User login

United States nears 3,000 Zika-infected pregnancies

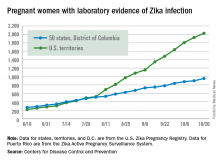

There were 54 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus in the 50 states and the District of Columbia reported during the week ending Oct. 20 – the largest weekly increase in a month, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of cases reported in the U.S. territories, 100, was lower for the second week in a row, however, so the U.S. total for the week was a fairly average 154. The total number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection is now 2,980 for the year: 953 in the states/D.C. and 2,027 in the territories, the CDC reported.

Among all Americans, the number of cases for 2015-2016 is now up to 32,814, with 1,396 new cases reported for the week ending Oct. 26: 75 in the states/D.C. and 1,321 in the territories. Almost all (98%) of the territorial cases have occurred in Puerto Rico, which continues to retroactively report cases, the CDC Arboviral Disease Branch noted.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The pregnancy-related figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

There were 54 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus in the 50 states and the District of Columbia reported during the week ending Oct. 20 – the largest weekly increase in a month, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of cases reported in the U.S. territories, 100, was lower for the second week in a row, however, so the U.S. total for the week was a fairly average 154. The total number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection is now 2,980 for the year: 953 in the states/D.C. and 2,027 in the territories, the CDC reported.

Among all Americans, the number of cases for 2015-2016 is now up to 32,814, with 1,396 new cases reported for the week ending Oct. 26: 75 in the states/D.C. and 1,321 in the territories. Almost all (98%) of the territorial cases have occurred in Puerto Rico, which continues to retroactively report cases, the CDC Arboviral Disease Branch noted.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The pregnancy-related figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

There were 54 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus in the 50 states and the District of Columbia reported during the week ending Oct. 20 – the largest weekly increase in a month, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of cases reported in the U.S. territories, 100, was lower for the second week in a row, however, so the U.S. total for the week was a fairly average 154. The total number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection is now 2,980 for the year: 953 in the states/D.C. and 2,027 in the territories, the CDC reported.

Among all Americans, the number of cases for 2015-2016 is now up to 32,814, with 1,396 new cases reported for the week ending Oct. 26: 75 in the states/D.C. and 1,321 in the territories. Almost all (98%) of the territorial cases have occurred in Puerto Rico, which continues to retroactively report cases, the CDC Arboviral Disease Branch noted.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The pregnancy-related figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Updated AAP safe sleep recs for infants reinforce life-saving messages

SAN FRANCISCO – At sleep time, infants should share their parents’ bedroom on a separate sleep surface without bed sharing, should be placed on their backs on a firm surface, and should have a sleep area free of blankets and soft objects, according to updated guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics aimed at reducing the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and other sleep-related infant deaths.

Drafted by a multidisciplinary task force, the set of 19 evidence-based recommendations largely reiterate messages that the academy has promoted for years such as “back to sleep for every sleep,” according to task force member Fern R. Hauck, MD, the Spencer P. Bass, MD, Twenty-First Century Professor of Family Medicine at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. They were unveiled in a press briefing at the academy’s annual meeting and simultaneously published (Pediatrics. 2016;138[5]:e20162938).

Progress, but still a ways to go

Education campaigns that convey these and related messages to new parents and other caregivers have led to a more than halving of the rate of SIDS in recent decades. Yet, 3,500 infants are still lost each year to this syndrome and other sleep-related causes of infant death, such as unintentional suffocation, collectively called sudden unexpected infant death (SUID).

New is a recommendation for skin-to-skin care for at least the first hour of life for healthy newborns, as soon as the mother is alert enough to respond to her infant, according to Dr. Hauck. The aims here are to optimize neurodevelopment and promote temperature regulation.

There is no evidence that swaddling reduces the risk of SIDS, but parents can still use this technique if they wish as long as infants are placed on their back and it is discontinued as soon as they start to show signs of rolling over, she said. Evidence is also lacking for new technologies marketed as protective, for example, crib mattresses designed to reduce re-breathing of carbon dioxide should an infant become prone.

Sleeping in the parents’ room but on a separate surface decreases the risk of SIDS by as much as 50%, according to several studies. Bed sharing is not recommended because of the risk of suffocation, strangulation, and entrapment, the policy states.

The updated recommendations should be followed for every sleep and by every caregiver, until the child reaches 1 year of age, Dr. Hauck stressed. “This includes nap time and bedtime sleep, at home, in day care, or in any other locations where the baby is sleeping.”

“We feel that these messages need to start while the mom’s pregnant because some of the decisions that are made that are not always the best decisions, when the mother is exhausted, can occur spur of the moment,” she added. “As pediatricians, you can set up a prebirth visit to start talking about this, and obstetricians should be doing more as well to bring this up during their prenatal visits.”

Other recommendations include offering a pacifier at nap time and bedtime; avoiding smoke exposure during pregnancy and after birth; and avoiding alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy and after birth.

Breastfeeding issues

Although breastfeeding protects against SIDS, it can pose some problems for safe sleep practices, acknowledged Lori B. Feldman-Winter, MD, a liaison from the AAP section on breastfeeding to the task force, as well as head of the division of adolescent medicine and professor of pediatrics at Cooper University Health Care in Camden, N.J.

Bedside sleepers (also called sidecar sleepers) that attach to the parents’ bed may help facilitate the dual aims of breastfeeding and safe sleep, but they have not been formally studied to assess their impact on SIDS risk.

Raising awareness

“As a father and pediatrician, I want parents to know that their baby is safest following the AAP safe sleep recommendations, and spreading this message has become my life’s mission,” said Dr. Samuel P. Hanke, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of Cincinnati, who knows the heartbreak of SIDS firsthand.

“We know practicing safe sleep is hard. We have to be vigilant. We need to start adopting a mentality that safe sleep is not negotiable,” Dr. Hanke asserted. “We cannot emphasize enough that practicing safe sleep for every sleep is as important as buckling your child into a car seat for every drive. And just like car seats, this change won’t occur overnight.”

Federal commitment

Since the 1970s, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in Bethesda, Md., has been supporting and performing much of the research on which the updated recommendations are based. This research continues to help identify areas where greater efforts are needed, according to acting director Catherine Y. Spong, MD.

NICHD also conducts and collaborates on related education campaigns, such as Safe to Sleep, to disseminate messages such as those in the updated AAP recommendations as widely as possible.

“I encourage all physicians, pediatricians, nurses, and other health care and child care providers to lend their authoritative voices to the Safe to Sleep effort,” Dr. Spong said. “Join us all in sharing safe infant sleep recommendations and in supporting parents and caregivers to make informed decisions that will help keep their baby safe during sleep.”

A closer look at setting

Published in conjunction with the guidelines is a study on risk factors that looked at the role of the setting in which sleep-related infant deaths occur (Pediatrics. 2016 Oct 24:e20161124).

The analysis of nearly 12,000 such deaths found that, relative to counterparts who died in their home, infants who died outside of their home were more likely to be in a stroller or car seat at the time (adjusted odds ratio, 2.6) and in other locations, such as on the floor or a futon (1.9), and to have been placed prone (1.1). They were less likely to have been sharing a bed (0.7).

The groups did not differ in terms of whether the infant was sleeping in an adult bed or on a person, on a couch or chair, or with any objects in their sleep environment.

“Caregivers should be educated on the importance of placing infants to sleep supine in cribs/bassinets to protect against sleep-related deaths, both in and out of the home,” conclude the investigators, one of whom disclosed serving as a paid expert witness in cases of sleep-related infant death.

SAN FRANCISCO – At sleep time, infants should share their parents’ bedroom on a separate sleep surface without bed sharing, should be placed on their backs on a firm surface, and should have a sleep area free of blankets and soft objects, according to updated guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics aimed at reducing the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and other sleep-related infant deaths.

Drafted by a multidisciplinary task force, the set of 19 evidence-based recommendations largely reiterate messages that the academy has promoted for years such as “back to sleep for every sleep,” according to task force member Fern R. Hauck, MD, the Spencer P. Bass, MD, Twenty-First Century Professor of Family Medicine at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. They were unveiled in a press briefing at the academy’s annual meeting and simultaneously published (Pediatrics. 2016;138[5]:e20162938).

Progress, but still a ways to go

Education campaigns that convey these and related messages to new parents and other caregivers have led to a more than halving of the rate of SIDS in recent decades. Yet, 3,500 infants are still lost each year to this syndrome and other sleep-related causes of infant death, such as unintentional suffocation, collectively called sudden unexpected infant death (SUID).

New is a recommendation for skin-to-skin care for at least the first hour of life for healthy newborns, as soon as the mother is alert enough to respond to her infant, according to Dr. Hauck. The aims here are to optimize neurodevelopment and promote temperature regulation.

There is no evidence that swaddling reduces the risk of SIDS, but parents can still use this technique if they wish as long as infants are placed on their back and it is discontinued as soon as they start to show signs of rolling over, she said. Evidence is also lacking for new technologies marketed as protective, for example, crib mattresses designed to reduce re-breathing of carbon dioxide should an infant become prone.

Sleeping in the parents’ room but on a separate surface decreases the risk of SIDS by as much as 50%, according to several studies. Bed sharing is not recommended because of the risk of suffocation, strangulation, and entrapment, the policy states.

The updated recommendations should be followed for every sleep and by every caregiver, until the child reaches 1 year of age, Dr. Hauck stressed. “This includes nap time and bedtime sleep, at home, in day care, or in any other locations where the baby is sleeping.”

