User login

CHMP recommends inotuzumab ozogamicin for adult ALL

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has adopted a positive opinion of inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa®).

The CHMP is recommending approval of inotuzumab ozogamicin for the treatment of adults with relapsed or refractory CD22-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), including patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL who have failed treatment with at least one tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

The CHMP’s opinion will be reviewed by the European Commission, which is expected to issue a decision on approval within 67 days from adoption of the opinion.

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of a monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 and a cytotoxic agent known as calicheamicin.

The product originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech (now UCB), but Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing and clinical development activities.

The application for inotuzumab ozogamicin is supported by results from a phase 3 trial, which were published in NEJM in June 2016.

The trial enrolled 326 adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL and compared inotuzumab ozogamicin to standard of care chemotherapy.

The rate of complete remission, including incomplete hematologic recovery, was 80.7% in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 29.4% in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001). The median duration of remission was 4.6 months and 3.1 months, respectively (P=0.03).

Forty-one percent of patients treated with inotuzumab ozogamicin and 11% of those who received chemotherapy proceeded to stem cell transplant directly after treatment (P<0.001).

The median progression-free survival was 5.0 months in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1.8 months in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001).

The median overall survival was 7.7 months and 6.7 months, respectively (P=0.04). This did not meet the prespecified boundary of significance (P=0.0208).

Liver-related adverse events were more common in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm than the chemotherapy arm. The most frequent of these were increased aspartate aminotransferase level (20% vs 10%), hyperbilirubinemia (15% vs 10%), and increased alanine aminotransferase level (14% vs 11%).

Veno-occlusive liver disease occurred in 11% of patients in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 17 deaths during treatment in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 11 in the chemotherapy arm. Four deaths were considered related to inotuzumab ozogamicin, and 2 were thought to be related to chemotherapy. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has adopted a positive opinion of inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa®).

The CHMP is recommending approval of inotuzumab ozogamicin for the treatment of adults with relapsed or refractory CD22-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), including patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL who have failed treatment with at least one tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

The CHMP’s opinion will be reviewed by the European Commission, which is expected to issue a decision on approval within 67 days from adoption of the opinion.

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of a monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 and a cytotoxic agent known as calicheamicin.

The product originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech (now UCB), but Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing and clinical development activities.

The application for inotuzumab ozogamicin is supported by results from a phase 3 trial, which were published in NEJM in June 2016.

The trial enrolled 326 adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL and compared inotuzumab ozogamicin to standard of care chemotherapy.

The rate of complete remission, including incomplete hematologic recovery, was 80.7% in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 29.4% in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001). The median duration of remission was 4.6 months and 3.1 months, respectively (P=0.03).

Forty-one percent of patients treated with inotuzumab ozogamicin and 11% of those who received chemotherapy proceeded to stem cell transplant directly after treatment (P<0.001).

The median progression-free survival was 5.0 months in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1.8 months in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001).

The median overall survival was 7.7 months and 6.7 months, respectively (P=0.04). This did not meet the prespecified boundary of significance (P=0.0208).

Liver-related adverse events were more common in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm than the chemotherapy arm. The most frequent of these were increased aspartate aminotransferase level (20% vs 10%), hyperbilirubinemia (15% vs 10%), and increased alanine aminotransferase level (14% vs 11%).

Veno-occlusive liver disease occurred in 11% of patients in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 17 deaths during treatment in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 11 in the chemotherapy arm. Four deaths were considered related to inotuzumab ozogamicin, and 2 were thought to be related to chemotherapy. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has adopted a positive opinion of inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa®).

The CHMP is recommending approval of inotuzumab ozogamicin for the treatment of adults with relapsed or refractory CD22-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), including patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL who have failed treatment with at least one tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

The CHMP’s opinion will be reviewed by the European Commission, which is expected to issue a decision on approval within 67 days from adoption of the opinion.

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of a monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 and a cytotoxic agent known as calicheamicin.

The product originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech (now UCB), but Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing and clinical development activities.

The application for inotuzumab ozogamicin is supported by results from a phase 3 trial, which were published in NEJM in June 2016.

The trial enrolled 326 adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL and compared inotuzumab ozogamicin to standard of care chemotherapy.

The rate of complete remission, including incomplete hematologic recovery, was 80.7% in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 29.4% in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001). The median duration of remission was 4.6 months and 3.1 months, respectively (P=0.03).

Forty-one percent of patients treated with inotuzumab ozogamicin and 11% of those who received chemotherapy proceeded to stem cell transplant directly after treatment (P<0.001).

The median progression-free survival was 5.0 months in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1.8 months in the chemotherapy arm (P<0.001).

The median overall survival was 7.7 months and 6.7 months, respectively (P=0.04). This did not meet the prespecified boundary of significance (P=0.0208).

Liver-related adverse events were more common in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm than the chemotherapy arm. The most frequent of these were increased aspartate aminotransferase level (20% vs 10%), hyperbilirubinemia (15% vs 10%), and increased alanine aminotransferase level (14% vs 11%).

Veno-occlusive liver disease occurred in 11% of patients in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 1% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 17 deaths during treatment in the inotuzumab ozogamicin arm and 11 in the chemotherapy arm. Four deaths were considered related to inotuzumab ozogamicin, and 2 were thought to be related to chemotherapy. ![]()

Elimination of urine culture screening prior to elective joint arthroplasty

Clinical question: What is the clinical impact of implementing a policy to no longer process urine specimens for perioperative screening in patients undergoing elective joint arthroplasty (EJA)?

Background: Despite prior studies indicating the lack of clinical benefit, preoperative urine cultures are still frequently obtained in patients undergoing EJA in attempts to reduce the risk of periprosthetic joint infections (PJI).

Study Design: Time series analysis.

Setting: Holland Orthopedic and Arthritic Center (HOAC) of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Synopsis: After a multidisciplinary meeting, obtaining routine urine culture screening was removed from the preoperative order set. A time series analysis was performed to review the frequency of screening urine cultures obtained and processed, the number of patients treated for asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), and the incidence of PJI before and after the new policy was implemented. After the policy change, only 129 screening urine cultures were obtained prior to 1,891 EJAs (7 per 100 EJA; 95% CI 6-8; P less than .0001) which is a drastic decrease from the 3,069 screening urine cultures obtained prior to 3,523 EJAs (87 per 100 EJA; 95% CI, 86-88) before the policy change. Prior to the policy change, of the 352 positive urine cultures, 43 received perioperative treatment for ASB, and PJI incidence was 1/3523 (0.03%; 95% CI, 0.001-02). After the policy change, no perioperative antibiotics were prescribed for ASB, and PJI rate did not significantly change at 3/1891 (0.2%; 95% CI, 0.05-0.5; P = .1).

The study was limited by its low power to detect for small differences in rates because of its small PJI rate occurrence.

Bottom Line: A multidisciplinary approach in eliminating routine urine screening prior to EJA resulted in a decrease of urine cultures obtained and a decrease in treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria, with no significant change in PJI rate. This change in clinical practice is supported by current evidence and has a significant impact on cost savings.

References: Lamb MJ, Baillie L, Pajak D, et al. “Elimination of Screening Urine Cultures Prior to Elective Joint Arthroplasty.”

Dr. Libot is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical question: What is the clinical impact of implementing a policy to no longer process urine specimens for perioperative screening in patients undergoing elective joint arthroplasty (EJA)?

Background: Despite prior studies indicating the lack of clinical benefit, preoperative urine cultures are still frequently obtained in patients undergoing EJA in attempts to reduce the risk of periprosthetic joint infections (PJI).

Study Design: Time series analysis.

