User login

In PCOS, too much sitting means higher glucose levels

ORLANDO – Prolonged time spent sitting was associated with higher post–glucose tolerance test blood glucose levels among less-active women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

The trend toward this effect persisted even after researchers controlled for age and body mass index, and was not seen in women who were more active.

The results showed a “compounded adverse metabolic effect of prolonged sitting time in women with PCOS who do not achieve exercise goals,” according to Eleni Greenwood, MD, and her colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco, department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences.

“In PCOS, insulin resistance is tissue specific and occurs in the skeletal muscle,” said Dr. Greenwood, a fellow in the reproductive endocrinology and infertility program at the University of California, San Francisco. Diet and exercise are primary interventions to help with these sequelae. In the general population, prolonged time spent being sedentary is associated with type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even some cancers.

Because “the adverse effects of sitting are not reversed through exercise,” as Dr. Greenwood and her colleagues pointed out, the study sought to ascertain whether worse metabolic parameters would be seen in women with PCOS who had had more sedentary time, and whether the association would be independent of exercise status.

Accordingly, the investigators conducted a cross-sectional study of 324 women who met Rotterdam criteria for PCOS. The results were presented during a poster session at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Patients took the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, and responses were used to determine activity levels and amounts of sedentary times. Other measurements taken at the interdisciplinary clinic where the patients were seen included anthropometric measurements, as well as the results of serum lipid levels, fasting glucose and insulin levels, and the results of a 75-g, 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

In their analysis, the investigators calculated homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and used multivariable analysis to find correlations and eliminate potentially confounding variables. In a further attempt to eliminate confounders, Dr. Greenwood and her colleagues asked patients to stop hormonal contraceptive methods and insulin sensitizing medications 30 days before beginning the study.

The investigators looked at the women’s exercise status, meaning whether they had achieved the level of activity recommended by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. However, they also asked the women to report how sedentary they were, measured by the number of hours spent sitting in a day.

It would theoretically be possible for an individual to be very “active,” exercising vigorously for 2 hours each day, but also very “sedentary,” sitting for much of the rest of her waking hours.

Overall, two-thirds of the women (217, 67%) met the activity goals outlined by the HHS. That consisted of exercising enough to achieve 600 metabolic equivalents per week. If the women sat for more than 6 hours a day, they were judged to be sedentary. Of the inactive women, 35% (37) sat for 6 or fewer hours per day, compared with 44% (94) of the active women.

Though the results did not reach statistical significance, HOMA-IR and post-OGTT glucose levels tended to be lower among those who sat less (1.93 vs. 2.73, P = .10; 99 mg/dL vs. 107 mg/dL, P = .09).

Looking at just the inactive group, less sitting time was associated with significantly lower post-OGTT glucose levels (99.1 mg/dL vs. 117.6 mg/dL, P = .03). This difference was not seen among the group of women judged to be active.

“Our results indicate a compounded adverse metabolic effect of prolonged sitting time in women with PCOS who do not achieve exercise goals,” wrote Dr. Greenwood and her collaborators.

Because PCOS pathophysiology can be “disrupted” by an improvement in insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health, “women with PCOS should be counseled regarding strategies for reducing sedentary time, in addition to improving exercise and diet, as a means of improving metabolic health,” they said.

Dr. Greenwood and her colleagues reported no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

ORLANDO – Prolonged time spent sitting was associated with higher post–glucose tolerance test blood glucose levels among less-active women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

The trend toward this effect persisted even after researchers controlled for age and body mass index, and was not seen in women who were more active.

The results showed a “compounded adverse metabolic effect of prolonged sitting time in women with PCOS who do not achieve exercise goals,” according to Eleni Greenwood, MD, and her colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco, department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences.

“In PCOS, insulin resistance is tissue specific and occurs in the skeletal muscle,” said Dr. Greenwood, a fellow in the reproductive endocrinology and infertility program at the University of California, San Francisco. Diet and exercise are primary interventions to help with these sequelae. In the general population, prolonged time spent being sedentary is associated with type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even some cancers.

Because “the adverse effects of sitting are not reversed through exercise,” as Dr. Greenwood and her colleagues pointed out, the study sought to ascertain whether worse metabolic parameters would be seen in women with PCOS who had had more sedentary time, and whether the association would be independent of exercise status.

Accordingly, the investigators conducted a cross-sectional study of 324 women who met Rotterdam criteria for PCOS. The results were presented during a poster session at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Patients took the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, and responses were used to determine activity levels and amounts of sedentary times. Other measurements taken at the interdisciplinary clinic where the patients were seen included anthropometric measurements, as well as the results of serum lipid levels, fasting glucose and insulin levels, and the results of a 75-g, 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

In their analysis, the investigators calculated homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and used multivariable analysis to find correlations and eliminate potentially confounding variables. In a further attempt to eliminate confounders, Dr. Greenwood and her colleagues asked patients to stop hormonal contraceptive methods and insulin sensitizing medications 30 days before beginning the study.

The investigators looked at the women’s exercise status, meaning whether they had achieved the level of activity recommended by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. However, they also asked the women to report how sedentary they were, measured by the number of hours spent sitting in a day.

It would theoretically be possible for an individual to be very “active,” exercising vigorously for 2 hours each day, but also very “sedentary,” sitting for much of the rest of her waking hours.

Overall, two-thirds of the women (217, 67%) met the activity goals outlined by the HHS. That consisted of exercising enough to achieve 600 metabolic equivalents per week. If the women sat for more than 6 hours a day, they were judged to be sedentary. Of the inactive women, 35% (37) sat for 6 or fewer hours per day, compared with 44% (94) of the active women.

Though the results did not reach statistical significance, HOMA-IR and post-OGTT glucose levels tended to be lower among those who sat less (1.93 vs. 2.73, P = .10; 99 mg/dL vs. 107 mg/dL, P = .09).

Looking at just the inactive group, less sitting time was associated with significantly lower post-OGTT glucose levels (99.1 mg/dL vs. 117.6 mg/dL, P = .03). This difference was not seen among the group of women judged to be active.

“Our results indicate a compounded adverse metabolic effect of prolonged sitting time in women with PCOS who do not achieve exercise goals,” wrote Dr. Greenwood and her collaborators.

Because PCOS pathophysiology can be “disrupted” by an improvement in insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health, “women with PCOS should be counseled regarding strategies for reducing sedentary time, in addition to improving exercise and diet, as a means of improving metabolic health,” they said.

Dr. Greenwood and her colleagues reported no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

ORLANDO – Prolonged time spent sitting was associated with higher post–glucose tolerance test blood glucose levels among less-active women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

The trend toward this effect persisted even after researchers controlled for age and body mass index, and was not seen in women who were more active.

The results showed a “compounded adverse metabolic effect of prolonged sitting time in women with PCOS who do not achieve exercise goals,” according to Eleni Greenwood, MD, and her colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco, department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences.

“In PCOS, insulin resistance is tissue specific and occurs in the skeletal muscle,” said Dr. Greenwood, a fellow in the reproductive endocrinology and infertility program at the University of California, San Francisco. Diet and exercise are primary interventions to help with these sequelae. In the general population, prolonged time spent being sedentary is associated with type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even some cancers.

Because “the adverse effects of sitting are not reversed through exercise,” as Dr. Greenwood and her colleagues pointed out, the study sought to ascertain whether worse metabolic parameters would be seen in women with PCOS who had had more sedentary time, and whether the association would be independent of exercise status.

Accordingly, the investigators conducted a cross-sectional study of 324 women who met Rotterdam criteria for PCOS. The results were presented during a poster session at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Patients took the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, and responses were used to determine activity levels and amounts of sedentary times. Other measurements taken at the interdisciplinary clinic where the patients were seen included anthropometric measurements, as well as the results of serum lipid levels, fasting glucose and insulin levels, and the results of a 75-g, 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

In their analysis, the investigators calculated homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and used multivariable analysis to find correlations and eliminate potentially confounding variables. In a further attempt to eliminate confounders, Dr. Greenwood and her colleagues asked patients to stop hormonal contraceptive methods and insulin sensitizing medications 30 days before beginning the study.

The investigators looked at the women’s exercise status, meaning whether they had achieved the level of activity recommended by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. However, they also asked the women to report how sedentary they were, measured by the number of hours spent sitting in a day.

It would theoretically be possible for an individual to be very “active,” exercising vigorously for 2 hours each day, but also very “sedentary,” sitting for much of the rest of her waking hours.

Overall, two-thirds of the women (217, 67%) met the activity goals outlined by the HHS. That consisted of exercising enough to achieve 600 metabolic equivalents per week. If the women sat for more than 6 hours a day, they were judged to be sedentary. Of the inactive women, 35% (37) sat for 6 or fewer hours per day, compared with 44% (94) of the active women.

Though the results did not reach statistical significance, HOMA-IR and post-OGTT glucose levels tended to be lower among those who sat less (1.93 vs. 2.73, P = .10; 99 mg/dL vs. 107 mg/dL, P = .09).

Looking at just the inactive group, less sitting time was associated with significantly lower post-OGTT glucose levels (99.1 mg/dL vs. 117.6 mg/dL, P = .03). This difference was not seen among the group of women judged to be active.

“Our results indicate a compounded adverse metabolic effect of prolonged sitting time in women with PCOS who do not achieve exercise goals,” wrote Dr. Greenwood and her collaborators.

Because PCOS pathophysiology can be “disrupted” by an improvement in insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health, “women with PCOS should be counseled regarding strategies for reducing sedentary time, in addition to improving exercise and diet, as a means of improving metabolic health,” they said.

Dr. Greenwood and her colleagues reported no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT ENDO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Less-active women who also had prolonged sitting time had significantly higher post–oral glucose tolerance test levels (99.1 mg/dL vs. 117.6 mg/dL, P = .03).

Data source: Cross-sectional study of 324 women who met Rotterdam criteria for PCOS.

Disclosures: None of the study authors reported relevant disclosures, and no external source of funding was reported.

Blepharoplasty Markers: Comparison of Ink Drying Time and Ink Spread

Blepharoplasty, or surgical manipulation of the upper and/or lower eyelids, is a commonly performed cosmetic procedure to improve the appearance and function of the eyelids by repositioning and/or removing excess skin and soft tissue from the eyelids, most often through external incisions that minimize scarring and maximize the aesthetic outcomes of the surgery. Therefore, the placement of the incisions is an important determinant of the surgical outcome, and the preoperative marking of the eyelids to indicate where the incisions should be placed is a crucial part of preparation for the surgery.

Preoperative marking has unique challenges due to the dynamicity of the eyelids and the delicate nature of the surgery. The mark must be narrow to minimize the risk of placing the incision higher or lower than intended. The mark also must dry quickly because the patient may blink and create multiple impressions of the marking on skinfolds in contact with the wet ink. Fast drying of the ink used to create the marks improves the efficiency and clarity of the presurgical planning.

We present data on the performance of the various blepharoplasty markers regarding drying time and ink spread width based on an evaluation of 13 surgical markers.

Methods

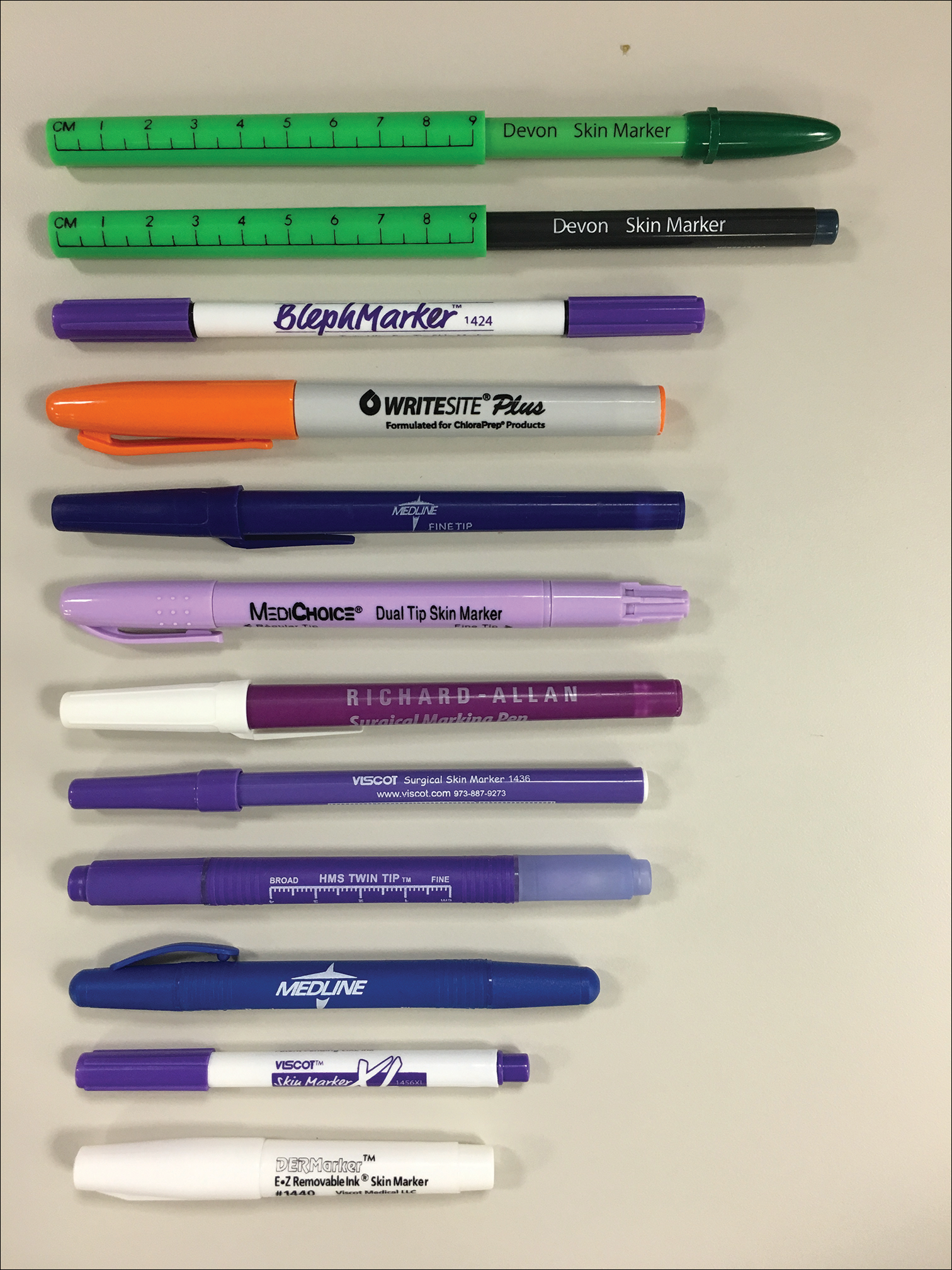

Eleven unique fine tip (FT) markers and 2 standard tip (ST) markers were obtained based on their accessibility at the researchers’ home institution and availability for direct purchase in small quantities from the distributors (Figure 1). Four markers were double tipped with one FT end and one ST end; for these markers, only the FT end was studied. The experiments were conducted on the bilateral upper eyelids and on hairless patches of skin of a single patient in a minor procedure room with surgical lighting and minimal draft of air. The sole experimenter (J.M.K.) conducting the study was not blinded.

The drying time of each marker was measured by marking 1-in lines on a patch of hairless skin that was first cleaned with an alcohol pad, then dried. Drying time for each marking was measured in increments of 5 seconds; at each time point, the markings were wiped with a single-ply, light-duty tissue under the weight of 10 US quarters to ensure that the same weight/pressure was applied when wiping the skin. Smudges observed with the naked eye on either the wipe or the patients’ skin were interpreted as nondry status of the marking. The first time point at which a marking was found to have no visible smudges either on the skin or the wipe was recorded as the drying time of the respective marker.

Ink spread was measured on clean eyelid skin by drawing curved lines along the natural crease as would be done for actual blepharoplasty planning. Each line was allowed to dry for 2 minutes. The greatest perpendicular spread width along the line observed with the naked eye was measured using a digital Vernier caliper with 0.01-mm graduations. Three measurements were obtained per marker and the values averaged to arrive at the final spread width.

Results

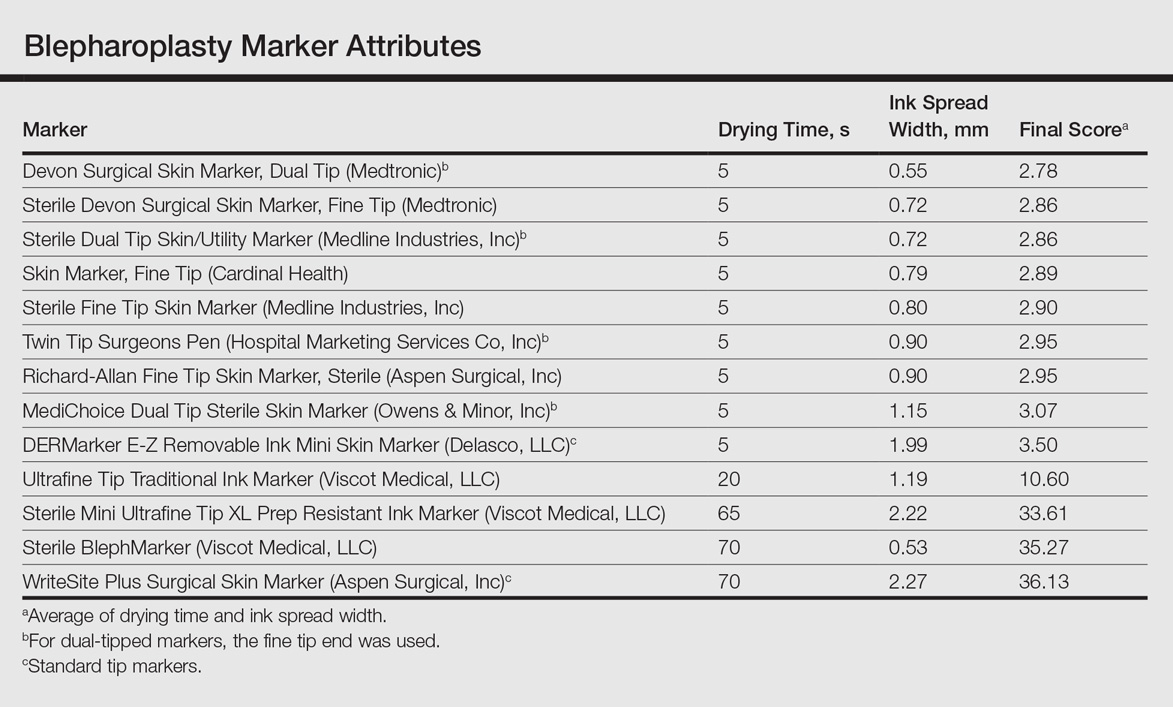

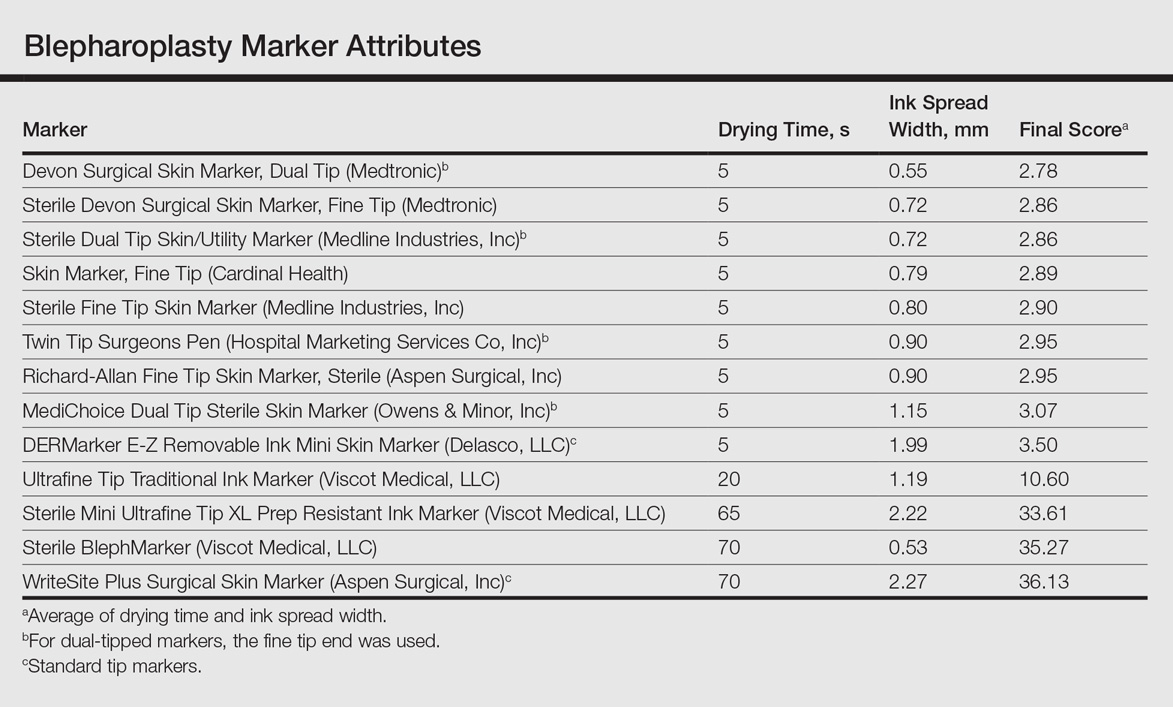

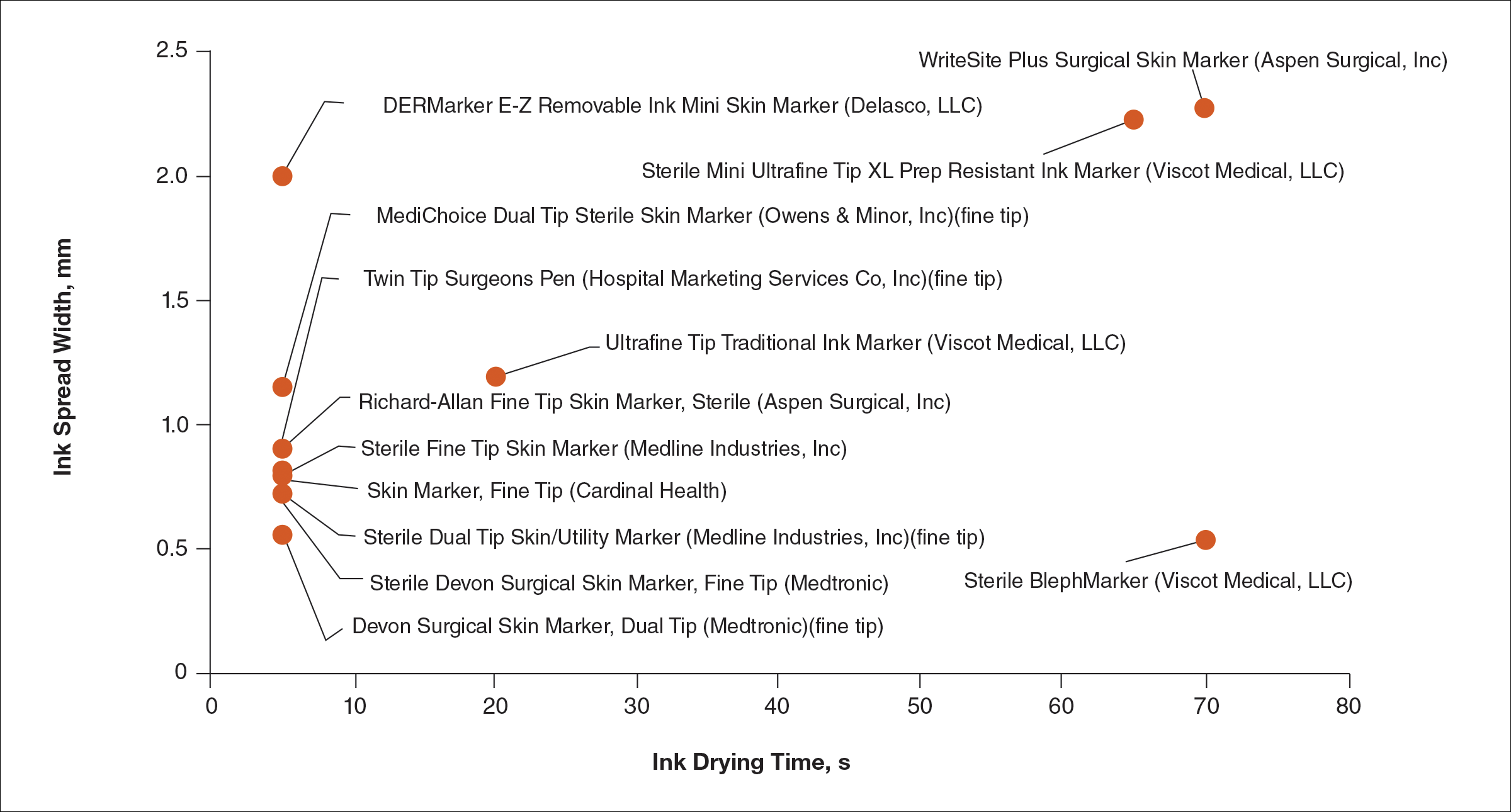

Drying time among the 13 total markers (11 FT and 2 ST) ranged from 5 to 70 seconds, with a mean of 20.8 seconds and median of 5 seconds (Table). The drying time for the DERMarker E-Z Removable Ink Mini Skin Marker (Delasco, LLC) with an ST was 5 seconds, while the drying time for the other ST marker, WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker (Aspen Surgical, Inc), was 70 seconds. The FT markers spanned the entire range of drying times. The ink spread width among the markers ranged from 0.53 to 2.27 mm with a median of 0.9 mm and mean of 1.13 mm (Table). The 2 ST markers were found to make some of the widest marks measured, including the WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker, a nonsterile ST marker that created the widest ink marks. The second widest mark was made by an FT marker (Sterile Mini Ultrafine Tip XL Prep Resistant Ink Marker [Viscot Medical, LLC]).

To prioritize short drying time coupled with minimal ink spread width, the values associated with each marker were averaged to arrive at the overall score for each marker. The smaller the overall score, the higher we ranked the marker. The Devon Surgical Skin Marker, Dual Tip (Medtronic) ranked the highest among the 13 markers with a final score of 2.78. Runner-up markers included the Sterile Devon Surgical Skin marker, Fine Tip (Medtronic)(final score, 2.86); the Sterile Dual Tip Skin/Utility Marker (Medline Industries, Inc)(final score, 2.86); and the Skin Marker, Fine Tip (Cardinal Health)(final score, 2.89). The 2 lowest-ranking markers were the WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker, an ST marker (final score, 36.13), followed by the Sterile BlephMarker (Viscot Medical, LLC)(final score, 35.27).

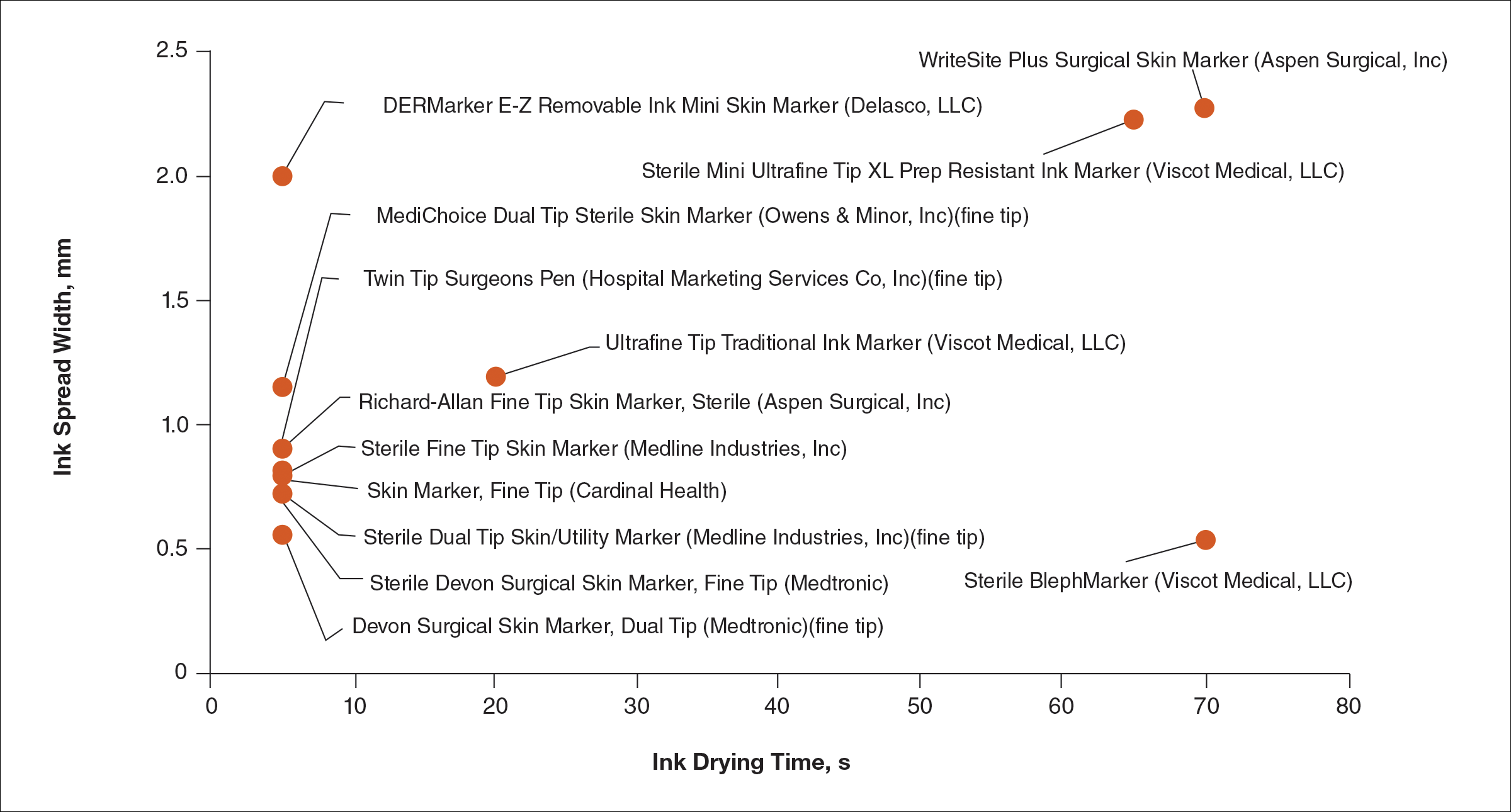

Figure 2 shows the drying time and ink spread width for all 13 markers.

Comment

Blepharoplasty surgeons generally agree that meticulous presurgical planning with marking of the eyelids is critical for successful surgical outcomes.1,2 Fine tip markers have been recommended for this purpose due to the relative precision of the marks, but the prerequisite of these markers is that the marks must have minimal ink spread through skinfolds to allow for precision as well as short drying time to avoid unintentional duplication of the ink on overlapping skin, especially with the likely chance of reflexive blinking by the patient. The associated assumption is that FT markers automatically leave precise marks with minimal drying time. This study systemically compared these 2 qualities for 13 markers, and the results are notable for the unexpected wide range of performance. Although most of the FT markers had ink spread width of less than 1 mm, the Sterile Mini Ultrafine Tip XL Prep Resistant Ink Marker was an outlier among FT markers, with ink spread greater than 2 mm, making it too broad and imprecise for practical use. This result indicates that not every FT marker actually makes fine marks. The 2 ST markers in the study—DERMarker E-Z Removable Ink Mini Skin Marker and WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker—left broad marks as anticipated.

The drying time of the markers also ranged from 5 to 70 seconds among both FT and ST markers. Indeed, most of the FT markers were dry at or before 5 seconds of marking, but 2 FT markers—Sterile Mini Ultrafine Tip XL Prep Resistant Ink Marker and Sterile BlephMarker—dried at 65 and 70 seconds, respectively. Such a long drying time would be considered impractical for use in blepharoplasty marking and also unexpected of FT markers, which usually are marketed for their precision and efficiency. Notable in the discussion of drying time is that one of the 2 ST markers in the study, the DERMarker E-Z Removable Ink Mini Skin Marker, had the shortest possible drying time of 5 seconds, while the other ST marker, WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker, dried at 70 seconds. This observation coupled with the unexpected results of broad marks and long drying time for some of the FT markers indicates that a surgeon cannot simply assume that a FT marker would provide marks with precision and fast drying time, or that an ST marker would be the opposite.

Future directions for study include the addition of other markers and the extent of resistance to antiseptic routines that can fade the markings.

Conclusion

Among the 13 markers studied, FT markers typically had the shortest drying time and least ink

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Laura B. Hall, MD (New Haven, Connecticut), for her participation as the volunteer in this study.

- Hartstein ME, Massry GG, Holds JB. Pearls and Pitfalls in Cosmetic Oculoplastic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2015.

- Gladstone G, Black EH. Oculoplastic Surgery Atlas. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2005.

Blepharoplasty, or surgical manipulation of the upper and/or lower eyelids, is a commonly performed cosmetic procedure to improve the appearance and function of the eyelids by repositioning and/or removing excess skin and soft tissue from the eyelids, most often through external incisions that minimize scarring and maximize the aesthetic outcomes of the surgery. Therefore, the placement of the incisions is an important determinant of the surgical outcome, and the preoperative marking of the eyelids to indicate where the incisions should be placed is a crucial part of preparation for the surgery.

Preoperative marking has unique challenges due to the dynamicity of the eyelids and the delicate nature of the surgery. The mark must be narrow to minimize the risk of placing the incision higher or lower than intended. The mark also must dry quickly because the patient may blink and create multiple impressions of the marking on skinfolds in contact with the wet ink. Fast drying of the ink used to create the marks improves the efficiency and clarity of the presurgical planning.

We present data on the performance of the various blepharoplasty markers regarding drying time and ink spread width based on an evaluation of 13 surgical markers.

Methods

Eleven unique fine tip (FT) markers and 2 standard tip (ST) markers were obtained based on their accessibility at the researchers’ home institution and availability for direct purchase in small quantities from the distributors (Figure 1). Four markers were double tipped with one FT end and one ST end; for these markers, only the FT end was studied. The experiments were conducted on the bilateral upper eyelids and on hairless patches of skin of a single patient in a minor procedure room with surgical lighting and minimal draft of air. The sole experimenter (J.M.K.) conducting the study was not blinded.

The drying time of each marker was measured by marking 1-in lines on a patch of hairless skin that was first cleaned with an alcohol pad, then dried. Drying time for each marking was measured in increments of 5 seconds; at each time point, the markings were wiped with a single-ply, light-duty tissue under the weight of 10 US quarters to ensure that the same weight/pressure was applied when wiping the skin. Smudges observed with the naked eye on either the wipe or the patients’ skin were interpreted as nondry status of the marking. The first time point at which a marking was found to have no visible smudges either on the skin or the wipe was recorded as the drying time of the respective marker.

Ink spread was measured on clean eyelid skin by drawing curved lines along the natural crease as would be done for actual blepharoplasty planning. Each line was allowed to dry for 2 minutes. The greatest perpendicular spread width along the line observed with the naked eye was measured using a digital Vernier caliper with 0.01-mm graduations. Three measurements were obtained per marker and the values averaged to arrive at the final spread width.

Results

Drying time among the 13 total markers (11 FT and 2 ST) ranged from 5 to 70 seconds, with a mean of 20.8 seconds and median of 5 seconds (Table). The drying time for the DERMarker E-Z Removable Ink Mini Skin Marker (Delasco, LLC) with an ST was 5 seconds, while the drying time for the other ST marker, WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker (Aspen Surgical, Inc), was 70 seconds. The FT markers spanned the entire range of drying times. The ink spread width among the markers ranged from 0.53 to 2.27 mm with a median of 0.9 mm and mean of 1.13 mm (Table). The 2 ST markers were found to make some of the widest marks measured, including the WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker, a nonsterile ST marker that created the widest ink marks. The second widest mark was made by an FT marker (Sterile Mini Ultrafine Tip XL Prep Resistant Ink Marker [Viscot Medical, LLC]).

To prioritize short drying time coupled with minimal ink spread width, the values associated with each marker were averaged to arrive at the overall score for each marker. The smaller the overall score, the higher we ranked the marker. The Devon Surgical Skin Marker, Dual Tip (Medtronic) ranked the highest among the 13 markers with a final score of 2.78. Runner-up markers included the Sterile Devon Surgical Skin marker, Fine Tip (Medtronic)(final score, 2.86); the Sterile Dual Tip Skin/Utility Marker (Medline Industries, Inc)(final score, 2.86); and the Skin Marker, Fine Tip (Cardinal Health)(final score, 2.89). The 2 lowest-ranking markers were the WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker, an ST marker (final score, 36.13), followed by the Sterile BlephMarker (Viscot Medical, LLC)(final score, 35.27).

Figure 2 shows the drying time and ink spread width for all 13 markers.

Comment

Blepharoplasty surgeons generally agree that meticulous presurgical planning with marking of the eyelids is critical for successful surgical outcomes.1,2 Fine tip markers have been recommended for this purpose due to the relative precision of the marks, but the prerequisite of these markers is that the marks must have minimal ink spread through skinfolds to allow for precision as well as short drying time to avoid unintentional duplication of the ink on overlapping skin, especially with the likely chance of reflexive blinking by the patient. The associated assumption is that FT markers automatically leave precise marks with minimal drying time. This study systemically compared these 2 qualities for 13 markers, and the results are notable for the unexpected wide range of performance. Although most of the FT markers had ink spread width of less than 1 mm, the Sterile Mini Ultrafine Tip XL Prep Resistant Ink Marker was an outlier among FT markers, with ink spread greater than 2 mm, making it too broad and imprecise for practical use. This result indicates that not every FT marker actually makes fine marks. The 2 ST markers in the study—DERMarker E-Z Removable Ink Mini Skin Marker and WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker—left broad marks as anticipated.

The drying time of the markers also ranged from 5 to 70 seconds among both FT and ST markers. Indeed, most of the FT markers were dry at or before 5 seconds of marking, but 2 FT markers—Sterile Mini Ultrafine Tip XL Prep Resistant Ink Marker and Sterile BlephMarker—dried at 65 and 70 seconds, respectively. Such a long drying time would be considered impractical for use in blepharoplasty marking and also unexpected of FT markers, which usually are marketed for their precision and efficiency. Notable in the discussion of drying time is that one of the 2 ST markers in the study, the DERMarker E-Z Removable Ink Mini Skin Marker, had the shortest possible drying time of 5 seconds, while the other ST marker, WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker, dried at 70 seconds. This observation coupled with the unexpected results of broad marks and long drying time for some of the FT markers indicates that a surgeon cannot simply assume that a FT marker would provide marks with precision and fast drying time, or that an ST marker would be the opposite.

Future directions for study include the addition of other markers and the extent of resistance to antiseptic routines that can fade the markings.

Conclusion

Among the 13 markers studied, FT markers typically had the shortest drying time and least ink

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Laura B. Hall, MD (New Haven, Connecticut), for her participation as the volunteer in this study.

Blepharoplasty, or surgical manipulation of the upper and/or lower eyelids, is a commonly performed cosmetic procedure to improve the appearance and function of the eyelids by repositioning and/or removing excess skin and soft tissue from the eyelids, most often through external incisions that minimize scarring and maximize the aesthetic outcomes of the surgery. Therefore, the placement of the incisions is an important determinant of the surgical outcome, and the preoperative marking of the eyelids to indicate where the incisions should be placed is a crucial part of preparation for the surgery.

Preoperative marking has unique challenges due to the dynamicity of the eyelids and the delicate nature of the surgery. The mark must be narrow to minimize the risk of placing the incision higher or lower than intended. The mark also must dry quickly because the patient may blink and create multiple impressions of the marking on skinfolds in contact with the wet ink. Fast drying of the ink used to create the marks improves the efficiency and clarity of the presurgical planning.

We present data on the performance of the various blepharoplasty markers regarding drying time and ink spread width based on an evaluation of 13 surgical markers.

Methods

Eleven unique fine tip (FT) markers and 2 standard tip (ST) markers were obtained based on their accessibility at the researchers’ home institution and availability for direct purchase in small quantities from the distributors (Figure 1). Four markers were double tipped with one FT end and one ST end; for these markers, only the FT end was studied. The experiments were conducted on the bilateral upper eyelids and on hairless patches of skin of a single patient in a minor procedure room with surgical lighting and minimal draft of air. The sole experimenter (J.M.K.) conducting the study was not blinded.

The drying time of each marker was measured by marking 1-in lines on a patch of hairless skin that was first cleaned with an alcohol pad, then dried. Drying time for each marking was measured in increments of 5 seconds; at each time point, the markings were wiped with a single-ply, light-duty tissue under the weight of 10 US quarters to ensure that the same weight/pressure was applied when wiping the skin. Smudges observed with the naked eye on either the wipe or the patients’ skin were interpreted as nondry status of the marking. The first time point at which a marking was found to have no visible smudges either on the skin or the wipe was recorded as the drying time of the respective marker.

Ink spread was measured on clean eyelid skin by drawing curved lines along the natural crease as would be done for actual blepharoplasty planning. Each line was allowed to dry for 2 minutes. The greatest perpendicular spread width along the line observed with the naked eye was measured using a digital Vernier caliper with 0.01-mm graduations. Three measurements were obtained per marker and the values averaged to arrive at the final spread width.

Results

Drying time among the 13 total markers (11 FT and 2 ST) ranged from 5 to 70 seconds, with a mean of 20.8 seconds and median of 5 seconds (Table). The drying time for the DERMarker E-Z Removable Ink Mini Skin Marker (Delasco, LLC) with an ST was 5 seconds, while the drying time for the other ST marker, WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker (Aspen Surgical, Inc), was 70 seconds. The FT markers spanned the entire range of drying times. The ink spread width among the markers ranged from 0.53 to 2.27 mm with a median of 0.9 mm and mean of 1.13 mm (Table). The 2 ST markers were found to make some of the widest marks measured, including the WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker, a nonsterile ST marker that created the widest ink marks. The second widest mark was made by an FT marker (Sterile Mini Ultrafine Tip XL Prep Resistant Ink Marker [Viscot Medical, LLC]).

To prioritize short drying time coupled with minimal ink spread width, the values associated with each marker were averaged to arrive at the overall score for each marker. The smaller the overall score, the higher we ranked the marker. The Devon Surgical Skin Marker, Dual Tip (Medtronic) ranked the highest among the 13 markers with a final score of 2.78. Runner-up markers included the Sterile Devon Surgical Skin marker, Fine Tip (Medtronic)(final score, 2.86); the Sterile Dual Tip Skin/Utility Marker (Medline Industries, Inc)(final score, 2.86); and the Skin Marker, Fine Tip (Cardinal Health)(final score, 2.89). The 2 lowest-ranking markers were the WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker, an ST marker (final score, 36.13), followed by the Sterile BlephMarker (Viscot Medical, LLC)(final score, 35.27).

Figure 2 shows the drying time and ink spread width for all 13 markers.

Comment

Blepharoplasty surgeons generally agree that meticulous presurgical planning with marking of the eyelids is critical for successful surgical outcomes.1,2 Fine tip markers have been recommended for this purpose due to the relative precision of the marks, but the prerequisite of these markers is that the marks must have minimal ink spread through skinfolds to allow for precision as well as short drying time to avoid unintentional duplication of the ink on overlapping skin, especially with the likely chance of reflexive blinking by the patient. The associated assumption is that FT markers automatically leave precise marks with minimal drying time. This study systemically compared these 2 qualities for 13 markers, and the results are notable for the unexpected wide range of performance. Although most of the FT markers had ink spread width of less than 1 mm, the Sterile Mini Ultrafine Tip XL Prep Resistant Ink Marker was an outlier among FT markers, with ink spread greater than 2 mm, making it too broad and imprecise for practical use. This result indicates that not every FT marker actually makes fine marks. The 2 ST markers in the study—DERMarker E-Z Removable Ink Mini Skin Marker and WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker—left broad marks as anticipated.

The drying time of the markers also ranged from 5 to 70 seconds among both FT and ST markers. Indeed, most of the FT markers were dry at or before 5 seconds of marking, but 2 FT markers—Sterile Mini Ultrafine Tip XL Prep Resistant Ink Marker and Sterile BlephMarker—dried at 65 and 70 seconds, respectively. Such a long drying time would be considered impractical for use in blepharoplasty marking and also unexpected of FT markers, which usually are marketed for their precision and efficiency. Notable in the discussion of drying time is that one of the 2 ST markers in the study, the DERMarker E-Z Removable Ink Mini Skin Marker, had the shortest possible drying time of 5 seconds, while the other ST marker, WriteSite Plus Surgical Skin Marker, dried at 70 seconds. This observation coupled with the unexpected results of broad marks and long drying time for some of the FT markers indicates that a surgeon cannot simply assume that a FT marker would provide marks with precision and fast drying time, or that an ST marker would be the opposite.

Future directions for study include the addition of other markers and the extent of resistance to antiseptic routines that can fade the markings.

Conclusion

Among the 13 markers studied, FT markers typically had the shortest drying time and least ink

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Laura B. Hall, MD (New Haven, Connecticut), for her participation as the volunteer in this study.

- Hartstein ME, Massry GG, Holds JB. Pearls and Pitfalls in Cosmetic Oculoplastic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2015.

- Gladstone G, Black EH. Oculoplastic Surgery Atlas. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2005.

- Hartstein ME, Massry GG, Holds JB. Pearls and Pitfalls in Cosmetic Oculoplastic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2015.

- Gladstone G, Black EH. Oculoplastic Surgery Atlas. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2005.

Resident Pearl

Based on the data presented in this study, blepharoplasty surgeons may choose to use the markers shown to have measurably short drying time and minimal ink spread to maximize efficiency of preincisional lid marking.

Risk of Migraine Is Increased Among the Obese and Underweight

Obesity and underweight status are associated with an increased risk of migraine, according to research published online ahead of print April 12 in Neurology. Age and sex are important covariates of this association.

“As obesity and being underweight are potentially modifiable risk factors for migraine, awareness of these risk factors is vital for both people with migraine and doctors,” said B. Lee Peterlin, DO, Director of Headache Research at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “More research is needed to determine whether efforts to help people lose or gain weight could lower their risk for migraine.”

Previous studies have suggested an association between obesity and increased risk of migraine. These studies differed, however, in the populations they included, the way in which they categorized obesity status, and the way in which they were designed and conducted.

To further evaluate this possible association, Dr. Peterlin and colleagues searched the peer-reviewed literature for studies related to body composition status, as estimated by BMI and World Health Organization (WHO) physical status categories, and migraine. Their meta-analysis included 12 studies that encompassed data from 288,981 participants between ages 18 and 98.

After adjusting for age and sex, Dr. Peterlin and colleagues found that risk of migraine in people with obesity was increased by 27%, compared with people of normal weight. The risk remained increased after multivariate adjustments. Similarly, the age- and sex-adjusted risk of migraine was increased among overweight participants, but the result was not significant after multivariate adjustments were performed. The age- and sex-adjusted risk of migraine in underweight people was increased by 13%, compared with people of normal weight, and remained increased after multivariate adjustments.

“It is not clear how body composition could affect migraine,” said Dr. Peterlin. “Adipose tissue, or fatty tissue, secretes a wide range of molecules that could play a role in developing or triggering migraine. It is also possible that other factors such as changes in physical activity, medications, or other conditions such as depression play a role in the relationship between migraine and body composition.”

Half of the studies included in the meta-analysis relied on self-report of migraine and did not use International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria, thus introducing the potential for recall bias. Furthermore, eight of the studies used self-report of BMI. Previous data have indicated that people with migraine are more likely to underestimate their BMI.

One of the meta-analysis’s strengths, however, is its large sample size. Another is its use of uniform and consistent obesity status categories based on the WHO physical status categories for non-Asian populations.

Additional research could “advance our understanding of migraine and lead to the development of targeted therapeutic strategies based on obesity status,” Dr. Peterlin and colleagues concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Gelaye B, Sacco S, Brown WJ, et al. Body composition status and the risk of migraine: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2017 April 12 [Epub ahead of print].

Obesity and underweight status are associated with an increased risk of migraine, according to research published online ahead of print April 12 in Neurology. Age and sex are important covariates of this association.

“As obesity and being underweight are potentially modifiable risk factors for migraine, awareness of these risk factors is vital for both people with migraine and doctors,” said B. Lee Peterlin, DO, Director of Headache Research at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “More research is needed to determine whether efforts to help people lose or gain weight could lower their risk for migraine.”

Previous studies have suggested an association between obesity and increased risk of migraine. These studies differed, however, in the populations they included, the way in which they categorized obesity status, and the way in which they were designed and conducted.

To further evaluate this possible association, Dr. Peterlin and colleagues searched the peer-reviewed literature for studies related to body composition status, as estimated by BMI and World Health Organization (WHO) physical status categories, and migraine. Their meta-analysis included 12 studies that encompassed data from 288,981 participants between ages 18 and 98.

After adjusting for age and sex, Dr. Peterlin and colleagues found that risk of migraine in people with obesity was increased by 27%, compared with people of normal weight. The risk remained increased after multivariate adjustments. Similarly, the age- and sex-adjusted risk of migraine was increased among overweight participants, but the result was not significant after multivariate adjustments were performed. The age- and sex-adjusted risk of migraine in underweight people was increased by 13%, compared with people of normal weight, and remained increased after multivariate adjustments.

“It is not clear how body composition could affect migraine,” said Dr. Peterlin. “Adipose tissue, or fatty tissue, secretes a wide range of molecules that could play a role in developing or triggering migraine. It is also possible that other factors such as changes in physical activity, medications, or other conditions such as depression play a role in the relationship between migraine and body composition.”

Half of the studies included in the meta-analysis relied on self-report of migraine and did not use International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria, thus introducing the potential for recall bias. Furthermore, eight of the studies used self-report of BMI. Previous data have indicated that people with migraine are more likely to underestimate their BMI.

One of the meta-analysis’s strengths, however, is its large sample size. Another is its use of uniform and consistent obesity status categories based on the WHO physical status categories for non-Asian populations.

Additional research could “advance our understanding of migraine and lead to the development of targeted therapeutic strategies based on obesity status,” Dr. Peterlin and colleagues concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Gelaye B, Sacco S, Brown WJ, et al. Body composition status and the risk of migraine: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2017 April 12 [Epub ahead of print].

Obesity and underweight status are associated with an increased risk of migraine, according to research published online ahead of print April 12 in Neurology. Age and sex are important covariates of this association.

“As obesity and being underweight are potentially modifiable risk factors for migraine, awareness of these risk factors is vital for both people with migraine and doctors,” said B. Lee Peterlin, DO, Director of Headache Research at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “More research is needed to determine whether efforts to help people lose or gain weight could lower their risk for migraine.”

Previous studies have suggested an association between obesity and increased risk of migraine. These studies differed, however, in the populations they included, the way in which they categorized obesity status, and the way in which they were designed and conducted.

To further evaluate this possible association, Dr. Peterlin and colleagues searched the peer-reviewed literature for studies related to body composition status, as estimated by BMI and World Health Organization (WHO) physical status categories, and migraine. Their meta-analysis included 12 studies that encompassed data from 288,981 participants between ages 18 and 98.

After adjusting for age and sex, Dr. Peterlin and colleagues found that risk of migraine in people with obesity was increased by 27%, compared with people of normal weight. The risk remained increased after multivariate adjustments. Similarly, the age- and sex-adjusted risk of migraine was increased among overweight participants, but the result was not significant after multivariate adjustments were performed. The age- and sex-adjusted risk of migraine in underweight people was increased by 13%, compared with people of normal weight, and remained increased after multivariate adjustments.

“It is not clear how body composition could affect migraine,” said Dr. Peterlin. “Adipose tissue, or fatty tissue, secretes a wide range of molecules that could play a role in developing or triggering migraine. It is also possible that other factors such as changes in physical activity, medications, or other conditions such as depression play a role in the relationship between migraine and body composition.”

Half of the studies included in the meta-analysis relied on self-report of migraine and did not use International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria, thus introducing the potential for recall bias. Furthermore, eight of the studies used self-report of BMI. Previous data have indicated that people with migraine are more likely to underestimate their BMI.

One of the meta-analysis’s strengths, however, is its large sample size. Another is its use of uniform and consistent obesity status categories based on the WHO physical status categories for non-Asian populations.

Additional research could “advance our understanding of migraine and lead to the development of targeted therapeutic strategies based on obesity status,” Dr. Peterlin and colleagues concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Gelaye B, Sacco S, Brown WJ, et al. Body composition status and the risk of migraine: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2017 April 12 [Epub ahead of print].

White House pick for mental health czar causes stir

The White House pick for the newly created post of mental health czar has raised some hackles on Capitol Hill.

President Donald Trump recently announced that Elinore “Ellie” F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist whose career has focused on substance abuse and addiction, was his nominee to serve as nation’s first assistant secretary for mental health and substance use. In 2013, Dr. McCance-Katz served as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s first chief medical officer. She resigned after 2 years.

The choice does not sit well with Rep. Tim Murphy (R-Pa.), whose landmark legislation, Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis – ultimately passed as part of the bipartisan 21st Century Cures Act – created the cabinet-level post to help end what many have seen as SAMHSA’s poor performance in meeting the nation’s mental health needs.

“I am stunned the president put forth a nominee who served in a key post at SAMHSA under the previous administration when the agency was actively opposing the transformative changes in H.R. 3717, the original version of my Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act,” Rep. Murphy said in a statement. “After an intensive investigation bringing to light the many leadership failures across the federal government, but particularly at SAMHSA, I drafted strong legislation to fix the broken mental health system. One of the most critical reforms was restructuring the agency, focusing on evidence-based models of care and establishing an assistant secretary within [the Department of Health & Human Services] to put an end to what the Government Accountability Office termed a lack of leadership.”

Key provisions of the legislation include clearer HIPAA language, expanded access to inpatient psychiatric hospital beds, and a stronger and more streamlined federal commitment to evidence-based practices in mental and behavioral health care delivery.

The American Psychiatric Association, however, endorsed the nomination and called for swift confirmation by the Senate. “We look forward to working with her to improve the quality of care of mental health and substance use disorders,” APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, MD, said in a statement.

Currently, Dr. McCance-Katz is the chief medical officer for Rhode Island’s department of behavioral health care, developmental disabilities, and hospitals. Dr. McCance-Katz, widely regarded as an expert in medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders, among other addiction-related specialties, also is a former California department of alcohol and drug programs state medical director.

Since leaving her previous post at SAMHSA, Dr. McCance-Katz has been an outspoken critic of the agency she is now being tapped to run. She once editorialized against what she called its poor performance in addressing the needs of people with serious mental illness and its “hostility toward psychiatric medicine.”

Rep. Murphy’s own reported preference for the role was Michael Welner, MD, a forensic psychiatrist upon whom the congressman – himself a clinical psychologist – relied on in part to help craft his mental health legislation. According to mental health blogger Pete Early – who often writes about his son’s struggles with bipolar disorder – the announcement is a surprise to many who expected Dr. Welner to be the pick. On his blog, Mr. Early wrote that Senate sources had told him that Dr. Welner, who publicly supports President Trump, “had a lock on the job.”

Several other names were floated for the position, according to Mr. Early, including John Wernert, MD, who served as head of Indiana’s mental health policy under then-governor, Vice President Mike Pence, and Miami-Dade County, Fla., Judge Steve Leifman, known for his interest in diverting those with serious mental illness from the criminal justice system and into treatment. However, the judge did not have an advanced medical degree, as stipulated by the law, a provision pushed by Rep. Murphy to safeguard against what he said was SAMHSA’s antipsychiatry stance.

In an APA blog post, APA President Maria A. Oquendo, MD, PhD, said Dr. McCance-Katz would “bring a wealth of knowledge in the prevention, treatment, and recovery of substance use disorders” that challenge the United States. “APA strongly supports her appointment.”

Dr. McCance-Katz’s nomination will go before the Senate’s Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, which is chaired by Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.). His office said the senator “looks forward to learning more about how Dr. McCance-Katz would use her experience in medicine and government to implement the new mental health law passed last Congress to help the one in five adults in this country suffering from a mental illness receive the treatment they need.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The White House pick for the newly created post of mental health czar has raised some hackles on Capitol Hill.

President Donald Trump recently announced that Elinore “Ellie” F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist whose career has focused on substance abuse and addiction, was his nominee to serve as nation’s first assistant secretary for mental health and substance use. In 2013, Dr. McCance-Katz served as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s first chief medical officer. She resigned after 2 years.

The choice does not sit well with Rep. Tim Murphy (R-Pa.), whose landmark legislation, Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis – ultimately passed as part of the bipartisan 21st Century Cures Act – created the cabinet-level post to help end what many have seen as SAMHSA’s poor performance in meeting the nation’s mental health needs.

“I am stunned the president put forth a nominee who served in a key post at SAMHSA under the previous administration when the agency was actively opposing the transformative changes in H.R. 3717, the original version of my Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act,” Rep. Murphy said in a statement. “After an intensive investigation bringing to light the many leadership failures across the federal government, but particularly at SAMHSA, I drafted strong legislation to fix the broken mental health system. One of the most critical reforms was restructuring the agency, focusing on evidence-based models of care and establishing an assistant secretary within [the Department of Health & Human Services] to put an end to what the Government Accountability Office termed a lack of leadership.”

Key provisions of the legislation include clearer HIPAA language, expanded access to inpatient psychiatric hospital beds, and a stronger and more streamlined federal commitment to evidence-based practices in mental and behavioral health care delivery.

The American Psychiatric Association, however, endorsed the nomination and called for swift confirmation by the Senate. “We look forward to working with her to improve the quality of care of mental health and substance use disorders,” APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, MD, said in a statement.

Currently, Dr. McCance-Katz is the chief medical officer for Rhode Island’s department of behavioral health care, developmental disabilities, and hospitals. Dr. McCance-Katz, widely regarded as an expert in medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders, among other addiction-related specialties, also is a former California department of alcohol and drug programs state medical director.

Since leaving her previous post at SAMHSA, Dr. McCance-Katz has been an outspoken critic of the agency she is now being tapped to run. She once editorialized against what she called its poor performance in addressing the needs of people with serious mental illness and its “hostility toward psychiatric medicine.”

Rep. Murphy’s own reported preference for the role was Michael Welner, MD, a forensic psychiatrist upon whom the congressman – himself a clinical psychologist – relied on in part to help craft his mental health legislation. According to mental health blogger Pete Early – who often writes about his son’s struggles with bipolar disorder – the announcement is a surprise to many who expected Dr. Welner to be the pick. On his blog, Mr. Early wrote that Senate sources had told him that Dr. Welner, who publicly supports President Trump, “had a lock on the job.”

Several other names were floated for the position, according to Mr. Early, including John Wernert, MD, who served as head of Indiana’s mental health policy under then-governor, Vice President Mike Pence, and Miami-Dade County, Fla., Judge Steve Leifman, known for his interest in diverting those with serious mental illness from the criminal justice system and into treatment. However, the judge did not have an advanced medical degree, as stipulated by the law, a provision pushed by Rep. Murphy to safeguard against what he said was SAMHSA’s antipsychiatry stance.

In an APA blog post, APA President Maria A. Oquendo, MD, PhD, said Dr. McCance-Katz would “bring a wealth of knowledge in the prevention, treatment, and recovery of substance use disorders” that challenge the United States. “APA strongly supports her appointment.”

Dr. McCance-Katz’s nomination will go before the Senate’s Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, which is chaired by Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.). His office said the senator “looks forward to learning more about how Dr. McCance-Katz would use her experience in medicine and government to implement the new mental health law passed last Congress to help the one in five adults in this country suffering from a mental illness receive the treatment they need.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The White House pick for the newly created post of mental health czar has raised some hackles on Capitol Hill.

President Donald Trump recently announced that Elinore “Ellie” F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist whose career has focused on substance abuse and addiction, was his nominee to serve as nation’s first assistant secretary for mental health and substance use. In 2013, Dr. McCance-Katz served as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s first chief medical officer. She resigned after 2 years.

The choice does not sit well with Rep. Tim Murphy (R-Pa.), whose landmark legislation, Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis – ultimately passed as part of the bipartisan 21st Century Cures Act – created the cabinet-level post to help end what many have seen as SAMHSA’s poor performance in meeting the nation’s mental health needs.

“I am stunned the president put forth a nominee who served in a key post at SAMHSA under the previous administration when the agency was actively opposing the transformative changes in H.R. 3717, the original version of my Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act,” Rep. Murphy said in a statement. “After an intensive investigation bringing to light the many leadership failures across the federal government, but particularly at SAMHSA, I drafted strong legislation to fix the broken mental health system. One of the most critical reforms was restructuring the agency, focusing on evidence-based models of care and establishing an assistant secretary within [the Department of Health & Human Services] to put an end to what the Government Accountability Office termed a lack of leadership.”

Key provisions of the legislation include clearer HIPAA language, expanded access to inpatient psychiatric hospital beds, and a stronger and more streamlined federal commitment to evidence-based practices in mental and behavioral health care delivery.

The American Psychiatric Association, however, endorsed the nomination and called for swift confirmation by the Senate. “We look forward to working with her to improve the quality of care of mental health and substance use disorders,” APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, MD, said in a statement.

Currently, Dr. McCance-Katz is the chief medical officer for Rhode Island’s department of behavioral health care, developmental disabilities, and hospitals. Dr. McCance-Katz, widely regarded as an expert in medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders, among other addiction-related specialties, also is a former California department of alcohol and drug programs state medical director.

Since leaving her previous post at SAMHSA, Dr. McCance-Katz has been an outspoken critic of the agency she is now being tapped to run. She once editorialized against what she called its poor performance in addressing the needs of people with serious mental illness and its “hostility toward psychiatric medicine.”

Rep. Murphy’s own reported preference for the role was Michael Welner, MD, a forensic psychiatrist upon whom the congressman – himself a clinical psychologist – relied on in part to help craft his mental health legislation. According to mental health blogger Pete Early – who often writes about his son’s struggles with bipolar disorder – the announcement is a surprise to many who expected Dr. Welner to be the pick. On his blog, Mr. Early wrote that Senate sources had told him that Dr. Welner, who publicly supports President Trump, “had a lock on the job.”

Several other names were floated for the position, according to Mr. Early, including John Wernert, MD, who served as head of Indiana’s mental health policy under then-governor, Vice President Mike Pence, and Miami-Dade County, Fla., Judge Steve Leifman, known for his interest in diverting those with serious mental illness from the criminal justice system and into treatment. However, the judge did not have an advanced medical degree, as stipulated by the law, a provision pushed by Rep. Murphy to safeguard against what he said was SAMHSA’s antipsychiatry stance.

In an APA blog post, APA President Maria A. Oquendo, MD, PhD, said Dr. McCance-Katz would “bring a wealth of knowledge in the prevention, treatment, and recovery of substance use disorders” that challenge the United States. “APA strongly supports her appointment.”

Dr. McCance-Katz’s nomination will go before the Senate’s Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, which is chaired by Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.). His office said the senator “looks forward to learning more about how Dr. McCance-Katz would use her experience in medicine and government to implement the new mental health law passed last Congress to help the one in five adults in this country suffering from a mental illness receive the treatment they need.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Crossing the personal quality chasm: QI enthusiast to QI leader

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Jennifer Myers, director of quality and safety education at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Even as a junior physician, Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, embraced the complexities of the hospital system and the opportunity to transform patient care. She was one of the first hospitalists to participate in and lead quality improvement (QI) work at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center more than 10 years ago, where, “in that role, I got to know almost everyone in the hospital and got an up-close view of how the hospital works administratively,” she recalled.

The experience taught Dr. Myers how little she knew at that time about hospital operations, and she convinced hospital administrators that a mechanism was needed to prepare the next generation of leaders in QI and patient safety. In 2011, with the support of a career development award from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Dr. Myers formulated a quality and patient safety curriculum for residents of Penn Medicine, as well as a more basic introductory program for medical students.

“You will always do your best in work that you are passionate about,” she said, advising others to do the same when choosing their career pathways. “Find others who are interested in – or frustrated by – the same things that you are, and work with them as you begin to shape your projects. If it’s the opioid epidemic, partner with someone in the hospital with an interest in making informed prescribing decisions. If it’s working with residents in quality, find a chief resident to help you develop an educational pathway or elective.”

Dr. Myers says that hospitalists who function at the intersection of the ICU, the ER, and inpatient care are naturally suited for leadership positions in quality and patient safety, “but, if you are a hospitalist aspiring to be a chief quality or medical officer or (someone) who wants to know the field more deeply, I recommend getting advanced training.”

Hospitalists now have multiple educational opportunities in QI to choose from, but that was not the case 7 years ago when SHM leaders invited Dr. Myers to develop and lead the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA). The 2.5-day program trains medical educators to develop curricula that incorporate quality improvement and safety principles into their local institutions. “We give them the core quality and safety knowledge but also the skills to develop and assess curricula,” Dr. Myers said. “The program also focuses on professional development and community building.”

While education is important, Dr. Myers says that a willingness to take risks is a greater predictor of success in QI. “It’s a very experiential field where you learn by doing. What you have done, and are willing to do, is more important than the training that you’ve had. Can you lead an initiative? Do you communicate well with people and teams? Can you articulate the value equation?”

She also advises hospitalists to find multiple mentors in quality work. “We talk a lot about that at QSEA,” Dr. Myers said. “It’s important to have the perspectives of people inside and outside of your institution. That’s also where the SHM network is helpful. Mentorship is a pillar of [many activities] at the annual meeting ... and [at] programs like the Academic Hospitalist Academy and QSEA.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Jennifer Myers, director of quality and safety education at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Even as a junior physician, Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, embraced the complexities of the hospital system and the opportunity to transform patient care. She was one of the first hospitalists to participate in and lead quality improvement (QI) work at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center more than 10 years ago, where, “in that role, I got to know almost everyone in the hospital and got an up-close view of how the hospital works administratively,” she recalled.

The experience taught Dr. Myers how little she knew at that time about hospital operations, and she convinced hospital administrators that a mechanism was needed to prepare the next generation of leaders in QI and patient safety. In 2011, with the support of a career development award from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Dr. Myers formulated a quality and patient safety curriculum for residents of Penn Medicine, as well as a more basic introductory program for medical students.

“You will always do your best in work that you are passionate about,” she said, advising others to do the same when choosing their career pathways. “Find others who are interested in – or frustrated by – the same things that you are, and work with them as you begin to shape your projects. If it’s the opioid epidemic, partner with someone in the hospital with an interest in making informed prescribing decisions. If it’s working with residents in quality, find a chief resident to help you develop an educational pathway or elective.”

Dr. Myers says that hospitalists who function at the intersection of the ICU, the ER, and inpatient care are naturally suited for leadership positions in quality and patient safety, “but, if you are a hospitalist aspiring to be a chief quality or medical officer or (someone) who wants to know the field more deeply, I recommend getting advanced training.”

Hospitalists now have multiple educational opportunities in QI to choose from, but that was not the case 7 years ago when SHM leaders invited Dr. Myers to develop and lead the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA). The 2.5-day program trains medical educators to develop curricula that incorporate quality improvement and safety principles into their local institutions. “We give them the core quality and safety knowledge but also the skills to develop and assess curricula,” Dr. Myers said. “The program also focuses on professional development and community building.”

While education is important, Dr. Myers says that a willingness to take risks is a greater predictor of success in QI. “It’s a very experiential field where you learn by doing. What you have done, and are willing to do, is more important than the training that you’ve had. Can you lead an initiative? Do you communicate well with people and teams? Can you articulate the value equation?”

She also advises hospitalists to find multiple mentors in quality work. “We talk a lot about that at QSEA,” Dr. Myers said. “It’s important to have the perspectives of people inside and outside of your institution. That’s also where the SHM network is helpful. Mentorship is a pillar of [many activities] at the annual meeting ... and [at] programs like the Academic Hospitalist Academy and QSEA.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Jennifer Myers, director of quality and safety education at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Even as a junior physician, Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, embraced the complexities of the hospital system and the opportunity to transform patient care. She was one of the first hospitalists to participate in and lead quality improvement (QI) work at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center more than 10 years ago, where, “in that role, I got to know almost everyone in the hospital and got an up-close view of how the hospital works administratively,” she recalled.

The experience taught Dr. Myers how little she knew at that time about hospital operations, and she convinced hospital administrators that a mechanism was needed to prepare the next generation of leaders in QI and patient safety. In 2011, with the support of a career development award from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Dr. Myers formulated a quality and patient safety curriculum for residents of Penn Medicine, as well as a more basic introductory program for medical students.

“You will always do your best in work that you are passionate about,” she said, advising others to do the same when choosing their career pathways. “Find others who are interested in – or frustrated by – the same things that you are, and work with them as you begin to shape your projects. If it’s the opioid epidemic, partner with someone in the hospital with an interest in making informed prescribing decisions. If it’s working with residents in quality, find a chief resident to help you develop an educational pathway or elective.”

Dr. Myers says that hospitalists who function at the intersection of the ICU, the ER, and inpatient care are naturally suited for leadership positions in quality and patient safety, “but, if you are a hospitalist aspiring to be a chief quality or medical officer or (someone) who wants to know the field more deeply, I recommend getting advanced training.”

Hospitalists now have multiple educational opportunities in QI to choose from, but that was not the case 7 years ago when SHM leaders invited Dr. Myers to develop and lead the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA). The 2.5-day program trains medical educators to develop curricula that incorporate quality improvement and safety principles into their local institutions. “We give them the core quality and safety knowledge but also the skills to develop and assess curricula,” Dr. Myers said. “The program also focuses on professional development and community building.”

While education is important, Dr. Myers says that a willingness to take risks is a greater predictor of success in QI. “It’s a very experiential field where you learn by doing. What you have done, and are willing to do, is more important than the training that you’ve had. Can you lead an initiative? Do you communicate well with people and teams? Can you articulate the value equation?”

She also advises hospitalists to find multiple mentors in quality work. “We talk a lot about that at QSEA,” Dr. Myers said. “It’s important to have the perspectives of people inside and outside of your institution. That’s also where the SHM network is helpful. Mentorship is a pillar of [many activities] at the annual meeting ... and [at] programs like the Academic Hospitalist Academy and QSEA.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Corticosteroids may shorten flares of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome

SAN FRANCISCO – Oral corticosteroids appear to be beneficial in treating flares of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome, or PANS, according to Margo Thienemann, MD.

“Corticosteroids shorten the duration of flares, and if you treat patients early in their first episode, their overall course seems to be better,” said Dr. Thienemann, a child psychiatrist at Stanford (Calif.) Children’s Hospital.

She is part of a multidisciplinary Stanford PANS clinic, together with a pediatric immunologist, a pediatric rheumatologist, two nurse practitioners, a child psychologist, and a social worker, all devoted to the study and treatment of the debilitating condition.

Dr. Thienemann presented the findings of a retrospective, observational study of 98 patients at the PANS clinic who collectively had 403 disease flares. Eighty-five of the flares were treated with 102 courses of oral steroids, either in a 4- to 5-day burst or longer-duration regimens of up to 8 weeks. Dosing was weight based and averaged roughly 60 mg/day. Treatment response was assessed within 14 days after initiating short-burst therapy or at the end of a longer course.

When a child’s first episode of PANS was treated with oral steroids, the episode lasted for an average of 10.3 weeks; if untreated, the average duration was 16.5 weeks, Dr. Thienemann reported at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Improvement of neuropsychiatric symptoms began on average 3.6 days into a course of oral steroids. That improvement lasted an average of 43.9 days before the next escalation of symptoms.

Longer treatment was better: Each additional day of steroid therapy was associated with a 2.56-day increase in the duration of improvement of neuropsychiatric symptoms in a logistic regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, weeks since onset of current PANS illness, use of cognitive-behavioral therapy during flares, antibiotic therapy, and the number of psychiatric medications a patient was on.

On the other hand, each day of delay in initiating oral corticosteroids was associated with an adjusted 0.18-week longer flare duration.

No improvement in PANS symptoms occurred in patients who developed an infection within 14 days after initiating corticosteroids. Among 31 such patients, 11 had no response to steroids, and only 6 were complete responders. In contrast, among a matched group of 31 patients without infection, there was 1 nonresponder, and there were 12 complete responders.

The Stanford group now is using intravenous corticosteroids as well to treat PANS. Although the group is still collecting data and isn’t yet ready to report results, Dr. Thienemann said intravenous therapy looks very promising.

“We’re seeing a more dramatic response with IV steroids, and with [fewer] side effects,” she said. “With oral steroids, patients become more labile for a day or two, and everything gets worse for that time before things start getting better.”

PANS is a strikingly abrupt-onset disorder. It is defined by dramatic onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder over the course of less than 72 hours and/or severe eating restriction, with at least two coinciding, debilitating neuropsychiatric symptoms. These PANS-defining symptoms may include anxiety, mood dysregulation, irritability or aggression, behavioral regression, cognitive deterioration, sensorimotor abnormalities, and/or somatic symptoms.

The average age of onset of PANS is 7-9 years. The course is typically relapsing/remitting.

“The symptoms are largely psychiatric. We see huge separation anxiety. And aggression – biting, hitting, and kicking in sweet kids who suddenly go crazy,” Dr. Thienemann said in an interview. “They regress behaviorally, have foggy brain, can’t process information, and they have frequent urination and bed-wetting, even if they never did that before. And their handwriting deteriorates.

“We think it’s probably basal ganglia inflammation,” she explained. “The same way a patient might immunologically attack his joints or heart after strep infection, we think it’s brain inflammation resulting from an abnormal immune response to infection.”

This postulated etiology is supported both by PET brain imaging studies and several animal models of PANS, she added.

If the symptoms are associated with a group A streptococcal infection, the disorder is called Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated With Streptococcal Infections, or PANDAS, which was first described in 1999 and predates PANS as a defined entity.

Based on the encouraging Stanford experience, a formal double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of corticosteroid therapy in patients with PANS is warranted, Dr. Thienemann said.

Awareness of PANS as a real entity is “getting better” among general pediatricians, according to the child psychiatrist.

“I think more and more it’s no longer a question about whether this exists,” she said. “Now, it’s a matter of disseminating treatment guidelines.”

The PANDAS Physicians Network has already released diagnostic guidelines. Preliminary treatment guidelines have been developed and will soon be published separately in immunology, infectious diseases, and psychiatry/behavioral medicine journals.

Dr. Thienemann reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by Stanford University.

SAN FRANCISCO – Oral corticosteroids appear to be beneficial in treating flares of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome, or PANS, according to Margo Thienemann, MD.

“Corticosteroids shorten the duration of flares, and if you treat patients early in their first episode, their overall course seems to be better,” said Dr. Thienemann, a child psychiatrist at Stanford (Calif.) Children’s Hospital.

She is part of a multidisciplinary Stanford PANS clinic, together with a pediatric immunologist, a pediatric rheumatologist, two nurse practitioners, a child psychologist, and a social worker, all devoted to the study and treatment of the debilitating condition.

Dr. Thienemann presented the findings of a retrospective, observational study of 98 patients at the PANS clinic who collectively had 403 disease flares. Eighty-five of the flares were treated with 102 courses of oral steroids, either in a 4- to 5-day burst or longer-duration regimens of up to 8 weeks. Dosing was weight based and averaged roughly 60 mg/day. Treatment response was assessed within 14 days after initiating short-burst therapy or at the end of a longer course.