“We feel that these messages need to start while the mom’s pregnant because some of the decisions that are made that are not always the best decisions, when the mother is exhausted, can occur spur of the moment,” she added. “As pediatricians, you can set up a prebirth visit to start talking about this, and obstetricians should be doing more as well to bring this up during their prenatal visits.”

Other recommendations include offering a pacifier at nap time and bedtime; avoiding smoke exposure during pregnancy and after birth; and avoiding alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy and after birth.

Breastfeeding issues

Although breastfeeding protects against SIDS, it can pose some problems for safe sleep practices, acknowledged Lori B. Feldman-Winter, MD, a liaison from the AAP section on breastfeeding to the task force, as well as head of the division of adolescent medicine and professor of pediatrics at Cooper University Health Care in Camden, N.J.

Bedside sleepers (also called sidecar sleepers) that attach to the parents’ bed may help facilitate the dual aims of breastfeeding and safe sleep, but they have not been formally studied to assess their impact on SIDS risk.

Raising awareness

“As a father and pediatrician, I want parents to know that their baby is safest following the AAP safe sleep recommendations, and spreading this message has become my life’s mission,” said Dr. Samuel P. Hanke, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of Cincinnati, who knows the heartbreak of SIDS firsthand.

“We know practicing safe sleep is hard. We have to be vigilant. We need to start adopting a mentality that safe sleep is not negotiable,” Dr. Hanke asserted. “We cannot emphasize enough that practicing safe sleep for every sleep is as important as buckling your child into a car seat for every drive. And just like car seats, this change won’t occur overnight.”

Federal commitment

Since the 1970s, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in Bethesda, Md., has been supporting and performing much of the research on which the updated recommendations are based. This research continues to help identify areas where greater efforts are needed, according to acting director Catherine Y. Spong, MD.

NICHD also conducts and collaborates on related education campaigns, such as Safe to Sleep, to disseminate messages such as those in the updated AAP recommendations as widely as possible.

“I encourage all physicians, pediatricians, nurses, and other health care and child care providers to lend their authoritative voices to the Safe to Sleep effort,” Dr. Spong said. “Join us all in sharing safe infant sleep recommendations and in supporting parents and caregivers to make informed decisions that will help keep their baby safe during sleep.”

A closer look at setting

Published in conjunction with the guidelines is a study on risk factors that looked at the role of the setting in which sleep-related infant deaths occur (Pediatrics. 2016 Oct 24:e20161124).

The analysis of nearly 12,000 such deaths found that, relative to counterparts who died in their home, infants who died outside of their home were more likely to be in a stroller or car seat at the time (adjusted odds ratio, 2.6) and in other locations, such as on the floor or a futon (1.9), and to have been placed prone (1.1). They were less likely to have been sharing a bed (0.7).

The groups did not differ in terms of whether the infant was sleeping in an adult bed or on a person, on a couch or chair, or with any objects in their sleep environment.

“Caregivers should be educated on the importance of placing infants to sleep supine in cribs/bassinets to protect against sleep-related deaths, both in and out of the home,” conclude the investigators, one of whom disclosed serving as a paid expert witness in cases of sleep-related infant death.

SAN FRANCISCO – At sleep time, infants should share their parents’ bedroom on a separate sleep surface without bed sharing, should be placed on their backs on a firm surface, and should have a sleep area free of blankets and soft objects, according to updated guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics aimed at reducing the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and other sleep-related infant deaths.

Drafted by a multidisciplinary task force, the set of 19 evidence-based recommendations largely reiterate messages that the academy has promoted for years such as “back to sleep for every sleep,” according to task force member Fern R. Hauck, MD, the Spencer P. Bass, MD, Twenty-First Century Professor of Family Medicine at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. They were unveiled in a press briefing at the academy’s annual meeting and simultaneously published (Pediatrics. 2016;138[5]:e20162938).

Progress, but still a ways to go

Education campaigns that convey these and related messages to new parents and other caregivers have led to a more than halving of the rate of SIDS in recent decades. Yet, 3,500 infants are still lost each year to this syndrome and other sleep-related causes of infant death, such as unintentional suffocation, collectively called sudden unexpected infant death (SUID).

New is a recommendation for skin-to-skin care for at least the first hour of life for healthy newborns, as soon as the mother is alert enough to respond to her infant, according to Dr. Hauck. The aims here are to optimize neurodevelopment and promote temperature regulation.

There is no evidence that swaddling reduces the risk of SIDS, but parents can still use this technique if they wish as long as infants are placed on their back and it is discontinued as soon as they start to show signs of rolling over, she said. Evidence is also lacking for new technologies marketed as protective, for example, crib mattresses designed to reduce re-breathing of carbon dioxide should an infant become prone.

Sleeping in the parents’ room but on a separate surface decreases the risk of SIDS by as much as 50%, according to several studies. Bed sharing is not recommended because of the risk of suffocation, strangulation, and entrapment, the policy states.

The updated recommendations should be followed for every sleep and by every caregiver, until the child reaches 1 year of age, Dr. Hauck stressed. “This includes nap time and bedtime sleep, at home, in day care, or in any other locations where the baby is sleeping.”

“We feel that these messages need to start while the mom’s pregnant because some of the decisions that are made that are not always the best decisions, when the mother is exhausted, can occur spur of the moment,” she added. “As pediatricians, you can set up a prebirth visit to start talking about this, and obstetricians should be doing more as well to bring this up during their prenatal visits.”

Other recommendations include offering a pacifier at nap time and bedtime; avoiding smoke exposure during pregnancy and after birth; and avoiding alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy and after birth.

Breastfeeding issues

Although breastfeeding protects against SIDS, it can pose some problems for safe sleep practices, acknowledged Lori B. Feldman-Winter, MD, a liaison from the AAP section on breastfeeding to the task force, as well as head of the division of adolescent medicine and professor of pediatrics at Cooper University Health Care in Camden, N.J.

Bedside sleepers (also called sidecar sleepers) that attach to the parents’ bed may help facilitate the dual aims of breastfeeding and safe sleep, but they have not been formally studied to assess their impact on SIDS risk.

Raising awareness

“As a father and pediatrician, I want parents to know that their baby is safest following the AAP safe sleep recommendations, and spreading this message has become my life’s mission,” said Dr. Samuel P. Hanke, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of Cincinnati, who knows the heartbreak of SIDS firsthand.

“We know practicing safe sleep is hard. We have to be vigilant. We need to start adopting a mentality that safe sleep is not negotiable,” Dr. Hanke asserted. “We cannot emphasize enough that practicing safe sleep for every sleep is as important as buckling your child into a car seat for every drive. And just like car seats, this change won’t occur overnight.”

Federal commitment

Since the 1970s, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in Bethesda, Md., has been supporting and performing much of the research on which the updated recommendations are based. This research continues to help identify areas where greater efforts are needed, according to acting director Catherine Y. Spong, MD.

NICHD also conducts and collaborates on related education campaigns, such as Safe to Sleep, to disseminate messages such as those in the updated AAP recommendations as widely as possible.

“I encourage all physicians, pediatricians, nurses, and other health care and child care providers to lend their authoritative voices to the Safe to Sleep effort,” Dr. Spong said. “Join us all in sharing safe infant sleep recommendations and in supporting parents and caregivers to make informed decisions that will help keep their baby safe during sleep.”

A closer look at setting

Published in conjunction with the guidelines is a study on risk factors that looked at the role of the setting in which sleep-related infant deaths occur (Pediatrics. 2016 Oct 24:e20161124).

The analysis of nearly 12,000 such deaths found that, relative to counterparts who died in their home, infants who died outside of their home were more likely to be in a stroller or car seat at the time (adjusted odds ratio, 2.6) and in other locations, such as on the floor or a futon (1.9), and to have been placed prone (1.1). They were less likely to have been sharing a bed (0.7).

The groups did not differ in terms of whether the infant was sleeping in an adult bed or on a person, on a couch or chair, or with any objects in their sleep environment.

“Caregivers should be educated on the importance of placing infants to sleep supine in cribs/bassinets to protect against sleep-related deaths, both in and out of the home,” conclude the investigators, one of whom disclosed serving as a paid expert witness in cases of sleep-related infant death.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 16

Medication-assisted treatment in group settings may result in greater job satisfaction, more reimbursements

WASHINGTON – For practices that offer medication-assisted treatment but perhaps are struggling to balance follow-up appointments with new patient inductions, Leah K. Bauer, MD, has a suggestion: group sessions.

“It’s a lot of fun, and makes my practice more dynamic. It gets me out of the grind of ‘see a patient; write a note; repeat,’ ” Dr. Bauer said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

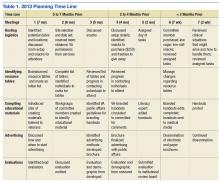

Compressing 26.5 hours of individual clinical time into 12 hours of monthly group sessions held twice a week for 90 minutes each, Dr. Bauer said, resulted in an additional $41,000 of revenue annually, with inductions doubling from 8 to 16 per month.

One reason is that despite the sessions taking place in a group setting, she and her staff bill for a series of individual appointments using the CPT code 99212. “It is perfectly legal, and not very recognized,” Dr. Bauer said, noting that the sessions are in a group context, but that she does get to have one-on-one interaction with her patients with the added therapeutic value that peer support brings.

