User login

Make the Diagnosis - May 2017

Dermatitis herpetiformis

The primary lesions of DH are vesicles and papules in a grouped or “herpetic” formation. However, as these lesions are extremely pruritic, the primary lesions may be absent in many cases and instead replaced by secondary excoriations and erosions. DH has a very classic distribution pattern, particularly involving the bilateral extensor surfaces, buttocks, and scalp. Although some cases of oral DH have been reported, mucosal involvement is generally considered to be very rare.

Despite its strong association with underlying celiac disease, most patients with DH do not report any associated gastrointestinal symptoms. Those with DH may present with any variety of other autoimmune conditions, with hypothyroidism being the most common. Interestingly, patients with DH have been shown to be at an increased development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It is not certain whether adherence to a strict gluten-free diet reduces this risk in this population.

Diagnosis can be made with a proper clinical history and examination, tissue pathology, direct immunofluorescence microscopy (DIF), and/or serology, with DIF being the most definitive. Perilesional skin is preferred for DIF, as lesional biopsies have been found to have higher rates of false negative results. The characteristic DIF finding diagnostic of DH is granular IgA deposits within dermal papillae, which was seen in this patient’s DIF.

Adequate treatment of DH can usually be accomplished with a combination of dapsone and a gluten-free diet. Initially, dapsone may be used for more immediate relief of associated pruritus and other bothersome symptoms. A strict gluten-free diet should be implemented as soon as possible, and dapsone can be tapered approximately 2-3 months after initiation as to avoid potential adverse effects with longterm treatment at higher doses.

The case and photo were submitted by Natasha Cowan, BS, University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, and Nick Celano, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Dermatitis herpetiformis

The primary lesions of DH are vesicles and papules in a grouped or “herpetic” formation. However, as these lesions are extremely pruritic, the primary lesions may be absent in many cases and instead replaced by secondary excoriations and erosions. DH has a very classic distribution pattern, particularly involving the bilateral extensor surfaces, buttocks, and scalp. Although some cases of oral DH have been reported, mucosal involvement is generally considered to be very rare.

Despite its strong association with underlying celiac disease, most patients with DH do not report any associated gastrointestinal symptoms. Those with DH may present with any variety of other autoimmune conditions, with hypothyroidism being the most common. Interestingly, patients with DH have been shown to be at an increased development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It is not certain whether adherence to a strict gluten-free diet reduces this risk in this population.

Diagnosis can be made with a proper clinical history and examination, tissue pathology, direct immunofluorescence microscopy (DIF), and/or serology, with DIF being the most definitive. Perilesional skin is preferred for DIF, as lesional biopsies have been found to have higher rates of false negative results. The characteristic DIF finding diagnostic of DH is granular IgA deposits within dermal papillae, which was seen in this patient’s DIF.

Adequate treatment of DH can usually be accomplished with a combination of dapsone and a gluten-free diet. Initially, dapsone may be used for more immediate relief of associated pruritus and other bothersome symptoms. A strict gluten-free diet should be implemented as soon as possible, and dapsone can be tapered approximately 2-3 months after initiation as to avoid potential adverse effects with longterm treatment at higher doses.

The case and photo were submitted by Natasha Cowan, BS, University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, and Nick Celano, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Dermatitis herpetiformis

The primary lesions of DH are vesicles and papules in a grouped or “herpetic” formation. However, as these lesions are extremely pruritic, the primary lesions may be absent in many cases and instead replaced by secondary excoriations and erosions. DH has a very classic distribution pattern, particularly involving the bilateral extensor surfaces, buttocks, and scalp. Although some cases of oral DH have been reported, mucosal involvement is generally considered to be very rare.

Despite its strong association with underlying celiac disease, most patients with DH do not report any associated gastrointestinal symptoms. Those with DH may present with any variety of other autoimmune conditions, with hypothyroidism being the most common. Interestingly, patients with DH have been shown to be at an increased development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It is not certain whether adherence to a strict gluten-free diet reduces this risk in this population.

Diagnosis can be made with a proper clinical history and examination, tissue pathology, direct immunofluorescence microscopy (DIF), and/or serology, with DIF being the most definitive. Perilesional skin is preferred for DIF, as lesional biopsies have been found to have higher rates of false negative results. The characteristic DIF finding diagnostic of DH is granular IgA deposits within dermal papillae, which was seen in this patient’s DIF.

Adequate treatment of DH can usually be accomplished with a combination of dapsone and a gluten-free diet. Initially, dapsone may be used for more immediate relief of associated pruritus and other bothersome symptoms. A strict gluten-free diet should be implemented as soon as possible, and dapsone can be tapered approximately 2-3 months after initiation as to avoid potential adverse effects with longterm treatment at higher doses.

The case and photo were submitted by Natasha Cowan, BS, University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, and Nick Celano, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Hepatitis B and C May Increase Risk of Parkinson’s Disease

Hepatitis B and C appear to increase the risk of later Parkinson’s disease, according to a report published online ahead of print March 29 in Neurology.

The etiology of Parkinson’s disease is complex, and several factors, including environmental toxins and head trauma, may increase the likelihood of the disorder. Two recent epidemiologic studies in Taiwan found an association between hepatitis C and Parkinson’s

To further explore that association, the investigators performed a retrospective cohort study using data from National Health Service hospitals across England for 1999 to 2011. They assessed the risk of Parkinson’s disease among 21,633 people with hepatitis B, 48,428 with hepatitis C, 6,225 with autoimmune hepatitis, 4,234 with chronic active hepatitis, 19,870 with HIV, and 6,132,124 control subjects with other disorders.

The risk of developing Parkinson’s disease was elevated following hospitalization for hepatitis B (relative risk [RR], 1.76) and hepatitis C (RR, 1.51). “These findings may be explained by a specific aspect of viral hepatitis (rather than a general hepatic inflammatory process or general use of antivirals), but whether this reflects shared disease mechanisms, shared genetic or environmental susceptibility, sequelae of viral hepatitis per se, or a consequence of treatment remains to be determined,” Dr. Pakpoor and her associates said.

The reason for this association is not yet known. “Neurotropic features of hepatitis C have been described previously and include the potential for cognitive impairment, independent of hepatic encephalopathy. Further, all essential hepatitis C virus receptors have been shown to be expressed on the brain microvascular endothelium … suggesting one mechanism by which the virus may affect the CNS,” they noted.

In addition, parkinsonism has been described as an adverse effect of treatment with interferon and ribavirin, which are commonly used in hepatitis C infection. Parkinsonism also is known to develop in association with liver cirrhosis. Cirrhosis status was not available for the members of this study cohort.

More studies are needed to confirm this association and verify that it is causal. Such research will also provide insight into pathophysiologic pathways of Parkinson’s disease, “which may be important to understanding the development of Parkinson’s disease more broadly,” Dr. Pakpoor and her associates said.

—Mary Ann Moon

Suggested Reading

Pakpoor J, Noyce A, Goldacre R, et al. Viral hepatitis and Parkinson disease: A national record-linkage study. Neurology. 2017 Mar 29 [Epub ahead of print].

Hepatitis B and C appear to increase the risk of later Parkinson’s disease, according to a report published online ahead of print March 29 in Neurology.

The etiology of Parkinson’s disease is complex, and several factors, including environmental toxins and head trauma, may increase the likelihood of the disorder. Two recent epidemiologic studies in Taiwan found an association between hepatitis C and Parkinson’s

To further explore that association, the investigators performed a retrospective cohort study using data from National Health Service hospitals across England for 1999 to 2011. They assessed the risk of Parkinson’s disease among 21,633 people with hepatitis B, 48,428 with hepatitis C, 6,225 with autoimmune hepatitis, 4,234 with chronic active hepatitis, 19,870 with HIV, and 6,132,124 control subjects with other disorders.

The risk of developing Parkinson’s disease was elevated following hospitalization for hepatitis B (relative risk [RR], 1.76) and hepatitis C (RR, 1.51). “These findings may be explained by a specific aspect of viral hepatitis (rather than a general hepatic inflammatory process or general use of antivirals), but whether this reflects shared disease mechanisms, shared genetic or environmental susceptibility, sequelae of viral hepatitis per se, or a consequence of treatment remains to be determined,” Dr. Pakpoor and her associates said.

