User login

Inpatient Hospital Pain Management

Pain management is an integral component of patient‐centered medical care and is a major concern for patients who are hospitalized.[1] Patient‐reported ratings of pain management are highly correlated with overall satisfaction with healthcare delivery.[2] Current research indicates that patient satisfaction with pain management may be improving[3]; however, there may be structural and county‐level disparities in these improvements in satisfaction. Although patient satisfaction with pain management increased from 2008 to 2012, a discrepancy in patient satisfaction with pain management has emerged between 3 different hospital systems (safety net, acute care, critical access hospitals)[3] Specifically, acute care hospitals provide less satisfactory pain management as compared to critical access hospitals.[3] Although patients' perception of pain management is an integral part of delivering patient‐centered care, prior research indicates that there may not be a simple inverse association between pain intensity score and patient satisfaction.[4] The management of pain in hospitals continues to be problematic, perhaps, for instance, due to discrepancies in understanding the relationship between patient satisfaction and pain management. Certainly for this reason and many others, satisfaction with pain management is now one of the dimensions assessed by the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, which is a global measure of patient satisfaction.

The HCAHPS survey is utilized by 85% of all US‐based hospitals and gathers patient satisfaction information pertaining to 10 dimensions, including pain management. Patient satisfaction scores (via HCAHPS) now constitute 30% of Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing (HVBP), which makes up 2% of at‐risk reimbursements by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) as put forth by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010.[5] The ACA mandates that payments to hospitals must partly depend on metrics that assess patient satisfaction, as broadly measured by the HCAHPS, which are completed by patients upon hospital discharge.[5, 6] Therefore, patient satisfaction, as measured by patients, now directly affects CMS payments for over 3000 hospitals across the United States. This constitutes a large amount of money for most hospitals that operate on high revenue but have low profit margins. As such, the 2% at‐risk reimbursement may place many hospitals at financial risk that could be ameliorated with effective inpatient pain management.

In addition to its critical role in reimbursement to hospitals, patient satisfaction with pain management is also integrally related to providing patient‐centered care. As such, patient satisfaction with pain management is considered a critical element of various models of the patient‐centered approach to providing medical care. Although a medical inpatient team can assess objective signs of pain, patient‐centric pain measurements are paramount in understanding the pain experience of patients and providing adequate pain management care. Moreover, patients, doctors, payers of medical services, and now CMS increasingly regard a patient‐centered approach to medical care as crucial for the delivery of high‐quality care.

HCAHPS survey sampling represents an excellent opportunity to help assess current gaps in patient‐centered clinical care. However, ecological factors, such as county‐level demographics and hospital size (eg, bed number), are known to influence health outcomes but have not been adequately studied in pain management patient satisfaction.[7] Hospital and county‐level factors may influence the degree to which patients experience patient‐centered pain management care. For instance, most patient satisfaction scores are worse in urban areas.[8, 9] These disparities in patient satisfaction scores could be associated with population density, greater ethnic diversity or nonEnglish‐speaking individuals, or number of hospital beds.

The US Census demographics and hospital‐bed number provide a concurrent measure that can be used across the country to estimate hospital ecology. This study evaluated the influence of county‐level demographic and structural factors (ie, hospital beds) on patient satisfaction with hospital pain management in all HCAHPS‐participating hospitals across the United States. We hypothesized that demographic diversity, higher population density, and higher numbers of hospital beds would predict lower levels of patient satisfaction with inpatient pain management.

METHODS

Data Collection: County‐Level Predictors

Publically available data were obtained from the American Hospital Directory[10] and United States Census Bureau[11] websites. Twenty US Census data categories were selected a priori by their clinical relevance to influence pain management perception out of the 50 publically reported US Census categories. Final variables utilized in regression modeling are listed under the Variable column in Table 1. Covariate correlation coefficients were all under 0.7, indicating a lack of significant colinearity.

| Variable | Median Value (SD) | Range | Regression Coefficient (SE) | t Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| African American alone, % | 5.6% (13.8%) | 0%85.4% | 0.02 (00) | 3.609* |

| White alone, % | 86.2% (15.8%) | 5.3%99.0% | 0.06 (0.01) | 6.661* |

| Per capita income | $24,499 ($6,419) | $7,887$61,290 | 0.00 (0.00) | 7.561* |

| With bachelor's degree, % | 22.0% (10.1%) | 6.3%70.7% | 0.06 (0.01) | 7.348* |

| Population 18 years of age, % | 23.2% (3.1%) | 8.3%40.6% | 0.18 (0.05) | 3.498* |

| With a high school degree, % | 86.0% (6.4%) | 46.3%98.6% | 0.02 (0.01) | 1.424 |

| Population change over 1 year, % | 0.7% (2.2%) | 18.1%25.6% | 0.25 (0.04) | 5.645* |

| Same house over 1 year, % | 85.4% (4.2%) | 57.1%98.0% | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.493 |

| White alone (not Hispanic), % | 75.2% (21.8%) | 3.2%98.4% | 0.05(0.00) | 12.077* |

| Household size | 2.52 (0.3) | 1.924.77 | 2.266 (0.36) | 6.283* |

| Population county | 105,937 (1,524,223) | 1,1609,818,605 | 0.00 (0.00) | 13.117* |

| Average travel time to work, min | 23 (5.0) | 642.5 | 0.21 (0.02) | 11.071* |

| NonEnglish speaking, % | 8.6% (15.1%) | 0.2%95.9% | 0.08 (0.01) | 13.843* |

| Total female, % | 50.7% (1.6%) | 34.4%57.0% | 0.44 (0.06) | 7.489* |

| Population 65 years old, % | 14.7% (4.1%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.06 (0.02) | 2.697 |

| Population in poverty, % | 14.7% (5.6%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.02 (0.02) | 1.01 |

| Population density | 138.7 (4,534) | 0.369,467 | 0.73 (0.05) | 15.734* |

| Foreign born, % | 4.9% (9.3%) | 0%51.2% | 0.15 (0.01) | 16.775* |

| Median household income | $46,880 ($12,868) | $20,206$120,096 | 0.00 (0.00) | 6.052* |

| No. of hospital beds | 103 (193) | 22,259 | 0.01 (0.00) | 15.403* |

Data Collection: Patient Satisfaction With Pain Management

Pain management was measured using the HCAHPS survey pain management dimension by calculating the percentage of patient responders who said their pain was always controlled. HCAHPS data are publically available on the CMS Hospital Compare website.[6] It contains 32 questions that comprise 10 evaluative measures. It is provided to a random sample of patients across the United States throughout the year at 48 hours to 6 weeks after discharge from the hospital.

Analytic Plan

HCAHPS and US Census datasets were analyzed to assess their distribution curves. The population density variable was converted to a logarithmic scale to account for its skewed distribution and long tail in the area of low population density. Data were subsequently merged into an Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) spreadsheet using the VLOOKUP function such that relevant 2010 census county data were added to each hospital's HCAHPS data.

Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine which US Census categories were significant predictors for patient satisfaction with pain management. All significant predictors were then included in a multivariate model, which predicted for patient satisfaction with pain management. All analyses were 2‐tailed, and statistical significance was set at = 0.05.

RESULTS

Complete HCAHPS scores were obtained from 3907 hospitals out of a total of 4621 US hospitals (85%). The majority of hospitals (73.8%, n = 2884) collected over 300 surveys, fewer (n = 696) collected 100 to 299 surveys, and a small number of hospitals (n = 327) collected less than 100 surveys. Based on the most conservative estimate, results were available from at least 934,800 individual surveys. Missing HCAHPS hospital data averaged 13.4 (standard deviation [SD] = 12.2) hospitals per state. County‐level data were obtained from all 3144 county or county equivalents across the United States (100%).

Bivariate Analyses

Univariate regression indicated a significant association between pain management patient satisfaction and most county‐level demographic variables and number of hospital beds.

