User login

Celebrate Match Day, Future of Hospital Medicine Program

This year’s Match Day takes place on Friday, March 18.

Do you remember when you opened your letter? Do you know someone who is matching this year? Share your stories with SHM on Twitter @SHMLive and use the official Match Day 2016 hashtag, #Match2016, and #FutureofHospitalMedicine, plus encourage your students to do so as well. Follow along with the excitement and join in the conversation throughout the day.

It’s hard to believe, but Match Day 2017 is closer than you think. Fourth-year medical students can visit www.futureofhospitalmedicine.org for all of the resources needed to be successful, including:

- Residency match application checklist

- Application tool kit

- An overview of matching for fellowship applicants

- National Residency Matching Program FAQs

- Information on how to register to match

This year’s Match Day takes place on Friday, March 18.

Do you remember when you opened your letter? Do you know someone who is matching this year? Share your stories with SHM on Twitter @SHMLive and use the official Match Day 2016 hashtag, #Match2016, and #FutureofHospitalMedicine, plus encourage your students to do so as well. Follow along with the excitement and join in the conversation throughout the day.

It’s hard to believe, but Match Day 2017 is closer than you think. Fourth-year medical students can visit www.futureofhospitalmedicine.org for all of the resources needed to be successful, including:

- Residency match application checklist

- Application tool kit

- An overview of matching for fellowship applicants

- National Residency Matching Program FAQs

- Information on how to register to match

This year’s Match Day takes place on Friday, March 18.

Do you remember when you opened your letter? Do you know someone who is matching this year? Share your stories with SHM on Twitter @SHMLive and use the official Match Day 2016 hashtag, #Match2016, and #FutureofHospitalMedicine, plus encourage your students to do so as well. Follow along with the excitement and join in the conversation throughout the day.

It’s hard to believe, but Match Day 2017 is closer than you think. Fourth-year medical students can visit www.futureofhospitalmedicine.org for all of the resources needed to be successful, including:

- Residency match application checklist

- Application tool kit

- An overview of matching for fellowship applicants

- National Residency Matching Program FAQs

- Information on how to register to match

Q&A: Identifying gaps in the treatment of endometriosis

Despite the high prevalence of endometriosis – a condition that is estimated to affect about 10% of women of reproductive age – available treatments are inadequate for some women with chronic pain, and diagnosis is often delayed.

Stacey A. Missmer, Sc.D., the scientific director of the Boston Center for Endometriosis, is looking to advance understanding of the condition through the Women’s Health Study: From Adolescence to Adulthood. In an interview, Dr. Missmer, who is also the director of epidemiologic research in reproductive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, shared the progress of the study and her assessment of the treatment landscape.

Question: How would you rate the currently available treatments – both in terms of medications and surgery – in relieving the symptoms of endometriosis?

Dr. Missmer: The currently available treatments work well for some women and girls with pelvic pain, but it gets more difficult once that pain becomes chronic. If women have geographic and financial access to assisted reproductive treatment, then this works well for most women with endometriosis who also have subfertility. The great dilemma is that for pelvic pain, new nonhormonal/nonsurgical treatments have been slow to come for those who do not find relief with current treatments. These girls and young women are impacted just when they most need to be afforded a high quality of life that allows them to pursue all of their goals and dreams unimpeded by the symptoms associated with endometriosis.

Question: How does the Women’s Health Study: From Adolescence to Adulthood help advance treatment options?

Dr. Missmer: I am very proud of the Women’s Health Study: From Adolescence to Adulthood (A2A). Most studies of endometriosis have focused on women in their 30s and 40s, particularly those who present with infertility as their main health concern. However, we know that for women with endometriosis, the majority experience pain as their presenting symptom, and most report that endometriotic pain began during their teens and 20s. Uniquely, the A2A is a cohort of girl as young as 7 and young women, as well as those up to age 50. It is also uniquely a longitudinal cohort. By enrolling these girls and women now and following them into the future, we will be able to identify what characteristics in adolescence and young adulthood predicted who responds well to current treatments both in the short term and long into their reproductive and productive years.

We’ll also be able to discover the characteristics of those who did not respond as well, and we expect that this will drive us toward identifying unique groups of patients – and consequent biologic markers and patterns that are the basis for developing new treatments and prognostic tools for endometriosis.

Since November 2012, we have enrolled nearly 1,000 participants. Our initial enrollees are now completing their third year of lifestyle and symptom questionnaires, clinical details, and providing biologic samples. Their contributions are invaluable and are designed to be consistent with the harmonized data collection tools that we developed in collaboration with our national and international colleagues through the World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF). These Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking Harmonisation Project (EPHect) tools are publicly available and will allow us to combine data from our cohort with participants at other sites to begin to detect geographic and patient-specific treatment response differences across the globe.

Question: What other studies are you closely watching?

Dr. Missmer: I am thrilled about the opportunities that the WERF EPHect tools offer us and our respected colleagues across the globe. I’m quite excited to see what new collaborations are formed and what creative hypotheses are tested. We’re in the midst of a renaissance in endometriosis understanding. Despite its prevalence and potentially debilitating impact on girls and women, endometriosis research is dramatically underfunded. This impacts discovery itself, but it also diminishes the ability for young enthusiastic brilliant scientists to be drawn to and remain dedicated to our field.

Question: How far are we from a noninvasive test that physicians could use to diagnose endometriosis and monitor its progression?

Dr. Missmer: How far in terms of a time line is difficult to determine. Again, I stress that I believe wholeheartedly that we are in the midst of a renaissance for endometriosis. We now have the tools to advance multidisciplinary scientific discovery with the ability to conduct studies with large numbers of diverse girls and women and to rigorously detect changes in their symptoms across the life course. I have no doubt that this will lead to advancement of precision medicine that allows endometriosis-focused scientists to develop noninvasive diagnostics and novel treatments. The key is that everyone in the field of endometriosis work together with this goal in mind.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Despite the high prevalence of endometriosis – a condition that is estimated to affect about 10% of women of reproductive age – available treatments are inadequate for some women with chronic pain, and diagnosis is often delayed.

Stacey A. Missmer, Sc.D., the scientific director of the Boston Center for Endometriosis, is looking to advance understanding of the condition through the Women’s Health Study: From Adolescence to Adulthood. In an interview, Dr. Missmer, who is also the director of epidemiologic research in reproductive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, shared the progress of the study and her assessment of the treatment landscape.

Question: How would you rate the currently available treatments – both in terms of medications and surgery – in relieving the symptoms of endometriosis?

Dr. Missmer: The currently available treatments work well for some women and girls with pelvic pain, but it gets more difficult once that pain becomes chronic. If women have geographic and financial access to assisted reproductive treatment, then this works well for most women with endometriosis who also have subfertility. The great dilemma is that for pelvic pain, new nonhormonal/nonsurgical treatments have been slow to come for those who do not find relief with current treatments. These girls and young women are impacted just when they most need to be afforded a high quality of life that allows them to pursue all of their goals and dreams unimpeded by the symptoms associated with endometriosis.

Question: How does the Women’s Health Study: From Adolescence to Adulthood help advance treatment options?

Dr. Missmer: I am very proud of the Women’s Health Study: From Adolescence to Adulthood (A2A). Most studies of endometriosis have focused on women in their 30s and 40s, particularly those who present with infertility as their main health concern. However, we know that for women with endometriosis, the majority experience pain as their presenting symptom, and most report that endometriotic pain began during their teens and 20s. Uniquely, the A2A is a cohort of girl as young as 7 and young women, as well as those up to age 50. It is also uniquely a longitudinal cohort. By enrolling these girls and women now and following them into the future, we will be able to identify what characteristics in adolescence and young adulthood predicted who responds well to current treatments both in the short term and long into their reproductive and productive years.

