User login

Granulomatous Cheilitis Mimicking Angioedema

To the Editor:

Granulomatous cheilitis (GC), also known as Miescher cheilitis, belongs to a larger class of diseases known as orofacial granulomatoses (OFGs), a set of diseases distinguished by their clinical and pathologic features of facial edema and granulomatous inflammation.1-3 Granulomatous cheilitis, a monosymptomatic variant of a more extensive disease known as Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (MRS), presents with labial swelling mimicking angioedema. Timely diagnosis of GC and MRS reduces the number of unnecessary tests, health care costs, and unnecessary patient burden. We present a case of idiopathic persistent swelling of the upper lip that was originally misdiagnosed as angioedema.

A 13-year-old white adolescent boy was referred to the allergy-immunology clinic for an alternate opinion regarding a presumed diagnosis of angioedema. He presented with prominent persistent swelling of the upper lip of 1 year’s duration associated with fissuring and discomfort while eating, which led to weight loss of more than 4.5 kg. The patient denied any history of facial asymmetry, paralysis, dental infections, or gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Additionally, he was not on any medications. His parents reported variable symptomatic worsening associated with egg ingestion, but avoiding egg did not provide any symptomatic relief. The swelling was unresponsive to multiple and prolonged courses of antihistamines and oral glucocorticoids. The patient’s medical history revealed no similar episodes of unexplained swelling, and family history was negative for angioedema. On examination, the upper lip was tender with a firm rubbery consistency. No other areas of swelling were noted. Angular cheilosis and minor labial mucosal ulcerations also were observed (Figure).

The persistent nature of the lip swelling and findings of fissures were not consistent with angioedema. Furthermore, prior laboratory studies did not reveal evidence of hereditary or acquired angioedema, and a complete blood cell count with differential was within reference range. Although the clinical suspicion for egg allergy was low, a blood test for serum-specific IgE showed a mild reactivity to egg allergen. The patient was referred to an oral surgeon for biopsy, which revealed dermal foci of noncaseating granulomas consistent with the preliminary diagnosis of GC.

Intralesional triamcinolone injections were initiated with marked improvement. Shortly after the initial improvement, however, the symptoms recurred, which necessitated several additional intralesional triamcinolone injections, again with remarkable improvement. Approximately 1.5 years later, the patient presented with recurrence of the lip swelling and admitted to having episodic diarrhea and abdominal cramps. He was referred to a pediatric gastroenterologist and a colonoscopy with biopsy confirmed Crohn disease. He was started on azathioprine followed by infliximab. A few months after this treatment was initiated, both his lip swelling and gastrointestinal tract symptoms remarkably improved. He has been maintained on this regimen and in the most recent follow-up had no recurrence of GC. He is scheduled to have another colonoscopy.

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare chronic inflammatory condition characterized clinically by persistent lip swelling and histologically by granulomatous inflammation in the absence of systemic granulomatous disorders.4 Granulomatous cheilitis falls under the umbrella of OFGs. When it is paired with facial paralysis and fissuring of the tongue, it is specifically referred to as MRS. The prevalence of GC has historically been difficult to ascertain. In a review, an estimated incidence of 0.08% in the general population was reported with no predilection for race, sex, or age.4,5 Initially, the swelling of GC can be misdiagnosed as angioedema; therefore, it is imperative to include OFG and GC in the differential diagnosis of facial angioedema.3 Other possible diagnoses to consider include contact dermatitis, foreign-body reactions, infection, and reactions to medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.5 Chronic lymphedema and other granulomatous diseases also should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Isolated lymphedema of the head and neck, though rare, typically is seen following surgical or radiological interventions for cancer. Lymphatic fibrosis also can occur in the setting of chronic inflammatory skin conditions but is not typically the first presenting symptom, as was seen in our patient.6 Although granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis may be difficult to clinically and histologically differentiate from GC, isolated orofacial swelling in sarcoidosis is rare. If clinical suspicion for sarcoidosis does exist, however, a negative chest radiograph as well as serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels within reference range may help differentiate GC from sarcoidosis. In our patient, the clinical suspicion for sarcoidosis was low given his clinical history, young age, and race.

The etiology of MRS and GC currently is unknown. Genetic factors, food allergies, infectious processes, and aberrant immunologic functions all have been proposed as possible mechanisms.1-3,7,8 Genetic factors, such as HLA antigen subtypes, have been investigated but have not shown a definitive correlation.8 Numerous food allergens have been suggested as causative factors in OFG via a type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction,7 with cinnamon and benzoate reported as 2 of the most cited entities.9,10 Currently, it is believed that both of these mechanisms may play an exacerbating role to an otherwise unknown disease process.7,8 The infectious process most often associated with GC is Mycobacterium tuberculosis; however, similar to genetics and food allergens, causality has not been determined.4,7 At the present time, the best evidence points to an immunologic basis of GC with the inciting event being a random influx of inflammatory cells.7,11

There is a known association between GC and Crohn disease, especially when oral lesions are present.1,9 Granulomatous cheilitis can be considered an extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease.Up to 20% of OFG patients eventually go on to develop Crohn disease, with some reports being even higher when OFG presents in childhood.1,9 One study proposed that both GC and Crohn disease patients shared similar histopathologic and immunopathologic features including a helper T cell (TH1)–predominant inflammatory reaction.11

The treatment of GC is challenging, with most evidence coming from sporadic case reports. Given the relatively high rate of cinnamon and benzoate hypersensitivity seen in GC patients, it has been postulated that a diet lacking in them will improve the disease. At least one study has reported positive clinical outcomes from diets lacking in cinnamon and benzoate and in fact recommended it as a potential first-line treatment.10 The mainstay of treatment, however, is corticosteroids, but continued use is discouraged due to their large side-effect profile.12 Currently, the most agreed upon treatment for patients with isolated GC is intralesional triamcinolone injections.12 Despite the robust initial response often seen with triamcinolone injections, it is not uncommon for the benefit to be short-lived, requiring additional treatments.1,5,12 Newer medical therapies that have shown promise largely are centered on anti–tumor necrosis factor α medications such as infliximab and adalimumab.13,14 It is postulated that due to the potential overlapping pathophysiology between Crohn disease and GC, there may be utility in using the same treatments.13 In situations where medical therapy fails or in extremely disfiguring cases of GC and MRS, surgical cheiloplasty is performed to reduce lip size and improve cosmetic appearance.12 In a small study, reduction cheiloplasty gave satisfactory functional and cosmetic outcomes in all 7 patients reviewed at a median follow-up of 6.5 years.15

This case emphasizes the importance of paying close attention to history and physical examination features in developing any differential diagnosis. In this patient, persistent orofacial swelling with associated mucosal ulcerations were sufficient to exclude drug-induced, idiopathic, hereditary, and acquired angioedema. The clinical history coupled with the biopsy results yielded a confident diagnosis of GC. Furthermore, similar presentations should raise concern for a subclinical inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn disease.

- Rose AE, Leger M, Chu J, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:15.

- Vibhute NA, Vibhute AH, Nilima DR. Cheilitis granulomatosa: a case report with review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:242.

- Kakimoto C, Sparks C, White AA. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome: a form of pseudoangioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:185-189.

- McCartan BE, Healy CM, McCreary CE, et al. Characteristics of patients with orofacial granulomatosis. Oral Dis. 2011;17:696-704.

- Critchlow WA, Chang D. Cheilitis granulomatosa: a review [published online September 22, 2013]. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:209-213.

- Withey S, Pracy P, Vaz F, et al. Sensory deprivation as a consequence of severe head and neck lymphoedema. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:62-64.

- Grave B, McCullough M, Wiesenfeld D. Orofacial granulomatosis—a 20-year review. Oral Dis. 2009;15:46-51.

