User login

US-trained docs have higher patient death rate

Photo courtesy of the CDC

A large study has revealed a lower death rate among US patients treated by internationally trained doctors rather than US-trained doctors.

Researchers

analyzed data on more than 1.2 million US hospital admissions and found

a slight but statistically significant difference in 30-day mortality

for patients treated by internationally trained doctors and US-trained

doctors—11.2% and

11.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

These findings were published in The BMJ.

Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, PhD, of Harvard T H Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team wanted to determine whether patient outcomes differ between general internists who graduated from a medical school outside the US and those who graduated from a US medical school.

The researchers analyzed data on the treatment of Medicare beneficiaries (age 65 and older) who were admitted to a hospital with a medical condition from 2011 through 2014. This included 1,215,490 hospital admissions and 44,227 general internists.

The primary outcome was 30-day patient mortality. Secondary outcomes were 30-day readmission rates and costs of care.

Compared with patients treated by US graduates, patients treated by international graduates had slightly more chronic conditions.

After adjusting for factors that could have affected the results (including patient characteristics, physician characteristics, and hospital fixed effects), the researchers found that patients cared for by international graduates had a lower rate of 30-day mortality than patients cared for by US graduates (11.2% and

11.6%, respectively, P<0.001).

The researchers said that for every 250 patients treated by US medical graduates, 1 patient’s life would be saved if the quality of care were equivalent between the international graduates and US graduates.

Thirty-day readmission rates did not differ significantly between the 2 types of graduates—15.4% for international graduates and 15.5% for US graduates (P=0.54).

However, the cost of care per admission was higher for international medical graduates—$1145 vs $1098 (P<0.001).

Further analysis to test the strength of these results made no difference to the overall findings.

One possible explanation for these findings, according to the researchers, is that the current approach for allowing international medical graduates to practice in the US may select for, on average, better physicians.

The team stressed that this is an observational study, so no firm conclusions can be drawn about cause and effect. Nevertheless, they said their findings “should reassure policymakers and the public that our current approach to licensing international medical graduates in the US is sufficiently rigorous to ensure high quality care.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

A large study has revealed a lower death rate among US patients treated by internationally trained doctors rather than US-trained doctors.

Researchers

analyzed data on more than 1.2 million US hospital admissions and found

a slight but statistically significant difference in 30-day mortality

for patients treated by internationally trained doctors and US-trained

doctors—11.2% and

11.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

These findings were published in The BMJ.

Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, PhD, of Harvard T H Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team wanted to determine whether patient outcomes differ between general internists who graduated from a medical school outside the US and those who graduated from a US medical school.

The researchers analyzed data on the treatment of Medicare beneficiaries (age 65 and older) who were admitted to a hospital with a medical condition from 2011 through 2014. This included 1,215,490 hospital admissions and 44,227 general internists.

The primary outcome was 30-day patient mortality. Secondary outcomes were 30-day readmission rates and costs of care.

Compared with patients treated by US graduates, patients treated by international graduates had slightly more chronic conditions.

After adjusting for factors that could have affected the results (including patient characteristics, physician characteristics, and hospital fixed effects), the researchers found that patients cared for by international graduates had a lower rate of 30-day mortality than patients cared for by US graduates (11.2% and

11.6%, respectively, P<0.001).

The researchers said that for every 250 patients treated by US medical graduates, 1 patient’s life would be saved if the quality of care were equivalent between the international graduates and US graduates.

Thirty-day readmission rates did not differ significantly between the 2 types of graduates—15.4% for international graduates and 15.5% for US graduates (P=0.54).

However, the cost of care per admission was higher for international medical graduates—$1145 vs $1098 (P<0.001).

Further analysis to test the strength of these results made no difference to the overall findings.

One possible explanation for these findings, according to the researchers, is that the current approach for allowing international medical graduates to practice in the US may select for, on average, better physicians.

The team stressed that this is an observational study, so no firm conclusions can be drawn about cause and effect. Nevertheless, they said their findings “should reassure policymakers and the public that our current approach to licensing international medical graduates in the US is sufficiently rigorous to ensure high quality care.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

A large study has revealed a lower death rate among US patients treated by internationally trained doctors rather than US-trained doctors.

Researchers

analyzed data on more than 1.2 million US hospital admissions and found

a slight but statistically significant difference in 30-day mortality

for patients treated by internationally trained doctors and US-trained

doctors—11.2% and

11.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

These findings were published in The BMJ.

Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, PhD, of Harvard T H Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team wanted to determine whether patient outcomes differ between general internists who graduated from a medical school outside the US and those who graduated from a US medical school.

The researchers analyzed data on the treatment of Medicare beneficiaries (age 65 and older) who were admitted to a hospital with a medical condition from 2011 through 2014. This included 1,215,490 hospital admissions and 44,227 general internists.

The primary outcome was 30-day patient mortality. Secondary outcomes were 30-day readmission rates and costs of care.

Compared with patients treated by US graduates, patients treated by international graduates had slightly more chronic conditions.

After adjusting for factors that could have affected the results (including patient characteristics, physician characteristics, and hospital fixed effects), the researchers found that patients cared for by international graduates had a lower rate of 30-day mortality than patients cared for by US graduates (11.2% and

11.6%, respectively, P<0.001).

The researchers said that for every 250 patients treated by US medical graduates, 1 patient’s life would be saved if the quality of care were equivalent between the international graduates and US graduates.

Thirty-day readmission rates did not differ significantly between the 2 types of graduates—15.4% for international graduates and 15.5% for US graduates (P=0.54).

However, the cost of care per admission was higher for international medical graduates—$1145 vs $1098 (P<0.001).

Further analysis to test the strength of these results made no difference to the overall findings.

One possible explanation for these findings, according to the researchers, is that the current approach for allowing international medical graduates to practice in the US may select for, on average, better physicians.

The team stressed that this is an observational study, so no firm conclusions can be drawn about cause and effect. Nevertheless, they said their findings “should reassure policymakers and the public that our current approach to licensing international medical graduates in the US is sufficiently rigorous to ensure high quality care.” ![]()

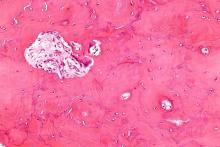

Sickle cell trait may confound blood sugar readings

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

A new study suggests that hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a biomarker used to measure blood sugar over time, may not perform as accurately among African-Americans with sickle cell trait (SCT) and could be leading to a systemic underestimation of blood sugar control in that population.

Researchers analyzed data from more than 4600 people and found that HbA1c readings were significantly lower in individuals with SCT than in those without it, even after accounting for several possible confounding factors.

The team reported these findings in JAMA.

“We found that HbA1c was systematically lower in African-Americans with sickle cell trait than those without sickle cell trait, despite similar blood sugar measurements using other tests,” said study author Mary Lacy, a doctoral candidate at the Brown University School of Public Health in Providence, Rhode Island.

“We might be missing an opportunity for diagnosis and treatment of a serious disease.”

Lacy and her co-authors found that using standard clinical HbA1c cutoffs resulted in identifying 40% fewer potential cases of prediabetes and 48% fewer potential cases of diabetes in people with SCT than in people without SCT.

However, when the researchers used other blood glucose measures as the diagnostic criteria, they found no significant difference in the likelihood of diabetes and prediabetes among patients with or without SCT.

The questions the study raises about using HbA1c among SCT carriers matter for treatment as well as diagnosis, said study author Wen-Chih Wu, MD, of Brown University.

“The clinical implications of these results are highly relevant,” Dr Wu said. “For patients with diabetes, HbA1c is often used as a marker of how well they are managing their diabetes, so having an underestimation of their blood sugars is problematic because they might have a false sense of security, thinking they are doing okay when they are not.”

Study details

For this study, the researchers analyzed data from 2 major public health studies—the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study and the Jackson Heart Study (JHS). Of the 4620 participants included in the analysis, 367 had SCT.

Among all the patients included in the analysis, HbA1c readings came from either of 2 widely used, clinically accepted assays made by Tosoh Bioscience Inc. that rely on a process called high-performance liquid chromatography.

In addition to those measures, the researchers also compared fasting and 2-hour blood glucose and statistically controlled for demographic and medical factors, such as gender, age, body-mass index, whether diabetes had already been diagnosed, and whether it was being treated.

Study author Gregory Wellenius, ScD, of Brown University, said the study’s scale and breadth allowed for the most definitive comparison to date of HbA1c readings in patients with and without SCT. Two previous, smaller studies had not detected a similar discrepancy.

“The strengths of the study are that it’s the largest sample size ever used, it’s across 2 different studies with somewhat different populations, and it’s a more thorough evaluation than prior studies,” Dr Wellenius said.

While the study showed that HbA1c readings were significantly different between people with and without SCT, it also showed that blood glucose readings were not, suggesting that glucose metabolism is not necessarily different between the 2 groups, as the HbA1c readings alone would suggest.

Implications for practice

The study does not explain why the HbA1c readings differ. While it could be related to the assay method, which is approved by the NGSP (formerly National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program) for use in patients with SCT, it could also be a consequence of the underlying biology of SCT.

Hypothetically, according to the researchers, if the hemoglobin variant of the trait endows red blood cells with a shorter lifespan, the cells’ hemoglobin would carry less accumulated blood glucose, leading to falsely low HbA1c readings.

“Irrespective of the reason of the underestimation, the underestimation is very real, and clinicians should consider screening for sickle cell trait and account for the difference in HbA1c,” Dr Wu said.

Yet not many people with SCT in the US know they carry the variant, especially those born before routine screenings at birth began, Lacy said.

The researchers therefore recommend that practitioners following African-American patients whose HbA1c levels are within 0.3 percentage points of a diagnostic cutoff also consider using additional blood glucose measures. Current diagnostic thresholds for A1C are ≥5.7% for prediabetes and ≥6.5% for diabetes. ![]()

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

A new study suggests that hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a biomarker used to measure blood sugar over time, may not perform as accurately among African-Americans with sickle cell trait (SCT) and could be leading to a systemic underestimation of blood sugar control in that population.

Researchers analyzed data from more than 4600 people and found that HbA1c readings were significantly lower in individuals with SCT than in those without it, even after accounting for several possible confounding factors.

The team reported these findings in JAMA.

“We found that HbA1c was systematically lower in African-Americans with sickle cell trait than those without sickle cell trait, despite similar blood sugar measurements using other tests,” said study author Mary Lacy, a doctoral candidate at the Brown University School of Public Health in Providence, Rhode Island.

“We might be missing an opportunity for diagnosis and treatment of a serious disease.”

Lacy and her co-authors found that using standard clinical HbA1c cutoffs resulted in identifying 40% fewer potential cases of prediabetes and 48% fewer potential cases of diabetes in people with SCT than in people without SCT.

However, when the researchers used other blood glucose measures as the diagnostic criteria, they found no significant difference in the likelihood of diabetes and prediabetes among patients with or without SCT.

The questions the study raises about using HbA1c among SCT carriers matter for treatment as well as diagnosis, said study author Wen-Chih Wu, MD, of Brown University.

“The clinical implications of these results are highly relevant,” Dr Wu said. “For patients with diabetes, HbA1c is often used as a marker of how well they are managing their diabetes, so having an underestimation of their blood sugars is problematic because they might have a false sense of security, thinking they are doing okay when they are not.”

Study details

For this study, the researchers analyzed data from 2 major public health studies—the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study and the Jackson Heart Study (JHS). Of the 4620 participants included in the analysis, 367 had SCT.

Among all the patients included in the analysis, HbA1c readings came from either of 2 widely used, clinically accepted assays made by Tosoh Bioscience Inc. that rely on a process called high-performance liquid chromatography.

In addition to those measures, the researchers also compared fasting and 2-hour blood glucose and statistically controlled for demographic and medical factors, such as gender, age, body-mass index, whether diabetes had already been diagnosed, and whether it was being treated.

Study author Gregory Wellenius, ScD, of Brown University, said the study’s scale and breadth allowed for the most definitive comparison to date of HbA1c readings in patients with and without SCT. Two previous, smaller studies had not detected a similar discrepancy.

“The strengths of the study are that it’s the largest sample size ever used, it’s across 2 different studies with somewhat different populations, and it’s a more thorough evaluation than prior studies,” Dr Wellenius said.

While the study showed that HbA1c readings were significantly different between people with and without SCT, it also showed that blood glucose readings were not, suggesting that glucose metabolism is not necessarily different between the 2 groups, as the HbA1c readings alone would suggest.

Implications for practice

The study does not explain why the HbA1c readings differ. While it could be related to the assay method, which is approved by the NGSP (formerly National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program) for use in patients with SCT, it could also be a consequence of the underlying biology of SCT.

Hypothetically, according to the researchers, if the hemoglobin variant of the trait endows red blood cells with a shorter lifespan, the cells’ hemoglobin would carry less accumulated blood glucose, leading to falsely low HbA1c readings.

“Irrespective of the reason of the underestimation, the underestimation is very real, and clinicians should consider screening for sickle cell trait and account for the difference in HbA1c,” Dr Wu said.

Yet not many people with SCT in the US know they carry the variant, especially those born before routine screenings at birth began, Lacy said.

The researchers therefore recommend that practitioners following African-American patients whose HbA1c levels are within 0.3 percentage points of a diagnostic cutoff also consider using additional blood glucose measures. Current diagnostic thresholds for A1C are ≥5.7% for prediabetes and ≥6.5% for diabetes. ![]()

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

A new study suggests that hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a biomarker used to measure blood sugar over time, may not perform as accurately among African-Americans with sickle cell trait (SCT) and could be leading to a systemic underestimation of blood sugar control in that population.

Researchers analyzed data from more than 4600 people and found that HbA1c readings were significantly lower in individuals with SCT than in those without it, even after accounting for several possible confounding factors.

The team reported these findings in JAMA.

“We found that HbA1c was systematically lower in African-Americans with sickle cell trait than those without sickle cell trait, despite similar blood sugar measurements using other tests,” said study author Mary Lacy, a doctoral candidate at the Brown University School of Public Health in Providence, Rhode Island.

“We might be missing an opportunity for diagnosis and treatment of a serious disease.”

Lacy and her co-authors found that using standard clinical HbA1c cutoffs resulted in identifying 40% fewer potential cases of prediabetes and 48% fewer potential cases of diabetes in people with SCT than in people without SCT.

However, when the researchers used other blood glucose measures as the diagnostic criteria, they found no significant difference in the likelihood of diabetes and prediabetes among patients with or without SCT.

The questions the study raises about using HbA1c among SCT carriers matter for treatment as well as diagnosis, said study author Wen-Chih Wu, MD, of Brown University.

“The clinical implications of these results are highly relevant,” Dr Wu said. “For patients with diabetes, HbA1c is often used as a marker of how well they are managing their diabetes, so having an underestimation of their blood sugars is problematic because they might have a false sense of security, thinking they are doing okay when they are not.”

Study details

For this study, the researchers analyzed data from 2 major public health studies—the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study and the Jackson Heart Study (JHS). Of the 4620 participants included in the analysis, 367 had SCT.

Among all the patients included in the analysis, HbA1c readings came from either of 2 widely used, clinically accepted assays made by Tosoh Bioscience Inc. that rely on a process called high-performance liquid chromatography.

In addition to those measures, the researchers also compared fasting and 2-hour blood glucose and statistically controlled for demographic and medical factors, such as gender, age, body-mass index, whether diabetes had already been diagnosed, and whether it was being treated.

Study author Gregory Wellenius, ScD, of Brown University, said the study’s scale and breadth allowed for the most definitive comparison to date of HbA1c readings in patients with and without SCT. Two previous, smaller studies had not detected a similar discrepancy.

“The strengths of the study are that it’s the largest sample size ever used, it’s across 2 different studies with somewhat different populations, and it’s a more thorough evaluation than prior studies,” Dr Wellenius said.

While the study showed that HbA1c readings were significantly different between people with and without SCT, it also showed that blood glucose readings were not, suggesting that glucose metabolism is not necessarily different between the 2 groups, as the HbA1c readings alone would suggest.

Implications for practice

The study does not explain why the HbA1c readings differ. While it could be related to the assay method, which is approved by the NGSP (formerly National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program) for use in patients with SCT, it could also be a consequence of the underlying biology of SCT.

Hypothetically, according to the researchers, if the hemoglobin variant of the trait endows red blood cells with a shorter lifespan, the cells’ hemoglobin would carry less accumulated blood glucose, leading to falsely low HbA1c readings.

“Irrespective of the reason of the underestimation, the underestimation is very real, and clinicians should consider screening for sickle cell trait and account for the difference in HbA1c,” Dr Wu said.

Yet not many people with SCT in the US know they carry the variant, especially those born before routine screenings at birth began, Lacy said.

The researchers therefore recommend that practitioners following African-American patients whose HbA1c levels are within 0.3 percentage points of a diagnostic cutoff also consider using additional blood glucose measures. Current diagnostic thresholds for A1C are ≥5.7% for prediabetes and ≥6.5% for diabetes. ![]()

‘Alternative’ BMT deemed ‘promising’ for SAA

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Researchers have reported a “promising” treatment approach for

refractory, severe aplastic anemia (SAA).

The

regimen consists of nonmyeloablative conditioning, bone marrow

transplants (BMTs) from “alternative” donors, and graft-vs-host disease

(GVHD) prophylaxis.

All 16 SAA patients who received this treatment

achieved engraftment and were completely cleared of disease.

There were 2 cases of acute and chronic GVHD, but they resolved.

All patients were ultimately able to stop immunosuppressive therapy.

Robert Brodsky, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues reported these findings in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“Our findings have the potential to greatly widen treatment options for the vast majority of severe aplastic anemia patients,” Dr Brodsky said.

He and his colleagues tested their approach in 16 SAA patients between 11 and 69 years of age. Each of the patients had failed to respond to immunosuppressive therapy and other treatments.

The patients received conditioning with antithymocyte globulin, fludarabine, low-dose cyclophosphamide, and total body irradiation.

They then received BMTs. Thirteen of the donors were haploidentical related, 2 were fully matched unrelated, and 1 was mismatched unrelated.

Three and 4 days after BMT, the patients received cyclophosphamide at 50 mg/kg/day as GVHD prophylaxis. They then received mycophenolate mofetil on days 5 through 35 and tacrolimus from day 5 through 1 year.

The median time to neutrophil recovery (over 1000 × 103/mm3 for 3 consecutive days) was 19 days (range, 16 to 27). The median time to red cell engraftment was 25 days (range, 2 to 58). And the median time to the last platelet transfusion (to keep platelet counts over 50 × 103/mm3) was 27.5 days (range, 22 to 108).

At a median follow-up of 21 months (range, 3 to 64), all 16 patients were still alive, disease-free, and no longer required transfusions.

Two patients did develop grade 1/2 acute skin GVHD. They also had mild chronic GVHD of the skin/mouth, which required systemic steroids.

One of these patients was able to come off all immunosuppressive therapy by 15 months, and the other was able to do so by 17 months. All of the other patients stopped immunosuppressive therapy at 1 year.

Ending all therapy related to their disease has been life-changing for these patients, said study author Amy DeZern, MD, also of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center.

“It’s like night and day,” she said. “They go from not knowing if they have a future to hoping for what they’d hoped for before they got sick. It’s that transformative.”

Successful BMTs using partially matched donors open up the transplant option to nearly all patients with SAA, especially minority patients, added Dr Brodsky.

“Now, a therapy that used to be available to 25% to 30% of patients with severe aplastic anemia is potentially available to more than 95%,” he said. ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Researchers have reported a “promising” treatment approach for

refractory, severe aplastic anemia (SAA).

The

regimen consists of nonmyeloablative conditioning, bone marrow

transplants (BMTs) from “alternative” donors, and graft-vs-host disease

(GVHD) prophylaxis.

All 16 SAA patients who received this treatment

achieved engraftment and were completely cleared of disease.

There were 2 cases of acute and chronic GVHD, but they resolved.

All patients were ultimately able to stop immunosuppressive therapy.

Robert Brodsky, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues reported these findings in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“Our findings have the potential to greatly widen treatment options for the vast majority of severe aplastic anemia patients,” Dr Brodsky said.

He and his colleagues tested their approach in 16 SAA patients between 11 and 69 years of age. Each of the patients had failed to respond to immunosuppressive therapy and other treatments.

The patients received conditioning with antithymocyte globulin, fludarabine, low-dose cyclophosphamide, and total body irradiation.

They then received BMTs. Thirteen of the donors were haploidentical related, 2 were fully matched unrelated, and 1 was mismatched unrelated.

Three and 4 days after BMT, the patients received cyclophosphamide at 50 mg/kg/day as GVHD prophylaxis. They then received mycophenolate mofetil on days 5 through 35 and tacrolimus from day 5 through 1 year.

The median time to neutrophil recovery (over 1000 × 103/mm3 for 3 consecutive days) was 19 days (range, 16 to 27). The median time to red cell engraftment was 25 days (range, 2 to 58). And the median time to the last platelet transfusion (to keep platelet counts over 50 × 103/mm3) was 27.5 days (range, 22 to 108).

At a median follow-up of 21 months (range, 3 to 64), all 16 patients were still alive, disease-free, and no longer required transfusions.

Two patients did develop grade 1/2 acute skin GVHD. They also had mild chronic GVHD of the skin/mouth, which required systemic steroids.

One of these patients was able to come off all immunosuppressive therapy by 15 months, and the other was able to do so by 17 months. All of the other patients stopped immunosuppressive therapy at 1 year.

Ending all therapy related to their disease has been life-changing for these patients, said study author Amy DeZern, MD, also of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center.

“It’s like night and day,” she said. “They go from not knowing if they have a future to hoping for what they’d hoped for before they got sick. It’s that transformative.”

Successful BMTs using partially matched donors open up the transplant option to nearly all patients with SAA, especially minority patients, added Dr Brodsky.

“Now, a therapy that used to be available to 25% to 30% of patients with severe aplastic anemia is potentially available to more than 95%,” he said. ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Researchers have reported a “promising” treatment approach for

refractory, severe aplastic anemia (SAA).

The

regimen consists of nonmyeloablative conditioning, bone marrow

transplants (BMTs) from “alternative” donors, and graft-vs-host disease

(GVHD) prophylaxis.

All 16 SAA patients who received this treatment

achieved engraftment and were completely cleared of disease.

There were 2 cases of acute and chronic GVHD, but they resolved.

All patients were ultimately able to stop immunosuppressive therapy.

Robert Brodsky, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues reported these findings in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“Our findings have the potential to greatly widen treatment options for the vast majority of severe aplastic anemia patients,” Dr Brodsky said.

He and his colleagues tested their approach in 16 SAA patients between 11 and 69 years of age. Each of the patients had failed to respond to immunosuppressive therapy and other treatments.

The patients received conditioning with antithymocyte globulin, fludarabine, low-dose cyclophosphamide, and total body irradiation.

They then received BMTs. Thirteen of the donors were haploidentical related, 2 were fully matched unrelated, and 1 was mismatched unrelated.

Three and 4 days after BMT, the patients received cyclophosphamide at 50 mg/kg/day as GVHD prophylaxis. They then received mycophenolate mofetil on days 5 through 35 and tacrolimus from day 5 through 1 year.

The median time to neutrophil recovery (over 1000 × 103/mm3 for 3 consecutive days) was 19 days (range, 16 to 27). The median time to red cell engraftment was 25 days (range, 2 to 58). And the median time to the last platelet transfusion (to keep platelet counts over 50 × 103/mm3) was 27.5 days (range, 22 to 108).

At a median follow-up of 21 months (range, 3 to 64), all 16 patients were still alive, disease-free, and no longer required transfusions.

Two patients did develop grade 1/2 acute skin GVHD. They also had mild chronic GVHD of the skin/mouth, which required systemic steroids.

One of these patients was able to come off all immunosuppressive therapy by 15 months, and the other was able to do so by 17 months. All of the other patients stopped immunosuppressive therapy at 1 year.

Ending all therapy related to their disease has been life-changing for these patients, said study author Amy DeZern, MD, also of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center.

“It’s like night and day,” she said. “They go from not knowing if they have a future to hoping for what they’d hoped for before they got sick. It’s that transformative.”

Successful BMTs using partially matched donors open up the transplant option to nearly all patients with SAA, especially minority patients, added Dr Brodsky.

“Now, a therapy that used to be available to 25% to 30% of patients with severe aplastic anemia is potentially available to more than 95%,” he said. ![]()

Food Insecurity Among Veterans

Nearly half of a group of homeless and formerly homeless veterans reported experiencing food insecurity, according to VA researchers. More than one-quarter of those said they’d averaged only 1 meal a day.

Researchers screened 270 new patients who enrolled in 1 of 6 VA primary care clinics. Screening began with a single question: “In the past month, were there times when the food for you just did not last, and there was no money to buy more?” Patients who answered yes were then asked where they got their food, how many meals per day they ate, whether they prepared their meals, whether they received food stamps, whether they had diabetes, and whether they had symptoms of hypoglycemia.

Of the respondents, 63% were living in their own apartment, and 26% were in a transitional housing program where they were responsible for some of their meals. Of the patients who reported food insecurity, 87% prepared their meals, with half relying on food they bought, 23% on food from soup kitchens and food pantries, 15% from shelters, 19% from family and friends. About half (47%) were receiving food stamps.

One-fifth of the patients had diabetes or prediabetes, and 44% reported hypoglycemia symptoms when without food. The researchers point out that the consequences of food insecurity are “significant and potentially life threatening.” They cite another study that found risk for hospital admissions for hypoglycemia rose 27% in the last week of the month among low-income populations, typically when food stamps and supplies at food pantries ran low or were exhausted.

The study revealed that asking about only food insecurity was not enough, the researchers say. “The additional context provided by the follow-up questions and the breadth of different responses underscored that the needs of these patients extend beyond those available from 1 health care provider or 1 health care discipline.”

Both patients and health care providers endorsed the screening program. One staff member, for instance, called the program a good rapport builder. No team found the questions burdensome, the researchers say. In fact,4 teams said the follow-up questions highlighted the complexity of issues underlying food insecurity and the need for a well-integrated, multidisciplinary approach to the problem.

Nearly half of a group of homeless and formerly homeless veterans reported experiencing food insecurity, according to VA researchers. More than one-quarter of those said they’d averaged only 1 meal a day.

Researchers screened 270 new patients who enrolled in 1 of 6 VA primary care clinics. Screening began with a single question: “In the past month, were there times when the food for you just did not last, and there was no money to buy more?” Patients who answered yes were then asked where they got their food, how many meals per day they ate, whether they prepared their meals, whether they received food stamps, whether they had diabetes, and whether they had symptoms of hypoglycemia.

Of the respondents, 63% were living in their own apartment, and 26% were in a transitional housing program where they were responsible for some of their meals. Of the patients who reported food insecurity, 87% prepared their meals, with half relying on food they bought, 23% on food from soup kitchens and food pantries, 15% from shelters, 19% from family and friends. About half (47%) were receiving food stamps.

One-fifth of the patients had diabetes or prediabetes, and 44% reported hypoglycemia symptoms when without food. The researchers point out that the consequences of food insecurity are “significant and potentially life threatening.” They cite another study that found risk for hospital admissions for hypoglycemia rose 27% in the last week of the month among low-income populations, typically when food stamps and supplies at food pantries ran low or were exhausted.

The study revealed that asking about only food insecurity was not enough, the researchers say. “The additional context provided by the follow-up questions and the breadth of different responses underscored that the needs of these patients extend beyond those available from 1 health care provider or 1 health care discipline.”

Both patients and health care providers endorsed the screening program. One staff member, for instance, called the program a good rapport builder. No team found the questions burdensome, the researchers say. In fact,4 teams said the follow-up questions highlighted the complexity of issues underlying food insecurity and the need for a well-integrated, multidisciplinary approach to the problem.

Nearly half of a group of homeless and formerly homeless veterans reported experiencing food insecurity, according to VA researchers. More than one-quarter of those said they’d averaged only 1 meal a day.

Researchers screened 270 new patients who enrolled in 1 of 6 VA primary care clinics. Screening began with a single question: “In the past month, were there times when the food for you just did not last, and there was no money to buy more?” Patients who answered yes were then asked where they got their food, how many meals per day they ate, whether they prepared their meals, whether they received food stamps, whether they had diabetes, and whether they had symptoms of hypoglycemia.

Of the respondents, 63% were living in their own apartment, and 26% were in a transitional housing program where they were responsible for some of their meals. Of the patients who reported food insecurity, 87% prepared their meals, with half relying on food they bought, 23% on food from soup kitchens and food pantries, 15% from shelters, 19% from family and friends. About half (47%) were receiving food stamps.

One-fifth of the patients had diabetes or prediabetes, and 44% reported hypoglycemia symptoms when without food. The researchers point out that the consequences of food insecurity are “significant and potentially life threatening.” They cite another study that found risk for hospital admissions for hypoglycemia rose 27% in the last week of the month among low-income populations, typically when food stamps and supplies at food pantries ran low or were exhausted.

The study revealed that asking about only food insecurity was not enough, the researchers say. “The additional context provided by the follow-up questions and the breadth of different responses underscored that the needs of these patients extend beyond those available from 1 health care provider or 1 health care discipline.”

Both patients and health care providers endorsed the screening program. One staff member, for instance, called the program a good rapport builder. No team found the questions burdensome, the researchers say. In fact,4 teams said the follow-up questions highlighted the complexity of issues underlying food insecurity and the need for a well-integrated, multidisciplinary approach to the problem.

Targeting Paget’s bone symptoms supported in long-term trial

Long-term intensive bisphosphonate treatment of patients with Paget’s disease of bone continued to show no benefit over symptomatic treatment in a 3-year extension trial of the PRISM study, leading investigators in the trial to recommend that treatment guidelines focus more on managing the condition’s symptoms rather than normalizing bone turnover biomarkers in hope of reducing disease complications.

“The Paget’s Disease Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Symptomatic Management (PRISM) study showed that intensive bisphosphonate therapy and symptomatic treatment had similar effects on clinical outcome of PDB [Paget’s disease of bone] with respect to the occurrence of fractures, orthopedic procedures, hearing loss, bone pain, quality of life, and adverse events,” wrote the principal investigator of the PRISM-EZ (extension with zoledronic acid) phase of the trial, Stuart H. Ralston, MD, of the University of Edinburgh (Scotland), and his colleagues.

Enrollment in the extension trial, which occurred during January 2007-January 2012, meant that patients kept to the same treatment strategies except for those in the intensive arm, who switched to zoledronic acid as the treatment of first choice. Both groups received analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed. Patients in the symptomatic arm received bisphosphonate treatment only if they had bone pain thought to be caused by the increased metabolic activity of PDB, whereas those in the intensive arm were prescribed “bisphosphonates as required to suppress and maintain ALP [alkaline phosphatase] concentrations within the normal range,” according to the investigators. Clinical fracture rate was the primary outcome, but Dr. Ralston and his colleagues also compared orthopedic procedures, serum total ALP concentrations, bone pain, and quality of life in both cohorts.

A higher proportion of patients in the intensive group received zoledronic acid than in the symptomatic group (28.1% vs. 10.3%; P less than .001), whereas fewer patients in the intensive group received pamidronate (4.8% vs. 15.5%; P less than .001).

Of 270 in the intensive cohort, 22 (8.1%) experienced fractures, versus 12 (5.2%) of the 232 in the symptomatic cohort, yielding a hazard ratio of 1.90 (95% confidence interval, 0.91-3.98; P = .087). Of those, fractures in the pagetic bone numbered five and two, respectively. A total of 15 (5.6%) intensive treatment subjects and 7 (3.0%) symptomatic treatment subjects required orthopedic surgery, with a hazard ratio of 1.81 (95% CI, 0.71-4.61; P = .214).

There were no differences in bodily pain, bone pain, or quality of life at year 3 as reported by patients in both cohorts. While there was a statistically significant difference between intensive and symptomatic treatment in bodily pain, physical component summary score, and arthritis-specific health index scores at year 1 of the trial, the investigators noted that the findings were below the clinically significant five-point threshold and did not persist beyond 1 year.

“The results reported here do not support the recommendations made by the Endocrine Society guideline group, which suggested that most patients with PDB should be treated with potent bisphosphonates with the aim of restoring ALP values to within the lower part of the reference range,” the authors concluded. “On the contrary, the PRISM-EZ study demonstrates that this strategy is not associated with clinical benefit and might be harmful, [so] a more appropriate indication for bisphosphonate treatment in PDB is to control bone pain thought to be due to disease activity.”

The study was funded by grants from Arthritis Research UK and the Paget’s Association. Dr. Ralston reported receiving consultancy fees on behalf of his institution from Novartis and Merck and grant support on behalf of his institution from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and UCB. One coauthor reported receiving consultancy fees from Siemens, Becton Dickinson, and Roche, and another disclosed receiving such fees from Internis.

The PRISM-EZ study is the largest and longest study of PDB and provides important information on its long-term management. The results need to be kept in perspective. All patients were treated; hence, there is no untreated group and the results apply to follow-up therapy only. In this group, repeat therapy for active PDB as measured from serum total alkaline phosphatase (ALP) versus therapy for symptoms did not make a difference in a 3-year follow-up, and the authors recommend treating only when symptoms warrant it. Longer follow-ups would be needed to definitively show a difference in a condition that is present for many years.

Roy D. Altman, MD , is professor emeritus of medicine in the division of rheumatology and immunology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He has no relevant disclosures.

The PRISM-EZ study is the largest and longest study of PDB and provides important information on its long-term management. The results need to be kept in perspective. All patients were treated; hence, there is no untreated group and the results apply to follow-up therapy only. In this group, repeat therapy for active PDB as measured from serum total alkaline phosphatase (ALP) versus therapy for symptoms did not make a difference in a 3-year follow-up, and the authors recommend treating only when symptoms warrant it. Longer follow-ups would be needed to definitively show a difference in a condition that is present for many years.

Roy D. Altman, MD , is professor emeritus of medicine in the division of rheumatology and immunology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He has no relevant disclosures.

The PRISM-EZ study is the largest and longest study of PDB and provides important information on its long-term management. The results need to be kept in perspective. All patients were treated; hence, there is no untreated group and the results apply to follow-up therapy only. In this group, repeat therapy for active PDB as measured from serum total alkaline phosphatase (ALP) versus therapy for symptoms did not make a difference in a 3-year follow-up, and the authors recommend treating only when symptoms warrant it. Longer follow-ups would be needed to definitively show a difference in a condition that is present for many years.

Roy D. Altman, MD , is professor emeritus of medicine in the division of rheumatology and immunology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He has no relevant disclosures.

Long-term intensive bisphosphonate treatment of patients with Paget’s disease of bone continued to show no benefit over symptomatic treatment in a 3-year extension trial of the PRISM study, leading investigators in the trial to recommend that treatment guidelines focus more on managing the condition’s symptoms rather than normalizing bone turnover biomarkers in hope of reducing disease complications.

“The Paget’s Disease Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Symptomatic Management (PRISM) study showed that intensive bisphosphonate therapy and symptomatic treatment had similar effects on clinical outcome of PDB [Paget’s disease of bone] with respect to the occurrence of fractures, orthopedic procedures, hearing loss, bone pain, quality of life, and adverse events,” wrote the principal investigator of the PRISM-EZ (extension with zoledronic acid) phase of the trial, Stuart H. Ralston, MD, of the University of Edinburgh (Scotland), and his colleagues.

Enrollment in the extension trial, which occurred during January 2007-January 2012, meant that patients kept to the same treatment strategies except for those in the intensive arm, who switched to zoledronic acid as the treatment of first choice. Both groups received analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed. Patients in the symptomatic arm received bisphosphonate treatment only if they had bone pain thought to be caused by the increased metabolic activity of PDB, whereas those in the intensive arm were prescribed “bisphosphonates as required to suppress and maintain ALP [alkaline phosphatase] concentrations within the normal range,” according to the investigators. Clinical fracture rate was the primary outcome, but Dr. Ralston and his colleagues also compared orthopedic procedures, serum total ALP concentrations, bone pain, and quality of life in both cohorts.

A higher proportion of patients in the intensive group received zoledronic acid than in the symptomatic group (28.1% vs. 10.3%; P less than .001), whereas fewer patients in the intensive group received pamidronate (4.8% vs. 15.5%; P less than .001).

Of 270 in the intensive cohort, 22 (8.1%) experienced fractures, versus 12 (5.2%) of the 232 in the symptomatic cohort, yielding a hazard ratio of 1.90 (95% confidence interval, 0.91-3.98; P = .087). Of those, fractures in the pagetic bone numbered five and two, respectively. A total of 15 (5.6%) intensive treatment subjects and 7 (3.0%) symptomatic treatment subjects required orthopedic surgery, with a hazard ratio of 1.81 (95% CI, 0.71-4.61; P = .214).

There were no differences in bodily pain, bone pain, or quality of life at year 3 as reported by patients in both cohorts. While there was a statistically significant difference between intensive and symptomatic treatment in bodily pain, physical component summary score, and arthritis-specific health index scores at year 1 of the trial, the investigators noted that the findings were below the clinically significant five-point threshold and did not persist beyond 1 year.

“The results reported here do not support the recommendations made by the Endocrine Society guideline group, which suggested that most patients with PDB should be treated with potent bisphosphonates with the aim of restoring ALP values to within the lower part of the reference range,” the authors concluded. “On the contrary, the PRISM-EZ study demonstrates that this strategy is not associated with clinical benefit and might be harmful, [so] a more appropriate indication for bisphosphonate treatment in PDB is to control bone pain thought to be due to disease activity.”

The study was funded by grants from Arthritis Research UK and the Paget’s Association. Dr. Ralston reported receiving consultancy fees on behalf of his institution from Novartis and Merck and grant support on behalf of his institution from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and UCB. One coauthor reported receiving consultancy fees from Siemens, Becton Dickinson, and Roche, and another disclosed receiving such fees from Internis.

Long-term intensive bisphosphonate treatment of patients with Paget’s disease of bone continued to show no benefit over symptomatic treatment in a 3-year extension trial of the PRISM study, leading investigators in the trial to recommend that treatment guidelines focus more on managing the condition’s symptoms rather than normalizing bone turnover biomarkers in hope of reducing disease complications.

“The Paget’s Disease Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Symptomatic Management (PRISM) study showed that intensive bisphosphonate therapy and symptomatic treatment had similar effects on clinical outcome of PDB [Paget’s disease of bone] with respect to the occurrence of fractures, orthopedic procedures, hearing loss, bone pain, quality of life, and adverse events,” wrote the principal investigator of the PRISM-EZ (extension with zoledronic acid) phase of the trial, Stuart H. Ralston, MD, of the University of Edinburgh (Scotland), and his colleagues.

Enrollment in the extension trial, which occurred during January 2007-January 2012, meant that patients kept to the same treatment strategies except for those in the intensive arm, who switched to zoledronic acid as the treatment of first choice. Both groups received analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed. Patients in the symptomatic arm received bisphosphonate treatment only if they had bone pain thought to be caused by the increased metabolic activity of PDB, whereas those in the intensive arm were prescribed “bisphosphonates as required to suppress and maintain ALP [alkaline phosphatase] concentrations within the normal range,” according to the investigators. Clinical fracture rate was the primary outcome, but Dr. Ralston and his colleagues also compared orthopedic procedures, serum total ALP concentrations, bone pain, and quality of life in both cohorts.

A higher proportion of patients in the intensive group received zoledronic acid than in the symptomatic group (28.1% vs. 10.3%; P less than .001), whereas fewer patients in the intensive group received pamidronate (4.8% vs. 15.5%; P less than .001).

Of 270 in the intensive cohort, 22 (8.1%) experienced fractures, versus 12 (5.2%) of the 232 in the symptomatic cohort, yielding a hazard ratio of 1.90 (95% confidence interval, 0.91-3.98; P = .087). Of those, fractures in the pagetic bone numbered five and two, respectively. A total of 15 (5.6%) intensive treatment subjects and 7 (3.0%) symptomatic treatment subjects required orthopedic surgery, with a hazard ratio of 1.81 (95% CI, 0.71-4.61; P = .214).

There were no differences in bodily pain, bone pain, or quality of life at year 3 as reported by patients in both cohorts. While there was a statistically significant difference between intensive and symptomatic treatment in bodily pain, physical component summary score, and arthritis-specific health index scores at year 1 of the trial, the investigators noted that the findings were below the clinically significant five-point threshold and did not persist beyond 1 year.

“The results reported here do not support the recommendations made by the Endocrine Society guideline group, which suggested that most patients with PDB should be treated with potent bisphosphonates with the aim of restoring ALP values to within the lower part of the reference range,” the authors concluded. “On the contrary, the PRISM-EZ study demonstrates that this strategy is not associated with clinical benefit and might be harmful, [so] a more appropriate indication for bisphosphonate treatment in PDB is to control bone pain thought to be due to disease activity.”

The study was funded by grants from Arthritis Research UK and the Paget’s Association. Dr. Ralston reported receiving consultancy fees on behalf of his institution from Novartis and Merck and grant support on behalf of his institution from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and UCB. One coauthor reported receiving consultancy fees from Siemens, Becton Dickinson, and Roche, and another disclosed receiving such fees from Internis.

FROM JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Intensive bisphosphonate therapy did not yield significant differences in rates of fractures (P = .087), orthopedic procedures (P = .214), and serious adverse events (RR = 1.28).

Data source: An extension study of a randomized trial involving 502 PDB patients during January 2007-January 2012.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from Arthritis Research UK and the Paget’s Association. Dr. Ralston reported receiving consultancy fees on behalf of his institution from Novartis and Merck and grant support on behalf of his institution from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and UCB. One coauthor reported receiving consultancy fees from Siemens, Becton Dickinson, and Roche, and another disclosed receiving such fees from Internis.

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

ANSWER

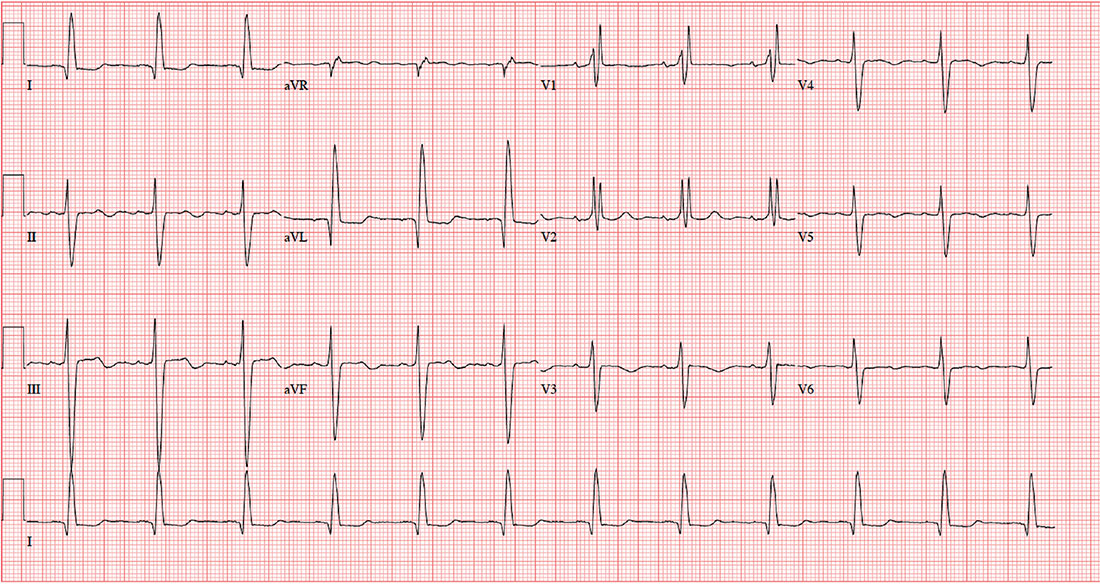

The correct diagnosis includes normal sinus rhythm with a left-axis deviation, right bundle branch block, and left anterior fascicular block, consistent with bifascicular block.

Left-axis deviation is evidenced by an axis beyond –30°. A right bundle branch block is marked by a QRS duration > 120 ms, an RSR’ pattern in lead V1 and often V2 and V3, and wide S waves in lateral leads V5 and V6.

A left anterior fascicular block is identified by a left-axis deviation beyond –45°, a QR complex in lead I, and an RS complex in leads II and III.

The combination of a right bundle and left anterior fascicular block constitute bifascicular block. In this case, only the left fascicle conducts normally, putting this patient at risk for trifascicular block (ie, third-degree or complete heart block).

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis includes normal sinus rhythm with a left-axis deviation, right bundle branch block, and left anterior fascicular block, consistent with bifascicular block.

Left-axis deviation is evidenced by an axis beyond –30°. A right bundle branch block is marked by a QRS duration > 120 ms, an RSR’ pattern in lead V1 and often V2 and V3, and wide S waves in lateral leads V5 and V6.

A left anterior fascicular block is identified by a left-axis deviation beyond –45°, a QR complex in lead I, and an RS complex in leads II and III.

The combination of a right bundle and left anterior fascicular block constitute bifascicular block. In this case, only the left fascicle conducts normally, putting this patient at risk for trifascicular block (ie, third-degree or complete heart block).

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis includes normal sinus rhythm with a left-axis deviation, right bundle branch block, and left anterior fascicular block, consistent with bifascicular block.

Left-axis deviation is evidenced by an axis beyond –30°. A right bundle branch block is marked by a QRS duration > 120 ms, an RSR’ pattern in lead V1 and often V2 and V3, and wide S waves in lateral leads V5 and V6.

A left anterior fascicular block is identified by a left-axis deviation beyond –45°, a QR complex in lead I, and an RS complex in leads II and III.

The combination of a right bundle and left anterior fascicular block constitute bifascicular block. In this case, only the left fascicle conducts normally, putting this patient at risk for trifascicular block (ie, third-degree or complete heart block).

A 72-year-old man with chronic osteoarthritis is scheduled for left knee replacement and sent for preoperative assessment. He has been physically active his entire life, but in the past five years, both knees have developed osteoarthritis that prevents him from walking more than 20 feet without stopping. He is obese and has hyperlipidemia and type 2 diabetes. He has never had angina, shortness of breath, paroxysmal dyspnea, or hypertension.

The patient is retired after 27 years’ service in the Air Force followed by an 18-year career with a major airline. He is married, with three adult children who are all in good health. He quit smoking at age 35 but states half-seriously that he “gave up cigarettes for candy bars and ice cream.” He says he drank heavily during his early years of service but rarely has more than one or two beers per week now.

Medical and surgical histories are remarkable for multiple arthroscopic procedures involving the medial meniscus and anterior collateral ligament of both knees. He has also had xanthelasmas removed from both eyelids, surgical repair of a compound fracture of the left humerus, and shrapnel removed from the subcutaneous tissue on the left upper back.

