User login

Nondirected testing for inpatients with severe liver injury

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old woman with ischemic cardiomyopathy was admitted with abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and nausea, which had left her unable to keep food and liquids down for 2 days. She had been taking diuretics and had a remote history of intravenous drug use. On admission, she was afebrile and had blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg and a heart rate of 100 bpm. Her extremities were cool and clammy. Blood test results showed an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 1510 IU/L and an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 1643 IU/L. The patient’s clinician did not know her baseline ALT and AST levels and thought the best approach was to identify the cause of the transaminase elevation.

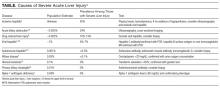

Severe acute liver injury (liver enzymes, >10 × upper limit of normal [ULN], usually 40 IU/L) is a common presentation among hospitalized patients. Between 1997 and 2015, 1.5% of patients admitted to our hospital had severe liver injury. In another large cohort of hospitalized patients,1 0.6% had an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L (~20 × ULN). A precise diagnosis is often needed to direct appropriate therapy, and serologic tests are available for many conditions, both common and rare (Table). Given the relative ease of bundled blood testing, nondirected testing has emerged as a popular, if reflexive, strategy.2-5 In this approach, clinicians evaluate each patient for the set of testable diseases all at once—in contrast to taking a directed, stepwise testing approach guided by the patient’s history.

Use of nondirected testing is common in patients with severe acute liver injury. Of the 5795 such patients treated at our hospital between 2000 and 2015, within the same day of service 53% were tested for hepatitis C virus antibody, 38% for hemochromatosis (ferritin test), 28% for autoimmune hepatitis (antinuclear antibody test), and 15% for primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibody test) by our clinical laboratory. Of the 5023 patients who had send-out tests performed for Wilson disease (ceruloplasmin), 81% were queried for hepatitis B virus infection, 76% for hepatitis C virus infection, 75% for autoimmune hepatitis, and 73.1% for hemochromatosis.2 Similar trends were found for patients with severe liver injury tested for α1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency.3 In sum, these data showed that each patient with severe liver injury was tested out of concern about diseases with markedly different epidemiology and clinical presentations (Table).

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK NONDIRECTED TESTING IS HELPFUL

Use of nondirected testing may reflect perceived urgency, convenience, and thoroughness.2-6 Alternatively, it may simply involve following a consultant’s recommendations.4 As severe acute liver injury is often associated with tremendous morbidity, clinicians seeking answers may perceive directed, stepwise testing as inappropriately slow given the urgency of the presentation; they may think that nondirected testing can reduce hospital length of stay.

WHY NONDIRECTED TESTING IS NOT HELPFUL

Nondirected testing is a problem for at least 4 reasons: limited benefit of reflexive testing for rare diseases, no meaningful impact on outcomes, false positives, and financial cost.

First, immediately testing for rare causes of liver disease is unlikely to benefit patients with severe liver injury. The underlying etiologies of severe liver injury are relatively well circumscribed (Table). Overall, 42% of patients with severe liver injury and 57% of those with an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L have ischemic hepatitis.7 Accounting for a significant percentage of severe liver injury cases are acute biliary obstruction (24%), drug-induced injury (10%-13%), and viral hepatitis (4%-7%).1,8 Of the small subset of patients with severe liver injury that progresses to acute liver failure (ALF; encephalopathy, coagulopathy), 0.5% have autoimmune hepatitis and 0.1% have Wilson disease.9 Furthermore, many patients are tested for AAT deficiency, hemochromatosis, and primary biliary cholangitis, but these are never causes of severe acute liver injury (Table).

Second, diagnosing a rarer cause of acute liver injury modestly earlier has no meaningful impact on outcome. Work-up for more common etiologies can usually be completed within 2 or 3 days. This is true even for patients with ALF. Specific therapies generally are lacking for ALF, save for use of N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose and antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus infection.9,10 Furthermore, although effective therapies are available for both autoimmune hepatitis and Wilson disease, the potential benefit stems from altering the longer term course of disease. Initial management, even for these rare conditions, is no different from that for other etiologies. Conversely, acute liver injury caused by ischemic hepatitis, biliary disease, or drug-induced liver injury requires swift corrective action. Even if normotensive, patients with ischemic hepatitis are often in cardiogenic shock and benefit from careful monitoring and critical care.7 Patients with acute biliary obstruction may need therapeutic endoscopy. Last, patients with drug-induced liver injury benefit from immediate discontinuation of the offending drug.

Third, in the testing of patients with low pretest probabilities, false positives are common. For example, at our institution and at an institution in Austria, severe liver injury patients with a low ceruloplasmin level have a 95.1% to 98.1% chance of a false-positive result (they have a low ceruloplasmin level but do not have Wilson disease).3,4 Furthermore, 91% of positive tests are never confirmed,3 indicating either that clinicians never valued the initial test or that other diagnoses were much more likely. Even worse, as was the case in 65% of patients with low AAT levels,2,3 genetic diagnoses were based on unconfirmed, potentially false-positive serologic tests.

Fourth, although the financial cost for each individual test is small, at the population level the cost of nondirected testing is significant. For example, although each reflects testing for conditions that do not cause acute liver injury, the costs of ferritin, AAT, and antimitochondrial antibody tests are $13, $16, and $37, respectively (Medicare/Medicaid reimbursements in 2016 $US).11 About 1.5% of admitted patients are found to have severe liver injury. If this proportion holds true for the roughly 40 million discharges from US hospitals each year, then there would be an annual cost of about $40 million if all 3 tests were performed for each patient with severe liver injury. In addition, although nondirected testing may seem clinically expedient, there are no data suggesting it reduces length of stay. In fact, ceruloplasmin, AAT, and many other tests are sent to external laboratories and are unlikely to be returned before discharge. If clinicians delay discharge for results, then nondirected testing would increase rather than decrease length of stay.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

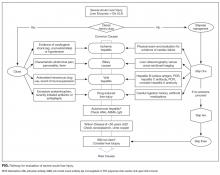

In this era of increasing cost-consciousness, nondirected testing has escaped relatively unscathed. Indeed, nondirected testing is prevalent, yet has pitfalls similar to those of serologic testing (eg, vasculitis or arthritis,6 acute renal injury, infectious disease12). The alternative is deliberate, empirical, patient-centered testing that is attentive to the patient’s presentation and the harms of false positives. The idea is to select tests for each patient with acute liver injury according to presentation and the most likely corresponding diagnoses (Table, Figure).

The “one-stop shopping” in providers’ electronic order entry systems makes it too easy to over-order tests. Fortunately, these systems’ simple and effective decision supports can force pauses in the ordering process, create barriers to waste, and provide education about test characteristics and costs.4,5,13 Our medical center’s volume of ceruloplasmin orders decreased by 80% after a change was made to its ordering system; the ordering of a ceruloplasmin test is now interrupted by a pop-up screen that displays test characteristics and an option to continue or cancel the order.4,5 Hospitals should consider implementing clinical decision supports in this area. Successful interventions provide electronic rather than paper-based support as part of the clinical workflow, during the ordering process, and recommendations rather than assessments.13

RECOMMENDATIONS

- For each patient with severe acute liver injury, select tests on the basis of the presentation (Figure). Testing for rare diseases should be performed only after common diseases have been excluded.