- Gibson J, Wray D. Human leucocyte antigen typing in orofacial. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1119-1121.

- Campbell H, Escudier M, Patel P, et al. Distinguishing orofacial granulomatosis from Crohn’s disease: two separate disease entities? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2109-2115.

- White A, Nunes C, Escudier M, et al. Improvement in orofacial granulomatosis on a cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:508-514.

- Freysdottir J, Zhang S, Tilakaratne WM, et al. Oral biopsies from patients with orofacial granulomatosis with histology resembling Crohn’s disease have a prominent Th1 environment. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:439-445.

- Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:934-937.

- Peitsch WK, Kemmler N, Goerdt S, et al. Infliximab: a novel treatment option for refractory orofacial granulomatosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:265-266.

- Ruiz Villaverde R, Sánchez Cano D. Successful treatment of granulomatous cheilitis with adalimumab. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:118-120.

- Kruse-Lösler B, Presser D, Metze D, et al. Surgical treatment of persistent macrocheilia in patients with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and cheilitis granulomatosa. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1085-1091.

To the Editor:

Granulomatous cheilitis (GC), also known as Miescher cheilitis, belongs to a larger class of diseases known as orofacial granulomatoses (OFGs), a set of diseases distinguished by their clinical and pathologic features of facial edema and granulomatous inflammation.1-3 Granulomatous cheilitis, a monosymptomatic variant of a more extensive disease known as Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (MRS), presents with labial swelling mimicking angioedema. Timely diagnosis of GC and MRS reduces the number of unnecessary tests, health care costs, and unnecessary patient burden. We present a case of idiopathic persistent swelling of the upper lip that was originally misdiagnosed as angioedema.

A 13-year-old white adolescent boy was referred to the allergy-immunology clinic for an alternate opinion regarding a presumed diagnosis of angioedema. He presented with prominent persistent swelling of the upper lip of 1 year’s duration associated with fissuring and discomfort while eating, which led to weight loss of more than 4.5 kg. The patient denied any history of facial asymmetry, paralysis, dental infections, or gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Additionally, he was not on any medications. His parents reported variable symptomatic worsening associated with egg ingestion, but avoiding egg did not provide any symptomatic relief. The swelling was unresponsive to multiple and prolonged courses of antihistamines and oral glucocorticoids. The patient’s medical history revealed no similar episodes of unexplained swelling, and family history was negative for angioedema. On examination, the upper lip was tender with a firm rubbery consistency. No other areas of swelling were noted. Angular cheilosis and minor labial mucosal ulcerations also were observed (Figure).

The persistent nature of the lip swelling and findings of fissures were not consistent with angioedema. Furthermore, prior laboratory studies did not reveal evidence of hereditary or acquired angioedema, and a complete blood cell count with differential was within reference range. Although the clinical suspicion for egg allergy was low, a blood test for serum-specific IgE showed a mild reactivity to egg allergen. The patient was referred to an oral surgeon for biopsy, which revealed dermal foci of noncaseating granulomas consistent with the preliminary diagnosis of GC.

Intralesional triamcinolone injections were initiated with marked improvement. Shortly after the initial improvement, however, the symptoms recurred, which necessitated several additional intralesional triamcinolone injections, again with remarkable improvement. Approximately 1.5 years later, the patient presented with recurrence of the lip swelling and admitted to having episodic diarrhea and abdominal cramps. He was referred to a pediatric gastroenterologist and a colonoscopy with biopsy confirmed Crohn disease. He was started on azathioprine followed by infliximab. A few months after this treatment was initiated, both his lip swelling and gastrointestinal tract symptoms remarkably improved. He has been maintained on this regimen and in the most recent follow-up had no recurrence of GC. He is scheduled to have another colonoscopy.

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare chronic inflammatory condition characterized clinically by persistent lip swelling and histologically by granulomatous inflammation in the absence of systemic granulomatous disorders.4 Granulomatous cheilitis falls under the umbrella of OFGs. When it is paired with facial paralysis and fissuring of the tongue, it is specifically referred to as MRS. The prevalence of GC has historically been difficult to ascertain. In a review, an estimated incidence of 0.08% in the general population was reported with no predilection for race, sex, or age.4,5 Initially, the swelling of GC can be misdiagnosed as angioedema; therefore, it is imperative to include OFG and GC in the differential diagnosis of facial angioedema.3 Other possible diagnoses to consider include contact dermatitis, foreign-body reactions, infection, and reactions to medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.5 Chronic lymphedema and other granulomatous diseases also should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Isolated lymphedema of the head and neck, though rare, typically is seen following surgical or radiological interventions for cancer. Lymphatic fibrosis also can occur in the setting of chronic inflammatory skin conditions but is not typically the first presenting symptom, as was seen in our patient.6 Although granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis may be difficult to clinically and histologically differentiate from GC, isolated orofacial swelling in sarcoidosis is rare. If clinical suspicion for sarcoidosis does exist, however, a negative chest radiograph as well as serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels within reference range may help differentiate GC from sarcoidosis. In our patient, the clinical suspicion for sarcoidosis was low given his clinical history, young age, and race.

The etiology of MRS and GC currently is unknown. Genetic factors, food allergies, infectious processes, and aberrant immunologic functions all have been proposed as possible mechanisms.1-3,7,8 Genetic factors, such as HLA antigen subtypes, have been investigated but have not shown a definitive correlation.8 Numerous food allergens have been suggested as causative factors in OFG via a type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction,7 with cinnamon and benzoate reported as 2 of the most cited entities.9,10 Currently, it is believed that both of these mechanisms may play an exacerbating role to an otherwise unknown disease process.7,8 The infectious process most often associated with GC is Mycobacterium tuberculosis; however, similar to genetics and food allergens, causality has not been determined.4,7 At the present time, the best evidence points to an immunologic basis of GC with the inciting event being a random influx of inflammatory cells.7,11

There is a known association between GC and Crohn disease, especially when oral lesions are present.1,9 Granulomatous cheilitis can be considered an extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease.Up to 20% of OFG patients eventually go on to develop Crohn disease, with some reports being even higher when OFG presents in childhood.1,9 One study proposed that both GC and Crohn disease patients shared similar histopathologic and immunopathologic features including a helper T cell (TH1)–predominant inflammatory reaction.11

The treatment of GC is challenging, with most evidence coming from sporadic case reports. Given the relatively high rate of cinnamon and benzoate hypersensitivity seen in GC patients, it has been postulated that a diet lacking in them will improve the disease. At least one study has reported positive clinical outcomes from diets lacking in cinnamon and benzoate and in fact recommended it as a potential first-line treatment.10 The mainstay of treatment, however, is corticosteroids, but continued use is discouraged due to their large side-effect profile.12 Currently, the most agreed upon treatment for patients with isolated GC is intralesional triamcinolone injections.12 Despite the robust initial response often seen with triamcinolone injections, it is not uncommon for the benefit to be short-lived, requiring additional treatments.1,5,12 Newer medical therapies that have shown promise largely are centered on anti–tumor necrosis factor α medications such as infliximab and adalimumab.13,14 It is postulated that due to the potential overlapping pathophysiology between Crohn disease and GC, there may be utility in using the same treatments.13 In situations where medical therapy fails or in extremely disfiguring cases of GC and MRS, surgical cheiloplasty is performed to reduce lip size and improve cosmetic appearance.12 In a small study, reduction cheiloplasty gave satisfactory functional and cosmetic outcomes in all 7 patients reviewed at a median follow-up of 6.5 years.15

This case emphasizes the importance of paying close attention to history and physical examination features in developing any differential diagnosis. In this patient, persistent orofacial swelling with associated mucosal ulcerations were sufficient to exclude drug-induced, idiopathic, hereditary, and acquired angioedema. The clinical history coupled with the biopsy results yielded a confident diagnosis of GC. Furthermore, similar presentations should raise concern for a subclinical inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn disease.

To the Editor:

Granulomatous cheilitis (GC), also known as Miescher cheilitis, belongs to a larger class of diseases known as orofacial granulomatoses (OFGs), a set of diseases distinguished by their clinical and pathologic features of facial edema and granulomatous inflammation.1-3 Granulomatous cheilitis, a monosymptomatic variant of a more extensive disease known as Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (MRS), presents with labial swelling mimicking angioedema. Timely diagnosis of GC and MRS reduces the number of unnecessary tests, health care costs, and unnecessary patient burden. We present a case of idiopathic persistent swelling of the upper lip that was originally misdiagnosed as angioedema.

A 13-year-old white adolescent boy was referred to the allergy-immunology clinic for an alternate opinion regarding a presumed diagnosis of angioedema. He presented with prominent persistent swelling of the upper lip of 1 year’s duration associated with fissuring and discomfort while eating, which led to weight loss of more than 4.5 kg. The patient denied any history of facial asymmetry, paralysis, dental infections, or gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Additionally, he was not on any medications. His parents reported variable symptomatic worsening associated with egg ingestion, but avoiding egg did not provide any symptomatic relief. The swelling was unresponsive to multiple and prolonged courses of antihistamines and oral glucocorticoids. The patient’s medical history revealed no similar episodes of unexplained swelling, and family history was negative for angioedema. On examination, the upper lip was tender with a firm rubbery consistency. No other areas of swelling were noted. Angular cheilosis and minor labial mucosal ulcerations also were observed (Figure).

The persistent nature of the lip swelling and findings of fissures were not consistent with angioedema. Furthermore, prior laboratory studies did not reveal evidence of hereditary or acquired angioedema, and a complete blood cell count with differential was within reference range. Although the clinical suspicion for egg allergy was low, a blood test for serum-specific IgE showed a mild reactivity to egg allergen. The patient was referred to an oral surgeon for biopsy, which revealed dermal foci of noncaseating granulomas consistent with the preliminary diagnosis of GC.

Intralesional triamcinolone injections were initiated with marked improvement. Shortly after the initial improvement, however, the symptoms recurred, which necessitated several additional intralesional triamcinolone injections, again with remarkable improvement. Approximately 1.5 years later, the patient presented with recurrence of the lip swelling and admitted to having episodic diarrhea and abdominal cramps. He was referred to a pediatric gastroenterologist and a colonoscopy with biopsy confirmed Crohn disease. He was started on azathioprine followed by infliximab. A few months after this treatment was initiated, both his lip swelling and gastrointestinal tract symptoms remarkably improved. He has been maintained on this regimen and in the most recent follow-up had no recurrence of GC. He is scheduled to have another colonoscopy.

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare chronic inflammatory condition characterized clinically by persistent lip swelling and histologically by granulomatous inflammation in the absence of systemic granulomatous disorders.4 Granulomatous cheilitis falls under the umbrella of OFGs. When it is paired with facial paralysis and fissuring of the tongue, it is specifically referred to as MRS. The prevalence of GC has historically been difficult to ascertain. In a review, an estimated incidence of 0.08% in the general population was reported with no predilection for race, sex, or age.4,5 Initially, the swelling of GC can be misdiagnosed as angioedema; therefore, it is imperative to include OFG and GC in the differential diagnosis of facial angioedema.3 Other possible diagnoses to consider include contact dermatitis, foreign-body reactions, infection, and reactions to medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.5 Chronic lymphedema and other granulomatous diseases also should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Isolated lymphedema of the head and neck, though rare, typically is seen following surgical or radiological interventions for cancer. Lymphatic fibrosis also can occur in the setting of chronic inflammatory skin conditions but is not typically the first presenting symptom, as was seen in our patient.6 Although granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis may be difficult to clinically and histologically differentiate from GC, isolated orofacial swelling in sarcoidosis is rare. If clinical suspicion for sarcoidosis does exist, however, a negative chest radiograph as well as serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels within reference range may help differentiate GC from sarcoidosis. In our patient, the clinical suspicion for sarcoidosis was low given his clinical history, young age, and race.

The etiology of MRS and GC currently is unknown. Genetic factors, food allergies, infectious processes, and aberrant immunologic functions all have been proposed as possible mechanisms.1-3,7,8 Genetic factors, such as HLA antigen subtypes, have been investigated but have not shown a definitive correlation.8 Numerous food allergens have been suggested as causative factors in OFG via a type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction,7 with cinnamon and benzoate reported as 2 of the most cited entities.9,10 Currently, it is believed that both of these mechanisms may play an exacerbating role to an otherwise unknown disease process.7,8 The infectious process most often associated with GC is Mycobacterium tuberculosis; however, similar to genetics and food allergens, causality has not been determined.4,7 At the present time, the best evidence points to an immunologic basis of GC with the inciting event being a random influx of inflammatory cells.7,11

There is a known association between GC and Crohn disease, especially when oral lesions are present.1,9 Granulomatous cheilitis can be considered an extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease.Up to 20% of OFG patients eventually go on to develop Crohn disease, with some reports being even higher when OFG presents in childhood.1,9 One study proposed that both GC and Crohn disease patients shared similar histopathologic and immunopathologic features including a helper T cell (TH1)–predominant inflammatory reaction.11

The treatment of GC is challenging, with most evidence coming from sporadic case reports. Given the relatively high rate of cinnamon and benzoate hypersensitivity seen in GC patients, it has been postulated that a diet lacking in them will improve the disease. At least one study has reported positive clinical outcomes from diets lacking in cinnamon and benzoate and in fact recommended it as a potential first-line treatment.10 The mainstay of treatment, however, is corticosteroids, but continued use is discouraged due to their large side-effect profile.12 Currently, the most agreed upon treatment for patients with isolated GC is intralesional triamcinolone injections.12 Despite the robust initial response often seen with triamcinolone injections, it is not uncommon for the benefit to be short-lived, requiring additional treatments.1,5,12 Newer medical therapies that have shown promise largely are centered on anti–tumor necrosis factor α medications such as infliximab and adalimumab.13,14 It is postulated that due to the potential overlapping pathophysiology between Crohn disease and GC, there may be utility in using the same treatments.13 In situations where medical therapy fails or in extremely disfiguring cases of GC and MRS, surgical cheiloplasty is performed to reduce lip size and improve cosmetic appearance.12 In a small study, reduction cheiloplasty gave satisfactory functional and cosmetic outcomes in all 7 patients reviewed at a median follow-up of 6.5 years.15

This case emphasizes the importance of paying close attention to history and physical examination features in developing any differential diagnosis. In this patient, persistent orofacial swelling with associated mucosal ulcerations were sufficient to exclude drug-induced, idiopathic, hereditary, and acquired angioedema. The clinical history coupled with the biopsy results yielded a confident diagnosis of GC. Furthermore, similar presentations should raise concern for a subclinical inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn disease.

- Rose AE, Leger M, Chu J, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:15.

- Vibhute NA, Vibhute AH, Nilima DR. Cheilitis granulomatosa: a case report with review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:242.

- Kakimoto C, Sparks C, White AA. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome: a form of pseudoangioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:185-189.

- McCartan BE, Healy CM, McCreary CE, et al. Characteristics of patients with orofacial granulomatosis. Oral Dis. 2011;17:696-704.

- Critchlow WA, Chang D. Cheilitis granulomatosa: a review [published online September 22, 2013]. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:209-213.

- Withey S, Pracy P, Vaz F, et al. Sensory deprivation as a consequence of severe head and neck lymphoedema. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:62-64.

- Grave B, McCullough M, Wiesenfeld D. Orofacial granulomatosis—a 20-year review. Oral Dis. 2009;15:46-51.

- Gibson J, Wray D. Human leucocyte antigen typing in orofacial. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1119-1121.

- Campbell H, Escudier M, Patel P, et al. Distinguishing orofacial granulomatosis from Crohn’s disease: two separate disease entities? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2109-2115.

- White A, Nunes C, Escudier M, et al. Improvement in orofacial granulomatosis on a cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:508-514.

- Freysdottir J, Zhang S, Tilakaratne WM, et al. Oral biopsies from patients with orofacial granulomatosis with histology resembling Crohn’s disease have a prominent Th1 environment. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:439-445.

- Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:934-937.

- Peitsch WK, Kemmler N, Goerdt S, et al. Infliximab: a novel treatment option for refractory orofacial granulomatosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:265-266.

- Ruiz Villaverde R, Sánchez Cano D. Successful treatment of granulomatous cheilitis with adalimumab. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:118-120.

- Kruse-Lösler B, Presser D, Metze D, et al. Surgical treatment of persistent macrocheilia in patients with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and cheilitis granulomatosa. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1085-1091.

- Rose AE, Leger M, Chu J, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:15.

- Vibhute NA, Vibhute AH, Nilima DR. Cheilitis granulomatosa: a case report with review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:242.

- Kakimoto C, Sparks C, White AA. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome: a form of pseudoangioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:185-189.

- McCartan BE, Healy CM, McCreary CE, et al. Characteristics of patients with orofacial granulomatosis. Oral Dis. 2011;17:696-704.

- Critchlow WA, Chang D. Cheilitis granulomatosa: a review [published online September 22, 2013]. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:209-213.

- Withey S, Pracy P, Vaz F, et al. Sensory deprivation as a consequence of severe head and neck lymphoedema. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:62-64.

- Grave B, McCullough M, Wiesenfeld D. Orofacial granulomatosis—a 20-year review. Oral Dis. 2009;15:46-51.

- Gibson J, Wray D. Human leucocyte antigen typing in orofacial. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1119-1121.

- Campbell H, Escudier M, Patel P, et al. Distinguishing orofacial granulomatosis from Crohn’s disease: two separate disease entities? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2109-2115.

- White A, Nunes C, Escudier M, et al. Improvement in orofacial granulomatosis on a cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:508-514.

- Freysdottir J, Zhang S, Tilakaratne WM, et al. Oral biopsies from patients with orofacial granulomatosis with histology resembling Crohn’s disease have a prominent Th1 environment. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:439-445.

- Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:934-937.

- Peitsch WK, Kemmler N, Goerdt S, et al. Infliximab: a novel treatment option for refractory orofacial granulomatosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:265-266.

- Ruiz Villaverde R, Sánchez Cano D. Successful treatment of granulomatous cheilitis with adalimumab. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:118-120.

- Kruse-Lösler B, Presser D, Metze D, et al. Surgical treatment of persistent macrocheilia in patients with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and cheilitis granulomatosa. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1085-1091.

Practice Points

- Granulomatous cheilitis (GC) is a rare diagnosis that can present as an isolated disease or in association with another disease, most commonly an inflammatory bowel disease (ie, Crohn disease).

- Often misdiagnosed as angioedema, GC can be differentiated primarily based on history and clinical examination.

- Intervention such as intralesional steroid injection is effective in the primary form; however, treatment of the underlying condition, such as Crohn disease, is needed when the 2 conditions are associated.

Sneak Peek: The Hospital Leader Blog

We go to the altar together.

Last month, I wrote about onboarding and the important responsibility that everyone associated with a hospitalist program has to ensure that each new provider quickly comes to believe he or she made a terrific choice to join the group.

Upon reflection, it seems important to address the other side of this equation. I’m talking about the responsibilities that each candidate has when deciding whether to apply for a job, to interview, and to accept or reject a group’s offer.

The relationship between a hospitalist and the group he or she is part of is a lot like a marriage. Both parties go to the altar together, and the relationship is most likely to be successful when both enter it with their eyes open, having done their due diligence, and with an intention to align their interests and support each other. Here are some things every hospitalist should be thinking about as they assess potential job opportunities:

1. Be clear about your own needs, goals, and priorities. Before you embark on the job-hunting process, take time to do some careful introspection. My partner John Nelson is fond of saying that one of the key reasons many doctors choose to become hospitalists is that they prefer to “date” their practice rather than “marry” it. Which do you want? Are you willing to accept both the benefits and the costs of your preference? What are your short- and long-term career goals? In what part of the country do you want to live, and are you looking for an urban, suburban, or small-town environment? Is it important to be in a teaching setting? Are there specific pieces of work, such as ICU care or procedures, that you want to either pursue or avoid? What personal considerations, such as the needs of your spouse or kids, might limit your options? What structural aspects of the job are most important to you? Schedule? Daily workload? Compensation? I encourage you to think through these and other similar questions so that you are clear in your own mind about your personal job selection criteria. This will enable you to honestly articulate these things to others and to assess potential job opportunities in light of them.

Read the full text of this blog post at hospitalleader.org.

Leslie Flores is a founding partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a consulting practice that has specialized in helping clients enhance the effectiveness and value of hospital medicine programs.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

Don’t Compare HM Group Part B Costs Hospital to Hospital by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

Overcoming a Continued Physician Shortage by Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM

Is Patient-Centered Care Bad for Resident Education? by Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM

We go to the altar together.

Last month, I wrote about onboarding and the important responsibility that everyone associated with a hospitalist program has to ensure that each new provider quickly comes to believe he or she made a terrific choice to join the group.

Upon reflection, it seems important to address the other side of this equation. I’m talking about the responsibilities that each candidate has when deciding whether to apply for a job, to interview, and to accept or reject a group’s offer.

The relationship between a hospitalist and the group he or she is part of is a lot like a marriage. Both parties go to the altar together, and the relationship is most likely to be successful when both enter it with their eyes open, having done their due diligence, and with an intention to align their interests and support each other. Here are some things every hospitalist should be thinking about as they assess potential job opportunities:

1. Be clear about your own needs, goals, and priorities. Before you embark on the job-hunting process, take time to do some careful introspection. My partner John Nelson is fond of saying that one of the key reasons many doctors choose to become hospitalists is that they prefer to “date” their practice rather than “marry” it. Which do you want? Are you willing to accept both the benefits and the costs of your preference? What are your short- and long-term career goals? In what part of the country do you want to live, and are you looking for an urban, suburban, or small-town environment? Is it important to be in a teaching setting? Are there specific pieces of work, such as ICU care or procedures, that you want to either pursue or avoid? What personal considerations, such as the needs of your spouse or kids, might limit your options? What structural aspects of the job are most important to you? Schedule? Daily workload? Compensation? I encourage you to think through these and other similar questions so that you are clear in your own mind about your personal job selection criteria. This will enable you to honestly articulate these things to others and to assess potential job opportunities in light of them.

Read the full text of this blog post at hospitalleader.org.

Leslie Flores is a founding partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a consulting practice that has specialized in helping clients enhance the effectiveness and value of hospital medicine programs.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

Don’t Compare HM Group Part B Costs Hospital to Hospital by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

Overcoming a Continued Physician Shortage by Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM

Is Patient-Centered Care Bad for Resident Education? by Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM

We go to the altar together.

Last month, I wrote about onboarding and the important responsibility that everyone associated with a hospitalist program has to ensure that each new provider quickly comes to believe he or she made a terrific choice to join the group.

Upon reflection, it seems important to address the other side of this equation. I’m talking about the responsibilities that each candidate has when deciding whether to apply for a job, to interview, and to accept or reject a group’s offer.

The relationship between a hospitalist and the group he or she is part of is a lot like a marriage. Both parties go to the altar together, and the relationship is most likely to be successful when both enter it with their eyes open, having done their due diligence, and with an intention to align their interests and support each other. Here are some things every hospitalist should be thinking about as they assess potential job opportunities:

1. Be clear about your own needs, goals, and priorities. Before you embark on the job-hunting process, take time to do some careful introspection. My partner John Nelson is fond of saying that one of the key reasons many doctors choose to become hospitalists is that they prefer to “date” their practice rather than “marry” it. Which do you want? Are you willing to accept both the benefits and the costs of your preference? What are your short- and long-term career goals? In what part of the country do you want to live, and are you looking for an urban, suburban, or small-town environment? Is it important to be in a teaching setting? Are there specific pieces of work, such as ICU care or procedures, that you want to either pursue or avoid? What personal considerations, such as the needs of your spouse or kids, might limit your options? What structural aspects of the job are most important to you? Schedule? Daily workload? Compensation? I encourage you to think through these and other similar questions so that you are clear in your own mind about your personal job selection criteria. This will enable you to honestly articulate these things to others and to assess potential job opportunities in light of them.

Read the full text of this blog post at hospitalleader.org.

Leslie Flores is a founding partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a consulting practice that has specialized in helping clients enhance the effectiveness and value of hospital medicine programs.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

Don’t Compare HM Group Part B Costs Hospital to Hospital by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

Overcoming a Continued Physician Shortage by Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM

Is Patient-Centered Care Bad for Resident Education? by Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM

Rucaparib – second PARP inhibitor hits the market for ovarian cancer

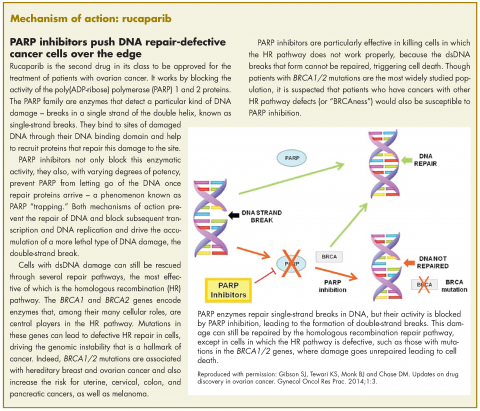

Rucaparib was granted accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with BRCA1/2 mutant advanced ovarian cancer in January this year, making it the second drug in its class for this indication. It is a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor that works by blocking the repair of damaged DNA in cancer cells and triggering cell death.

The approval was based on findings from 2 single-arm clinical trials in which rucaparib led to complete or partial tumor shrinkage in more than half of the patients enrolled. A pooled analysis included 106 patients from the phase 2 trials, Study 10 (NCT01482715; N = 42) and ARIEL2 (NCT01891344; N = 64), in which patients with BRCA1/2 mutation-positive ovarian cancer who had progressed on 2 or more previous chemotherapy regimens, received 600 mg rucaparib twice daily.

Study 10 included only patients with platinum-sensitive disease and eligible patients were aged 18 years or older, with a known deleterious BRCA mutation, evidence of measurable disease as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1), sufficient archival tumor tissue, histologically confirmed high-grade epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer and relapsed disease confirmed by radiologic assessment. Meanwhile, ARIEL2 had similar eligibility criteria, except that patients with platinum-sensitive, resistant, and refractory disease were included.

Both studies excluded patients with active second malignancies, and for those with a history of prior cancer that had been curatively treated, no evidence of current disease was required and chemotherapy should have been completed more than 6 months or bone marrow transplant more than 2 years before the first dose of rucaparib. Patients who had previously been treated with a PARP inhibitor, with symptomatic and/or untreated central nervous system metastases, or who had been hospitalized for bowel obstruction within the previous 3 months, were also ineligible.

Across the 2 trials, the median age of trial participants was 59 years, 78% were white, and all had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 (fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction) or 1 (restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature). Both trials used a surrogate endpoint for approval, measuring the percentage of patients who experienced complete or partial tumor shrinkage, the overall response rate (ORR), while taking rucaparib.

In Study 10, the ORR was 60%, including a complete response (CR) rate of 10% and a partial response (PR) rate of 50%, over a median duration of response (DoR) of 7.9 months, while in ARIEL2, the ORR was 50%, including a CR of 8% and a PR of 42%, over a median DoR of 11.6 months. The pooled analysis demonstrated an ORR of 54%, CR of 9% and PR of 45%, over a median DoR of 9.2 months. In separate data reported in the prescribing information, the ORR as assessed by independent radiology review was 42%, with a median DoR of 6.7 months, while ORR according to investigator assessment was 66%. In all analyses, the response rate was similar for patients having BRCA1 versus BRCA2 gene mutations.

Safety analyses were performed in 377 patients across the 2 studies who received 600 mg rucaparib twice daily. The most common adverse events (AEs) of any grade included nausea, fatigue, vomiting, anemia, abdominal pain, dysgeusia, constipation, decreased appetite, diarrhea, thrombocytopenia, and dyspnea. The most common serious AEs (grade 3 or 4) were anemia (25%), fatigue/asthenia (11%), and increased alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase levels (11%). Overall, 8% of patients discontinued treatment because of AEs.

The recommended dose according to the prescribing information is 600 mg, in the form of two 300-mg tablets taken orally twice daily with or without food. Phy

If hematologic toxicities occur while taking rucaparib, treatment should be interrupted and blood counts monitored until recovery and failure to recover to grade 1 or higher after 4 weeks should prompt referral to a hematologist for further investigation, while confirmed diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia should lead to discontinuation of rucaparib. Pregnant women and those of reproductive potential should be advised of the potential risk to a fetus or the need for effective contraception during treatment and for 6 months after the last dose of rucaparib.

Rucaparib is indicated only for the treatment of patients with confirmed BRCA1/2 mutations, so the drug was approved in conjunction with a companion diagnostic. FoundationFocus CDxBRCA is the first next-generation sequencing-based test to receive FDA approval and detects the presence of deleterious BRCA gene mutations in tumor tissue samples. Rucaparib is marketed as Rubraca by Clovis Oncology Inc, and the companion diagnostic by Foundation Medicine Inc.

1. Rubraca (rucaparib) capsules, for oral use. Prescribing information. Clovis Oncology Inc. http://clovisoncology.com/files/rubraca-prescribing-info.pdf. Released December 2016. Accessed January 8th, 2017.

2. FDA grants accelerated approval to new treatment for advanced ovarian cancer. FDA News Release. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm533873.htm. Last updated December 19, 2016. Accessed January 8, 2017.

3. [No author listed.] Rucaparib approved for ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. Epub ahead of print. January 5, 2017. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290. CD-NB2016-164.

Rucaparib was granted accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with BRCA1/2 mutant advanced ovarian cancer in January this year, making it the second drug in its class for this indication. It is a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor that works by blocking the repair of damaged DNA in cancer cells and triggering cell death.

The approval was based on findings from 2 single-arm clinical trials in which rucaparib led to complete or partial tumor shrinkage in more than half of the patients enrolled. A pooled analysis included 106 patients from the phase 2 trials, Study 10 (NCT01482715; N = 42) and ARIEL2 (NCT01891344; N = 64), in which patients with BRCA1/2 mutation-positive ovarian cancer who had progressed on 2 or more previous chemotherapy regimens, received 600 mg rucaparib twice daily.

Study 10 included only patients with platinum-sensitive disease and eligible patients were aged 18 years or older, with a known deleterious BRCA mutation, evidence of measurable disease as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1), sufficient archival tumor tissue, histologically confirmed high-grade epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer and relapsed disease confirmed by radiologic assessment. Meanwhile, ARIEL2 had similar eligibility criteria, except that patients with platinum-sensitive, resistant, and refractory disease were included.

Both studies excluded patients with active second malignancies, and for those with a history of prior cancer that had been curatively treated, no evidence of current disease was required and chemotherapy should have been completed more than 6 months or bone marrow transplant more than 2 years before the first dose of rucaparib. Patients who had previously been treated with a PARP inhibitor, with symptomatic and/or untreated central nervous system metastases, or who had been hospitalized for bowel obstruction within the previous 3 months, were also ineligible.

Across the 2 trials, the median age of trial participants was 59 years, 78% were white, and all had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 (fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction) or 1 (restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature). Both trials used a surrogate endpoint for approval, measuring the percentage of patients who experienced complete or partial tumor shrinkage, the overall response rate (ORR), while taking rucaparib.

In Study 10, the ORR was 60%, including a complete response (CR) rate of 10% and a partial response (PR) rate of 50%, over a median duration of response (DoR) of 7.9 months, while in ARIEL2, the ORR was 50%, including a CR of 8% and a PR of 42%, over a median DoR of 11.6 months. The pooled analysis demonstrated an ORR of 54%, CR of 9% and PR of 45%, over a median DoR of 9.2 months. In separate data reported in the prescribing information, the ORR as assessed by independent radiology review was 42%, with a median DoR of 6.7 months, while ORR according to investigator assessment was 66%. In all analyses, the response rate was similar for patients having BRCA1 versus BRCA2 gene mutations.

Safety analyses were performed in 377 patients across the 2 studies who received 600 mg rucaparib twice daily. The most common adverse events (AEs) of any grade included nausea, fatigue, vomiting, anemia, abdominal pain, dysgeusia, constipation, decreased appetite, diarrhea, thrombocytopenia, and dyspnea. The most common serious AEs (grade 3 or 4) were anemia (25%), fatigue/asthenia (11%), and increased alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase levels (11%). Overall, 8% of patients discontinued treatment because of AEs.

The recommended dose according to the prescribing information is 600 mg, in the form of two 300-mg tablets taken orally twice daily with or without food. Phy

If hematologic toxicities occur while taking rucaparib, treatment should be interrupted and blood counts monitored until recovery and failure to recover to grade 1 or higher after 4 weeks should prompt referral to a hematologist for further investigation, while confirmed diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia should lead to discontinuation of rucaparib. Pregnant women and those of reproductive potential should be advised of the potential risk to a fetus or the need for effective contraception during treatment and for 6 months after the last dose of rucaparib.

Rucaparib is indicated only for the treatment of patients with confirmed BRCA1/2 mutations, so the drug was approved in conjunction with a companion diagnostic. FoundationFocus CDxBRCA is the first next-generation sequencing-based test to receive FDA approval and detects the presence of deleterious BRCA gene mutations in tumor tissue samples. Rucaparib is marketed as Rubraca by Clovis Oncology Inc, and the companion diagnostic by Foundation Medicine Inc.

Rucaparib was granted accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with BRCA1/2 mutant advanced ovarian cancer in January this year, making it the second drug in its class for this indication. It is a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor that works by blocking the repair of damaged DNA in cancer cells and triggering cell death.

The approval was based on findings from 2 single-arm clinical trials in which rucaparib led to complete or partial tumor shrinkage in more than half of the patients enrolled. A pooled analysis included 106 patients from the phase 2 trials, Study 10 (NCT01482715; N = 42) and ARIEL2 (NCT01891344; N = 64), in which patients with BRCA1/2 mutation-positive ovarian cancer who had progressed on 2 or more previous chemotherapy regimens, received 600 mg rucaparib twice daily.

Study 10 included only patients with platinum-sensitive disease and eligible patients were aged 18 years or older, with a known deleterious BRCA mutation, evidence of measurable disease as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1), sufficient archival tumor tissue, histologically confirmed high-grade epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer and relapsed disease confirmed by radiologic assessment. Meanwhile, ARIEL2 had similar eligibility criteria, except that patients with platinum-sensitive, resistant, and refractory disease were included.

Both studies excluded patients with active second malignancies, and for those with a history of prior cancer that had been curatively treated, no evidence of current disease was required and chemotherapy should have been completed more than 6 months or bone marrow transplant more than 2 years before the first dose of rucaparib. Patients who had previously been treated with a PARP inhibitor, with symptomatic and/or untreated central nervous system metastases, or who had been hospitalized for bowel obstruction within the previous 3 months, were also ineligible.

Across the 2 trials, the median age of trial participants was 59 years, 78% were white, and all had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 (fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction) or 1 (restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature). Both trials used a surrogate endpoint for approval, measuring the percentage of patients who experienced complete or partial tumor shrinkage, the overall response rate (ORR), while taking rucaparib.

In Study 10, the ORR was 60%, including a complete response (CR) rate of 10% and a partial response (PR) rate of 50%, over a median duration of response (DoR) of 7.9 months, while in ARIEL2, the ORR was 50%, including a CR of 8% and a PR of 42%, over a median DoR of 11.6 months. The pooled analysis demonstrated an ORR of 54%, CR of 9% and PR of 45%, over a median DoR of 9.2 months. In separate data reported in the prescribing information, the ORR as assessed by independent radiology review was 42%, with a median DoR of 6.7 months, while ORR according to investigator assessment was 66%. In all analyses, the response rate was similar for patients having BRCA1 versus BRCA2 gene mutations.

Safety analyses were performed in 377 patients across the 2 studies who received 600 mg rucaparib twice daily. The most common adverse events (AEs) of any grade included nausea, fatigue, vomiting, anemia, abdominal pain, dysgeusia, constipation, decreased appetite, diarrhea, thrombocytopenia, and dyspnea. The most common serious AEs (grade 3 or 4) were anemia (25%), fatigue/asthenia (11%), and increased alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase levels (11%). Overall, 8% of patients discontinued treatment because of AEs.

The recommended dose according to the prescribing information is 600 mg, in the form of two 300-mg tablets taken orally twice daily with or without food. Phy

If hematologic toxicities occur while taking rucaparib, treatment should be interrupted and blood counts monitored until recovery and failure to recover to grade 1 or higher after 4 weeks should prompt referral to a hematologist for further investigation, while confirmed diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia should lead to discontinuation of rucaparib. Pregnant women and those of reproductive potential should be advised of the potential risk to a fetus or the need for effective contraception during treatment and for 6 months after the last dose of rucaparib.

Rucaparib is indicated only for the treatment of patients with confirmed BRCA1/2 mutations, so the drug was approved in conjunction with a companion diagnostic. FoundationFocus CDxBRCA is the first next-generation sequencing-based test to receive FDA approval and detects the presence of deleterious BRCA gene mutations in tumor tissue samples. Rucaparib is marketed as Rubraca by Clovis Oncology Inc, and the companion diagnostic by Foundation Medicine Inc.

1. Rubraca (rucaparib) capsules, for oral use. Prescribing information. Clovis Oncology Inc. http://clovisoncology.com/files/rubraca-prescribing-info.pdf. Released December 2016. Accessed January 8th, 2017.

2. FDA grants accelerated approval to new treatment for advanced ovarian cancer. FDA News Release. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm533873.htm. Last updated December 19, 2016. Accessed January 8, 2017.

3. [No author listed.] Rucaparib approved for ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. Epub ahead of print. January 5, 2017. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290. CD-NB2016-164.

1. Rubraca (rucaparib) capsules, for oral use. Prescribing information. Clovis Oncology Inc. http://clovisoncology.com/files/rubraca-prescribing-info.pdf. Released December 2016. Accessed January 8th, 2017.

2. FDA grants accelerated approval to new treatment for advanced ovarian cancer. FDA News Release. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm533873.htm. Last updated December 19, 2016. Accessed January 8, 2017.

3. [No author listed.] Rucaparib approved for ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. Epub ahead of print. January 5, 2017. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290. CD-NB2016-164.

End-of-life options and the legal pathways to physician aid in dying

By early 2017, roughly 18% of all US citizens will reside in a state with a legal pathway to physician aid in dying via lethal prescription. When the End of Life Options Act (EOLOA) went into effect in in California in June 2016, it became the fourth state with laws allowing physician aid in dying (PAD). Oregon (1997), Washington (2009), and Vermont (2009) had preceded it, and Montana (2009) operates similarly as a result of a Supreme Court decision there. However, California’s law also legalized PAD in a state that is much larger and more socioeconomically diverse than the other four states – with its 39 million residents, California more than triples the number of Americans who live in PAD legal states. Together, these 5 states represent 16% of the entire US population (roughly 321 million according to the 2015 Census). Most recently, in December 2016, they were joined by Colorado, adding a state population of 5.5 million.

The state laws have much in common: to “qualify” for legal access to a lethal prescription, a patient must make an in-person verbal request to his/her attending physician. The patient must also: be an adult (aged 18 years or older); be a resident of that state; have a terminal illness the course of which is expected to lead to natural death within 6 months; be making a noncoerced, voluntary request; repeat the verbal request no sooner than 15 days after the first request, followed by a witnessed, formal written request; and have the capacity to self-administer the lethal prescription in a private setting.1

In California, as in the other states, additional safeguards are built in: the terminal diagnosis and the patient’s capacity to make the request must be verified by a second, independent consultant physician. If either the attending or the consultant physician finds evidence of a “mental disorder,” they are obligated under the law to refer the patient to a psychiatrist or psychologist for an evaluation. The psychological expert is charged with verifying the patient’s mental capacity and ability to make a voluntary end-of-life choice, with determining whether a mental disorder is in fact present, and if it is, whether that mental disorder is impairing the patient’s judgment. A finding of impaired judgment due to mental disorder halts the legal process until the disorder is rectified by treatment, the passage of time, or other factors.

Many of the themes and concepts outlined in these laws are familiar to oncology clinicians simply because we take care of seriously ill and dying patients. Indeed, access to the Medicare Hospice Benefit requires certification – often by an oncologist – that a patient has a terminal diagnosis with a maximum 6-month expected survival. In addition, oncologists encounter many patients who wish to talk about quality of life while they weigh various treatment options, and it is normative for patients (though often anxiety producing for clinicians) to broach topics related to end of life, symptom management, and even aid in dying. Many patients fear poor quality of life, intractable symptom burden, dependency on others, and loss of control more than they fear their cancers. Their efforts to initiate this discussion often fit into a much larger and more durable set of personal values and ideals about suffering, dependency, futility, and personal autonomy.

Weighing the evidence

And yet there is vigorous objection to PAD laws from many corners. Some religious organizations and faith-based health care delivery systems oppose the laws and, in opting-out of the voluntary legal pathways for participation, prohibit their employed and affiliated physicians and other professionals from doing so as well.2 Some physician organizations, and individual physicians, claim that involvement in aid in dying – such as by providing a legal lethal prescription – violates the Hippocratic oath and that (in effect) there is no circumstance under which it could be ethically permissible.

There are also bioethicists, including physician ethicists, who sincerely reach similar conclusions and warn of the “slippery slope” that might lead beyond aid in dying as currently legalized in the US to assisting in the deaths of those with disabilities, those with depression or other treatable psychiatric illness, and even to active euthanasia, including euthanasia of nonconsenting or incapable individuals.3 These objectors generally remain adamant and cite what we would all agree are excesses in certain European countries, despite the absence of evidence that the European measures could be approved in the United States under current laws and practices.

The largest amount of publicly available evidence to inform this discussion in the US comes from Oregon, which has nearly 20 years of experience with the law and its reporting requirements.4 Very broadly, the Oregon experience supports the view that PAD is pursued and completed by a very small percentage of the population: in 2015 (the most recent year for which data is available) 218 people possessed lethal prescriptions; 132 of them ingested the medications and died. Thus about 61% of those who received the prescription used it for its intended purpose, resulting in a Death with Dignity Act death rate of 0.39% (132 of 34,160 deaths in Oregon) in 2015. Since the law’s inception in 1997, 991 patients are known to have died from lethal ingestion of 1545 prescriptions written (a 64% “use” rate).

Equally important is the evidence from Oregon describing those who seek to use the law. In 2015, as in previous years, most patients were older than the general population (78% aged 65 years or older; median age at death, 73). Of those patients, 93% were white and well educated (43% had at least a college degree), compared with the population at large. In all, 72%-78% of patients had cancer; 6%-8% had ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis); and end-stage heart disease seemed to be increasing, trending up from 2% to 6% in recent years.

In addition, 90% died at home, with 92% on hospice, and more than 99% had health insurance of some kind. These figures provide strong evidence that PAD is not being inappropriately used among historically vulnerable or disempowered ethnic/racial minorities, socioeconomically or educationally disadvantaged groups, or disabled individuals. On the contrary, “uptake” or use of PAD by the disadvantaged in Oregon seems, perhaps not surprisingly, to occur at rates significantly below their representation in the general population of the state.

Intractable symptom burden (or fear of it) was rated as a minor contributor to the decision to pursue PAD, ranking sixth out of the 7 options and endorsed by about a quarter of patients. The three most frequently cited end-of-life concerns were: decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable (96%), loss of autonomy (92%), and loss of dignity (75%).

A broader range of choice

I have worked for nearly 30 years in California oncology clinical settings as a palliative care physician and psychiatrist. During that time I have been involved in the care of two patients who committed violent suicide (self-inflicted gunshot). Both events took place before the passage of the California EOLOA, both patients were educated, professional older white men who were fiercely independent and who saw their progressive cancers as rapidly worsening their quality of life and intolerably increasing their dependency on beloved others (although their judgments about this did not take into account how the others actually felt); neither had a primary psychiatric illness, and neither had intractable symptom burden. Both men had expressed interest in and were denied access to lethal prescription. Sadly, neither had the kind of long-term, trusting relationship with a physician that appears to have provided access to non-legally sanctioned PAD for decades before the first state laws allowing it – and therefore each apparently decided to exert his autonomy in the ultimate act of self-determination. In both cases, it seemed to me that violent suicide was a bad, last recourse – clearly, each man regarded continued living in his intolerable state as even worse – but also the worst possible outcome for their surviving families, for their traumatized clinicians, and for the bystanders who witnessed these deaths and the first responders who were called to the scenes. We cannot know that the availability of lethal prescription would have pre-empted these violent suicides, but I suspect it might have given each man a much broader range of choice about how to deal with circumstances he found entirely unacceptable, and which he simply could not and would not tolerate.

An informed, person-centered approach

It is in the context of these experiences that I have come to view “active non-participation” in legal PAD – that is, decisions by individual physicians and/or health systems not only to not provide, but also not refer patients to possibly willing providers and systems without regard for specific clinical contexts – as a toxic form of patient abandonment. I am also concerned that this rigid stance (like many rigid stances in the service of alleged moral absolutes) may lead to greater suffering and harm – such as the violent suicides I have described – than a more moderate, contextually informed, person-centered approach that does not outlaw certain clinical topics. Indeed, in my participating institution in California, it has become clear that a request for PAD leads (as a result of a carefully and comprehensively constructed “navigator” process) to a level of patient and family care that should be provided to every patient with terminal illness in this country. While that statement is a sad reflection on our society’s general commitment to caring for the dying, it seems that the extra attention required by the process leading to a PAD, and the revelations that emerge in that process, often lead to a withdrawal of the request for a lethal prescription, and/or allows the drug to go unused if provided.

Many leading bioethical treatises, including those emerging from faith-based academic and university settings, also support the view that PAD can be and is morally justified under a certain set of circumstances. Not surprisingly, those circumstances encompass most of what is written into the state laws permitting PAD. They include, according to Beauchamp and Childress:5

- A voluntary request by a competent patient

- An ongoing physician-patient relationship

- Mutual and informed decision-making by patient and physician

- A supportive yet critical and probing environment of decision making

- A considered rejection of alternatives

- Structured consultation with other parties in medicine

- A patient’s expression of a durable preference for death

- Unacceptable suffering by the patient

- Use of a means that is as painless and comfortable as possible

We tell many of our patients that cancer is now treated as a chronic illness. In the context of treating that chronic illness we have the profound opportunity – some would say the obligation – to come to know our patients as whole individuals who often have long-held health values, ideas about what a life worth living looks like, and very personal fears and hopes. We may well come to know them more intimately while serving as their cancer clinicians than any other health professionals do – and even as do any other individuals with whom they will ever interact.

The hours in the infusion chair afford many opportunities for us to understand (and, ideally, document) a patient’s advance care plans, health values, goals, views about end-of-life measures such as artificial ventilation and resuscitation. No one reasonably disputes the “rightness” of learning these things. The evidence shows us that under very rare circumstances, knowing and respecting our patients may include understanding their wishes about physician aid in dying, which requires us to build upon the profound trust that has been established by being able to hear and understand their requests. It seems to me that the end of life is the most inappropriate time for any of us to tell patients they must look elsewhere.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author alone, and do not reflect the view of other individuals, institutions, or professional organizations with which Dr Strouse is affiliated.

1. Gostin LO, Roberts AE. Physician assisted dying: a turning point? JAMA 2016;315;249-250.

2. Buck C. With barbiturates and martini, Sonoma man among first Californians to die under end-of-life law. http://www.sacbee.com/news/local/health-and-medicine/article95676342.html. Published August 16, 2016. Accessed January 17, 2017.

3. Snyder L, Sulmasy DP. Physician-assisted suicide. http://annals.org/aim/article/714672/physician-assisted-suicide. Published August 7, 2001. Accessed January 17, 2017.

4. Oregan Public Health Division. Oregan Death With Dignity Act: 2015 data summary. https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year18.pdf. Published February 4, 2016. Accessed January 17, 2017.

5. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Nonmaleficence. In Principles of biomedical ethics. 7th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013:184.

By early 2017, roughly 18% of all US citizens will reside in a state with a legal pathway to physician aid in dying via lethal prescription. When the End of Life Options Act (EOLOA) went into effect in in California in June 2016, it became the fourth state with laws allowing physician aid in dying (PAD). Oregon (1997), Washington (2009), and Vermont (2009) had preceded it, and Montana (2009) operates similarly as a result of a Supreme Court decision there. However, California’s law also legalized PAD in a state that is much larger and more socioeconomically diverse than the other four states – with its 39 million residents, California more than triples the number of Americans who live in PAD legal states. Together, these 5 states represent 16% of the entire US population (roughly 321 million according to the 2015 Census). Most recently, in December 2016, they were joined by Colorado, adding a state population of 5.5 million.

The state laws have much in common: to “qualify” for legal access to a lethal prescription, a patient must make an in-person verbal request to his/her attending physician. The patient must also: be an adult (aged 18 years or older); be a resident of that state; have a terminal illness the course of which is expected to lead to natural death within 6 months; be making a noncoerced, voluntary request; repeat the verbal request no sooner than 15 days after the first request, followed by a witnessed, formal written request; and have the capacity to self-administer the lethal prescription in a private setting.1

In California, as in the other states, additional safeguards are built in: the terminal diagnosis and the patient’s capacity to make the request must be verified by a second, independent consultant physician. If either the attending or the consultant physician finds evidence of a “mental disorder,” they are obligated under the law to refer the patient to a psychiatrist or psychologist for an evaluation. The psychological expert is charged with verifying the patient’s mental capacity and ability to make a voluntary end-of-life choice, with determining whether a mental disorder is in fact present, and if it is, whether that mental disorder is impairing the patient’s judgment. A finding of impaired judgment due to mental disorder halts the legal process until the disorder is rectified by treatment, the passage of time, or other factors.

Many of the themes and concepts outlined in these laws are familiar to oncology clinicians simply because we take care of seriously ill and dying patients. Indeed, access to the Medicare Hospice Benefit requires certification – often by an oncologist – that a patient has a terminal diagnosis with a maximum 6-month expected survival. In addition, oncologists encounter many patients who wish to talk about quality of life while they weigh various treatment options, and it is normative for patients (though often anxiety producing for clinicians) to broach topics related to end of life, symptom management, and even aid in dying. Many patients fear poor quality of life, intractable symptom burden, dependency on others, and loss of control more than they fear their cancers. Their efforts to initiate this discussion often fit into a much larger and more durable set of personal values and ideals about suffering, dependency, futility, and personal autonomy.

Weighing the evidence

And yet there is vigorous objection to PAD laws from many corners. Some religious organizations and faith-based health care delivery systems oppose the laws and, in opting-out of the voluntary legal pathways for participation, prohibit their employed and affiliated physicians and other professionals from doing so as well.2 Some physician organizations, and individual physicians, claim that involvement in aid in dying – such as by providing a legal lethal prescription – violates the Hippocratic oath and that (in effect) there is no circumstance under which it could be ethically permissible.

There are also bioethicists, including physician ethicists, who sincerely reach similar conclusions and warn of the “slippery slope” that might lead beyond aid in dying as currently legalized in the US to assisting in the deaths of those with disabilities, those with depression or other treatable psychiatric illness, and even to active euthanasia, including euthanasia of nonconsenting or incapable individuals.3 These objectors generally remain adamant and cite what we would all agree are excesses in certain European countries, despite the absence of evidence that the European measures could be approved in the United States under current laws and practices.

The largest amount of publicly available evidence to inform this discussion in the US comes from Oregon, which has nearly 20 years of experience with the law and its reporting requirements.4 Very broadly, the Oregon experience supports the view that PAD is pursued and completed by a very small percentage of the population: in 2015 (the most recent year for which data is available) 218 people possessed lethal prescriptions; 132 of them ingested the medications and died. Thus about 61% of those who received the prescription used it for its intended purpose, resulting in a Death with Dignity Act death rate of 0.39% (132 of 34,160 deaths in Oregon) in 2015. Since the law’s inception in 1997, 991 patients are known to have died from lethal ingestion of 1545 prescriptions written (a 64% “use” rate).

Equally important is the evidence from Oregon describing those who seek to use the law. In 2015, as in previous years, most patients were older than the general population (78% aged 65 years or older; median age at death, 73). Of those patients, 93% were white and well educated (43% had at least a college degree), compared with the population at large. In all, 72%-78% of patients had cancer; 6%-8% had ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis); and end-stage heart disease seemed to be increasing, trending up from 2% to 6% in recent years.

In addition, 90% died at home, with 92% on hospice, and more than 99% had health insurance of some kind. These figures provide strong evidence that PAD is not being inappropriately used among historically vulnerable or disempowered ethnic/racial minorities, socioeconomically or educationally disadvantaged groups, or disabled individuals. On the contrary, “uptake” or use of PAD by the disadvantaged in Oregon seems, perhaps not surprisingly, to occur at rates significantly below their representation in the general population of the state.

Intractable symptom burden (or fear of it) was rated as a minor contributor to the decision to pursue PAD, ranking sixth out of the 7 options and endorsed by about a quarter of patients. The three most frequently cited end-of-life concerns were: decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable (96%), loss of autonomy (92%), and loss of dignity (75%).

A broader range of choice