User login

Elevated cardiovascular risks linked to hidradenitis suppurativa

The inflammatory skin disease hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with significantly increased risks of adverse cardiovascular outcomes such as ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular mortality, according to results of a population-based study.

A population-based cohort study of 5,964 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa showed that, after adjusting for confounders such as age, sex, smoking, and other comorbidities, hidradenitis suppurativa was associated with a 57% greater risk of myocardial infarction, 33% greater risk of ischemic stroke, 53% increase in major adverse cardiovascular events, and 35% increase in all-cause mortality over a mean 7.1 years of follow-up.

The study, published online Feb. 17 in JAMA Dermatology, also showed a significant increase in cardiovascular-associated death, which was the only adverse outcome that remained significantly elevated (incidence rate ratio, 1.58) in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa when compared with a control group of individuals with severe psoriasis (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Feb 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6264).

“Studies have suggested that, in hidradenitis suppurativa, atrophy of the sebaceous glands, follicular hyperkeratinization, and subsequent hair follicle destruction are associated with deep-seated inflammation, increased susceptibility to secondary infections, and chronic perpetuation of the inflammatory response,” wrote Dr. Alexander Egeberg of the University of Copenhagen and coauthors.

The researchers suggested that there was a “conspicuous absence” of research reports on the risk of cardiovascular disease in hidradenitis suppurativa, especially in light of accumulating evidence of the association between cardiovascular disease and other chronic inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

The inflammatory skin disease hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with significantly increased risks of adverse cardiovascular outcomes such as ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular mortality, according to results of a population-based study.

A population-based cohort study of 5,964 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa showed that, after adjusting for confounders such as age, sex, smoking, and other comorbidities, hidradenitis suppurativa was associated with a 57% greater risk of myocardial infarction, 33% greater risk of ischemic stroke, 53% increase in major adverse cardiovascular events, and 35% increase in all-cause mortality over a mean 7.1 years of follow-up.

The study, published online Feb. 17 in JAMA Dermatology, also showed a significant increase in cardiovascular-associated death, which was the only adverse outcome that remained significantly elevated (incidence rate ratio, 1.58) in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa when compared with a control group of individuals with severe psoriasis (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Feb 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6264).

“Studies have suggested that, in hidradenitis suppurativa, atrophy of the sebaceous glands, follicular hyperkeratinization, and subsequent hair follicle destruction are associated with deep-seated inflammation, increased susceptibility to secondary infections, and chronic perpetuation of the inflammatory response,” wrote Dr. Alexander Egeberg of the University of Copenhagen and coauthors.

The researchers suggested that there was a “conspicuous absence” of research reports on the risk of cardiovascular disease in hidradenitis suppurativa, especially in light of accumulating evidence of the association between cardiovascular disease and other chronic inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

The inflammatory skin disease hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with significantly increased risks of adverse cardiovascular outcomes such as ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular mortality, according to results of a population-based study.

A population-based cohort study of 5,964 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa showed that, after adjusting for confounders such as age, sex, smoking, and other comorbidities, hidradenitis suppurativa was associated with a 57% greater risk of myocardial infarction, 33% greater risk of ischemic stroke, 53% increase in major adverse cardiovascular events, and 35% increase in all-cause mortality over a mean 7.1 years of follow-up.

The study, published online Feb. 17 in JAMA Dermatology, also showed a significant increase in cardiovascular-associated death, which was the only adverse outcome that remained significantly elevated (incidence rate ratio, 1.58) in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa when compared with a control group of individuals with severe psoriasis (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Feb 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6264).

“Studies have suggested that, in hidradenitis suppurativa, atrophy of the sebaceous glands, follicular hyperkeratinization, and subsequent hair follicle destruction are associated with deep-seated inflammation, increased susceptibility to secondary infections, and chronic perpetuation of the inflammatory response,” wrote Dr. Alexander Egeberg of the University of Copenhagen and coauthors.

The researchers suggested that there was a “conspicuous absence” of research reports on the risk of cardiovascular disease in hidradenitis suppurativa, especially in light of accumulating evidence of the association between cardiovascular disease and other chronic inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with a significantly increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.

Major finding: Individuals with hidradenitis suppurativa had a 57% greater risk of myocardial infarction and 33% greater risk of ischemic stroke, compared with the general population.

Data source: A population-based cohort study in 5,964 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Meniscal Root Tears: Identification and Repair

Intact and well functioning menisci are essential for optimal knee function. Articular cartilage damage and rapid joint degeneration have been observed in knees after meniscectomy.1-5 Meniscal root tears and avulsions are now increasingly recognized as a functional equivalent to total meniscectomy, and will follow a similar course if left untreated.6-8

The menisci provide shock absorption and stability through their unique anatomy and physiology. Their essential role in dissipation of the axial load encountered during daily activities is accomplished via generation of circumferential hoop stress.4,5,9 Tears of the horn or body may diminish this ability depending on the size and location, but a tear or an avulsion that renders the root incompetent will leave the meniscus unable to generate hoop stress.10 Likewise, as the menisci have been shown to be important secondary stabilizers for both translation and rotation, this function is lost or significantly diminished in the setting of a root tear.6,11,12

Despite their clinical and biomechanical implications, meniscal root tears can be difficult to identify, particularly when they are not actively sought. The goal of this article is to highlight the current diagnostic workup and treatment in patients with suspected meniscal root pathology. We will also aim to emphasize important anatomic and biomechanical considerations when attempting a meniscal root repair.

Anatomy

The menisci are 2 fibrocartilage wedge-shaped structures that surround the medial and lateral tibial plateau’s weight-bearing surfaces. They are attached at many points along their periphery via coronary ligaments that comprise a continuous junction of the meniscus to the capsule to the tibial plateau. Each meniscus has an anterior and a posterior horn that are securely anchored to the tibial intercondylar region via strong ligaments known as the roots.

The anterior medial root attaches just anterior and medial to the medial tibial spine. The anterior lateral root attaches just anterior to the lateral tibial spine. The medial and lateral anterior horns of the menisci are also connected via the anterior intermeniscal ligament (AIML).13-15 Recent cadaveric biomechanical studies have questioned the importance of the AIML, demonstrating no significant change in contact pressure or area before and after sectioning.16 Another important consideration with respect to the anterior root insertion of the lateral meniscus is its intimate relationship with the tibial insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). The anterior lateral root and the ACL share over 60% of their tibial footprints.13,17

When the menisci are competent, they absorb between 40% to 70% of the contact force generated between the femur and tibia.1 By providing strong anchor points, the meniscal roots allow the horns and bodies of the menisci to maintain a stable position that maximizes congruency with the femoral condyles.

Pathology

The conversion of axial load to circumferential hoop stresses occur as the resilient, yet pliable, menisci are squeezed between the femoral condyle and tibial plateau. However, this function is dependent on secure attachment sites at the roots. In the setting of root tear, there is no restraint to the peripheral distortion of the menisci, and meniscal extrusion can occur.18

Clinical evidence and biomechanical evidence strongly show the consequences of meniscectomy. Multiple studies have shown similar findings and have proven that a meniscal root tear or avulsion is the biomechanical equivalent to total meniscectomy.3 With meniscectomy, not only do peak pressures within compartments increase significantly, it has been demonstrated that other compartments within the knee with intact menisci do not have increases in compartment pressures, lending more evidence to the menisci functioning as separate units.16 It has also been found that anterior/posterior translation is increased with medial meniscal root tears. When lateral meniscus root tears were studied with associated ACL tear, the pivot shift motion was found to be exaggerated.6

However, the finding of utmost importance in these biomechanical studies is that peak pressures and excessive tibiofemoral motion are restored to normal levels after meniscal root repair. Therefore, repair of meniscal root tears restores native knee biomechanics and will potentially prevent arthritic sequelae from developing.3,4,7,19

Epidemiology

Tears of the posterior root of either menisci are more common than their anterior counterparts, and have been more extensively studied. However, there are situations that can lead to anterior root tears, specifically during ACL reconstruction and during medullary nailing of the tibia.20,21 Barring iatrogenic injury, the anterior horn is less at risk for injury than the posterior horn given the biomechanical environment of the knee.3

Medial meniscus posterior root tears are more common than lateral tears. However, these are often more chronic in nature and not associated with an acute event. Risk factors for medial meniscus root tear include increased body mass index, varus mechanical axis, female gender, and low activity level.22

Lateral meniscus root tears more commonly occur during trauma with sprains and/or tears of knee ligaments.23 Along with increased recognition of meniscal root injuries associated with knee ligamentous injury comes the recognition that certain ligamentous reconstructions—namely the ACL—are more prone to failure and have higher stresses when a root tear is left untreated.17,24

Diagnosis

The gold standard for diagnosis of a meniscal root lesion is under direct visualization during arthroscopy.18 The meniscal roots must be probed and stressed to assess their integrity regardless of the initial indication for knee arthroscopy. In most cases, however, the diagnosis of meniscal root tears should occur prior to proceeding to the operating room.

