User login

Guidelines needed for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery

A new study of pregnant Medicaid patients in Pennsylvania found that 12% filled prescriptions for opioids within 5 days of vaginal delivery, even though fewer than one-third of the women had pain-inducing conditions.

“Our study raises the question: Why is outpatient opioid use not rare after vaginal delivery?” lead author Marian Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “Outpatient opioid prescriptions after a hospitalization may be one potential pathway to opioid use disorder. I hope the study will prompt some thought about why opioids are being prescribed for women after vaginal delivery and how to best manage postdelivery pain. This is especially important in areas of the country that have extraordinarily high rates of opioid use disorder.”

A total of 12% of the women (18,131) filled an outpatient prescription for an opioid with 5 days of giving birth. Of those, just 28.2% (5,110) had one or more conditions that cause an increased level of pain after delivery, such as bilateral tubal ligation, certain kinds of lacerations, and episiotomy.

During the first 5 days after birth, the most commonly prescribed opioid was oxycodone-acetaminophen (53.3%), followed by acetaminophen-codeine (20.5%), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (19.6%).

Of the 18,131 women with an early postdelivery opioid prescription, 14% (2,592) filled at least one other opioid prescription within 6-60 days – that’s 1.6% of all the women in the study.

“On a positive note, we saw the supply of opioid prescriptions was generally short at 3-7 days,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

The researchers linked tobacco use and a mental health condition (both adjusted odds ratio 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.4) to a higher risk of filling a prescription without being diagnosed with a pain-causing disorder. They also found an association between substance use disorder (not related to opioids) and a higher risk of these types of prescriptions, but only for filling a second opioid prescription in the 6-60 day period (aOR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6).

The researchers called for national guidelines regarding the use of opioids after birth.

“Several organizations have developed opioid prescribing guidelines for chronic and acute pain,” Dr. Jarlenski said. “These guidelines are necessary because the risk of opioid use disorder and subsequent overdose events is well established. Although delivery is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United States, there are no national guidelines for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery.”

The study was partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study of pregnant Medicaid patients in Pennsylvania found that 12% filled prescriptions for opioids within 5 days of vaginal delivery, even though fewer than one-third of the women had pain-inducing conditions.

“Our study raises the question: Why is outpatient opioid use not rare after vaginal delivery?” lead author Marian Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “Outpatient opioid prescriptions after a hospitalization may be one potential pathway to opioid use disorder. I hope the study will prompt some thought about why opioids are being prescribed for women after vaginal delivery and how to best manage postdelivery pain. This is especially important in areas of the country that have extraordinarily high rates of opioid use disorder.”

A total of 12% of the women (18,131) filled an outpatient prescription for an opioid with 5 days of giving birth. Of those, just 28.2% (5,110) had one or more conditions that cause an increased level of pain after delivery, such as bilateral tubal ligation, certain kinds of lacerations, and episiotomy.

During the first 5 days after birth, the most commonly prescribed opioid was oxycodone-acetaminophen (53.3%), followed by acetaminophen-codeine (20.5%), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (19.6%).

Of the 18,131 women with an early postdelivery opioid prescription, 14% (2,592) filled at least one other opioid prescription within 6-60 days – that’s 1.6% of all the women in the study.

“On a positive note, we saw the supply of opioid prescriptions was generally short at 3-7 days,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

The researchers linked tobacco use and a mental health condition (both adjusted odds ratio 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.4) to a higher risk of filling a prescription without being diagnosed with a pain-causing disorder. They also found an association between substance use disorder (not related to opioids) and a higher risk of these types of prescriptions, but only for filling a second opioid prescription in the 6-60 day period (aOR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6).

The researchers called for national guidelines regarding the use of opioids after birth.

“Several organizations have developed opioid prescribing guidelines for chronic and acute pain,” Dr. Jarlenski said. “These guidelines are necessary because the risk of opioid use disorder and subsequent overdose events is well established. Although delivery is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United States, there are no national guidelines for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery.”

The study was partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study of pregnant Medicaid patients in Pennsylvania found that 12% filled prescriptions for opioids within 5 days of vaginal delivery, even though fewer than one-third of the women had pain-inducing conditions.

“Our study raises the question: Why is outpatient opioid use not rare after vaginal delivery?” lead author Marian Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “Outpatient opioid prescriptions after a hospitalization may be one potential pathway to opioid use disorder. I hope the study will prompt some thought about why opioids are being prescribed for women after vaginal delivery and how to best manage postdelivery pain. This is especially important in areas of the country that have extraordinarily high rates of opioid use disorder.”

A total of 12% of the women (18,131) filled an outpatient prescription for an opioid with 5 days of giving birth. Of those, just 28.2% (5,110) had one or more conditions that cause an increased level of pain after delivery, such as bilateral tubal ligation, certain kinds of lacerations, and episiotomy.

During the first 5 days after birth, the most commonly prescribed opioid was oxycodone-acetaminophen (53.3%), followed by acetaminophen-codeine (20.5%), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (19.6%).

Of the 18,131 women with an early postdelivery opioid prescription, 14% (2,592) filled at least one other opioid prescription within 6-60 days – that’s 1.6% of all the women in the study.

“On a positive note, we saw the supply of opioid prescriptions was generally short at 3-7 days,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

The researchers linked tobacco use and a mental health condition (both adjusted odds ratio 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.4) to a higher risk of filling a prescription without being diagnosed with a pain-causing disorder. They also found an association between substance use disorder (not related to opioids) and a higher risk of these types of prescriptions, but only for filling a second opioid prescription in the 6-60 day period (aOR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6).

The researchers called for national guidelines regarding the use of opioids after birth.

“Several organizations have developed opioid prescribing guidelines for chronic and acute pain,” Dr. Jarlenski said. “These guidelines are necessary because the risk of opioid use disorder and subsequent overdose events is well established. Although delivery is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United States, there are no national guidelines for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery.”

The study was partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 12% of women on Medicaid filled opioid prescriptions within 5 days of delivery; just 28.2% of those patients had a pain-inducing condition.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 164,720 women enrolled in Medicaid in Pennsylvania who delivered live-born babies vaginally from 2008 to 2013.

Disclosures: The study is partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Review offers reassurance on prenatal Tdap vaccination safety

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60.

Data source: A systematic review of 21 studies.

Disclosures: Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Crusted scabies outbreak: How much prophylaxis?

, a small case series suggests.

What remains a matter of debate is how widely to use prophylaxis, according to authors of a study of two approaches published in Infection, Disease & Health.

The case series, coauthored by Dr. Nikki R. Adler and her colleagues at Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, compares and contrasts two approaches to a scabies outbreak in a tertiary care setting (Infect Dis Health. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2017.01.001).

One scenario involved an elderly woman who had been transferred from a rehabilitation facility for hip replacement surgery. Although upon admission the patient reported a pruritic truncal rash of 2 weeks’ duration, it was associated by the care team with either a cutaneous adverse drug reaction or with paraneoplastic syndrome, as she had recently been diagnosed with multiple myeloma. As a result, it wasn’t until after the patient’s emergent care needs were met 4 weeks later that she was given a formal dermatology consult, at which time several punch biopsies confirmed crusted scabies; she was treated with 5% permethrin cream for a week, weekly oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg for 1 month, as well as with topical keratolytics.

Meanwhile, because the delayed diagnosis meant the patient – who had been treated across several wards – had potentially exposed multiple health care workers and patients to Sarcoptes scabiei, the hospital immediately instituted contact precautions and implemented its outbreak protocols: communication statements, prophylactic treatment of asymptomatic staff and close patients, and treatment and quarantine for those with clinical symptoms.

The second case involved an elderly man admitted through the emergency department after presenting with fever, hypotension, and a 3-week history of a progressive, hyperkeratotic, pruritic rash on his trunk and arms. A recent heart transplant recipient, he was taking cyclosporine, mycophenolate, and prednisolone, and he had hemodialysis-dependent end-stage kidney disease. After an ED dermatologic review, he was diagnosed with S. scabiei, immediately triggering contact precautions in the ED and elsewhere. He was treated with ivermectin, 5% permethrin, and topical keratolytics. All staff thought to have been exposed to the patient were treated prophylactically with 5% permethrin single-dose therapy.

Because thickened skin flakes that slough off in crusted scabies may house hundreds of mites for longer than 48 hours, environmental cleaning was enhanced in both cases.

The latter case did not feature a prolonged outbreak thanks to early diagnosis and quick preventive action. The outbreak in the first case lasted 7 weeks and 5 days. The hospital in that case opted not to employ a mass prophylaxis strategy, instead treating 306 persons identified to have been in contact with the patient. In all, 54 symptomatic patients and health care workers were identified.

The authors cited data that, across 19 nosocomial outbreaks between 1990 and 2003, the mean number of infested patients was 18; the mean number for health care workers was 39. The attack rate, defined as the number of new cases divided by the total number of persons at risk, was 13% for patients and 35% in health care workers. The median duration of outbreak was 14.5 weeks (range, 4-52 weeks).

“The variation of outbreak size and duration in the reported literature suggests that there may be important differences in the efficacy of various infection control strategies,” Dr. Adler and her colleagues wrote, noting that while some institutions might prefer simultaneous mass prophylaxis to rapidly and efficiently control a scabies outbreak, the cost of doing so can be prohibitive, and might not be more effective than the information-centered management model used in Case 1 that relied on close tracking of all patient contacts, and use of the hospital intranet and internal memos.

This strategy does run the risk of overreaction, however: “The communication strategy may have contributed to heightened levels of concern among staff and arguably, excessive prophylaxis and/or overdiagnosis,” the authors wrote.

