User login

Preventing infection after cesarean delivery: Evidence-based guidance

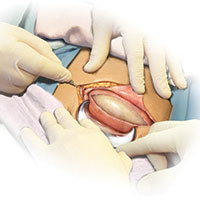

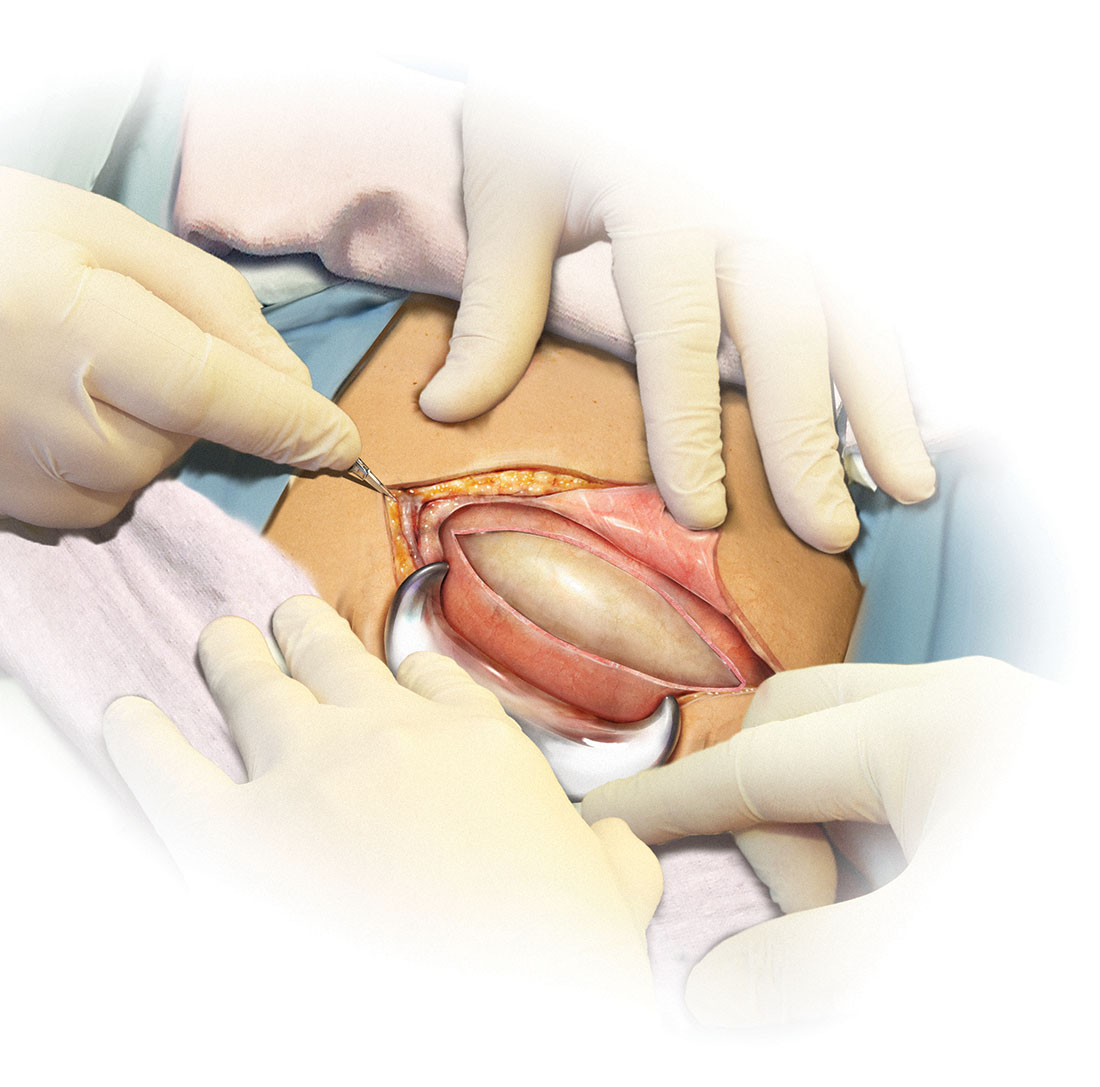

Cesarean delivery is now the most commonly performed major operation in hospitals across the United States. Approximately 30% of the 4 million deliveries that occur each year are by cesarean. Endometritis and wound infection (superficial and deep surgical site infection) are the most common postoperative complications of cesarean delivery. These 2 infections usually can be treated in a straightforward manner with antibiotics or surgical drainage. In some cases, however, they can lead to serious sequelae, such as pelvic abscess, septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis, and wound dehiscence/evisceration, thereby prolonging the patient’s hospitalization and significantly increasing medical expenses.

Accordingly, in the past 50 years many investigators have proposed various specific measures to reduce the risk of postcesarean infection. In this article, we critically evaluate 2 of these major interventions: methods of skin preparation and administration of prophylactic antibiotics. In part 2 of this series next month, we will review the evidence regarding preoperative bathing with an antiseptic, preoperative vaginal cleansing with an antiseptic solution, methods of placental extraction, closure of the deep subcutaneous layer of the abdomen, and closure of the skin.