The reason for this association is not yet known. “Neurotropic features of hepatitis C have been described previously and include the potential for cognitive impairment, independent of hepatic encephalopathy. Further, all essential hepatitis C virus receptors have been shown to be expressed on the brain microvascular endothelium … suggesting one mechanism by which the virus may affect the CNS,” they noted.

In addition, parkinsonism has been described as an adverse effect of treatment with interferon and ribavirin, which are commonly used in hepatitis C infection. Parkinsonism also is known to develop in association with liver cirrhosis. Cirrhosis status was not available for the members of this study cohort.

More studies are needed to confirm this association and verify that it is causal. Such research will also provide insight into pathophysiologic pathways of Parkinson’s disease, “which may be important to understanding the development of Parkinson’s disease more broadly,” Dr. Pakpoor and her associates said.

—Mary Ann Moon

Suggested Reading

Pakpoor J, Noyce A, Goldacre R, et al. Viral hepatitis and Parkinson disease: A national record-linkage study. Neurology. 2017 Mar 29 [Epub ahead of print].

Hepatitis B and C appear to increase the risk of later Parkinson’s disease, according to a report published online ahead of print March 29 in Neurology.

The etiology of Parkinson’s disease is complex, and several factors, including environmental toxins and head trauma, may increase the likelihood of the disorder. Two recent epidemiologic studies in Taiwan found an association between hepatitis C and Parkinson’s

To further explore that association, the investigators performed a retrospective cohort study using data from National Health Service hospitals across England for 1999 to 2011. They assessed the risk of Parkinson’s disease among 21,633 people with hepatitis B, 48,428 with hepatitis C, 6,225 with autoimmune hepatitis, 4,234 with chronic active hepatitis, 19,870 with HIV, and 6,132,124 control subjects with other disorders.

The risk of developing Parkinson’s disease was elevated following hospitalization for hepatitis B (relative risk [RR], 1.76) and hepatitis C (RR, 1.51). “These findings may be explained by a specific aspect of viral hepatitis (rather than a general hepatic inflammatory process or general use of antivirals), but whether this reflects shared disease mechanisms, shared genetic or environmental susceptibility, sequelae of viral hepatitis per se, or a consequence of treatment remains to be determined,” Dr. Pakpoor and her associates said.

The reason for this association is not yet known. “Neurotropic features of hepatitis C have been described previously and include the potential for cognitive impairment, independent of hepatic encephalopathy. Further, all essential hepatitis C virus receptors have been shown to be expressed on the brain microvascular endothelium … suggesting one mechanism by which the virus may affect the CNS,” they noted.

In addition, parkinsonism has been described as an adverse effect of treatment with interferon and ribavirin, which are commonly used in hepatitis C infection. Parkinsonism also is known to develop in association with liver cirrhosis. Cirrhosis status was not available for the members of this study cohort.

More studies are needed to confirm this association and verify that it is causal. Such research will also provide insight into pathophysiologic pathways of Parkinson’s disease, “which may be important to understanding the development of Parkinson’s disease more broadly,” Dr. Pakpoor and her associates said.

—Mary Ann Moon

Suggested Reading

Pakpoor J, Noyce A, Goldacre R, et al. Viral hepatitis and Parkinson disease: A national record-linkage study. Neurology. 2017 Mar 29 [Epub ahead of print].

Decrease in Blood Pressure During Thrombectomy Under General Anesthesia Influences Outcome

HOUSTON—Among patients who undergo thrombectomy under general anesthesia, a decrease in blood pressure during treatment is associated with worse functional outcome, according to research presented at the International Stroke Conference 2017. The data suggest the importance of stringent blood pressure targets for improving outcome in patients treated under general anesthesia, said Kilian M. Treurniet, MD, a physician-researcher at the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

The MR CLEAN trial indicated that intra-arterial treatment, including mechanical thrombectomy, is an effective and safe treatment for acute ischemic stroke. The investigators noticed, however, a loss of treatment effect when the procedure was performed on patients under general anesthesia. The researchers hypothesized that decreases in blood pressure might explain this loss of effect, said Dr. Treurniet.

To test this hypothesis, he and his colleagues performed a post hoc analysis of the MR CLEAN data to examine whether decreases from baseline in blood pressure during intervention under general anesthesia were associated with functional outcome. Patients were included in the analysis if their baseline blood pressure had been recorded and if they had regular blood pressure measurements during induction and maintenance anesthesia. The investigators focused on mean arterial pressure on the presumption that it most closely approximates cerebral perfusion pressure. The primary outcome was modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at 90 days. The investigators performed a primary analysis before adjusting the data for known prognostic factors such as NIH Stroke Scale score and occlusion location.

In all, 60 patients treated under general anesthesia were included in the analysis. Age, sex, and occlusion location were similarly distributed in this population, compared with the larger MR CLEAN population. The majority of patients received propofol as an induction anesthetic and sevoflurane as a maintenance anesthetic.

At baseline, patients’ median systolic blood pressure was 140 mm Hg, and median mean arterial pressure was 100 mm Hg. The average decline in mean arterial pressure during the intervention, compared with baseline blood pressure, was 17 mm Hg. Patients with greater decreases in blood pressure had higher mRS scores at 90 days. Few patients in the analysis had low mRS scores, however, which makes the estimation of the association less precise, said Dr. Treurniet.

In the primary analysis, average mean arterial pressure during the intervention and lowest mean arterial pressure during the intervention were significantly associated with functional outcome. After adjustment, the association between average mean arterial pressure and functional outcome remained significant.

One of the limitations of the analysis is that the data came from nine centers and thus were heterogeneous. Blood pressure was not measured with the same frequency at every center. In addition, the sample size was small, and patients were not randomized to general anesthesia or to local anesthesia. Baseline blood pressure was based on a single manual measurement that could incorporate variability. Finally, the centers used invasive and noninvasive measurements during the procedure, and this heterogeneity could have influenced the results, said Dr. Treurniet.

“A decrease in mean arterial pressure during intervention under general anesthesia is associated with worse outcome in our study,” he added. “It might be that blood pressure management in those patients is of the utmost importance. We are looking forward to possible post hoc analyses of the SIESTA trial on this topic, and the upcoming results of the GOLIATH trial for [more] information.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Simonsen CZ, Sørensen LH, Juul N, et al. Anesthetic strategy during endovascular therapy: General anesthesia or conscious sedation? (GOLIATH - General or Local Anesthesia in Intra Arterial Therapy) A single-center randomized trial. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(9):1045-1052.

Sivasankar C, Stiefel M, Miano TA, et al. Anesthetic variation and potential impact of anesthetics used during endovascular management of acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8(11):1101-1106.

Treurniet KM, Berkhemer OA, Immink RV, et al.

Whalin MK, Lopian S, Wyatt K, et al. Dexmedetomidine: a safe alternative to general anesthesia for endovascular stroke treatment. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014;6(4):270-275.

HOUSTON—Among patients who undergo thrombectomy under general anesthesia, a decrease in blood pressure during treatment is associated with worse functional outcome, according to research presented at the International Stroke Conference 2017. The data suggest the importance of stringent blood pressure targets for improving outcome in patients treated under general anesthesia, said Kilian M. Treurniet, MD, a physician-researcher at the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

The MR CLEAN trial indicated that intra-arterial treatment, including mechanical thrombectomy, is an effective and safe treatment for acute ischemic stroke. The investigators noticed, however, a loss of treatment effect when the procedure was performed on patients under general anesthesia. The researchers hypothesized that decreases in blood pressure might explain this loss of effect, said Dr. Treurniet.

To test this hypothesis, he and his colleagues performed a post hoc analysis of the MR CLEAN data to examine whether decreases from baseline in blood pressure during intervention under general anesthesia were associated with functional outcome. Patients were included in the analysis if their baseline blood pressure had been recorded and if they had regular blood pressure measurements during induction and maintenance anesthesia. The investigators focused on mean arterial pressure on the presumption that it most closely approximates cerebral perfusion pressure. The primary outcome was modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at 90 days. The investigators performed a primary analysis before adjusting the data for known prognostic factors such as NIH Stroke Scale score and occlusion location.

