User login

Dysmenorrhea and ginger

Up to 90% of reproductive women around the world describe experiencing painful menstrual periods (dysmenorrhea) at some point. Younger women struggle more than older women. Dysmenorrhea can lead to absenteeism and presenteeism to the tune of about $2 billion annually.

The next step was to find an alternate treatment method. Ginger root is used throughout the world as a seasoning, spice, and medicine. Ginger has been shown to inhibit COX-2 and has been studied for its potential role in reducing pain and inflammation. As a result, ginger may have a role in the treatment of dysmenorrhea.

James W. Daily, PhD, conducted a systematic review of the literature on the efficacy of ginger for treating primary dysmenorrhea (Pain Med. 2015 Dec;16[12]:2243-55).

It included all randomized trials investigating the effect of ginger powder on younger women. Included studies evaluated ginger efficacy on individuals aged 13-30 years. Most included studies excluded women with irregular menstrual cycles and individuals using hormonal medications, oral or intrauterine contraceptives, or a pregnancy history. Dosing was 750-2,000 mg ginger powder capsules per day for the first 3 days of the menstrual cycle.

Four studies were included in the meta-analysis, which suggested that ginger powder given during the first 3-4 days of the menstrual cycle was associated with significant reduction in the pain visual analog scale (risk ratio, –1.85; 95% confidence interval: –2.87 to –0.84; P = .0003).

I am not a consistent proponent of alternative therapies but mostly because it is difficult for me to keep up on the evidence for these treatment options. In this case, my bias is that individuals in this age group are much more willing to engage with alternative therapies and offering them may build trust.

For these patients, offering ginger powder may engage patients in self-help and help them appreciate you as a clinician willing to embrace alternative therapies. The hard part is recommending a brand that you know and trust, complicated by the lack of oversight and quality control for over-the-counter, nontraditional therapies.

Dr. Ebbert is a professor of medicine and general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition, nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

Up to 90% of reproductive women around the world describe experiencing painful menstrual periods (dysmenorrhea) at some point. Younger women struggle more than older women. Dysmenorrhea can lead to absenteeism and presenteeism to the tune of about $2 billion annually.

The next step was to find an alternate treatment method. Ginger root is used throughout the world as a seasoning, spice, and medicine. Ginger has been shown to inhibit COX-2 and has been studied for its potential role in reducing pain and inflammation. As a result, ginger may have a role in the treatment of dysmenorrhea.

James W. Daily, PhD, conducted a systematic review of the literature on the efficacy of ginger for treating primary dysmenorrhea (Pain Med. 2015 Dec;16[12]:2243-55).

It included all randomized trials investigating the effect of ginger powder on younger women. Included studies evaluated ginger efficacy on individuals aged 13-30 years. Most included studies excluded women with irregular menstrual cycles and individuals using hormonal medications, oral or intrauterine contraceptives, or a pregnancy history. Dosing was 750-2,000 mg ginger powder capsules per day for the first 3 days of the menstrual cycle.

Four studies were included in the meta-analysis, which suggested that ginger powder given during the first 3-4 days of the menstrual cycle was associated with significant reduction in the pain visual analog scale (risk ratio, –1.85; 95% confidence interval: –2.87 to –0.84; P = .0003).

I am not a consistent proponent of alternative therapies but mostly because it is difficult for me to keep up on the evidence for these treatment options. In this case, my bias is that individuals in this age group are much more willing to engage with alternative therapies and offering them may build trust.

For these patients, offering ginger powder may engage patients in self-help and help them appreciate you as a clinician willing to embrace alternative therapies. The hard part is recommending a brand that you know and trust, complicated by the lack of oversight and quality control for over-the-counter, nontraditional therapies.

Dr. Ebbert is a professor of medicine and general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition, nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

Up to 90% of reproductive women around the world describe experiencing painful menstrual periods (dysmenorrhea) at some point. Younger women struggle more than older women. Dysmenorrhea can lead to absenteeism and presenteeism to the tune of about $2 billion annually.

The next step was to find an alternate treatment method. Ginger root is used throughout the world as a seasoning, spice, and medicine. Ginger has been shown to inhibit COX-2 and has been studied for its potential role in reducing pain and inflammation. As a result, ginger may have a role in the treatment of dysmenorrhea.

James W. Daily, PhD, conducted a systematic review of the literature on the efficacy of ginger for treating primary dysmenorrhea (Pain Med. 2015 Dec;16[12]:2243-55).

It included all randomized trials investigating the effect of ginger powder on younger women. Included studies evaluated ginger efficacy on individuals aged 13-30 years. Most included studies excluded women with irregular menstrual cycles and individuals using hormonal medications, oral or intrauterine contraceptives, or a pregnancy history. Dosing was 750-2,000 mg ginger powder capsules per day for the first 3 days of the menstrual cycle.

Four studies were included in the meta-analysis, which suggested that ginger powder given during the first 3-4 days of the menstrual cycle was associated with significant reduction in the pain visual analog scale (risk ratio, –1.85; 95% confidence interval: –2.87 to –0.84; P = .0003).

I am not a consistent proponent of alternative therapies but mostly because it is difficult for me to keep up on the evidence for these treatment options. In this case, my bias is that individuals in this age group are much more willing to engage with alternative therapies and offering them may build trust.

For these patients, offering ginger powder may engage patients in self-help and help them appreciate you as a clinician willing to embrace alternative therapies. The hard part is recommending a brand that you know and trust, complicated by the lack of oversight and quality control for over-the-counter, nontraditional therapies.

Dr. Ebbert is a professor of medicine and general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition, nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on OTC Adult Acne Products

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on adult acne products. Consideration must be given to:

- Bioclear Face Lotion and Face Cream

Jan Marini Skin Research, Inc

“These products contain a powerful combination of glycolic, salicylic, and azelaic acids to smooth and brighten acne-prone skin.”—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD, Gahanna, Ohio

- Neutrogena Clear Pore Cleanser/Mask

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

“This is a good daily product for acne-prone skin. It is formulated with benzoyl peroxide and can be used as a daily wash or mask.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Offects Sulfur Masque Acne Treatment

ZO Skin Health Inc

“This nonirritating mask reduces inflammation and oiliness and is safe to use in pregnancy.”—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD, Gahanna, Ohio

- PanOxyl Acne Foaming Wash and Acne Creamy Wash

Stiefel, a GSK company

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, as well as products for dry cuticles, hyperhidrosis, and sensitive skin will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on adult acne products. Consideration must be given to:

- Bioclear Face Lotion and Face Cream

Jan Marini Skin Research, Inc

“These products contain a powerful combination of glycolic, salicylic, and azelaic acids to smooth and brighten acne-prone skin.”—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD, Gahanna, Ohio

- Neutrogena Clear Pore Cleanser/Mask

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

“This is a good daily product for acne-prone skin. It is formulated with benzoyl peroxide and can be used as a daily wash or mask.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Offects Sulfur Masque Acne Treatment

ZO Skin Health Inc

“This nonirritating mask reduces inflammation and oiliness and is safe to use in pregnancy.”—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD, Gahanna, Ohio

- PanOxyl Acne Foaming Wash and Acne Creamy Wash

Stiefel, a GSK company

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, as well as products for dry cuticles, hyperhidrosis, and sensitive skin will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on adult acne products. Consideration must be given to:

- Bioclear Face Lotion and Face Cream

Jan Marini Skin Research, Inc

“These products contain a powerful combination of glycolic, salicylic, and azelaic acids to smooth and brighten acne-prone skin.”—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD, Gahanna, Ohio

- Neutrogena Clear Pore Cleanser/Mask

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

“This is a good daily product for acne-prone skin. It is formulated with benzoyl peroxide and can be used as a daily wash or mask.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Offects Sulfur Masque Acne Treatment

ZO Skin Health Inc

“This nonirritating mask reduces inflammation and oiliness and is safe to use in pregnancy.”—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD, Gahanna, Ohio

- PanOxyl Acne Foaming Wash and Acne Creamy Wash

Stiefel, a GSK company

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, as well as products for dry cuticles, hyperhidrosis, and sensitive skin will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

Active surveillance an option for patients with mRCC

ORLANDO – Active surveillance prior to initiating targeted therapy could be an option for some patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), according to new findings.

