User login

Poison ivy: How effective are available treatments?

ABSTRACT

Purpose To determine the characteristics and clinical course of Rhus dermatitis in patients who seek assistance from primary care clinicians, as well as treatment approaches used by patients and recommended by clinicians, and treatment approaches associated with better outcomes.

Methods This was a prospective cohort study with standardized baseline data collection on patients and their rashes, followed by examination of patient-completed diaries of signs, symptoms, and treatments.

Results Thirty-six clinicians identified 186 interested patients, of which 89 completed and returned diaries and consent forms. Of those 89 patients, 92% reported pruritus; 91%, erythema; 87%, papules; and 49%, vesicles or bullae at baseline. Their rashes involved the head/face/neck, 61%; trunk, 56%; legs, 54%; and arms, 22%.

From the date of clinical consultation, the mean (standard deviation [SD]; range) duration of any symptom or sign was 14.4 days (8.0; 1-43). Patients most often had tried a topical antipruritic, astringent, or low-potency corticosteroid before seeking care. Clinicians prescribed oral or parenteral corticosteroids 81% of the time, sometimes in combination with a high-potency topical c

Conclusions Patients who visit a primary care clinician for Rhus dermatitis can expect the rash to last another 2 weeks on average (total duration: one day to 6 weeks) regardless of what treatment is prescribed. Parenteral corticosteroids plus high-potency topical corticosteroids may reduce the duration of the itching.

Rhus dermatitis (poison ivy, oak, and sumac) is a common cause of contact dermatitis throughout the United States. The condition is usually mild and often not brought to the attention of primary care clinicians. Some patients, however, do see a health care provider for treatment, most often because of pruritus. This form of contact dermatitis results from a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to urushiol, a colorless oil in the leaves, stem, root, and fruit of poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. The reaction, which occurs 24 to 72 hours following contact with the skin, can be prevented by washing the skin promptly with a detergent soap after exposure. By the age of 8, most people are sensitized to urushiol.1

According to most standard texts and clinical reviews, untreated Rhus dermatitis usually resolves in one to 3 weeks. What is not known is whether particular patient or rash characteristics might affect prognosis and thereby influence treatment recommendations—eg, age, gender, race, location of the rash, prior episodes, chronic illnesses such as diabetes, or chronic use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids.

Impetus for our study. An informal survey of 10 clinician members of the Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN), a statewide practice-based research network, suggested that primary care clinicians treat between one and 10 patients with poison ivy each week during the spring, summer, and fall (median 2.5). Their reported armamentarium included more than 15 different over-the-counter topical agents, several oral antihistamines, and a variety of topical, oral, and parenteral corticosteroids.

Surprisingly, there is very little published evidence on which to base treatment decisions. Using PubMed and the search terms, Rhus dermatitis, poison ivy, and poison oak, we found only 3 placebo-controlled clinical trials of Rhus dermatitis treatments in the English language literature after 1966. Based on these studies, Zanfel, a mixture of alcohol-soluble and anionic surfactant, may be somewhat effective, but pimecrolimus and jewelweed extract were no more effective than placebo.2-4 There is some evidence that topical corticosteroids are effective only before vesicles appear.5 In one uncontrolled study, intramuscular injection of betamethasone and dexamethasone yielded about a 30% reduction in symptoms within 48 hours.6 Assuming that systemic corticosteroids do produce benefit, however, the most effective dose and duration of treatment have not been determined.7,8

To address some of these gaps in our knowledge base, OKPRN members asked that we undertake a longitudinal cohort study of patients reporting to primary care practices.

METHODS

We conducted this study between May 2010 and October 2014. The project was approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board. Clinician members of OKPRN were invited to participate in the study via listserv, fax, or letter. We instructed clinicians and office staff to ask patients with Rhus dermatitis if they might be interested in participating in a study, which would require that they keep a symptom diary and would earn them a $20 gift card. Interested patients were given a packet of information, and a member of the research team later called the patients with additional information, including an explanation of informed consent and instructions on completing and returning the diary and written consent form.

Clinicians recorded information about the patient and the rash on a customized template, releasing it to the team after written consent was obtained from the patient. Categories for characterizing the rash were head/face, arms/hands, trunk, and legs/feet. A subset of 5 participating clinicians, selected to include a variety of practice types and patient populations, were also asked to produce, from their billing software, the number of patients and encounters in which poison ivy was addressed in each month of 2013.

On the diary, patients were instructed to record the presence or absence of pruritus, erythema, raised lesions, and vesicles/bullae at the end of each day until the rash resolved, or for 6 weeks following onset of the rash, whichever came first. Patients were asked to mail their diaries to the principal investigator once they were free of symptoms for one week or after 6 weeks from the onset of symptoms, whichever came first.

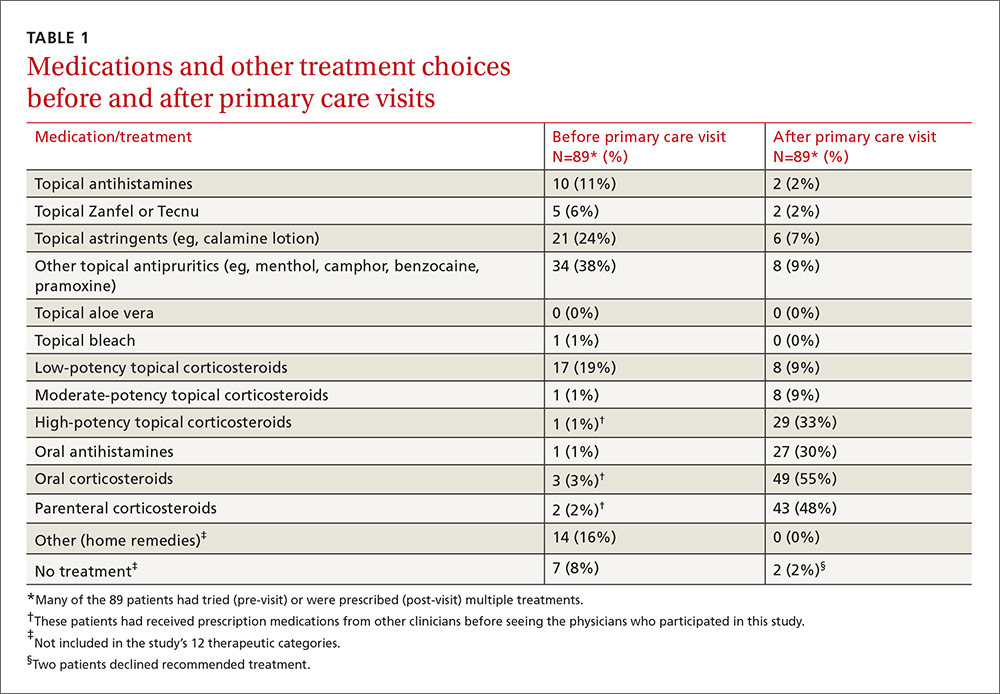

We asked both patients and clinicians to report medications used before and after the primary care encounter. A member of the research team assigned these medications to one of 12 categories: topical antihistamines, topical soaps (eg, Zanfel or Tecnu), topical astringents, other topical antipruritics, topical aloe vera, topical bleach, low-potency topical corticosteroids, moderate-potency topical corticosteroids, high-potency topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, oral corticosteroids, and parenteral corticosteroids.

We used independent T-tests to evaluate associations between baseline variables, patient-initiated treatments, and clinician-initiated treatments and the time to complete resolution of individual signs and symptoms and complete resolution of all signs and symptoms following the clinical encounter. We created additional outcome variables for initial resolution followed by recurrence of itching, erythema, papules, and vesicles. The purpose of these variables was to determine if some treatments were initially effective but without lasting effect.

We used the chi square test to assess associations between clinician-initiated treatments and recurrence of signs or symptoms following initial resolution. To account for chance associations resulting from multiple analyses, we chose to set the level of statistical significance at P=.01. However, because of the lower-than-projected sample size, we chose to also report variables with P<.05 so that the reader could judge the likelihood that a larger sample might have disclosed other important associations.

We assumed that an average of 4 categories of treatment would be tried (eg, topical corticosteroids, systemic corticosteroids, topical antihistamines, and other topical agents), and that the mean number of days until resolution would be 21, with a standard deviation (SD) of 4 days. Setting power at 80% and alpha at .05, we calculated it would take 105 patients per group (N=420) to detect a difference of 2 days in time until resolution.

RESULTS

Over the 5-year study period, 36 clinicians identified 186 patients who expressed an interest in the study, and they transmitted the patient contact information to the research team. Patients were seen in a traditional primary care setting. All 186 patients were enrolled by phone. However, only 89 completed and returned their diaries and signed consent forms; of these, 60% were female, 92% were white, 4% were black, 4% were American Indians, 2% were Hispanic, and 7% had diabetes mellitus.

Five practices contributed data on numbers of poison ivy encounters per month and total encounters per month for the year 2013. They included an inner city academic practice in central Oklahoma and a rural community health center, a suburban private practice, and 2 private practices in a town of 30,000 in eastern Oklahoma. The largest average number of encounters occurred between April and August.

The distribution of enrolled-patient visits by month and season corresponded roughly to the proportions of all patient visits for poison ivy, with 1% occurring in the winter, 35% in the spring, 55% during the summer, and 9% in the fall. Virtually all study participants (92%) complained of pruritus and had erythema (91%) and papules (87%). Forty-nine percent had vesicles or bullae. The area of the body most often affected was the head/face/neck, 61%, followed by the trunk, 56%; legs, 54%; and arms, 22%.

From the date of initial clinical consultation, the mean/median (SD; range) duration of symptoms and signs were: pruritus, 10.9/9 days (7.1; 0-43); erythema, 13.7/13 days (7.7; 0-42); papules, 10.1/9.5 days (6.5; 0-37); and vesicles, 5.3/5 days (4.1; 0-15). The mean/median (SD; range) duration of any symptom or sign was 14.4/13.5 days (8; 1-43). Rashes with vesicles tended to last longer (16.1 vs 12.9 days), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

