User login

Four factors signal complicated appendicitis

LAS VEGAS – Four clinical and imaging characteristics can preoperatively identify cases of complicated appendicitis, potentially saving many from long and unnecessary courses of antibiotics.

In a retrospective study, increasing age and days of pain, combined with the size of the appendix and the presence of an appendicolith on imaging were significantly associated with a histopathologic diagnosis of complicated appendicitis, Jonathan Imran, MD, said at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

“A lot of patients get tagged as complicated but they really aren’t,” said Dr. Imran, a surgical resident at the University of Texas, Dallas. “This definition then guides clinical assessment and has a profound impact on postoperative antibiotics and length of stay. Despite its common use, intraoperative assessment of complicated appendicitis remains subjective.”

On the other hand, the standard of a histopathologic diagnosis isn’t available during surgery to guide postoperative management. Dr. Imran and his colleagues sought to create a risk assessment tool to identify patients at risk of complicated appendicitis on the basis of clinical and imaging findings.

They retrospectively examined 1,066 patients who underwent appendectomy at a single institution from 2011 to 2013. They compared the intraoperative designations of simple and complicated appendicitis with the histopathologic diagnosis.

Of the 827 patients designated as having simple appendicitis during surgery, 763 (93%) were confirmed by histopathology. The remainder had complicated appendicitis on histopathology.

Of the 239 patients designated as having complicated appendicitis during surgery, 143 (60%) were confirmed by histopathology. The remainder actually had simple appendicitis. Of these 96 patients, 60% went on to have prolonged courses of antibiotics that, by definition, were unnecessary.

The team then looked at 30 patient variables in an attempt to construct a prediction tool. Among the significant associations with a complicated presentation were older age, type 2 diabetes, longer duration of pain, less lower left quadrant pain, higher median temperature, higher serum creatinine, longer time from presentation of symptoms to surgery, larger appendix diameter, abscess, and the presence of an appendicolith.

Four of these factors remained significantly associated with complicated appendicitis in a multivariate regression analysis:

• Age (per 10 years) – odds ratio, 1.25.

• Duration of pain (per day) – OR, 1.21.

• Appendix diameter on imaging (per mm) – OR, 1.10.

• Presence of an appendicolith on imaging – OR, 1.65.

These findings are the basis of a preoperative risk assessment score the team is developing, which will be prospectively tested.

“We hope that these predictors, in combination with improved intraoperative grading, could be used to achieve a more timely and accurate diagnosis of complicated appendicitis,” Dr. Imran said.

He had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

LAS VEGAS – Four clinical and imaging characteristics can preoperatively identify cases of complicated appendicitis, potentially saving many from long and unnecessary courses of antibiotics.

In a retrospective study, increasing age and days of pain, combined with the size of the appendix and the presence of an appendicolith on imaging were significantly associated with a histopathologic diagnosis of complicated appendicitis, Jonathan Imran, MD, said at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

“A lot of patients get tagged as complicated but they really aren’t,” said Dr. Imran, a surgical resident at the University of Texas, Dallas. “This definition then guides clinical assessment and has a profound impact on postoperative antibiotics and length of stay. Despite its common use, intraoperative assessment of complicated appendicitis remains subjective.”

On the other hand, the standard of a histopathologic diagnosis isn’t available during surgery to guide postoperative management. Dr. Imran and his colleagues sought to create a risk assessment tool to identify patients at risk of complicated appendicitis on the basis of clinical and imaging findings.

They retrospectively examined 1,066 patients who underwent appendectomy at a single institution from 2011 to 2013. They compared the intraoperative designations of simple and complicated appendicitis with the histopathologic diagnosis.

Of the 827 patients designated as having simple appendicitis during surgery, 763 (93%) were confirmed by histopathology. The remainder had complicated appendicitis on histopathology.

Of the 239 patients designated as having complicated appendicitis during surgery, 143 (60%) were confirmed by histopathology. The remainder actually had simple appendicitis. Of these 96 patients, 60% went on to have prolonged courses of antibiotics that, by definition, were unnecessary.

The team then looked at 30 patient variables in an attempt to construct a prediction tool. Among the significant associations with a complicated presentation were older age, type 2 diabetes, longer duration of pain, less lower left quadrant pain, higher median temperature, higher serum creatinine, longer time from presentation of symptoms to surgery, larger appendix diameter, abscess, and the presence of an appendicolith.

Four of these factors remained significantly associated with complicated appendicitis in a multivariate regression analysis:

• Age (per 10 years) – odds ratio, 1.25.

• Duration of pain (per day) – OR, 1.21.

• Appendix diameter on imaging (per mm) – OR, 1.10.

• Presence of an appendicolith on imaging – OR, 1.65.

These findings are the basis of a preoperative risk assessment score the team is developing, which will be prospectively tested.

“We hope that these predictors, in combination with improved intraoperative grading, could be used to achieve a more timely and accurate diagnosis of complicated appendicitis,” Dr. Imran said.

He had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

LAS VEGAS – Four clinical and imaging characteristics can preoperatively identify cases of complicated appendicitis, potentially saving many from long and unnecessary courses of antibiotics.

In a retrospective study, increasing age and days of pain, combined with the size of the appendix and the presence of an appendicolith on imaging were significantly associated with a histopathologic diagnosis of complicated appendicitis, Jonathan Imran, MD, said at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

“A lot of patients get tagged as complicated but they really aren’t,” said Dr. Imran, a surgical resident at the University of Texas, Dallas. “This definition then guides clinical assessment and has a profound impact on postoperative antibiotics and length of stay. Despite its common use, intraoperative assessment of complicated appendicitis remains subjective.”

On the other hand, the standard of a histopathologic diagnosis isn’t available during surgery to guide postoperative management. Dr. Imran and his colleagues sought to create a risk assessment tool to identify patients at risk of complicated appendicitis on the basis of clinical and imaging findings.

They retrospectively examined 1,066 patients who underwent appendectomy at a single institution from 2011 to 2013. They compared the intraoperative designations of simple and complicated appendicitis with the histopathologic diagnosis.

Of the 827 patients designated as having simple appendicitis during surgery, 763 (93%) were confirmed by histopathology. The remainder had complicated appendicitis on histopathology.

Of the 239 patients designated as having complicated appendicitis during surgery, 143 (60%) were confirmed by histopathology. The remainder actually had simple appendicitis. Of these 96 patients, 60% went on to have prolonged courses of antibiotics that, by definition, were unnecessary.

The team then looked at 30 patient variables in an attempt to construct a prediction tool. Among the significant associations with a complicated presentation were older age, type 2 diabetes, longer duration of pain, less lower left quadrant pain, higher median temperature, higher serum creatinine, longer time from presentation of symptoms to surgery, larger appendix diameter, abscess, and the presence of an appendicolith.

Four of these factors remained significantly associated with complicated appendicitis in a multivariate regression analysis:

• Age (per 10 years) – odds ratio, 1.25.

• Duration of pain (per day) – OR, 1.21.

• Appendix diameter on imaging (per mm) – OR, 1.10.

• Presence of an appendicolith on imaging – OR, 1.65.

These findings are the basis of a preoperative risk assessment score the team is developing, which will be prospectively tested.

“We hope that these predictors, in combination with improved intraoperative grading, could be used to achieve a more timely and accurate diagnosis of complicated appendicitis,” Dr. Imran said.

He had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

Key clinical point: Two clinical signs and two imaging findings can help identify patients with complicated appendicitis.

Major finding: Older age, days of pain, appendix diameter, and the presence of an appendicolith significantly predicted a complicated presentation.

Data source: The retrospective study comprised 1,066 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Imran had no financial disclosures.

MDS gene mutations predict response to HSCT

Genetic mutations in blood samples may predict outcomes and guide treatment for patients of all ages who have myelodysplastic syndrome and are undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, according to a report published online Feb. 8 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation is the only potentially curative therapy currently available for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), but mortality due to relapse and to transplant-related complications is high. “Predicting which patients are most likely to benefit from transplantation is thus a central challenge,” and identifying patients most likely to relapse could help clinicians refine conditioning regimens and relapse-prevention strategies, said R. Coleman Lindsley, MD, PhD, of the division of hematological malignancies, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and his associates.

The analyses included targeted sequencing of 129 genes known or suspected to be involved in the pathogenesis of myeloid cancers or syndromes related to bone marrow failure. Approximately 80% of the study participants were found to have at least one such driver mutation, with a median of two mutations per patient.

Mutations in the TP53 gene turned out to be the single most powerful predictor of survival after transplantation, independent of factors such as patient age, performance status, and hematologic variables. Moreover, intensive (myeloablative) conditioning regimens did not attenuate this effect, “a finding that is consistent with clinical and experimental evidence showing TP53 mutation-mediated chemoresistance,” Dr. Lindsley and his associates said.

“Our data suggest that escalating the intensity of the conditioning regimen in order to improve outcomes in patients with TP53-mutated MDS will not be successful. ... These patients, who have an exceptionally high risk of relapse-related death after transplantation, should be considered for investigative approaches to conditioning or new relapse-prevention strategies after transplantation,” they added.

Among patients over age 40, mutations in the RAS pathway were associated with a significantly elevated risk of early relapse – an outcome that might be ameliorated by more intensive conditioning. “RAS-pathway mutations may thus reflect the presence of low-volume but biologically transformed disease that, without adequate cytoreduction before transplantation, outpaces the development of effective graft-versus-leukemia activity,” the investigators said.