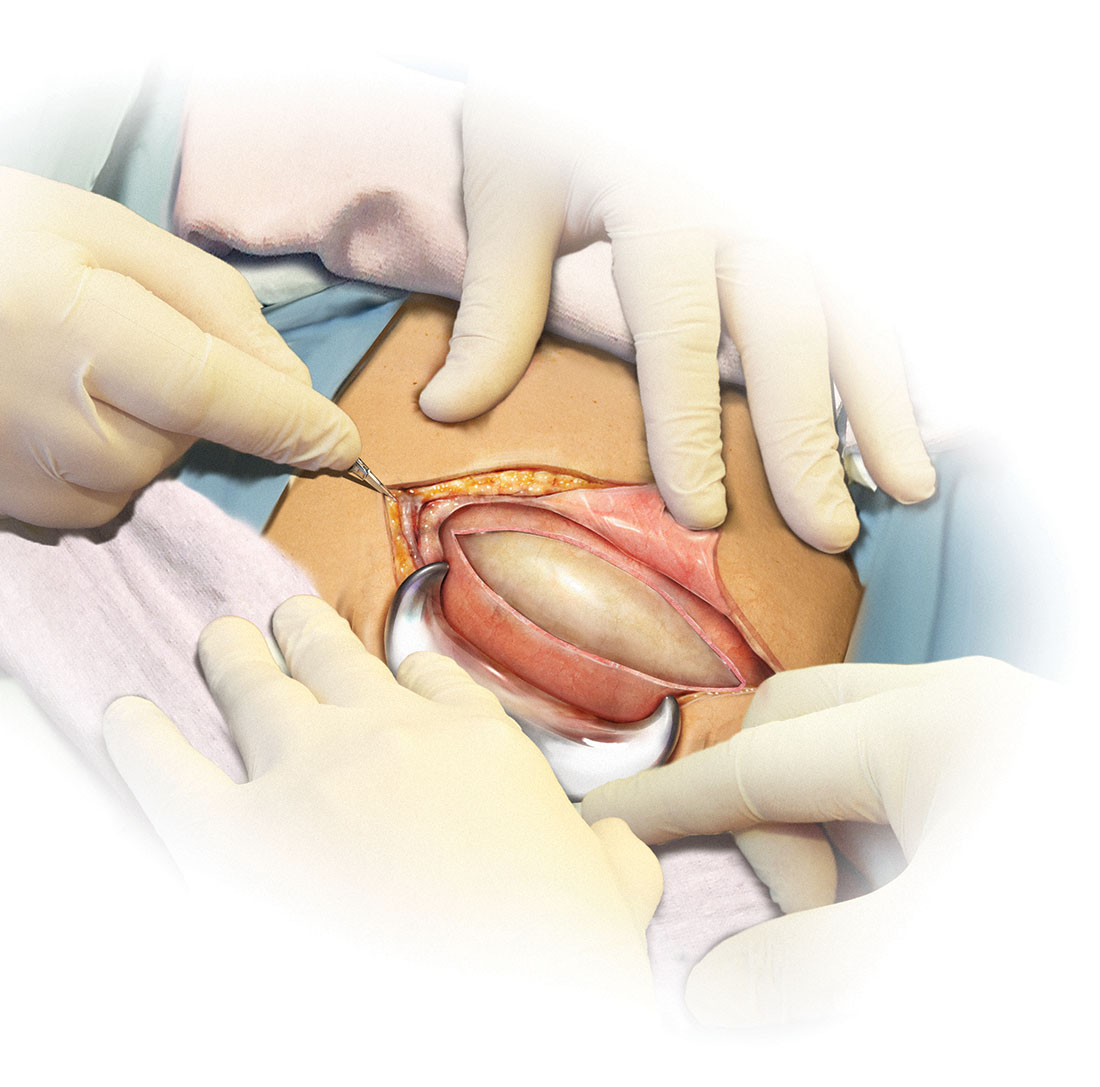

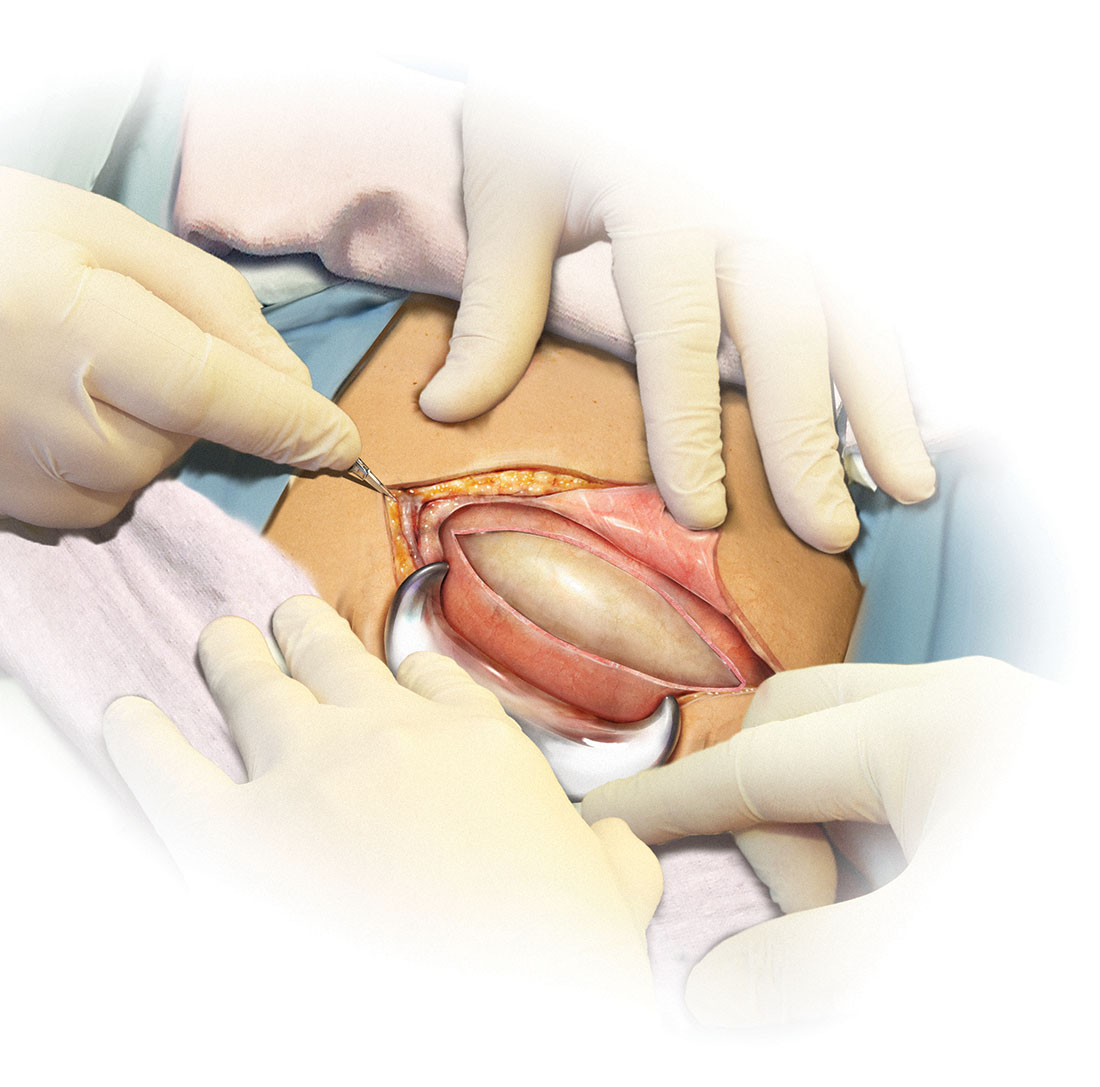

CASE Cesarean delivery required for nonprogressing labor

A 26-year-old obese primigravid woman, body mass index (BMI) 37 kg m2, at 40 weeks’ gestation has been in labor for 20 hours. Her membranes have been ruptured for 16 hours. Her cervix is completely effaced and is 7 cm dilated. The fetal head is at −1 cm station. Her cervical examination findings have not changed in 4 hours despite adequate uterine contractility documented by intrauterine pressure catheter. You are now ready to proceed with cesarean delivery, and you want to do everything possible to prevent the patient from developing a postoperative infection.

What are the best practices for postcesarean infection prevention in this patient?

Skin preparation

Adequate preoperative skin preparation is an important first step in preventing post‑ cesarean infection.

How should you prepare the patient’s skin for surgery?

Two issues to address when preparing the abdominal wall for surgery are hair removal and skin cleansing. More than 40 years ago, Cruse and Foord definitively answered the question about hair removal.1 In a landmark cohort investigation of more than 23,000 patients having many different types of operative procedures, they demonstrated that shaving the hair on the evening before surgery resulted in a higher rate of wound infection than clipping the hair, removing the hair with a depilatory cream just before surgery, or not removing the hair at all.

Three recent investigations have thoughtfully addressed the issue of skin cleansing. Darouiche and colleagues conducted a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial comparing chlorhexidine-alcohol with povidone-iodine for skin preparation before surgery.2 Their investigation included 849 patients having many different types of surgical procedures, only a minority of which were in obstetric and gynecologic patients. They demonstrated fewer superficial wound infections in patients in the chlorhexidine-alcohol group (4.2% vs 8.6%, P = .008). Of even greater importance, patients in the chlorhexidine-alcohol group had fewer deep wound infections (1% vs 3%, P = .005).

Ngai and co-workers recently reported the results of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in which women undergoing nonurgent cesarean delivery had their skin cleansed with povidone-iodine with alcohol, chlorhexidine with alcohol, or the sequential combination of both solutions.3 The overall rate of surgical site infection was just 4.3%. The 3 groups had comparable infection rates and, accordingly, the authors were unable to conclude that one type of skin preparation was superior to the other.

The most informative recent investigation was by Tuuli and colleagues, who evaluated 1,147 patients having cesarean delivery assigned to undergo skin preparation with either chlorhexidine-alcohol or iodine-alcohol.4 Unlike the study by Ngai and co-workers, in this study approximately 40% of the patients in each treatment arm had unscheduled, urgent cesarean deliveries.3,4 Overall, the rate of infection in the chlorhexidine-alcohol group was 4.0% compared with 7.3% in the iodine-alcohol group (relative risk [RR], 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34–0.90, P = .02).

What the evidence says

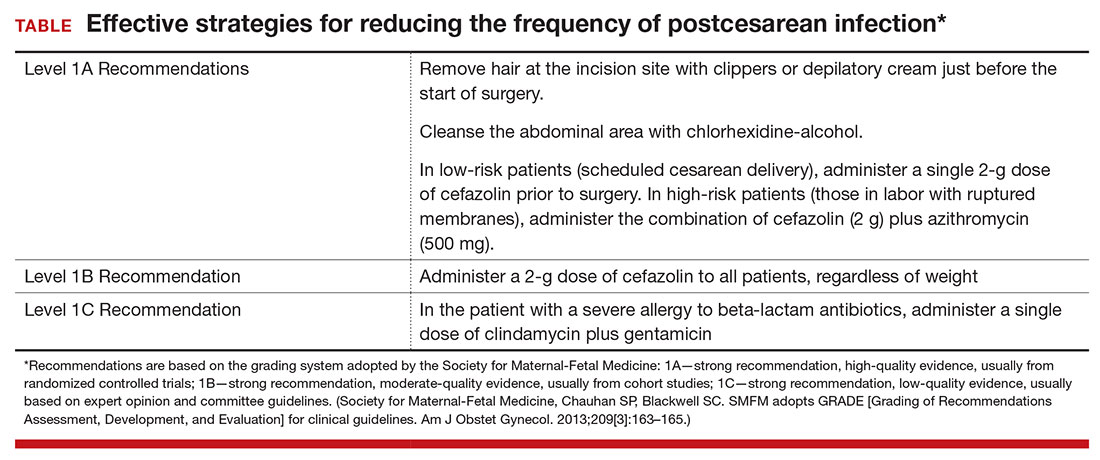

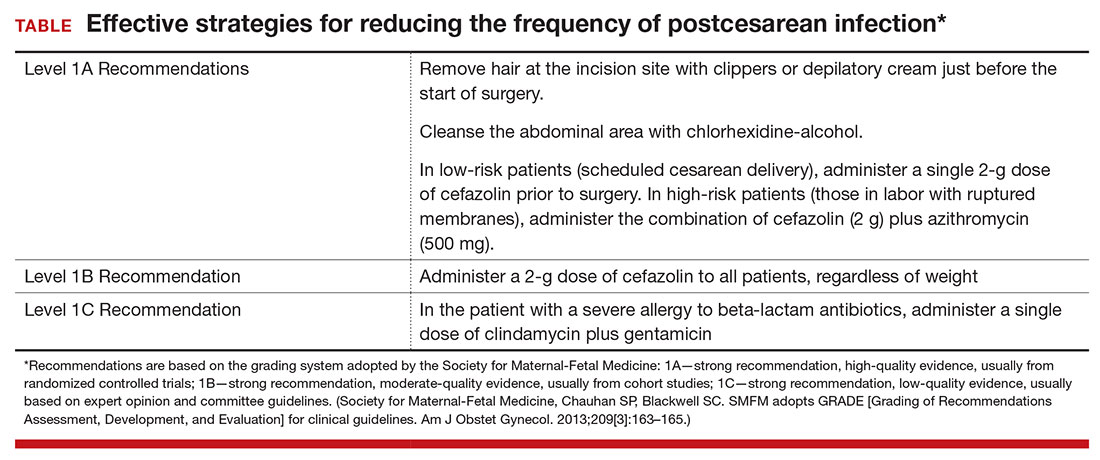

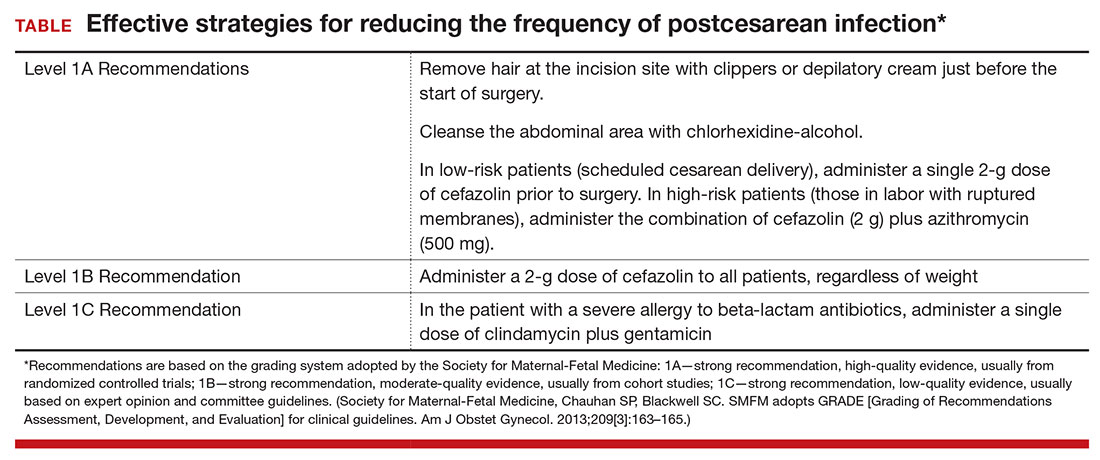

Based on the evidence cited above, we advise removing hair at the incision site with clippers or depilatory cream just before the start of surgery. The abdomen should then be cleansed with a chlorhexidine-alcohol solution (Level I Evidence, Level 1A Recommendation; TABLE).

