User login

Chagas Disease: Creeping into Family Practice in the United States

CE/CME No: CR-1611

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand the prevalence and risks of Chagas disease in the United States.

• Explain the pathophysiology of Chagas disease, including the vector and transmission routes of the disease.

• Describe the clinical presentation of both the acute and chronic forms of the disease and learn when to suspect an infection.

• Outline a plan for diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease.

• Educate women with Chagas disease about the risk of transmission for future offspring.

FACULTY

Jessica McDonald works in the Emergency Medicine Department at Dekalb Medical Center, Atlanta. Jill Mattingly is Academic Coordinator and Clinical Assistant Professor in the Physician Assistant Program at Mercer University, Atlanta.

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of November 2016.

Article begins on next page >>

Chagas disease, a parasitic infection, is increasingly being detected in the United States, most likely due to immigration from endemic countries in South and Central America. Approximately 300,000 persons in the US have chronic Chagas disease, and up to 30% of them will develop clinically evident cardiovascular and/or gastrointestinal disease. Here’s practical guidance to help you recognize the features of symptomatic Chagas disease and follow up with appropriate evaluation and management.

Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi.1 It is most commonly spread by triatomine bugs infected with T cruzi and is endemic in many parts of Mexico and Central and South America.2 Chagas disease was first described in 1909 by Brazilian physician Carlos Chagas.3 Since its discovery, it has often been considered a disease affecting only the poor living in endemic areas of Latin America. However, 6 million to 7 million people are infected with T cruzi worldwide, and estimates suggest that Mexico and the US rank third and seventh, respectively, in the number of persons with T cruzi infection in the Western Hemisphere.1,4

An estimated 300,000 persons in the US have Chagas disease; most of them are not aware that they are infected.5,6 The increasing presence of the disease in the US, which traditionally has been considered a nonendemic area, is due to immigration from endemic areas, with subsequent infections occurring through mechanisms that do not require contact with the triatomine vector (eg, congenital transmission).1 Between 1981 and 2005, more than 7 million people from T cruzi-endemic countries in Latin America moved to the US and became legal residents.3

Early detection and treatment of Chagas disease is important because up to 30% of patients with chronic infection will develop a heart disorder, which can range in severity from conduction system abnormalities to dilated cardiomyopathy.4 In some areas of southern Mexico, Chagas disease is the most common cause of dilated cardiomyopathy.1 Equally concerning is the fact that untreated mothers with Chagas disease can transmit T cruzi to their infants.1,3 An estimated 315 babies are born with congenital Chagas disease each year in the US, an incidence equivalent to that of phenylketonuria.7 It is estimated that congenital transmission is responsible for up to one-quarter of new infections worldwide.1 Unfortunately, obstetricians are not well informed about the risk factors for congenital Chagas disease, and very limited screening of at-risk women is performed. In a 2008 survey exploring health care providers’ knowledge of and understanding about Chagas disease, obstetricians and gynecologists had the greatest knowledge deficits about the disease, although considerable deficits were also seen among other specialties.1

KISSING BUG DISEASE: ETIOLOGY/PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

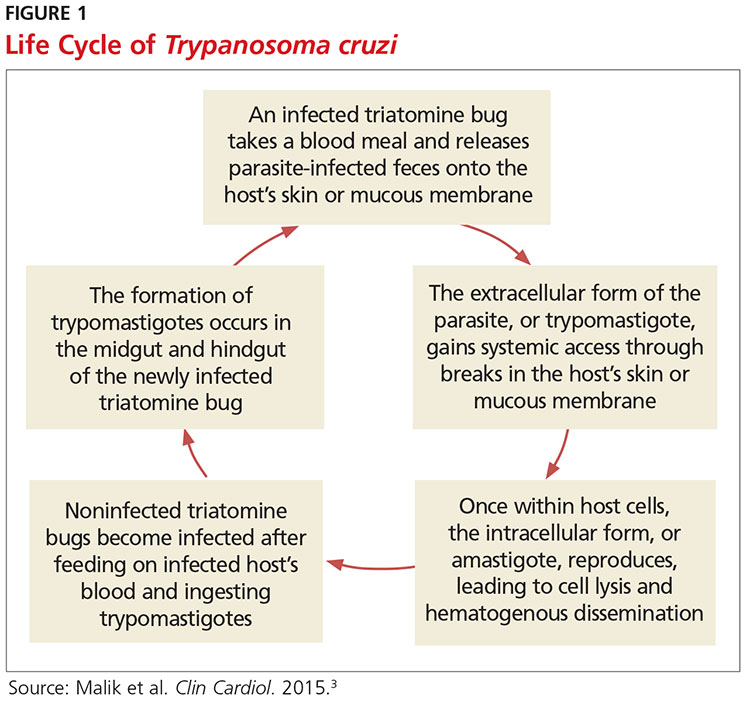

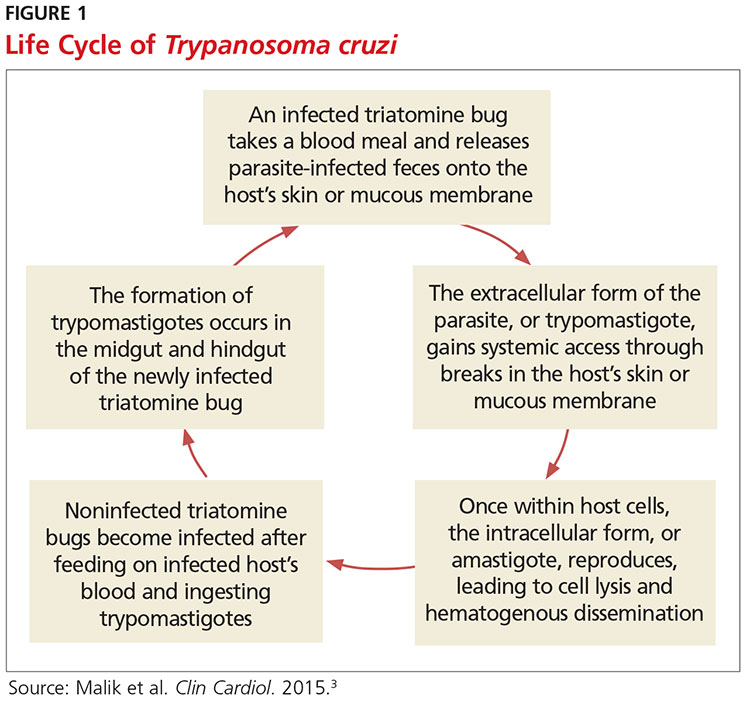

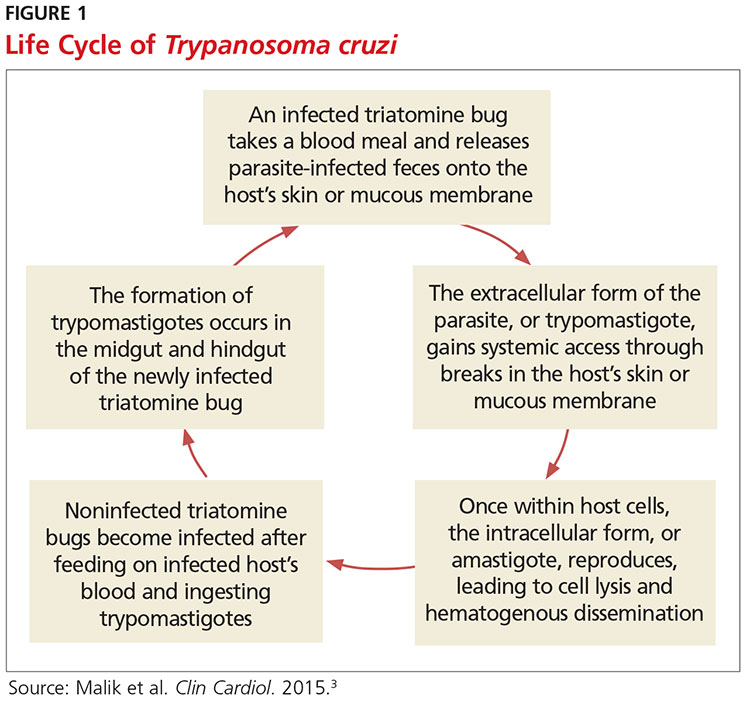

Exposure to the protozoan parasite T cruzi, the cause of Chagas disease, typically occurs following the bite of a triatomine bug. Also known as “kissing bugs” because they usually bite exposed areas of the skin such as the face, triatomine bugs feed on human blood, typically at night, and act as a vector for the parasite.8 The parasite lives in the feces and urine of the triatomine bugs and is excreted near the bite during or shortly after a blood meal. The bitten person will then unknowingly smear the infected feces into the bite wound, eyes, mouth, or any opening in the skin, which gives the parasites systemic access.4 Once in the host’s bloodstream, the parasite replicates in host cells, a process that ends in cell lysis and hematogenous spread. At this point, the parasites can be seen on peripheral blood smear. Noninfected triatomine insects become infected and continue the cycle when they feed on an infected human host (see Figure 1).3 Persons of lower socioeconomic status living in endemic areas in Latin America are at a higher risk for contracting Chagas disease because “kissing bugs” commonly live in wall or roof cracks of poorly built homes. Populations living in poverty are also at risk due to minimal access to health care and prenatal care.4 Transmission of T cruzi not involving triatomine vectors occurs congenitally or through blood transfusions, consumption of contaminated food, and organ donations.4