However, this association between RAS mutations and relapse was not seen in patients younger than age 40 years, they noted.

Conversely, JAK2 mutations were associated with a higher rate of death without relapse but not a higher rate of relapse. And this association was not affected by conditioning intensity. Although the mechanism of such an effect is not yet known, early death without relapse may be driven by factors that are susceptible to targeting by JAK2 inhibitors. In addition, minimizing treatment toxicity should be the focus of treatment in patients who carry JAK2 mutations, since their poor survival rate is driven by deaths unrelated to relapse, Dr. Lindsley and his associates said.

Mutations in the PPM1D gene, especially when accompanied by TP53 mutations, were strongly associated with previous exposure to leukemogenic therapies. “PPM1D encodes a serine-threonine protein phosphatase that regulates the cellular response to environmental stress, in part by means of inhibition of TP53 activity, which suggests that TP53 and PPM1D mutations represent convergent mechanisms of clonal survival in the context of leukemogenic exposures,” the investigators said.

“Our results... provide strong genetic evidence of the role of PPM1D mutations in the pathogenesis of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes.”

Mutations in the SBDS gene, which has been linked to Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, were “unexpectedly common” in young-adult patients and were associated with a poor prognosis. (Shwachman-Diamond syndrome is a rare congenital syndrome of bone-marrow failure.) This finding suggests that early stem-cell transplantation should be considered for patients who have this disorder, since transplantation after full-blown MDS develops “may not offer long-term benefit.”

Genetic mutations in blood samples may predict outcomes and guide treatment for patients of all ages who have myelodysplastic syndrome and are undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, according to a report published online Feb. 8 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation is the only potentially curative therapy currently available for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), but mortality due to relapse and to transplant-related complications is high. “Predicting which patients are most likely to benefit from transplantation is thus a central challenge,” and identifying patients most likely to relapse could help clinicians refine conditioning regimens and relapse-prevention strategies, said R. Coleman Lindsley, MD, PhD, of the division of hematological malignancies, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and his associates.

The analyses included targeted sequencing of 129 genes known or suspected to be involved in the pathogenesis of myeloid cancers or syndromes related to bone marrow failure. Approximately 80% of the study participants were found to have at least one such driver mutation, with a median of two mutations per patient.

Mutations in the TP53 gene turned out to be the single most powerful predictor of survival after transplantation, independent of factors such as patient age, performance status, and hematologic variables. Moreover, intensive (myeloablative) conditioning regimens did not attenuate this effect, “a finding that is consistent with clinical and experimental evidence showing TP53 mutation-mediated chemoresistance,” Dr. Lindsley and his associates said.

“Our data suggest that escalating the intensity of the conditioning regimen in order to improve outcomes in patients with TP53-mutated MDS will not be successful. ... These patients, who have an exceptionally high risk of relapse-related death after transplantation, should be considered for investigative approaches to conditioning or new relapse-prevention strategies after transplantation,” they added.

Among patients over age 40, mutations in the RAS pathway were associated with a significantly elevated risk of early relapse – an outcome that might be ameliorated by more intensive conditioning. “RAS-pathway mutations may thus reflect the presence of low-volume but biologically transformed disease that, without adequate cytoreduction before transplantation, outpaces the development of effective graft-versus-leukemia activity,” the investigators said.

However, this association between RAS mutations and relapse was not seen in patients younger than age 40 years, they noted.

Conversely, JAK2 mutations were associated with a higher rate of death without relapse but not a higher rate of relapse. And this association was not affected by conditioning intensity. Although the mechanism of such an effect is not yet known, early death without relapse may be driven by factors that are susceptible to targeting by JAK2 inhibitors. In addition, minimizing treatment toxicity should be the focus of treatment in patients who carry JAK2 mutations, since their poor survival rate is driven by deaths unrelated to relapse, Dr. Lindsley and his associates said.

Mutations in the PPM1D gene, especially when accompanied by TP53 mutations, were strongly associated with previous exposure to leukemogenic therapies. “PPM1D encodes a serine-threonine protein phosphatase that regulates the cellular response to environmental stress, in part by means of inhibition of TP53 activity, which suggests that TP53 and PPM1D mutations represent convergent mechanisms of clonal survival in the context of leukemogenic exposures,” the investigators said.

“Our results... provide strong genetic evidence of the role of PPM1D mutations in the pathogenesis of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes.”

Mutations in the SBDS gene, which has been linked to Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, were “unexpectedly common” in young-adult patients and were associated with a poor prognosis. (Shwachman-Diamond syndrome is a rare congenital syndrome of bone-marrow failure.) This finding suggests that early stem-cell transplantation should be considered for patients who have this disorder, since transplantation after full-blown MDS develops “may not offer long-term benefit.”

Genetic mutations in blood samples may predict outcomes and guide treatment for patients of all ages who have myelodysplastic syndrome and are undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, according to a report published online Feb. 8 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation is the only potentially curative therapy currently available for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), but mortality due to relapse and to transplant-related complications is high. “Predicting which patients are most likely to benefit from transplantation is thus a central challenge,” and identifying patients most likely to relapse could help clinicians refine conditioning regimens and relapse-prevention strategies, said R. Coleman Lindsley, MD, PhD, of the division of hematological malignancies, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and his associates.

The analyses included targeted sequencing of 129 genes known or suspected to be involved in the pathogenesis of myeloid cancers or syndromes related to bone marrow failure. Approximately 80% of the study participants were found to have at least one such driver mutation, with a median of two mutations per patient.

Mutations in the TP53 gene turned out to be the single most powerful predictor of survival after transplantation, independent of factors such as patient age, performance status, and hematologic variables. Moreover, intensive (myeloablative) conditioning regimens did not attenuate this effect, “a finding that is consistent with clinical and experimental evidence showing TP53 mutation-mediated chemoresistance,” Dr. Lindsley and his associates said.

“Our data suggest that escalating the intensity of the conditioning regimen in order to improve outcomes in patients with TP53-mutated MDS will not be successful. ... These patients, who have an exceptionally high risk of relapse-related death after transplantation, should be considered for investigative approaches to conditioning or new relapse-prevention strategies after transplantation,” they added.

Among patients over age 40, mutations in the RAS pathway were associated with a significantly elevated risk of early relapse – an outcome that might be ameliorated by more intensive conditioning. “RAS-pathway mutations may thus reflect the presence of low-volume but biologically transformed disease that, without adequate cytoreduction before transplantation, outpaces the development of effective graft-versus-leukemia activity,” the investigators said.

However, this association between RAS mutations and relapse was not seen in patients younger than age 40 years, they noted.

Conversely, JAK2 mutations were associated with a higher rate of death without relapse but not a higher rate of relapse. And this association was not affected by conditioning intensity. Although the mechanism of such an effect is not yet known, early death without relapse may be driven by factors that are susceptible to targeting by JAK2 inhibitors. In addition, minimizing treatment toxicity should be the focus of treatment in patients who carry JAK2 mutations, since their poor survival rate is driven by deaths unrelated to relapse, Dr. Lindsley and his associates said.

Mutations in the PPM1D gene, especially when accompanied by TP53 mutations, were strongly associated with previous exposure to leukemogenic therapies. “PPM1D encodes a serine-threonine protein phosphatase that regulates the cellular response to environmental stress, in part by means of inhibition of TP53 activity, which suggests that TP53 and PPM1D mutations represent convergent mechanisms of clonal survival in the context of leukemogenic exposures,” the investigators said.

“Our results... provide strong genetic evidence of the role of PPM1D mutations in the pathogenesis of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes.”

Mutations in the SBDS gene, which has been linked to Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, were “unexpectedly common” in young-adult patients and were associated with a poor prognosis. (Shwachman-Diamond syndrome is a rare congenital syndrome of bone-marrow failure.) This finding suggests that early stem-cell transplantation should be considered for patients who have this disorder, since transplantation after full-blown MDS develops “may not offer long-term benefit.”

Key clinical point: Genetic mutations in blood samples may predict outcomes and guide treatment for patients of all ages who have myelodysplastic syndrome and are undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

Key numerical finding: Approximately 80% of the study participants were found to have at least one driver mutation, with a median of two such mutations per patient.

Data source: Targeted mutational analyses of banked blood samples from 1,514 patients treated at 130 transplantation centers in the U.S. and Germany.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Edward P. Evans Foundation, the Harvard Catalyst Program, the National Marrow Donor Program, the National Institutes of Health, and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. Dr. Lindsley reported ties to Takeda, and one of his associates reported ties to Celgene, Genoptix, and H3 Biomedicine.

New topical agents for acne rolling out

WAILEA, HAWAII – The Food and Drug Administration’s approval of adapalene gel 0.1% as an over-the-counter treatment for acne is a potential game changer that could lead to revision of guideline-recommended treatment algorithms, Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, predicted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar.

In addition to discussing the implications of the FDA’s unprecedented approval of a full prescription–strength topical retinoid for OTC use, he highlighted other developments in topical therapy for acne, including the 2016 approval of dapsone 7.5% gel, as well as several agents with novel mechanisms of action now wending their way through the developmental pipeline.

“This development could be very interesting from an access standpoint and in terms of how physicians write prescriptions for retinoids, in light of the copays for other agents,” said Dr. Eichenfield, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego.

“We know that with other retinoids, access is an issue. In Southern California, for example, we have strong pharmacy benefits’ managers for the insurance companies, and they’re very restrictive. It seems like every 3 months, they change the tiering of the different retinoids. It’s something we have to work on to get our patients a fair price,” he explained.