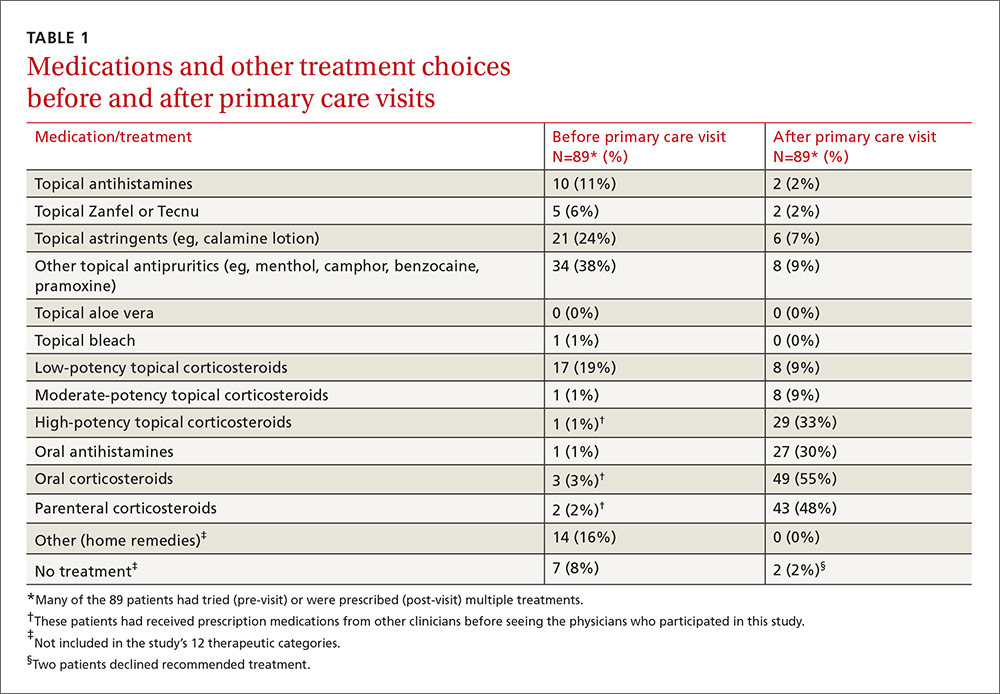

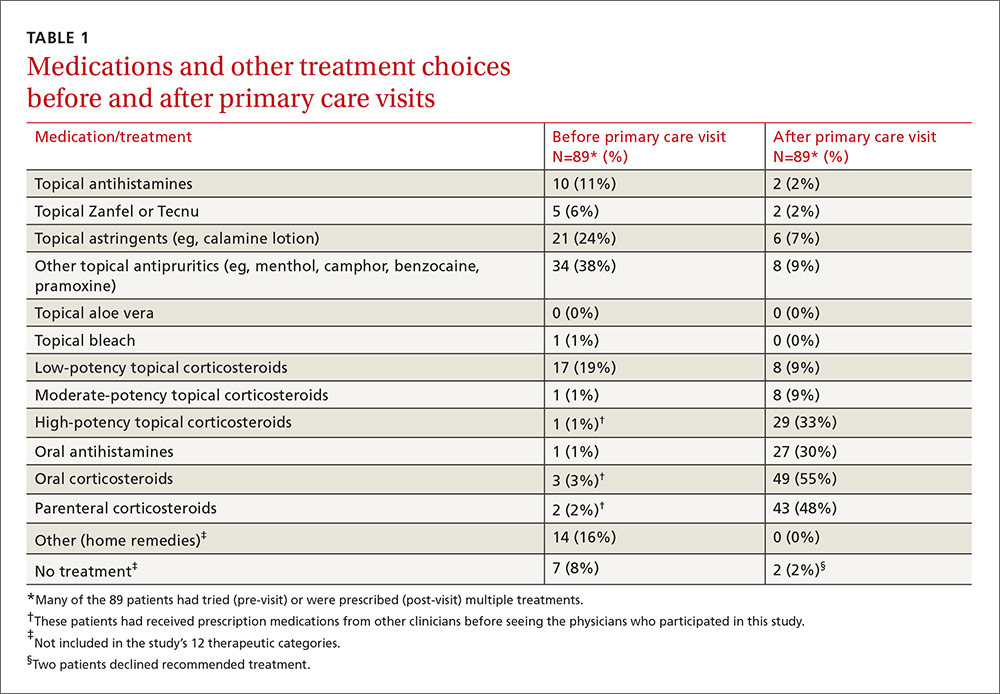

Treatments used by patients before and after their primary care visit are shown in TABLE 1. Seventy-three percent of patients had tried something from one treatment category before consulting a clinician, and 31% had tried something from more than one category. They were most likely to have used a topical antipruritic, astringent, or low-potency corticosteroid, or a combination of these. Clinicians always recommended some treatment and, in 76% of cases, treatments from more than one category. They most often prescribed oral or parenteral corticosteroids (81% of the time), sometimes in combination with a high-potency topical corticosteroid (25% of the time) or oral antihistamine (31%).

No statistically significant associations were found between the baseline non-treatment variables and duration of symptoms and signs. Patient-initiated treatments were also not associated with duration of symptoms and signs following the initial clinician visit.

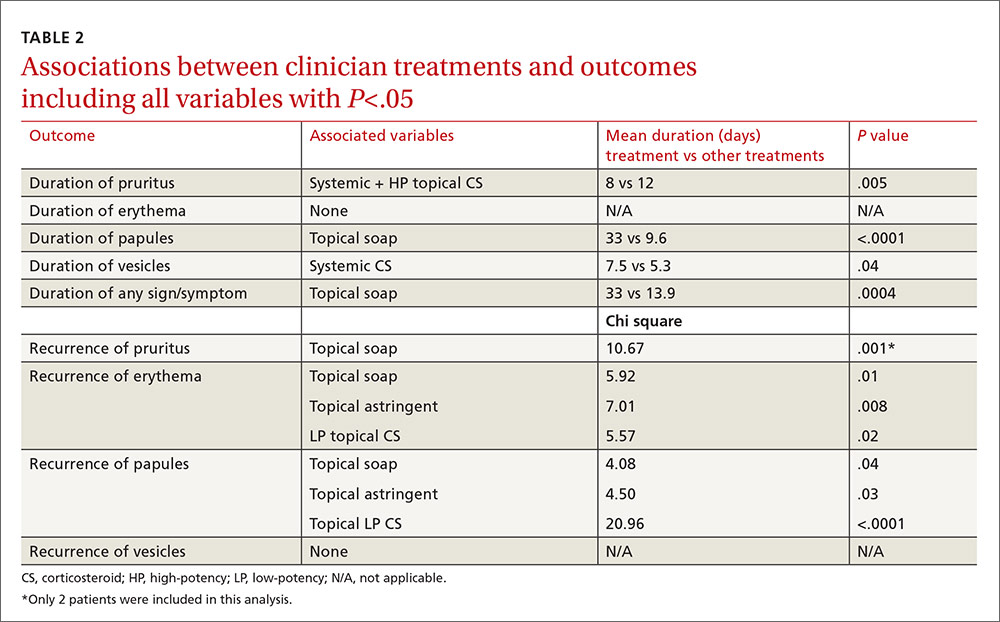

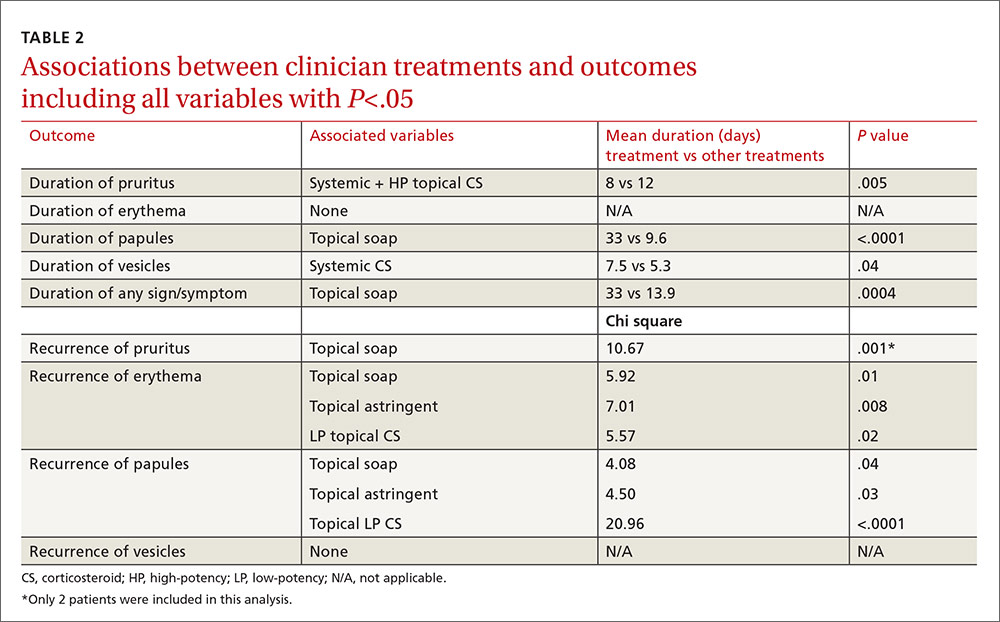

Of the treatments prescribed by clinicians or independently chosen by patients following their initial office visit, only systemic corticosteroids plus high-potency topical corticosteroids were associated with a significantly shorter duration of itching (P=.005). No treatment was associated with reduced duration of erythema, papules, or vesicles. Use of topical soaps was associated with a longer duration of papules (P<.0001) and of total duration of signs or symptoms (P=.0004) compared with other treatments.

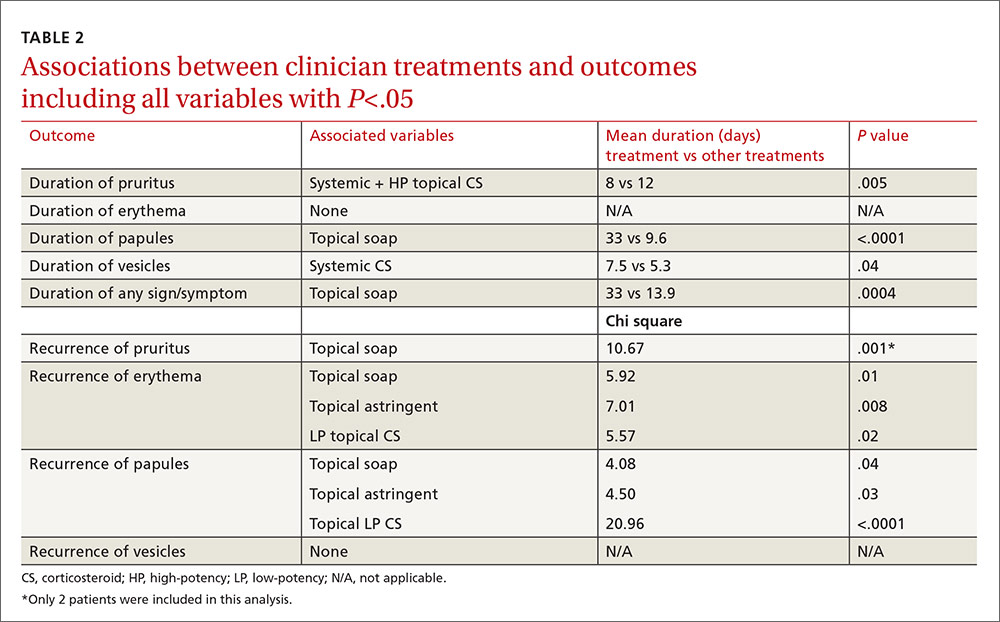

Location and characteristics of the rash were not associated with likelihood of recurrence following treatment. Post-visit use of a topical soap was associated with recurrence of itching (P=.001) and erythema (P=.01). Recurrence of erythema was also more frequent in patients prescribed topical astringents (beta coefficient=0.28; P=.008), and recurrence of papules was more common in patients treated with low-potency topical corticosteroids (P<.0001). These results and several others that almost reached statistical significance are shown in TABLE 2.

In the multivariable models, the only variable associated with duration of pruritus was the combination of systemic and high-potency topical corticosteroids (8 vs 12 days.) Use of only parenteral or only high-potency topical corticosteroids did not predict shorter duration of pruritus. Use of topical soaps was associated with longer duration of papules (33 vs 9.6 days) and longer duration of any symptoms (33 vs 13.9 days). It was also associated with a higher likelihood of recurrence of pruritus (chi square test [χ2], 10.67) and recurrence of erythema (χ2, 5.92) after initial resolution. Topical astringent use was predictive of recurrence of erythema (χ2, 7.01) and use of low-potency corticosteroids was associated with recurrence of papules (χ2, 20.96).

DISCUSSION

While network clinicians felt that studying poison ivy was of interest and importance, and we had preliminary survey information to suggest it was a common problem treated in primary care, our data suggest that clinical encounters for poison ivy are actually quite uncommon (less than 0.4% of all encounters) even during peak months. Our problems with recruitment were therefore unexpected, and we ended up with far fewer enrolled patients than we had projected, and needed, based on our power analysis. Also based on our preliminary survey, we anticipated considerably more variation in treatment approach than we found. Most clinicians recommended either an oral, parenteral, or high-potency topical corticosteroid, and some also recommended an oral antihistamine, usually diphenhydramine.

The literature and common sense suggest that most patients who seek medical treatment for poison ivy are primarily concerned about itching. Even with the smaller-than-anticipated number of participants in this study, we were able to show that the combination of a systemic (oral or parenteral) corticosteroid and a high-potency topical corticosteroid was associated with a statistically significant shorter duration of pruritus with no recurrence following treatment. We found no evidence that systemic corticosteroids alone, parenteral corticosteroids alone, or high-potency topical corticosteroids alone had any effect on duration of signs or symptoms, even at an alpha of .05. We also found no evidence that oral antihistamines were associated with a shorter duration of pruritus (P=.06); with a larger sample size, we might have found a difference.

Since only 2 patients used topical soaps following their initial clinician visit, the associations between use of these products and longer duration of signs and symptoms and with recurrence of signs and symptoms, although statistically significant, should be viewed with skepticism and with an eye toward possible confounders (eg, people who used these agents may have been more likely to notice and record minor symptoms). Furthermore, these agents have been effective only when used before or at the onset of the rash.

Study limitations. The study has a number of limitations. It had a high drop-out rate. Some patients might not have had poison ivy, but it is generally considered easy to diagnose with accuracy. We cannot be sure that all of the enrolled patients had Rhus dermatitis. Enrollment was based on the clinical impression of the patients’ primary care clinicians. The sample size reduced the power of the study to detect small differences in treatment effects and prevented more complex analyses (eg, combinations of medications, interactions).

The possibility of self-selection bias, weaknesses of the cohort design, and patient-reported outcome measures were additional limitations. The study was also carried out in a single southwestern state, which may not be representative of some other locations. However, it is one of only a few studies published on Rhus dermatitis and possibly the only one conducted in primary care settings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Cara Vaught, MPH, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, 900 NE 10th Street, Oklahoma City, OK 73104; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank the Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) and the OKPRN clinician members (as well as their staff and patients) for their contributions to this study. The authors also thank Bradley Long, Matthew Marr, and Kellie Hetherington for their involvement in the data collection for this study.

1. Epstein WL. Occupational poison ivy and oak dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:511-516.

2. Long D, Ballentine NH, Marks JG Jr. Treatment of poison ivy/oak allergic contact dermatitis with an extract of jewelweed. Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:150-153.

3. Amrol D, Keitel D, Hagaman D, et al. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of human allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:563-566.

4. Davila A, Laurora M, Fulton J, et al. A new topical agent, Zanfel, ameliorates urushiol-induced Toxicodendron allergic contact dermatitis [abstract 364]. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(suppl 4):S98.

5. Vernon HJ, Olsen EA. A controlled trial of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% in the treatment of experimentally induced Rhus dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:829-832.

6. Dickey RF. Parenteral short-term corticosteroid therapy in moderate to severe dermatoses. A comparative multiclinic study. Cutis. 1976;17:179-193.

7. Goodall J. Oral corticosteroids for poison ivy dermatitis. CMAJ. 2002;166:300-301.

8. Moe JF. How much steroid for poison ivy? Postgrad Med. 1999;106:21,24.

ABSTRACT

Purpose To determine the characteristics and clinical course of Rhus dermatitis in patients who seek assistance from primary care clinicians, as well as treatment approaches used by patients and recommended by clinicians, and treatment approaches associated with better outcomes.

Methods This was a prospective cohort study with standardized baseline data collection on patients and their rashes, followed by examination of patient-completed diaries of signs, symptoms, and treatments.

Results Thirty-six clinicians identified 186 interested patients, of which 89 completed and returned diaries and consent forms. Of those 89 patients, 92% reported pruritus; 91%, erythema; 87%, papules; and 49%, vesicles or bullae at baseline. Their rashes involved the head/face/neck, 61%; trunk, 56%; legs, 54%; and arms, 22%.

From the date of clinical consultation, the mean (standard deviation [SD]; range) duration of any symptom or sign was 14.4 days (8.0; 1-43). Patients most often had tried a topical antipruritic, astringent, or low-potency corticosteroid before seeking care. Clinicians prescribed oral or parenteral corticosteroids 81% of the time, sometimes in combination with a high-potency topical c

Conclusions Patients who visit a primary care clinician for Rhus dermatitis can expect the rash to last another 2 weeks on average (total duration: one day to 6 weeks) regardless of what treatment is prescribed. Parenteral corticosteroids plus high-potency topical corticosteroids may reduce the duration of the itching.

Rhus dermatitis (poison ivy, oak, and sumac) is a common cause of contact dermatitis throughout the United States. The condition is usually mild and often not brought to the attention of primary care clinicians. Some patients, however, do see a health care provider for treatment, most often because of pruritus. This form of contact dermatitis results from a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to urushiol, a colorless oil in the leaves, stem, root, and fruit of poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. The reaction, which occurs 24 to 72 hours following contact with the skin, can be prevented by washing the skin promptly with a detergent soap after exposure. By the age of 8, most people are sensitized to urushiol.1

According to most standard texts and clinical reviews, untreated Rhus dermatitis usually resolves in one to 3 weeks. What is not known is whether particular patient or rash characteristics might affect prognosis and thereby influence treatment recommendations—eg, age, gender, race, location of the rash, prior episodes, chronic illnesses such as diabetes, or chronic use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids.

Impetus for our study. An informal survey of 10 clinician members of the Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN), a statewide practice-based research network, suggested that primary care clinicians treat between one and 10 patients with poison ivy each week during the spring, summer, and fall (median 2.5). Their reported armamentarium included more than 15 different over-the-counter topical agents, several oral antihistamines, and a variety of topical, oral, and parenteral corticosteroids.

Surprisingly, there is very little published evidence on which to base treatment decisions. Using PubMed and the search terms, Rhus dermatitis, poison ivy, and poison oak, we found only 3 placebo-controlled clinical trials of Rhus dermatitis treatments in the English language literature after 1966. Based on these studies, Zanfel, a mixture of alcohol-soluble and anionic surfactant, may be somewhat effective, but pimecrolimus and jewelweed extract were no more effective than placebo.2-4 There is some evidence that topical corticosteroids are effective only before vesicles appear.5 In one uncontrolled study, intramuscular injection of betamethasone and dexamethasone yielded about a 30% reduction in symptoms within 48 hours.6 Assuming that systemic corticosteroids do produce benefit, however, the most effective dose and duration of treatment have not been determined.7,8

To address some of these gaps in our knowledge base, OKPRN members asked that we undertake a longitudinal cohort study of patients reporting to primary care practices.

METHODS

We conducted this study between May 2010 and October 2014. The project was approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board. Clinician members of OKPRN were invited to participate in the study via listserv, fax, or letter. We instructed clinicians and office staff to ask patients with Rhus dermatitis if they might be interested in participating in a study, which would require that they keep a symptom diary and would earn them a $20 gift card. Interested patients were given a packet of information, and a member of the research team later called the patients with additional information, including an explanation of informed consent and instructions on completing and returning the diary and written consent form.

Clinicians recorded information about the patient and the rash on a customized template, releasing it to the team after written consent was obtained from the patient. Categories for characterizing the rash were head/face, arms/hands, trunk, and legs/feet. A subset of 5 participating clinicians, selected to include a variety of practice types and patient populations, were also asked to produce, from their billing software, the number of patients and encounters in which poison ivy was addressed in each month of 2013.

On the diary, patients were instructed to record the presence or absence of pruritus, erythema, raised lesions, and vesicles/bullae at the end of each day until the rash resolved, or for 6 weeks following onset of the rash, whichever came first. Patients were asked to mail their diaries to the principal investigator once they were free of symptoms for one week or after 6 weeks from the onset of symptoms, whichever came first.

We asked both patients and clinicians to report medications used before and after the primary care encounter. A member of the research team assigned these medications to one of 12 categories: topical antihistamines, topical soaps (eg, Zanfel or Tecnu), topical astringents, other topical antipruritics, topical aloe vera, topical bleach, low-potency topical corticosteroids, moderate-potency topical corticosteroids, high-potency topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, oral corticosteroids, and parenteral corticosteroids.

We used independent T-tests to evaluate associations between baseline variables, patient-initiated treatments, and clinician-initiated treatments and the time to complete resolution of individual signs and symptoms and complete resolution of all signs and symptoms following the clinical encounter. We created additional outcome variables for initial resolution followed by recurrence of itching, erythema, papules, and vesicles. The purpose of these variables was to determine if some treatments were initially effective but without lasting effect.

We used the chi square test to assess associations between clinician-initiated treatments and recurrence of signs or symptoms following initial resolution. To account for chance associations resulting from multiple analyses, we chose to set the level of statistical significance at P=.01. However, because of the lower-than-projected sample size, we chose to also report variables with P<.05 so that the reader could judge the likelihood that a larger sample might have disclosed other important associations.

We assumed that an average of 4 categories of treatment would be tried (eg, topical corticosteroids, systemic corticosteroids, topical antihistamines, and other topical agents), and that the mean number of days until resolution would be 21, with a standard deviation (SD) of 4 days. Setting power at 80% and alpha at .05, we calculated it would take 105 patients per group (N=420) to detect a difference of 2 days in time until resolution.

RESULTS

Over the 5-year study period, 36 clinicians identified 186 patients who expressed an interest in the study, and they transmitted the patient contact information to the research team. Patients were seen in a traditional primary care setting. All 186 patients were enrolled by phone. However, only 89 completed and returned their diaries and signed consent forms; of these, 60% were female, 92% were white, 4% were black, 4% were American Indians, 2% were Hispanic, and 7% had diabetes mellitus.

Five practices contributed data on numbers of poison ivy encounters per month and total encounters per month for the year 2013. They included an inner city academic practice in central Oklahoma and a rural community health center, a suburban private practice, and 2 private practices in a town of 30,000 in eastern Oklahoma. The largest average number of encounters occurred between April and August.

The distribution of enrolled-patient visits by month and season corresponded roughly to the proportions of all patient visits for poison ivy, with 1% occurring in the winter, 35% in the spring, 55% during the summer, and 9% in the fall. Virtually all study participants (92%) complained of pruritus and had erythema (91%) and papules (87%). Forty-nine percent had vesicles or bullae. The area of the body most often affected was the head/face/neck, 61%, followed by the trunk, 56%; legs, 54%; and arms, 22%.

From the date of initial clinical consultation, the mean/median (SD; range) duration of symptoms and signs were: pruritus, 10.9/9 days (7.1; 0-43); erythema, 13.7/13 days (7.7; 0-42); papules, 10.1/9.5 days (6.5; 0-37); and vesicles, 5.3/5 days (4.1; 0-15). The mean/median (SD; range) duration of any symptom or sign was 14.4/13.5 days (8; 1-43). Rashes with vesicles tended to last longer (16.1 vs 12.9 days), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Treatments used by patients before and after their primary care visit are shown in TABLE 1. Seventy-three percent of patients had tried something from one treatment category before consulting a clinician, and 31% had tried something from more than one category. They were most likely to have used a topical antipruritic, astringent, or low-potency corticosteroid, or a combination of these. Clinicians always recommended some treatment and, in 76% of cases, treatments from more than one category. They most often prescribed oral or parenteral corticosteroids (81% of the time), sometimes in combination with a high-potency topical corticosteroid (25% of the time) or oral antihistamine (31%).

No statistically significant associations were found between the baseline non-treatment variables and duration of symptoms and signs. Patient-initiated treatments were also not associated with duration of symptoms and signs following the initial clinician visit.

Of the treatments prescribed by clinicians or independently chosen by patients following their initial office visit, only systemic corticosteroids plus high-potency topical corticosteroids were associated with a significantly shorter duration of itching (P=.005). No treatment was associated with reduced duration of erythema, papules, or vesicles. Use of topical soaps was associated with a longer duration of papules (P<.0001) and of total duration of signs or symptoms (P=.0004) compared with other treatments.

Location and characteristics of the rash were not associated with likelihood of recurrence following treatment. Post-visit use of a topical soap was associated with recurrence of itching (P=.001) and erythema (P=.01). Recurrence of erythema was also more frequent in patients prescribed topical astringents (beta coefficient=0.28; P=.008), and recurrence of papules was more common in patients treated with low-potency topical corticosteroids (P<.0001). These results and several others that almost reached statistical significance are shown in TABLE 2.

In the multivariable models, the only variable associated with duration of pruritus was the combination of systemic and high-potency topical corticosteroids (8 vs 12 days.) Use of only parenteral or only high-potency topical corticosteroids did not predict shorter duration of pruritus. Use of topical soaps was associated with longer duration of papules (33 vs 9.6 days) and longer duration of any symptoms (33 vs 13.9 days). It was also associated with a higher likelihood of recurrence of pruritus (chi square test [χ2], 10.67) and recurrence of erythema (χ2, 5.92) after initial resolution. Topical astringent use was predictive of recurrence of erythema (χ2, 7.01) and use of low-potency corticosteroids was associated with recurrence of papules (χ2, 20.96).

DISCUSSION

While network clinicians felt that studying poison ivy was of interest and importance, and we had preliminary survey information to suggest it was a common problem treated in primary care, our data suggest that clinical encounters for poison ivy are actually quite uncommon (less than 0.4% of all encounters) even during peak months. Our problems with recruitment were therefore unexpected, and we ended up with far fewer enrolled patients than we had projected, and needed, based on our power analysis. Also based on our preliminary survey, we anticipated considerably more variation in treatment approach than we found. Most clinicians recommended either an oral, parenteral, or high-potency topical corticosteroid, and some also recommended an oral antihistamine, usually diphenhydramine.

The literature and common sense suggest that most patients who seek medical treatment for poison ivy are primarily concerned about itching. Even with the smaller-than-anticipated number of participants in this study, we were able to show that the combination of a systemic (oral or parenteral) corticosteroid and a high-potency topical corticosteroid was associated with a statistically significant shorter duration of pruritus with no recurrence following treatment. We found no evidence that systemic corticosteroids alone, parenteral corticosteroids alone, or high-potency topical corticosteroids alone had any effect on duration of signs or symptoms, even at an alpha of .05. We also found no evidence that oral antihistamines were associated with a shorter duration of pruritus (P=.06); with a larger sample size, we might have found a difference.

Since only 2 patients used topical soaps following their initial clinician visit, the associations between use of these products and longer duration of signs and symptoms and with recurrence of signs and symptoms, although statistically significant, should be viewed with skepticism and with an eye toward possible confounders (eg, people who used these agents may have been more likely to notice and record minor symptoms). Furthermore, these agents have been effective only when used before or at the onset of the rash.

Study limitations. The study has a number of limitations. It had a high drop-out rate. Some patients might not have had poison ivy, but it is generally considered easy to diagnose with accuracy. We cannot be sure that all of the enrolled patients had Rhus dermatitis. Enrollment was based on the clinical impression of the patients’ primary care clinicians. The sample size reduced the power of the study to detect small differences in treatment effects and prevented more complex analyses (eg, combinations of medications, interactions).

The possibility of self-selection bias, weaknesses of the cohort design, and patient-reported outcome measures were additional limitations. The study was also carried out in a single southwestern state, which may not be representative of some other locations. However, it is one of only a few studies published on Rhus dermatitis and possibly the only one conducted in primary care settings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Cara Vaught, MPH, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, 900 NE 10th Street, Oklahoma City, OK 73104; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank the Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) and the OKPRN clinician members (as well as their staff and patients) for their contributions to this study. The authors also thank Bradley Long, Matthew Marr, and Kellie Hetherington for their involvement in the data collection for this study.

ABSTRACT

Purpose To determine the characteristics and clinical course of Rhus dermatitis in patients who seek assistance from primary care clinicians, as well as treatment approaches used by patients and recommended by clinicians, and treatment approaches associated with better outcomes.

Methods This was a prospective cohort study with standardized baseline data collection on patients and their rashes, followed by examination of patient-completed diaries of signs, symptoms, and treatments.

Results Thirty-six clinicians identified 186 interested patients, of which 89 completed and returned diaries and consent forms. Of those 89 patients, 92% reported pruritus; 91%, erythema; 87%, papules; and 49%, vesicles or bullae at baseline. Their rashes involved the head/face/neck, 61%; trunk, 56%; legs, 54%; and arms, 22%.

From the date of clinical consultation, the mean (standard deviation [SD]; range) duration of any symptom or sign was 14.4 days (8.0; 1-43). Patients most often had tried a topical antipruritic, astringent, or low-potency corticosteroid before seeking care. Clinicians prescribed oral or parenteral corticosteroids 81% of the time, sometimes in combination with a high-potency topical c

Conclusions Patients who visit a primary care clinician for Rhus dermatitis can expect the rash to last another 2 weeks on average (total duration: one day to 6 weeks) regardless of what treatment is prescribed. Parenteral corticosteroids plus high-potency topical corticosteroids may reduce the duration of the itching.

Rhus dermatitis (poison ivy, oak, and sumac) is a common cause of contact dermatitis throughout the United States. The condition is usually mild and often not brought to the attention of primary care clinicians. Some patients, however, do see a health care provider for treatment, most often because of pruritus. This form of contact dermatitis results from a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to urushiol, a colorless oil in the leaves, stem, root, and fruit of poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. The reaction, which occurs 24 to 72 hours following contact with the skin, can be prevented by washing the skin promptly with a detergent soap after exposure. By the age of 8, most people are sensitized to urushiol.1

According to most standard texts and clinical reviews, untreated Rhus dermatitis usually resolves in one to 3 weeks. What is not known is whether particular patient or rash characteristics might affect prognosis and thereby influence treatment recommendations—eg, age, gender, race, location of the rash, prior episodes, chronic illnesses such as diabetes, or chronic use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids.

Impetus for our study. An informal survey of 10 clinician members of the Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN), a statewide practice-based research network, suggested that primary care clinicians treat between one and 10 patients with poison ivy each week during the spring, summer, and fall (median 2.5). Their reported armamentarium included more than 15 different over-the-counter topical agents, several oral antihistamines, and a variety of topical, oral, and parenteral corticosteroids.

Surprisingly, there is very little published evidence on which to base treatment decisions. Using PubMed and the search terms, Rhus dermatitis, poison ivy, and poison oak, we found only 3 placebo-controlled clinical trials of Rhus dermatitis treatments in the English language literature after 1966. Based on these studies, Zanfel, a mixture of alcohol-soluble and anionic surfactant, may be somewhat effective, but pimecrolimus and jewelweed extract were no more effective than placebo.2-4 There is some evidence that topical corticosteroids are effective only before vesicles appear.5 In one uncontrolled study, intramuscular injection of betamethasone and dexamethasone yielded about a 30% reduction in symptoms within 48 hours.6 Assuming that systemic corticosteroids do produce benefit, however, the most effective dose and duration of treatment have not been determined.7,8

To address some of these gaps in our knowledge base, OKPRN members asked that we undertake a longitudinal cohort study of patients reporting to primary care practices.

METHODS

We conducted this study between May 2010 and October 2014. The project was approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board. Clinician members of OKPRN were invited to participate in the study via listserv, fax, or letter. We instructed clinicians and office staff to ask patients with Rhus dermatitis if they might be interested in participating in a study, which would require that they keep a symptom diary and would earn them a $20 gift card. Interested patients were given a packet of information, and a member of the research team later called the patients with additional information, including an explanation of informed consent and instructions on completing and returning the diary and written consent form.

Clinicians recorded information about the patient and the rash on a customized template, releasing it to the team after written consent was obtained from the patient. Categories for characterizing the rash were head/face, arms/hands, trunk, and legs/feet. A subset of 5 participating clinicians, selected to include a variety of practice types and patient populations, were also asked to produce, from their billing software, the number of patients and encounters in which poison ivy was addressed in each month of 2013.

On the diary, patients were instructed to record the presence or absence of pruritus, erythema, raised lesions, and vesicles/bullae at the end of each day until the rash resolved, or for 6 weeks following onset of the rash, whichever came first. Patients were asked to mail their diaries to the principal investigator once they were free of symptoms for one week or after 6 weeks from the onset of symptoms, whichever came first.

We asked both patients and clinicians to report medications used before and after the primary care encounter. A member of the research team assigned these medications to one of 12 categories: topical antihistamines, topical soaps (eg, Zanfel or Tecnu), topical astringents, other topical antipruritics, topical aloe vera, topical bleach, low-potency topical corticosteroids, moderate-potency topical corticosteroids, high-potency topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, oral corticosteroids, and parenteral corticosteroids.

We used independent T-tests to evaluate associations between baseline variables, patient-initiated treatments, and clinician-initiated treatments and the time to complete resolution of individual signs and symptoms and complete resolution of all signs and symptoms following the clinical encounter. We created additional outcome variables for initial resolution followed by recurrence of itching, erythema, papules, and vesicles. The purpose of these variables was to determine if some treatments were initially effective but without lasting effect.

We used the chi square test to assess associations between clinician-initiated treatments and recurrence of signs or symptoms following initial resolution. To account for chance associations resulting from multiple analyses, we chose to set the level of statistical significance at P=.01. However, because of the lower-than-projected sample size, we chose to also report variables with P<.05 so that the reader could judge the likelihood that a larger sample might have disclosed other important associations.

We assumed that an average of 4 categories of treatment would be tried (eg, topical corticosteroids, systemic corticosteroids, topical antihistamines, and other topical agents), and that the mean number of days until resolution would be 21, with a standard deviation (SD) of 4 days. Setting power at 80% and alpha at .05, we calculated it would take 105 patients per group (N=420) to detect a difference of 2 days in time until resolution.

RESULTS

Over the 5-year study period, 36 clinicians identified 186 patients who expressed an interest in the study, and they transmitted the patient contact information to the research team. Patients were seen in a traditional primary care setting. All 186 patients were enrolled by phone. However, only 89 completed and returned their diaries and signed consent forms; of these, 60% were female, 92% were white, 4% were black, 4% were American Indians, 2% were Hispanic, and 7% had diabetes mellitus.

Five practices contributed data on numbers of poison ivy encounters per month and total encounters per month for the year 2013. They included an inner city academic practice in central Oklahoma and a rural community health center, a suburban private practice, and 2 private practices in a town of 30,000 in eastern Oklahoma. The largest average number of encounters occurred between April and August.

The distribution of enrolled-patient visits by month and season corresponded roughly to the proportions of all patient visits for poison ivy, with 1% occurring in the winter, 35% in the spring, 55% during the summer, and 9% in the fall. Virtually all study participants (92%) complained of pruritus and had erythema (91%) and papules (87%). Forty-nine percent had vesicles or bullae. The area of the body most often affected was the head/face/neck, 61%, followed by the trunk, 56%; legs, 54%; and arms, 22%.

From the date of initial clinical consultation, the mean/median (SD; range) duration of symptoms and signs were: pruritus, 10.9/9 days (7.1; 0-43); erythema, 13.7/13 days (7.7; 0-42); papules, 10.1/9.5 days (6.5; 0-37); and vesicles, 5.3/5 days (4.1; 0-15). The mean/median (SD; range) duration of any symptom or sign was 14.4/13.5 days (8; 1-43). Rashes with vesicles tended to last longer (16.1 vs 12.9 days), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Treatments used by patients before and after their primary care visit are shown in TABLE 1. Seventy-three percent of patients had tried something from one treatment category before consulting a clinician, and 31% had tried something from more than one category. They were most likely to have used a topical antipruritic, astringent, or low-potency corticosteroid, or a combination of these. Clinicians always recommended some treatment and, in 76% of cases, treatments from more than one category. They most often prescribed oral or parenteral corticosteroids (81% of the time), sometimes in combination with a high-potency topical corticosteroid (25% of the time) or oral antihistamine (31%).

No statistically significant associations were found between the baseline non-treatment variables and duration of symptoms and signs. Patient-initiated treatments were also not associated with duration of symptoms and signs following the initial clinician visit.

Of the treatments prescribed by clinicians or independently chosen by patients following their initial office visit, only systemic corticosteroids plus high-potency topical corticosteroids were associated with a significantly shorter duration of itching (P=.005). No treatment was associated with reduced duration of erythema, papules, or vesicles. Use of topical soaps was associated with a longer duration of papules (P<.0001) and of total duration of signs or symptoms (P=.0004) compared with other treatments.

Location and characteristics of the rash were not associated with likelihood of recurrence following treatment. Post-visit use of a topical soap was associated with recurrence of itching (P=.001) and erythema (P=.01). Recurrence of erythema was also more frequent in patients prescribed topical astringents (beta coefficient=0.28; P=.008), and recurrence of papules was more common in patients treated with low-potency topical corticosteroids (P<.0001). These results and several others that almost reached statistical significance are shown in TABLE 2.

In the multivariable models, the only variable associated with duration of pruritus was the combination of systemic and high-potency topical corticosteroids (8 vs 12 days.) Use of only parenteral or only high-potency topical corticosteroids did not predict shorter duration of pruritus. Use of topical soaps was associated with longer duration of papules (33 vs 9.6 days) and longer duration of any symptoms (33 vs 13.9 days). It was also associated with a higher likelihood of recurrence of pruritus (chi square test [χ2], 10.67) and recurrence of erythema (χ2, 5.92) after initial resolution. Topical astringent use was predictive of recurrence of erythema (χ2, 7.01) and use of low-potency corticosteroids was associated with recurrence of papules (χ2, 20.96).

DISCUSSION

While network clinicians felt that studying poison ivy was of interest and importance, and we had preliminary survey information to suggest it was a common problem treated in primary care, our data suggest that clinical encounters for poison ivy are actually quite uncommon (less than 0.4% of all encounters) even during peak months. Our problems with recruitment were therefore unexpected, and we ended up with far fewer enrolled patients than we had projected, and needed, based on our power analysis. Also based on our preliminary survey, we anticipated considerably more variation in treatment approach than we found. Most clinicians recommended either an oral, parenteral, or high-potency topical corticosteroid, and some also recommended an oral antihistamine, usually diphenhydramine.

The literature and common sense suggest that most patients who seek medical treatment for poison ivy are primarily concerned about itching. Even with the smaller-than-anticipated number of participants in this study, we were able to show that the combination of a systemic (oral or parenteral) corticosteroid and a high-potency topical corticosteroid was associated with a statistically significant shorter duration of pruritus with no recurrence following treatment. We found no evidence that systemic corticosteroids alone, parenteral corticosteroids alone, or high-potency topical corticosteroids alone had any effect on duration of signs or symptoms, even at an alpha of .05. We also found no evidence that oral antihistamines were associated with a shorter duration of pruritus (P=.06); with a larger sample size, we might have found a difference.

Since only 2 patients used topical soaps following their initial clinician visit, the associations between use of these products and longer duration of signs and symptoms and with recurrence of signs and symptoms, although statistically significant, should be viewed with skepticism and with an eye toward possible confounders (eg, people who used these agents may have been more likely to notice and record minor symptoms). Furthermore, these agents have been effective only when used before or at the onset of the rash.

Study limitations. The study has a number of limitations. It had a high drop-out rate. Some patients might not have had poison ivy, but it is generally considered easy to diagnose with accuracy. We cannot be sure that all of the enrolled patients had Rhus dermatitis. Enrollment was based on the clinical impression of the patients’ primary care clinicians. The sample size reduced the power of the study to detect small differences in treatment effects and prevented more complex analyses (eg, combinations of medications, interactions).

The possibility of self-selection bias, weaknesses of the cohort design, and patient-reported outcome measures were additional limitations. The study was also carried out in a single southwestern state, which may not be representative of some other locations. However, it is one of only a few studies published on Rhus dermatitis and possibly the only one conducted in primary care settings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Cara Vaught, MPH, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, 900 NE 10th Street, Oklahoma City, OK 73104; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank the Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) and the OKPRN clinician members (as well as their staff and patients) for their contributions to this study. The authors also thank Bradley Long, Matthew Marr, and Kellie Hetherington for their involvement in the data collection for this study.

1. Epstein WL. Occupational poison ivy and oak dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:511-516.

2. Long D, Ballentine NH, Marks JG Jr. Treatment of poison ivy/oak allergic contact dermatitis with an extract of jewelweed. Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:150-153.

3. Amrol D, Keitel D, Hagaman D, et al. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of human allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:563-566.

4. Davila A, Laurora M, Fulton J, et al. A new topical agent, Zanfel, ameliorates urushiol-induced Toxicodendron allergic contact dermatitis [abstract 364]. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(suppl 4):S98.

5. Vernon HJ, Olsen EA. A controlled trial of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% in the treatment of experimentally induced Rhus dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:829-832.

6. Dickey RF. Parenteral short-term corticosteroid therapy in moderate to severe dermatoses. A comparative multiclinic study. Cutis. 1976;17:179-193.

7. Goodall J. Oral corticosteroids for poison ivy dermatitis. CMAJ. 2002;166:300-301.

8. Moe JF. How much steroid for poison ivy? Postgrad Med. 1999;106:21,24.

1. Epstein WL. Occupational poison ivy and oak dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:511-516.

2. Long D, Ballentine NH, Marks JG Jr. Treatment of poison ivy/oak allergic contact dermatitis with an extract of jewelweed. Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:150-153.

3. Amrol D, Keitel D, Hagaman D, et al. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of human allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:563-566.

4. Davila A, Laurora M, Fulton J, et al. A new topical agent, Zanfel, ameliorates urushiol-induced Toxicodendron allergic contact dermatitis [abstract 364]. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(suppl 4):S98.

5. Vernon HJ, Olsen EA. A controlled trial of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% in the treatment of experimentally induced Rhus dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:829-832.

6. Dickey RF. Parenteral short-term corticosteroid therapy in moderate to severe dermatoses. A comparative multiclinic study. Cutis. 1976;17:179-193.

7. Goodall J. Oral corticosteroids for poison ivy dermatitis. CMAJ. 2002;166:300-301.

8. Moe JF. How much steroid for poison ivy? Postgrad Med. 1999;106:21,24.

HIV update: Which single-tablet regimens, and when

› Offer all patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease antiretroviral therapy (ART) regardless of disease state or CD4 cell lymphocyte count. A

› Consider one of 6 recommended ART regimens for ART-naive patients. A

› Offer one of 6 alternative antiretroviral regimens to patients unable to tolerate one of the recommended regimens for reasons of toxicity, a pre-existing medical condition, or baseline viral resistance. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › James G, age 43, recently had blood work performed for a life insurance policy, and his human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test came back positive. At a follow-up office visit, Mr. G reports having anonymous male sexual partners when traveling to New York on business and rarely using condoms. His last HIV test was “about 4 years ago.” He is otherwise in good health, takes no regular medications, and is not married.

Having recently completed a primary care CME program on HIV disease, you order a CD4/T-cell count, an HIV RNA (viral load) test, and an HIV genotype drug resistance test on Mr. G, along with other baseline lab work, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel, and hepatitis panel. You schedule a follow-up visit with Mr. G in 2 weeks when all of the lab results will be available so that you can discuss his plan of care.

A diagnosis of HIV has moved from being a fatal disease to that of a chronic condition that can be effectively managed with combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens over an almost normal lifespan. As a result, the role of the primary care practitioner in the ongoing care of patients with HIV has grown and will continue to do so, making knowledge of these drug combinations vital.

20 years have changed everything

Combination ART has existed since 1996 when the first protease inhibitors (PIs) were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Prior to this, treatment was limited to mono or dual therapy with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs). These agents provided some short-term clinical benefit, but didn’t significantly improve patient survival and ultimately failed due to viral resistance.1

Since the approval of zidovudine (AZT) in 1987, the FDA has approved more than 25 drugs in 6 different classes for the treatment of HIV disease.2 These include the NRTIs, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), PIs, a fusion inhibitor (FI), a CCR5 antagonist, and, more recently, integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs). In addition, 2 drugs, cobicistat and ritonavir, are used solely to improve or “boost” the pharmacokinetic profiles of several antiretroviral drugs.2

Most of these newer agents are more potent, have a higher genetic barrier to resistance, and a longer half-life than their predecessors. Moreover, many are less toxic and thus more tolerable than older drugs. With the progressive development and approval of single-tablet regimens (STRs) that contain 3 or 4 drugs, the majority of patients with HIV in the United States now take just one pill per day to treat their infection, facilitating far greater medication adherence.

Initiation of antiretroviral therapy

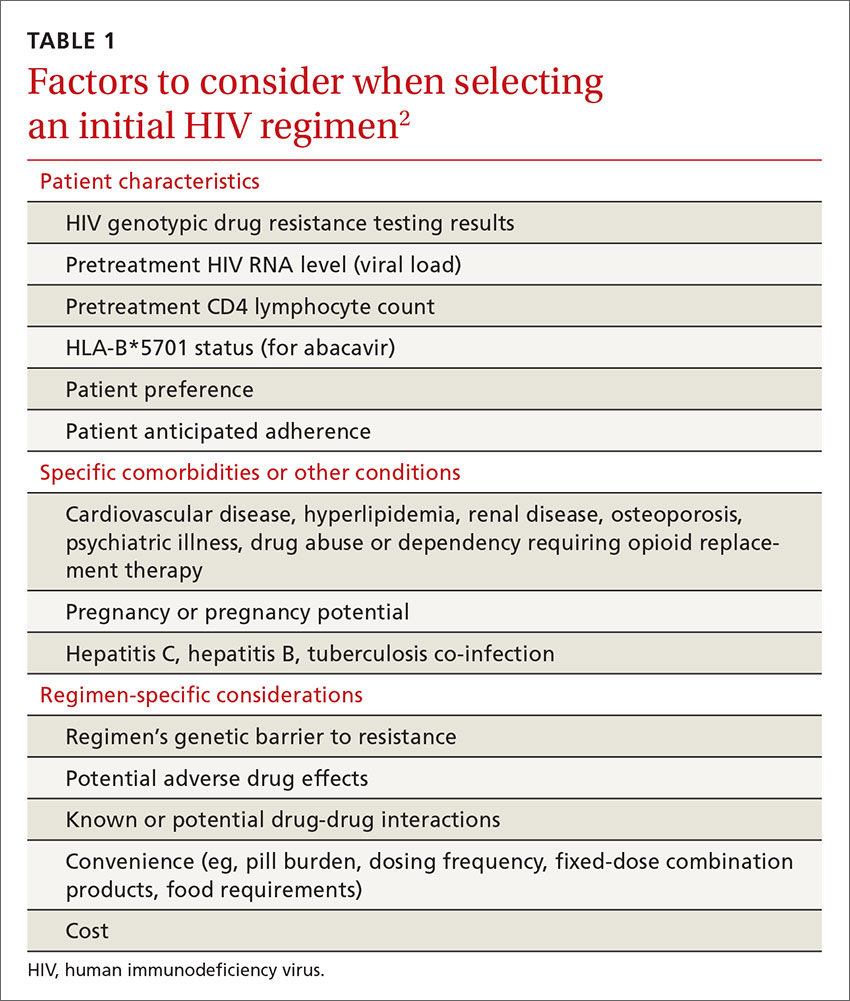

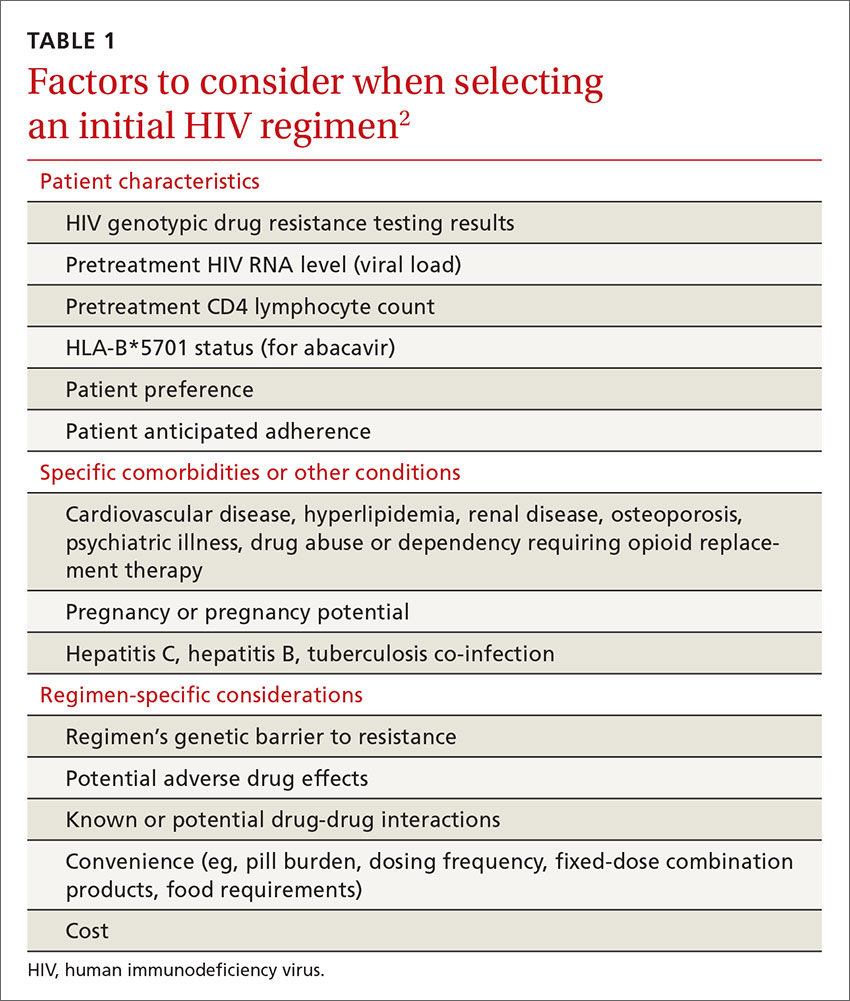

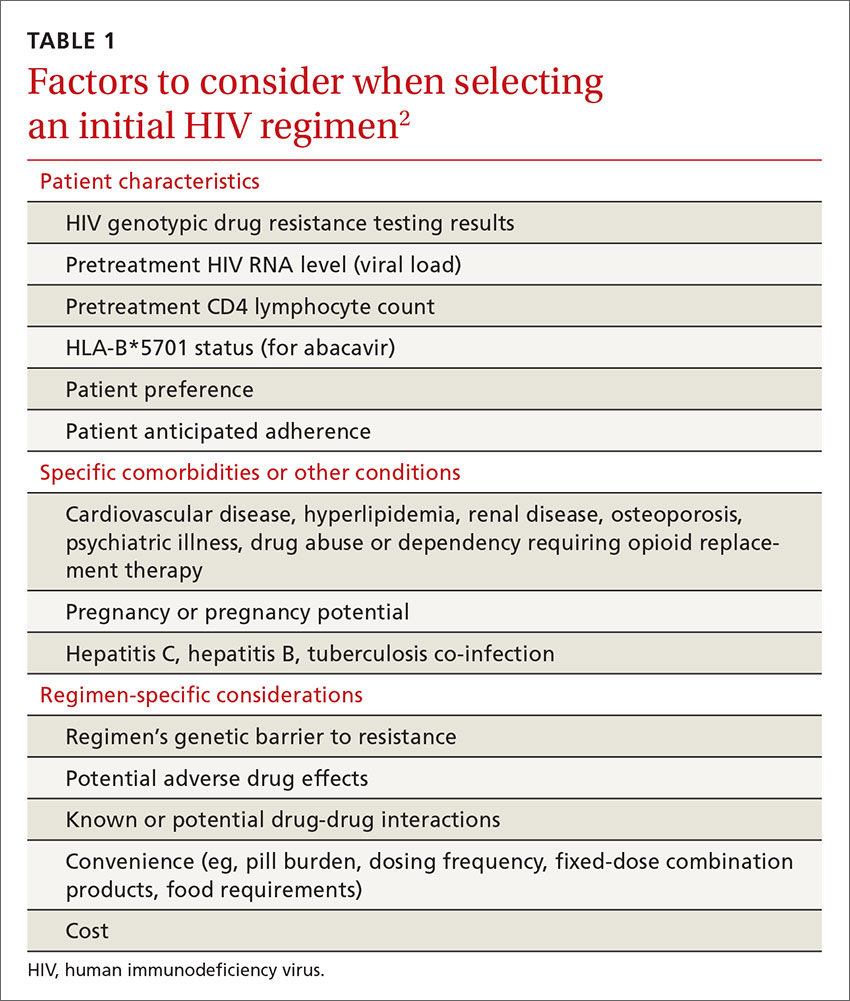

The US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines now recommend that all people infected with HIV, regardless of CD4 cell count, begin ART.2 The evidence for this recommendation comes largely from the START3 and TEMPRANO4 trials, which found that early initiation of ART significantly reduces morbidity and mortality associated with HIV. In addition, the HPTN 052 study concluded that early ART is associated with a 93% lower risk of viral transmission in serodiscordant heterosexual couples.5 The DHHS guidelines do note that when initiating ART, it is important to appropriately educate patients on the benefits of treatment and address strategies to optimize adherence.2 (For more on factors to consider when selecting an initial HIV regimen, see TABLE 1.2) On a case-by-case basis, ART may be deferred because of clinical and/or psychosocial factors, but it should never be withheld unless the risks clearly outweigh the benefits. Ideally, ART should be initiated as soon as possible after the initial diagnosis of HIV.

The DHHS guidelines divide treatment options into 3 categories:2

- Recommended regimens are backed by randomized controlled trials that show optimal and durable virologic efficacy, they have favorable tolerability and toxicity profiles, and they are easy to use.

- Alternative regimens have less or lower quality supporting data than recommended regimens. Although they are effective and may be optimal for certain individual patients, they have potential disadvantages and/or limitations in certain populations.

- Other regimens have limited supporting data, reduced virologic activity, a higher pill burden, more drug interactions, and greater toxicity.

Currently recommended first-line therapies

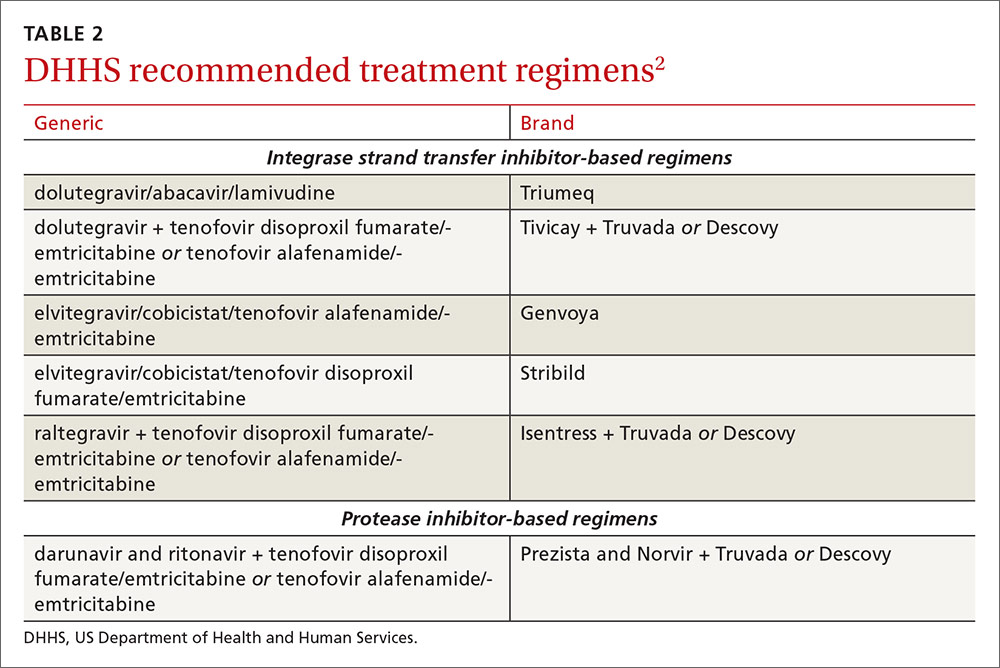

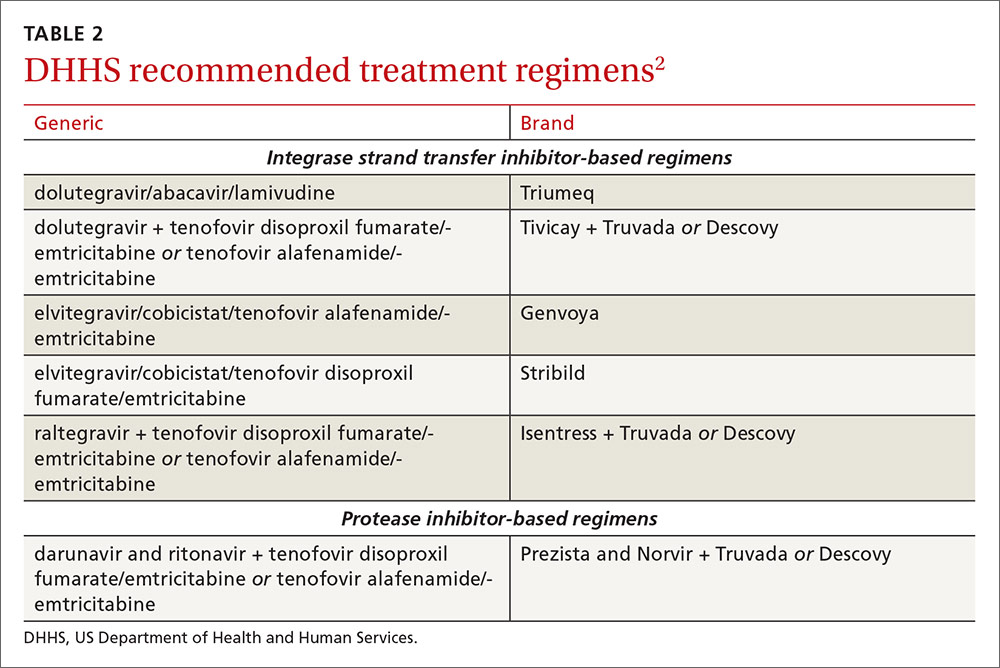

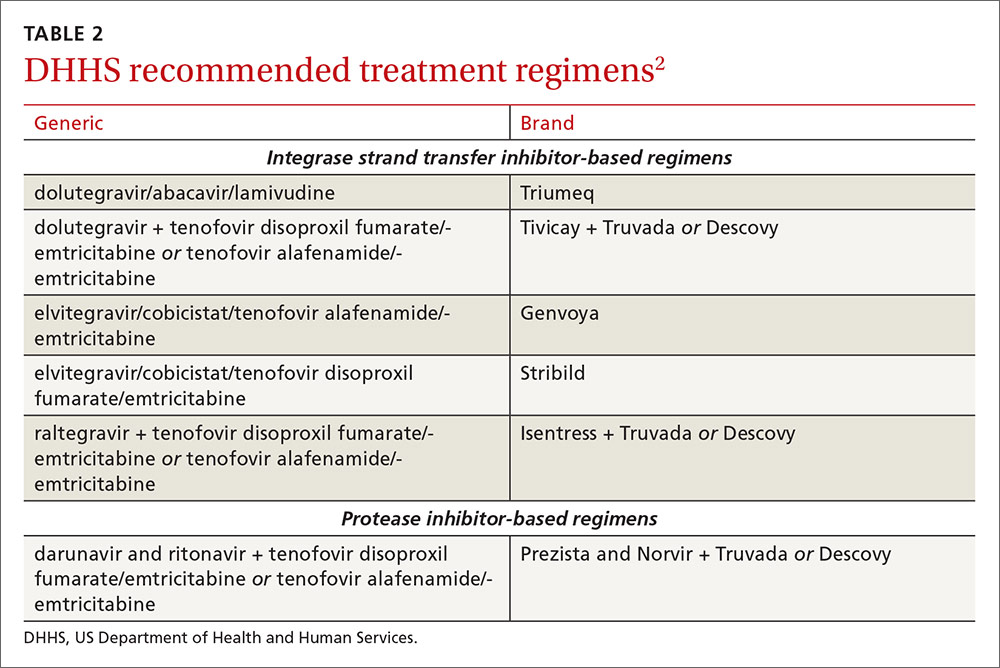

An antiretroviral regimen for a treatment-naive patient should consist of 2 NRTIs in combination with a third active antiretroviral drug from one of 3 drug classes. These include: an INSTI, a boosted PI, or, in some situations, an NNRTI. The DHHS guidelines panel currently recommends 6 different ART combinations as first-line treatment in treatment-naive patients (TABLE 2).2

INSTI-based regimens

Dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine (Triumeq). Approved by the FDA as a single-tablet regimen in 2014, the combination of dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine has proven to be highly effective and well-tolerated in many clinical trials.6-9 However, before this regimen is started, patients must be screened for the HLA-B*5701 allele, which predicts hypersensitivity to abacavir.10 Assessing patients’ risk for cardiovascular disease is also advised because some data suggest that abacavir may increase the risk of cardiovascular events, although this remains controversial.2

Dolutegravir is generally well-tolerated with minimal adverse effects (≥2% incidence of headache and insomnia) and toxicity.11 Dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine should be taken 2 hours before or 6 hours after taking antacids or laxatives, sucralfate, and oral supplements with iron or calcium. However, it may be taken with calcium or iron supplements if it is also taken with food.11 Dolutegravir increases levels of metformin about 2-fold, so patients should not take more than 1000 mg/d of this oral hypoglycemic agent.11

Dolutegravir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Tivicay plus Truvada). The combination of dolutegravir plus fixed-dose tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine is administered as 2 pills per day. Because tenofovir disoproxil fumarate can cause proximal renal tubular dysfunction, phosphate wasting, and decreased bone mineral density (BMD), avoid prescribing it for patients with underlying renal dysfunction (creatinine clearance [CrCl] <50 mL/min) and prescribe it cautiously for patients with hypertension or diabetes who are at increased risk of renal disease. Emtricitabine is generally safe and well tolerated, but the dose should be reduced in patients with renal insufficiency, which would preclude the use of this fixed-dose combination.12

Elvitegravir/cobicistat/tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Genvoya). The newer 4-drug combination of elvitegravir/cobicistat/tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine that was approved by the FDA in November 2015,13 contains the more recently approved form of tenofovir, which can be used in patients who have a CrCl as low as 30 mL/min. Compared to formulations containing tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, the newer tenofovir alafenamide formulation achieves higher intracellular levels in CD4 lymphocytes (but not in renal tubular cells). This allows for a lower dose of the drug and a smaller tablet size with co-formulation. It does not appear to cause kidney problems or loss of BMD as can be seen with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.14 This newer single-tablet regimen may be best suited for older patients with HIV or those with comorbidities such as hypertension or diabetes.

Elvitegravir/cobicistat/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Stribild). The FDA approved the combination of elvitegravir/cobicistat/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine as a single-tablet regimen in 2012. The integrase inhibitor, elvitegravir, requires boosting with the CYP3A inhibitor, cobicistat, and should be taken with food.15 Two clinical trials demonstrated the superior efficacy of elvitegravir compared to a boosted PI and NNRTI-based regimen.16,17 Elvitegravir is generally well tolerated, but sometimes causes dyspepsia, nausea, or diarrhea.15 Similar to dolutegravir, it should not be taken concurrently with certain supplements—in this case, those containing aluminum, calcium, iron, magnesium, or zinc.15 Because it contains tenofovir disoproxil fumarate as an active agent, it should not be used in patients with a CrCl of <70 mL/min.15

Cobicistat inhibits tubular secretion of creatinine, so it may produce an elevation in serum creatinine without actually affecting glomerular function. Cobicistat may also cause drug-drug interactions with certain antiarrhythmics, sedative-hypnotics, and erectile dysfunction agents, and is contraindicated with some statins, anticonvulsants, and ergot derivatives.18

Raltegravir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Isentress plus Truvada). The combination of the integrase inhibitor raltegravir plus fixed-dose tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine has been recommended by the DHHS as first-line therapy for approximately 5 years. The recommendation is based mainly on data from the STARTMRK trial, a phase III non-inferiority trial that followed more than 500 patients for 5 years and concluded that raltegravir/tenofovir/emtricitabine has superior efficacy with fewer drug-related adverse effects than efavirenz/tenofovir/emtricitabine.19 The overall pill burden with this regimen is 3 tablets per day. Although highly effective, the main drawbacks of raltegravir are that it must be dosed twice daily (which may be less preferable if adherence is a concern) and the genetic barrier to resistance is lower than that of the other 2 approved integrase inhibitors. There is a once-daily formulation of raltegravir that's expected to be available late in 2017.20

Adverse effects and toxicities (except the renal and bone effects due to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate mentioned earlier) and drug interactions with this regimen are infrequent. Raltegravir can be taken with or without food. Concurrent use of antacids that contain aluminum or magnesium may reduce absorption of raltegravir and so should be avoided.21

PI-based regimen

Darunavir (Prezista) and ritonavir (Norvir) plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada). PIs were once the key component of all ART regimens; however, boosted darunavir is now the only PI-based regimen currently recommended as first-line therapy. It is taken as 3 tablets once daily. If the co-formulation with cobicistat is used, just 2 tablets daily are required. One advantage with darunavir with either of the boosting agents is that it does not appear to cause insulin resistance or dyslipidemia as occurs with older PIs, such as indinavir and lopinavir.2 The boosting agents do, however, increase the likelihood of drug-drug interactions. As with all PIs, darunavir has a very high genetic barrier to resistance, which is important in patients for whom adherence is a concern.

Adverse effects of the PIs may include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, all of which are typically mild and self-limiting.22 Co-formulation of darunavir with cobicistat, tenofovir alafenamide, and emtricitabine is in phase III studies. Projected to be available in late 2017, it will provide yet another daily STR option.23

The addition of fixed-dose tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine

In July 2016, the DHHS panel made some additions to their guidelines to reflect the FDA approval of 3 fixed-dose combination products that contain tenofovir alafenamide. Specifically, the combination of tenofovir alafenamide and emtricitabine is recommended for use with the integrase inhibitors—dolutegravir or raltegravir. It is also recommended in combination with ritonavir-boosted darunavir.

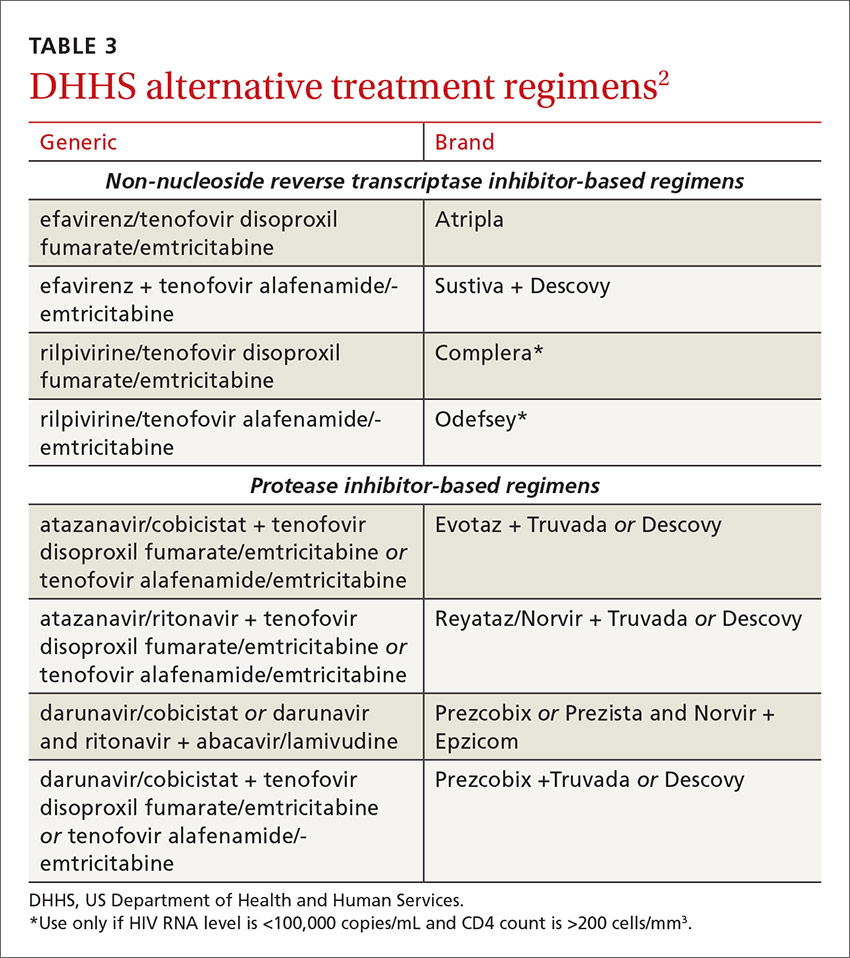

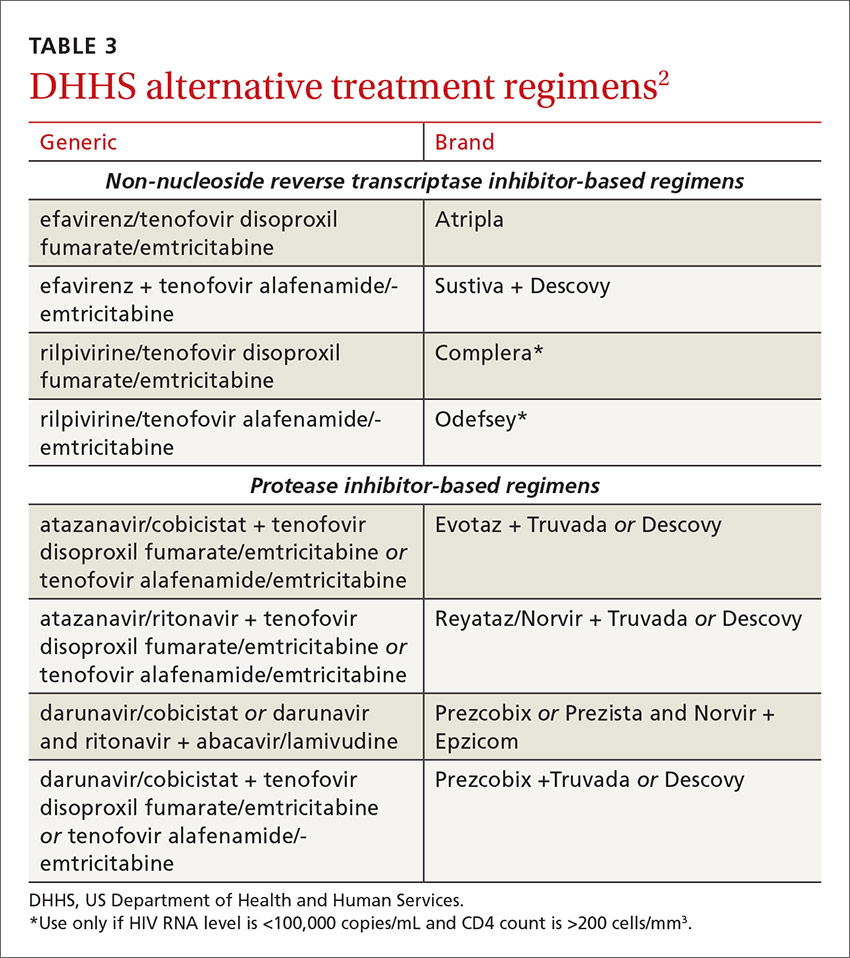

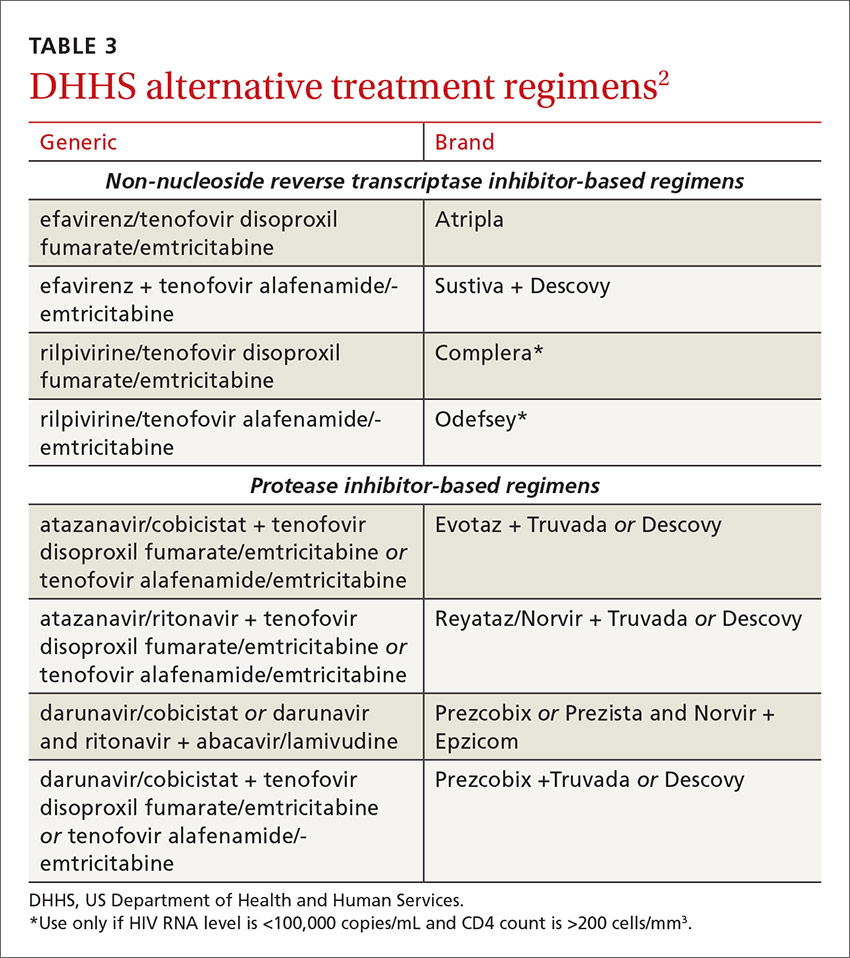

DHHS “alternative” and“other” regimens

The DHHS guidelines also include “alternative” (TABLE 32) and “other” regimens (available at: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines) that may be used when first-line regimens may not. These second-line options are very effective, but have some possible clinical disadvantages or limitations. They are also less well supported by data from clinical trials. However, in certain situations, depending on an individual patient’s comorbidities, inability to tolerate one of the preferred regimens, or personal preferences, an alternative regimen may be the optimal choice.

Under the category of alternative regimens, the panel has included tenofovir alafenamide and emtricitabine in combination with the NNRTI efavirenz or with ritonavir- or cobicistat-boosted atazanavir or darunavir.

The third group or “other” regimens have reduced virologic activity, increased toxicity, and even more limited data from clinical trials. Generally, medications from the DHHS “alternative” and “other” categories should be prescribed in consultation with an HIV specialist.

The future of ART

The currently available drugs are highly effective in fully suppressing HIV and allowing for immune recovery and clinical stability for most patients. Life expectancy for patients living with HIV is estimated to be approaching that of uninfected adults—provided they remain on ART.24 As a way to further simplify ART, current clinical trials are looking at 2-drug regimens including an integrase inhibitor with an NRTI, an INSTI, or an NNRTI, or a PI with one NRTI.25,26 This approach could further reduce pill burden and toxicity and substantially decrease the cost of long-term treatment.27 Also on the horizon are long-acting injectable antiretroviral drugs that will likely be available for clinical use in the next 2 to 3 years.28,29

CASE › At the 2-week follow-up visit, you discuss with Mr. G that his CD4+ count is 390 cells/mm3, his HIV RNA level is 32,450 copies/mL, and his HIV genotype test showed no antiviral drug resistance. Explaining that all patients with HIV should be treated with antiviral therapy regardless of CD4+ count, you recommend that Mr. G begin taking fixed-dose tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine/elvitegravir/cobicistat (Stribild), noting that it is one of the regimens recommended by the DHHS national treatment guidelines. You provide a patient handout that discusses dosing and adverse effects, including nausea and headache. The patient’s pharmacy was contacted and it was determined that Mr. G’s co-pay for the drug would be $50, which he found acceptable.

In addition, you discuss the importance of good adherence to this medication, and instruct Mr. G to contact the office via phone or patient portal for any concerns or questions that arise after starting the medication. Lastly, you advise him to return in 4 weeks for follow-up blood testing, including viral load monitoring, and additional care, if needed, and strongly recommend that he begin using condoms regularly.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey T. Kirchner, DO, FAAFP, AAHIVS, Medical Director, LGHP Comprehensive Care, 554 North Duke St., 3rd Floor, Lancaster, PA 1760; [email protected].

1. Concorde: MRC/ANRS randomised double-blind controlled trial of immediate and deferred zidovudine in symptom-free HIV infection. Concorde Coordinating Committee. Lancet. 1994;343:871-881.

2. Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Available at: http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-treatment-guidelines/0. Accessed July 17, 2016.

3. The INSIGHT START Study Group. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:795-807.

4. The TEMPRANO ANRS 12136 Study Group. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:808-822.

5. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:830-839.

6. Molina JM, Clotet B, van Lunzen J,et al. Once-daily dolutegravir versus darunavir plus ritonavir for treatment-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (FLAMINGO): 96 week results from a randomized, open-label, phase 3b study. Lancet HIV. 2015;2:e127-136.

7. Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1807-1818.

8. Van Lunzen J, Maggiolo F, Arribas JR, et al. Once daily dolutegravir (S/GSK1349572) in combination therapy in antiretroviral-naïve adults with HIV: planned interim 48 week results from SPRING-1, a dose-ranging, randomized, phase 2b trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:111-118.

9. Stellbrink HJ, Reynes J, Lazzarin A, et al. Dolutegravir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1: 96-week results from a randomized dose-ranging study. AIDS. 2013; 27:1771-1778.

10. Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G. HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:568-579.

11. AIDSinfo Drug Database. Dolutegravir. Available at: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/drugs/509/dolutegravir/0/professional. Accessed July 17, 2016.

12. AIDSinfo Drug Database. Emtricitabine. Available at: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/drugs/208/emtricitabine/0/patient. Accessed July 17, 2016.

13. AIDSinfo Drug Database. Elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide fumarate. Available at: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/drugs/553/genvoya/0/professional. Accessed July 17, 2016.

14. Ray AS, Fordyce MW, Hitchcock, MJM. Tenofovir alafenamide: A novel prodrug of tenofovir for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus. Antiviral Res. 2016;125:63-70.

15. AIDSinfo Drug Database. Elvitegravir. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/drugs/421/elvitegravir/0/professional

16. Wohl DA, Cohen C, Gallant JE, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of single-tablet regimen elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF versus single-tablet regimen efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: analysis of week 144 results. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:e118-120.

17. Clumeck N, Molina JM, Henry K, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of single-tablet regimen elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF vs ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus emtricitabine/tenofovir for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: analysis of week 144 results. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:e121-124.

18. AIDSinfo Drug Database. Cobicistat. Available at: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/drugs/537/evotaz/0/patient/. Accessed July 17, 2016.

19. Rockstroh JK, DeJesus E, Lennox JL, et al. Durable efficacy and safety of raltegravir versus efavirenz when combined with tenofovir/emtricitabine in treatment-naïve HIV-1 infected patients: final 5-year results from STARTMRK. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:77-85.

20. Cahn P, Kaplan R, Sax P, et al. Raltegravir (RAL) 1200 mg once daily (QD) is non-inferior to RAL 400 mg twice daily (BID), in combination with tenofovir/emtricitabine, in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected subjects: week 48 results. Abstract FRAB0103LB presented at: 21st International AIDS Conference; July 18-22, 2016; Durban, South Africa.

21. Hicks C, Gulick RM. Raltegravir: the first HIV type 1 integrase inhibitor. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:931-939.

22. Prescriber’s Letter. HIV/AIDS Pharmacotherapy Review. Vol. 2015; Course no. 215. Available at: http://prescribersletter.therapeuticresearch.com/ce/cecourse.aspx?pc=15-215. Accessed October 6

23. AIDSinfo Drug Database. Tenofovir alafenamide. Available at: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/drugs/514/tenofovir-alafenamide/0/patient. Accessed September 27, 2016.

24. Marcus JL, Chao C, Leyden W, et al. Narrowing the gap in life expectancy for HIV+ compared with HIV- individuals. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. February 22-25, 2016, Boston. Abstract 54.

25. Gubavu C, Prazuck T, Niang M, et al. Dolutegravir-based monotherapy or dual therapy maintains a high proportion of viral suppression even in highly experienced HIV-1-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:1046-1050.

26. Margolis DA, Brinson CC, Smith GHR. Cabotegravir plus rilpivirine, once a day, after induction with cabotegravir plus nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in antiretroviral naïve adults with HIV-1 infection (LATTE): a randomised, phase 2b, dose-ranging trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:1145-1155.

27. Girouard MP, Sax PE, Parker RA, et al. The cost-effectiveness and budget impact of 2-drug dolutegravir-lamivudine regimens for the treatment of HIV infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 62:784-791.

28. Margolis DA, Gonzalez-Garcia J, Stellbrink HJ, et al. Cabotegravir + rilpivirine as long-acting maintenance therapy: LATTE-2 week 32 results. Abstract number 31 LB. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. February 22-25, 2016; Boston, MA.

29. Murray MI, Markowitz M, Frank I, et al. Tolerability and acceptability of cabotegravir LA injection: results from ECLAIR study. Abstract number 471. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. February 22-25, 2016; Boston, MA.

› Offer all patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease antiretroviral therapy (ART) regardless of disease state or CD4 cell lymphocyte count. A

› Consider one of 6 recommended ART regimens for ART-naive patients. A

› Offer one of 6 alternative antiretroviral regimens to patients unable to tolerate one of the recommended regimens for reasons of toxicity, a pre-existing medical condition, or baseline viral resistance. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › James G, age 43, recently had blood work performed for a life insurance policy, and his human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test came back positive. At a follow-up office visit, Mr. G reports having anonymous male sexual partners when traveling to New York on business and rarely using condoms. His last HIV test was “about 4 years ago.” He is otherwise in good health, takes no regular medications, and is not married.

Having recently completed a primary care CME program on HIV disease, you order a CD4/T-cell count, an HIV RNA (viral load) test, and an HIV genotype drug resistance test on Mr. G, along with other baseline lab work, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel, and hepatitis panel. You schedule a follow-up visit with Mr. G in 2 weeks when all of the lab results will be available so that you can discuss his plan of care.

A diagnosis of HIV has moved from being a fatal disease to that of a chronic condition that can be effectively managed with combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens over an almost normal lifespan. As a result, the role of the primary care practitioner in the ongoing care of patients with HIV has grown and will continue to do so, making knowledge of these drug combinations vital.

20 years have changed everything

Combination ART has existed since 1996 when the first protease inhibitors (PIs) were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Prior to this, treatment was limited to mono or dual therapy with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs). These agents provided some short-term clinical benefit, but didn’t significantly improve patient survival and ultimately failed due to viral resistance.1

Since the approval of zidovudine (AZT) in 1987, the FDA has approved more than 25 drugs in 6 different classes for the treatment of HIV disease.2 These include the NRTIs, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), PIs, a fusion inhibitor (FI), a CCR5 antagonist, and, more recently, integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs). In addition, 2 drugs, cobicistat and ritonavir, are used solely to improve or “boost” the pharmacokinetic profiles of several antiretroviral drugs.2

Most of these newer agents are more potent, have a higher genetic barrier to resistance, and a longer half-life than their predecessors. Moreover, many are less toxic and thus more tolerable than older drugs. With the progressive development and approval of single-tablet regimens (STRs) that contain 3 or 4 drugs, the majority of patients with HIV in the United States now take just one pill per day to treat their infection, facilitating far greater medication adherence.

Initiation of antiretroviral therapy

The US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines now recommend that all people infected with HIV, regardless of CD4 cell count, begin ART.2 The evidence for this recommendation comes largely from the START3 and TEMPRANO4 trials, which found that early initiation of ART significantly reduces morbidity and mortality associated with HIV. In addition, the HPTN 052 study concluded that early ART is associated with a 93% lower risk of viral transmission in serodiscordant heterosexual couples.5 The DHHS guidelines do note that when initiating ART, it is important to appropriately educate patients on the benefits of treatment and address strategies to optimize adherence.2 (For more on factors to consider when selecting an initial HIV regimen, see TABLE 1.2) On a case-by-case basis, ART may be deferred because of clinical and/or psychosocial factors, but it should never be withheld unless the risks clearly outweigh the benefits. Ideally, ART should be initiated as soon as possible after the initial diagnosis of HIV.

The DHHS guidelines divide treatment options into 3 categories:2

- Recommended regimens are backed by randomized controlled trials that show optimal and durable virologic efficacy, they have favorable tolerability and toxicity profiles, and they are easy to use.