User login

Gene variants linked to drug intolerance

Photo courtesy of the CDC

New research has revealed inherited genetic variations that may predispose patients to severe toxicity from thiopurines, a class of medications used as anticancer and immunosuppressive drugs.

Investigators identified 4 variations in the NUDT15 gene that alter thiopurine metabolism, leaving patients particularly sensitive to the drugs and at risk for toxicity.

One in 3 Japanese patients in this study carried the variations.

And evidence suggests the variations are common in other populations across Asia and in individuals of Hispanic ethnicity.

Jun J. Yang, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Genetics.

In 2015, Dr Yang and his colleagues published evidence linking a NUDT15 variant to reduced tolerance of mercaptopurine and reported the variant was more common in patients of East Asian ancestry.

With the current study, the investigators identified 3 additional NUDT15 variants and found that all 4 variants—p.Arg139Cys, p.Arg139His, p.Val18Ile, and p.Val18_Val19insGlyVal—were associated with lower levels of enzymatic activity and imbalance of thiopurine metabolism.

In a group of 270 children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the variants caused a 74.4% to 100% loss of NUDT15 function. They also predicted enzyme activity and mercaptopurine tolerance. In Singapore and Japan, for example, patients with the 2 highest risk variants had the lowest level of enzyme activity.

“These patients had excessive levels of the active drug metabolites per mercaptopurine dose, which suggests we may reduce the drug dose to achieve the level necessary to kill leukemia cells without causing toxicity,” Dr Yang said, adding that the NUDT15 variants have no other known health consequences.

The investigators also checked leukemic cells from 285 children newly diagnosed with ALL and found that patients with NUDT15 variants were more sensitive to thiopurines.

“That suggests we can screen for NUDT15 variants and potentially plan mercaptopurine doses according to each patient’s genotype before the therapy starts,” Dr Yang said. “This way, we hope to avoid toxicity without compromising treatment effectiveness.”

The investigators noted that future studies are needed to determine optimal thiopurine doses for patients with different NUDT15 variants.

Meanwhile, the search continues for variants in NUDT15 or other genes that influence chemotherapy effectiveness and safety. The NUDT15 variants and previously identified TPMT variants could not fully explain why Guatemalan patients in this study tolerated the lowest doses of mercaptopurine. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

New research has revealed inherited genetic variations that may predispose patients to severe toxicity from thiopurines, a class of medications used as anticancer and immunosuppressive drugs.

Investigators identified 4 variations in the NUDT15 gene that alter thiopurine metabolism, leaving patients particularly sensitive to the drugs and at risk for toxicity.

One in 3 Japanese patients in this study carried the variations.

And evidence suggests the variations are common in other populations across Asia and in individuals of Hispanic ethnicity.

Jun J. Yang, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Genetics.

In 2015, Dr Yang and his colleagues published evidence linking a NUDT15 variant to reduced tolerance of mercaptopurine and reported the variant was more common in patients of East Asian ancestry.

With the current study, the investigators identified 3 additional NUDT15 variants and found that all 4 variants—p.Arg139Cys, p.Arg139His, p.Val18Ile, and p.Val18_Val19insGlyVal—were associated with lower levels of enzymatic activity and imbalance of thiopurine metabolism.

In a group of 270 children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the variants caused a 74.4% to 100% loss of NUDT15 function. They also predicted enzyme activity and mercaptopurine tolerance. In Singapore and Japan, for example, patients with the 2 highest risk variants had the lowest level of enzyme activity.

“These patients had excessive levels of the active drug metabolites per mercaptopurine dose, which suggests we may reduce the drug dose to achieve the level necessary to kill leukemia cells without causing toxicity,” Dr Yang said, adding that the NUDT15 variants have no other known health consequences.

The investigators also checked leukemic cells from 285 children newly diagnosed with ALL and found that patients with NUDT15 variants were more sensitive to thiopurines.

“That suggests we can screen for NUDT15 variants and potentially plan mercaptopurine doses according to each patient’s genotype before the therapy starts,” Dr Yang said. “This way, we hope to avoid toxicity without compromising treatment effectiveness.”

The investigators noted that future studies are needed to determine optimal thiopurine doses for patients with different NUDT15 variants.

Meanwhile, the search continues for variants in NUDT15 or other genes that influence chemotherapy effectiveness and safety. The NUDT15 variants and previously identified TPMT variants could not fully explain why Guatemalan patients in this study tolerated the lowest doses of mercaptopurine. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

New research has revealed inherited genetic variations that may predispose patients to severe toxicity from thiopurines, a class of medications used as anticancer and immunosuppressive drugs.

Investigators identified 4 variations in the NUDT15 gene that alter thiopurine metabolism, leaving patients particularly sensitive to the drugs and at risk for toxicity.

One in 3 Japanese patients in this study carried the variations.

And evidence suggests the variations are common in other populations across Asia and in individuals of Hispanic ethnicity.

Jun J. Yang, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Genetics.

In 2015, Dr Yang and his colleagues published evidence linking a NUDT15 variant to reduced tolerance of mercaptopurine and reported the variant was more common in patients of East Asian ancestry.

With the current study, the investigators identified 3 additional NUDT15 variants and found that all 4 variants—p.Arg139Cys, p.Arg139His, p.Val18Ile, and p.Val18_Val19insGlyVal—were associated with lower levels of enzymatic activity and imbalance of thiopurine metabolism.

In a group of 270 children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the variants caused a 74.4% to 100% loss of NUDT15 function. They also predicted enzyme activity and mercaptopurine tolerance. In Singapore and Japan, for example, patients with the 2 highest risk variants had the lowest level of enzyme activity.

“These patients had excessive levels of the active drug metabolites per mercaptopurine dose, which suggests we may reduce the drug dose to achieve the level necessary to kill leukemia cells without causing toxicity,” Dr Yang said, adding that the NUDT15 variants have no other known health consequences.

The investigators also checked leukemic cells from 285 children newly diagnosed with ALL and found that patients with NUDT15 variants were more sensitive to thiopurines.

“That suggests we can screen for NUDT15 variants and potentially plan mercaptopurine doses according to each patient’s genotype before the therapy starts,” Dr Yang said. “This way, we hope to avoid toxicity without compromising treatment effectiveness.”

The investigators noted that future studies are needed to determine optimal thiopurine doses for patients with different NUDT15 variants.

Meanwhile, the search continues for variants in NUDT15 or other genes that influence chemotherapy effectiveness and safety. The NUDT15 variants and previously identified TPMT variants could not fully explain why Guatemalan patients in this study tolerated the lowest doses of mercaptopurine. ![]()

The Clinical Learning Environment Review as a Model for Impactful Self-directed Quality Control Initiatives in Clinical Practice

As part of its Next Accreditation System, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has introduced the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program, designed to assess the learning environment of institutions that have ACGME residency and fellowship programs.1 The CLER program emphasizes the responsibility of these hospitals, multispecialty groups, and other organizations to focus on quality and safety in the health care environment of resident learning and patient care. The expectation is that emphasis on quality of care in a residency training program will influence these physicians’ approach to quality of care after graduation.2,3 The Department of Dermatology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC)(Jackson, Mississippi) saw CLER as an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in the patient safety movement.

CLER Program at UMMC

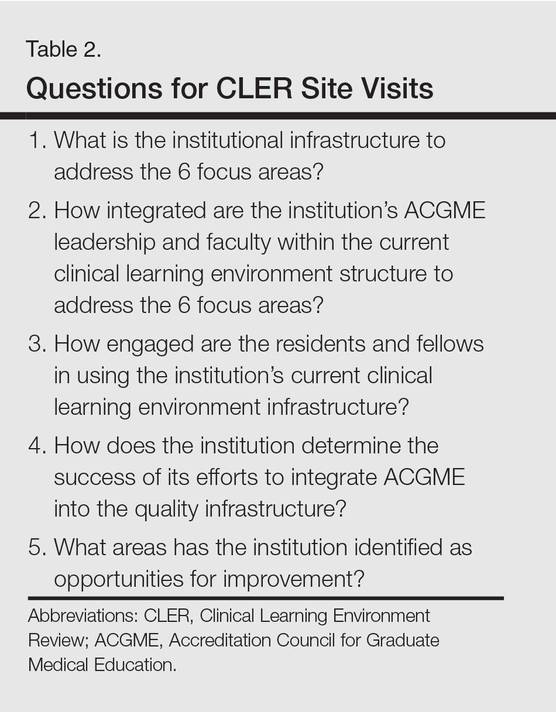

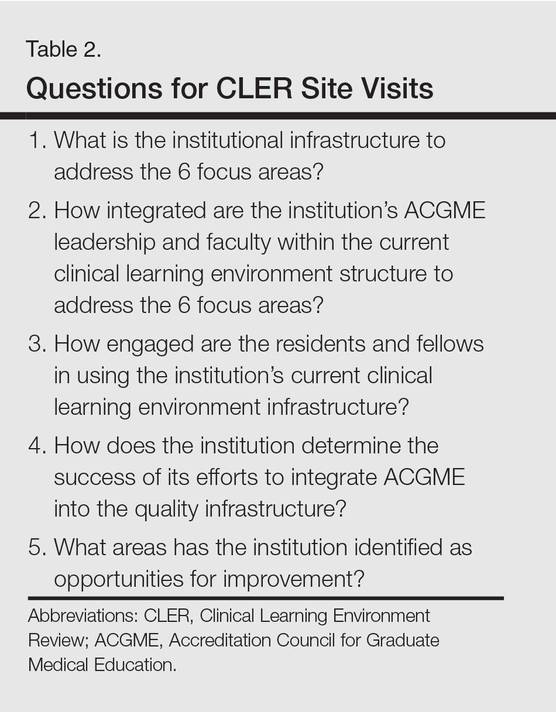

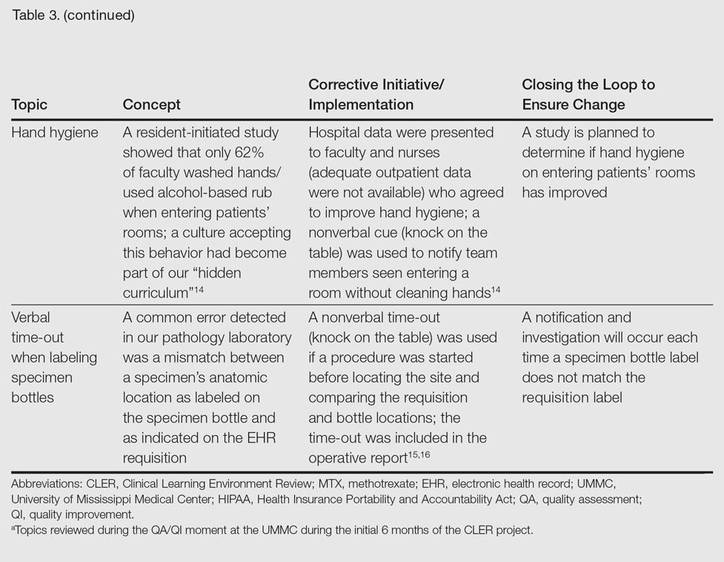

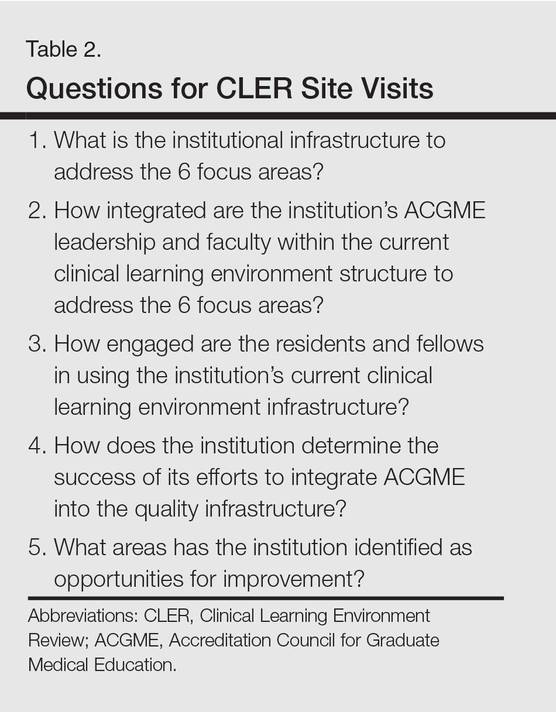

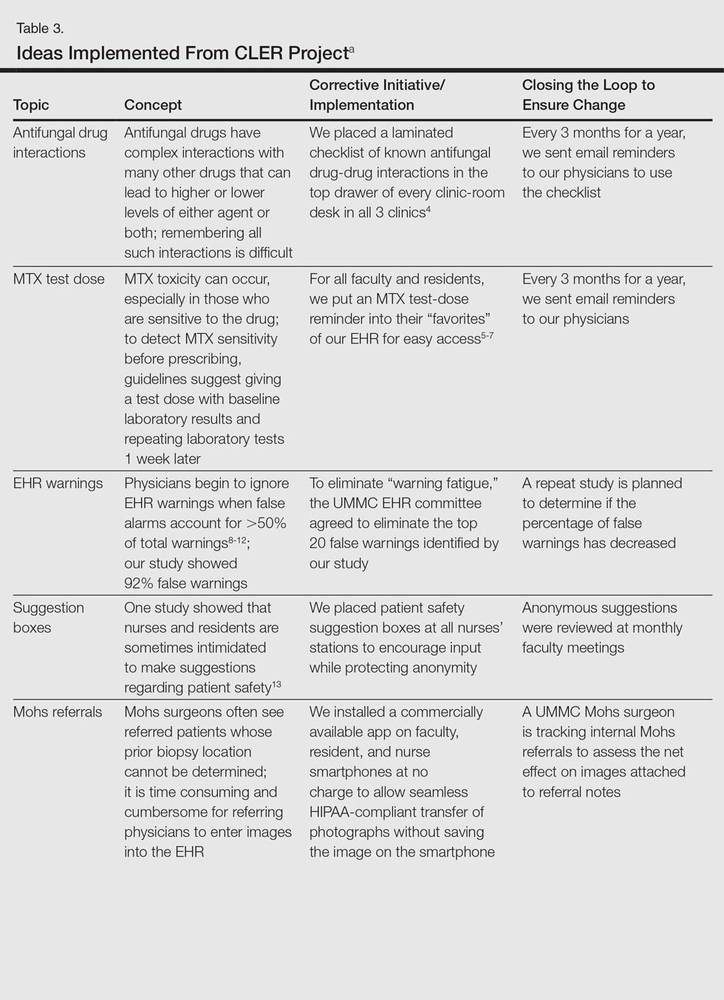

As a model CLER program at our institution, our project at the outset concentrated resident efforts on the focus areas specified by the ACGME (Table 1). We also were aware that our ACGME committee would need to answer questions during CLER site visits (Table 2). Because the data generated would not be used for accreditation decisions, there was no concern that exposing errors would jeopardize our postgraduate training certification.

The first 15 minutes of monthly faculty meetings were devoted to the presentation of a resident project, called a QA/QI (quality assurance/quality improvement) moment, that addressed ACGME focus areas 1, 2, 3, or 6 (Table 1). (Transitions in care [focus area 4] and work hours and fatigue [focus area 5] generally are less important issues in a predominantly outpatient specialty such as dermatology.) The residents were encouraged to identify areas where patient harm could occur due to poorly designed systems and to report situations in which patients actually were harmed.

Each project had to be approved by the department chairperson based on the following 4 requirements: First, the initiative must have the potential to notably impact patient safety and reduce harm. Second, residents with faculty support had to design methods to assess the identified problem. Third, participants had to design (to the best of their abilities) cost-effective and achievable interventions in a manner that would not produce unintended consequences. Fourth, residents were asked to devise a system to close the loop, ensuring that the effort put into the process was not wasted.

Findings From the CLER Program

The CLER program generates data on program and institutional attributes that have a salutatory effect on quality and safety, specifically involving 6 focus areas highlighted in Table 1. Putting residents at the center of efforts to improve the quality of care in our department proved critical to improving patient safety.

Involving residents in a series of QA/QI initiatives was logical because they rotate with faculty members. They also are in a position to view inconsistencies and to work to establish consistent patterns of patient care. In addition, our busy faculty members are charged with a variety of other clinical, educational, and administrative duties complicated by requirements in the design of a new residency training program. Faculty and residents working together were able to find problem areas in our department and devise solutions to improve those problems.

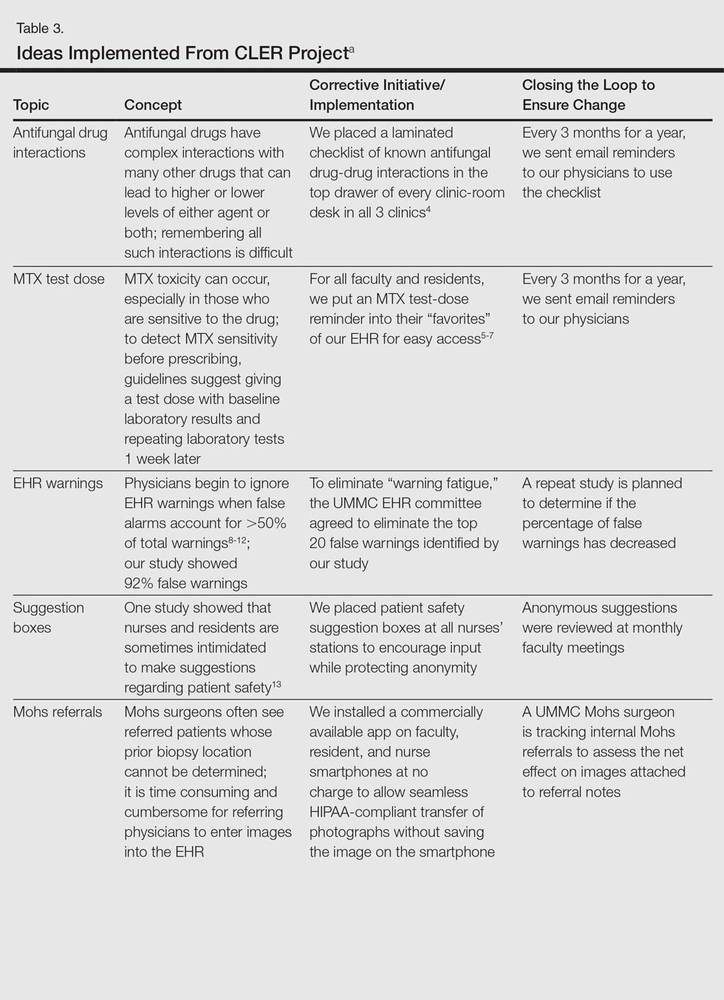

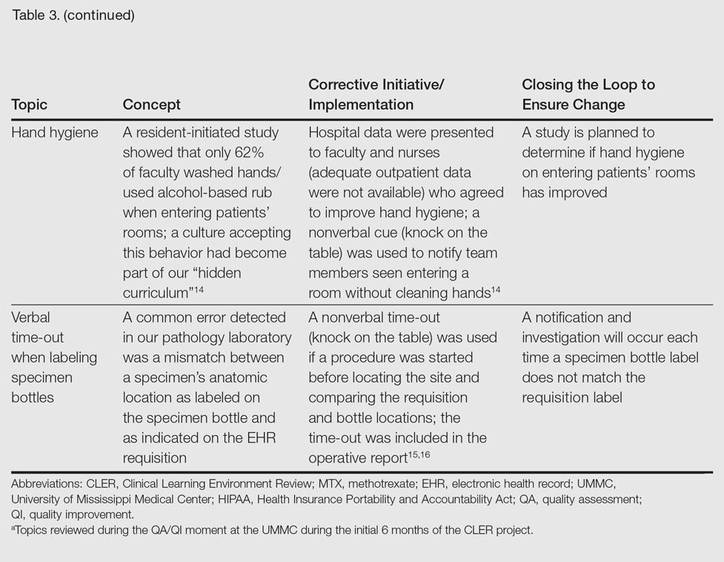

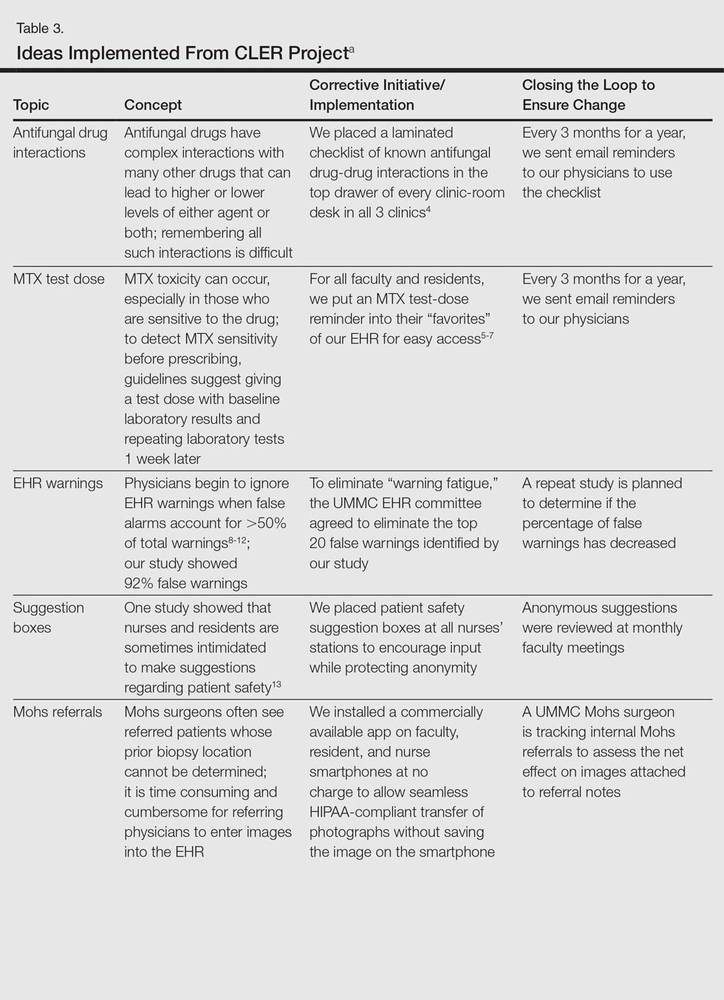

The CLER program involved a series of steps. Residents were charged with identifying errors (QA) and then devising a system to prevent similar errors from being repeated (QI)(Table 3). Efforts focused on preventing needless harm in our department. Initiatives developed by residents, who are closest to patients, have advantages over safety programs developed by the hospital’s administration. Residents became passionate about error prevention when they determined that their efforts could make a difference to patients.

Forward Thinking for Dermatology Practices

Perhaps there are lessons here that could apply to safety promotion in the practicing dermatologist’s office. The American Board of Dermatology, within the framework established by the American Board of Medical Specialties, requires physicians seeking recertification to participate in preapproved practice assessment QI exercises twice every 10 years.17 Six programs sponsored by the American Academy of Dermatology have now been approved in the areas of melanoma, biopsy follow-up measure, psoriasis, chronic urticaria, venous insufficiency, and laser- and light-based therapy for rejuvenation.18 An additional program has been approved for dermatopathologists through the American Society of Dermatopathology.19 None of these programs match the topics chosen by our residents in consultation with faculty to meet safety gaps identified in clinics at UMMC. Perhaps the next generation of performance improvement continuing medical education programs could include a pilot program for part 4 of Maintenance of Certification credit that is nonpunitive, patient focused, and allows dermatologists to design specific error-prevention solutions tailored to their individual practice in the same way residency programs are taking up this task.

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, et al. The Next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051-1056.

- Philibert I, Gonzalez del Rey JA, Lannon C, et al. Quality improvement skills for pediatric residents: from lecture to implementation and sustainability. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:40-46.

- Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, et al. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89:460-468.

- Brodell RT, Elewski B. Antifungal drug interactions. avoidance requires more than memorization. Postgrad Med. 2000;107:41-43.

- Kerr IG, Jolivet J, Collin JM, et al. Test dose for predicting high-dose methotrexate infusions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:44-51.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:451-485.

- Saporito FC, Menter MA. Methotrexate and psoriasis in the era of new biologic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:301-309.

- Van Der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, et al. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138-147.

- Hunter KM. Implementation of an electronic medication administration record and bedside verification system. Online J Nurs Inform (OJNI). 2011;15:672.

- Nanji KC, Slight SP, Seger DL, et al. Overrides of medication-related clinical decision support alerts in outpatients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:487-491.

- Schedlbauer A, Prasad V, Mulvaney C, et al. What evidence supports the use of computerized alerts and prompts to improve clinicians’ prescribing behavior? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:531-538.

- Lee EK, Mejia AF, Senior T, et al. Improving patient safety through medical alert management: an automated decision tool to reduce alert fatigue. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:417-421.

- Brenner AB. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J Ky Med Assoc. 2007;105:165-169.

- Rush JL, Flowers RH, Casamiquela KM, et al. Research letter: the knock: an adjunct to education opening the door to improved outpatient hand hygiene. J Am Acad Dermatol. In press.

- Lee SL. The extended surgical time-out: does it improve quality and prevent wrong-site surgery? Perm J. 2010;14:19-23.

- Altpeter T, Luckhardt K, Lewis JN, et al. Expanded surgical time out: a key to real-time data collection and quality improvement. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:527-532.

- MOC requirements. American Board of Dermatology Web site. https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/moc-requirements.aspx#PI. Accessed January 18, 2016.

- How AAD develops measures. American Academy of Dermatology Web site. https://www.aad.org/practice-tools/quality-care/quality-measures. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Quality assurance programs. The American Society of Dermatopathology Web site. http://www.asdp.org/education/quality-assurance-programs. Accessed January 20, 2016.

As part of its Next Accreditation System, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has introduced the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program, designed to assess the learning environment of institutions that have ACGME residency and fellowship programs.1 The CLER program emphasizes the responsibility of these hospitals, multispecialty groups, and other organizations to focus on quality and safety in the health care environment of resident learning and patient care. The expectation is that emphasis on quality of care in a residency training program will influence these physicians’ approach to quality of care after graduation.2,3 The Department of Dermatology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC)(Jackson, Mississippi) saw CLER as an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in the patient safety movement.

CLER Program at UMMC

As a model CLER program at our institution, our project at the outset concentrated resident efforts on the focus areas specified by the ACGME (Table 1). We also were aware that our ACGME committee would need to answer questions during CLER site visits (Table 2). Because the data generated would not be used for accreditation decisions, there was no concern that exposing errors would jeopardize our postgraduate training certification.

The first 15 minutes of monthly faculty meetings were devoted to the presentation of a resident project, called a QA/QI (quality assurance/quality improvement) moment, that addressed ACGME focus areas 1, 2, 3, or 6 (Table 1). (Transitions in care [focus area 4] and work hours and fatigue [focus area 5] generally are less important issues in a predominantly outpatient specialty such as dermatology.) The residents were encouraged to identify areas where patient harm could occur due to poorly designed systems and to report situations in which patients actually were harmed.

Each project had to be approved by the department chairperson based on the following 4 requirements: First, the initiative must have the potential to notably impact patient safety and reduce harm. Second, residents with faculty support had to design methods to assess the identified problem. Third, participants had to design (to the best of their abilities) cost-effective and achievable interventions in a manner that would not produce unintended consequences. Fourth, residents were asked to devise a system to close the loop, ensuring that the effort put into the process was not wasted.

Findings From the CLER Program

The CLER program generates data on program and institutional attributes that have a salutatory effect on quality and safety, specifically involving 6 focus areas highlighted in Table 1. Putting residents at the center of efforts to improve the quality of care in our department proved critical to improving patient safety.

Involving residents in a series of QA/QI initiatives was logical because they rotate with faculty members. They also are in a position to view inconsistencies and to work to establish consistent patterns of patient care. In addition, our busy faculty members are charged with a variety of other clinical, educational, and administrative duties complicated by requirements in the design of a new residency training program. Faculty and residents working together were able to find problem areas in our department and devise solutions to improve those problems.

The CLER program involved a series of steps. Residents were charged with identifying errors (QA) and then devising a system to prevent similar errors from being repeated (QI)(Table 3). Efforts focused on preventing needless harm in our department. Initiatives developed by residents, who are closest to patients, have advantages over safety programs developed by the hospital’s administration. Residents became passionate about error prevention when they determined that their efforts could make a difference to patients.

Forward Thinking for Dermatology Practices

Perhaps there are lessons here that could apply to safety promotion in the practicing dermatologist’s office. The American Board of Dermatology, within the framework established by the American Board of Medical Specialties, requires physicians seeking recertification to participate in preapproved practice assessment QI exercises twice every 10 years.17 Six programs sponsored by the American Academy of Dermatology have now been approved in the areas of melanoma, biopsy follow-up measure, psoriasis, chronic urticaria, venous insufficiency, and laser- and light-based therapy for rejuvenation.18 An additional program has been approved for dermatopathologists through the American Society of Dermatopathology.19 None of these programs match the topics chosen by our residents in consultation with faculty to meet safety gaps identified in clinics at UMMC. Perhaps the next generation of performance improvement continuing medical education programs could include a pilot program for part 4 of Maintenance of Certification credit that is nonpunitive, patient focused, and allows dermatologists to design specific error-prevention solutions tailored to their individual practice in the same way residency programs are taking up this task.

As part of its Next Accreditation System, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has introduced the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program, designed to assess the learning environment of institutions that have ACGME residency and fellowship programs.1 The CLER program emphasizes the responsibility of these hospitals, multispecialty groups, and other organizations to focus on quality and safety in the health care environment of resident learning and patient care. The expectation is that emphasis on quality of care in a residency training program will influence these physicians’ approach to quality of care after graduation.2,3 The Department of Dermatology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC)(Jackson, Mississippi) saw CLER as an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in the patient safety movement.

CLER Program at UMMC

As a model CLER program at our institution, our project at the outset concentrated resident efforts on the focus areas specified by the ACGME (Table 1). We also were aware that our ACGME committee would need to answer questions during CLER site visits (Table 2). Because the data generated would not be used for accreditation decisions, there was no concern that exposing errors would jeopardize our postgraduate training certification.

The first 15 minutes of monthly faculty meetings were devoted to the presentation of a resident project, called a QA/QI (quality assurance/quality improvement) moment, that addressed ACGME focus areas 1, 2, 3, or 6 (Table 1). (Transitions in care [focus area 4] and work hours and fatigue [focus area 5] generally are less important issues in a predominantly outpatient specialty such as dermatology.) The residents were encouraged to identify areas where patient harm could occur due to poorly designed systems and to report situations in which patients actually were harmed.

Each project had to be approved by the department chairperson based on the following 4 requirements: First, the initiative must have the potential to notably impact patient safety and reduce harm. Second, residents with faculty support had to design methods to assess the identified problem. Third, participants had to design (to the best of their abilities) cost-effective and achievable interventions in a manner that would not produce unintended consequences. Fourth, residents were asked to devise a system to close the loop, ensuring that the effort put into the process was not wasted.

Findings From the CLER Program

The CLER program generates data on program and institutional attributes that have a salutatory effect on quality and safety, specifically involving 6 focus areas highlighted in Table 1. Putting residents at the center of efforts to improve the quality of care in our department proved critical to improving patient safety.

Involving residents in a series of QA/QI initiatives was logical because they rotate with faculty members. They also are in a position to view inconsistencies and to work to establish consistent patterns of patient care. In addition, our busy faculty members are charged with a variety of other clinical, educational, and administrative duties complicated by requirements in the design of a new residency training program. Faculty and residents working together were able to find problem areas in our department and devise solutions to improve those problems.

The CLER program involved a series of steps. Residents were charged with identifying errors (QA) and then devising a system to prevent similar errors from being repeated (QI)(Table 3). Efforts focused on preventing needless harm in our department. Initiatives developed by residents, who are closest to patients, have advantages over safety programs developed by the hospital’s administration. Residents became passionate about error prevention when they determined that their efforts could make a difference to patients.

Forward Thinking for Dermatology Practices

Perhaps there are lessons here that could apply to safety promotion in the practicing dermatologist’s office. The American Board of Dermatology, within the framework established by the American Board of Medical Specialties, requires physicians seeking recertification to participate in preapproved practice assessment QI exercises twice every 10 years.17 Six programs sponsored by the American Academy of Dermatology have now been approved in the areas of melanoma, biopsy follow-up measure, psoriasis, chronic urticaria, venous insufficiency, and laser- and light-based therapy for rejuvenation.18 An additional program has been approved for dermatopathologists through the American Society of Dermatopathology.19 None of these programs match the topics chosen by our residents in consultation with faculty to meet safety gaps identified in clinics at UMMC. Perhaps the next generation of performance improvement continuing medical education programs could include a pilot program for part 4 of Maintenance of Certification credit that is nonpunitive, patient focused, and allows dermatologists to design specific error-prevention solutions tailored to their individual practice in the same way residency programs are taking up this task.

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, et al. The Next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051-1056.

- Philibert I, Gonzalez del Rey JA, Lannon C, et al. Quality improvement skills for pediatric residents: from lecture to implementation and sustainability. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:40-46.

- Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, et al. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89:460-468.

- Brodell RT, Elewski B. Antifungal drug interactions. avoidance requires more than memorization. Postgrad Med. 2000;107:41-43.

- Kerr IG, Jolivet J, Collin JM, et al. Test dose for predicting high-dose methotrexate infusions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:44-51.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:451-485.

- Saporito FC, Menter MA. Methotrexate and psoriasis in the era of new biologic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:301-309.

- Van Der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, et al. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138-147.

- Hunter KM. Implementation of an electronic medication administration record and bedside verification system. Online J Nurs Inform (OJNI). 2011;15:672.

- Nanji KC, Slight SP, Seger DL, et al. Overrides of medication-related clinical decision support alerts in outpatients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:487-491.

- Schedlbauer A, Prasad V, Mulvaney C, et al. What evidence supports the use of computerized alerts and prompts to improve clinicians’ prescribing behavior? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:531-538.

- Lee EK, Mejia AF, Senior T, et al. Improving patient safety through medical alert management: an automated decision tool to reduce alert fatigue. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:417-421.

- Brenner AB. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J Ky Med Assoc. 2007;105:165-169.

- Rush JL, Flowers RH, Casamiquela KM, et al. Research letter: the knock: an adjunct to education opening the door to improved outpatient hand hygiene. J Am Acad Dermatol. In press.

- Lee SL. The extended surgical time-out: does it improve quality and prevent wrong-site surgery? Perm J. 2010;14:19-23.

- Altpeter T, Luckhardt K, Lewis JN, et al. Expanded surgical time out: a key to real-time data collection and quality improvement. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:527-532.

- MOC requirements. American Board of Dermatology Web site. https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/moc-requirements.aspx#PI. Accessed January 18, 2016.

- How AAD develops measures. American Academy of Dermatology Web site. https://www.aad.org/practice-tools/quality-care/quality-measures. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Quality assurance programs. The American Society of Dermatopathology Web site. http://www.asdp.org/education/quality-assurance-programs. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, et al. The Next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051-1056.

- Philibert I, Gonzalez del Rey JA, Lannon C, et al. Quality improvement skills for pediatric residents: from lecture to implementation and sustainability. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:40-46.

- Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, et al. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89:460-468.

- Brodell RT, Elewski B. Antifungal drug interactions. avoidance requires more than memorization. Postgrad Med. 2000;107:41-43.

- Kerr IG, Jolivet J, Collin JM, et al. Test dose for predicting high-dose methotrexate infusions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:44-51.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:451-485.

- Saporito FC, Menter MA. Methotrexate and psoriasis in the era of new biologic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:301-309.

- Van Der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, et al. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138-147.

- Hunter KM. Implementation of an electronic medication administration record and bedside verification system. Online J Nurs Inform (OJNI). 2011;15:672.

- Nanji KC, Slight SP, Seger DL, et al. Overrides of medication-related clinical decision support alerts in outpatients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:487-491.

- Schedlbauer A, Prasad V, Mulvaney C, et al. What evidence supports the use of computerized alerts and prompts to improve clinicians’ prescribing behavior? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:531-538.

- Lee EK, Mejia AF, Senior T, et al. Improving patient safety through medical alert management: an automated decision tool to reduce alert fatigue. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:417-421.

- Brenner AB. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J Ky Med Assoc. 2007;105:165-169.

- Rush JL, Flowers RH, Casamiquela KM, et al. Research letter: the knock: an adjunct to education opening the door to improved outpatient hand hygiene. J Am Acad Dermatol. In press.

- Lee SL. The extended surgical time-out: does it improve quality and prevent wrong-site surgery? Perm J. 2010;14:19-23.

- Altpeter T, Luckhardt K, Lewis JN, et al. Expanded surgical time out: a key to real-time data collection and quality improvement. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:527-532.

- MOC requirements. American Board of Dermatology Web site. https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/moc-requirements.aspx#PI. Accessed January 18, 2016.

- How AAD develops measures. American Academy of Dermatology Web site. https://www.aad.org/practice-tools/quality-care/quality-measures. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Quality assurance programs. The American Society of Dermatopathology Web site. http://www.asdp.org/education/quality-assurance-programs. Accessed January 20, 2016.

Practice Points

- The Clinical Learning Environment Review mobilizes residency and fellowship training programs in the movement to improve the quality of patient care.

- Quality assessment/quality improvement (QA/QI) projects enhance communication between residents and faculty and promote systems that improve patient safety.

- Emphasis on resident-initiated QA/QI impacts quality of care in clinical practice long after graduation.

Electronic Assessment of Mental Status

Altered mental status (AMS) is a complex spectrum of cognitive deficits that includes orientation, memory, language, visuospatial ability, and perception.[1] The clinical definitions of both delirium and dementia include AMS as a hallmark clinical prerequisite. Regardless of etiology, this broader AMS definition is particularly salient in the hospital setting, where AMS is present in up to 60% of inpatients and is associated with longer hospital stay as well as increased morbidity and mortality.[2, 3] Not surprisingly, due to the complexity of identifying and assessing changes in mental status, clinically relevant AMS is often undetected among inpatients.[2] However, when detected, the most common causes of AMS (infection, polypharmacy, and pain) are treatable, suggesting that early AMS identification could alert clinicians to early signs of clinical decompensation, potentially improving clinical outcomes.[4]

Because rapid and systemic clinical detection of AMS is limited by the complexity of mental status, a number of assessments have been created, each with their own advantages, limitations, and target populations. These assessments are often limited by time‐intensive administration, subjectivity of mental status assessment, and lack of sensitivity in general medicine patients. Time‐intensive measures, such as the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) have utility in the research setting, whereas current common clinical risk stratification tools (eg, National Early Warning Score) utilize simpler measures such as the Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive (AVPU) and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) as measures of mental status.[2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

To address the need for a brief, clinically feasible, accurate tool in clinical detection of AMS, our group developed a mobile application for working memory testing, the Functional Assessment of Mentation (FAMTM). In this study, we aimed to identify baseline scoring distributions of the FAMTM in a nonhospitalized subgroup, as well as assess the correlation of the FAMTM to discharge disposition and compare it to the SPMSQ in inpatients.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a prospective observational study. Data were collected from both hospitalized and nonhospitalized adult participants as 2 distinct subgroups. Nonhospitalized adult subjects were recruited from a university medical campus (June 2013July 2013; IRB‐12‐0175). Hospitalized participants were recruited from the general medicine service as part of an ongoing study measuring quality of care and resource allocation at the same academic medical center (June 2014August 2014; IRB‐9967).[10]

FAMTM Application

The FAMTM application is a bedside tool for working memory assessment developed for the iPhone mobile operating system (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA) and presented on an iPad mini (Apple). The application interface displays 4 colored rectangles individually labeled with a number (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). The testing portion of the application presents a sequence of numbered rectangles, illuminated 1 at a time in random order. Subjects are prompted first to watch and remember the sequence and then repeat the sequence by touching the screen within each numbered rectangle. Successful reproduction of the sequence is followed by a distinct and longer sequence, whereas unsuccessful attempts are followed by a shorter sequence. The final FAMTM score corresponds to the longest sequence of rectangles successfully repeated by the subject.