Modeling appropriate behavior is easier in the group setting, she said: “Patients don’t all have to test the same limits.” Instead, they can learn from the interaction of another patient with Dr. Bauer as the therapist. The group setting also helps her deliver more consistent care to all her patients, she said. “I am more conscious of what I am saying.”

A hospitalist and psychiatrist, Dr. Bauer leads group MAT with the help of a clinician cofacilitator who she says reinforces what is being said in the group and acts as a scribe, reducing Dr. Bauer’s administrative burden. “This improves my job satisfaction tremendously,” she said.

Patients sign a “check-in” sheet that also serves as their treatment plan that includes their goals and objectives. It includes the patients’ written self-reflections, what their week was like, and other entries about their mood and struggles with their recovery. The information also is recorded in their patient records. “The sheet is problem focused, and has a lot of counseling and coordination of care built in,” Dr. Bauer said.

If a patient comes to the session late, there is no lost time or productivity for the MAT team, because the group meets regardless of who attends. Patients can come as much or as little as they like every 1-4 weeks. “It’s very flexible,” Dr. Bauer said.

She does not have data on her patient outcomes in the group setting vs. the individual one, but Dr. Bauer said in an interview that she believes it is as effective and allows more people who need MAT to receive it, because few clinics in her state offer it.

The group structure does place more demand on the hospital’s pharmacy, she said, in that, after the sessions, patients arrive en masse to fill their buprenorphine prescriptions.

Questions about confidentiality do arise, although each session begins with a reminder to keep private what is shared during the meetings. However, Dr. Bauer said, she thinks some patients remain reluctant to speak their minds for fear of what they say not remaining confidential. “This can limit the depth of what’s discussed,” she said.

Dr. Bauer said she did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – For practices that offer medication-assisted treatment but perhaps are struggling to balance follow-up appointments with new patient inductions, Leah K. Bauer, MD, has a suggestion: group sessions.

“It’s a lot of fun, and makes my practice more dynamic. It gets me out of the grind of ‘see a patient; write a note; repeat,’ ” Dr. Bauer said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

Compressing 26.5 hours of individual clinical time into 12 hours of monthly group sessions held twice a week for 90 minutes each, Dr. Bauer said, resulted in an additional $41,000 of revenue annually, with inductions doubling from 8 to 16 per month.

One reason is that despite the sessions taking place in a group setting, she and her staff bill for a series of individual appointments using the CPT code 99212. “It is perfectly legal, and not very recognized,” Dr. Bauer said, noting that the sessions are in a group context, but that she does get to have one-on-one interaction with her patients with the added therapeutic value that peer support brings.

Modeling appropriate behavior is easier in the group setting, she said: “Patients don’t all have to test the same limits.” Instead, they can learn from the interaction of another patient with Dr. Bauer as the therapist. The group setting also helps her deliver more consistent care to all her patients, she said. “I am more conscious of what I am saying.”

A hospitalist and psychiatrist, Dr. Bauer leads group MAT with the help of a clinician cofacilitator who she says reinforces what is being said in the group and acts as a scribe, reducing Dr. Bauer’s administrative burden. “This improves my job satisfaction tremendously,” she said.

Patients sign a “check-in” sheet that also serves as their treatment plan that includes their goals and objectives. It includes the patients’ written self-reflections, what their week was like, and other entries about their mood and struggles with their recovery. The information also is recorded in their patient records. “The sheet is problem focused, and has a lot of counseling and coordination of care built in,” Dr. Bauer said.

If a patient comes to the session late, there is no lost time or productivity for the MAT team, because the group meets regardless of who attends. Patients can come as much or as little as they like every 1-4 weeks. “It’s very flexible,” Dr. Bauer said.

She does not have data on her patient outcomes in the group setting vs. the individual one, but Dr. Bauer said in an interview that she believes it is as effective and allows more people who need MAT to receive it, because few clinics in her state offer it.

The group structure does place more demand on the hospital’s pharmacy, she said, in that, after the sessions, patients arrive en masse to fill their buprenorphine prescriptions.

Questions about confidentiality do arise, although each session begins with a reminder to keep private what is shared during the meetings. However, Dr. Bauer said, she thinks some patients remain reluctant to speak their minds for fear of what they say not remaining confidential. “This can limit the depth of what’s discussed,” she said.

Dr. Bauer said she did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – For practices that offer medication-assisted treatment but perhaps are struggling to balance follow-up appointments with new patient inductions, Leah K. Bauer, MD, has a suggestion: group sessions.

“It’s a lot of fun, and makes my practice more dynamic. It gets me out of the grind of ‘see a patient; write a note; repeat,’ ” Dr. Bauer said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

Compressing 26.5 hours of individual clinical time into 12 hours of monthly group sessions held twice a week for 90 minutes each, Dr. Bauer said, resulted in an additional $41,000 of revenue annually, with inductions doubling from 8 to 16 per month.

One reason is that despite the sessions taking place in a group setting, she and her staff bill for a series of individual appointments using the CPT code 99212. “It is perfectly legal, and not very recognized,” Dr. Bauer said, noting that the sessions are in a group context, but that she does get to have one-on-one interaction with her patients with the added therapeutic value that peer support brings.

Modeling appropriate behavior is easier in the group setting, she said: “Patients don’t all have to test the same limits.” Instead, they can learn from the interaction of another patient with Dr. Bauer as the therapist. The group setting also helps her deliver more consistent care to all her patients, she said. “I am more conscious of what I am saying.”

A hospitalist and psychiatrist, Dr. Bauer leads group MAT with the help of a clinician cofacilitator who she says reinforces what is being said in the group and acts as a scribe, reducing Dr. Bauer’s administrative burden. “This improves my job satisfaction tremendously,” she said.

Patients sign a “check-in” sheet that also serves as their treatment plan that includes their goals and objectives. It includes the patients’ written self-reflections, what their week was like, and other entries about their mood and struggles with their recovery. The information also is recorded in their patient records. “The sheet is problem focused, and has a lot of counseling and coordination of care built in,” Dr. Bauer said.

If a patient comes to the session late, there is no lost time or productivity for the MAT team, because the group meets regardless of who attends. Patients can come as much or as little as they like every 1-4 weeks. “It’s very flexible,” Dr. Bauer said.

She does not have data on her patient outcomes in the group setting vs. the individual one, but Dr. Bauer said in an interview that she believes it is as effective and allows more people who need MAT to receive it, because few clinics in her state offer it.

The group structure does place more demand on the hospital’s pharmacy, she said, in that, after the sessions, patients arrive en masse to fill their buprenorphine prescriptions.

Questions about confidentiality do arise, although each session begins with a reminder to keep private what is shared during the meetings. However, Dr. Bauer said, she thinks some patients remain reluctant to speak their minds for fear of what they say not remaining confidential. “This can limit the depth of what’s discussed,” she said.

Dr. Bauer said she did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Verrucous Plaque on the Leg

Blastomycosis

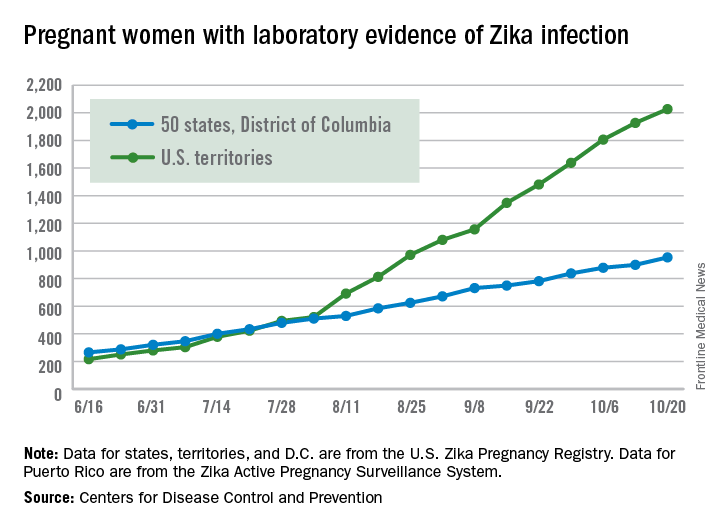

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

2016 a big year for mental health legislation

• The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act. Signed into law in July, CARA is primarily intended, as its name indicates, to comprehensively address the opioid addiction crisis. The law includes components aimed at prevention, treatment, recovery, law enforcement, criminal justice reform, and overdose treatment. It also has provisions aimed at expanded prescription drug monitoring programs and other drug abuse prevention mechanisms.

Another important part of this law is the expansion of buprenorphine prescribing rights to nurse practitioners and physician assistants who obtain the necessary training. Public comment is being taken through Nov. 1, on what the requirements should be. This provision will be revisited in 2021.

In all, the law allocates $25 million annually from 2017 through 2021 to expand medication-assisted treatment (MAT). An abundance of evidence shows that MAT – the use of opioid agonists and partial opioid agonists such as methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, in combination with psychosocial therapies – is more effective than either modality alone.

• The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act. Originating in 2013 in response to the Newtown, Conn., massacre, this bill (H.R. 2646) is focused on serious mental illness. It passed the House in July with near unanimous support, but awaits the Senate to sort out its own version of the bill. If this bill is passed, HIPAA laws would loosen, allowing practices to share all but psychotherapy notes with caregivers and guardians of people with serious mental illness. Practices also could bill Medicaid and Medicare for medical and mental health services delivered on the same day, and there would be support for the better integration of medical and mental health electronic medical records. The current 30-day limit on inpatient psychiatric facility services paid for by Medicaid would be lifted, and $20 million in grants would be made available for assisted outpatient treatment of this population. Grants for expanded use of telepsychiatry also would be available.