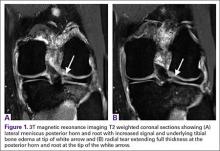

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used to aid in diagnosis of meniscal root tears since the early 1990s.25 Now, with the widespread use of MRI, understanding and diagnosis of meniscal root pathology has increased. All sequences should be reviewed, but T2 weighted coronal sections should provide the best visualization of the posterior roots (Figures 1A, 1B). Sagittal sections may also be helpful in this diagnosis. Increased signal within the root or horn may represent partial or full thickness tears, or may show a more degenerative process with fraying.14,15,26,27

MRI does have limitations, however. When compared to arthroscopy, the sensitivity of 3T MRI to identify posterior root tears is 77%, and specificity is 73%. Medial root tears are more readily identified on MRI than lateral tears.28 This further highlights the need for high suspicion during arthroscopy with the requisite equipment on standby should it be needed.

A concerning finding that may be observed on MRI includes meniscal extrusion (Figures 2A, 2B). Most often seen with the medial meniscus, extrusion is diagnosed when the meniscal body displaces greater than 3 mm past the tibial articular surface on a midcoronal image.26,27 Over 50% of patients with medial meniscal extrusion on MRI will have medial meniscal root tears.26,27 Conversely, meniscal extrusion is less common in lateral menisci for multiple reasons. The lateral compartment of the knee does not have as high contact pressure as the medial compartment, so the lateral meniscus is not as likely to be extruded from the joint. Additionally, the posterior lateral root has the added benefit of further stability from meniscofemoral ligaments.11 They provide a restraint to meniscal extrusion, with a reported rate of 14% lateral meniscus extrusion when they are intact. If the meniscofemoral ligaments are not present or torn in the setting of posterior root tear, the lateral meniscus extrusion rate quadruples and approaches that of medial meniscal extrusion.15

Another finding indicative of meniscal root tear is the “ghost meniscus” (Figure 3). The posterior horn and anterior horn should both be visible in sagittal cuts on MRI. When the anterior horn is present, but the posterior horn is not visualized, it is termed a “ghost meniscus.” This MRI finding is highly associated with meniscal root tears, and will often be found along with meniscal extrusion on coronal sequencing.27,28

Treatment

Historically, large meniscal tears, extruded menisci, or root avulsions have been treated with conservative observation if asymptomatic, or with meniscectomy when symptomatic. With a meniscal root tear, both forms of treatment will not provide lasting benefit and rapid joint degeneration ensues. Evidence now supports repair over meniscectomy when treating root tears.7,8,19,29

Patients who have meniscal root tears that are likely sequelae of an arthritic process are not candidates for meniscal root repair. These patients will often have known arthritis with an intact meniscus and then progress to meniscal pathology, most often medially. Because arthritis is the cause of these meniscal tears, a repair will not reverse this process; such repairs will likely fail, and the patient will re-tear the meniscus. For this subset of patients, physical therapy and activity modification are appropriate treatment.

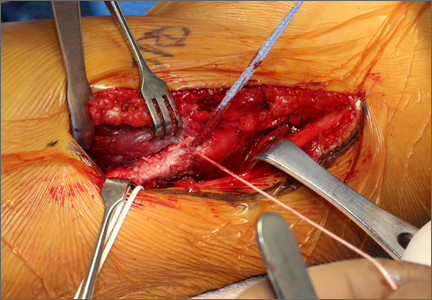

Repair is indicated for patients with acute tears, with or without associated soft tissue injury to the knee, and those with chronic or acute on chronic tears with minimal arthritis within the knee. The authors’ preferred method of repair is via suture fixation through transosseous tunnel (Figures 4A-4F).

Once a root tear has been identified during arthroscopy, it should be probed and/or grasped and pulled to confirm its integrity. A shaver is then used to debride any fraying of the meniscus and to debride the anatomic footprint of the root. Curettes and rasps are used to prepare the meniscal bed at the center of its insertion and the undersurface of the meniscal root. Once the attachment site of the root insertion has been prepared, an ACL tip-to-tip drill guide is placed over the prepared bed. For repair of a medial meniscus posterior root, a 2.4-mm drill tip guide pin is inserted through the guide via an incision made at the anteromedial tibia. For repair of the lateral meniscus posterior root, the pin is inserted through an incision at the anterolateral aspect of the tibia.

Once the guide pin has been inserted and is visualized at the center of the root footprint, it is held in place by a hemostat or grasper placed intra-articularly. Next, the guide pin is overreamed with a 4.5-mm cannulated drill bit. The transosseous tunnel is then further prepared using a shaver to remove excess soft tissue surrounding the tunnel entrance at the tibial plateau. Further rasping around the edges of the tunnel is performed to make final preparations.

Attention is then turned back to the meniscal root. Using a FastPass Scorpion (Arthrex), 2 or 3 size 0 fiber wire sutures are passed through the root, and a cinch stitch is then secured leaving four to six stands (2 from each Scorpion pass) in the root. A FiberStick is then introduced into the tibial bone tunnel and each strand of the 0 fiberwire is retrieved. Once the FiberWire attached to the meniscal root is in the tunnel, the meniscus should be directly visualized as the appropriate tension is toggled to reduce the meniscal root into its footprint. In order to securely fasten the meniscal root, an Arthrex SwiveLock 4.75-mm suture anchor is used. The meniscus is again probed to assess the integrity of the repair. Of note, an alternative method of fixation is accomplished by tying the fiberwire over an Arthrex suture button at the anterior tibia.

Postoperatively, weight bearing restriction is warranted, along with range of motion restrictions. During the first 2 weeks, patients will be counseled to be touch down weight bearing with the use of crutches or a walker. During this period, range of motion will be restricted by hinged knee brace to 30° of flexion and full extension. The next 2-week period will advance to progressive partial weight bearing, again with crutches or a walker. Range of motion will also be expanded to 60° of flexion. After a month, the patient will then be allowed to be full weight bearing as tolerated and be weaned from assistive ambulation devices. Range of motion will then be 90° of flexion. It is paramount that full extension be achieved and maintained in the early postoperative period. Quadriceps strengthening should also proceed with unlimited straight leg raises throughout this period as well.

1. Kidron A, Thein R. Radial tears associated with cleavage tears of the medial meniscus in athletes. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(3):254-256.

2. Fairbank TJ. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30B(4):664-670.

3. Allaire R, Muriuki M, Gilbertson L, Harner CD. Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus: similar to total meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg. 2008;90(9):1922-1931.

4. Marzo JM, Gurske-DePerio J. Effects of medial meniscus posterior horn avulsion and repair on tibiofemoral contact area and peak contact pressure with clinical implications. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(1):124-129.

5. Hein CN, Deperio JG, Ehrensberger MT, Marzo JM. Effects of medial meniscal posterior horn avulsion and repair on meniscal displacement. Knee. 2011;18(3):189-192.

6. Shybut TB, Vega CE, Haddad J, et al. Effect of lateral meniscal root tear on the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):905-911.

7. Vyas D, Harner CD. Meniscus root repair. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2012;20(2):86-94.

8. Koenig JH, Ranawat AS, Umans HR, Difelice GS. Meniscal root tears: diagnosis and treatment. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(9):1025-1032.

9. Fithian DC, Kelly MA, Mow VC. Material properties and structure-function relationships in the menisci. Clin Orthop. 1990;(252):19-31.

10. Weaver JB. Ossification of the internal semilunar cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg. 1935;17(1):195-198.

11. Ahn JH, Lee YS, Chang JY, Chang MJ, Eun SS, Kim SM. Arthroscopic all inside repair of the lateral meniscus root tear. Knee. 2009;16(1):77-80.

12. Bellabarba C, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR Jr. Patterns of meniscal injury in the anterior cruciate–deficient knee: a review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 1997;26(1):18-23.

13. LaPrade CM, Ellman MB, Rasmussen MT, et al. Anatomy of the anterior root attachments of the medial and lateral menisci: a quantitative analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2386-2392.

14. Brody JM, Hulstyn MJ, Fleming BC, Tung GA. The meniscal roots: Gross anatomic correlation with 3-T MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(5):W446-W450.

15. Brody JM, Lin HM, Hulstyn MJ, Tung GA. Lateral meniscus root tear and meniscus extrusion with anterior cruciate ligament tear. Radiology. 2006;239(3):805-810.