NATURAL HISTORY OF INFECTION AND PATIENT PRESENTATION

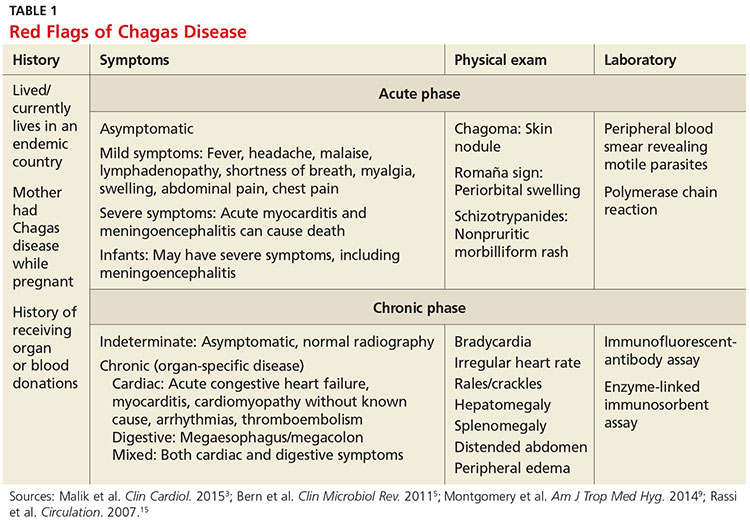

Acute phase

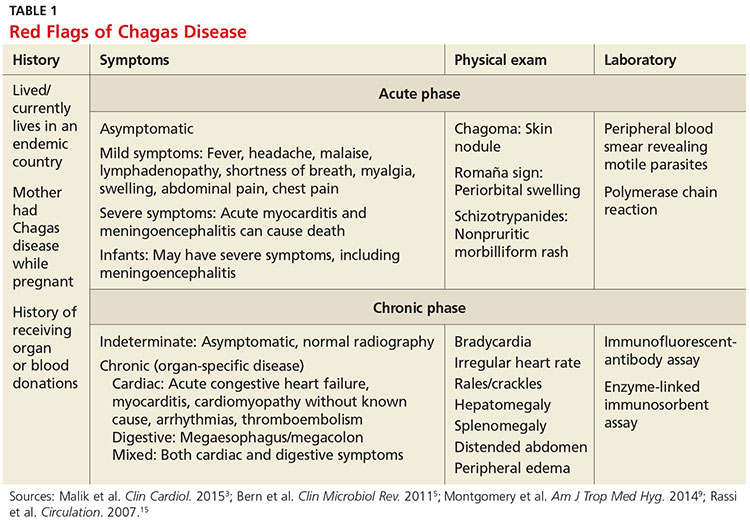

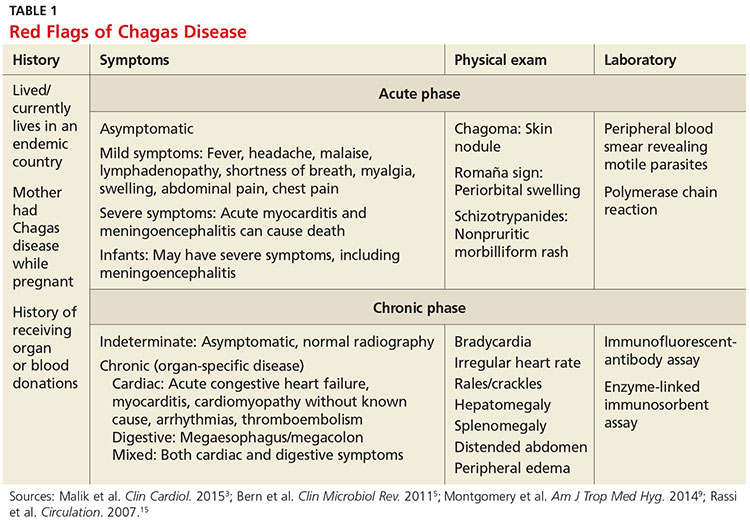

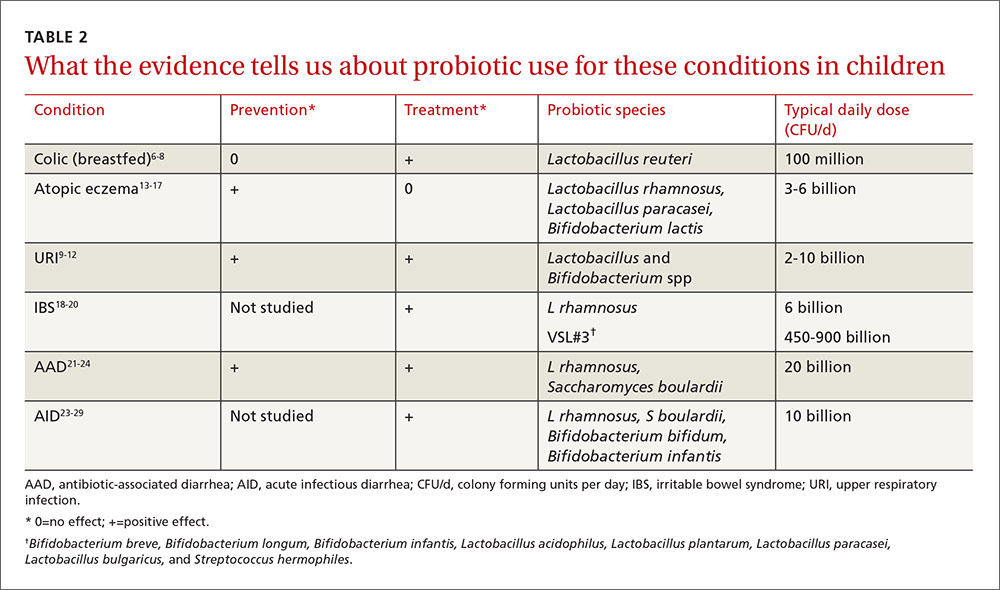

Infection with the T cruzi parasite is followed by an asymptomatic incubation period of one to two weeks, which is then followed by an acute phase that can last eight to 12 weeks.5 The acute phase is characterized by a large amount of parasites in the bloodstream (see Table 1). The patient is often asymptomatic but can have nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, lymphadenopathy, shortness of breath, myalgia, swelling, and abdominal or chest pain.4 Because symptoms during the acute phase are typically mild, many patients do not seek medical attention until they transition into the chronic phase.4 Infants are more likely to experience severe symptoms, including myocarditis or meningoencephalitis, and thus are more likely to present during the acute phase.9

If the patient acquired the infection through an organ transplant, the acute phase symptoms can be delayed, on average, up to 112 days.5 These patients will have more noticeable symptoms, including hepatosplenomegaly, myocarditis, and congestive heart failure. Due to the known risk for transmission through organ transplants, donors are often screened for Chagas disease. Unfortunately, this screening is selective and often inconsistent.5 Therefore, the presence of the previously mentioned symptoms in a person who recently received an organ transplant should raise suspicion of Chagas disease.5

Chronic phase

Patients not treated during the acute phase will pass into the chronic phase of Chagas disease.5 This may occur due to reactivation of T cruzi infection via immunosuppression.9 At this time, the previously asymptomatic patient will have typical signs and symptoms of chronic disease, along with nodules, panniculitis, and myocarditis.4,9,10 During the chronic phase, parasites are undetectable by microscopy, but the patient can still spread the disease to the vector as well as to others congenitally and through organ donation and blood transfusions.5,9

Patients with chronic T cruzi infection who remain without signs or symptoms of infection are considered to have the indeterminate form of chronic disease. Many patients will remain in the indeterminate form throughout their lives, but between 20% and 30% will progress to the determinate form of chronic disease over years to decades.3 The determinate form is characterized by clinically evident disease and is classically divided into cardiac Chagas disease and digestive Chagas disease.5 Symptoms of the chronic phase depend on the genotype of T cruzi that caused the infection. The AG genotype has a higher incidence of digestive disease.11

Cardiac Chagas disease is believed to occur due to parasite invasion and persistence in cardiac tissue, leading to immune-mediated myocardial injury.5 Chagas cardiomyopathy is characterized by chronic myocarditis affecting all cardiac chambers and disturbances in the electrical conduction system; patients also often develop apical aneurysms. Longstanding cardiac Chagas disease can lead to more serious complications, such as episodes of ventricular tachycardia, heart block, thromboembolic phenomena, severe bradycardia, dilated cardiomyopathy, and congestive heart failure. Patients may complain of presyncope, syncope, and episodes of palpitations. They are also at high risk for sudden cardiac death.5 Patients with cardiomyopathy or cardiac insufficiency secondary to Chagas disease have a worse prognosis than those with idiopathic cardiomyopathy or decompensated heart failure due to other etiologies.12

Less common than cardiac Chagas disease, digestive Chagas disease occurs mostly in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and parts of Peru and Brazil; it is rarely seen in northern South America, Central America, or Mexico.5 The parasite causes gastrointestinal symptoms by damaging intramural neurons, resulting in denervation of hollow viscera. Since it affects the esophagus and colon, patients may present with dysphagia, odynophagia, cough, reflux, weight loss, constipation, and abdominal pain.5

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION: A CRUCIAL STEP

The physical examination of a patient with suspected Chagas disease can be crucial to the diagnosis. As noted, there are often few specific symptoms or physical exam findings during the acute phase. However, in some patients, swelling and inflammation may be evident at the site of inoculation, often on the face or extremities. This finding is called a chagoma. The Romaña sign, characterized by painless unilateral swelling of the upper and lower eyelid, can also be seen if the infection occurred through the conjunctiva.5 A nonpruritic morbilliform rash, called schizotrypanides, may be a presenting symptom in patients with acute disease.13 Children younger than 2 years of age are at increased risk for a severe acute infection, with signs and symptoms of pericardial effusion, myocarditis, and meningoencephalitis. Children can also develop generalized edema and lymphadenopathy. Those children who develop severe manifestations during acute infection have an increased risk for mortality.5

Chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy may present with signs of left-sided heart failure (pulmonary edema, dyspnea at rest or exertion), biventricular heart failure (hepatomegaly, peripheral edema, jugular venous distention), or thromboembolic events to the brain, lower extremities, and lungs.13 Chronic chagasic megaesophagus may lead to weight loss, esophageal dysmotility, pneumonitis due to aspiration of food trapped in the esophagus and stomach, salivary gland enlargement, and erosive esophagitis, which increases the risk for esophageal cancer. Chronic chagasic megacolon can present as an intestinal obstruction, volvulus, abdominal distention, or fecaloma.13

Clinicians should be alert to the possibility of congenital T cruzi infection in children born to women who emigrated from an endemic area or who visited an area with a high prevalence of Chagas disease. Most newborns with T cruzi infection are asymptomatic, but in some cases a thorough neonatal exam can lead to the diagnosis. Manifestations of symptomatic congenital infection include hepatosplenomegaly, low birth weight, premature birth, and low Apgar scores.5 Lab tests may reveal thrombocytopenia and anemia. Neonates with severe disease may also have respiratory distress, meningoencephalitis, and gastrointestinal problems.5

LABORATORY WORK-UP

Laboratory work-up for Chagas disease depends on the provider’s awareness of the disease and its symptoms. All patients should undergo routine blood work, including complete blood count (CBC) with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and liver function tests to rule out other etiologies that manifest with similar symptoms. If the patient presents during the acute phase, microscopy of blood smears with Giemsa stain should be done to visualize the parasites. In the patient who presents during the chronic phase with cardiac symptoms, measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide, troponin, C-reactive protein, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate can be used to rule out other differential diagnoses. Electrocardiogram (ECG) may show a right bundle-branch block or left anterior fascicular block.5 Echocardiogram may show left ventricular wall motion abnormalities and/or cardiomyopathy with congestive heart failure.5,10 A work-up for digestive Chagas disease may include a barium swallow, kidney-ureter-bladder x-ray, or MRI/CT of the abdomen.14

DIAGNOSING ACUTE, CHRONIC, AND CONGENITAL CHAGAS

Accurate diagnosis of Chagas disease requires a thorough history and physical exam, as well as a high index of suspicion. Recent travel to an endemic area of Chagas disease in combination with the typical signs and symptoms—such as fever, headache, lymphadenopathy, shortness of breath, myalgia, swelling, and abdominal or chest pain—should prompt the provider to perform more specific tests.4 Inquiry about past medical history, blood transfusions, and surgeries is also imperative to make the correct diagnosis.5

The approach to diagnosis of Chagas disease depends on whether the patient presents during the acute or chronic phase. During the acute phase, the count of the trypomastigote, the mature extracellular form of the parasite T cruzi, is at its highest, making this the best time to obtain an accurate diagnosis if an infection is suspected.3 Microscopy of fresh preparations of anticoagulated blood or buffy coat may show motile parasites.10 Other options include visualization of parasites in a blood smear with Giemsa stain or hemoculture. Hemoculture is a sensitive test but takes several weeks to show growth of the parasites. Therefore, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay is the preferred diagnostic test due to its high sensitivity and quick turnaround time.5

Because no diagnostic gold standard exists for chronic disease, confidently diagnosing Chagas in the United States can be difficult.5 Past the acute phase (about three months after infection), microscopy and PCR cannot be used due to low parasitemia. If an infection with T cruzi is suspected but nine to 14 weeks have passed since exposure, serology is the method of choice for diagnosis. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunofluorescent-antibody assay (IFA) are most often used to identify immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies to the parasite.