“Active surveillance does not affect the efficacy of subsequent therapies,” said lead study author Davide Bimbatti, MD, of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata, University of Verona (Italy). “In selected patients, active surveillance allows us to delay the start of systemic treatment, and patients in active surveillance rarely have a worsening of prognostic class,” he said in a press briefing held at the 2017 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, ASTRO, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

Targeted therapies can improve survival in mRCC but treatment is not curative and associated toxicities can interfere with quality of life and force patients to discontinue treatment. Active surveillance delays the use of systemic therapy and associated toxicities, and is a feasible strategy for patients with indolent disease.

However, the effect of active surveillance on tumor burden and prognosis have not been investigated.

To address this issue, Dr. Bimbatti and his colleagues conducted a retrospective study and evaluated the effect of active surveillance on overall survival and postsurveillance overall survival, progression-free survival, and tumor burden (a measure of the number of sites and tumor size).

The study cohort included 48 patients with mRCC who underwent active surveillance during 2007-2016 and changes in the International mRCC Database Consortium (IMDC) prognostic class and tumor burden were analyzed for associations with these endpoints.

At baseline, 69% of patients had a favorable prognostic IMDC class, 25% were at an intermediate class, and 6% had a poor class designation. The main sites of metastases were lung (56%), lymph nodes (25%), pancreas (14%), adrenal gland (8%), CNS (8%), and bone (6%).

At a median follow-up of 37.3 months, 79.2% of patients were still alive and, at a median surveillance duration of 16.7 months, 71% of patients had begun a targeted therapy. There were a total of 17 deaths (33%).

Median progression-free survival was 16.6 months and median postsurveillance overall survival was 39.1 months.

During active surveillance, only four patients transitioned from good to intermediate IMDC prognostic class. IMDC classes overall maintained their prognostic value during active surveillance, Dr. Bimbatti said. IMDC class was also the only factor that was associated with time on surveillance.

At baseline, tumor burden was in one site for 65% of patients, two sites in 31%, and three or more sites for 4%, but during active surveillance, changes occurred in one site in 35% of patients, two in 48%, and more than two in 17%.

A change in tumor burden (greater than or equal to 2.2 times the original burden), however, was related to poorer postsurveillance survival (hazard ratio,1.23; P less than .01), but not with overall survival (HR, 1.0; P less than .05).

Conversely, any increase in metastatic sites was associated with both significantly worse postsurveillance and overall survival (HR = 2.6, P = 0.04; and HR = 3.3, P less than 0.01).

Commenting on the study, Primo N. Lara Jr., MD, of the University of California, Davis, Comprehensive Cancer Center explained that active surveillance “remains a reasonable option for highly selected patients.”

“[The investigators] provide reassuring data that active surveillance does not alter the IMDC risk grouping,” he said, and that the results of this study overall, were similar to those of prior research.

There were some limitations to the study, in that it was retrospective and conducted at a single institution. “It also failed to account for psychosocial issues such as anxiety during the active surveillance phase,” he said.

Critical questions also remain, Dr. Lara added, such as what are the validated selection criteria for patients entering active surveillance or what is the threshold of tumor burden to warrant active surveillance discontinuation.

The funding source was not disclosed. Dr. Bimbatti and his coauthors have no disclosures. Dr. Lara reports financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

ORLANDO – Active surveillance prior to initiating targeted therapy could be an option for some patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), according to new findings.

“Active surveillance does not affect the efficacy of subsequent therapies,” said lead study author Davide Bimbatti, MD, of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata, University of Verona (Italy). “In selected patients, active surveillance allows us to delay the start of systemic treatment, and patients in active surveillance rarely have a worsening of prognostic class,” he said in a press briefing held at the 2017 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, ASTRO, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

Targeted therapies can improve survival in mRCC but treatment is not curative and associated toxicities can interfere with quality of life and force patients to discontinue treatment. Active surveillance delays the use of systemic therapy and associated toxicities, and is a feasible strategy for patients with indolent disease.

However, the effect of active surveillance on tumor burden and prognosis have not been investigated.

To address this issue, Dr. Bimbatti and his colleagues conducted a retrospective study and evaluated the effect of active surveillance on overall survival and postsurveillance overall survival, progression-free survival, and tumor burden (a measure of the number of sites and tumor size).

The study cohort included 48 patients with mRCC who underwent active surveillance during 2007-2016 and changes in the International mRCC Database Consortium (IMDC) prognostic class and tumor burden were analyzed for associations with these endpoints.

At baseline, 69% of patients had a favorable prognostic IMDC class, 25% were at an intermediate class, and 6% had a poor class designation. The main sites of metastases were lung (56%), lymph nodes (25%), pancreas (14%), adrenal gland (8%), CNS (8%), and bone (6%).

At a median follow-up of 37.3 months, 79.2% of patients were still alive and, at a median surveillance duration of 16.7 months, 71% of patients had begun a targeted therapy. There were a total of 17 deaths (33%).

Median progression-free survival was 16.6 months and median postsurveillance overall survival was 39.1 months.

During active surveillance, only four patients transitioned from good to intermediate IMDC prognostic class. IMDC classes overall maintained their prognostic value during active surveillance, Dr. Bimbatti said. IMDC class was also the only factor that was associated with time on surveillance.

At baseline, tumor burden was in one site for 65% of patients, two sites in 31%, and three or more sites for 4%, but during active surveillance, changes occurred in one site in 35% of patients, two in 48%, and more than two in 17%.

A change in tumor burden (greater than or equal to 2.2 times the original burden), however, was related to poorer postsurveillance survival (hazard ratio,1.23; P less than .01), but not with overall survival (HR, 1.0; P less than .05).

Conversely, any increase in metastatic sites was associated with both significantly worse postsurveillance and overall survival (HR = 2.6, P = 0.04; and HR = 3.3, P less than 0.01).

Commenting on the study, Primo N. Lara Jr., MD, of the University of California, Davis, Comprehensive Cancer Center explained that active surveillance “remains a reasonable option for highly selected patients.”

“[The investigators] provide reassuring data that active surveillance does not alter the IMDC risk grouping,” he said, and that the results of this study overall, were similar to those of prior research.

There were some limitations to the study, in that it was retrospective and conducted at a single institution. “It also failed to account for psychosocial issues such as anxiety during the active surveillance phase,” he said.

Critical questions also remain, Dr. Lara added, such as what are the validated selection criteria for patients entering active surveillance or what is the threshold of tumor burden to warrant active surveillance discontinuation.

The funding source was not disclosed. Dr. Bimbatti and his coauthors have no disclosures. Dr. Lara reports financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

ORLANDO – Active surveillance prior to initiating targeted therapy could be an option for some patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), according to new findings.

“Active surveillance does not affect the efficacy of subsequent therapies,” said lead study author Davide Bimbatti, MD, of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata, University of Verona (Italy). “In selected patients, active surveillance allows us to delay the start of systemic treatment, and patients in active surveillance rarely have a worsening of prognostic class,” he said in a press briefing held at the 2017 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, ASTRO, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

Targeted therapies can improve survival in mRCC but treatment is not curative and associated toxicities can interfere with quality of life and force patients to discontinue treatment. Active surveillance delays the use of systemic therapy and associated toxicities, and is a feasible strategy for patients with indolent disease.

However, the effect of active surveillance on tumor burden and prognosis have not been investigated.

To address this issue, Dr. Bimbatti and his colleagues conducted a retrospective study and evaluated the effect of active surveillance on overall survival and postsurveillance overall survival, progression-free survival, and tumor burden (a measure of the number of sites and tumor size).