16. Poh S-Y, Yew K-SA, Wong P-LK, et al. Role of the anterior intermeniscal ligament in tibiofemoral contact mechanics during axial joint loading. Knee. 2012;19(2):135-139.

17. Naranje S, Mittal R, Nag H, Sharma R. Arthroscopic and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of meniscus lesions in the chronic anterior ligament–deficient knee. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):1045-1051.

18. Magee T. MR findings of meniscal extrusion correlated with arthroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(2):466-470.

19. Kim SB, Ha JK, Lee SW, et al. Medial meniscus root tear refixation: comparison of clinical, radiologic, and arthroscopic findings with medial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(3):346-354.

20. LaPrade CM, Smith SD, Rasmussen MT, et al. Consequences of tibial tunnel reaming on the meniscal roots during cruciate ligament reconstruction in a cadaveric model, part 1: the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(1):200-206.

21. Ellman MB, James EW, Laprade CM, Laprade RF. Anterior meniscus root avulsion following intramedullary nailing for a tibial shaft fracture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(4):1188-1191.

22. Hwang BY, Kim SJ, Lee SW, et al. Risk factors for medial meniscus posterior root tear. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1606-1610.

23. Binfield PM, Maffulli N, King JB. Patterns of meniscal tears associated with anterior cruciate ligament lesions in athletes. Injury. 1993;24(8):557-561.

24. Wu WH, Hackett T, Richmond JC. Effects of meniscal and articular surface status on knee stability, function, and symptoms after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a long-term prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(6):845-850.

25. Pagnani MJ, Cooper DE, Warren RF. Extrusion of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy. 1991;7(3):297-300.

26. Lerer DB, Umans HR, Hu MX, Jones MH. The role of meniscal root pathology and radial meniscal tear in medial meniscal extrusion. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33(10):569-574.

27. Costa CR, Morrison WB, Carrino JA. Medial meniscus extrusion on knee MRI: Is extent associated with severity of degeneration or type of tear? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(1):17-23.

28. LaPrade RF, Ho CP, James E, Crespo B, LaPrade CM, Matheny LM. Diagnostic accuracy of 3.0 T magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of meniscus posterior root pathology. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroscopy. 2015;23(1):152-157.

29. Chung KS, Ha JK, Yeom CH, et al. Comparison of clinical and radiologic results between partial meniscectomy and refixation of medial mensicus posterior root tears: a minimum 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(10):1941-1950.

Intact and well functioning menisci are essential for optimal knee function. Articular cartilage damage and rapid joint degeneration have been observed in knees after meniscectomy.1-5 Meniscal root tears and avulsions are now increasingly recognized as a functional equivalent to total meniscectomy, and will follow a similar course if left untreated.6-8

The menisci provide shock absorption and stability through their unique anatomy and physiology. Their essential role in dissipation of the axial load encountered during daily activities is accomplished via generation of circumferential hoop stress.4,5,9 Tears of the horn or body may diminish this ability depending on the size and location, but a tear or an avulsion that renders the root incompetent will leave the meniscus unable to generate hoop stress.10 Likewise, as the menisci have been shown to be important secondary stabilizers for both translation and rotation, this function is lost or significantly diminished in the setting of a root tear.6,11,12

Despite their clinical and biomechanical implications, meniscal root tears can be difficult to identify, particularly when they are not actively sought. The goal of this article is to highlight the current diagnostic workup and treatment in patients with suspected meniscal root pathology. We will also aim to emphasize important anatomic and biomechanical considerations when attempting a meniscal root repair.

Anatomy

The menisci are 2 fibrocartilage wedge-shaped structures that surround the medial and lateral tibial plateau’s weight-bearing surfaces. They are attached at many points along their periphery via coronary ligaments that comprise a continuous junction of the meniscus to the capsule to the tibial plateau. Each meniscus has an anterior and a posterior horn that are securely anchored to the tibial intercondylar region via strong ligaments known as the roots.

The anterior medial root attaches just anterior and medial to the medial tibial spine. The anterior lateral root attaches just anterior to the lateral tibial spine. The medial and lateral anterior horns of the menisci are also connected via the anterior intermeniscal ligament (AIML).13-15 Recent cadaveric biomechanical studies have questioned the importance of the AIML, demonstrating no significant change in contact pressure or area before and after sectioning.16 Another important consideration with respect to the anterior root insertion of the lateral meniscus is its intimate relationship with the tibial insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). The anterior lateral root and the ACL share over 60% of their tibial footprints.13,17

When the menisci are competent, they absorb between 40% to 70% of the contact force generated between the femur and tibia.1 By providing strong anchor points, the meniscal roots allow the horns and bodies of the menisci to maintain a stable position that maximizes congruency with the femoral condyles.

Pathology

The conversion of axial load to circumferential hoop stresses occur as the resilient, yet pliable, menisci are squeezed between the femoral condyle and tibial plateau. However, this function is dependent on secure attachment sites at the roots. In the setting of root tear, there is no restraint to the peripheral distortion of the menisci, and meniscal extrusion can occur.18

Clinical evidence and biomechanical evidence strongly show the consequences of meniscectomy. Multiple studies have shown similar findings and have proven that a meniscal root tear or avulsion is the biomechanical equivalent to total meniscectomy.3 With meniscectomy, not only do peak pressures within compartments increase significantly, it has been demonstrated that other compartments within the knee with intact menisci do not have increases in compartment pressures, lending more evidence to the menisci functioning as separate units.16 It has also been found that anterior/posterior translation is increased with medial meniscal root tears. When lateral meniscus root tears were studied with associated ACL tear, the pivot shift motion was found to be exaggerated.6

However, the finding of utmost importance in these biomechanical studies is that peak pressures and excessive tibiofemoral motion are restored to normal levels after meniscal root repair. Therefore, repair of meniscal root tears restores native knee biomechanics and will potentially prevent arthritic sequelae from developing.3,4,7,19

Epidemiology

Tears of the posterior root of either menisci are more common than their anterior counterparts, and have been more extensively studied. However, there are situations that can lead to anterior root tears, specifically during ACL reconstruction and during medullary nailing of the tibia.20,21 Barring iatrogenic injury, the anterior horn is less at risk for injury than the posterior horn given the biomechanical environment of the knee.3

Medial meniscus posterior root tears are more common than lateral tears. However, these are often more chronic in nature and not associated with an acute event. Risk factors for medial meniscus root tear include increased body mass index, varus mechanical axis, female gender, and low activity level.22

Lateral meniscus root tears more commonly occur during trauma with sprains and/or tears of knee ligaments.23 Along with increased recognition of meniscal root injuries associated with knee ligamentous injury comes the recognition that certain ligamentous reconstructions—namely the ACL—are more prone to failure and have higher stresses when a root tear is left untreated.17,24