Dapsone 7.5% gel, marketed as Aczone Gel, 7.5% by Allergan, is a once-daily reformulation of the older 5% product administered twice daily. It received FDA approval for use in patients aged 12 years and older based on two 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trials totaling more than 4,300 acne patients. The studies showed the stronger once-daily product was extremely well tolerated, with application site dryness and itching rates similar to placebo. In terms of efficacy, a Global Acne Assessment Score of 0 or 1 with at least a 2-grade improvement was achieved in 30% of patients assigned to dapsone 7.5% gel, compared with 21% of vehicle-treated controls.

Dr. Eichenfield was lead investigator in a recently published positive phase IIb, randomized, vehicle-controlled study of a topical nitric oxide-releasing agent for acne known for now as SB204 (J Drugs Dermatol. 2016 Dec 1;15[12]:1496-502). The product has both antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, bacteria don’t develop resistance to it, and there is no significant systemic absorption.

“I haven’t seen the data yet. We’ll have to wait and see whether this agent continues to go forward,” Dr. Eichenfield said at the meeting, sponsored by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Research Foundation.

In its press release, Novan stated that the company believes “its cash on hand is sufficient to fund operations at least through the end of 2017, of which the allocation of capital will be dependent upon further assessment of the SB204 phase III trial results.”

DRM01 is a novel topical inhibitor of acetyl coenzyme-A carboxylase, an enzyme involved in synthesis of the fatty acids that are an essential component of sebum. A phase IIb randomized trial in 420 adult acne patients yielded positive results, according to Dermira, which is developing DRM01. The company plans to begin a pivotal phase III trial in the first half of 2017.

Another investigational topical acne therapy to keep an eye on is cortexolone. This peripherally selective antiandrogenic agent is under development by Cassiopea* Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Eichenfield’s financial disclosures included serving as an investigator for Novan, Regeneron, Galderma, and Astellas Pharma US; and as a consultant for Galderma, Genentech, Janssen, Lilly, Otsuka, and TopMD.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

[email protected]

*An earlier version of this article misstated the company that developed the peripherally selective antiandrogenic agent.

WAILEA, HAWAII – The Food and Drug Administration’s approval of adapalene gel 0.1% as an over-the-counter treatment for acne is a potential game changer that could lead to revision of guideline-recommended treatment algorithms, Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, predicted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar.

In addition to discussing the implications of the FDA’s unprecedented approval of a full prescription–strength topical retinoid for OTC use, he highlighted other developments in topical therapy for acne, including the 2016 approval of dapsone 7.5% gel, as well as several agents with novel mechanisms of action now wending their way through the developmental pipeline.

“This development could be very interesting from an access standpoint and in terms of how physicians write prescriptions for retinoids, in light of the copays for other agents,” said Dr. Eichenfield, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego.

“We know that with other retinoids, access is an issue. In Southern California, for example, we have strong pharmacy benefits’ managers for the insurance companies, and they’re very restrictive. It seems like every 3 months, they change the tiering of the different retinoids. It’s something we have to work on to get our patients a fair price,” he explained.

Dapsone 7.5% gel, marketed as Aczone Gel, 7.5% by Allergan, is a once-daily reformulation of the older 5% product administered twice daily. It received FDA approval for use in patients aged 12 years and older based on two 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trials totaling more than 4,300 acne patients. The studies showed the stronger once-daily product was extremely well tolerated, with application site dryness and itching rates similar to placebo. In terms of efficacy, a Global Acne Assessment Score of 0 or 1 with at least a 2-grade improvement was achieved in 30% of patients assigned to dapsone 7.5% gel, compared with 21% of vehicle-treated controls.

Dr. Eichenfield was lead investigator in a recently published positive phase IIb, randomized, vehicle-controlled study of a topical nitric oxide-releasing agent for acne known for now as SB204 (J Drugs Dermatol. 2016 Dec 1;15[12]:1496-502). The product has both antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, bacteria don’t develop resistance to it, and there is no significant systemic absorption.

“I haven’t seen the data yet. We’ll have to wait and see whether this agent continues to go forward,” Dr. Eichenfield said at the meeting, sponsored by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Research Foundation.

In its press release, Novan stated that the company believes “its cash on hand is sufficient to fund operations at least through the end of 2017, of which the allocation of capital will be dependent upon further assessment of the SB204 phase III trial results.”

DRM01 is a novel topical inhibitor of acetyl coenzyme-A carboxylase, an enzyme involved in synthesis of the fatty acids that are an essential component of sebum. A phase IIb randomized trial in 420 adult acne patients yielded positive results, according to Dermira, which is developing DRM01. The company plans to begin a pivotal phase III trial in the first half of 2017.

Another investigational topical acne therapy to keep an eye on is cortexolone. This peripherally selective antiandrogenic agent is under development by Cassiopea* Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Eichenfield’s financial disclosures included serving as an investigator for Novan, Regeneron, Galderma, and Astellas Pharma US; and as a consultant for Galderma, Genentech, Janssen, Lilly, Otsuka, and TopMD.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

[email protected]

*An earlier version of this article misstated the company that developed the peripherally selective antiandrogenic agent.

WAILEA, HAWAII – The Food and Drug Administration’s approval of adapalene gel 0.1% as an over-the-counter treatment for acne is a potential game changer that could lead to revision of guideline-recommended treatment algorithms, Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, predicted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar.

In addition to discussing the implications of the FDA’s unprecedented approval of a full prescription–strength topical retinoid for OTC use, he highlighted other developments in topical therapy for acne, including the 2016 approval of dapsone 7.5% gel, as well as several agents with novel mechanisms of action now wending their way through the developmental pipeline.

“This development could be very interesting from an access standpoint and in terms of how physicians write prescriptions for retinoids, in light of the copays for other agents,” said Dr. Eichenfield, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego.

“We know that with other retinoids, access is an issue. In Southern California, for example, we have strong pharmacy benefits’ managers for the insurance companies, and they’re very restrictive. It seems like every 3 months, they change the tiering of the different retinoids. It’s something we have to work on to get our patients a fair price,” he explained.

Dapsone 7.5% gel, marketed as Aczone Gel, 7.5% by Allergan, is a once-daily reformulation of the older 5% product administered twice daily. It received FDA approval for use in patients aged 12 years and older based on two 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trials totaling more than 4,300 acne patients. The studies showed the stronger once-daily product was extremely well tolerated, with application site dryness and itching rates similar to placebo. In terms of efficacy, a Global Acne Assessment Score of 0 or 1 with at least a 2-grade improvement was achieved in 30% of patients assigned to dapsone 7.5% gel, compared with 21% of vehicle-treated controls.

Dr. Eichenfield was lead investigator in a recently published positive phase IIb, randomized, vehicle-controlled study of a topical nitric oxide-releasing agent for acne known for now as SB204 (J Drugs Dermatol. 2016 Dec 1;15[12]:1496-502). The product has both antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, bacteria don’t develop resistance to it, and there is no significant systemic absorption.

“I haven’t seen the data yet. We’ll have to wait and see whether this agent continues to go forward,” Dr. Eichenfield said at the meeting, sponsored by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Research Foundation.

In its press release, Novan stated that the company believes “its cash on hand is sufficient to fund operations at least through the end of 2017, of which the allocation of capital will be dependent upon further assessment of the SB204 phase III trial results.”

DRM01 is a novel topical inhibitor of acetyl coenzyme-A carboxylase, an enzyme involved in synthesis of the fatty acids that are an essential component of sebum. A phase IIb randomized trial in 420 adult acne patients yielded positive results, according to Dermira, which is developing DRM01. The company plans to begin a pivotal phase III trial in the first half of 2017.

Another investigational topical acne therapy to keep an eye on is cortexolone. This peripherally selective antiandrogenic agent is under development by Cassiopea* Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Eichenfield’s financial disclosures included serving as an investigator for Novan, Regeneron, Galderma, and Astellas Pharma US; and as a consultant for Galderma, Genentech, Janssen, Lilly, Otsuka, and TopMD.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

[email protected]

*An earlier version of this article misstated the company that developed the peripherally selective antiandrogenic agent.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Guidelines needed for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery

A new study of pregnant Medicaid patients in Pennsylvania found that 12% filled prescriptions for opioids within 5 days of vaginal delivery, even though fewer than one-third of the women had pain-inducing conditions.

“Our study raises the question: Why is outpatient opioid use not rare after vaginal delivery?” lead author Marian Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “Outpatient opioid prescriptions after a hospitalization may be one potential pathway to opioid use disorder. I hope the study will prompt some thought about why opioids are being prescribed for women after vaginal delivery and how to best manage postdelivery pain. This is especially important in areas of the country that have extraordinarily high rates of opioid use disorder.”

A total of 12% of the women (18,131) filled an outpatient prescription for an opioid with 5 days of giving birth. Of those, just 28.2% (5,110) had one or more conditions that cause an increased level of pain after delivery, such as bilateral tubal ligation, certain kinds of lacerations, and episiotomy.

During the first 5 days after birth, the most commonly prescribed opioid was oxycodone-acetaminophen (53.3%), followed by acetaminophen-codeine (20.5%), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (19.6%).

Of the 18,131 women with an early postdelivery opioid prescription, 14% (2,592) filled at least one other opioid prescription within 6-60 days – that’s 1.6% of all the women in the study.

