex, Inc. (http://www.arthrex.com)

Knee Scorpion

The Arthrex Knee Scorpion allows for simple passage of suture at the root to repair the tissue. The mechanism of the Knee Scorpion self-retrieving the suture after passage eliminates the need for another step in the procedure, which saves time. There are various types of suture configurations that can be incorporated into meniscus repairs with the Knee Scorpion. Depending on tissue quality and location, I will either pass the center of the suture to create a cinch or luggage tag type of stitch, or sometimes a simple stitch.

A challenging meniscal tear pattern that repair is particularly made easier by use of the Knee Scorpion is the radial tear of the lateral meniscus. Here it is easy to place a side-to-side “spanning” circumferential suture pattern, which is the strongest suture configuration, and it reduces the tissue very well. This approach also is ideal for variant root type tears, those that are 3 to 4 mm from the root commonly seen with the lateral meniscus associated with anterior cruciate ligament tears.

Benefits: The Knee Scorpion has a very low profile to facilitate placement in the joint with a 5º upcurve to avoid injury to the femoral condyle. The needle captures the suture after passage, which saves time and an additional surgical step. It can be used with both 0 FiberWire and 2-0 FiberWire.

Surgical pearl: Using a cannula through the working portal prevents any tissue bridge when passing and tying sutures. I prefer a Passport button cannula since its flexibility allows more access in different planes compared to a rigid type cannula.

Patrick A. Smith, MD, Columbia Orthopaedic Group, Head Section of Sports Medicine University of Missouri, Head Team Physician University of Missouri

Arthrex, Inc. (http://www.arthrex.com)

SpeedCinch

The SpeedCinch’s pistol grip design permits ergonomic, one-handed all-inside meniscal repair. It is best suited for meniscal tears of the posterior horn and body. The posterior horn of the meniscus can be repaired with the SpeedCinch inserted through either the ipsilateral or contralateral portal. Meniscal body tears, however, are best approached via a contralateral portal. The end of the device contains a 15g needle that should be advanced across the meniscus. After passage of the needle, the first implant is pushed through the needle when the trigger is fully deployed.

Next, the SpeedCinch needle should be moved at least 1 cm for placement of the second implant in either a horizontal or vertical mattress fashion. After the needle is brought to the second insertion site, the implant selector button is moved to 2 and the trigger is depressed until the first click is felt and heard. Next, the trigger is held in place after the first click and the needle is advanced across the meniscus before fully depressing the trigger, which will advance the second implant. The device is then removed and the pre-tied knot is secured with a knot pusher and then cut.

Vic Goradia, MD, G2 Orthopedics and Sports Medicine, Glen Allen, VA

Cayenne Medical, Inc. (www.cayennemedical.com)

The CrossFix II System

The CrossFix II System offers a unique, all-arthroscopic, suture-only meniscal repair that reduces the risk of chondral injury. Its “all-inside” technique uses 2 parallel suture delivery needles, available in both curved and straight designs, inserted through a single incision to provide an all-inside meniscus repair. This simple procedure can be performed in minutes via the device’s pre-tied, sliding knot, creating a “suture only” mattress stitch that replicates the repair of standard open suturing techniques. The speed and reproducibility of the repair dramatically improves operating room efficiency. Even complex tears requiring multiple sutures can be repaired in minutes.

Benefits: All-suture, no implants; single insertion; pre-tied, sliding knot. Parallel needles may be difficult to use in very tight knees.

Surgical pearl: Avoid torqueing the needles upon insertion into the meniscus.

Kenneth Montgomery, MD, Tri-County Orthopedics, Cedar Knolls, NJ.

Ceterix Orthopaedics, Inc. (www.ceterix.com)

NovoStitch Plus

The Ceterix NovoStitch Plus enables surgeons to place circumferential compression stitches around meniscus tears. These stitch patterns are designed to provide anatomical reduction and uniform compression of the tear edges, and repair the femoral surface (top) and tibial surface (bottom) of the tear with each stitch. It is also designed to eliminate neurovascular risk and avoid excessive entrapment or extrusion of the meniscus to capsule. The NovoStitch Plus passes circumferential stitches via an all-inside arthroscopic technique. In addition to anatomically repairing vertical tears, circumferential stitches also enable repair of tear types that were previously considered difficult to adequately sew.

Benefits: Passes both sides of the stitch with 1 insertion (avoids tissue bridges and girth hitches). Retractable lower jaw (allows access to tight knees, and allows removal from knees with mobile menisci). Needle extends into the posterior gutter through the tip of the lower jaw (does not touch chondral surfaces). Smaller lower jaw tooth (easier insertion of the lower jaw under the meniscus). Upper jaw curved to follow the shape contour of the femoral side of the meniscus and femoral condyle. Compared to hybrid all-inside devices, inside-out and outside-in repairs. Enables anatomical reduction and uniform compression. Each stitch repairs the top and bottom of the tear. Designed to eliminate neurovascular risk. Avoids excessive capsular entrapment. Repairs effectively in front of the popliteal hiatus. Enables side-to-side radial tear repair, and top-to-bottom horizontal tear repair. Significantly smaller needle than used by hybrid all-inside devices.

Surgical pearl: A spinal needle should be used to establish the skin incision location of the working portal. The optimal skin incision location is one where a spinal needle can be inserted such that the distal end of the needle is parallel to the region of the tibial plateau under the meniscus.

Justin Saliman, MD, Cedars-Sinai Orthopaedic Center, Los Angeles CA

Mitek Sports Medicine (www.depuysynthes.com)

Mitek Omnispan

The Mitek Omnispan Meniscal Repair System is an all-inside arthroscopic meniscal repair device. It consists of a low profile needle, pre-loaded with 2 PEEK backstops and No. 2/0 Orthocord High Strength Orthopaedic Suture, which is delivered using the Omnispan System Applier. The needles come in 3 angles (0°, 12°, and 27°) and the Applier is a single-patient, multi-use design, meaning the same Applier can be used for multiple implants with a single patient. The needles also have a safety sleeve over each set of implants to prevent delivery failure. Once the needle is attached to the Applier, the device is inserted into the knee. Using the gray trigger, the first implant is delivered into the meniscocapsular region. The red trigger is then pulled, advancing the second implant. Once appropriate positioning of the second implant is determined, the gray trigger is fired again. The surgeon pulls on the sliding knot advancing the suture through the implants creating a suture bridge over the tear. The final repair consists of Orthocord Suture spanning the meniscus, while the PEEK backstops are embedded in the meniscocapsular area only.

Surgical pearls:

An adequate portal opening is paramount for successful implementation. I widen my portal with an instrument clamp to allow easy passage of the Applier. It is usually necessary to switch the camera back and forth between both portals to gain access to the angles needed to create the repair. I also always use a skid when inserting the Applier to prevent soft tissue impingement.

The surgeon should always check to make sure the implant is properly loaded on the back table, ensuring it is fully inserted into the locking mechanism and loaded in the correct direction.

The surgeon should hold the Applier firmly when firing the gray trigger, as some kick-back does occur.

The Applier should remain in the joint throughout the advancing and deployment of implants, so the surgeon can maintain visualization with the scope. Once the implants are in position, I then remove the Applier from the joint space.