Diagnosis

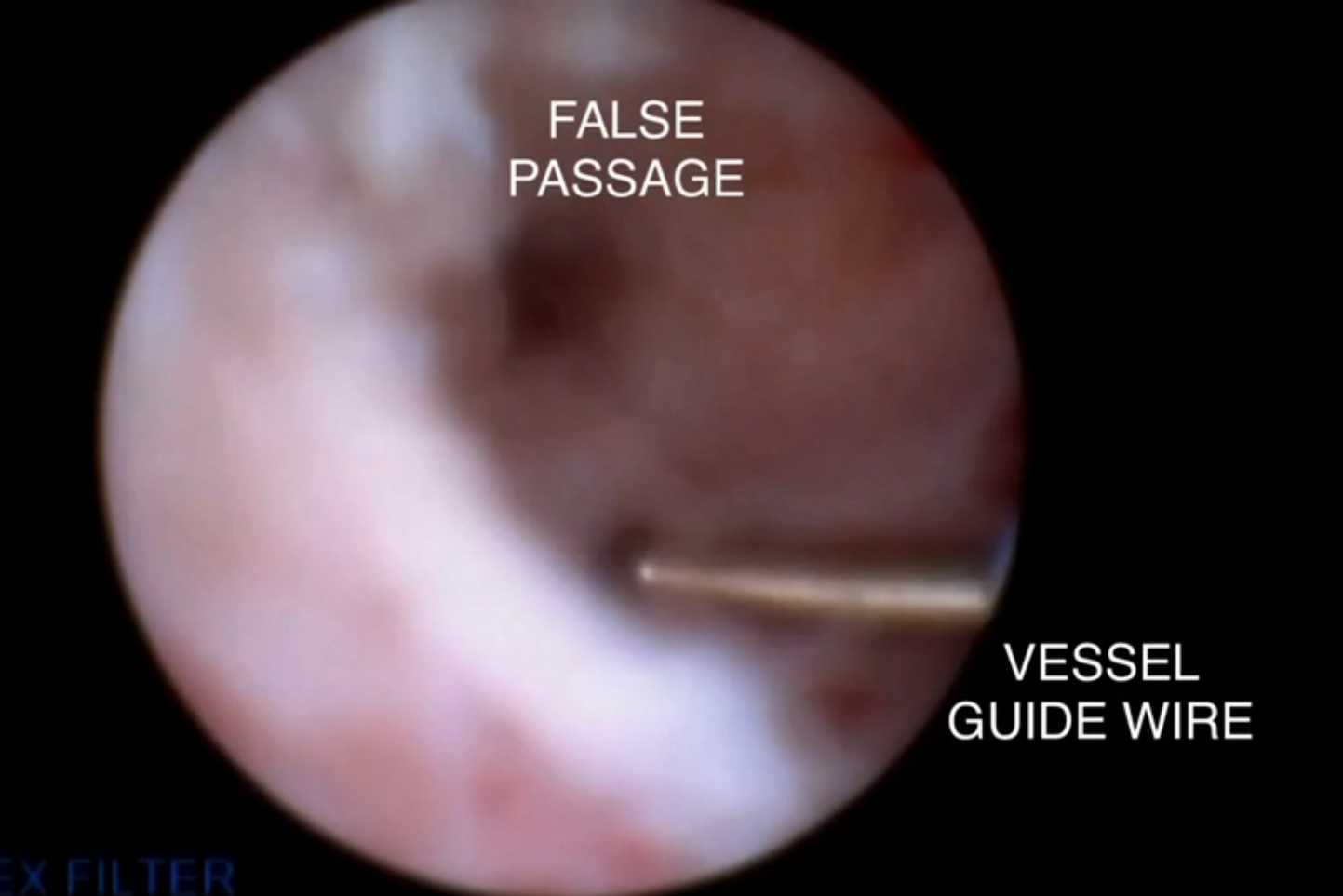

The gold standard for diagnosis of a meniscal root lesion is under direct visualization during arthroscopy.18 The meniscal roots must be probed and stressed to assess their integrity regardless of the initial indication for knee arthroscopy. In most cases, however, the diagnosis of meniscal root tears should occur prior to proceeding to the operating room.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used to aid in diagnosis of meniscal root tears since the early 1990s.25 Now, with the widespread use of MRI, understanding and diagnosis of meniscal root pathology has increased. All sequences should be reviewed, but T2 weighted coronal sections should provide the best visualization of the posterior roots (Figures 1A, 1B). Sagittal sections may also be helpful in this diagnosis. Increased signal within the root or horn may represent partial or full thickness tears, or may show a more degenerative process with fraying.14,15,26,27

MRI does have limitations, however. When compared to arthroscopy, the sensitivity of 3T MRI to identify posterior root tears is 77%, and specificity is 73%. Medial root tears are more readily identified on MRI than lateral tears.28 This further highlights the need for high suspicion during arthroscopy with the requisite equipment on standby should it be needed.

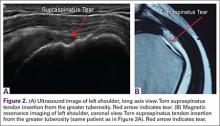

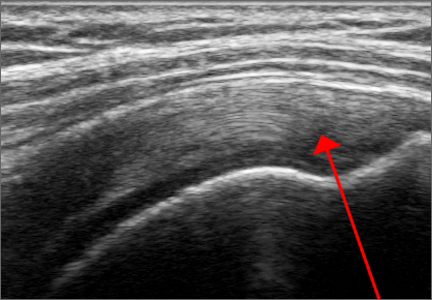

A concerning finding that may be observed on MRI includes meniscal extrusion (Figures 2A, 2B). Most often seen with the medial meniscus, extrusion is diagnosed when the meniscal body displaces greater than 3 mm past the tibial articular surface on a midcoronal image.26,27 Over 50% of patients with medial meniscal extrusion on MRI will have medial meniscal root tears.26,27 Conversely, meniscal extrusion is less common in lateral menisci for multiple reasons. The lateral compartment of the knee does not have as high contact pressure as the medial compartment, so the lateral meniscus is not as likely to be extruded from the joint. Additionally, the posterior lateral root has the added benefit of further stability from meniscofemoral ligaments.11 They provide a restraint to meniscal extrusion, with a reported rate of 14% lateral meniscus extrusion when they are intact. If the meniscofemoral ligaments are not present or torn in the setting of posterior root tear, the lateral meniscus extrusion rate quadruples and approaches that of medial meniscal extrusion.15

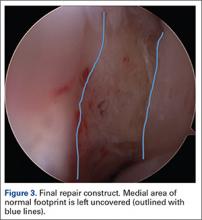

Another finding indicative of meniscal root tear is the “ghost meniscus” (Figure 3). The posterior horn and anterior horn should both be visible in sagittal cuts on MRI. When the anterior horn is present, but the posterior horn is not visualized, it is termed a “ghost meniscus.” This MRI finding is highly associated with meniscal root tears, and will often be found along with meniscal extrusion on coronal sequencing.27,28

Treatment

Historically, large meniscal tears, extruded menisci, or root avulsions have been treated with conservative observation if asymptomatic, or with meniscectomy when symptomatic. With a meniscal root tear, both forms of treatment will not provide lasting benefit and rapid joint degeneration ensues. Evidence now supports repair over meniscectomy when treating root tears.7,8,19,29

Patients who have meniscal root tears that are likely sequelae of an arthritic process are not candidates for meniscal root repair. These patients will often have known arthritis with an intact meniscus and then progress to meniscal pathology, most often medially. Because arthritis is the cause of these meniscal tears, a repair will not reverse this process; such repairs will likely fail, and the patient will re-tear the meniscus. For this subset of patients, physical therapy and activity modification are appropriate treatment.

Repair is indicated for patients with acute tears, with or without associated soft tissue injury to the knee, and those with chronic or acute on chronic tears with minimal arthritis within the knee. The authors’ preferred method of repair is via suture fixation through transosseous tunnel (Figures 4A-4F).

Once a root tear has been identified during arthroscopy, it should be probed and/or grasped and pulled to confirm its integrity. A shaver is then used to debride any fraying of the meniscus and to debride the anatomic footprint of the root. Curettes and rasps are used to prepare the meniscal bed at the center of its insertion and the undersurface of the meniscal root. Once the attachment site of the root insertion has been prepared, an ACL tip-to-tip drill guide is placed over the prepared bed. For repair of a medial meniscus posterior root, a 2.4-mm drill tip guide pin is inserted through the guide via an incision made at the anteromedial tibia. For repair of the lateral meniscus posterior root, the pin is inserted through an incision at the anterolateral aspect of the tibia.

Once the guide pin has been inserted and is visualized at the center of the root footprint, it is held in place by a hemostat or grasper placed intra-articularly. Next, the guide pin is overreamed with a 4.5-mm cannulated drill bit. The transosseous tunnel is then further prepared using a shaver to remove excess soft tissue surrounding the tunnel entrance at the tibial plateau. Further rasping around the edges of the tunnel is performed to make final preparations.

Attention is then turned back to the meniscal root. Using a FastPass Scorpion (Arthrex), 2 or 3 size 0 fiber wire sutures are passed through the root, and a cinch stitch is then secured leaving four to six stands (2 from each Scorpion pass) in the root. A FiberStick is then introduced into the tibial bone tunnel and each strand of the 0 fiberwire is retrieved. Once the FiberWire attached to the meniscal root is in the tunnel, the meniscus should be directly visualized as the appropriate tension is toggled to reduce the meniscal root into its footprint. In order to securely fasten the meniscal root, an Arthrex SwiveLock 4.75-mm suture anchor is used. The meniscus is again probed to assess the integrity of the repair. Of note, an alternative method of fixation is accomplished by tying the fiberwire over an Arthrex suture button at the anterior tibia.

Postoperatively, weight bearing restriction is warranted, along with range of motion restrictions. During the first 2 weeks, patients will be counseled to be touch down weight bearing with the use of crutches or a walker. During this period, range of motion will be restricted by hinged knee brace to 30° of flexion and full extension. The next 2-week period will advance to progressive partial weight bearing, again with crutches or a walker. Range of motion will also be expanded to 60° of flexion. After a month, the patient will then be allowed to be full weight bearing as tolerated and be weaned from assistive ambulation devices. Range of motion will then be 90° of flexion. It is paramount that full extension be achieved and maintained in the early postoperative period. Quadriceps strengthening should also proceed with unlimited straight leg raises throughout this period as well.