The study cohort included 48 patients with mRCC who underwent active surveillance during 2007-2016 and changes in the International mRCC Database Consortium (IMDC) prognostic class and tumor burden were analyzed for associations with these endpoints.

At baseline, 69% of patients had a favorable prognostic IMDC class, 25% were at an intermediate class, and 6% had a poor class designation. The main sites of metastases were lung (56%), lymph nodes (25%), pancreas (14%), adrenal gland (8%), CNS (8%), and bone (6%).

At a median follow-up of 37.3 months, 79.2% of patients were still alive and, at a median surveillance duration of 16.7 months, 71% of patients had begun a targeted therapy. There were a total of 17 deaths (33%).

Median progression-free survival was 16.6 months and median postsurveillance overall survival was 39.1 months.

During active surveillance, only four patients transitioned from good to intermediate IMDC prognostic class. IMDC classes overall maintained their prognostic value during active surveillance, Dr. Bimbatti said. IMDC class was also the only factor that was associated with time on surveillance.

At baseline, tumor burden was in one site for 65% of patients, two sites in 31%, and three or more sites for 4%, but during active surveillance, changes occurred in one site in 35% of patients, two in 48%, and more than two in 17%.

A change in tumor burden (greater than or equal to 2.2 times the original burden), however, was related to poorer postsurveillance survival (hazard ratio,1.23; P less than .01), but not with overall survival (HR, 1.0; P less than .05).

Conversely, any increase in metastatic sites was associated with both significantly worse postsurveillance and overall survival (HR = 2.6, P = 0.04; and HR = 3.3, P less than 0.01).

Commenting on the study, Primo N. Lara Jr., MD, of the University of California, Davis, Comprehensive Cancer Center explained that active surveillance “remains a reasonable option for highly selected patients.”

“[The investigators] provide reassuring data that active surveillance does not alter the IMDC risk grouping,” he said, and that the results of this study overall, were similar to those of prior research.

There were some limitations to the study, in that it was retrospective and conducted at a single institution. “It also failed to account for psychosocial issues such as anxiety during the active surveillance phase,” he said.

Critical questions also remain, Dr. Lara added, such as what are the validated selection criteria for patients entering active surveillance or what is the threshold of tumor burden to warrant active surveillance discontinuation.

The funding source was not disclosed. Dr. Bimbatti and his coauthors have no disclosures. Dr. Lara reports financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

AT THE GENITOURINARY CANCERS SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Active surveillance may be an option for some patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Major finding: A change in tumor burden (greater than or equal to 2.2 times the original burden), however, was related to poorer postsurveillance survival (HR,1.23; P less than .01) but not with overall survival (HR, 1.0; P less than.05).

Data source: Retrospective single center study that evaluated active surveillance in 48 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Disclosures: The funding source was not disclosed. Dr. Bimbatti and his coauthors have no disclosures. Dr. Lara reports financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Vascular surgeons underutilize palliative care planning

Investment in advanced palliative care planning has the potential to improve the quality of care for vascular surgery patients, according to investigators from Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Dale G. Wilson, MD, and his colleagues performed a retrospective review of electronic medical records for 111 patients, who died while on the vascular surgery service at the OHSU Hospital during 2005-2014.

Almost three-quarters (73%) of patients were transitioned to palliative care; of those, 14% presented with an advanced directive, and 28% received a palliative care consultation (JAMA Surg. 2017;152[2]:183-90. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3970).

While palliative care services are increasing in hospitals, accounting for 4% of annual hospital admissions in 2012 according to the study, they are not implemented consistently. “Many teams from various specialties care for patients at end of life; however, we still do not know what prompts end-of-life discussions,” Dr. Wilson said. “There is still no consensus on when to involve palliative services in the care of critically ill patients.”

While the decision to advise a consultation is “variable and physician dependent,” the type of treatment required may help identify when consultations are appropriate.

Of the 14 patients who did not choose comfort care, 11 (79%) required CPR. Additionally, all had to be taken to the operating room and required mechanical ventilation.

Of 81 patients who chose palliative care, 31 did so despite potential medical options. These patients were older – average age, 77 years, as compared with 68 years for patients who did not choose comfort care – with 8 of the 31 (26%) presenting an advanced directive, compared with only 7 of 83 patients (8%) for those who did not receive palliative care.

Dr. Wilson and his colleagues found that patients who chose palliative care were more likely to have received a palliative care consultation, as well: 10 of 31 patients who chose comfort care received a consultation, as opposed to 1 of 83 who chose comfort care but did not receive a consultation.

The nature of the vascular surgery service calls for early efforts to gather information regarding patients’ views on end-of-life care, Dr. Wilson said, noting that 73% of patients studied were admitted emergently and 87% underwent surgery, leaving little time for patients to express their wishes.

“Because the events associated with withdrawal of care are often not anticipated, we argue that all vascular surgical patients should have an advance directive, and perhaps, those at particular high risk should have a preoperative palliative care consultation,” Dr. Wilson wrote.

Limitations to the study included the data abstraction, which was performed by a single unblinded physician. Researchers also gathered patients’ reasons for transitioning to comfort care retrospectively.

The low rate of palliative care consultations found in this study mirrors my own experience, as does the feeling of urgency to shed more light on the issue. The biggest hurdle surgeons face when it comes to palliative care consultations is that, in their minds, seeking these meetings is associated with immediate death care. Many surgeons are shy about bringing palliative care specialists on board because approaching families can be daunting.

Family members who do not know enough about comfort care can be upset by the idea. Addressing this misunderstanding is crucial. Consultations are not just conversations about hospice care but can be emotional and spiritual experiences that prepare both the family and the patient for alternative options when surgical intervention cannot guarantee a good quality of life. I would encourage surgeons to be more proactive and less defensive about comfort care . Luckily, understanding the importance of this issue among professionals is growing.

When I approach these situations, it’s important for me to have a full understanding of what families and patients usually expect. Decisions should not be based on how bad things are now but on the future. What was the patient’s last year like? What is the best-case scenario for moving forward on a proposed intervention? What will the patient’s quality of life be? Answering these questions helps the patient understand his or her situation, without diminishing a surgeon’s ability. If you are honest, the family will usually come to the conclusion that they do not want to subject the patient to ultimately unnecessary treatment.

Palliative care services help patients and their families deal with pain beyond the physical symptoms. Dealing with pain, depression, or delirium is only a part of comfort care – coping with a sense of hopelessness, family disruption, or feelings of guilt also can be a part and, significantly, a part that surgeons are not trained to diagnose or treat.

With more than 70 surgeons certified in hospice care and a growing number of fellowships in palliative care, I am extremely optimistic in the progress we have made and will continue to make.

Geoffrey Dunn, MD, FACS, is the medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at UPMC Hamot Medical Center, Erie, Penn. He currently is Community Editor for the Pain and Palliative Care Community for the ACS’s web portal.

The low rate of palliative care consultations found in this study mirrors my own experience, as does the feeling of urgency to shed more light on the issue. The biggest hurdle surgeons face when it comes to palliative care consultations is that, in their minds, seeking these meetings is associated with immediate death care. Many surgeons are shy about bringing palliative care specialists on board because approaching families can be daunting.

Family members who do not know enough about comfort care can be upset by the idea. Addressing this misunderstanding is crucial. Consultations are not just conversations about hospice care but can be emotional and spiritual experiences that prepare both the family and the patient for alternative options when surgical intervention cannot guarantee a good quality of life. I would encourage surgeons to be more proactive and less defensive about comfort care . Luckily, understanding the importance of this issue among professionals is growing.

When I approach these situations, it’s important for me to have a full understanding of what families and patients usually expect. Decisions should not be based on how bad things are now but on the future. What was the patient’s last year like? What is the best-case scenario for moving forward on a proposed intervention? What will the patient’s quality of life be? Answering these questions helps the patient understand his or her situation, without diminishing a surgeon’s ability. If you are honest, the family will usually come to the conclusion that they do not want to subject the patient to ultimately unnecessary treatment.