“On a positive note, we saw the supply of opioid prescriptions was generally short at 3-7 days,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

The researchers linked tobacco use and a mental health condition (both adjusted odds ratio 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.4) to a higher risk of filling a prescription without being diagnosed with a pain-causing disorder. They also found an association between substance use disorder (not related to opioids) and a higher risk of these types of prescriptions, but only for filling a second opioid prescription in the 6-60 day period (aOR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6).

The researchers called for national guidelines regarding the use of opioids after birth.

“Several organizations have developed opioid prescribing guidelines for chronic and acute pain,” Dr. Jarlenski said. “These guidelines are necessary because the risk of opioid use disorder and subsequent overdose events is well established. Although delivery is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United States, there are no national guidelines for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery.”

The study was partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study of pregnant Medicaid patients in Pennsylvania found that 12% filled prescriptions for opioids within 5 days of vaginal delivery, even though fewer than one-third of the women had pain-inducing conditions.

“Our study raises the question: Why is outpatient opioid use not rare after vaginal delivery?” lead author Marian Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “Outpatient opioid prescriptions after a hospitalization may be one potential pathway to opioid use disorder. I hope the study will prompt some thought about why opioids are being prescribed for women after vaginal delivery and how to best manage postdelivery pain. This is especially important in areas of the country that have extraordinarily high rates of opioid use disorder.”

A total of 12% of the women (18,131) filled an outpatient prescription for an opioid with 5 days of giving birth. Of those, just 28.2% (5,110) had one or more conditions that cause an increased level of pain after delivery, such as bilateral tubal ligation, certain kinds of lacerations, and episiotomy.

During the first 5 days after birth, the most commonly prescribed opioid was oxycodone-acetaminophen (53.3%), followed by acetaminophen-codeine (20.5%), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (19.6%).

Of the 18,131 women with an early postdelivery opioid prescription, 14% (2,592) filled at least one other opioid prescription within 6-60 days – that’s 1.6% of all the women in the study.

“On a positive note, we saw the supply of opioid prescriptions was generally short at 3-7 days,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

The researchers linked tobacco use and a mental health condition (both adjusted odds ratio 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.4) to a higher risk of filling a prescription without being diagnosed with a pain-causing disorder. They also found an association between substance use disorder (not related to opioids) and a higher risk of these types of prescriptions, but only for filling a second opioid prescription in the 6-60 day period (aOR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6).

The researchers called for national guidelines regarding the use of opioids after birth.

“Several organizations have developed opioid prescribing guidelines for chronic and acute pain,” Dr. Jarlenski said. “These guidelines are necessary because the risk of opioid use disorder and subsequent overdose events is well established. Although delivery is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United States, there are no national guidelines for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery.”

The study was partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study of pregnant Medicaid patients in Pennsylvania found that 12% filled prescriptions for opioids within 5 days of vaginal delivery, even though fewer than one-third of the women had pain-inducing conditions.

“Our study raises the question: Why is outpatient opioid use not rare after vaginal delivery?” lead author Marian Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “Outpatient opioid prescriptions after a hospitalization may be one potential pathway to opioid use disorder. I hope the study will prompt some thought about why opioids are being prescribed for women after vaginal delivery and how to best manage postdelivery pain. This is especially important in areas of the country that have extraordinarily high rates of opioid use disorder.”

A total of 12% of the women (18,131) filled an outpatient prescription for an opioid with 5 days of giving birth. Of those, just 28.2% (5,110) had one or more conditions that cause an increased level of pain after delivery, such as bilateral tubal ligation, certain kinds of lacerations, and episiotomy.

During the first 5 days after birth, the most commonly prescribed opioid was oxycodone-acetaminophen (53.3%), followed by acetaminophen-codeine (20.5%), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (19.6%).

Of the 18,131 women with an early postdelivery opioid prescription, 14% (2,592) filled at least one other opioid prescription within 6-60 days – that’s 1.6% of all the women in the study.

“On a positive note, we saw the supply of opioid prescriptions was generally short at 3-7 days,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

The researchers linked tobacco use and a mental health condition (both adjusted odds ratio 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.4) to a higher risk of filling a prescription without being diagnosed with a pain-causing disorder. They also found an association between substance use disorder (not related to opioids) and a higher risk of these types of prescriptions, but only for filling a second opioid prescription in the 6-60 day period (aOR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6).

The researchers called for national guidelines regarding the use of opioids after birth.

“Several organizations have developed opioid prescribing guidelines for chronic and acute pain,” Dr. Jarlenski said. “These guidelines are necessary because the risk of opioid use disorder and subsequent overdose events is well established. Although delivery is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United States, there are no national guidelines for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery.”

The study was partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 12% of women on Medicaid filled opioid prescriptions within 5 days of delivery; just 28.2% of those patients had a pain-inducing condition.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 164,720 women enrolled in Medicaid in Pennsylvania who delivered live-born babies vaginally from 2008 to 2013.

Disclosures: The study is partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Review offers reassurance on prenatal Tdap vaccination safety

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60.

Data source: A systematic review of 21 studies.

Disclosures: Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Crusted scabies outbreak: How much prophylaxis?

, a small case series suggests.

What remains a matter of debate is how widely to use prophylaxis, according to authors of a study of two approaches published in Infection, Disease & Health.

The case series, coauthored by Dr. Nikki R. Adler and her colleagues at Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, compares and contrasts two approaches to a scabies outbreak in a tertiary care setting (Infect Dis Health. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2017.01.001).

One scenario involved an elderly woman who had been transferred from a rehabilitation facility for hip replacement surgery. Although upon admission the patient reported a pruritic truncal rash of 2 weeks’ duration, it was associated by the care team with either a cutaneous adverse drug reaction or with paraneoplastic syndrome, as she had recently been diagnosed with multiple myeloma. As a result, it wasn’t until after the patient’s emergent care needs were met 4 weeks later that she was given a formal dermatology consult, at which time several punch biopsies confirmed crusted scabies; she was treated with 5% permethrin cream for a week, weekly oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg for 1 month, as well as with topical keratolytics.

Meanwhile, because the delayed diagnosis meant the patient – who had been treated across several wards – had potentially exposed multiple health care workers and patients to Sarcoptes scabiei, the hospital immediately instituted contact precautions and implemented its outbreak protocols: communication statements, prophylactic treatment of asymptomatic staff and close patients, and treatment and quarantine for those with clinical symptoms.

The second case involved an elderly man admitted through the emergency department after presenting with fever, hypotension, and a 3-week history of a progressive, hyperkeratotic, pruritic rash on his trunk and arms. A recent heart transplant recipient, he was taking cyclosporine, mycophenolate, and prednisolone, and he had hemodialysis-dependent end-stage kidney disease. After an ED dermatologic review, he was diagnosed with S. scabiei, immediately triggering contact precautions in the ED and elsewhere. He was treated with ivermectin, 5% permethrin, and topical keratolytics. All staff thought to have been exposed to the patient were treated prophylactically with 5% permethrin single-dose therapy.

Because thickened skin flakes that slough off in crusted scabies may house hundreds of mites for longer than 48 hours, environmental cleaning was enhanced in both cases.

The latter case did not feature a prolonged outbreak thanks to early diagnosis and quick preventive action. The outbreak in the first case lasted 7 weeks and 5 days. The hospital in that case opted not to employ a mass prophylaxis strategy, instead treating 306 persons identified to have been in contact with the patient. In all, 54 symptomatic patients and health care workers were identified.

The authors cited data that, across 19 nosocomial outbreaks between 1990 and 2003, the mean number of infested patients was 18; the mean number for health care workers was 39. The attack rate, defined as the number of new cases divided by the total number of persons at risk, was 13% for patients and 35% in health care workers. The median duration of outbreak was 14.5 weeks (range, 4-52 weeks).

“The variation of outbreak size and duration in the reported literature suggests that there may be important differences in the efficacy of various infection control strategies,” Dr. Adler and her colleagues wrote, noting that while some institutions might prefer simultaneous mass prophylaxis to rapidly and efficiently control a scabies outbreak, the cost of doing so can be prohibitive, and might not be more effective than the information-centered management model used in Case 1 that relied on close tracking of all patient contacts, and use of the hospital intranet and internal memos.

This strategy does run the risk of overreaction, however: “The communication strategy may have contributed to heightened levels of concern among staff and arguably, excessive prophylaxis and/or overdiagnosis,” the authors wrote.

To help diagnose potential cases of crusted scabies quickly, Dr. Adler and her colleagues suggested clinicians consider that various dermatoses can mimic a scabies infestation and that care teams have a high index of suspicion in patients most at risk for scabies: the elderly and those who are immunocompromised, such as the heart transplant patient in Case 2, and also those with altered T-cell function.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

, a small case series suggests.

What remains a matter of debate is how widely to use prophylaxis, according to authors of a study of two approaches published in Infection, Disease & Health.

The case series, coauthored by Dr. Nikki R. Adler and her colleagues at Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, compares and contrasts two approaches to a scabies outbreak in a tertiary care setting (Infect Dis Health. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2017.01.001).

One scenario involved an elderly woman who had been transferred from a rehabilitation facility for hip replacement surgery. Although upon admission the patient reported a pruritic truncal rash of 2 weeks’ duration, it was associated by the care team with either a cutaneous adverse drug reaction or with paraneoplastic syndrome, as she had recently been diagnosed with multiple myeloma. As a result, it wasn’t until after the patient’s emergent care needs were met 4 weeks later that she was given a formal dermatology consult, at which time several punch biopsies confirmed crusted scabies; she was treated with 5% permethrin cream for a week, weekly oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg for 1 month, as well as with topical keratolytics.