Intact and well functioning menisci are essential for optimal knee function. Articular cartilage damage and rapid joint degeneration have been observed in knees after meniscectomy.1-5 Meniscal root tears and avulsions are now increasingly recognized as a functional equivalent to total meniscectomy, and will follow a similar course if left untreated.6-8

The menisci provide shock absorption and stability through their unique anatomy and physiology. Their essential role in dissipation of the axial load encountered during daily activities is accomplished via generation of circumferential hoop stress.4,5,9 Tears of the horn or body may diminish this ability depending on the size and location, but a tear or an avulsion that renders the root incompetent will leave the meniscus unable to generate hoop stress.10 Likewise, as the menisci have been shown to be important secondary stabilizers for both translation and rotation, this function is lost or significantly diminished in the setting of a root tear.6,11,12

Despite their clinical and biomechanical implications, meniscal root tears can be difficult to identify, particularly when they are not actively sought. The goal of this article is to highlight the current diagnostic workup and treatment in patients with suspected meniscal root pathology. We will also aim to emphasize important anatomic and biomechanical considerations when attempting a meniscal root repair.

Anatomy

The menisci are 2 fibrocartilage wedge-shaped structures that surround the medial and lateral tibial plateau’s weight-bearing surfaces. They are attached at many points along their periphery via coronary ligaments that comprise a continuous junction of the meniscus to the capsule to the tibial plateau. Each meniscus has an anterior and a posterior horn that are securely anchored to the tibial intercondylar region via strong ligaments known as the roots.

The anterior medial root attaches just anterior and medial to the medial tibial spine. The anterior lateral root attaches just anterior to the lateral tibial spine. The medial and lateral anterior horns of the menisci are also connected via the anterior intermeniscal ligament (AIML).13-15 Recent cadaveric biomechanical studies have questioned the importance of the AIML, demonstrating no significant change in contact pressure or area before and after sectioning.16 Another important consideration with respect to the anterior root insertion of the lateral meniscus is its intimate relationship with the tibial insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). The anterior lateral root and the ACL share over 60% of their tibial footprints.13,17

When the menisci are competent, they absorb between 40% to 70% of the contact force generated between the femur and tibia.1 By providing strong anchor points, the meniscal roots allow the horns and bodies of the menisci to maintain a stable position that maximizes congruency with the femoral condyles.

Pathology

The conversion of axial load to circumferential hoop stresses occur as the resilient, yet pliable, menisci are squeezed between the femoral condyle and tibial plateau. However, this function is dependent on secure attachment sites at the roots. In the setting of root tear, there is no restraint to the peripheral distortion of the menisci, and meniscal extrusion can occur.18

Clinical evidence and biomechanical evidence strongly show the consequences of meniscectomy. Multiple studies have shown similar findings and have proven that a meniscal root tear or avulsion is the biomechanical equivalent to total meniscectomy.3 With meniscectomy, not only do peak pressures within compartments increase significantly, it has been demonstrated that other compartments within the knee with intact menisci do not have increases in compartment pressures, lending more evidence to the menisci functioning as separate units.16 It has also been found that anterior/posterior translation is increased with medial meniscal root tears. When lateral meniscus root tears were studied with associated ACL tear, the pivot shift motion was found to be exaggerated.6

However, the finding of utmost importance in these biomechanical studies is that peak pressures and excessive tibiofemoral motion are restored to normal levels after meniscal root repair. Therefore, repair of meniscal root tears restores native knee biomechanics and will potentially prevent arthritic sequelae from developing.3,4,7,19

Epidemiology

Tears of the posterior root of either menisci are more common than their anterior counterparts, and have been more extensively studied. However, there are situations that can lead to anterior root tears, specifically during ACL reconstruction and during medullary nailing of the tibia.20,21 Barring iatrogenic injury, the anterior horn is less at risk for injury than the posterior horn given the biomechanical environment of the knee.3

Medial meniscus posterior root tears are more common than lateral tears. However, these are often more chronic in nature and not associated with an acute event. Risk factors for medial meniscus root tear include increased body mass index, varus mechanical axis, female gender, and low activity level.22

Lateral meniscus root tears more commonly occur during trauma with sprains and/or tears of knee ligaments.23 Along with increased recognition of meniscal root injuries associated with knee ligamentous injury comes the recognition that certain ligamentous reconstructions—namely the ACL—are more prone to failure and have higher stresses when a root tear is left untreated.17,24

Diagnosis

The gold standard for diagnosis of a meniscal root lesion is under direct visualization during arthroscopy.18 The meniscal roots must be probed and stressed to assess their integrity regardless of the initial indication for knee arthroscopy. In most cases, however, the diagnosis of meniscal root tears should occur prior to proceeding to the operating room.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used to aid in diagnosis of meniscal root tears since the early 1990s.25 Now, with the widespread use of MRI, understanding and diagnosis of meniscal root pathology has increased. All sequences should be reviewed, but T2 weighted coronal sections should provide the best visualization of the posterior roots (Figures 1A, 1B). Sagittal sections may also be helpful in this diagnosis. Increased signal within the root or horn may represent partial or full thickness tears, or may show a more degenerative process with fraying.14,15,26,27

MRI does have limitations, however. When compared to arthroscopy, the sensitivity of 3T MRI to identify posterior root tears is 77%, and specificity is 73%. Medial root tears are more readily identified on MRI than lateral tears.28 This further highlights the need for high suspicion during arthroscopy with the requisite equipment on standby should it be needed.

A concerning finding that may be observed on MRI includes meniscal extrusion (Figures 2A, 2B). Most often seen with the medial meniscus, extrusion is diagnosed when the meniscal body displaces greater than 3 mm past the tibial articular surface on a midcoronal image.26,27 Over 50% of patients with medial meniscal extrusion on MRI will have medial meniscal root tears.26,27 Conversely, meniscal extrusion is less common in lateral menisci for multiple reasons. The lateral compartment of the knee does not have as high contact pressure as the medial compartment, so the lateral meniscus is not as likely to be extruded from the joint. Additionally, the posterior lateral root has the added benefit of further stability from meniscofemoral ligaments.11 They provide a restraint to meniscal extrusion, with a reported rate of 14% lateral meniscus extrusion when they are intact. If the meniscofemoral ligaments are not present or torn in the setting of posterior root tear, the lateral meniscus extrusion rate quadruples and approaches that of medial meniscal extrusion.15

Another finding indicative of meniscal root tear is the “ghost meniscus” (Figure 3). The posterior horn and anterior horn should both be visible in sagittal cuts on MRI. When the anterior horn is present, but the posterior horn is not visualized, it is termed a “ghost meniscus.” This MRI finding is highly associated with meniscal root tears, and will often be found along with meniscal extrusion on coronal sequencing.27,28

Treatment

Historically, large meniscal tears, extruded menisci, or root avulsions have been treated with conservative observation if asymptomatic, or with meniscectomy when symptomatic. With a meniscal root tear, both forms of treatment will not provide lasting benefit and rapid joint degeneration ensues. Evidence now supports repair over meniscectomy when treating root tears.7,8,19,29

Patients who have meniscal root tears that are likely sequelae of an arthritic process are not candidates for meniscal root repair. These patients will often have known arthritis with an intact meniscus and then progress to meniscal pathology, most often medially. Because arthritis is the cause of these meniscal tears, a repair will not reverse this process; such repairs will likely fail, and the patient will re-tear the meniscus. For this subset of patients, physical therapy and activity modification are appropriate treatment.

Repair is indicated for patients with acute tears, with or without associated soft tissue injury to the knee, and those with chronic or acute on chronic tears with minimal arthritis within the knee. The authors’ preferred method of repair is via suture fixation through transosseous tunnel (Figures 4A-4F).

Once a root tear has been identified during arthroscopy, it should be probed and/or grasped and pulled to confirm its integrity. A shaver is then used to debride any fraying of the meniscus and to debride the anatomic footprint of the root. Curettes and rasps are used to prepare the meniscal bed at the center of its insertion and the undersurface of the meniscal root. Once the attachment site of the root insertion has been prepared, an ACL tip-to-tip drill guide is placed over the prepared bed. For repair of a medial meniscus posterior root, a 2.4-mm drill tip guide pin is inserted through the guide via an incision made at the anteromedial tibia. For repair of the lateral meniscus posterior root, the pin is inserted through an incision at the anterolateral aspect of the tibia.

Once the guide pin has been inserted and is visualized at the center of the root footprint, it is held in place by a hemostat or grasper placed intra-articularly. Next, the guide pin is overreamed with a 4.5-mm cannulated drill bit. The transosseous tunnel is then further prepared using a shaver to remove excess soft tissue surrounding the tunnel entrance at the tibial plateau. Further rasping around the edges of the tunnel is performed to make final preparations.