- Avoid testing for hemochromatosis (iron indices, genetic tests), AAT deficiency (AAT levels or phenotypes), and primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibodies) in patients with severe acute liver injury.

- Consider implementing decision supports that can curb nondirected testing in areas in which it is common.

CONCLUSION

Nondirected testing is associated with false positives and increased costs in the evaluation and management of severe acute liver injury. The alternative is deliberate, epidemiologically and clinically driven directed testing. Electronic ordering system decision supports can be useful in curtailing nondirected testing.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter.

1. Johnson RD, O’Connor ML, Kerr RM. Extreme serum elevations of aspartate aminotransferase. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(8):1244-1245. PubMed

2. Tapper EB, Patwardhan VR, Curry M. Low yield and utilization of confirmatory testing in a cohort of patients with liver disease assessed for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(6):1589-1594. PubMed

3. Tapper EB, Rahni DO, Arnaout R, Lai M. The overuse of serum ceruloplasmin measurement. Am J Med. 2013;126(10):926.e1-e5. PubMed

4. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. Understanding and reducing ceruloplasmin overuse with a decision support intervention for liver disease evaluation. Am J Med. 2016;129(1):115.e17-e22. PubMed

5. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. A decision support tool to reduce overtesting for ceruloplasmin and improve adherence with clinical guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1561-1562. PubMed

6. Lichtenstein MJ, Pincus T. How useful are combinations of blood tests in “rheumatic panels” in diagnosis of rheumatic diseases? J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):435-442. PubMed

7. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321. PubMed

8. Whitehead MW, Hawkes ND, Hainsworth I, Kingham JG. A prospective study of the causes of notably raised aspartate aminotransferase of liver origin. Gut. 1999;45(1):129-133. PubMed

9. Fontana RJ. Acute liver failure including acetaminophen overdose. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(4):761-794. PubMed

10. Lee WM, Larson AM, Stravitz RT. AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases website. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/guideline_documents/alfenhanced.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed January 26, 2017.

11. Green RM, Flamm S. AGA technical review on the evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(4):1367-1384. PubMed

12. Aesif SW, Parenti DM, Lesky L, Keiser JF. A cost-effective interdisciplinary approach to microbiologic send-out test use. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(2):194-198. PubMed

13. Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765. PubMed

14. Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6(3):635-647. PubMed

15. Bacon BR, Adams PC, Kowdley KV, Powell LW, Tavill AS; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of hemochromatosis: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):328-343. PubMed

16. Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56(5):1181-1188. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old woman with ischemic cardiomyopathy was admitted with abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and nausea, which had left her unable to keep food and liquids down for 2 days. She had been taking diuretics and had a remote history of intravenous drug use. On admission, she was afebrile and had blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg and a heart rate of 100 bpm. Her extremities were cool and clammy. Blood test results showed an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 1510 IU/L and an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 1643 IU/L. The patient’s clinician did not know her baseline ALT and AST levels and thought the best approach was to identify the cause of the transaminase elevation.

Severe acute liver injury (liver enzymes, >10 × upper limit of normal [ULN], usually 40 IU/L) is a common presentation among hospitalized patients. Between 1997 and 2015, 1.5% of patients admitted to our hospital had severe liver injury. In another large cohort of hospitalized patients,1 0.6% had an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L (~20 × ULN). A precise diagnosis is often needed to direct appropriate therapy, and serologic tests are available for many conditions, both common and rare (Table). Given the relative ease of bundled blood testing, nondirected testing has emerged as a popular, if reflexive, strategy.2-5 In this approach, clinicians evaluate each patient for the set of testable diseases all at once—in contrast to taking a directed, stepwise testing approach guided by the patient’s history.

Use of nondirected testing is common in patients with severe acute liver injury. Of the 5795 such patients treated at our hospital between 2000 and 2015, within the same day of service 53% were tested for hepatitis C virus antibody, 38% for hemochromatosis (ferritin test), 28% for autoimmune hepatitis (antinuclear antibody test), and 15% for primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibody test) by our clinical laboratory. Of the 5023 patients who had send-out tests performed for Wilson disease (ceruloplasmin), 81% were queried for hepatitis B virus infection, 76% for hepatitis C virus infection, 75% for autoimmune hepatitis, and 73.1% for hemochromatosis.2 Similar trends were found for patients with severe liver injury tested for α1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency.3 In sum, these data showed that each patient with severe liver injury was tested out of concern about diseases with markedly different epidemiology and clinical presentations (Table).

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK NONDIRECTED TESTING IS HELPFUL

Use of nondirected testing may reflect perceived urgency, convenience, and thoroughness.2-6 Alternatively, it may simply involve following a consultant’s recommendations.4 As severe acute liver injury is often associated with tremendous morbidity, clinicians seeking answers may perceive directed, stepwise testing as inappropriately slow given the urgency of the presentation; they may think that nondirected testing can reduce hospital length of stay.

WHY NONDIRECTED TESTING IS NOT HELPFUL

Nondirected testing is a problem for at least 4 reasons: limited benefit of reflexive testing for rare diseases, no meaningful impact on outcomes, false positives, and financial cost.

First, immediately testing for rare causes of liver disease is unlikely to benefit patients with severe liver injury. The underlying etiologies of severe liver injury are relatively well circumscribed (Table). Overall, 42% of patients with severe liver injury and 57% of those with an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L have ischemic hepatitis.7 Accounting for a significant percentage of severe liver injury cases are acute biliary obstruction (24%), drug-induced injury (10%-13%), and viral hepatitis (4%-7%).1,8 Of the small subset of patients with severe liver injury that progresses to acute liver failure (ALF; encephalopathy, coagulopathy), 0.5% have autoimmune hepatitis and 0.1% have Wilson disease.9 Furthermore, many patients are tested for AAT deficiency, hemochromatosis, and primary biliary cholangitis, but these are never causes of severe acute liver injury (Table).

Second, diagnosing a rarer cause of acute liver injury modestly earlier has no meaningful impact on outcome. Work-up for more common etiologies can usually be completed within 2 or 3 days. This is true even for patients with ALF. Specific therapies generally are lacking for ALF, save for use of N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose and antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus infection.9,10 Furthermore, although effective therapies are available for both autoimmune hepatitis and Wilson disease, the potential benefit stems from altering the longer term course of disease. Initial management, even for these rare conditions, is no different from that for other etiologies. Conversely, acute liver injury caused by ischemic hepatitis, biliary disease, or drug-induced liver injury requires swift corrective action. Even if normotensive, patients with ischemic hepatitis are often in cardiogenic shock and benefit from careful monitoring and critical care.7 Patients with acute biliary obstruction may need therapeutic endoscopy. Last, patients with drug-induced liver injury benefit from immediate discontinuation of the offending drug.

Third, in the testing of patients with low pretest probabilities, false positives are common. For example, at our institution and at an institution in Austria, severe liver injury patients with a low ceruloplasmin level have a 95.1% to 98.1% chance of a false-positive result (they have a low ceruloplasmin level but do not have Wilson disease).3,4 Furthermore, 91% of positive tests are never confirmed,3 indicating either that clinicians never valued the initial test or that other diagnoses were much more likely. Even worse, as was the case in 65% of patients with low AAT levels,2,3 genetic diagnoses were based on unconfirmed, potentially false-positive serologic tests.