Palliative care services help patients and their families deal with pain beyond the physical symptoms. Dealing with pain, depression, or delirium is only a part of comfort care – coping with a sense of hopelessness, family disruption, or feelings of guilt also can be a part and, significantly, a part that surgeons are not trained to diagnose or treat.

With more than 70 surgeons certified in hospice care and a growing number of fellowships in palliative care, I am extremely optimistic in the progress we have made and will continue to make.

Geoffrey Dunn, MD, FACS, is the medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at UPMC Hamot Medical Center, Erie, Penn. He currently is Community Editor for the Pain and Palliative Care Community for the ACS’s web portal.

The low rate of palliative care consultations found in this study mirrors my own experience, as does the feeling of urgency to shed more light on the issue. The biggest hurdle surgeons face when it comes to palliative care consultations is that, in their minds, seeking these meetings is associated with immediate death care. Many surgeons are shy about bringing palliative care specialists on board because approaching families can be daunting.

Family members who do not know enough about comfort care can be upset by the idea. Addressing this misunderstanding is crucial. Consultations are not just conversations about hospice care but can be emotional and spiritual experiences that prepare both the family and the patient for alternative options when surgical intervention cannot guarantee a good quality of life. I would encourage surgeons to be more proactive and less defensive about comfort care . Luckily, understanding the importance of this issue among professionals is growing.

When I approach these situations, it’s important for me to have a full understanding of what families and patients usually expect. Decisions should not be based on how bad things are now but on the future. What was the patient’s last year like? What is the best-case scenario for moving forward on a proposed intervention? What will the patient’s quality of life be? Answering these questions helps the patient understand his or her situation, without diminishing a surgeon’s ability. If you are honest, the family will usually come to the conclusion that they do not want to subject the patient to ultimately unnecessary treatment.

Palliative care services help patients and their families deal with pain beyond the physical symptoms. Dealing with pain, depression, or delirium is only a part of comfort care – coping with a sense of hopelessness, family disruption, or feelings of guilt also can be a part and, significantly, a part that surgeons are not trained to diagnose or treat.

With more than 70 surgeons certified in hospice care and a growing number of fellowships in palliative care, I am extremely optimistic in the progress we have made and will continue to make.

Geoffrey Dunn, MD, FACS, is the medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at UPMC Hamot Medical Center, Erie, Penn. He currently is Community Editor for the Pain and Palliative Care Community for the ACS’s web portal.

Investment in advanced palliative care planning has the potential to improve the quality of care for vascular surgery patients, according to investigators from Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Dale G. Wilson, MD, and his colleagues performed a retrospective review of electronic medical records for 111 patients, who died while on the vascular surgery service at the OHSU Hospital during 2005-2014.

Almost three-quarters (73%) of patients were transitioned to palliative care; of those, 14% presented with an advanced directive, and 28% received a palliative care consultation (JAMA Surg. 2017;152[2]:183-90. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3970).

While palliative care services are increasing in hospitals, accounting for 4% of annual hospital admissions in 2012 according to the study, they are not implemented consistently. “Many teams from various specialties care for patients at end of life; however, we still do not know what prompts end-of-life discussions,” Dr. Wilson said. “There is still no consensus on when to involve palliative services in the care of critically ill patients.”

While the decision to advise a consultation is “variable and physician dependent,” the type of treatment required may help identify when consultations are appropriate.

Of the 14 patients who did not choose comfort care, 11 (79%) required CPR. Additionally, all had to be taken to the operating room and required mechanical ventilation.

Of 81 patients who chose palliative care, 31 did so despite potential medical options. These patients were older – average age, 77 years, as compared with 68 years for patients who did not choose comfort care – with 8 of the 31 (26%) presenting an advanced directive, compared with only 7 of 83 patients (8%) for those who did not receive palliative care.

Dr. Wilson and his colleagues found that patients who chose palliative care were more likely to have received a palliative care consultation, as well: 10 of 31 patients who chose comfort care received a consultation, as opposed to 1 of 83 who chose comfort care but did not receive a consultation.

The nature of the vascular surgery service calls for early efforts to gather information regarding patients’ views on end-of-life care, Dr. Wilson said, noting that 73% of patients studied were admitted emergently and 87% underwent surgery, leaving little time for patients to express their wishes.

“Because the events associated with withdrawal of care are often not anticipated, we argue that all vascular surgical patients should have an advance directive, and perhaps, those at particular high risk should have a preoperative palliative care consultation,” Dr. Wilson wrote.

Limitations to the study included the data abstraction, which was performed by a single unblinded physician. Researchers also gathered patients’ reasons for transitioning to comfort care retrospectively.

Investment in advanced palliative care planning has the potential to improve the quality of care for vascular surgery patients, according to investigators from Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Dale G. Wilson, MD, and his colleagues performed a retrospective review of electronic medical records for 111 patients, who died while on the vascular surgery service at the OHSU Hospital during 2005-2014.

Almost three-quarters (73%) of patients were transitioned to palliative care; of those, 14% presented with an advanced directive, and 28% received a palliative care consultation (JAMA Surg. 2017;152[2]:183-90. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3970).

While palliative care services are increasing in hospitals, accounting for 4% of annual hospital admissions in 2012 according to the study, they are not implemented consistently. “Many teams from various specialties care for patients at end of life; however, we still do not know what prompts end-of-life discussions,” Dr. Wilson said. “There is still no consensus on when to involve palliative services in the care of critically ill patients.”

While the decision to advise a consultation is “variable and physician dependent,” the type of treatment required may help identify when consultations are appropriate.

Of the 14 patients who did not choose comfort care, 11 (79%) required CPR. Additionally, all had to be taken to the operating room and required mechanical ventilation.

Of 81 patients who chose palliative care, 31 did so despite potential medical options. These patients were older – average age, 77 years, as compared with 68 years for patients who did not choose comfort care – with 8 of the 31 (26%) presenting an advanced directive, compared with only 7 of 83 patients (8%) for those who did not receive palliative care.

Dr. Wilson and his colleagues found that patients who chose palliative care were more likely to have received a palliative care consultation, as well: 10 of 31 patients who chose comfort care received a consultation, as opposed to 1 of 83 who chose comfort care but did not receive a consultation.

The nature of the vascular surgery service calls for early efforts to gather information regarding patients’ views on end-of-life care, Dr. Wilson said, noting that 73% of patients studied were admitted emergently and 87% underwent surgery, leaving little time for patients to express their wishes.

“Because the events associated with withdrawal of care are often not anticipated, we argue that all vascular surgical patients should have an advance directive, and perhaps, those at particular high risk should have a preoperative palliative care consultation,” Dr. Wilson wrote.

Limitations to the study included the data abstraction, which was performed by a single unblinded physician. Researchers also gathered patients’ reasons for transitioning to comfort care retrospectively.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of the 111 patients studied, 81 died on palliative care, but only 15 presented an advanced directive.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of the records of patients aged 18-99 years who died in the vascular surgery service at Oregon Health and Science University Hospital from 2005-2014.

Disclosures: The authors reported no financial disclosures.