Attention is then turned back to the meniscal root. Using a FastPass Scorpion (Arthrex), 2 or 3 size 0 fiber wire sutures are passed through the root, and a cinch stitch is then secured leaving four to six stands (2 from each Scorpion pass) in the root. A FiberStick is then introduced into the tibial bone tunnel and each strand of the 0 fiberwire is retrieved. Once the FiberWire attached to the meniscal root is in the tunnel, the meniscus should be directly visualized as the appropriate tension is toggled to reduce the meniscal root into its footprint. In order to securely fasten the meniscal root, an Arthrex SwiveLock 4.75-mm suture anchor is used. The meniscus is again probed to assess the integrity of the repair. Of note, an alternative method of fixation is accomplished by tying the fiberwire over an Arthrex suture button at the anterior tibia.

Postoperatively, weight bearing restriction is warranted, along with range of motion restrictions. During the first 2 weeks, patients will be counseled to be touch down weight bearing with the use of crutches or a walker. During this period, range of motion will be restricted by hinged knee brace to 30° of flexion and full extension. The next 2-week period will advance to progressive partial weight bearing, again with crutches or a walker. Range of motion will also be expanded to 60° of flexion. After a month, the patient will then be allowed to be full weight bearing as tolerated and be weaned from assistive ambulation devices. Range of motion will then be 90° of flexion. It is paramount that full extension be achieved and maintained in the early postoperative period. Quadriceps strengthening should also proceed with unlimited straight leg raises throughout this period as well.

1. Kidron A, Thein R. Radial tears associated with cleavage tears of the medial meniscus in athletes. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(3):254-256.

2. Fairbank TJ. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30B(4):664-670.

3. Allaire R, Muriuki M, Gilbertson L, Harner CD. Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus: similar to total meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg. 2008;90(9):1922-1931.

4. Marzo JM, Gurske-DePerio J. Effects of medial meniscus posterior horn avulsion and repair on tibiofemoral contact area and peak contact pressure with clinical implications. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(1):124-129.

5. Hein CN, Deperio JG, Ehrensberger MT, Marzo JM. Effects of medial meniscal posterior horn avulsion and repair on meniscal displacement. Knee. 2011;18(3):189-192.

6. Shybut TB, Vega CE, Haddad J, et al. Effect of lateral meniscal root tear on the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):905-911.

7. Vyas D, Harner CD. Meniscus root repair. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2012;20(2):86-94.

8. Koenig JH, Ranawat AS, Umans HR, Difelice GS. Meniscal root tears: diagnosis and treatment. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(9):1025-1032.

9. Fithian DC, Kelly MA, Mow VC. Material properties and structure-function relationships in the menisci. Clin Orthop. 1990;(252):19-31.

10. Weaver JB. Ossification of the internal semilunar cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg. 1935;17(1):195-198.

11. Ahn JH, Lee YS, Chang JY, Chang MJ, Eun SS, Kim SM. Arthroscopic all inside repair of the lateral meniscus root tear. Knee. 2009;16(1):77-80.

12. Bellabarba C, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR Jr. Patterns of meniscal injury in the anterior cruciate–deficient knee: a review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 1997;26(1):18-23.

13. LaPrade CM, Ellman MB, Rasmussen MT, et al. Anatomy of the anterior root attachments of the medial and lateral menisci: a quantitative analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2386-2392.

14. Brody JM, Hulstyn MJ, Fleming BC, Tung GA. The meniscal roots: Gross anatomic correlation with 3-T MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(5):W446-W450.

15. Brody JM, Lin HM, Hulstyn MJ, Tung GA. Lateral meniscus root tear and meniscus extrusion with anterior cruciate ligament tear. Radiology. 2006;239(3):805-810.

16. Poh S-Y, Yew K-SA, Wong P-LK, et al. Role of the anterior intermeniscal ligament in tibiofemoral contact mechanics during axial joint loading. Knee. 2012;19(2):135-139.

17. Naranje S, Mittal R, Nag H, Sharma R. Arthroscopic and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of meniscus lesions in the chronic anterior ligament–deficient knee. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):1045-1051.

18. Magee T. MR findings of meniscal extrusion correlated with arthroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(2):466-470.

19. Kim SB, Ha JK, Lee SW, et al. Medial meniscus root tear refixation: comparison of clinical, radiologic, and arthroscopic findings with medial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(3):346-354.

20. LaPrade CM, Smith SD, Rasmussen MT, et al. Consequences of tibial tunnel reaming on the meniscal roots during cruciate ligament reconstruction in a cadaveric model, part 1: the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(1):200-206.

21. Ellman MB, James EW, Laprade CM, Laprade RF. Anterior meniscus root avulsion following intramedullary nailing for a tibial shaft fracture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(4):1188-1191.

22. Hwang BY, Kim SJ, Lee SW, et al. Risk factors for medial meniscus posterior root tear. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1606-1610.

23. Binfield PM, Maffulli N, King JB. Patterns of meniscal tears associated with anterior cruciate ligament lesions in athletes. Injury. 1993;24(8):557-561.

24. Wu WH, Hackett T, Richmond JC. Effects of meniscal and articular surface status on knee stability, function, and symptoms after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a long-term prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(6):845-850.

25. Pagnani MJ, Cooper DE, Warren RF. Extrusion of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy. 1991;7(3):297-300.

26. Lerer DB, Umans HR, Hu MX, Jones MH. The role of meniscal root pathology and radial meniscal tear in medial meniscal extrusion. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33(10):569-574.

27. Costa CR, Morrison WB, Carrino JA. Medial meniscus extrusion on knee MRI: Is extent associated with severity of degeneration or type of tear? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(1):17-23.

28. LaPrade RF, Ho CP, James E, Crespo B, LaPrade CM, Matheny LM. Diagnostic accuracy of 3.0 T magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of meniscus posterior root pathology. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroscopy. 2015;23(1):152-157.

29. Chung KS, Ha JK, Yeom CH, et al. Comparison of clinical and radiologic results between partial meniscectomy and refixation of medial mensicus posterior root tears: a minimum 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(10):1941-1950.

1. Kidron A, Thein R. Radial tears associated with cleavage tears of the medial meniscus in athletes. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(3):254-256.

2. Fairbank TJ. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30B(4):664-670.

3. Allaire R, Muriuki M, Gilbertson L, Harner CD. Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus: similar to total meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg. 2008;90(9):1922-1931.

4. Marzo JM, Gurske-DePerio J. Effects of medial meniscus posterior horn avulsion and repair on tibiofemoral contact area and peak contact pressure with clinical implications. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(1):124-129.

5. Hein CN, Deperio JG, Ehrensberger MT, Marzo JM. Effects of medial meniscal posterior horn avulsion and repair on meniscal displacement. Knee. 2011;18(3):189-192.

6. Shybut TB, Vega CE, Haddad J, et al. Effect of lateral meniscal root tear on the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):905-911.

7. Vyas D, Harner CD. Meniscus root repair. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2012;20(2):86-94.

8. Koenig JH, Ranawat AS, Umans HR, Difelice GS. Meniscal root tears: diagnosis and treatment. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(9):1025-1032.

9. Fithian DC, Kelly MA, Mow VC. Material properties and structure-function relationships in the menisci. Clin Orthop. 1990;(252):19-31.

10. Weaver JB. Ossification of the internal semilunar cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg. 1935;17(1):195-198.

11. Ahn JH, Lee YS, Chang JY, Chang MJ, Eun SS, Kim SM. Arthroscopic all inside repair of the lateral meniscus root tear. Knee. 2009;16(1):77-80.

12. Bellabarba C, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR Jr. Patterns of meniscal injury in the anterior cruciate–deficient knee: a review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 1997;26(1):18-23.

13. LaPrade CM, Ellman MB, Rasmussen MT, et al. Anatomy of the anterior root attachments of the medial and lateral menisci: a quantitative analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2386-2392.

14. Brody JM, Hulstyn MJ, Fleming BC, Tung GA. The meniscal roots: Gross anatomic correlation with 3-T MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(5):W446-W450.

15. Brody JM, Lin HM, Hulstyn MJ, Tung GA. Lateral meniscus root tear and meniscus extrusion with anterior cruciate ligament tear. Radiology. 2006;239(3):805-810.

16. Poh S-Y, Yew K-SA, Wong P-LK, et al. Role of the anterior intermeniscal ligament in tibiofemoral contact mechanics during axial joint loading. Knee. 2012;19(2):135-139.

17. Naranje S, Mittal R, Nag H, Sharma R. Arthroscopic and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of meniscus lesions in the chronic anterior ligament–deficient knee. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):1045-1051.

18. Magee T. MR findings of meniscal extrusion correlated with arthroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(2):466-470.

19. Kim SB, Ha JK, Lee SW, et al. Medial meniscus root tear refixation: comparison of clinical, radiologic, and arthroscopic findings with medial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(3):346-354.