In all, 60 patients treated under general anesthesia were included in the analysis. Age, sex, and occlusion location were similarly distributed in this population, compared with the larger MR CLEAN population. The majority of patients received propofol as an induction anesthetic and sevoflurane as a maintenance anesthetic.

At baseline, patients’ median systolic blood pressure was 140 mm Hg, and median mean arterial pressure was 100 mm Hg. The average decline in mean arterial pressure during the intervention, compared with baseline blood pressure, was 17 mm Hg. Patients with greater decreases in blood pressure had higher mRS scores at 90 days. Few patients in the analysis had low mRS scores, however, which makes the estimation of the association less precise, said Dr. Treurniet.

In the primary analysis, average mean arterial pressure during the intervention and lowest mean arterial pressure during the intervention were significantly associated with functional outcome. After adjustment, the association between average mean arterial pressure and functional outcome remained significant.

One of the limitations of the analysis is that the data came from nine centers and thus were heterogeneous. Blood pressure was not measured with the same frequency at every center. In addition, the sample size was small, and patients were not randomized to general anesthesia or to local anesthesia. Baseline blood pressure was based on a single manual measurement that could incorporate variability. Finally, the centers used invasive and noninvasive measurements during the procedure, and this heterogeneity could have influenced the results, said Dr. Treurniet.

“A decrease in mean arterial pressure during intervention under general anesthesia is associated with worse outcome in our study,” he added. “It might be that blood pressure management in those patients is of the utmost importance. We are looking forward to possible post hoc analyses of the SIESTA trial on this topic, and the upcoming results of the GOLIATH trial for [more] information.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Simonsen CZ, Sørensen LH, Juul N, et al. Anesthetic strategy during endovascular therapy: General anesthesia or conscious sedation? (GOLIATH - General or Local Anesthesia in Intra Arterial Therapy) A single-center randomized trial. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(9):1045-1052.

Sivasankar C, Stiefel M, Miano TA, et al. Anesthetic variation and potential impact of anesthetics used during endovascular management of acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8(11):1101-1106.

Treurniet KM, Berkhemer OA, Immink RV, et al.

Whalin MK, Lopian S, Wyatt K, et al. Dexmedetomidine: a safe alternative to general anesthesia for endovascular stroke treatment. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014;6(4):270-275.

HOUSTON—Among patients who undergo thrombectomy under general anesthesia, a decrease in blood pressure during treatment is associated with worse functional outcome, according to research presented at the International Stroke Conference 2017. The data suggest the importance of stringent blood pressure targets for improving outcome in patients treated under general anesthesia, said Kilian M. Treurniet, MD, a physician-researcher at the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

The MR CLEAN trial indicated that intra-arterial treatment, including mechanical thrombectomy, is an effective and safe treatment for acute ischemic stroke. The investigators noticed, however, a loss of treatment effect when the procedure was performed on patients under general anesthesia. The researchers hypothesized that decreases in blood pressure might explain this loss of effect, said Dr. Treurniet.

To test this hypothesis, he and his colleagues performed a post hoc analysis of the MR CLEAN data to examine whether decreases from baseline in blood pressure during intervention under general anesthesia were associated with functional outcome. Patients were included in the analysis if their baseline blood pressure had been recorded and if they had regular blood pressure measurements during induction and maintenance anesthesia. The investigators focused on mean arterial pressure on the presumption that it most closely approximates cerebral perfusion pressure. The primary outcome was modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at 90 days. The investigators performed a primary analysis before adjusting the data for known prognostic factors such as NIH Stroke Scale score and occlusion location.

In all, 60 patients treated under general anesthesia were included in the analysis. Age, sex, and occlusion location were similarly distributed in this population, compared with the larger MR CLEAN population. The majority of patients received propofol as an induction anesthetic and sevoflurane as a maintenance anesthetic.

At baseline, patients’ median systolic blood pressure was 140 mm Hg, and median mean arterial pressure was 100 mm Hg. The average decline in mean arterial pressure during the intervention, compared with baseline blood pressure, was 17 mm Hg. Patients with greater decreases in blood pressure had higher mRS scores at 90 days. Few patients in the analysis had low mRS scores, however, which makes the estimation of the association less precise, said Dr. Treurniet.

In the primary analysis, average mean arterial pressure during the intervention and lowest mean arterial pressure during the intervention were significantly associated with functional outcome. After adjustment, the association between average mean arterial pressure and functional outcome remained significant.

One of the limitations of the analysis is that the data came from nine centers and thus were heterogeneous. Blood pressure was not measured with the same frequency at every center. In addition, the sample size was small, and patients were not randomized to general anesthesia or to local anesthesia. Baseline blood pressure was based on a single manual measurement that could incorporate variability. Finally, the centers used invasive and noninvasive measurements during the procedure, and this heterogeneity could have influenced the results, said Dr. Treurniet.

“A decrease in mean arterial pressure during intervention under general anesthesia is associated with worse outcome in our study,” he added. “It might be that blood pressure management in those patients is of the utmost importance. We are looking forward to possible post hoc analyses of the SIESTA trial on this topic, and the upcoming results of the GOLIATH trial for [more] information.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Simonsen CZ, Sørensen LH, Juul N, et al. Anesthetic strategy during endovascular therapy: General anesthesia or conscious sedation? (GOLIATH - General or Local Anesthesia in Intra Arterial Therapy) A single-center randomized trial. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(9):1045-1052.

Sivasankar C, Stiefel M, Miano TA, et al. Anesthetic variation and potential impact of anesthetics used during endovascular management of acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8(11):1101-1106.

Treurniet KM, Berkhemer OA, Immink RV, et al.

Whalin MK, Lopian S, Wyatt K, et al. Dexmedetomidine: a safe alternative to general anesthesia for endovascular stroke treatment. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014;6(4):270-275.

