User login

Preventive Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Identifying people who might be at risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) before the trauma—and teaching them preventive coping skills—could reduce or prevent long-term effects, according to University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom, and King’s College London, United Kingdom, researchers.

They assessed 453 newly recruited paramedics every 4 months for 2 years. Of those, 386 paramedics participated in follow-up interviews.

Related: Let’s Dance: A Holistic Approach to Treating Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Over the 2 years, 32 participants (8.3%) had an episode of PTSD, and 41 participants had (10.6%) an episode of major depression (MD). Most of the episodes were moderate and short lived. In most cases, the participant had recovered by the next 4-month assessment. However, at 2 years, those who had experienced episodes of PTSD or MD during the follow-up period reported more days off work, poorer sleep, poorer quality of life, and greater burn out as well as weight gain (mean gain, 6.9 kg) for those with P

Ten participants who developed PTSD received treatment during follow-up, as did 12 participants who developed MD. Five of 9 participants who had recurrent P

Related: Telehealth for Native Americans With PTSD

The researchers tested a number of possible pretrauma predictors of PTSD and MD. They correlated several: cognitive style (eg, suppression, rumination, intentional numbing), coping style (eg, avoidant styles, such as wishful thinking), and psychological traits (eg, neuroticism). However, they found rumination about memories of stressful events uniquely predicted an episode of PTSD. Perceived resilience uniquely predicted an episode of MD.

Interestingly, about 42% of the study participants had a psychiatric history before training—more than the general population. That might be a factor that draws them to emergency work, the researchers suggest.

Some predictors, such as psychiatric history, are fixed, the researchers note. But others, such as cognitive styles, can be modified or taught. Studies have shown that rumination can be redirected through training in concrete thinking, for instance, and psychoeducation and cognitive behavioral techniques (eg, modifying interpretations of stressful events) have been used to strengthen resilience. The predictors they identified in their study could serve as targets, the researchers suggest, for modifying future resilience programs.

Source:

Wild J, Smith KV, Thompson E, Béar F, Lommen MJ, Ehlers A. Psychol Med. 2016;46(12):2571-2582. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000532.

Identifying people who might be at risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) before the trauma—and teaching them preventive coping skills—could reduce or prevent long-term effects, according to University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom, and King’s College London, United Kingdom, researchers.

They assessed 453 newly recruited paramedics every 4 months for 2 years. Of those, 386 paramedics participated in follow-up interviews.

Related: Let’s Dance: A Holistic Approach to Treating Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Over the 2 years, 32 participants (8.3%) had an episode of PTSD, and 41 participants had (10.6%) an episode of major depression (MD). Most of the episodes were moderate and short lived. In most cases, the participant had recovered by the next 4-month assessment. However, at 2 years, those who had experienced episodes of PTSD or MD during the follow-up period reported more days off work, poorer sleep, poorer quality of life, and greater burn out as well as weight gain (mean gain, 6.9 kg) for those with P

Ten participants who developed PTSD received treatment during follow-up, as did 12 participants who developed MD. Five of 9 participants who had recurrent P

Related: Telehealth for Native Americans With PTSD

The researchers tested a number of possible pretrauma predictors of PTSD and MD. They correlated several: cognitive style (eg, suppression, rumination, intentional numbing), coping style (eg, avoidant styles, such as wishful thinking), and psychological traits (eg, neuroticism). However, they found rumination about memories of stressful events uniquely predicted an episode of PTSD. Perceived resilience uniquely predicted an episode of MD.

Interestingly, about 42% of the study participants had a psychiatric history before training—more than the general population. That might be a factor that draws them to emergency work, the researchers suggest.

Some predictors, such as psychiatric history, are fixed, the researchers note. But others, such as cognitive styles, can be modified or taught. Studies have shown that rumination can be redirected through training in concrete thinking, for instance, and psychoeducation and cognitive behavioral techniques (eg, modifying interpretations of stressful events) have been used to strengthen resilience. The predictors they identified in their study could serve as targets, the researchers suggest, for modifying future resilience programs.

Source:

Wild J, Smith KV, Thompson E, Béar F, Lommen MJ, Ehlers A. Psychol Med. 2016;46(12):2571-2582. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000532.

Identifying people who might be at risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) before the trauma—and teaching them preventive coping skills—could reduce or prevent long-term effects, according to University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom, and King’s College London, United Kingdom, researchers.

They assessed 453 newly recruited paramedics every 4 months for 2 years. Of those, 386 paramedics participated in follow-up interviews.

Related: Let’s Dance: A Holistic Approach to Treating Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Over the 2 years, 32 participants (8.3%) had an episode of PTSD, and 41 participants had (10.6%) an episode of major depression (MD). Most of the episodes were moderate and short lived. In most cases, the participant had recovered by the next 4-month assessment. However, at 2 years, those who had experienced episodes of PTSD or MD during the follow-up period reported more days off work, poorer sleep, poorer quality of life, and greater burn out as well as weight gain (mean gain, 6.9 kg) for those with P

Ten participants who developed PTSD received treatment during follow-up, as did 12 participants who developed MD. Five of 9 participants who had recurrent P

Related: Telehealth for Native Americans With PTSD

The researchers tested a number of possible pretrauma predictors of PTSD and MD. They correlated several: cognitive style (eg, suppression, rumination, intentional numbing), coping style (eg, avoidant styles, such as wishful thinking), and psychological traits (eg, neuroticism). However, they found rumination about memories of stressful events uniquely predicted an episode of PTSD. Perceived resilience uniquely predicted an episode of MD.

Interestingly, about 42% of the study participants had a psychiatric history before training—more than the general population. That might be a factor that draws them to emergency work, the researchers suggest.

Some predictors, such as psychiatric history, are fixed, the researchers note. But others, such as cognitive styles, can be modified or taught. Studies have shown that rumination can be redirected through training in concrete thinking, for instance, and psychoeducation and cognitive behavioral techniques (eg, modifying interpretations of stressful events) have been used to strengthen resilience. The predictors they identified in their study could serve as targets, the researchers suggest, for modifying future resilience programs.

Source:

Wild J, Smith KV, Thompson E, Béar F, Lommen MJ, Ehlers A. Psychol Med. 2016;46(12):2571-2582. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000532.

Improving cognitive function in cancer survivors

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study suggests a computer program known as InsightTM may help improve cognitive function and overall well-being in cancer survivors.

The study included subjects who reported persistent problems with concentration and/or memory after receiving chemotherapy.

Using the Insight program significantly improved the subjects’ self-reported cognitive function and lowered their levels of anxiety, depression, fatigue, and stress.

However, there was no significant difference in the results of objective neuropsychological function tests between subjects who used the Insight program and subjects who received standard care.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest cognitive intervention study that has shown a benefit for patients who are reporting persistent cognitive symptoms following chemotherapy,” said study author Victoria J. Bray, MD, of the University of Sydney in Australia.

About the study

Dr Bray and her colleagues enrolled 242 adult cancer survivors in Australia who had completed at least 3 cycles of chemotherapy in the prior 6 months to 60 months and reported persistent cognitive symptoms.

The subjects’ median age was 53 (range, 23 to 74). Nearly all were women (95%), and 89% had survived breast cancer.

At the beginning of the study, all subjects received a personalized, 30-minute telephone consultation that provided tips and strategies for coping with cognitive problems in daily life.

Subjects were then randomized to Insight (used at home) or standard oncology care per their treating physician.

The primary outcome of the study was self-reported cognitive function, which was assessed using a validated questionnaire known as FACT-COG. It evaluates perceived cognitive impairments, perceived cognitive abilities, and the impact of perceived cognitive impairment on quality of life.

Separate measures were used to evaluate objective neuropsychological function, anxiety/depression, fatigue, and stress.

About the intervention

Dr Bray and her colleagues described Insight as a neurocognitive learning program that uses exercises intended to improve cognition through speed and accuracy of information processing.

The program targets visual precision, divided attention, working memory, field of view, and visual processing speed, which are frequently affected in patients with cancer.

Subjects received the Insight program in disc form and were advised to use the program for 40 minutes 4 times a week for 15 weeks (40 hours total). The program had a built-in measure that could determine subjects’ compliance.