Fourth, although the financial cost for each individual test is small, at the population level the cost of nondirected testing is significant. For example, although each reflects testing for conditions that do not cause acute liver injury, the costs of ferritin, AAT, and antimitochondrial antibody tests are $13, $16, and $37, respectively (Medicare/Medicaid reimbursements in 2016 $US).11 About 1.5% of admitted patients are found to have severe liver injury. If this proportion holds true for the roughly 40 million discharges from US hospitals each year, then there would be an annual cost of about $40 million if all 3 tests were performed for each patient with severe liver injury. In addition, although nondirected testing may seem clinically expedient, there are no data suggesting it reduces length of stay. In fact, ceruloplasmin, AAT, and many other tests are sent to external laboratories and are unlikely to be returned before discharge. If clinicians delay discharge for results, then nondirected testing would increase rather than decrease length of stay.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

In this era of increasing cost-consciousness, nondirected testing has escaped relatively unscathed. Indeed, nondirected testing is prevalent, yet has pitfalls similar to those of serologic testing (eg, vasculitis or arthritis,6 acute renal injury, infectious disease12). The alternative is deliberate, empirical, patient-centered testing that is attentive to the patient’s presentation and the harms of false positives. The idea is to select tests for each patient with acute liver injury according to presentation and the most likely corresponding diagnoses (Table, Figure).

The “one-stop shopping” in providers’ electronic order entry systems makes it too easy to over-order tests. Fortunately, these systems’ simple and effective decision supports can force pauses in the ordering process, create barriers to waste, and provide education about test characteristics and costs.4,5,13 Our medical center’s volume of ceruloplasmin orders decreased by 80% after a change was made to its ordering system; the ordering of a ceruloplasmin test is now interrupted by a pop-up screen that displays test characteristics and an option to continue or cancel the order.4,5 Hospitals should consider implementing clinical decision supports in this area. Successful interventions provide electronic rather than paper-based support as part of the clinical workflow, during the ordering process, and recommendations rather than assessments.13

RECOMMENDATIONS

- For each patient with severe acute liver injury, select tests on the basis of the presentation (Figure). Testing for rare diseases should be performed only after common diseases have been excluded.

- Avoid testing for hemochromatosis (iron indices, genetic tests), AAT deficiency (AAT levels or phenotypes), and primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibodies) in patients with severe acute liver injury.

- Consider implementing decision supports that can curb nondirected testing in areas in which it is common.

CONCLUSION

Nondirected testing is associated with false positives and increased costs in the evaluation and management of severe acute liver injury. The alternative is deliberate, epidemiologically and clinically driven directed testing. Electronic ordering system decision supports can be useful in curtailing nondirected testing.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter.

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old woman with ischemic cardiomyopathy was admitted with abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and nausea, which had left her unable to keep food and liquids down for 2 days. She had been taking diuretics and had a remote history of intravenous drug use. On admission, she was afebrile and had blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg and a heart rate of 100 bpm. Her extremities were cool and clammy. Blood test results showed an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 1510 IU/L and an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 1643 IU/L. The patient’s clinician did not know her baseline ALT and AST levels and thought the best approach was to identify the cause of the transaminase elevation.

Severe acute liver injury (liver enzymes, >10 × upper limit of normal [ULN], usually 40 IU/L) is a common presentation among hospitalized patients. Between 1997 and 2015, 1.5% of patients admitted to our hospital had severe liver injury. In another large cohort of hospitalized patients,1 0.6% had an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L (~20 × ULN). A precise diagnosis is often needed to direct appropriate therapy, and serologic tests are available for many conditions, both common and rare (Table). Given the relative ease of bundled blood testing, nondirected testing has emerged as a popular, if reflexive, strategy.2-5 In this approach, clinicians evaluate each patient for the set of testable diseases all at once—in contrast to taking a directed, stepwise testing approach guided by the patient’s history.

Use of nondirected testing is common in patients with severe acute liver injury. Of the 5795 such patients treated at our hospital between 2000 and 2015, within the same day of service 53% were tested for hepatitis C virus antibody, 38% for hemochromatosis (ferritin test), 28% for autoimmune hepatitis (antinuclear antibody test), and 15% for primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibody test) by our clinical laboratory. Of the 5023 patients who had send-out tests performed for Wilson disease (ceruloplasmin), 81% were queried for hepatitis B virus infection, 76% for hepatitis C virus infection, 75% for autoimmune hepatitis, and 73.1% for hemochromatosis.2 Similar trends were found for patients with severe liver injury tested for α1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency.3 In sum, these data showed that each patient with severe liver injury was tested out of concern about diseases with markedly different epidemiology and clinical presentations (Table).

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK NONDIRECTED TESTING IS HELPFUL

Use of nondirected testing may reflect perceived urgency, convenience, and thoroughness.2-6 Alternatively, it may simply involve following a consultant’s recommendations.4 As severe acute liver injury is often associated with tremendous morbidity, clinicians seeking answers may perceive directed, stepwise testing as inappropriately slow given the urgency of the presentation; they may think that nondirected testing can reduce hospital length of stay.

WHY NONDIRECTED TESTING IS NOT HELPFUL

Nondirected testing is a problem for at least 4 reasons: limited benefit of reflexive testing for rare diseases, no meaningful impact on outcomes, false positives, and financial cost.

First, immediately testing for rare causes of liver disease is unlikely to benefit patients with severe liver injury. The underlying etiologies of severe liver injury are relatively well circumscribed (Table). Overall, 42% of patients with severe liver injury and 57% of those with an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L have ischemic hepatitis.7 Accounting for a significant percentage of severe liver injury cases are acute biliary obstruction (24%), drug-induced injury (10%-13%), and viral hepatitis (4%-7%).1,8 Of the small subset of patients with severe liver injury that progresses to acute liver failure (ALF; encephalopathy, coagulopathy), 0.5% have autoimmune hepatitis and 0.1% have Wilson disease.9 Furthermore, many patients are tested for AAT deficiency, hemochromatosis, and primary biliary cholangitis, but these are never causes of severe acute liver injury (Table).

Second, diagnosing a rarer cause of acute liver injury modestly earlier has no meaningful impact on outcome. Work-up for more common etiologies can usually be completed within 2 or 3 days. This is true even for patients with ALF. Specific therapies generally are lacking for ALF, save for use of N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose and antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus infection.9,10 Furthermore, although effective therapies are available for both autoimmune hepatitis and Wilson disease, the potential benefit stems from altering the longer term course of disease. Initial management, even for these rare conditions, is no different from that for other etiologies. Conversely, acute liver injury caused by ischemic hepatitis, biliary disease, or drug-induced liver injury requires swift corrective action. Even if normotensive, patients with ischemic hepatitis are often in cardiogenic shock and benefit from careful monitoring and critical care.7 Patients with acute biliary obstruction may need therapeutic endoscopy. Last, patients with drug-induced liver injury benefit from immediate discontinuation of the offending drug.

Third, in the testing of patients with low pretest probabilities, false positives are common. For example, at our institution and at an institution in Austria, severe liver injury patients with a low ceruloplasmin level have a 95.1% to 98.1% chance of a false-positive result (they have a low ceruloplasmin level but do not have Wilson disease).3,4 Furthermore, 91% of positive tests are never confirmed,3 indicating either that clinicians never valued the initial test or that other diagnoses were much more likely. Even worse, as was the case in 65% of patients with low AAT levels,2,3 genetic diagnoses were based on unconfirmed, potentially false-positive serologic tests.