How and when umbilical cord gas analysis can justify your obstetric management

Umbilical cord blood (cord) gas values can aid both in understanding the cause of an infant’s acidosis and in providing reassurance that acute acidosis or asphyxia is not responsible for a compromised infant with a low Apgar score. Together with other clinical measurements (including fetal heart rate [FHR] tracings, Apgar scores, newborn nucleated red cell counts, and neonatal imaging), cord gas analysis can be remarkably helpful in determining the cause for a depressed newborn. It can help us determine, for example, if infant compromise was a result of an asphyxial event, and we often can differentiate whether the event was acute, prolonged, or occurred prior to presentation in labor. We further can use cord gas values to assess whether a decision for operative intervention for nonreassuring fetal well-being was appropriate (see “Brain injury at birth: Cord gas values presented as evidence at trial”). In addition, cord gas analysis can complement methods for determining fetal acidosis changes during labor, enabling improved assessment of FHR tracings.1−3

At 40 weeks' gestation, a woman presented to the hospital because of decreased fetal movement. On arrival, an external fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitor showed nonreassuring tracings, evidenced by absent to minimal variability and subtle decelerations occurring at 10- to 15-minute intervals. The on-call ObGyn requested induction of labor with oxytocin, and a low-dose infusion (1 mU/min) was initiated. An internal FHR monitor was then placed and late decelerations were observed with the first 2 induced contractions. The oxytocin infusion was discontinued and the ObGyn performed an emergency cesarean delivery. The infant's Apgar scores were 1, 2, and 2 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. Cord samples were obtained and values from the umbilical artery were as follows: pH, 6.86; Pco2, 55 mm Hg; Po2, 6 mm Hg; and BDECF, 21.1 mmol/L. Values from the umbilical vein were: pH, 6.94; Pco2, 45 mm Hg; Po2, 17 mm Hg; and BDECF, 20.0 mmol/L. The infant was later diagnosed with a hypoxic brain injury resulting in cerebral palsy. At trial years later, the boy had cognitive and physical limitations and required 24-hour care.

The parents claimed that the ObGyn should have performed a cesarean delivery earlier when the external FHR monitor showed nonreassuring tracings.

The hospital and physician claimed that, while tracings were consistently nonreassuring, they were stable. They maintained that the child's brain damage was not due to a delivery delay, as the severe level of acidosis in both the umbilical artery and vein could not be a result of the few heart rate decelerations during the 2-hour period of monitoring prior to delivery. They argued that the clinical picture indicated a pre-hospital hypoxic event associated with decreased fetal movement.

A defense verdict was returned.

Case assessment

Cord gas results, together with other measures (eg, infant nucleated red blood cells, brain imaging) can aid the ObGyn in medicolegal cases. However, they are not always protective of adverse judgment.

I recommend checking umbilical cord blood gas values on all operative vaginal deliveries, cesarean deliveries for fetal concern, abnormal FHR patterns, clinical chorioamnionitis, multifetal gestations, premature deliveries, and all infants with low Apgar scores at 1 or 5 minutes. If you think you may need a cord gas analysis, go ahead and obtain it. Cord gas analysis often will aid in justifying your management or provide insight into the infant’s status.

Controversy remains as to the benefit of universal cord gas analysis. Assuming a variable cost of $15 for 2 (artery and vein) blood gas samples per neonate,4 the annual cost in the United States would be approximately $60 million. This would likely be cost effective as a result of medicolegal and educational benefits as well as potential improvements in perinatal outcome5 and reductions in special care nursery admissions.4

CASE 1: A newborn with unexpected acidosis

A 29-year-old woman (G2P1) at 38 weeks’ gestation was admitted to the hospital following an office visit during which oligohydramnios (amniotic fluid index, 3.5 cm) was found. The patient had a history of a prior cesarean delivery for failure to progress, and she desired a repeat cesarean delivery. Fetal monitoring revealed a heart rate of 140 beats per minute with moderate variability and uterine contractions every 3 to 5 minutes associated with moderate variable decelerations. A decision was made to proceed with the surgery. Blood samples were drawn for laboratory analysis, monitoring was discontinued, and the patient was taken to the operating room. An epidural anesthetic was placed and the cesarean delivery proceeded.

On uterine incision, there was no evidence of abruption or uterine rupture, but thick meconium-stained amniotic fluid was observed. A depressed infant was delivered, the umbilical cord clamped, and the infant handed to the pediatric team. Cord samples were obtained and values from the umbilical artery were as follows: pH, 6.80; P

What happened?

Read how to use cord gas values in practice

Using cord gas values in practice

Before analyzing the circumstances in Case 1,it is important to consider several key questions, including:

- What are the normal levels of cord pH, O2, CO2, and base deficit (BD)?

- How does cord gas indicate what happened during labor?

- What are the preventable errors in cord gas sampling or interpretation?

For a review of fetal cord gas physiology, see “Physiology of fetal cord gases: The basics”.

A review of basic fetal cord gas physiology will assist in understanding how values are interpreted.

Umbilical cord O2 and CO2

Fetal cord gas values result from the rapid transfer of gases and the slow clearance of acid across the placenta. Approximately 10% of maternal blood flow supplies the uteroplacental circulation, with the near-term placenta receiving approximately 70% of the uterine blood flow.1 Of the oxygen delivered, a surprising 50% provides for placental metabolism and 50% for the fetus. On the fetal side, 40% of fetal cardiac output supplies the umbilical circulation. Oxygen and carbon dioxide pass readily across the placental layers; exchange is limited by the amount of blood flow on both the maternal and the fetal side (flow limited). In the human placenta, maternal blood and fetal blood effectively travel in the same direction (concurrent exchange); thus, umbilical vein O2 and CO2 equilibrate with that in the maternal uterine vein.

Most of the O2 in fetal blood is carried by hemoglobin. Because of the markedly greater affinity of fetal hemoglobin for O2, the saturation curve is shifted to the left, resulting in increased hemoglobin saturation at the relatively low levels of fetal Po2. This greater affinity for oxygen results from the unique fetal hemoglobin gamma (γ) subunit, as compared with the adult beta (ß) subunit. Fetal hemoglobin has a reduced interaction with 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate, which itself decreases the affinity of adult hemoglobin for oxygen.

The majority of CO2 (85%) is carried as part of the bicarbonate buffer system. Fetal CO2 is converted into carbonic acid (H2CO3) in the red cell and dissociates into hydrogen (H+) and bicarbonate (HCO3−) ions, which diffuse out of the cell. When fetal blood reaches the placenta, this process is reversed and CO2 diffuses across the placenta to the maternal circulation. The production of H+ ions from CO2 explains the development of respiratory acidosis from high Pco2. In contrast, anaerobic metabolism, which produces lactic acid, results in metabolic acidosis.

Difference between pH and BD

The pH is calculated as the inverse log of the H+ ion concentration; thus, the pH falls as the H+ ion concentration exponentially increases, whether due to respiratory or metabolic acidosis. To quantify the more important metabolic acidosis, we use BD, which is a measure of how much of bicarbonate buffer base has been used by (lactic) acid. The BD and the base excess (BE) may be used interchangeably, with BE representing a negative number. Although BD represents the metabolic component of acidosis, a correction may be required to account for high levels of fetal Pco2 (see Case 1). In this situation, a more accurate measure is BD extracellular fluid (BDECF).

Why not just use pH? There are 2 major limitations to using pH as a measure of fetal or newborn acidosis. First, pH may be influenced by both respiratory and metabolic alterations, although only metabolic acidosis is associated with fetal neurologic injury.2 Furthermore, as pH is a log function, it does not change linearly with the amount of acid produced. In contrast to pH, BD is a measure of metabolic acidosis and changes in direct proportion to fetal acid production.

What about lactate? Measurements of lactate may also be included in blood gas analyses. Under hypoxic conditions, excess pyruvate is converted into lactate and released from the cell along with H+, resulting in acidosis. However, levels of umbilical cord lactate associated with neonatal hypoxic injury have not been established to the same degree as have pH or BD. Nevertheless, lactate has been measured in fetal scalp blood samples and offers the potential as a marker of fetal hypoxemia and acidosis.3

References

- Assali NS. Dynamics of the uteroplacental circulation in health and disease. Am J Perinatol. 1989;6(2):105-109.

- Low JA, Panagiotopoulos C, Derrick EJ. Newborn complications after intrapartum asphyxia with metabolic acidosis in the term fetus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(4):1081-1087.

- Mancho JP, Gamboa SM, Gimenez OR, Esteras RC, Solanilla BR, Mateo SC. Diagnostic accuracy of fetal scalp lactate for intrapartum acidosis compared with scalp pH [published online ahead of print October 8, 2016]. J Perinatal Med. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2016-004.

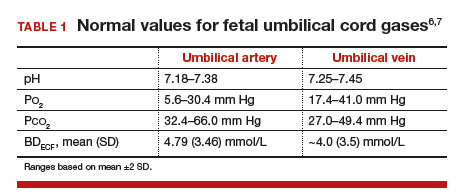

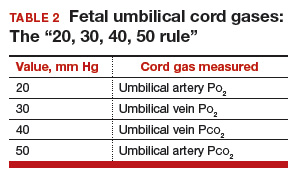

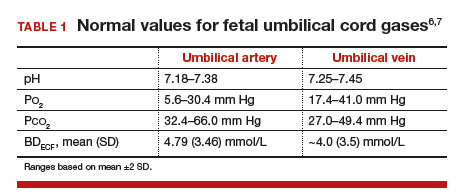

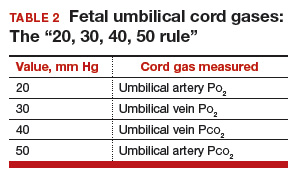

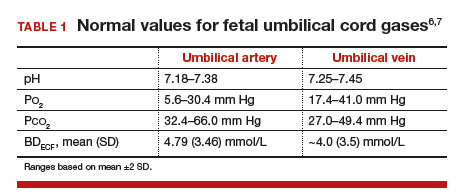

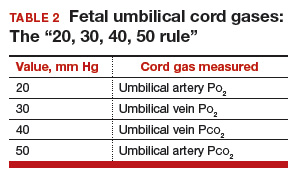

Normal values: The “20, 30, 40, 50 rule”

Among the values reported for umbilical blood gas, the pH, P

I recommend using the “20, 30, 40, 50 rule” as a simple tool for remembering normal umbilical artery and vein P

- P

o 2 values are lower than Pco 2 values; thus, the 20 and 30 represent Po 2 values - as fetal umbilical artery P

o 2 is lower than umbilical vein Po 2, 20 mm Hg represents the umbilical artery and 30 mm Hg represents the vein - P

co 2 values are higher in the umbilical artery than in the vein; thus, 50 mm Hg represents the umbilical artery and 40 mm Hg represents the umbilical vein.

Umbilical cord BD values change in relation to labor and FHR decelerations.8 Prior to labor, the normal fetus has a slight degree of acidosis (BD, 2 mmol/L). During the latent phase of labor, fetal BD typically does not change. With the increased frequency of contractions, BD may increase 1 mmol/L for every 3 to 6 hours during the active phase and up to 1 mmol/L per hour during the second stage, depending on FHR responses. Thus, following vaginal delivery the average umbilical artery BD is approximately 5 mmol/L and the umbilical vein BD is approximately 4 mmol/L. As lactate crosses the placenta slowly, BD values are typically only 1 mmol/L less in the umbilical vein than in the artery, unless there has been an obstruction to placental flow (see Case 1).

For pH, the umbilical artery value is always lower than that of the vein, a result of both the higher umbilical artery P

Possible causes of abnormal cord gas values

Because of the nearly fully saturated maternal hemoglobin under normal conditions, fetal arterial and venous P

In contrast, reduced fetal P

Effect of maternal oxygen administration on fetal oxygenation

Although maternal oxygen administration is commonly used during labor and delivery, controversy remains as to the benefit of oxygen supplementation.10 In a normal mother with oxygen saturation above 95%, the administration of oxygen will increase maternal arterial P

However, maternal oxygen supplementation may have marked benefit in cases in which maternal arterial P

How did the Case 1 circumstances lead to newborn acidosis?

Most noticeable in this case is the large difference in BD between the umbilical artery and vein and the high P

Whereas BD normally is only about 1 mmol/L greater in the umbilical artery versus in the vein, occasionally the arterial value is markedly greater than the vein value. This can occur when there is a cessation of blood flow through the placenta, as a result of complete umbilical cord obstruction, or when there is a uterine abruption. In these situations, the umbilical vein (which has not had blood flow) represents the fetal status prior to the occlusion event. In contrast, despite bradycardia, fetal heart pulsations mix blood within the umbilical artery and therefore the artery generally represents the fetal status at the time of birth.

In response to complete cord occlusion, fetal BD increases by approximately 1 mmol/L every 2 minutes. Consequently, an 8 mmol/L difference in BD between the umbilical artery and vein is consistent with a 16-minute period of umbilical occlusion or placental abruption. Also in response to complete umbilical cord occlusion, P

The umbilical vein BD is also elevated for early labor. This value suggests that repetitive, intermittent cord occlusions (evident on the initial fetal monitor tracing) likely resulted in this moderate acidosis prior to the complete cord occlusion in the final 16 minutes.

Thus, BD and P

Read more cases plus procedures, equipment for cord sampling

CASE 2: An infant with unusual umbilical artery values

An infant born via vacuum delivery for a prolonged second stage of labor had 1- and 5-minute Apgar scores of 8 and 9, respectively. Cord gas values were obtained, and analysis revealed that for the umbilical artery, the pH was 7.29; P

The resident asked, “How is the P

The curious Case 2 values suggest an air bubble

Although it is possible that the aberrant values in Case 2 could have resulted from switching the artery and vein samples, the pH is lower in the artery, and both the artery P

Related article:

Is neonatal injury more likely outside of a 30-minute decision-to-incision time interval for cesarean delivery?

CASE 3: A vigorous baby with significant acidosis

A baby with 1- and 5-minute Apgar scores of 9 and 9 was delivered by cesarean and remained vigorous. Umbilical cord analysis revealed an umbilical artery pH level of 7.15, with normal P

Was there a collection error in Case 3?

On occasion, a falsely low pH level and, thus, a falsely elevated BD may result from excessive heparin in the collection syringe. Heparin is acidotic and should be used only to coat the syringe. Although syringes in current use are often pre-heparinized, if one is drawing up heparin into the syringe, it should be coated and then fully expelled.

Umbilical cord sampling: Procedures and equipment

Many issues remain regarding the optimal storage of cord samples. Ideally, a doubly clamped section of the cord promptly should be sampled into glass syringes that can be placed on ice and rapidly measured for cord values.

Stability of umbilical cord samples within the cord is within 20 to 30 minutes. Delayed sampling of clamped cord sections generally has minimal effect on pH and P

Plastic syringes can introduce interference. Several studies have demonstrated that collection of samples in plastic may result in an increase in P

Use glass, and “ice” the sample if necessary. Although it has been suggested that placing samples on ice minimizes metabolism, the cooled plastic may in fact be more susceptible to oxygen diffusion. Thus, unless samples will be analyzed promptly, it is best to use glass syringes on ice.13,14

Related article:

Protecting the newborn brain—the final frontier in obstetric and neonatal care

What if the umbilical cord is torn?

Sometimes the umbilical cord is torn and discarded or cannot be accessed for other reasons. A sample can still be obtained, however, by aspirating the placental surface artery and vein vessels. Although there is some potential variance in pH, P

How do you obtain cord analysis when delaying cord clamping?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) now advises delayed cord clamping in term and preterm deliveries, which raises the question of how you obtain a blood sample in this setting. Importantly, ACOG recommends delayed cord clamping only in vigorous infants,16 whereas potentially compromised infants should be transferred rapidly for newborn care. Although several studies have demonstrated some variation in cord gas values with delayed cord clamping,17–21 clamping after pulsation has ceased or after the recommended 30 to 60 seconds following birth results in minimal change in BD values. Thus, do not hesitate to perform delayed cord clamping in vigorous infants.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Ross MG, Gala R. Use of umbilical artery base excess: algorithm for the timing of hypoxic injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(1):1–9.