We’ll also be able to discover the characteristics of those who did not respond as well, and we expect that this will drive us toward identifying unique groups of patients – and consequent biologic markers and patterns that are the basis for developing new treatments and prognostic tools for endometriosis.

Since November 2012, we have enrolled nearly 1,000 participants. Our initial enrollees are now completing their third year of lifestyle and symptom questionnaires, clinical details, and providing biologic samples. Their contributions are invaluable and are designed to be consistent with the harmonized data collection tools that we developed in collaboration with our national and international colleagues through the World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF). These Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking Harmonisation Project (EPHect) tools are publicly available and will allow us to combine data from our cohort with participants at other sites to begin to detect geographic and patient-specific treatment response differences across the globe.

Question: What other studies are you closely watching?

Dr. Missmer: I am thrilled about the opportunities that the WERF EPHect tools offer us and our respected colleagues across the globe. I’m quite excited to see what new collaborations are formed and what creative hypotheses are tested. We’re in the midst of a renaissance in endometriosis understanding. Despite its prevalence and potentially debilitating impact on girls and women, endometriosis research is dramatically underfunded. This impacts discovery itself, but it also diminishes the ability for young enthusiastic brilliant scientists to be drawn to and remain dedicated to our field.

Question: How far are we from a noninvasive test that physicians could use to diagnose endometriosis and monitor its progression?

Dr. Missmer: How far in terms of a time line is difficult to determine. Again, I stress that I believe wholeheartedly that we are in the midst of a renaissance for endometriosis. We now have the tools to advance multidisciplinary scientific discovery with the ability to conduct studies with large numbers of diverse girls and women and to rigorously detect changes in their symptoms across the life course. I have no doubt that this will lead to advancement of precision medicine that allows endometriosis-focused scientists to develop noninvasive diagnostics and novel treatments. The key is that everyone in the field of endometriosis work together with this goal in mind.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Despite the high prevalence of endometriosis – a condition that is estimated to affect about 10% of women of reproductive age – available treatments are inadequate for some women with chronic pain, and diagnosis is often delayed.

Stacey A. Missmer, Sc.D., the scientific director of the Boston Center for Endometriosis, is looking to advance understanding of the condition through the Women’s Health Study: From Adolescence to Adulthood. In an interview, Dr. Missmer, who is also the director of epidemiologic research in reproductive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, shared the progress of the study and her assessment of the treatment landscape.

Question: How would you rate the currently available treatments – both in terms of medications and surgery – in relieving the symptoms of endometriosis?

Dr. Missmer: The currently available treatments work well for some women and girls with pelvic pain, but it gets more difficult once that pain becomes chronic. If women have geographic and financial access to assisted reproductive treatment, then this works well for most women with endometriosis who also have subfertility. The great dilemma is that for pelvic pain, new nonhormonal/nonsurgical treatments have been slow to come for those who do not find relief with current treatments. These girls and young women are impacted just when they most need to be afforded a high quality of life that allows them to pursue all of their goals and dreams unimpeded by the symptoms associated with endometriosis.

Question: How does the Women’s Health Study: From Adolescence to Adulthood help advance treatment options?

Dr. Missmer: I am very proud of the Women’s Health Study: From Adolescence to Adulthood (A2A). Most studies of endometriosis have focused on women in their 30s and 40s, particularly those who present with infertility as their main health concern. However, we know that for women with endometriosis, the majority experience pain as their presenting symptom, and most report that endometriotic pain began during their teens and 20s. Uniquely, the A2A is a cohort of girl as young as 7 and young women, as well as those up to age 50. It is also uniquely a longitudinal cohort. By enrolling these girls and women now and following them into the future, we will be able to identify what characteristics in adolescence and young adulthood predicted who responds well to current treatments both in the short term and long into their reproductive and productive years.

We’ll also be able to discover the characteristics of those who did not respond as well, and we expect that this will drive us toward identifying unique groups of patients – and consequent biologic markers and patterns that are the basis for developing new treatments and prognostic tools for endometriosis.

Since November 2012, we have enrolled nearly 1,000 participants. Our initial enrollees are now completing their third year of lifestyle and symptom questionnaires, clinical details, and providing biologic samples. Their contributions are invaluable and are designed to be consistent with the harmonized data collection tools that we developed in collaboration with our national and international colleagues through the World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF). These Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking Harmonisation Project (EPHect) tools are publicly available and will allow us to combine data from our cohort with participants at other sites to begin to detect geographic and patient-specific treatment response differences across the globe.

Question: What other studies are you closely watching?

Dr. Missmer: I am thrilled about the opportunities that the WERF EPHect tools offer us and our respected colleagues across the globe. I’m quite excited to see what new collaborations are formed and what creative hypotheses are tested. We’re in the midst of a renaissance in endometriosis understanding. Despite its prevalence and potentially debilitating impact on girls and women, endometriosis research is dramatically underfunded. This impacts discovery itself, but it also diminishes the ability for young enthusiastic brilliant scientists to be drawn to and remain dedicated to our field.

Question: How far are we from a noninvasive test that physicians could use to diagnose endometriosis and monitor its progression?

Dr. Missmer: How far in terms of a time line is difficult to determine. Again, I stress that I believe wholeheartedly that we are in the midst of a renaissance for endometriosis. We now have the tools to advance multidisciplinary scientific discovery with the ability to conduct studies with large numbers of diverse girls and women and to rigorously detect changes in their symptoms across the life course. I have no doubt that this will lead to advancement of precision medicine that allows endometriosis-focused scientists to develop noninvasive diagnostics and novel treatments. The key is that everyone in the field of endometriosis work together with this goal in mind.

On Twitter @maryellenny

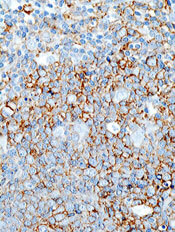

Itraconazole targets basal cell carcinoma

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The familiar oral triazole antifungal agent itraconazole (Sporanox) is under active investigation for an unexpected use: as adjunctive therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma.

“The promise of this drug is that the use of itraconazole with vismodegib or sonidegib may actually enhance the effectiveness of those drugs and also reduce the frequency of grade 2 toxicities by perhaps allowing a lower dose of vismodegib or sonidegib,” Dr. David L. Swanson said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“Be looking for this drug that we use to treat toenail fungus as a potential drug for locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma,” advised Dr. Swanson, a dermatologist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Vismodegib (Erivedge) has been a game changer for patients with inoperable locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. “The response to this drug was amazing,” Dr. Swanson said of the landmark study which led to its approval in 2012 (N Engl J Med. 2012; 366[23]:2171-9).

Sonidegib (Odomzo), which like vismodegib inhibits the essential Hedgehog signaling pathway component known as Smoothened, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 as the second oral drug in this novel class.

While the clinical benefits of these two drugs in patients with the most horrific basal cell carcinomas are extremely impressive, vismodegib and sonidegib have two major drawbacks: The tumors eventually develop resistance and commence growing again, and onerous grade 2 side effects requiring dose reduction are extremely common. The most frequent of these limiting side effects are a disturbed sense of taste, muscle spasms, alopecia, and weight loss.

The hope is that itraconazole may be of help with both issues, according to Dr. Swanson. It turns out that the antifungal agent is also an inhibitor of the Hedgehog pathway, and via a different mechanism than that of vismodegib and sonidegib.

He pointed to an international open-label exploratory phase II study led by Dr. Jean Y. Tang of Stanford (Calif.) University. The investigators treated 19 patients with a total of 90 basal cell carcinomas with oral itraconazole at 200 mg twice a day for 1 month or 100 mg twice a day for an average of 2.3 months.

The treatment reduced Hedgehog signaling pathway activity by 65%, Ki67 tumor cell proliferation by 45%, and tumor area by 24% (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Mar 10;32[8]:745-51).

These results aren’t as dramatic as what’s achieved using vismodegib or sonidegib. As stand-alone therapy, itraconazole doesn’t compare with those agents. However, the hope is that when itraconazole is prescribed in conjunction with vismodegib or sonidegib it will permit the latter drugs to be used at lower doses with no drop-off in efficacy, which would mean less grade 2 toxicity. Moreover, since itraconazole inhibits Hedgehog signaling through a mechanism that is different from that of the more potent agents, combination therapy might delay onset of tumor resistance, Dr. Swanson explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The familiar oral triazole antifungal agent itraconazole (Sporanox) is under active investigation for an unexpected use: as adjunctive therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma.

“The promise of this drug is that the use of itraconazole with vismodegib or sonidegib may actually enhance the effectiveness of those drugs and also reduce the frequency of grade 2 toxicities by perhaps allowing a lower dose of vismodegib or sonidegib,” Dr. David L. Swanson said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“Be looking for this drug that we use to treat toenail fungus as a potential drug for locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma,” advised Dr. Swanson, a dermatologist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Vismodegib (Erivedge) has been a game changer for patients with inoperable locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. “The response to this drug was amazing,” Dr. Swanson said of the landmark study which led to its approval in 2012 (N Engl J Med. 2012; 366[23]:2171-9).

Sonidegib (Odomzo), which like vismodegib inhibits the essential Hedgehog signaling pathway component known as Smoothened, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 as the second oral drug in this novel class.

While the clinical benefits of these two drugs in patients with the most horrific basal cell carcinomas are extremely impressive, vismodegib and sonidegib have two major drawbacks: The tumors eventually develop resistance and commence growing again, and onerous grade 2 side effects requiring dose reduction are extremely common. The most frequent of these limiting side effects are a disturbed sense of taste, muscle spasms, alopecia, and weight loss.

The hope is that itraconazole may be of help with both issues, according to Dr. Swanson. It turns out that the antifungal agent is also an inhibitor of the Hedgehog pathway, and via a different mechanism than that of vismodegib and sonidegib.

He pointed to an international open-label exploratory phase II study led by Dr. Jean Y. Tang of Stanford (Calif.) University. The investigators treated 19 patients with a total of 90 basal cell carcinomas with oral itraconazole at 200 mg twice a day for 1 month or 100 mg twice a day for an average of 2.3 months.

The treatment reduced Hedgehog signaling pathway activity by 65%, Ki67 tumor cell proliferation by 45%, and tumor area by 24% (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Mar 10;32[8]:745-51).

These results aren’t as dramatic as what’s achieved using vismodegib or sonidegib. As stand-alone therapy, itraconazole doesn’t compare with those agents. However, the hope is that when itraconazole is prescribed in conjunction with vismodegib or sonidegib it will permit the latter drugs to be used at lower doses with no drop-off in efficacy, which would mean less grade 2 toxicity. Moreover, since itraconazole inhibits Hedgehog signaling through a mechanism that is different from that of the more potent agents, combination therapy might delay onset of tumor resistance, Dr. Swanson explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The familiar oral triazole antifungal agent itraconazole (Sporanox) is under active investigation for an unexpected use: as adjunctive therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma.

“The promise of this drug is that the use of itraconazole with vismodegib or sonidegib may actually enhance the effectiveness of those drugs and also reduce the frequency of grade 2 toxicities by perhaps allowing a lower dose of vismodegib or sonidegib,” Dr. David L. Swanson said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“Be looking for this drug that we use to treat toenail fungus as a potential drug for locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma,” advised Dr. Swanson, a dermatologist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Vismodegib (Erivedge) has been a game changer for patients with inoperable locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. “The response to this drug was amazing,” Dr. Swanson said of the landmark study which led to its approval in 2012 (N Engl J Med. 2012; 366[23]:2171-9).

Sonidegib (Odomzo), which like vismodegib inhibits the essential Hedgehog signaling pathway component known as Smoothened, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 as the second oral drug in this novel class.

While the clinical benefits of these two drugs in patients with the most horrific basal cell carcinomas are extremely impressive, vismodegib and sonidegib have two major drawbacks: The tumors eventually develop resistance and commence growing again, and onerous grade 2 side effects requiring dose reduction are extremely common. The most frequent of these limiting side effects are a disturbed sense of taste, muscle spasms, alopecia, and weight loss.

The hope is that itraconazole may be of help with both issues, according to Dr. Swanson. It turns out that the antifungal agent is also an inhibitor of the Hedgehog pathway, and via a different mechanism than that of vismodegib and sonidegib.

He pointed to an international open-label exploratory phase II study led by Dr. Jean Y. Tang of Stanford (Calif.) University. The investigators treated 19 patients with a total of 90 basal cell carcinomas with oral itraconazole at 200 mg twice a day for 1 month or 100 mg twice a day for an average of 2.3 months.

The treatment reduced Hedgehog signaling pathway activity by 65%, Ki67 tumor cell proliferation by 45%, and tumor area by 24% (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Mar 10;32[8]:745-51).

These results aren’t as dramatic as what’s achieved using vismodegib or sonidegib. As stand-alone therapy, itraconazole doesn’t compare with those agents. However, the hope is that when itraconazole is prescribed in conjunction with vismodegib or sonidegib it will permit the latter drugs to be used at lower doses with no drop-off in efficacy, which would mean less grade 2 toxicity. Moreover, since itraconazole inhibits Hedgehog signaling through a mechanism that is different from that of the more potent agents, combination therapy might delay onset of tumor resistance, Dr. Swanson explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

A New Approach to “Birthmarks”

A 4-month-old boy is brought in by his mother for evaluation of a “birthmark” that has become more prominent with time. The child complains a bit when the lesion is touched.

His mother gives a history of a normal full-term pregnancy, with an uneventful delivery. Other than the skin lesion, there have been no other known problems with the child’s health.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is a 2-cm bright red nodule in the middle of the child’s forehead. There is a faint blue halo around it, but no other abnormalities are seen in the area or elsewhere on the child’s body. The patient otherwise appears well developed and well nourished; he is quite alert and reactive to verbal stimuli.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Most first-year medical students could tell you this was a case of an infantile hemangioma—but within the past five years, the categorization and treatment of hemangiomas have changed rapidly.

Hemangiomas are benign and usually self-involuting vascular tumors; they are distinct from the family of permanent congenital vascular lesions, such as port wine stains. About 80% occur on the face or neck, and they more commonly occur in female patients. Those that occur near the skin’s surface tend to be bright red, while those of deeper origin are more bluish. Hemangiomas can also occur in extracutaneous areas (eg, the liver); these are usually detected via imaging.

Most infantile hemangiomas appear in the first few weeks of life but begin to involute shortly after they reach maximal size (usually by age 12 months). Involution is complete by age 5 in about 50% of cases and by age 7 in 70% of them. The remainder usually resolve by age 12.

Until recently, the parents of an affected child would be told that the lesions were benign and would likely disappear on their own by the time the child was ages 7 to 10—all true enough. These lesions were treated only when they were large or symptomatic, or if their location blocked or otherwise interfered with the function of the eyes, ears, mouth, anus, or vagina. Unfortunately, this approach ignored the psychosocial aspects of having a prominent and fire-engine red lesion, which often becomes the object of unwanted attention, and even ridicule, at a crucial developmental age.

In the past, the main treatment options were destructive in nature (laser, excision) and often caused as many problems as they solved. Pharmacologic treatment with oral prednisone, and later with interferon, was also tried with mixed success.

In 2008, in a serendipitous observation, a French team came up with a groundbreaking approach: giving systemic propranolol multiple times over a 12 to 18–month period. This method proved to be both safe and effective when used in the right setting by specialists (pediatric dermatologists and/or pediatricians) experienced in this modality. It was found that the lesions responded best if treated before age 6 months.

This has worked so well and so safely that it has quickly become routine. But it will take time before it is sufficiently well known to become the actual standard of care for these common lesions.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Infantile hemangiomas (IH) usually resolve (involute) by age 12 at the latest.

• IH, by definition, is different from permanent congenital vascular malformations, such as port wine stains.

• About 80% of IHs occur on the head and neck; they are often the object of unwanted attention or even ridicule.

• A new treatment approach, systemic propranolol, is now being used routinely and successfully. It works best when the patient is 6 months old or younger.

• Ideally, this new treatment approach should be overseen by the relevant specialist, be it in a pediatric or dermatologic setting.

A 4-month-old boy is brought in by his mother for evaluation of a “birthmark” that has become more prominent with time. The child complains a bit when the lesion is touched.

His mother gives a history of a normal full-term pregnancy, with an uneventful delivery. Other than the skin lesion, there have been no other known problems with the child’s health.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is a 2-cm bright red nodule in the middle of the child’s forehead. There is a faint blue halo around it, but no other abnormalities are seen in the area or elsewhere on the child’s body. The patient otherwise appears well developed and well nourished; he is quite alert and reactive to verbal stimuli.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Most first-year medical students could tell you this was a case of an infantile hemangioma—but within the past five years, the categorization and treatment of hemangiomas have changed rapidly.

Hemangiomas are benign and usually self-involuting vascular tumors; they are distinct from the family of permanent congenital vascular lesions, such as port wine stains. About 80% occur on the face or neck, and they more commonly occur in female patients. Those that occur near the skin’s surface tend to be bright red, while those of deeper origin are more bluish. Hemangiomas can also occur in extracutaneous areas (eg, the liver); these are usually detected via imaging.

Most infantile hemangiomas appear in the first few weeks of life but begin to involute shortly after they reach maximal size (usually by age 12 months). Involution is complete by age 5 in about 50% of cases and by age 7 in 70% of them. The remainder usually resolve by age 12.

Until recently, the parents of an affected child would be told that the lesions were benign and would likely disappear on their own by the time the child was ages 7 to 10—all true enough. These lesions were treated only when they were large or symptomatic, or if their location blocked or otherwise interfered with the function of the eyes, ears, mouth, anus, or vagina. Unfortunately, this approach ignored the psychosocial aspects of having a prominent and fire-engine red lesion, which often becomes the object of unwanted attention, and even ridicule, at a crucial developmental age.

In the past, the main treatment options were destructive in nature (laser, excision) and often caused as many problems as they solved. Pharmacologic treatment with oral prednisone, and later with interferon, was also tried with mixed success.

In 2008, in a serendipitous observation, a French team came up with a groundbreaking approach: giving systemic propranolol multiple times over a 12 to 18–month period. This method proved to be both safe and effective when used in the right setting by specialists (pediatric dermatologists and/or pediatricians) experienced in this modality. It was found that the lesions responded best if treated before age 6 months.

This has worked so well and so safely that it has quickly become routine. But it will take time before it is sufficiently well known to become the actual standard of care for these common lesions.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Infantile hemangiomas (IH) usually resolve (involute) by age 12 at the latest.

• IH, by definition, is different from permanent congenital vascular malformations, such as port wine stains.

• About 80% of IHs occur on the head and neck; they are often the object of unwanted attention or even ridicule.

• A new treatment approach, systemic propranolol, is now being used routinely and successfully. It works best when the patient is 6 months old or younger.

• Ideally, this new treatment approach should be overseen by the relevant specialist, be it in a pediatric or dermatologic setting.

A 4-month-old boy is brought in by his mother for evaluation of a “birthmark” that has become more prominent with time. The child complains a bit when the lesion is touched.

His mother gives a history of a normal full-term pregnancy, with an uneventful delivery. Other than the skin lesion, there have been no other known problems with the child’s health.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is a 2-cm bright red nodule in the middle of the child’s forehead. There is a faint blue halo around it, but no other abnormalities are seen in the area or elsewhere on the child’s body. The patient otherwise appears well developed and well nourished; he is quite alert and reactive to verbal stimuli.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Most first-year medical students could tell you this was a case of an infantile hemangioma—but within the past five years, the categorization and treatment of hemangiomas have changed rapidly.

Hemangiomas are benign and usually self-involuting vascular tumors; they are distinct from the family of permanent congenital vascular lesions, such as port wine stains. About 80% occur on the face or neck, and they more commonly occur in female patients. Those that occur near the skin’s surface tend to be bright red, while those of deeper origin are more bluish. Hemangiomas can also occur in extracutaneous areas (eg, the liver); these are usually detected via imaging.

Most infantile hemangiomas appear in the first few weeks of life but begin to involute shortly after they reach maximal size (usually by age 12 months). Involution is complete by age 5 in about 50% of cases and by age 7 in 70% of them. The remainder usually resolve by age 12.

Until recently, the parents of an affected child would be told that the lesions were benign and would likely disappear on their own by the time the child was ages 7 to 10—all true enough. These lesions were treated only when they were large or symptomatic, or if their location blocked or otherwise interfered with the function of the eyes, ears, mouth, anus, or vagina. Unfortunately, this approach ignored the psychosocial aspects of having a prominent and fire-engine red lesion, which often becomes the object of unwanted attention, and even ridicule, at a crucial developmental age.

In the past, the main treatment options were destructive in nature (laser, excision) and often caused as many problems as they solved. Pharmacologic treatment with oral prednisone, and later with interferon, was also tried with mixed success.

In 2008, in a serendipitous observation, a French team came up with a groundbreaking approach: giving systemic propranolol multiple times over a 12 to 18–month period. This method proved to be both safe and effective when used in the right setting by specialists (pediatric dermatologists and/or pediatricians) experienced in this modality. It was found that the lesions responded best if treated before age 6 months.

This has worked so well and so safely that it has quickly become routine. But it will take time before it is sufficiently well known to become the actual standard of care for these common lesions.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Infantile hemangiomas (IH) usually resolve (involute) by age 12 at the latest.

• IH, by definition, is different from permanent congenital vascular malformations, such as port wine stains.

• About 80% of IHs occur on the head and neck; they are often the object of unwanted attention or even ridicule.

• A new treatment approach, systemic propranolol, is now being used routinely and successfully. It works best when the patient is 6 months old or younger.

• Ideally, this new treatment approach should be overseen by the relevant specialist, be it in a pediatric or dermatologic setting.

Revisiting the ‘Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group'

It has been two years since the “Key Characteristics” was published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.1 The SHM board of directors envisions the Key Characteristics as a tool to improve the performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) and “raise the bar” for the specialty.

At SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine2016.org) next month in San Diego, the Key Characteristics will provide the framework for the Practice Management Pre-Course (Sunday, March 6). The pre-course faculty, of which I am a member, will address all 10 principles of the Key Characteristics (see Table 1), including case studies and practical ideas for performance improvement. As a preview, I will cover Principle 6 and provide a few practical tips that you can implement in your practice.

For a more comprehensive discussion of all the Key Characteristics and how to use them, visit the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page).

Characteristic 6.1

The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care physician and/or other provider(s) involved in the patient’s care in the non-acute-care setting.

Practical tip: Your practice probably has administrative procedures in place to notify PCPs that their patient has been admitted to the hospital, using the electronic health record or secure email, if available, or messaging by fax/phone. But are you receiving vital information from the PCP’s office or from the nursing facility? Establish a protocol for obtaining key history, medication, and diagnostic testing information from these sources. One approach is to request this information when notifying the PCP of the patient’s admission.

Practical tip: Use the “grocery store test” to determine when to contact the PCP during the hospital stay. For example, if the PCP were to run into a family member of the patient in the grocery store, would the PCP want to have learned of a change in the patient’s condition in advance of the family member encounter?

Practical tip: Because reaching skilling nursing facility (SNF) physicians/providers (SNFists) can be challenging, hold an annual social event so that they can meet the hospitalists in your practice face-to-face. At the event, exchange cellphone or beeper numbers with the SNFists, and establish an explicit understanding of how handoffs will occur, especially for high-risk patients.

Characteristic 6.2

The HMG contributes in meaningful ways to the hospital’s efforts to improve care transitions.

Because of readmissions penalties, every hospital in the country is concerned with care transitions and avoiding readmissions. But HMGs want to know which interventions reliably decrease readmissions. The Commonwealth Fund recently released the results of a study of 428 hospitals that participated in national efforts to reduce readmissions, including the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) and Hospital to Home (H2H) initiatives. The study’s primary conclusions were as follows:

- The only strategy consistently associated with reduced risk-standardized readmissions was discharging patients with their appointments already made.2 No other single strategy was reliably associated with a reduction.

- Hospitals that implemented three or more readmission reduction strategies showed a significant decrease in risk-standardized readmissions versus those implementing fewer than three.

Practical tip: Ensure patients leave the hospital with a PCP follow-up appointment made and in hand.

Practical tip: Work with your hospital on at least three definitive strategies to reduce readmissions.

Implement to Improve Your HMG

The basic and updated 2015 versions of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” can be downloaded from the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page). The updated 2015 version provides definitions and requirements and suggested approaches to demonstrating the characteristic that enables the HMG to conduct a comprehensive self-assessment.

In addition, there is a new tool intended for use by hospitalist practice administrators that cross-references the Key Characteristics with another tool, The Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator. TH

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L, et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123-128.

- Bradley EH, Brewster A, Curry L. National campaigns to reduce readmissions: what have we learned? The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2015/oct/national-campaigns-to-reduce-readmissions. Accessed December 28, 2015.

It has been two years since the “Key Characteristics” was published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.1 The SHM board of directors envisions the Key Characteristics as a tool to improve the performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) and “raise the bar” for the specialty.

At SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine2016.org) next month in San Diego, the Key Characteristics will provide the framework for the Practice Management Pre-Course (Sunday, March 6). The pre-course faculty, of which I am a member, will address all 10 principles of the Key Characteristics (see Table 1), including case studies and practical ideas for performance improvement. As a preview, I will cover Principle 6 and provide a few practical tips that you can implement in your practice.

For a more comprehensive discussion of all the Key Characteristics and how to use them, visit the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page).

Characteristic 6.1

The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care physician and/or other provider(s) involved in the patient’s care in the non-acute-care setting.

Practical tip: Your practice probably has administrative procedures in place to notify PCPs that their patient has been admitted to the hospital, using the electronic health record or secure email, if available, or messaging by fax/phone. But are you receiving vital information from the PCP’s office or from the nursing facility? Establish a protocol for obtaining key history, medication, and diagnostic testing information from these sources. One approach is to request this information when notifying the PCP of the patient’s admission.

Practical tip: Use the “grocery store test” to determine when to contact the PCP during the hospital stay. For example, if the PCP were to run into a family member of the patient in the grocery store, would the PCP want to have learned of a change in the patient’s condition in advance of the family member encounter?

Practical tip: Because reaching skilling nursing facility (SNF) physicians/providers (SNFists) can be challenging, hold an annual social event so that they can meet the hospitalists in your practice face-to-face. At the event, exchange cellphone or beeper numbers with the SNFists, and establish an explicit understanding of how handoffs will occur, especially for high-risk patients.

Characteristic 6.2

The HMG contributes in meaningful ways to the hospital’s efforts to improve care transitions.

Because of readmissions penalties, every hospital in the country is concerned with care transitions and avoiding readmissions. But HMGs want to know which interventions reliably decrease readmissions. The Commonwealth Fund recently released the results of a study of 428 hospitals that participated in national efforts to reduce readmissions, including the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) and Hospital to Home (H2H) initiatives. The study’s primary conclusions were as follows:

- The only strategy consistently associated with reduced risk-standardized readmissions was discharging patients with their appointments already made.2 No other single strategy was reliably associated with a reduction.

- Hospitals that implemented three or more readmission reduction strategies showed a significant decrease in risk-standardized readmissions versus those implementing fewer than three.

Practical tip: Ensure patients leave the hospital with a PCP follow-up appointment made and in hand.

Practical tip: Work with your hospital on at least three definitive strategies to reduce readmissions.

Implement to Improve Your HMG

The basic and updated 2015 versions of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” can be downloaded from the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page). The updated 2015 version provides definitions and requirements and suggested approaches to demonstrating the characteristic that enables the HMG to conduct a comprehensive self-assessment.

In addition, there is a new tool intended for use by hospitalist practice administrators that cross-references the Key Characteristics with another tool, The Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator. TH

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L, et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123-128.

- Bradley EH, Brewster A, Curry L. National campaigns to reduce readmissions: what have we learned? The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2015/oct/national-campaigns-to-reduce-readmissions. Accessed December 28, 2015.

It has been two years since the “Key Characteristics” was published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.1 The SHM board of directors envisions the Key Characteristics as a tool to improve the performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) and “raise the bar” for the specialty.

At SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine2016.org) next month in San Diego, the Key Characteristics will provide the framework for the Practice Management Pre-Course (Sunday, March 6). The pre-course faculty, of which I am a member, will address all 10 principles of the Key Characteristics (see Table 1), including case studies and practical ideas for performance improvement. As a preview, I will cover Principle 6 and provide a few practical tips that you can implement in your practice.

For a more comprehensive discussion of all the Key Characteristics and how to use them, visit the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page).

Characteristic 6.1

The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care physician and/or other provider(s) involved in the patient’s care in the non-acute-care setting.

Practical tip: Your practice probably has administrative procedures in place to notify PCPs that their patient has been admitted to the hospital, using the electronic health record or secure email, if available, or messaging by fax/phone. But are you receiving vital information from the PCP’s office or from the nursing facility? Establish a protocol for obtaining key history, medication, and diagnostic testing information from these sources. One approach is to request this information when notifying the PCP of the patient’s admission.

Practical tip: Use the “grocery store test” to determine when to contact the PCP during the hospital stay. For example, if the PCP were to run into a family member of the patient in the grocery store, would the PCP want to have learned of a change in the patient’s condition in advance of the family member encounter?

Practical tip: Because reaching skilling nursing facility (SNF) physicians/providers (SNFists) can be challenging, hold an annual social event so that they can meet the hospitalists in your practice face-to-face. At the event, exchange cellphone or beeper numbers with the SNFists, and establish an explicit understanding of how handoffs will occur, especially for high-risk patients.

Characteristic 6.2

The HMG contributes in meaningful ways to the hospital’s efforts to improve care transitions.

Because of readmissions penalties, every hospital in the country is concerned with care transitions and avoiding readmissions. But HMGs want to know which interventions reliably decrease readmissions. The Commonwealth Fund recently released the results of a study of 428 hospitals that participated in national efforts to reduce readmissions, including the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) and Hospital to Home (H2H) initiatives. The study’s primary conclusions were as follows:

- The only strategy consistently associated with reduced risk-standardized readmissions was discharging patients with their appointments already made.2 No other single strategy was reliably associated with a reduction.

- Hospitals that implemented three or more readmission reduction strategies showed a significant decrease in risk-standardized readmissions versus those implementing fewer than three.

Practical tip: Ensure patients leave the hospital with a PCP follow-up appointment made and in hand.

Practical tip: Work with your hospital on at least three definitive strategies to reduce readmissions.

Implement to Improve Your HMG

The basic and updated 2015 versions of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” can be downloaded from the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page). The updated 2015 version provides definitions and requirements and suggested approaches to demonstrating the characteristic that enables the HMG to conduct a comprehensive self-assessment.

In addition, there is a new tool intended for use by hospitalist practice administrators that cross-references the Key Characteristics with another tool, The Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator. TH

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L, et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123-128.

- Bradley EH, Brewster A, Curry L. National campaigns to reduce readmissions: what have we learned? The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2015/oct/national-campaigns-to-reduce-readmissions. Accessed December 28, 2015.

Regimen can reduce risk of malaria during pregnancy

Photo by Nina Matthews

A 2-drug prophylactic regimen can reduce the risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria during pregnancy, according to a study published in NEJM.

Monthly treatment with the regimen, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DP), reduced the rate of symptomatic malaria, placental malaria, and parasitemia, when compared to less frequent dosing with DP or treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), the current standard prophylactic regimen.

Researchers therefore believe DP may be a feasible alternative to SP, which has become less effective over time.

“The malaria parasite’s resistance to SP is widespread, especially in sub-Saharan Africa,” said study author Abel Kakuru, MD, of the Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration in Kampala, Uganda.

“But we are still using the same drugs because we have no better alternatives.”

In an attempt to identify a better alternative, Dr Kakuru and his colleagues studied 300 pregnant women from Tororo, Uganda, from June 2014 through October 2014. All of the subjects were age 16 or older and anywhere from 12 to 20 weeks pregnant.

The women were randomized to receive 1 of 3 regimens for malaria prophylaxis:

- DP once a month

- DP at 20, 28, and 30 weeks of pregnancy

- SP at 20, 28, and 30 weeks of pregnancy.

Participants had monthly checkups at the study clinic, where they received regular blood tests for malaria. The researchers also assessed malaria infection in the placenta.

Placental malaria was confirmed in 50% of women in the SP group, 34% in the 3-dose-DP group (P=0.03), and 27% in the monthly DP group (P=0.001).

Forty-one percent of the women on SP had malaria parasites in their blood, compared to 17% in the 3-dose DP group (P<0.001), and 5% in the monthly DP group (P<0.001).

None of the women on monthly DP had symptomatic malaria during pregnancy. But there were 41 episodes of malaria during pregnancy in the SP group and 12 episodes in the 3-dose DP group.

The researchers also evaluated the women and infants in the study for a composite adverse birth outcome of spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, low birth weight, preterm delivery, or birth defects.

The risk of any adverse birth outcome was 9% in the monthly DP group, 21% in the 3-dose DP group (P=0.02), and 19% in the SP group (P=0.05).

The researchers concluded that monthly dosing of DP provided the best protection against malaria and called for additional studies to determine if the regimen would provide an effective alternative treatment in other parts of Uganda and elsewhere in Africa. ![]()

Photo by Nina Matthews

A 2-drug prophylactic regimen can reduce the risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria during pregnancy, according to a study published in NEJM.

Monthly treatment with the regimen, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DP), reduced the rate of symptomatic malaria, placental malaria, and parasitemia, when compared to less frequent dosing with DP or treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), the current standard prophylactic regimen.

Researchers therefore believe DP may be a feasible alternative to SP, which has become less effective over time.

“The malaria parasite’s resistance to SP is widespread, especially in sub-Saharan Africa,” said study author Abel Kakuru, MD, of the Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration in Kampala, Uganda.

“But we are still using the same drugs because we have no better alternatives.”

In an attempt to identify a better alternative, Dr Kakuru and his colleagues studied 300 pregnant women from Tororo, Uganda, from June 2014 through October 2014. All of the subjects were age 16 or older and anywhere from 12 to 20 weeks pregnant.

The women were randomized to receive 1 of 3 regimens for malaria prophylaxis:

- DP once a month

- DP at 20, 28, and 30 weeks of pregnancy

- SP at 20, 28, and 30 weeks of pregnancy.

Participants had monthly checkups at the study clinic, where they received regular blood tests for malaria. The researchers also assessed malaria infection in the placenta.

Placental malaria was confirmed in 50% of women in the SP group, 34% in the 3-dose-DP group (P=0.03), and 27% in the monthly DP group (P=0.001).

Forty-one percent of the women on SP had malaria parasites in their blood, compared to 17% in the 3-dose DP group (P<0.001), and 5% in the monthly DP group (P<0.001).

None of the women on monthly DP had symptomatic malaria during pregnancy. But there were 41 episodes of malaria during pregnancy in the SP group and 12 episodes in the 3-dose DP group.

The researchers also evaluated the women and infants in the study for a composite adverse birth outcome of spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, low birth weight, preterm delivery, or birth defects.

The risk of any adverse birth outcome was 9% in the monthly DP group, 21% in the 3-dose DP group (P=0.02), and 19% in the SP group (P=0.05).

The researchers concluded that monthly dosing of DP provided the best protection against malaria and called for additional studies to determine if the regimen would provide an effective alternative treatment in other parts of Uganda and elsewhere in Africa. ![]()

Photo by Nina Matthews

A 2-drug prophylactic regimen can reduce the risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria during pregnancy, according to a study published in NEJM.

Monthly treatment with the regimen, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DP), reduced the rate of symptomatic malaria, placental malaria, and parasitemia, when compared to less frequent dosing with DP or treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), the current standard prophylactic regimen.

Researchers therefore believe DP may be a feasible alternative to SP, which has become less effective over time.

“The malaria parasite’s resistance to SP is widespread, especially in sub-Saharan Africa,” said study author Abel Kakuru, MD, of the Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration in Kampala, Uganda.

“But we are still using the same drugs because we have no better alternatives.”

In an attempt to identify a better alternative, Dr Kakuru and his colleagues studied 300 pregnant women from Tororo, Uganda, from June 2014 through October 2014. All of the subjects were age 16 or older and anywhere from 12 to 20 weeks pregnant.

The women were randomized to receive 1 of 3 regimens for malaria prophylaxis:

- DP once a month

- DP at 20, 28, and 30 weeks of pregnancy

- SP at 20, 28, and 30 weeks of pregnancy.

Participants had monthly checkups at the study clinic, where they received regular blood tests for malaria. The researchers also assessed malaria infection in the placenta.

Placental malaria was confirmed in 50% of women in the SP group, 34% in the 3-dose-DP group (P=0.03), and 27% in the monthly DP group (P=0.001).

Forty-one percent of the women on SP had malaria parasites in their blood, compared to 17% in the 3-dose DP group (P<0.001), and 5% in the monthly DP group (P<0.001).

None of the women on monthly DP had symptomatic malaria during pregnancy. But there were 41 episodes of malaria during pregnancy in the SP group and 12 episodes in the 3-dose DP group.

The researchers also evaluated the women and infants in the study for a composite adverse birth outcome of spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, low birth weight, preterm delivery, or birth defects.

The risk of any adverse birth outcome was 9% in the monthly DP group, 21% in the 3-dose DP group (P=0.02), and 19% in the SP group (P=0.05).

The researchers concluded that monthly dosing of DP provided the best protection against malaria and called for additional studies to determine if the regimen would provide an effective alternative treatment in other parts of Uganda and elsewhere in Africa. ![]()

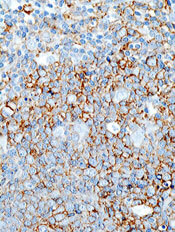

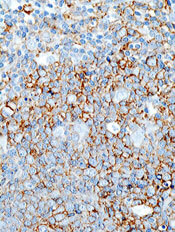

Germline mutations linked to hematologic malignancies

A new study suggests mutations in the gene DDX41 occur in families where hematologic malignancies are common.

Previous research showed that both germline and acquired DDX41 mutations occur in families with multiple cases of late-onset myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The new study, published in Blood, has linked germline mutations in DDX41 to chronic myeloid leukemia and lymphomas as well.

“This is the first gene identified in families with lymphoma and represents a major breakthrough for the field,” said study author Hamish Scott, PhD, of the University of Adelaide in South Australia.

“Researchers are recognizing now that genetic predisposition to blood cancer is more common than previously thought, and our study shows the importance of taking a thorough family history at diagnosis.”

To conduct this study, Dr Scott and his colleagues screened 2 cohorts of families with a range of hematologic disorders (malignant and non-malignant). One cohort included 240 individuals from 93 families in Australia. The other included 246 individuals from 198 families in the US.

In all, 9 of the families (3%) had germline DDX41 mutations.

Three families carried the recurrent p.D140Gfs*2 mutation, which was linked to AML.

One family carried a germline mutation—p.R525H, c.1574G.A—that was previously described only as a somatic mutation at the time of progression to MDS or AML. In the current study, the mutation was again linked to MDS and AML.

Five families carried novel DDX41 mutations.

One of these mutations was a germline substitution—c.435-2_435-1delAGinsCA—that was linked to MDS in 1 family.

Two families had a missense start-loss substitution—c.3G.A, p.M1I—that was linked to MDS, AML, chronic myeloid leukemia, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

One family had a DDX41 missense variant—c.490C.T, p.R164W. This was linked to Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (including 3 cases of follicular lymphoma). There was a possible link to multiple myeloma as well, but the diagnosis could not be confirmed.

And 1 family had a missense mutation in the helicase domain—p.G530D—that was linked to AML.

“DDX41 is a new type of cancer predisposition gene, and we are still investigating its function,” Dr Scott noted.

“But it appears to have dual roles in regulating the correct expression of genes in the cell and also enabling the immune system to respond to threats such as bacteria and viruses, as well as the development of cancer cells. Immunotherapy is a promising approach for cancer treatment, and our research to understand the function of DDX41 will help design better therapies.” ![]()

A new study suggests mutations in the gene DDX41 occur in families where hematologic malignancies are common.

Previous research showed that both germline and acquired DDX41 mutations occur in families with multiple cases of late-onset myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The new study, published in Blood, has linked germline mutations in DDX41 to chronic myeloid leukemia and lymphomas as well.

“This is the first gene identified in families with lymphoma and represents a major breakthrough for the field,” said study author Hamish Scott, PhD, of the University of Adelaide in South Australia.

“Researchers are recognizing now that genetic predisposition to blood cancer is more common than previously thought, and our study shows the importance of taking a thorough family history at diagnosis.”

To conduct this study, Dr Scott and his colleagues screened 2 cohorts of families with a range of hematologic disorders (malignant and non-malignant). One cohort included 240 individuals from 93 families in Australia. The other included 246 individuals from 198 families in the US.

In all, 9 of the families (3%) had germline DDX41 mutations.

Three families carried the recurrent p.D140Gfs*2 mutation, which was linked to AML.

One family carried a germline mutation—p.R525H, c.1574G.A—that was previously described only as a somatic mutation at the time of progression to MDS or AML. In the current study, the mutation was again linked to MDS and AML.

Five families carried novel DDX41 mutations.

One of these mutations was a germline substitution—c.435-2_435-1delAGinsCA—that was linked to MDS in 1 family.

Two families had a missense start-loss substitution—c.3G.A, p.M1I—that was linked to MDS, AML, chronic myeloid leukemia, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

One family had a DDX41 missense variant—c.490C.T, p.R164W. This was linked to Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (including 3 cases of follicular lymphoma). There was a possible link to multiple myeloma as well, but the diagnosis could not be confirmed.

And 1 family had a missense mutation in the helicase domain—p.G530D—that was linked to AML.

“DDX41 is a new type of cancer predisposition gene, and we are still investigating its function,” Dr Scott noted.

“But it appears to have dual roles in regulating the correct expression of genes in the cell and also enabling the immune system to respond to threats such as bacteria and viruses, as well as the development of cancer cells. Immunotherapy is a promising approach for cancer treatment, and our research to understand the function of DDX41 will help design better therapies.” ![]()

A new study suggests mutations in the gene DDX41 occur in families where hematologic malignancies are common.

Previous research showed that both germline and acquired DDX41 mutations occur in families with multiple cases of late-onset myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The new study, published in Blood, has linked germline mutations in DDX41 to chronic myeloid leukemia and lymphomas as well.

“This is the first gene identified in families with lymphoma and represents a major breakthrough for the field,” said study author Hamish Scott, PhD, of the University of Adelaide in South Australia.

“Researchers are recognizing now that genetic predisposition to blood cancer is more common than previously thought, and our study shows the importance of taking a thorough family history at diagnosis.”

To conduct this study, Dr Scott and his colleagues screened 2 cohorts of families with a range of hematologic disorders (malignant and non-malignant). One cohort included 240 individuals from 93 families in Australia. The other included 246 individuals from 198 families in the US.

In all, 9 of the families (3%) had germline DDX41 mutations.

Three families carried the recurrent p.D140Gfs*2 mutation, which was linked to AML.

One family carried a germline mutation—p.R525H, c.1574G.A—that was previously described only as a somatic mutation at the time of progression to MDS or AML. In the current study, the mutation was again linked to MDS and AML.

Five families carried novel DDX41 mutations.

One of these mutations was a germline substitution—c.435-2_435-1delAGinsCA—that was linked to MDS in 1 family.

Two families had a missense start-loss substitution—c.3G.A, p.M1I—that was linked to MDS, AML, chronic myeloid leukemia, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

One family had a DDX41 missense variant—c.490C.T, p.R164W. This was linked to Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (including 3 cases of follicular lymphoma). There was a possible link to multiple myeloma as well, but the diagnosis could not be confirmed.

And 1 family had a missense mutation in the helicase domain—p.G530D—that was linked to AML.

“DDX41 is a new type of cancer predisposition gene, and we are still investigating its function,” Dr Scott noted.

“But it appears to have dual roles in regulating the correct expression of genes in the cell and also enabling the immune system to respond to threats such as bacteria and viruses, as well as the development of cancer cells. Immunotherapy is a promising approach for cancer treatment, and our research to understand the function of DDX41 will help design better therapies.” ![]()

Intracranial bleeding in older adults on warfarin

Results of a large study suggest warfarin may pose a higher risk of traumatic intracranial bleeding than previously reported, at least among older patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

The study included more than 30,000 US veterans with AF who were 75 years or older when starting warfarin.

These patients had a higher rate of traumatic intracranial bleeding than reported in previous trials.

John A. Dodson, MD, of the New York University School of Medicine in New York, New York, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in JAMA Cardiology.

The researchers studied 31,951 subjects with AF who were 75 years or older and were new referrals to Veterans Affairs anticoagulation clinics for warfarin therapy between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2012.

The patients had a mean age of 81.1, and 98.1% were male. Comorbidities included hypertension (82.5%), coronary artery disease (42.6%), and diabetes mellitus (33.8%).

The researchers found the incidence rate of hospitalization for any intracranial bleeding among these patients was 14.58 per 1000 person-years.

And the incidence rate of hospitalization for traumatic intracranial bleeding was 4.80 per 1000 person-years.

The researchers said this was “considerably higher” than reported in two previous trials, one published in The Lancet in 1996 and one published in JAMA Internal Medicine in 1998.

Dr Dodson and his colleagues also looked at factors associated with traumatic intracranial bleeding in their patient population.

In unadjusted analyses, the following factors were significant predictors of traumatic intracranial bleeding: dementia, fall within the past year, anemia, depression, abnormal renal or liver function, anticonvulsant use, labile international normalized ratio, and antihypertensive use.

However, when the researchers adjusted their analyses for potential confounders, fewer factors remained significant predictors. These were dementia (hazard ratio [HR]=1.76), anemia (HR=1.23), depression (HR=1.30), anticonvulsant use (HR=1.35), and labile international normalized ratio (HR=1.33).

The researchers noted that risk factors for traumatic intracranial bleeding were different from risk factors for ischemic stroke.

They also said the high overall rate of intracranial bleeding in this study suggests a need to more systematically evaluate the benefits and harms of warfarin in older adults. ![]()

Results of a large study suggest warfarin may pose a higher risk of traumatic intracranial bleeding than previously reported, at least among older patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

The study included more than 30,000 US veterans with AF who were 75 years or older when starting warfarin.

These patients had a higher rate of traumatic intracranial bleeding than reported in previous trials.

John A. Dodson, MD, of the New York University School of Medicine in New York, New York, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in JAMA Cardiology.

The researchers studied 31,951 subjects with AF who were 75 years or older and were new referrals to Veterans Affairs anticoagulation clinics for warfarin therapy between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2012.

The patients had a mean age of 81.1, and 98.1% were male. Comorbidities included hypertension (82.5%), coronary artery disease (42.6%), and diabetes mellitus (33.8%).

The researchers found the incidence rate of hospitalization for any intracranial bleeding among these patients was 14.58 per 1000 person-years.

And the incidence rate of hospitalization for traumatic intracranial bleeding was 4.80 per 1000 person-years.

The researchers said this was “considerably higher” than reported in two previous trials, one published in The Lancet in 1996 and one published in JAMA Internal Medicine in 1998.

Dr Dodson and his colleagues also looked at factors associated with traumatic intracranial bleeding in their patient population.

In unadjusted analyses, the following factors were significant predictors of traumatic intracranial bleeding: dementia, fall within the past year, anemia, depression, abnormal renal or liver function, anticonvulsant use, labile international normalized ratio, and antihypertensive use.

However, when the researchers adjusted their analyses for potential confounders, fewer factors remained significant predictors. These were dementia (hazard ratio [HR]=1.76), anemia (HR=1.23), depression (HR=1.30), anticonvulsant use (HR=1.35), and labile international normalized ratio (HR=1.33).

The researchers noted that risk factors for traumatic intracranial bleeding were different from risk factors for ischemic stroke.

They also said the high overall rate of intracranial bleeding in this study suggests a need to more systematically evaluate the benefits and harms of warfarin in older adults. ![]()

Results of a large study suggest warfarin may pose a higher risk of traumatic intracranial bleeding than previously reported, at least among older patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

The study included more than 30,000 US veterans with AF who were 75 years or older when starting warfarin.

These patients had a higher rate of traumatic intracranial bleeding than reported in previous trials.

John A. Dodson, MD, of the New York University School of Medicine in New York, New York, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in JAMA Cardiology.

The researchers studied 31,951 subjects with AF who were 75 years or older and were new referrals to Veterans Affairs anticoagulation clinics for warfarin therapy between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2012.

The patients had a mean age of 81.1, and 98.1% were male. Comorbidities included hypertension (82.5%), coronary artery disease (42.6%), and diabetes mellitus (33.8%).

The researchers found the incidence rate of hospitalization for any intracranial bleeding among these patients was 14.58 per 1000 person-years.

And the incidence rate of hospitalization for traumatic intracranial bleeding was 4.80 per 1000 person-years.

The researchers said this was “considerably higher” than reported in two previous trials, one published in The Lancet in 1996 and one published in JAMA Internal Medicine in 1998.

Dr Dodson and his colleagues also looked at factors associated with traumatic intracranial bleeding in their patient population.

In unadjusted analyses, the following factors were significant predictors of traumatic intracranial bleeding: dementia, fall within the past year, anemia, depression, abnormal renal or liver function, anticonvulsant use, labile international normalized ratio, and antihypertensive use.

However, when the researchers adjusted their analyses for potential confounders, fewer factors remained significant predictors. These were dementia (hazard ratio [HR]=1.76), anemia (HR=1.23), depression (HR=1.30), anticonvulsant use (HR=1.35), and labile international normalized ratio (HR=1.33).

The researchers noted that risk factors for traumatic intracranial bleeding were different from risk factors for ischemic stroke.

They also said the high overall rate of intracranial bleeding in this study suggests a need to more systematically evaluate the benefits and harms of warfarin in older adults. ![]()

FDA lifts partial clinical hold on pidilizumab

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the partial clinical hold on the investigational new drug (IND) application for pidilizumab (MDV9300) in hematologic malignancies.

This means the phase 2 trial of pidilizumab in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), as well as other studies that cross-reference the IND for the drug, may now proceed.

The partial clinical hold on pidilizumab was not related to any safety concerns.

The FDA placed the hold because the company developing pidilizumab, Medivation Inc., determined that the drug is not an inhibitor of PD-1, as researchers previously thought.

The phase 2 trial of pidilizumab in DLBCL was launched in late 2015 but had not enrolled any patients before the FDA placed the partial clinical hold.

Patients who were receiving pidilizumab through investigator-sponsored trials have continued to receive treatment despite the hold, and those investigators have been told to update their protocols and informed consent documents to reflect that pidilizumab is not an anti-PD-1 antibody.

Medivation has likewise revised the investigator brochure, protocols, and informed consent documents related to the phase 2 trial of DLBCL patients.

The company said it is still trying to determine pidilizumab’s mechanism of action.