• The Mental Health Reform Act of 2016. Essentially the companion bill to the one passed in the House, this bill (S. 2680) also calls for the expansion of telepsychiatry, especially for pediatric and adolescent mental and behavioral health needs. If it becomes law, grant money would be made available for better integration of primary and behavioral health care services. This bill calls for strengthening current mental health parity laws by requiring additional federal guidance to help insurance plans comply. The bill currently is stalled on the Senate floor and is not expected to be revisited until after the presidential election.

• The Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorders final rule. As of August, the rule allows addiction medicine specialists to treat up to 275 patients using buprenorphine for substance use disorder annually. Previously, they were held to treating no more than 100 such patients per year. For practices not already licensed to provide MAT, this rule doesn’t have much direct impact. However, for practices with patients on their panels who are struggling with substance use disorders, this could expand available referral resources.

• The Quality Payment Program final rule. While this rule – borne of the MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act) law that is now referred to as the Quality Payment Program – does not directly address mental and behavioral health, it directly affects delivery of these services when it goes into effect in 2017. Because mental and behavioral health outcomes of patient panels that include Medicare populations will be assessed as part of overall patient outcomes, providing effective, integrated services will be imperative. How severely a practice will be penalized for poor outcomes will depend upon how that practice chooses to set up its reimbursement structures and quality metrics over the next few years.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

• The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act. Signed into law in July, CARA is primarily intended, as its name indicates, to comprehensively address the opioid addiction crisis. The law includes components aimed at prevention, treatment, recovery, law enforcement, criminal justice reform, and overdose treatment. It also has provisions aimed at expanded prescription drug monitoring programs and other drug abuse prevention mechanisms.

Another important part of this law is the expansion of buprenorphine prescribing rights to nurse practitioners and physician assistants who obtain the necessary training. Public comment is being taken through Nov. 1, on what the requirements should be. This provision will be revisited in 2021.

In all, the law allocates $25 million annually from 2017 through 2021 to expand medication-assisted treatment (MAT). An abundance of evidence shows that MAT – the use of opioid agonists and partial opioid agonists such as methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, in combination with psychosocial therapies – is more effective than either modality alone.

• The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act. Originating in 2013 in response to the Newtown, Conn., massacre, this bill (H.R. 2646) is focused on serious mental illness. It passed the House in July with near unanimous support, but awaits the Senate to sort out its own version of the bill. If this bill is passed, HIPAA laws would loosen, allowing practices to share all but psychotherapy notes with caregivers and guardians of people with serious mental illness. Practices also could bill Medicaid and Medicare for medical and mental health services delivered on the same day, and there would be support for the better integration of medical and mental health electronic medical records. The current 30-day limit on inpatient psychiatric facility services paid for by Medicaid would be lifted, and $20 million in grants would be made available for assisted outpatient treatment of this population. Grants for expanded use of telepsychiatry also would be available.

• The Mental Health Reform Act of 2016. Essentially the companion bill to the one passed in the House, this bill (S. 2680) also calls for the expansion of telepsychiatry, especially for pediatric and adolescent mental and behavioral health needs. If it becomes law, grant money would be made available for better integration of primary and behavioral health care services. This bill calls for strengthening current mental health parity laws by requiring additional federal guidance to help insurance plans comply. The bill currently is stalled on the Senate floor and is not expected to be revisited until after the presidential election.

• The Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorders final rule. As of August, the rule allows addiction medicine specialists to treat up to 275 patients using buprenorphine for substance use disorder annually. Previously, they were held to treating no more than 100 such patients per year. For practices not already licensed to provide MAT, this rule doesn’t have much direct impact. However, for practices with patients on their panels who are struggling with substance use disorders, this could expand available referral resources.

• The Quality Payment Program final rule. While this rule – borne of the MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act) law that is now referred to as the Quality Payment Program – does not directly address mental and behavioral health, it directly affects delivery of these services when it goes into effect in 2017. Because mental and behavioral health outcomes of patient panels that include Medicare populations will be assessed as part of overall patient outcomes, providing effective, integrated services will be imperative. How severely a practice will be penalized for poor outcomes will depend upon how that practice chooses to set up its reimbursement structures and quality metrics over the next few years.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

• The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act. Signed into law in July, CARA is primarily intended, as its name indicates, to comprehensively address the opioid addiction crisis. The law includes components aimed at prevention, treatment, recovery, law enforcement, criminal justice reform, and overdose treatment. It also has provisions aimed at expanded prescription drug monitoring programs and other drug abuse prevention mechanisms.

Another important part of this law is the expansion of buprenorphine prescribing rights to nurse practitioners and physician assistants who obtain the necessary training. Public comment is being taken through Nov. 1, on what the requirements should be. This provision will be revisited in 2021.

In all, the law allocates $25 million annually from 2017 through 2021 to expand medication-assisted treatment (MAT). An abundance of evidence shows that MAT – the use of opioid agonists and partial opioid agonists such as methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, in combination with psychosocial therapies – is more effective than either modality alone.

• The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act. Originating in 2013 in response to the Newtown, Conn., massacre, this bill (H.R. 2646) is focused on serious mental illness. It passed the House in July with near unanimous support, but awaits the Senate to sort out its own version of the bill. If this bill is passed, HIPAA laws would loosen, allowing practices to share all but psychotherapy notes with caregivers and guardians of people with serious mental illness. Practices also could bill Medicaid and Medicare for medical and mental health services delivered on the same day, and there would be support for the better integration of medical and mental health electronic medical records. The current 30-day limit on inpatient psychiatric facility services paid for by Medicaid would be lifted, and $20 million in grants would be made available for assisted outpatient treatment of this population. Grants for expanded use of telepsychiatry also would be available.

• The Mental Health Reform Act of 2016. Essentially the companion bill to the one passed in the House, this bill (S. 2680) also calls for the expansion of telepsychiatry, especially for pediatric and adolescent mental and behavioral health needs. If it becomes law, grant money would be made available for better integration of primary and behavioral health care services. This bill calls for strengthening current mental health parity laws by requiring additional federal guidance to help insurance plans comply. The bill currently is stalled on the Senate floor and is not expected to be revisited until after the presidential election.

• The Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorders final rule. As of August, the rule allows addiction medicine specialists to treat up to 275 patients using buprenorphine for substance use disorder annually. Previously, they were held to treating no more than 100 such patients per year. For practices not already licensed to provide MAT, this rule doesn’t have much direct impact. However, for practices with patients on their panels who are struggling with substance use disorders, this could expand available referral resources.

• The Quality Payment Program final rule. While this rule – borne of the MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act) law that is now referred to as the Quality Payment Program – does not directly address mental and behavioral health, it directly affects delivery of these services when it goes into effect in 2017. Because mental and behavioral health outcomes of patient panels that include Medicare populations will be assessed as part of overall patient outcomes, providing effective, integrated services will be imperative. How severely a practice will be penalized for poor outcomes will depend upon how that practice chooses to set up its reimbursement structures and quality metrics over the next few years.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Aquatic Antagonists: Cutaneous Sea Urchin Spine Injury

Sea urchin injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions near both warm and cold salt water with frequent recreational water activities or fishing. Sea urchins belong to the class Echinoidea with approximately 600 species, of which roughly 80 are poisonous to humans.1,2 When a human comes in contact with a sea urchin, the spines of the sea urchin (made of calcium carbonate) can penetrate the skin and break off from the sea urchin, becoming embedded in the skin. Injuries from sea urchin spines are most commonly seen on the hands and feet, as the likelihood of contact with a sea urchin is greater on these sites. The severity of sea urchin spine injuries can vary widely, from minimal local trauma and pain to arthritis, synovitis, and occasionally systemic illness.1,3 It is important to recognize the wide variety of responses to sea urchin spine injuries and the impact of prompt treatment. Many published reports on injuries from sea urchin spines describe arthritis and synovitis from spines in the joints.1,2,4-6 Fewer reports discuss nonjoint injuries and the dermatologic aspects of sea urchin spine injuries.3,7,8 We pre-sent a case of a patient with a puncture injury from sea urchin spines that resulted in painful granulomas.