20. LaPrade CM, Smith SD, Rasmussen MT, et al. Consequences of tibial tunnel reaming on the meniscal roots during cruciate ligament reconstruction in a cadaveric model, part 1: the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(1):200-206.

21. Ellman MB, James EW, Laprade CM, Laprade RF. Anterior meniscus root avulsion following intramedullary nailing for a tibial shaft fracture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(4):1188-1191.

22. Hwang BY, Kim SJ, Lee SW, et al. Risk factors for medial meniscus posterior root tear. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1606-1610.

23. Binfield PM, Maffulli N, King JB. Patterns of meniscal tears associated with anterior cruciate ligament lesions in athletes. Injury. 1993;24(8):557-561.

24. Wu WH, Hackett T, Richmond JC. Effects of meniscal and articular surface status on knee stability, function, and symptoms after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a long-term prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(6):845-850.

25. Pagnani MJ, Cooper DE, Warren RF. Extrusion of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy. 1991;7(3):297-300.

26. Lerer DB, Umans HR, Hu MX, Jones MH. The role of meniscal root pathology and radial meniscal tear in medial meniscal extrusion. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33(10):569-574.

27. Costa CR, Morrison WB, Carrino JA. Medial meniscus extrusion on knee MRI: Is extent associated with severity of degeneration or type of tear? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(1):17-23.

28. LaPrade RF, Ho CP, James E, Crespo B, LaPrade CM, Matheny LM. Diagnostic accuracy of 3.0 T magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of meniscus posterior root pathology. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroscopy. 2015;23(1):152-157.

29. Chung KS, Ha JK, Yeom CH, et al. Comparison of clinical and radiologic results between partial meniscectomy and refixation of medial mensicus posterior root tears: a minimum 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(10):1941-1950.

A Guide to Ultrasound of the Shoulder, Part 1: Coding and Reimbursement

Although ultrasound has been around for many years, the technology is underutilized. It has been used primarily by the radiologists and obstetricians-gynecologists. However, orthopedic surgeons and sports medicine doctors are beginning to realize the utility of this imaging modality for their specialties. Ultrasound has classically been used as a diagnostic tool. This usage is beneficial to sports medicine specialists for on-field coverage at sports competitions to efficiently evaluate injuries without the need for taking the athletes back to the locker room for an x-ray or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Ultrasound can quickly assess for damage to soft tissue, joints, and superficial bones. Another of ultrasound’s benefits is its use as an adjunct to treatment. Ultrasound has been shown to vastly increase the accuracy of injections and can be used in surgery to accurately guide percutaneous techniques or to identify structures that previously required radiation-exposing fluoroscopy or large incisions to find by feel or eye.

Ultrasound is a technician-dependent modality. The surgeon and physician must become facile with the use of the probe and how ultrasound works. The use of the probe is similar to an arthroscope, requiring small movements of the hand to reveal the best imaging of the tissues. Rather than relying on just the patient’s position with an immobile machine, the user must use the probe position and the placement of the patient’s limb or body to optimize the use of ultrasound. Doing so saves time, money, and exposure to dangerous radiation. In a retrospective study of 1012 patients treated over a 10-month period, Sivan and colleagues1 concluded that the use of clinic-based musculoskeletal (MSK) ultrasound enables a one-stop approach, reduces repeat hospital appointments, and improves quality of care.With the increased use of ultrasound comes the need to accurately code and bill for the use of ultrasound. According to the College of Radiology, Medicare reimbursements for MSK ultrasound studies has increased by 316% from 2000-2009.2 Paradoxically, ultrasound has still been relatively underutilized when compared to the use of MSK MRI.

Diagnostic Ultrasound

Ultrasound is based off sound waves, emitted from a transducer, which are then bounced back off the underlying structures based on the density of that structure. The computer interprets the returning sound waves and produces an image reflecting the quality and strength of those returning waves. When the sound waves are bounced back strongly and quickly, like when hitting bone, we see an image that is intensely white (“hyperechoic”). When the sound waves encounter a substance that transmits those waves easily and do not return, like air or fluid, the image is dark (“hypoechoic”).

Ultrasound’s fundamental advantages start with every patient being able to have an ultrasound: no interference from metal, pacemakers, claustrophobia, or obesity. Contralateral comparisons, sono-palpation at the site of pathology, and real-time dynamic studies allow for a more comprehensive diagnostic evaluation. Doppler capabilities can further expand the usefulness of the evaluation and guide safer interventions. With the advent of high-resolution portable ultrasound machines, these studies can essentially be performed anywhere, and are typically done in a timely and cost-effective manner.

Ultrasound has many diagnostic uses for soft tissue, joint, and bone disorders. For soft tissues, ultrasound can image tears of muscles, tendons, and ligaments; show inflammation like tenosynovitis; demonstrate masses like hematomas, cysts, solid tumors, or calcific tendonitis; display nerve disorders like Morton’s neuroma; or confirm foreign bodies or infections.3-5 For joint disorders, ultrasound can show erosions on bones, loose bodies, pannus, inflammation, or effusions. For bone disorders, ultrasound can diagnose fractures and, sometimes, even stress fractures. Tomer and colleagues6 compared 51 patients with bone contusions and fractures; they determined that ultrasound was most reliable in the diagnosis of long bone diaphyseal fractures. The one disadvantage, especially when compared to MRI, is ultrasound’s inability to fully evaluate intra-articular or deep structures such as articular cartilage, the glenohumeral labrum, the biceps’ anchor, etc.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

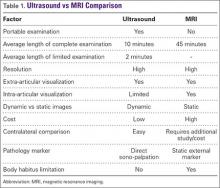

Ultrasound is similar to MRI as it images tissues and gives us ideas whether that tissue is normal, damaged, or diseased (Figures 1A, 1B). MRI is based on magnetics and large machines that cannot be moved. MRI yields planar images that can only be changed by changing the position of the limb or body in the MRI tube. This can create an issue with obese patients or with postoperative patients who cannot maintain the operated body part in one position for the length of the MRI scan. Ultrasound is better tolerated by patients without the need for claustrophobic large machines (Table 1). In 2004, Middleton and colleagues7 surveyed 118 patients who obtained an ultrasound and MRI of the shoulder for suspected rotator cuff pathology; ultrasound had higher satisfaction levels, and 93% of patients preferred ultrasound to MRI.

For rotator cuff tears, ultrasound is also comparable diagnostically with MRI (Figures 2A, 2B). In a prospective study of 124 patients, MRI and ultrasound had comparable accuracy for identifying and measuring the size of full-thickness and partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, with arthroscopic findings used as the standard.8 A 2015 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine showed that the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound, MRI, and MR arthrography in the characterization of full thickness rotator cuff tears had >90% sensitivity and specificity. As for partial rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy, overall estimates of specificity were also high (>90%), while sensitivity was as high as 83%. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound was similar whether it was performed by a trained radiologist, sonographer, or orthopedist.9

Medicare reimbursements for MSK ultrasound studies has increased by 316% in the past decade.2 Private practice MSK ultrasound procedures increased from 19,372 in 2000 to 158,351 in 2009.2 In 2010, non-radiologists accounted for more ultrasound-guided procedures than radiologists for the first time.10 MSK ultrasound is still underutilized compared to MRI. This underutilization is also unfortunate economically. The cost of MRIs is significantly higher. According to Parker and colleagues10, the projected Medicare cost for MSK imaging in 2020 is $3.6 billion, with MRI accounting for $2 billion. They also concluded that replacing MSK MRI with MSK ultrasound when clinically indicated could save over $6.9 billion between 2006 and 2020.11

Ultrasound-Guided Procedures

MSK ultrasound has gained significant ground on other imaging modalities when it comes to procedures, both in office and in the operating room. The ability to have a small, mobile, inexpensive machine that can be used in real time has dramatically changed how interventions are done. Most imaging modalities used to perform injections or percutaneous surgery use fluoroscopy machines. This exposes the patients to significant radiation, costs significantly more, and usually requires a secondary consultation with radiologists in a different facility. This wastes time and money, and results in potentially unnecessary exposure to radiation.

Accuracy is the most common reason for referral for guided injections. The guidance can help avoid nerves, vessels, and other sensitive tissues. However, accuracy is also important to make sure the injection is placed in the correct location. When injections are placed into a muscle, tendon, or ligament, it causes significant pain; however, injections placed into a bursal space or joint do not cause pain. Numerous studies have shown that even in the hands of experts, “simple” injections can still miss their mark over 30% of the time.12-19 Therefore, if a patient experiences pain during a bursal space or joint injection, the injection was not placed properly.

The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine Position Paper on MSK ultrasound is based on a systematic review of the literature, including 124 studies. It states that ultrasound-guided joint injections (USGI) are more accurate and efficacious than landmark guided injections (LMGI), with a strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT) evidence rating of A and B, respectively.19 In terms of patient satisfaction, in a randomized controlled trial of 148 patients undergoing knee injections, Sibbitt and colleagues20 showed that USGI had a 48% reduction (P < .001) in procedural pain, a 58.5% reduction (P < .001) in absolute pain scores at the 2-week outcome mark, and a 75% reduction (P < .001) in significant pain and 62% reduction in nonresponder rate.20 From a financial point of view, Sibbitt and colleagues20 also demonstrated a 13% reduction in cost per patient per year, and a 58% reduction in cost per responder per year for a hospital outpatient center (P < .001).

Coding

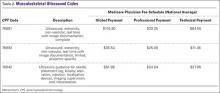

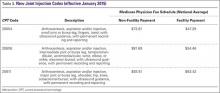

Coding for diagnostic MSK ultrasound requires an understanding of a few current procedural terminology (CPT) codes (Table 2). Ultrasound usage should follow the usual requirements of medical necessity and the CPT code selected should be based on the elements of the study performed. A complete examination, described by CPT code 76881, includes the examination and documentation of the muscles, tendons, joint, and other soft tissue structures and any identifiable abnormality of the joint being evaluated. If anything less is done, then the CPT code 76882 should be used.

New CPT codes for joint injections became effective January 2015 (Table 3). The new changes affect only the joint injection series (20600-20610). Previously, injections could be billed with CPT code 76942, which was “Ultrasonic guidance for needle placement (eg, biopsy, aspiration, injection, localization device), imaging supervision and interpretation.” This code can still be used, but with only specific injections, when the verbiage “with ultrasound/image guidance” is not included in the injection CPT code descriptor (Table 4).

Under the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI), which sets Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) payment policy as well as that of many private payers, one unit of service is allowed for CPT code 76942 in a single patient encounter regardless of the number of needle placements performed. Per NCCI, “The unit of service for these codes is the patient encounter, not number of lesions, number of aspirations, number of biopsies, number of injections, or number of localizations.”

Per the Radiology section of the NCCI, “Ultrasound guidance and diagnostic ultrasound (echography) procedures may be reported separately only if each service is distinct and separate. If a diagnostic ultrasound study identifies a previously unknown abnormality that requires a therapeutic procedure with ultrasound guidance at the same patient encounter, both the diagnostic ultrasound and ultrasound guidance procedure codes may be reported separately. However, a previously unknown abnormality identified during ultrasound guidance for a procedure should not be reported separately as a diagnostic ultrasound procedure.”

Under the Medicare program, the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) code selected should be based on the test results, with 2 exceptions. If the test does not yield a diagnosis or was normal, the physician should use the pre-service signs, symptoms, and conditions that prompted the study. If the test is a screening examination ordered in the absence of any signs or symptoms of illness or injury, the physician should select “screening” as the primary reason for the service and record the test results, if any, as additional diagnoses.

Modifiers must be used in specific settings. In the office, physicians who own the equipment and perform the service themselves (or the service is performed by an employed or contracted sonographer) may bill the global fee without any modifiers. However, if billing for a procedure on the same day as an office visit, the -25 modifier must be used. This indicates “[a] significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service.” This modifier should not be used routinely. If the service is performed in a hospital, the -26 modifier must be used to indicate that the professional service only was provided when the physician does not own the machine (Tables 2, 3, 4). The payers will not reimburse physicians for the technical component in the hospital setting.

Reimbursement

In general, medical insurance plans will cover ultrasound studies when they are medically indicated. However, we recommend checking with each individual private payer directly, including Medicare. Medicare Part B will generally reimburse physicians for medically necessary diagnostic ultrasound services, provided the services are within the scope of the physician’s license. Some Medicare contractors require that the physician who performs and/or interprets some types of ultrasound examinations be capable of demonstrating relevant, documented training through recent residency training or post-graduate continuing medical education (CME) and experience. Medicare does not differentiate by medical specialty with respect to billing medically necessary diagnostic ultrasound services, provided the services are within the scope of the physician’s license. Some Medicare contractors have coverage policies regarding either the diagnostic study or ultrasound guidance of certain injections, or both.

Payment policies for beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part C, known as the Medicare Advantage plans, will reflect those of the private insurance administrator. The Medicare Advantage plan may be either a health maintenance organization (HMO) or a preferred provider organization (PPO). Private insurance payment rules vary by payer and plan with respect to which specialties may perform and receive reimbursement for ultrasound services. Some payers will reimburse providers of any specialty for ultrasound services, while others may restrict imaging procedures to specific specialties or providers possessing specific certifications or accreditations. Some insurers require physicians to submit applications requesting ultrasound be added to their list of services performed in their practice. Physicians should contact private payers before submitting claims to determine their requirements and request that they add ultrasound to the list of services.

When contacting the private payers, ask the following questions:

- What do I need to do to have ultrasound added to my practice’s contract or list of services?

- Are there any specific training requirements that I must meet or credentials that I must obtain in order to be privileged to perform ultrasound in my office?

- Do I need to send a letter or can I submit the request verbally?

- Is there an application that must be completed?

- If there is a privileging program, how long will it take after submission of the application before we are accepted?

- What is the fee schedule associated with these codes?

- Are there any bundling edits in place covering any of the services I am considering performing? (Be prepared to provide the codes for any non-ultrasound services you will be performing in conjunction with the ultrasound services.)

- Are there any preauthorization requirements for specific ultrasound studies?

- Are there any preauthorization requirements for specific ultrasound studies?

Documentation Requirements

All diagnostic ultrasound examinations, including those when ultrasound is used to guide a procedure, require that permanently recorded images be maintained in the patient record. The images can be kept in the patient record or some other archive—they do not need to be submitted with the claim. Images can be stored as printed images, on a tape or electronic medium. Documentation of the study must be available to the insurer upon request.

A written report of all ultrasound studies should be maintained in the patient’s record. In the case of ultrasound guidance, the written report may be filed as a separate item in the patient’s record or it may be included within the report of the procedure for which the guidance is utilized.

As examples of our documentation in the office, copies of 3 of our standard forms are available: “Ultrasound report of the shoulder” (Appendix 1), “Procedure note for an ultrasound-guided injection of cortisone” (Appendix 2), and “Procedure note for an ultrasound-guided injection of platelet-rich plasma” (Appendix 3).

Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC)

The Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 was an effort to help reduce unnecessary imaging services and reduce costs; the Secretary of Health and Human Services was to establish a program to promote the use of “appropriate use criteria” (AUC) for advanced imaging services such as MRI, computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and nuclear cardiology. AUC are criteria that are developed or endorsed by national professional medical specialty societies or other provider-led entities to assist ordering professionals and furnishing professionals in making the most appropriate treatment decision for a specific clinical condition for an individual. The law also noted that the criteria should be evidence-based, meaning they should have stakeholder consensus, be scientifically valid, and be based on studies that are published and reviewable by stakeholders.

By April 2016, the Secretary will identify and publish the list of qualified clinical decision support mechanisms, which are tools that could be used by ordering professionals to ensure that AUC is met for applicable imaging services. These may include certified health electronic record technology, private sector clinical decision support mechanisms, and others. Actual use of the AUC will begin in January 2017. This legislation applies only to Medicare services, but other payers have cited concerns and may follow in the future.

Conclusion

Ultrasound is being increasingly used in varying specialties, especially orthopedic surgery. It provides a time- and cost-efficient modality with diagnostic power comparable to MRI. Portability and a high safety profile allows for ease of implementation as an in-office or sideline tool. Needle guidance and other intraoperative applications highlight its versatility as an adjunct to orthopedic treatments. This article provides a comprehensive guide to billing and coding for both diagnostic and therapeutic MSK ultrasound of the shoulder. Providers should stay up to date with upcoming appropriate use criteria and adjustments to current billing procedures.

1. Sivan M, Brown J, Brennan S, Bhakta B. A one-stop approach to the management of soft tissue and degenerative musculoskeletal conditions using clinic-based ultrasonography. Musculoskeletal Care. 2011;9(2):63-68.

2. Sharpe R, Nazarian L, Parker L, Rao V, Levin D. Dramatically increased musculoskeletal ultrasound utilization from 2000 to 2009, especially by podiatrists in private offices. Department of Radiology Faculty Papers. Paper 16. http://jdc.jefferson.edu/radiologyfp/16. Accessed January 7, 2016.

3. Blankstein A. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of clinical orthopedics: The orthopedic stethoscope. World J Orthop. 2011;2(2):13-24.

4. Sinha TP, Bhoi S, Kumar S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of bedside emergency ultrasound screening for fractures in pediatric trauma patients. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4(4);443-445.