User login

Drug receives fast track designation for follicular lymphoma

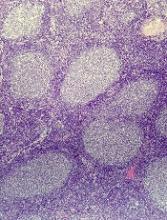

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to the EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat as a treatment for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma, with or without EZH2-activating mutations.

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review.

In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the new drug application or biologic license application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

Tazemetostat also has fast track designation from the FDA as a treatment for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with EZH2-activating mutations.

Tazemetostat is under investigation as monotherapy and in combination with other agents as a treatment for multiple cancers.

Results from a phase 1 study suggested tazemetostat can produce durable responses in patients with advanced non-Hodgkin lymphomas, including follicular lymphoma and DLBCL. The study was presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting.

Tazemetostat is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial of adults with relapsed or refractory DLBCL or follicular lymphoma.

Interim efficacy and safety data from this study are scheduled to be presented at the International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma (ICML) in Lugano, Switzerland, on June 14, 2017, at 2:00 pm CET.

Tazemetostat is being developed by Epizyme, Inc. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to the EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat as a treatment for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma, with or without EZH2-activating mutations.

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review.

In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the new drug application or biologic license application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

Tazemetostat also has fast track designation from the FDA as a treatment for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with EZH2-activating mutations.

Tazemetostat is under investigation as monotherapy and in combination with other agents as a treatment for multiple cancers.

Results from a phase 1 study suggested tazemetostat can produce durable responses in patients with advanced non-Hodgkin lymphomas, including follicular lymphoma and DLBCL. The study was presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting.

Tazemetostat is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial of adults with relapsed or refractory DLBCL or follicular lymphoma.

Interim efficacy and safety data from this study are scheduled to be presented at the International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma (ICML) in Lugano, Switzerland, on June 14, 2017, at 2:00 pm CET.

Tazemetostat is being developed by Epizyme, Inc. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to the EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat as a treatment for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma, with or without EZH2-activating mutations.

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review.

In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the new drug application or biologic license application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

Tazemetostat also has fast track designation from the FDA as a treatment for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with EZH2-activating mutations.

Tazemetostat is under investigation as monotherapy and in combination with other agents as a treatment for multiple cancers.

Results from a phase 1 study suggested tazemetostat can produce durable responses in patients with advanced non-Hodgkin lymphomas, including follicular lymphoma and DLBCL. The study was presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting.

Tazemetostat is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial of adults with relapsed or refractory DLBCL or follicular lymphoma.

Interim efficacy and safety data from this study are scheduled to be presented at the International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma (ICML) in Lugano, Switzerland, on June 14, 2017, at 2:00 pm CET.

Tazemetostat is being developed by Epizyme, Inc. ![]()

Treatment granted PRIME designation for hemophilia B

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has granted AMT-060 access to the agency’s PRIority MEdicines (PRIME) program.

AMT-060 is an investigational gene therapy intended for the treatment of patients with severe hemophilia B.

The goal of the EMA’s PRIME program is to accelerate the development of therapies that may offer a major advantage over existing treatments or benefit patients with no treatment options.

Through PRIME, the EMA offers early and enhanced support to developers in order to optimize development plans and speed regulatory evaluations to potentially bring therapies to patients more quickly.

To be accepted for PRIME, a therapy must demonstrate the potential to benefit patients with unmet medical need through early clinical or nonclinical data.

About AMT-060

AMT-060 consists of a codon-optimized wild-type factor IX (FIX) gene cassette, the LP1 liver promoter, and an AAV5 viral vector manufactured by uniQure using its proprietary insect cell-based technology platform. UniQure is the company developing AMT-060.

The EMA’s decision to grant AMT-060 access to the PRIME program is based on results from an ongoing phase 1/2 study. Updated data from this study were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 2314).

The presentation included data on 10 patients. All patients had severe or moderately severe hemophilia at baseline, including documented FIX levels less than 1% to 2% of normal, and required chronic infusions of prophylactic or on-demand FIX therapy at the time of enrollment.

Each patient received a 1-time, 30-minute, intravenous dose of AMT-060, without the use of corticosteroids. Five patients received AMT-060 at 5 x 1012 gc/kg, and 5 received AMT-060 at 2 x 1013 gc/kg.

Patients in the low-dose cohort were followed for up to 52 weeks, and those in the higher-dose cohort were followed for up to 31 weeks.

Data from the higher-dose cohort showed a dose response with improvement in disease state in all 5 patients. Four patients who previously required prophylactic FIX therapy were able to stop this therapy.

As of the data cutoff date, 1 unconfirmed spontaneous bleed had been reported during an aggregate of 94 weeks of follow-up after the discontinuation of prophylaxis.

Researchers previously reported that 4 patients in the low-dose cohort were able to discontinue prophylactic therapy. The 1 patient who remained on prophylaxis sustained an improved disease phenotype and also required materially less FIX concentrate after treatment with AMT-060.

According to uniQure, all 5 patients in the low-dose cohort maintained “constant and clinically meaningful” levels of FIX activity for up to 52 weeks post-treatment. In fact, there were no spontaneous bleeds in these patients in the last 14 weeks of observation.

uniQure also said AMT-060 was well-tolerated, and there have been no severe adverse events.

Three patients (2 in the higher-dose cohort and 1 previously reported from the low-dose cohort) experienced mild, asymptomatic elevations of alanine aminotransferase and received a tapering course of corticosteroids per protocol.

These temporary alanine aminotransferase elevations were not associated with any loss of endogenous FIX activity or T-cell response to the AAV5 capsid.

None of the patients in either cohort have developed inhibitory antibodies against FIX, and none of the patients screened tested positive for anti-AAV5 antibodies. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has granted AMT-060 access to the agency’s PRIority MEdicines (PRIME) program.

AMT-060 is an investigational gene therapy intended for the treatment of patients with severe hemophilia B.

The goal of the EMA’s PRIME program is to accelerate the development of therapies that may offer a major advantage over existing treatments or benefit patients with no treatment options.

Through PRIME, the EMA offers early and enhanced support to developers in order to optimize development plans and speed regulatory evaluations to potentially bring therapies to patients more quickly.

To be accepted for PRIME, a therapy must demonstrate the potential to benefit patients with unmet medical need through early clinical or nonclinical data.

About AMT-060

AMT-060 consists of a codon-optimized wild-type factor IX (FIX) gene cassette, the LP1 liver promoter, and an AAV5 viral vector manufactured by uniQure using its proprietary insect cell-based technology platform. UniQure is the company developing AMT-060.

The EMA’s decision to grant AMT-060 access to the PRIME program is based on results from an ongoing phase 1/2 study. Updated data from this study were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 2314).

The presentation included data on 10 patients. All patients had severe or moderately severe hemophilia at baseline, including documented FIX levels less than 1% to 2% of normal, and required chronic infusions of prophylactic or on-demand FIX therapy at the time of enrollment.

Each patient received a 1-time, 30-minute, intravenous dose of AMT-060, without the use of corticosteroids. Five patients received AMT-060 at 5 x 1012 gc/kg, and 5 received AMT-060 at 2 x 1013 gc/kg.

Patients in the low-dose cohort were followed for up to 52 weeks, and those in the higher-dose cohort were followed for up to 31 weeks.

Data from the higher-dose cohort showed a dose response with improvement in disease state in all 5 patients. Four patients who previously required prophylactic FIX therapy were able to stop this therapy.

As of the data cutoff date, 1 unconfirmed spontaneous bleed had been reported during an aggregate of 94 weeks of follow-up after the discontinuation of prophylaxis.

Researchers previously reported that 4 patients in the low-dose cohort were able to discontinue prophylactic therapy. The 1 patient who remained on prophylaxis sustained an improved disease phenotype and also required materially less FIX concentrate after treatment with AMT-060.

According to uniQure, all 5 patients in the low-dose cohort maintained “constant and clinically meaningful” levels of FIX activity for up to 52 weeks post-treatment. In fact, there were no spontaneous bleeds in these patients in the last 14 weeks of observation.

uniQure also said AMT-060 was well-tolerated, and there have been no severe adverse events.

Three patients (2 in the higher-dose cohort and 1 previously reported from the low-dose cohort) experienced mild, asymptomatic elevations of alanine aminotransferase and received a tapering course of corticosteroids per protocol.

These temporary alanine aminotransferase elevations were not associated with any loss of endogenous FIX activity or T-cell response to the AAV5 capsid.

None of the patients in either cohort have developed inhibitory antibodies against FIX, and none of the patients screened tested positive for anti-AAV5 antibodies. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has granted AMT-060 access to the agency’s PRIority MEdicines (PRIME) program.

AMT-060 is an investigational gene therapy intended for the treatment of patients with severe hemophilia B.

The goal of the EMA’s PRIME program is to accelerate the development of therapies that may offer a major advantage over existing treatments or benefit patients with no treatment options.

Through PRIME, the EMA offers early and enhanced support to developers in order to optimize development plans and speed regulatory evaluations to potentially bring therapies to patients more quickly.

To be accepted for PRIME, a therapy must demonstrate the potential to benefit patients with unmet medical need through early clinical or nonclinical data.

About AMT-060

AMT-060 consists of a codon-optimized wild-type factor IX (FIX) gene cassette, the LP1 liver promoter, and an AAV5 viral vector manufactured by uniQure using its proprietary insect cell-based technology platform. UniQure is the company developing AMT-060.

The EMA’s decision to grant AMT-060 access to the PRIME program is based on results from an ongoing phase 1/2 study. Updated data from this study were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 2314).

The presentation included data on 10 patients. All patients had severe or moderately severe hemophilia at baseline, including documented FIX levels less than 1% to 2% of normal, and required chronic infusions of prophylactic or on-demand FIX therapy at the time of enrollment.

Each patient received a 1-time, 30-minute, intravenous dose of AMT-060, without the use of corticosteroids. Five patients received AMT-060 at 5 x 1012 gc/kg, and 5 received AMT-060 at 2 x 1013 gc/kg.

Patients in the low-dose cohort were followed for up to 52 weeks, and those in the higher-dose cohort were followed for up to 31 weeks.

Data from the higher-dose cohort showed a dose response with improvement in disease state in all 5 patients. Four patients who previously required prophylactic FIX therapy were able to stop this therapy.

As of the data cutoff date, 1 unconfirmed spontaneous bleed had been reported during an aggregate of 94 weeks of follow-up after the discontinuation of prophylaxis.

Researchers previously reported that 4 patients in the low-dose cohort were able to discontinue prophylactic therapy. The 1 patient who remained on prophylaxis sustained an improved disease phenotype and also required materially less FIX concentrate after treatment with AMT-060.

According to uniQure, all 5 patients in the low-dose cohort maintained “constant and clinically meaningful” levels of FIX activity for up to 52 weeks post-treatment. In fact, there were no spontaneous bleeds in these patients in the last 14 weeks of observation.

uniQure also said AMT-060 was well-tolerated, and there have been no severe adverse events.

Three patients (2 in the higher-dose cohort and 1 previously reported from the low-dose cohort) experienced mild, asymptomatic elevations of alanine aminotransferase and received a tapering course of corticosteroids per protocol.

These temporary alanine aminotransferase elevations were not associated with any loss of endogenous FIX activity or T-cell response to the AAV5 capsid.

None of the patients in either cohort have developed inhibitory antibodies against FIX, and none of the patients screened tested positive for anti-AAV5 antibodies. ![]()

FDA issues warnings about illegal ‘anticancer’ products

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has posted warning letters addressed to 14 US-based companies illegally selling more than 65 products.

The companies are fraudulently claiming that these products prevent, diagnose, treat, or cure cancer.

The products are being marketed and sold without FDA approval, most commonly on websites and social media platforms.

“Consumers should not use these or similar unproven products because they may be unsafe and could prevent a person from seeking an appropriate and potentially life-saving cancer diagnosis or treatment,” said Douglas W. Stearn, director of the Office of Enforcement and Import Operations in the FDA’s Office of Regulatory Affairs.

“We encourage people to remain vigilant whether online or in a store, and avoid purchasing products marketed to treat cancer without any proof they will work. Patients should consult a healthcare professional about proper prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

It is a violation of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act to market and sell products that claim to prevent, diagnose, treat, mitigate, or cure diseases without first demonstrating to the FDA that they are safe and effective for their labeled uses.

The illegally sold products cited in the FDA’s warning letters include a variety of product types, such as pills, topical creams, ointments, oils, drops, syrups, teas, and diagnostics (such as thermography devices).

They include products marketed for use by humans or pets that make illegal, unproven claims regarding preventing, reversing, or curing cancer; killing/inhibiting cancer cells or tumors; or other similar anticancer claims.

The FDA has requested responses from the 14 companies stating how the violations will be corrected. Failure to correct the violations promptly may result in legal action, including product seizure, injunction, and/or criminal prosecution.

As part of the FDA’s effort to protect consumers from cancer health fraud, the FDA has issued more than 90 warning letters in the past 10 years to companies marketing hundreds of fraudulent cancer-related products on websites, social media, and in stores.

Although many of these companies have stopped selling the products or making fraudulent claims, numerous unsafe and unapproved products continue to be sold directly to consumers due, in part, to the ease with which companies can move their marketing operations to new websites.

The FDA continues to monitor and take action against companies promoting and selling unproven treatments in an effort to minimize the potential dangers to consumers and to educate consumers about the risks.

The FDA encourages healthcare professionals and consumers to report adverse reactions associated with these or similar products to the FDA’s MedWatch program. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has posted warning letters addressed to 14 US-based companies illegally selling more than 65 products.

The companies are fraudulently claiming that these products prevent, diagnose, treat, or cure cancer.

The products are being marketed and sold without FDA approval, most commonly on websites and social media platforms.

“Consumers should not use these or similar unproven products because they may be unsafe and could prevent a person from seeking an appropriate and potentially life-saving cancer diagnosis or treatment,” said Douglas W. Stearn, director of the Office of Enforcement and Import Operations in the FDA’s Office of Regulatory Affairs.

“We encourage people to remain vigilant whether online or in a store, and avoid purchasing products marketed to treat cancer without any proof they will work. Patients should consult a healthcare professional about proper prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

It is a violation of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act to market and sell products that claim to prevent, diagnose, treat, mitigate, or cure diseases without first demonstrating to the FDA that they are safe and effective for their labeled uses.

The illegally sold products cited in the FDA’s warning letters include a variety of product types, such as pills, topical creams, ointments, oils, drops, syrups, teas, and diagnostics (such as thermography devices).

They include products marketed for use by humans or pets that make illegal, unproven claims regarding preventing, reversing, or curing cancer; killing/inhibiting cancer cells or tumors; or other similar anticancer claims.

The FDA has requested responses from the 14 companies stating how the violations will be corrected. Failure to correct the violations promptly may result in legal action, including product seizure, injunction, and/or criminal prosecution.

As part of the FDA’s effort to protect consumers from cancer health fraud, the FDA has issued more than 90 warning letters in the past 10 years to companies marketing hundreds of fraudulent cancer-related products on websites, social media, and in stores.

Although many of these companies have stopped selling the products or making fraudulent claims, numerous unsafe and unapproved products continue to be sold directly to consumers due, in part, to the ease with which companies can move their marketing operations to new websites.

The FDA continues to monitor and take action against companies promoting and selling unproven treatments in an effort to minimize the potential dangers to consumers and to educate consumers about the risks.

The FDA encourages healthcare professionals and consumers to report adverse reactions associated with these or similar products to the FDA’s MedWatch program. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has posted warning letters addressed to 14 US-based companies illegally selling more than 65 products.

The companies are fraudulently claiming that these products prevent, diagnose, treat, or cure cancer.

The products are being marketed and sold without FDA approval, most commonly on websites and social media platforms.

“Consumers should not use these or similar unproven products because they may be unsafe and could prevent a person from seeking an appropriate and potentially life-saving cancer diagnosis or treatment,” said Douglas W. Stearn, director of the Office of Enforcement and Import Operations in the FDA’s Office of Regulatory Affairs.

“We encourage people to remain vigilant whether online or in a store, and avoid purchasing products marketed to treat cancer without any proof they will work. Patients should consult a healthcare professional about proper prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

It is a violation of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act to market and sell products that claim to prevent, diagnose, treat, mitigate, or cure diseases without first demonstrating to the FDA that they are safe and effective for their labeled uses.

The illegally sold products cited in the FDA’s warning letters include a variety of product types, such as pills, topical creams, ointments, oils, drops, syrups, teas, and diagnostics (such as thermography devices).

They include products marketed for use by humans or pets that make illegal, unproven claims regarding preventing, reversing, or curing cancer; killing/inhibiting cancer cells or tumors; or other similar anticancer claims.

The FDA has requested responses from the 14 companies stating how the violations will be corrected. Failure to correct the violations promptly may result in legal action, including product seizure, injunction, and/or criminal prosecution.

As part of the FDA’s effort to protect consumers from cancer health fraud, the FDA has issued more than 90 warning letters in the past 10 years to companies marketing hundreds of fraudulent cancer-related products on websites, social media, and in stores.

Although many of these companies have stopped selling the products or making fraudulent claims, numerous unsafe and unapproved products continue to be sold directly to consumers due, in part, to the ease with which companies can move their marketing operations to new websites.

The FDA continues to monitor and take action against companies promoting and selling unproven treatments in an effort to minimize the potential dangers to consumers and to educate consumers about the risks.

The FDA encourages healthcare professionals and consumers to report adverse reactions associated with these or similar products to the FDA’s MedWatch program. ![]()

Use of second-generation antidepressants in older adults is associated with increased hospitalization with hyponatremia

Clinical Question: Is there an increased risk of hyponatremia for older patients who are taking a second-generation antidepressant?

Background: Mood and anxiety disorders affect about one in eight older adults, and second-generation antidepressants are frequently recommended for treatment. A potential adverse effect of these agents is hyponatremia, which can lead to serious sequelae. The aim of this study was to investigate the 30-day risk for hospitalization with hyponatremia in older adults who were newly started on a second-generation antidepressant.

Setting: Ontario, Canada.

Synopsis: Multiple databases were utilized to obtain vital statistics and demographic information, diagnoses, prescriptions, and serum sodium measurements to establish a cohort population. One group of 172,552 was newly prescribed a second-generation antidepressant. A second control group of 297,501 was established in which patients were not prescribed antidepressants. Greedy matching was used to match each user to a nonuser based on similar characteristics of age, sex, evidence of mood disorder, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, or diuretic use. After matching, 138,246 patients remained in each group and were nearly identical for all 10 0 measured characteristics. The primary outcome was that, compared with nonuse, second-generation antidepressant use was associated with higher 30-day risk of hospitalization with hyponatremia (relative risk, 5.46; 95% CI, 4.32-6.91). The secondary outcome showed that, compared with non-use, second-generation antidepressant use was associated with higher 30-day risk for hospitalization with concomitant hyponatremia and delirium (RR, 4.00; 95% CI, 1.74 - 9.16). Additionally, tests for specificity and temporality were employed.

Bottom Line: A robust association between second-generation antidepressant use and hospitalization with hyponatremia was determined in the large population-based cohort study.

Citation: Gandhi S, Shariff SZ, Al-Jaishi A, et al. “Second-generation antidepressants and hyponatremia risk: a population-based cohort study of older adults.” Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 Jan;69(1):87-96.

Dr. Kim is clinical assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical Question: Is there an increased risk of hyponatremia for older patients who are taking a second-generation antidepressant?

Background: Mood and anxiety disorders affect about one in eight older adults, and second-generation antidepressants are frequently recommended for treatment. A potential adverse effect of these agents is hyponatremia, which can lead to serious sequelae. The aim of this study was to investigate the 30-day risk for hospitalization with hyponatremia in older adults who were newly started on a second-generation antidepressant.

Setting: Ontario, Canada.

Synopsis: Multiple databases were utilized to obtain vital statistics and demographic information, diagnoses, prescriptions, and serum sodium measurements to establish a cohort population. One group of 172,552 was newly prescribed a second-generation antidepressant. A second control group of 297,501 was established in which patients were not prescribed antidepressants. Greedy matching was used to match each user to a nonuser based on similar characteristics of age, sex, evidence of mood disorder, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, or diuretic use. After matching, 138,246 patients remained in each group and were nearly identical for all 10 0 measured characteristics. The primary outcome was that, compared with nonuse, second-generation antidepressant use was associated with higher 30-day risk of hospitalization with hyponatremia (relative risk, 5.46; 95% CI, 4.32-6.91). The secondary outcome showed that, compared with non-use, second-generation antidepressant use was associated with higher 30-day risk for hospitalization with concomitant hyponatremia and delirium (RR, 4.00; 95% CI, 1.74 - 9.16). Additionally, tests for specificity and temporality were employed.

Bottom Line: A robust association between second-generation antidepressant use and hospitalization with hyponatremia was determined in the large population-based cohort study.

Citation: Gandhi S, Shariff SZ, Al-Jaishi A, et al. “Second-generation antidepressants and hyponatremia risk: a population-based cohort study of older adults.” Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 Jan;69(1):87-96.

Dr. Kim is clinical assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical Question: Is there an increased risk of hyponatremia for older patients who are taking a second-generation antidepressant?

Background: Mood and anxiety disorders affect about one in eight older adults, and second-generation antidepressants are frequently recommended for treatment. A potential adverse effect of these agents is hyponatremia, which can lead to serious sequelae. The aim of this study was to investigate the 30-day risk for hospitalization with hyponatremia in older adults who were newly started on a second-generation antidepressant.

Setting: Ontario, Canada.

Synopsis: Multiple databases were utilized to obtain vital statistics and demographic information, diagnoses, prescriptions, and serum sodium measurements to establish a cohort population. One group of 172,552 was newly prescribed a second-generation antidepressant. A second control group of 297,501 was established in which patients were not prescribed antidepressants. Greedy matching was used to match each user to a nonuser based on similar characteristics of age, sex, evidence of mood disorder, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, or diuretic use. After matching, 138,246 patients remained in each group and were nearly identical for all 10 0 measured characteristics. The primary outcome was that, compared with nonuse, second-generation antidepressant use was associated with higher 30-day risk of hospitalization with hyponatremia (relative risk, 5.46; 95% CI, 4.32-6.91). The secondary outcome showed that, compared with non-use, second-generation antidepressant use was associated with higher 30-day risk for hospitalization with concomitant hyponatremia and delirium (RR, 4.00; 95% CI, 1.74 - 9.16). Additionally, tests for specificity and temporality were employed.

Bottom Line: A robust association between second-generation antidepressant use and hospitalization with hyponatremia was determined in the large population-based cohort study.

Citation: Gandhi S, Shariff SZ, Al-Jaishi A, et al. “Second-generation antidepressants and hyponatremia risk: a population-based cohort study of older adults.” Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 Jan;69(1):87-96.

Dr. Kim is clinical assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

FDA issues warning to companies selling illegal cancer treatments

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning to 14 U.S. companies that are illegally selling more than 65 products purported to prevent, diagnose, treat, or cure cancer, according to an FDA safety alert.

Product types include pills, topical creams, ointments, oils, drops, syrups, teas, and diagnostic tools. The affected products are usually sold online or through social media.

Find the full safety alert on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning to 14 U.S. companies that are illegally selling more than 65 products purported to prevent, diagnose, treat, or cure cancer, according to an FDA safety alert.

Product types include pills, topical creams, ointments, oils, drops, syrups, teas, and diagnostic tools. The affected products are usually sold online or through social media.

Find the full safety alert on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning to 14 U.S. companies that are illegally selling more than 65 products purported to prevent, diagnose, treat, or cure cancer, according to an FDA safety alert.

Product types include pills, topical creams, ointments, oils, drops, syrups, teas, and diagnostic tools. The affected products are usually sold online or through social media.

Find the full safety alert on the FDA website.

MDS genetic analysis identifies allogeneic HSCT candidates

NEW YORK – Genetic mutation analysis of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) may have a useful role in routine practice based on recent reports that showed clear links between certain gene mutations and the outcomes of patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

Two reports published in 2017 helped strengthen the case for routine mutation analysis in distinguishing patients with MDS or myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDN) who are very likely to have just a brief response to allogeneic HSCT from similar patients who seem likely to have several years of overall survival following transplantation.

Allogeneic HSCT is the only potentially curative procedure for patients with MDS or MDN. Although an increasing number of these patients undergo transplantation, clinicians need to choose the patients they select for the treatment carefully. “Molecular testing is playing an increasing role in selecting the best candidates,” Dr. Zeidan said.

The largest reported genetic study of allogeneic HSCT in MDS patients involved 1,514 patients entered into a U.S.-based dataset during 2005-2015. Testing identified at least one mutation in 1,196 (79%) of these patients.

Analysis of data from these patients found a disparate pattern of posttransplant survival that appeared to link with gene mutations and other risk factors. The highest risk patients were those with a mutation in their TP53 gene, found in 289 patients (19% of the 1,514 tested) who had a median overall survival (OS) of 0.7 years and a 3-year OS of 20% (New Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 9;376[6]:536-47).

Among patients without a TP53 mutation, OS depended on age, with the best survival seen among patients less than 40 years old. Patients in this subgroup who also had no other high-risk features – no therapy-related MDS, a platelet level of at least 30 x 109 at the time of transplantation, and bone marrow blasts less than 15% at diagnosis – had the best OS, 82% at 3-years of follow-up. The studied cohort included 116 patients (8%) who fell into this low-risk, best-outcome category, the optimal population for receiving an allogeneic HSCT, Dr. Zeidan said. Another 98 patients (6%) who had at least one of these high risk feature had a median OS of 2.6 years and a 3-year OS of 49%.

Additional gene mutations further subdivided the older patients in the study, those at least 40 years old, into various risk subgroups. Older patients with a mutation in a ras-pathway gene had a 0.9 year median OS and a 3-year OS of 30%. This subgroup included 129 patients (9%). Among older patients with no mutation in the ras-pathway gene, mutations in the JAK2 gene also linked with worse survival, a median OS of 0.5 years and a 3-year OS of 28% of a subgroup with 28 patients (2%). The largest subgroup in the study was older patients with no mutations in the TP53, JAK2, or ras-pathway genes, a subgroup with 854 patients (56%), who had a median OS of 2.3 years and a 3-year OS of 46%.

The second recent report was a Japanese study of 797 MDS patients who underwent genetic testing and received an allogeneic HSCT through the Japan Marrow Donor Program. The investigators found identifiable mutations in 617 patients (77%) and documented that patients with a TP53 or ras-pathway mutation had a “dismal prognosis” when associated with a complex karyotype and myelodysplastic or myeloproliferative neoplasms. However, among patients with a mutated TP53 gene or complex karyotype alone, long-term survival following transplantation appeared possible (Blood. 2017. doi: org/10.1182/blood-2016-12-754796.

Two smaller, earlier studies (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Sept 1;32[25]:2691-8; J Clin Oncol. 2016 Oct 20;34[30]:2627-37) also implicated mutations in the TET2, DNMT3A, ASXL1, and RUNX1 genes as identifying MDS patients with worse OS following allogeneic HSCT, Dr. Zeidan noted, but the combination of a TP53 gene mutation and a complex karyotype appears to confer the worst prognosis of all. Patients with mutations in more than one of these genes fared much worse than those with single mutations.

Dr. Zeidan had no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NEW YORK – Genetic mutation analysis of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) may have a useful role in routine practice based on recent reports that showed clear links between certain gene mutations and the outcomes of patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

Two reports published in 2017 helped strengthen the case for routine mutation analysis in distinguishing patients with MDS or myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDN) who are very likely to have just a brief response to allogeneic HSCT from similar patients who seem likely to have several years of overall survival following transplantation.

Allogeneic HSCT is the only potentially curative procedure for patients with MDS or MDN. Although an increasing number of these patients undergo transplantation, clinicians need to choose the patients they select for the treatment carefully. “Molecular testing is playing an increasing role in selecting the best candidates,” Dr. Zeidan said.

The largest reported genetic study of allogeneic HSCT in MDS patients involved 1,514 patients entered into a U.S.-based dataset during 2005-2015. Testing identified at least one mutation in 1,196 (79%) of these patients.

Analysis of data from these patients found a disparate pattern of posttransplant survival that appeared to link with gene mutations and other risk factors. The highest risk patients were those with a mutation in their TP53 gene, found in 289 patients (19% of the 1,514 tested) who had a median overall survival (OS) of 0.7 years and a 3-year OS of 20% (New Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 9;376[6]:536-47).

Among patients without a TP53 mutation, OS depended on age, with the best survival seen among patients less than 40 years old. Patients in this subgroup who also had no other high-risk features – no therapy-related MDS, a platelet level of at least 30 x 109 at the time of transplantation, and bone marrow blasts less than 15% at diagnosis – had the best OS, 82% at 3-years of follow-up. The studied cohort included 116 patients (8%) who fell into this low-risk, best-outcome category, the optimal population for receiving an allogeneic HSCT, Dr. Zeidan said. Another 98 patients (6%) who had at least one of these high risk feature had a median OS of 2.6 years and a 3-year OS of 49%.

Additional gene mutations further subdivided the older patients in the study, those at least 40 years old, into various risk subgroups. Older patients with a mutation in a ras-pathway gene had a 0.9 year median OS and a 3-year OS of 30%. This subgroup included 129 patients (9%). Among older patients with no mutation in the ras-pathway gene, mutations in the JAK2 gene also linked with worse survival, a median OS of 0.5 years and a 3-year OS of 28% of a subgroup with 28 patients (2%). The largest subgroup in the study was older patients with no mutations in the TP53, JAK2, or ras-pathway genes, a subgroup with 854 patients (56%), who had a median OS of 2.3 years and a 3-year OS of 46%.

The second recent report was a Japanese study of 797 MDS patients who underwent genetic testing and received an allogeneic HSCT through the Japan Marrow Donor Program. The investigators found identifiable mutations in 617 patients (77%) and documented that patients with a TP53 or ras-pathway mutation had a “dismal prognosis” when associated with a complex karyotype and myelodysplastic or myeloproliferative neoplasms. However, among patients with a mutated TP53 gene or complex karyotype alone, long-term survival following transplantation appeared possible (Blood. 2017. doi: org/10.1182/blood-2016-12-754796.

Two smaller, earlier studies (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Sept 1;32[25]:2691-8; J Clin Oncol. 2016 Oct 20;34[30]:2627-37) also implicated mutations in the TET2, DNMT3A, ASXL1, and RUNX1 genes as identifying MDS patients with worse OS following allogeneic HSCT, Dr. Zeidan noted, but the combination of a TP53 gene mutation and a complex karyotype appears to confer the worst prognosis of all. Patients with mutations in more than one of these genes fared much worse than those with single mutations.

Dr. Zeidan had no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NEW YORK – Genetic mutation analysis of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) may have a useful role in routine practice based on recent reports that showed clear links between certain gene mutations and the outcomes of patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

Two reports published in 2017 helped strengthen the case for routine mutation analysis in distinguishing patients with MDS or myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDN) who are very likely to have just a brief response to allogeneic HSCT from similar patients who seem likely to have several years of overall survival following transplantation.

Allogeneic HSCT is the only potentially curative procedure for patients with MDS or MDN. Although an increasing number of these patients undergo transplantation, clinicians need to choose the patients they select for the treatment carefully. “Molecular testing is playing an increasing role in selecting the best candidates,” Dr. Zeidan said.

The largest reported genetic study of allogeneic HSCT in MDS patients involved 1,514 patients entered into a U.S.-based dataset during 2005-2015. Testing identified at least one mutation in 1,196 (79%) of these patients.

Analysis of data from these patients found a disparate pattern of posttransplant survival that appeared to link with gene mutations and other risk factors. The highest risk patients were those with a mutation in their TP53 gene, found in 289 patients (19% of the 1,514 tested) who had a median overall survival (OS) of 0.7 years and a 3-year OS of 20% (New Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 9;376[6]:536-47).

Among patients without a TP53 mutation, OS depended on age, with the best survival seen among patients less than 40 years old. Patients in this subgroup who also had no other high-risk features – no therapy-related MDS, a platelet level of at least 30 x 109 at the time of transplantation, and bone marrow blasts less than 15% at diagnosis – had the best OS, 82% at 3-years of follow-up. The studied cohort included 116 patients (8%) who fell into this low-risk, best-outcome category, the optimal population for receiving an allogeneic HSCT, Dr. Zeidan said. Another 98 patients (6%) who had at least one of these high risk feature had a median OS of 2.6 years and a 3-year OS of 49%.

Additional gene mutations further subdivided the older patients in the study, those at least 40 years old, into various risk subgroups. Older patients with a mutation in a ras-pathway gene had a 0.9 year median OS and a 3-year OS of 30%. This subgroup included 129 patients (9%). Among older patients with no mutation in the ras-pathway gene, mutations in the JAK2 gene also linked with worse survival, a median OS of 0.5 years and a 3-year OS of 28% of a subgroup with 28 patients (2%). The largest subgroup in the study was older patients with no mutations in the TP53, JAK2, or ras-pathway genes, a subgroup with 854 patients (56%), who had a median OS of 2.3 years and a 3-year OS of 46%.

The second recent report was a Japanese study of 797 MDS patients who underwent genetic testing and received an allogeneic HSCT through the Japan Marrow Donor Program. The investigators found identifiable mutations in 617 patients (77%) and documented that patients with a TP53 or ras-pathway mutation had a “dismal prognosis” when associated with a complex karyotype and myelodysplastic or myeloproliferative neoplasms. However, among patients with a mutated TP53 gene or complex karyotype alone, long-term survival following transplantation appeared possible (Blood. 2017. doi: org/10.1182/blood-2016-12-754796.

Two smaller, earlier studies (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Sept 1;32[25]:2691-8; J Clin Oncol. 2016 Oct 20;34[30]:2627-37) also implicated mutations in the TET2, DNMT3A, ASXL1, and RUNX1 genes as identifying MDS patients with worse OS following allogeneic HSCT, Dr. Zeidan noted, but the combination of a TP53 gene mutation and a complex karyotype appears to confer the worst prognosis of all. Patients with mutations in more than one of these genes fared much worse than those with single mutations.

Dr. Zeidan had no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

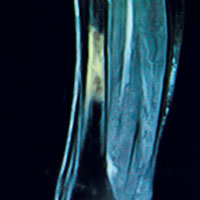

Pes planus: To treat or not to treat

Pes planus, or flat feet, is a common concern addressed during well-child visits. Many parents express concern more because of the appearance of the feet than actual symptomatology. But what is within the realm of normal and what is beyond?

Ninety percent of clinic visits for foot problems are for flat feet.1 Historically, the treatment of flat feet was wearing orthopedic shoes that were unappealing, so parents fear that is the fate of their child. Although the exact incidence rate of flat feet has not been determined, it clearly is quite common. Other contributing factors are joint hypermobility, obesity, and age. All children under the age of 2 years have flat feet because of the fat pad that is present. By the age of 10 years, this fat pad regresses and the normal arch is formed.

Given that the arch does not fully form until the end of the first decade of life, neither diagnosis nor treatment should be given until after that time. Evaluating for flat feet in the clinic is usually limited to inspection in weight bearing and non-weight bearing. There are more formal procedures using foot prints and x-rays, but practically speaking those are not necessary. It is key to examine the patient while he or she is standing, to see if the arch is present and to gauge the orientation of the talus bone. When the patient is supine, again note if the arch is present and check the degree of dorsiflexion and plantarflexion.

Determine whether the talus bone is straight or in a valgus position, and whether there is a shortened Achilles tendon. This is crucial in predicting whether symptoms will emerge if they haven’t already. Patients with rigid flat feet or flexible flat feet with shortened Achilles tendon usually begin to complain of discomfort with activity in the second or third decade of life. Those symptoms may be limited to pain in the foot near the head of the talus, or can be complaints of knee, hip, or back pain.1

For the asymptomatic patient, no intervention is needed. Although many clinicians recommend orthotics, studies have shown that after years of wearing orthotics, the feet remain flat. For symptomatic patients with flexible flat feet, there is increased intrinsic muscle activity, which can result in soreness and achiness of the feet. Orthotics can offer some relief, but for patients with shortened Achilles tendons, it potentially can cause more discomfort.2 Both OTC and hard custom orthotics have been shown to relieve pain without significant increase in the height of the arch. There is little information to support using one over the other.2

Heel cord stretching is another reasonable intervention to improve any discomfort. It is important to note that the knee must be extended and the subtalar joint must be in the neutral position for the stretch to be effective.

Surgery is reserved for flexible and rigid flat feet that are symptomatic despite conservative treatment. Bone reconstruction and tendon lengthening have shown reduction in symptoms.

In summary, the vast majority of patients with flat feet do not need any intervention. Proper categorization is important to determine if intervention will be needed. The use of orthotics should be reserved for symptomatic patients, but will not alter the height of the arch. Surgery is indicated for those patients with significant symptoms that have not improved with conservative measures. It has been found to be effective if all components of the deformity have been addressed.

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Iran J Pediatr. 2013 Jun;23(3):247-60.

2. J Child Orthop. 2010;4(2):107-21.

Pes planus, or flat feet, is a common concern addressed during well-child visits. Many parents express concern more because of the appearance of the feet than actual symptomatology. But what is within the realm of normal and what is beyond?

Ninety percent of clinic visits for foot problems are for flat feet.1 Historically, the treatment of flat feet was wearing orthopedic shoes that were unappealing, so parents fear that is the fate of their child. Although the exact incidence rate of flat feet has not been determined, it clearly is quite common. Other contributing factors are joint hypermobility, obesity, and age. All children under the age of 2 years have flat feet because of the fat pad that is present. By the age of 10 years, this fat pad regresses and the normal arch is formed.

Given that the arch does not fully form until the end of the first decade of life, neither diagnosis nor treatment should be given until after that time. Evaluating for flat feet in the clinic is usually limited to inspection in weight bearing and non-weight bearing. There are more formal procedures using foot prints and x-rays, but practically speaking those are not necessary. It is key to examine the patient while he or she is standing, to see if the arch is present and to gauge the orientation of the talus bone. When the patient is supine, again note if the arch is present and check the degree of dorsiflexion and plantarflexion.

Determine whether the talus bone is straight or in a valgus position, and whether there is a shortened Achilles tendon. This is crucial in predicting whether symptoms will emerge if they haven’t already. Patients with rigid flat feet or flexible flat feet with shortened Achilles tendon usually begin to complain of discomfort with activity in the second or third decade of life. Those symptoms may be limited to pain in the foot near the head of the talus, or can be complaints of knee, hip, or back pain.1

For the asymptomatic patient, no intervention is needed. Although many clinicians recommend orthotics, studies have shown that after years of wearing orthotics, the feet remain flat. For symptomatic patients with flexible flat feet, there is increased intrinsic muscle activity, which can result in soreness and achiness of the feet. Orthotics can offer some relief, but for patients with shortened Achilles tendons, it potentially can cause more discomfort.2 Both OTC and hard custom orthotics have been shown to relieve pain without significant increase in the height of the arch. There is little information to support using one over the other.2

Heel cord stretching is another reasonable intervention to improve any discomfort. It is important to note that the knee must be extended and the subtalar joint must be in the neutral position for the stretch to be effective.

Surgery is reserved for flexible and rigid flat feet that are symptomatic despite conservative treatment. Bone reconstruction and tendon lengthening have shown reduction in symptoms.

In summary, the vast majority of patients with flat feet do not need any intervention. Proper categorization is important to determine if intervention will be needed. The use of orthotics should be reserved for symptomatic patients, but will not alter the height of the arch. Surgery is indicated for those patients with significant symptoms that have not improved with conservative measures. It has been found to be effective if all components of the deformity have been addressed.

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Iran J Pediatr. 2013 Jun;23(3):247-60.

2. J Child Orthop. 2010;4(2):107-21.

Pes planus, or flat feet, is a common concern addressed during well-child visits. Many parents express concern more because of the appearance of the feet than actual symptomatology. But what is within the realm of normal and what is beyond?

Ninety percent of clinic visits for foot problems are for flat feet.1 Historically, the treatment of flat feet was wearing orthopedic shoes that were unappealing, so parents fear that is the fate of their child. Although the exact incidence rate of flat feet has not been determined, it clearly is quite common. Other contributing factors are joint hypermobility, obesity, and age. All children under the age of 2 years have flat feet because of the fat pad that is present. By the age of 10 years, this fat pad regresses and the normal arch is formed.

Given that the arch does not fully form until the end of the first decade of life, neither diagnosis nor treatment should be given until after that time. Evaluating for flat feet in the clinic is usually limited to inspection in weight bearing and non-weight bearing. There are more formal procedures using foot prints and x-rays, but practically speaking those are not necessary. It is key to examine the patient while he or she is standing, to see if the arch is present and to gauge the orientation of the talus bone. When the patient is supine, again note if the arch is present and check the degree of dorsiflexion and plantarflexion.

Determine whether the talus bone is straight or in a valgus position, and whether there is a shortened Achilles tendon. This is crucial in predicting whether symptoms will emerge if they haven’t already. Patients with rigid flat feet or flexible flat feet with shortened Achilles tendon usually begin to complain of discomfort with activity in the second or third decade of life. Those symptoms may be limited to pain in the foot near the head of the talus, or can be complaints of knee, hip, or back pain.1

For the asymptomatic patient, no intervention is needed. Although many clinicians recommend orthotics, studies have shown that after years of wearing orthotics, the feet remain flat. For symptomatic patients with flexible flat feet, there is increased intrinsic muscle activity, which can result in soreness and achiness of the feet. Orthotics can offer some relief, but for patients with shortened Achilles tendons, it potentially can cause more discomfort.2 Both OTC and hard custom orthotics have been shown to relieve pain without significant increase in the height of the arch. There is little information to support using one over the other.2

Heel cord stretching is another reasonable intervention to improve any discomfort. It is important to note that the knee must be extended and the subtalar joint must be in the neutral position for the stretch to be effective.

Surgery is reserved for flexible and rigid flat feet that are symptomatic despite conservative treatment. Bone reconstruction and tendon lengthening have shown reduction in symptoms.

In summary, the vast majority of patients with flat feet do not need any intervention. Proper categorization is important to determine if intervention will be needed. The use of orthotics should be reserved for symptomatic patients, but will not alter the height of the arch. Surgery is indicated for those patients with significant symptoms that have not improved with conservative measures. It has been found to be effective if all components of the deformity have been addressed.

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Iran J Pediatr. 2013 Jun;23(3):247-60.

2. J Child Orthop. 2010;4(2):107-21.

Primary Hyperparathyroidism: A Case-based Review

CE/CME No: CR-1705

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Differentiate primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) from other causes of hypercalcemia and types of hyerparathyroidism.

• Understand the calcium-parathyroid hormone feedback loop.

• Identify appropriate imaging studies and common laboratory findings in the patient with PHPT.

• Describe the common systemic manifestations of PHPT.

• Discuss medical versus surgical management of the patient with PHPT.

FACULTY

Barbara Austin is a Family Nurse Practitioner at Baptist Primary Care, Jacksonville, Florida, and is pursuing a Doctorate of Nursing Practice (DNP) at Jacksonville University.

The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of May 2017.

Article begins on next page >>

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is most often detected as hypercalcemia in an asymptomatic patient during routine blood work. Knowing the appropriate work-up of hypercalcemia is essential, since untreated PHPT can have significant complications affecting multiple organ systems—most notably, renal and musculoskeletal. Parathyroidectomy is curative in up to 95% of cases, but prevention of long-term complications relies on prompt recognition and appropriate follow-up.

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is a common endocrine disorder, with a prevalence of approximately 1 to 3 cases per 1,000 persons.1 PHPT results from inappropriate overproduction of parathyroid hormone (PTH), the primary regulator of calcium homeostasis, and is characterized by hypercalcemia in the setting of an elevated or high-normal PTH level. In most cases of PHPT, unregulated PTH production is caused by a single parathyroid adenoma.

PHPT is the most common cause of hypercalcemia in outpatients and is typically diagnosed following incidental discovery during routine blood work in an asymptomatic patient.1,2 It is two to three times more common in women than in men, and incidence increases with age; as such, postmenopausal women are most commonly affected.1,3 PHPT often has an insidious course, and recognition of its clinical manifestations followed by appropriate diagnostic work-up and management are necessary to prevent sequelae.3

PATIENT PRESENTATION

A 68-year-old Caucasian woman presented to her family practice office for a third visit with continued complaints of nontraumatic right lower leg pain. She had previously been diagnosed with tendonitis, which was treated conservatively. The pain failed to improve, and an x-ray was ordered. The x-ray revealed no acute findings but did show osteopenia, prompting an order for a bone mineral density (BMD) test. The BMD test demonstrated osteoporosis, which warranted further investigation. She was prescribed alendronate but refused it, against medical advice, due to concern over potential adverse effects.

Her medical history included hyperlipidemia and hypertension under fair control with lisinopril. She took a low-dose aspirin and flaxseed supplement daily. She also had a history of radiation to the neck, having undergone tonsillar irradiation as a child (a common practice from the 1930s through the 1950s).3 Surgical history included a total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, appendectomy, and tonsillectomy. There was no personal or family history of cancer or endocrine disorders, hypercalcemia, or nephrolithiasis. She was up to date on vaccines and preventive health care measures. Allergies included penicillin and sulfa, both resulting in hives. She was a nonsmoker and did not drink alcohol or engage in illicit drug use.

Review of systems revealed right lower anterior leg pain for four months, characterized as aching, deep, sharp, and throbbing with radiation to the ankle. The pain was worse with activity and prolonged standing; ibuprofen and application of ice provided partial relief. She had experienced some mood changes, including irritability. Physical exam was normal except for dominant right-sided thyromegaly, marked bony point tenderness to the right midshin area, and an antalgic gait.

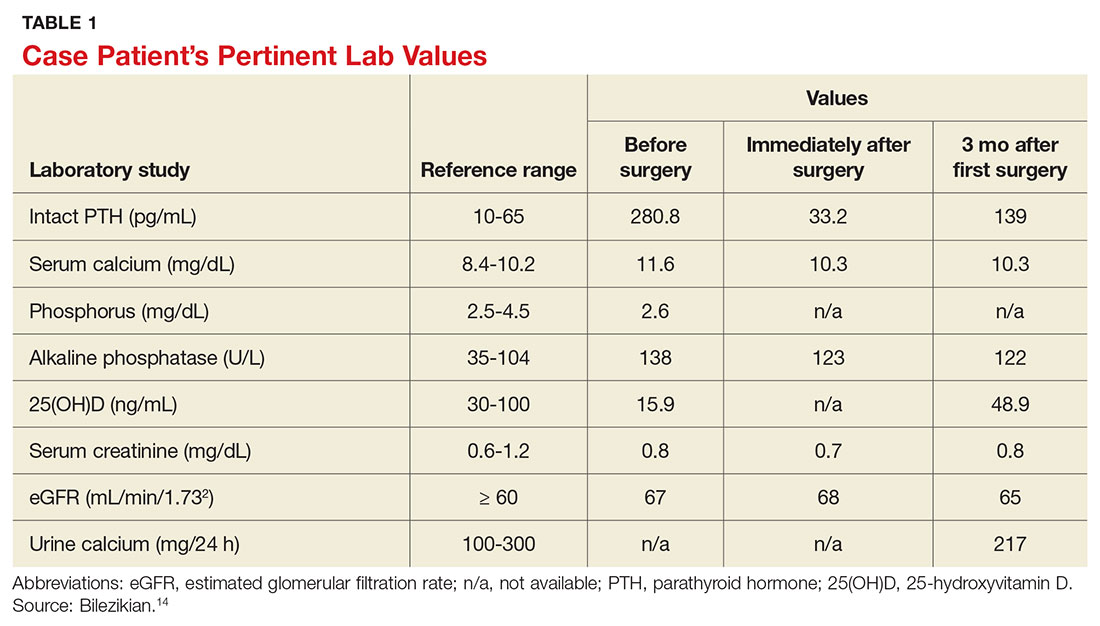

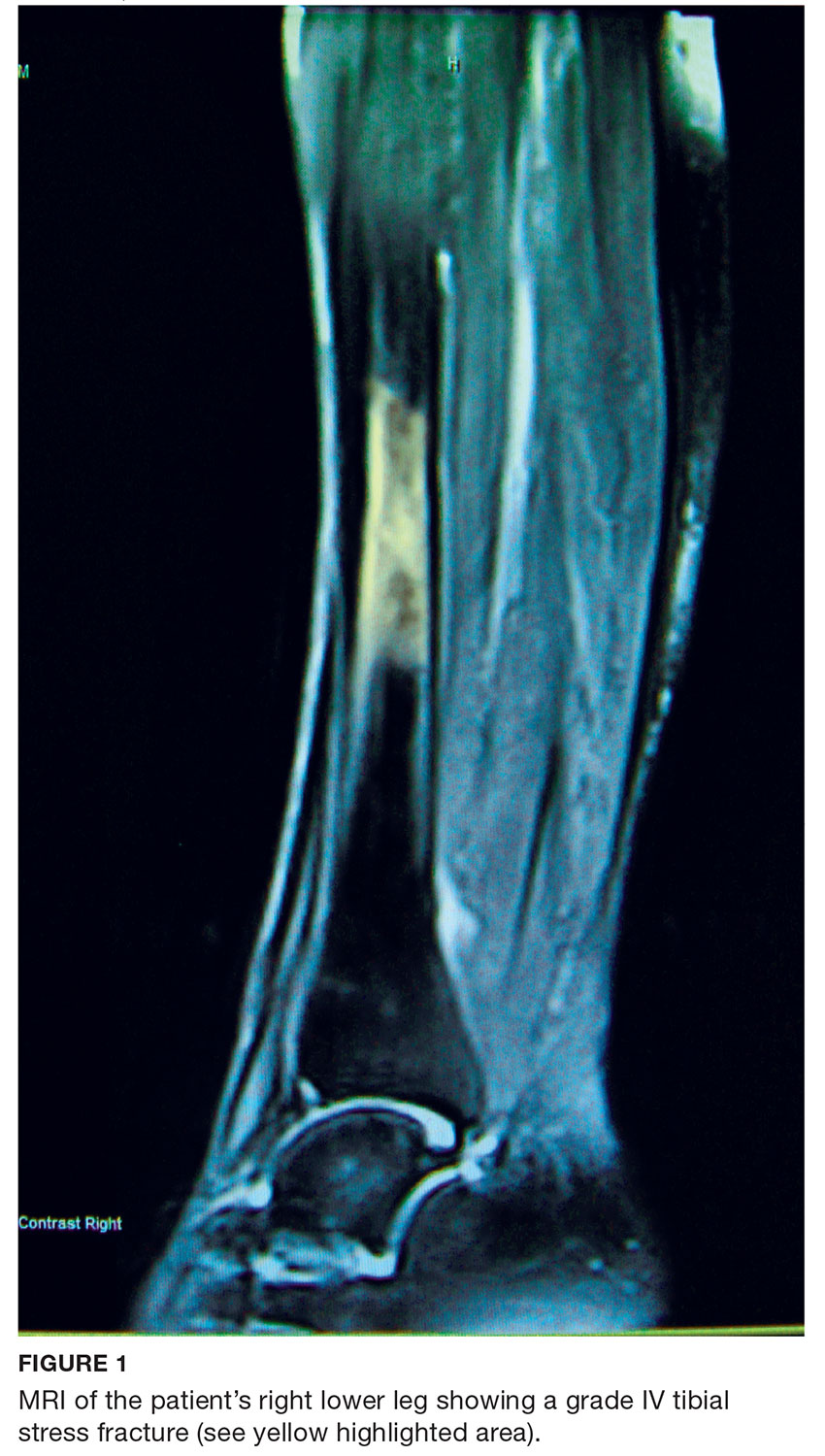

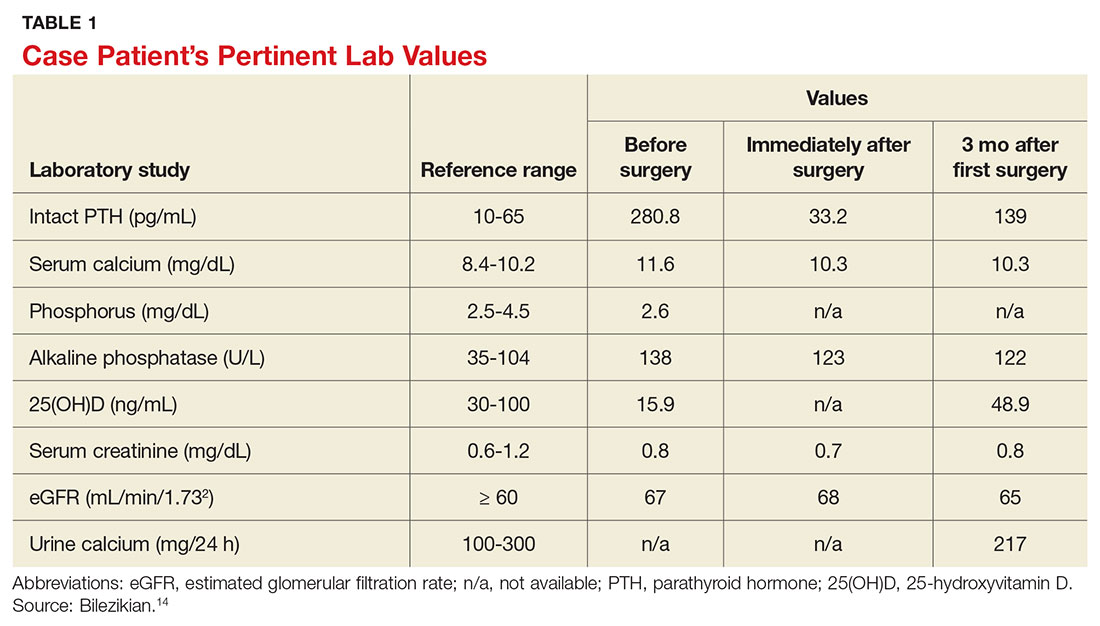

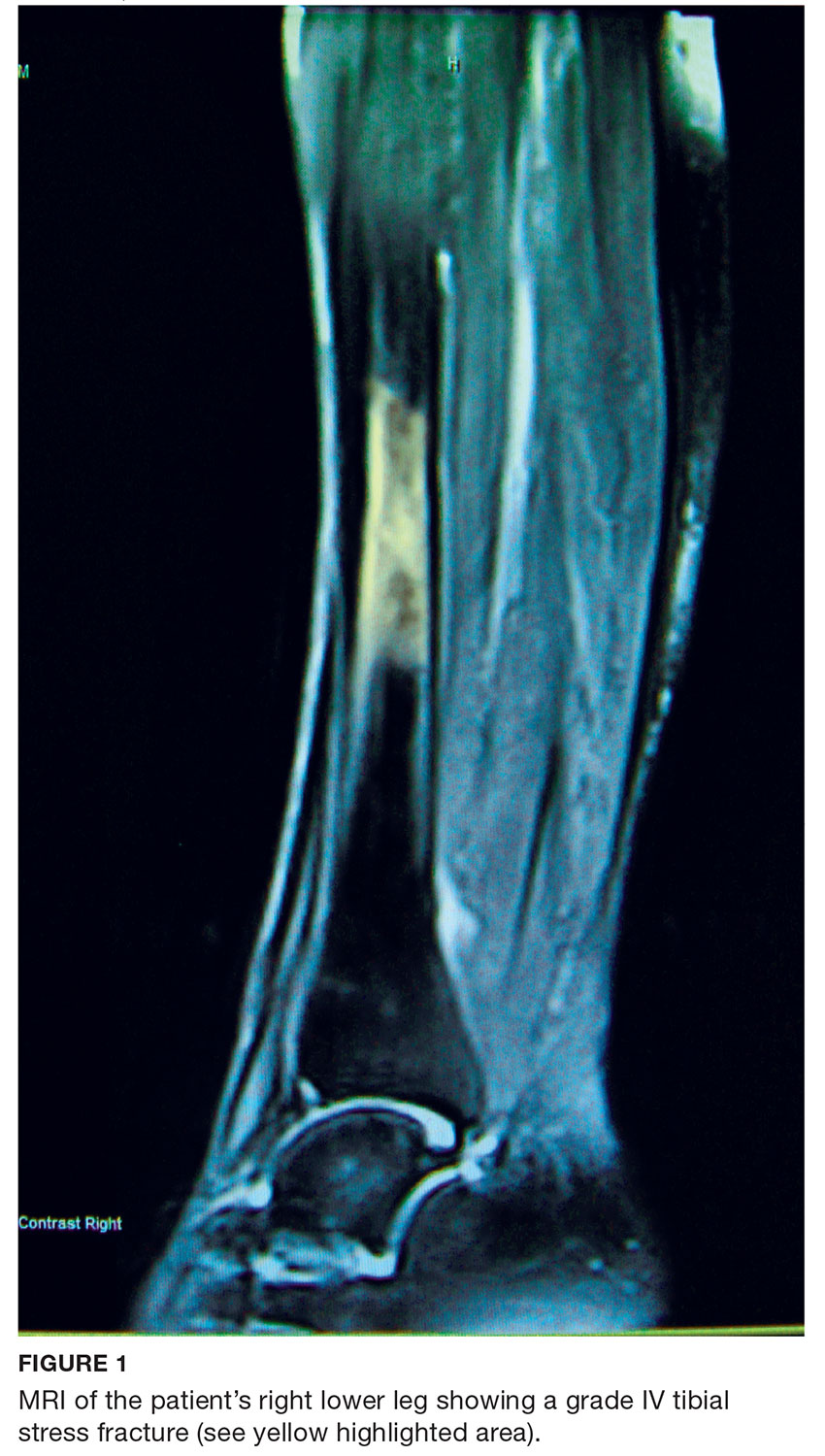

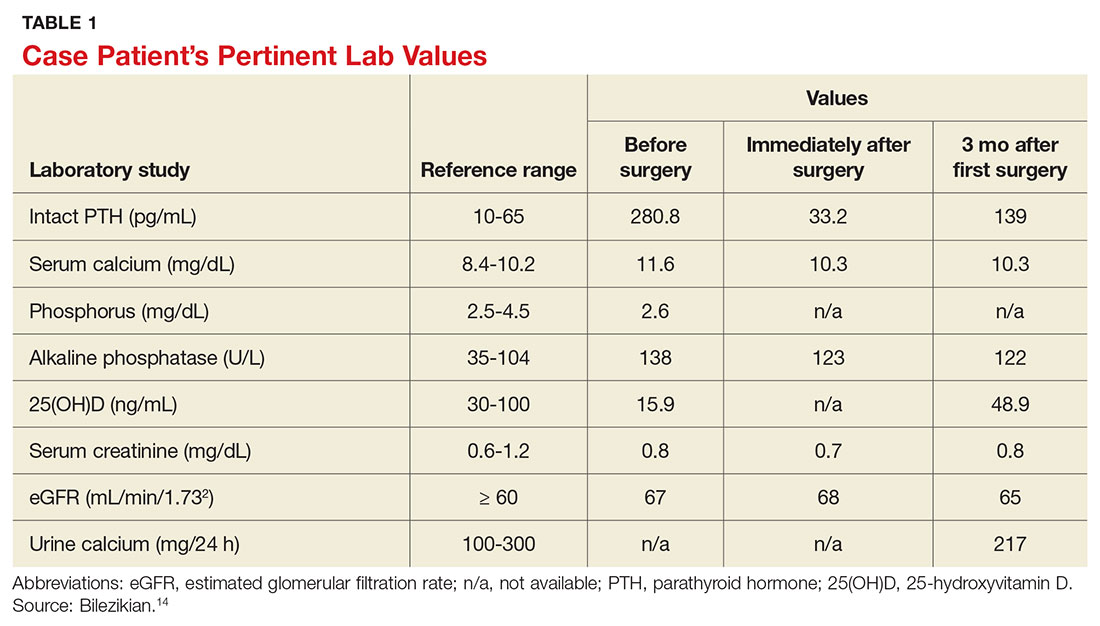

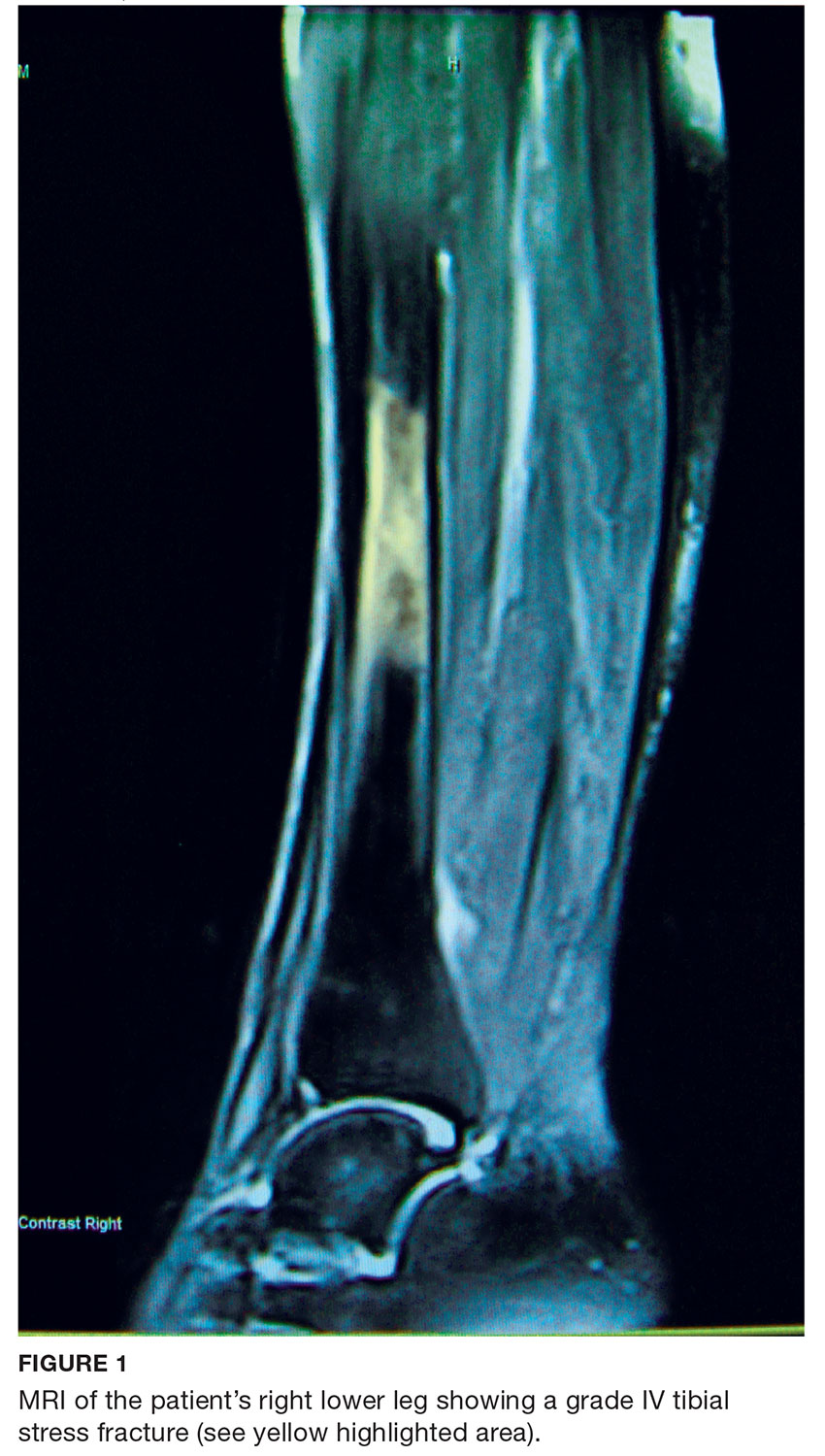

Laboratory work-up demonstrated elevated PTH, alkaline phosphatase, and calcium levels and a low 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] level (see Table 1). MRI of the right lower leg revealed a grade IV stress fracture (see Figure 1). The elevated serum calcium and PTH levels in addition to abnormal bone density findings led to the diagnosis of PHPT. She was referred to endocrinology and orthopedics for management of PHPT and the stress fracture, respectively, and was placed in an orthopedic walking boot for treatment of the midtibial stress fracture.

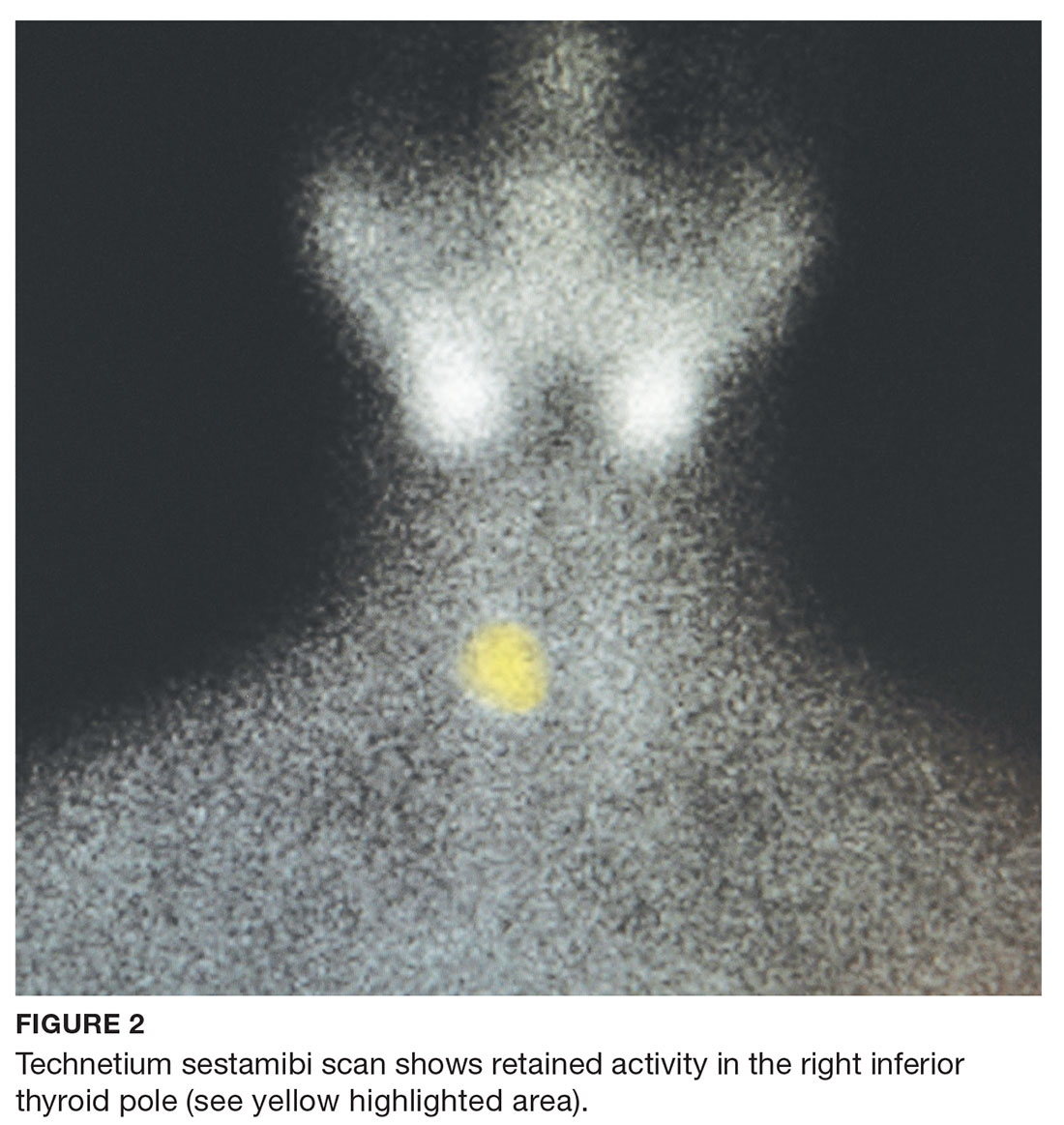

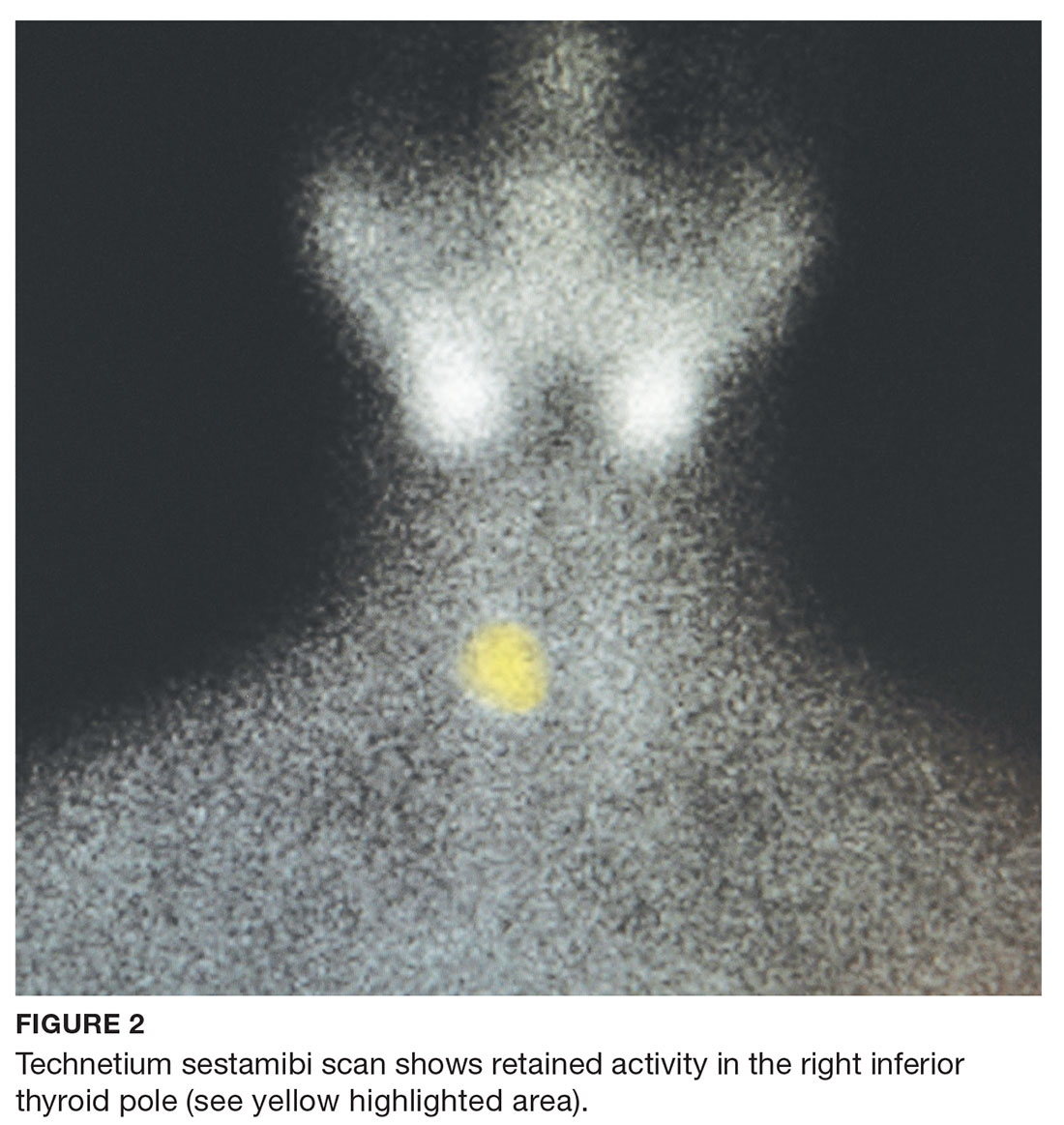

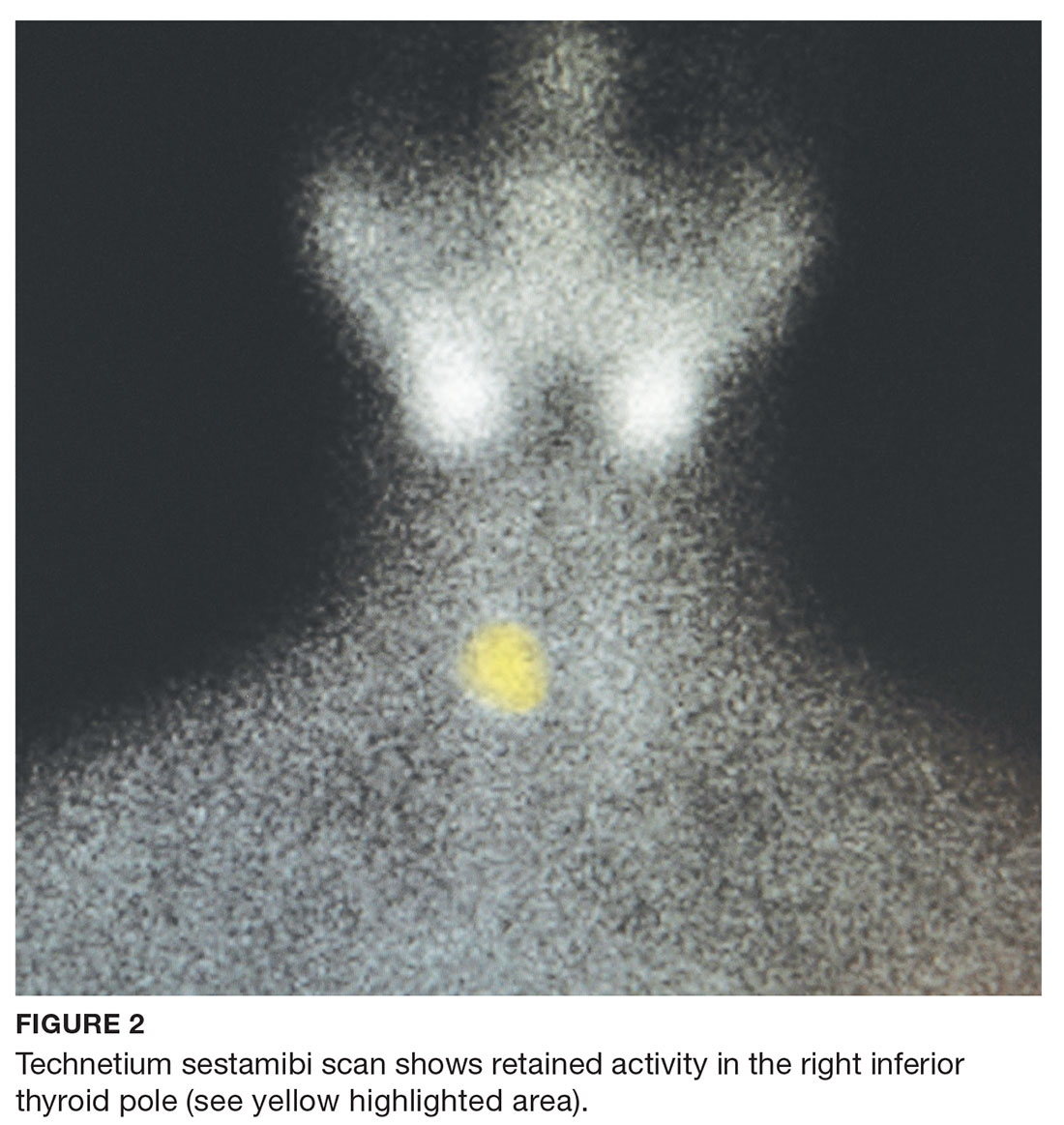

The endocrinologist referred her to an otolaryngologist trained in the surgical management of parathyroid adenomas, who ordered a thyroid ultrasound; this study was inconclusive. Additional imaging, including a Tc-99m sestamibi parathyroid scan and CT with contrast of the soft tissue of the neck, was obtained. The parathyroid scan of the neck and upper chest showed retained activity in the right inferior thyroid pole that was concerning for a parathyroid adenoma (see Figure 2). The CT identified a 1.5-cm parathyroid adenoma off the right inferior pole of the thyroid gland (concordant with the parathyroid scan). A single 300-mg parathyroid adenoma was removed from the right inferior pole of the thyroid. The surgery was deemed successful, with intraoperative normalization of the PTH level.

The patient was managed postoperatively by the endocrinologist and was started on calcium and vitamin D supplements. She was prescribed a bisphosphonate, as she had refused to take alendronate following her abnormal BMD test.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

PHPT and malignancy are the most common causes of hypercalcemia, accounting for 90% of cases.2,4 A less common cause is familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHH), a rare benign disorder that imitates PHPT.1 FHH is ruled out by measurement of 24-hour urine calcium excretion and is characterized by hypocalciuria, defined as a urine calcium level of less than 100 mg/24 h (reference range, 100-300 mg/24 h).2 Low calcium excretion can also be identified by a calcium-creatinine excretion ratio.2 FHH is a benign autosomal dominant condition caused by a heterozygous mutation of the parathyroid glands’ calcium-sensing receptors.2,5,6 Young adults with FHH are asymptomatic, and mild hypercalcemia and a normal or slightly elevated PTH are the only laboratory findings.4

Measuring PTH levels is key in determining the underlying mechanism of hypercalcemia.2,7 If the hypercalcemia is not PTH-mediated, malignancy and granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis must be considered.2,7 PTH is suppressed in malignancy except for rare cases of PTH-producing tumors.4 Bone metastases cause calcium resorption, and sarcoidosis causes an excess of vitamin D, both resulting in hypercalcemia. Lymphomas and sarcoid granulomas express 1α-hydroxylase, an enzyme that increases the conversion of 25(OH)D to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D].2 When malignancy is suspected, it is appropriate to check a 1,25(OH)2D level. Thiazide diuretics, such as hydrochlorothiazide, decrease urinary calcium excretion and may result in mild hypercalcemia.2 Other possibilities in the differential include hypervitaminosis A or D, dehydration, and excess calcium ingestion, but these are less common.6,7

CALCIUM REGULATION

The parathyroid glands stem from four poles on the back of the thyroid gland; there are typically four, but the number can vary from two to 11. Secreted PTH, the primary regulator of calcium homeostasis, maintains calcium levels within a narrow physiologic range.2,8 PTH increases bone resorption, stimulating release of calcium into the blood, and signals the kidneys to increase reabsorption of calcium and excrete phosphorus. It also converts 25(OH)D to 1,25(OH)2 D, the active form of vitamin D that increases gastrointestinal calcium absorption. In a negative feedback loop, PTH secretion is regulated by serum calcium levels, stimulated when levels are low and suppressed when levels are high (see Figure 3).3 Calcium-sensing receptors, located in the chief cells of parathyroid tissue, are essential to calcium homeostasis. These receptors will either increase or decrease PTH release in response to small changes in blood ionized calcium levels. The receptors also play an independent role in the renal tubules by promoting secretion of calcium in the setting of hypercalcemia.5,9 The precise regulation of intracellular and extracellular calcium is necessary for normal functioning of physiologic processes, including bone metabolism, hormone release and regulation, neuromuscular function, and cell signaling.5

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

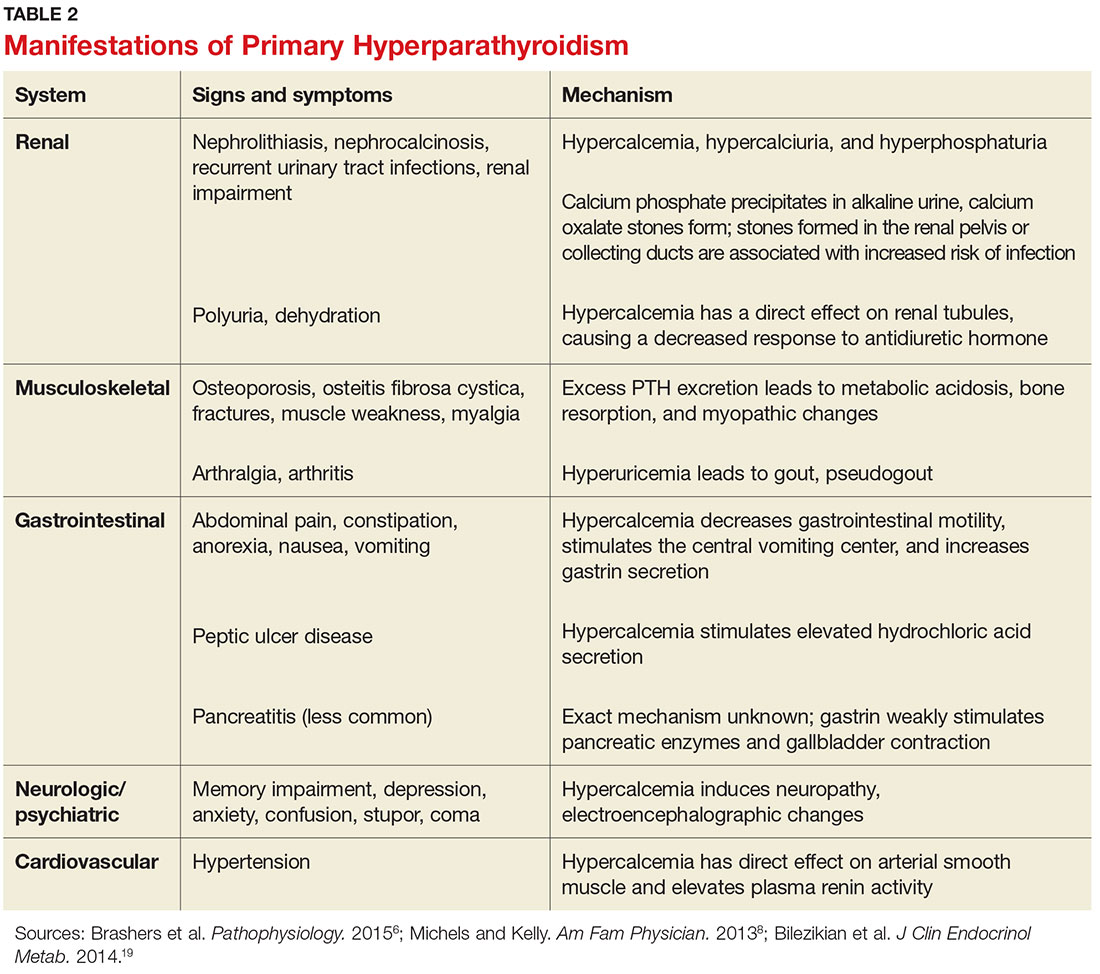

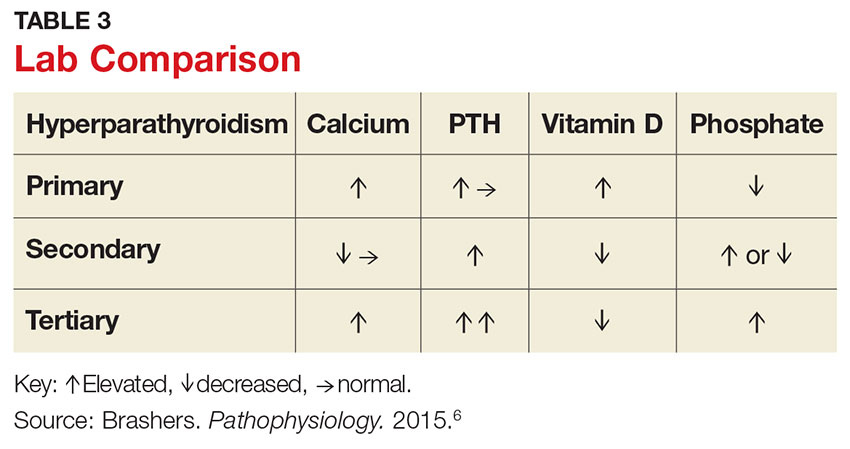

Hyperparathyroidism is defined as excess secretion of PTH and is categorized as primary, secondary, or tertiary based on pathophysiologic mechanisms.

Primary hyperparathyroidism

PHPT is defined as PTH levels that are elevated or inappropriately normal in patients with hypercalcemia and no known history of kidney disease.2,6 This occurs when the normal feedback mechanism fails to inhibit excess hormone secretion by one or more of the parathyroid glands.6 With uninhibited PTH secretion, hypercalcemia will result from increased gastrointestinal absorption and bone resorption.

The most common causes of PHPT are an abnormal proliferation of parathyroid cells (parathyroid adenomas) and parathyroid tissue overgrowth (hyperplasia). PHPT may result from a single parathyroid adenoma (80%-90%), multigland hyperplasia (10%-15%), multiple adenomas (2%-3%), or malignancy (< 1%).6,10 Adenomas can occur sporadically or less commonly as part of an inherited syndrome.1 It is estimated that more than 10% of patients with PHPT have a mutation in one of 11 genes associated with PHPT.11 Approximately 5% of PHPT cases are familial, resulting from adenomas or carcinomas associated with mutations in the tumor suppressor genes MEN1 and CDC73 and the RET proto-oncogene.5 Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome type 1 or 2a is associated with the development of parathyroid adenomas and other endocrine tumors.1,5 Mutations in the CDC73 gene can lead to parathyroid cancer, familial isolated hyperparathyroidism, and familial hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome.5 Parathyroid cancer is rare and is linked to a history of radiation to the head and neck.3 Ectopic parathyroid adenomas represent 3% to 4% of all parathyroid adenomas and are often found in the mediastinum.12PHPT is the third most common endocrine disorder, with a prevalence of 1 case per 1,000 men and 2 to 3 cases per 1,000 women.5 Most women with PHPT are postmenopausal and older than 50.1 The condition can occur in younger adults but is rare in childhood and adolescence, with an incidence of 2 to 5 cases per 100,000.13

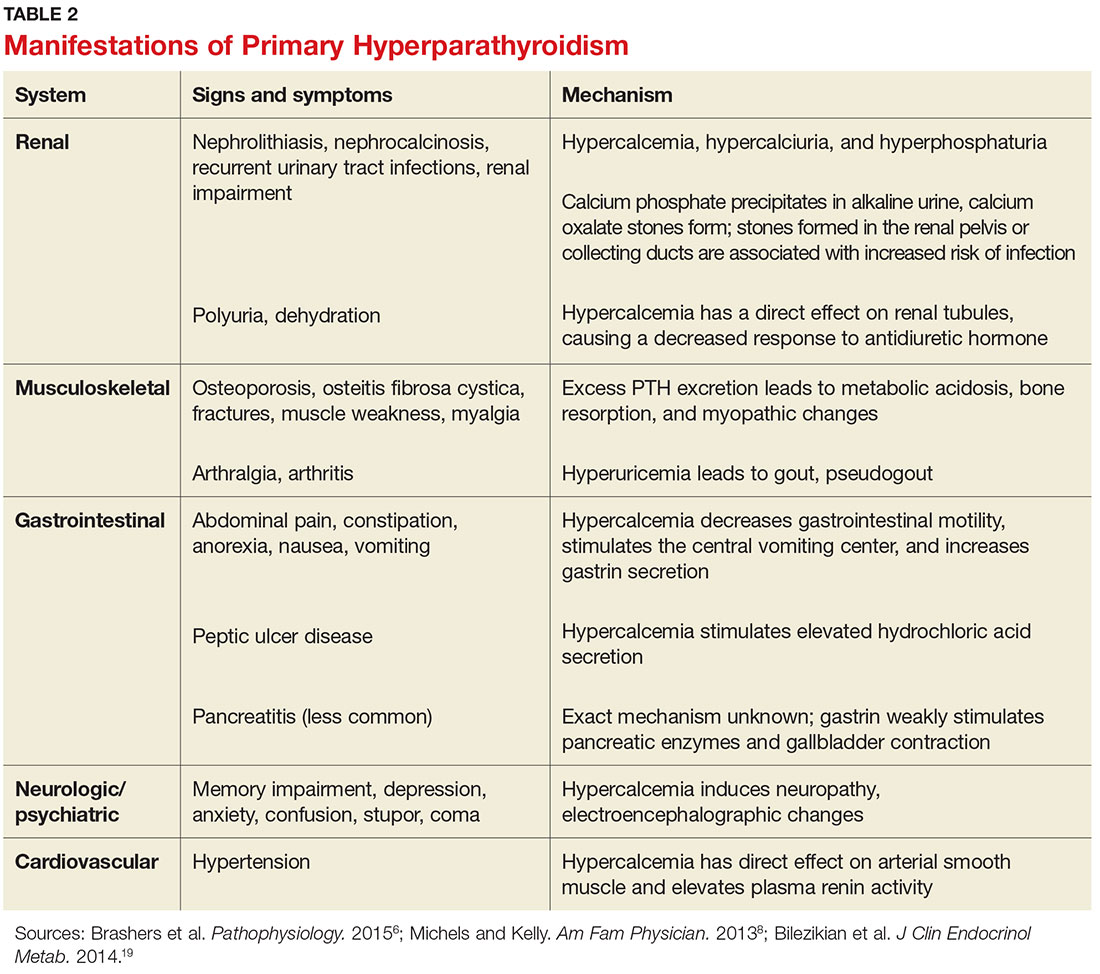

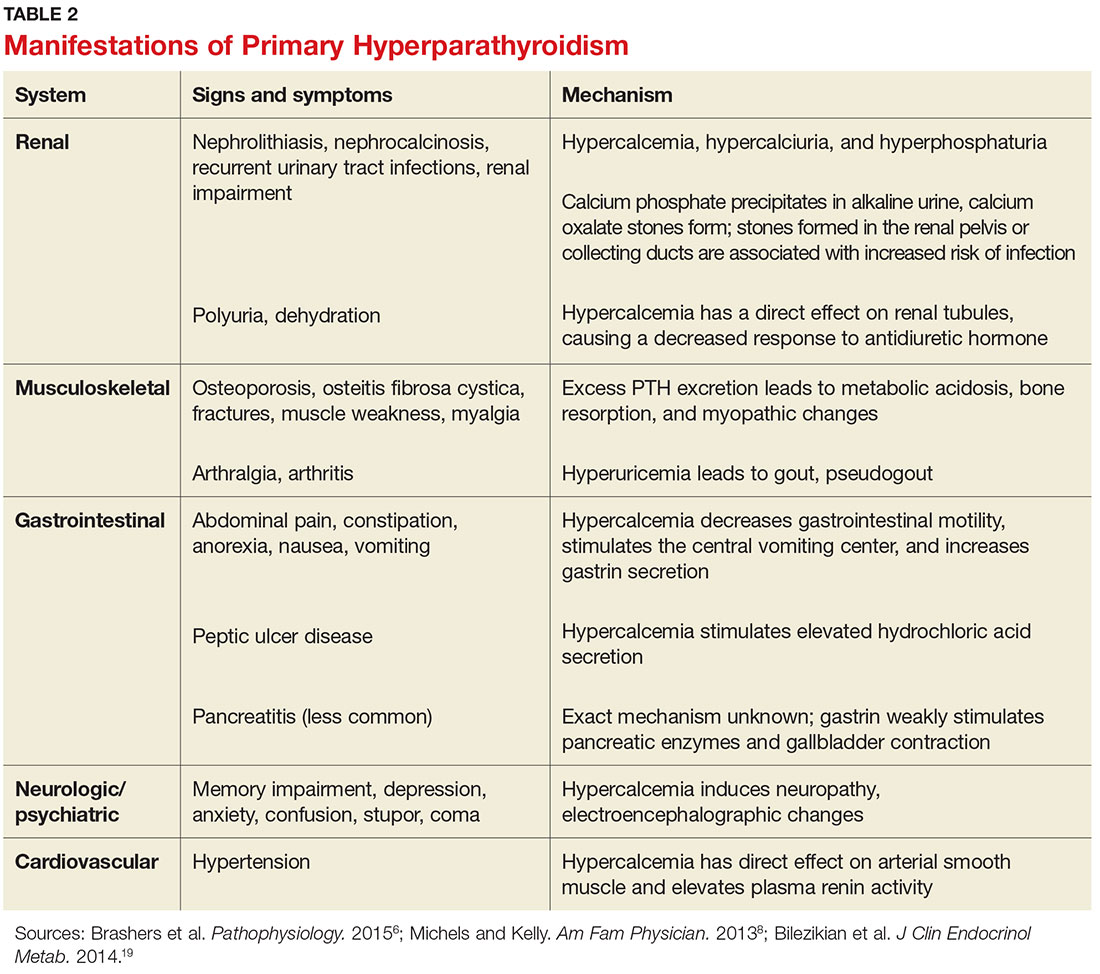

PHPT affects multiple organ systems, but the most commonly involved are the renal and musculoskeletal systems (see Table 2). The hypersecretory state causes excessive bone resorption and increased osteoclastic activity, resulting in osteoporosis and increased risk for pathologic fractures of the hip, wrist, and spine. The most common osteoporotic fractures are vertebral compression fractures.14 Fractures involving the thoracic spine contribute to the development of kyphosis.15

In the kidney, an increased filtered load of calcium leads to hypercalciuria, precipitation of calcium phosphate in the renal pelvis and collecting ducts, metabolic acidosis, alkaline urine, and hyperphosphaturia. The combination of alkaline urine, hyperphosphaturia, and hypercalciuria leads to the formation of kidney stones.6 Nephrolithiasis and alkaline urine predispose patients to recurrent urinary tract infections and subsequent renal impairment.6 In addition, hypercalcemia impairs the renal collecting system and decreases its response to antidiuretic hormone, resulting in polyuria.6

Secondary hyperparathyroidism

In secondary hyperparathyroidism, calcium levels are either normal or low. Normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism is characterized by normal ionized and total calcium levels and elevated PTH levels; it has no known cause.6 Secondary hyperparathyroidism occurs when excess PTH is excreted as a result of a chronic condition that leads to hypocalcemia. Examples of these disease states include vitamin D deficiency, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and intestinal malabsorption. The most common cause of secondary hyperparathyroidism is CKD; glomerular filtration insufficiency results in hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and low 1,25(OH)2D, stimulating the release of PTH. Other causes include deficient intake or decreased absorption of calcium or vitamin D; chronic use of medications such as lithium, phenobarbital, or phenytoin; bariatric surgery; celiac disease; and pancreatic disease.4,6,14 Lithium decreases urinary calcium excretion and reduces the sensitivity of the parathyroid gland to calcium.4

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism, marked by hypercalcemia and excessive PTH secretion, can occur after prolonged secondary hyperparathyroidism. In this disorder, persistent parathyroid stimulation leads to gland hyperplasia, resulting in autonomous production of PTH despite correction of calcium levels.6 It most commonly occurs in patients with chronic secondary hyperparathyroidism with renal failure who receive a kidney transplant.2,6 In some cases, parathyroid hyperplasia may not regress after transplantation and parathyroidectomy may be necessary.

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSTIC WORK-UP

Laboratory tests

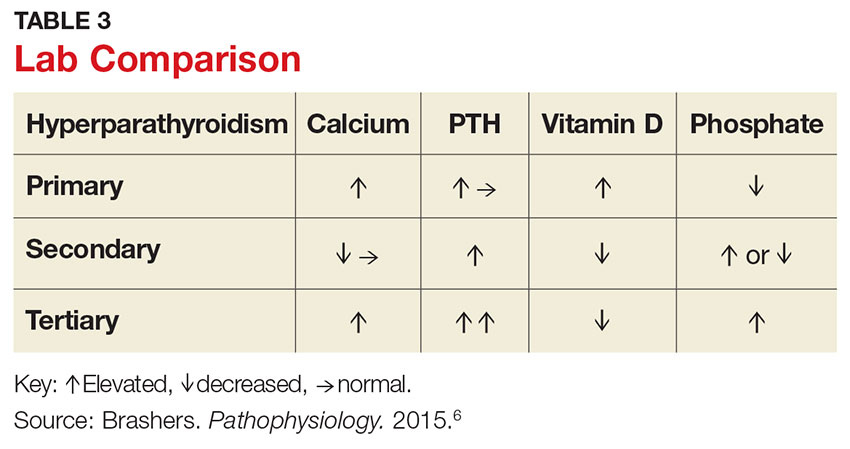

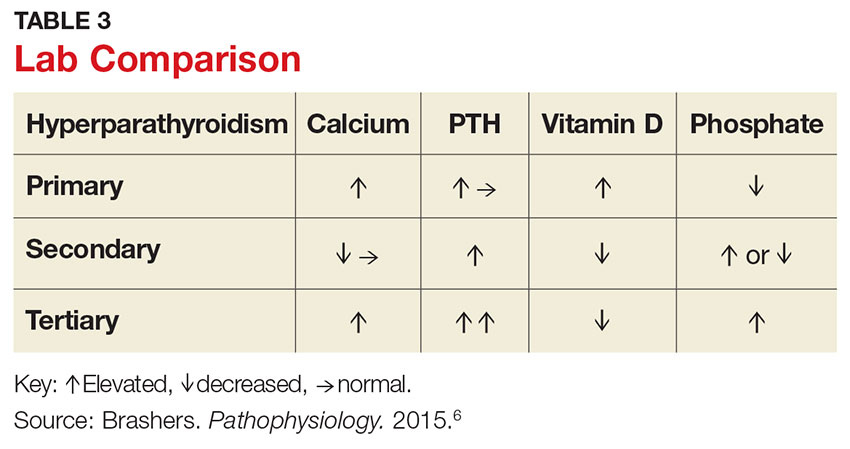

Hypercalcemia is the most common initial finding that leads to the diagnosis of PHPT. Elevated serum calcium and PTH is characteristic of the condition. When evaluating a patient with hypercalcemia, the diagnostic work-up includes tests to differentiate between PTH- and non–PTH-mediated causes of elevated calcium (see Table 3).7 Evaluation should begin with measurement of PTH by second- or third-generation immunoassay along with phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, 25(OH)D, creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and albumin. Additionally, a 24-hour urine collection for calcium, creatinine, and creatinine clearance should be considered in patients with overt nephrolithiasis or nephrocalcinosis. If the urine calcium is > 400 mg/24 h, a renal stone risk profile is indicated because nephrolithiasis is one of the most common complications of PHPT.14 There is a high prevalence of nephrolithiasis in patients with normocalcemic PHPT, even after parathyroidectomy.16 If the 24-hour urine calcium level is low, the diagnosis of FHH is considered. If the urine calcium is high and the intact PTH is elevated or inappropriately normal, the diagnosis of PHPT is considered; urine calcium will be normal in 60% of PHPT cases.4,11

Imaging studies

Imaging is useful for localization of adenomas and abnormal parathyroid tissue to guide surgical planning but is not necessary for diagnosis or medical management. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of imaging modalities enables the clinician to order the most appropriate option. There are three primary imaging modalities used to locate parathyroid adenoma(s) or aberrant parathyroid tissue: ultrasound, nuclear medicine sestamibi parathyroid scans, and CT. Some clinicians start with an ultrasound, but its operator-dependent results can vary widely; in addition, ultrasound often provides poor anatomic definition and has limited value in locating ectopic parathyroid tissue.17

Nuclear medicine parathyroid scan with technetium-99m sestamibi is a sensitive method for localizing hyperfunctioning, enlarged parathyroid glands or tissue in normal anatomic positions or ectopic locations. Uptake is enhanced and prolonged in parathyroid adenomas as well as in aberrant tissue found in the mediastinum or subclavicular areas. Sestamibi parathyroid scan detects up to 89% of single adenomas, but studies of this imaging modality have demonstrated a wide range of sensitivities (44%-95%).5,17 A drawback of nuclear medicine studies is that they provide little anatomic detail.17 Nonetheless, the ability of the parathyroid scan to locate parathyroid glands has contributed to the success of the minimally invasive parathyroidectomy, and it is considered the most successful imaging modality available.5,10 Identifying the precise location of the parathyroid adenoma is essential for a successful surgical outcome; this is best achieved by combining the sestamibi parathyroid scan with CT.12

Emerging imaging modalities are the multidetector CT (MDCT) and 4D-CT techniques. In an evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced MDCT in the detection of parathyroid adenomas and aberrant parathyroid tissue, MDCT demonstrated the ability to differentiate between adenomas and hyperplasia and display important anatomic structures such as nerves and blood vessels.17 The specificity of MDCT for ruling out abnormal parathyroid tissue was 75%, and the sensitivity for detecting a single adenoma was 80%. Overall, MDCT demonstrated an 88% positive predictive value (PPV) in localizing hyperfunctioning parathyroid glands but showed poor sensitivity in detecting multigland disease.17 The PPV is a key value in determining the ability of an imaging study to precisely locate aberrant parathyroid tissue. MDCT provides detailed definition of anatomy, locating ectopic parathyroid glands in the deeper paraesophageal areas and mediastinum while defining relationships between the tissue and its surrounding vasculature, lymph nodes, and thyroid tissue.17 The 4D-CT technique employs three-dimensional technology and accounts for the movement of the patient’s body over time (the “fourth dimension”). It is an accurate method for identifying parathyroid adenomas but exposes the patient to higher radiation doses.18 The sensitivity of 4D-CT in localizing abnormal parathyroid tissue is comparable to that of MDCT.16,18,19

Additional studies used during the management of the patient with PHPT are BMD testing and renal imaging. Secondary causes of bone loss are responsible for up to 30% of osteoporosis cases in postmenopausal women; one of these causes is PHPT.20 Elevated PTH causes increased bone turnover and results in decreased bone mass with subsequent increased fracture risk.9 Bone density should be measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), and the skeletal survey should include the distal one-third of the radius, hip, and lumbar spine. The distal radius is rich in cortical bone and BMD is often lowest at this site in patients with PHPT, making it the most sensitive DEXA marker for early detection of bone loss.19,21 The hip contains an equal mix of cortical and trabecular bone and is the second most sensitive site for detecting bone loss in PHPT. The spine contains a high proportion of trabecular bone and is the least sensitive site.19,21 Renal imaging studies, including x-ray, ultrasound, and, less frequently, CT of the abdomen and pelvis, are used to assess for nephrolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis.19

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

Conservative medical management

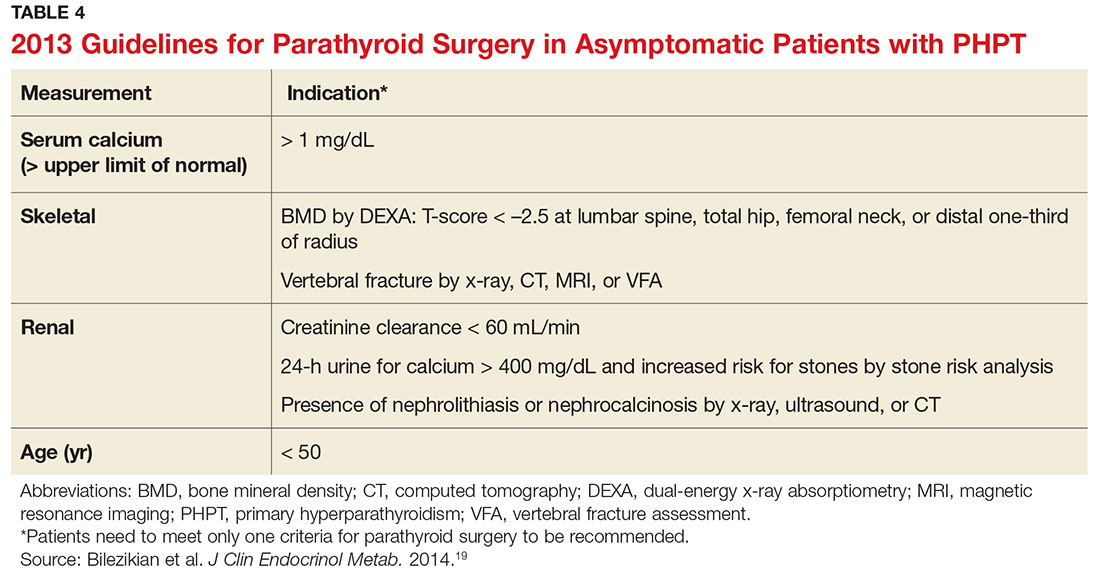

PHPT is a complex disease process, and careful evaluation is required when determining whether medical versus surgical management is appropriate. Clinical presentation ranges from no symptoms to multisystem disease. Conservative medical management, which includes regular monitoring, is an acceptable strategy in an asymptomatic patient with a low fracture risk and no nephrolithiasis.1 Conservative care includes maintaining normal dietary calcium intake and adequate hydration, regular exercise, vitamin D supplementation, annual laboratory studies, BMD testing, and the avoidance of thiazide diuretics and lithium.1 Guidelines, from the Fourth International Workshop on the Management of Asymptomatic Primary Hyperparathyroidism, for monitoring asymptomatic PHPT patients recommend

- Annual measurement of serum calcium

- BMD measurement by DEXA every 1 to 2 years

- Annual assessment of eGFR and serum creatinine

- Renal imaging or a 24-h urine stone profile if nephrolithiasis is suspected.19

Long-term medical management of PHPT is difficult because no agents are available to suppress hypercalcemia or completely block PTH release.12

Maintaining serum 25(OH)D at a level > 20 ng/mL significantly reduces PTH secretion, in comparison to levels < 20 ng/mL, and does not aggravate hypercalcemia.22 The Endocrine Society recommends a minimum serum 25(OH)D level of 20 ng/mL and notes that targeting a higher threshold value of 30 ng/mL is reasonable.19 The daily requirement for vitamin D3, 800 IU to 1,000 IU, is a good starting point for supplementation.4 Measurement of 1,25(OH)2D levels lacks value and is not recommended for patients with PHPT. Calcium intake should follow established guidelines and is not limited in PHPT.19

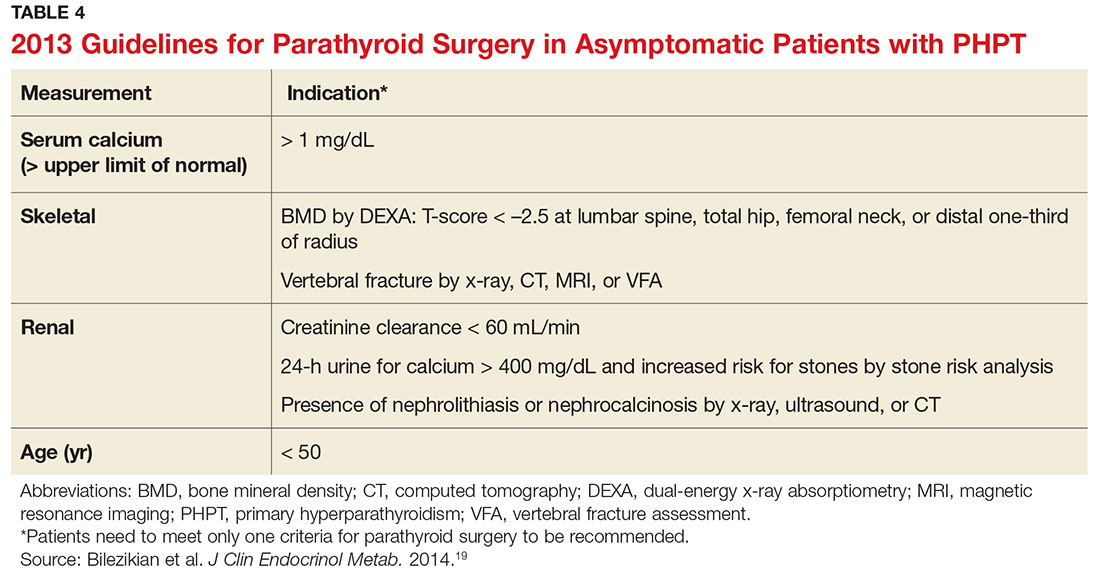

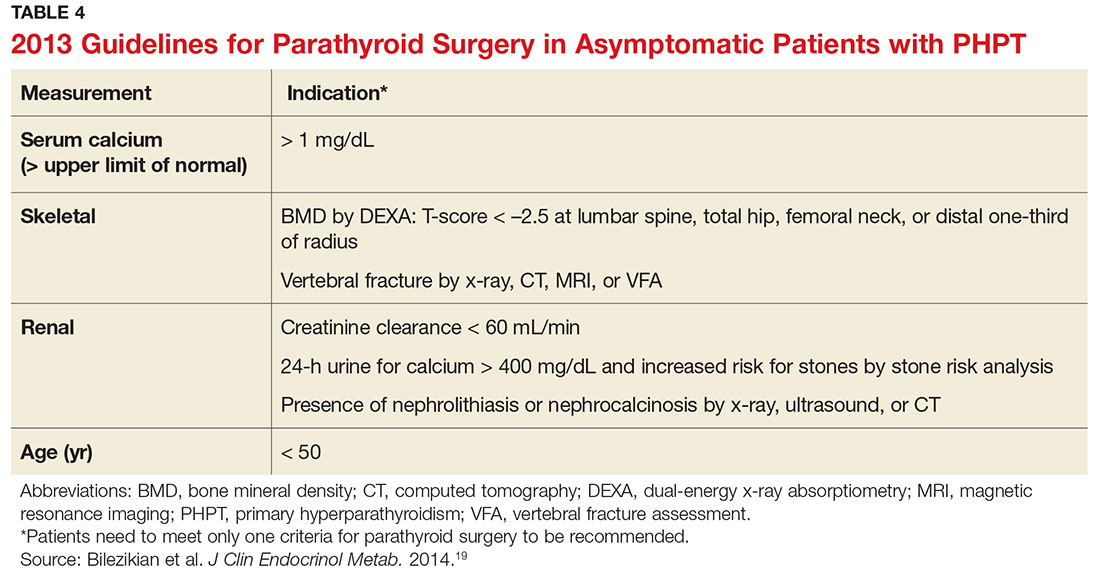

Surgical management

Surgical management is indicated for symptomatic patients.23 Indications include nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, osteitis fibrosa cystica, or osteoporosis. Surgery is considered appropriate for individuals who do not meet these criteria if there are no medical contraindications.14 The Fourth International Workshop on the Management of Asymptomatic Primary Hyperparathyroidism revised the indications for surgery in 2014 to include asymptomatic patients, since surgery is the only definitive treatment for PHPT. Current guidelines for when to recommend surgery in the asymptomatic patient with PHPT are listed in Table 4.19