Key findings

Self-reported cognitive function was significantly better in the Insight group than the standard care group, both at the end of the 15-week program and 6 months later.

In addition, Insight participants had significantly lower levels of anxiety, depression, and fatigue immediately after the intervention, significant improvements in quality of life at 6 months, and significant improvements in stress at both time points.

Results of objective neuropsychological function tests were not significantly different between the Insight group and the standard care group, either immediately after the intervention or at 6 months.

Next steps

The researchers said longer follow-up is needed to determine if the effects of the Insight program are long-lasting. And there are still a number of other unanswered questions to be addressed in future research.

For one, it is unclear which method of delivering cognitive rehabilitation is better. A self-directed program such as this one may be suitable for some cancer survivors, while a group-based program may work better for others. It’s also unclear what the ideal duration and “dose” of cognitive training should be.

“If we could identify patients who are at risk of cognitive impairment, we could intervene earlier and possibly achieve even better results,” Dr Bray said. “We would also like to explore whether there is added benefit from combining cognitive training with physical exercise.” ![]()

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study suggests a computer program known as InsightTM may help improve cognitive function and overall well-being in cancer survivors.

The study included subjects who reported persistent problems with concentration and/or memory after receiving chemotherapy.

Using the Insight program significantly improved the subjects’ self-reported cognitive function and lowered their levels of anxiety, depression, fatigue, and stress.

However, there was no significant difference in the results of objective neuropsychological function tests between subjects who used the Insight program and subjects who received standard care.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest cognitive intervention study that has shown a benefit for patients who are reporting persistent cognitive symptoms following chemotherapy,” said study author Victoria J. Bray, MD, of the University of Sydney in Australia.

About the study

Dr Bray and her colleagues enrolled 242 adult cancer survivors in Australia who had completed at least 3 cycles of chemotherapy in the prior 6 months to 60 months and reported persistent cognitive symptoms.

The subjects’ median age was 53 (range, 23 to 74). Nearly all were women (95%), and 89% had survived breast cancer.

At the beginning of the study, all subjects received a personalized, 30-minute telephone consultation that provided tips and strategies for coping with cognitive problems in daily life.

Subjects were then randomized to Insight (used at home) or standard oncology care per their treating physician.

The primary outcome of the study was self-reported cognitive function, which was assessed using a validated questionnaire known as FACT-COG. It evaluates perceived cognitive impairments, perceived cognitive abilities, and the impact of perceived cognitive impairment on quality of life.

Separate measures were used to evaluate objective neuropsychological function, anxiety/depression, fatigue, and stress.

About the intervention

Dr Bray and her colleagues described Insight as a neurocognitive learning program that uses exercises intended to improve cognition through speed and accuracy of information processing.

The program targets visual precision, divided attention, working memory, field of view, and visual processing speed, which are frequently affected in patients with cancer.

Subjects received the Insight program in disc form and were advised to use the program for 40 minutes 4 times a week for 15 weeks (40 hours total). The program had a built-in measure that could determine subjects’ compliance.

Key findings

Self-reported cognitive function was significantly better in the Insight group than the standard care group, both at the end of the 15-week program and 6 months later.

In addition, Insight participants had significantly lower levels of anxiety, depression, and fatigue immediately after the intervention, significant improvements in quality of life at 6 months, and significant improvements in stress at both time points.

Results of objective neuropsychological function tests were not significantly different between the Insight group and the standard care group, either immediately after the intervention or at 6 months.

Next steps

The researchers said longer follow-up is needed to determine if the effects of the Insight program are long-lasting. And there are still a number of other unanswered questions to be addressed in future research.

For one, it is unclear which method of delivering cognitive rehabilitation is better. A self-directed program such as this one may be suitable for some cancer survivors, while a group-based program may work better for others. It’s also unclear what the ideal duration and “dose” of cognitive training should be.

“If we could identify patients who are at risk of cognitive impairment, we could intervene earlier and possibly achieve even better results,” Dr Bray said. “We would also like to explore whether there is added benefit from combining cognitive training with physical exercise.” ![]()

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study suggests a computer program known as InsightTM may help improve cognitive function and overall well-being in cancer survivors.

The study included subjects who reported persistent problems with concentration and/or memory after receiving chemotherapy.

Using the Insight program significantly improved the subjects’ self-reported cognitive function and lowered their levels of anxiety, depression, fatigue, and stress.

However, there was no significant difference in the results of objective neuropsychological function tests between subjects who used the Insight program and subjects who received standard care.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest cognitive intervention study that has shown a benefit for patients who are reporting persistent cognitive symptoms following chemotherapy,” said study author Victoria J. Bray, MD, of the University of Sydney in Australia.

About the study

Dr Bray and her colleagues enrolled 242 adult cancer survivors in Australia who had completed at least 3 cycles of chemotherapy in the prior 6 months to 60 months and reported persistent cognitive symptoms.

The subjects’ median age was 53 (range, 23 to 74). Nearly all were women (95%), and 89% had survived breast cancer.

At the beginning of the study, all subjects received a personalized, 30-minute telephone consultation that provided tips and strategies for coping with cognitive problems in daily life.

Subjects were then randomized to Insight (used at home) or standard oncology care per their treating physician.

The primary outcome of the study was self-reported cognitive function, which was assessed using a validated questionnaire known as FACT-COG. It evaluates perceived cognitive impairments, perceived cognitive abilities, and the impact of perceived cognitive impairment on quality of life.

Separate measures were used to evaluate objective neuropsychological function, anxiety/depression, fatigue, and stress.

About the intervention

Dr Bray and her colleagues described Insight as a neurocognitive learning program that uses exercises intended to improve cognition through speed and accuracy of information processing.

The program targets visual precision, divided attention, working memory, field of view, and visual processing speed, which are frequently affected in patients with cancer.

Subjects received the Insight program in disc form and were advised to use the program for 40 minutes 4 times a week for 15 weeks (40 hours total). The program had a built-in measure that could determine subjects’ compliance.

Key findings

Self-reported cognitive function was significantly better in the Insight group than the standard care group, both at the end of the 15-week program and 6 months later.

In addition, Insight participants had significantly lower levels of anxiety, depression, and fatigue immediately after the intervention, significant improvements in quality of life at 6 months, and significant improvements in stress at both time points.

Results of objective neuropsychological function tests were not significantly different between the Insight group and the standard care group, either immediately after the intervention or at 6 months.

Next steps

The researchers said longer follow-up is needed to determine if the effects of the Insight program are long-lasting. And there are still a number of other unanswered questions to be addressed in future research.

For one, it is unclear which method of delivering cognitive rehabilitation is better. A self-directed program such as this one may be suitable for some cancer survivors, while a group-based program may work better for others. It’s also unclear what the ideal duration and “dose” of cognitive training should be.

“If we could identify patients who are at risk of cognitive impairment, we could intervene earlier and possibly achieve even better results,” Dr Bray said. “We would also like to explore whether there is added benefit from combining cognitive training with physical exercise.” ![]()