Fourth, although the financial cost for each individual test is small, at the population level the cost of nondirected testing is significant. For example, although each reflects testing for conditions that do not cause acute liver injury, the costs of ferritin, AAT, and antimitochondrial antibody tests are $13, $16, and $37, respectively (Medicare/Medicaid reimbursements in 2016 $US).11 About 1.5% of admitted patients are found to have severe liver injury. If this proportion holds true for the roughly 40 million discharges from US hospitals each year, then there would be an annual cost of about $40 million if all 3 tests were performed for each patient with severe liver injury. In addition, although nondirected testing may seem clinically expedient, there are no data suggesting it reduces length of stay. In fact, ceruloplasmin, AAT, and many other tests are sent to external laboratories and are unlikely to be returned before discharge. If clinicians delay discharge for results, then nondirected testing would increase rather than decrease length of stay.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

In this era of increasing cost-consciousness, nondirected testing has escaped relatively unscathed. Indeed, nondirected testing is prevalent, yet has pitfalls similar to those of serologic testing (eg, vasculitis or arthritis,6 acute renal injury, infectious disease12). The alternative is deliberate, empirical, patient-centered testing that is attentive to the patient’s presentation and the harms of false positives. The idea is to select tests for each patient with acute liver injury according to presentation and the most likely corresponding diagnoses (Table, Figure).

The “one-stop shopping” in providers’ electronic order entry systems makes it too easy to over-order tests. Fortunately, these systems’ simple and effective decision supports can force pauses in the ordering process, create barriers to waste, and provide education about test characteristics and costs.4,5,13 Our medical center’s volume of ceruloplasmin orders decreased by 80% after a change was made to its ordering system; the ordering of a ceruloplasmin test is now interrupted by a pop-up screen that displays test characteristics and an option to continue or cancel the order.4,5 Hospitals should consider implementing clinical decision supports in this area. Successful interventions provide electronic rather than paper-based support as part of the clinical workflow, during the ordering process, and recommendations rather than assessments.13

RECOMMENDATIONS

- For each patient with severe acute liver injury, select tests on the basis of the presentation (Figure). Testing for rare diseases should be performed only after common diseases have been excluded.

- Avoid testing for hemochromatosis (iron indices, genetic tests), AAT deficiency (AAT levels or phenotypes), and primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibodies) in patients with severe acute liver injury.

- Consider implementing decision supports that can curb nondirected testing in areas in which it is common.

CONCLUSION

Nondirected testing is associated with false positives and increased costs in the evaluation and management of severe acute liver injury. The alternative is deliberate, epidemiologically and clinically driven directed testing. Electronic ordering system decision supports can be useful in curtailing nondirected testing.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter.

1. Johnson RD, O’Connor ML, Kerr RM. Extreme serum elevations of aspartate aminotransferase. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(8):1244-1245. PubMed

2. Tapper EB, Patwardhan VR, Curry M. Low yield and utilization of confirmatory testing in a cohort of patients with liver disease assessed for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(6):1589-1594. PubMed

3. Tapper EB, Rahni DO, Arnaout R, Lai M. The overuse of serum ceruloplasmin measurement. Am J Med. 2013;126(10):926.e1-e5. PubMed

4. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. Understanding and reducing ceruloplasmin overuse with a decision support intervention for liver disease evaluation. Am J Med. 2016;129(1):115.e17-e22. PubMed

5. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. A decision support tool to reduce overtesting for ceruloplasmin and improve adherence with clinical guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1561-1562. PubMed

6. Lichtenstein MJ, Pincus T. How useful are combinations of blood tests in “rheumatic panels” in diagnosis of rheumatic diseases? J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):435-442. PubMed

7. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321. PubMed

8. Whitehead MW, Hawkes ND, Hainsworth I, Kingham JG. A prospective study of the causes of notably raised aspartate aminotransferase of liver origin. Gut. 1999;45(1):129-133. PubMed

9. Fontana RJ. Acute liver failure including acetaminophen overdose. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(4):761-794. PubMed

10. Lee WM, Larson AM, Stravitz RT. AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases website. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/guideline_documents/alfenhanced.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed January 26, 2017.

11. Green RM, Flamm S. AGA technical review on the evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(4):1367-1384. PubMed

12. Aesif SW, Parenti DM, Lesky L, Keiser JF. A cost-effective interdisciplinary approach to microbiologic send-out test use. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(2):194-198. PubMed

13. Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765. PubMed

14. Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6(3):635-647. PubMed

15. Bacon BR, Adams PC, Kowdley KV, Powell LW, Tavill AS; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of hemochromatosis: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):328-343. PubMed

16. Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56(5):1181-1188. PubMed

1. Johnson RD, O’Connor ML, Kerr RM. Extreme serum elevations of aspartate aminotransferase. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(8):1244-1245. PubMed

2. Tapper EB, Patwardhan VR, Curry M. Low yield and utilization of confirmatory testing in a cohort of patients with liver disease assessed for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(6):1589-1594. PubMed

3. Tapper EB, Rahni DO, Arnaout R, Lai M. The overuse of serum ceruloplasmin measurement. Am J Med. 2013;126(10):926.e1-e5. PubMed

4. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. Understanding and reducing ceruloplasmin overuse with a decision support intervention for liver disease evaluation. Am J Med. 2016;129(1):115.e17-e22. PubMed

5. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. A decision support tool to reduce overtesting for ceruloplasmin and improve adherence with clinical guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1561-1562. PubMed

6. Lichtenstein MJ, Pincus T. How useful are combinations of blood tests in “rheumatic panels” in diagnosis of rheumatic diseases? J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):435-442. PubMed

7. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321. PubMed

8. Whitehead MW, Hawkes ND, Hainsworth I, Kingham JG. A prospective study of the causes of notably raised aspartate aminotransferase of liver origin. Gut. 1999;45(1):129-133. PubMed

9. Fontana RJ. Acute liver failure including acetaminophen overdose. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(4):761-794. PubMed

10. Lee WM, Larson AM, Stravitz RT. AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases website. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/guideline_documents/alfenhanced.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed January 26, 2017.

11. Green RM, Flamm S. AGA technical review on the evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(4):1367-1384. PubMed

12. Aesif SW, Parenti DM, Lesky L, Keiser JF. A cost-effective interdisciplinary approach to microbiologic send-out test use. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(2):194-198. PubMed

13. Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765. PubMed

14. Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6(3):635-647. PubMed

15. Bacon BR, Adams PC, Kowdley KV, Powell LW, Tavill AS; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of hemochromatosis: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):328-343. PubMed

16. Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56(5):1181-1188. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Judge blocks Texas attempt to defund Planned Parenthood

A federal judge has blocked Texas from withholding Medicaid funds from Planned Parenthood centers in the state, ruling that state officials had no cause to terminate funding for the providers.

In his Feb. 21 decision, Judge Sam Sparks of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas temporarily barred Texas from taking funds from Planned Parenthood while the case proceeds. Restricting the money would deprive Medicaid patients of their right to obtain health care from their chosen providers and would potentially disrupt care for 12,500 Medicaid patients, Judge Sparks wrote.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R) pledged to appeal the ruling.

“[The] decision is disappointing and flies in the face of basic human decency,” Mr. Paxton said in a statement. “The raw, unedited footage from undercover videos exposed a brazen willingness by Planned Parenthood officials to traffic in fetal body parts, as well as manipulate the timing and method of an abortion ... No taxpayer in Texas should have to subsidize this repugnant and illegal conduct. We should never lose sight of the fact that, as long as abortion is legal in the United States, the potential for these types of horrors will continue.”

Planned Parenthood representatives did not return messages seeking comment on the ruling.

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) terminated funding for its Planned Parenthood providers in the state following a 2015 video by two anti-abortion advocates that purported to show representatives of Planned Parenthood Gulf Coast (Houston) contracting to sell aborted human fetal tissue and body parts. State authorities investigated the facility and found no wrongdoing, but a grand jury indicted the two anti-abortion activists for using fake names and identities.

Separate investigations by the Texas Attorney General’s Office, the Texas Department of State Health Services, and HHSC also found no wrongdoing, according to court documents. In December 2016 however, HHSC sent termination letters to five Texas Planned Parenthood centers, stating that the facilities were not qualified to provide medical services in a “competent, safe, legal and ethical manner” under state and federal law, according to court records. The providers and several patients sued.

In his ruling, Judge Sparks said he found no evidence indicating that an actual program violation occurred warranting termination of funding for the providers.

“After reviewing the evidence currently in the record, the court finds the Inspector General, and thus HHSC, likely acted to disenroll qualified health care providers from Medicaid without cause,” Judge Sparks wrote. “The individual plaintiffs have met their burden to establish a likelihood of success on the merits. The Inspector General did not have prima facie of evidence, or even a scintilla of evidence, to conclude the basis of termination set forth in the final notice merited finding [the plaintiffs] were not qualified.”

Similar efforts were overturned in Virgina after Governor Terry McAuliffe (D) vetoed a bill that sought to restrict state and federal funding from Planned Parenthood providers in the state. In a statement, Gov. McAuliffe said the bill would have harmed Virginians who rely on health care services and programs provided by Planned Parenthood health centers by denying them access to affordable care.

Similar legislation to defund Planned Parenthood providers was introduced by Michigan lawmakers in February.

In addition, efforts are underway at the federal level. On Feb. 16, the House passed H.J.Res.43, which would allow states to withhold Title X family planning funds from providers that offer abortion services, overturning a rule put in place at the end of the Obama administration. The resolution passed 230-188, largely along party lines. It would strike down the Obama-era rule via the 1996 Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to overturn new regulations within 60 days of their passage. H.J.Res.43 is currently before the Senate.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists expressed disappointment with the House resolution.

“The resolution allows states to discriminate against women’s health care providers for reasons unrelated to qualifications or best practices,” according to an ACOG statement. “Under this resolution, states could disqualify health centers, including Planned Parenthood, from providing Title X contraceptive and preventive care to over 4 million individuals. The Title X program is the only federal grant program exclusively dedicated to providing low-income patients with access to effective family planning and related preventive health services, including contraceptive care. Contraceptive access is essential to helping women achieve greater educational, financial, and professional success and stability. It’s critical to the economic success of this population.”

House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) has promised that the bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act will include a measure stripping funds from Planned Parenthood.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

A federal judge has blocked Texas from withholding Medicaid funds from Planned Parenthood centers in the state, ruling that state officials had no cause to terminate funding for the providers.

In his Feb. 21 decision, Judge Sam Sparks of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas temporarily barred Texas from taking funds from Planned Parenthood while the case proceeds. Restricting the money would deprive Medicaid patients of their right to obtain health care from their chosen providers and would potentially disrupt care for 12,500 Medicaid patients, Judge Sparks wrote.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R) pledged to appeal the ruling.

“[The] decision is disappointing and flies in the face of basic human decency,” Mr. Paxton said in a statement. “The raw, unedited footage from undercover videos exposed a brazen willingness by Planned Parenthood officials to traffic in fetal body parts, as well as manipulate the timing and method of an abortion ... No taxpayer in Texas should have to subsidize this repugnant and illegal conduct. We should never lose sight of the fact that, as long as abortion is legal in the United States, the potential for these types of horrors will continue.”

Planned Parenthood representatives did not return messages seeking comment on the ruling.

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) terminated funding for its Planned Parenthood providers in the state following a 2015 video by two anti-abortion advocates that purported to show representatives of Planned Parenthood Gulf Coast (Houston) contracting to sell aborted human fetal tissue and body parts. State authorities investigated the facility and found no wrongdoing, but a grand jury indicted the two anti-abortion activists for using fake names and identities.

Separate investigations by the Texas Attorney General’s Office, the Texas Department of State Health Services, and HHSC also found no wrongdoing, according to court documents. In December 2016 however, HHSC sent termination letters to five Texas Planned Parenthood centers, stating that the facilities were not qualified to provide medical services in a “competent, safe, legal and ethical manner” under state and federal law, according to court records. The providers and several patients sued.

In his ruling, Judge Sparks said he found no evidence indicating that an actual program violation occurred warranting termination of funding for the providers.

“After reviewing the evidence currently in the record, the court finds the Inspector General, and thus HHSC, likely acted to disenroll qualified health care providers from Medicaid without cause,” Judge Sparks wrote. “The individual plaintiffs have met their burden to establish a likelihood of success on the merits. The Inspector General did not have prima facie of evidence, or even a scintilla of evidence, to conclude the basis of termination set forth in the final notice merited finding [the plaintiffs] were not qualified.”

Similar efforts were overturned in Virgina after Governor Terry McAuliffe (D) vetoed a bill that sought to restrict state and federal funding from Planned Parenthood providers in the state. In a statement, Gov. McAuliffe said the bill would have harmed Virginians who rely on health care services and programs provided by Planned Parenthood health centers by denying them access to affordable care.

Similar legislation to defund Planned Parenthood providers was introduced by Michigan lawmakers in February.

In addition, efforts are underway at the federal level. On Feb. 16, the House passed H.J.Res.43, which would allow states to withhold Title X family planning funds from providers that offer abortion services, overturning a rule put in place at the end of the Obama administration. The resolution passed 230-188, largely along party lines. It would strike down the Obama-era rule via the 1996 Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to overturn new regulations within 60 days of their passage. H.J.Res.43 is currently before the Senate.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists expressed disappointment with the House resolution.

“The resolution allows states to discriminate against women’s health care providers for reasons unrelated to qualifications or best practices,” according to an ACOG statement. “Under this resolution, states could disqualify health centers, including Planned Parenthood, from providing Title X contraceptive and preventive care to over 4 million individuals. The Title X program is the only federal grant program exclusively dedicated to providing low-income patients with access to effective family planning and related preventive health services, including contraceptive care. Contraceptive access is essential to helping women achieve greater educational, financial, and professional success and stability. It’s critical to the economic success of this population.”

House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) has promised that the bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act will include a measure stripping funds from Planned Parenthood.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

A federal judge has blocked Texas from withholding Medicaid funds from Planned Parenthood centers in the state, ruling that state officials had no cause to terminate funding for the providers.

In his Feb. 21 decision, Judge Sam Sparks of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas temporarily barred Texas from taking funds from Planned Parenthood while the case proceeds. Restricting the money would deprive Medicaid patients of their right to obtain health care from their chosen providers and would potentially disrupt care for 12,500 Medicaid patients, Judge Sparks wrote.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R) pledged to appeal the ruling.

“[The] decision is disappointing and flies in the face of basic human decency,” Mr. Paxton said in a statement. “The raw, unedited footage from undercover videos exposed a brazen willingness by Planned Parenthood officials to traffic in fetal body parts, as well as manipulate the timing and method of an abortion ... No taxpayer in Texas should have to subsidize this repugnant and illegal conduct. We should never lose sight of the fact that, as long as abortion is legal in the United States, the potential for these types of horrors will continue.”

Planned Parenthood representatives did not return messages seeking comment on the ruling.

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) terminated funding for its Planned Parenthood providers in the state following a 2015 video by two anti-abortion advocates that purported to show representatives of Planned Parenthood Gulf Coast (Houston) contracting to sell aborted human fetal tissue and body parts. State authorities investigated the facility and found no wrongdoing, but a grand jury indicted the two anti-abortion activists for using fake names and identities.

Separate investigations by the Texas Attorney General’s Office, the Texas Department of State Health Services, and HHSC also found no wrongdoing, according to court documents. In December 2016 however, HHSC sent termination letters to five Texas Planned Parenthood centers, stating that the facilities were not qualified to provide medical services in a “competent, safe, legal and ethical manner” under state and federal law, according to court records. The providers and several patients sued.

In his ruling, Judge Sparks said he found no evidence indicating that an actual program violation occurred warranting termination of funding for the providers.

“After reviewing the evidence currently in the record, the court finds the Inspector General, and thus HHSC, likely acted to disenroll qualified health care providers from Medicaid without cause,” Judge Sparks wrote. “The individual plaintiffs have met their burden to establish a likelihood of success on the merits. The Inspector General did not have prima facie of evidence, or even a scintilla of evidence, to conclude the basis of termination set forth in the final notice merited finding [the plaintiffs] were not qualified.”

Similar efforts were overturned in Virgina after Governor Terry McAuliffe (D) vetoed a bill that sought to restrict state and federal funding from Planned Parenthood providers in the state. In a statement, Gov. McAuliffe said the bill would have harmed Virginians who rely on health care services and programs provided by Planned Parenthood health centers by denying them access to affordable care.

Similar legislation to defund Planned Parenthood providers was introduced by Michigan lawmakers in February.

In addition, efforts are underway at the federal level. On Feb. 16, the House passed H.J.Res.43, which would allow states to withhold Title X family planning funds from providers that offer abortion services, overturning a rule put in place at the end of the Obama administration. The resolution passed 230-188, largely along party lines. It would strike down the Obama-era rule via the 1996 Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to overturn new regulations within 60 days of their passage. H.J.Res.43 is currently before the Senate.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists expressed disappointment with the House resolution.

“The resolution allows states to discriminate against women’s health care providers for reasons unrelated to qualifications or best practices,” according to an ACOG statement. “Under this resolution, states could disqualify health centers, including Planned Parenthood, from providing Title X contraceptive and preventive care to over 4 million individuals. The Title X program is the only federal grant program exclusively dedicated to providing low-income patients with access to effective family planning and related preventive health services, including contraceptive care. Contraceptive access is essential to helping women achieve greater educational, financial, and professional success and stability. It’s critical to the economic success of this population.”

House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) has promised that the bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act will include a measure stripping funds from Planned Parenthood.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Forging ahead

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 45-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with 2 days of generalized, progressive weakness. Her ability to walk and perform daily chores was increasingly limited. On the morning of her presentation, she was unable to stand up without falling.

A complaint of weakness must be classified as either functional weakness related to a systemic process or true neurologic weakness from dysfunction of the central nervous system (eg, brain, spinal cord) or peripheral nervous system (eg, anterior horn cell, nerve, neuromuscular junction, or muscle). More information on her clinical course and a detailed neurologic exam will help clarify this key branch point.

She was 2 weeks status-post laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and gastric band removal performed in Europe. Immediately following surgery, she experienced abdominal discomfort and nausea with occasional nonbloody, nonbilious emesis, attributed to expected postoperative anatomical changes. She developed a postoperative pneumonia treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate. She tolerated her flight back to the United States, but her abdominal discomfort persisted and she had minimal oral intake due to her nausea.

Functional weakness may stem from hypovolemia from insufficient oral intake, anemia related to the recent surgery, electrolyte abnormalities, chronic nutritional issues associated with obesity and weight-reduction surgery, and pneumonia. Prolonged air travel, obesity, and recent surgery place her at risk for venous thromboembolism, which may manifest as reduced exercise tolerance. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain persisting for 2 weeks after a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery raises several concerns, including gastric remnant distension (although hiccups are often prominent); stomal stenosis, which typically presents several weeks after surgery; marginal ulceration; or infection at the surgical site or from an anastomotic leak. She may also have a surgery- or medication-related myopathy.

The patient had a history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, migraine headaches, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Four years previously, she had undergone gastric banding complicated by band migration and ulceration at the banding site. Her medications were amlodipine, losartan, ranitidine, acetaminophen, and nadroparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis during her flight. She denied alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drug use. On further questioning, she reported diaphoresis, mild dyspnea, loose stools, and a sensation of numbness and “heaviness” in her arms. Her abdominal pain was limited to the surgical incision and was controlled with acetaminophen. She denied fevers, cough, chest pain, diplopia, or dysphagia.

Heaviness in both arms could result from an acutely presenting myopathic or neuropathic process, while the coexistence of numbness suggests a sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Obesity and gastric bypass surgery increase her nutritional risk, and thiamine deficiency may present as an acute axonal polyneuropathy (ie, beriberi). Unlike vitamin B12 deficiency, which may take years to develop, thiamine deficiency can present within 4 weeks of gastric bypass surgery. Her dyspnea may be a manifestation of diaphragmatic weakness, although her ostensibly treated pneumonia or as of yet unproven postoperative anemia may be contributing. Chemoprophylaxis mitigates her risk of venous thromboembolism, which is, nonetheless, unlikely to account for the gastrointestinal symptoms and upper extremity weakness. If she is continuing to take amlodipine and losartan but has become volume-depleted, hypotension may be contributing to the generalized weakness.

Physical examination revealed an obese, pale and diaphoretic woman. Her temperature was 36.9°C, heart rate 77 beats per minute, blood pressure 158/90 mm Hg, respiratory rate 28 breaths per minute, and O2 saturation 99% on ambient air. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy and a normal thyroid exam. There were no murmurs on cardiac examination, and jugular venous pressure was estimated at 10 cm of water. Her lung sounds were clear. Her abdomen was soft, nondistended, with localized tenderness and fluctuance around the midline surgical incision with a small amount of purulent drainage. She was alert and oriented to name, date, place, and situation. Cranial nerves II through XII were grossly intact. Strength was 4/5 in bilateral biceps, triceps and distal hand and finger extensors, 3/5 in bilateral deltoids. Strength in hip flexors was 4/5 and it was 5/5 in distal lower extremities. Sensation was intact to pinprick in upper and lower extremities. Biceps reflexes were absent; patellar and ankle reflexes were 1+ and symmetric. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable.

The patient has symmetric proximal muscle weakness with upper extremity predominance and preserved strength in her distal lower extremities. A myopathy could explain this pattern of weakness, further substantiated by absent reflexes and reportedly intact sensation. Subacute causes of myopathy include hypokalemia, hyperkalemia, toxic myopathies from medications, or infection-induced rhabdomyolysis. However, she does not report muscle pain, and the loss of reflexes is faster than would be expected with a myopathy. A more thorough sensory examination would inform the assessment of potential neuropathic processes. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is possible; it most commonly presents as an ascending, distally predominant acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP), although her upper extremity weakness predominates and there are no clear sensory changes. It remains to be determined how her wound infection might relate to her overall presentation.

Her white blood cell count was 12,600/μL (reference range: 3,400-10,000/μL), hemoglobin was 10.2 g/dL, and platelet count was 698,000/μL. Mean corpuscular volume was 86 fL. Serum chemistries were: sodium 138 mEq/L, potassium 3.8 mEq/L, chloride 106 mmol/L, bicarbonate 15 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 5 mg/dL, creatinine 0.65 mg/dL, glucose 125 mg/dL, calcium 8.3 mg/dL, magnesium 1.9 mg/dL, phosphorous 2.4 mg/dL, and lactate 1.8 mmol/L (normal: < 2.0 mmol/L). Creatinine kinase (CK), liver function tests, and coagulation panel were normal. Total protein was 6.4 g/dL, and albumin was 2.7 g/dL. Venous blood gas was: pH 7.39 and PCO2 25 mmHg. Urinalysis revealed ketones. Blood and wound cultures were sent for evaluation. A chest x-ray was unremarkable. An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a multiloculated rim-enhancing fluid collection in the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 1).

She does not have any notable electrolyte derangements that would account for her weakness, and the normal creatinine kinase lowers the probability of a myopathy and excludes rhabdomyolysis. Progression of weakness from proximal to distal muscles in a symmetric fashion is consistent with botulism, and she has an intra-abdominal wound infection that could be harboring Clostridium botulinum. Nonetheless, the normal cranial nerve exam and the rarity of botulism occurring with surgical wounds argue against this diagnosis. She should receive intravenous (IV) thiamine for the possibility of beriberi. A lumbar puncture should be performed to assess for albuminocytologic dissociation, which can be seen in patients with GBS.

The patient received high-dose IV thiamine, IV vancomycin, IV piperacillin-tazobactam, and acetaminophen. Over the subsequent 4 hours, her anion gap acidosis worsened. She declined arterial puncture. Repeat venous blood gas was: pH 7.22, PCO2 28 mmHg, and bicarbonate 11 mmol/L. Lactate and glucose were normal. Serum osmolarity was 292 mmol/kg (reference range: 283-301 mmol/kg). She was started on an IV sodium bicarbonate infusion without improvement in her acidemia.

An acute anion gap metabolic acidosis suggests a limited differential diagnosis that includes lactic acidosis, D-lactic acidosis, severe starvation ketoacidosis, acute renal failure, salicylate, or other drug or poison ingestion. Starvation ketoacidosis may be contributing, but a bicarbonate value this low would be unusual. There is no history of alcohol use or other ingestions, and the normal serum osmolality and low osmolal gap (less than 10 mOsm/kg) argue against a poisoning with ethanol, ethylene glycol, or methanol. The initial combined anion gap metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis is consistent with salicylate toxicity, but she does not report aspirin ingestion. Acetaminophen use in the setting of malnutrition or starvation physiology raises the possibility of 5-oxoproline accumulation.

Routine serum lactate does not detect D-lactate, which is produced by colonic bacteria and has been reported in short bowel syndrome and following intestinal bypass surgery. This may occur weeks to months after intestinal procedures, following ingestion of a heavy carbohydrate load, and almost invariably presents with altered mental status and increased anion gap metabolic acidosis, although generalized weakness has been reported.

A surgical consultant drained her wound infection. Fluid Gram stain was negative. D-lactate, salicylate and acetaminophen levels were undetectable. Thiamine pyrophosphate level was 229 nmol/L (reference range: 78-185 nmol/L). Acetaminophen was discontinued and N-acetylcysteine infusion was started for possible 5-oxoprolinemia. Her anion gap acidosis rapidly improved. Twelve hours after admission, she reported sudden onset of blurry vision. Her vital signs were: temperature 37oC, heart rate 110 beats per minute, respiratory rate 40 breaths per minute, blood pressure 168/90, and oxygen saturation 100% on ambient air. Telemetry showed ventricular bigeminy. On examination, she was unable to abduct her right eye; muscle strength was 1/5 in all extremities; biceps, ankle, and patellar reflexes were absent.

Her neurological deficits have progressed over hours to near complete paralysis, asymmetric cranial nerve paresis, and areflexia. Although botulism can cause blurred vision and absent deep tendon reflexes, patients almost always have symmetrical bulbar findings followed by descending paralysis. Should the “numbness” in her arms reported earlier represent undetected sensory deficits, this, too would be inconsistent with botulism.

A diagnosis of GBS ties together several aspects of her presentation and clinical course. Several variants show different patterns of weakness and may involve cranial nerves. Her tachypnea and dyspnea are concerning signs of potential impending respiratory failure. The ventricular bigeminy and mild hypertension could represent autonomic dysfunction that is seen in many cases of GBS.

She was intubated for airway protection. Computed tomography angiography and magnetic resonance imaging of her brain were normal. Cerebral spinal fluid analysis obtained through lumbar puncture showed the following: white blood cell count 3/μL, red blood cell count 11/μL, protein 63 mg/dL (reference range: 15-60mg/dL), and glucose 128 mg/dL (reference range: 40-80mg/dL).

The lumbar puncture is consistent with GBS given the slightly elevated protein and cell count well below 50/μL. Given the severity of her symptoms, treatment with IV immunoglobulin or plasmapheresis should be initiated. Nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electromyography (EMG) are indicated for diagnostic confirmation.

EMG and NCS revealed a severe sensorimotor polyneuropathy with demyelinating features including a conduction block at a noncompressible site, consistent with AIDP. Left sural nerve biopsy confirmed acute demyelinating and mild axonal neuropathy (Figure 2). On hospital day 2, treatment with IV immunoglobulins (IVIG) was initiated; however, she developed anaphylaxis following her second administration and subsequently received plasmapheresis. A tracheostomy was performed for respiratory muscle weakness, and she was discharged to a nursing facility. C. botulinum cultures from the wound eventually returned negative. Following her hospitalization, a serum 5-oxoproline level sent 10 hours after admission returned as elevated, confirming the additional diagnosis of 5-oxoprolinemia. On follow-up, she can sit up and feed herself without assistance, and her gait continues to improve with physical therapy.

DISCUSSION

This patient presented with rapidly progressive weakness that developed in the 2 weeks following bariatric surgery. In the postsurgical setting, patient complaints of weakness are commonly encountered and can pose a diagnostic challenge. Asthenia (ie, general loss of strength or energy) is frequently reported in the immediate postoperative period, and may result from the stress of surgery, pain, deconditioning, or infection. This must be distinguished from true neurologic weakness, which results from dysfunction of the brain, spinal cord, nerve, neuromuscular junction, or muscle. The initial history can help elucidate the inciting events such as preceding surgery, infections or ingestions, and can also categorize the pattern of weakness. The neurologic examination can localize the pathology within the neuraxis. EMG and NCS can distinguish neuropathy from radiculopathy, and categorize the process as axonal, demyelinating, or mixed. In this case, the oculomotor weakness, sensory abnormalities and areflexia signaled a severe sensorimotor polyneuropathy, and EMG/NCS confirmed a demyelinating process consistent with GBS.

Guillain-Barré syndrome is an acute, immune-mediated polyneuropathy. Patients with GBS often present with a preceding respiratory or diarrheal illness; however, the stress of a recent surgery can serve as an inciting event. The syndrome, acute postgastric reduction surgery (APGARS) neuropathy, was introduced in the literature in 2002, describing 3 patients who presented with progressive vomiting, weakness, and hyporeflexia following bariatric surgery.1 The term has been used to describe bariatric surgery patients who developed postoperative quadriparesis, cranial nerve deficits, and respiratory compromise.2 Given the clinical heterogeneity in the literature with relation to APGARS, it is probable that the cases described could result from multiple etiologies. While GBS is purely immune-mediated and can be precipitated by the stress of surgery itself, postbariatric surgery patients are susceptible to many nutritional deficiencies that can lead to similar presentations.3 For example, thiamine (vitamin B1) and cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiencies cause distinct postbariatric surgery neuropathies.4 Thiamine deficiency may manifest weeks to months after surgery and can rapidly progress, whereas cobalamin deficiency generally develops over 3 to 5 years. Both of these syndromes demonstrate an axonal pattern of nerve injury on EMG/NCS, in contrast to the demyelinating pattern typically seen in GBS. In addition, bariatric surgery patients are at higher risk for copper deficiency, which usually presents as a myeloneuropathy with subacute gait decline and upper motor neuron signs including spasticity.

Although GBS classically presents with symmetric ascending weakness and sensory abnormalities, it may manifest in myriad ways. Factors influencing the presentation include the types of nerve fibers involved (motor, sensory, cranial or autonomic), the predominant mode of injury (axonal vs demyelinating), and the presence or absence of alteration in consciousness.5 The most common form of GBS is AIDP. The classic presentation involves paresthesias in the fingertips and toes followed by lower extremity weakness that ascends over hours to days to involve the arms and potentially the muscles of respiration. A minority of patients with GBS first experience weakness in the upper extremities or facial muscles, and oculomotor involvement is rare.5 Pain is common and often severe.6 Dysautonomia affects most patients with GBS and may manifest as labile blood pressure or arrhythmias.5 Several variant GBS presentation patterns have been described, including acute motor axonal neuropathy, a pure motor form of GBS; ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and areflexia in Miller Fisher syndrome; and alteration in consciousness, hyperreflexia, ataxia, and ophthalmoparesis in Bickerstaff’s brain stem encephalitis.5

Patients with GBS can progress rapidly to respiratory failure. Serial neurologic exams may signal the diagnosis and inform triage to the appropriate level of care. Measurement of bedside pulmonary function, including mean inspiratory force and functional vital capacity, help to determine if there is weakness of diaphragmatic muscles. Patients with signs or symptoms of diaphragmatic weakness require monitoring in an intensive care unit and potentially early intubation. Treatment with IVIG or plasmapheresis has been found to hasten recovery from GBS, including earlier improvement in muscle strength and a reduced need for mechanical ventilation.7 Treatment selection is based on available resources as both modalities are felt to be equivalent.The majority of patients with GBS make a full recovery over a period of weeks to months, although many have persistent motor weakness. Despite immunotherapy, up to 20% of patients remain severely disabled and approximately 5% die.8 Advanced age, rapid progression of weakness over a period of less than 72 hours, need for mechanical ventilation, and absent compound muscle action potentials on NCS are all associated with prolonged and incomplete recovery.9

This patient developed respiratory failure within 12 hours of hospitalization, prior to being diagnosed with GBS. Even in that short time, the treating clinicians encountered a series of clinical diversions. The initial proximal pattern of muscle weakness suggested a possible myopathic process; the wound infection introduced the possibility of botulism; obesity and recent bariatric surgery triggered concern for thiamine deficiency; and the anion gap acidosis from 5-oxoprolinemia created yet another clinical detour. While the path from presentation to diagnosis is seldom a straight line, when faced with rapidly progressive weakness, it is paramount to forge ahead with an efficient diagnostic evaluation and timely therapeutic intervention.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- A complaint of general weakness requires distinction between asthenia (ie, general loss of strength or energy) and true neuromuscular weakness from dysfunction of the brain, spinal cord, nerve, neuromuscular junction, and/or muscle.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome may present in a variety of atypical fashions not limited to ascending, distally predominant weakness.

- Acute postgastric reduction surgery neuropathy should be considered in patients presenting with weakness, vomiting, or hyporeflexia after bariatric surgery.

- Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy may rapidly progress to respiratory failure, and warrants serial neurologic examinations, monitoring of pulmonary function, and an expedited diagnostic evaluation.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Akhtar M, Collins MP, Kissel JT. Acute postgastric reduction surgery (APGARS) Neuropathy: A polynutritional, multisystem disorder. Neurology. 2002;58:A68. PubMed

2. Chang CG, Adams-Huet B, Provost DA. Acute post-gastric reduction surgery (APGARS) neuropathy. Obes Surg. 2004;14(2):182-189. PubMed

3. Chang CG, Helling TS, Black WE, Rymer MM. Weakness after gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2002;12(4):592-597. PubMed

4. Shankar P, Boylan M, Sriram K. Micronutrient deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nutrition. 2010;26(11-12):1031-1037. PubMed

5. Dimachkie MM, Barohn RJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome and variants. Neurol Clin. 2013;31(2):491-510. PubMed

6. Ruts L, Drenthen J, Jongen JL, et al. Pain in Guillain-Barré syndrome: a long-term follow-up study. Neurology. 2010;75(16):1439-1447. PubMed

7. Hughes RAC, Wijdicks EFM, Barohn R, et al: Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: immunotherapy for Guillain-Barré syndrome: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2003;61:736-740. PubMed

8. Hughes RA, Swan AV, Raphaël JC, Annane D, van Koningsveld R, van Doorn PA. Immunotherapy for Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 9):2245-2257. PubMed

9. Rajabally YA, Uncini A. Outcome and predictors in Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(7):711-718. PubMed

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 45-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with 2 days of generalized, progressive weakness. Her ability to walk and perform daily chores was increasingly limited. On the morning of her presentation, she was unable to stand up without falling.

A complaint of weakness must be classified as either functional weakness related to a systemic process or true neurologic weakness from dysfunction of the central nervous system (eg, brain, spinal cord) or peripheral nervous system (eg, anterior horn cell, nerve, neuromuscular junction, or muscle). More information on her clinical course and a detailed neurologic exam will help clarify this key branch point.

She was 2 weeks status-post laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and gastric band removal performed in Europe. Immediately following surgery, she experienced abdominal discomfort and nausea with occasional nonbloody, nonbilious emesis, attributed to expected postoperative anatomical changes. She developed a postoperative pneumonia treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate. She tolerated her flight back to the United States, but her abdominal discomfort persisted and she had minimal oral intake due to her nausea.

Functional weakness may stem from hypovolemia from insufficient oral intake, anemia related to the recent surgery, electrolyte abnormalities, chronic nutritional issues associated with obesity and weight-reduction surgery, and pneumonia. Prolonged air travel, obesity, and recent surgery place her at risk for venous thromboembolism, which may manifest as reduced exercise tolerance. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain persisting for 2 weeks after a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery raises several concerns, including gastric remnant distension (although hiccups are often prominent); stomal stenosis, which typically presents several weeks after surgery; marginal ulceration; or infection at the surgical site or from an anastomotic leak. She may also have a surgery- or medication-related myopathy.