Multivariate Analyses

A multivariate linear regression model was run in which 20 county‐level demographic and hospital factors were examined as predictors of patient satisfaction with pain management. The model, which examined county‐level predictors of pain management, explained 12% of the variability in patients' ratings of pain management (R2 = 0.124, P 0.0001). A total of 8 out of the 20 US Census variables were statistically significant predictors of pain management (Table 2). African American and white race were most strongly associated with higher ratings of patient satisfaction with pain management (ie, by partial coefficient and statistical significance). Number of hospital beds, percent foreign born, population density, and female gender were most strongly related to lower ratings of patient satisfaction with pain management.

| Variable | Median Value (SD) | Range | Regression Coefficient (SE) | t Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| African American alone, % | 5.6% (13.8%) | 0%85.4% | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.23 | 7.104* |

| White alone, % | 86.2% (15.8%) | 5.3%99.0% | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.23 | 6.953* |

| Per capita income | $24,499 ($6,419) | $7,887$61,290 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.22 | 2.885 |

| With bachelor's degree, % | 22.0% (10.1%) | 6.3%70.7% | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.10 | 1.401 |

| Population 18 years old, % | 23.2% (3.1%) | 8.3%40.6% | 0.18 (0.05) | 0.08 | 3.498* |

| With a high school degree, % | 86.0% (6.4%) | 46.3%98.6% | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 | 1.424 |

| Population change over 1 year, % | 0.7% (2.2%) | 18.1%25.6% | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.01 | 1.986 |

| Same house over 1 year, % | 85.4% (4.2%) | 57.1%98.0% | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 | 0.493 |

| White alone (not Hispanic), % | 75.2% (21.8%) | 3.2%98.4% | 0.02(0.00) | 0.01 | 0.740 |

| Household size | 2.52 (0.3) | 1.924.77 | 0.92 (0.80) | 0.03 | 1.145 |

| Population county | 105,937 (1,524,223) | 1,1609,818,605 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.03 | 1.495 |

| Average travel time to work, min | 23 (5.0) | 642.5 | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.06 | 3.054 |

| NonEnglish speaking, % | 8.6% (15.1%) | 0.2%95.9% | 0.00 (0.03) | 0.06 | 0.028 |

| Total female, % | 50.7% (1.6%) | 34.4%57.0% | 0.23 (0.07) | 0.06 | 3.158 |

| Population 65 years old, % | 14.7% (4.1%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.10 (0.04) | 0.07 | 2.411 |

| Population in poverty, % | 14.7% (5.6%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.08 | 1.01 |

| Population density | 138.7 (4,534) | 0.369,467 | 0.24 (0.09) | 0.08 | 2.823 |

| Foreign born, % | 4.9% (9.3%) | 0%51.2% | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.12 | 4.906* |

| Median household income | $46,880 ($12,868) | $20,206‐$120,096 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.16 | 2.599 |

| No. of hospital beds | 103 (193) | 22,259 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.16 | 9.167* |

| Model statistics | F(1, 9) = 62.222, P 0.001 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.124 | ||||

DISCUSSION

By utilizing county‐level demographic data and the HCAHPS survey measures from across the United States, this study provides a representative sample of US hospitals that can be used to define ecological trends in patient satisfaction with pain management. This statistical model demonstrates the nonrandom variability of pain management satisfaction across the United States, even after CMS patient‐mix adjustment. Although the quality of pain management may be increasing by some reports, our present results indicate that pain management satisfaction is not equitable with the rest of the country among select groups of patients (eg, foreign born, female gender, areas of long travel times to work) or in certain care settings (eg, larger hospitals, population dense areas). These data suggest that areas of pain management may lack in quality compared to pain management across the entire US as a whole. This is consistent with the increasingly recognized contribution of multiple nonmedical determinates to health outcomes.[12] These results demonstrate the overall magnitude of healthcare disparity in the United States, and are particularly concerning because African Americans and Hispanics tend to rate overall satisfaction higher than Caucasians in other studies.[13, 14] The same minority reporting bias may be reflected in HCAHPS results. These patients may be reporting higher pain management satisfaction that is not consistent with the level of care they received, as studies have consistently indicated worse pain management delivery for racial and ethnic minorities.[15]

The present findings reveal structural (eg, hospital beds) and demographic (eg, population density, foreign born) gaps in satisfaction with pain management. An effort to improve pain management for all people in the heterogeneous makeup of the United States is an enormous challenge. However, change may be forthcoming, as Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing draws attention pain practice inequities in real time. Although several of the significant explanatory variables cannot be modified (eg, size of hospital, urban setting, patients served), pain management delivery should receive extra attention in hospitals with those characteristics. Pain management delivery in large, urban hospitals that serve foreign‐born patients may be improved with focused multilevel interventions. Future research should examine these inequities further and develop multilevel interventions that target hospitals in at‐risk areas with the aim of lessening disparities in hospital‐based pain management.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient‐centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267.

- , , , . Patient perception of pain care in hospitals in the United States. J Pain Res. 2009;2:157–164.

- , , , , . Patient perception of pain care in the United States: a 5‐year comparative analysis of hospital consumer assessment of health care providers and systems. Pain Physician. 2014;17(5):369–377.

- , , , , . Assessing the relationship between the level of pain control and patient satisfaction. J Pain Res. 2013;6:683–689.

- H.R.3590—Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th‐congress/house‐bill/3590. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare 55(1):125–139.

- , . Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342–343.

- , , , . Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–1931.

- American Hospital Directory. Hospital statistics by state. Available at: http://www.ahd.com/state_statistics.html. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- United States Census Bureau. Download center. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/download_center.xhtml. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Health policy brief: the relative contribution of multiple determinants to health outcomes. Health Affairs website. Available at: http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=123. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- , , , , . Racial and ethnic differences in patient assessments of interactions with providers: disparities or measurement biases? Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(2):109–114.

- , , , , . Survey response style and differential use of CAHPS rating scales by Hispanics. Med Care. 2008;46(9):963–968.

- Institute of Medicine. Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

Pain management is an integral component of patient‐centered medical care and is a major concern for patients who are hospitalized.[1] Patient‐reported ratings of pain management are highly correlated with overall satisfaction with healthcare delivery.[2] Current research indicates that patient satisfaction with pain management may be improving[3]; however, there may be structural and county‐level disparities in these improvements in satisfaction. Although patient satisfaction with pain management increased from 2008 to 2012, a discrepancy in patient satisfaction with pain management has emerged between 3 different hospital systems (safety net, acute care, critical access hospitals)[3] Specifically, acute care hospitals provide less satisfactory pain management as compared to critical access hospitals.[3] Although patients' perception of pain management is an integral part of delivering patient‐centered care, prior research indicates that there may not be a simple inverse association between pain intensity score and patient satisfaction.[4] The management of pain in hospitals continues to be problematic, perhaps, for instance, due to discrepancies in understanding the relationship between patient satisfaction and pain management. Certainly for this reason and many others, satisfaction with pain management is now one of the dimensions assessed by the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, which is a global measure of patient satisfaction.

The HCAHPS survey is utilized by 85% of all US‐based hospitals and gathers patient satisfaction information pertaining to 10 dimensions, including pain management. Patient satisfaction scores (via HCAHPS) now constitute 30% of Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing (HVBP), which makes up 2% of at‐risk reimbursements by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) as put forth by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010.[5] The ACA mandates that payments to hospitals must partly depend on metrics that assess patient satisfaction, as broadly measured by the HCAHPS, which are completed by patients upon hospital discharge.[5, 6] Therefore, patient satisfaction, as measured by patients, now directly affects CMS payments for over 3000 hospitals across the United States. This constitutes a large amount of money for most hospitals that operate on high revenue but have low profit margins. As such, the 2% at‐risk reimbursement may place many hospitals at financial risk that could be ameliorated with effective inpatient pain management.

In addition to its critical role in reimbursement to hospitals, patient satisfaction with pain management is also integrally related to providing patient‐centered care. As such, patient satisfaction with pain management is considered a critical element of various models of the patient‐centered approach to providing medical care. Although a medical inpatient team can assess objective signs of pain, patient‐centric pain measurements are paramount in understanding the pain experience of patients and providing adequate pain management care. Moreover, patients, doctors, payers of medical services, and now CMS increasingly regard a patient‐centered approach to medical care as crucial for the delivery of high‐quality care.

HCAHPS survey sampling represents an excellent opportunity to help assess current gaps in patient‐centered clinical care. However, ecological factors, such as county‐level demographics and hospital size (eg, bed number), are known to influence health outcomes but have not been adequately studied in pain management patient satisfaction.[7] Hospital and county‐level factors may influence the degree to which patients experience patient‐centered pain management care. For instance, most patient satisfaction scores are worse in urban areas.[8, 9] These disparities in patient satisfaction scores could be associated with population density, greater ethnic diversity or nonEnglish‐speaking individuals, or number of hospital beds.

The US Census demographics and hospital‐bed number provide a concurrent measure that can be used across the country to estimate hospital ecology. This study evaluated the influence of county‐level demographic and structural factors (ie, hospital beds) on patient satisfaction with hospital pain management in all HCAHPS‐participating hospitals across the United States. We hypothesized that demographic diversity, higher population density, and higher numbers of hospital beds would predict lower levels of patient satisfaction with inpatient pain management.