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Questions to consider regarding antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean delivery include appropriateness of treatment, antibiotic(s) selection, timing of administration, dose, and special circumstances.

Should you give the patient prophylactic antibiotics?

Prophylactic antibiotics are justified for surgical procedures whenever 3 major criteria are met5:

- the surgical site is inevitably contaminated with bacteria

- in the absence of prophylaxis, the frequency of infection at the operative site is unacceptably high

- operative site infections have the potential to lead to serious, potentially life-threatening sequelae.

Without a doubt, all 3 of these criteria are fulfilled when considering either urgent or nonurgent cesarean delivery. When cesarean delivery follows a long labor complicated by ruptured membranes, multiple internal vaginal examinations, and internal fetal monitoring, the operative site is inevitably contaminated with hundreds of thousands of pathogenic bacteria. Even when cesarean delivery is scheduled to occur before the onset of labor and ruptured membranes, a high concentration of vaginal organisms is introduced into the uterine and pelvic cavities coincident with making the hysterotomy incision.6

In the era before prophylactic antibiotics were used routinely, postoperative infection rates in some highly indigent patient populations approached 85%.5 Finally, as noted previously, postcesarean endometritis may progress to pelvic abscess formation, septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis, and septic shock; wound infections may be complicated by dehiscence and evisceration.

When should you administer antibiotics: Before the surgical incision or after cord clamping?

More than 50 years ago, Burke conducted the classic sequence of basic science experiments that forms the foundation for use of prophylactic antibiotics.7 Using a guinea pig model, he showed that prophylactic antibiotics exert their most pronounced effect when they are administered before the surgical incision is made and before bacterial contamination occurs. Prophylaxis that is delayed more than 4 hours after the start of surgery will likely be ineffective.

Interestingly, however, when clinicians first began using prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean delivery, some investigators expressed concern about the possible exposure of the neonate to antibiotics just before delivery—specifically, whether this exposure would increase the frequency of evaluations for suspected sepsis or would promote resistance among organisms that would make neonatal sepsis more difficult to treat.

Gordon and colleagues published an important report in 1979 that showed that preoperative administration of ampicillin did not increase the frequency of immediate or delayed neonatal infections.8 However, delaying the administration of ampicillin until after the umbilical cord was clamped was just as effective in preventing post‑cesarean endometritis. Subsequently, Cunningham and co-workers showed that preoperative administration of prophylactic antibiotics significantly increased the frequency of sepsis workups in exposed neonates compared with infants with no preoperative antibiotic exposure (28% vs 15%; P<.025).9 Based on these 2 reports, obstetricians adopted a policy of delaying antibiotic administration until after the infant’s umbilical cord was clamped.

In 2007, Sullivan and colleagues challenged this long-standing practice.10 In a carefully designed prospective, randomized, double-blind trial, they showed that patients who received preoperative cefazolin had a significant reduction in the frequency of endometritis compared with women who received the same antibiotic after cord clamping (1% vs 5%; RR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.2–0.94). The rate of wound infection was lower in the preoperative antibiotic group (3% vs 5%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance. The total infection-related morbidity was significantly reduced in women who received antibiotics preoperatively (4.0% vs 11.5%; RR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.18–0.87). Additionally, there was no increase in the frequency of proven or suspected neonatal infection in the infants exposed to antibiotics before delivery.

Subsequent to the publication by Sullivan and colleagues, other reports have confirmed that administration of antibiotics prior to surgery is superior to administration after clamping of the umbilical cord.10–12 Thus, we have come full circle back to Burke’s principle established more than a half century ago.7

Which antibiotic(s) should you administer for prophylaxis, and how many doses?

In an earlier review, one of us (PD) examined the evidence regarding choice of antibiotics and number of doses, concluding that a single dose of a first-generation cephalosporin, such as cefazolin, was the preferred regimen.5 The single dose was comparable in effectiveness to 2- or 3-dose regimens and to single- or multiple-dose regimens of broader-spectrum agents. For more than 20 years now, the standard of care for antibiotic prophylaxis has been a single 1- to 2-g dose of cefazolin.

Several recent reports, however, have raised the question of whether the prophylactic effect could be enhanced if the spectrum of activity of the antibiotic regimen was broadened to include an agent effective against Ureaplasma species.

Tita and colleagues evaluated an indigent patient population with an inherently high rate of postoperative infection; they showed that adding azithromycin 500 mg to cefazolin significantly reduced the rate of postcesarean endometritis.13 In a follow-up report from the same institution, Tita and co-workers demonstrated that adding azithromycin also significantly reduced the frequency of wound infection.14 In both of these investigations, the antibiotics were administered after cord clamping.

In a subsequent report, Ward and Duff15 showed that the combination of azithromycin plus cefazolin administered preoperatively resulted in a very low rate of both endometritis and wound infection in a population similar to that studied by Tita et al.13,14

Very recently, Tita and associates published the results of the Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis (C/SOAP) trial conducted at 14 US hospitals.16 This study included 2,013 women undergoing cesarean delivery during labor or after membrane rupture who were randomly assigned to receive intravenous azithromycin 500 mg (n = 1,019) or placebo (n = 994). All women also received standard antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin. The primary outcome (a composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infection within 6 weeks) was significantly lower in the azithromycin group than in the placebo group (6.1% vs 12.0%, P<.001). In addition, there were significant differences between the treatment groups in the rates of endometritis (3.8% in the azithromycin group vs 6.1% in the placebo group, P = .02) as well as in the rates of wound infection (2.4% vs 6.6%, respectively, P<.001). Of additional note, there were no differences between the 2 groups in the composite neonatal outcome of death and serious neonatal complications (14.3% vs 13.6%, P = .63).The investigators concluded that extended-spectrum prophylaxis with adjunctive azithromycin safely reduces infection rates without raising the risk of neonatal adverse outcomes.

What the evidence says

We conclude that all patients, even those having a scheduled cesarean before the onset of labor or ruptured membranes, should receive prophylactic antibiotics in a single dose administered preoperatively rather than after cord clamping (Level I Evidence, Level 1A Recommendation; TABLE). In high-risk populations (eg, women in labor with ruptured membranes who are having an urgent cesarean), for whom the baseline risk of infection is high, administer the combination of cefazolin plus azithromycin in lieu of cefazolin alone (Level I Evidence, Level 1A Recommendation; TABLE).

If the patient has a history of an immediate hypersensitivity reaction to beta-lactam antibiotics, we recommend the combination of clindamycin (900 mg) plus gentamicin (1.5 mg/kg) as a single infusion prior to surgery. We base this recommendation on the need to provide reasonable coverage against a broad range of pathogens. Clindamycin covers gram-positive aerobes, such as staphylococci species and group B streptococci, and anaerobes; gentamicin covers aerobic gram-negative bacilli. A single agent, such as clindamycin or metronidazole, does not provide the broad-based coverage necessary for effective prophylaxis (Level III Evidence, Level 1C Recommendation; TABLE).

If the patient is overweight or obese, should you modify the antibiotic dose?

The prevalence of obesity in the United States continues to increase. One-third of all US reproductive-aged women are obese, and 6% of women are extremely obese.17 Obesity increases the risk of postcesarean infection 3- to 5- fold.18 Because both pregnancy and obesity increase the total volume of a drug’s distribution, achieving adequate antibiotic tissue concentrations may be hindered by a dilutional effect. Furthermore, pharmacokinetic studies consistently have shown that the tissue concentration of an antibiotic—which, ideally, should be above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for common bacteria—determines the susceptibility of those tissues to infection, regardless of whether the serum concentration of the antibiotic is in the therapeutic range.19

These concerns have led to several recent investigations evaluating different doses of cefazolin for obese patients. Pevzner and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study of 29 women having a scheduled cesarean delivery.20 The patients were divided into 3 groups: lean (BMI <30 kg m2), obese (BMI 30.0–39.9 kg m2), and extremely obese (BMI >40 kg m2). All women received a 2-g dose of cefazolin 30 to 60 minutes before surgery. Cefazolin concentrations in adipose tissue obtained at the time of skin incision were inversely proportional to maternal BMI (r, −0.67; P<.001). All specimens demonstrated a therapeutic concentration (>1 µg/g) of cefazolin for gram-positive cocci, but 20% of the obese women and 33% of the extremely obese women did not achieve the MIC (>4 µg/g) for gram-negative bacilli (P = .29 and P = .14, respectively). At the time of skin closure, 20% of obese women and 44% of extremely obese women did not have tissue concentrations that exceeded the MIC for gram-negative bacteria.

Swank and associates conducted a prospective cohort study that included 28 women.18 They demonstrated that, after a 2-g dose of cefazolin, only 20% of the obese women (BMI 30–40 kg m2) and 0% of the extremely obese women (BMI >40 kg m2) achieved an adipose tissue concentration that exceeded the MIC for gram-negative rods (8 µg/mL). However, 100% and 71.4%, respectively, achieved such a tissue concentration after a 3-g dose. When the women were stratified by actual weight, there was a statistically significant difference between those who weighed less than 120 kg and those who weighed more than 120 kg. Seventy-nine percent of the former had a tissue concentration of cefazolin greater than 8 µg/mL compared with 0% of the women who weighed more than 120 kg. Based on these observations, the authors recommended a 3-g dose of cefazolin for women who weigh more than 120 kg.

In a double-blind RCT with 26 obese women (BMI ≥30 kg m2), Young and colleagues demonstrated that, at the time of hysterotomy and fascial closure, significantly higher concentrations of cefazolin were found in the adipose tissue of obese women who received a 3-g dose of antibiotic compared with those who received a 2-g dose.21 However, all concentrations of cefazolin were consistently above the MIC of cefazolin for gram-positive cocci (1 µg/g) and gram-negative bacilli (4 µg/g). Further, Maggio and co-workers conducted a double-blind RCT comparing a 2-g dose of cefazolin versus a 3-g dose in 57 obese women (BMI ≥30 kg m2).22 They found no statistically significant difference in the percentage of women who had tissue concentrations of cefazolin greater than the MIC for gram-positive cocci (8 µg/g). All samples were above the MIC of cefazolin for gram-negative bacilli (2 µg/g). Based on these data, these investigators did not recommend increasing the dose of cefazolin from 2 g to 3 g in obese patients.21,22

The studies discussed above are difficult to compare for 3 reasons. First, each study used a different MIC of cefazolin for both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Second, the authors sampled different maternal tissues or serum at varying times during the cesarean delivery. Third, the studies did not specifically investigate, or were not powered sufficiently to address, the more important clinical outcome of surgical site infection. In a recent historical cohort study, Ward and Duff were unable to show that increasing the dose of cefazolin to 2 g in all women with a BMI <30 kg m2 and to 3 g in all women with a BMI >30 kg m2 reduced the rate of endometritis and wound infection below the level already achieved with combined prophylaxis with cefazolin (1 g) plus azithromycin (500 mg).15

Sutton and colleagues recently assessed the pharmacokinetics of azithromycin when used as prophylaxis for cesarean delivery.23 They studied 30 women who had a scheduled cesarean delivery and who received a 500-mg intravenous dose of azithromycin that was initiated 15, 30, or 60 minutes before the surgical incision and then infused over 1 hour. They obtained maternal plasma samples multiple times during the first 8 hours after surgery. They also obtained samples of amniotic fluid, placenta, myometrium, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood intraoperatively. The median concentration of azithromycin in adipose tissue was 102 ng/g, which is below the MIC50 for Ureaplasma species (250 ng/mL). The median concentration in myometrial tissue was 402 ng/g. The concentration in maternal plasma consistently exceeded the MIC50 for Ureaplasma species.

What the evidence says

All women, regardless of weight,

CASE Resolved

For the 26-year-old obese laboring patient about to undergo cesarean delivery, reasonable steps for prevention of infection include removing the hair at the incision site with clippers or depilatory cream immediately prior to the start of surgery; cleansing the abdomen with a chlorhexidine-alcohol solution; and administering cefazolin (2 g) plus azithromycin (500 mg) preoperatively.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Cruse PJ, Foord R. A five‑year prospective study of 23,649 surgical wounds. Arch Surg. 1973;107(2):206–210.

- Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, et al. Chlorhexidine‑alcohol versus povidone‑iodine for surgical‑site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):18–26.

- Ngai IM, Van Arsdale A, Govindappagari S, et al. Skin preparation for prevention of surgical site infection after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(6):1251–1257.

- Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing skin antiseptic agents at cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):647–655.

- Duff P. Prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a simple cost‑effective strategy for prevention of postoperative morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157(4 pt 1):794–798.

- Dinsmoor MJ, Gilbert S, Landon MB, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal‑Fetal Medicine Units Network. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis for nonlaboring cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(4):752–756.

- Burke JF. The effective period of preventive antibiotic action in experimental incisions and dermal lesions. Surgery. 1961;50:161–168.

- Gordon HR, Phelps D, Blanchard K. Prophylactic cesarean section antibiotics: maternal and neonatal morbidity before or after cord clamping. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(2):151–156.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, DePalma RT, Roark M, Rosenfeld CR. Perioperative antimicrobials for cesarean delivery: before or after cord clamping? Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62(2):151–154.

- Sullivan SA, Smith T, Chang E, Hulsey T, Vandorsten JP, Soper D. Administration of cefazolin prior to skin incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in preventing postcesarean infectious morbidity: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(5):455.e1–e5.

- Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghulmiyah L, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):301.e1–e6.

- Owens SM, Brozanski BS, Meyn LA, Wiesenfeld HC. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for cesarean delivery before skin incision. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):573–579.

- Tita AT, Hauth JC, Grimes A, Owen J, Stamm AM, Andrews WW. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended‑spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):51–56.

- Tita AT, Owen J, Stamm AM, Grimes A, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Impact of extended‑spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis on incidence of postcesarean surgical wound infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):303.e1–e3.

- Ward E, Duff P. A comparison of 3 antibiotic regimens for prevention of postcesarean endometritis: an historical cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):751.e1–e4.

- Tita AT, Szychowski JM, Boggess K, et al; C/SOAP Trial Consortium. Adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(13):1231–1241.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegel KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006:295(13):1549–1555.

- Swank ML, Wing DA, Nicolau DP, McNulty JA. Increased 3‑gram cefazolin dosing for cesarean delivery prophylaxis in obese women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(3):415.e1–e8.

- Liu P, Derendorf H. Antimicrobial tissue concentrations. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003:17(3):599–613.

- Pevzner L, Swank M, Krepel C, Wing DA, Chan K, Edmiston CE Jr. Effects of maternal obesity on tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):877–882.

- Young OM, Shaik IH, Twedt R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of cefazolin prophylaxis in obese gravidae at time of cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):541.e1–e7.

- Maggio L, Nicolau DP, DaCosta M, Rouse DJ, Hughes BL. Cefazolin prophylaxis in obese women undergoing cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1205–1210.

- Sutton AL, Acosta EP, Larson KB, Kerstner‑Wood CD, Tita AT, Biggio JR. Perinatal pharmacokinetics of azithromycin for cesarean prophylaxis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):812. e1–e6.

Cesarean delivery is now the most commonly performed major operation in hospitals across the United States. Approximately 30% of the 4 million deliveries that occur each year are by cesarean. Endometritis and wound infection (superficial and deep surgical site infection) are the most common postoperative complications of cesarean delivery. These 2 infections usually can be treated in a straightforward manner with antibiotics or surgical drainage. In some cases, however, they can lead to serious sequelae, such as pelvic abscess, septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis, and wound dehiscence/evisceration, thereby prolonging the patient’s hospitalization and significantly increasing medical expenses.

Accordingly, in the past 50 years many investigators have proposed various specific measures to reduce the risk of postcesarean infection. In this article, we critically evaluate 2 of these major interventions: methods of skin preparation and administration of prophylactic antibiotics. In part 2 of this series next month, we will review the evidence regarding preoperative bathing with an antiseptic, preoperative vaginal cleansing with an antiseptic solution, methods of placental extraction, closure of the deep subcutaneous layer of the abdomen, and closure of the skin.

CASE Cesarean delivery required for nonprogressing labor

A 26-year-old obese primigravid woman, body mass index (BMI) 37 kg m2, at 40 weeks’ gestation has been in labor for 20 hours. Her membranes have been ruptured for 16 hours. Her cervix is completely effaced and is 7 cm dilated. The fetal head is at −1 cm station. Her cervical examination findings have not changed in 4 hours despite adequate uterine contractility documented by intrauterine pressure catheter. You are now ready to proceed with cesarean delivery, and you want to do everything possible to prevent the patient from developing a postoperative infection.

What are the best practices for postcesarean infection prevention in this patient?

Skin preparation

Adequate preoperative skin preparation is an important first step in preventing post‑ cesarean infection.

How should you prepare the patient’s skin for surgery?

Two issues to address when preparing the abdominal wall for surgery are hair removal and skin cleansing. More than 40 years ago, Cruse and Foord definitively answered the question about hair removal.1 In a landmark cohort investigation of more than 23,000 patients having many different types of operative procedures, they demonstrated that shaving the hair on the evening before surgery resulted in a higher rate of wound infection than clipping the hair, removing the hair with a depilatory cream just before surgery, or not removing the hair at all.

Three recent investigations have thoughtfully addressed the issue of skin cleansing. Darouiche and colleagues conducted a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial comparing chlorhexidine-alcohol with povidone-iodine for skin preparation before surgery.2 Their investigation included 849 patients having many different types of surgical procedures, only a minority of which were in obstetric and gynecologic patients. They demonstrated fewer superficial wound infections in patients in the chlorhexidine-alcohol group (4.2% vs 8.6%, P = .008). Of even greater importance, patients in the chlorhexidine-alcohol group had fewer deep wound infections (1% vs 3%, P = .005).

Ngai and co-workers recently reported the results of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in which women undergoing nonurgent cesarean delivery had their skin cleansed with povidone-iodine with alcohol, chlorhexidine with alcohol, or the sequential combination of both solutions.3 The overall rate of surgical site infection was just 4.3%. The 3 groups had comparable infection rates and, accordingly, the authors were unable to conclude that one type of skin preparation was superior to the other.

The most informative recent investigation was by Tuuli and colleagues, who evaluated 1,147 patients having cesarean delivery assigned to undergo skin preparation with either chlorhexidine-alcohol or iodine-alcohol.4 Unlike the study by Ngai and co-workers, in this study approximately 40% of the patients in each treatment arm had unscheduled, urgent cesarean deliveries.3,4 Overall, the rate of infection in the chlorhexidine-alcohol group was 4.0% compared with 7.3% in the iodine-alcohol group (relative risk [RR], 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34–0.90, P = .02).

What the evidence says

Based on the evidence cited above, we advise removing hair at the incision site with clippers or depilatory cream just before the start of surgery. The abdomen should then be cleansed with a chlorhexidine-alcohol solution (Level I Evidence, Level 1A Recommendation; TABLE).

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Questions to consider regarding antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean delivery include appropriateness of treatment, antibiotic(s) selection, timing of administration, dose, and special circumstances.

Should you give the patient prophylactic antibiotics?

Prophylactic antibiotics are justified for surgical procedures whenever 3 major criteria are met5:

- the surgical site is inevitably contaminated with bacteria

- in the absence of prophylaxis, the frequency of infection at the operative site is unacceptably high

- operative site infections have the potential to lead to serious, potentially life-threatening sequelae.

Without a doubt, all 3 of these criteria are fulfilled when considering either urgent or nonurgent cesarean delivery. When cesarean delivery follows a long labor complicated by ruptured membranes, multiple internal vaginal examinations, and internal fetal monitoring, the operative site is inevitably contaminated with hundreds of thousands of pathogenic bacteria. Even when cesarean delivery is scheduled to occur before the onset of labor and ruptured membranes, a high concentration of vaginal organisms is introduced into the uterine and pelvic cavities coincident with making the hysterotomy incision.6

In the era before prophylactic antibiotics were used routinely, postoperative infection rates in some highly indigent patient populations approached 85%.5 Finally, as noted previously, postcesarean endometritis may progress to pelvic abscess formation, septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis, and septic shock; wound infections may be complicated by dehiscence and evisceration.

When should you administer antibiotics: Before the surgical incision or after cord clamping?

More than 50 years ago, Burke conducted the classic sequence of basic science experiments that forms the foundation for use of prophylactic antibiotics.7 Using a guinea pig model, he showed that prophylactic antibiotics exert their most pronounced effect when they are administered before the surgical incision is made and before bacterial contamination occurs. Prophylaxis that is delayed more than 4 hours after the start of surgery will likely be ineffective.

Interestingly, however, when clinicians first began using prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean delivery, some investigators expressed concern about the possible exposure of the neonate to antibiotics just before delivery—specifically, whether this exposure would increase the frequency of evaluations for suspected sepsis or would promote resistance among organisms that would make neonatal sepsis more difficult to treat.

Gordon and colleagues published an important report in 1979 that showed that preoperative administration of ampicillin did not increase the frequency of immediate or delayed neonatal infections.8 However, delaying the administration of ampicillin until after the umbilical cord was clamped was just as effective in preventing post‑cesarean endometritis. Subsequently, Cunningham and co-workers showed that preoperative administration of prophylactic antibiotics significantly increased the frequency of sepsis workups in exposed neonates compared with infants with no preoperative antibiotic exposure (28% vs 15%; P<.025).9 Based on these 2 reports, obstetricians adopted a policy of delaying antibiotic administration until after the infant’s umbilical cord was clamped.

In 2007, Sullivan and colleagues challenged this long-standing practice.10 In a carefully designed prospective, randomized, double-blind trial, they showed that patients who received preoperative cefazolin had a significant reduction in the frequency of endometritis compared with women who received the same antibiotic after cord clamping (1% vs 5%; RR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.2–0.94). The rate of wound infection was lower in the preoperative antibiotic group (3% vs 5%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance. The total infection-related morbidity was significantly reduced in women who received antibiotics preoperatively (4.0% vs 11.5%; RR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.18–0.87). Additionally, there was no increase in the frequency of proven or suspected neonatal infection in the infants exposed to antibiotics before delivery.

Subsequent to the publication by Sullivan and colleagues, other reports have confirmed that administration of antibiotics prior to surgery is superior to administration after clamping of the umbilical cord.10–12 Thus, we have come full circle back to Burke’s principle established more than a half century ago.7

Which antibiotic(s) should you administer for prophylaxis, and how many doses?

In an earlier review, one of us (PD) examined the evidence regarding choice of antibiotics and number of doses, concluding that a single dose of a first-generation cephalosporin, such as cefazolin, was the preferred regimen.5 The single dose was comparable in effectiveness to 2- or 3-dose regimens and to single- or multiple-dose regimens of broader-spectrum agents. For more than 20 years now, the standard of care for antibiotic prophylaxis has been a single 1- to 2-g dose of cefazolin.

Several recent reports, however, have raised the question of whether the prophylactic effect could be enhanced if the spectrum of activity of the antibiotic regimen was broadened to include an agent effective against Ureaplasma species.

Tita and colleagues evaluated an indigent patient population with an inherently high rate of postoperative infection; they showed that adding azithromycin 500 mg to cefazolin significantly reduced the rate of postcesarean endometritis.13 In a follow-up report from the same institution, Tita and co-workers demonstrated that adding azithromycin also significantly reduced the frequency of wound infection.14 In both of these investigations, the antibiotics were administered after cord clamping.

In a subsequent report, Ward and Duff15 showed that the combination of azithromycin plus cefazolin administered preoperatively resulted in a very low rate of both endometritis and wound infection in a population similar to that studied by Tita et al.13,14

Very recently, Tita and associates published the results of the Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis (C/SOAP) trial conducted at 14 US hospitals.16 This study included 2,013 women undergoing cesarean delivery during labor or after membrane rupture who were randomly assigned to receive intravenous azithromycin 500 mg (n = 1,019) or placebo (n = 994). All women also received standard antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin. The primary outcome (a composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infection within 6 weeks) was significantly lower in the azithromycin group than in the placebo group (6.1% vs 12.0%, P<.001). In addition, there were significant differences between the treatment groups in the rates of endometritis (3.8% in the azithromycin group vs 6.1% in the placebo group, P = .02) as well as in the rates of wound infection (2.4% vs 6.6%, respectively, P<.001). Of additional note, there were no differences between the 2 groups in the composite neonatal outcome of death and serious neonatal complications (14.3% vs 13.6%, P = .63).The investigators concluded that extended-spectrum prophylaxis with adjunctive azithromycin safely reduces infection rates without raising the risk of neonatal adverse outcomes.

What the evidence says

We conclude that all patients, even those having a scheduled cesarean before the onset of labor or ruptured membranes, should receive prophylactic antibiotics in a single dose administered preoperatively rather than after cord clamping (Level I Evidence, Level 1A Recommendation; TABLE). In high-risk populations (eg, women in labor with ruptured membranes who are having an urgent cesarean), for whom the baseline risk of infection is high, administer the combination of cefazolin plus azithromycin in lieu of cefazolin alone (Level I Evidence, Level 1A Recommendation; TABLE).

If the patient has a history of an immediate hypersensitivity reaction to beta-lactam antibiotics, we recommend the combination of clindamycin (900 mg) plus gentamicin (1.5 mg/kg) as a single infusion prior to surgery. We base this recommendation on the need to provide reasonable coverage against a broad range of pathogens. Clindamycin covers gram-positive aerobes, such as staphylococci species and group B streptococci, and anaerobes; gentamicin covers aerobic gram-negative bacilli. A single agent, such as clindamycin or metronidazole, does not provide the broad-based coverage necessary for effective prophylaxis (Level III Evidence, Level 1C Recommendation; TABLE).

If the patient is overweight or obese, should you modify the antibiotic dose?

The prevalence of obesity in the United States continues to increase. One-third of all US reproductive-aged women are obese, and 6% of women are extremely obese.17 Obesity increases the risk of postcesarean infection 3- to 5- fold.18 Because both pregnancy and obesity increase the total volume of a drug’s distribution, achieving adequate antibiotic tissue concentrations may be hindered by a dilutional effect. Furthermore, pharmacokinetic studies consistently have shown that the tissue concentration of an antibiotic—which, ideally, should be above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for common bacteria—determines the susceptibility of those tissues to infection, regardless of whether the serum concentration of the antibiotic is in the therapeutic range.19

These concerns have led to several recent investigations evaluating different doses of cefazolin for obese patients. Pevzner and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study of 29 women having a scheduled cesarean delivery.20 The patients were divided into 3 groups: lean (BMI <30 kg m2), obese (BMI 30.0–39.9 kg m2), and extremely obese (BMI >40 kg m2). All women received a 2-g dose of cefazolin 30 to 60 minutes before surgery. Cefazolin concentrations in adipose tissue obtained at the time of skin incision were inversely proportional to maternal BMI (r, −0.67; P<.001). All specimens demonstrated a therapeutic concentration (>1 µg/g) of cefazolin for gram-positive cocci, but 20% of the obese women and 33% of the extremely obese women did not achieve the MIC (>4 µg/g) for gram-negative bacilli (P = .29 and P = .14, respectively). At the time of skin closure, 20% of obese women and 44% of extremely obese women did not have tissue concentrations that exceeded the MIC for gram-negative bacteria.

Swank and associates conducted a prospective cohort study that included 28 women.18 They demonstrated that, after a 2-g dose of cefazolin, only 20% of the obese women (BMI 30–40 kg m2) and 0% of the extremely obese women (BMI >40 kg m2) achieved an adipose tissue concentration that exceeded the MIC for gram-negative rods (8 µg/mL). However, 100% and 71.4%, respectively, achieved such a tissue concentration after a 3-g dose. When the women were stratified by actual weight, there was a statistically significant difference between those who weighed less than 120 kg and those who weighed more than 120 kg. Seventy-nine percent of the former had a tissue concentration of cefazolin greater than 8 µg/mL compared with 0% of the women who weighed more than 120 kg. Based on these observations, the authors recommended a 3-g dose of cefazolin for women who weigh more than 120 kg.

In a double-blind RCT with 26 obese women (BMI ≥30 kg m2), Young and colleagues demonstrated that, at the time of hysterotomy and fascial closure, significantly higher concentrations of cefazolin were found in the adipose tissue of obese women who received a 3-g dose of antibiotic compared with those who received a 2-g dose.21 However, all concentrations of cefazolin were consistently above the MIC of cefazolin for gram-positive cocci (1 µg/g) and gram-negative bacilli (4 µg/g). Further, Maggio and co-workers conducted a double-blind RCT comparing a 2-g dose of cefazolin versus a 3-g dose in 57 obese women (BMI ≥30 kg m2).22 They found no statistically significant difference in the percentage of women who had tissue concentrations of cefazolin greater than the MIC for gram-positive cocci (8 µg/g). All samples were above the MIC of cefazolin for gram-negative bacilli (2 µg/g). Based on these data, these investigators did not recommend increasing the dose of cefazolin from 2 g to 3 g in obese patients.21,22

The studies discussed above are difficult to compare for 3 reasons. First, each study used a different MIC of cefazolin for both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Second, the authors sampled different maternal tissues or serum at varying times during the cesarean delivery. Third, the studies did not specifically investigate, or were not powered sufficiently to address, the more important clinical outcome of surgical site infection. In a recent historical cohort study, Ward and Duff were unable to show that increasing the dose of cefazolin to 2 g in all women with a BMI <30 kg m2 and to 3 g in all women with a BMI >30 kg m2 reduced the rate of endometritis and wound infection below the level already achieved with combined prophylaxis with cefazolin (1 g) plus azithromycin (500 mg).15

Sutton and colleagues recently assessed the pharmacokinetics of azithromycin when used as prophylaxis for cesarean delivery.23 They studied 30 women who had a scheduled cesarean delivery and who received a 500-mg intravenous dose of azithromycin that was initiated 15, 30, or 60 minutes before the surgical incision and then infused over 1 hour. They obtained maternal plasma samples multiple times during the first 8 hours after surgery. They also obtained samples of amniotic fluid, placenta, myometrium, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood intraoperatively. The median concentration of azithromycin in adipose tissue was 102 ng/g, which is below the MIC50 for Ureaplasma species (250 ng/mL). The median concentration in myometrial tissue was 402 ng/g. The concentration in maternal plasma consistently exceeded the MIC50 for Ureaplasma species.

What the evidence says

All women, regardless of weight,

CASE Resolved

For the 26-year-old obese laboring patient about to undergo cesarean delivery, reasonable steps for prevention of infection include removing the hair at the incision site with clippers or depilatory cream immediately prior to the start of surgery; cleansing the abdomen with a chlorhexidine-alcohol solution; and administering cefazolin (2 g) plus azithromycin (500 mg) preoperatively.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Cesarean delivery is now the most commonly performed major operation in hospitals across the United States. Approximately 30% of the 4 million deliveries that occur each year are by cesarean. Endometritis and wound infection (superficial and deep surgical site infection) are the most common postoperative complications of cesarean delivery. These 2 infections usually can be treated in a straightforward manner with antibiotics or surgical drainage. In some cases, however, they can lead to serious sequelae, such as pelvic abscess, septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis, and wound dehiscence/evisceration, thereby prolonging the patient’s hospitalization and significantly increasing medical expenses.

Accordingly, in the past 50 years many investigators have proposed various specific measures to reduce the risk of postcesarean infection. In this article, we critically evaluate 2 of these major interventions: methods of skin preparation and administration of prophylactic antibiotics. In part 2 of this series next month, we will review the evidence regarding preoperative bathing with an antiseptic, preoperative vaginal cleansing with an antiseptic solution, methods of placental extraction, closure of the deep subcutaneous layer of the abdomen, and closure of the skin.

CASE Cesarean delivery required for nonprogressing labor

A 26-year-old obese primigravid woman, body mass index (BMI) 37 kg m2, at 40 weeks’ gestation has been in labor for 20 hours. Her membranes have been ruptured for 16 hours. Her cervix is completely effaced and is 7 cm dilated. The fetal head is at −1 cm station. Her cervical examination findings have not changed in 4 hours despite adequate uterine contractility documented by intrauterine pressure catheter. You are now ready to proceed with cesarean delivery, and you want to do everything possible to prevent the patient from developing a postoperative infection.

What are the best practices for postcesarean infection prevention in this patient?

Skin preparation

Adequate preoperative skin preparation is an important first step in preventing post‑ cesarean infection.

How should you prepare the patient’s skin for surgery?

Two issues to address when preparing the abdominal wall for surgery are hair removal and skin cleansing. More than 40 years ago, Cruse and Foord definitively answered the question about hair removal.1 In a landmark cohort investigation of more than 23,000 patients having many different types of operative procedures, they demonstrated that shaving the hair on the evening before surgery resulted in a higher rate of wound infection than clipping the hair, removing the hair with a depilatory cream just before surgery, or not removing the hair at all.

Three recent investigations have thoughtfully addressed the issue of skin cleansing. Darouiche and colleagues conducted a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial comparing chlorhexidine-alcohol with povidone-iodine for skin preparation before surgery.2 Their investigation included 849 patients having many different types of surgical procedures, only a minority of which were in obstetric and gynecologic patients. They demonstrated fewer superficial wound infections in patients in the chlorhexidine-alcohol group (4.2% vs 8.6%, P = .008). Of even greater importance, patients in the chlorhexidine-alcohol group had fewer deep wound infections (1% vs 3%, P = .005).

Ngai and co-workers recently reported the results of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in which women undergoing nonurgent cesarean delivery had their skin cleansed with povidone-iodine with alcohol, chlorhexidine with alcohol, or the sequential combination of both solutions.3 The overall rate of surgical site infection was just 4.3%. The 3 groups had comparable infection rates and, accordingly, the authors were unable to conclude that one type of skin preparation was superior to the other.

The most informative recent investigation was by Tuuli and colleagues, who evaluated 1,147 patients having cesarean delivery assigned to undergo skin preparation with either chlorhexidine-alcohol or iodine-alcohol.4 Unlike the study by Ngai and co-workers, in this study approximately 40% of the patients in each treatment arm had unscheduled, urgent cesarean deliveries.3,4 Overall, the rate of infection in the chlorhexidine-alcohol group was 4.0% compared with 7.3% in the iodine-alcohol group (relative risk [RR], 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34–0.90, P = .02).

What the evidence says

Based on the evidence cited above, we advise removing hair at the incision site with clippers or depilatory cream just before the start of surgery. The abdomen should then be cleansed with a chlorhexidine-alcohol solution (Level I Evidence, Level 1A Recommendation; TABLE).

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Questions to consider regarding antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean delivery include appropriateness of treatment, antibiotic(s) selection, timing of administration, dose, and special circumstances.

Should you give the patient prophylactic antibiotics?

Prophylactic antibiotics are justified for surgical procedures whenever 3 major criteria are met5:

- the surgical site is inevitably contaminated with bacteria

- in the absence of prophylaxis, the frequency of infection at the operative site is unacceptably high

- operative site infections have the potential to lead to serious, potentially life-threatening sequelae.

Without a doubt, all 3 of these criteria are fulfilled when considering either urgent or nonurgent cesarean delivery. When cesarean delivery follows a long labor complicated by ruptured membranes, multiple internal vaginal examinations, and internal fetal monitoring, the operative site is inevitably contaminated with hundreds of thousands of pathogenic bacteria. Even when cesarean delivery is scheduled to occur before the onset of labor and ruptured membranes, a high concentration of vaginal organisms is introduced into the uterine and pelvic cavities coincident with making the hysterotomy incision.6

In the era before prophylactic antibiotics were used routinely, postoperative infection rates in some highly indigent patient populations approached 85%.5 Finally, as noted previously, postcesarean endometritis may progress to pelvic abscess formation, septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis, and septic shock; wound infections may be complicated by dehiscence and evisceration.

When should you administer antibiotics: Before the surgical incision or after cord clamping?

More than 50 years ago, Burke conducted the classic sequence of basic science experiments that forms the foundation for use of prophylactic antibiotics.7 Using a guinea pig model, he showed that prophylactic antibiotics exert their most pronounced effect when they are administered before the surgical incision is made and before bacterial contamination occurs. Prophylaxis that is delayed more than 4 hours after the start of surgery will likely be ineffective.

Interestingly, however, when clinicians first began using prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean delivery, some investigators expressed concern about the possible exposure of the neonate to antibiotics just before delivery—specifically, whether this exposure would increase the frequency of evaluations for suspected sepsis or would promote resistance among organisms that would make neonatal sepsis more difficult to treat.

Gordon and colleagues published an important report in 1979 that showed that preoperative administration of ampicillin did not increase the frequency of immediate or delayed neonatal infections.8 However, delaying the administration of ampicillin until after the umbilical cord was clamped was just as effective in preventing post‑cesarean endometritis. Subsequently, Cunningham and co-workers showed that preoperative administration of prophylactic antibiotics significantly increased the frequency of sepsis workups in exposed neonates compared with infants with no preoperative antibiotic exposure (28% vs 15%; P<.025).9 Based on these 2 reports, obstetricians adopted a policy of delaying antibiotic administration until after the infant’s umbilical cord was clamped.

In 2007, Sullivan and colleagues challenged this long-standing practice.10 In a carefully designed prospective, randomized, double-blind trial, they showed that patients who received preoperative cefazolin had a significant reduction in the frequency of endometritis compared with women who received the same antibiotic after cord clamping (1% vs 5%; RR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.2–0.94). The rate of wound infection was lower in the preoperative antibiotic group (3% vs 5%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance. The total infection-related morbidity was significantly reduced in women who received antibiotics preoperatively (4.0% vs 11.5%; RR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.18–0.87). Additionally, there was no increase in the frequency of proven or suspected neonatal infection in the infants exposed to antibiotics before delivery.

Subsequent to the publication by Sullivan and colleagues, other reports have confirmed that administration of antibiotics prior to surgery is superior to administration after clamping of the umbilical cord.10–12 Thus, we have come full circle back to Burke’s principle established more than a half century ago.7

Which antibiotic(s) should you administer for prophylaxis, and how many doses?

In an earlier review, one of us (PD) examined the evidence regarding choice of antibiotics and number of doses, concluding that a single dose of a first-generation cephalosporin, such as cefazolin, was the preferred regimen.5 The single dose was comparable in effectiveness to 2- or 3-dose regimens and to single- or multiple-dose regimens of broader-spectrum agents. For more than 20 years now, the standard of care for antibiotic prophylaxis has been a single 1- to 2-g dose of cefazolin.

Several recent reports, however, have raised the question of whether the prophylactic effect could be enhanced if the spectrum of activity of the antibiotic regimen was broadened to include an agent effective against Ureaplasma species.

Tita and colleagues evaluated an indigent patient population with an inherently high rate of postoperative infection; they showed that adding azithromycin 500 mg to cefazolin significantly reduced the rate of postcesarean endometritis.13 In a follow-up report from the same institution, Tita and co-workers demonstrated that adding azithromycin also significantly reduced the frequency of wound infection.14 In both of these investigations, the antibiotics were administered after cord clamping.

In a subsequent report, Ward and Duff15 showed that the combination of azithromycin plus cefazolin administered preoperatively resulted in a very low rate of both endometritis and wound infection in a population similar to that studied by Tita et al.13,14

Very recently, Tita and associates published the results of the Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis (C/SOAP) trial conducted at 14 US hospitals.16 This study included 2,013 women undergoing cesarean delivery during labor or after membrane rupture who were randomly assigned to receive intravenous azithromycin 500 mg (n = 1,019) or placebo (n = 994). All women also received standard antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin. The primary outcome (a composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infection within 6 weeks) was significantly lower in the azithromycin group than in the placebo group (6.1% vs 12.0%, P<.001). In addition, there were significant differences between the treatment groups in the rates of endometritis (3.8% in the azithromycin group vs 6.1% in the placebo group, P = .02) as well as in the rates of wound infection (2.4% vs 6.6%, respectively, P<.001). Of additional note, there were no differences between the 2 groups in the composite neonatal outcome of death and serious neonatal complications (14.3% vs 13.6%, P = .63).The investigators concluded that extended-spectrum prophylaxis with adjunctive azithromycin safely reduces infection rates without raising the risk of neonatal adverse outcomes.

What the evidence says

We conclude that all patients, even those having a scheduled cesarean before the onset of labor or ruptured membranes, should receive prophylactic antibiotics in a single dose administered preoperatively rather than after cord clamping (Level I Evidence, Level 1A Recommendation; TABLE). In high-risk populations (eg, women in labor with ruptured membranes who are having an urgent cesarean), for whom the baseline risk of infection is high, administer the combination of cefazolin plus azithromycin in lieu of cefazolin alone (Level I Evidence, Level 1A Recommendation; TABLE).

If the patient has a history of an immediate hypersensitivity reaction to beta-lactam antibiotics, we recommend the combination of clindamycin (900 mg) plus gentamicin (1.5 mg/kg) as a single infusion prior to surgery. We base this recommendation on the need to provide reasonable coverage against a broad range of pathogens. Clindamycin covers gram-positive aerobes, such as staphylococci species and group B streptococci, and anaerobes; gentamicin covers aerobic gram-negative bacilli. A single agent, such as clindamycin or metronidazole, does not provide the broad-based coverage necessary for effective prophylaxis (Level III Evidence, Level 1C Recommendation; TABLE).

If the patient is overweight or obese, should you modify the antibiotic dose?

The prevalence of obesity in the United States continues to increase. One-third of all US reproductive-aged women are obese, and 6% of women are extremely obese.17 Obesity increases the risk of postcesarean infection 3- to 5- fold.18 Because both pregnancy and obesity increase the total volume of a drug’s distribution, achieving adequate antibiotic tissue concentrations may be hindered by a dilutional effect. Furthermore, pharmacokinetic studies consistently have shown that the tissue concentration of an antibiotic—which, ideally, should be above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for common bacteria—determines the susceptibility of those tissues to infection, regardless of whether the serum concentration of the antibiotic is in the therapeutic range.19

These concerns have led to several recent investigations evaluating different doses of cefazolin for obese patients. Pevzner and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study of 29 women having a scheduled cesarean delivery.20 The patients were divided into 3 groups: lean (BMI <30 kg m2), obese (BMI 30.0–39.9 kg m2), and extremely obese (BMI >40 kg m2). All women received a 2-g dose of cefazolin 30 to 60 minutes before surgery. Cefazolin concentrations in adipose tissue obtained at the time of skin incision were inversely proportional to maternal BMI (r, −0.67; P<.001). All specimens demonstrated a therapeutic concentration (>1 µg/g) of cefazolin for gram-positive cocci, but 20% of the obese women and 33% of the extremely obese women did not achieve the MIC (>4 µg/g) for gram-negative bacilli (P = .29 and P = .14, respectively). At the time of skin closure, 20% of obese women and 44% of extremely obese women did not have tissue concentrations that exceeded the MIC for gram-negative bacteria.

Swank and associates conducted a prospective cohort study that included 28 women.18 They demonstrated that, after a 2-g dose of cefazolin, only 20% of the obese women (BMI 30–40 kg m2) and 0% of the extremely obese women (BMI >40 kg m2) achieved an adipose tissue concentration that exceeded the MIC for gram-negative rods (8 µg/mL). However, 100% and 71.4%, respectively, achieved such a tissue concentration after a 3-g dose. When the women were stratified by actual weight, there was a statistically significant difference between those who weighed less than 120 kg and those who weighed more than 120 kg. Seventy-nine percent of the former had a tissue concentration of cefazolin greater than 8 µg/mL compared with 0% of the women who weighed more than 120 kg. Based on these observations, the authors recommended a 3-g dose of cefazolin for women who weigh more than 120 kg.

In a double-blind RCT with 26 obese women (BMI ≥30 kg m2), Young and colleagues demonstrated that, at the time of hysterotomy and fascial closure, significantly higher concentrations of cefazolin were found in the adipose tissue of obese women who received a 3-g dose of antibiotic compared with those who received a 2-g dose.21 However, all concentrations of cefazolin were consistently above the MIC of cefazolin for gram-positive cocci (1 µg/g) and gram-negative bacilli (4 µg/g). Further, Maggio and co-workers conducted a double-blind RCT comparing a 2-g dose of cefazolin versus a 3-g dose in 57 obese women (BMI ≥30 kg m2).22 They found no statistically significant difference in the percentage of women who had tissue concentrations of cefazolin greater than the MIC for gram-positive cocci (8 µg/g). All samples were above the MIC of cefazolin for gram-negative bacilli (2 µg/g). Based on these data, these investigators did not recommend increasing the dose of cefazolin from 2 g to 3 g in obese patients.21,22

The studies discussed above are difficult to compare for 3 reasons. First, each study used a different MIC of cefazolin for both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Second, the authors sampled different maternal tissues or serum at varying times during the cesarean delivery. Third, the studies did not specifically investigate, or were not powered sufficiently to address, the more important clinical outcome of surgical site infection. In a recent historical cohort study, Ward and Duff were unable to show that increasing the dose of cefazolin to 2 g in all women with a BMI <30 kg m2 and to 3 g in all women with a BMI >30 kg m2 reduced the rate of endometritis and wound infection below the level already achieved with combined prophylaxis with cefazolin (1 g) plus azithromycin (500 mg).15

Sutton and colleagues recently assessed the pharmacokinetics of azithromycin when used as prophylaxis for cesarean delivery.23 They studied 30 women who had a scheduled cesarean delivery and who received a 500-mg intravenous dose of azithromycin that was initiated 15, 30, or 60 minutes before the surgical incision and then infused over 1 hour. They obtained maternal plasma samples multiple times during the first 8 hours after surgery. They also obtained samples of amniotic fluid, placenta, myometrium, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood intraoperatively. The median concentration of azithromycin in adipose tissue was 102 ng/g, which is below the MIC50 for Ureaplasma species (250 ng/mL). The median concentration in myometrial tissue was 402 ng/g. The concentration in maternal plasma consistently exceeded the MIC50 for Ureaplasma species.

What the evidence says

All women, regardless of weight,

CASE Resolved

For the 26-year-old obese laboring patient about to undergo cesarean delivery, reasonable steps for prevention of infection include removing the hair at the incision site with clippers or depilatory cream immediately prior to the start of surgery; cleansing the abdomen with a chlorhexidine-alcohol solution; and administering cefazolin (2 g) plus azithromycin (500 mg) preoperatively.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Cruse PJ, Foord R. A five‑year prospective study of 23,649 surgical wounds. Arch Surg. 1973;107(2):206–210.

- Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, et al. Chlorhexidine‑alcohol versus povidone‑iodine for surgical‑site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):18–26.

- Ngai IM, Van Arsdale A, Govindappagari S, et al. Skin preparation for prevention of surgical site infection after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(6):1251–1257.

- Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing skin antiseptic agents at cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):647–655.

- Duff P. Prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a simple cost‑effective strategy for prevention of postoperative morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157(4 pt 1):794–798.

- Dinsmoor MJ, Gilbert S, Landon MB, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal‑Fetal Medicine Units Network. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis for nonlaboring cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(4):752–756.

- Burke JF. The effective period of preventive antibiotic action in experimental incisions and dermal lesions. Surgery. 1961;50:161–168.

- Gordon HR, Phelps D, Blanchard K. Prophylactic cesarean section antibiotics: maternal and neonatal morbidity before or after cord clamping. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(2):151–156.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, DePalma RT, Roark M, Rosenfeld CR. Perioperative antimicrobials for cesarean delivery: before or after cord clamping? Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62(2):151–154.

- Sullivan SA, Smith T, Chang E, Hulsey T, Vandorsten JP, Soper D. Administration of cefazolin prior to skin incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in preventing postcesarean infectious morbidity: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(5):455.e1–e5.

- Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghulmiyah L, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):301.e1–e6.

- Owens SM, Brozanski BS, Meyn LA, Wiesenfeld HC. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for cesarean delivery before skin incision. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):573–579.

- Tita AT, Hauth JC, Grimes A, Owen J, Stamm AM, Andrews WW. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended‑spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):51–56.

- Tita AT, Owen J, Stamm AM, Grimes A, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Impact of extended‑spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis on incidence of postcesarean surgical wound infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):303.e1–e3.

- Ward E, Duff P. A comparison of 3 antibiotic regimens for prevention of postcesarean endometritis: an historical cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):751.e1–e4.

- Tita AT, Szychowski JM, Boggess K, et al; C/SOAP Trial Consortium. Adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(13):1231–1241.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegel KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006:295(13):1549–1555.

- Swank ML, Wing DA, Nicolau DP, McNulty JA. Increased 3‑gram cefazolin dosing for cesarean delivery prophylaxis in obese women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(3):415.e1–e8.

- Liu P, Derendorf H. Antimicrobial tissue concentrations. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003:17(3):599–613.

- Pevzner L, Swank M, Krepel C, Wing DA, Chan K, Edmiston CE Jr. Effects of maternal obesity on tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):877–882.

- Young OM, Shaik IH, Twedt R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of cefazolin prophylaxis in obese gravidae at time of cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):541.e1–e7.

- Maggio L, Nicolau DP, DaCosta M, Rouse DJ, Hughes BL. Cefazolin prophylaxis in obese women undergoing cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1205–1210.

- Sutton AL, Acosta EP, Larson KB, Kerstner‑Wood CD, Tita AT, Biggio JR. Perinatal pharmacokinetics of azithromycin for cesarean prophylaxis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):812. e1–e6.

- Cruse PJ, Foord R. A five‑year prospective study of 23,649 surgical wounds. Arch Surg. 1973;107(2):206–210.

- Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, et al. Chlorhexidine‑alcohol versus povidone‑iodine for surgical‑site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):18–26.

- Ngai IM, Van Arsdale A, Govindappagari S, et al. Skin preparation for prevention of surgical site infection after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(6):1251–1257.

- Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing skin antiseptic agents at cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):647–655.

- Duff P. Prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a simple cost‑effective strategy for prevention of postoperative morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157(4 pt 1):794–798.

- Dinsmoor MJ, Gilbert S, Landon MB, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal‑Fetal Medicine Units Network. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis for nonlaboring cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(4):752–756.

- Burke JF. The effective period of preventive antibiotic action in experimental incisions and dermal lesions. Surgery. 1961;50:161–168.

- Gordon HR, Phelps D, Blanchard K. Prophylactic cesarean section antibiotics: maternal and neonatal morbidity before or after cord clamping. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(2):151–156.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, DePalma RT, Roark M, Rosenfeld CR. Perioperative antimicrobials for cesarean delivery: before or after cord clamping? Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62(2):151–154.

- Sullivan SA, Smith T, Chang E, Hulsey T, Vandorsten JP, Soper D. Administration of cefazolin prior to skin incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in preventing postcesarean infectious morbidity: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(5):455.e1–e5.

- Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghulmiyah L, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):301.e1–e6.

- Owens SM, Brozanski BS, Meyn LA, Wiesenfeld HC. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for cesarean delivery before skin incision. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):573–579.

- Tita AT, Hauth JC, Grimes A, Owen J, Stamm AM, Andrews WW. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended‑spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):51–56.

- Tita AT, Owen J, Stamm AM, Grimes A, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Impact of extended‑spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis on incidence of postcesarean surgical wound infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):303.e1–e3.

- Ward E, Duff P. A comparison of 3 antibiotic regimens for prevention of postcesarean endometritis: an historical cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):751.e1–e4.

- Tita AT, Szychowski JM, Boggess K, et al; C/SOAP Trial Consortium. Adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(13):1231–1241.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegel KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006:295(13):1549–1555.

- Swank ML, Wing DA, Nicolau DP, McNulty JA. Increased 3‑gram cefazolin dosing for cesarean delivery prophylaxis in obese women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(3):415.e1–e8.

- Liu P, Derendorf H. Antimicrobial tissue concentrations. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003:17(3):599–613.

- Pevzner L, Swank M, Krepel C, Wing DA, Chan K, Edmiston CE Jr. Effects of maternal obesity on tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):877–882.

- Young OM, Shaik IH, Twedt R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of cefazolin prophylaxis in obese gravidae at time of cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):541.e1–e7.

- Maggio L, Nicolau DP, DaCosta M, Rouse DJ, Hughes BL. Cefazolin prophylaxis in obese women undergoing cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1205–1210.

- Sutton AL, Acosta EP, Larson KB, Kerstner‑Wood CD, Tita AT, Biggio JR. Perinatal pharmacokinetics of azithromycin for cesarean prophylaxis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):812. e1–e6.

In this Article

- Prepping the skin for surgery

- Selecting the antibiotic(s) for infection prevention

- Prophylaxis for the obese patient

Tips for sleep hygiene: A handout for patients

Are you in search of materials that can reinforce what you’ve told patients about how to get a good night’s sleep? Then download this handout, which includes 8 tips that cover the wake-promoting agents to avoid, the proper environment in which to go to sleep, and the dos and don’ts of before-bedtime activities. It also discusses when patients should seek professional help for a possible sleep disorder. This PDF from Neurology Reviews is available at: http://www.mdedge.com/neurologyreviews/article/115138/sleep-medicine/tips-sleep-hygiene/pdf.

Are you in search of materials that can reinforce what you’ve told patients about how to get a good night’s sleep? Then download this handout, which includes 8 tips that cover the wake-promoting agents to avoid, the proper environment in which to go to sleep, and the dos and don’ts of before-bedtime activities. It also discusses when patients should seek professional help for a possible sleep disorder. This PDF from Neurology Reviews is available at: http://www.mdedge.com/neurologyreviews/article/115138/sleep-medicine/tips-sleep-hygiene/pdf.

Are you in search of materials that can reinforce what you’ve told patients about how to get a good night’s sleep? Then download this handout, which includes 8 tips that cover the wake-promoting agents to avoid, the proper environment in which to go to sleep, and the dos and don’ts of before-bedtime activities. It also discusses when patients should seek professional help for a possible sleep disorder. This PDF from Neurology Reviews is available at: http://www.mdedge.com/neurologyreviews/article/115138/sleep-medicine/tips-sleep-hygiene/pdf.

Direct-acting antivirals: One of several keys to HCV eradication by 2030

Can the public health threat posed by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) be eliminated by 2030? Researchers in Italy say it can be done. Important elements of success will include the use of oral direct-acting antivirals and a global commitment to prevention. Earlier this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced plans to wipe out HCV worldwide by 2030 using the time between now and 2021 to reduce the number of annual new infections by 70%, and to slash the fatality rate by 60%. Find out what success in meeting the WHO challenge will hinge on by going to Family Practice News: http://www.mdedge.com/familypracticenews/article/114780/gastroenterology/direct-acting-antivirals-one-several-keys-hcv.

Can the public health threat posed by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) be eliminated by 2030? Researchers in Italy say it can be done. Important elements of success will include the use of oral direct-acting antivirals and a global commitment to prevention. Earlier this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced plans to wipe out HCV worldwide by 2030 using the time between now and 2021 to reduce the number of annual new infections by 70%, and to slash the fatality rate by 60%. Find out what success in meeting the WHO challenge will hinge on by going to Family Practice News: http://www.mdedge.com/familypracticenews/article/114780/gastroenterology/direct-acting-antivirals-one-several-keys-hcv.

Can the public health threat posed by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) be eliminated by 2030? Researchers in Italy say it can be done. Important elements of success will include the use of oral direct-acting antivirals and a global commitment to prevention. Earlier this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced plans to wipe out HCV worldwide by 2030 using the time between now and 2021 to reduce the number of annual new infections by 70%, and to slash the fatality rate by 60%. Find out what success in meeting the WHO challenge will hinge on by going to Family Practice News: http://www.mdedge.com/familypracticenews/article/114780/gastroenterology/direct-acting-antivirals-one-several-keys-hcv.

Palliative care boosts heart failure patient outcomes

Systematic introduction of palliative care interventions for patients with advanced heart failure improved patients’ quality of life and spurred their development of advanced-care preferences in a pair of independently performed, controlled pilot studies. But, despite demonstrating the ability of palliative-care interventions to help heart failure patients during their final months of life, the findings raised questions about the generalizability and reproducibility of palliative-care interventions that may depend upon the skills and experience of the individual specialists who deliver the care. To learn more about these 2 studies, go to Family Practice News: http://www.mdedge.com/familypracticenews/article/115737/cardiology/palliative-care-boosts-heart-failure-patient-outcomes.

Systematic introduction of palliative care interventions for patients with advanced heart failure improved patients’ quality of life and spurred their development of advanced-care preferences in a pair of independently performed, controlled pilot studies. But, despite demonstrating the ability of palliative-care interventions to help heart failure patients during their final months of life, the findings raised questions about the generalizability and reproducibility of palliative-care interventions that may depend upon the skills and experience of the individual specialists who deliver the care. To learn more about these 2 studies, go to Family Practice News: http://www.mdedge.com/familypracticenews/article/115737/cardiology/palliative-care-boosts-heart-failure-patient-outcomes.

Systematic introduction of palliative care interventions for patients with advanced heart failure improved patients’ quality of life and spurred their development of advanced-care preferences in a pair of independently performed, controlled pilot studies. But, despite demonstrating the ability of palliative-care interventions to help heart failure patients during their final months of life, the findings raised questions about the generalizability and reproducibility of palliative-care interventions that may depend upon the skills and experience of the individual specialists who deliver the care. To learn more about these 2 studies, go to Family Practice News: http://www.mdedge.com/familypracticenews/article/115737/cardiology/palliative-care-boosts-heart-failure-patient-outcomes.

Early menopause a risk factor for type 2 diabetes

Early age at menopause was associated with the incidence of type 2 diabetes, independent of obesity and a host of other potentially confounding factors, according to a prospect cohort study. “This association is independent of potential intermediate risk factors: obesity, insulin, glucose, inflammation, but also estradiol and other endogenous sex hormone levels,” said Taulant Muka, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at Erasmus Medical College, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Among the 3210 participants in the study, 319 incident cases were identified over the median 10.9-year follow-up period, with a relative risk for incident diabetes of 2.29 for women undergoing menopause before age 40, and 1.49 for those experiencing menopause between the ages of 40 and 44. Read more at Family Practice News: http://www.mdedge.com/familypracticenews/article/115648/diabetes/early-menopause-risk-factor-type-2-diabetes.