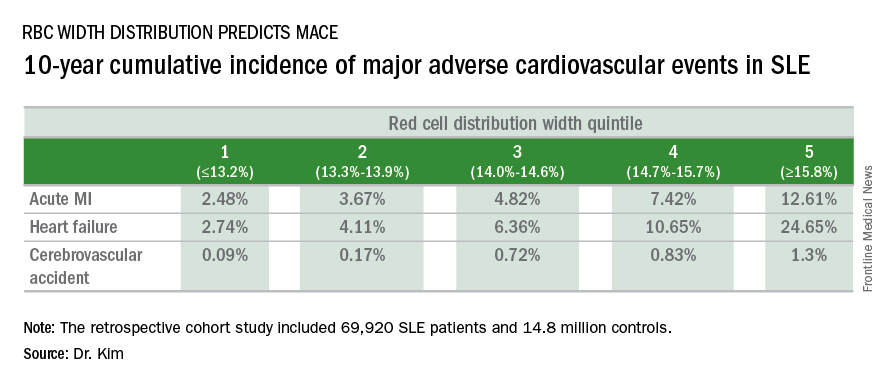

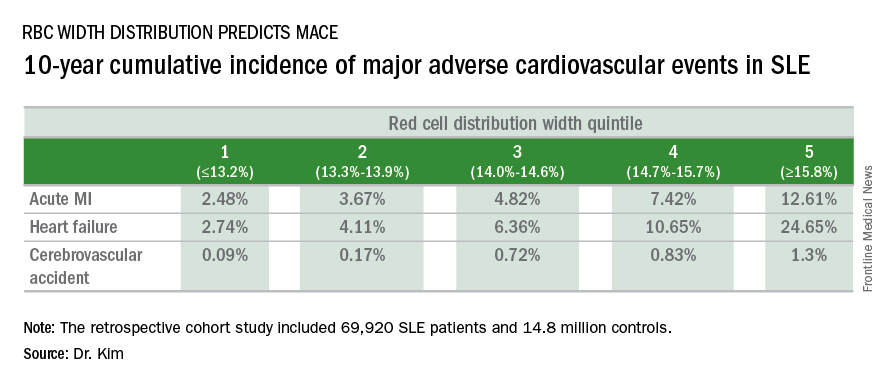

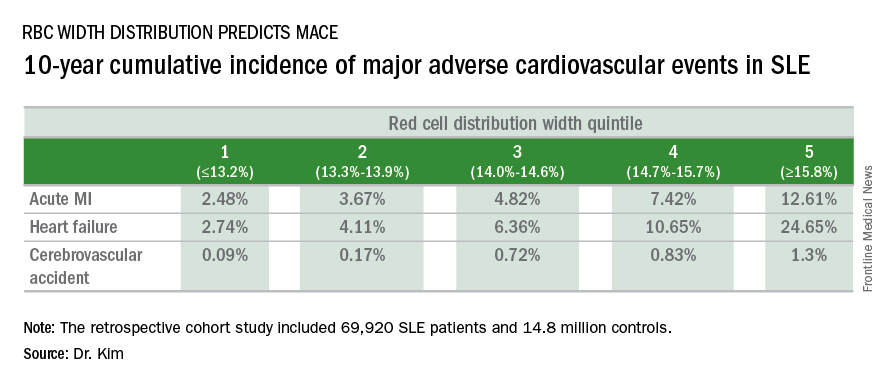

Refining SLE cardiovascular risk estimation

WASHINGTON – Red blood cell distribution width provides a novel tool for cardiovascular risk stratification in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Chang H. Kim, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In a retrospective cohort study of nearly 70,000 patients with SLE, the 10-year rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) rose stepwise according to quintile of red cell distribution width (RDW) from 5.3% in patients with an RDW of 13.2% or less to 38.6% in those with an RDW of 15.8% or greater, according to Dr. Kim of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

He utilized the Explorys database to determine the 10-year cumulative incidence of MACE – defined as acute MI, heart failure, or cerebrovascular accident – during 2007-2016 in 69,920 patients with SLE and 14,825,240 controls. Explorys is an 8-year-old Cleveland-based company that maintains a health care database incorporating 26 health care systems across the United States with nearly 50 million patients. It is part of IBM Watson Health.

The MACE rate in patients with SLE displayed a graded increase in association with RDW quintile as measured in a routine CBC. (See table.) MACE rates were significantly higher in male than female SLE patients, but the graded relationship between RDW quintile and 10-year incidence of MACE persisted after adjustment for gender and the presence of anemia.

A graded association between RDW quintile and MACE also was noted in the control group of nearly 15 million individuals, but the absolute incidence of MACE in the non-SLE controls was far lower.

Dr. Kim reported having no financial conflicts regarding this unfunded study.

WASHINGTON – Red blood cell distribution width provides a novel tool for cardiovascular risk stratification in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Chang H. Kim, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In a retrospective cohort study of nearly 70,000 patients with SLE, the 10-year rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) rose stepwise according to quintile of red cell distribution width (RDW) from 5.3% in patients with an RDW of 13.2% or less to 38.6% in those with an RDW of 15.8% or greater, according to Dr. Kim of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

He utilized the Explorys database to determine the 10-year cumulative incidence of MACE – defined as acute MI, heart failure, or cerebrovascular accident – during 2007-2016 in 69,920 patients with SLE and 14,825,240 controls. Explorys is an 8-year-old Cleveland-based company that maintains a health care database incorporating 26 health care systems across the United States with nearly 50 million patients. It is part of IBM Watson Health.

The MACE rate in patients with SLE displayed a graded increase in association with RDW quintile as measured in a routine CBC. (See table.) MACE rates were significantly higher in male than female SLE patients, but the graded relationship between RDW quintile and 10-year incidence of MACE persisted after adjustment for gender and the presence of anemia.

A graded association between RDW quintile and MACE also was noted in the control group of nearly 15 million individuals, but the absolute incidence of MACE in the non-SLE controls was far lower.

Dr. Kim reported having no financial conflicts regarding this unfunded study.

WASHINGTON – Red blood cell distribution width provides a novel tool for cardiovascular risk stratification in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Chang H. Kim, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In a retrospective cohort study of nearly 70,000 patients with SLE, the 10-year rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) rose stepwise according to quintile of red cell distribution width (RDW) from 5.3% in patients with an RDW of 13.2% or less to 38.6% in those with an RDW of 15.8% or greater, according to Dr. Kim of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

He utilized the Explorys database to determine the 10-year cumulative incidence of MACE – defined as acute MI, heart failure, or cerebrovascular accident – during 2007-2016 in 69,920 patients with SLE and 14,825,240 controls. Explorys is an 8-year-old Cleveland-based company that maintains a health care database incorporating 26 health care systems across the United States with nearly 50 million patients. It is part of IBM Watson Health.

The MACE rate in patients with SLE displayed a graded increase in association with RDW quintile as measured in a routine CBC. (See table.) MACE rates were significantly higher in male than female SLE patients, but the graded relationship between RDW quintile and 10-year incidence of MACE persisted after adjustment for gender and the presence of anemia.

A graded association between RDW quintile and MACE also was noted in the control group of nearly 15 million individuals, but the absolute incidence of MACE in the non-SLE controls was far lower.

Dr. Kim reported having no financial conflicts regarding this unfunded study.

AT ACC 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Systemic lupus erythematosus patients in the top quintile of RBC distribution width had a 10-year incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events of 39%.

Data source: This retrospective cohort study included nearly 70,000 SLE patients and 14.8 million controls.

Disclosures: The presenter reported no financial conflicts with regard to this unfunded study.

Parents rate telepediatric experience as better than office visits

Three-quarters of parents who have used telemedicine services for their children say the experience was better than an in-person office visit, according to a new study.

The analysis, released April 23, 2017, by Nemours Children’s Health System operating in five states, surveyed 500 child caregivers between February 15 and 20 about their awareness and usage of telemedicine services for their children aged 17 years and younger (mean age 10 years). Of caregivers surveyed, 15% had tried telemedicine services for their children, while another 61% reported they plan to use telemedicine in the next year for their children’s medical care, according to the study. Eight percent of caregivers did not plan to use telemedicine, and 31% of those surveyed were unsure.

Of child caregivers who have used telemedicine, 75% of reported their telemedicine experience was better than an in-person visit, according to the survey. Convenience, after-hours accessibility, and immediacy were the top three reasons caregivers sought an online visit for their child. Compared with a similar survey conducted by Nemours in 2014, parents’ use of telemedicine for their children has grown by 125% and awareness of the practice has increased by 88%, the study found.

The overall takeaway is that parents are using telemedicine because of its ease and accessibility and they’re having satisfactory experiences with the technology, said Shayan Vyas, MD, a pediatrician based in Nemours’ Orlando location and director of telemedicine for Nemours Children’s Hospital.

“Parents are citing telemedicine because of convenience and that’s true for other industries that have gone mobile,” Dr. Vyas said in an interview. “We no longer hail a cab at the intersection, we use our smartphones. We now use Amazon and other companies to order diapers and other everyday items. ... More and more, patients are driving telemedicine more than the systems or the providers.”

Caregivers surveyed said they are most willing to use telehealth services for cold and flu (58%), pink eye (51%), and rashes (48%) as well as well-child visits (41%). However, parents and caregivers were hesitant to use telemedicine for chronic conditions and reported they would likely never consider telehealth services for diabetes (53%), asthma (43%), ear pain (37%), and ADHD (36%).

The findings are expected because there are limitations for providers when it comes to treating some conditions and chronic diseases with telemedicine, Dr. Vyas said. He also stressed that telemedicine should not be used to replace the medical home for children.

“We’re working really hard to ensure there’s great pediatric care online and that the medical home stays intact,” he said. “We don’t want telemedicine to become the wild wild west of retail clinics where children are getting care from providers they don’t know or who are not in touch with their primary care world.”

Nemours has incorporated telemedicine throughout its health system with direct-to-consumer care for acute, chronic, and postsurgical appointments. The telehealth program, called Nemours CareConnect, is a 24/7, on-demand pediatric service that provides access to Nemours pediatricians through smartphones, tablets, or computers. In addition, Nemours CareConnect is used to bring pediatric specialists into affiliated community hospitals.

“At Nemours, we’ve seen how telemedicine can positively impact patients’ lives,” Dr. Vyas said. “The overwhelmingly positive response we’ve seen from parents who are early adopters of telemedicine really reinforces the feasibility of online doctor visits and sets the stage for real change in the way health care is delivered.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Three-quarters of parents who have used telemedicine services for their children say the experience was better than an in-person office visit, according to a new study.

The analysis, released April 23, 2017, by Nemours Children’s Health System operating in five states, surveyed 500 child caregivers between February 15 and 20 about their awareness and usage of telemedicine services for their children aged 17 years and younger (mean age 10 years). Of caregivers surveyed, 15% had tried telemedicine services for their children, while another 61% reported they plan to use telemedicine in the next year for their children’s medical care, according to the study. Eight percent of caregivers did not plan to use telemedicine, and 31% of those surveyed were unsure.

Of child caregivers who have used telemedicine, 75% of reported their telemedicine experience was better than an in-person visit, according to the survey. Convenience, after-hours accessibility, and immediacy were the top three reasons caregivers sought an online visit for their child. Compared with a similar survey conducted by Nemours in 2014, parents’ use of telemedicine for their children has grown by 125% and awareness of the practice has increased by 88%, the study found.

The overall takeaway is that parents are using telemedicine because of its ease and accessibility and they’re having satisfactory experiences with the technology, said Shayan Vyas, MD, a pediatrician based in Nemours’ Orlando location and director of telemedicine for Nemours Children’s Hospital.

“Parents are citing telemedicine because of convenience and that’s true for other industries that have gone mobile,” Dr. Vyas said in an interview. “We no longer hail a cab at the intersection, we use our smartphones. We now use Amazon and other companies to order diapers and other everyday items. ... More and more, patients are driving telemedicine more than the systems or the providers.”

Caregivers surveyed said they are most willing to use telehealth services for cold and flu (58%), pink eye (51%), and rashes (48%) as well as well-child visits (41%). However, parents and caregivers were hesitant to use telemedicine for chronic conditions and reported they would likely never consider telehealth services for diabetes (53%), asthma (43%), ear pain (37%), and ADHD (36%).

The findings are expected because there are limitations for providers when it comes to treating some conditions and chronic diseases with telemedicine, Dr. Vyas said. He also stressed that telemedicine should not be used to replace the medical home for children.

“We’re working really hard to ensure there’s great pediatric care online and that the medical home stays intact,” he said. “We don’t want telemedicine to become the wild wild west of retail clinics where children are getting care from providers they don’t know or who are not in touch with their primary care world.”

Nemours has incorporated telemedicine throughout its health system with direct-to-consumer care for acute, chronic, and postsurgical appointments. The telehealth program, called Nemours CareConnect, is a 24/7, on-demand pediatric service that provides access to Nemours pediatricians through smartphones, tablets, or computers. In addition, Nemours CareConnect is used to bring pediatric specialists into affiliated community hospitals.

“At Nemours, we’ve seen how telemedicine can positively impact patients’ lives,” Dr. Vyas said. “The overwhelmingly positive response we’ve seen from parents who are early adopters of telemedicine really reinforces the feasibility of online doctor visits and sets the stage for real change in the way health care is delivered.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Three-quarters of parents who have used telemedicine services for their children say the experience was better than an in-person office visit, according to a new study.

The analysis, released April 23, 2017, by Nemours Children’s Health System operating in five states, surveyed 500 child caregivers between February 15 and 20 about their awareness and usage of telemedicine services for their children aged 17 years and younger (mean age 10 years). Of caregivers surveyed, 15% had tried telemedicine services for their children, while another 61% reported they plan to use telemedicine in the next year for their children’s medical care, according to the study. Eight percent of caregivers did not plan to use telemedicine, and 31% of those surveyed were unsure.

Of child caregivers who have used telemedicine, 75% of reported their telemedicine experience was better than an in-person visit, according to the survey. Convenience, after-hours accessibility, and immediacy were the top three reasons caregivers sought an online visit for their child. Compared with a similar survey conducted by Nemours in 2014, parents’ use of telemedicine for their children has grown by 125% and awareness of the practice has increased by 88%, the study found.

The overall takeaway is that parents are using telemedicine because of its ease and accessibility and they’re having satisfactory experiences with the technology, said Shayan Vyas, MD, a pediatrician based in Nemours’ Orlando location and director of telemedicine for Nemours Children’s Hospital.

“Parents are citing telemedicine because of convenience and that’s true for other industries that have gone mobile,” Dr. Vyas said in an interview. “We no longer hail a cab at the intersection, we use our smartphones. We now use Amazon and other companies to order diapers and other everyday items. ... More and more, patients are driving telemedicine more than the systems or the providers.”

Caregivers surveyed said they are most willing to use telehealth services for cold and flu (58%), pink eye (51%), and rashes (48%) as well as well-child visits (41%). However, parents and caregivers were hesitant to use telemedicine for chronic conditions and reported they would likely never consider telehealth services for diabetes (53%), asthma (43%), ear pain (37%), and ADHD (36%).

The findings are expected because there are limitations for providers when it comes to treating some conditions and chronic diseases with telemedicine, Dr. Vyas said. He also stressed that telemedicine should not be used to replace the medical home for children.

“We’re working really hard to ensure there’s great pediatric care online and that the medical home stays intact,” he said. “We don’t want telemedicine to become the wild wild west of retail clinics where children are getting care from providers they don’t know or who are not in touch with their primary care world.”

Nemours has incorporated telemedicine throughout its health system with direct-to-consumer care for acute, chronic, and postsurgical appointments. The telehealth program, called Nemours CareConnect, is a 24/7, on-demand pediatric service that provides access to Nemours pediatricians through smartphones, tablets, or computers. In addition, Nemours CareConnect is used to bring pediatric specialists into affiliated community hospitals.

“At Nemours, we’ve seen how telemedicine can positively impact patients’ lives,” Dr. Vyas said. “The overwhelmingly positive response we’ve seen from parents who are early adopters of telemedicine really reinforces the feasibility of online doctor visits and sets the stage for real change in the way health care is delivered.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Parkinson’s patients’ quality of life improves after deep brain stimulation

BOSTON– Early results from an industry-funded registry of Parkinson’s disease patients who underwent deep brain stimulation (DBS) reveal that their quality-of-life scores grew by 22% at 6 months.

Patients, their caregivers, and their clinicians all overwhelmingly reported improvement.

The study, which examined two types of technology that are not approved in the United States, aims to fill a gap in DBS research: How do patients fare in normal conditions – “real life” – outside of clinical trials?

While DBS has been widely used for many years, “much of the available information is from controlled trials that usually select the best possible patients – relatively young and in the condition to go through a clinical trial. There’s less information about people who may not be in the best possible shape,” said Michele Tagliati, MD, professor and director of movement disorders at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He did not take part in the study but is familiar with its findings.

The study’s lead author, Günther Deuschl, MD, PhD, of University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, released preliminary findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The researchers have enrolled 203 patients who were treated with Boston Scientific’s Vercise DBS system, which is not approved for use in the United States. The researchers plan to track patients for 3 years.

“This is the first such industry-sponsored registry, which addresses a need in the field to track DBS practice and outcomes across multiple centers,” said Mark Richardson, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of epilepsy and movement disorders surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. He did not take part in the study but is familiar with its findings.

The average age of participants is 59 years, which Dr. Deuschl said is a bit younger than many other studies, and 69% are male. Eighty-five serious adverse events were reported in 52 patients; 57 were not linked to the procedure. One patient died of a surgery-related hematoma.

At 6 months, patients reported a 22% improvement (P less than .0001) on the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39), Dr. Deuschl said, and that level was sustained at 1 year.

That level of improvement is significant, Dr. Richardson said in an interview.

“Previous randomized, controlled trials have shown that patients who are candidates for DBS but who continue medical management alone are most likely to have no improvement at all on any quality of life measures,” he said. In addition, “6 months is fairly short, and some patients likely have not reached stable stimulation programming and effectiveness.”

The researchers also reported that more than 90% of patients, their clinicians, and their caregivers reported improvement.

This kind of study is valuable in light of skepticism about DBS, which is used to treat patients who do not respond to medication, Dr. Tagliati noted.

“Despite 15 years of [Food and Drug Administration] approval, there is still some form of resistance out there in referring patients with Parkinson’s at the right time when they can still fully benefit from the procedure,” he said. “Registries have this potential great benefit in terms of awareness and reassuring people.”

As for the high rating of improvement, Dr. Tagliati said it reflects what he sees in the clinic.

“Barring complications, we have very substantial satisfaction in our patients, definitely in the short term after DBS,” he said. “Over the long term, the picture is more difficult to read.”

Dr. Deuschl said researchers would like to add hundreds more patients to the study, and they hope to gain data about the differences between the results from standard and directional-lead DBS systems.

Boston Scientific funded the study, and some of the authors work for the company.

Dr. Richardson reported receiving research grant funding from Medtronic. Dr. Tagliati reported receiving funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and all DBS manufacturers, and his clinic is an investigational center for the Vercise DBS system. Dr. Deuschl reported receiving consulting fees from Boston Scientific, grant funding from Medtronic, lecture fees from Almirall and Novartis, and royalties from Thieme Publishers.

BOSTON– Early results from an industry-funded registry of Parkinson’s disease patients who underwent deep brain stimulation (DBS) reveal that their quality-of-life scores grew by 22% at 6 months.

Patients, their caregivers, and their clinicians all overwhelmingly reported improvement.

The study, which examined two types of technology that are not approved in the United States, aims to fill a gap in DBS research: How do patients fare in normal conditions – “real life” – outside of clinical trials?

While DBS has been widely used for many years, “much of the available information is from controlled trials that usually select the best possible patients – relatively young and in the condition to go through a clinical trial. There’s less information about people who may not be in the best possible shape,” said Michele Tagliati, MD, professor and director of movement disorders at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He did not take part in the study but is familiar with its findings.

The study’s lead author, Günther Deuschl, MD, PhD, of University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, released preliminary findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The researchers have enrolled 203 patients who were treated with Boston Scientific’s Vercise DBS system, which is not approved for use in the United States. The researchers plan to track patients for 3 years.

“This is the first such industry-sponsored registry, which addresses a need in the field to track DBS practice and outcomes across multiple centers,” said Mark Richardson, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of epilepsy and movement disorders surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. He did not take part in the study but is familiar with its findings.

The average age of participants is 59 years, which Dr. Deuschl said is a bit younger than many other studies, and 69% are male. Eighty-five serious adverse events were reported in 52 patients; 57 were not linked to the procedure. One patient died of a surgery-related hematoma.

At 6 months, patients reported a 22% improvement (P less than .0001) on the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39), Dr. Deuschl said, and that level was sustained at 1 year.

That level of improvement is significant, Dr. Richardson said in an interview.

“Previous randomized, controlled trials have shown that patients who are candidates for DBS but who continue medical management alone are most likely to have no improvement at all on any quality of life measures,” he said. In addition, “6 months is fairly short, and some patients likely have not reached stable stimulation programming and effectiveness.”

The researchers also reported that more than 90% of patients, their clinicians, and their caregivers reported improvement.

This kind of study is valuable in light of skepticism about DBS, which is used to treat patients who do not respond to medication, Dr. Tagliati noted.

“Despite 15 years of [Food and Drug Administration] approval, there is still some form of resistance out there in referring patients with Parkinson’s at the right time when they can still fully benefit from the procedure,” he said. “Registries have this potential great benefit in terms of awareness and reassuring people.”

As for the high rating of improvement, Dr. Tagliati said it reflects what he sees in the clinic.

“Barring complications, we have very substantial satisfaction in our patients, definitely in the short term after DBS,” he said. “Over the long term, the picture is more difficult to read.”

Dr. Deuschl said researchers would like to add hundreds more patients to the study, and they hope to gain data about the differences between the results from standard and directional-lead DBS systems.

Boston Scientific funded the study, and some of the authors work for the company.

Dr. Richardson reported receiving research grant funding from Medtronic. Dr. Tagliati reported receiving funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and all DBS manufacturers, and his clinic is an investigational center for the Vercise DBS system. Dr. Deuschl reported receiving consulting fees from Boston Scientific, grant funding from Medtronic, lecture fees from Almirall and Novartis, and royalties from Thieme Publishers.

BOSTON– Early results from an industry-funded registry of Parkinson’s disease patients who underwent deep brain stimulation (DBS) reveal that their quality-of-life scores grew by 22% at 6 months.

Patients, their caregivers, and their clinicians all overwhelmingly reported improvement.

The study, which examined two types of technology that are not approved in the United States, aims to fill a gap in DBS research: How do patients fare in normal conditions – “real life” – outside of clinical trials?

While DBS has been widely used for many years, “much of the available information is from controlled trials that usually select the best possible patients – relatively young and in the condition to go through a clinical trial. There’s less information about people who may not be in the best possible shape,” said Michele Tagliati, MD, professor and director of movement disorders at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He did not take part in the study but is familiar with its findings.

The study’s lead author, Günther Deuschl, MD, PhD, of University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, released preliminary findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The researchers have enrolled 203 patients who were treated with Boston Scientific’s Vercise DBS system, which is not approved for use in the United States. The researchers plan to track patients for 3 years.

“This is the first such industry-sponsored registry, which addresses a need in the field to track DBS practice and outcomes across multiple centers,” said Mark Richardson, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of epilepsy and movement disorders surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. He did not take part in the study but is familiar with its findings.

The average age of participants is 59 years, which Dr. Deuschl said is a bit younger than many other studies, and 69% are male. Eighty-five serious adverse events were reported in 52 patients; 57 were not linked to the procedure. One patient died of a surgery-related hematoma.

At 6 months, patients reported a 22% improvement (P less than .0001) on the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39), Dr. Deuschl said, and that level was sustained at 1 year.

That level of improvement is significant, Dr. Richardson said in an interview.

“Previous randomized, controlled trials have shown that patients who are candidates for DBS but who continue medical management alone are most likely to have no improvement at all on any quality of life measures,” he said. In addition, “6 months is fairly short, and some patients likely have not reached stable stimulation programming and effectiveness.”

The researchers also reported that more than 90% of patients, their clinicians, and their caregivers reported improvement.

This kind of study is valuable in light of skepticism about DBS, which is used to treat patients who do not respond to medication, Dr. Tagliati noted.

“Despite 15 years of [Food and Drug Administration] approval, there is still some form of resistance out there in referring patients with Parkinson’s at the right time when they can still fully benefit from the procedure,” he said. “Registries have this potential great benefit in terms of awareness and reassuring people.”

As for the high rating of improvement, Dr. Tagliati said it reflects what he sees in the clinic.

“Barring complications, we have very substantial satisfaction in our patients, definitely in the short term after DBS,” he said. “Over the long term, the picture is more difficult to read.”

Dr. Deuschl said researchers would like to add hundreds more patients to the study, and they hope to gain data about the differences between the results from standard and directional-lead DBS systems.

Boston Scientific funded the study, and some of the authors work for the company.

Dr. Richardson reported receiving research grant funding from Medtronic. Dr. Tagliati reported receiving funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and all DBS manufacturers, and his clinic is an investigational center for the Vercise DBS system. Dr. Deuschl reported receiving consulting fees from Boston Scientific, grant funding from Medtronic, lecture fees from Almirall and Novartis, and royalties from Thieme Publishers.

Flow Diverters Successfully Treat Small, Unruptured Aneurysms

HOUSTON—A flow-diverter device can treat small to medium-sized unruptured aneurysms safely and effectively, according to research presented at the International Stroke Conference 2017. The device has a high rate of aneurysm occlusion and is associated with no aneurysm rupture or recurrence at one year. The treatment also entails low rates of morbidity and mortality at one year.

One flow diverter is the Pipeline embolization device. The Pipeline device is inserted into the blood vessel and incorporates a mesh that covers the mouth of the aneurysm. The mesh allows the inner lining of the blood vessel to grow and patch the aneurysm from the inside. In April 2011, the Pipeline embolization device was approved in the United States for the treatment of aneurysms larger than 10 mm on the carotid artery. Many physicians have used the device to treat smaller aneurysms, but no investigators had examined its safety and efficacy in this indication.