METHODS

Data Collection: County‐Level Predictors

Publically available data were obtained from the American Hospital Directory[10] and United States Census Bureau[11] websites. Twenty US Census data categories were selected a priori by their clinical relevance to influence pain management perception out of the 50 publically reported US Census categories. Final variables utilized in regression modeling are listed under the Variable column in Table 1. Covariate correlation coefficients were all under 0.7, indicating a lack of significant colinearity.

| Variable | Median Value (SD) | Range | Regression Coefficient (SE) | t Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| African American alone, % | 5.6% (13.8%) | 0%85.4% | 0.02 (00) | 3.609* |

| White alone, % | 86.2% (15.8%) | 5.3%99.0% | 0.06 (0.01) | 6.661* |

| Per capita income | $24,499 ($6,419) | $7,887$61,290 | 0.00 (0.00) | 7.561* |

| With bachelor's degree, % | 22.0% (10.1%) | 6.3%70.7% | 0.06 (0.01) | 7.348* |

| Population 18 years of age, % | 23.2% (3.1%) | 8.3%40.6% | 0.18 (0.05) | 3.498* |

| With a high school degree, % | 86.0% (6.4%) | 46.3%98.6% | 0.02 (0.01) | 1.424 |

| Population change over 1 year, % | 0.7% (2.2%) | 18.1%25.6% | 0.25 (0.04) | 5.645* |

| Same house over 1 year, % | 85.4% (4.2%) | 57.1%98.0% | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.493 |

| White alone (not Hispanic), % | 75.2% (21.8%) | 3.2%98.4% | 0.05(0.00) | 12.077* |

| Household size | 2.52 (0.3) | 1.924.77 | 2.266 (0.36) | 6.283* |

| Population county | 105,937 (1,524,223) | 1,1609,818,605 | 0.00 (0.00) | 13.117* |

| Average travel time to work, min | 23 (5.0) | 642.5 | 0.21 (0.02) | 11.071* |

| NonEnglish speaking, % | 8.6% (15.1%) | 0.2%95.9% | 0.08 (0.01) | 13.843* |

| Total female, % | 50.7% (1.6%) | 34.4%57.0% | 0.44 (0.06) | 7.489* |

| Population 65 years old, % | 14.7% (4.1%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.06 (0.02) | 2.697 |

| Population in poverty, % | 14.7% (5.6%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.02 (0.02) | 1.01 |

| Population density | 138.7 (4,534) | 0.369,467 | 0.73 (0.05) | 15.734* |

| Foreign born, % | 4.9% (9.3%) | 0%51.2% | 0.15 (0.01) | 16.775* |

| Median household income | $46,880 ($12,868) | $20,206$120,096 | 0.00 (0.00) | 6.052* |

| No. of hospital beds | 103 (193) | 22,259 | 0.01 (0.00) | 15.403* |

Data Collection: Patient Satisfaction With Pain Management

Pain management was measured using the HCAHPS survey pain management dimension by calculating the percentage of patient responders who said their pain was always controlled. HCAHPS data are publically available on the CMS Hospital Compare website.[6] It contains 32 questions that comprise 10 evaluative measures. It is provided to a random sample of patients across the United States throughout the year at 48 hours to 6 weeks after discharge from the hospital.

Analytic Plan

HCAHPS and US Census datasets were analyzed to assess their distribution curves. The population density variable was converted to a logarithmic scale to account for its skewed distribution and long tail in the area of low population density. Data were subsequently merged into an Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) spreadsheet using the VLOOKUP function such that relevant 2010 census county data were added to each hospital's HCAHPS data.

Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine which US Census categories were significant predictors for patient satisfaction with pain management. All significant predictors were then included in a multivariate model, which predicted for patient satisfaction with pain management. All analyses were 2‐tailed, and statistical significance was set at = 0.05.

RESULTS

Complete HCAHPS scores were obtained from 3907 hospitals out of a total of 4621 US hospitals (85%). The majority of hospitals (73.8%, n = 2884) collected over 300 surveys, fewer (n = 696) collected 100 to 299 surveys, and a small number of hospitals (n = 327) collected less than 100 surveys. Based on the most conservative estimate, results were available from at least 934,800 individual surveys. Missing HCAHPS hospital data averaged 13.4 (standard deviation [SD] = 12.2) hospitals per state. County‐level data were obtained from all 3144 county or county equivalents across the United States (100%).

Bivariate Analyses

Univariate regression indicated a significant association between pain management patient satisfaction and most county‐level demographic variables and number of hospital beds.

Multivariate Analyses

A multivariate linear regression model was run in which 20 county‐level demographic and hospital factors were examined as predictors of patient satisfaction with pain management. The model, which examined county‐level predictors of pain management, explained 12% of the variability in patients' ratings of pain management (R2 = 0.124, P 0.0001). A total of 8 out of the 20 US Census variables were statistically significant predictors of pain management (Table 2). African American and white race were most strongly associated with higher ratings of patient satisfaction with pain management (ie, by partial coefficient and statistical significance). Number of hospital beds, percent foreign born, population density, and female gender were most strongly related to lower ratings of patient satisfaction with pain management.

| Variable | Median Value (SD) | Range | Regression Coefficient (SE) | t Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| African American alone, % | 5.6% (13.8%) | 0%85.4% | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.23 | 7.104* |

| White alone, % | 86.2% (15.8%) | 5.3%99.0% | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.23 | 6.953* |

| Per capita income | $24,499 ($6,419) | $7,887$61,290 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.22 | 2.885 |

| With bachelor's degree, % | 22.0% (10.1%) | 6.3%70.7% | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.10 | 1.401 |

| Population 18 years old, % | 23.2% (3.1%) | 8.3%40.6% | 0.18 (0.05) | 0.08 | 3.498* |

| With a high school degree, % | 86.0% (6.4%) | 46.3%98.6% | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 | 1.424 |

| Population change over 1 year, % | 0.7% (2.2%) | 18.1%25.6% | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.01 | 1.986 |

| Same house over 1 year, % | 85.4% (4.2%) | 57.1%98.0% | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 | 0.493 |

| White alone (not Hispanic), % | 75.2% (21.8%) | 3.2%98.4% | 0.02(0.00) | 0.01 | 0.740 |

| Household size | 2.52 (0.3) | 1.924.77 | 0.92 (0.80) | 0.03 | 1.145 |

| Population county | 105,937 (1,524,223) | 1,1609,818,605 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.03 | 1.495 |

| Average travel time to work, min | 23 (5.0) | 642.5 | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.06 | 3.054 |

| NonEnglish speaking, % | 8.6% (15.1%) | 0.2%95.9% | 0.00 (0.03) | 0.06 | 0.028 |

| Total female, % | 50.7% (1.6%) | 34.4%57.0% | 0.23 (0.07) | 0.06 | 3.158 |

| Population 65 years old, % | 14.7% (4.1%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.10 (0.04) | 0.07 | 2.411 |

| Population in poverty, % | 14.7% (5.6%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.08 | 1.01 |

| Population density | 138.7 (4,534) | 0.369,467 | 0.24 (0.09) | 0.08 | 2.823 |

| Foreign born, % | 4.9% (9.3%) | 0%51.2% | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.12 | 4.906* |

| Median household income | $46,880 ($12,868) | $20,206‐$120,096 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.16 | 2.599 |

| No. of hospital beds | 103 (193) | 22,259 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.16 | 9.167* |

| Model statistics | F(1, 9) = 62.222, P 0.001 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.124 | ||||

DISCUSSION

By utilizing county‐level demographic data and the HCAHPS survey measures from across the United States, this study provides a representative sample of US hospitals that can be used to define ecological trends in patient satisfaction with pain management. This statistical model demonstrates the nonrandom variability of pain management satisfaction across the United States, even after CMS patient‐mix adjustment. Although the quality of pain management may be increasing by some reports, our present results indicate that pain management satisfaction is not equitable with the rest of the country among select groups of patients (eg, foreign born, female gender, areas of long travel times to work) or in certain care settings (eg, larger hospitals, population dense areas). These data suggest that areas of pain management may lack in quality compared to pain management across the entire US as a whole. This is consistent with the increasingly recognized contribution of multiple nonmedical determinates to health outcomes.[12] These results demonstrate the overall magnitude of healthcare disparity in the United States, and are particularly concerning because African Americans and Hispanics tend to rate overall satisfaction higher than Caucasians in other studies.[13, 14] The same minority reporting bias may be reflected in HCAHPS results. These patients may be reporting higher pain management satisfaction that is not consistent with the level of care they received, as studies have consistently indicated worse pain management delivery for racial and ethnic minorities.[15]

The present findings reveal structural (eg, hospital beds) and demographic (eg, population density, foreign born) gaps in satisfaction with pain management. An effort to improve pain management for all people in the heterogeneous makeup of the United States is an enormous challenge. However, change may be forthcoming, as Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing draws attention pain practice inequities in real time. Although several of the significant explanatory variables cannot be modified (eg, size of hospital, urban setting, patients served), pain management delivery should receive extra attention in hospitals with those characteristics. Pain management delivery in large, urban hospitals that serve foreign‐born patients may be improved with focused multilevel interventions. Future research should examine these inequities further and develop multilevel interventions that target hospitals in at‐risk areas with the aim of lessening disparities in hospital‐based pain management.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Pain management is an integral component of patient‐centered medical care and is a major concern for patients who are hospitalized.[1] Patient‐reported ratings of pain management are highly correlated with overall satisfaction with healthcare delivery.[2] Current research indicates that patient satisfaction with pain management may be improving[3]; however, there may be structural and county‐level disparities in these improvements in satisfaction. Although patient satisfaction with pain management increased from 2008 to 2012, a discrepancy in patient satisfaction with pain management has emerged between 3 different hospital systems (safety net, acute care, critical access hospitals)[3] Specifically, acute care hospitals provide less satisfactory pain management as compared to critical access hospitals.[3] Although patients' perception of pain management is an integral part of delivering patient‐centered care, prior research indicates that there may not be a simple inverse association between pain intensity score and patient satisfaction.[4] The management of pain in hospitals continues to be problematic, perhaps, for instance, due to discrepancies in understanding the relationship between patient satisfaction and pain management. Certainly for this reason and many others, satisfaction with pain management is now one of the dimensions assessed by the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, which is a global measure of patient satisfaction.

The HCAHPS survey is utilized by 85% of all US‐based hospitals and gathers patient satisfaction information pertaining to 10 dimensions, including pain management. Patient satisfaction scores (via HCAHPS) now constitute 30% of Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing (HVBP), which makes up 2% of at‐risk reimbursements by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) as put forth by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010.[5] The ACA mandates that payments to hospitals must partly depend on metrics that assess patient satisfaction, as broadly measured by the HCAHPS, which are completed by patients upon hospital discharge.[5, 6] Therefore, patient satisfaction, as measured by patients, now directly affects CMS payments for over 3000 hospitals across the United States. This constitutes a large amount of money for most hospitals that operate on high revenue but have low profit margins. As such, the 2% at‐risk reimbursement may place many hospitals at financial risk that could be ameliorated with effective inpatient pain management.

In addition to its critical role in reimbursement to hospitals, patient satisfaction with pain management is also integrally related to providing patient‐centered care. As such, patient satisfaction with pain management is considered a critical element of various models of the patient‐centered approach to providing medical care. Although a medical inpatient team can assess objective signs of pain, patient‐centric pain measurements are paramount in understanding the pain experience of patients and providing adequate pain management care. Moreover, patients, doctors, payers of medical services, and now CMS increasingly regard a patient‐centered approach to medical care as crucial for the delivery of high‐quality care.

HCAHPS survey sampling represents an excellent opportunity to help assess current gaps in patient‐centered clinical care. However, ecological factors, such as county‐level demographics and hospital size (eg, bed number), are known to influence health outcomes but have not been adequately studied in pain management patient satisfaction.[7] Hospital and county‐level factors may influence the degree to which patients experience patient‐centered pain management care. For instance, most patient satisfaction scores are worse in urban areas.[8, 9] These disparities in patient satisfaction scores could be associated with population density, greater ethnic diversity or nonEnglish‐speaking individuals, or number of hospital beds.

The US Census demographics and hospital‐bed number provide a concurrent measure that can be used across the country to estimate hospital ecology. This study evaluated the influence of county‐level demographic and structural factors (ie, hospital beds) on patient satisfaction with hospital pain management in all HCAHPS‐participating hospitals across the United States. We hypothesized that demographic diversity, higher population density, and higher numbers of hospital beds would predict lower levels of patient satisfaction with inpatient pain management.

METHODS

Data Collection: County‐Level Predictors

Publically available data were obtained from the American Hospital Directory[10] and United States Census Bureau[11] websites. Twenty US Census data categories were selected a priori by their clinical relevance to influence pain management perception out of the 50 publically reported US Census categories. Final variables utilized in regression modeling are listed under the Variable column in Table 1. Covariate correlation coefficients were all under 0.7, indicating a lack of significant colinearity.

| Variable | Median Value (SD) | Range | Regression Coefficient (SE) | t Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| African American alone, % | 5.6% (13.8%) | 0%85.4% | 0.02 (00) | 3.609* |

| White alone, % | 86.2% (15.8%) | 5.3%99.0% | 0.06 (0.01) | 6.661* |

| Per capita income | $24,499 ($6,419) | $7,887$61,290 | 0.00 (0.00) | 7.561* |

| With bachelor's degree, % | 22.0% (10.1%) | 6.3%70.7% | 0.06 (0.01) | 7.348* |

| Population 18 years of age, % | 23.2% (3.1%) | 8.3%40.6% | 0.18 (0.05) | 3.498* |

| With a high school degree, % | 86.0% (6.4%) | 46.3%98.6% | 0.02 (0.01) | 1.424 |

| Population change over 1 year, % | 0.7% (2.2%) | 18.1%25.6% | 0.25 (0.04) | 5.645* |

| Same house over 1 year, % | 85.4% (4.2%) | 57.1%98.0% | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.493 |

| White alone (not Hispanic), % | 75.2% (21.8%) | 3.2%98.4% | 0.05(0.00) | 12.077* |

| Household size | 2.52 (0.3) | 1.924.77 | 2.266 (0.36) | 6.283* |

| Population county | 105,937 (1,524,223) | 1,1609,818,605 | 0.00 (0.00) | 13.117* |

| Average travel time to work, min | 23 (5.0) | 642.5 | 0.21 (0.02) | 11.071* |

| NonEnglish speaking, % | 8.6% (15.1%) | 0.2%95.9% | 0.08 (0.01) | 13.843* |

| Total female, % | 50.7% (1.6%) | 34.4%57.0% | 0.44 (0.06) | 7.489* |

| Population 65 years old, % | 14.7% (4.1%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.06 (0.02) | 2.697 |

| Population in poverty, % | 14.7% (5.6%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.02 (0.02) | 1.01 |

| Population density | 138.7 (4,534) | 0.369,467 | 0.73 (0.05) | 15.734* |

| Foreign born, % | 4.9% (9.3%) | 0%51.2% | 0.15 (0.01) | 16.775* |

| Median household income | $46,880 ($12,868) | $20,206$120,096 | 0.00 (0.00) | 6.052* |

| No. of hospital beds | 103 (193) | 22,259 | 0.01 (0.00) | 15.403* |

Data Collection: Patient Satisfaction With Pain Management

Pain management was measured using the HCAHPS survey pain management dimension by calculating the percentage of patient responders who said their pain was always controlled. HCAHPS data are publically available on the CMS Hospital Compare website.[6] It contains 32 questions that comprise 10 evaluative measures. It is provided to a random sample of patients across the United States throughout the year at 48 hours to 6 weeks after discharge from the hospital.

Analytic Plan

HCAHPS and US Census datasets were analyzed to assess their distribution curves. The population density variable was converted to a logarithmic scale to account for its skewed distribution and long tail in the area of low population density. Data were subsequently merged into an Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) spreadsheet using the VLOOKUP function such that relevant 2010 census county data were added to each hospital's HCAHPS data.

Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine which US Census categories were significant predictors for patient satisfaction with pain management. All significant predictors were then included in a multivariate model, which predicted for patient satisfaction with pain management. All analyses were 2‐tailed, and statistical significance was set at = 0.05.

RESULTS

Complete HCAHPS scores were obtained from 3907 hospitals out of a total of 4621 US hospitals (85%). The majority of hospitals (73.8%, n = 2884) collected over 300 surveys, fewer (n = 696) collected 100 to 299 surveys, and a small number of hospitals (n = 327) collected less than 100 surveys. Based on the most conservative estimate, results were available from at least 934,800 individual surveys. Missing HCAHPS hospital data averaged 13.4 (standard deviation [SD] = 12.2) hospitals per state. County‐level data were obtained from all 3144 county or county equivalents across the United States (100%).

Bivariate Analyses

Univariate regression indicated a significant association between pain management patient satisfaction and most county‐level demographic variables and number of hospital beds.