His medication list includes atorvastatin and metformin. He is allergic to sulfa, which has induced anaphylaxis in the past.

The review of systems reveals he is hard of hearing; he has hearing aids but refuses to wear them. He wears trifocal glasses and a partial upper bridge. He denies any cardiac, pulmonary, neurologic, or gastrointestinal problems. He does report difficulty starting and stopping a stream of urine, as well as occasional accidents. He also admits to having erectile dysfunction but does not think it is a problem he needs to address.

Vital signs include a blood pressure of 124/74 mm Hg; pulse, 70 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 98.4°F. His weight is 264 lb and his height, 69 in. He is pleasant, cooperative, alert, and oriented.

Physical exam reveals normal heart sounds without murmurs, clicks, or rubs. The lungs are clear in all fields. The abdomen is large but soft, and the liver edge is palpable 3 cm below the costal margin. Peripheral pulses are 2+ bilaterally in all extremities. Surgical scars are present on the left humerus, left scapula, and both knees. Neurologically, the patient is intact, and there is no evidence of microvascular disease secondary to his diabetes.

An ECG is performed. It reveals a ventricular rate of 71 beats/min; PR interval, 152 ms; QRS duration, 142 ms; QT/QTc interval, 476/517 ms; P axis, 76°; R axis, –48°; and T axis, 161°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Rosacea research reveals advances, promising therapies

MIAMI – Management of rosacea continues to challenge dermatologists and patients alike, although new advances and recent studies shine a light on promising new therapies to target this inflammatory skin condition.

Linda Stein Gold, MD, who directs dermatology clinical trials at the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, shared new information about the pathophysiology of rosacea and the controversial associations with cardiovascular disease and addressed the rosacea “genes versus environment” etiology question at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

The topical vasoconstrictor of cutaneous vasculature, oxymetazoline hydrochloride cream 1%, showed a statistically significant improvement in erythema, compared with vehicle only in people with rosacea in a phase III study, Dr. Stein Gold said. The outcome was strict, requiring both physician and patient assessment of at least a two-point improvement on the Erythema Assessment Scale. Investigators observed responses over 12 hours on the same day. “It’s actually kind of fun to do these studies,” she added. “You get to see what happens with patients across a whole day.”

A long-term analysis showed the efficacy of oxymetazoline “actually increased over the course of 52 weeks,” Dr. Stein Gold said. A total of 43% of participants experienced a two-grade improvement in erythema during this time. The agent was generally well tolerated, with dermatitis, pruritus, and headaches the most common treatment-related adverse events reported. (In January, the Food and Drug Administration approved oxymetazoline cream for the treatment of “persistent facial erythema associated with rosacea in adults.”)

Sometimes, a new formulation can make a difference in terms of treatment tolerability, a major consideration for patients with rosacea, Dr. Stein Gold said. Recent evidence suggests azelaic acid foam, 15% (Finacea), approved by the FDA in 2015, provides a well-tolerated option with only 6.2% of patients experiencing any application site pain, compared with 1.5% on vehicle alone, she added.

Cardiovascular comorbidities

“We’ve heard a lot about psoriasis and cardiovascular comorbidities, and we worry that other skin diseases may have similar associations,” Dr. Stein Gold said. New revelations in the pathogenesis of rosacea suggest a comparable association, she added, including findings related to matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). MMPs have a key role in rosacea, for example, and are also important in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, she noted. Several studies have confirmed this association as well as other links, including to Parkinson’s disease.

Although these studies support associations, more evidence is needed to prove any causal relationship between rosacea and other conditions where inflammation plays a prominent role, she added.

Translating findings into action

Given this emerging evidence, “what are we going to do about it?” Dr. Stein Gold asked attendees at the meeting. Research suggests tetracycline might be protective, she said, because this antibiotic can inhibit MMP activity. In a retrospective cohort study, investigators discovered rosacea patients on tetracycline therapy were at lower risk for developing vascular disease (J Invest Dermatol. 2014 Aug;134[8]:2267-9).

Nature or nurture?

Researchers and clinicians frequently debate the precise etiology of rosacea and whether the underlying causes are primarily genetic versus environmental. Investigators conducted a twin cohort study to find a more concrete answer, specifically looking at identical and fraternal twin pairs to determine how much genetics or environment likely contributes to factors on the National Rosacea Society grading system (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Nov;151[11]:1213-9).

“The bottom line is it’s really about half and half – about half were associated with genetics, the other half with environment,” Dr. Stein Gold said.

No matter what the etiology, it’s important to diagnose and treat rosacea, Dr. Stein Gold said. Although patients tend to be middle-aged white women, the condition is not limited to this patient population, and “you have to think about it to diagnose it in skin of color,” she added.

Rosacea, which has a high emotional impact, presents an opportunity for dermatologists to improve quality of life, Dr. Stein Gold said. “When people walk around with papules and pustules, [other] people think there is something wrong with them.”

Dr. Stein Gold disclosed that she is a consultant, member of the advisory boards and speaker’s bureaus for, and receives research grants from Galderma, Leo, Novan, Valeant, Novartis, Celgene and Allergan. She is also a consultant, advisory board member, and receives research grants from Dermira and Foamix. She is a consultant to Sol-Gel, Promis, Anacor, and Medimetriks. She is on the advisory board for Promis.

MIAMI – Management of rosacea continues to challenge dermatologists and patients alike, although new advances and recent studies shine a light on promising new therapies to target this inflammatory skin condition.

Linda Stein Gold, MD, who directs dermatology clinical trials at the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, shared new information about the pathophysiology of rosacea and the controversial associations with cardiovascular disease and addressed the rosacea “genes versus environment” etiology question at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

The topical vasoconstrictor of cutaneous vasculature, oxymetazoline hydrochloride cream 1%, showed a statistically significant improvement in erythema, compared with vehicle only in people with rosacea in a phase III study, Dr. Stein Gold said. The outcome was strict, requiring both physician and patient assessment of at least a two-point improvement on the Erythema Assessment Scale. Investigators observed responses over 12 hours on the same day. “It’s actually kind of fun to do these studies,” she added. “You get to see what happens with patients across a whole day.”

A long-term analysis showed the efficacy of oxymetazoline “actually increased over the course of 52 weeks,” Dr. Stein Gold said. A total of 43% of participants experienced a two-grade improvement in erythema during this time. The agent was generally well tolerated, with dermatitis, pruritus, and headaches the most common treatment-related adverse events reported. (In January, the Food and Drug Administration approved oxymetazoline cream for the treatment of “persistent facial erythema associated with rosacea in adults.”)

Sometimes, a new formulation can make a difference in terms of treatment tolerability, a major consideration for patients with rosacea, Dr. Stein Gold said. Recent evidence suggests azelaic acid foam, 15% (Finacea), approved by the FDA in 2015, provides a well-tolerated option with only 6.2% of patients experiencing any application site pain, compared with 1.5% on vehicle alone, she added.

Cardiovascular comorbidities

“We’ve heard a lot about psoriasis and cardiovascular comorbidities, and we worry that other skin diseases may have similar associations,” Dr. Stein Gold said. New revelations in the pathogenesis of rosacea suggest a comparable association, she added, including findings related to matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). MMPs have a key role in rosacea, for example, and are also important in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, she noted. Several studies have confirmed this association as well as other links, including to Parkinson’s disease.

Although these studies support associations, more evidence is needed to prove any causal relationship between rosacea and other conditions where inflammation plays a prominent role, she added.

Translating findings into action

Given this emerging evidence, “what are we going to do about it?” Dr. Stein Gold asked attendees at the meeting. Research suggests tetracycline might be protective, she said, because this antibiotic can inhibit MMP activity. In a retrospective cohort study, investigators discovered rosacea patients on tetracycline therapy were at lower risk for developing vascular disease (J Invest Dermatol. 2014 Aug;134[8]:2267-9).

Nature or nurture?

Researchers and clinicians frequently debate the precise etiology of rosacea and whether the underlying causes are primarily genetic versus environmental. Investigators conducted a twin cohort study to find a more concrete answer, specifically looking at identical and fraternal twin pairs to determine how much genetics or environment likely contributes to factors on the National Rosacea Society grading system (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Nov;151[11]:1213-9).

“The bottom line is it’s really about half and half – about half were associated with genetics, the other half with environment,” Dr. Stein Gold said.

No matter what the etiology, it’s important to diagnose and treat rosacea, Dr. Stein Gold said. Although patients tend to be middle-aged white women, the condition is not limited to this patient population, and “you have to think about it to diagnose it in skin of color,” she added.

Rosacea, which has a high emotional impact, presents an opportunity for dermatologists to improve quality of life, Dr. Stein Gold said. “When people walk around with papules and pustules, [other] people think there is something wrong with them.”

Dr. Stein Gold disclosed that she is a consultant, member of the advisory boards and speaker’s bureaus for, and receives research grants from Galderma, Leo, Novan, Valeant, Novartis, Celgene and Allergan. She is also a consultant, advisory board member, and receives research grants from Dermira and Foamix. She is a consultant to Sol-Gel, Promis, Anacor, and Medimetriks. She is on the advisory board for Promis.

MIAMI – Management of rosacea continues to challenge dermatologists and patients alike, although new advances and recent studies shine a light on promising new therapies to target this inflammatory skin condition.

Linda Stein Gold, MD, who directs dermatology clinical trials at the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, shared new information about the pathophysiology of rosacea and the controversial associations with cardiovascular disease and addressed the rosacea “genes versus environment” etiology question at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

The topical vasoconstrictor of cutaneous vasculature, oxymetazoline hydrochloride cream 1%, showed a statistically significant improvement in erythema, compared with vehicle only in people with rosacea in a phase III study, Dr. Stein Gold said. The outcome was strict, requiring both physician and patient assessment of at least a two-point improvement on the Erythema Assessment Scale. Investigators observed responses over 12 hours on the same day. “It’s actually kind of fun to do these studies,” she added. “You get to see what happens with patients across a whole day.”

A long-term analysis showed the efficacy of oxymetazoline “actually increased over the course of 52 weeks,” Dr. Stein Gold said. A total of 43% of participants experienced a two-grade improvement in erythema during this time. The agent was generally well tolerated, with dermatitis, pruritus, and headaches the most common treatment-related adverse events reported. (In January, the Food and Drug Administration approved oxymetazoline cream for the treatment of “persistent facial erythema associated with rosacea in adults.”)

Sometimes, a new formulation can make a difference in terms of treatment tolerability, a major consideration for patients with rosacea, Dr. Stein Gold said. Recent evidence suggests azelaic acid foam, 15% (Finacea), approved by the FDA in 2015, provides a well-tolerated option with only 6.2% of patients experiencing any application site pain, compared with 1.5% on vehicle alone, she added.

Cardiovascular comorbidities

“We’ve heard a lot about psoriasis and cardiovascular comorbidities, and we worry that other skin diseases may have similar associations,” Dr. Stein Gold said. New revelations in the pathogenesis of rosacea suggest a comparable association, she added, including findings related to matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). MMPs have a key role in rosacea, for example, and are also important in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, she noted. Several studies have confirmed this association as well as other links, including to Parkinson’s disease.

Although these studies support associations, more evidence is needed to prove any causal relationship between rosacea and other conditions where inflammation plays a prominent role, she added.

Translating findings into action

Given this emerging evidence, “what are we going to do about it?” Dr. Stein Gold asked attendees at the meeting. Research suggests tetracycline might be protective, she said, because this antibiotic can inhibit MMP activity. In a retrospective cohort study, investigators discovered rosacea patients on tetracycline therapy were at lower risk for developing vascular disease (J Invest Dermatol. 2014 Aug;134[8]:2267-9).

Nature or nurture?

Researchers and clinicians frequently debate the precise etiology of rosacea and whether the underlying causes are primarily genetic versus environmental. Investigators conducted a twin cohort study to find a more concrete answer, specifically looking at identical and fraternal twin pairs to determine how much genetics or environment likely contributes to factors on the National Rosacea Society grading system (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Nov;151[11]:1213-9).

“The bottom line is it’s really about half and half – about half were associated with genetics, the other half with environment,” Dr. Stein Gold said.

No matter what the etiology, it’s important to diagnose and treat rosacea, Dr. Stein Gold said. Although patients tend to be middle-aged white women, the condition is not limited to this patient population, and “you have to think about it to diagnose it in skin of color,” she added.

Rosacea, which has a high emotional impact, presents an opportunity for dermatologists to improve quality of life, Dr. Stein Gold said. “When people walk around with papules and pustules, [other] people think there is something wrong with them.”

Dr. Stein Gold disclosed that she is a consultant, member of the advisory boards and speaker’s bureaus for, and receives research grants from Galderma, Leo, Novan, Valeant, Novartis, Celgene and Allergan. She is also a consultant, advisory board member, and receives research grants from Dermira and Foamix. She is a consultant to Sol-Gel, Promis, Anacor, and Medimetriks. She is on the advisory board for Promis.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ODAC 2017

History of child abuse worsens depression course in elderly adults

Older adults with depression who reported experiencing child abuse were more likely to have persistent disease at follow-up than those who did not, according to a study carried out by Ilse Wielaard and associates at the VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

The mean age of the 282 study participants included in the 2-year study was 70.6 years, and of this group, 152 patients reported a history of child abuse. Patients with a history of child abuse were significantly more likely to be depressed at the end of the 2-year follow-up period.

“In the treatment of late-life depression it is important to detect childhood abuse and to consider mediating characteristics that influence its course negatively,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry (doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.01.014).

Older adults with depression who reported experiencing child abuse were more likely to have persistent disease at follow-up than those who did not, according to a study carried out by Ilse Wielaard and associates at the VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

The mean age of the 282 study participants included in the 2-year study was 70.6 years, and of this group, 152 patients reported a history of child abuse. Patients with a history of child abuse were significantly more likely to be depressed at the end of the 2-year follow-up period.

“In the treatment of late-life depression it is important to detect childhood abuse and to consider mediating characteristics that influence its course negatively,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry (doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.01.014).

Older adults with depression who reported experiencing child abuse were more likely to have persistent disease at follow-up than those who did not, according to a study carried out by Ilse Wielaard and associates at the VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

The mean age of the 282 study participants included in the 2-year study was 70.6 years, and of this group, 152 patients reported a history of child abuse. Patients with a history of child abuse were significantly more likely to be depressed at the end of the 2-year follow-up period.

“In the treatment of late-life depression it is important to detect childhood abuse and to consider mediating characteristics that influence its course negatively,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry (doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.01.014).

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GERIATRIC PSYCHIATRY

Don't rule out liver transplant grafts from octogenarians

Donors aged 80 years or older are not necessarily inferior for a liver transplantation (LT) graft, compared with young ideal donors (aged 18-39 years), according to an analysis of the perioperative LT period.

While “the potential risks and benefits associated with the use of livers from octogenarian donors must be closely weighed, with careful donor evaluation, selective donor-to-recipient matching and skilled perioperative care, octogenarian grafts do not affect the short-term course of patients undergoing LT,” concluded Gianni Biancofiore, MD, of Azienda Ospedaliera-Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy, and his coauthors (Dig Liver Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.01.149).

Perioperative differences were insubstantial in terms of cardiovascular complications (P = .2), respiratory complications (P = 1.0), coagulopathy (P = .5), and incidence of perfusion syndrome (P = .3). Median ICU length of stay of the two groups was identical (P = .4). No differences in terms of death or retransplant were observed during the ICU stay.

“Accordingly, anesthesiologists and intensivists should not label liver allografts from donors aged 80 years [or older] as ‘unusable’ or ‘high risk’ ” based on age alone, the authors concluded.

The authors declared no sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Donors aged 80 years or older are not necessarily inferior for a liver transplantation (LT) graft, compared with young ideal donors (aged 18-39 years), according to an analysis of the perioperative LT period.