Examining an Off-Label Use of the Device

Ricardo Hanel, MD, PhD, Director of Baptist Neurological Institute in Jacksonville, Florida, and colleagues conducted a prospective, multicenter study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the Pipeline device in the treatment of small to medium-sized (ie, 12 mm or smaller), wide-necked, unruptured aneurysms on the internal carotid artery or vertebral artery. Eligible patients were between ages 22 and 80 and had an aneurysm neck that was 4 mm or larger. Patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage in the previous 30 days and those who had received an intracranial implant in the area of the target aneurysm within the previous 12 weeks were excluded.

The primary efficacy end point was complete aneurysm occlusion without significant parent artery stenosis at one year post procedure. The secondary efficacy end point was device deployment success rate. The primary safety end point was major stroke in the area supplied by the treated artery or neurologic death at one year post treatment. Secondary safety end points included major stroke or neurologic death at 30 days post treatment. Follow-up was conducted at 30 days, six months, one year, two years, and three years.

Dr. Hanel and colleagues enrolled 141 patients into the trial. The population’s mean age was approximately 55, and about 88% of the population was female. Participants had few, if any, symptoms. Approximately 48% of the population had hypertension, 38% had hyperlipidemia, and 44% were current smokers or had smoked within the previous 10 years.

Most Patients Had Complete Occlusion

Mean aneurysm size at baseline was 5 mm. About 84% of the aneurysms were smaller than 7 mm, and 16% were between 7 mm and 12 mm. Approximately 97% of aneurysms were saccular; 12% of saccular aneurysms involved a side branch, and 84% involved a sidewall, but no branch. About 4% of aneurysms were fusiform. About 95% of aneurysms were on the carotid artery. The two most common patient risk factors for treatment were patient preference (63%) and hypertension (48%).

The device was deployed to the target site successfully in about 99% of patients. Mean procedure time was approximately 80 minutes. The mean number of Pipeline devices required to treat each aneurysm was one. Ten patients received multiple Pipeline devices.

The investigators achieved complete occlusion without significant stenosis or retreatment at one year in approximately 84% of patients. This end point was documented by angiogram and adjudicated by an independent core laboratory. The reasons for treatment failure included residual aneurysm (8% of all patients), residual neck (6%), stenosis greater than 50% (1%), and aneurysm retreatment (2%).

At 30 days, three safety events had occurred in two patients. Both patients had a major stroke, and one of them died. The 30-day safety event rate thus was about 1%. One other safety event, a stroke, occurred at 169 days after treatment. The rate of major stroke and death at one year was approximately 2%. Two-year and three-year data are forthcoming.

The study was not designed to define which patients should be treated with a flow diverter, which is “a much broader and harder question,” said Dr. Hanel. Neurologists treat between 20% and 25% of patients with aneurysms smaller than 7 mm. The decision to treat is based on risk factors such as medical history and aneurysm location.

Aneurysms like those in the study “are difficult to treat with current armamentarium devices,” said Ralph L. Sacco, MD, Professor and Olemberg Chair of Neurology at the University of Miami. The current study indicates that the Pipeline device is safe and that these aneurysms can be treated, he added.

Dr. Hanel is a consultant for Medtronic, the manufacturer of the Pipeline device and the funder of the study.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Becske T, Potts MB, Shapiro M, et al. Pipeline for uncoilable or failed aneurysms: 3-year follow-up results. J Neurosurg. 2016 Oct 14:1-8. [Epub ahead of print].

Brinjikji W, Murad MH, Lanzino G, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with flow diverters: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2013;44(2):442-447.

HOUSTON—A flow-diverter device can treat small to medium-sized unruptured aneurysms safely and effectively, according to research presented at the International Stroke Conference 2017. The device has a high rate of aneurysm occlusion and is associated with no aneurysm rupture or recurrence at one year. The treatment also entails low rates of morbidity and mortality at one year.

One flow diverter is the Pipeline embolization device. The Pipeline device is inserted into the blood vessel and incorporates a mesh that covers the mouth of the aneurysm. The mesh allows the inner lining of the blood vessel to grow and patch the aneurysm from the inside. In April 2011, the Pipeline embolization device was approved in the United States for the treatment of aneurysms larger than 10 mm on the carotid artery. Many physicians have used the device to treat smaller aneurysms, but no investigators had examined its safety and efficacy in this indication.

Examining an Off-Label Use of the Device

Ricardo Hanel, MD, PhD, Director of Baptist Neurological Institute in Jacksonville, Florida, and colleagues conducted a prospective, multicenter study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the Pipeline device in the treatment of small to medium-sized (ie, 12 mm or smaller), wide-necked, unruptured aneurysms on the internal carotid artery or vertebral artery. Eligible patients were between ages 22 and 80 and had an aneurysm neck that was 4 mm or larger. Patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage in the previous 30 days and those who had received an intracranial implant in the area of the target aneurysm within the previous 12 weeks were excluded.

The primary efficacy end point was complete aneurysm occlusion without significant parent artery stenosis at one year post procedure. The secondary efficacy end point was device deployment success rate. The primary safety end point was major stroke in the area supplied by the treated artery or neurologic death at one year post treatment. Secondary safety end points included major stroke or neurologic death at 30 days post treatment. Follow-up was conducted at 30 days, six months, one year, two years, and three years.

Dr. Hanel and colleagues enrolled 141 patients into the trial. The population’s mean age was approximately 55, and about 88% of the population was female. Participants had few, if any, symptoms. Approximately 48% of the population had hypertension, 38% had hyperlipidemia, and 44% were current smokers or had smoked within the previous 10 years.

Most Patients Had Complete Occlusion

Mean aneurysm size at baseline was 5 mm. About 84% of the aneurysms were smaller than 7 mm, and 16% were between 7 mm and 12 mm. Approximately 97% of aneurysms were saccular; 12% of saccular aneurysms involved a side branch, and 84% involved a sidewall, but no branch. About 4% of aneurysms were fusiform. About 95% of aneurysms were on the carotid artery. The two most common patient risk factors for treatment were patient preference (63%) and hypertension (48%).

The device was deployed to the target site successfully in about 99% of patients. Mean procedure time was approximately 80 minutes. The mean number of Pipeline devices required to treat each aneurysm was one. Ten patients received multiple Pipeline devices.

The investigators achieved complete occlusion without significant stenosis or retreatment at one year in approximately 84% of patients. This end point was documented by angiogram and adjudicated by an independent core laboratory. The reasons for treatment failure included residual aneurysm (8% of all patients), residual neck (6%), stenosis greater than 50% (1%), and aneurysm retreatment (2%).

At 30 days, three safety events had occurred in two patients. Both patients had a major stroke, and one of them died. The 30-day safety event rate thus was about 1%. One other safety event, a stroke, occurred at 169 days after treatment. The rate of major stroke and death at one year was approximately 2%. Two-year and three-year data are forthcoming.

The study was not designed to define which patients should be treated with a flow diverter, which is “a much broader and harder question,” said Dr. Hanel. Neurologists treat between 20% and 25% of patients with aneurysms smaller than 7 mm. The decision to treat is based on risk factors such as medical history and aneurysm location.

Aneurysms like those in the study “are difficult to treat with current armamentarium devices,” said Ralph L. Sacco, MD, Professor and Olemberg Chair of Neurology at the University of Miami. The current study indicates that the Pipeline device is safe and that these aneurysms can be treated, he added.

Dr. Hanel is a consultant for Medtronic, the manufacturer of the Pipeline device and the funder of the study.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Becske T, Potts MB, Shapiro M, et al. Pipeline for uncoilable or failed aneurysms: 3-year follow-up results. J Neurosurg. 2016 Oct 14:1-8. [Epub ahead of print].

Brinjikji W, Murad MH, Lanzino G, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with flow diverters: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2013;44(2):442-447.

HOUSTON—A flow-diverter device can treat small to medium-sized unruptured aneurysms safely and effectively, according to research presented at the International Stroke Conference 2017. The device has a high rate of aneurysm occlusion and is associated with no aneurysm rupture or recurrence at one year. The treatment also entails low rates of morbidity and mortality at one year.

One flow diverter is the Pipeline embolization device. The Pipeline device is inserted into the blood vessel and incorporates a mesh that covers the mouth of the aneurysm. The mesh allows the inner lining of the blood vessel to grow and patch the aneurysm from the inside. In April 2011, the Pipeline embolization device was approved in the United States for the treatment of aneurysms larger than 10 mm on the carotid artery. Many physicians have used the device to treat smaller aneurysms, but no investigators had examined its safety and efficacy in this indication.

Examining an Off-Label Use of the Device

Ricardo Hanel, MD, PhD, Director of Baptist Neurological Institute in Jacksonville, Florida, and colleagues conducted a prospective, multicenter study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the Pipeline device in the treatment of small to medium-sized (ie, 12 mm or smaller), wide-necked, unruptured aneurysms on the internal carotid artery or vertebral artery. Eligible patients were between ages 22 and 80 and had an aneurysm neck that was 4 mm or larger. Patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage in the previous 30 days and those who had received an intracranial implant in the area of the target aneurysm within the previous 12 weeks were excluded.

The primary efficacy end point was complete aneurysm occlusion without significant parent artery stenosis at one year post procedure. The secondary efficacy end point was device deployment success rate. The primary safety end point was major stroke in the area supplied by the treated artery or neurologic death at one year post treatment. Secondary safety end points included major stroke or neurologic death at 30 days post treatment. Follow-up was conducted at 30 days, six months, one year, two years, and three years.

Dr. Hanel and colleagues enrolled 141 patients into the trial. The population’s mean age was approximately 55, and about 88% of the population was female. Participants had few, if any, symptoms. Approximately 48% of the population had hypertension, 38% had hyperlipidemia, and 44% were current smokers or had smoked within the previous 10 years.

Most Patients Had Complete Occlusion

Mean aneurysm size at baseline was 5 mm. About 84% of the aneurysms were smaller than 7 mm, and 16% were between 7 mm and 12 mm. Approximately 97% of aneurysms were saccular; 12% of saccular aneurysms involved a side branch, and 84% involved a sidewall, but no branch. About 4% of aneurysms were fusiform. About 95% of aneurysms were on the carotid artery. The two most common patient risk factors for treatment were patient preference (63%) and hypertension (48%).

The device was deployed to the target site successfully in about 99% of patients. Mean procedure time was approximately 80 minutes. The mean number of Pipeline devices required to treat each aneurysm was one. Ten patients received multiple Pipeline devices.

The investigators achieved complete occlusion without significant stenosis or retreatment at one year in approximately 84% of patients. This end point was documented by angiogram and adjudicated by an independent core laboratory. The reasons for treatment failure included residual aneurysm (8% of all patients), residual neck (6%), stenosis greater than 50% (1%), and aneurysm retreatment (2%).

At 30 days, three safety events had occurred in two patients. Both patients had a major stroke, and one of them died. The 30-day safety event rate thus was about 1%. One other safety event, a stroke, occurred at 169 days after treatment. The rate of major stroke and death at one year was approximately 2%. Two-year and three-year data are forthcoming.

The study was not designed to define which patients should be treated with a flow diverter, which is “a much broader and harder question,” said Dr. Hanel. Neurologists treat between 20% and 25% of patients with aneurysms smaller than 7 mm. The decision to treat is based on risk factors such as medical history and aneurysm location.

Aneurysms like those in the study “are difficult to treat with current armamentarium devices,” said Ralph L. Sacco, MD, Professor and Olemberg Chair of Neurology at the University of Miami. The current study indicates that the Pipeline device is safe and that these aneurysms can be treated, he added.

Dr. Hanel is a consultant for Medtronic, the manufacturer of the Pipeline device and the funder of the study.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Becske T, Potts MB, Shapiro M, et al. Pipeline for uncoilable or failed aneurysms: 3-year follow-up results. J Neurosurg. 2016 Oct 14:1-8. [Epub ahead of print].

Brinjikji W, Murad MH, Lanzino G, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with flow diverters: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2013;44(2):442-447.

Can Environmental Toxicants Cause Parkinson’s Disease?

MIAMI—Accumulating evidence suggests that exposure to certain toxicants may increase the risk of Parkinson’s disease, according to an overview presented at the First Pan American Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Congress. Researchers seek to learn more about these chemicals and to investigate interventions that could reduce the risks that they present.

Synthetic Heroin and Parkinsonism

In 1983, several cases prompted researchers to think about whether toxicants could cause Parkinson’s disease. A 39-year-old man in California presented to an emergency room with visual hallucinations, jerking of limbs, generalized slowing, and difficulty walking. He had no prior medical history, neurologic history, or family history of neurologic disease. At around the same time, a woman and two men from the same area developed young-onset subacute parkinsonism. James Tetrud, MD, and J. William Langston, MD, the neurologists who examined these patients, learned that they were all IV narcotic addicts. Between two and six weeks before presentation, the patients had injected a synthetic heroin that they had obtained from the same supplier. The toxicant in the synthetic heroin that had induced the parkinsonism was identified as 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). All of these patients responded to levodopa.

Herbicides and Insecticides

In 2009, Dr. Tanner and colleagues conducted a case–control study to investigate whether specific occupations or toxicant exposures were associated with parkinsonism. They found that 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) was associated with a greater than twofold increased risk of Parkinson’s disease. This chemical was introduced as an herbicide in 1945 and is found in more than 1,500 products, including Agent Orange, which the US military used as a defoliant in Vietnam. Parkinson’s disease is considered to be service-connected in certain US military veterans who served in Vietnam. Currently, 2,4-D is used on lawns, golf courses, and large farms.

The authors also found that exposure to paraquat, another herbicide, nearly doubled the risk of Parkinson’s disease. In people with a homozygous deletion of GSTT1, a gene that encodes an enzyme important to xenobiotic metabolism, exposure to paraquat increased the risk of Parkinson’s disease 11-fold. In addition, exposure to rotenone, an insecticide and piscicide, increased the risk of Parkinson’s disease by more than two times.

Persistent Organic Pollutants

Exposure to persistent organic pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and organochlorine pesticides can also increase the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. A study by Becker et al in 2000 found an elevated prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in Greenland that may have resulted from exposure to PCBs.

This research prompted Dr. Tanner and colleagues to conduct a case–control study of Alaska natives. The investigators examined the food, diet, occupation, toxicant exposure, blood, and DNA of 69 people with Parkinson’s disease and 179 controls in the Alaska native health system. They found higher blood levels of hexachlorobenzene and PCBs in people with Parkinson’s disease, compared with healthy controls. The blood levels approximately doubled the risk of Parkinson’s disease.

In the Agricultural Health Study, investigators found a similar association between serum PCB level and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Furthermore, people with a particular variant of the efflux transporter gene, which protects cells from exogenous chemicals, and people who also had high serum PCB levels had as much as a 12-fold increased risk of Parkinson’s disease. When Dr. Tanner and colleagues reexamined the data from the Alaska native population, they found that this gene variant had a similar effect. People with a low-risk genotype did not have a greatly increased risk of Parkinson’s disease, even after high exposure to PCBs.

In the 1980s, Hawaiian pineapple farmers sprayed organochlorine pesticides on plants that later were fed to dairy cows. More recently, the Honolulu Asia Aging Study, a prospective cohort study, suggested that milk consumption was associated with increased risk of parkinsonism. In addition, G. Webster Ross, MD, and colleagues analyzed postmortem data and found that nonsmokers who consumed high amounts of milk had low neuron density. Other research has found that brain organochlorine levels were associated with Lewy pathology.

Solvents

Solvents are another class of chemicals that has been associated with Parkinson’s disease. In a 2008 study of 30 industrial coworkers with Parkinson’s disease, Gash et al found that trichloroethylene, a solvent used in many industrial processes such as dry cleaning, was a risk factor for parkinsonism. In a twin study, Dr. Tanner and colleagues found that chlorinated solvents were associated with an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease.