User login

Prognostic tool may allow tailored therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma

A newly developed “robust and inexpensive” prognostic tool, the Childhood Hodgkin International Prognostic Score (CHIPS), may allow better tailoring of therapy at the time of diagnosis for children and adolescents who have intermediate-risk Hodgkin lymphoma.

Researchers in the Children’s Oncology Group first assessed 562 patients receiving uniform standard treatment to identify which risk factors present at diagnosis best predicted response to therapy, and used them to develop the prognostic score. They considered such factors as patient age, the number of involved sites, hemoglobin level, albumin level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, the presence or absence of a large mediastinal mass, nodal involvement, the total bulk of disease, and the presence or absence of B symptoms (fever, weight loss, and/or night sweats). The final CHIPS prognostic tool included four predictors of poor event-free survival that are easily ascertained at diagnosis: stage IV disease, a large mediastinal mass (one with a tumor to thoracic diameter ratio over 0.33), the presence of fever, and hypoalbuminemia (a level of less than 3.5 g/dL).

The investigators then confirmed the accuracy of that score in a validation cohort of 541 patients from the United States, Canada, Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, and Israel. All the study participants received four cycles of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, and etoposide (ABVE) with prednisone and cyclophosphamide (PC), followed by involved-field radiation therapy, said Cindy L. Schwartz, MD, of the division of pediatrics, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and her associates.

Patients who had low a CHIPS of 0 or 1 had excellent 4-year event-free survival (93% and 89%, respectively), while patients with a high CHIPS of 2 or 3 had poorer 4-year event-free survival (78% and 69%, respectively). These findings remained consistent across all subgroups of patients, regardless of whether the tumors had nodular sclerosis histology or mixed cellular histology (Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017 Apr;64[4]).

The study results suggest that patients with CHIPS 2 or 3 could be considered for high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma treatment such as higher-dose cyclophosphamide or the addition of brentuximab vedotin, while those with a CHIPS 0 or 1 could be considered for less aggressive treatment such as foregoing or reducing radiation therapy, Dr. Schwartz and her associates said.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to the Children’s Oncology Group. Dr. Schwartz and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A newly developed “robust and inexpensive” prognostic tool, the Childhood Hodgkin International Prognostic Score (CHIPS), may allow better tailoring of therapy at the time of diagnosis for children and adolescents who have intermediate-risk Hodgkin lymphoma.

Researchers in the Children’s Oncology Group first assessed 562 patients receiving uniform standard treatment to identify which risk factors present at diagnosis best predicted response to therapy, and used them to develop the prognostic score. They considered such factors as patient age, the number of involved sites, hemoglobin level, albumin level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, the presence or absence of a large mediastinal mass, nodal involvement, the total bulk of disease, and the presence or absence of B symptoms (fever, weight loss, and/or night sweats). The final CHIPS prognostic tool included four predictors of poor event-free survival that are easily ascertained at diagnosis: stage IV disease, a large mediastinal mass (one with a tumor to thoracic diameter ratio over 0.33), the presence of fever, and hypoalbuminemia (a level of less than 3.5 g/dL).

The investigators then confirmed the accuracy of that score in a validation cohort of 541 patients from the United States, Canada, Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, and Israel. All the study participants received four cycles of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, and etoposide (ABVE) with prednisone and cyclophosphamide (PC), followed by involved-field radiation therapy, said Cindy L. Schwartz, MD, of the division of pediatrics, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and her associates.

Patients who had low a CHIPS of 0 or 1 had excellent 4-year event-free survival (93% and 89%, respectively), while patients with a high CHIPS of 2 or 3 had poorer 4-year event-free survival (78% and 69%, respectively). These findings remained consistent across all subgroups of patients, regardless of whether the tumors had nodular sclerosis histology or mixed cellular histology (Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017 Apr;64[4]).

The study results suggest that patients with CHIPS 2 or 3 could be considered for high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma treatment such as higher-dose cyclophosphamide or the addition of brentuximab vedotin, while those with a CHIPS 0 or 1 could be considered for less aggressive treatment such as foregoing or reducing radiation therapy, Dr. Schwartz and her associates said.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to the Children’s Oncology Group. Dr. Schwartz and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A newly developed “robust and inexpensive” prognostic tool, the Childhood Hodgkin International Prognostic Score (CHIPS), may allow better tailoring of therapy at the time of diagnosis for children and adolescents who have intermediate-risk Hodgkin lymphoma.

Researchers in the Children’s Oncology Group first assessed 562 patients receiving uniform standard treatment to identify which risk factors present at diagnosis best predicted response to therapy, and used them to develop the prognostic score. They considered such factors as patient age, the number of involved sites, hemoglobin level, albumin level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, the presence or absence of a large mediastinal mass, nodal involvement, the total bulk of disease, and the presence or absence of B symptoms (fever, weight loss, and/or night sweats). The final CHIPS prognostic tool included four predictors of poor event-free survival that are easily ascertained at diagnosis: stage IV disease, a large mediastinal mass (one with a tumor to thoracic diameter ratio over 0.33), the presence of fever, and hypoalbuminemia (a level of less than 3.5 g/dL).

The investigators then confirmed the accuracy of that score in a validation cohort of 541 patients from the United States, Canada, Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, and Israel. All the study participants received four cycles of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, and etoposide (ABVE) with prednisone and cyclophosphamide (PC), followed by involved-field radiation therapy, said Cindy L. Schwartz, MD, of the division of pediatrics, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and her associates.

Patients who had low a CHIPS of 0 or 1 had excellent 4-year event-free survival (93% and 89%, respectively), while patients with a high CHIPS of 2 or 3 had poorer 4-year event-free survival (78% and 69%, respectively). These findings remained consistent across all subgroups of patients, regardless of whether the tumors had nodular sclerosis histology or mixed cellular histology (Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017 Apr;64[4]).

The study results suggest that patients with CHIPS 2 or 3 could be considered for high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma treatment such as higher-dose cyclophosphamide or the addition of brentuximab vedotin, while those with a CHIPS 0 or 1 could be considered for less aggressive treatment such as foregoing or reducing radiation therapy, Dr. Schwartz and her associates said.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to the Children’s Oncology Group. Dr. Schwartz and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Key clinical point: A newly developed “robust and inexpensive” prognostic tool, the Childhood Hodgkin International Prognostic Score, or CHIPS, may allow more tailored therapy for children and adolescents who have intermediate-risk Hodgkin lymphoma.

Major finding: Patients who had a low CHIPS of 0 or 1 had excellent 4-year event-free survival (93.1% and 88.5%, respectively), while patients with a high CHIPS of 2 or 3 had poorer 4-year event-free survival (77.6% and 69.2%).

Data source: A cohort study to develop (in 562 patients) and validate (in 541 patients) a score for predicting the response to standard treatment in pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to the Children’s Oncology Group. Dr. Schwartz and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - April 2017

BY JEREMY UDKOFF AND CATALINA MATIZ, MD

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG), a non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, is a common pediatric tumor that most commonly presents either at birth, in infants, or in young children – with the majority of cases occurring before 2 years. There is a male predominance with a 50% increased prevalence for solitary lesion disease and a 12 times higher prevalence in multilesion disease.1 Few lesions are concerning, and spontaneous regression of cutaneous lesions over the subsequent 1-5 years is a hallmark feature of JXG.2

Clinically, the JXGs are initially smooth, pinkish papules that may enlarge to 1-cm nodules and become yellowish in appearance before resolving to become atrophic macules or patches.2,3 JXGs are firm but rubbery and may become scaly and/or ulcerate as the lesion progresses.2 The JXGs most frequently occur superficially on the scalp and flexural areas of the upper extremities but infrequently present in the subcutaneous soft tissue, central nervous system, liver/spleen, eye/orbit, oropharynx, and muscle tissue.3,4 A well-described and concerning extracutaneous manifestations of JXG is ocular involvement and may be associated with bleeding into the anterior chamber of the eye. Despite this potentially disabling complication, screening for ocular involvement is recommended only in patients under age 2 years and in those with multiple skin lesions.5

The etiology of JXG is largely unknown. However, an association between neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and the development of JXG and other diseases such as juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, previously called juvenile chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, exists. It was thought that patients with NF1 and JXGs had a higher risk to develop juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.6 However, a recent study showed that JXG alone does not appear to confer an increased risk for developing malignancy in children with NF1.6,7

Differential diagnosis and work-up

The clinical differential diagnosis for JXG includes dermatofibromas, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, mastocytosis, Spitz nevus, hemangioendothelioma, and other xanthomas. Because of the concerning nature of these look-alikes, equivocal cases should be referred to a pediatric dermatologist.

Although, altered laboratory values may be seen with systemic JXG with solid organ involvement, there are no systemic tests that can be used to determine if a cutaneous lesion is JXG. Thus, biopsy is the gold standard diagnostic for confirmatory testing. As a histiocytic disorder, JXG will display various macrophages on histologic examination. Additionally, one may observe a dense dermal infiltrate of vacuolated cells, along with wreathlike giant cells (Touton cells) and eosinophils.3 Although these Touton cells are thought to be pathognomonic of JXG, early lesions may lack these cells.8 Thus, their absence does not exclude the diagnosis of JXG. These are more serious cases, and the work-up conducted depends upon the organ system(s) involved. Systemic disease occurs in approximately 5% of patients.

Treatment and prognosis

Clinical monitoring is the only therapy required if there are only a few cutaneous JXGs present. However, systemic JXG is a concerning disease and various chemotherapy regimens have been recommended.3 Additionally, the use of a vinca alkaloid in conjunction with a steroid is associated with better outcomes than either of these agents alone.9 As a word of caution, in one study of 12 patients who received therapeutic systemic chemotherapy or radiation therapy to the brain, eye, skin, or heart, the patients had long-term disabilities and 2 patients died of their disease.4 In another study, children with systemic JXG, again, had a poor prognosis: Despite courses of multiagent chemotherapy, 2 of 17 patients died.9

Despite the poor results associated with systemic JXG, the vast majority of JXG patients have localized disease, which is associated with an excellent prognosis. The majority of these lesions spontaneously regress.

In conclusion, JXG is typically a benign, cutaneous disease. It presents in infants and children and involutes over a 1-5 year period. Lesions that are not classic for JXG should be referred to a pediatric dermatologist, and biopsy is the gold standard diagnosis. Most manifestations of JXG do not require therapy. However, systemic JXG may be difficult to treat and is associated with poor outcomes.

Dr. Catalina Matiz is assistant professor of dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, associated with the University of California, San Diego. Jeremy Udkoff is a medical student at the university. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Mr. Udkoff have relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005 Jan;29(1):21-8.

2. Int J Dermatol. 2015 Oct;54(10):1109-23.

4. J Pediatr. 1996 Aug;129(2):227-37.

5. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996 Mar;34(3):445-9.

6. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb 8. pii: S0190-9622(16)31196-3.

7. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004 Mar-Apr;21(2):97-101.

BY JEREMY UDKOFF AND CATALINA MATIZ, MD

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG), a non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, is a common pediatric tumor that most commonly presents either at birth, in infants, or in young children – with the majority of cases occurring before 2 years. There is a male predominance with a 50% increased prevalence for solitary lesion disease and a 12 times higher prevalence in multilesion disease.1 Few lesions are concerning, and spontaneous regression of cutaneous lesions over the subsequent 1-5 years is a hallmark feature of JXG.2

Clinically, the JXGs are initially smooth, pinkish papules that may enlarge to 1-cm nodules and become yellowish in appearance before resolving to become atrophic macules or patches.2,3 JXGs are firm but rubbery and may become scaly and/or ulcerate as the lesion progresses.2 The JXGs most frequently occur superficially on the scalp and flexural areas of the upper extremities but infrequently present in the subcutaneous soft tissue, central nervous system, liver/spleen, eye/orbit, oropharynx, and muscle tissue.3,4 A well-described and concerning extracutaneous manifestations of JXG is ocular involvement and may be associated with bleeding into the anterior chamber of the eye. Despite this potentially disabling complication, screening for ocular involvement is recommended only in patients under age 2 years and in those with multiple skin lesions.5

The etiology of JXG is largely unknown. However, an association between neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and the development of JXG and other diseases such as juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, previously called juvenile chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, exists. It was thought that patients with NF1 and JXGs had a higher risk to develop juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.6 However, a recent study showed that JXG alone does not appear to confer an increased risk for developing malignancy in children with NF1.6,7

Differential diagnosis and work-up

The clinical differential diagnosis for JXG includes dermatofibromas, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, mastocytosis, Spitz nevus, hemangioendothelioma, and other xanthomas. Because of the concerning nature of these look-alikes, equivocal cases should be referred to a pediatric dermatologist.

Although, altered laboratory values may be seen with systemic JXG with solid organ involvement, there are no systemic tests that can be used to determine if a cutaneous lesion is JXG. Thus, biopsy is the gold standard diagnostic for confirmatory testing. As a histiocytic disorder, JXG will display various macrophages on histologic examination. Additionally, one may observe a dense dermal infiltrate of vacuolated cells, along with wreathlike giant cells (Touton cells) and eosinophils.3 Although these Touton cells are thought to be pathognomonic of JXG, early lesions may lack these cells.8 Thus, their absence does not exclude the diagnosis of JXG. These are more serious cases, and the work-up conducted depends upon the organ system(s) involved. Systemic disease occurs in approximately 5% of patients.

Treatment and prognosis

Clinical monitoring is the only therapy required if there are only a few cutaneous JXGs present. However, systemic JXG is a concerning disease and various chemotherapy regimens have been recommended.3 Additionally, the use of a vinca alkaloid in conjunction with a steroid is associated with better outcomes than either of these agents alone.9 As a word of caution, in one study of 12 patients who received therapeutic systemic chemotherapy or radiation therapy to the brain, eye, skin, or heart, the patients had long-term disabilities and 2 patients died of their disease.4 In another study, children with systemic JXG, again, had a poor prognosis: Despite courses of multiagent chemotherapy, 2 of 17 patients died.9

Despite the poor results associated with systemic JXG, the vast majority of JXG patients have localized disease, which is associated with an excellent prognosis. The majority of these lesions spontaneously regress.

In conclusion, JXG is typically a benign, cutaneous disease. It presents in infants and children and involutes over a 1-5 year period. Lesions that are not classic for JXG should be referred to a pediatric dermatologist, and biopsy is the gold standard diagnosis. Most manifestations of JXG do not require therapy. However, systemic JXG may be difficult to treat and is associated with poor outcomes.

Dr. Catalina Matiz is assistant professor of dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, associated with the University of California, San Diego. Jeremy Udkoff is a medical student at the university. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Mr. Udkoff have relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005 Jan;29(1):21-8.

2. Int J Dermatol. 2015 Oct;54(10):1109-23.

4. J Pediatr. 1996 Aug;129(2):227-37.

5. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996 Mar;34(3):445-9.

6. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb 8. pii: S0190-9622(16)31196-3.

7. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004 Mar-Apr;21(2):97-101.

BY JEREMY UDKOFF AND CATALINA MATIZ, MD

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG), a non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, is a common pediatric tumor that most commonly presents either at birth, in infants, or in young children – with the majority of cases occurring before 2 years. There is a male predominance with a 50% increased prevalence for solitary lesion disease and a 12 times higher prevalence in multilesion disease.1 Few lesions are concerning, and spontaneous regression of cutaneous lesions over the subsequent 1-5 years is a hallmark feature of JXG.2

Clinically, the JXGs are initially smooth, pinkish papules that may enlarge to 1-cm nodules and become yellowish in appearance before resolving to become atrophic macules or patches.2,3 JXGs are firm but rubbery and may become scaly and/or ulcerate as the lesion progresses.2 The JXGs most frequently occur superficially on the scalp and flexural areas of the upper extremities but infrequently present in the subcutaneous soft tissue, central nervous system, liver/spleen, eye/orbit, oropharynx, and muscle tissue.3,4 A well-described and concerning extracutaneous manifestations of JXG is ocular involvement and may be associated with bleeding into the anterior chamber of the eye. Despite this potentially disabling complication, screening for ocular involvement is recommended only in patients under age 2 years and in those with multiple skin lesions.5

The etiology of JXG is largely unknown. However, an association between neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and the development of JXG and other diseases such as juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, previously called juvenile chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, exists. It was thought that patients with NF1 and JXGs had a higher risk to develop juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.6 However, a recent study showed that JXG alone does not appear to confer an increased risk for developing malignancy in children with NF1.6,7

Differential diagnosis and work-up

The clinical differential diagnosis for JXG includes dermatofibromas, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, mastocytosis, Spitz nevus, hemangioendothelioma, and other xanthomas. Because of the concerning nature of these look-alikes, equivocal cases should be referred to a pediatric dermatologist.

Although, altered laboratory values may be seen with systemic JXG with solid organ involvement, there are no systemic tests that can be used to determine if a cutaneous lesion is JXG. Thus, biopsy is the gold standard diagnostic for confirmatory testing. As a histiocytic disorder, JXG will display various macrophages on histologic examination. Additionally, one may observe a dense dermal infiltrate of vacuolated cells, along with wreathlike giant cells (Touton cells) and eosinophils.3 Although these Touton cells are thought to be pathognomonic of JXG, early lesions may lack these cells.8 Thus, their absence does not exclude the diagnosis of JXG. These are more serious cases, and the work-up conducted depends upon the organ system(s) involved. Systemic disease occurs in approximately 5% of patients.

Treatment and prognosis

Clinical monitoring is the only therapy required if there are only a few cutaneous JXGs present. However, systemic JXG is a concerning disease and various chemotherapy regimens have been recommended.3 Additionally, the use of a vinca alkaloid in conjunction with a steroid is associated with better outcomes than either of these agents alone.9 As a word of caution, in one study of 12 patients who received therapeutic systemic chemotherapy or radiation therapy to the brain, eye, skin, or heart, the patients had long-term disabilities and 2 patients died of their disease.4 In another study, children with systemic JXG, again, had a poor prognosis: Despite courses of multiagent chemotherapy, 2 of 17 patients died.9

Despite the poor results associated with systemic JXG, the vast majority of JXG patients have localized disease, which is associated with an excellent prognosis. The majority of these lesions spontaneously regress.

In conclusion, JXG is typically a benign, cutaneous disease. It presents in infants and children and involutes over a 1-5 year period. Lesions that are not classic for JXG should be referred to a pediatric dermatologist, and biopsy is the gold standard diagnosis. Most manifestations of JXG do not require therapy. However, systemic JXG may be difficult to treat and is associated with poor outcomes.

Dr. Catalina Matiz is assistant professor of dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, associated with the University of California, San Diego. Jeremy Udkoff is a medical student at the university. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Mr. Udkoff have relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005 Jan;29(1):21-8.

2. Int J Dermatol. 2015 Oct;54(10):1109-23.

4. J Pediatr. 1996 Aug;129(2):227-37.

5. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996 Mar;34(3):445-9.

6. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb 8. pii: S0190-9622(16)31196-3.

7. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004 Mar-Apr;21(2):97-101.

One month later, the patient returned to our clinic with an urgent concern. The patient accidentally scraped the lesion, and it bled heavily for 15 minutes before subsiding. The mother stated that the lesion grew rapidly since the prior visit and became painful. On repeat physical examination the lesion was a 1-cm fungiform, yellow to pink nodule, with central ulceration.

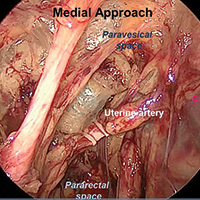

Approaches to isolating the uterine artery at its origin from the internal iliac artery

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

More videos from SGS:

- Advanced techniques in cystectomy for mature cystic teratomas

- Novel classification of labial anatomy and evaluation in the treatment of labial agglutination

- Strategies for prophylactic oophoropexy

- Tips and tricks for open laparoscopy

- Complete colpectomy & colpocleisis: Model for simulation

- Natural orifice sacral colpopexy

- Alternative options for visualizing ureteral patency during intraoperative cystoscopy

- Use of suprapubic Carter-Thomason needle to assist in cystoscopic excision of an intravesical foreign object

- Uterine artery ligation: Advanced techniques and considerations for the difficult laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Cervical injection of methylene blue for identification of sentinel lymph nodes in cervical cancer

- Misplaced hysteroscopic sterilization micro-insert in the peritoneal cavity: A corpus alienum

- Laparoscopic cystectomy for large, bilateral ovarian dermoids

- Small bowel surgery for the benign gynecologist

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

More videos from SGS:

- Advanced techniques in cystectomy for mature cystic teratomas

- Novel classification of labial anatomy and evaluation in the treatment of labial agglutination

- Strategies for prophylactic oophoropexy

- Tips and tricks for open laparoscopy

- Complete colpectomy & colpocleisis: Model for simulation

- Natural orifice sacral colpopexy

- Alternative options for visualizing ureteral patency during intraoperative cystoscopy

- Use of suprapubic Carter-Thomason needle to assist in cystoscopic excision of an intravesical foreign object

- Uterine artery ligation: Advanced techniques and considerations for the difficult laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Cervical injection of methylene blue for identification of sentinel lymph nodes in cervical cancer

- Misplaced hysteroscopic sterilization micro-insert in the peritoneal cavity: A corpus alienum

- Laparoscopic cystectomy for large, bilateral ovarian dermoids

- Small bowel surgery for the benign gynecologist

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

More videos from SGS:

- Advanced techniques in cystectomy for mature cystic teratomas

- Novel classification of labial anatomy and evaluation in the treatment of labial agglutination

- Strategies for prophylactic oophoropexy

- Tips and tricks for open laparoscopy

- Complete colpectomy & colpocleisis: Model for simulation

- Natural orifice sacral colpopexy

- Alternative options for visualizing ureteral patency during intraoperative cystoscopy

- Use of suprapubic Carter-Thomason needle to assist in cystoscopic excision of an intravesical foreign object

- Uterine artery ligation: Advanced techniques and considerations for the difficult laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Cervical injection of methylene blue for identification of sentinel lymph nodes in cervical cancer

- Misplaced hysteroscopic sterilization micro-insert in the peritoneal cavity: A corpus alienum

- Laparoscopic cystectomy for large, bilateral ovarian dermoids

- Small bowel surgery for the benign gynecologist

This video is brought to you by

Newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma is ‘one of the hardest consultations’

NEW YORK – Relatively young patients with newly diagnosed, average-risk mantle cell lymphoma who go into remission on induction therapy face a difficult choice on their next management step: undergo immediate autologous stem cell transplantation or defer the stem cell transplant and continue on maintenance therapy.

The choice is especially difficult because both are currently considered reasonable options and each choice has certain attractions and downsides, experts highlighted in discussing this fork-in-the-road decision patients face.

Immediate autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has a good chance to allow the patient to remain treatment free and in remission for as long as about 10 years, but it involves intensive upfront treatment for 6-9 months, during which the patient will likely not be able to work or carry on many usual activities. Deferring the transplant with maintenance therapy puts off this life-disrupting initial period of intensive therapy for what may be several years, but relapse on maintenance therapy is inevitable and once it happens the patient may not have as successful an outcome from an ASCT. It also means several years of ongoing drug therapy with a maintenance regimen.

“I tell my fellows that patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma [are] one of the hardest consultations because, unlike most other lymphomas, there is no established standard therapy but a range of options,” Timothy S. Fenske, MD, said at the conference held by Imedex. “I go through the pros and cons with patients, and it comes down to the patient’s perceived quality of life and their lifestyle.”

“It’s a very difficult decision [for patients] because we don’t have the data we’d like to have,” observed Peter Martin, MD, director of the clinical research program in lymphoma at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

“There is a lot of upfront toxicity with transplantation, with 6-9 months out of work in my experience. Patients often tell me that they can’t afford to do that; they’ll lose their employment insurance and won’t be able to pay for replacement insurance. But then they will hopefully go 6-10 years without more treatment, which is a real benefit. With less intensive upfront treatment they have a chance for similar overall survival, but they’ll need more ongoing treatment. It’s pretty complicated and challenging” for patients to make a decision, he said. “It depends a lot on where patients are in their lives and what they are willing to accept,” Dr. Martin said.

In general, Dr. Martin took a more skeptical view of ASCT than Dr. Fenske. “There is no evidence that ASCT cures patients or prolongs their survival. It improves progression-free survival, but not necessarily overall survival,” Dr. Martin noted.

In fact, a report in December 2016 at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting (Blood. 2016 Dec 5;abstract 1095) suggested that “biology is the primary driver of outcomes in mantle cell lymphoma, not treatment,” said Dr. Martin. The results from a limited number of patients enrolled in the Nordic mantle cell lymphoma trials provided good but preliminary evidence that “if you have good biology it doesn’t matter what the treatment is, you will do well,” he explained.

In fact, a report in December 2016 at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting (Blood. 2016 Dec 5;abstract 1095) suggested that “biology is the primary driver of outcomes in mantle cell lymphoma, not treatment,” said Dr. Martin. The results from a limited number of patients enrolled in the Nordic mantle cell lymphoma trials provided good but preliminary evidence that “less intense therapy works just as well” as more intense therapy, as long as the patient has a favorable genetic profile, he explained.

In contrast, Dr. Fenske put a much more positive spin on more intensive treatment upfront with ASCT.

“There is not much debate that you get longer progression-free survival with the more intensive approach. The question is, does progression-free survival matter in mantle cell lymphoma? I argue that it does because relapse in patients with mantle cell lymphoma is no picnic. What you can expect in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma is a progression-free survival of about 1-2 years, and an overall survival of about 2-3 years,” said Dr. Fenske, head of the section of bone marrow transplant and hematologic malignancies at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

As an example of the poor prognosis of relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma patients Dr. Fenske cited a review he coauthored of 97 patients treated with ibrutinib (Imbruvica. Their median duration of response was 17 months and median progression-free survival was 15 months. Once ibrutinib treatment failure occurred their median overall survival was less than 3 months. (Hematol Oncol. 2017 Jan 8.doi:10.1002/hon.2380).

“It’s easy to get carried away” when patients temporarily respond to a drug like ibrutinib or other new agents with a degree of efficacy for lymphomas, Dr. Fenske said, but these transient responses “don’t solve the problem. The patient is headed for trouble,” usually within a couple of years.

“I would argue that, especially for younger patients, the goal is to try to achieve the longest first remission, and that means an ASCT.” Dr. Fenske admitted that this strategy won’t work for very-high-risk patients, but for these patients no good treatment options currently exist.

He also stressed that research is just beginning to explore using measurement of negative minimal residual disease to identify patients with the best outcomes following initial induction treatment. It is possible that patients with undetectable minimal residual disease can avoid immediate ASCT and instead receive maintenance therapy, a hypothesis slated for testing in a randomized trial, he said.

Dr. Martin has been a consultant to Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, and Verastem. Dr. Fenske has been a consultant to Abbvie, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Sanofi, and Seattle Genetics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

This article was updated May 30, 2017 .

NEW YORK – Relatively young patients with newly diagnosed, average-risk mantle cell lymphoma who go into remission on induction therapy face a difficult choice on their next management step: undergo immediate autologous stem cell transplantation or defer the stem cell transplant and continue on maintenance therapy.

The choice is especially difficult because both are currently considered reasonable options and each choice has certain attractions and downsides, experts highlighted in discussing this fork-in-the-road decision patients face.

Immediate autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has a good chance to allow the patient to remain treatment free and in remission for as long as about 10 years, but it involves intensive upfront treatment for 6-9 months, during which the patient will likely not be able to work or carry on many usual activities. Deferring the transplant with maintenance therapy puts off this life-disrupting initial period of intensive therapy for what may be several years, but relapse on maintenance therapy is inevitable and once it happens the patient may not have as successful an outcome from an ASCT. It also means several years of ongoing drug therapy with a maintenance regimen.

“I tell my fellows that patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma [are] one of the hardest consultations because, unlike most other lymphomas, there is no established standard therapy but a range of options,” Timothy S. Fenske, MD, said at the conference held by Imedex. “I go through the pros and cons with patients, and it comes down to the patient’s perceived quality of life and their lifestyle.”

“It’s a very difficult decision [for patients] because we don’t have the data we’d like to have,” observed Peter Martin, MD, director of the clinical research program in lymphoma at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

“There is a lot of upfront toxicity with transplantation, with 6-9 months out of work in my experience. Patients often tell me that they can’t afford to do that; they’ll lose their employment insurance and won’t be able to pay for replacement insurance. But then they will hopefully go 6-10 years without more treatment, which is a real benefit. With less intensive upfront treatment they have a chance for similar overall survival, but they’ll need more ongoing treatment. It’s pretty complicated and challenging” for patients to make a decision, he said. “It depends a lot on where patients are in their lives and what they are willing to accept,” Dr. Martin said.

In general, Dr. Martin took a more skeptical view of ASCT than Dr. Fenske. “There is no evidence that ASCT cures patients or prolongs their survival. It improves progression-free survival, but not necessarily overall survival,” Dr. Martin noted.

In fact, a report in December 2016 at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting (Blood. 2016 Dec 5;abstract 1095) suggested that “biology is the primary driver of outcomes in mantle cell lymphoma, not treatment,” said Dr. Martin. The results from a limited number of patients enrolled in the Nordic mantle cell lymphoma trials provided good but preliminary evidence that “if you have good biology it doesn’t matter what the treatment is, you will do well,” he explained.

In fact, a report in December 2016 at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting (Blood. 2016 Dec 5;abstract 1095) suggested that “biology is the primary driver of outcomes in mantle cell lymphoma, not treatment,” said Dr. Martin. The results from a limited number of patients enrolled in the Nordic mantle cell lymphoma trials provided good but preliminary evidence that “less intense therapy works just as well” as more intense therapy, as long as the patient has a favorable genetic profile, he explained.

In contrast, Dr. Fenske put a much more positive spin on more intensive treatment upfront with ASCT.

“There is not much debate that you get longer progression-free survival with the more intensive approach. The question is, does progression-free survival matter in mantle cell lymphoma? I argue that it does because relapse in patients with mantle cell lymphoma is no picnic. What you can expect in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma is a progression-free survival of about 1-2 years, and an overall survival of about 2-3 years,” said Dr. Fenske, head of the section of bone marrow transplant and hematologic malignancies at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

As an example of the poor prognosis of relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma patients Dr. Fenske cited a review he coauthored of 97 patients treated with ibrutinib (Imbruvica. Their median duration of response was 17 months and median progression-free survival was 15 months. Once ibrutinib treatment failure occurred their median overall survival was less than 3 months. (Hematol Oncol. 2017 Jan 8.doi:10.1002/hon.2380).

“It’s easy to get carried away” when patients temporarily respond to a drug like ibrutinib or other new agents with a degree of efficacy for lymphomas, Dr. Fenske said, but these transient responses “don’t solve the problem. The patient is headed for trouble,” usually within a couple of years.

“I would argue that, especially for younger patients, the goal is to try to achieve the longest first remission, and that means an ASCT.” Dr. Fenske admitted that this strategy won’t work for very-high-risk patients, but for these patients no good treatment options currently exist.

He also stressed that research is just beginning to explore using measurement of negative minimal residual disease to identify patients with the best outcomes following initial induction treatment. It is possible that patients with undetectable minimal residual disease can avoid immediate ASCT and instead receive maintenance therapy, a hypothesis slated for testing in a randomized trial, he said.

Dr. Martin has been a consultant to Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, and Verastem. Dr. Fenske has been a consultant to Abbvie, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Sanofi, and Seattle Genetics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

This article was updated May 30, 2017 .

NEW YORK – Relatively young patients with newly diagnosed, average-risk mantle cell lymphoma who go into remission on induction therapy face a difficult choice on their next management step: undergo immediate autologous stem cell transplantation or defer the stem cell transplant and continue on maintenance therapy.

The choice is especially difficult because both are currently considered reasonable options and each choice has certain attractions and downsides, experts highlighted in discussing this fork-in-the-road decision patients face.

Immediate autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has a good chance to allow the patient to remain treatment free and in remission for as long as about 10 years, but it involves intensive upfront treatment for 6-9 months, during which the patient will likely not be able to work or carry on many usual activities. Deferring the transplant with maintenance therapy puts off this life-disrupting initial period of intensive therapy for what may be several years, but relapse on maintenance therapy is inevitable and once it happens the patient may not have as successful an outcome from an ASCT. It also means several years of ongoing drug therapy with a maintenance regimen.

“I tell my fellows that patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma [are] one of the hardest consultations because, unlike most other lymphomas, there is no established standard therapy but a range of options,” Timothy S. Fenske, MD, said at the conference held by Imedex. “I go through the pros and cons with patients, and it comes down to the patient’s perceived quality of life and their lifestyle.”

“It’s a very difficult decision [for patients] because we don’t have the data we’d like to have,” observed Peter Martin, MD, director of the clinical research program in lymphoma at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

“There is a lot of upfront toxicity with transplantation, with 6-9 months out of work in my experience. Patients often tell me that they can’t afford to do that; they’ll lose their employment insurance and won’t be able to pay for replacement insurance. But then they will hopefully go 6-10 years without more treatment, which is a real benefit. With less intensive upfront treatment they have a chance for similar overall survival, but they’ll need more ongoing treatment. It’s pretty complicated and challenging” for patients to make a decision, he said. “It depends a lot on where patients are in their lives and what they are willing to accept,” Dr. Martin said.

In general, Dr. Martin took a more skeptical view of ASCT than Dr. Fenske. “There is no evidence that ASCT cures patients or prolongs their survival. It improves progression-free survival, but not necessarily overall survival,” Dr. Martin noted.

In fact, a report in December 2016 at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting (Blood. 2016 Dec 5;abstract 1095) suggested that “biology is the primary driver of outcomes in mantle cell lymphoma, not treatment,” said Dr. Martin. The results from a limited number of patients enrolled in the Nordic mantle cell lymphoma trials provided good but preliminary evidence that “if you have good biology it doesn’t matter what the treatment is, you will do well,” he explained.

In fact, a report in December 2016 at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting (Blood. 2016 Dec 5;abstract 1095) suggested that “biology is the primary driver of outcomes in mantle cell lymphoma, not treatment,” said Dr. Martin. The results from a limited number of patients enrolled in the Nordic mantle cell lymphoma trials provided good but preliminary evidence that “less intense therapy works just as well” as more intense therapy, as long as the patient has a favorable genetic profile, he explained.

In contrast, Dr. Fenske put a much more positive spin on more intensive treatment upfront with ASCT.

“There is not much debate that you get longer progression-free survival with the more intensive approach. The question is, does progression-free survival matter in mantle cell lymphoma? I argue that it does because relapse in patients with mantle cell lymphoma is no picnic. What you can expect in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma is a progression-free survival of about 1-2 years, and an overall survival of about 2-3 years,” said Dr. Fenske, head of the section of bone marrow transplant and hematologic malignancies at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

As an example of the poor prognosis of relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma patients Dr. Fenske cited a review he coauthored of 97 patients treated with ibrutinib (Imbruvica. Their median duration of response was 17 months and median progression-free survival was 15 months. Once ibrutinib treatment failure occurred their median overall survival was less than 3 months. (Hematol Oncol. 2017 Jan 8.doi:10.1002/hon.2380).

“It’s easy to get carried away” when patients temporarily respond to a drug like ibrutinib or other new agents with a degree of efficacy for lymphomas, Dr. Fenske said, but these transient responses “don’t solve the problem. The patient is headed for trouble,” usually within a couple of years.

“I would argue that, especially for younger patients, the goal is to try to achieve the longest first remission, and that means an ASCT.” Dr. Fenske admitted that this strategy won’t work for very-high-risk patients, but for these patients no good treatment options currently exist.

He also stressed that research is just beginning to explore using measurement of negative minimal residual disease to identify patients with the best outcomes following initial induction treatment. It is possible that patients with undetectable minimal residual disease can avoid immediate ASCT and instead receive maintenance therapy, a hypothesis slated for testing in a randomized trial, he said.

Dr. Martin has been a consultant to Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, and Verastem. Dr. Fenske has been a consultant to Abbvie, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Sanofi, and Seattle Genetics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

This article was updated May 30, 2017 .

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON HEMATOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES

Flashback to 2011

Barrett’s esophagus, named after Australian-born thoracic surgeon Norman Barrett in the 1950s, is now recognized as an important risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Estimating the magnitude of this risk has proved challenging; however, as early studies of Barrett’s esophagus tended to overestimate cancer risk because of small sample sizes and selection bias. Accurate risk estimation has profound implications for whether and how to identify and monitor patients with Barrett’s esophagus as part of a cancer-prevention strategy.

The December 2011 issue of GI & Hepatology News highlighted an influential study by Frederik Hvid-Jensen and his colleagues from Aarhus (Denmark) University that harnessed the power of Danish population-based registries to estimate the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma and high-grade dysplasia among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2011;365:1375-83), the study utilized data from Denmark’s national pathology and cancer registries to calculate the incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus, compared with the general population. The study was unique in that there was nearly no loss to follow-up and no referral bias because of the nature of the registry.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc, is a general gastroenterologist at Veterans Affairs, an investigator in the VA Center for Clinical Management Research, and a lecturer in gastroenterology at the University of Michigan, all in Ann Arbor. She currently serves as chair-elect of the AGA Quality Measures Committee and is an associate editor of GI & Hepatology News.

Barrett’s esophagus, named after Australian-born thoracic surgeon Norman Barrett in the 1950s, is now recognized as an important risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Estimating the magnitude of this risk has proved challenging; however, as early studies of Barrett’s esophagus tended to overestimate cancer risk because of small sample sizes and selection bias. Accurate risk estimation has profound implications for whether and how to identify and monitor patients with Barrett’s esophagus as part of a cancer-prevention strategy.

The December 2011 issue of GI & Hepatology News highlighted an influential study by Frederik Hvid-Jensen and his colleagues from Aarhus (Denmark) University that harnessed the power of Danish population-based registries to estimate the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma and high-grade dysplasia among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2011;365:1375-83), the study utilized data from Denmark’s national pathology and cancer registries to calculate the incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus, compared with the general population. The study was unique in that there was nearly no loss to follow-up and no referral bias because of the nature of the registry.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc, is a general gastroenterologist at Veterans Affairs, an investigator in the VA Center for Clinical Management Research, and a lecturer in gastroenterology at the University of Michigan, all in Ann Arbor. She currently serves as chair-elect of the AGA Quality Measures Committee and is an associate editor of GI & Hepatology News.

Barrett’s esophagus, named after Australian-born thoracic surgeon Norman Barrett in the 1950s, is now recognized as an important risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Estimating the magnitude of this risk has proved challenging; however, as early studies of Barrett’s esophagus tended to overestimate cancer risk because of small sample sizes and selection bias. Accurate risk estimation has profound implications for whether and how to identify and monitor patients with Barrett’s esophagus as part of a cancer-prevention strategy.

The December 2011 issue of GI & Hepatology News highlighted an influential study by Frederik Hvid-Jensen and his colleagues from Aarhus (Denmark) University that harnessed the power of Danish population-based registries to estimate the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma and high-grade dysplasia among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2011;365:1375-83), the study utilized data from Denmark’s national pathology and cancer registries to calculate the incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus, compared with the general population. The study was unique in that there was nearly no loss to follow-up and no referral bias because of the nature of the registry.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc, is a general gastroenterologist at Veterans Affairs, an investigator in the VA Center for Clinical Management Research, and a lecturer in gastroenterology at the University of Michigan, all in Ann Arbor. She currently serves as chair-elect of the AGA Quality Measures Committee and is an associate editor of GI & Hepatology News.

Letter from the Editor: Spring brings flowers and liver stories

Happy spring (finally, for many of us)! This month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News is “weighted” towards liver. The decrease in hepatitis C–related liver disease means that steatohepatitis will emerge as the most frequent cause of cirrhosis and transplantation. Finding medical therapies to slow obesity-related liver damage has proven challenging. Bariatric surgery may be the best option for patients, as pointed out by one of our lead stories. Another page one story lays out a roadmap to eliminate viral hepatitis in the United States, a situation unheard of until direct-acting antiviral agents were developed.

The AGA’s contribution to this month’s issue is excellent. First, there is the continuing controversy regarding maintenance of certification. AGA has worked hard to eliminate the 10-year high-impact closed book examination (now an anachronism). We will have the option of a 2-year exam (open book) and you will need to become familiar with testing proposals so we all can add voices of reason to the ABIM process.

Additionally, the AGA highlights the POWER guideline (weight management) and its obesity resources, DDSEP® 8 and a new clinical guideline concerning transient elastography.

We close this month’s issue with a discussion from Ray Cross and Sunanda Kane about telemedicine and its impact on gastroenterology. There are multiple examples of how telemedicine is changing our practices and the piece provides hope for increased efficiencies and leveraged resources.

I hope you enjoy this issue. I have avoided my usual hints about our chaotic politics and its impact on our practices. We all need some relief and should take time to note the spring flowers.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Happy spring (finally, for many of us)! This month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News is “weighted” towards liver. The decrease in hepatitis C–related liver disease means that steatohepatitis will emerge as the most frequent cause of cirrhosis and transplantation. Finding medical therapies to slow obesity-related liver damage has proven challenging. Bariatric surgery may be the best option for patients, as pointed out by one of our lead stories. Another page one story lays out a roadmap to eliminate viral hepatitis in the United States, a situation unheard of until direct-acting antiviral agents were developed.

The AGA’s contribution to this month’s issue is excellent. First, there is the continuing controversy regarding maintenance of certification. AGA has worked hard to eliminate the 10-year high-impact closed book examination (now an anachronism). We will have the option of a 2-year exam (open book) and you will need to become familiar with testing proposals so we all can add voices of reason to the ABIM process.

Additionally, the AGA highlights the POWER guideline (weight management) and its obesity resources, DDSEP® 8 and a new clinical guideline concerning transient elastography.

We close this month’s issue with a discussion from Ray Cross and Sunanda Kane about telemedicine and its impact on gastroenterology. There are multiple examples of how telemedicine is changing our practices and the piece provides hope for increased efficiencies and leveraged resources.

I hope you enjoy this issue. I have avoided my usual hints about our chaotic politics and its impact on our practices. We all need some relief and should take time to note the spring flowers.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Happy spring (finally, for many of us)! This month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News is “weighted” towards liver. The decrease in hepatitis C–related liver disease means that steatohepatitis will emerge as the most frequent cause of cirrhosis and transplantation. Finding medical therapies to slow obesity-related liver damage has proven challenging. Bariatric surgery may be the best option for patients, as pointed out by one of our lead stories. Another page one story lays out a roadmap to eliminate viral hepatitis in the United States, a situation unheard of until direct-acting antiviral agents were developed.

The AGA’s contribution to this month’s issue is excellent. First, there is the continuing controversy regarding maintenance of certification. AGA has worked hard to eliminate the 10-year high-impact closed book examination (now an anachronism). We will have the option of a 2-year exam (open book) and you will need to become familiar with testing proposals so we all can add voices of reason to the ABIM process.

Additionally, the AGA highlights the POWER guideline (weight management) and its obesity resources, DDSEP® 8 and a new clinical guideline concerning transient elastography.

We close this month’s issue with a discussion from Ray Cross and Sunanda Kane about telemedicine and its impact on gastroenterology. There are multiple examples of how telemedicine is changing our practices and the piece provides hope for increased efficiencies and leveraged resources.

I hope you enjoy this issue. I have avoided my usual hints about our chaotic politics and its impact on our practices. We all need some relief and should take time to note the spring flowers.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Preterm infants face increased pertussis risk

Pertussis is more likely in infants who are born prematurely, compared with infants carried to term, according to Dr. Øystein Rolandsen Riise of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, and associates.

Using data from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway, 713,166 children were monitored until the age of 2 years from 1998 to 2010, during which time 968 cases of pertussis were laboratory confirmed. The incidence rate in term infants was 67.9 cases per 100,000 person-years, and was 115.2 cases per 100,000 person-years for preterm infants. The overall incidence rate ratio (IRR) of pertussis for preterm infants was 1.65, compared with term infants.

Hospitalization due to pertussis also was significantly more likely in preterm infants, with an overall IRR of 1.99, and infants born at 23-27 weeks again faced a greatly increased risk, with an IRR of 5.28.

Three-dose vaccine effectiveness against reported pertussis was 88.8% in term infants and 93% in preterm infants.

“Early and timely pediatric vaccinations as well as other strategies to prevent transmission to preterm infants are of utmost importance,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal (2017 May. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001545).

Pertussis is more likely in infants who are born prematurely, compared with infants carried to term, according to Dr. Øystein Rolandsen Riise of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, and associates.

Using data from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway, 713,166 children were monitored until the age of 2 years from 1998 to 2010, during which time 968 cases of pertussis were laboratory confirmed. The incidence rate in term infants was 67.9 cases per 100,000 person-years, and was 115.2 cases per 100,000 person-years for preterm infants. The overall incidence rate ratio (IRR) of pertussis for preterm infants was 1.65, compared with term infants.

Hospitalization due to pertussis also was significantly more likely in preterm infants, with an overall IRR of 1.99, and infants born at 23-27 weeks again faced a greatly increased risk, with an IRR of 5.28.

Three-dose vaccine effectiveness against reported pertussis was 88.8% in term infants and 93% in preterm infants.

“Early and timely pediatric vaccinations as well as other strategies to prevent transmission to preterm infants are of utmost importance,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal (2017 May. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001545).

Pertussis is more likely in infants who are born prematurely, compared with infants carried to term, according to Dr. Øystein Rolandsen Riise of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, and associates.

Using data from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway, 713,166 children were monitored until the age of 2 years from 1998 to 2010, during which time 968 cases of pertussis were laboratory confirmed. The incidence rate in term infants was 67.9 cases per 100,000 person-years, and was 115.2 cases per 100,000 person-years for preterm infants. The overall incidence rate ratio (IRR) of pertussis for preterm infants was 1.65, compared with term infants.

Hospitalization due to pertussis also was significantly more likely in preterm infants, with an overall IRR of 1.99, and infants born at 23-27 weeks again faced a greatly increased risk, with an IRR of 5.28.

Three-dose vaccine effectiveness against reported pertussis was 88.8% in term infants and 93% in preterm infants.

“Early and timely pediatric vaccinations as well as other strategies to prevent transmission to preterm infants are of utmost importance,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal (2017 May. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001545).

High early stroke risk for adult congenital heart disease

WASHINGTON – Adults with congenital heart disease are at fourfold greater risk of experiencing an ischemic stroke by age 60 than is the general population, Mette Glavind reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

She presented a population-based study that included all 14,710 Danish adults with congenital heart disease (ACHD) diagnosed in 1963-1994. Taking advantage of Denmark’s comprehensive system of linked national registries, she and her coinvestigators created a control group consisting of 144,735 age- and birth year–matched individuals from the general population.

During follow-up, a total of 2,868 Danes included in the study had an ischemic stroke. The cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke in the ACHD cohort was 0.8% by age 30 and 8.2% by age 60, compared with 0.09% and 2.9%, respectively, in controls, according to Ms. Glavind, a medical student at Aarhus (Denmark) University.

The median age at diagnosis of stroke was 52 years in the ACHD group and 69 years in controls. The risk of early ischemic stroke – defined as stroke at age 18-60 – was increased by 3.97-fold in the ACHD group, compared with controls. The risk of stroke after age 60 was increased by 1.68-fold.

Stroke was more likely to prove fatal in the ACHD group. Their 30-day stroke mortality rate was 10%, compared with 9.6% in controls. This corresponded to an adjusted 44% increased risk of stroke mortality, which was statistically significant.

The severity of congenital heart disease modified the stroke risk. Patients with mild or moderate ACHD had a 3.25-fold increased risk of early stroke, compared with controls, while those with severe or univentricular ACHD were at 5.97-fold greater risk.

For purposes of this study, mild ACHD was defined as a biventricular defect that was not repaired surgically or percutaneously. Moderate ACHD was considered to have biventricular pathophysiology with surgical or percutaneous intervention. The severe ACHD category was reserved for cases involving complex biventricular abnormalities.

By these definitions, 41% of patients had mild ACHD, 21% moderate, 22% severe, and 1% univentricular ACHD; the rest of the patients were unclassified.

This study was supported by Aarhus University and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. Ms. Glavind reported having no financial conflicts.

WASHINGTON – Adults with congenital heart disease are at fourfold greater risk of experiencing an ischemic stroke by age 60 than is the general population, Mette Glavind reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

She presented a population-based study that included all 14,710 Danish adults with congenital heart disease (ACHD) diagnosed in 1963-1994. Taking advantage of Denmark’s comprehensive system of linked national registries, she and her coinvestigators created a control group consisting of 144,735 age- and birth year–matched individuals from the general population.

During follow-up, a total of 2,868 Danes included in the study had an ischemic stroke. The cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke in the ACHD cohort was 0.8% by age 30 and 8.2% by age 60, compared with 0.09% and 2.9%, respectively, in controls, according to Ms. Glavind, a medical student at Aarhus (Denmark) University.

The median age at diagnosis of stroke was 52 years in the ACHD group and 69 years in controls. The risk of early ischemic stroke – defined as stroke at age 18-60 – was increased by 3.97-fold in the ACHD group, compared with controls. The risk of stroke after age 60 was increased by 1.68-fold.

Stroke was more likely to prove fatal in the ACHD group. Their 30-day stroke mortality rate was 10%, compared with 9.6% in controls. This corresponded to an adjusted 44% increased risk of stroke mortality, which was statistically significant.

The severity of congenital heart disease modified the stroke risk. Patients with mild or moderate ACHD had a 3.25-fold increased risk of early stroke, compared with controls, while those with severe or univentricular ACHD were at 5.97-fold greater risk.

For purposes of this study, mild ACHD was defined as a biventricular defect that was not repaired surgically or percutaneously. Moderate ACHD was considered to have biventricular pathophysiology with surgical or percutaneous intervention. The severe ACHD category was reserved for cases involving complex biventricular abnormalities.

By these definitions, 41% of patients had mild ACHD, 21% moderate, 22% severe, and 1% univentricular ACHD; the rest of the patients were unclassified.

This study was supported by Aarhus University and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. Ms. Glavind reported having no financial conflicts.

WASHINGTON – Adults with congenital heart disease are at fourfold greater risk of experiencing an ischemic stroke by age 60 than is the general population, Mette Glavind reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

She presented a population-based study that included all 14,710 Danish adults with congenital heart disease (ACHD) diagnosed in 1963-1994. Taking advantage of Denmark’s comprehensive system of linked national registries, she and her coinvestigators created a control group consisting of 144,735 age- and birth year–matched individuals from the general population.

During follow-up, a total of 2,868 Danes included in the study had an ischemic stroke. The cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke in the ACHD cohort was 0.8% by age 30 and 8.2% by age 60, compared with 0.09% and 2.9%, respectively, in controls, according to Ms. Glavind, a medical student at Aarhus (Denmark) University.

The median age at diagnosis of stroke was 52 years in the ACHD group and 69 years in controls. The risk of early ischemic stroke – defined as stroke at age 18-60 – was increased by 3.97-fold in the ACHD group, compared with controls. The risk of stroke after age 60 was increased by 1.68-fold.

Stroke was more likely to prove fatal in the ACHD group. Their 30-day stroke mortality rate was 10%, compared with 9.6% in controls. This corresponded to an adjusted 44% increased risk of stroke mortality, which was statistically significant.

The severity of congenital heart disease modified the stroke risk. Patients with mild or moderate ACHD had a 3.25-fold increased risk of early stroke, compared with controls, while those with severe or univentricular ACHD were at 5.97-fold greater risk.

For purposes of this study, mild ACHD was defined as a biventricular defect that was not repaired surgically or percutaneously. Moderate ACHD was considered to have biventricular pathophysiology with surgical or percutaneous intervention. The severe ACHD category was reserved for cases involving complex biventricular abnormalities.

By these definitions, 41% of patients had mild ACHD, 21% moderate, 22% severe, and 1% univentricular ACHD; the rest of the patients were unclassified.

This study was supported by Aarhus University and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. Ms. Glavind reported having no financial conflicts.

AT ACC 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Danish adults with complex biventricular congenital heart disease were sixfold more likely to have an ischemic stroke by age 60 years, compared with the general population.

Data source: A population-based registry study that included all Danish adults with congenital heart disease diagnosed in 1963-1994 and nearly 145,000 age- and birth year–matched controls drawn from the general Danish population.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Aarhus University and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Pharmacist-run PrEP clinic proves effective, profitable

SEATTLE – A pharmacist-run HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) clinic had a retention rate of 75% and achieved a financial return within the first year of operation.

The Seattle-area project allowed individuals to leave their first appointment with medication in hand, and it drew in many men who had no primary care provider.

The approach is a departure from typical PrEP assignment, in which a patient must navigate a provider, lab testing, a pharmacist, and the need for prior authorization, explained Elyse Tung-Wisner, PharmD, director of clinical services at Kelley-Ross Pharmacy, Seattle. That process can take a few days to a few weeks.