Meanwhile, because the delayed diagnosis meant the patient – who had been treated across several wards – had potentially exposed multiple health care workers and patients to Sarcoptes scabiei, the hospital immediately instituted contact precautions and implemented its outbreak protocols: communication statements, prophylactic treatment of asymptomatic staff and close patients, and treatment and quarantine for those with clinical symptoms.

The second case involved an elderly man admitted through the emergency department after presenting with fever, hypotension, and a 3-week history of a progressive, hyperkeratotic, pruritic rash on his trunk and arms. A recent heart transplant recipient, he was taking cyclosporine, mycophenolate, and prednisolone, and he had hemodialysis-dependent end-stage kidney disease. After an ED dermatologic review, he was diagnosed with S. scabiei, immediately triggering contact precautions in the ED and elsewhere. He was treated with ivermectin, 5% permethrin, and topical keratolytics. All staff thought to have been exposed to the patient were treated prophylactically with 5% permethrin single-dose therapy.

Because thickened skin flakes that slough off in crusted scabies may house hundreds of mites for longer than 48 hours, environmental cleaning was enhanced in both cases.

The latter case did not feature a prolonged outbreak thanks to early diagnosis and quick preventive action. The outbreak in the first case lasted 7 weeks and 5 days. The hospital in that case opted not to employ a mass prophylaxis strategy, instead treating 306 persons identified to have been in contact with the patient. In all, 54 symptomatic patients and health care workers were identified.

The authors cited data that, across 19 nosocomial outbreaks between 1990 and 2003, the mean number of infested patients was 18; the mean number for health care workers was 39. The attack rate, defined as the number of new cases divided by the total number of persons at risk, was 13% for patients and 35% in health care workers. The median duration of outbreak was 14.5 weeks (range, 4-52 weeks).

“The variation of outbreak size and duration in the reported literature suggests that there may be important differences in the efficacy of various infection control strategies,” Dr. Adler and her colleagues wrote, noting that while some institutions might prefer simultaneous mass prophylaxis to rapidly and efficiently control a scabies outbreak, the cost of doing so can be prohibitive, and might not be more effective than the information-centered management model used in Case 1 that relied on close tracking of all patient contacts, and use of the hospital intranet and internal memos.

This strategy does run the risk of overreaction, however: “The communication strategy may have contributed to heightened levels of concern among staff and arguably, excessive prophylaxis and/or overdiagnosis,” the authors wrote.

To help diagnose potential cases of crusted scabies quickly, Dr. Adler and her colleagues suggested clinicians consider that various dermatoses can mimic a scabies infestation and that care teams have a high index of suspicion in patients most at risk for scabies: the elderly and those who are immunocompromised, such as the heart transplant patient in Case 2, and also those with altered T-cell function.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

, a small case series suggests.

What remains a matter of debate is how widely to use prophylaxis, according to authors of a study of two approaches published in Infection, Disease & Health.

The case series, coauthored by Dr. Nikki R. Adler and her colleagues at Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, compares and contrasts two approaches to a scabies outbreak in a tertiary care setting (Infect Dis Health. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2017.01.001).

One scenario involved an elderly woman who had been transferred from a rehabilitation facility for hip replacement surgery. Although upon admission the patient reported a pruritic truncal rash of 2 weeks’ duration, it was associated by the care team with either a cutaneous adverse drug reaction or with paraneoplastic syndrome, as she had recently been diagnosed with multiple myeloma. As a result, it wasn’t until after the patient’s emergent care needs were met 4 weeks later that she was given a formal dermatology consult, at which time several punch biopsies confirmed crusted scabies; she was treated with 5% permethrin cream for a week, weekly oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg for 1 month, as well as with topical keratolytics.

Meanwhile, because the delayed diagnosis meant the patient – who had been treated across several wards – had potentially exposed multiple health care workers and patients to Sarcoptes scabiei, the hospital immediately instituted contact precautions and implemented its outbreak protocols: communication statements, prophylactic treatment of asymptomatic staff and close patients, and treatment and quarantine for those with clinical symptoms.

The second case involved an elderly man admitted through the emergency department after presenting with fever, hypotension, and a 3-week history of a progressive, hyperkeratotic, pruritic rash on his trunk and arms. A recent heart transplant recipient, he was taking cyclosporine, mycophenolate, and prednisolone, and he had hemodialysis-dependent end-stage kidney disease. After an ED dermatologic review, he was diagnosed with S. scabiei, immediately triggering contact precautions in the ED and elsewhere. He was treated with ivermectin, 5% permethrin, and topical keratolytics. All staff thought to have been exposed to the patient were treated prophylactically with 5% permethrin single-dose therapy.

Because thickened skin flakes that slough off in crusted scabies may house hundreds of mites for longer than 48 hours, environmental cleaning was enhanced in both cases.

The latter case did not feature a prolonged outbreak thanks to early diagnosis and quick preventive action. The outbreak in the first case lasted 7 weeks and 5 days. The hospital in that case opted not to employ a mass prophylaxis strategy, instead treating 306 persons identified to have been in contact with the patient. In all, 54 symptomatic patients and health care workers were identified.

The authors cited data that, across 19 nosocomial outbreaks between 1990 and 2003, the mean number of infested patients was 18; the mean number for health care workers was 39. The attack rate, defined as the number of new cases divided by the total number of persons at risk, was 13% for patients and 35% in health care workers. The median duration of outbreak was 14.5 weeks (range, 4-52 weeks).

“The variation of outbreak size and duration in the reported literature suggests that there may be important differences in the efficacy of various infection control strategies,” Dr. Adler and her colleagues wrote, noting that while some institutions might prefer simultaneous mass prophylaxis to rapidly and efficiently control a scabies outbreak, the cost of doing so can be prohibitive, and might not be more effective than the information-centered management model used in Case 1 that relied on close tracking of all patient contacts, and use of the hospital intranet and internal memos.

This strategy does run the risk of overreaction, however: “The communication strategy may have contributed to heightened levels of concern among staff and arguably, excessive prophylaxis and/or overdiagnosis,” the authors wrote.

To help diagnose potential cases of crusted scabies quickly, Dr. Adler and her colleagues suggested clinicians consider that various dermatoses can mimic a scabies infestation and that care teams have a high index of suspicion in patients most at risk for scabies: the elderly and those who are immunocompromised, such as the heart transplant patient in Case 2, and also those with altered T-cell function.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM INFECTION, DISEASE, & HEALTH

Verrucous Carcinoma of the Buccal Mucosa With Extension to the Cheek

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon type of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and was first described by Ackerman1 in 1948. Rock and Fisher2 called this condition oral florid papillomatosis. The distinctive features of this tumor are low-grade malignancy, slow growth, local invasiveness, and rarely intraoral and extraoral metastasis. Extraorally, it can occur in any part of the body,3 a common site being the anogenital region. Depending on the area of occurrence, the condition also is known as Buschke-Lowenstein tumor4 or giant condyloma acuminatum (anogenital region) and carcinoma cuniculatum5 (plantar region). The exact etiology of the condition is unknown, though it is associated with human papillomavirus infection, traumatic scars, chronic infection, tobacco, and chemical carcinogens.3 We report a rare case of verrucous carcinoma originating from the buccal mucosa that subsequently spread to involve the lip and cheek as a large cauliflowerlike growth, which is an unusual presentation.

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a painless growth inside the left side of the oral cavity that had developed 5 years prior as a growth on the left buccal mucosa. The lesion gradually increased in size to involve the left oral commissure including the upper and lower lips and the skin of the left cheek; it extended beyond the nasolabial fold in a cauliflowerlike pattern. The lesion was insidious in onset and was not associated with pain, itching, or bleeding. The patient chewed tobacco for the last 40 years, with no similar lesions on any part of the body. On physical examination a warty papilliform lesion was seen on the left buccal mucosa with extension to 2 cm of the upper and lower lip on the left side including the left oral commissure and the skin of the left cheek beyond the nasolabial fold where it appeared as a cauliflowerlike growth measuring 4×5 cm in size (Figure 1). No notable lymphadenopathy was present.