Case Report

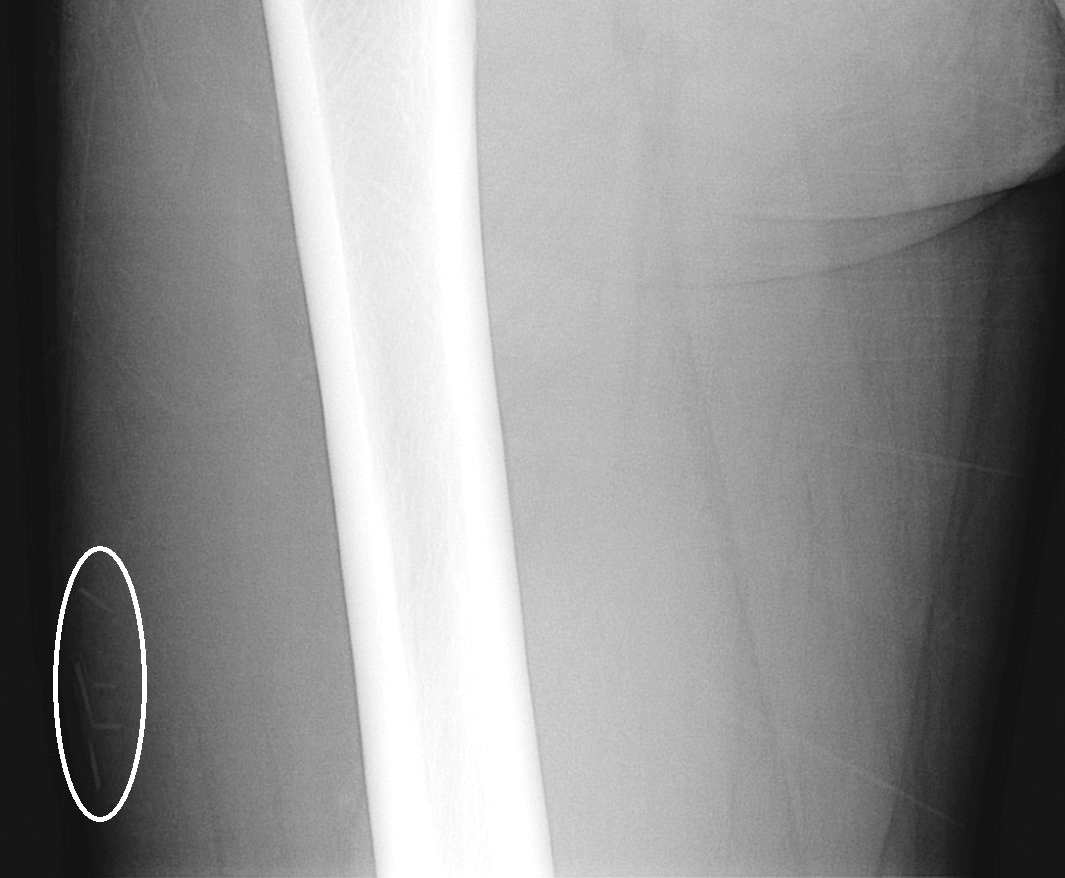

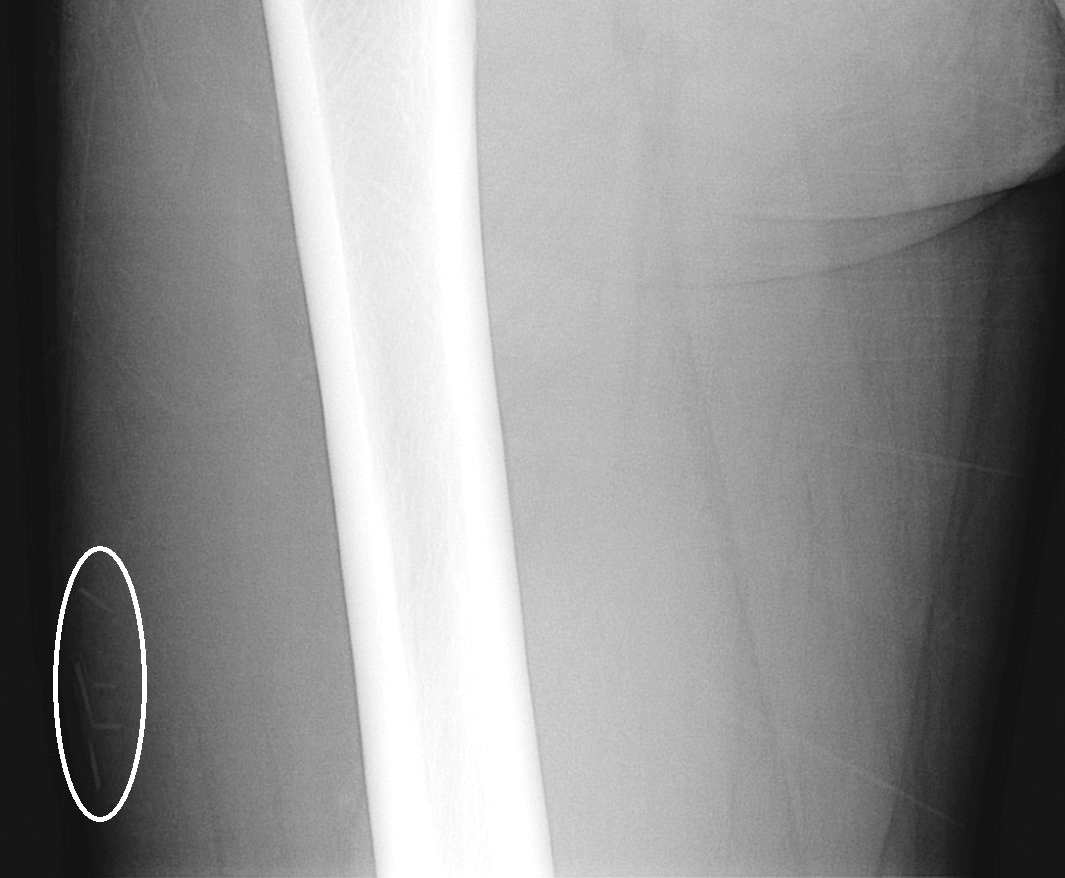

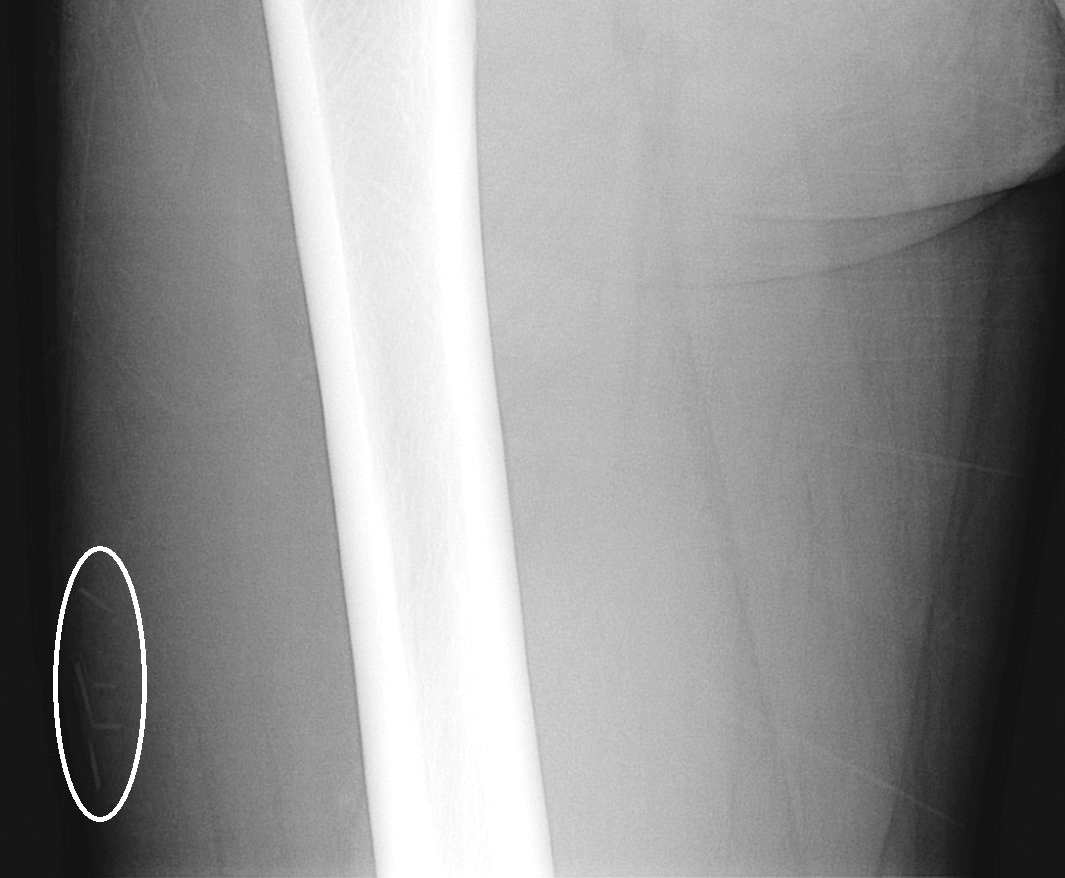

A 29-year-old otherwise healthy man was referred to our dermatology clinic by the university student health center due to continued pain in the right thigh. Five weeks prior to presentation to the student health center, the patient had fallen on a sea urchin while snorkeling in Hawaii. Sea urchin spines became lodged in the right thigh, some of which were removed in a local medical clinic in Hawaii. He was given oral antibiotics prior to his return home. A plain film radiograph of the affected area ordered by the student health center showed several punctate and linear densities in the lateral aspect of the right mid thigh (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with sea urchin spines within the superficial soft tissues of the lateral thigh.

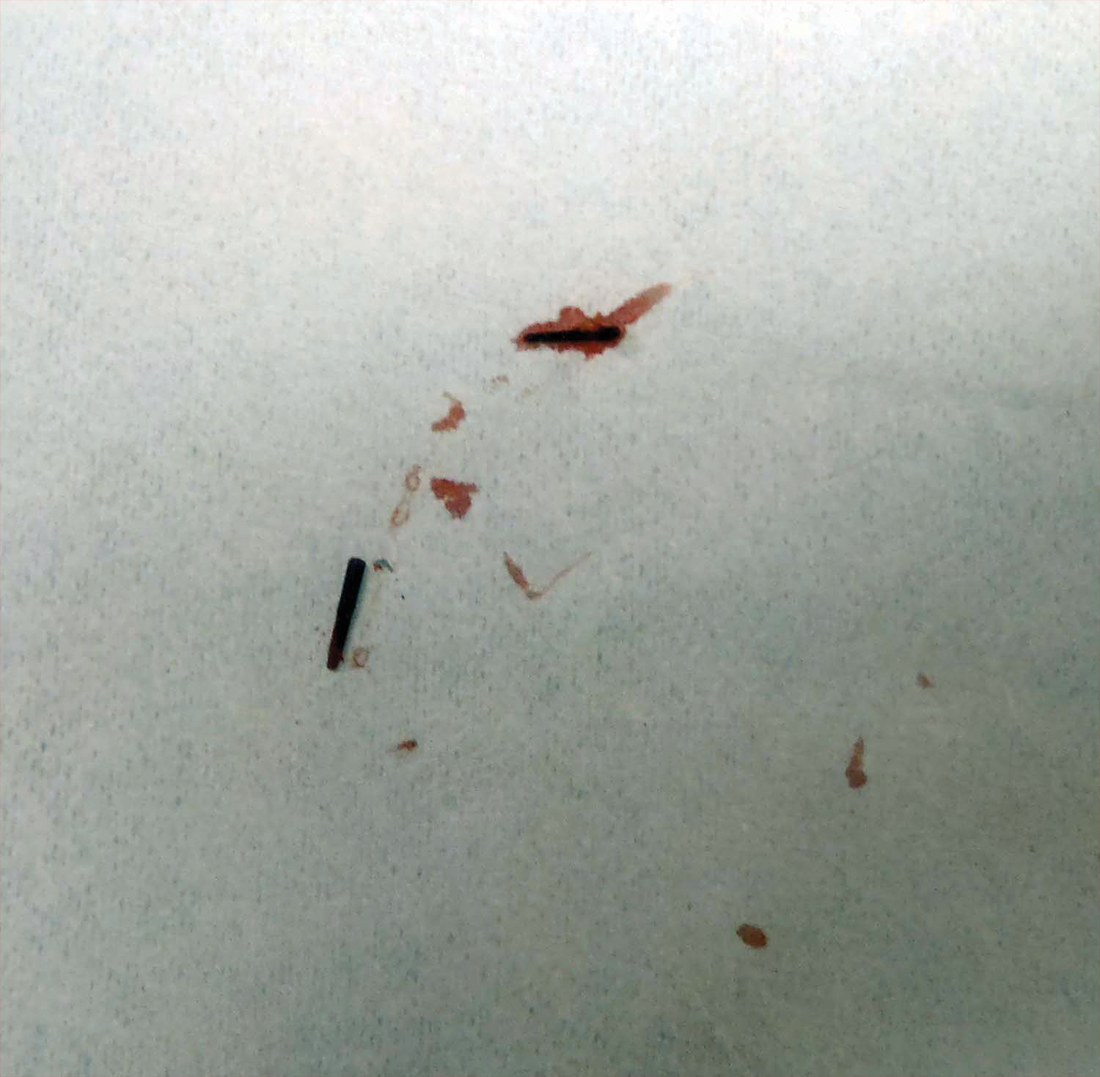

At the time of presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient reported sharp intermittent pain localized to the right thigh. The patient denied any fever, chills, or pain in the joints. On physical examination, there were several firm nodules on the right thigh, ranging from 4 to 20 mm in diameter (Figure 2). The nodules were tender to palpation with some surrounding edema. Drainage was not noted. Several scars were visible at sites of the original puncture injuries and removal of the spines.

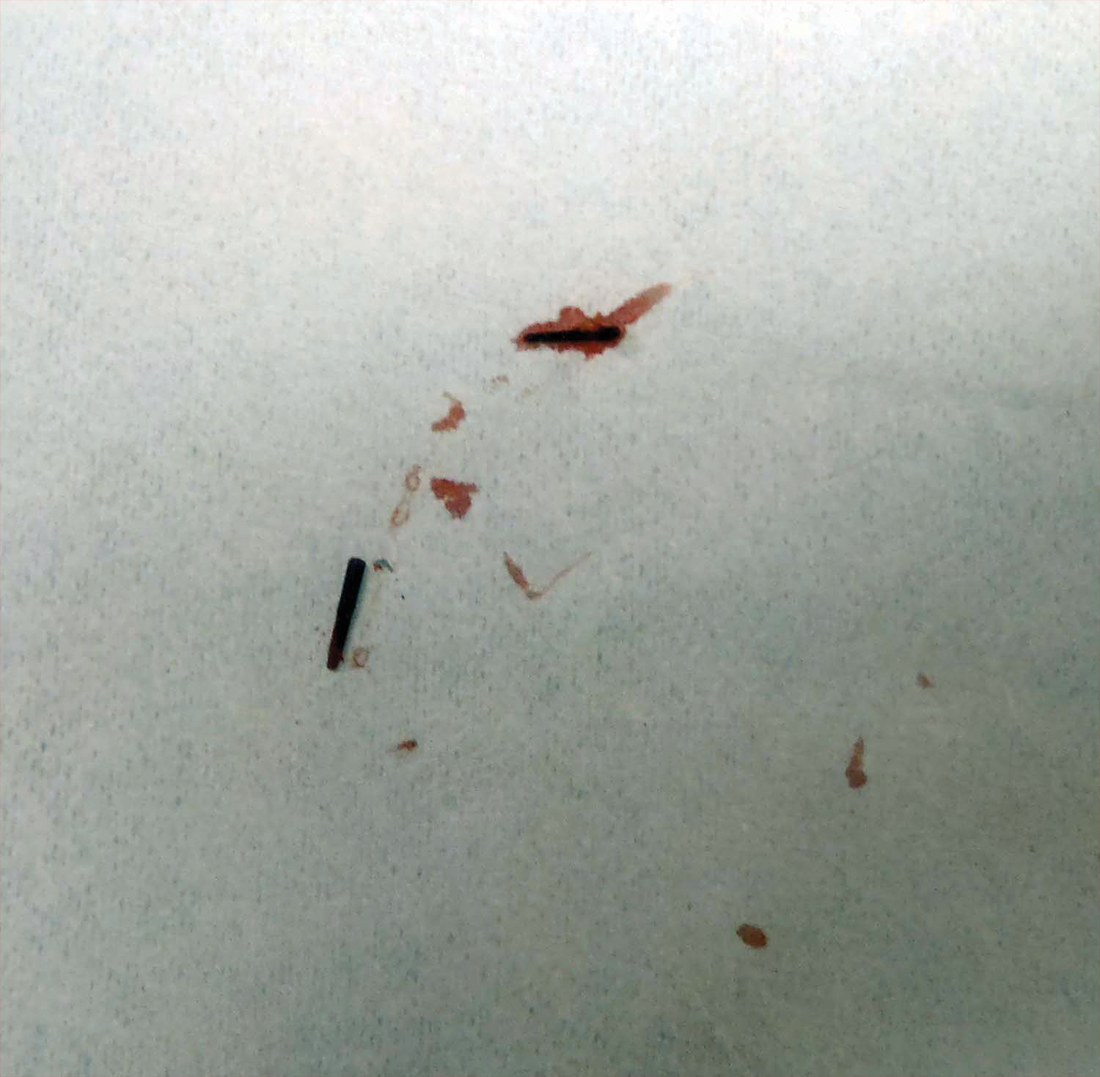

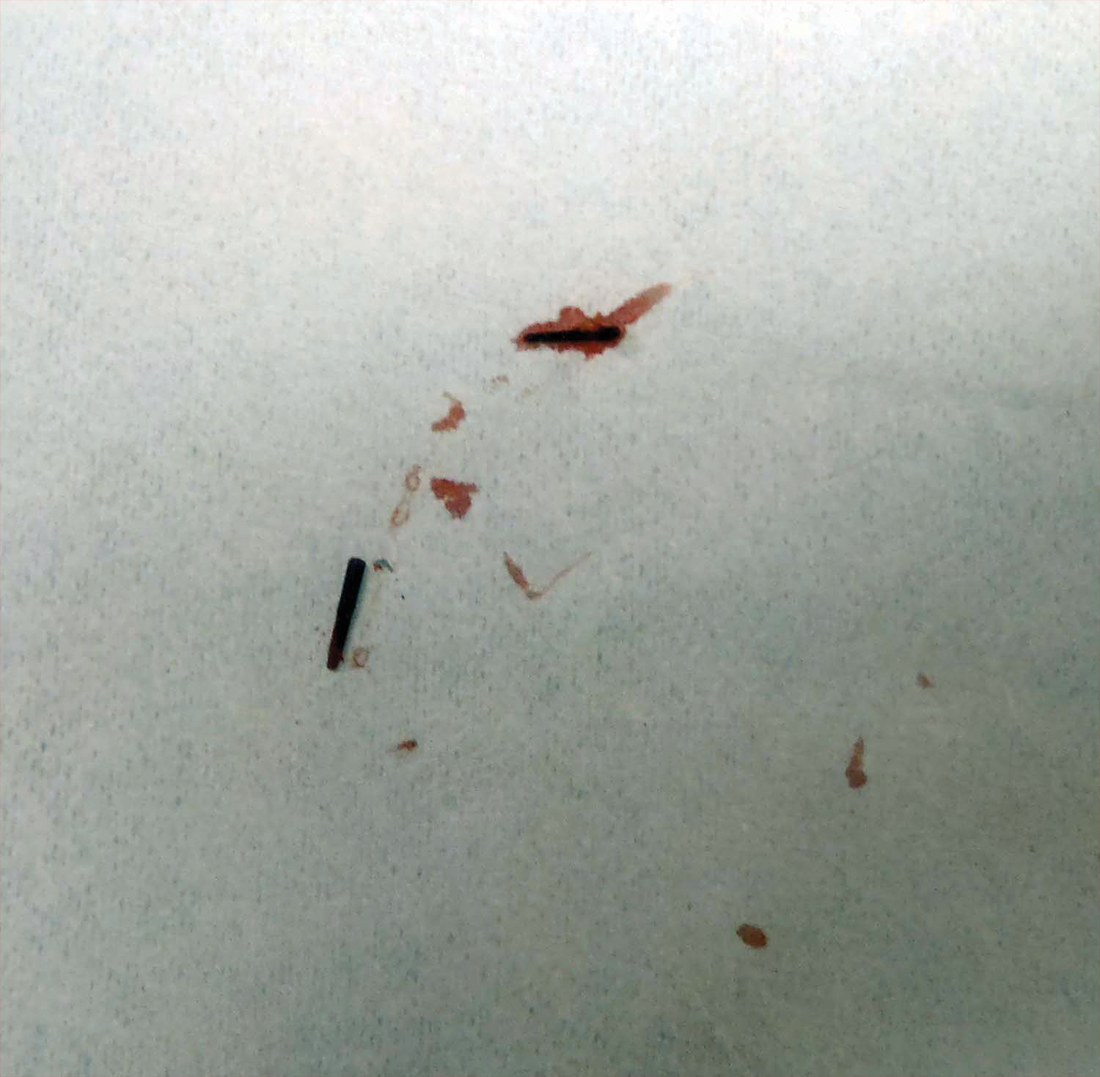

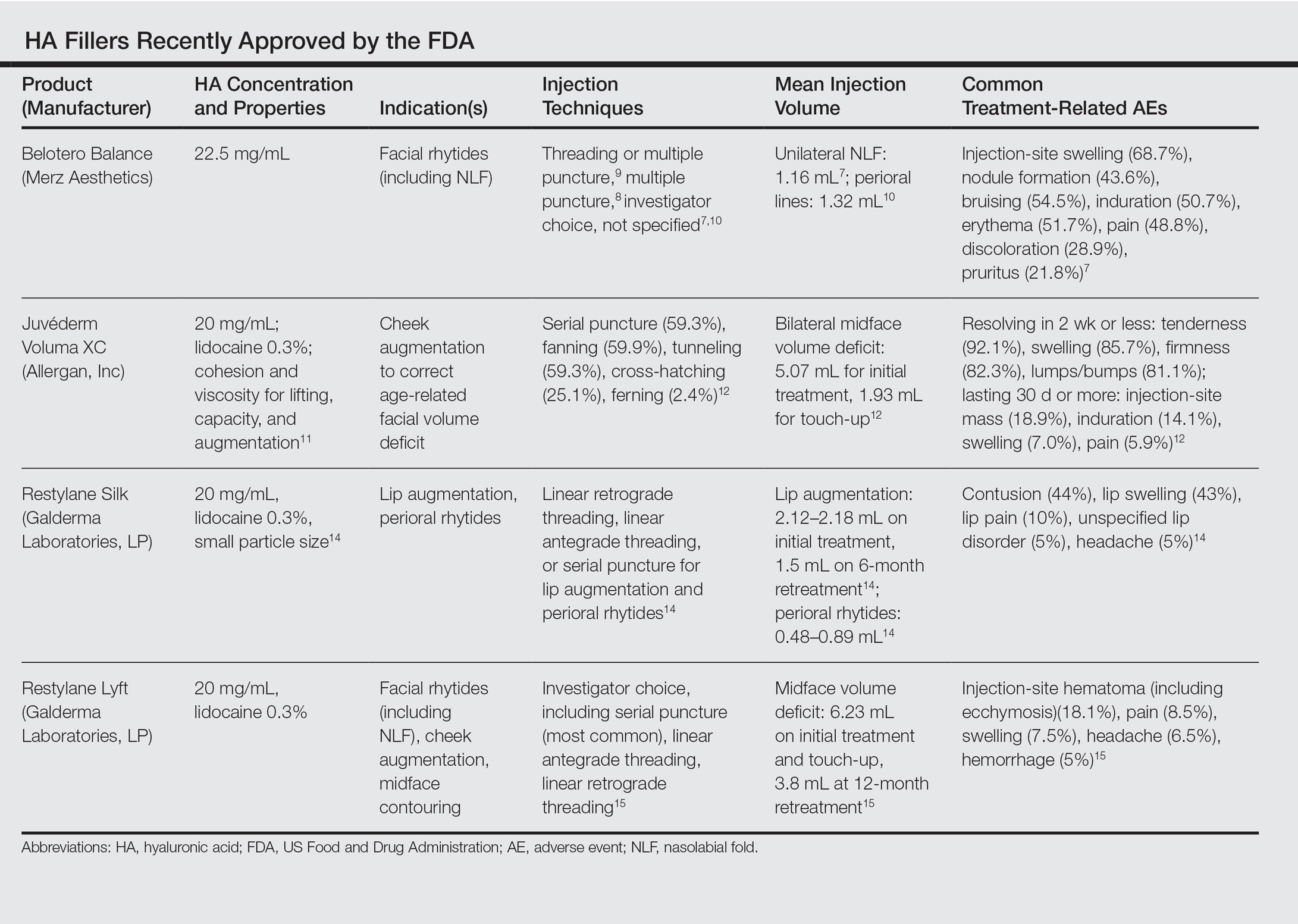

Two 6-mm punch biopsies were performed on representative nodules on the right thigh for histopathologic examination. Along with the biopsy tissue, firm, brown-black, linear foreign bodies consistent with sea urchin spines were extracted with forceps (Figure 3). Histopathologic examination revealed a dense, diffuse, mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis predominantly composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils. Proliferation of small vessels was noted. In one of the biopsies, small fragments of necrotic tissue were present. These findings were consistent with granulomatous inflammation and granulation tissue due to a foreign body.

At the time of suture removal 2 weeks later, the biopsied areas were well healed with minimal erythema. The patient reported decreased pain in the involved areas. He was not seen in clinic again due to resolution of the nodules and associated pain.

Comment

Sea urchin spine injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions with frequent participation in recreational and occupational water activities. A wide variety of responses can be seen in sea urchin spine injuries. There generally are 2 types of cutaneous reaction patterns to sea urchin spines: a primary initial reaction and a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction. When the spines initially penetrate the skin, the primary initial reaction consists of sharp localized pain that worsens with applied pressure. In addition to pain, bleeding, erythema, edema, and myalgia can occur.3 These symptoms typically subside a few hours after complete removal of the spines from the skin.6 If some spines remain in the skin, a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction can occur, which can lead to the formation of granulomas that can manifest as nodules or papules and can be diffuse.

Many patients may think their painful encounter with a sea urchin was just an unfortunate event, but depending on the location of the injury, more serious extracutaneous reactions and chronic symptoms may occur. Some cases have described the development of arthritis and synovitis from the implantation of spines into joints.1,2,4-6 Other extracutaneous complications include neuropathy and paresthesia, local bone destruction, radiating pain, muscular weakness, and hypotension.3

The severity of the injury also can depend on the sea urchin species and the number of spines implanted. There are approximately 80 poisonous sea urchin species possessing toxins in venomous spines, resulting in edema and change in the leukocyte-endothelial interaction.9 Substances identified in the spines include proteins, steroids, serotonin, histamine, and glycosides.3,9 The number of spines implanted, particularly the number of venomous spines, can lead to more severe complications. Penetration of 15 or more venomous spines can commonly lead to extracutaneous symptoms.3 Another concern, irrespective of species type, is the potential for secondary infection associated with the spine penetration or implantation into the skin. Mycobacterium marinum infections have been reported in some sea urchin granulomas,10 as well as fungal infection, bacterial infection, and tetanus.3

The diagnosis of sea urchin spine injuries starts with a thorough history and physical examination. A positive history of sea urchin contact suggests the diagnosis, and radiographs can be useful to find the location of the spine(s), especially if there are no visible nodules on the skin. However, small fragments of spine may not be completely observed on plain radiographs. Any signs or symptoms of infection should prompt a culture for confirmation and guidance for management. Cutaneous biopsies can be helpful for both diagnosis confirmation and symptomatic relief. Reported cases have described granulomatous reactions in the vast majority of the histologic specimens, with necrosis an additional common finding.7,8 Sea urchin granulomas can be of varying types, the majority being foreign-body and sarcoid types.3,6,7

Treatment of sea urchin spine injuries primarily involves removal of the spines by a physician. Patients may soak the affected areas in warm water prior to the removal of the spines to aid in pain relief. Surgical removal with local anesthesia and cutaneous extraction is a common treatment method, and more extensive surgical removal of the spines is another option, especially in areas around the joints.2 The use of liquid nitrogen or skin punch biopsy also have been described as possible methods to remove the spines.11,12

Conclusion

Sea urchin spine injuries can result in a wide range of cutaneous and systemic complications. Prompt diagnosis and treatment to remove the sea urchin spines can lessen the associated pain and is important in the prevention of more serious complications.

- Liram N, Gomori M, Perouansky M. Sea urchin puncture resulting in PIP joint synovial arthritis: case report and MRI study. J Travel Med. 2000;7:43-45.

- Dahl WJ, Jebson P, Louis DS. Sea urchin injuries to the hand: a case report and review of the literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2010;30:153-156.

- Rossetto AL, de Macedo Mora J, Haddad Junior V. Sea urchin granuloma. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2006;48:303-306.

- Ahmad R, McCann PA, Barakat M, et al. Sea urchin spine injuries of the hand. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33:670-671.

- Schefflein J, Umans H, Ellenbogen D, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis in the foot. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:1327-1331.

- Wada T, Soma T, Gaman K, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis of the hand. J Hand Surg. 2008;33:398-401.

- Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Vieites B, Del Río E, et al. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical features of sea urchin granulomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:550-556.

- De La Torre C, Toribio J. Sea-urchin granuloma: histologic profile. a pathologic study of 50 biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:223-228.

- Sciani JM, Zychar BC, Gonçalves LR, et al. Pro-inflammatory effects of the aqueous extract of Echinometra lucunter sea urchin spines. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2011;236:277-280.

- De la Torre C, Vega A, Carracedo A, et al. Identification of Mycobacterium marinum in sea-urchin granulomas. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:114-116.

- Gargus MD, Morohashi DK. A sea-urchin spine chilling remedy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1867-1868.

- Sjøberg T, de Weerd L. The usefulness of a skin biopsy punch to remove sea urchin spines. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:383.

Sea urchin injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions near both warm and cold salt water with frequent recreational water activities or fishing. Sea urchins belong to the class Echinoidea with approximately 600 species, of which roughly 80 are poisonous to humans.1,2 When a human comes in contact with a sea urchin, the spines of the sea urchin (made of calcium carbonate) can penetrate the skin and break off from the sea urchin, becoming embedded in the skin. Injuries from sea urchin spines are most commonly seen on the hands and feet, as the likelihood of contact with a sea urchin is greater on these sites. The severity of sea urchin spine injuries can vary widely, from minimal local trauma and pain to arthritis, synovitis, and occasionally systemic illness.1,3 It is important to recognize the wide variety of responses to sea urchin spine injuries and the impact of prompt treatment. Many published reports on injuries from sea urchin spines describe arthritis and synovitis from spines in the joints.1,2,4-6 Fewer reports discuss nonjoint injuries and the dermatologic aspects of sea urchin spine injuries.3,7,8 We pre-sent a case of a patient with a puncture injury from sea urchin spines that resulted in painful granulomas.

Case Report

A 29-year-old otherwise healthy man was referred to our dermatology clinic by the university student health center due to continued pain in the right thigh. Five weeks prior to presentation to the student health center, the patient had fallen on a sea urchin while snorkeling in Hawaii. Sea urchin spines became lodged in the right thigh, some of which were removed in a local medical clinic in Hawaii. He was given oral antibiotics prior to his return home. A plain film radiograph of the affected area ordered by the student health center showed several punctate and linear densities in the lateral aspect of the right mid thigh (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with sea urchin spines within the superficial soft tissues of the lateral thigh.

At the time of presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient reported sharp intermittent pain localized to the right thigh. The patient denied any fever, chills, or pain in the joints. On physical examination, there were several firm nodules on the right thigh, ranging from 4 to 20 mm in diameter (Figure 2). The nodules were tender to palpation with some surrounding edema. Drainage was not noted. Several scars were visible at sites of the original puncture injuries and removal of the spines.

Two 6-mm punch biopsies were performed on representative nodules on the right thigh for histopathologic examination. Along with the biopsy tissue, firm, brown-black, linear foreign bodies consistent with sea urchin spines were extracted with forceps (Figure 3). Histopathologic examination revealed a dense, diffuse, mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis predominantly composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils. Proliferation of small vessels was noted. In one of the biopsies, small fragments of necrotic tissue were present. These findings were consistent with granulomatous inflammation and granulation tissue due to a foreign body.

At the time of suture removal 2 weeks later, the biopsied areas were well healed with minimal erythema. The patient reported decreased pain in the involved areas. He was not seen in clinic again due to resolution of the nodules and associated pain.

Comment

Sea urchin spine injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions with frequent participation in recreational and occupational water activities. A wide variety of responses can be seen in sea urchin spine injuries. There generally are 2 types of cutaneous reaction patterns to sea urchin spines: a primary initial reaction and a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction. When the spines initially penetrate the skin, the primary initial reaction consists of sharp localized pain that worsens with applied pressure. In addition to pain, bleeding, erythema, edema, and myalgia can occur.3 These symptoms typically subside a few hours after complete removal of the spines from the skin.6 If some spines remain in the skin, a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction can occur, which can lead to the formation of granulomas that can manifest as nodules or papules and can be diffuse.

Many patients may think their painful encounter with a sea urchin was just an unfortunate event, but depending on the location of the injury, more serious extracutaneous reactions and chronic symptoms may occur. Some cases have described the development of arthritis and synovitis from the implantation of spines into joints.1,2,4-6 Other extracutaneous complications include neuropathy and paresthesia, local bone destruction, radiating pain, muscular weakness, and hypotension.3

The severity of the injury also can depend on the sea urchin species and the number of spines implanted. There are approximately 80 poisonous sea urchin species possessing toxins in venomous spines, resulting in edema and change in the leukocyte-endothelial interaction.9 Substances identified in the spines include proteins, steroids, serotonin, histamine, and glycosides.3,9 The number of spines implanted, particularly the number of venomous spines, can lead to more severe complications. Penetration of 15 or more venomous spines can commonly lead to extracutaneous symptoms.3 Another concern, irrespective of species type, is the potential for secondary infection associated with the spine penetration or implantation into the skin. Mycobacterium marinum infections have been reported in some sea urchin granulomas,10 as well as fungal infection, bacterial infection, and tetanus.3

The diagnosis of sea urchin spine injuries starts with a thorough history and physical examination. A positive history of sea urchin contact suggests the diagnosis, and radiographs can be useful to find the location of the spine(s), especially if there are no visible nodules on the skin. However, small fragments of spine may not be completely observed on plain radiographs. Any signs or symptoms of infection should prompt a culture for confirmation and guidance for management. Cutaneous biopsies can be helpful for both diagnosis confirmation and symptomatic relief. Reported cases have described granulomatous reactions in the vast majority of the histologic specimens, with necrosis an additional common finding.7,8 Sea urchin granulomas can be of varying types, the majority being foreign-body and sarcoid types.3,6,7

Treatment of sea urchin spine injuries primarily involves removal of the spines by a physician. Patients may soak the affected areas in warm water prior to the removal of the spines to aid in pain relief. Surgical removal with local anesthesia and cutaneous extraction is a common treatment method, and more extensive surgical removal of the spines is another option, especially in areas around the joints.2 The use of liquid nitrogen or skin punch biopsy also have been described as possible methods to remove the spines.11,12

Conclusion

Sea urchin spine injuries can result in a wide range of cutaneous and systemic complications. Prompt diagnosis and treatment to remove the sea urchin spines can lessen the associated pain and is important in the prevention of more serious complications.

Sea urchin injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions near both warm and cold salt water with frequent recreational water activities or fishing. Sea urchins belong to the class Echinoidea with approximately 600 species, of which roughly 80 are poisonous to humans.1,2 When a human comes in contact with a sea urchin, the spines of the sea urchin (made of calcium carbonate) can penetrate the skin and break off from the sea urchin, becoming embedded in the skin. Injuries from sea urchin spines are most commonly seen on the hands and feet, as the likelihood of contact with a sea urchin is greater on these sites. The severity of sea urchin spine injuries can vary widely, from minimal local trauma and pain to arthritis, synovitis, and occasionally systemic illness.1,3 It is important to recognize the wide variety of responses to sea urchin spine injuries and the impact of prompt treatment. Many published reports on injuries from sea urchin spines describe arthritis and synovitis from spines in the joints.1,2,4-6 Fewer reports discuss nonjoint injuries and the dermatologic aspects of sea urchin spine injuries.3,7,8 We pre-sent a case of a patient with a puncture injury from sea urchin spines that resulted in painful granulomas.

Case Report

A 29-year-old otherwise healthy man was referred to our dermatology clinic by the university student health center due to continued pain in the right thigh. Five weeks prior to presentation to the student health center, the patient had fallen on a sea urchin while snorkeling in Hawaii. Sea urchin spines became lodged in the right thigh, some of which were removed in a local medical clinic in Hawaii. He was given oral antibiotics prior to his return home. A plain film radiograph of the affected area ordered by the student health center showed several punctate and linear densities in the lateral aspect of the right mid thigh (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with sea urchin spines within the superficial soft tissues of the lateral thigh.

At the time of presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient reported sharp intermittent pain localized to the right thigh. The patient denied any fever, chills, or pain in the joints. On physical examination, there were several firm nodules on the right thigh, ranging from 4 to 20 mm in diameter (Figure 2). The nodules were tender to palpation with some surrounding edema. Drainage was not noted. Several scars were visible at sites of the original puncture injuries and removal of the spines.

Two 6-mm punch biopsies were performed on representative nodules on the right thigh for histopathologic examination. Along with the biopsy tissue, firm, brown-black, linear foreign bodies consistent with sea urchin spines were extracted with forceps (Figure 3). Histopathologic examination revealed a dense, diffuse, mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis predominantly composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils. Proliferation of small vessels was noted. In one of the biopsies, small fragments of necrotic tissue were present. These findings were consistent with granulomatous inflammation and granulation tissue due to a foreign body.