The difficulty of diagnosing Chagas disease in the chronic phase lies in the fact that neither ELISA or IFA alone is sensitive or specific enough to confirm the diagnosis.5 In order to make a serologic diagnosis of infection, positive results are needed from two serologic tests based on two different antigens or by using two different techniques (eg, ELISA or IFA). If the two tests are discordant, a third test must be done to determine the patient’s infection status. The radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) and trypomastigote excreted-secreted antigen immunoblot (TESA-blot) have been traditionally used as confirmatory tests, but even they do not have high sensitivity and specificity. A case of indeterminate Chagas disease is confirmed with positive serologic testing in a patient without symptoms and with normal ECG, chest x-ray, and imaging of the colon and esophagus.15

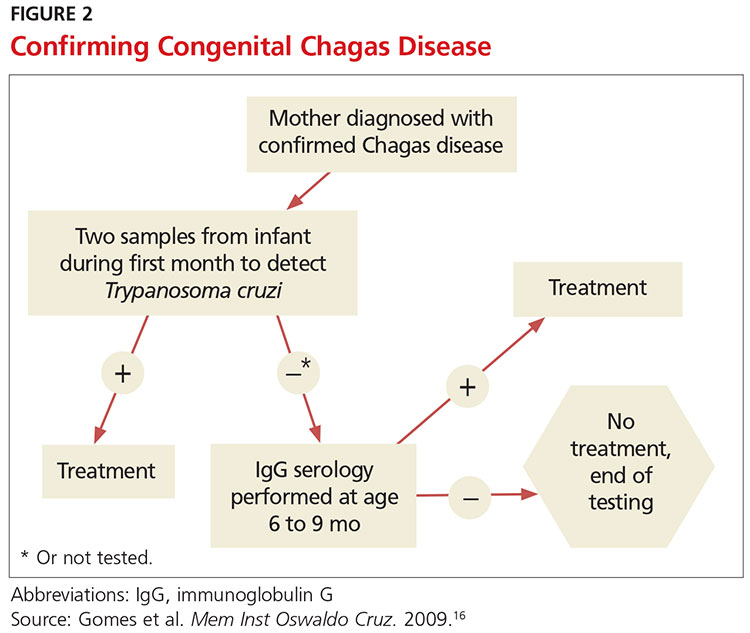

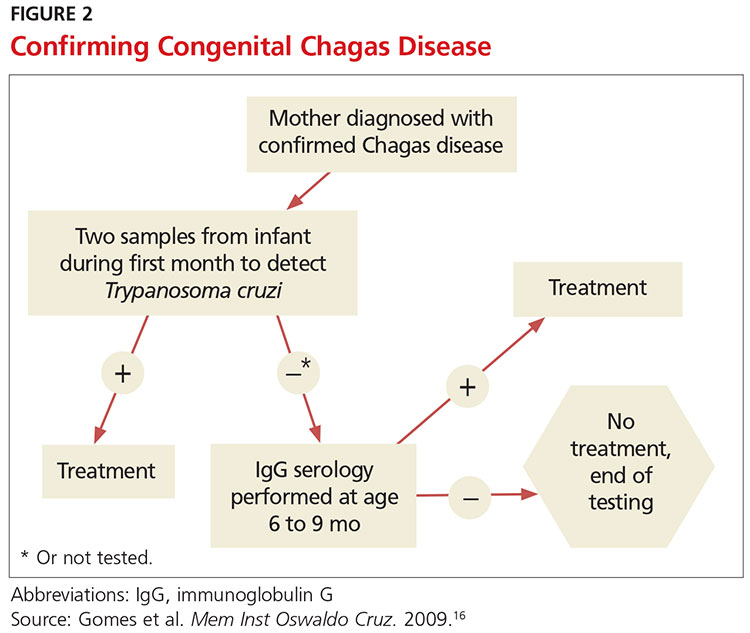

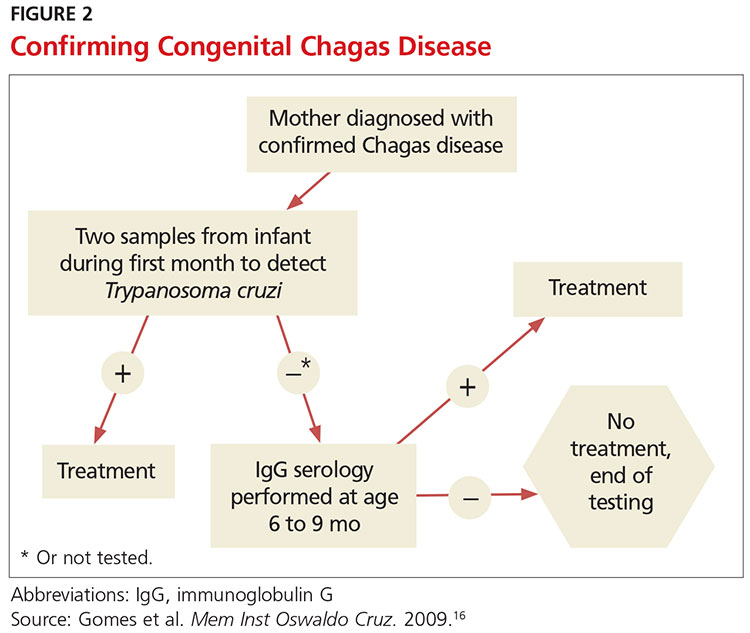

The preferred protocol for diagnosis of congenital Chagas disease first requires positive serologic testing confirming the infection in the mother (see Figure 2).16 Once that is determined, microscopic and PCR-based examinations of cord blood and peripheral blood specimens are carried out during the first one to two months of the infant’s life.10 PCR is the preferred test for early congenital Chagas disease, recipients of organ transplants, and after accidental exposure since results can determine if the patient is infected earlier than trypomastigotes (developmental stage of trypanosomes) can be seen on a peripheral blood smear.5

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

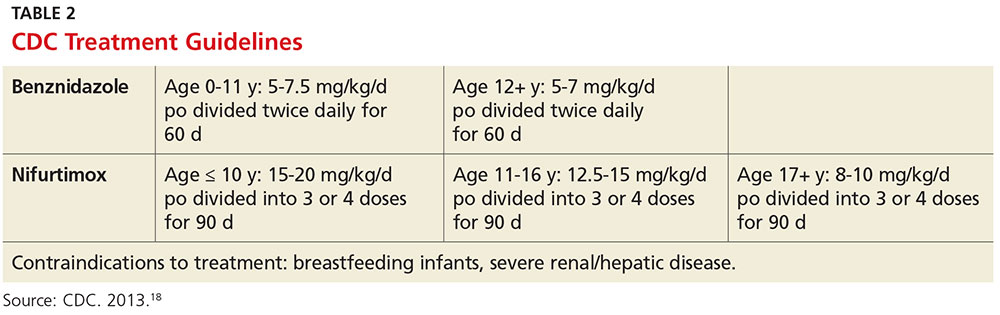

If there is a suspicion of Chagas disease, the patient should be referred to an infectious disease specialist for diagnosis and treatment. Nifurtimox and benznidazole are the only drugs that have been shown to improve the course of Chagas disease.5 However, neither drug is approved by the FDA, and both can only be obtained from the CDC, which makes treatment a challenge.9 In addition, up to 30% of patients terminate treatment due to the many adverse effects of these drugs.17

The dosage regimen for nifurtimox is 8-10 mg/kg/d divided into three doses for 90 days.10 Anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain occur in up to 70% of patients.5 Irritability, insomnia, disorientation, and tremors can also occur. Neurotoxicity leading to peripheral neuropathy is dose dependent and requires treatment termination.5

Benznidazole is better tolerated and is active against the trypomastigotes as well as the amastigotes or intracellular form of the parasite.10 The dosage regimen for benznidazole is 5-7 mg/kg/d divided into two doses for 60 days.10 Dermatologic reactions such as rash, photosensitivity, and exfoliative dermatitis are the most common adverse effects. Peripheral neuropathy and bone marrow suppression are dose dependent and require therapy cessation.5

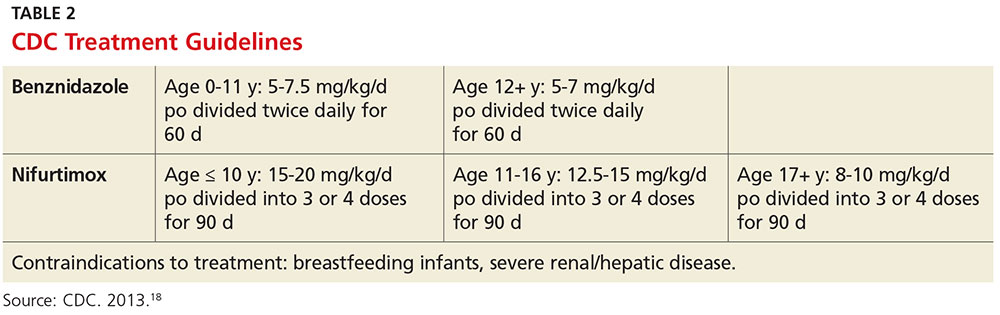

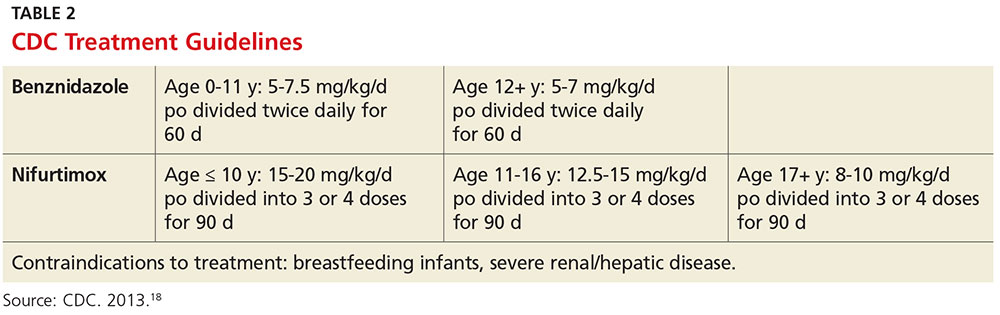

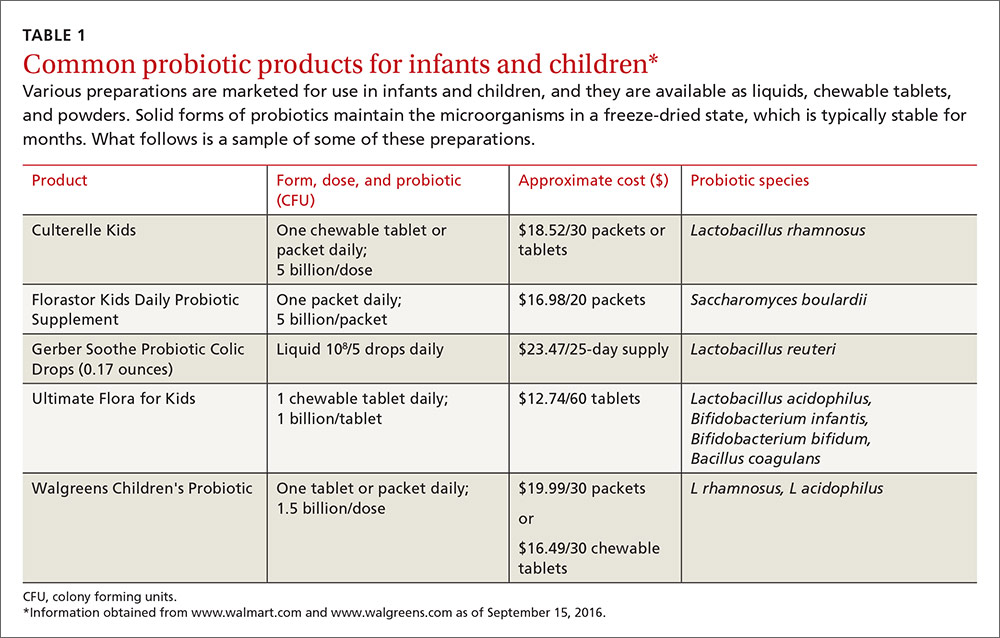

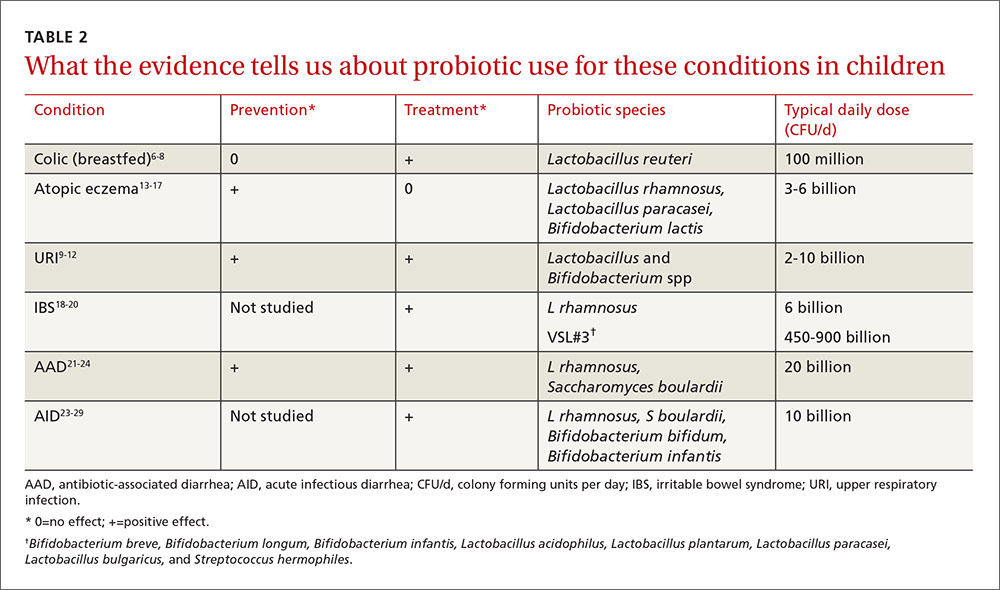

The CDC recommends treatment for all cases of acute disease (including congenital disease) regardless of age, and for chronic disease in patients up to age 50 who have not progressed to cardiomyopathy. In patients older than 50, treatment should be determined after weighing the potential risks and benefits (see Table 2).18