To help diagnose potential cases of crusted scabies quickly, Dr. Adler and her colleagues suggested clinicians consider that various dermatoses can mimic a scabies infestation and that care teams have a high index of suspicion in patients most at risk for scabies: the elderly and those who are immunocompromised, such as the heart transplant patient in Case 2, and also those with altered T-cell function.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

, a small case series suggests.

What remains a matter of debate is how widely to use prophylaxis, according to authors of a study of two approaches published in Infection, Disease & Health.

The case series, coauthored by Dr. Nikki R. Adler and her colleagues at Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, compares and contrasts two approaches to a scabies outbreak in a tertiary care setting (Infect Dis Health. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2017.01.001).

One scenario involved an elderly woman who had been transferred from a rehabilitation facility for hip replacement surgery. Although upon admission the patient reported a pruritic truncal rash of 2 weeks’ duration, it was associated by the care team with either a cutaneous adverse drug reaction or with paraneoplastic syndrome, as she had recently been diagnosed with multiple myeloma. As a result, it wasn’t until after the patient’s emergent care needs were met 4 weeks later that she was given a formal dermatology consult, at which time several punch biopsies confirmed crusted scabies; she was treated with 5% permethrin cream for a week, weekly oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg for 1 month, as well as with topical keratolytics.

Meanwhile, because the delayed diagnosis meant the patient – who had been treated across several wards – had potentially exposed multiple health care workers and patients to Sarcoptes scabiei, the hospital immediately instituted contact precautions and implemented its outbreak protocols: communication statements, prophylactic treatment of asymptomatic staff and close patients, and treatment and quarantine for those with clinical symptoms.

The second case involved an elderly man admitted through the emergency department after presenting with fever, hypotension, and a 3-week history of a progressive, hyperkeratotic, pruritic rash on his trunk and arms. A recent heart transplant recipient, he was taking cyclosporine, mycophenolate, and prednisolone, and he had hemodialysis-dependent end-stage kidney disease. After an ED dermatologic review, he was diagnosed with S. scabiei, immediately triggering contact precautions in the ED and elsewhere. He was treated with ivermectin, 5% permethrin, and topical keratolytics. All staff thought to have been exposed to the patient were treated prophylactically with 5% permethrin single-dose therapy.

Because thickened skin flakes that slough off in crusted scabies may house hundreds of mites for longer than 48 hours, environmental cleaning was enhanced in both cases.

The latter case did not feature a prolonged outbreak thanks to early diagnosis and quick preventive action. The outbreak in the first case lasted 7 weeks and 5 days. The hospital in that case opted not to employ a mass prophylaxis strategy, instead treating 306 persons identified to have been in contact with the patient. In all, 54 symptomatic patients and health care workers were identified.

The authors cited data that, across 19 nosocomial outbreaks between 1990 and 2003, the mean number of infested patients was 18; the mean number for health care workers was 39. The attack rate, defined as the number of new cases divided by the total number of persons at risk, was 13% for patients and 35% in health care workers. The median duration of outbreak was 14.5 weeks (range, 4-52 weeks).

“The variation of outbreak size and duration in the reported literature suggests that there may be important differences in the efficacy of various infection control strategies,” Dr. Adler and her colleagues wrote, noting that while some institutions might prefer simultaneous mass prophylaxis to rapidly and efficiently control a scabies outbreak, the cost of doing so can be prohibitive, and might not be more effective than the information-centered management model used in Case 1 that relied on close tracking of all patient contacts, and use of the hospital intranet and internal memos.

This strategy does run the risk of overreaction, however: “The communication strategy may have contributed to heightened levels of concern among staff and arguably, excessive prophylaxis and/or overdiagnosis,” the authors wrote.

To help diagnose potential cases of crusted scabies quickly, Dr. Adler and her colleagues suggested clinicians consider that various dermatoses can mimic a scabies infestation and that care teams have a high index of suspicion in patients most at risk for scabies: the elderly and those who are immunocompromised, such as the heart transplant patient in Case 2, and also those with altered T-cell function.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

, a small case series suggests.

What remains a matter of debate is how widely to use prophylaxis, according to authors of a study of two approaches published in Infection, Disease & Health.

The case series, coauthored by Dr. Nikki R. Adler and her colleagues at Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, compares and contrasts two approaches to a scabies outbreak in a tertiary care setting (Infect Dis Health. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2017.01.001).

One scenario involved an elderly woman who had been transferred from a rehabilitation facility for hip replacement surgery. Although upon admission the patient reported a pruritic truncal rash of 2 weeks’ duration, it was associated by the care team with either a cutaneous adverse drug reaction or with paraneoplastic syndrome, as she had recently been diagnosed with multiple myeloma. As a result, it wasn’t until after the patient’s emergent care needs were met 4 weeks later that she was given a formal dermatology consult, at which time several punch biopsies confirmed crusted scabies; she was treated with 5% permethrin cream for a week, weekly oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg for 1 month, as well as with topical keratolytics.

Meanwhile, because the delayed diagnosis meant the patient – who had been treated across several wards – had potentially exposed multiple health care workers and patients to Sarcoptes scabiei, the hospital immediately instituted contact precautions and implemented its outbreak protocols: communication statements, prophylactic treatment of asymptomatic staff and close patients, and treatment and quarantine for those with clinical symptoms.

The second case involved an elderly man admitted through the emergency department after presenting with fever, hypotension, and a 3-week history of a progressive, hyperkeratotic, pruritic rash on his trunk and arms. A recent heart transplant recipient, he was taking cyclosporine, mycophenolate, and prednisolone, and he had hemodialysis-dependent end-stage kidney disease. After an ED dermatologic review, he was diagnosed with S. scabiei, immediately triggering contact precautions in the ED and elsewhere. He was treated with ivermectin, 5% permethrin, and topical keratolytics. All staff thought to have been exposed to the patient were treated prophylactically with 5% permethrin single-dose therapy.

Because thickened skin flakes that slough off in crusted scabies may house hundreds of mites for longer than 48 hours, environmental cleaning was enhanced in both cases.

The latter case did not feature a prolonged outbreak thanks to early diagnosis and quick preventive action. The outbreak in the first case lasted 7 weeks and 5 days. The hospital in that case opted not to employ a mass prophylaxis strategy, instead treating 306 persons identified to have been in contact with the patient. In all, 54 symptomatic patients and health care workers were identified.

The authors cited data that, across 19 nosocomial outbreaks between 1990 and 2003, the mean number of infested patients was 18; the mean number for health care workers was 39. The attack rate, defined as the number of new cases divided by the total number of persons at risk, was 13% for patients and 35% in health care workers. The median duration of outbreak was 14.5 weeks (range, 4-52 weeks).

“The variation of outbreak size and duration in the reported literature suggests that there may be important differences in the efficacy of various infection control strategies,” Dr. Adler and her colleagues wrote, noting that while some institutions might prefer simultaneous mass prophylaxis to rapidly and efficiently control a scabies outbreak, the cost of doing so can be prohibitive, and might not be more effective than the information-centered management model used in Case 1 that relied on close tracking of all patient contacts, and use of the hospital intranet and internal memos.

This strategy does run the risk of overreaction, however: “The communication strategy may have contributed to heightened levels of concern among staff and arguably, excessive prophylaxis and/or overdiagnosis,” the authors wrote.

To help diagnose potential cases of crusted scabies quickly, Dr. Adler and her colleagues suggested clinicians consider that various dermatoses can mimic a scabies infestation and that care teams have a high index of suspicion in patients most at risk for scabies: the elderly and those who are immunocompromised, such as the heart transplant patient in Case 2, and also those with altered T-cell function.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM INFECTION, DISEASE, & HEALTH

Verrucous Carcinoma of the Buccal Mucosa With Extension to the Cheek

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon type of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and was first described by Ackerman1 in 1948. Rock and Fisher2 called this condition oral florid papillomatosis. The distinctive features of this tumor are low-grade malignancy, slow growth, local invasiveness, and rarely intraoral and extraoral metastasis. Extraorally, it can occur in any part of the body,3 a common site being the anogenital region. Depending on the area of occurrence, the condition also is known as Buschke-Lowenstein tumor4 or giant condyloma acuminatum (anogenital region) and carcinoma cuniculatum5 (plantar region). The exact etiology of the condition is unknown, though it is associated with human papillomavirus infection, traumatic scars, chronic infection, tobacco, and chemical carcinogens.3 We report a rare case of verrucous carcinoma originating from the buccal mucosa that subsequently spread to involve the lip and cheek as a large cauliflowerlike growth, which is an unusual presentation.

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a painless growth inside the left side of the oral cavity that had developed 5 years prior as a growth on the left buccal mucosa. The lesion gradually increased in size to involve the left oral commissure including the upper and lower lips and the skin of the left cheek; it extended beyond the nasolabial fold in a cauliflowerlike pattern. The lesion was insidious in onset and was not associated with pain, itching, or bleeding. The patient chewed tobacco for the last 40 years, with no similar lesions on any part of the body. On physical examination a warty papilliform lesion was seen on the left buccal mucosa with extension to 2 cm of the upper and lower lip on the left side including the left oral commissure and the skin of the left cheek beyond the nasolabial fold where it appeared as a cauliflowerlike growth measuring 4×5 cm in size (Figure 1). No notable lymphadenopathy was present.

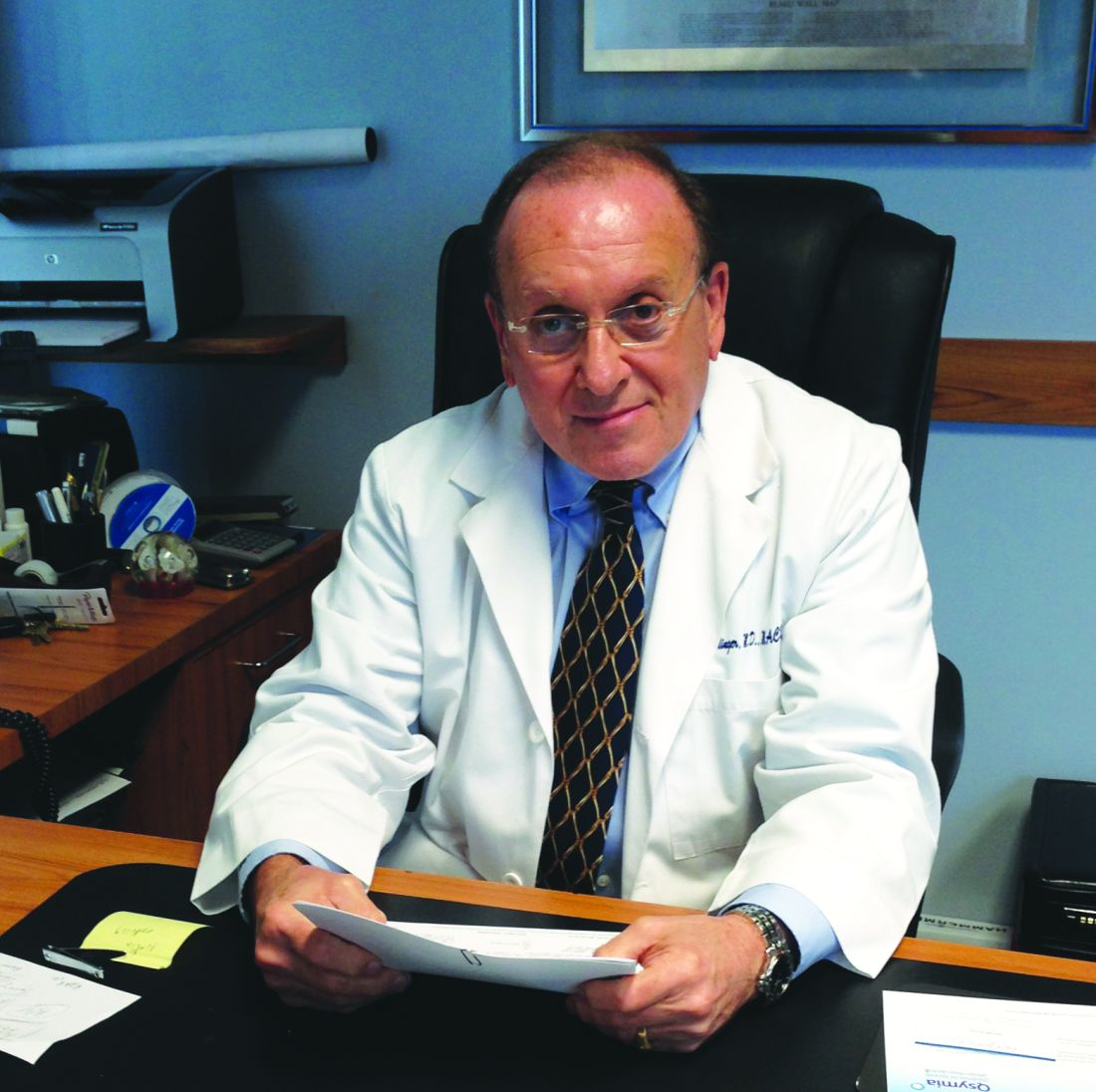

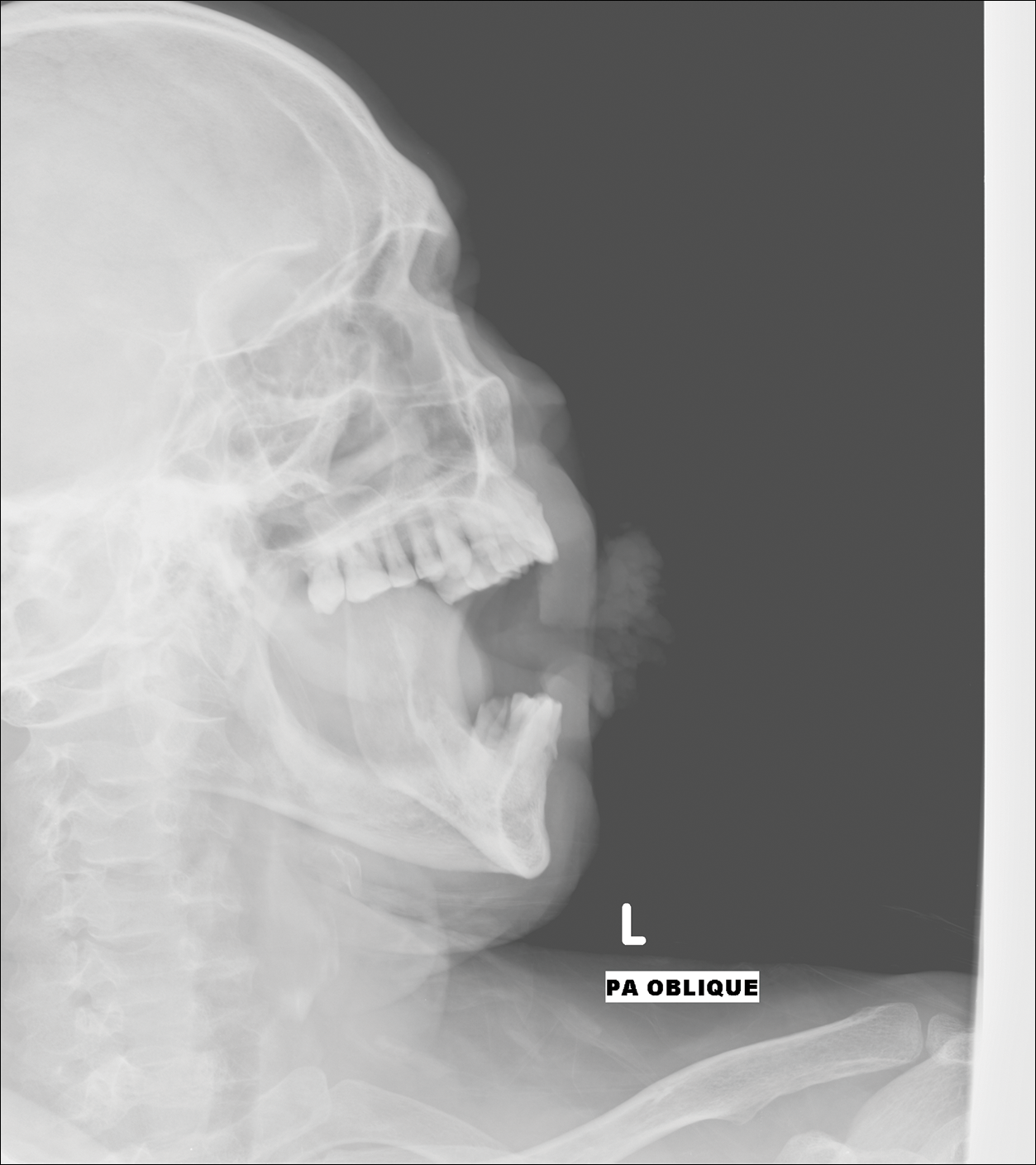

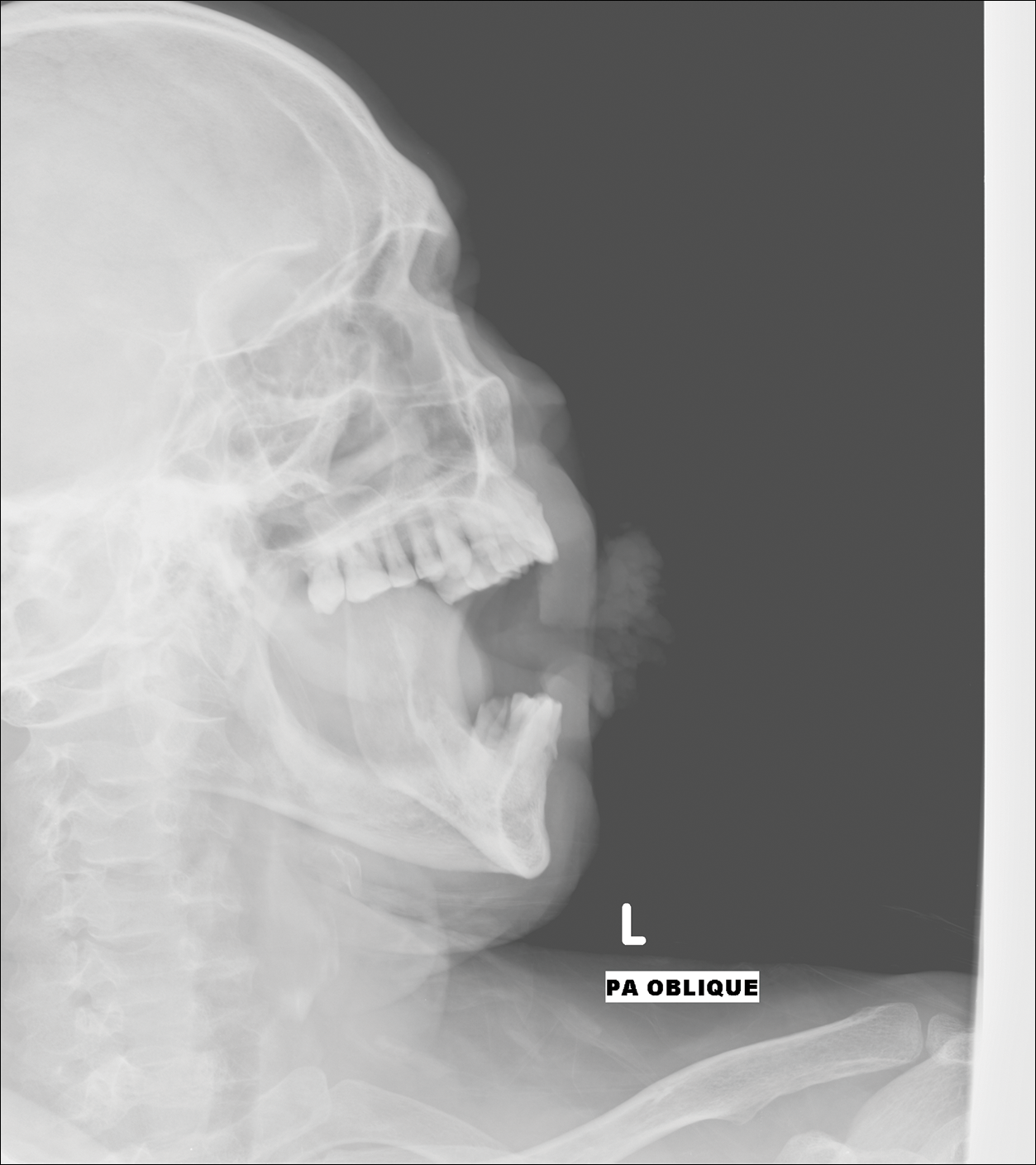

Digital radiographs of the skull (posteroanterior oblique view)(Figure 2) and mandible (left oblique view) showed a lobulated soft-tissue density lesion overlying the left half of the mandible (near the mandibular angle) with involvement of both the upper and lower lips on the left side. However, no obvious underlying bony erosion was noted.