Setting: Holland Orthopedic and Arthritic Center (HOAC) of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Synopsis: After a multidisciplinary meeting, obtaining routine urine culture screening was removed from the preoperative order set. A time series analysis was performed to review the frequency of screening urine cultures obtained and processed, the number of patients treated for asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), and the incidence of PJI before and after the new policy was implemented. After the policy change, only 129 screening urine cultures were obtained prior to 1,891 EJAs (7 per 100 EJA; 95% CI 6-8; P less than .0001) which is a drastic decrease from the 3,069 screening urine cultures obtained prior to 3,523 EJAs (87 per 100 EJA; 95% CI, 86-88) before the policy change. Prior to the policy change, of the 352 positive urine cultures, 43 received perioperative treatment for ASB, and PJI incidence was 1/3523 (0.03%; 95% CI, 0.001-02). After the policy change, no perioperative antibiotics were prescribed for ASB, and PJI rate did not significantly change at 3/1891 (0.2%; 95% CI, 0.05-0.5; P = .1).

The study was limited by its low power to detect for small differences in rates because of its small PJI rate occurrence.

Bottom Line: A multidisciplinary approach in eliminating routine urine screening prior to EJA resulted in a decrease of urine cultures obtained and a decrease in treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria, with no significant change in PJI rate. This change in clinical practice is supported by current evidence and has a significant impact on cost savings.

References: Lamb MJ, Baillie L, Pajak D, et al. “Elimination of Screening Urine Cultures Prior to Elective Joint Arthroplasty.”

Dr. Libot is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical question: What is the clinical impact of implementing a policy to no longer process urine specimens for perioperative screening in patients undergoing elective joint arthroplasty (EJA)?

Background: Despite prior studies indicating the lack of clinical benefit, preoperative urine cultures are still frequently obtained in patients undergoing EJA in attempts to reduce the risk of periprosthetic joint infections (PJI).

Study Design: Time series analysis.

Setting: Holland Orthopedic and Arthritic Center (HOAC) of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Synopsis: After a multidisciplinary meeting, obtaining routine urine culture screening was removed from the preoperative order set. A time series analysis was performed to review the frequency of screening urine cultures obtained and processed, the number of patients treated for asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), and the incidence of PJI before and after the new policy was implemented. After the policy change, only 129 screening urine cultures were obtained prior to 1,891 EJAs (7 per 100 EJA; 95% CI 6-8; P less than .0001) which is a drastic decrease from the 3,069 screening urine cultures obtained prior to 3,523 EJAs (87 per 100 EJA; 95% CI, 86-88) before the policy change. Prior to the policy change, of the 352 positive urine cultures, 43 received perioperative treatment for ASB, and PJI incidence was 1/3523 (0.03%; 95% CI, 0.001-02). After the policy change, no perioperative antibiotics were prescribed for ASB, and PJI rate did not significantly change at 3/1891 (0.2%; 95% CI, 0.05-0.5; P = .1).

The study was limited by its low power to detect for small differences in rates because of its small PJI rate occurrence.

Bottom Line: A multidisciplinary approach in eliminating routine urine screening prior to EJA resulted in a decrease of urine cultures obtained and a decrease in treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria, with no significant change in PJI rate. This change in clinical practice is supported by current evidence and has a significant impact on cost savings.

References: Lamb MJ, Baillie L, Pajak D, et al. “Elimination of Screening Urine Cultures Prior to Elective Joint Arthroplasty.”

Dr. Libot is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

In the lit: Short takes

Efficacy of ketorolac is similar at all the most commonly administered doses

A randomized, double-blind trial of IV ketorolac dosing found similar analgesic efficacy in patients aged 18-65 years with moderate to severe pain at the commonly ordered doses of 10 mg, 15 mg, and 30 mg with no increase in adverse effects.

Citation: Motov S, Yasavolian M, Likourezos A, et al. “Comparison of intravenous ketorolac at three single-dose regimens for treating acute pain in the emergency department: A randomized controlled trial.” Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Dec 16. doi: org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.10.014.

-- Paula Marfia, MD, is assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Viruses are common cause of nonventilated, hospital-acquired pneumonia

Retrospective analysis demonstrates that viruses are common etiology for nonventilated hospital-acquired pneumonia (NVHAP), as common as bacterial organisms. Clinicians should consider testing for viral etiologies in NVHAP in an effort to improve antibiotic stewardship.

Citation: Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Micek ST, Kollef MH. “Viruses are prevalent in non-ventilated hospital-acquired pneumonia.” Respir Med. 2017;122:76-80.

-- Anar Mashruwala, MD, FACP, is assistant professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

FDA issues important safety precautions for use of implantable infusions pumps in MRI

Serious adverse events, including patient injury and death, have been reported with the use of implantable infusion pumps in the MRI environment. The Food and Drug Administration has issued a safety communication for patients, caregivers, health care providers, and MRI technologists, outlining safety precautions and recommendations.

Citation: “Implantable Infusion Pumps in the Magnetic Resonance (MR) Environment: FDA Safety Communication – Important Safety Precautions.” FDA.gov. 2017 Jan 11.

-- Anar Mashruwala, MD, FACP, is assistant professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Efficacy of ketorolac is similar at all the most commonly administered doses

A randomized, double-blind trial of IV ketorolac dosing found similar analgesic efficacy in patients aged 18-65 years with moderate to severe pain at the commonly ordered doses of 10 mg, 15 mg, and 30 mg with no increase in adverse effects.

Citation: Motov S, Yasavolian M, Likourezos A, et al. “Comparison of intravenous ketorolac at three single-dose regimens for treating acute pain in the emergency department: A randomized controlled trial.” Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Dec 16. doi: org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.10.014.

-- Paula Marfia, MD, is assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Viruses are common cause of nonventilated, hospital-acquired pneumonia

Retrospective analysis demonstrates that viruses are common etiology for nonventilated hospital-acquired pneumonia (NVHAP), as common as bacterial organisms. Clinicians should consider testing for viral etiologies in NVHAP in an effort to improve antibiotic stewardship.

Citation: Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Micek ST, Kollef MH. “Viruses are prevalent in non-ventilated hospital-acquired pneumonia.” Respir Med. 2017;122:76-80.

-- Anar Mashruwala, MD, FACP, is assistant professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

FDA issues important safety precautions for use of implantable infusions pumps in MRI

Serious adverse events, including patient injury and death, have been reported with the use of implantable infusion pumps in the MRI environment. The Food and Drug Administration has issued a safety communication for patients, caregivers, health care providers, and MRI technologists, outlining safety precautions and recommendations.

Citation: “Implantable Infusion Pumps in the Magnetic Resonance (MR) Environment: FDA Safety Communication – Important Safety Precautions.” FDA.gov. 2017 Jan 11.

-- Anar Mashruwala, MD, FACP, is assistant professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Efficacy of ketorolac is similar at all the most commonly administered doses

A randomized, double-blind trial of IV ketorolac dosing found similar analgesic efficacy in patients aged 18-65 years with moderate to severe pain at the commonly ordered doses of 10 mg, 15 mg, and 30 mg with no increase in adverse effects.

Citation: Motov S, Yasavolian M, Likourezos A, et al. “Comparison of intravenous ketorolac at three single-dose regimens for treating acute pain in the emergency department: A randomized controlled trial.” Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Dec 16. doi: org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.10.014.

-- Paula Marfia, MD, is assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Viruses are common cause of nonventilated, hospital-acquired pneumonia

Retrospective analysis demonstrates that viruses are common etiology for nonventilated hospital-acquired pneumonia (NVHAP), as common as bacterial organisms. Clinicians should consider testing for viral etiologies in NVHAP in an effort to improve antibiotic stewardship.

Citation: Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Micek ST, Kollef MH. “Viruses are prevalent in non-ventilated hospital-acquired pneumonia.” Respir Med. 2017;122:76-80.

-- Anar Mashruwala, MD, FACP, is assistant professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

FDA issues important safety precautions for use of implantable infusions pumps in MRI

Serious adverse events, including patient injury and death, have been reported with the use of implantable infusion pumps in the MRI environment. The Food and Drug Administration has issued a safety communication for patients, caregivers, health care providers, and MRI technologists, outlining safety precautions and recommendations.

Citation: “Implantable Infusion Pumps in the Magnetic Resonance (MR) Environment: FDA Safety Communication – Important Safety Precautions.” FDA.gov. 2017 Jan 11.

-- Anar Mashruwala, MD, FACP, is assistant professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

WHO report sets baseline for viral hepatitis elimination

AMSTERDAM – An estimated 328 million people worldwide were living with chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection in 2015 according to a new report issued by the World Health Organization and launched at the International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL).

The WHO Global Hepatitis Report gives the worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B (HBV) infection as 257 million and that of chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection as 71 million at this time point, reported Yvan Hutin, MD, medical officer at the WHO Department of HIV and Global Hepatitis Programme (HIV/GHP) in Geneva.

Dr. Hutin explained that the report was needed as it sets the baseline or “year zero” for tracking the success of WHO’s new global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat, reduce the number of new HBV and HCV infections by 90%, and reduce viral hepatitis mortality by 65% by 2030.

The report was “a very important statement for all of us who work in this field,” said EASL Vice-Secretary Tom Hemming Karslen, MD, during a press briefing. “This is a wonderful initiative helping all the activities that are now already ongoing and need to be strengthened to move in a coordinated manner.”

The launch of the report at the International Liver Congress was “win-win situation”, Gottfried Hirnschall, MD, director of the WHO Department of HIV/GHP, said at the press briefing.

“We are in the era of elimination. It is not only the commitment of the WHO, it is the commitment of the 194 member states who have signed up for elimination,” he said.

“An important message is that people are still dying of hepatitis, the numbers are still going up,” Dr. Hirnschall said. There were an estimated 1.34 million viral hepatitis deaths worldwide in 2015, most (95%) were due to the development of cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma, according to the new report. “We have a public health issue that obviously still needs to be addressed.”

Three decades ago, little could be done to prevent or treat infection with HBV or HCV, Dr. Hutin said during the opening general scientific session. A lot has changed since then, prevention of hepatitis B started to become a reality with the availability of a vaccine and understanding of the importance of improved blood safety and injection practices. Since 2010, there have also been improvements in the drugs available to treat, and potentially eliminate, HCV, notably direct-acting antiviral agents.

“To reach elimination, we modeled that we needed to reach sufficient service coverage for five core interventions,” Dr. Hutin said. Specifically:

- At least 90% of the world’s eligible population receives the three-dose hepatitis B vaccine

- 100% of blood donations are screened appropriately

- Proper injection technique is employed in 90% of cases

- Clean needles made available where they are needed

- 90% of people infected are diagnosed and 80% are treated.

Vaccination against HBV has been one success in the past 20 years, Ana Maria Henao Restrepo, MD, medical officer at the WHO Department of Immunization Vaccination and Biologicals, said at the press briefing.

Vaccination against HBV started in 1982, she said, “when the first safe and effective vaccine became available, and now four out of five children receive this life-saving vaccine. We are very pleased with this achievement but we know that there is still more work to do.”

The WHO report estimates that the global incidence of chronic HBV infection in children under 5 years of age was reduced from 4.7% in the pre-vaccination era to 1.3% in 2015 because of immunization.

But while uptake of the three-dose hepatitis B vaccine has increased, with 85% coverage of the worlds population in 2015, the number of children receiving this vaccine at birth is just 39% overall, with lower rates in the African region.

“Unsafe health care injections and injection drug use continue to transmit HCV, particularly in the eastern Mediterranean region and the European region,” Dr. Hutin said.

The WHO has already set up a campaign to improve blood and injection safety called “Get the Point,” but there is still a long way to go. The target is to provide 300 needle and syringe sets per person per year to people who inject drugs; the current rate is around 27 sets.

Of the 257 people infected with hepatitis B in 2015, only 9% were diagnosed and 1.7 million received treatment. As for hepatitis C, 20% of 71 million were diagnosed and 1.1 million received treatment.

“We need a public health approach that delivers all the basic services to all, including to specific groups that may differ from the general population in terms of incidence, prevalence, vulnerability, or needs,” said Dr. Hutin. This includes health care workers, intravenous drug users, prisoners, migrants, blood donors, men who have sex with men, sex workers, and indigenous populations.

“We have all the tools we need to eliminate hepatitis,” he said, adding that improved point of care tests, a functional cure for HBV, and a vaccine against HCV would accelerate the process.

“A year ago, elimination by 2030 looked very ambitious, but not that we’ve carefully looked at the baseline, it seems that we have a start. It’s going to be a lot of work but the train has left the station and we should get there,” Dr. Hutin concluded.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided funding for the production of the report. All speakers had no conflicts of interest.

AMSTERDAM – An estimated 328 million people worldwide were living with chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection in 2015 according to a new report issued by the World Health Organization and launched at the International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL).

The WHO Global Hepatitis Report gives the worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B (HBV) infection as 257 million and that of chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection as 71 million at this time point, reported Yvan Hutin, MD, medical officer at the WHO Department of HIV and Global Hepatitis Programme (HIV/GHP) in Geneva.

Dr. Hutin explained that the report was needed as it sets the baseline or “year zero” for tracking the success of WHO’s new global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat, reduce the number of new HBV and HCV infections by 90%, and reduce viral hepatitis mortality by 65% by 2030.

The report was “a very important statement for all of us who work in this field,” said EASL Vice-Secretary Tom Hemming Karslen, MD, during a press briefing. “This is a wonderful initiative helping all the activities that are now already ongoing and need to be strengthened to move in a coordinated manner.”

The launch of the report at the International Liver Congress was “win-win situation”, Gottfried Hirnschall, MD, director of the WHO Department of HIV/GHP, said at the press briefing.

“We are in the era of elimination. It is not only the commitment of the WHO, it is the commitment of the 194 member states who have signed up for elimination,” he said.

“An important message is that people are still dying of hepatitis, the numbers are still going up,” Dr. Hirnschall said. There were an estimated 1.34 million viral hepatitis deaths worldwide in 2015, most (95%) were due to the development of cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma, according to the new report. “We have a public health issue that obviously still needs to be addressed.”

Three decades ago, little could be done to prevent or treat infection with HBV or HCV, Dr. Hutin said during the opening general scientific session. A lot has changed since then, prevention of hepatitis B started to become a reality with the availability of a vaccine and understanding of the importance of improved blood safety and injection practices. Since 2010, there have also been improvements in the drugs available to treat, and potentially eliminate, HCV, notably direct-acting antiviral agents.

“To reach elimination, we modeled that we needed to reach sufficient service coverage for five core interventions,” Dr. Hutin said. Specifically:

- At least 90% of the world’s eligible population receives the three-dose hepatitis B vaccine

- 100% of blood donations are screened appropriately

- Proper injection technique is employed in 90% of cases

- Clean needles made available where they are needed

- 90% of people infected are diagnosed and 80% are treated.

Vaccination against HBV has been one success in the past 20 years, Ana Maria Henao Restrepo, MD, medical officer at the WHO Department of Immunization Vaccination and Biologicals, said at the press briefing.

Vaccination against HBV started in 1982, she said, “when the first safe and effective vaccine became available, and now four out of five children receive this life-saving vaccine. We are very pleased with this achievement but we know that there is still more work to do.”

The WHO report estimates that the global incidence of chronic HBV infection in children under 5 years of age was reduced from 4.7% in the pre-vaccination era to 1.3% in 2015 because of immunization.

But while uptake of the three-dose hepatitis B vaccine has increased, with 85% coverage of the worlds population in 2015, the number of children receiving this vaccine at birth is just 39% overall, with lower rates in the African region.

“Unsafe health care injections and injection drug use continue to transmit HCV, particularly in the eastern Mediterranean region and the European region,” Dr. Hutin said.

The WHO has already set up a campaign to improve blood and injection safety called “Get the Point,” but there is still a long way to go. The target is to provide 300 needle and syringe sets per person per year to people who inject drugs; the current rate is around 27 sets.

Of the 257 people infected with hepatitis B in 2015, only 9% were diagnosed and 1.7 million received treatment. As for hepatitis C, 20% of 71 million were diagnosed and 1.1 million received treatment.

“We need a public health approach that delivers all the basic services to all, including to specific groups that may differ from the general population in terms of incidence, prevalence, vulnerability, or needs,” said Dr. Hutin. This includes health care workers, intravenous drug users, prisoners, migrants, blood donors, men who have sex with men, sex workers, and indigenous populations.

“We have all the tools we need to eliminate hepatitis,” he said, adding that improved point of care tests, a functional cure for HBV, and a vaccine against HCV would accelerate the process.

“A year ago, elimination by 2030 looked very ambitious, but not that we’ve carefully looked at the baseline, it seems that we have a start. It’s going to be a lot of work but the train has left the station and we should get there,” Dr. Hutin concluded.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided funding for the production of the report. All speakers had no conflicts of interest.

AMSTERDAM – An estimated 328 million people worldwide were living with chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection in 2015 according to a new report issued by the World Health Organization and launched at the International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL).

The WHO Global Hepatitis Report gives the worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B (HBV) infection as 257 million and that of chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection as 71 million at this time point, reported Yvan Hutin, MD, medical officer at the WHO Department of HIV and Global Hepatitis Programme (HIV/GHP) in Geneva.

Dr. Hutin explained that the report was needed as it sets the baseline or “year zero” for tracking the success of WHO’s new global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat, reduce the number of new HBV and HCV infections by 90%, and reduce viral hepatitis mortality by 65% by 2030.

The report was “a very important statement for all of us who work in this field,” said EASL Vice-Secretary Tom Hemming Karslen, MD, during a press briefing. “This is a wonderful initiative helping all the activities that are now already ongoing and need to be strengthened to move in a coordinated manner.”

The launch of the report at the International Liver Congress was “win-win situation”, Gottfried Hirnschall, MD, director of the WHO Department of HIV/GHP, said at the press briefing.

“We are in the era of elimination. It is not only the commitment of the WHO, it is the commitment of the 194 member states who have signed up for elimination,” he said.

“An important message is that people are still dying of hepatitis, the numbers are still going up,” Dr. Hirnschall said. There were an estimated 1.34 million viral hepatitis deaths worldwide in 2015, most (95%) were due to the development of cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma, according to the new report. “We have a public health issue that obviously still needs to be addressed.”

Three decades ago, little could be done to prevent or treat infection with HBV or HCV, Dr. Hutin said during the opening general scientific session. A lot has changed since then, prevention of hepatitis B started to become a reality with the availability of a vaccine and understanding of the importance of improved blood safety and injection practices. Since 2010, there have also been improvements in the drugs available to treat, and potentially eliminate, HCV, notably direct-acting antiviral agents.

“To reach elimination, we modeled that we needed to reach sufficient service coverage for five core interventions,” Dr. Hutin said. Specifically:

- At least 90% of the world’s eligible population receives the three-dose hepatitis B vaccine

- 100% of blood donations are screened appropriately

- Proper injection technique is employed in 90% of cases

- Clean needles made available where they are needed

- 90% of people infected are diagnosed and 80% are treated.

Vaccination against HBV has been one success in the past 20 years, Ana Maria Henao Restrepo, MD, medical officer at the WHO Department of Immunization Vaccination and Biologicals, said at the press briefing.

Vaccination against HBV started in 1982, she said, “when the first safe and effective vaccine became available, and now four out of five children receive this life-saving vaccine. We are very pleased with this achievement but we know that there is still more work to do.”

The WHO report estimates that the global incidence of chronic HBV infection in children under 5 years of age was reduced from 4.7% in the pre-vaccination era to 1.3% in 2015 because of immunization.

But while uptake of the three-dose hepatitis B vaccine has increased, with 85% coverage of the worlds population in 2015, the number of children receiving this vaccine at birth is just 39% overall, with lower rates in the African region.

“Unsafe health care injections and injection drug use continue to transmit HCV, particularly in the eastern Mediterranean region and the European region,” Dr. Hutin said.

The WHO has already set up a campaign to improve blood and injection safety called “Get the Point,” but there is still a long way to go. The target is to provide 300 needle and syringe sets per person per year to people who inject drugs; the current rate is around 27 sets.

Of the 257 people infected with hepatitis B in 2015, only 9% were diagnosed and 1.7 million received treatment. As for hepatitis C, 20% of 71 million were diagnosed and 1.1 million received treatment.

“We need a public health approach that delivers all the basic services to all, including to specific groups that may differ from the general population in terms of incidence, prevalence, vulnerability, or needs,” said Dr. Hutin. This includes health care workers, intravenous drug users, prisoners, migrants, blood donors, men who have sex with men, sex workers, and indigenous populations.

“We have all the tools we need to eliminate hepatitis,” he said, adding that improved point of care tests, a functional cure for HBV, and a vaccine against HCV would accelerate the process.

“A year ago, elimination by 2030 looked very ambitious, but not that we’ve carefully looked at the baseline, it seems that we have a start. It’s going to be a lot of work but the train has left the station and we should get there,” Dr. Hutin concluded.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided funding for the production of the report. All speakers had no conflicts of interest.

AT ILC 2017

Integration of telemedicine into clinical gastroenterology and hepatology practice

Two trends in health care delivery that will continue unabated are a) reimbursement pressure and b) increasing demand for our services. Practices that care for patients with complex and chronic conditions are exploring innovative means to expand their care footprint in an economically viable way. One approach currently being used by many health systems is telemedicine. Telemedicine is care delivered remotely using some type of electronic communication. Potentially, telemedicine will allow us to provide specialty services remotely to primary care physicians or even patients. The University of Michigan inflammatory bowel disease program is piloting remote video conferencing, integrated within the electronic medical record system, to provide specialty gastrointestinal consultation directly to Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis patients within their homes. The University of Michigan Health System has an office ready to arrange rapid teleconsultation for any provider. Payment for services has been secured from several payers after health system negotiations. This practice is well established in multiple specialties and settings. In this month’s column, two telemedicine experts review the state of the field, so you too can participate. This innovation is something you should consider for your practice. Technology and payment mechanisms are now available.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

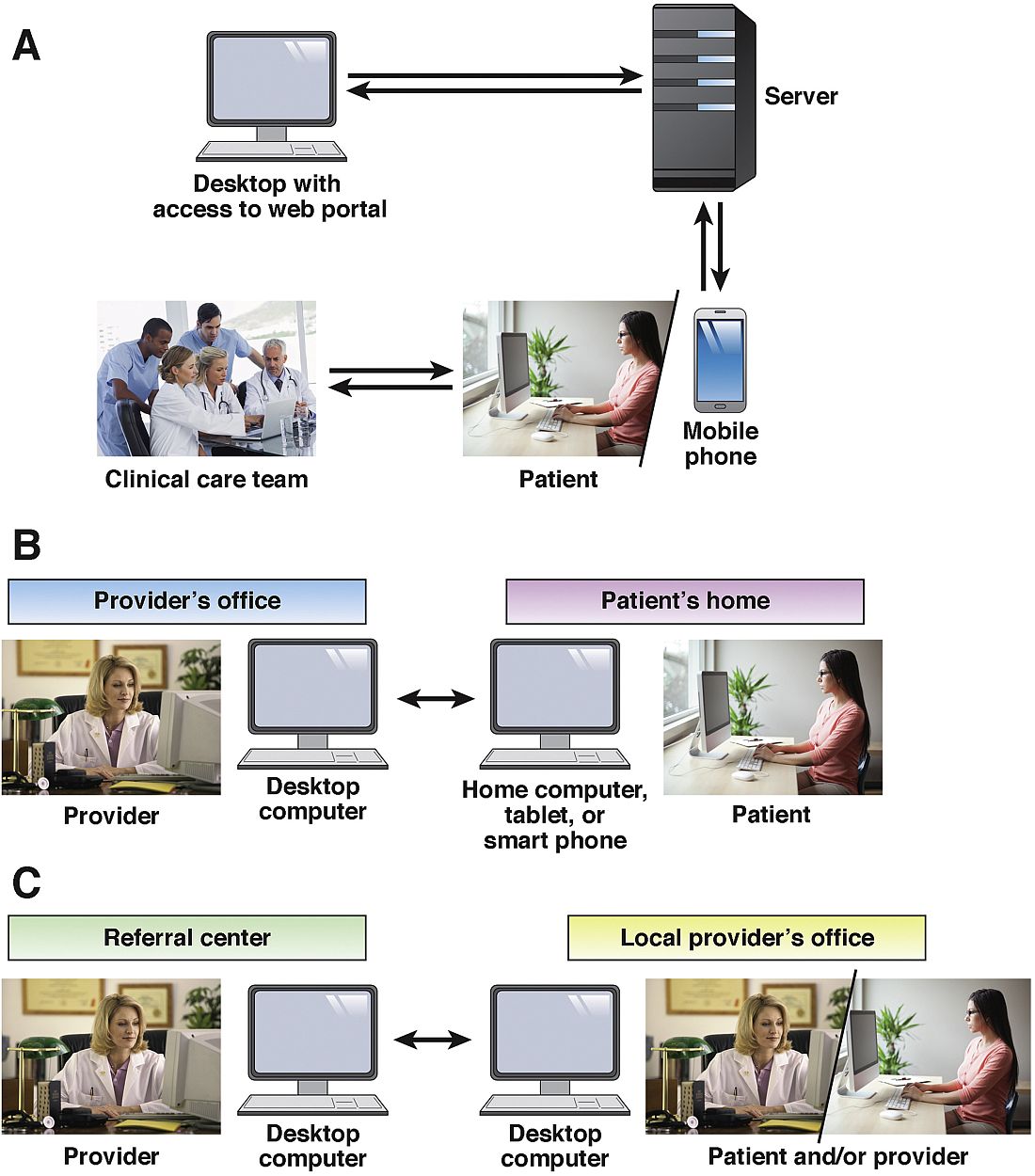

As defined by the American Telemedicine Association (ATA), telemedicine is the exchange of medical information from one site to another via electronic communication to improve a patient’s clinical health status.1 If we include care provided over the telephone via providers and nurses between office visits, telemedicine has been practiced for decades. A recent study from the University of Pittsburgh documented 32,667 phone calls from 3,118 patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in 2010. Seventy-five percent of these calls were related to patient concerns or were generated by the nurse because of changes in the treatment plan.2 If these results are applied to a representative work week, busy IBD centers typically handle more than 100 phone calls per day.3 Telemedicine in clinical practice has expanded to include a variety of modalities such as two-way video, email, or secure messaging through electronic medical records systems, smartphones, wireless tools, and other forms of telecommunication technology (see Figure 1). The increase in use of telemedicine in practice has been driven by a number of factors.

First, it is almost universal that patients have access to a computer and/or cellular telephone. According to the Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project, as of May 2013, 91% of adults are using cellphones.4 As patients have become more connected digitally, it is natural that they desire delivery of services, including health care services, electronically. Second, despite advances in medical, endoscopic, and surgical treatment, many patients still have suboptimal outcomes. There are many reasons for this, including but not limited to nonadherence, poor patient education, inadequate monitoring of symptoms and side effects, concurrent psychiatric disease, comorbid medical conditions, low self-efficacy, and limited access to health care; these issues can be addressed, at least in part, by telemedicine. Finally, patients are also seeking more efficient and convenient ways to receive their care,; including travel and wait times, an average office visit takes up to 2 hours.5

Enhanced monitoring and self-care through use of telemedicine technologies

Several groups have implemented telemedicine to improve monitoring and self-care in patients with IBD. Our group at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, has developed several systems to improve care as part of research protocols. Our first telemedicine system included a laptop computer and electronic weight scale connected telephonically to a server. Patients were asked questions about bowel symptoms, medication use, side effects, and body weight measurements. They also received educational messages. This system, IBD Home Automated Telemanagement (HAT), required installation in the patient’s home by a technical team. Our preliminary results demonstrated that patients were very receptive of the technology.6 In a small pilot study (n = 34), we demonstrated that 88% of patients were adherent to self-assessment during a period of 6 months. In addition, patients experienced a reduction in disease activity, improved quality of life, and increased disease state awareness.7 In a small, randomized, controlled follow-up trial, we demonstrated that use of an ulcerative colitis (UC) telemanagement system (UC HAT) resulted in improved quality of life and decreased disease activity from baseline during 1 year compared with controls. The UC HAT system was enhanced to include self-care plans that were based on patient reporting of symptoms. Fewer participants completed the study in the UC HAT, compared with the control, group (56% vs 72%).8 We theorized that participant dropout was higher in the UC HAT group because of the requirement for a technician to visit the home to install or service the system. Hence, as part of a randomized controlled trial, our group has collaborated with the University of Pittsburgh and Vanderbilt University to assess a new telemedicine system that monitors patients by using text messaging.9 Three hundred forty-eight patients were recruited for this ongoing clinical trial. Thus far, 83%–84% of participants in the intervention arms have completed the 1-year study.

Elkjaer et al. evaluated the impact of a web-based treatment program and patient education center in a convenience sample of patients with UC.10 All 21 patients reported the ability to initiate a self-care plan. Furthermore, participants experienced improvements in knowledge after interaction with the patient education center.10 The web-based self-management and treatment approach was compared with standard of care in 333 patients with mild-to-moderate UC from Ireland and Denmark.11 Only 135 patients (41%) completed the 1-year study. Web subjects were more adherent with acute treatment, demonstrated improved disease knowledge and quality of life, experienced shorter relapses, and had fewer office and urgent care visits. Conversely, web group patients generated more emails and telephone calls. In the Irish arm, the results were similar; however, there was no difference in quality of life between groups, and the relapse rate was higher in the web group, compared with controls.11 A 2012 study by the same group investigated the efficacy of web-based monitoring of Crohn’s disease activity for individualized dosing of infliximab maintenance therapy. Twenty-seven patients were enrolled; 17 completed 52 weeks and 6 completed 26 weeks of follow-up. Patients recorded their symptoms weekly via a web-based portal; on the basis of symptom scores, patients were instructed to contact their physician for an infliximab infusion. Fifty percent of the patients were able to tolerate intervals greater than 8 weeks, whereas 36% required shorter intervals.12 This concept of web-based personalized treatment was further investigated in a 2014 study evaluating 86 patients with mild-to-moderate UC. Mesalamine treatment was individualized on the basis of a composite index of clinical symptoms and fecal calprotectin levels. Use of the web application was associated with decreased disease activity scores and lower fecal calprotectin levels despite dose reduction in 88% of patients at week 12.13

The eIBD program developed at the University of California, Los Angeles, also uses a web-based platform to monitor patients. After an initial training session with an IBD nurse specialist, patients are able to view clinical results and view and update their disease activity status, quality of life, and work productivity remotely. Patients interact with the eIBD program by using a tablet or home computer. Self-monitoring was found to correlate well with an in-person assessment of symptoms and disease activity.14 Patient care is organized into evidence-based pathways on the basis of disease status and the medication regimen. Each pathway has a defined number of clinic and electronic visits and laboratory sets. Patients can also access support programs such as My Academy, My Work, My Coach, My Physical Fitness, and My Diet. When University of California, Los Angeles, IBD patients were compared with matched controls by using an administrative claims database, they were significantly less likely to use steroids and had fewer hospitalizations and emergency department visits.15

HealthPROMISE is an application developed at Mount Sinai to collect patient-reported outcomes and to provide decision support. Patient-reported symptoms and quality of life are integrated into the electronic medical records system; providers can view the information in real time to better manage their panel of patients. HealthPROMISE is currently being evaluated as part of a pragmatic, multicenter, randomized controlled trial.16 EncephalApp is a mobile phone application used to assess patients for hepatic encephalopathy. The application was tested in 167 cirrhotic patients, 38% of whom had overt encephalopathy, and 114 controls. The application was shown to have excellent discriminant ability to detect encephalopathy, and importantly, EnecphalApp times correlated with motor vehicle accidents and illegal turns in a driving simulation test.17 A number of other mobile applications have been developed to support patients with chronic illnesses. These applications can be integrated with wearable devices, and some have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.18

Telehealth and teleconsultation

Advancements in telemedicine have outpaced the ability of legislators and institutional officials to provide oversight on legal and regulatory issues. Each state sets requirements for providers to engage in telehealth activities. The ATA published the State Telemedicine Gap Analysis to address specific requirements and limitations for each state.19 Issues addressed in this document include the requirement for a face-to-face visit before a telehealth visit, informed consent, and interstate practice. Virtually all states have barriers to providing telemedicine services unless the provider is licensed in the state where the patient resides. To promote telemedicine, the Federation of State Medical Boards proposed the development of an Interstate Licensure Compact in which 17 states participate (AL, AZ, CO, ID, IL, IA, KS, MN, MS, MT, NV, NH, SD, UT, WV, WI, and WY).20 Two key principles include defining the practice of medicine as the location in which the patient resides and placing the provider under the jurisdiction of the state in which the practice occurs. The TELE-MED Act of 2015 has proposed allowing Medicare physicians to provide telehealth services to patients regardless of the state in which they reside.21 In regard to liability, the number of malpractice cases involving telemedicine services is low; most are related to e-prescribing, as opposed to care provided during teleconsultation services.22

However, some unique liability issues relative to telehealth encounters exist. First, when considering standard of care, what do you compare a telemedicine encounter with? Hardware or software malfunctions can occur, with a subsequent inability to provide the telemedicine service. Loss of protected health information through hackers or equipment failure is another potential threat. Reimbursement for telehealth services is also regulated by states and is subject to wide variability; 29 states have laws in place requiring private payers to reimburse for telehealth services at the same level as an in-person encounter.19 The ATA recently published an analysis of issues related to reimbursements.23 In addition to parity, key issues that must be addressed include the failure of the majority of state health plans to provide coverage for telehealth services to employees, restrictions on providing telehealth in nonrural settings, restrictions that are based on the type of health care provider, and restrictions on home monitoring.

The Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., offers outreach to its health system affiliates via a secure video conferencing platform to allow face-to-face consultations for patients with IBD. Consultative appointments are scheduled during preassigned blocks of outreach time on the clinician’s calendar. A nurse transcribes any recommendation that requires an order from the referring gastroenterologist. Health care providers offering video consultation are required to have a medical license for the state in which the patient resides and to be credentialed by the facility to which the Mayo Clinic provides services and the payer reimbursing for the service. The majority of consultations are for discussions regarding medical management: when to start a biologic, safety concerns, monitoring strategies, or for a second opinion regarding the need for surgery for refractory UC or fibrostenotic Crohn’s disease. Access to imaging and laboratory work is facilitated through previsit evaluation performed by a nurse in the referring practice.

If services are provided via consultation to a patient at a non–Mayo Clinic facility via the Affiliated Care Network, there is a legal contract outlining reimbursement as well as terms and conditions. For asynchronous consultation where there is interaction with a provider but the patient is not directly involved (no face-to-face consultation), the practice of medicine regulations vary from state to state as outlined above. Credentialing is not required for provider-to-provider consultation at each site but sometimes a license is. However, for all states, electronic health record documentation of the clinical question and recommendations is important. Substantial administrative infrastructure is required to manage the quality of e-consult responses so that they are timely and the clinical notes meet the needs of the requesting provider. This is supported by a secure online portal that exchanges electronic health record information and the clinical note generated. Mayo Clinic providers are licensed for multiple states to provide medical consultations to various affiliated hospitals throughout the United States. The consulting physician always has the option to recommend a full face-to-face consultation if review of the records provided indicates the patient appears to be too complicated. The telehealth efforts at the Mayo Clinic are not isolated to gastroenterology; it is estimated that, through expanded use of telehealth, Mayo Clinic will provide care nationally and internationally for 200 million people by 2020.24

From April 2015 to May 2016, at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, we conducted 89 telehealth visits. According to state regulations and payer restrictions on reimbursement, patients were eligible to undergo telehealth visits if they had a prior face-to-face visit and were insured by Blue Cross Blue Shield. Eligible patients provided informed consent to participate in the telehealth visit. Patients received an email with instructions on how to download the required software (VidyoDesktop version 3.0.4[001]; Vidyo, Hackensack, N.J.) onto the patient’s home computer, tablet, or smartphone. An office assistant conducted a test visit to make sure that the connection was adequate. Eighty-three percent of patients reported that using the system was not complicated at all or only slightly complicated. Seventy-one percent reported that the telehealth visit took significantly less or less time than a routine encounter; 88% said that all their concerns were addressed during the telehealth visit. All patients felt that telehealth visits were more convenient than a face-to-face encounter; 53% and 41% reported that the telehealth visit saved them 1-3 hours and more than 3 hours, respectively. Ninety-four percent reported they would definitely like to have a telehealth visit in the future.

Teleconferencing

Project Extension for Community Health Care Outcomes (ECHO) was originally designed to provide specialist support for treatment of hepatitis C to primary care providers (PCPs) in rural New Mexico and the prison health system. The ECHO model leverages video teleconferencing to provide ongoing assistance from specialists to PCPs for management of cases, treatment plans, and monitoring and also provides case-based learning to increase PCP knowledge and opportunities to participate in research.25 A survey of 29 providers participating in Project ECHO revealed that more than 90% of respondents felt comfortable with management of hepatitis C as a consequence of using the program.26 Subsequently, a prospective cohort study was conducted to compare outcomes of treatment of hepatitis C between the University of New Mexico hepatitis C virus clinic and PCPs at 21 ECHO sites. In the 407Four hundred seven patients who were included in the cohort study,; sustained virologic response was obtained in 57.5% and 58.2% of patients treated at University of New Mexico and ECHO sites, respectively. Response rates did not differ by site according to genotype. Adverse events were lower at ECHO sites, compared with the hepatitis C virus clinic (6.9% vs. 13.7%, respectively).27 With a combination of funding from the state government and external funding agencies, Project ECHO now provides support from specialists to the community for 18 other chronic conditions, including but not limited to diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus, substance abuse, and high-risk pregnancies. Similar approaches have been proposed to create multidisciplinary teams for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis.28

The Inflammatory Bowel Disease Live Inter-institutional and Interdisciplinary Videoconference Education (IBD LIVE) is a national weekly teleconference that brings together gastroenterologists (adult and pediatric), surgeons, radiologists, pathologists, and medical subspecialists from multiple institutions to discuss the management of complex IBD cases. IBD LIVE is continuing medical education–accredited and is published quarterly in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Each 1-hour conference covers two cases equally. After the initial presentation, the moderator summarizes the case and asks faculty to provide their opinion on management. Because many of the cases presented are quite complex, it is common for subspecialists from other disciplines to join the conference to provide clarity.29 The interaction among the various centers has been more than a means of obtaining continuing medical education. In many cases, referrals to other centers have been expedited because one center may offer a service not available at the “home” institution. Providers also use the summary and recommendations to help inform decisions in management of their respective patients. Exchange of ideas has resulted in collaborative research and quality improvement programs without requiring travel and/or absence from clinical duties.

Conclusions

The use of telemedicine in the care of patients with digestive diseases is expanding beyond telephone triage to include remote monitoring and self-care, telehealth visits, and teleconferencing. It is inevitable that use of these services will continue to increase to improve clinical care, to provide quality metrics, to increase access to gastroenterology care and tertiary referral expertise, to improve efficiency of health care delivery, and to decrease costs. Investment in telehealth by venture capitalists has increased fourfold from $1.1 to $4.3 billion from 2011 to 2015.30 Unfortunately, barriers to providing health care remotely continue. These include technological barriers for many practices, the requirement for providers to be licensed and credentialed in multiple states and institutions respectively, unique liability concerns, difficulties with reimbursement, and differential access to telehealth services among patients. In addition, patient engagement with remote monitoring has been disappointing, likely because of poor system designs and limited involvement with patients in design of the monitoring systems. It is likely that payers and states will slowly increase reimbursement and ease use of telemedicine as they learn how telemedicine can decrease costs and improve the efficiency of health care delivery.

Dr. Cross is in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, University of Maryland, Baltimore. Dr. Kane is in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. This research was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R01HS018975-01A1). The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. What is telemedicine? American Telemedicine Association. Available from http://www.americantelemed.org/main/about/about-telemedicine. Accessed September 2, 2016.

2. Ramos-Rivers, C., Regueiro, M., Vargas, E.J., et al. Association between telephone activity and features of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(6):986-94.

3. Patil, S.A., Cross, R.K. Can you hear me now? Frequent telephone encounters for management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(6):995-6.

4. Raine L. Cell phone ownership hits 91% of adults. PewResearch Center. 2013. Available from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/06/06/cell-phone-ownership-hits-91-of-adults/. Accessed September 2, 2016.

5. Ray, K.N., Chari, A.V., Engberg, J., et al. Disparities in time spent seeking medical care in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1983-6.

6. Cross, R.K., Arora, M., Finkelstein, J. Acceptance of telemanagement is high in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(3):200-8.

7. Cross, R.K., Finkelstein, J. Feasibility and acceptance of a home telemanagement system in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A 6-month pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(2):357-64.

8. Cross, R.K., Cheevers, N., Rustgi, A., et al. Randomized, controlled trial of home telemanagement in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC HAT). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(6):1018-25.

9. Cross, R.K., Jambaulikar, G., Langenberg, P., et al. TELEmedicine for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (TELE-IBD): design and implementation of randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;42:132-44.

10. Elkjaer, M., Burisch, J., Avnstrom, S., et al. Development of a Web-based concept for patients with ulcerative colitis and 5-aminosalicylic acid treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22(6):695-704.

11. Elkjaer, M., Shuhaibar, M., Burisch, J., et al. E-health empowers patients with ulcerative colitis: A randomised controlled trial of the web-guided ‘Constant-care’ approach. Gut. 2010;59(12):1652-61.

12. Pedersen, N., Elkjaer, M., Duricova, D., et al. eHealth: individualisation of infliximab treatment and disease course via a self-managed web-based solution in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(9):840-9.

13. Pedersen, N., Thielsen, P., Martinsen, L., et al. eHealth: individualization of mesalazine treatment through a self-managed web-based solution in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(12):2276-85.

14. Van Deen, W.K., van der Meulen-de Jong, A.E., Parekh, N.K., et al. Development and validation of an inflammatory bowel diseases monitoring index for use with mobile health technologies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Dec;14(12):1742-50 Nove 18.

15. van Deen, W.K., Ozbay, A.B., Skup, M., et al. The impact of a value-based health program for inflammatory bowel disease management on healthcare utilization. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:S123-4.

16. Atreja, A., Khan, S., Rogers, J.D., et al. Impact of the mobile HealthPROMISE platform on the quality of care and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: study protocol of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4:e23.

17. Bajaj, J.S., Heuman, D.M., Sterling, R.K. et al. Validation of EncephalApp, smartphone-based Stroop test, for the diagnosis of covert hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1828-35 e1.

18. Riaz, M.S., Atreja, A. Personalized technologies in chronic gastrointestinal disorders: self-monitoring and remote sensor technologies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1697-705.

19. Thomas L, Capistrant G. 50 state telemedicine gaps analysis physician practice standards & licensure: American Telemedicine Association. 2014. Available from http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/50-state-telemedicine-gaps-analysis–physician-practice-standards-licensure.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2016.

20. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact: federation of state medical boards. Available from http://www.fsmb.org/policy/interstate-model-compact. Accessed September 2, 2016.

21. TELE-MED Act of 2015. Stat. H.R. 3081, 114th Congress (2015-2016).

22. Natoli, C.M. Summary of findings: malpractice and telemedicine. Center for Telehealth and EHealth Law, Washington, DC; 2009.

23. The National Conference of State Legislatures. Available from http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-coverage-for-telehealth-services.aspx. Accessed September 2, 2016.

24. Larsen E, Diamond D. Why Mayo Clinic’s CEO wants to serve 200 million patients-and how he plans to do it. 2014. Available from https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2014/07/23/lessons-from-the-c-suite-mayo-clinic. Accessed September 2, 2016.

25. Arora, S., Thornton, K., Jenkusky, S.M., et al. Project ECHO: linking university specialists with rural and prison-based clinicians to improve care for people with chronic hepatitis C in New Mexico. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:74-7.

26. Arora, S., Geppert, C.M., Kalishman, S., et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82:154-60.

27. Arora, S., Thornton, K., Murata, G., et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2199-207.

28. Naugler, W.E., Alsina, A.E., Frenette, C.T., et al. Building the multidisciplinary team for management of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:827-35.

29. Regueiro, M.D., Greer, J.B., Binion, D.G., et al. The inflammatory bowel disease live interinstitutional and interdisciplinary videoconference education (IBD LIVE) series. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1687-95.

30. Wang T., King E., Perman M., et al. Digital health funding: 2015 year in review. 2016. Available from http://rockhealth.com/reports/digital-health-funding-2015-year-in-review. Accessed. September 2, 2016.

Two trends in health care delivery that will continue unabated are a) reimbursement pressure and b) increasing demand for our services. Practices that care for patients with complex and chronic conditions are exploring innovative means to expand their care footprint in an economically viable way. One approach currently being used by many health systems is telemedicine. Telemedicine is care delivered remotely using some type of electronic communication. Potentially, telemedicine will allow us to provide specialty services remotely to primary care physicians or even patients. The University of Michigan inflammatory bowel disease program is piloting remote video conferencing, integrated within the electronic medical record system, to provide specialty gastrointestinal consultation directly to Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis patients within their homes. The University of Michigan Health System has an office ready to arrange rapid teleconsultation for any provider. Payment for services has been secured from several payers after health system negotiations. This practice is well established in multiple specialties and settings. In this month’s column, two telemedicine experts review the state of the field, so you too can participate. This innovation is something you should consider for your practice. Technology and payment mechanisms are now available.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

As defined by the American Telemedicine Association (ATA), telemedicine is the exchange of medical information from one site to another via electronic communication to improve a patient’s clinical health status.1 If we include care provided over the telephone via providers and nurses between office visits, telemedicine has been practiced for decades. A recent study from the University of Pittsburgh documented 32,667 phone calls from 3,118 patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in 2010. Seventy-five percent of these calls were related to patient concerns or were generated by the nurse because of changes in the treatment plan.2 If these results are applied to a representative work week, busy IBD centers typically handle more than 100 phone calls per day.3 Telemedicine in clinical practice has expanded to include a variety of modalities such as two-way video, email, or secure messaging through electronic medical records systems, smartphones, wireless tools, and other forms of telecommunication technology (see Figure 1). The increase in use of telemedicine in practice has been driven by a number of factors.

First, it is almost universal that patients have access to a computer and/or cellular telephone. According to the Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project, as of May 2013, 91% of adults are using cellphones.4 As patients have become more connected digitally, it is natural that they desire delivery of services, including health care services, electronically. Second, despite advances in medical, endoscopic, and surgical treatment, many patients still have suboptimal outcomes. There are many reasons for this, including but not limited to nonadherence, poor patient education, inadequate monitoring of symptoms and side effects, concurrent psychiatric disease, comorbid medical conditions, low self-efficacy, and limited access to health care; these issues can be addressed, at least in part, by telemedicine. Finally, patients are also seeking more efficient and convenient ways to receive their care,; including travel and wait times, an average office visit takes up to 2 hours.5

Enhanced monitoring and self-care through use of telemedicine technologies

Several groups have implemented telemedicine to improve monitoring and self-care in patients with IBD. Our group at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, has developed several systems to improve care as part of research protocols. Our first telemedicine system included a laptop computer and electronic weight scale connected telephonically to a server. Patients were asked questions about bowel symptoms, medication use, side effects, and body weight measurements. They also received educational messages. This system, IBD Home Automated Telemanagement (HAT), required installation in the patient’s home by a technical team. Our preliminary results demonstrated that patients were very receptive of the technology.6 In a small pilot study (n = 34), we demonstrated that 88% of patients were adherent to self-assessment during a period of 6 months. In addition, patients experienced a reduction in disease activity, improved quality of life, and increased disease state awareness.7 In a small, randomized, controlled follow-up trial, we demonstrated that use of an ulcerative colitis (UC) telemanagement system (UC HAT) resulted in improved quality of life and decreased disease activity from baseline during 1 year compared with controls. The UC HAT system was enhanced to include self-care plans that were based on patient reporting of symptoms. Fewer participants completed the study in the UC HAT, compared with the control, group (56% vs 72%).8 We theorized that participant dropout was higher in the UC HAT group because of the requirement for a technician to visit the home to install or service the system. Hence, as part of a randomized controlled trial, our group has collaborated with the University of Pittsburgh and Vanderbilt University to assess a new telemedicine system that monitors patients by using text messaging.9 Three hundred forty-eight patients were recruited for this ongoing clinical trial. Thus far, 83%–84% of participants in the intervention arms have completed the 1-year study.

Elkjaer et al. evaluated the impact of a web-based treatment program and patient education center in a convenience sample of patients with UC.10 All 21 patients reported the ability to initiate a self-care plan. Furthermore, participants experienced improvements in knowledge after interaction with the patient education center.10 The web-based self-management and treatment approach was compared with standard of care in 333 patients with mild-to-moderate UC from Ireland and Denmark.11 Only 135 patients (41%) completed the 1-year study. Web subjects were more adherent with acute treatment, demonstrated improved disease knowledge and quality of life, experienced shorter relapses, and had fewer office and urgent care visits. Conversely, web group patients generated more emails and telephone calls. In the Irish arm, the results were similar; however, there was no difference in quality of life between groups, and the relapse rate was higher in the web group, compared with controls.11 A 2012 study by the same group investigated the efficacy of web-based monitoring of Crohn’s disease activity for individualized dosing of infliximab maintenance therapy. Twenty-seven patients were enrolled; 17 completed 52 weeks and 6 completed 26 weeks of follow-up. Patients recorded their symptoms weekly via a web-based portal; on the basis of symptom scores, patients were instructed to contact their physician for an infliximab infusion. Fifty percent of the patients were able to tolerate intervals greater than 8 weeks, whereas 36% required shorter intervals.12 This concept of web-based personalized treatment was further investigated in a 2014 study evaluating 86 patients with mild-to-moderate UC. Mesalamine treatment was individualized on the basis of a composite index of clinical symptoms and fecal calprotectin levels. Use of the web application was associated with decreased disease activity scores and lower fecal calprotectin levels despite dose reduction in 88% of patients at week 12.13

The eIBD program developed at the University of California, Los Angeles, also uses a web-based platform to monitor patients. After an initial training session with an IBD nurse specialist, patients are able to view clinical results and view and update their disease activity status, quality of life, and work productivity remotely. Patients interact with the eIBD program by using a tablet or home computer. Self-monitoring was found to correlate well with an in-person assessment of symptoms and disease activity.14 Patient care is organized into evidence-based pathways on the basis of disease status and the medication regimen. Each pathway has a defined number of clinic and electronic visits and laboratory sets. Patients can also access support programs such as My Academy, My Work, My Coach, My Physical Fitness, and My Diet. When University of California, Los Angeles, IBD patients were compared with matched controls by using an administrative claims database, they were significantly less likely to use steroids and had fewer hospitalizations and emergency department visits.15

HealthPROMISE is an application developed at Mount Sinai to collect patient-reported outcomes and to provide decision support. Patient-reported symptoms and quality of life are integrated into the electronic medical records system; providers can view the information in real time to better manage their panel of patients. HealthPROMISE is currently being evaluated as part of a pragmatic, multicenter, randomized controlled trial.16 EncephalApp is a mobile phone application used to assess patients for hepatic encephalopathy. The application was tested in 167 cirrhotic patients, 38% of whom had overt encephalopathy, and 114 controls. The application was shown to have excellent discriminant ability to detect encephalopathy, and importantly, EnecphalApp times correlated with motor vehicle accidents and illegal turns in a driving simulation test.17 A number of other mobile applications have been developed to support patients with chronic illnesses. These applications can be integrated with wearable devices, and some have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.18

Telehealth and teleconsultation

Advancements in telemedicine have outpaced the ability of legislators and institutional officials to provide oversight on legal and regulatory issues. Each state sets requirements for providers to engage in telehealth activities. The ATA published the State Telemedicine Gap Analysis to address specific requirements and limitations for each state.19 Issues addressed in this document include the requirement for a face-to-face visit before a telehealth visit, informed consent, and interstate practice. Virtually all states have barriers to providing telemedicine services unless the provider is licensed in the state where the patient resides. To promote telemedicine, the Federation of State Medical Boards proposed the development of an Interstate Licensure Compact in which 17 states participate (AL, AZ, CO, ID, IL, IA, KS, MN, MS, MT, NV, NH, SD, UT, WV, WI, and WY).20 Two key principles include defining the practice of medicine as the location in which the patient resides and placing the provider under the jurisdiction of the state in which the practice occurs. The TELE-MED Act of 2015 has proposed allowing Medicare physicians to provide telehealth services to patients regardless of the state in which they reside.21 In regard to liability, the number of malpractice cases involving telemedicine services is low; most are related to e-prescribing, as opposed to care provided during teleconsultation services.22

However, some unique liability issues relative to telehealth encounters exist. First, when considering standard of care, what do you compare a telemedicine encounter with? Hardware or software malfunctions can occur, with a subsequent inability to provide the telemedicine service. Loss of protected health information through hackers or equipment failure is another potential threat. Reimbursement for telehealth services is also regulated by states and is subject to wide variability; 29 states have laws in place requiring private payers to reimburse for telehealth services at the same level as an in-person encounter.19 The ATA recently published an analysis of issues related to reimbursements.23 In addition to parity, key issues that must be addressed include the failure of the majority of state health plans to provide coverage for telehealth services to employees, restrictions on providing telehealth in nonrural settings, restrictions that are based on the type of health care provider, and restrictions on home monitoring.

The Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., offers outreach to its health system affiliates via a secure video conferencing platform to allow face-to-face consultations for patients with IBD. Consultative appointments are scheduled during preassigned blocks of outreach time on the clinician’s calendar. A nurse transcribes any recommendation that requires an order from the referring gastroenterologist. Health care providers offering video consultation are required to have a medical license for the state in which the patient resides and to be credentialed by the facility to which the Mayo Clinic provides services and the payer reimbursing for the service. The majority of consultations are for discussions regarding medical management: when to start a biologic, safety concerns, monitoring strategies, or for a second opinion regarding the need for surgery for refractory UC or fibrostenotic Crohn’s disease. Access to imaging and laboratory work is facilitated through previsit evaluation performed by a nurse in the referring practice.