“For years, pharmacists have done glucose testing. A finger stick for an HIV test is a similar model. We applied the same protocol to PrEP,” said Dr. Tung-Wisner, who presented an analysis of the program in a poster session at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections in partnership with the International Antiviral Society.

In the program, patients can come in, receive counseling, undergo all tests, and the pharmacist can work through all the prior authorizations and patient-assistance programs. “Oftentimes, a patient can leave with medication in hand within an hour,” said Dr. Tung-Wisner.

“As far as we know, we’re the first in the country to have a pharmacist-run HIV PrEP clinic in a community pharmacy setting,” she added.

She and her colleagues presented data on the effectiveness and financial viability of what they term One-Step PrEP. In the program, pharmacists take a medical and sexual history of each patient, perform a risk assessment and laboratory testing, provide education, and prescribe and dispense PrEP if appropriate. The pharmacist also performs all guideline-recommended follow-up care.

From March 2015 through March 2016, 373 patients inquired about PrEP services. A total of 251 patients were evaluated in person and 245 (98%) went on to begin PrEP. Among those who started PrEP, 88% identified as men who have sex with men (mean age, 34 years; range, 18-64).

The program had a 75% retention rate over the first year, with one HIV seroconversion.

The initial start-up costs were recouped at 9 months, suggesting that the program quickly became financially sustainable.

It also reached a highly vulnerable, underserved population. The average men who have sex with men index score was 20, which indicates that the patients were high risk, Dr. Tung-Wisner noted.

And just 23% of the patients who were evaluated in person had a primary care provider. “That suggests we were accessing a patient population that has not already established care anywhere else,” she explained.

The program was run by Kelley-Ross Pharmacye. Dr. Tung-Wisner is an employee of the pharmacy.

SEATTLE – A pharmacist-run HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) clinic had a retention rate of 75% and achieved a financial return within the first year of operation.

The Seattle-area project allowed individuals to leave their first appointment with medication in hand, and it drew in many men who had no primary care provider.

The approach is a departure from typical PrEP assignment, in which a patient must navigate a provider, lab testing, a pharmacist, and the need for prior authorization, explained Elyse Tung-Wisner, PharmD, director of clinical services at Kelley-Ross Pharmacy, Seattle. That process can take a few days to a few weeks.

“For years, pharmacists have done glucose testing. A finger stick for an HIV test is a similar model. We applied the same protocol to PrEP,” said Dr. Tung-Wisner, who presented an analysis of the program in a poster session at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections in partnership with the International Antiviral Society.

In the program, patients can come in, receive counseling, undergo all tests, and the pharmacist can work through all the prior authorizations and patient-assistance programs. “Oftentimes, a patient can leave with medication in hand within an hour,” said Dr. Tung-Wisner.

“As far as we know, we’re the first in the country to have a pharmacist-run HIV PrEP clinic in a community pharmacy setting,” she added.

She and her colleagues presented data on the effectiveness and financial viability of what they term One-Step PrEP. In the program, pharmacists take a medical and sexual history of each patient, perform a risk assessment and laboratory testing, provide education, and prescribe and dispense PrEP if appropriate. The pharmacist also performs all guideline-recommended follow-up care.

From March 2015 through March 2016, 373 patients inquired about PrEP services. A total of 251 patients were evaluated in person and 245 (98%) went on to begin PrEP. Among those who started PrEP, 88% identified as men who have sex with men (mean age, 34 years; range, 18-64).

The program had a 75% retention rate over the first year, with one HIV seroconversion.

The initial start-up costs were recouped at 9 months, suggesting that the program quickly became financially sustainable.

It also reached a highly vulnerable, underserved population. The average men who have sex with men index score was 20, which indicates that the patients were high risk, Dr. Tung-Wisner noted.

And just 23% of the patients who were evaluated in person had a primary care provider. “That suggests we were accessing a patient population that has not already established care anywhere else,” she explained.

The program was run by Kelley-Ross Pharmacye. Dr. Tung-Wisner is an employee of the pharmacy.

SEATTLE – A pharmacist-run HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) clinic had a retention rate of 75% and achieved a financial return within the first year of operation.

The Seattle-area project allowed individuals to leave their first appointment with medication in hand, and it drew in many men who had no primary care provider.

The approach is a departure from typical PrEP assignment, in which a patient must navigate a provider, lab testing, a pharmacist, and the need for prior authorization, explained Elyse Tung-Wisner, PharmD, director of clinical services at Kelley-Ross Pharmacy, Seattle. That process can take a few days to a few weeks.

“For years, pharmacists have done glucose testing. A finger stick for an HIV test is a similar model. We applied the same protocol to PrEP,” said Dr. Tung-Wisner, who presented an analysis of the program in a poster session at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections in partnership with the International Antiviral Society.

In the program, patients can come in, receive counseling, undergo all tests, and the pharmacist can work through all the prior authorizations and patient-assistance programs. “Oftentimes, a patient can leave with medication in hand within an hour,” said Dr. Tung-Wisner.

“As far as we know, we’re the first in the country to have a pharmacist-run HIV PrEP clinic in a community pharmacy setting,” she added.

She and her colleagues presented data on the effectiveness and financial viability of what they term One-Step PrEP. In the program, pharmacists take a medical and sexual history of each patient, perform a risk assessment and laboratory testing, provide education, and prescribe and dispense PrEP if appropriate. The pharmacist also performs all guideline-recommended follow-up care.

From March 2015 through March 2016, 373 patients inquired about PrEP services. A total of 251 patients were evaluated in person and 245 (98%) went on to begin PrEP. Among those who started PrEP, 88% identified as men who have sex with men (mean age, 34 years; range, 18-64).

The program had a 75% retention rate over the first year, with one HIV seroconversion.

The initial start-up costs were recouped at 9 months, suggesting that the program quickly became financially sustainable.

It also reached a highly vulnerable, underserved population. The average men who have sex with men index score was 20, which indicates that the patients were high risk, Dr. Tung-Wisner noted.

And just 23% of the patients who were evaluated in person had a primary care provider. “That suggests we were accessing a patient population that has not already established care anywhere else,” she explained.

The program was run by Kelley-Ross Pharmacye. Dr. Tung-Wisner is an employee of the pharmacy.

Key clinical point: A pharmacist-run HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) clinic had a retention rate of 75% and achieved a financial return within the first year of operation.

Major finding: The retention rate was 75%, and only 23% of patients had a primary care physician.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of a program that served 251 patients.

Disclosures: The program was run by Kelley-Ross Pharmacy in Seattle. Dr. Tung-Wisner is an employee of the pharmacy.

Dealing with stealing

A 7-year-old boy, Jacob, with a history of ADHD and frequent impulsive behavior, takes a calculator from another child’s desk. About 3 months before, he had come home after taking another child’s action figure. His parents have been working on parent training for ADHD, but don’t know how to respond to this behavior and are very upset at their son.

Discussion

Stealing is an issue of serious concern to parents. To understand how common this is in younger children, researchers need to rely on the reports of parents and teachers, which may be underestimates of the problem because stealing is usually a hidden or covert behavior. Research on older youth can include anonymous self-reports.

Stealing and dishonesty are such disappointing behaviors to adults that it is tempting to resort to harsh punishments, long lectures, or harshly disparaging words. But these kinds of punishments backfire. The goal is an overall positive relationship and a calm consistent response to undesired behaviors. Parents often need support in how to be positive with a child who is frustrating them. Taking 15 minutes a day to do some activity a child likes – playing catch, playing a board game, cooking together, or doing crafts – all while noticing the positive things a child is doing rather than teaching, criticizing, or grilling a child on what happened in school sets a happier tone to the relationship, which is a background for any discipline. Jacob’s parents had already been working on this through their parent training class, but it helped to encourage them to keep doing this.