- Uccella S, Cromi A, Colombo G, et al. Prediction of fetal base excess values at birth using an algorithm to interpret fetal heart rate tracings: a retrospective validation. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1657–1664.

- Uccella S, Cromi A, Colombo GF, et al. Interobserver reliability to interpret intrapartum electronic fetal heart rate monitoring: does a standardized algorithm improve agreement among clinicians? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35(3):241–245.

- White CR, Doherty DA, Cannon JW, Kohan R, Newnham JP, Pennell CE. Cost effectiveness of universal umbilical cord blood gas and lactate analysis in a tertiary level maternity unit. J Perinat Med. 2016;44(5):573–584.

- White CR, Doherty DA, Henderson JJ, Kohan R, Newnham JP, Pennell CE. Benefits of introducing universal umbilical cord blood gas and lactate analysis into an obstetric unit. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(4):318–328.

- Yeomans ER, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC III, Strickland DM. Umbilical cord pH, Pco2, and bicarbonate following uncomplicated term vaginal deliveries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(6):798–800.

- Wiberg N, Källén K, Olofsson P. Base deficit estimation in umbilical cord blood is influenced by gestational age, choice of fetal fluid compartment, and algorithm for calculation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(6):1651–1656.

- Ross MG, Gala R. Use of umbilical artery base excess: algorithm for the timing of hypoxic injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(1):1–9.

- Executive summary: Neonatal encephalopathy and neurologic outcome, second edition. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):896-901.

- Hamel MS, Anderson BL, Rouse DJ. Oxygen for intrauterine resuscitation: of unproved benefit and potentially harmful. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(2):124–127.

- Owen P, Farrell TA, Steyn W. Umbilical cord blood gas analysis; a comparison of two simple methods of sample storage. Early Hum Dev. 1995;42(1):67–71.

- Armstrong L, Stenson B. Effect of delayed sampling on umbilical cord arterial and venous lactate and blood gases in clamped and unclamped vessels. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91(5):F342–F345.

- White CR, Mok T, Doherty DA, Henderson JJ, Newnham JP, Pennell CE. The effect of time, temperature and storage device on umbilical cord blood gas and lactate measurement: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(6):587–594.

- Knowles TP, Mullin RA, Hunter JA, Douce FH. Effects of syringe material, sample storage time, and temperature on blood gases and oxygen saturation in arterialized human blood samples. Respir Care. 2006;51(7):732–736.

- Nodwell A, Carmichael L, Ross M, Richardson B. Placental compared with umbilical cord blood to assess fetal blood gas and acid-base status. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):129–138.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 684. Delayed umbilical cord clamping after birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(1):e5–e10.

- De Paco C, Florido J, Garrido MC, Prados S, Navarrete L. Umbilical cord blood acid-base and gas analysis after early versus delayed cord clamping in neonates at term. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(5):1011–1014.

- Valero J, Desantes D, Perales-Puchalt A, Rubio J, Diago Almela VJ, Perales A. Effect of delayed umbilical cord clamping on blood gas analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;162(1): 21–23.

- Andersson O, Hellström-Westas L, Andersson D, Clausen J, Domellöf M. Effects of delayed compared with early umbilical cord clamping on maternal postpartum hemorrhage and cord blood gas sampling: a randomized trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(5):567–574.

- Wiberg N, Källén K, Olofsson P. Delayed umbilical cord clamping at birth has effects on arterial and venous blood gases and lactate concentrations. BJOG. 2008;115(6):697–703.

- Mokarami P, Wiberg N, Olofsson P. Hidden acidosis: an explanation of acid-base and lactate changes occurring in umbilical cord blood after delayed sampling. BJOG. 2013;120(8):996–1002.

Umbilical cord blood (cord) gas values can aid both in understanding the cause of an infant’s acidosis and in providing reassurance that acute acidosis or asphyxia is not responsible for a compromised infant with a low Apgar score. Together with other clinical measurements (including fetal heart rate [FHR] tracings, Apgar scores, newborn nucleated red cell counts, and neonatal imaging), cord gas analysis can be remarkably helpful in determining the cause for a depressed newborn. It can help us determine, for example, if infant compromise was a result of an asphyxial event, and we often can differentiate whether the event was acute, prolonged, or occurred prior to presentation in labor. We further can use cord gas values to assess whether a decision for operative intervention for nonreassuring fetal well-being was appropriate (see “Brain injury at birth: Cord gas values presented as evidence at trial”). In addition, cord gas analysis can complement methods for determining fetal acidosis changes during labor, enabling improved assessment of FHR tracings.1−3

At 40 weeks' gestation, a woman presented to the hospital because of decreased fetal movement. On arrival, an external fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitor showed nonreassuring tracings, evidenced by absent to minimal variability and subtle decelerations occurring at 10- to 15-minute intervals. The on-call ObGyn requested induction of labor with oxytocin, and a low-dose infusion (1 mU/min) was initiated. An internal FHR monitor was then placed and late decelerations were observed with the first 2 induced contractions. The oxytocin infusion was discontinued and the ObGyn performed an emergency cesarean delivery. The infant's Apgar scores were 1, 2, and 2 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. Cord samples were obtained and values from the umbilical artery were as follows: pH, 6.86; Pco2, 55 mm Hg; Po2, 6 mm Hg; and BDECF, 21.1 mmol/L. Values from the umbilical vein were: pH, 6.94; Pco2, 45 mm Hg; Po2, 17 mm Hg; and BDECF, 20.0 mmol/L. The infant was later diagnosed with a hypoxic brain injury resulting in cerebral palsy. At trial years later, the boy had cognitive and physical limitations and required 24-hour care.

The parents claimed that the ObGyn should have performed a cesarean delivery earlier when the external FHR monitor showed nonreassuring tracings.

The hospital and physician claimed that, while tracings were consistently nonreassuring, they were stable. They maintained that the child's brain damage was not due to a delivery delay, as the severe level of acidosis in both the umbilical artery and vein could not be a result of the few heart rate decelerations during the 2-hour period of monitoring prior to delivery. They argued that the clinical picture indicated a pre-hospital hypoxic event associated with decreased fetal movement.

A defense verdict was returned.

Case assessment

Cord gas results, together with other measures (eg, infant nucleated red blood cells, brain imaging) can aid the ObGyn in medicolegal cases. However, they are not always protective of adverse judgment.

I recommend checking umbilical cord blood gas values on all operative vaginal deliveries, cesarean deliveries for fetal concern, abnormal FHR patterns, clinical chorioamnionitis, multifetal gestations, premature deliveries, and all infants with low Apgar scores at 1 or 5 minutes. If you think you may need a cord gas analysis, go ahead and obtain it. Cord gas analysis often will aid in justifying your management or provide insight into the infant’s status.

Controversy remains as to the benefit of universal cord gas analysis. Assuming a variable cost of $15 for 2 (artery and vein) blood gas samples per neonate,4 the annual cost in the United States would be approximately $60 million. This would likely be cost effective as a result of medicolegal and educational benefits as well as potential improvements in perinatal outcome5 and reductions in special care nursery admissions.4

CASE 1: A newborn with unexpected acidosis

A 29-year-old woman (G2P1) at 38 weeks’ gestation was admitted to the hospital following an office visit during which oligohydramnios (amniotic fluid index, 3.5 cm) was found. The patient had a history of a prior cesarean delivery for failure to progress, and she desired a repeat cesarean delivery. Fetal monitoring revealed a heart rate of 140 beats per minute with moderate variability and uterine contractions every 3 to 5 minutes associated with moderate variable decelerations. A decision was made to proceed with the surgery. Blood samples were drawn for laboratory analysis, monitoring was discontinued, and the patient was taken to the operating room. An epidural anesthetic was placed and the cesarean delivery proceeded.

On uterine incision, there was no evidence of abruption or uterine rupture, but thick meconium-stained amniotic fluid was observed. A depressed infant was delivered, the umbilical cord clamped, and the infant handed to the pediatric team. Cord samples were obtained and values from the umbilical artery were as follows: pH, 6.80; P

What happened?

Read how to use cord gas values in practice

Using cord gas values in practice

Before analyzing the circumstances in Case 1,it is important to consider several key questions, including:

- What are the normal levels of cord pH, O2, CO2, and base deficit (BD)?

- How does cord gas indicate what happened during labor?

- What are the preventable errors in cord gas sampling or interpretation?

For a review of fetal cord gas physiology, see “Physiology of fetal cord gases: The basics”.

A review of basic fetal cord gas physiology will assist in understanding how values are interpreted.

Umbilical cord O2 and CO2

Fetal cord gas values result from the rapid transfer of gases and the slow clearance of acid across the placenta. Approximately 10% of maternal blood flow supplies the uteroplacental circulation, with the near-term placenta receiving approximately 70% of the uterine blood flow.1 Of the oxygen delivered, a surprising 50% provides for placental metabolism and 50% for the fetus. On the fetal side, 40% of fetal cardiac output supplies the umbilical circulation. Oxygen and carbon dioxide pass readily across the placental layers; exchange is limited by the amount of blood flow on both the maternal and the fetal side (flow limited). In the human placenta, maternal blood and fetal blood effectively travel in the same direction (concurrent exchange); thus, umbilical vein O2 and CO2 equilibrate with that in the maternal uterine vein.

Most of the O2 in fetal blood is carried by hemoglobin. Because of the markedly greater affinity of fetal hemoglobin for O2, the saturation curve is shifted to the left, resulting in increased hemoglobin saturation at the relatively low levels of fetal Po2. This greater affinity for oxygen results from the unique fetal hemoglobin gamma (γ) subunit, as compared with the adult beta (ß) subunit. Fetal hemoglobin has a reduced interaction with 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate, which itself decreases the affinity of adult hemoglobin for oxygen.

The majority of CO2 (85%) is carried as part of the bicarbonate buffer system. Fetal CO2 is converted into carbonic acid (H2CO3) in the red cell and dissociates into hydrogen (H+) and bicarbonate (HCO3−) ions, which diffuse out of the cell. When fetal blood reaches the placenta, this process is reversed and CO2 diffuses across the placenta to the maternal circulation. The production of H+ ions from CO2 explains the development of respiratory acidosis from high Pco2. In contrast, anaerobic metabolism, which produces lactic acid, results in metabolic acidosis.

Difference between pH and BD

The pH is calculated as the inverse log of the H+ ion concentration; thus, the pH falls as the H+ ion concentration exponentially increases, whether due to respiratory or metabolic acidosis. To quantify the more important metabolic acidosis, we use BD, which is a measure of how much of bicarbonate buffer base has been used by (lactic) acid. The BD and the base excess (BE) may be used interchangeably, with BE representing a negative number. Although BD represents the metabolic component of acidosis, a correction may be required to account for high levels of fetal Pco2 (see Case 1). In this situation, a more accurate measure is BD extracellular fluid (BDECF).

Why not just use pH? There are 2 major limitations to using pH as a measure of fetal or newborn acidosis. First, pH may be influenced by both respiratory and metabolic alterations, although only metabolic acidosis is associated with fetal neurologic injury.2 Furthermore, as pH is a log function, it does not change linearly with the amount of acid produced. In contrast to pH, BD is a measure of metabolic acidosis and changes in direct proportion to fetal acid production.

What about lactate? Measurements of lactate may also be included in blood gas analyses. Under hypoxic conditions, excess pyruvate is converted into lactate and released from the cell along with H+, resulting in acidosis. However, levels of umbilical cord lactate associated with neonatal hypoxic injury have not been established to the same degree as have pH or BD. Nevertheless, lactate has been measured in fetal scalp blood samples and offers the potential as a marker of fetal hypoxemia and acidosis.3

References

- Assali NS. Dynamics of the uteroplacental circulation in health and disease. Am J Perinatol. 1989;6(2):105-109.

- Low JA, Panagiotopoulos C, Derrick EJ. Newborn complications after intrapartum asphyxia with metabolic acidosis in the term fetus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(4):1081-1087.

- Mancho JP, Gamboa SM, Gimenez OR, Esteras RC, Solanilla BR, Mateo SC. Diagnostic accuracy of fetal scalp lactate for intrapartum acidosis compared with scalp pH [published online ahead of print October 8, 2016]. J Perinatal Med. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2016-004.

Normal values: The “20, 30, 40, 50 rule”

Among the values reported for umbilical blood gas, the pH, P

I recommend using the “20, 30, 40, 50 rule” as a simple tool for remembering normal umbilical artery and vein P

- P

o 2 values are lower than Pco 2 values; thus, the 20 and 30 represent Po 2 values - as fetal umbilical artery P

o 2 is lower than umbilical vein Po 2, 20 mm Hg represents the umbilical artery and 30 mm Hg represents the vein - P

co 2 values are higher in the umbilical artery than in the vein; thus, 50 mm Hg represents the umbilical artery and 40 mm Hg represents the umbilical vein.

Umbilical cord BD values change in relation to labor and FHR decelerations.8 Prior to labor, the normal fetus has a slight degree of acidosis (BD, 2 mmol/L). During the latent phase of labor, fetal BD typically does not change. With the increased frequency of contractions, BD may increase 1 mmol/L for every 3 to 6 hours during the active phase and up to 1 mmol/L per hour during the second stage, depending on FHR responses. Thus, following vaginal delivery the average umbilical artery BD is approximately 5 mmol/L and the umbilical vein BD is approximately 4 mmol/L. As lactate crosses the placenta slowly, BD values are typically only 1 mmol/L less in the umbilical vein than in the artery, unless there has been an obstruction to placental flow (see Case 1).

For pH, the umbilical artery value is always lower than that of the vein, a result of both the higher umbilical artery P

Possible causes of abnormal cord gas values

Because of the nearly fully saturated maternal hemoglobin under normal conditions, fetal arterial and venous P

In contrast, reduced fetal P

Effect of maternal oxygen administration on fetal oxygenation

Although maternal oxygen administration is commonly used during labor and delivery, controversy remains as to the benefit of oxygen supplementation.10 In a normal mother with oxygen saturation above 95%, the administration of oxygen will increase maternal arterial P

However, maternal oxygen supplementation may have marked benefit in cases in which maternal arterial P

How did the Case 1 circumstances lead to newborn acidosis?

Most noticeable in this case is the large difference in BD between the umbilical artery and vein and the high P

Whereas BD normally is only about 1 mmol/L greater in the umbilical artery versus in the vein, occasionally the arterial value is markedly greater than the vein value. This can occur when there is a cessation of blood flow through the placenta, as a result of complete umbilical cord obstruction, or when there is a uterine abruption. In these situations, the umbilical vein (which has not had blood flow) represents the fetal status prior to the occlusion event. In contrast, despite bradycardia, fetal heart pulsations mix blood within the umbilical artery and therefore the artery generally represents the fetal status at the time of birth.

In response to complete cord occlusion, fetal BD increases by approximately 1 mmol/L every 2 minutes. Consequently, an 8 mmol/L difference in BD between the umbilical artery and vein is consistent with a 16-minute period of umbilical occlusion or placental abruption. Also in response to complete umbilical cord occlusion, P

The umbilical vein BD is also elevated for early labor. This value suggests that repetitive, intermittent cord occlusions (evident on the initial fetal monitor tracing) likely resulted in this moderate acidosis prior to the complete cord occlusion in the final 16 minutes.

Thus, BD and P

Read more cases plus procedures, equipment for cord sampling

CASE 2: An infant with unusual umbilical artery values

An infant born via vacuum delivery for a prolonged second stage of labor had 1- and 5-minute Apgar scores of 8 and 9, respectively. Cord gas values were obtained, and analysis revealed that for the umbilical artery, the pH was 7.29; P

The resident asked, “How is the P