The success of treatment is determined in part by the phase of the disease. Cure rates in patients treated with either nifurtimox or benznidazole during the acute phase range from 65% to 80%.17 Chronic disease shows less of a response to traditional antiparasitic drug regimens, but higher rates of success are seen in younger patients.5 According to current estimates, successful treatment of chronic disease is limited to 15% to 30% patients.17 Treatment of congenital Chagas disease should begin as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed, and cure rates are greater than 90% if patients are treated within the first year of life.10 Treating congenital Chagas disease is important because the infection can be passed to future generations even if the disease never manifests with symptoms.19 However, if an expecting mother has known Chagas disease, antiparasitic medications are not recommended during the pregnancy because of a lack of fetal safety data for the two antiparasitic agents.20 Instead, it is recommended that women of childbearing age be treated before pregnancy, as rates of congenital infection are 25 times lower in women who are treated than in those who are not.21

PRE- AND POSTEXPOSURE PATIENT EDUCATION

Patient education mainly focuses on how to prevent Chagas disease and prognosis once diagnosed. During travel to endemic areas, the use of insecticides and residing in well-built households are the most important prevention measures. No vaccine is available, and primary chemoprophylaxis of persons visiting endemic areas is not recommended due to the low risk for infection and concerns about adverse effects.13

The survival rate of those who remain in the indeterminate phase is the same as that of the general population. However, findings that most strongly predict mortality include ventricular tachycardia, cardiomegaly, congestive heart failure (NYHA class III/IV), left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and male sex.10 Patients diagnosed with Chagas disease should be strongly encouraged not to donate blood or organs.10 Some organ and blood donation organizations selectively or universally screen donated specimens; however, this screening is not required by law.5 Family members of those diagnosed with the disease should also be tested, especially if the patient is a woman who has children or who plans to become pregnant.10

FOLLOW-UP

In patients confirmed to have Chagas disease but without symptoms and a normal ECG, further initial evaluation is not required.10 An annual history, physical exam, and ECG should be done. Those who have symptoms or ECG changes should have a complete cardiac work-up, including a 24-hour ambulatory ECG, exercise stress test, and echocardiogram to determine functional capacity. A barium swallow, barium enema, esophageal manometry, and endoscopy may be indicated in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms of Chagas disease but otherwise are not recommended. Patients taking antiparasitic drugs should have a CBC and CMP at the start of treatment and then bimonthly until the end of treatment to monitor for rare bone marrow suppression. Nifurtimox and benznidazole are also known to be mutagenic and increase the risk for lymphoma in animal studies, but this risk has not been documented in humans.10

CONCLUSION

Chagas disease is considered one of the neglected tropical diseases due to its high prevalence, chronic course, debilitating symptoms, and association with poverty.7 It is evident that incidence and prevalence of Chagas disease in the US are increasing due to recent immigration and mother-to-child transmission. Therefore, family practice clinicians must be able to recognize the red flags that suggest a T cruzi infection.5,9 Enhanced awareness of Chagas disease among health care providers will lead to better symptom control and cure rates for affected patients and may also prevent congenital infections. These efforts could serve to remove Chagas disease from the list of neglected tropical diseases.

1. Hotez PJ, Dumonteil E, Betancourt Cravioto M, et al. An unfolding tragedy of Chagas disease in North America. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013; 7(10):e2300.

2. Verani JR, Seitz A, Gilman RH, et al. Geographic variation in the sensitivity of recombinant antigen-based rapid tests for chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(3):410-415.

3. Malik LH, Singh GD, Amsterdam EA. The epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management of Chagas heart disease. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38(9):565-569.

4. World Health Organization. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). Fact sheet. Updated March 2016. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/. Accessed October 20, 2016.

5. Bern C, Kjos S, Yabsley MJ, Montgomery SP. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas’ disease in the United States. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011; 24(4):655-681.

6. Stimpert KK, Montgomery SP. Physician awareness of Chagas disease, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(5):871-872.

7. Hotez PJ. Neglected parasitic infections and poverty in the United States. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(9):e3012.

8. Goupil LS, McKerrow JH. Introduction: drug discovery and development for neglected diseases. Chem Rev. 2014;114(22):11131-11137.

9. Montgomery SP, Starr MC, Cantey P, et al. Neglected parasitic infections in the United States: Chagas disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014; 90(5):814-818.

10. Bern C, Montgomery SP, Herwaldt BL, et al. Evaluation and treatment of Chagas disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(18):2171-2181.

11. de Oliveira AP, Bernardo CR, Camargo AV, et al. Genetic susceptibility to cardiac and digestive clinical forms of chronic Chagas disease: involvement of the CCR5 59029 A/G polymorphism. PLoS One. 2015; 10(11):e0141847.

12. Apt W, Arribada A, Zulantay I, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi burden, genotypes, and clinical evaluation of Chilean patients with chronic Chagas cardiopathy. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(8):3007-3018.

13. Kirchhoff LV. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis): Background, pathophysiology, epidemiology. Emedicine.medscape.com. 2015. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/214581-overview. Accessed October 20, 2016.

14. Knipe H, St-Amant M. Chagas disease. Radiopaedia.org. 2015. http://radiopaedia.org/articles/chagas-disease. Accessed October 20, 2016.

15. Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Rassi SG. Predictors of mortality in chronic Chagas disease: a systematic review of observational studies. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1101-1108.

16. Gomes YM, Lorena VM, Luquetti AO. Diagnosis of Chagas disease: what has been achieved? What remains to be done with regard to diagnosis and follow up studies? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009; 104(suppl 1):115-121.

17. Molina I, Gómez i Prat J, Salvador F, et al. Randomized trial of posaconazole and benznidazole for chronic Chagas’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1899-1908.

18. CDC. Parasites – American trypanosomiasis (also known as Chagas Disease). Antiparasitic Treatment. Resources For Health Professionals. www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/health_professionals/tx.html. Accessed October 20, 2016.

19. Carlier Y, Truyens C. Congenital Chagas disease as an ecological model of interactions between Trypanosoma cruzi parasites, pregnant women, placenta and fetuses. Acta Trop. 2015;151:103-115.

20. Moscatelli G, Moroni S, García-Bournissen F, et al. Prevention of congenital Chagas through treatment of girls and women of childbearing age. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110(4):507-509.

21. Fabbro D, Danesi E, Olivera V, et al. Trypanocide treatment of women infected with Trypanosoma cruzi and its effect on preventing congenital Chagas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(11):e3312.

CE/CME No: CR-1611

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand the prevalence and risks of Chagas disease in the United States.

• Explain the pathophysiology of Chagas disease, including the vector and transmission routes of the disease.

• Describe the clinical presentation of both the acute and chronic forms of the disease and learn when to suspect an infection.

• Outline a plan for diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease.

• Educate women with Chagas disease about the risk of transmission for future offspring.

FACULTY

Jessica McDonald works in the Emergency Medicine Department at Dekalb Medical Center, Atlanta. Jill Mattingly is Academic Coordinator and Clinical Assistant Professor in the Physician Assistant Program at Mercer University, Atlanta.

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of November 2016.

Article begins on next page >>

Chagas disease, a parasitic infection, is increasingly being detected in the United States, most likely due to immigration from endemic countries in South and Central America. Approximately 300,000 persons in the US have chronic Chagas disease, and up to 30% of them will develop clinically evident cardiovascular and/or gastrointestinal disease. Here’s practical guidance to help you recognize the features of symptomatic Chagas disease and follow up with appropriate evaluation and management.

Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi.1 It is most commonly spread by triatomine bugs infected with T cruzi and is endemic in many parts of Mexico and Central and South America.2 Chagas disease was first described in 1909 by Brazilian physician Carlos Chagas.3 Since its discovery, it has often been considered a disease affecting only the poor living in endemic areas of Latin America. However, 6 million to 7 million people are infected with T cruzi worldwide, and estimates suggest that Mexico and the US rank third and seventh, respectively, in the number of persons with T cruzi infection in the Western Hemisphere.1,4

An estimated 300,000 persons in the US have Chagas disease; most of them are not aware that they are infected.5,6 The increasing presence of the disease in the US, which traditionally has been considered a nonendemic area, is due to immigration from endemic areas, with subsequent infections occurring through mechanisms that do not require contact with the triatomine vector (eg, congenital transmission).1 Between 1981 and 2005, more than 7 million people from T cruzi-endemic countries in Latin America moved to the US and became legal residents.3

Early detection and treatment of Chagas disease is important because up to 30% of patients with chronic infection will develop a heart disorder, which can range in severity from conduction system abnormalities to dilated cardiomyopathy.4 In some areas of southern Mexico, Chagas disease is the most common cause of dilated cardiomyopathy.1 Equally concerning is the fact that untreated mothers with Chagas disease can transmit T cruzi to their infants.1,3 An estimated 315 babies are born with congenital Chagas disease each year in the US, an incidence equivalent to that of phenylketonuria.7 It is estimated that congenital transmission is responsible for up to one-quarter of new infections worldwide.1 Unfortunately, obstetricians are not well informed about the risk factors for congenital Chagas disease, and very limited screening of at-risk women is performed. In a 2008 survey exploring health care providers’ knowledge of and understanding about Chagas disease, obstetricians and gynecologists had the greatest knowledge deficits about the disease, although considerable deficits were also seen among other specialties.1

KISSING BUG DISEASE: ETIOLOGY/PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Exposure to the protozoan parasite T cruzi, the cause of Chagas disease, typically occurs following the bite of a triatomine bug. Also known as “kissing bugs” because they usually bite exposed areas of the skin such as the face, triatomine bugs feed on human blood, typically at night, and act as a vector for the parasite.8 The parasite lives in the feces and urine of the triatomine bugs and is excreted near the bite during or shortly after a blood meal. The bitten person will then unknowingly smear the infected feces into the bite wound, eyes, mouth, or any opening in the skin, which gives the parasites systemic access.4 Once in the host’s bloodstream, the parasite replicates in host cells, a process that ends in cell lysis and hematogenous spread. At this point, the parasites can be seen on peripheral blood smear. Noninfected triatomine insects become infected and continue the cycle when they feed on an infected human host (see Figure 1).3 Persons of lower socioeconomic status living in endemic areas in Latin America are at a higher risk for contracting Chagas disease because “kissing bugs” commonly live in wall or roof cracks of poorly built homes. Populations living in poverty are also at risk due to minimal access to health care and prenatal care.4 Transmission of T cruzi not involving triatomine vectors occurs congenitally or through blood transfusions, consumption of contaminated food, and organ donations.4

NATURAL HISTORY OF INFECTION AND PATIENT PRESENTATION

Acute phase

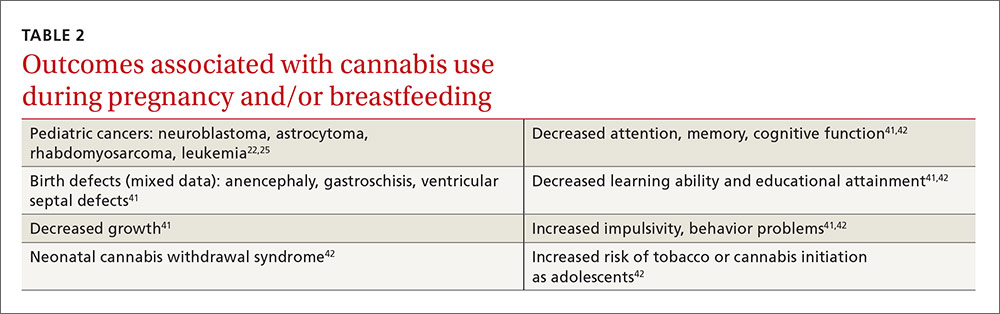

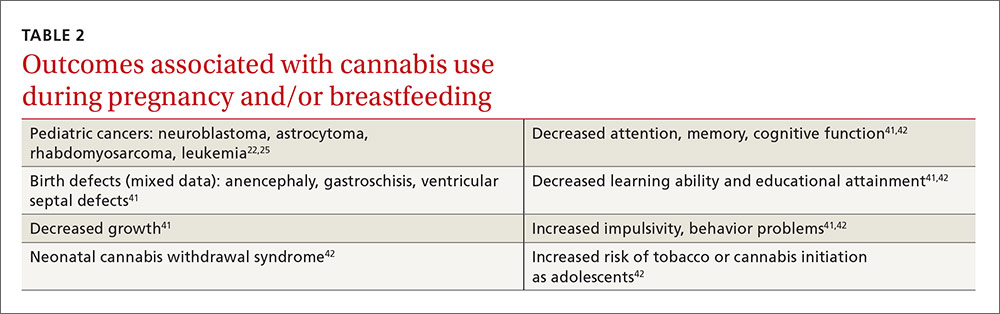

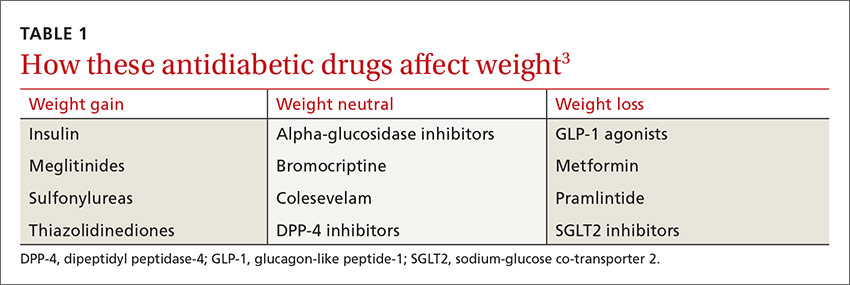

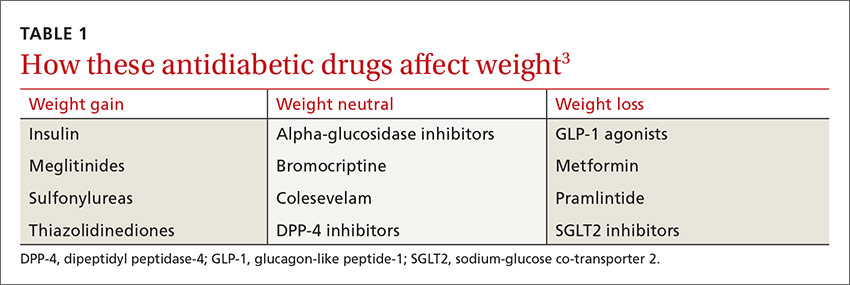

Infection with the T cruzi parasite is followed by an asymptomatic incubation period of one to two weeks, which is then followed by an acute phase that can last eight to 12 weeks.5 The acute phase is characterized by a large amount of parasites in the bloodstream (see Table 1). The patient is often asymptomatic but can have nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, lymphadenopathy, shortness of breath, myalgia, swelling, and abdominal or chest pain.4 Because symptoms during the acute phase are typically mild, many patients do not seek medical attention until they transition into the chronic phase.4 Infants are more likely to experience severe symptoms, including myocarditis or meningoencephalitis, and thus are more likely to present during the acute phase.9

If the patient acquired the infection through an organ transplant, the acute phase symptoms can be delayed, on average, up to 112 days.5 These patients will have more noticeable symptoms, including hepatosplenomegaly, myocarditis, and congestive heart failure. Due to the known risk for transmission through organ transplants, donors are often screened for Chagas disease. Unfortunately, this screening is selective and often inconsistent.5 Therefore, the presence of the previously mentioned symptoms in a person who recently received an organ transplant should raise suspicion of Chagas disease.5

Chronic phase

Patients not treated during the acute phase will pass into the chronic phase of Chagas disease.5 This may occur due to reactivation of T cruzi infection via immunosuppression.9 At this time, the previously asymptomatic patient will have typical signs and symptoms of chronic disease, along with nodules, panniculitis, and myocarditis.4,9,10 During the chronic phase, parasites are undetectable by microscopy, but the patient can still spread the disease to the vector as well as to others congenitally and through organ donation and blood transfusions.5,9

Patients with chronic T cruzi infection who remain without signs or symptoms of infection are considered to have the indeterminate form of chronic disease. Many patients will remain in the indeterminate form throughout their lives, but between 20% and 30% will progress to the determinate form of chronic disease over years to decades.3 The determinate form is characterized by clinically evident disease and is classically divided into cardiac Chagas disease and digestive Chagas disease.5 Symptoms of the chronic phase depend on the genotype of T cruzi that caused the infection. The AG genotype has a higher incidence of digestive disease.11

Cardiac Chagas disease is believed to occur due to parasite invasion and persistence in cardiac tissue, leading to immune-mediated myocardial injury.5 Chagas cardiomyopathy is characterized by chronic myocarditis affecting all cardiac chambers and disturbances in the electrical conduction system; patients also often develop apical aneurysms. Longstanding cardiac Chagas disease can lead to more serious complications, such as episodes of ventricular tachycardia, heart block, thromboembolic phenomena, severe bradycardia, dilated cardiomyopathy, and congestive heart failure. Patients may complain of presyncope, syncope, and episodes of palpitations. They are also at high risk for sudden cardiac death.5 Patients with cardiomyopathy or cardiac insufficiency secondary to Chagas disease have a worse prognosis than those with idiopathic cardiomyopathy or decompensated heart failure due to other etiologies.12

Less common than cardiac Chagas disease, digestive Chagas disease occurs mostly in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and parts of Peru and Brazil; it is rarely seen in northern South America, Central America, or Mexico.5 The parasite causes gastrointestinal symptoms by damaging intramural neurons, resulting in denervation of hollow viscera. Since it affects the esophagus and colon, patients may present with dysphagia, odynophagia, cough, reflux, weight loss, constipation, and abdominal pain.5

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION: A CRUCIAL STEP

The physical examination of a patient with suspected Chagas disease can be crucial to the diagnosis. As noted, there are often few specific symptoms or physical exam findings during the acute phase. However, in some patients, swelling and inflammation may be evident at the site of inoculation, often on the face or extremities. This finding is called a chagoma. The Romaña sign, characterized by painless unilateral swelling of the upper and lower eyelid, can also be seen if the infection occurred through the conjunctiva.5 A nonpruritic morbilliform rash, called schizotrypanides, may be a presenting symptom in patients with acute disease.13 Children younger than 2 years of age are at increased risk for a severe acute infection, with signs and symptoms of pericardial effusion, myocarditis, and meningoencephalitis. Children can also develop generalized edema and lymphadenopathy. Those children who develop severe manifestations during acute infection have an increased risk for mortality.5

Chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy may present with signs of left-sided heart failure (pulmonary edema, dyspnea at rest or exertion), biventricular heart failure (hepatomegaly, peripheral edema, jugular venous distention), or thromboembolic events to the brain, lower extremities, and lungs.13 Chronic chagasic megaesophagus may lead to weight loss, esophageal dysmotility, pneumonitis due to aspiration of food trapped in the esophagus and stomach, salivary gland enlargement, and erosive esophagitis, which increases the risk for esophageal cancer. Chronic chagasic megacolon can present as an intestinal obstruction, volvulus, abdominal distention, or fecaloma.13

Clinicians should be alert to the possibility of congenital T cruzi infection in children born to women who emigrated from an endemic area or who visited an area with a high prevalence of Chagas disease. Most newborns with T cruzi infection are asymptomatic, but in some cases a thorough neonatal exam can lead to the diagnosis. Manifestations of symptomatic congenital infection include hepatosplenomegaly, low birth weight, premature birth, and low Apgar scores.5 Lab tests may reveal thrombocytopenia and anemia. Neonates with severe disease may also have respiratory distress, meningoencephalitis, and gastrointestinal problems.5

LABORATORY WORK-UP

Laboratory work-up for Chagas disease depends on the provider’s awareness of the disease and its symptoms. All patients should undergo routine blood work, including complete blood count (CBC) with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and liver function tests to rule out other etiologies that manifest with similar symptoms. If the patient presents during the acute phase, microscopy of blood smears with Giemsa stain should be done to visualize the parasites. In the patient who presents during the chronic phase with cardiac symptoms, measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide, troponin, C-reactive protein, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate can be used to rule out other differential diagnoses. Electrocardiogram (ECG) may show a right bundle-branch block or left anterior fascicular block.5 Echocardiogram may show left ventricular wall motion abnormalities and/or cardiomyopathy with congestive heart failure.5,10 A work-up for digestive Chagas disease may include a barium swallow, kidney-ureter-bladder x-ray, or MRI/CT of the abdomen.14

DIAGNOSING ACUTE, CHRONIC, AND CONGENITAL CHAGAS

Accurate diagnosis of Chagas disease requires a thorough history and physical exam, as well as a high index of suspicion. Recent travel to an endemic area of Chagas disease in combination with the typical signs and symptoms—such as fever, headache, lymphadenopathy, shortness of breath, myalgia, swelling, and abdominal or chest pain—should prompt the provider to perform more specific tests.4 Inquiry about past medical history, blood transfusions, and surgeries is also imperative to make the correct diagnosis.5

The approach to diagnosis of Chagas disease depends on whether the patient presents during the acute or chronic phase. During the acute phase, the count of the trypomastigote, the mature extracellular form of the parasite T cruzi, is at its highest, making this the best time to obtain an accurate diagnosis if an infection is suspected.3 Microscopy of fresh preparations of anticoagulated blood or buffy coat may show motile parasites.10 Other options include visualization of parasites in a blood smear with Giemsa stain or hemoculture. Hemoculture is a sensitive test but takes several weeks to show growth of the parasites. Therefore, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay is the preferred diagnostic test due to its high sensitivity and quick turnaround time.5

Because no diagnostic gold standard exists for chronic disease, confidently diagnosing Chagas in the United States can be difficult.5 Past the acute phase (about three months after infection), microscopy and PCR cannot be used due to low parasitemia. If an infection with T cruzi is suspected but nine to 14 weeks have passed since exposure, serology is the method of choice for diagnosis. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunofluorescent-antibody assay (IFA) are most often used to identify immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies to the parasite.

The difficulty of diagnosing Chagas disease in the chronic phase lies in the fact that neither ELISA or IFA alone is sensitive or specific enough to confirm the diagnosis.5 In order to make a serologic diagnosis of infection, positive results are needed from two serologic tests based on two different antigens or by using two different techniques (eg, ELISA or IFA). If the two tests are discordant, a third test must be done to determine the patient’s infection status. The radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) and trypomastigote excreted-secreted antigen immunoblot (TESA-blot) have been traditionally used as confirmatory tests, but even they do not have high sensitivity and specificity. A case of indeterminate Chagas disease is confirmed with positive serologic testing in a patient without symptoms and with normal ECG, chest x-ray, and imaging of the colon and esophagus.15

The preferred protocol for diagnosis of congenital Chagas disease first requires positive serologic testing confirming the infection in the mother (see Figure 2).16 Once that is determined, microscopic and PCR-based examinations of cord blood and peripheral blood specimens are carried out during the first one to two months of the infant’s life.10 PCR is the preferred test for early congenital Chagas disease, recipients of organ transplants, and after accidental exposure since results can determine if the patient is infected earlier than trypomastigotes (developmental stage of trypanosomes) can be seen on a peripheral blood smear.5

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

If there is a suspicion of Chagas disease, the patient should be referred to an infectious disease specialist for diagnosis and treatment. Nifurtimox and benznidazole are the only drugs that have been shown to improve the course of Chagas disease.5 However, neither drug is approved by the FDA, and both can only be obtained from the CDC, which makes treatment a challenge.9 In addition, up to 30% of patients terminate treatment due to the many adverse effects of these drugs.17

The dosage regimen for nifurtimox is 8-10 mg/kg/d divided into three doses for 90 days.10 Anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain occur in up to 70% of patients.5 Irritability, insomnia, disorientation, and tremors can also occur. Neurotoxicity leading to peripheral neuropathy is dose dependent and requires treatment termination.5

Benznidazole is better tolerated and is active against the trypomastigotes as well as the amastigotes or intracellular form of the parasite.10 The dosage regimen for benznidazole is 5-7 mg/kg/d divided into two doses for 60 days.10 Dermatologic reactions such as rash, photosensitivity, and exfoliative dermatitis are the most common adverse effects. Peripheral neuropathy and bone marrow suppression are dose dependent and require therapy cessation.5

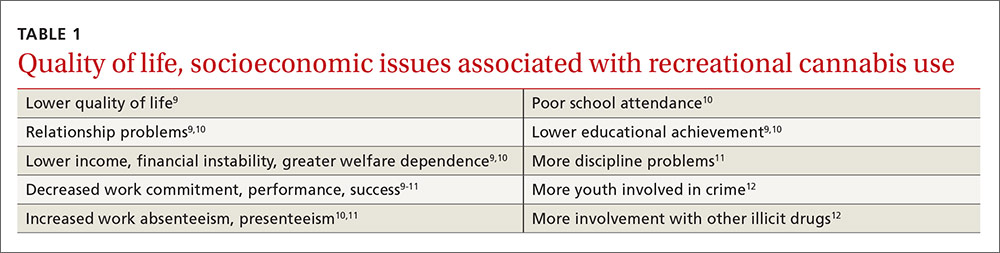

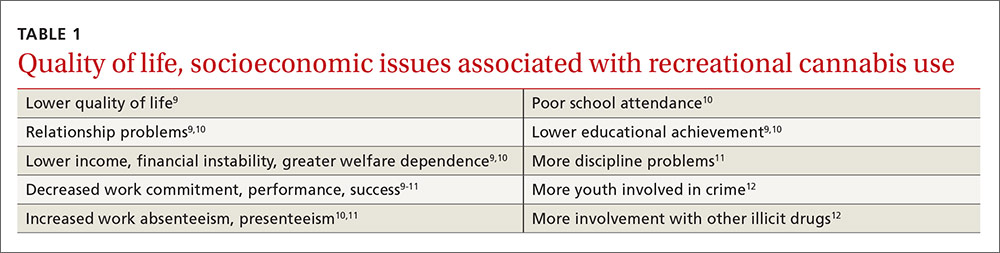

The CDC recommends treatment for all cases of acute disease (including congenital disease) regardless of age, and for chronic disease in patients up to age 50 who have not progressed to cardiomyopathy. In patients older than 50, treatment should be determined after weighing the potential risks and benefits (see Table 2).18

The success of treatment is determined in part by the phase of the disease. Cure rates in patients treated with either nifurtimox or benznidazole during the acute phase range from 65% to 80%.17 Chronic disease shows less of a response to traditional antiparasitic drug regimens, but higher rates of success are seen in younger patients.5 According to current estimates, successful treatment of chronic disease is limited to 15% to 30% patients.17 Treatment of congenital Chagas disease should begin as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed, and cure rates are greater than 90% if patients are treated within the first year of life.10 Treating congenital Chagas disease is important because the infection can be passed to future generations even if the disease never manifests with symptoms.19 However, if an expecting mother has known Chagas disease, antiparasitic medications are not recommended during the pregnancy because of a lack of fetal safety data for the two antiparasitic agents.20 Instead, it is recommended that women of childbearing age be treated before pregnancy, as rates of congenital infection are 25 times lower in women who are treated than in those who are not.21

PRE- AND POSTEXPOSURE PATIENT EDUCATION

Patient education mainly focuses on how to prevent Chagas disease and prognosis once diagnosed. During travel to endemic areas, the use of insecticides and residing in well-built households are the most important prevention measures. No vaccine is available, and primary chemoprophylaxis of persons visiting endemic areas is not recommended due to the low risk for infection and concerns about adverse effects.13

The survival rate of those who remain in the indeterminate phase is the same as that of the general population. However, findings that most strongly predict mortality include ventricular tachycardia, cardiomegaly, congestive heart failure (NYHA class III/IV), left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and male sex.10 Patients diagnosed with Chagas disease should be strongly encouraged not to donate blood or organs.10 Some organ and blood donation organizations selectively or universally screen donated specimens; however, this screening is not required by law.5 Family members of those diagnosed with the disease should also be tested, especially if the patient is a woman who has children or who plans to become pregnant.10

FOLLOW-UP

In patients confirmed to have Chagas disease but without symptoms and a normal ECG, further initial evaluation is not required.10 An annual history, physical exam, and ECG should be done. Those who have symptoms or ECG changes should have a complete cardiac work-up, including a 24-hour ambulatory ECG, exercise stress test, and echocardiogram to determine functional capacity. A barium swallow, barium enema, esophageal manometry, and endoscopy may be indicated in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms of Chagas disease but otherwise are not recommended. Patients taking antiparasitic drugs should have a CBC and CMP at the start of treatment and then bimonthly until the end of treatment to monitor for rare bone marrow suppression. Nifurtimox and benznidazole are also known to be mutagenic and increase the risk for lymphoma in animal studies, but this risk has not been documented in humans.10

CONCLUSION

Chagas disease is considered one of the neglected tropical diseases due to its high prevalence, chronic course, debilitating symptoms, and association with poverty.7 It is evident that incidence and prevalence of Chagas disease in the US are increasing due to recent immigration and mother-to-child transmission. Therefore, family practice clinicians must be able to recognize the red flags that suggest a T cruzi infection.5,9 Enhanced awareness of Chagas disease among health care providers will lead to better symptom control and cure rates for affected patients and may also prevent congenital infections. These efforts could serve to remove Chagas disease from the list of neglected tropical diseases.

CE/CME No: CR-1611

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand the prevalence and risks of Chagas disease in the United States.

• Explain the pathophysiology of Chagas disease, including the vector and transmission routes of the disease.

• Describe the clinical presentation of both the acute and chronic forms of the disease and learn when to suspect an infection.

• Outline a plan for diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease.

• Educate women with Chagas disease about the risk of transmission for future offspring.

FACULTY

Jessica McDonald works in the Emergency Medicine Department at Dekalb Medical Center, Atlanta. Jill Mattingly is Academic Coordinator and Clinical Assistant Professor in the Physician Assistant Program at Mercer University, Atlanta.

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of November 2016.

Article begins on next page >>

Chagas disease, a parasitic infection, is increasingly being detected in the United States, most likely due to immigration from endemic countries in South and Central America. Approximately 300,000 persons in the US have chronic Chagas disease, and up to 30% of them will develop clinically evident cardiovascular and/or gastrointestinal disease. Here’s practical guidance to help you recognize the features of symptomatic Chagas disease and follow up with appropriate evaluation and management.

Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi.1 It is most commonly spread by triatomine bugs infected with T cruzi and is endemic in many parts of Mexico and Central and South America.2 Chagas disease was first described in 1909 by Brazilian physician Carlos Chagas.3 Since its discovery, it has often been considered a disease affecting only the poor living in endemic areas of Latin America. However, 6 million to 7 million people are infected with T cruzi worldwide, and estimates suggest that Mexico and the US rank third and seventh, respectively, in the number of persons with T cruzi infection in the Western Hemisphere.1,4

An estimated 300,000 persons in the US have Chagas disease; most of them are not aware that they are infected.5,6 The increasing presence of the disease in the US, which traditionally has been considered a nonendemic area, is due to immigration from endemic areas, with subsequent infections occurring through mechanisms that do not require contact with the triatomine vector (eg, congenital transmission).1 Between 1981 and 2005, more than 7 million people from T cruzi-endemic countries in Latin America moved to the US and became legal residents.3

Early detection and treatment of Chagas disease is important because up to 30% of patients with chronic infection will develop a heart disorder, which can range in severity from conduction system abnormalities to dilated cardiomyopathy.4 In some areas of southern Mexico, Chagas disease is the most common cause of dilated cardiomyopathy.1 Equally concerning is the fact that untreated mothers with Chagas disease can transmit T cruzi to their infants.1,3 An estimated 315 babies are born with congenital Chagas disease each year in the US, an incidence equivalent to that of phenylketonuria.7 It is estimated that congenital transmission is responsible for up to one-quarter of new infections worldwide.1 Unfortunately, obstetricians are not well informed about the risk factors for congenital Chagas disease, and very limited screening of at-risk women is performed. In a 2008 survey exploring health care providers’ knowledge of and understanding about Chagas disease, obstetricians and gynecologists had the greatest knowledge deficits about the disease, although considerable deficits were also seen among other specialties.1

KISSING BUG DISEASE: ETIOLOGY/PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Exposure to the protozoan parasite T cruzi, the cause of Chagas disease, typically occurs following the bite of a triatomine bug. Also known as “kissing bugs” because they usually bite exposed areas of the skin such as the face, triatomine bugs feed on human blood, typically at night, and act as a vector for the parasite.8 The parasite lives in the feces and urine of the triatomine bugs and is excreted near the bite during or shortly after a blood meal. The bitten person will then unknowingly smear the infected feces into the bite wound, eyes, mouth, or any opening in the skin, which gives the parasites systemic access.4 Once in the host’s bloodstream, the parasite replicates in host cells, a process that ends in cell lysis and hematogenous spread. At this point, the parasites can be seen on peripheral blood smear. Noninfected triatomine insects become infected and continue the cycle when they feed on an infected human host (see Figure 1).3 Persons of lower socioeconomic status living in endemic areas in Latin America are at a higher risk for contracting Chagas disease because “kissing bugs” commonly live in wall or roof cracks of poorly built homes. Populations living in poverty are also at risk due to minimal access to health care and prenatal care.4 Transmission of T cruzi not involving triatomine vectors occurs congenitally or through blood transfusions, consumption of contaminated food, and organ donations.4

NATURAL HISTORY OF INFECTION AND PATIENT PRESENTATION

Acute phase

Infection with the T cruzi parasite is followed by an asymptomatic incubation period of one to two weeks, which is then followed by an acute phase that can last eight to 12 weeks.5 The acute phase is characterized by a large amount of parasites in the bloodstream (see Table 1). The patient is often asymptomatic but can have nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, lymphadenopathy, shortness of breath, myalgia, swelling, and abdominal or chest pain.4 Because symptoms during the acute phase are typically mild, many patients do not seek medical attention until they transition into the chronic phase.4 Infants are more likely to experience severe symptoms, including myocarditis or meningoencephalitis, and thus are more likely to present during the acute phase.9

If the patient acquired the infection through an organ transplant, the acute phase symptoms can be delayed, on average, up to 112 days.5 These patients will have more noticeable symptoms, including hepatosplenomegaly, myocarditis, and congestive heart failure. Due to the known risk for transmission through organ transplants, donors are often screened for Chagas disease. Unfortunately, this screening is selective and often inconsistent.5 Therefore, the presence of the previously mentioned symptoms in a person who recently received an organ transplant should raise suspicion of Chagas disease.5

Chronic phase

Patients not treated during the acute phase will pass into the chronic phase of Chagas disease.5 This may occur due to reactivation of T cruzi infection via immunosuppression.9 At this time, the previously asymptomatic patient will have typical signs and symptoms of chronic disease, along with nodules, panniculitis, and myocarditis.4,9,10 During the chronic phase, parasites are undetectable by microscopy, but the patient can still spread the disease to the vector as well as to others congenitally and through organ donation and blood transfusions.5,9

Patients with chronic T cruzi infection who remain without signs or symptoms of infection are considered to have the indeterminate form of chronic disease. Many patients will remain in the indeterminate form throughout their lives, but between 20% and 30% will progress to the determinate form of chronic disease over years to decades.3 The determinate form is characterized by clinically evident disease and is classically divided into cardiac Chagas disease and digestive Chagas disease.5 Symptoms of the chronic phase depend on the genotype of T cruzi that caused the infection. The AG genotype has a higher incidence of digestive disease.11

Cardiac Chagas disease is believed to occur due to parasite invasion and persistence in cardiac tissue, leading to immune-mediated myocardial injury.5 Chagas cardiomyopathy is characterized by chronic myocarditis affecting all cardiac chambers and disturbances in the electrical conduction system; patients also often develop apical aneurysms. Longstanding cardiac Chagas disease can lead to more serious complications, such as episodes of ventricular tachycardia, heart block, thromboembolic phenomena, severe bradycardia, dilated cardiomyopathy, and congestive heart failure. Patients may complain of presyncope, syncope, and episodes of palpitations. They are also at high risk for sudden cardiac death.5 Patients with cardiomyopathy or cardiac insufficiency secondary to Chagas disease have a worse prognosis than those with idiopathic cardiomyopathy or decompensated heart failure due to other etiologies.12

Less common than cardiac Chagas disease, digestive Chagas disease occurs mostly in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and parts of Peru and Brazil; it is rarely seen in northern South America, Central America, or Mexico.5 The parasite causes gastrointestinal symptoms by damaging intramural neurons, resulting in denervation of hollow viscera. Since it affects the esophagus and colon, patients may present with dysphagia, odynophagia, cough, reflux, weight loss, constipation, and abdominal pain.5

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION: A CRUCIAL STEP

The physical examination of a patient with suspected Chagas disease can be crucial to the diagnosis. As noted, there are often few specific symptoms or physical exam findings during the acute phase. However, in some patients, swelling and inflammation may be evident at the site of inoculation, often on the face or extremities. This finding is called a chagoma. The Romaña sign, characterized by painless unilateral swelling of the upper and lower eyelid, can also be seen if the infection occurred through the conjunctiva.5 A nonpruritic morbilliform rash, called schizotrypanides, may be a presenting symptom in patients with acute disease.13 Children younger than 2 years of age are at increased risk for a severe acute infection, with signs and symptoms of pericardial effusion, myocarditis, and meningoencephalitis. Children can also develop generalized edema and lymphadenopathy. Those children who develop severe manifestations during acute infection have an increased risk for mortality.5

Chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy may present with signs of left-sided heart failure (pulmonary edema, dyspnea at rest or exertion), biventricular heart failure (hepatomegaly, peripheral edema, jugular venous distention), or thromboembolic events to the brain, lower extremities, and lungs.13 Chronic chagasic megaesophagus may lead to weight loss, esophageal dysmotility, pneumonitis due to aspiration of food trapped in the esophagus and stomach, salivary gland enlargement, and erosive esophagitis, which increases the risk for esophageal cancer. Chronic chagasic megacolon can present as an intestinal obstruction, volvulus, abdominal distention, or fecaloma.13

Clinicians should be alert to the possibility of congenital T cruzi infection in children born to women who emigrated from an endemic area or who visited an area with a high prevalence of Chagas disease. Most newborns with T cruzi infection are asymptomatic, but in some cases a thorough neonatal exam can lead to the diagnosis. Manifestations of symptomatic congenital infection include hepatosplenomegaly, low birth weight, premature birth, and low Apgar scores.5 Lab tests may reveal thrombocytopenia and anemia. Neonates with severe disease may also have respiratory distress, meningoencephalitis, and gastrointestinal problems.5

LABORATORY WORK-UP

Laboratory work-up for Chagas disease depends on the provider’s awareness of the disease and its symptoms. All patients should undergo routine blood work, including complete blood count (CBC) with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and liver function tests to rule out other etiologies that manifest with similar symptoms. If the patient presents during the acute phase, microscopy of blood smears with Giemsa stain should be done to visualize the parasites. In the patient who presents during the chronic phase with cardiac symptoms, measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide, troponin, C-reactive protein, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate can be used to rule out other differential diagnoses. Electrocardiogram (ECG) may show a right bundle-branch block or left anterior fascicular block.5 Echocardiogram may show left ventricular wall motion abnormalities and/or cardiomyopathy with congestive heart failure.5,10 A work-up for digestive Chagas disease may include a barium swallow, kidney-ureter-bladder x-ray, or MRI/CT of the abdomen.14

DIAGNOSING ACUTE, CHRONIC, AND CONGENITAL CHAGAS

Accurate diagnosis of Chagas disease requires a thorough history and physical exam, as well as a high index of suspicion. Recent travel to an endemic area of Chagas disease in combination with the typical signs and symptoms—such as fever, headache, lymphadenopathy, shortness of breath, myalgia, swelling, and abdominal or chest pain—should prompt the provider to perform more specific tests.4 Inquiry about past medical history, blood transfusions, and surgeries is also imperative to make the correct diagnosis.5

The approach to diagnosis of Chagas disease depends on whether the patient presents during the acute or chronic phase. During the acute phase, the count of the trypomastigote, the mature extracellular form of the parasite T cruzi, is at its highest, making this the best time to obtain an accurate diagnosis if an infection is suspected.3 Microscopy of fresh preparations of anticoagulated blood or buffy coat may show motile parasites.10 Other options include visualization of parasites in a blood smear with Giemsa stain or hemoculture. Hemoculture is a sensitive test but takes several weeks to show growth of the parasites. Therefore, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay is the preferred diagnostic test due to its high sensitivity and quick turnaround time.5

Because no diagnostic gold standard exists for chronic disease, confidently diagnosing Chagas in the United States can be difficult.5 Past the acute phase (about three months after infection), microscopy and PCR cannot be used due to low parasitemia. If an infection with T cruzi is suspected but nine to 14 weeks have passed since exposure, serology is the method of choice for diagnosis. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunofluorescent-antibody assay (IFA) are most often used to identify immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies to the parasite.

The difficulty of diagnosing Chagas disease in the chronic phase lies in the fact that neither ELISA or IFA alone is sensitive or specific enough to confirm the diagnosis.5 In order to make a serologic diagnosis of infection, positive results are needed from two serologic tests based on two different antigens or by using two different techniques (eg, ELISA or IFA). If the two tests are discordant, a third test must be done to determine the patient’s infection status. The radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) and trypomastigote excreted-secreted antigen immunoblot (TESA-blot) have been traditionally used as confirmatory tests, but even they do not have high sensitivity and specificity. A case of indeterminate Chagas disease is confirmed with positive serologic testing in a patient without symptoms and with normal ECG, chest x-ray, and imaging of the colon and esophagus.15

The preferred protocol for diagnosis of congenital Chagas disease first requires positive serologic testing confirming the infection in the mother (see Figure 2).16 Once that is determined, microscopic and PCR-based examinations of cord blood and peripheral blood specimens are carried out during the first one to two months of the infant’s life.10 PCR is the preferred test for early congenital Chagas disease, recipients of organ transplants, and after accidental exposure since results can determine if the patient is infected earlier than trypomastigotes (developmental stage of trypanosomes) can be seen on a peripheral blood smear.5

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

If there is a suspicion of Chagas disease, the patient should be referred to an infectious disease specialist for diagnosis and treatment. Nifurtimox and benznidazole are the only drugs that have been shown to improve the course of Chagas disease.5 However, neither drug is approved by the FDA, and both can only be obtained from the CDC, which makes treatment a challenge.9 In addition, up to 30% of patients terminate treatment due to the many adverse effects of these drugs.17

The dosage regimen for nifurtimox is 8-10 mg/kg/d divided into three doses for 90 days.10 Anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain occur in up to 70% of patients.5 Irritability, insomnia, disorientation, and tremors can also occur. Neurotoxicity leading to peripheral neuropathy is dose dependent and requires treatment termination.5

Benznidazole is better tolerated and is active against the trypomastigotes as well as the amastigotes or intracellular form of the parasite.10 The dosage regimen for benznidazole is 5-7 mg/kg/d divided into two doses for 60 days.10 Dermatologic reactions such as rash, photosensitivity, and exfoliative dermatitis are the most common adverse effects. Peripheral neuropathy and bone marrow suppression are dose dependent and require therapy cessation.5

The CDC recommends treatment for all cases of acute disease (including congenital disease) regardless of age, and for chronic disease in patients up to age 50 who have not progressed to cardiomyopathy. In patients older than 50, treatment should be determined after weighing the potential risks and benefits (see Table 2).18

The success of treatment is determined in part by the phase of the disease. Cure rates in patients treated with either nifurtimox or benznidazole during the acute phase range from 65% to 80%.17 Chronic disease shows less of a response to traditional antiparasitic drug regimens, but higher rates of success are seen in younger patients.5 According to current estimates, successful treatment of chronic disease is limited to 15% to 30% patients.17 Treatment of congenital Chagas disease should begin as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed, and cure rates are greater than 90% if patients are treated within the first year of life.10 Treating congenital Chagas disease is important because the infection can be passed to future generations even if the disease never manifests with symptoms.19 However, if an expecting mother has known Chagas disease, antiparasitic medications are not recommended during the pregnancy because of a lack of fetal safety data for the two antiparasitic agents.20 Instead, it is recommended that women of childbearing age be treated before pregnancy, as rates of congenital infection are 25 times lower in women who are treated than in those who are not.21

PRE- AND POSTEXPOSURE PATIENT EDUCATION

Patient education mainly focuses on how to prevent Chagas disease and prognosis once diagnosed. During travel to endemic areas, the use of insecticides and residing in well-built households are the most important prevention measures. No vaccine is available, and primary chemoprophylaxis of persons visiting endemic areas is not recommended due to the low risk for infection and concerns about adverse effects.13

The survival rate of those who remain in the indeterminate phase is the same as that of the general population. However, findings that most strongly predict mortality include ventricular tachycardia, cardiomegaly, congestive heart failure (NYHA class III/IV), left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and male sex.10 Patients diagnosed with Chagas disease should be strongly encouraged not to donate blood or organs.10 Some organ and blood donation organizations selectively or universally screen donated specimens; however, this screening is not required by law.5 Family members of those diagnosed with the disease should also be tested, especially if the patient is a woman who has children or who plans to become pregnant.10

FOLLOW-UP

In patients confirmed to have Chagas disease but without symptoms and a normal ECG, further initial evaluation is not required.10 An annual history, physical exam, and ECG should be done. Those who have symptoms or ECG changes should have a complete cardiac work-up, including a 24-hour ambulatory ECG, exercise stress test, and echocardiogram to determine functional capacity. A barium swallow, barium enema, esophageal manometry, and endoscopy may be indicated in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms of Chagas disease but otherwise are not recommended. Patients taking antiparasitic drugs should have a CBC and CMP at the start of treatment and then bimonthly until the end of treatment to monitor for rare bone marrow suppression. Nifurtimox and benznidazole are also known to be mutagenic and increase the risk for lymphoma in animal studies, but this risk has not been documented in humans.10

CONCLUSION

Chagas disease is considered one of the neglected tropical diseases due to its high prevalence, chronic course, debilitating symptoms, and association with poverty.7 It is evident that incidence and prevalence of Chagas disease in the US are increasing due to recent immigration and mother-to-child transmission. Therefore, family practice clinicians must be able to recognize the red flags that suggest a T cruzi infection.5,9 Enhanced awareness of Chagas disease among health care providers will lead to better symptom control and cure rates for affected patients and may also prevent congenital infections. These efforts could serve to remove Chagas disease from the list of neglected tropical diseases.

1. Hotez PJ, Dumonteil E, Betancourt Cravioto M, et al. An unfolding tragedy of Chagas disease in North America. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013; 7(10):e2300.

2. Verani JR, Seitz A, Gilman RH, et al. Geographic variation in the sensitivity of recombinant antigen-based rapid tests for chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(3):410-415.

3. Malik LH, Singh GD, Amsterdam EA. The epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management of Chagas heart disease. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38(9):565-569.

4. World Health Organization. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). Fact sheet. Updated March 2016. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/. Accessed October 20, 2016.

5. Bern C, Kjos S, Yabsley MJ, Montgomery SP. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas’ disease in the United States. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011; 24(4):655-681.

6. Stimpert KK, Montgomery SP. Physician awareness of Chagas disease, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(5):871-872.

7. Hotez PJ. Neglected parasitic infections and poverty in the United States. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(9):e3012.

8. Goupil LS, McKerrow JH. Introduction: drug discovery and development for neglected diseases. Chem Rev. 2014;114(22):11131-11137.

9. Montgomery SP, Starr MC, Cantey P, et al. Neglected parasitic infections in the United States: Chagas disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014; 90(5):814-818.

10. Bern C, Montgomery SP, Herwaldt BL, et al. Evaluation and treatment of Chagas disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(18):2171-2181.

11. de Oliveira AP, Bernardo CR, Camargo AV, et al. Genetic susceptibility to cardiac and digestive clinical forms of chronic Chagas disease: involvement of the CCR5 59029 A/G polymorphism. PLoS One. 2015; 10(11):e0141847.

12. Apt W, Arribada A, Zulantay I, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi burden, genotypes, and clinical evaluation of Chilean patients with chronic Chagas cardiopathy. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(8):3007-3018.

13. Kirchhoff LV. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis): Background, pathophysiology, epidemiology. Emedicine.medscape.com. 2015. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/214581-overview. Accessed October 20, 2016.

14. Knipe H, St-Amant M. Chagas disease. Radiopaedia.org. 2015. http://radiopaedia.org/articles/chagas-disease. Accessed October 20, 2016.

15. Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Rassi SG. Predictors of mortality in chronic Chagas disease: a systematic review of observational studies. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1101-1108.

16. Gomes YM, Lorena VM, Luquetti AO. Diagnosis of Chagas disease: what has been achieved? What remains to be done with regard to diagnosis and follow up studies? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009; 104(suppl 1):115-121.

17. Molina I, Gómez i Prat J, Salvador F, et al. Randomized trial of posaconazole and benznidazole for chronic Chagas’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1899-1908.

18. CDC. Parasites – American trypanosomiasis (also known as Chagas Disease). Antiparasitic Treatment. Resources For Health Professionals. www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/health_professionals/tx.html. Accessed October 20, 2016.

19. Carlier Y, Truyens C. Congenital Chagas disease as an ecological model of interactions between Trypanosoma cruzi parasites, pregnant women, placenta and fetuses. Acta Trop. 2015;151:103-115.

20. Moscatelli G, Moroni S, García-Bournissen F, et al. Prevention of congenital Chagas through treatment of girls and women of childbearing age. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110(4):507-509.

21. Fabbro D, Danesi E, Olivera V, et al. Trypanocide treatment of women infected with Trypanosoma cruzi and its effect on preventing congenital Chagas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(11):e3312.

1. Hotez PJ, Dumonteil E, Betancourt Cravioto M, et al. An unfolding tragedy of Chagas disease in North America. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013; 7(10):e2300.

2. Verani JR, Seitz A, Gilman RH, et al. Geographic variation in the sensitivity of recombinant antigen-based rapid tests for chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(3):410-415.

3. Malik LH, Singh GD, Amsterdam EA. The epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management of Chagas heart disease. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38(9):565-569.

4. World Health Organization. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). Fact sheet. Updated March 2016. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/. Accessed October 20, 2016.

5. Bern C, Kjos S, Yabsley MJ, Montgomery SP. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas’ disease in the United States. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011; 24(4):655-681.

6. Stimpert KK, Montgomery SP. Physician awareness of Chagas disease, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(5):871-872.

7. Hotez PJ. Neglected parasitic infections and poverty in the United States. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(9):e3012.

8. Goupil LS, McKerrow JH. Introduction: drug discovery and development for neglected diseases. Chem Rev. 2014;114(22):11131-11137.

9. Montgomery SP, Starr MC, Cantey P, et al. Neglected parasitic infections in the United States: Chagas disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014; 90(5):814-818.

10. Bern C, Montgomery SP, Herwaldt BL, et al. Evaluation and treatment of Chagas disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(18):2171-2181.

11. de Oliveira AP, Bernardo CR, Camargo AV, et al. Genetic susceptibility to cardiac and digestive clinical forms of chronic Chagas disease: involvement of the CCR5 59029 A/G polymorphism. PLoS One. 2015; 10(11):e0141847.

12. Apt W, Arribada A, Zulantay I, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi burden, genotypes, and clinical evaluation of Chilean patients with chronic Chagas cardiopathy. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(8):3007-3018.

13. Kirchhoff LV. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis): Background, pathophysiology, epidemiology. Emedicine.medscape.com. 2015. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/214581-overview. Accessed October 20, 2016.

14. Knipe H, St-Amant M. Chagas disease. Radiopaedia.org. 2015. http://radiopaedia.org/articles/chagas-disease. Accessed October 20, 2016.

15. Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Rassi SG. Predictors of mortality in chronic Chagas disease: a systematic review of observational studies. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1101-1108.

16. Gomes YM, Lorena VM, Luquetti AO. Diagnosis of Chagas disease: what has been achieved? What remains to be done with regard to diagnosis and follow up studies? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009; 104(suppl 1):115-121.

17. Molina I, Gómez i Prat J, Salvador F, et al. Randomized trial of posaconazole and benznidazole for chronic Chagas’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1899-1908.

18. CDC. Parasites – American trypanosomiasis (also known as Chagas Disease). Antiparasitic Treatment. Resources For Health Professionals. www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/health_professionals/tx.html. Accessed October 20, 2016.

19. Carlier Y, Truyens C. Congenital Chagas disease as an ecological model of interactions between Trypanosoma cruzi parasites, pregnant women, placenta and fetuses. Acta Trop. 2015;151:103-115.

20. Moscatelli G, Moroni S, García-Bournissen F, et al. Prevention of congenital Chagas through treatment of girls and women of childbearing age. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110(4):507-509.

21. Fabbro D, Danesi E, Olivera V, et al. Trypanocide treatment of women infected with Trypanosoma cruzi and its effect on preventing congenital Chagas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(11):e3312.

Which treatments are safe and effective for chronic sinusitis?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

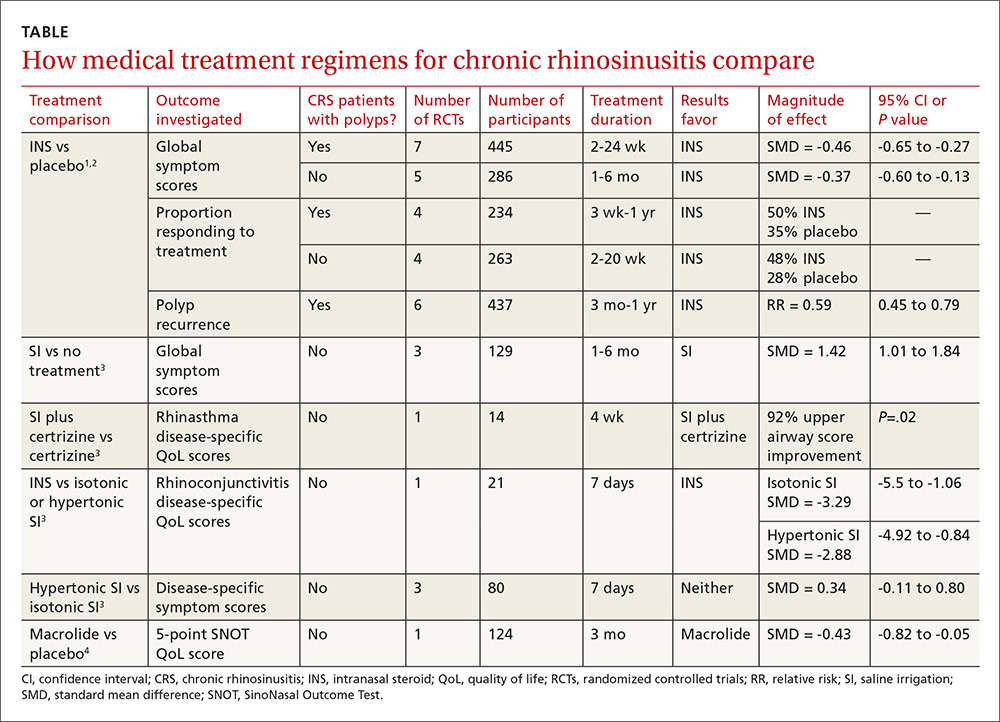

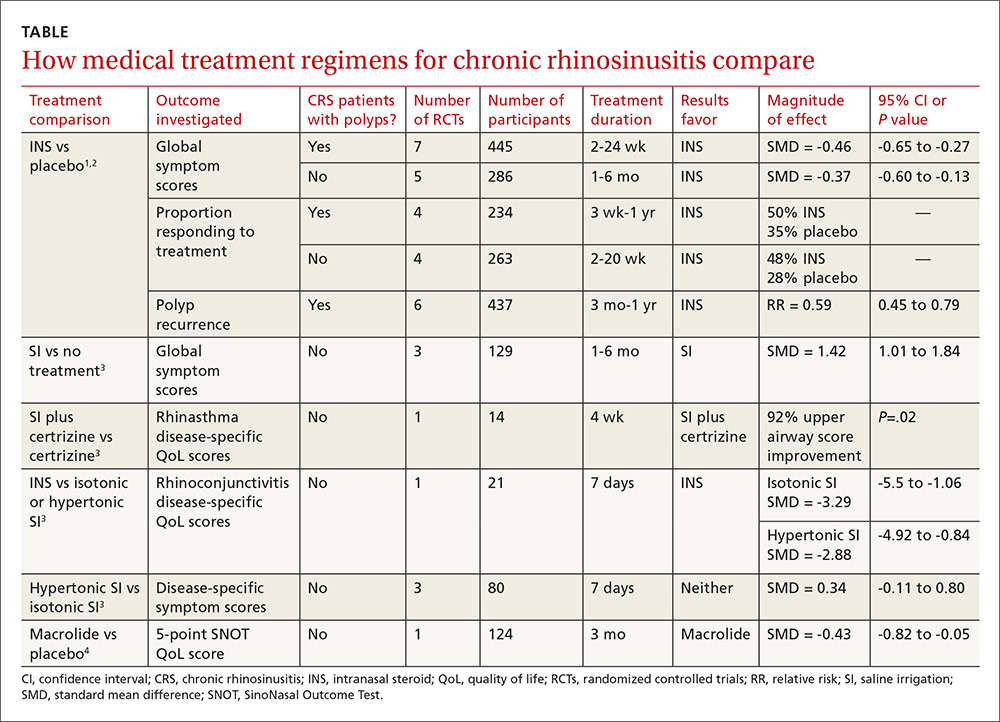

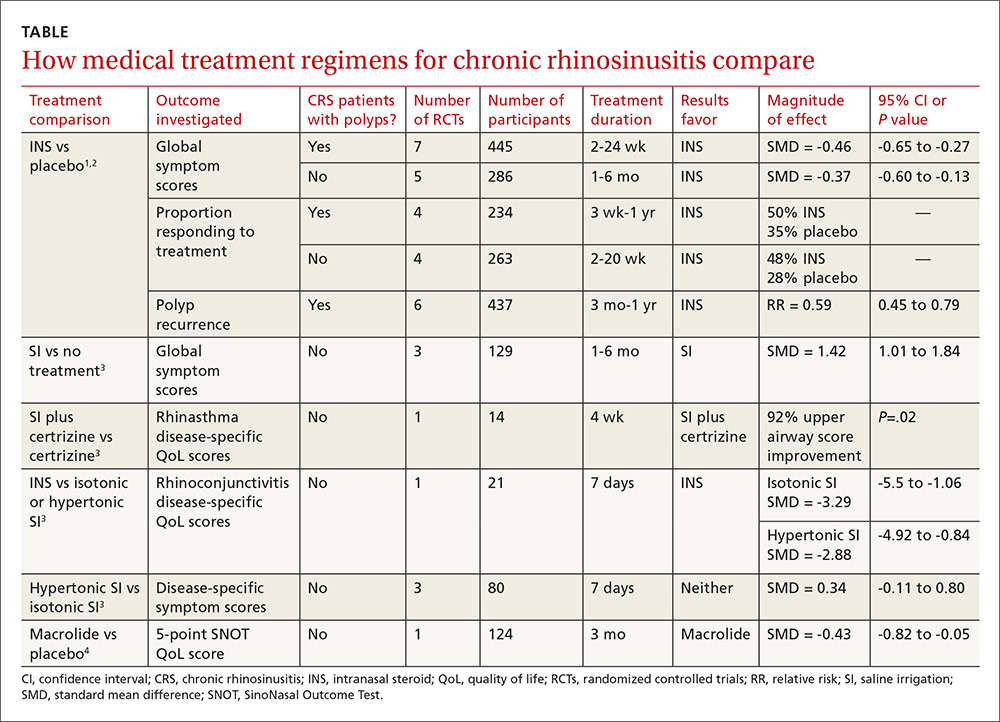

For adults with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), intranasal steroid (INS) therapy is more likely than placebo to improve symptoms (50% vs 32%; strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic reviews).

Nasal saline irrigation (SI) alleviates symptoms better than no therapy (SOR: A, systematic reviews), but it’s probably not as effective as INS treatment (SOR: B, randomized controlled trial [RCT] with wide confidence interval).

Long-term (12 weeks) macrolide therapy doesn’t alter patient-oriented quality-of-life measures (SOR: A, systematic reviews).

Endoscopic sinus surgery improves CRS symptoms—nasal obstruction, discharge, and facial pain—over baseline (SOR: A, systematic reviews). Surgery and medical therapy appear about equivalent in terms of symptom improvement and quality-of-life measures (SOR: B, systematic reviews of low-quality RCTs).