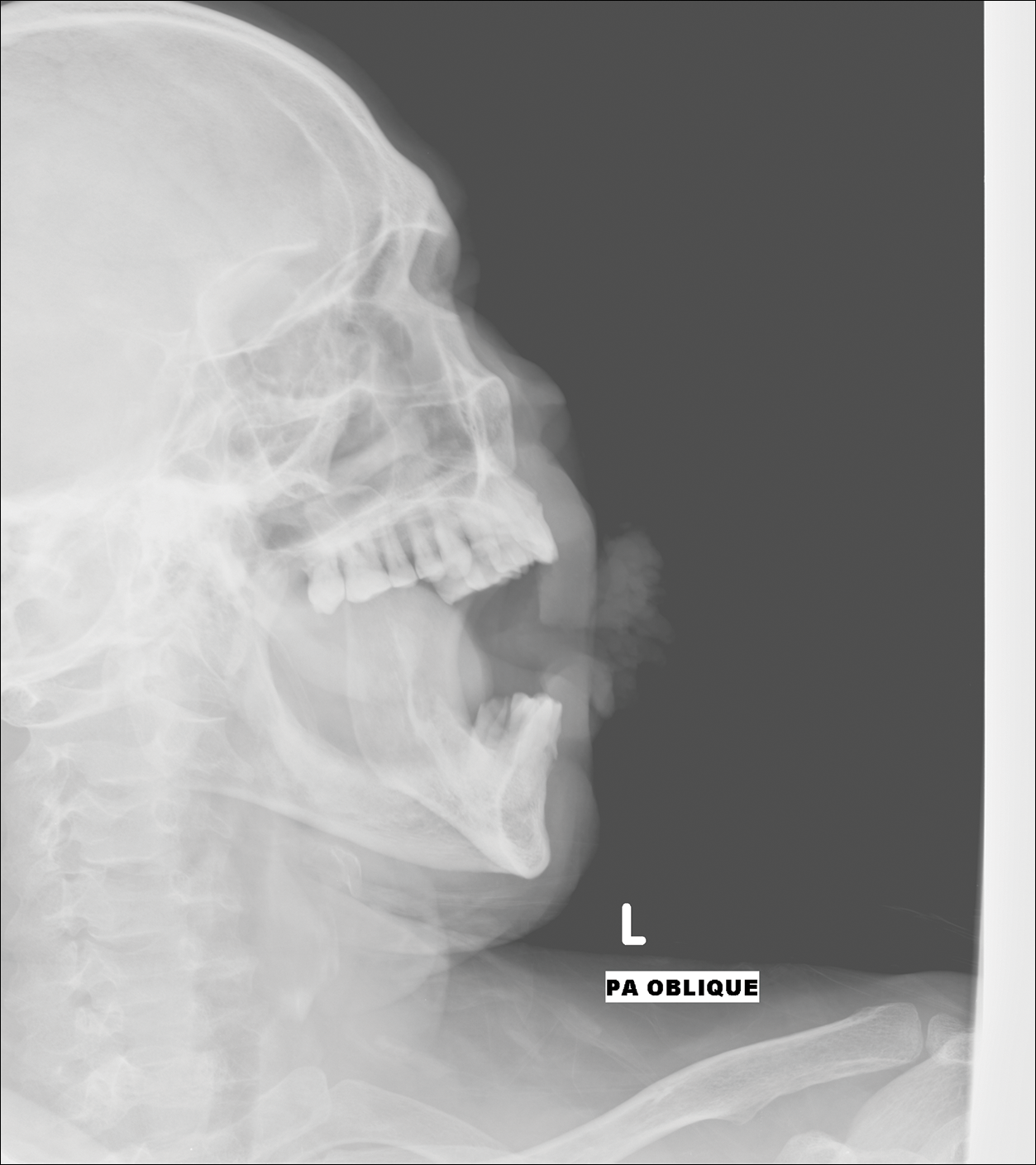

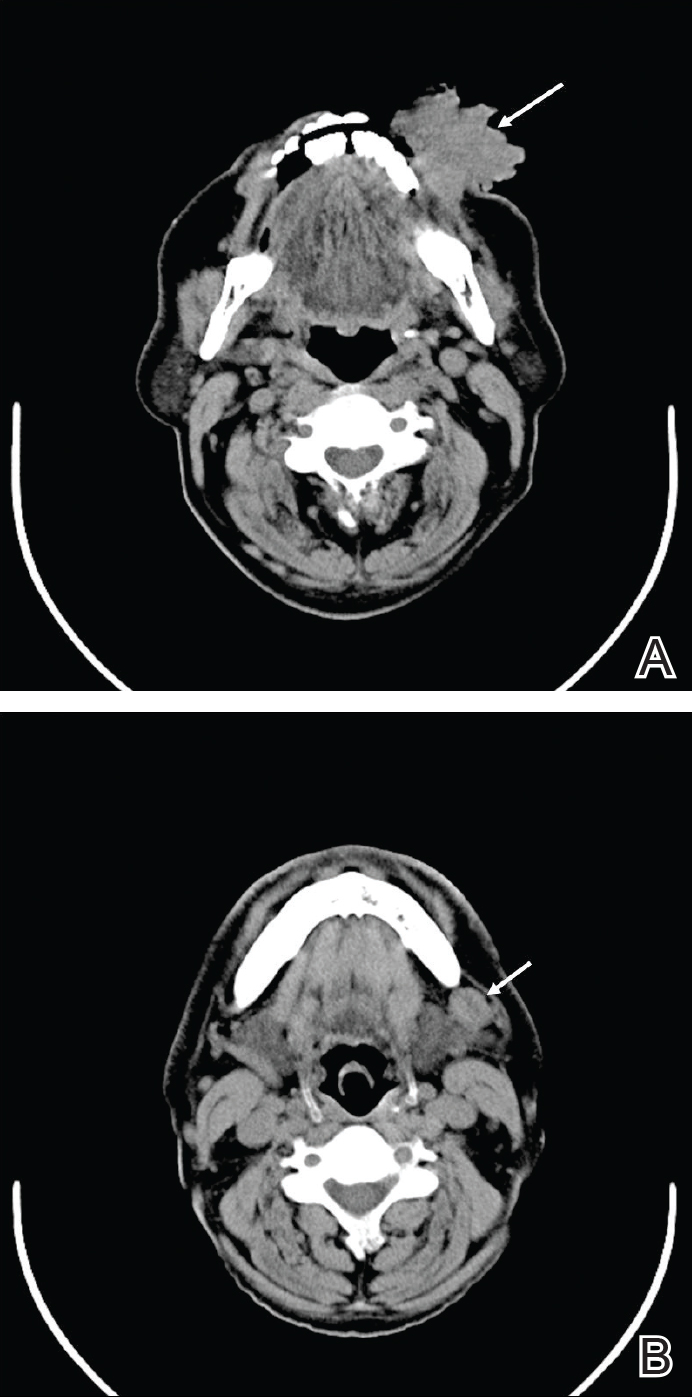

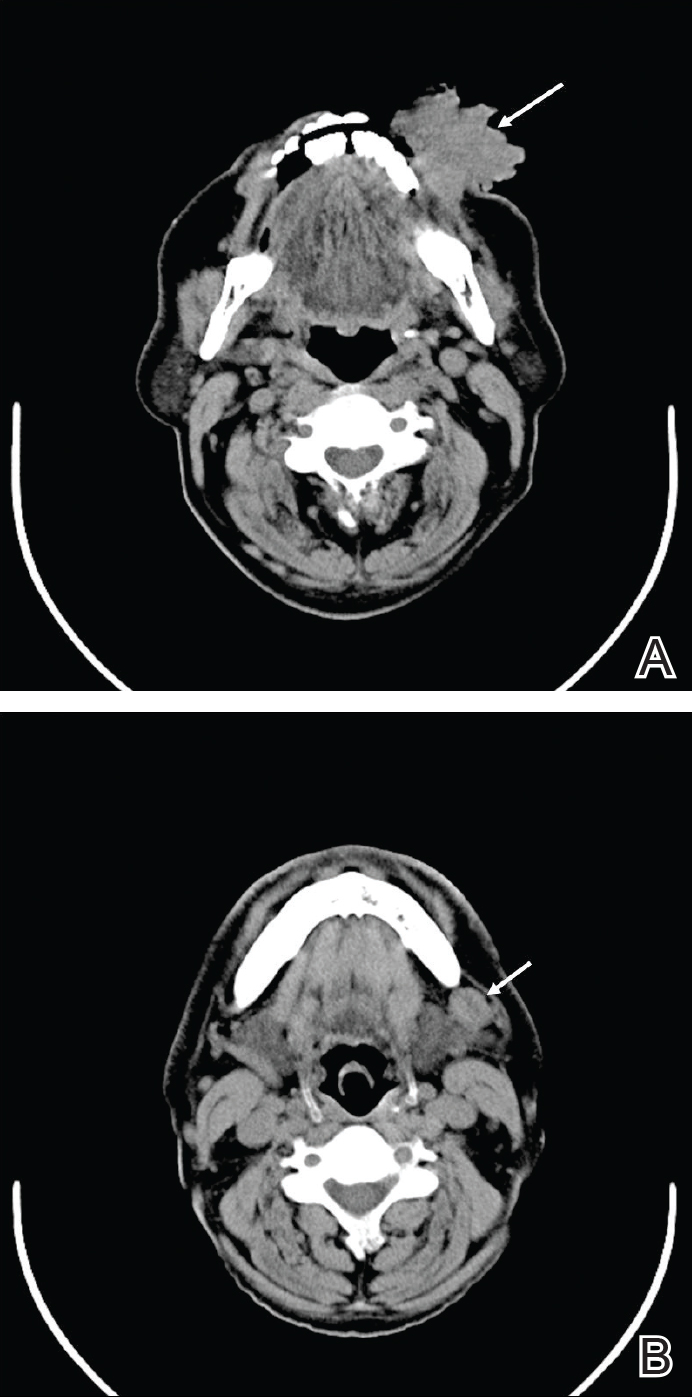

Computed tomography revealed a large soft-tissue mass (41.3×35.3 mm)(Figure 3A) involving the left buccal mucosa with extension into overlying muscle, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. Externally, the lesion was exophytic, irregular, and polypoidal with surface ulceration. Medially, the lesion involved the left oral commissure and parts of the adjoining upper and lower lips. No underlying bony erosion was seen. An enlarged lymph node measuring 20×15 mm was noted in the left upper deep cervical group in the submandibular region (Figure 3B).

Our clinical differential diagnosis included verrucous carcinoma and hypertrophic variety of lupus vulgaris. A 1×2-cm diagnostic incisional biopsy was performed from the cauliflowerlike growth and ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was done from the lymph node. Histopathology revealed a hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium with upward extension of verrucous projections, which was largely superficial to the adjacent epithelium (Figure 4A). In addition to the surface verrucous projections, there was lesion extension into the subepithelial zone in the form of round club-shaped protrusions (Figure 4B). There was no loss of polarity in these downward proliferations. No horn pearl formation was present. Fine-needle aspiration revealed reactive lymphadenitis.

The final diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma was made and the patient was referred to the oncosurgery department for further management.

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, low-grade, well-differentiated SCC of the skin or mucosa presenting with a verrucoid or cauliflowerlike appearance. It shows locally aggressive behavior and has low metastatic potential,6 a low degree of dysplasia, and a good prognosis. Because it is a tumor with predominantly horizontal growth, it tends to erode more than infiltrate. It does not present with remote metastasis.7 It has been known by several different names, usually related to anatomic sites (eg, Ackerman tumor, oral florid papillomatosis, carcinoma cuniculatum).

In the oral cavity, verrucous carcinoma constitutes 2% to 4.5% of all forms of SCC seen mainly in men older than 50 years and also is associated with a high incidence (37.7%) of a second primary tumor mainly in the oral mucosa (eg, tongue, lips, palate, salivary gland).8 Indudharan et al9 reported a case of verrucous carcinoma of the maxillary antrum in a young male patient, which also was a rare entity. Verrucous carcinoma is thought to predominantly affect elderly men. Walvekar et al10 reported a male to female ratio of 3.6 to 1 in patients with verrucous carcinoma, with a mean age of 53.9 years. According to Varshney et al,11 patients may range in age from the fourth to eighth decades of life, with a mean age of 60 years; 80% are male. The etiopathogenesis of verrucous carcinoma is related to the following carcinogens: biologic (eg, human papillomavirus), chemical (eg, smoking), and physical (eg, constant trauma).

Verrucous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of slow-growing, locally spreading tumors. Oral tumors, especially in tobacco chewers, should raise suspicion of verrucous carcinoma, which will enable prompt management of the tumor.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Rock JA, Fisher ER. Florid papillomatosis of the oral cavity and larynx. Arch Otolaryngol. 1960;72:593-598.

- Pattee SF, Bordeaux J, Mahalingam M, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:506-507.

- Buschke A, Lowenstein L. Uber carcinomahnliche condylomata acuminata despenis. Klin Wochenschr. 1925;4:1726-1728.

- Aird I, Johnson HD, Lennox B, et al. Epithelioma cuniculatum: a variety of squamous carcinoma peculiar to the foot. Br J Surg. 1954;42:245-250.

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-21.

- Zanini M, Wulkan C, Paschoal FM, et al. Verrucous carcinoma: a clinical histopathologic variant of squamous cell carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2004;79:619-621.

- Kalsotra P, Manhas M, Sood R. Verrucous carcinoma of hard palate. JK Science. 2000;2:52-54.

- Indudharan R, Das PK, Thida T. Verrucous carcinoma of maxillary antrum. Singapore Med J. 1996;37:559-561.

- Walvekar RR, Chaukar DA, Deshpande MS, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity: a clinical and pathological study of 101 cases. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:47-51.

- Varshney S, Singh J, Saxena RK, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of larynx. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;56:54-56.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon type of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and was first described by Ackerman1 in 1948. Rock and Fisher2 called this condition oral florid papillomatosis. The distinctive features of this tumor are low-grade malignancy, slow growth, local invasiveness, and rarely intraoral and extraoral metastasis. Extraorally, it can occur in any part of the body,3 a common site being the anogenital region. Depending on the area of occurrence, the condition also is known as Buschke-Lowenstein tumor4 or giant condyloma acuminatum (anogenital region) and carcinoma cuniculatum5 (plantar region). The exact etiology of the condition is unknown, though it is associated with human papillomavirus infection, traumatic scars, chronic infection, tobacco, and chemical carcinogens.3 We report a rare case of verrucous carcinoma originating from the buccal mucosa that subsequently spread to involve the lip and cheek as a large cauliflowerlike growth, which is an unusual presentation.

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a painless growth inside the left side of the oral cavity that had developed 5 years prior as a growth on the left buccal mucosa. The lesion gradually increased in size to involve the left oral commissure including the upper and lower lips and the skin of the left cheek; it extended beyond the nasolabial fold in a cauliflowerlike pattern. The lesion was insidious in onset and was not associated with pain, itching, or bleeding. The patient chewed tobacco for the last 40 years, with no similar lesions on any part of the body. On physical examination a warty papilliform lesion was seen on the left buccal mucosa with extension to 2 cm of the upper and lower lip on the left side including the left oral commissure and the skin of the left cheek beyond the nasolabial fold where it appeared as a cauliflowerlike growth measuring 4×5 cm in size (Figure 1). No notable lymphadenopathy was present.

Digital radiographs of the skull (posteroanterior oblique view)(Figure 2) and mandible (left oblique view) showed a lobulated soft-tissue density lesion overlying the left half of the mandible (near the mandibular angle) with involvement of both the upper and lower lips on the left side. However, no obvious underlying bony erosion was noted.

Computed tomography revealed a large soft-tissue mass (41.3×35.3 mm)(Figure 3A) involving the left buccal mucosa with extension into overlying muscle, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. Externally, the lesion was exophytic, irregular, and polypoidal with surface ulceration. Medially, the lesion involved the left oral commissure and parts of the adjoining upper and lower lips. No underlying bony erosion was seen. An enlarged lymph node measuring 20×15 mm was noted in the left upper deep cervical group in the submandibular region (Figure 3B).

Our clinical differential diagnosis included verrucous carcinoma and hypertrophic variety of lupus vulgaris. A 1×2-cm diagnostic incisional biopsy was performed from the cauliflowerlike growth and ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was done from the lymph node. Histopathology revealed a hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium with upward extension of verrucous projections, which was largely superficial to the adjacent epithelium (Figure 4A). In addition to the surface verrucous projections, there was lesion extension into the subepithelial zone in the form of round club-shaped protrusions (Figure 4B). There was no loss of polarity in these downward proliferations. No horn pearl formation was present. Fine-needle aspiration revealed reactive lymphadenitis.

The final diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma was made and the patient was referred to the oncosurgery department for further management.

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, low-grade, well-differentiated SCC of the skin or mucosa presenting with a verrucoid or cauliflowerlike appearance. It shows locally aggressive behavior and has low metastatic potential,6 a low degree of dysplasia, and a good prognosis. Because it is a tumor with predominantly horizontal growth, it tends to erode more than infiltrate. It does not present with remote metastasis.7 It has been known by several different names, usually related to anatomic sites (eg, Ackerman tumor, oral florid papillomatosis, carcinoma cuniculatum).

In the oral cavity, verrucous carcinoma constitutes 2% to 4.5% of all forms of SCC seen mainly in men older than 50 years and also is associated with a high incidence (37.7%) of a second primary tumor mainly in the oral mucosa (eg, tongue, lips, palate, salivary gland).8 Indudharan et al9 reported a case of verrucous carcinoma of the maxillary antrum in a young male patient, which also was a rare entity. Verrucous carcinoma is thought to predominantly affect elderly men. Walvekar et al10 reported a male to female ratio of 3.6 to 1 in patients with verrucous carcinoma, with a mean age of 53.9 years. According to Varshney et al,11 patients may range in age from the fourth to eighth decades of life, with a mean age of 60 years; 80% are male. The etiopathogenesis of verrucous carcinoma is related to the following carcinogens: biologic (eg, human papillomavirus), chemical (eg, smoking), and physical (eg, constant trauma).

Verrucous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of slow-growing, locally spreading tumors. Oral tumors, especially in tobacco chewers, should raise suspicion of verrucous carcinoma, which will enable prompt management of the tumor.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon type of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and was first described by Ackerman1 in 1948. Rock and Fisher2 called this condition oral florid papillomatosis. The distinctive features of this tumor are low-grade malignancy, slow growth, local invasiveness, and rarely intraoral and extraoral metastasis. Extraorally, it can occur in any part of the body,3 a common site being the anogenital region. Depending on the area of occurrence, the condition also is known as Buschke-Lowenstein tumor4 or giant condyloma acuminatum (anogenital region) and carcinoma cuniculatum5 (plantar region). The exact etiology of the condition is unknown, though it is associated with human papillomavirus infection, traumatic scars, chronic infection, tobacco, and chemical carcinogens.3 We report a rare case of verrucous carcinoma originating from the buccal mucosa that subsequently spread to involve the lip and cheek as a large cauliflowerlike growth, which is an unusual presentation.

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a painless growth inside the left side of the oral cavity that had developed 5 years prior as a growth on the left buccal mucosa. The lesion gradually increased in size to involve the left oral commissure including the upper and lower lips and the skin of the left cheek; it extended beyond the nasolabial fold in a cauliflowerlike pattern. The lesion was insidious in onset and was not associated with pain, itching, or bleeding. The patient chewed tobacco for the last 40 years, with no similar lesions on any part of the body. On physical examination a warty papilliform lesion was seen on the left buccal mucosa with extension to 2 cm of the upper and lower lip on the left side including the left oral commissure and the skin of the left cheek beyond the nasolabial fold where it appeared as a cauliflowerlike growth measuring 4×5 cm in size (Figure 1). No notable lymphadenopathy was present.

Digital radiographs of the skull (posteroanterior oblique view)(Figure 2) and mandible (left oblique view) showed a lobulated soft-tissue density lesion overlying the left half of the mandible (near the mandibular angle) with involvement of both the upper and lower lips on the left side. However, no obvious underlying bony erosion was noted.

Computed tomography revealed a large soft-tissue mass (41.3×35.3 mm)(Figure 3A) involving the left buccal mucosa with extension into overlying muscle, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. Externally, the lesion was exophytic, irregular, and polypoidal with surface ulceration. Medially, the lesion involved the left oral commissure and parts of the adjoining upper and lower lips. No underlying bony erosion was seen. An enlarged lymph node measuring 20×15 mm was noted in the left upper deep cervical group in the submandibular region (Figure 3B).

Our clinical differential diagnosis included verrucous carcinoma and hypertrophic variety of lupus vulgaris. A 1×2-cm diagnostic incisional biopsy was performed from the cauliflowerlike growth and ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was done from the lymph node. Histopathology revealed a hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium with upward extension of verrucous projections, which was largely superficial to the adjacent epithelium (Figure 4A). In addition to the surface verrucous projections, there was lesion extension into the subepithelial zone in the form of round club-shaped protrusions (Figure 4B). There was no loss of polarity in these downward proliferations. No horn pearl formation was present. Fine-needle aspiration revealed reactive lymphadenitis.

The final diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma was made and the patient was referred to the oncosurgery department for further management.

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, low-grade, well-differentiated SCC of the skin or mucosa presenting with a verrucoid or cauliflowerlike appearance. It shows locally aggressive behavior and has low metastatic potential,6 a low degree of dysplasia, and a good prognosis. Because it is a tumor with predominantly horizontal growth, it tends to erode more than infiltrate. It does not present with remote metastasis.7 It has been known by several different names, usually related to anatomic sites (eg, Ackerman tumor, oral florid papillomatosis, carcinoma cuniculatum).

In the oral cavity, verrucous carcinoma constitutes 2% to 4.5% of all forms of SCC seen mainly in men older than 50 years and also is associated with a high incidence (37.7%) of a second primary tumor mainly in the oral mucosa (eg, tongue, lips, palate, salivary gland).8 Indudharan et al9 reported a case of verrucous carcinoma of the maxillary antrum in a young male patient, which also was a rare entity. Verrucous carcinoma is thought to predominantly affect elderly men. Walvekar et al10 reported a male to female ratio of 3.6 to 1 in patients with verrucous carcinoma, with a mean age of 53.9 years. According to Varshney et al,11 patients may range in age from the fourth to eighth decades of life, with a mean age of 60 years; 80% are male. The etiopathogenesis of verrucous carcinoma is related to the following carcinogens: biologic (eg, human papillomavirus), chemical (eg, smoking), and physical (eg, constant trauma).

Verrucous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of slow-growing, locally spreading tumors. Oral tumors, especially in tobacco chewers, should raise suspicion of verrucous carcinoma, which will enable prompt management of the tumor.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Rock JA, Fisher ER. Florid papillomatosis of the oral cavity and larynx. Arch Otolaryngol. 1960;72:593-598.

- Pattee SF, Bordeaux J, Mahalingam M, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:506-507.

- Buschke A, Lowenstein L. Uber carcinomahnliche condylomata acuminata despenis. Klin Wochenschr. 1925;4:1726-1728.

- Aird I, Johnson HD, Lennox B, et al. Epithelioma cuniculatum: a variety of squamous carcinoma peculiar to the foot. Br J Surg. 1954;42:245-250.

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-21.

- Zanini M, Wulkan C, Paschoal FM, et al. Verrucous carcinoma: a clinical histopathologic variant of squamous cell carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2004;79:619-621.

- Kalsotra P, Manhas M, Sood R. Verrucous carcinoma of hard palate. JK Science. 2000;2:52-54.

- Indudharan R, Das PK, Thida T. Verrucous carcinoma of maxillary antrum. Singapore Med J. 1996;37:559-561.

- Walvekar RR, Chaukar DA, Deshpande MS, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity: a clinical and pathological study of 101 cases. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:47-51.

- Varshney S, Singh J, Saxena RK, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of larynx. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;56:54-56.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Rock JA, Fisher ER. Florid papillomatosis of the oral cavity and larynx. Arch Otolaryngol. 1960;72:593-598.

- Pattee SF, Bordeaux J, Mahalingam M, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:506-507.

- Buschke A, Lowenstein L. Uber carcinomahnliche condylomata acuminata despenis. Klin Wochenschr. 1925;4:1726-1728.

- Aird I, Johnson HD, Lennox B, et al. Epithelioma cuniculatum: a variety of squamous carcinoma peculiar to the foot. Br J Surg. 1954;42:245-250.

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-21.

- Zanini M, Wulkan C, Paschoal FM, et al. Verrucous carcinoma: a clinical histopathologic variant of squamous cell carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2004;79:619-621.

- Kalsotra P, Manhas M, Sood R. Verrucous carcinoma of hard palate. JK Science. 2000;2:52-54.

- Indudharan R, Das PK, Thida T. Verrucous carcinoma of maxillary antrum. Singapore Med J. 1996;37:559-561.

- Walvekar RR, Chaukar DA, Deshpande MS, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity: a clinical and pathological study of 101 cases. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:47-51.

- Varshney S, Singh J, Saxena RK, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of larynx. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;56:54-56.

Practice Points

- Verrucous carcinoma is a slow-growing tumor that often presents in advanced clinical stages because it is poorly understood and underrecognized, especially in developing countries.

- Good clinicopathological correlation is required in cases of verrucous carcinoma to avoid misdiagnosis and provide appropriate treatment.

- Case-specific management should be considered, as presentation of verrucous carcinoma varies.

- Radiography should be considered to assess for lymph node involvement.

Atherosclerosis severity in diabetes can be predicted by select biomarkers

in patient with type 2 diabetes, results from a long-term analysis of VA patients suggest.

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and oxidation products (OxPs) “can damage vascular cells by different mechanisms,” wrote researchers led by corresponding authors Aramesh Saremi, MD, and Peter D. Reaven, MD, and colleagues. The report appeared online Feb. 1 in Diabetes Care.

“One frequently reported pathway is AGE binding to their purported (and relatively promiscuous) receptors on cells, such as macrophages, vascular endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells, although this has not been consistent for all AGEs. Other mechanisms include, among others, binding to and altering the function of intracellular proteins, the activation of vascular NADPH [nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate] oxidase, and the uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase.”

Noting that data in the current medical literature are lacking with respect to long-term longitudinal associations between plasma levels of AGEs and OxPs on the extent of subclinical atherosclerosis in T2D patients, the researchers set out to determine whether baseline plasma levels of AGEs and OxPs are associated with the extent of carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), coronary artery calcification (CAC), and abdominal aortic artery calcification (AAC) over an average of 10 years of follow-up in the VA Diabetes Trial (VADT). They also examined whether this relationship was altered by intervening improved glucose control (Diabetes Care 2017 Feb. 1. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1875]).

At baseline of the VADT, 411 study participants underwent plasma measurements of methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone, N epsilon–carboxymethyl lysine (CML), N epsilon–carboxyethyl lysine (CEL), 3-deoxyglucosone hydroimidazolone and glyoxal hydroimidazolone (G-H1), 2-aminoadipic acid (2-AAA), and methionine sulfoxide. The mean age of the study subjects was 58 years, 64% were non-Hispanic white, 96% were male, 69% had a history of hypertension, and they had diabetes for a mean of 11 years.

After a mean follow-up of 10 years, the 411 patients underwent ultrasound assessment of CIMT, and computed tomography scanning of CAC and AAC.

In risk factor–adjusted multivariable regression models, G-H1was associated with the extent of CIMT as well as with the extent of CAC (P = .01 for both associations). In addition, 2-AAA was strongly associated with the extent of CAC (P = .03 for continuous variables and P less than .01 for dichotomous variables), and CEL was strongly associated with the extent of AAC (P less than .01).

“These findings suggest that the effect of hyperglycemia and subsequent increased levels of AGEs and OxPs in patients with long-standing T2D may have long-lasting adverse effects on the development of macrovascular complications,” the researchers concluded. They acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that it was conducted in an older, primarily male population. Therefore, “extrapolation of the study findings to other populations must be done with caution,” they wrote. “This study also does not allow us to make a definite claim of causation between AGEs and OxPs with the extent of atherosclerosis.”

The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development funded the study. Additional support was received from National Institutes of Health, the American Diabetes Association, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two study authors, Scott Howell, MS, and Paul J. Beisswenger, MD, disclosed that they are affiliated with PreventAGE Healthcare. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

For a long time the question about how glucose control relates to macrovascular disease has not been easy to answer. There are reports suggesting that glucose control correlates with macrovascular disease later in life, and others that do not make the association so convincing. This paper provides an important link between glucose control and the subsequent development of macrovascular disease. The link is by way of advanced glycation end products as well as oxidative byproducts and how they set the stage for macrovascular disease later on in life. It’s something that clinicians have postulated as being important, but to my knowledge this is one of the only studies to actually show the association.

The investigators used important endpoints like coronary artery calcification and carotid intima-media thickness. I was surprised at how well the relationship between glycosylated end products and oxidative products correlated, but there’s biologic plausibility; it makes sense. Glucose not only glycosates hemoglobin, but glycosates proteins throughout. This provides a logical, stepwise pathway for how the initial glycosylated protein will result years later in macrovascular disease as evidenced by the parameters that were used.

It was interesting to learn from this study that glycosylated end products and oxidative products interact with each other. That’s important, because as blood sugars rise acutely, both oxidative products and glycosylated products are produced. As a result of the oxidative stress that’s created by the sharp rise in blood sugar, endothelial function is affected and more glycosylated proteins are being formed.

Clinically, this study shows the importance of early, aggressive control of diabetes to not allow accumulation of both glycosylated end products and oxidative end products. It demonstrates that accumulation of these byproducts years later seems to relate strongly to macrovascular disease.

The study should be reproduced in younger, less sick patients. That may or may not further clarify the findings, but these findings need to be demonstrated in patients at a much earlier stage as well. We’ve been saying for a long time that early control of diabetes is so important because years later it makes a difference. This is a link to that rationale.

Paul S. Jellinger, MD, MACE, is professor of clinical medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Ft. Lauderdale. He is past president of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and past president of the American College of Endocrinology. Dr. Jellinger provided these comments in an interview.

For a long time the question about how glucose control relates to macrovascular disease has not been easy to answer. There are reports suggesting that glucose control correlates with macrovascular disease later in life, and others that do not make the association so convincing. This paper provides an important link between glucose control and the subsequent development of macrovascular disease. The link is by way of advanced glycation end products as well as oxidative byproducts and how they set the stage for macrovascular disease later on in life. It’s something that clinicians have postulated as being important, but to my knowledge this is one of the only studies to actually show the association.

The investigators used important endpoints like coronary artery calcification and carotid intima-media thickness. I was surprised at how well the relationship between glycosylated end products and oxidative products correlated, but there’s biologic plausibility; it makes sense. Glucose not only glycosates hemoglobin, but glycosates proteins throughout. This provides a logical, stepwise pathway for how the initial glycosylated protein will result years later in macrovascular disease as evidenced by the parameters that were used.

It was interesting to learn from this study that glycosylated end products and oxidative products interact with each other. That’s important, because as blood sugars rise acutely, both oxidative products and glycosylated products are produced. As a result of the oxidative stress that’s created by the sharp rise in blood sugar, endothelial function is affected and more glycosylated proteins are being formed.

Clinically, this study shows the importance of early, aggressive control of diabetes to not allow accumulation of both glycosylated end products and oxidative end products. It demonstrates that accumulation of these byproducts years later seems to relate strongly to macrovascular disease.

The study should be reproduced in younger, less sick patients. That may or may not further clarify the findings, but these findings need to be demonstrated in patients at a much earlier stage as well. We’ve been saying for a long time that early control of diabetes is so important because years later it makes a difference. This is a link to that rationale.

Paul S. Jellinger, MD, MACE, is professor of clinical medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Ft. Lauderdale. He is past president of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and past president of the American College of Endocrinology. Dr. Jellinger provided these comments in an interview.

For a long time the question about how glucose control relates to macrovascular disease has not been easy to answer. There are reports suggesting that glucose control correlates with macrovascular disease later in life, and others that do not make the association so convincing. This paper provides an important link between glucose control and the subsequent development of macrovascular disease. The link is by way of advanced glycation end products as well as oxidative byproducts and how they set the stage for macrovascular disease later on in life. It’s something that clinicians have postulated as being important, but to my knowledge this is one of the only studies to actually show the association.

The investigators used important endpoints like coronary artery calcification and carotid intima-media thickness. I was surprised at how well the relationship between glycosylated end products and oxidative products correlated, but there’s biologic plausibility; it makes sense. Glucose not only glycosates hemoglobin, but glycosates proteins throughout. This provides a logical, stepwise pathway for how the initial glycosylated protein will result years later in macrovascular disease as evidenced by the parameters that were used.

It was interesting to learn from this study that glycosylated end products and oxidative products interact with each other. That’s important, because as blood sugars rise acutely, both oxidative products and glycosylated products are produced. As a result of the oxidative stress that’s created by the sharp rise in blood sugar, endothelial function is affected and more glycosylated proteins are being formed.

Clinically, this study shows the importance of early, aggressive control of diabetes to not allow accumulation of both glycosylated end products and oxidative end products. It demonstrates that accumulation of these byproducts years later seems to relate strongly to macrovascular disease.

The study should be reproduced in younger, less sick patients. That may or may not further clarify the findings, but these findings need to be demonstrated in patients at a much earlier stage as well. We’ve been saying for a long time that early control of diabetes is so important because years later it makes a difference. This is a link to that rationale.

Paul S. Jellinger, MD, MACE, is professor of clinical medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Ft. Lauderdale. He is past president of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and past president of the American College of Endocrinology. Dr. Jellinger provided these comments in an interview.

in patient with type 2 diabetes, results from a long-term analysis of VA patients suggest.

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and oxidation products (OxPs) “can damage vascular cells by different mechanisms,” wrote researchers led by corresponding authors Aramesh Saremi, MD, and Peter D. Reaven, MD, and colleagues. The report appeared online Feb. 1 in Diabetes Care.

“One frequently reported pathway is AGE binding to their purported (and relatively promiscuous) receptors on cells, such as macrophages, vascular endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells, although this has not been consistent for all AGEs. Other mechanisms include, among others, binding to and altering the function of intracellular proteins, the activation of vascular NADPH [nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate] oxidase, and the uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase.”

Noting that data in the current medical literature are lacking with respect to long-term longitudinal associations between plasma levels of AGEs and OxPs on the extent of subclinical atherosclerosis in T2D patients, the researchers set out to determine whether baseline plasma levels of AGEs and OxPs are associated with the extent of carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), coronary artery calcification (CAC), and abdominal aortic artery calcification (AAC) over an average of 10 years of follow-up in the VA Diabetes Trial (VADT). They also examined whether this relationship was altered by intervening improved glucose control (Diabetes Care 2017 Feb. 1. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1875]).

At baseline of the VADT, 411 study participants underwent plasma measurements of methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone, N epsilon–carboxymethyl lysine (CML), N epsilon–carboxyethyl lysine (CEL), 3-deoxyglucosone hydroimidazolone and glyoxal hydroimidazolone (G-H1), 2-aminoadipic acid (2-AAA), and methionine sulfoxide. The mean age of the study subjects was 58 years, 64% were non-Hispanic white, 96% were male, 69% had a history of hypertension, and they had diabetes for a mean of 11 years.

After a mean follow-up of 10 years, the 411 patients underwent ultrasound assessment of CIMT, and computed tomography scanning of CAC and AAC.

In risk factor–adjusted multivariable regression models, G-H1was associated with the extent of CIMT as well as with the extent of CAC (P = .01 for both associations). In addition, 2-AAA was strongly associated with the extent of CAC (P = .03 for continuous variables and P less than .01 for dichotomous variables), and CEL was strongly associated with the extent of AAC (P less than .01).

“These findings suggest that the effect of hyperglycemia and subsequent increased levels of AGEs and OxPs in patients with long-standing T2D may have long-lasting adverse effects on the development of macrovascular complications,” the researchers concluded. They acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that it was conducted in an older, primarily male population. Therefore, “extrapolation of the study findings to other populations must be done with caution,” they wrote. “This study also does not allow us to make a definite claim of causation between AGEs and OxPs with the extent of atherosclerosis.”

The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development funded the study. Additional support was received from National Institutes of Health, the American Diabetes Association, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two study authors, Scott Howell, MS, and Paul J. Beisswenger, MD, disclosed that they are affiliated with PreventAGE Healthcare. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

in patient with type 2 diabetes, results from a long-term analysis of VA patients suggest.

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and oxidation products (OxPs) “can damage vascular cells by different mechanisms,” wrote researchers led by corresponding authors Aramesh Saremi, MD, and Peter D. Reaven, MD, and colleagues. The report appeared online Feb. 1 in Diabetes Care.

“One frequently reported pathway is AGE binding to their purported (and relatively promiscuous) receptors on cells, such as macrophages, vascular endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells, although this has not been consistent for all AGEs. Other mechanisms include, among others, binding to and altering the function of intracellular proteins, the activation of vascular NADPH [nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate] oxidase, and the uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase.”

Noting that data in the current medical literature are lacking with respect to long-term longitudinal associations between plasma levels of AGEs and OxPs on the extent of subclinical atherosclerosis in T2D patients, the researchers set out to determine whether baseline plasma levels of AGEs and OxPs are associated with the extent of carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), coronary artery calcification (CAC), and abdominal aortic artery calcification (AAC) over an average of 10 years of follow-up in the VA Diabetes Trial (VADT). They also examined whether this relationship was altered by intervening improved glucose control (Diabetes Care 2017 Feb. 1. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1875]).

At baseline of the VADT, 411 study participants underwent plasma measurements of methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone, N epsilon–carboxymethyl lysine (CML), N epsilon–carboxyethyl lysine (CEL), 3-deoxyglucosone hydroimidazolone and glyoxal hydroimidazolone (G-H1), 2-aminoadipic acid (2-AAA), and methionine sulfoxide. The mean age of the study subjects was 58 years, 64% were non-Hispanic white, 96% were male, 69% had a history of hypertension, and they had diabetes for a mean of 11 years.

After a mean follow-up of 10 years, the 411 patients underwent ultrasound assessment of CIMT, and computed tomography scanning of CAC and AAC.

In risk factor–adjusted multivariable regression models, G-H1was associated with the extent of CIMT as well as with the extent of CAC (P = .01 for both associations). In addition, 2-AAA was strongly associated with the extent of CAC (P = .03 for continuous variables and P less than .01 for dichotomous variables), and CEL was strongly associated with the extent of AAC (P less than .01).

“These findings suggest that the effect of hyperglycemia and subsequent increased levels of AGEs and OxPs in patients with long-standing T2D may have long-lasting adverse effects on the development of macrovascular complications,” the researchers concluded. They acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that it was conducted in an older, primarily male population. Therefore, “extrapolation of the study findings to other populations must be done with caution,” they wrote. “This study also does not allow us to make a definite claim of causation between AGEs and OxPs with the extent of atherosclerosis.”

The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development funded the study. Additional support was received from National Institutes of Health, the American Diabetes Association, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two study authors, Scott Howell, MS, and Paul J. Beisswenger, MD, disclosed that they are affiliated with PreventAGE Healthcare. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Glyoxal hydroimidazolone was associated with the extent of carotid intima-media thickness as well as with the extent of coronary artery calcification.

Data source: An analysis of 411 patients the VA Diabetes Trial.

Disclosures: The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development funded the study. Additional support was received from National Institutes of Health, the American Diabetes Association, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two study authors, Scott Howell, MS, and Paul J. Beisswenger, MD, disclosed that they are affiliated with PreventAGE Healthcare. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Liver transplantation largely effective in critically ill children

The use of advanced critical care in children and infants with liver failure is justified because orthotopic liver transplantation can be performed on the sickest children and achieve acceptable outcomes, results from a large analysis demonstrated.

“Hand in hand with improved care for critically ill children with liver failure, posttransplant critical care has made tremendous strides,” Abbas Rana, MD, wrote in a study published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons. “Our recipients have gotten sicker while our postoperative outcomes have improved. The question then becomes, have our operative skills and postoperative critical care management kept up with the abilities to keep sick children with liver failure alive? Just because transplantation is now possible in our sickest children, is it justified?”

To find out, Dr. Rana of the division of abdominal transplantation and hepatobiliary surgery at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues retrospectively analyzed United Network for Organ Sharing data from all orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) recipients between Sept. 1, 1987, and June 30, 2015. The analysis paired the liver registry data with data collected by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, and was limited to transplant recipients younger than age 18. The researchers followed a total of 13,723 recipients from date of transplant until either death or the date of last known follow-up (J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Dec 25. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.12.025).

In another part of the study, the researchers retrospectively reviewed the charts of 354 patients under 18 years of age who underwent OLT between March 1, 2002, and June 30, 2015, at Texas Children’s Hospital, including 65 who were admitted to the ICU at the time of transplantation.

In the analysis of national data, the researchers found that the rates of 1-year survival following OLT in children in the ICU improved from 60% in 1987 to 92% in 2013 (P less than .001). The rates of 1-year survival also improved for children on dialysis at the time of transplant (from 50% in 1995 to 95% in 2013; P less than .001) and for those dependent on a mechanical ventilator at the time of transplant (from 49% in 1994 to 94% in 2013; P less than .001). The significant risk factors were two previous transplants (hazard ratio, 4.2), one previous transplant (HR, 2.5), serum sodium greater than 150 mEq/L (HR, 2.0), dialysis or glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (HR, 2.0), mechanical ventilator dependence (HR, 1.8), body weight under 6 kg (HR, 1.8), encephalopathy (HR, 1.8), and annual center volume of fewer than five cases (HR, 1.7).

In the experience at Texas Children’s Hospital, the researchers observed “preserved and successful patient survival outcomes” in many markers of acuity. For example, the 10-year survival rates for patients dependent on mechanical ventilation and dialysis were 85% and 96%, respectively, and reached 100% for those requiring therapeutic plasma exchange, molescular adsorbent recirculating system (MARS) liver dialysis, and vasopressors.

“Our collective ability to keep sick children alive with liver failure has improved considerably over the years,” the researchers wrote. “Keeping pace, this analysis demonstrates that the posttransplant outcomes have also improved dramatically. The survival outcomes are comparable to the general population, justifying the use of scarce donors. Although we cannot declare in absolute that no child should be left behind, we can demonstrate acceptable outcomes to date and urge the continual revisiting of our concepts of futility.

“We have learned throughout our experience that almost every child with end-stage liver disease and acute liver failure should be offered liver replacement, as long as the vasoactive medication and mechanical support are not maximized prior to the initiation of the OLT procedure. Every effort should be made to transplant our sickest children.”

This study was supported by the Cade R. Alpard Foundation. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The use of advanced critical care in children and infants with liver failure is justified because orthotopic liver transplantation can be performed on the sickest children and achieve acceptable outcomes, results from a large analysis demonstrated.

“Hand in hand with improved care for critically ill children with liver failure, posttransplant critical care has made tremendous strides,” Abbas Rana, MD, wrote in a study published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons. “Our recipients have gotten sicker while our postoperative outcomes have improved. The question then becomes, have our operative skills and postoperative critical care management kept up with the abilities to keep sick children with liver failure alive? Just because transplantation is now possible in our sickest children, is it justified?”

To find out, Dr. Rana of the division of abdominal transplantation and hepatobiliary surgery at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues retrospectively analyzed United Network for Organ Sharing data from all orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) recipients between Sept. 1, 1987, and June 30, 2015. The analysis paired the liver registry data with data collected by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, and was limited to transplant recipients younger than age 18. The researchers followed a total of 13,723 recipients from date of transplant until either death or the date of last known follow-up (J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Dec 25. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.12.025).

In another part of the study, the researchers retrospectively reviewed the charts of 354 patients under 18 years of age who underwent OLT between March 1, 2002, and June 30, 2015, at Texas Children’s Hospital, including 65 who were admitted to the ICU at the time of transplantation.

In the analysis of national data, the researchers found that the rates of 1-year survival following OLT in children in the ICU improved from 60% in 1987 to 92% in 2013 (P less than .001). The rates of 1-year survival also improved for children on dialysis at the time of transplant (from 50% in 1995 to 95% in 2013; P less than .001) and for those dependent on a mechanical ventilator at the time of transplant (from 49% in 1994 to 94% in 2013; P less than .001). The significant risk factors were two previous transplants (hazard ratio, 4.2), one previous transplant (HR, 2.5), serum sodium greater than 150 mEq/L (HR, 2.0), dialysis or glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (HR, 2.0), mechanical ventilator dependence (HR, 1.8), body weight under 6 kg (HR, 1.8), encephalopathy (HR, 1.8), and annual center volume of fewer than five cases (HR, 1.7).

In the experience at Texas Children’s Hospital, the researchers observed “preserved and successful patient survival outcomes” in many markers of acuity. For example, the 10-year survival rates for patients dependent on mechanical ventilation and dialysis were 85% and 96%, respectively, and reached 100% for those requiring therapeutic plasma exchange, molescular adsorbent recirculating system (MARS) liver dialysis, and vasopressors.

“Our collective ability to keep sick children alive with liver failure has improved considerably over the years,” the researchers wrote. “Keeping pace, this analysis demonstrates that the posttransplant outcomes have also improved dramatically. The survival outcomes are comparable to the general population, justifying the use of scarce donors. Although we cannot declare in absolute that no child should be left behind, we can demonstrate acceptable outcomes to date and urge the continual revisiting of our concepts of futility.