Data Collection

In the nonhospitalized subject population, research assistants collected demographic data immediately prior to FAMTM administration. Among hospitalized subjects, GCS information was collected by nursing staff as part of standard clinical care. One research assistant administered the SPMSQ while a second assistant, blinded to the SPMSQ and GCS scores, administered the FAMTM. Clinical data were obtained from medical records (EPIC Systems Corp., Verona, WI). Discharge disposition was dichotomized as discharged home or not.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic characteristics of the 2 subject populations were compared using Student t tests (continuous variables) and 2 tests (categorical variables). Score distribution and discharge disposition comparison was conducted with the Mann‐Whitney U test and area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) analysis, using the trapezoidal rule.[11] Multivariable linear regression was used to investigate the impact of age, race, education, discharge disposition, and hospitalization status on patient scores and times. Correlations between the FAMTM and SPMSQ scores and between the GCS and SPMSQ scores were calculated using the Spearman rank test. Significance was set at a 2‐sided P value of 0.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 931 subjects were enrolled in the study. In the nonhospitalized subgroup, 651 consented to study participation and 612 were included in final analysis. Subjects were excluded if they started but did not complete the application (n = 36) or were under the age of 18 years (n = 3). Of the 363 hospitalized subjects approached for enrollment, 319 were included in the final analysis. Subjects were excluded if they refused to participate (n = 23), were under the age of 18 (n = 2), had technical failures (n = 5), or had physical or visual limitations that precluded them from participation (n = 14). Within the hospitalized subgroup, 268 subjects were discharged home (85%). The table displays demographics and score distributions by subgroup.1

| Nonhospitalized Subjects, n = 612 | Hospitalized Subjects Discharged Home, n = 268 | Hospitalized Subjects Discharged Elsewhere, n = 48 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 52 18 | 52 19 | 62 17 | 0.001 |

| Female sex | 343 (56%) | 158 (59%) | 26 (54%) | 0.63 |

| Education | 0.001 | |||

| Less than high school graduate | 31 (5%) | 32 (12%) | 7 (15%) | |

| High school graduate | 312 (51%) | 153 (57%) | 26 (54%) | |

| College graduate | 263 (43%) | 43 (16%) | 8 (17%) | |

| Missing | 6 (1%) | 40 (15%) | 7 (15%) | |

| Race | 0.001 | |||

| Black | 196 (32%) | 185 (69%) | 34 (71%) | |

| White | 324 (53%) | 75 (28%) | 13 (27%) | |

| Other | 86 (14%) | 4 (1%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Missing | 6 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| FAMTM score, median (IQR) | 5 (47) | 5 (36) | 3 (15) | 0.001 |

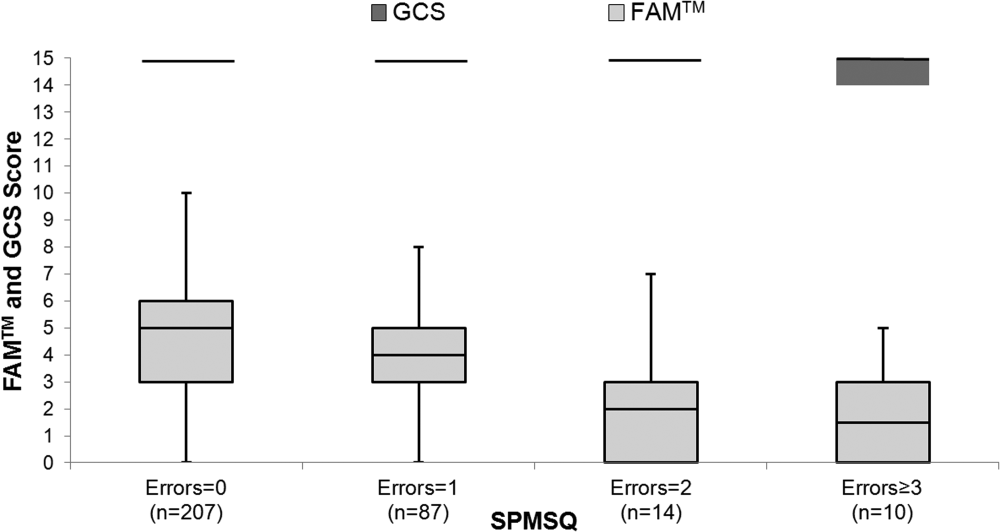

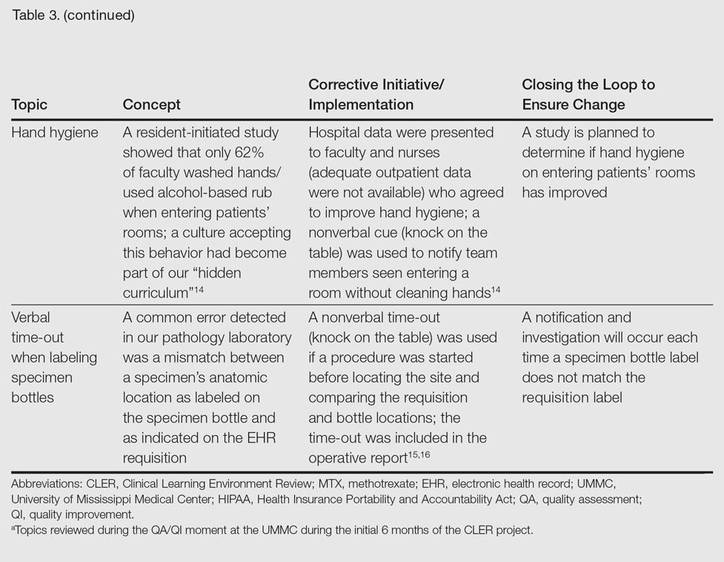

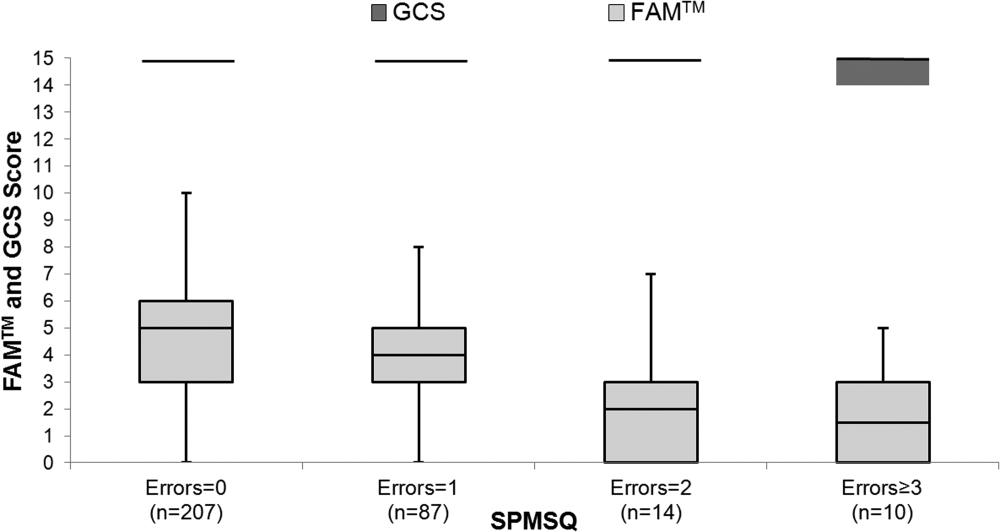

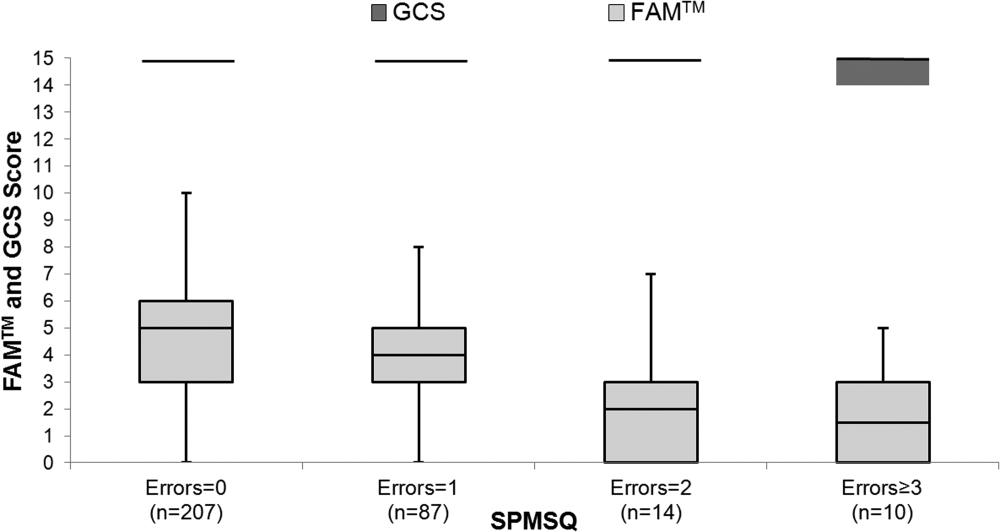

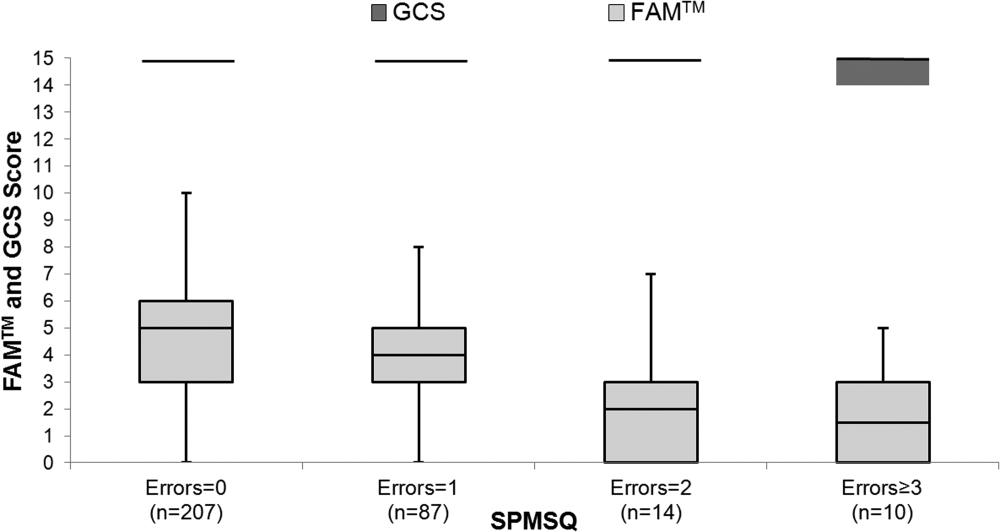

The median FAMTM score for the combined study population was 5 (interquartile range [IQR] 36), and median time to completion was 55 seconds (IQR 4567 seconds). A graded reduction was found in the FAMTM score for all stepwise comparisons between nonhospitalized subjects, hospitalized subjects discharged home, and hospitalized subjects not discharged home (median 5 [IQR 47] vs 5 [IQR 36] vs 3 [IQR 15]; P 0.001 for all pairwise comparisons). The AUC for the FAMTM predicting discharge disposition (home vs not) was 0.66 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.58‐0.74]. After adjusting for confounders, higher FAMTM scores were independently associated with not being hospitalized, being discharged home, higher levels of education, younger age, and white race (see Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article). Additionally, in the hospitalized subgroup, decreasing FAMTM score was significantly correlated with increasing errors on the SPMSQ (Spearman = 0.27, P 0.001), whereas the GCS score was not correlated with the SPMSQ (Spearman = 0.05, P = 0.40) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated the utility of a rapid and accurate mobile application for assessment of mental status. The FAMTM was able to be quickly administered with a median time to completion of approximately 1 minute. The ability to detect mild alterations in mental status was shown through concurrent validity by FAMTM correlation with the SPMSQ and predictive validity with the association between the FAMTM and discharge disposition. Our study highlights the potential for the FAMTM to be used as a sensitive marker of AMS.

The novel design of the FAMTM presents unique advantages compared to current mental status testing. First, the FAMTM could allow patients with hearing impairment or language barriers to complete a mental status assessment. Additionally, the approximately 1‐minute median time to completion is much faster than other established mental status assessments including the SPMSQ (510 minutes). Compared to the SPMSQ taking 5 minutes, in a 400‐bed hospital, taken once per nursing shift, the FAMTM would save approximately 20,000 hours and 10 nursing full‐time equivalents per year.[5] Finally, many current mental status tests such as the Confusion Assessment Model utilize subjective mental status assessments.[2] However, the FAMTM is designed to be conducted through self‐assessment and, thus, could theoretically be free of observer bias. This potential for self‐administration expands beyond other proposed alternative testing mechanisms of the AMS such as ultrabrief assessments that include items such as asking subjects the months of the year backwards, and what is the day of the week?, and assessing arousal.[12, 13, 14]

In research settings and commonly in hospitals, the GCS and AVPU are used clinically for mental status assessment of hospitalized patients.[6, 15] However, similar to previous literature, our study found that the vast majority of hospitalized patients were defined as neurologically intact by the GCS, which is the more accurate predictor of the 2.[7] One major strength of the FAMTM was that it identified an extensive gradation of scores for patients previously labeled as merely alert, providing greater resolution than the GCS in quantifying mental status.

One of the key benefits of the FAMTM is that it can be measured longitudinally over the course of a patient's hospital stay. Therefore, once a baseline FAMTM score is established, variation from the patient's personal baseline could indicate mental status deterioration, which would not be affected by the patient's demographics, health status, or underlying neurocognitive deficits.

There were important limitations to this study. First, limited generalizability of these data may exist due to the single‐center setting and patient population. However, this initial study provides pilot data for further expansion into the potential broad applicability of the FAMTM to other patient populations and settings. Additionally, the cost of large‐scale implementation of the FAMTM is unknown and was beyond the scope of this pilot study. However, to reduce costs, the FAMTM technology could be integrated into existing hospital technology infrastructure. Finally, the scope of this study prevented a complete assessment of all validity measures or comparison to other mental status assessments such as the digit span or serial sevens tests. However, predictive and concurrent validity were assessed with comparison by discharge disposition, SPMSQ, and GCS scores.

In conclusion, this pilot study identifies the FAMTM application as a potentially clinically useful, novel, rapid, and feasible assessment tool of mental status in a general medicine inpatient setting.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Frank Zadravecz, MPH, for his support with this project.

Disclosures: This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIA 2T35AG029795‐07) and in part by career development awards granted to Dr. Churpek, Dr. Edelson, and Dr. Press by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL121080, K23 HL097157, and K23 HL118151, respectively). Dr. Churpek has received honoraria from Chest for invited speaking engagements. Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending (ARCD. P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. In addition, Dr. Edelson has received research support from Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA), the American Heart Association (Dallas, TX), and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway). She has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, IL), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

- , . Altered mental status in older patients in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):101–136.

- , , , , , . Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948.

- , , , , . Association between clinically abnormal observations and subsequent in‐hospital mortality: a prospective study. Resuscitation. 2004;62(2):137–141.

- , , . Early recognition of delirium: review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(6):721–729.

- . A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433–441.

- , , , , . The ability of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) to discriminate patients at risk of early cardiac arrest, unanticipated intensive care unit admission, and death. Resuscitation. 2013;84(4):465–470.

- , , , et al. Comparison of mental‐status scales for predicting mortality on the general wards. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):658–663.

- , . Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. Lancet. 1974;304(7872):81–84.

- , , , . Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire as a Screening Test for Dementia and Delirium Among the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35(5):412–416.

- , , , et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874.

- , , . Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845.

- , , , et al. Preliminary development of an ultrabrief two‐item bedside test for delirium. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):645–650.

- , , , , , . The association between an ultrabrief cognitive screening in older adults and hospital outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):651–657.

- , , , et al. Selecting optimal screening items for delirium: an application of item response theory. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:8.

- , , . Variability in agreement between physicians and nurses when measuring the Glasgow Coma Scale in the emergency department limits its clinical usefulness. Emerg Med Australas. 2006;18(4):379–384.

Altered mental status (AMS) is a complex spectrum of cognitive deficits that includes orientation, memory, language, visuospatial ability, and perception.[1] The clinical definitions of both delirium and dementia include AMS as a hallmark clinical prerequisite. Regardless of etiology, this broader AMS definition is particularly salient in the hospital setting, where AMS is present in up to 60% of inpatients and is associated with longer hospital stay as well as increased morbidity and mortality.[2, 3] Not surprisingly, due to the complexity of identifying and assessing changes in mental status, clinically relevant AMS is often undetected among inpatients.[2] However, when detected, the most common causes of AMS (infection, polypharmacy, and pain) are treatable, suggesting that early AMS identification could alert clinicians to early signs of clinical decompensation, potentially improving clinical outcomes.[4]

Because rapid and systemic clinical detection of AMS is limited by the complexity of mental status, a number of assessments have been created, each with their own advantages, limitations, and target populations. These assessments are often limited by time‐intensive administration, subjectivity of mental status assessment, and lack of sensitivity in general medicine patients. Time‐intensive measures, such as the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) have utility in the research setting, whereas current common clinical risk stratification tools (eg, National Early Warning Score) utilize simpler measures such as the Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive (AVPU) and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) as measures of mental status.[2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

To address the need for a brief, clinically feasible, accurate tool in clinical detection of AMS, our group developed a mobile application for working memory testing, the Functional Assessment of Mentation (FAMTM). In this study, we aimed to identify baseline scoring distributions of the FAMTM in a nonhospitalized subgroup, as well as assess the correlation of the FAMTM to discharge disposition and compare it to the SPMSQ in inpatients.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a prospective observational study. Data were collected from both hospitalized and nonhospitalized adult participants as 2 distinct subgroups. Nonhospitalized adult subjects were recruited from a university medical campus (June 2013July 2013; IRB‐12‐0175). Hospitalized participants were recruited from the general medicine service as part of an ongoing study measuring quality of care and resource allocation at the same academic medical center (June 2014August 2014; IRB‐9967).[10]

FAMTM Application

The FAMTM application is a bedside tool for working memory assessment developed for the iPhone mobile operating system (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA) and presented on an iPad mini (Apple). The application interface displays 4 colored rectangles individually labeled with a number (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). The testing portion of the application presents a sequence of numbered rectangles, illuminated 1 at a time in random order. Subjects are prompted first to watch and remember the sequence and then repeat the sequence by touching the screen within each numbered rectangle. Successful reproduction of the sequence is followed by a distinct and longer sequence, whereas unsuccessful attempts are followed by a shorter sequence. The final FAMTM score corresponds to the longest sequence of rectangles successfully repeated by the subject.

Data Collection

In the nonhospitalized subject population, research assistants collected demographic data immediately prior to FAMTM administration. Among hospitalized subjects, GCS information was collected by nursing staff as part of standard clinical care. One research assistant administered the SPMSQ while a second assistant, blinded to the SPMSQ and GCS scores, administered the FAMTM. Clinical data were obtained from medical records (EPIC Systems Corp., Verona, WI). Discharge disposition was dichotomized as discharged home or not.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic characteristics of the 2 subject populations were compared using Student t tests (continuous variables) and 2 tests (categorical variables). Score distribution and discharge disposition comparison was conducted with the Mann‐Whitney U test and area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) analysis, using the trapezoidal rule.[11] Multivariable linear regression was used to investigate the impact of age, race, education, discharge disposition, and hospitalization status on patient scores and times. Correlations between the FAMTM and SPMSQ scores and between the GCS and SPMSQ scores were calculated using the Spearman rank test. Significance was set at a 2‐sided P value of 0.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 931 subjects were enrolled in the study. In the nonhospitalized subgroup, 651 consented to study participation and 612 were included in final analysis. Subjects were excluded if they started but did not complete the application (n = 36) or were under the age of 18 years (n = 3). Of the 363 hospitalized subjects approached for enrollment, 319 were included in the final analysis. Subjects were excluded if they refused to participate (n = 23), were under the age of 18 (n = 2), had technical failures (n = 5), or had physical or visual limitations that precluded them from participation (n = 14). Within the hospitalized subgroup, 268 subjects were discharged home (85%). The table displays demographics and score distributions by subgroup.1

| Nonhospitalized Subjects, n = 612 | Hospitalized Subjects Discharged Home, n = 268 | Hospitalized Subjects Discharged Elsewhere, n = 48 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 52 18 | 52 19 | 62 17 | 0.001 |

| Female sex | 343 (56%) | 158 (59%) | 26 (54%) | 0.63 |

| Education | 0.001 | |||

| Less than high school graduate | 31 (5%) | 32 (12%) | 7 (15%) | |

| High school graduate | 312 (51%) | 153 (57%) | 26 (54%) | |

| College graduate | 263 (43%) | 43 (16%) | 8 (17%) | |

| Missing | 6 (1%) | 40 (15%) | 7 (15%) | |

| Race | 0.001 | |||

| Black | 196 (32%) | 185 (69%) | 34 (71%) | |

| White | 324 (53%) | 75 (28%) | 13 (27%) | |

| Other | 86 (14%) | 4 (1%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Missing | 6 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| FAMTM score, median (IQR) | 5 (47) | 5 (36) | 3 (15) | 0.001 |

The median FAMTM score for the combined study population was 5 (interquartile range [IQR] 36), and median time to completion was 55 seconds (IQR 4567 seconds). A graded reduction was found in the FAMTM score for all stepwise comparisons between nonhospitalized subjects, hospitalized subjects discharged home, and hospitalized subjects not discharged home (median 5 [IQR 47] vs 5 [IQR 36] vs 3 [IQR 15]; P 0.001 for all pairwise comparisons). The AUC for the FAMTM predicting discharge disposition (home vs not) was 0.66 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.58‐0.74]. After adjusting for confounders, higher FAMTM scores were independently associated with not being hospitalized, being discharged home, higher levels of education, younger age, and white race (see Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article). Additionally, in the hospitalized subgroup, decreasing FAMTM score was significantly correlated with increasing errors on the SPMSQ (Spearman = 0.27, P 0.001), whereas the GCS score was not correlated with the SPMSQ (Spearman = 0.05, P = 0.40) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated the utility of a rapid and accurate mobile application for assessment of mental status. The FAMTM was able to be quickly administered with a median time to completion of approximately 1 minute. The ability to detect mild alterations in mental status was shown through concurrent validity by FAMTM correlation with the SPMSQ and predictive validity with the association between the FAMTM and discharge disposition. Our study highlights the potential for the FAMTM to be used as a sensitive marker of AMS.

The novel design of the FAMTM presents unique advantages compared to current mental status testing. First, the FAMTM could allow patients with hearing impairment or language barriers to complete a mental status assessment. Additionally, the approximately 1‐minute median time to completion is much faster than other established mental status assessments including the SPMSQ (510 minutes). Compared to the SPMSQ taking 5 minutes, in a 400‐bed hospital, taken once per nursing shift, the FAMTM would save approximately 20,000 hours and 10 nursing full‐time equivalents per year.[5] Finally, many current mental status tests such as the Confusion Assessment Model utilize subjective mental status assessments.[2] However, the FAMTM is designed to be conducted through self‐assessment and, thus, could theoretically be free of observer bias. This potential for self‐administration expands beyond other proposed alternative testing mechanisms of the AMS such as ultrabrief assessments that include items such as asking subjects the months of the year backwards, and what is the day of the week?, and assessing arousal.[12, 13, 14]

In research settings and commonly in hospitals, the GCS and AVPU are used clinically for mental status assessment of hospitalized patients.[6, 15] However, similar to previous literature, our study found that the vast majority of hospitalized patients were defined as neurologically intact by the GCS, which is the more accurate predictor of the 2.[7] One major strength of the FAMTM was that it identified an extensive gradation of scores for patients previously labeled as merely alert, providing greater resolution than the GCS in quantifying mental status.

One of the key benefits of the FAMTM is that it can be measured longitudinally over the course of a patient's hospital stay. Therefore, once a baseline FAMTM score is established, variation from the patient's personal baseline could indicate mental status deterioration, which would not be affected by the patient's demographics, health status, or underlying neurocognitive deficits.

There were important limitations to this study. First, limited generalizability of these data may exist due to the single‐center setting and patient population. However, this initial study provides pilot data for further expansion into the potential broad applicability of the FAMTM to other patient populations and settings. Additionally, the cost of large‐scale implementation of the FAMTM is unknown and was beyond the scope of this pilot study. However, to reduce costs, the FAMTM technology could be integrated into existing hospital technology infrastructure. Finally, the scope of this study prevented a complete assessment of all validity measures or comparison to other mental status assessments such as the digit span or serial sevens tests. However, predictive and concurrent validity were assessed with comparison by discharge disposition, SPMSQ, and GCS scores.

In conclusion, this pilot study identifies the FAMTM application as a potentially clinically useful, novel, rapid, and feasible assessment tool of mental status in a general medicine inpatient setting.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Frank Zadravecz, MPH, for his support with this project.

Disclosures: This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIA 2T35AG029795‐07) and in part by career development awards granted to Dr. Churpek, Dr. Edelson, and Dr. Press by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL121080, K23 HL097157, and K23 HL118151, respectively). Dr. Churpek has received honoraria from Chest for invited speaking engagements. Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending (ARCD. P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. In addition, Dr. Edelson has received research support from Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA), the American Heart Association (Dallas, TX), and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway). She has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, IL), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Altered mental status (AMS) is a complex spectrum of cognitive deficits that includes orientation, memory, language, visuospatial ability, and perception.[1] The clinical definitions of both delirium and dementia include AMS as a hallmark clinical prerequisite. Regardless of etiology, this broader AMS definition is particularly salient in the hospital setting, where AMS is present in up to 60% of inpatients and is associated with longer hospital stay as well as increased morbidity and mortality.[2, 3] Not surprisingly, due to the complexity of identifying and assessing changes in mental status, clinically relevant AMS is often undetected among inpatients.[2] However, when detected, the most common causes of AMS (infection, polypharmacy, and pain) are treatable, suggesting that early AMS identification could alert clinicians to early signs of clinical decompensation, potentially improving clinical outcomes.[4]

Because rapid and systemic clinical detection of AMS is limited by the complexity of mental status, a number of assessments have been created, each with their own advantages, limitations, and target populations. These assessments are often limited by time‐intensive administration, subjectivity of mental status assessment, and lack of sensitivity in general medicine patients. Time‐intensive measures, such as the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) have utility in the research setting, whereas current common clinical risk stratification tools (eg, National Early Warning Score) utilize simpler measures such as the Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive (AVPU) and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) as measures of mental status.[2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

To address the need for a brief, clinically feasible, accurate tool in clinical detection of AMS, our group developed a mobile application for working memory testing, the Functional Assessment of Mentation (FAMTM). In this study, we aimed to identify baseline scoring distributions of the FAMTM in a nonhospitalized subgroup, as well as assess the correlation of the FAMTM to discharge disposition and compare it to the SPMSQ in inpatients.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a prospective observational study. Data were collected from both hospitalized and nonhospitalized adult participants as 2 distinct subgroups. Nonhospitalized adult subjects were recruited from a university medical campus (June 2013July 2013; IRB‐12‐0175). Hospitalized participants were recruited from the general medicine service as part of an ongoing study measuring quality of care and resource allocation at the same academic medical center (June 2014August 2014; IRB‐9967).[10]

FAMTM Application

The FAMTM application is a bedside tool for working memory assessment developed for the iPhone mobile operating system (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA) and presented on an iPad mini (Apple). The application interface displays 4 colored rectangles individually labeled with a number (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). The testing portion of the application presents a sequence of numbered rectangles, illuminated 1 at a time in random order. Subjects are prompted first to watch and remember the sequence and then repeat the sequence by touching the screen within each numbered rectangle. Successful reproduction of the sequence is followed by a distinct and longer sequence, whereas unsuccessful attempts are followed by a shorter sequence. The final FAMTM score corresponds to the longest sequence of rectangles successfully repeated by the subject.

Data Collection

In the nonhospitalized subject population, research assistants collected demographic data immediately prior to FAMTM administration. Among hospitalized subjects, GCS information was collected by nursing staff as part of standard clinical care. One research assistant administered the SPMSQ while a second assistant, blinded to the SPMSQ and GCS scores, administered the FAMTM. Clinical data were obtained from medical records (EPIC Systems Corp., Verona, WI). Discharge disposition was dichotomized as discharged home or not.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic characteristics of the 2 subject populations were compared using Student t tests (continuous variables) and 2 tests (categorical variables). Score distribution and discharge disposition comparison was conducted with the Mann‐Whitney U test and area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) analysis, using the trapezoidal rule.[11] Multivariable linear regression was used to investigate the impact of age, race, education, discharge disposition, and hospitalization status on patient scores and times. Correlations between the FAMTM and SPMSQ scores and between the GCS and SPMSQ scores were calculated using the Spearman rank test. Significance was set at a 2‐sided P value of 0.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 931 subjects were enrolled in the study. In the nonhospitalized subgroup, 651 consented to study participation and 612 were included in final analysis. Subjects were excluded if they started but did not complete the application (n = 36) or were under the age of 18 years (n = 3). Of the 363 hospitalized subjects approached for enrollment, 319 were included in the final analysis. Subjects were excluded if they refused to participate (n = 23), were under the age of 18 (n = 2), had technical failures (n = 5), or had physical or visual limitations that precluded them from participation (n = 14). Within the hospitalized subgroup, 268 subjects were discharged home (85%). The table displays demographics and score distributions by subgroup.1

| Nonhospitalized Subjects, n = 612 | Hospitalized Subjects Discharged Home, n = 268 | Hospitalized Subjects Discharged Elsewhere, n = 48 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 52 18 | 52 19 | 62 17 | 0.001 |

| Female sex | 343 (56%) | 158 (59%) | 26 (54%) | 0.63 |

| Education | 0.001 | |||

| Less than high school graduate | 31 (5%) | 32 (12%) | 7 (15%) | |

| High school graduate | 312 (51%) | 153 (57%) | 26 (54%) | |

| College graduate | 263 (43%) | 43 (16%) | 8 (17%) | |

| Missing | 6 (1%) | 40 (15%) | 7 (15%) | |

| Race | 0.001 | |||

| Black | 196 (32%) | 185 (69%) | 34 (71%) | |

| White | 324 (53%) | 75 (28%) | 13 (27%) | |

| Other | 86 (14%) | 4 (1%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Missing | 6 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| FAMTM score, median (IQR) | 5 (47) | 5 (36) | 3 (15) | 0.001 |

The median FAMTM score for the combined study population was 5 (interquartile range [IQR] 36), and median time to completion was 55 seconds (IQR 4567 seconds). A graded reduction was found in the FAMTM score for all stepwise comparisons between nonhospitalized subjects, hospitalized subjects discharged home, and hospitalized subjects not discharged home (median 5 [IQR 47] vs 5 [IQR 36] vs 3 [IQR 15]; P 0.001 for all pairwise comparisons). The AUC for the FAMTM predicting discharge disposition (home vs not) was 0.66 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.58‐0.74]. After adjusting for confounders, higher FAMTM scores were independently associated with not being hospitalized, being discharged home, higher levels of education, younger age, and white race (see Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article). Additionally, in the hospitalized subgroup, decreasing FAMTM score was significantly correlated with increasing errors on the SPMSQ (Spearman = 0.27, P 0.001), whereas the GCS score was not correlated with the SPMSQ (Spearman = 0.05, P = 0.40) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated the utility of a rapid and accurate mobile application for assessment of mental status. The FAMTM was able to be quickly administered with a median time to completion of approximately 1 minute. The ability to detect mild alterations in mental status was shown through concurrent validity by FAMTM correlation with the SPMSQ and predictive validity with the association between the FAMTM and discharge disposition. Our study highlights the potential for the FAMTM to be used as a sensitive marker of AMS.

The novel design of the FAMTM presents unique advantages compared to current mental status testing. First, the FAMTM could allow patients with hearing impairment or language barriers to complete a mental status assessment. Additionally, the approximately 1‐minute median time to completion is much faster than other established mental status assessments including the SPMSQ (510 minutes). Compared to the SPMSQ taking 5 minutes, in a 400‐bed hospital, taken once per nursing shift, the FAMTM would save approximately 20,000 hours and 10 nursing full‐time equivalents per year.[5] Finally, many current mental status tests such as the Confusion Assessment Model utilize subjective mental status assessments.[2] However, the FAMTM is designed to be conducted through self‐assessment and, thus, could theoretically be free of observer bias. This potential for self‐administration expands beyond other proposed alternative testing mechanisms of the AMS such as ultrabrief assessments that include items such as asking subjects the months of the year backwards, and what is the day of the week?, and assessing arousal.[12, 13, 14]

In research settings and commonly in hospitals, the GCS and AVPU are used clinically for mental status assessment of hospitalized patients.[6, 15] However, similar to previous literature, our study found that the vast majority of hospitalized patients were defined as neurologically intact by the GCS, which is the more accurate predictor of the 2.[7] One major strength of the FAMTM was that it identified an extensive gradation of scores for patients previously labeled as merely alert, providing greater resolution than the GCS in quantifying mental status.

One of the key benefits of the FAMTM is that it can be measured longitudinally over the course of a patient's hospital stay. Therefore, once a baseline FAMTM score is established, variation from the patient's personal baseline could indicate mental status deterioration, which would not be affected by the patient's demographics, health status, or underlying neurocognitive deficits.

There were important limitations to this study. First, limited generalizability of these data may exist due to the single‐center setting and patient population. However, this initial study provides pilot data for further expansion into the potential broad applicability of the FAMTM to other patient populations and settings. Additionally, the cost of large‐scale implementation of the FAMTM is unknown and was beyond the scope of this pilot study. However, to reduce costs, the FAMTM technology could be integrated into existing hospital technology infrastructure. Finally, the scope of this study prevented a complete assessment of all validity measures or comparison to other mental status assessments such as the digit span or serial sevens tests. However, predictive and concurrent validity were assessed with comparison by discharge disposition, SPMSQ, and GCS scores.

In conclusion, this pilot study identifies the FAMTM application as a potentially clinically useful, novel, rapid, and feasible assessment tool of mental status in a general medicine inpatient setting.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Frank Zadravecz, MPH, for his support with this project.

Disclosures: This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIA 2T35AG029795‐07) and in part by career development awards granted to Dr. Churpek, Dr. Edelson, and Dr. Press by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL121080, K23 HL097157, and K23 HL118151, respectively). Dr. Churpek has received honoraria from Chest for invited speaking engagements. Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending (ARCD. P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. In addition, Dr. Edelson has received research support from Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA), the American Heart Association (Dallas, TX), and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway). She has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, IL), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

- , . Altered mental status in older patients in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):101–136.

- , , , , , . Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948.

- , , , , . Association between clinically abnormal observations and subsequent in‐hospital mortality: a prospective study. Resuscitation. 2004;62(2):137–141.

- , , . Early recognition of delirium: review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(6):721–729.

- . A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433–441.

- , , , , . The ability of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) to discriminate patients at risk of early cardiac arrest, unanticipated intensive care unit admission, and death. Resuscitation. 2013;84(4):465–470.

- , , , et al. Comparison of mental‐status scales for predicting mortality on the general wards. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):658–663.

- , . Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. Lancet. 1974;304(7872):81–84.

- , , , . Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire as a Screening Test for Dementia and Delirium Among the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35(5):412–416.

- , , , et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874.

- , , . Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845.

- , , , et al. Preliminary development of an ultrabrief two‐item bedside test for delirium. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):645–650.

- , , , , , . The association between an ultrabrief cognitive screening in older adults and hospital outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):651–657.

- , , , et al. Selecting optimal screening items for delirium: an application of item response theory. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:8.

- , , . Variability in agreement between physicians and nurses when measuring the Glasgow Coma Scale in the emergency department limits its clinical usefulness. Emerg Med Australas. 2006;18(4):379–384.

- , . Altered mental status in older patients in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):101–136.

- , , , , , . Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948.

- , , , , . Association between clinically abnormal observations and subsequent in‐hospital mortality: a prospective study. Resuscitation. 2004;62(2):137–141.

- , , . Early recognition of delirium: review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(6):721–729.

- . A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433–441.

- , , , , . The ability of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) to discriminate patients at risk of early cardiac arrest, unanticipated intensive care unit admission, and death. Resuscitation. 2013;84(4):465–470.

- , , , et al. Comparison of mental‐status scales for predicting mortality on the general wards. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):658–663.

- , . Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. Lancet. 1974;304(7872):81–84.

- , , , . Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire as a Screening Test for Dementia and Delirium Among the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35(5):412–416.

- , , , et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874.

- , , . Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845.

- , , , et al. Preliminary development of an ultrabrief two‐item bedside test for delirium. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):645–650.

- , , , , , . The association between an ultrabrief cognitive screening in older adults and hospital outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):651–657.

- , , , et al. Selecting optimal screening items for delirium: an application of item response theory. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:8.

- , , . Variability in agreement between physicians and nurses when measuring the Glasgow Coma Scale in the emergency department limits its clinical usefulness. Emerg Med Australas. 2006;18(4):379–384.

SDEF: Severe acne responds to fixed-combo gel

A convenient, once-daily fixed combination of 0.3% adapalene plus 2.5% benzoyl peroxide gel significantly improved lesion counts over the course of 12 weeks in patients aged 12 years and older with moderate or severe acne.

Investigators enrolled just over 500 patients from 31 sites in the United States and Canada. About half of patients were rated as having severe acne and half as having moderate acne on the investigator’s global assessment (IGA) scale, Dr. Linda F. Stein Gold said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Patients were randomized to three treatment groups: adapalene 0.3%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel (A-BPO-0.3%), adapalene 0.1%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% (A-BPO-0.1%), or vehicle. Patients in each group had approximately the same total lesion count, and about half in each group had truncal acne lesions, said Dr. Stein Gold, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit.

Patients were instructed to use their study medications once daily at night after washing with a provided cleanser. They were provided with a standardized moisturizer and cleaners.