Multivariate Analyses

A multivariate linear regression model was run in which 20 county‐level demographic and hospital factors were examined as predictors of patient satisfaction with pain management. The model, which examined county‐level predictors of pain management, explained 12% of the variability in patients' ratings of pain management (R2 = 0.124, P 0.0001). A total of 8 out of the 20 US Census variables were statistically significant predictors of pain management (Table 2). African American and white race were most strongly associated with higher ratings of patient satisfaction with pain management (ie, by partial coefficient and statistical significance). Number of hospital beds, percent foreign born, population density, and female gender were most strongly related to lower ratings of patient satisfaction with pain management.

| Variable | Median Value (SD) | Range | Regression Coefficient (SE) | t Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| African American alone, % | 5.6% (13.8%) | 0%85.4% | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.23 | 7.104* |

| White alone, % | 86.2% (15.8%) | 5.3%99.0% | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.23 | 6.953* |

| Per capita income | $24,499 ($6,419) | $7,887$61,290 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.22 | 2.885 |

| With bachelor's degree, % | 22.0% (10.1%) | 6.3%70.7% | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.10 | 1.401 |

| Population 18 years old, % | 23.2% (3.1%) | 8.3%40.6% | 0.18 (0.05) | 0.08 | 3.498* |

| With a high school degree, % | 86.0% (6.4%) | 46.3%98.6% | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 | 1.424 |

| Population change over 1 year, % | 0.7% (2.2%) | 18.1%25.6% | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.01 | 1.986 |

| Same house over 1 year, % | 85.4% (4.2%) | 57.1%98.0% | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 | 0.493 |

| White alone (not Hispanic), % | 75.2% (21.8%) | 3.2%98.4% | 0.02(0.00) | 0.01 | 0.740 |

| Household size | 2.52 (0.3) | 1.924.77 | 0.92 (0.80) | 0.03 | 1.145 |

| Population county | 105,937 (1,524,223) | 1,1609,818,605 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.03 | 1.495 |

| Average travel time to work, min | 23 (5.0) | 642.5 | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.06 | 3.054 |

| NonEnglish speaking, % | 8.6% (15.1%) | 0.2%95.9% | 0.00 (0.03) | 0.06 | 0.028 |

| Total female, % | 50.7% (1.6%) | 34.4%57.0% | 0.23 (0.07) | 0.06 | 3.158 |

| Population 65 years old, % | 14.7% (4.1%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.10 (0.04) | 0.07 | 2.411 |

| Population in poverty, % | 14.7% (5.6%) | 5.8%49.3% | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.08 | 1.01 |

| Population density | 138.7 (4,534) | 0.369,467 | 0.24 (0.09) | 0.08 | 2.823 |

| Foreign born, % | 4.9% (9.3%) | 0%51.2% | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.12 | 4.906* |

| Median household income | $46,880 ($12,868) | $20,206‐$120,096 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.16 | 2.599 |

| No. of hospital beds | 103 (193) | 22,259 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.16 | 9.167* |

| Model statistics | F(1, 9) = 62.222, P 0.001 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.124 | ||||

DISCUSSION

By utilizing county‐level demographic data and the HCAHPS survey measures from across the United States, this study provides a representative sample of US hospitals that can be used to define ecological trends in patient satisfaction with pain management. This statistical model demonstrates the nonrandom variability of pain management satisfaction across the United States, even after CMS patient‐mix adjustment. Although the quality of pain management may be increasing by some reports, our present results indicate that pain management satisfaction is not equitable with the rest of the country among select groups of patients (eg, foreign born, female gender, areas of long travel times to work) or in certain care settings (eg, larger hospitals, population dense areas). These data suggest that areas of pain management may lack in quality compared to pain management across the entire US as a whole. This is consistent with the increasingly recognized contribution of multiple nonmedical determinates to health outcomes.[12] These results demonstrate the overall magnitude of healthcare disparity in the United States, and are particularly concerning because African Americans and Hispanics tend to rate overall satisfaction higher than Caucasians in other studies.[13, 14] The same minority reporting bias may be reflected in HCAHPS results. These patients may be reporting higher pain management satisfaction that is not consistent with the level of care they received, as studies have consistently indicated worse pain management delivery for racial and ethnic minorities.[15]

The present findings reveal structural (eg, hospital beds) and demographic (eg, population density, foreign born) gaps in satisfaction with pain management. An effort to improve pain management for all people in the heterogeneous makeup of the United States is an enormous challenge. However, change may be forthcoming, as Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing draws attention pain practice inequities in real time. Although several of the significant explanatory variables cannot be modified (eg, size of hospital, urban setting, patients served), pain management delivery should receive extra attention in hospitals with those characteristics. Pain management delivery in large, urban hospitals that serve foreign‐born patients may be improved with focused multilevel interventions. Future research should examine these inequities further and develop multilevel interventions that target hospitals in at‐risk areas with the aim of lessening disparities in hospital‐based pain management.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient‐centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267.

- , , , . Patient perception of pain care in hospitals in the United States. J Pain Res. 2009;2:157–164.

- , , , , . Patient perception of pain care in the United States: a 5‐year comparative analysis of hospital consumer assessment of health care providers and systems. Pain Physician. 2014;17(5):369–377.

- , , , , . Assessing the relationship between the level of pain control and patient satisfaction. J Pain Res. 2013;6:683–689.

- H.R.3590—Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th‐congress/house‐bill/3590. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare 55(1):125–139.

- , . Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342–343.

- , , , . Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–1931.

- American Hospital Directory. Hospital statistics by state. Available at: http://www.ahd.com/state_statistics.html. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- United States Census Bureau. Download center. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/download_center.xhtml. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Health policy brief: the relative contribution of multiple determinants to health outcomes. Health Affairs website. Available at: http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=123. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- , , , , . Racial and ethnic differences in patient assessments of interactions with providers: disparities or measurement biases? Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(2):109–114.

- , , , , . Survey response style and differential use of CAHPS rating scales by Hispanics. Med Care. 2008;46(9):963–968.

- Institute of Medicine. Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

- , , , et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient‐centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267.

- , , , . Patient perception of pain care in hospitals in the United States. J Pain Res. 2009;2:157–164.

- , , , , . Patient perception of pain care in the United States: a 5‐year comparative analysis of hospital consumer assessment of health care providers and systems. Pain Physician. 2014;17(5):369–377.

- , , , , . Assessing the relationship between the level of pain control and patient satisfaction. J Pain Res. 2013;6:683–689.

- H.R.3590—Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th‐congress/house‐bill/3590. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare 55(1):125–139.

- , . Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342–343.

- , , , . Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–1931.

- American Hospital Directory. Hospital statistics by state. Available at: http://www.ahd.com/state_statistics.html. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- United States Census Bureau. Download center. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/download_center.xhtml. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Health policy brief: the relative contribution of multiple determinants to health outcomes. Health Affairs website. Available at: http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=123. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- , , , , . Racial and ethnic differences in patient assessments of interactions with providers: disparities or measurement biases? Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(2):109–114.

- , , , , . Survey response style and differential use of CAHPS rating scales by Hispanics. Med Care. 2008;46(9):963–968.

- Institute of Medicine. Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

Delirium Screening in Older Patients

Delirium is a rapidly developing, fluctuating disturbance in consciousness, caused by a medical condition. The diagnosis of delirium is often missed, potentiating negative outcomes.[1, 2] Regular delirium screening by nurses results in increased recognition and treatment.[3] Although multiple screening tools exist, many are cumbersome to execute. Efforts have been made to shorten them, but although the screening tools may predict adverse outcomes, there are concerns about their specificity.[1, 2, 4, 5, 6] The Delirium Observation Screening Scale[7] (DOS) is a brief screening tool based on observation. It has been validated in several patient populations, but no published studies have taken place in the United States or have focused on an older, general medicine, inpatient population. Given the low numbers of patients in earlier validation studies, the effectiveness of the DOS for screening hospitalized, older patients is not yet fully established.

This study aimed to determine the ability of the DOS to screen hospitalized, older patients for delirium compared to a validated delirium diagnostic tool, the Delirium Rating Scale‐Revised‐98 (DRS‐R‐98).[8] In addition, DOS acceptability, ease of use, and benefit were explored by surveying nurses.

METHODS

Participants

After institutional review board approval, participants were selected by convenience sample from general medicine inpatients at a large, tertiary care, academic hospital. Eligible patients were age 65 years or older, admitted to a medicine inpatient unit, and spoke English. If participants were unable to consent, consent was obtained from the participant's legally authorized representative.

Delirium Observation Screening Scale

The DOS is a 13‐point screen for delirium, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV delirium criteria, designed to be completed by a nurse (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). Responses are dichotomous. Scores 3 were considered positive delirium screens.[7]

Nurses on medicine units attended educational in‐services on delirium recognition and use of the DOS. The DOS was embedded in the electronic medical record (EMR) and nurses are electronically prompted to chart DOS results every 12 hours for patients, age 65 years or older. Nursing staff utilized the DOS for 1 year prior to study start.

DRS‐R‐98

The DRS‐R‐98 was used as the study reference standard.[8] Scores 15 are indicative of delirium.[9] All assessments were performed by a medical student (K.G.) trained to administer the DRS‐R‐98.

Data Collection

After consent, hospitalized participants were evaluated daily (MondayFriday) using the DRS‐R‐98. Enrollment took place over a 10‐week period. Nurses and researchers were blinded to other delirium assessment results until after participant discharge. Following discharge, additional data were collected from the EMR: age, gender, cognitive comorbidities, and nurse‐charted DOS score. Cognitive comorbidities were classified as no impairment, dementia, or cognitive impairment based on the problem list and admission note. A psychiatrist (M.W.) confirmed questions of cognitive impairment.

The DOS score closest in time, within 24 hours of DRS‐R‐98 assessment, was used for comparison. If a DOS score was not charted within 24 hours of the DRS‐R‐98 evaluation, that assessment was excluded. Partial DRS‐R‐98 assessments were included only if there was enough information to classify a subject as delirious or not.

Nursing Survey

A 13‐question nursing survey was developed and consisted of demographic, Likert‐style, and multiple‐choice questions, with opportunities for open‐ended responses (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article). Survey design followed similar surveys investigating staff experiences and clinical functionality of other brief delirium screening tools, such as the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit.[10, 11] The survey was distributed by e‐mail to 435 nurses on 16 units. Coffee gift cards were raffled as participation incentive.

Statistical Analysis

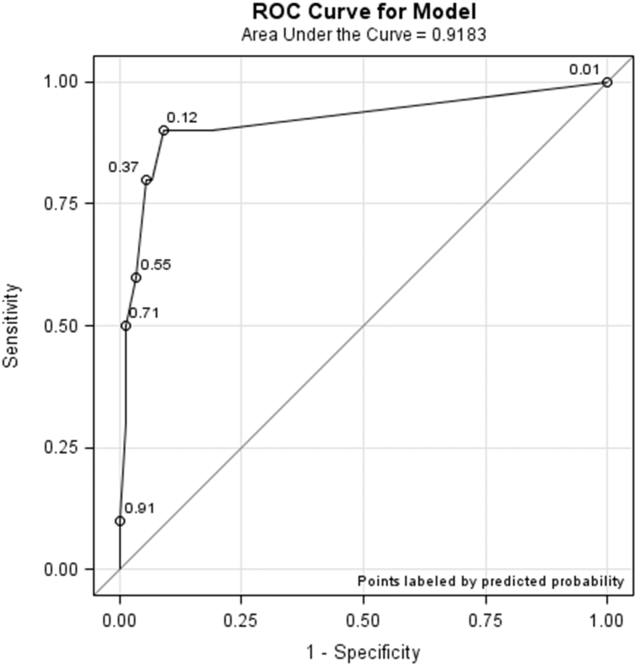

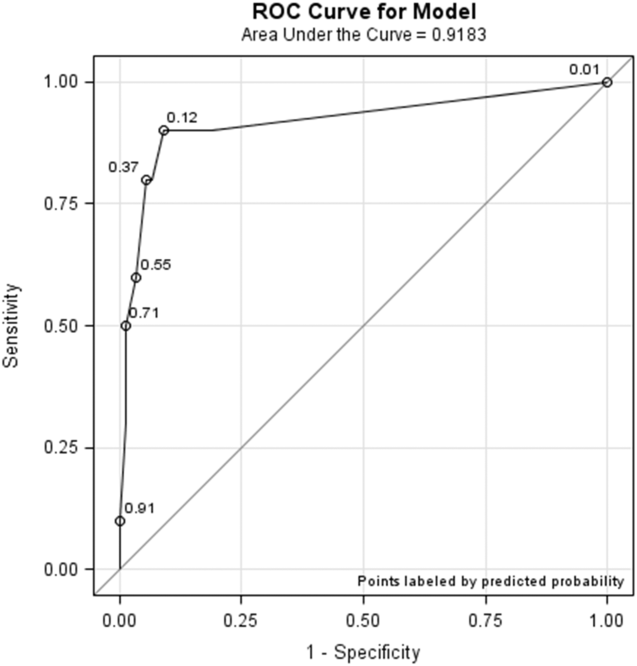

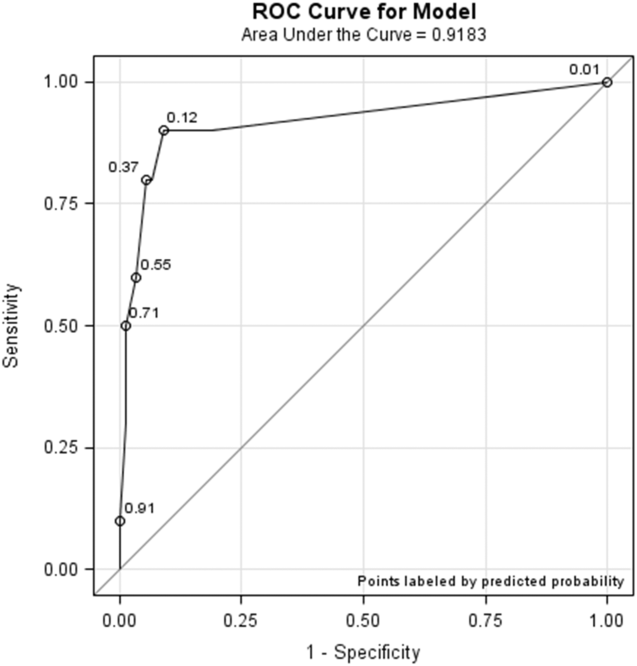

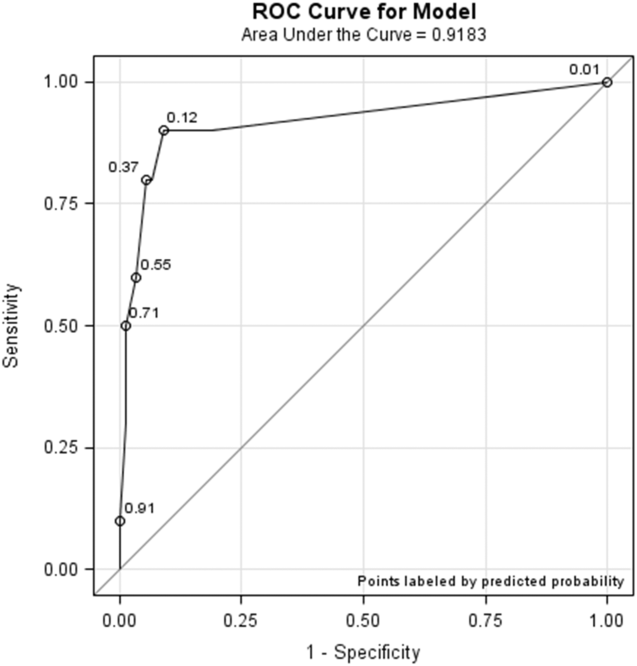

Statistical analysis was completed using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY) and SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) software. DOS results were compared to the DRS‐R‐98, and validity statistics were calculated for delirium. Confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper‐Pearson method for binomial data. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient between DOS and DRS‐98 score was calculated. PROC LOGISTIC (SAS Institute, Inc.) modeled the relationship between positive DOS screens and delirium and created a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using continuous DOS score to predict delirium. Because these models did not control for multiple observations per individual, PROC GENMOD (SAS Institute, Inc.) was used to confirm the relationship between a positive DOS screen and delirium using a marginal logistic regression model accounting for repeated measures. In addition, we selected 10 random samples of 1 observation per person, and validity statistics were calculated for each sample.

The nursing survey results were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Open‐ended comments were reviewed in aggregate.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Fifty‐four participants enrolled in the study. Fifty‐three were able to complete 1 DRS‐R‐98 and comprise the study sample (Table 1). Participants completed 1 to 5 daily DRS‐R‐98 assessments (mean, 1.94; standard deviation [SD], 0.90; mean length of admission, 6.06 days). Of the 105 DRS‐R‐98 assessments, 101 were classifiable for delirium. Of the 101 DRS‐R‐98 assessments classifiable for delirium, 100 had a corresponding DOS score within 24 hours. Participant characteristics are listed in Table 1. Eight of the 53 participants (15%) had at least 1 positive DRS‐R‐98. Overall, 10 of the 101 delirium assessments diagnosed delirium (DRS‐R‐98 score 15).

| Characteristic | No Delirium, n = 45 | Delirium, n = 8a |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age, y | ||

| 6574, n = 26 | 22 | 4 |

| 7584, n = 15 | 13 | 2 |

| 85+, n = 12 | 10 | 2 |

| Age, y, mean (SD) [range] | 77 (10) [6592] | 76 (8.6) [6592] |

| Gender | ||

| Female, n = 33 | 28 | 5 |

| Male, n = 20 | 17 | 3 |

| Cognitive status per chart | ||

| No impairment, n = 45 | 43 | 2 |

| Cognitive impairment without dementia, n = 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Dementia, n = 3 | 1 | 2 |

DOS Validity

The mean and standard deviation of delirium screening scores are as follows: DRS‐R‐98 (mean, 6.13; SD, 4.74; range, 020) and DOS (mean, 1.22; SD, 2.37; range, 09). The Spearman correlation coefficient between DOS and DRS‐R‐98 scores was 0.58. DOS had a sensitivity of 90% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 56%‐100%) and specificity of 91% (95% CI: 83%‐96%) compared to the DRS‐98‐R standard. There was only 1 false negative DOS screen out of 83 negative assessments (negative predictive value = 99%, 95% CI: 93%‐100%). Out of the 17 positive assessments, 9 were true positives (positive predictive value = 53%, 95% CI: 28%‐77%), and 7 scored in the subsyndromal range for delirium (DRS‐R‐98 score 814).

In analyses using 10 samples, with 1 randomly selected observation per person, the mean sensitivity was 84.6%, ranging from 80% (95% CI: 28%‐99%) to 87.5% (95% CI: 47%‐100%). The mean specificity in these samples was 92%, ranging from 87% (95% CI: 74%‐95%) to 96% (95% CI: 85%‐99%).

Logistic Regression Models

All models confirmed that positive DOS screens significantly predicted delirium. The traditional logistic regression model produced an odds ratio (OR) estimate of 92 (95% CI: 10‐824, P 0.0001) for a positive DOS screen predicting delirium. The marginal logistic regression model accounting for repeated measures produced a consistent estimate (OR: 93, 95% CI: 11‐800, P 0.0001). Continuous DOS scores predicted delirium (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.5‐2.9, P 0.0001), and the ROC curve supported the cutoff of DOS 3, corresponding to a predicted probability of 0.12 (Figure 1).

Nursing Survey

The nursing survey had a response rate of 23% (N = 98). The most robust results related to DOS administration were 87% (N = 83) of nurses were confident in DOS administration, 92% (N = 86) could complete the DOS in under 3 minutes, and 79% (N = 74) agreed that performing the DOS is easy. There was less agreement on the value of the DOS; 37% agreed that the DOS is worth the time to perform, 25% agreed that the DOS enhances patient care, and 36% agreed that the DOS provides valuable information for patient care. Over half the nurses (55%) reported that they perform the DOS 75% to 100% of the prompted times, and 62% stated if the DOS was no longer required, they would not use it. Open‐ended questions generated a wide range of responses, from supportive to critical of delirium screening and the DOS (see Supporting Information, Appendix 3, in the online version of this article).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the effectiveness, efficiency, and ease of use of the DOS as a delirium screening tool. The DOS exhibited high sensitivity (90%) and specificity (91%). Similar to previous findings, the positive predictive value was only 53%, but the negative predictive value was 99%.[12] These results support that the DOS is consistently able to rule out delirium, with only 1 false negative in this study.

Nursing responses regarding user‐friendliness are consistent with other studies; however, there was a knowledge gap related to how positive delirium screens can inform and change care for patients.[7] Education is a known barrier to integrating delirium screening tools secondary to the need for regular and extensive education, frequent reminders to screen, and regular evaluations of assessment quality.[11, 13, 14, 15] Developing guidelines for responding to positive DOS screens and documenting its impact on care may incentivize use.

Study strengths include strong evaluator consistency, blinding of evaluator and nurses, and responses from a broad range of nurses (14 of 16 units represented). Additionally, this study demonstrated the efficacy and ease of use of an EMR‐prompted delirium screen. However, this study had several limitations, including a small sample size and a low incidence of delirium. The lower incidence is likely secondary to selection bias that resulted from difficulty consenting delirious subjects. The discordant time between DOS and DRS‐R‐98 assessments may have also influenced results; however, inclusion of data from the previous 8 to 24 hours in both tools makes the temporal separation of assessments less impactful.

The ability of the DOS to accurately identify patients at high risk of delirium is useful for healthcare staff. Future work will include nurse and physician education to emphasize delirium understanding, the importance of regular screening, and the use of nonpharmacological interventions. Additional studies will include examination of the interventions and outcomes of patients who screen positive for delirium to determine the long‐term impact of delirium screening.

Acknowledgements

The study authors would like to thank the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, the Department of Family Medicine, and the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics nursing managers and nursing staff.

Disclosures

This study was funded by the Summer Research Fellowship program sponsored by the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine. Drs. Weckmann and Carnahan were supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration, Iowa Geriatric Education Center (UB4 HP19054) as well as the US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ 1 R18 HS022666‐01).

- , , . An intervention to reduce delirium in care homes. Nurs Older People. 2010;22(4):16–21.

- , , , et al. Assessment of delirium in the intensive care unit: nursing practices and perceptions. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17(6):555–565.

- , , , et al. Delirium and sedation recognition using validated instruments: reliability of bedside intensive care unit nursing assessments from 2007 to 2010. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(suppl 2):S249–S255.

- , , , et al. Preliminary development of an ultrabrief two‐item bedside test for delirium. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):645–650.

- , , , et al. The association between an ultrabrief cognitive screening in older adults and hospital outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):651–657.

- , , , et al. Comparison of mental‐status scales for predicting mortality on the general wards. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):658–663.

- , , . The Delirium Observation Screening Scale: a screening instrument for delirium. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2003;17(1):31–50.

- . Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale‐Revised‐98: comparison with the Delirium Rating Scale and the Cognitive Test for Delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13(2):229–242.

- , , , et al. Factor analysis of the Colombian translation of the Delirium Rating Scale (DRS), Revised‐98. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(3):255–262.

- , , , et al. Implementation, reliability testing, and compliance monitoring of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit in trauma patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(7):1263–1268.

- , , , et al. Limitations and practicalities of CAM‐ICU implementation, a delirium scoring system, in a Dutch intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2009;25(5):242–249.

- , . The Neecham Confusion Scale and the Delirium Observation Screening Scale: capacity to discriminate and ease of use in clinical practice. BMC Nurs. 2007;6:3.

- , , . Early recognition of delirium: review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(6):721–729.

- , , , et al. Impact of a delirium screening tool and multifaceted education on nurses' knowledge of delirium and ability to evaluate it correctly. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21(1):e1–e11.

- , , . Optimising the recognition of delirium in the intensive care unit. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2012;26(3):385–393.

Delirium is a rapidly developing, fluctuating disturbance in consciousness, caused by a medical condition. The diagnosis of delirium is often missed, potentiating negative outcomes.[1, 2] Regular delirium screening by nurses results in increased recognition and treatment.[3] Although multiple screening tools exist, many are cumbersome to execute. Efforts have been made to shorten them, but although the screening tools may predict adverse outcomes, there are concerns about their specificity.[1, 2, 4, 5, 6] The Delirium Observation Screening Scale[7] (DOS) is a brief screening tool based on observation. It has been validated in several patient populations, but no published studies have taken place in the United States or have focused on an older, general medicine, inpatient population. Given the low numbers of patients in earlier validation studies, the effectiveness of the DOS for screening hospitalized, older patients is not yet fully established.

This study aimed to determine the ability of the DOS to screen hospitalized, older patients for delirium compared to a validated delirium diagnostic tool, the Delirium Rating Scale‐Revised‐98 (DRS‐R‐98).[8] In addition, DOS acceptability, ease of use, and benefit were explored by surveying nurses.

METHODS

Participants

After institutional review board approval, participants were selected by convenience sample from general medicine inpatients at a large, tertiary care, academic hospital. Eligible patients were age 65 years or older, admitted to a medicine inpatient unit, and spoke English. If participants were unable to consent, consent was obtained from the participant's legally authorized representative.

Delirium Observation Screening Scale

The DOS is a 13‐point screen for delirium, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV delirium criteria, designed to be completed by a nurse (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). Responses are dichotomous. Scores 3 were considered positive delirium screens.[7]

Nurses on medicine units attended educational in‐services on delirium recognition and use of the DOS. The DOS was embedded in the electronic medical record (EMR) and nurses are electronically prompted to chart DOS results every 12 hours for patients, age 65 years or older. Nursing staff utilized the DOS for 1 year prior to study start.

DRS‐R‐98

The DRS‐R‐98 was used as the study reference standard.[8] Scores 15 are indicative of delirium.[9] All assessments were performed by a medical student (K.G.) trained to administer the DRS‐R‐98.

Data Collection

After consent, hospitalized participants were evaluated daily (MondayFriday) using the DRS‐R‐98. Enrollment took place over a 10‐week period. Nurses and researchers were blinded to other delirium assessment results until after participant discharge. Following discharge, additional data were collected from the EMR: age, gender, cognitive comorbidities, and nurse‐charted DOS score. Cognitive comorbidities were classified as no impairment, dementia, or cognitive impairment based on the problem list and admission note. A psychiatrist (M.W.) confirmed questions of cognitive impairment.

The DOS score closest in time, within 24 hours of DRS‐R‐98 assessment, was used for comparison. If a DOS score was not charted within 24 hours of the DRS‐R‐98 evaluation, that assessment was excluded. Partial DRS‐R‐98 assessments were included only if there was enough information to classify a subject as delirious or not.

Nursing Survey

A 13‐question nursing survey was developed and consisted of demographic, Likert‐style, and multiple‐choice questions, with opportunities for open‐ended responses (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article). Survey design followed similar surveys investigating staff experiences and clinical functionality of other brief delirium screening tools, such as the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit.[10, 11] The survey was distributed by e‐mail to 435 nurses on 16 units. Coffee gift cards were raffled as participation incentive.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was completed using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY) and SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) software. DOS results were compared to the DRS‐R‐98, and validity statistics were calculated for delirium. Confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper‐Pearson method for binomial data. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient between DOS and DRS‐98 score was calculated. PROC LOGISTIC (SAS Institute, Inc.) modeled the relationship between positive DOS screens and delirium and created a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using continuous DOS score to predict delirium. Because these models did not control for multiple observations per individual, PROC GENMOD (SAS Institute, Inc.) was used to confirm the relationship between a positive DOS screen and delirium using a marginal logistic regression model accounting for repeated measures. In addition, we selected 10 random samples of 1 observation per person, and validity statistics were calculated for each sample.

The nursing survey results were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Open‐ended comments were reviewed in aggregate.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Fifty‐four participants enrolled in the study. Fifty‐three were able to complete 1 DRS‐R‐98 and comprise the study sample (Table 1). Participants completed 1 to 5 daily DRS‐R‐98 assessments (mean, 1.94; standard deviation [SD], 0.90; mean length of admission, 6.06 days). Of the 105 DRS‐R‐98 assessments, 101 were classifiable for delirium. Of the 101 DRS‐R‐98 assessments classifiable for delirium, 100 had a corresponding DOS score within 24 hours. Participant characteristics are listed in Table 1. Eight of the 53 participants (15%) had at least 1 positive DRS‐R‐98. Overall, 10 of the 101 delirium assessments diagnosed delirium (DRS‐R‐98 score 15).

| Characteristic | No Delirium, n = 45 | Delirium, n = 8a |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age, y | ||

| 6574, n = 26 | 22 | 4 |

| 7584, n = 15 | 13 | 2 |

| 85+, n = 12 | 10 | 2 |

| Age, y, mean (SD) [range] | 77 (10) [6592] | 76 (8.6) [6592] |

| Gender | ||

| Female, n = 33 | 28 | 5 |

| Male, n = 20 | 17 | 3 |

| Cognitive status per chart | ||

| No impairment, n = 45 | 43 | 2 |

| Cognitive impairment without dementia, n = 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Dementia, n = 3 | 1 | 2 |

DOS Validity

The mean and standard deviation of delirium screening scores are as follows: DRS‐R‐98 (mean, 6.13; SD, 4.74; range, 020) and DOS (mean, 1.22; SD, 2.37; range, 09). The Spearman correlation coefficient between DOS and DRS‐R‐98 scores was 0.58. DOS had a sensitivity of 90% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 56%‐100%) and specificity of 91% (95% CI: 83%‐96%) compared to the DRS‐98‐R standard. There was only 1 false negative DOS screen out of 83 negative assessments (negative predictive value = 99%, 95% CI: 93%‐100%). Out of the 17 positive assessments, 9 were true positives (positive predictive value = 53%, 95% CI: 28%‐77%), and 7 scored in the subsyndromal range for delirium (DRS‐R‐98 score 814).

In analyses using 10 samples, with 1 randomly selected observation per person, the mean sensitivity was 84.6%, ranging from 80% (95% CI: 28%‐99%) to 87.5% (95% CI: 47%‐100%). The mean specificity in these samples was 92%, ranging from 87% (95% CI: 74%‐95%) to 96% (95% CI: 85%‐99%).

Logistic Regression Models

All models confirmed that positive DOS screens significantly predicted delirium. The traditional logistic regression model produced an odds ratio (OR) estimate of 92 (95% CI: 10‐824, P 0.0001) for a positive DOS screen predicting delirium. The marginal logistic regression model accounting for repeated measures produced a consistent estimate (OR: 93, 95% CI: 11‐800, P 0.0001). Continuous DOS scores predicted delirium (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.5‐2.9, P 0.0001), and the ROC curve supported the cutoff of DOS 3, corresponding to a predicted probability of 0.12 (Figure 1).

Nursing Survey

The nursing survey had a response rate of 23% (N = 98). The most robust results related to DOS administration were 87% (N = 83) of nurses were confident in DOS administration, 92% (N = 86) could complete the DOS in under 3 minutes, and 79% (N = 74) agreed that performing the DOS is easy. There was less agreement on the value of the DOS; 37% agreed that the DOS is worth the time to perform, 25% agreed that the DOS enhances patient care, and 36% agreed that the DOS provides valuable information for patient care. Over half the nurses (55%) reported that they perform the DOS 75% to 100% of the prompted times, and 62% stated if the DOS was no longer required, they would not use it. Open‐ended questions generated a wide range of responses, from supportive to critical of delirium screening and the DOS (see Supporting Information, Appendix 3, in the online version of this article).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the effectiveness, efficiency, and ease of use of the DOS as a delirium screening tool. The DOS exhibited high sensitivity (90%) and specificity (91%). Similar to previous findings, the positive predictive value was only 53%, but the negative predictive value was 99%.[12] These results support that the DOS is consistently able to rule out delirium, with only 1 false negative in this study.

Nursing responses regarding user‐friendliness are consistent with other studies; however, there was a knowledge gap related to how positive delirium screens can inform and change care for patients.[7] Education is a known barrier to integrating delirium screening tools secondary to the need for regular and extensive education, frequent reminders to screen, and regular evaluations of assessment quality.[11, 13, 14, 15] Developing guidelines for responding to positive DOS screens and documenting its impact on care may incentivize use.

Study strengths include strong evaluator consistency, blinding of evaluator and nurses, and responses from a broad range of nurses (14 of 16 units represented). Additionally, this study demonstrated the efficacy and ease of use of an EMR‐prompted delirium screen. However, this study had several limitations, including a small sample size and a low incidence of delirium. The lower incidence is likely secondary to selection bias that resulted from difficulty consenting delirious subjects. The discordant time between DOS and DRS‐R‐98 assessments may have also influenced results; however, inclusion of data from the previous 8 to 24 hours in both tools makes the temporal separation of assessments less impactful.

The ability of the DOS to accurately identify patients at high risk of delirium is useful for healthcare staff. Future work will include nurse and physician education to emphasize delirium understanding, the importance of regular screening, and the use of nonpharmacological interventions. Additional studies will include examination of the interventions and outcomes of patients who screen positive for delirium to determine the long‐term impact of delirium screening.

Acknowledgements

The study authors would like to thank the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, the Department of Family Medicine, and the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics nursing managers and nursing staff.

Disclosures

This study was funded by the Summer Research Fellowship program sponsored by the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine. Drs. Weckmann and Carnahan were supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration, Iowa Geriatric Education Center (UB4 HP19054) as well as the US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ 1 R18 HS022666‐01).

Delirium is a rapidly developing, fluctuating disturbance in consciousness, caused by a medical condition. The diagnosis of delirium is often missed, potentiating negative outcomes.[1, 2] Regular delirium screening by nurses results in increased recognition and treatment.[3] Although multiple screening tools exist, many are cumbersome to execute. Efforts have been made to shorten them, but although the screening tools may predict adverse outcomes, there are concerns about their specificity.[1, 2, 4, 5, 6] The Delirium Observation Screening Scale[7] (DOS) is a brief screening tool based on observation. It has been validated in several patient populations, but no published studies have taken place in the United States or have focused on an older, general medicine, inpatient population. Given the low numbers of patients in earlier validation studies, the effectiveness of the DOS for screening hospitalized, older patients is not yet fully established.

This study aimed to determine the ability of the DOS to screen hospitalized, older patients for delirium compared to a validated delirium diagnostic tool, the Delirium Rating Scale‐Revised‐98 (DRS‐R‐98).[8] In addition, DOS acceptability, ease of use, and benefit were explored by surveying nurses.

METHODS

Participants

After institutional review board approval, participants were selected by convenience sample from general medicine inpatients at a large, tertiary care, academic hospital. Eligible patients were age 65 years or older, admitted to a medicine inpatient unit, and spoke English. If participants were unable to consent, consent was obtained from the participant's legally authorized representative.

Delirium Observation Screening Scale

The DOS is a 13‐point screen for delirium, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV delirium criteria, designed to be completed by a nurse (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). Responses are dichotomous. Scores 3 were considered positive delirium screens.[7]

Nurses on medicine units attended educational in‐services on delirium recognition and use of the DOS. The DOS was embedded in the electronic medical record (EMR) and nurses are electronically prompted to chart DOS results every 12 hours for patients, age 65 years or older. Nursing staff utilized the DOS for 1 year prior to study start.

DRS‐R‐98

The DRS‐R‐98 was used as the study reference standard.[8] Scores 15 are indicative of delirium.[9] All assessments were performed by a medical student (K.G.) trained to administer the DRS‐R‐98.

Data Collection