Team maps genomic landscape of CBF-AML

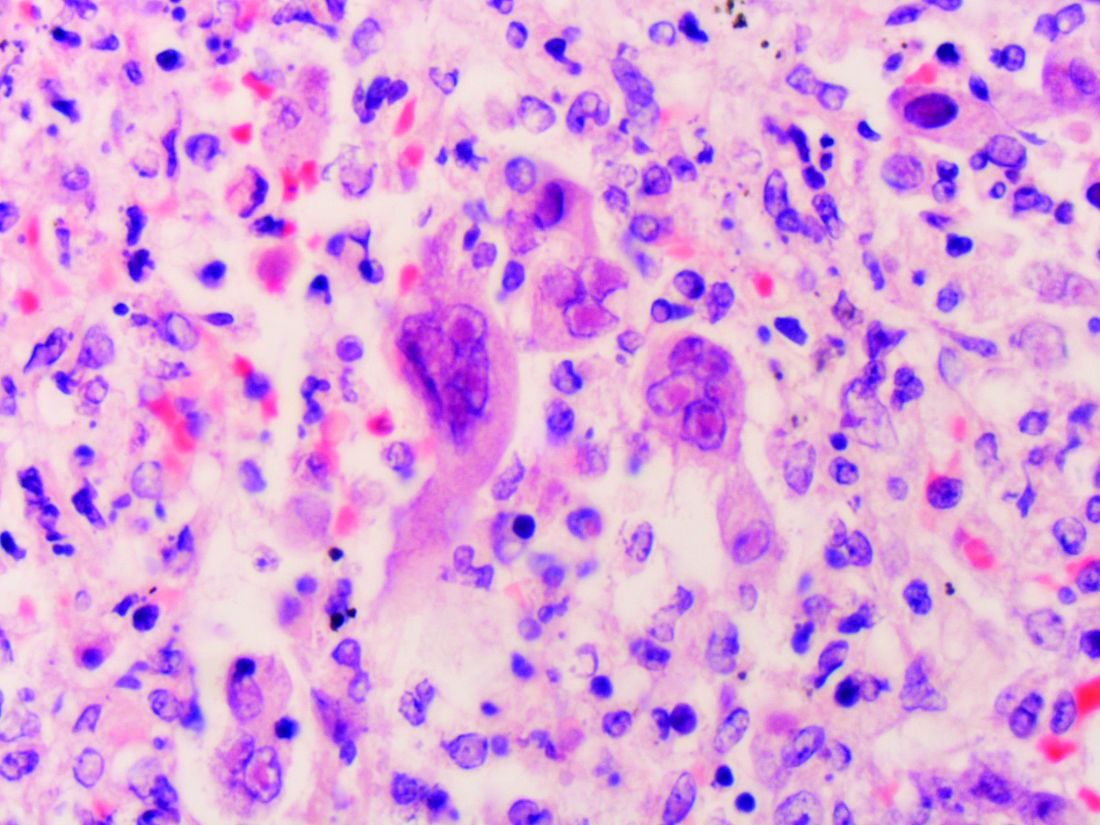

whole-genome sequencing

Photo courtesy of the US

Food and Drug Administration

Whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing has provided new insight into the pathogenesis and development of core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia (CBF-AML), according to researchers.

The team said their work has revealed “dramatic” differences in the genomic landscape of CBF-AMLs that contribute to the diversity of this disease.

The researchers reported their findings in Nature Genetics.

“We set out to understand the genetic variations that contribute to the development of CBF-AML using whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing,” said study author Jeffery Klco, MD, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

“Our goal was to define a detailed mutational landscape to understand better the genetic changes that contribute to disease.”

Dr Klco and his colleagues sequenced samples from 87 children and 78 adults with CBF-AML. Eighty-five of the patients had the RUNX1-RUNX1T1 subtype, and 80 had the CBFB-MYH11 subtype.

Development and relapse

The researchers identified several genes with mutations that may contribute to CBF-AML development, including CCND2, DHX15, ASXL2, ZBTB7A, and MGA.

“Many of the mutations we identified interfered with molecular signaling or epigenetic factors,” said study author Jinghui Zhang, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

“Some of the mutations, like ASXL2, are epigenetic regulators that modify the local state of chromatin,” Dr Klco noted. “Others, like ZBTB7A, appear to act like tumor suppressors.”

The researchers also compared mutations present at diagnosis and relapse in an attempt to understand how CBF-AML changes over time.

Their results suggested that KMT2C mutations are associated with relapse. Of the 4 patients in this study who had KMT2C mutations, 3 relapsed in less than 12 months, and the fourth had residual disease after a course of remission-induction therapy.

Similarities and differences

The researchers found a similar mutational landscape in adults and children with CBF-AML but differences between patients with the RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11 subtypes.

NRAS was the most frequently mutated gene in CBF-AMLs, but NRAS mutations were more common in CBFB-MYH11 AML than RUNX1-RUNX1T1 AML. The same was true for mutations in NF1 and WT1.

Patients with both subtypes of CBF-AML had mutations in NRAS, KIT, NF1, WT1, FLT3, KRAS, MGA, TTN, CCND2, KDM6A, PHIP, TET2, HCN1, KMT2C, and SETD2.

But only patients with CBFB-MYH11 AML had mutations in PTPN11.

Only patients with RUNX1-RUNX1T1 AML had mutations in ASXL2, ZBTB7A, EZH2, SMC1A, DHX15, RAD21, CBL, DNM2, CSF3R, GIGYF2, SMC3, and ZNF687.

The researchers said their findings suggest a range of mutations may play roles in CBF-AML, but additional research is needed to confirm their precise function in the disease.

Further studies are already underway to fully evaluate the contributions of the different genes as well as the roles of the newly identified genetic alterations in CBF-AML. ![]()

whole-genome sequencing

Photo courtesy of the US

Food and Drug Administration

Whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing has provided new insight into the pathogenesis and development of core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia (CBF-AML), according to researchers.

The team said their work has revealed “dramatic” differences in the genomic landscape of CBF-AMLs that contribute to the diversity of this disease.

The researchers reported their findings in Nature Genetics.

“We set out to understand the genetic variations that contribute to the development of CBF-AML using whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing,” said study author Jeffery Klco, MD, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

“Our goal was to define a detailed mutational landscape to understand better the genetic changes that contribute to disease.”

Dr Klco and his colleagues sequenced samples from 87 children and 78 adults with CBF-AML. Eighty-five of the patients had the RUNX1-RUNX1T1 subtype, and 80 had the CBFB-MYH11 subtype.

Development and relapse

The researchers identified several genes with mutations that may contribute to CBF-AML development, including CCND2, DHX15, ASXL2, ZBTB7A, and MGA.

“Many of the mutations we identified interfered with molecular signaling or epigenetic factors,” said study author Jinghui Zhang, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

“Some of the mutations, like ASXL2, are epigenetic regulators that modify the local state of chromatin,” Dr Klco noted. “Others, like ZBTB7A, appear to act like tumor suppressors.”

The researchers also compared mutations present at diagnosis and relapse in an attempt to understand how CBF-AML changes over time.

Their results suggested that KMT2C mutations are associated with relapse. Of the 4 patients in this study who had KMT2C mutations, 3 relapsed in less than 12 months, and the fourth had residual disease after a course of remission-induction therapy.

Similarities and differences

The researchers found a similar mutational landscape in adults and children with CBF-AML but differences between patients with the RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11 subtypes.

NRAS was the most frequently mutated gene in CBF-AMLs, but NRAS mutations were more common in CBFB-MYH11 AML than RUNX1-RUNX1T1 AML. The same was true for mutations in NF1 and WT1.

Patients with both subtypes of CBF-AML had mutations in NRAS, KIT, NF1, WT1, FLT3, KRAS, MGA, TTN, CCND2, KDM6A, PHIP, TET2, HCN1, KMT2C, and SETD2.

But only patients with CBFB-MYH11 AML had mutations in PTPN11.

Only patients with RUNX1-RUNX1T1 AML had mutations in ASXL2, ZBTB7A, EZH2, SMC1A, DHX15, RAD21, CBL, DNM2, CSF3R, GIGYF2, SMC3, and ZNF687.

The researchers said their findings suggest a range of mutations may play roles in CBF-AML, but additional research is needed to confirm their precise function in the disease.

Further studies are already underway to fully evaluate the contributions of the different genes as well as the roles of the newly identified genetic alterations in CBF-AML. ![]()

whole-genome sequencing

Photo courtesy of the US

Food and Drug Administration

Whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing has provided new insight into the pathogenesis and development of core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia (CBF-AML), according to researchers.

The team said their work has revealed “dramatic” differences in the genomic landscape of CBF-AMLs that contribute to the diversity of this disease.

The researchers reported their findings in Nature Genetics.

“We set out to understand the genetic variations that contribute to the development of CBF-AML using whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing,” said study author Jeffery Klco, MD, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

“Our goal was to define a detailed mutational landscape to understand better the genetic changes that contribute to disease.”

Dr Klco and his colleagues sequenced samples from 87 children and 78 adults with CBF-AML. Eighty-five of the patients had the RUNX1-RUNX1T1 subtype, and 80 had the CBFB-MYH11 subtype.

Development and relapse

The researchers identified several genes with mutations that may contribute to CBF-AML development, including CCND2, DHX15, ASXL2, ZBTB7A, and MGA.

“Many of the mutations we identified interfered with molecular signaling or epigenetic factors,” said study author Jinghui Zhang, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

“Some of the mutations, like ASXL2, are epigenetic regulators that modify the local state of chromatin,” Dr Klco noted. “Others, like ZBTB7A, appear to act like tumor suppressors.”

The researchers also compared mutations present at diagnosis and relapse in an attempt to understand how CBF-AML changes over time.

Their results suggested that KMT2C mutations are associated with relapse. Of the 4 patients in this study who had KMT2C mutations, 3 relapsed in less than 12 months, and the fourth had residual disease after a course of remission-induction therapy.

Similarities and differences

The researchers found a similar mutational landscape in adults and children with CBF-AML but differences between patients with the RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11 subtypes.

NRAS was the most frequently mutated gene in CBF-AMLs, but NRAS mutations were more common in CBFB-MYH11 AML than RUNX1-RUNX1T1 AML. The same was true for mutations in NF1 and WT1.

Patients with both subtypes of CBF-AML had mutations in NRAS, KIT, NF1, WT1, FLT3, KRAS, MGA, TTN, CCND2, KDM6A, PHIP, TET2, HCN1, KMT2C, and SETD2.

But only patients with CBFB-MYH11 AML had mutations in PTPN11.

Only patients with RUNX1-RUNX1T1 AML had mutations in ASXL2, ZBTB7A, EZH2, SMC1A, DHX15, RAD21, CBL, DNM2, CSF3R, GIGYF2, SMC3, and ZNF687.

The researchers said their findings suggest a range of mutations may play roles in CBF-AML, but additional research is needed to confirm their precise function in the disease.

Further studies are already underway to fully evaluate the contributions of the different genes as well as the roles of the newly identified genetic alterations in CBF-AML. ![]()

Continuous Rd should be standard of care, group says

Photo courtesy of Celgene

Updated trial results support continuous treatment with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Rd) as a standard of care for patients of all ages who have newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) and are ineligible for stem cell transplant, according to researchers.

In this phase 3 trial, patients who received continuous Rd (until disease progression) had better progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than patients who received 18 cycles of Rd (Rd18) or a combination of melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT).

Updated results from this study, known as the FIRST trial, were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Results were previously published in NEJM in 2014. The study was supported by Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome and Celgene Corporation, the makers of lenalidomide.

Thierry Facon, MD, of Centre Hospitalier Regional Universitaire de Lille in France, and his colleagues enrolled 1623 patients on this trial. They were newly diagnosed with MM and not eligible for stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive Rd in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), Rd18 for 72 weeks (n=541), or MPT for 72 weeks (n=547).

Response

In the intent-to-treat population, the overall response rate was 81% for the continuous Rd group, 79% for the Rd18 group, and 67% in the MPT group. The complete response rates were 21%, 20%, and 12%, respectively.

The median duration of response was 32 months (range, 26-37) in the continuous Rd group, 22 months (range, 19-23) in the Rd18 group, and 22 months (range, 20-25) in the MPT group.

PFS and OS

The median PFS was 26.0 months in the continuous Rd group, 21.0 months in the Rd18 group, and 21.9 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, the PFS rate was 33%, 14%, and 13%, respectively.

The hazard ratio (HR) for continuous Rd vs MPT was 0.69. The HR for continuous Rd vs Rd18 was 0.71. And the HR for Rd18 vs MPT was 0.99.

The median OS was 58.9 months in the continuous Rd group, 56.7 months in the Rd18 group, and 48.5 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, the OS rate was 60%, 57%, and 51%, respectively.

The HR for continuous Rd vs MPT was 0.75. The HR for continuous Rd vs Rd18 was 0.91. And the HR for Rd18 vs MPT was 0.83.

Safety

The most frequent grade 3/4 hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events were neutropenia and anemia. The rate of grade 3/4 neutropenia was higher in the MPT group than the continuous Rd or Rd18 groups.

Infections were the most common grade 3/4 non-hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events. The rate of grade 3/4 infections was higher in the Rd groups than the MPT group.

Grade 3/4 peripheral sensory neuropathy was less frequent in the continuous Rd and Rd18 groups than the MPT group.

The incidence of invasive second primary malignancy was 4% in the continuous Rd group, 6% in the Rd18 group, and 6% in the MPT group. ![]()

Photo courtesy of Celgene

Updated trial results support continuous treatment with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Rd) as a standard of care for patients of all ages who have newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) and are ineligible for stem cell transplant, according to researchers.

In this phase 3 trial, patients who received continuous Rd (until disease progression) had better progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than patients who received 18 cycles of Rd (Rd18) or a combination of melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT).

Updated results from this study, known as the FIRST trial, were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Results were previously published in NEJM in 2014. The study was supported by Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome and Celgene Corporation, the makers of lenalidomide.

Thierry Facon, MD, of Centre Hospitalier Regional Universitaire de Lille in France, and his colleagues enrolled 1623 patients on this trial. They were newly diagnosed with MM and not eligible for stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive Rd in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), Rd18 for 72 weeks (n=541), or MPT for 72 weeks (n=547).

Response

In the intent-to-treat population, the overall response rate was 81% for the continuous Rd group, 79% for the Rd18 group, and 67% in the MPT group. The complete response rates were 21%, 20%, and 12%, respectively.

The median duration of response was 32 months (range, 26-37) in the continuous Rd group, 22 months (range, 19-23) in the Rd18 group, and 22 months (range, 20-25) in the MPT group.

PFS and OS

The median PFS was 26.0 months in the continuous Rd group, 21.0 months in the Rd18 group, and 21.9 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, the PFS rate was 33%, 14%, and 13%, respectively.

The hazard ratio (HR) for continuous Rd vs MPT was 0.69. The HR for continuous Rd vs Rd18 was 0.71. And the HR for Rd18 vs MPT was 0.99.

The median OS was 58.9 months in the continuous Rd group, 56.7 months in the Rd18 group, and 48.5 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, the OS rate was 60%, 57%, and 51%, respectively.

The HR for continuous Rd vs MPT was 0.75. The HR for continuous Rd vs Rd18 was 0.91. And the HR for Rd18 vs MPT was 0.83.

Safety

The most frequent grade 3/4 hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events were neutropenia and anemia. The rate of grade 3/4 neutropenia was higher in the MPT group than the continuous Rd or Rd18 groups.

Infections were the most common grade 3/4 non-hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events. The rate of grade 3/4 infections was higher in the Rd groups than the MPT group.

Grade 3/4 peripheral sensory neuropathy was less frequent in the continuous Rd and Rd18 groups than the MPT group.

The incidence of invasive second primary malignancy was 4% in the continuous Rd group, 6% in the Rd18 group, and 6% in the MPT group. ![]()

Photo courtesy of Celgene

Updated trial results support continuous treatment with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Rd) as a standard of care for patients of all ages who have newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) and are ineligible for stem cell transplant, according to researchers.

In this phase 3 trial, patients who received continuous Rd (until disease progression) had better progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than patients who received 18 cycles of Rd (Rd18) or a combination of melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT).

Updated results from this study, known as the FIRST trial, were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Results were previously published in NEJM in 2014. The study was supported by Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome and Celgene Corporation, the makers of lenalidomide.

Thierry Facon, MD, of Centre Hospitalier Regional Universitaire de Lille in France, and his colleagues enrolled 1623 patients on this trial. They were newly diagnosed with MM and not eligible for stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive Rd in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), Rd18 for 72 weeks (n=541), or MPT for 72 weeks (n=547).

Response

In the intent-to-treat population, the overall response rate was 81% for the continuous Rd group, 79% for the Rd18 group, and 67% in the MPT group. The complete response rates were 21%, 20%, and 12%, respectively.

The median duration of response was 32 months (range, 26-37) in the continuous Rd group, 22 months (range, 19-23) in the Rd18 group, and 22 months (range, 20-25) in the MPT group.

PFS and OS

The median PFS was 26.0 months in the continuous Rd group, 21.0 months in the Rd18 group, and 21.9 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, the PFS rate was 33%, 14%, and 13%, respectively.

The hazard ratio (HR) for continuous Rd vs MPT was 0.69. The HR for continuous Rd vs Rd18 was 0.71. And the HR for Rd18 vs MPT was 0.99.

The median OS was 58.9 months in the continuous Rd group, 56.7 months in the Rd18 group, and 48.5 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, the OS rate was 60%, 57%, and 51%, respectively.

The HR for continuous Rd vs MPT was 0.75. The HR for continuous Rd vs Rd18 was 0.91. And the HR for Rd18 vs MPT was 0.83.

Safety

The most frequent grade 3/4 hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events were neutropenia and anemia. The rate of grade 3/4 neutropenia was higher in the MPT group than the continuous Rd or Rd18 groups.

Infections were the most common grade 3/4 non-hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events. The rate of grade 3/4 infections was higher in the Rd groups than the MPT group.

Grade 3/4 peripheral sensory neuropathy was less frequent in the continuous Rd and Rd18 groups than the MPT group.

The incidence of invasive second primary malignancy was 4% in the continuous Rd group, 6% in the Rd18 group, and 6% in the MPT group. ![]()

Results support continued study of CMV vaccine

CMV infection

A vaccine designed to control cytomegalovirus (CMV) has produced favorable results in a phase 1 trial of healthy volunteers.

Investigators said the vaccine, known as Triplex, was well-tolerated at multiple dose levels.

The vaccine also generated “robust” and “durable” virus-specific immunity in subjects who were previously infected with CMV and those who were not.

The results of this study were published in Blood.

Triplex is a universal (non-HLA-restricted), recombinant modified vaccinia ankara viral vector vaccine engineered to induce a virus-specific T-cell response to 3 immuno-dominant proteins (UL83 [pp65], UL123 [IE1], and UL122 [IE2]) linked to CMV complications in the post-transplant setting.

Helocyte Inc. is developing the vaccine for control of CMV in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and solid organ transplant.

This study was not funded by Helocyte. However, investigator Don J. Diamond, PhD, of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, California is chair of Helocyte’s scientific advisory board and receives personal service fees from the company.

In this trial, Dr Diamond and his colleagues studied the response to Triplex in 24 healthy volunteers.

Subjects were divided into 3 groups of 8 receiving 3 different doses of the vaccine. The first dose level was 10xE7 plaque-forming units (pfu), the second was 5x10E7 pfu, and the third was 5x10E8 pfu.

The subjects received the vaccine in a volume of 1 mL by intramuscular injection in the upper arm and an identical booster injection 28 days later.

Safety

The investigators said Triplex was well tolerated in most subjects at all dose levels. There were no dose-limiting toxicities and no serious adverse events attributed to the vaccine.

One subject experienced a grade 3 injection site adverse event (erythema), which resolved in 1 day without treatment. In addition, there were 3 mild-to-moderate cutaneous reactions.

The investigators said the most common systemic reaction was mild-to-moderate flu-like symptoms. Most subjects in the highest dose group experienced these symptoms, as did a few subjects from the lower dose groups. All of these events were transient, self-limiting, and resolved.

Immunogenicity

The investigators reported “robust, functional, and durable” expansion of CMV-specific T cells after Triplex vaccination, in subjects with and without prior CMV infection.

At day 42, subjects had experienced a significant increase in pp65-specific T cells from baseline. The P values were 0.0003 for pp65-specific CD137+ CD8+ T cells and 0.001 for CD137+ CD4+ T cells.

Expansion remained above baseline levels until at least day 360 for pp65-specific CD137+ CD8+ T cells and at least until day 482 for pp65-specific CD137+ CD4+ T cells.

IE1-exon4- and IE2-exon5-specific T-cell expansions occurred as well, although the increase from baseline was not significant for IE1-exon4-specific T cells.

The median concentrations of IE2-exon5-specific T cells had increased significantly from baseline at day 42—for both CD137+ CD8+ T cells (P=0.014) and CD137+ CD4+ T cells (P=0.003).

The investigators noted that there was no significant difference in the responses to all 3 CMV libraries according to Triplex dose level, previous smallpox vaccination, or CMV-serostatus.

Next, the team found that Triplex vaccination induced significant expansion of pp65-specific IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells. They said this suggests the vaccine was able to expand a functional subset of CMV-specific T cells, even in the absence of CMV viremia.

The median concentration of pp65-specific IFN-γ + CD8+ T cells increased significantly from baseline to day 28 (P=0.024), day 56 (P=0.003), day 100 (P=0.011), and day 360 (P=0.085).

There was no significant increase for pp65-specific IFN-γ + CD4+ T cells, IE1-exon4-specific IFN-γ+ T cells, or IE2-exon5-specific IFN-γ + T cells.

The investigators also said the Triplex vaccine induced significant vaccinia-specific T-cell increases by day 42 (P=0.0005), with an estimated decline to pre-vaccination levels at day 274.

These data supported the initiation of an ongoing phase 2 trial in which investigators are evaluating Triplex in patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT (NCT02506933).

“After years of work, it is very gratifying that we are making advancements in helping people worldwide achieve better health outcomes after a transplant procedure,” said Dr Diamond, who led the team that developed Triplex.

“Furthermore, Triplex’s favorable safety and immunogenicity may make the vaccine an ideal therapeutic platform to combat significant complications in many disease areas, like solid organ transplant and glioblastoma.” ![]()

CMV infection

A vaccine designed to control cytomegalovirus (CMV) has produced favorable results in a phase 1 trial of healthy volunteers.

Investigators said the vaccine, known as Triplex, was well-tolerated at multiple dose levels.

The vaccine also generated “robust” and “durable” virus-specific immunity in subjects who were previously infected with CMV and those who were not.

The results of this study were published in Blood.

Triplex is a universal (non-HLA-restricted), recombinant modified vaccinia ankara viral vector vaccine engineered to induce a virus-specific T-cell response to 3 immuno-dominant proteins (UL83 [pp65], UL123 [IE1], and UL122 [IE2]) linked to CMV complications in the post-transplant setting.

Helocyte Inc. is developing the vaccine for control of CMV in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and solid organ transplant.

This study was not funded by Helocyte. However, investigator Don J. Diamond, PhD, of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, California is chair of Helocyte’s scientific advisory board and receives personal service fees from the company.

In this trial, Dr Diamond and his colleagues studied the response to Triplex in 24 healthy volunteers.

Subjects were divided into 3 groups of 8 receiving 3 different doses of the vaccine. The first dose level was 10xE7 plaque-forming units (pfu), the second was 5x10E7 pfu, and the third was 5x10E8 pfu.

The subjects received the vaccine in a volume of 1 mL by intramuscular injection in the upper arm and an identical booster injection 28 days later.

Safety

The investigators said Triplex was well tolerated in most subjects at all dose levels. There were no dose-limiting toxicities and no serious adverse events attributed to the vaccine.

One subject experienced a grade 3 injection site adverse event (erythema), which resolved in 1 day without treatment. In addition, there were 3 mild-to-moderate cutaneous reactions.

The investigators said the most common systemic reaction was mild-to-moderate flu-like symptoms. Most subjects in the highest dose group experienced these symptoms, as did a few subjects from the lower dose groups. All of these events were transient, self-limiting, and resolved.

Immunogenicity

The investigators reported “robust, functional, and durable” expansion of CMV-specific T cells after Triplex vaccination, in subjects with and without prior CMV infection.

At day 42, subjects had experienced a significant increase in pp65-specific T cells from baseline. The P values were 0.0003 for pp65-specific CD137+ CD8+ T cells and 0.001 for CD137+ CD4+ T cells.

Expansion remained above baseline levels until at least day 360 for pp65-specific CD137+ CD8+ T cells and at least until day 482 for pp65-specific CD137+ CD4+ T cells.

IE1-exon4- and IE2-exon5-specific T-cell expansions occurred as well, although the increase from baseline was not significant for IE1-exon4-specific T cells.

The median concentrations of IE2-exon5-specific T cells had increased significantly from baseline at day 42—for both CD137+ CD8+ T cells (P=0.014) and CD137+ CD4+ T cells (P=0.003).

The investigators noted that there was no significant difference in the responses to all 3 CMV libraries according to Triplex dose level, previous smallpox vaccination, or CMV-serostatus.

Next, the team found that Triplex vaccination induced significant expansion of pp65-specific IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells. They said this suggests the vaccine was able to expand a functional subset of CMV-specific T cells, even in the absence of CMV viremia.

The median concentration of pp65-specific IFN-γ + CD8+ T cells increased significantly from baseline to day 28 (P=0.024), day 56 (P=0.003), day 100 (P=0.011), and day 360 (P=0.085).

There was no significant increase for pp65-specific IFN-γ + CD4+ T cells, IE1-exon4-specific IFN-γ+ T cells, or IE2-exon5-specific IFN-γ + T cells.

The investigators also said the Triplex vaccine induced significant vaccinia-specific T-cell increases by day 42 (P=0.0005), with an estimated decline to pre-vaccination levels at day 274.

These data supported the initiation of an ongoing phase 2 trial in which investigators are evaluating Triplex in patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT (NCT02506933).

“After years of work, it is very gratifying that we are making advancements in helping people worldwide achieve better health outcomes after a transplant procedure,” said Dr Diamond, who led the team that developed Triplex.

“Furthermore, Triplex’s favorable safety and immunogenicity may make the vaccine an ideal therapeutic platform to combat significant complications in many disease areas, like solid organ transplant and glioblastoma.” ![]()

CMV infection

A vaccine designed to control cytomegalovirus (CMV) has produced favorable results in a phase 1 trial of healthy volunteers.

Investigators said the vaccine, known as Triplex, was well-tolerated at multiple dose levels.

The vaccine also generated “robust” and “durable” virus-specific immunity in subjects who were previously infected with CMV and those who were not.

The results of this study were published in Blood.

Triplex is a universal (non-HLA-restricted), recombinant modified vaccinia ankara viral vector vaccine engineered to induce a virus-specific T-cell response to 3 immuno-dominant proteins (UL83 [pp65], UL123 [IE1], and UL122 [IE2]) linked to CMV complications in the post-transplant setting.

Helocyte Inc. is developing the vaccine for control of CMV in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and solid organ transplant.

This study was not funded by Helocyte. However, investigator Don J. Diamond, PhD, of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, California is chair of Helocyte’s scientific advisory board and receives personal service fees from the company.

In this trial, Dr Diamond and his colleagues studied the response to Triplex in 24 healthy volunteers.

Subjects were divided into 3 groups of 8 receiving 3 different doses of the vaccine. The first dose level was 10xE7 plaque-forming units (pfu), the second was 5x10E7 pfu, and the third was 5x10E8 pfu.

The subjects received the vaccine in a volume of 1 mL by intramuscular injection in the upper arm and an identical booster injection 28 days later.

Safety

The investigators said Triplex was well tolerated in most subjects at all dose levels. There were no dose-limiting toxicities and no serious adverse events attributed to the vaccine.

One subject experienced a grade 3 injection site adverse event (erythema), which resolved in 1 day without treatment. In addition, there were 3 mild-to-moderate cutaneous reactions.

The investigators said the most common systemic reaction was mild-to-moderate flu-like symptoms. Most subjects in the highest dose group experienced these symptoms, as did a few subjects from the lower dose groups. All of these events were transient, self-limiting, and resolved.

Immunogenicity

The investigators reported “robust, functional, and durable” expansion of CMV-specific T cells after Triplex vaccination, in subjects with and without prior CMV infection.

At day 42, subjects had experienced a significant increase in pp65-specific T cells from baseline. The P values were 0.0003 for pp65-specific CD137+ CD8+ T cells and 0.001 for CD137+ CD4+ T cells.

Expansion remained above baseline levels until at least day 360 for pp65-specific CD137+ CD8+ T cells and at least until day 482 for pp65-specific CD137+ CD4+ T cells.

IE1-exon4- and IE2-exon5-specific T-cell expansions occurred as well, although the increase from baseline was not significant for IE1-exon4-specific T cells.

The median concentrations of IE2-exon5-specific T cells had increased significantly from baseline at day 42—for both CD137+ CD8+ T cells (P=0.014) and CD137+ CD4+ T cells (P=0.003).

The investigators noted that there was no significant difference in the responses to all 3 CMV libraries according to Triplex dose level, previous smallpox vaccination, or CMV-serostatus.

Next, the team found that Triplex vaccination induced significant expansion of pp65-specific IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells. They said this suggests the vaccine was able to expand a functional subset of CMV-specific T cells, even in the absence of CMV viremia.

The median concentration of pp65-specific IFN-γ + CD8+ T cells increased significantly from baseline to day 28 (P=0.024), day 56 (P=0.003), day 100 (P=0.011), and day 360 (P=0.085).

There was no significant increase for pp65-specific IFN-γ + CD4+ T cells, IE1-exon4-specific IFN-γ+ T cells, or IE2-exon5-specific IFN-γ + T cells.

The investigators also said the Triplex vaccine induced significant vaccinia-specific T-cell increases by day 42 (P=0.0005), with an estimated decline to pre-vaccination levels at day 274.

These data supported the initiation of an ongoing phase 2 trial in which investigators are evaluating Triplex in patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT (NCT02506933).

“After years of work, it is very gratifying that we are making advancements in helping people worldwide achieve better health outcomes after a transplant procedure,” said Dr Diamond, who led the team that developed Triplex.

“Furthermore, Triplex’s favorable safety and immunogenicity may make the vaccine an ideal therapeutic platform to combat significant complications in many disease areas, like solid organ transplant and glioblastoma.” ![]()

A girl repeatedly jabs her finger up her nose: Compulsion or self-injury?

CASE Anxious and self-injurious

A, age 6, is forcibly inserting her finger into her nose repeatedly until she bleeds profusely, as many as 20 times per day. She is not nose-picking but is jabbing her finger into her nose as far as possible in a repetitive ramming motion. Less frequently, she inserts her finger into her vagina, resulting in chronic urinary tract infections (UTIs). She has bedtime checking rituals; worries that her parents will die; has a fear of vomiting to the point where she stopped eating normally and lost 5 lb in 6 months; intense fear of storms; refusal to use public bathrooms; and involuntary throat clearing, facial grimacing, and lip twitches.

A’s symptoms began at age 3. There is no history of physical or sexual abuse. She does well in school, but these behaviors have had a significant impact on her social functioning. She is not taking any medications and has been in weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for the last year. A has had several UTIs but otherwise is physically healthy.

Which diagnosis best describes A’s condition?

a) non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)

b) generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

c) obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

d) Tourette’s disorder (TD)

The authors’ observations

A is causing herself to bleed and says she wants to stop this behavior. Onset of NSSI typically is age 12 to 14 and could be accompanied by traits of cluster B personality disorders.1 In A’s case, her age and absence of any stated desire to relieve stress or intense negative affective states rules out NSSI.

Because A has multiple and frequent fears, worries, and anxieties that have been present for years and have caused significant functional impairment, a diagnosis of GAD is warranted. Because she has had both motor and vocal tics for more than 1 year, she also meets diagnostic criteria for TD (Table 1).

In young children, OCD manifests primarily with compulsive behavior, such as excessive hand washing, counting, and ordering, that interferes with functioning. Although A has bedtime checking rituals, she has no significant functional impairment from these rituals alone. A’s finger-insertion behavior could be interpreted as a complex motor tic or as a compulsion, in which case impairment was significant enough to justify a diagnosis of OCD.

Many individuals with OCD report the need to engage in compulsive behavior to decrease anxiety or until they experience a “just right” feeling.2 However, neither A nor her mother reported the need for the “just right” feeling. The child recognized the urge to put her finger in her nose and did experience relief of anxiety after drawing blood. Although A said that she was unable to control her hands, she was observed frequently touching the side of her nose in an attempt to avoid inserting her finger in her nose.

Compulsive behavior that results in self-injury typically is not seen in OCD except in children with severe neurologic complications, low intellectual functioning, psychosis, or autism.3

It often is difficult to determine if complex motor or vocal tics are compulsions (Table 2). Indeed, the same biologic mechanisms are thought to be implicated in TD and OCD.4 A significant percentage of children with OCD have tics, and patients often report that they are unable to distinguish between compulsions and complex tics.5 Therefore, we thought that a reasonable differential included both TD and OCD, but more careful assessment over time was required.

Treatment options

A has been receiving CBT for more than 1 year but her symptoms were worsening, which prompted her parents to seek evaluation in our clinic. Because of the level of interference with daily functioning and significant distress, our priority was developing a treatment plan that has the best chance of quickly reducing symptom severity and frequency. The results of the large-scale Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS), which evaluated children age 7 to 17, and the Child/Adolescent Multimodal Anxiety Study, which evaluated children age <12, indicated that the combination of CBT with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) reduced OCD symptoms more than either modality alone.6,7 Considerations for using SSRIs in this age group include:

- the risk of behavioral activation

- poor tolerability

- lack of an evidence base for dosage optimization.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry’s Preschool Psychopharmacology Working Group’s guidelines for treating anxiety in preschoolers state that pharmacotherapeutic intervention can be considered when symptoms are intolerable and adequate psychotherapy interventions have been tried.8 In A’s case, she had been receiving CBT for a year without improvement in symptoms; therefore, initiating medication was indicated, as well as an examination of therapeutic modalities being used.

Treatment Next steps

A is started on liquid fluoxetine, 20 mg/5 mL, 1 mL (4 mg) daily, because of her inability to swallow pills and her young age. According to her mother, a week later A is sleeping better and seems happier. The entire family seems less stressed. During the third week, A successfully goes on a camping trip with her family and is starting to eat better. Her finger-in-nose insertions still are occurring but, according to her mother, she is not putting her finger in her vagina. In session, she is not observed putting her finger in her nose or touching her nose, which she had done frequently during the initial evaluation. Fluoxetine seems to be well tolerated and the dosage is increased to 2 mL (8 mg) per day.

Although A has weekly scheduled appointments, she is not brought in again until a month later. At that time her mother reports an approximately 40% improvement in overall symptoms, including less frequent nose-insertion behaviors.

What type of psychotherapy would you employ for A?

a) CBT

b) behavioral therapy

c) habit reversal training (HRT)

d) pharmacotherapy alone

The authors’ observations

The treatment team planned to begin psychotherapy after A showed a decrease in anxiety and frequency of problem behaviors to a point where she could benefit. Evidence-based treatment for compulsions and tics is CBT and/or HRT.9 However, clinicians frequently encounter special challenges in helping young children (age 5 to 8) who have OCD. Factors such as family functioning, parental accommodation to the child’s symptoms, and the child’s ability to understand symptoms, exposure and response prevention, and willingness to tolerate discomfort should be considered if treatment is to be effective.

Research has shown that including parents when treating anxious children—especially young children—can facilitate gains and hasten positive outcomes.10,11 The POTS Jr study showed the relative efficacy of a family-based CBT model for young children with OCD that emphasizes consistent involvement of parents in all phases of treatment.12 In this case, A and her mother were seen together for psychotherapy, with an initial focus on learning more about the antecedents and consequences of the child’s behaviors.

OUTCOME Inconsistencies

Treatment was initiated during the summer. With the upcoming start of the school year, A begins to complain of daily headache, stomachache, and anxiety related to the start of school. Fluoxetine is increased to 3 mL/d (12 mg/d). After school starts, her mother stops going to work and begins attending school daily with A to relieve both her and the child’s anxiety.

The following week, the mother pages the psychiatrist, hysterical and crying because she thought the child was “pulling her hair out so much she looks like a cancer survivor.” Both parents blame the increase in fluoxetine for the heightened anxiety. At the next visit, the treatment team does not notice any evidence of unusual hair loss on the child. A has not attended school for several weeks, and her mother has not returned to work. Her parents report that the finger-to-nose behavior has increased, although it is not observed during the session, and fluoxetine is tapered as her parents requested.

At the next session, her mother notes a significant increase in finger-to-nose behavior and requests that the child be put back on fluoxetine, saying, “I would give anything to have the child I had on Prozac back.”

How would you proceed?

a) confront the mother’s inconsistencies

b) restart fluoxetine and continue psychotherapy

c) refer A to another clinic or therapist

d) refer A to inpatient care

The authors’ observations

The treatment team identified several barriers to successful treatment in our clinic. The level of functional interference caused by A’s symptoms indicated sessions more often than once a week, but the parents felt that the distance from our clinic to their home made this too difficult. The mother’s anxiety and obvious distress over her daughter’s symptoms precluded working closely with child. Parental anxiety is correlated with the child’s anxiety and can moderate treatment outcome.11 In response to the suffering of their anxious children, especially young ones, parents often will become anxious and accommodate to the child’s symptoms, which we strongly suspected was happening with A’s mother.

Parents’ concerns about A’s symptoms and response to treatment were addressed during a family meeting. Recognizing that the level of care needed by this family was higher than could be provided in our clinic, we recommended referral to a specialty clinic. A was brought to another clinic, and treatment at our facility was terminated.

1. Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: a review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(2):226-239.

2. Miguel EC, do Rosário-Campos MC, Prado HS, et al. Sensory phenomena in obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette’s disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):150-156.

3. Nock MK, Favazza A. Non-suicidal self-injury: definition and classification. In: Nock MK, ed. Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: origins, assessment, and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009:9-18.

4. Goodman WK, Storch EA, Geffken GR, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in Tourette syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):704-714.

5. Garcia AM, Freeman JB, Himle MB, et al. Phenomenology of early childhood onset obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2009;31(2):104-111.

6. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

7. Piacentini JC, Bennett S, Compton SN, et al. 24- and 36-week outcomes for the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(3):297-310.

8. Gleason MM, Egger HL, Emslie GJ, et al. Psychopharmacological treatment for very young children: contexts and guidelines. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(12):1532-1572.

9. Abramowitz JS, Whiteside SP, Deacon BJ. The effectiveness of treatment for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36(1):55-63.

10. Barmish AJ, Kendall PC. Should parents be co-clients in cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34(3):569-581.

11. Drake KL, Ginsburg GS. Family factors in the development, treatment, and prevention of childhood anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2012;15(2):144-162.

12. Freeman J, Sapyta J, Garcia A, et al. Family-based treatment of early childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Treatment Study for Young Children (POTS Jr)—a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(6):689-698.

CASE Anxious and self-injurious

A, age 6, is forcibly inserting her finger into her nose repeatedly until she bleeds profusely, as many as 20 times per day. She is not nose-picking but is jabbing her finger into her nose as far as possible in a repetitive ramming motion. Less frequently, she inserts her finger into her vagina, resulting in chronic urinary tract infections (UTIs). She has bedtime checking rituals; worries that her parents will die; has a fear of vomiting to the point where she stopped eating normally and lost 5 lb in 6 months; intense fear of storms; refusal to use public bathrooms; and involuntary throat clearing, facial grimacing, and lip twitches.

A’s symptoms began at age 3. There is no history of physical or sexual abuse. She does well in school, but these behaviors have had a significant impact on her social functioning. She is not taking any medications and has been in weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for the last year. A has had several UTIs but otherwise is physically healthy.

Which diagnosis best describes A’s condition?

a) non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)

b) generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

c) obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

d) Tourette’s disorder (TD)

The authors’ observations

A is causing herself to bleed and says she wants to stop this behavior. Onset of NSSI typically is age 12 to 14 and could be accompanied by traits of cluster B personality disorders.1 In A’s case, her age and absence of any stated desire to relieve stress or intense negative affective states rules out NSSI.

Because A has multiple and frequent fears, worries, and anxieties that have been present for years and have caused significant functional impairment, a diagnosis of GAD is warranted. Because she has had both motor and vocal tics for more than 1 year, she also meets diagnostic criteria for TD (Table 1).

In young children, OCD manifests primarily with compulsive behavior, such as excessive hand washing, counting, and ordering, that interferes with functioning. Although A has bedtime checking rituals, she has no significant functional impairment from these rituals alone. A’s finger-insertion behavior could be interpreted as a complex motor tic or as a compulsion, in which case impairment was significant enough to justify a diagnosis of OCD.

Many individuals with OCD report the need to engage in compulsive behavior to decrease anxiety or until they experience a “just right” feeling.2 However, neither A nor her mother reported the need for the “just right” feeling. The child recognized the urge to put her finger in her nose and did experience relief of anxiety after drawing blood. Although A said that she was unable to control her hands, she was observed frequently touching the side of her nose in an attempt to avoid inserting her finger in her nose.

Compulsive behavior that results in self-injury typically is not seen in OCD except in children with severe neurologic complications, low intellectual functioning, psychosis, or autism.3

It often is difficult to determine if complex motor or vocal tics are compulsions (Table 2). Indeed, the same biologic mechanisms are thought to be implicated in TD and OCD.4 A significant percentage of children with OCD have tics, and patients often report that they are unable to distinguish between compulsions and complex tics.5 Therefore, we thought that a reasonable differential included both TD and OCD, but more careful assessment over time was required.

Treatment options

A has been receiving CBT for more than 1 year but her symptoms were worsening, which prompted her parents to seek evaluation in our clinic. Because of the level of interference with daily functioning and significant distress, our priority was developing a treatment plan that has the best chance of quickly reducing symptom severity and frequency. The results of the large-scale Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS), which evaluated children age 7 to 17, and the Child/Adolescent Multimodal Anxiety Study, which evaluated children age <12, indicated that the combination of CBT with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) reduced OCD symptoms more than either modality alone.6,7 Considerations for using SSRIs in this age group include:

- the risk of behavioral activation

- poor tolerability

- lack of an evidence base for dosage optimization.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry’s Preschool Psychopharmacology Working Group’s guidelines for treating anxiety in preschoolers state that pharmacotherapeutic intervention can be considered when symptoms are intolerable and adequate psychotherapy interventions have been tried.8 In A’s case, she had been receiving CBT for a year without improvement in symptoms; therefore, initiating medication was indicated, as well as an examination of therapeutic modalities being used.

Treatment Next steps

A is started on liquid fluoxetine, 20 mg/5 mL, 1 mL (4 mg) daily, because of her inability to swallow pills and her young age. According to her mother, a week later A is sleeping better and seems happier. The entire family seems less stressed. During the third week, A successfully goes on a camping trip with her family and is starting to eat better. Her finger-in-nose insertions still are occurring but, according to her mother, she is not putting her finger in her vagina. In session, she is not observed putting her finger in her nose or touching her nose, which she had done frequently during the initial evaluation. Fluoxetine seems to be well tolerated and the dosage is increased to 2 mL (8 mg) per day.

Although A has weekly scheduled appointments, she is not brought in again until a month later. At that time her mother reports an approximately 40% improvement in overall symptoms, including less frequent nose-insertion behaviors.

What type of psychotherapy would you employ for A?

a) CBT

b) behavioral therapy

c) habit reversal training (HRT)

d) pharmacotherapy alone

The authors’ observations

The treatment team planned to begin psychotherapy after A showed a decrease in anxiety and frequency of problem behaviors to a point where she could benefit. Evidence-based treatment for compulsions and tics is CBT and/or HRT.9 However, clinicians frequently encounter special challenges in helping young children (age 5 to 8) who have OCD. Factors such as family functioning, parental accommodation to the child’s symptoms, and the child’s ability to understand symptoms, exposure and response prevention, and willingness to tolerate discomfort should be considered if treatment is to be effective.

Research has shown that including parents when treating anxious children—especially young children—can facilitate gains and hasten positive outcomes.10,11 The POTS Jr study showed the relative efficacy of a family-based CBT model for young children with OCD that emphasizes consistent involvement of parents in all phases of treatment.12 In this case, A and her mother were seen together for psychotherapy, with an initial focus on learning more about the antecedents and consequences of the child’s behaviors.

OUTCOME Inconsistencies

Treatment was initiated during the summer. With the upcoming start of the school year, A begins to complain of daily headache, stomachache, and anxiety related to the start of school. Fluoxetine is increased to 3 mL/d (12 mg/d). After school starts, her mother stops going to work and begins attending school daily with A to relieve both her and the child’s anxiety.

The following week, the mother pages the psychiatrist, hysterical and crying because she thought the child was “pulling her hair out so much she looks like a cancer survivor.” Both parents blame the increase in fluoxetine for the heightened anxiety. At the next visit, the treatment team does not notice any evidence of unusual hair loss on the child. A has not attended school for several weeks, and her mother has not returned to work. Her parents report that the finger-to-nose behavior has increased, although it is not observed during the session, and fluoxetine is tapered as her parents requested.

At the next session, her mother notes a significant increase in finger-to-nose behavior and requests that the child be put back on fluoxetine, saying, “I would give anything to have the child I had on Prozac back.”

How would you proceed?

a) confront the mother’s inconsistencies

b) restart fluoxetine and continue psychotherapy

c) refer A to another clinic or therapist

d) refer A to inpatient care

The authors’ observations

The treatment team identified several barriers to successful treatment in our clinic. The level of functional interference caused by A’s symptoms indicated sessions more often than once a week, but the parents felt that the distance from our clinic to their home made this too difficult. The mother’s anxiety and obvious distress over her daughter’s symptoms precluded working closely with child. Parental anxiety is correlated with the child’s anxiety and can moderate treatment outcome.11 In response to the suffering of their anxious children, especially young ones, parents often will become anxious and accommodate to the child’s symptoms, which we strongly suspected was happening with A’s mother.

Parents’ concerns about A’s symptoms and response to treatment were addressed during a family meeting. Recognizing that the level of care needed by this family was higher than could be provided in our clinic, we recommended referral to a specialty clinic. A was brought to another clinic, and treatment at our facility was terminated.

CASE Anxious and self-injurious

A, age 6, is forcibly inserting her finger into her nose repeatedly until she bleeds profusely, as many as 20 times per day. She is not nose-picking but is jabbing her finger into her nose as far as possible in a repetitive ramming motion. Less frequently, she inserts her finger into her vagina, resulting in chronic urinary tract infections (UTIs). She has bedtime checking rituals; worries that her parents will die; has a fear of vomiting to the point where she stopped eating normally and lost 5 lb in 6 months; intense fear of storms; refusal to use public bathrooms; and involuntary throat clearing, facial grimacing, and lip twitches.

A’s symptoms began at age 3. There is no history of physical or sexual abuse. She does well in school, but these behaviors have had a significant impact on her social functioning. She is not taking any medications and has been in weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for the last year. A has had several UTIs but otherwise is physically healthy.

Which diagnosis best describes A’s condition?

a) non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)

b) generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

c) obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

d) Tourette’s disorder (TD)

The authors’ observations

A is causing herself to bleed and says she wants to stop this behavior. Onset of NSSI typically is age 12 to 14 and could be accompanied by traits of cluster B personality disorders.1 In A’s case, her age and absence of any stated desire to relieve stress or intense negative affective states rules out NSSI.

Because A has multiple and frequent fears, worries, and anxieties that have been present for years and have caused significant functional impairment, a diagnosis of GAD is warranted. Because she has had both motor and vocal tics for more than 1 year, she also meets diagnostic criteria for TD (Table 1).

In young children, OCD manifests primarily with compulsive behavior, such as excessive hand washing, counting, and ordering, that interferes with functioning. Although A has bedtime checking rituals, she has no significant functional impairment from these rituals alone. A’s finger-insertion behavior could be interpreted as a complex motor tic or as a compulsion, in which case impairment was significant enough to justify a diagnosis of OCD.

Many individuals with OCD report the need to engage in compulsive behavior to decrease anxiety or until they experience a “just right” feeling.2 However, neither A nor her mother reported the need for the “just right” feeling. The child recognized the urge to put her finger in her nose and did experience relief of anxiety after drawing blood. Although A said that she was unable to control her hands, she was observed frequently touching the side of her nose in an attempt to avoid inserting her finger in her nose.

Compulsive behavior that results in self-injury typically is not seen in OCD except in children with severe neurologic complications, low intellectual functioning, psychosis, or autism.3

It often is difficult to determine if complex motor or vocal tics are compulsions (Table 2). Indeed, the same biologic mechanisms are thought to be implicated in TD and OCD.4 A significant percentage of children with OCD have tics, and patients often report that they are unable to distinguish between compulsions and complex tics.5 Therefore, we thought that a reasonable differential included both TD and OCD, but more careful assessment over time was required.

Treatment options