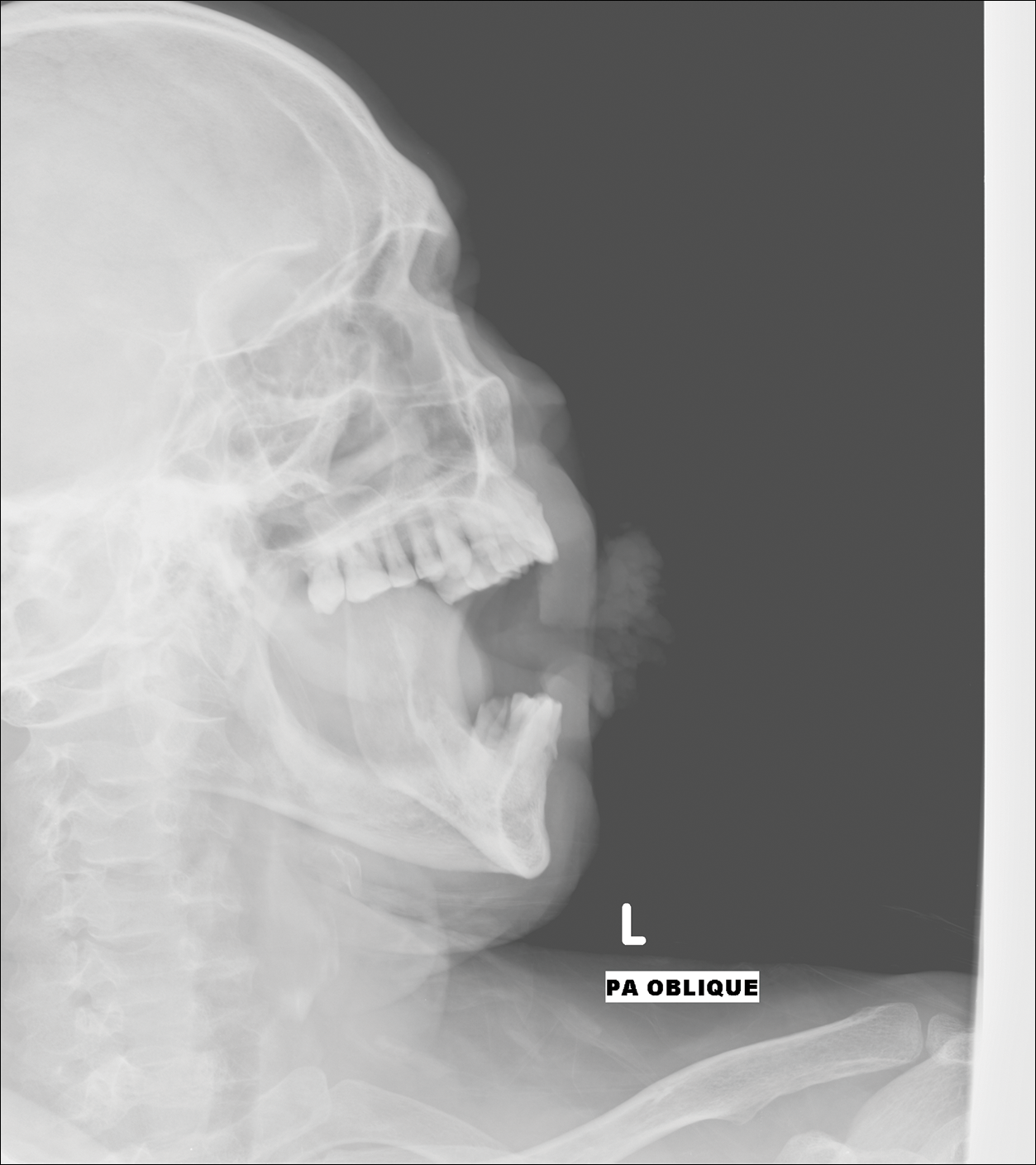

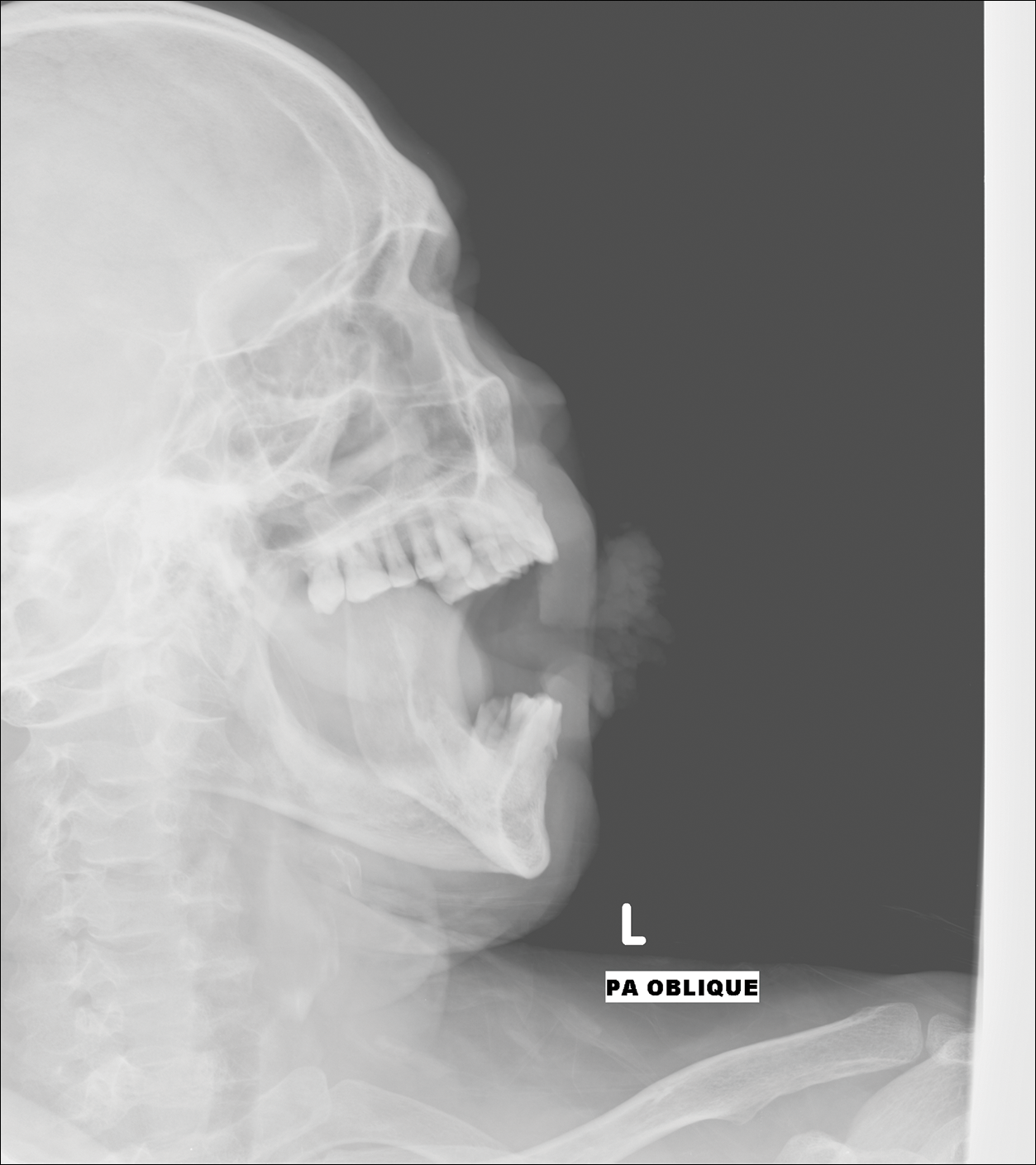

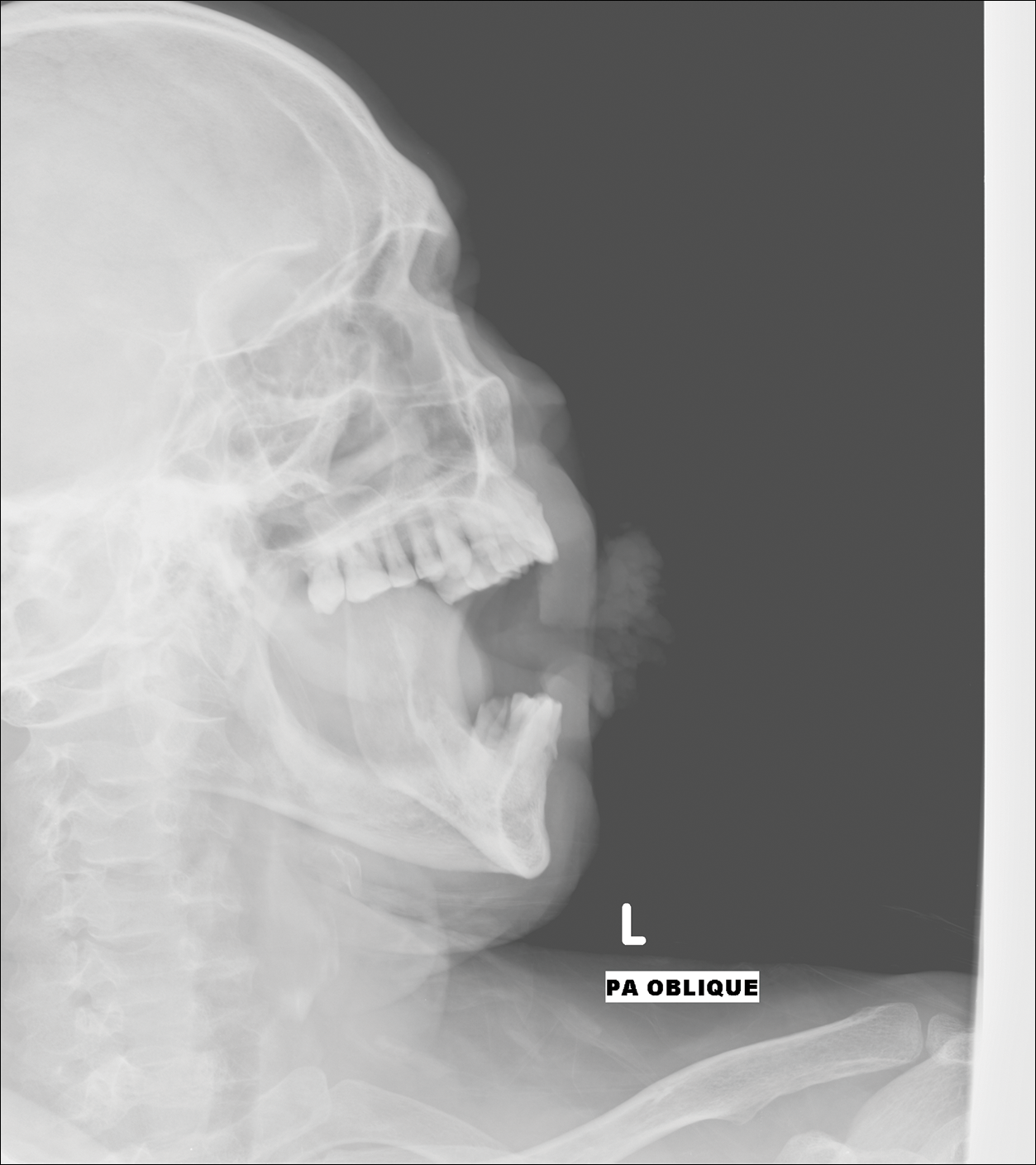

Digital radiographs of the skull (posteroanterior oblique view)(Figure 2) and mandible (left oblique view) showed a lobulated soft-tissue density lesion overlying the left half of the mandible (near the mandibular angle) with involvement of both the upper and lower lips on the left side. However, no obvious underlying bony erosion was noted.

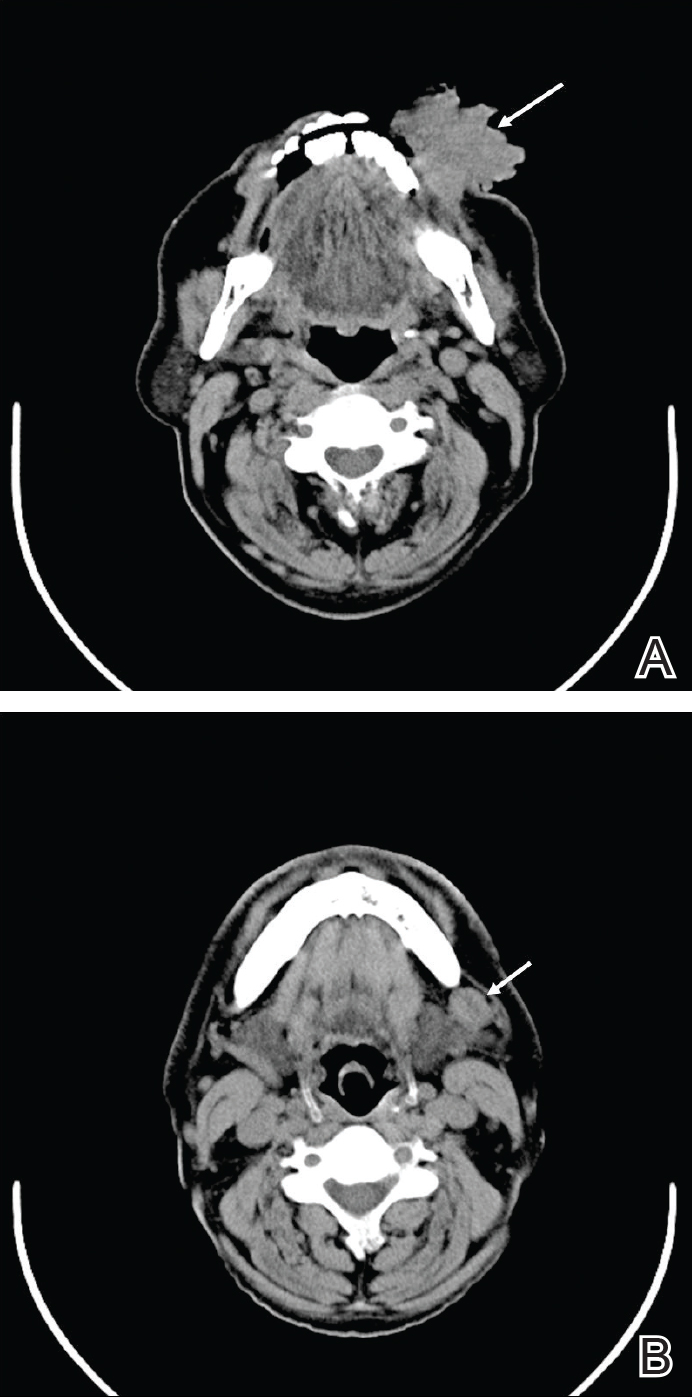

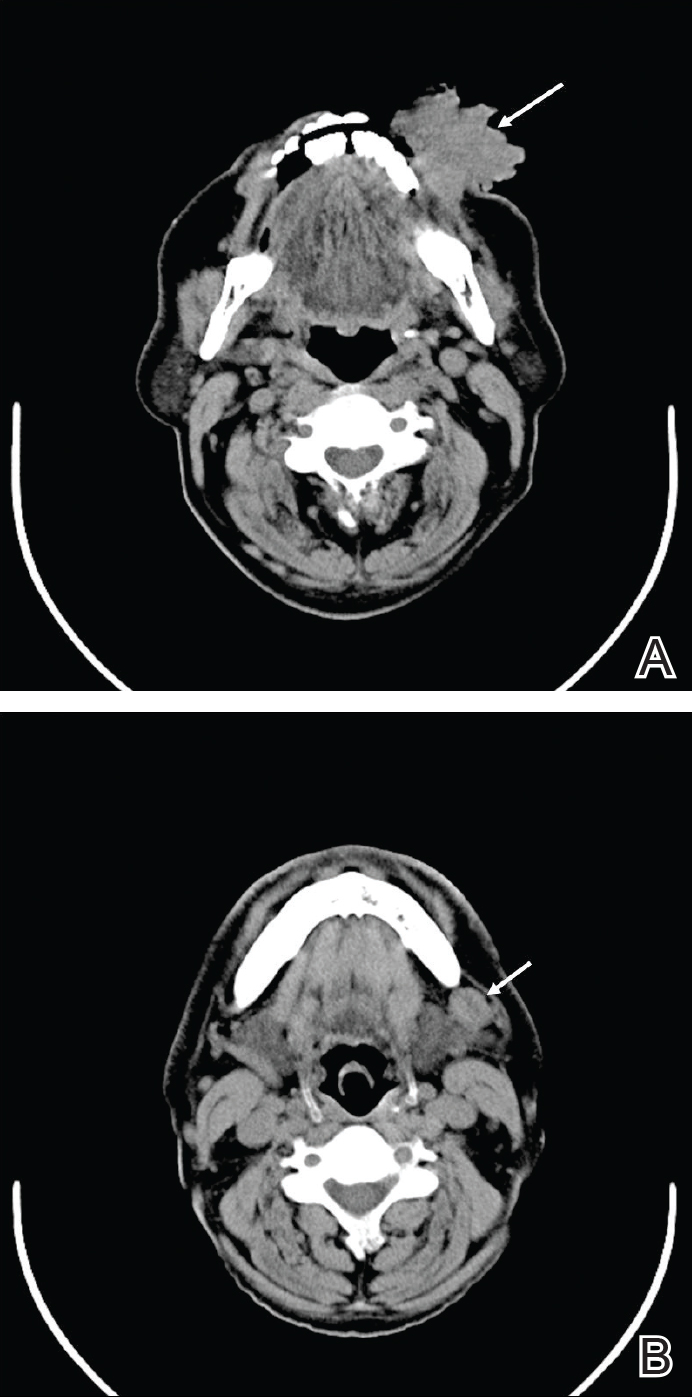

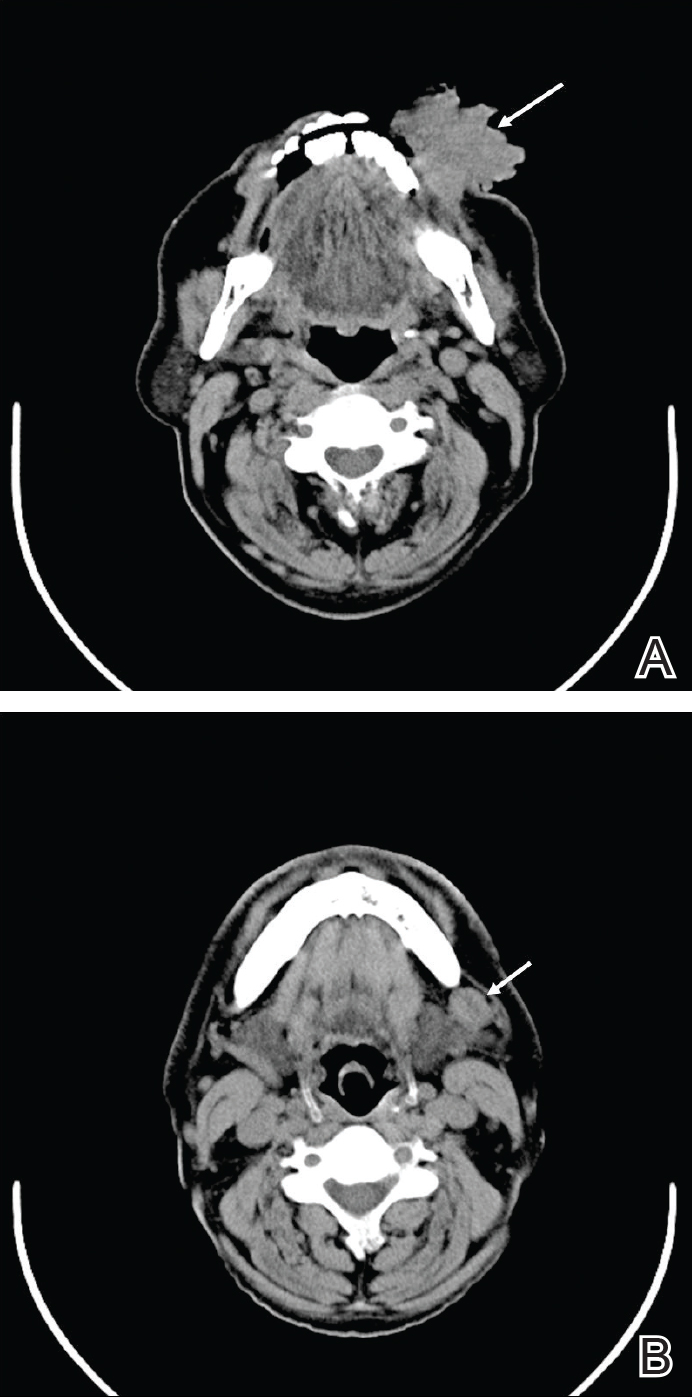

Computed tomography revealed a large soft-tissue mass (41.3×35.3 mm)(Figure 3A) involving the left buccal mucosa with extension into overlying muscle, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. Externally, the lesion was exophytic, irregular, and polypoidal with surface ulceration. Medially, the lesion involved the left oral commissure and parts of the adjoining upper and lower lips. No underlying bony erosion was seen. An enlarged lymph node measuring 20×15 mm was noted in the left upper deep cervical group in the submandibular region (Figure 3B).

Our clinical differential diagnosis included verrucous carcinoma and hypertrophic variety of lupus vulgaris. A 1×2-cm diagnostic incisional biopsy was performed from the cauliflowerlike growth and ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was done from the lymph node. Histopathology revealed a hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium with upward extension of verrucous projections, which was largely superficial to the adjacent epithelium (Figure 4A). In addition to the surface verrucous projections, there was lesion extension into the subepithelial zone in the form of round club-shaped protrusions (Figure 4B). There was no loss of polarity in these downward proliferations. No horn pearl formation was present. Fine-needle aspiration revealed reactive lymphadenitis.

The final diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma was made and the patient was referred to the oncosurgery department for further management.

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, low-grade, well-differentiated SCC of the skin or mucosa presenting with a verrucoid or cauliflowerlike appearance. It shows locally aggressive behavior and has low metastatic potential,6 a low degree of dysplasia, and a good prognosis. Because it is a tumor with predominantly horizontal growth, it tends to erode more than infiltrate. It does not present with remote metastasis.7 It has been known by several different names, usually related to anatomic sites (eg, Ackerman tumor, oral florid papillomatosis, carcinoma cuniculatum).

In the oral cavity, verrucous carcinoma constitutes 2% to 4.5% of all forms of SCC seen mainly in men older than 50 years and also is associated with a high incidence (37.7%) of a second primary tumor mainly in the oral mucosa (eg, tongue, lips, palate, salivary gland).8 Indudharan et al9 reported a case of verrucous carcinoma of the maxillary antrum in a young male patient, which also was a rare entity. Verrucous carcinoma is thought to predominantly affect elderly men. Walvekar et al10 reported a male to female ratio of 3.6 to 1 in patients with verrucous carcinoma, with a mean age of 53.9 years. According to Varshney et al,11 patients may range in age from the fourth to eighth decades of life, with a mean age of 60 years; 80% are male. The etiopathogenesis of verrucous carcinoma is related to the following carcinogens: biologic (eg, human papillomavirus), chemical (eg, smoking), and physical (eg, constant trauma).

Verrucous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of slow-growing, locally spreading tumors. Oral tumors, especially in tobacco chewers, should raise suspicion of verrucous carcinoma, which will enable prompt management of the tumor.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Rock JA, Fisher ER. Florid papillomatosis of the oral cavity and larynx. Arch Otolaryngol. 1960;72:593-598.

- Pattee SF, Bordeaux J, Mahalingam M, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:506-507.

- Buschke A, Lowenstein L. Uber carcinomahnliche condylomata acuminata despenis. Klin Wochenschr. 1925;4:1726-1728.

- Aird I, Johnson HD, Lennox B, et al. Epithelioma cuniculatum: a variety of squamous carcinoma peculiar to the foot. Br J Surg. 1954;42:245-250.

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-21.

- Zanini M, Wulkan C, Paschoal FM, et al. Verrucous carcinoma: a clinical histopathologic variant of squamous cell carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2004;79:619-621.

- Kalsotra P, Manhas M, Sood R. Verrucous carcinoma of hard palate. JK Science. 2000;2:52-54.

- Indudharan R, Das PK, Thida T. Verrucous carcinoma of maxillary antrum. Singapore Med J. 1996;37:559-561.

- Walvekar RR, Chaukar DA, Deshpande MS, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity: a clinical and pathological study of 101 cases. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:47-51.

- Varshney S, Singh J, Saxena RK, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of larynx. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;56:54-56.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon type of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and was first described by Ackerman1 in 1948. Rock and Fisher2 called this condition oral florid papillomatosis. The distinctive features of this tumor are low-grade malignancy, slow growth, local invasiveness, and rarely intraoral and extraoral metastasis. Extraorally, it can occur in any part of the body,3 a common site being the anogenital region. Depending on the area of occurrence, the condition also is known as Buschke-Lowenstein tumor4 or giant condyloma acuminatum (anogenital region) and carcinoma cuniculatum5 (plantar region). The exact etiology of the condition is unknown, though it is associated with human papillomavirus infection, traumatic scars, chronic infection, tobacco, and chemical carcinogens.3 We report a rare case of verrucous carcinoma originating from the buccal mucosa that subsequently spread to involve the lip and cheek as a large cauliflowerlike growth, which is an unusual presentation.

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a painless growth inside the left side of the oral cavity that had developed 5 years prior as a growth on the left buccal mucosa. The lesion gradually increased in size to involve the left oral commissure including the upper and lower lips and the skin of the left cheek; it extended beyond the nasolabial fold in a cauliflowerlike pattern. The lesion was insidious in onset and was not associated with pain, itching, or bleeding. The patient chewed tobacco for the last 40 years, with no similar lesions on any part of the body. On physical examination a warty papilliform lesion was seen on the left buccal mucosa with extension to 2 cm of the upper and lower lip on the left side including the left oral commissure and the skin of the left cheek beyond the nasolabial fold where it appeared as a cauliflowerlike growth measuring 4×5 cm in size (Figure 1). No notable lymphadenopathy was present.

Digital radiographs of the skull (posteroanterior oblique view)(Figure 2) and mandible (left oblique view) showed a lobulated soft-tissue density lesion overlying the left half of the mandible (near the mandibular angle) with involvement of both the upper and lower lips on the left side. However, no obvious underlying bony erosion was noted.

Computed tomography revealed a large soft-tissue mass (41.3×35.3 mm)(Figure 3A) involving the left buccal mucosa with extension into overlying muscle, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. Externally, the lesion was exophytic, irregular, and polypoidal with surface ulceration. Medially, the lesion involved the left oral commissure and parts of the adjoining upper and lower lips. No underlying bony erosion was seen. An enlarged lymph node measuring 20×15 mm was noted in the left upper deep cervical group in the submandibular region (Figure 3B).

Our clinical differential diagnosis included verrucous carcinoma and hypertrophic variety of lupus vulgaris. A 1×2-cm diagnostic incisional biopsy was performed from the cauliflowerlike growth and ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was done from the lymph node. Histopathology revealed a hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium with upward extension of verrucous projections, which was largely superficial to the adjacent epithelium (Figure 4A). In addition to the surface verrucous projections, there was lesion extension into the subepithelial zone in the form of round club-shaped protrusions (Figure 4B). There was no loss of polarity in these downward proliferations. No horn pearl formation was present. Fine-needle aspiration revealed reactive lymphadenitis.

The final diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma was made and the patient was referred to the oncosurgery department for further management.

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, low-grade, well-differentiated SCC of the skin or mucosa presenting with a verrucoid or cauliflowerlike appearance. It shows locally aggressive behavior and has low metastatic potential,6 a low degree of dysplasia, and a good prognosis. Because it is a tumor with predominantly horizontal growth, it tends to erode more than infiltrate. It does not present with remote metastasis.7 It has been known by several different names, usually related to anatomic sites (eg, Ackerman tumor, oral florid papillomatosis, carcinoma cuniculatum).

In the oral cavity, verrucous carcinoma constitutes 2% to 4.5% of all forms of SCC seen mainly in men older than 50 years and also is associated with a high incidence (37.7%) of a second primary tumor mainly in the oral mucosa (eg, tongue, lips, palate, salivary gland).8 Indudharan et al9 reported a case of verrucous carcinoma of the maxillary antrum in a young male patient, which also was a rare entity. Verrucous carcinoma is thought to predominantly affect elderly men. Walvekar et al10 reported a male to female ratio of 3.6 to 1 in patients with verrucous carcinoma, with a mean age of 53.9 years. According to Varshney et al,11 patients may range in age from the fourth to eighth decades of life, with a mean age of 60 years; 80% are male. The etiopathogenesis of verrucous carcinoma is related to the following carcinogens: biologic (eg, human papillomavirus), chemical (eg, smoking), and physical (eg, constant trauma).

Verrucous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of slow-growing, locally spreading tumors. Oral tumors, especially in tobacco chewers, should raise suspicion of verrucous carcinoma, which will enable prompt management of the tumor.

To the Editor: