User login

Screen for comorbidities in pyoderma gangrenosum

PORTLAND, ORE. – Comorbidities were common in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), in a single-center retrospective cohort study of 130 patients.

These comorbid diagnoses were not only clinically significant in themselves, but also were associated with changes in treatment efficacy, highlighting the need for holistic surveillance of patients with PG, Alexander Fischer, MPH, said during an oral presentation of his poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. “We should really be screening patients with PG for multiple comorbid conditions,” he emphasized.

The study included patients seen for PG at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, between 2006 and 2015. The most common comorbidity was inflammatory bowel disease (35%), followed by hidradenitis suppurativa (14%), rheumatoid arthritis (12%), monoclonal gammopathy (12%), leukemia (2%), and lymphoma (2%). “Interestingly, a substantial proportion of patients had multiple systemic diseases,” Mr. Fischer said. “For example, among our PG patients with rheumatoid arthritis, over a third also had comorbid inflammatory bowel disease. We saw this pattern repeat itself in patients with comorbid hidradenitis suppurativa, and also in patients with comorbid monoclonal gammopathy.”

The researchers used rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria to verify the diagnosis of PG, said Mr. Fischer, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who conducted the analysis under the mentorship of Gerald S. Lazarus, MD, professor of dermatology and medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. A total of 69% of patients were female, 58% were white, and 35% were black. The average age of PG onset was 47 years. Notably, patients with comorbid hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) had an earlier age of PG onset and were more likely to be black than were patients without comorbid HS, and 53% of young black females with PG onset also had HS.

The investigators explored whether the effect of systemic PG therapies varied in the presence of comorbidities. In a crude analysis of 32 patients who received infliximab (Remicade) for PG, those with comorbid HS were significantly more likely to achieve complete healing of PG wounds (83%) than were those without comorbid HS (31%; P = .03), Mr. Fischer reported. “Our sample size was small for this analysis, but we thought this was an interesting finding that perhaps warrants further investigation,” he said. “We need to do larger longitudinal studies that account for wound characteristics and that include more therapies to get a better grasp of this question.”

Only 57% of patients in this study had their diagnosis confirmed by biopsy, Mr. Fischer noted. However, this study generally resembles others in terms of comorbidity prevalence. For example, a single-center study of 103 patients with PG at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, found that 34% of patients had comorbid IBD compared with 35% in the Hopkins cohort (Br J Dermatol. 2011 Dec;165[6]:1244-50). In a study of 121 patients with PG at three wound care centers in Germany, 10% of patients had IBD, but 14% had rheumatologic conditions and 7% had blood cancers (J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016 Oct;14[10]:1023-30).

Mr. Fischer cited no external funding sources. He had no relevant financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Comorbidities were common in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), in a single-center retrospective cohort study of 130 patients.

These comorbid diagnoses were not only clinically significant in themselves, but also were associated with changes in treatment efficacy, highlighting the need for holistic surveillance of patients with PG, Alexander Fischer, MPH, said during an oral presentation of his poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. “We should really be screening patients with PG for multiple comorbid conditions,” he emphasized.

The study included patients seen for PG at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, between 2006 and 2015. The most common comorbidity was inflammatory bowel disease (35%), followed by hidradenitis suppurativa (14%), rheumatoid arthritis (12%), monoclonal gammopathy (12%), leukemia (2%), and lymphoma (2%). “Interestingly, a substantial proportion of patients had multiple systemic diseases,” Mr. Fischer said. “For example, among our PG patients with rheumatoid arthritis, over a third also had comorbid inflammatory bowel disease. We saw this pattern repeat itself in patients with comorbid hidradenitis suppurativa, and also in patients with comorbid monoclonal gammopathy.”

The researchers used rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria to verify the diagnosis of PG, said Mr. Fischer, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who conducted the analysis under the mentorship of Gerald S. Lazarus, MD, professor of dermatology and medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. A total of 69% of patients were female, 58% were white, and 35% were black. The average age of PG onset was 47 years. Notably, patients with comorbid hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) had an earlier age of PG onset and were more likely to be black than were patients without comorbid HS, and 53% of young black females with PG onset also had HS.

The investigators explored whether the effect of systemic PG therapies varied in the presence of comorbidities. In a crude analysis of 32 patients who received infliximab (Remicade) for PG, those with comorbid HS were significantly more likely to achieve complete healing of PG wounds (83%) than were those without comorbid HS (31%; P = .03), Mr. Fischer reported. “Our sample size was small for this analysis, but we thought this was an interesting finding that perhaps warrants further investigation,” he said. “We need to do larger longitudinal studies that account for wound characteristics and that include more therapies to get a better grasp of this question.”

Only 57% of patients in this study had their diagnosis confirmed by biopsy, Mr. Fischer noted. However, this study generally resembles others in terms of comorbidity prevalence. For example, a single-center study of 103 patients with PG at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, found that 34% of patients had comorbid IBD compared with 35% in the Hopkins cohort (Br J Dermatol. 2011 Dec;165[6]:1244-50). In a study of 121 patients with PG at three wound care centers in Germany, 10% of patients had IBD, but 14% had rheumatologic conditions and 7% had blood cancers (J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016 Oct;14[10]:1023-30).

Mr. Fischer cited no external funding sources. He had no relevant financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Comorbidities were common in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), in a single-center retrospective cohort study of 130 patients.

These comorbid diagnoses were not only clinically significant in themselves, but also were associated with changes in treatment efficacy, highlighting the need for holistic surveillance of patients with PG, Alexander Fischer, MPH, said during an oral presentation of his poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. “We should really be screening patients with PG for multiple comorbid conditions,” he emphasized.

The study included patients seen for PG at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, between 2006 and 2015. The most common comorbidity was inflammatory bowel disease (35%), followed by hidradenitis suppurativa (14%), rheumatoid arthritis (12%), monoclonal gammopathy (12%), leukemia (2%), and lymphoma (2%). “Interestingly, a substantial proportion of patients had multiple systemic diseases,” Mr. Fischer said. “For example, among our PG patients with rheumatoid arthritis, over a third also had comorbid inflammatory bowel disease. We saw this pattern repeat itself in patients with comorbid hidradenitis suppurativa, and also in patients with comorbid monoclonal gammopathy.”

The researchers used rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria to verify the diagnosis of PG, said Mr. Fischer, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who conducted the analysis under the mentorship of Gerald S. Lazarus, MD, professor of dermatology and medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. A total of 69% of patients were female, 58% were white, and 35% were black. The average age of PG onset was 47 years. Notably, patients with comorbid hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) had an earlier age of PG onset and were more likely to be black than were patients without comorbid HS, and 53% of young black females with PG onset also had HS.

The investigators explored whether the effect of systemic PG therapies varied in the presence of comorbidities. In a crude analysis of 32 patients who received infliximab (Remicade) for PG, those with comorbid HS were significantly more likely to achieve complete healing of PG wounds (83%) than were those without comorbid HS (31%; P = .03), Mr. Fischer reported. “Our sample size was small for this analysis, but we thought this was an interesting finding that perhaps warrants further investigation,” he said. “We need to do larger longitudinal studies that account for wound characteristics and that include more therapies to get a better grasp of this question.”

Only 57% of patients in this study had their diagnosis confirmed by biopsy, Mr. Fischer noted. However, this study generally resembles others in terms of comorbidity prevalence. For example, a single-center study of 103 patients with PG at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, found that 34% of patients had comorbid IBD compared with 35% in the Hopkins cohort (Br J Dermatol. 2011 Dec;165[6]:1244-50). In a study of 121 patients with PG at three wound care centers in Germany, 10% of patients had IBD, but 14% had rheumatologic conditions and 7% had blood cancers (J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016 Oct;14[10]:1023-30).

Mr. Fischer cited no external funding sources. He had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT SID 2017

Key clinical point: Carefully screen for comorbidities when patients have pyoderma gangrenosum (PG).

Major finding: The most common comorbidity was inflammatory bowel disease (35%), followed by hidradenitis suppurativa (14%), rheumatoid arthritis (12%), monoclonal gammopathy (12%), leukemia (2%), and lymphoma (2%).

Data source: A single-center retrospective study of 130 patients seen for pyoderma gangrenosum between 2006 and 2015.

Disclosures: Mr. Fischer cited no external funding sources. He had no relevant financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Sutureless aortic valve shows promise in IDE trial

BOSTON – A new study highlights the success, safety, and effectiveness of a new sutureless aortic valve device in patients with severe symptomatic aortic valve stenosis (AS).

The findings, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, were based on a prospective, single-arm clinical trial approved under a Food and Drug Administration Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) that aimed to assess the safety and efficacy of a new bovine pericardial sutureless aortic valve in patients with severe AS undergoing aortic valve replacement with or without concomitant procedures. In this video interview, Michael Borger, MD, explains how the study was conducted and what the findings mean for future use of the sutureless aortic valve device.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

BOSTON – A new study highlights the success, safety, and effectiveness of a new sutureless aortic valve device in patients with severe symptomatic aortic valve stenosis (AS).

The findings, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, were based on a prospective, single-arm clinical trial approved under a Food and Drug Administration Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) that aimed to assess the safety and efficacy of a new bovine pericardial sutureless aortic valve in patients with severe AS undergoing aortic valve replacement with or without concomitant procedures. In this video interview, Michael Borger, MD, explains how the study was conducted and what the findings mean for future use of the sutureless aortic valve device.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

BOSTON – A new study highlights the success, safety, and effectiveness of a new sutureless aortic valve device in patients with severe symptomatic aortic valve stenosis (AS).

The findings, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, were based on a prospective, single-arm clinical trial approved under a Food and Drug Administration Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) that aimed to assess the safety and efficacy of a new bovine pericardial sutureless aortic valve in patients with severe AS undergoing aortic valve replacement with or without concomitant procedures. In this video interview, Michael Borger, MD, explains how the study was conducted and what the findings mean for future use of the sutureless aortic valve device.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

AT THE AATS ANNUAL MEETING

Chronic GVHD linked to fivefold increase in squamous cell skin carcinomas

PORTLAND – Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD) was associated with a fivefold increase in risk of squamous cell carcinoma and a nearly twofold rise in the rate of basal cell carcinoma, based on a meta-analysis of eight studies.

Acute GVHD was not tied to an increase in secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers, Pooja H. Rambhia and her associates reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. The findings highlight the need for multidisciplinary consults to distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD and for vigorous surveillance for skin cancer even years after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

GVHS has been linked to secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers in previous studies, but few have quantified the risk, according to the reviewers, who are from the department of dermatology and dermatopathology at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. The increased risk may be related to the heavy immunosuppression needed to treat chronic GVHD.

For the meta-analysis, the researchers identified 1,411 studies recorded in academic databases and reviewed those that reported both cases of skin cancers and GVHD. Seven retrospective, and one prospective, studies published between 1997 and 2012 measured both variables in all patients.

The studies included more than 56,000 patients followed for up to 36 years after undergoing allogeneic or syngeneic transplantation, the reviewers reported. During follow-up, between 17% and 73% of patients developed chronic GVHD, and 29% to 67% developed acute GVHD. There were 98 cases of basal cell carcinoma, 49 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, and 34 cases of malignant melanoma. Chronic GVHD was significantly associated with both squamous cell carcinoma (risk ratio, 5.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.4-11.8; P less than .001) and basal cell carcinoma (RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0; P = .002). In contrast, chronic GVHD showed a nonsignificant trend toward an inverse correlation with the risk of secondary melanoma. Acute GVHD was not linked with squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, or melanoma.

GVHD develops, up to half the time, after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and often becomes chronic, the reviewers noted. Catching skin cancer early is crucial, and transplant patients should undergo regular skin checks with multidisciplinary consults to promptly, accurately distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of GVHD, they added.

The researchers did not report external funding sources. They had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND – Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD) was associated with a fivefold increase in risk of squamous cell carcinoma and a nearly twofold rise in the rate of basal cell carcinoma, based on a meta-analysis of eight studies.

Acute GVHD was not tied to an increase in secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers, Pooja H. Rambhia and her associates reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. The findings highlight the need for multidisciplinary consults to distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD and for vigorous surveillance for skin cancer even years after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

GVHS has been linked to secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers in previous studies, but few have quantified the risk, according to the reviewers, who are from the department of dermatology and dermatopathology at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. The increased risk may be related to the heavy immunosuppression needed to treat chronic GVHD.

For the meta-analysis, the researchers identified 1,411 studies recorded in academic databases and reviewed those that reported both cases of skin cancers and GVHD. Seven retrospective, and one prospective, studies published between 1997 and 2012 measured both variables in all patients.

The studies included more than 56,000 patients followed for up to 36 years after undergoing allogeneic or syngeneic transplantation, the reviewers reported. During follow-up, between 17% and 73% of patients developed chronic GVHD, and 29% to 67% developed acute GVHD. There were 98 cases of basal cell carcinoma, 49 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, and 34 cases of malignant melanoma. Chronic GVHD was significantly associated with both squamous cell carcinoma (risk ratio, 5.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.4-11.8; P less than .001) and basal cell carcinoma (RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0; P = .002). In contrast, chronic GVHD showed a nonsignificant trend toward an inverse correlation with the risk of secondary melanoma. Acute GVHD was not linked with squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, or melanoma.

GVHD develops, up to half the time, after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and often becomes chronic, the reviewers noted. Catching skin cancer early is crucial, and transplant patients should undergo regular skin checks with multidisciplinary consults to promptly, accurately distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of GVHD, they added.

The researchers did not report external funding sources. They had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND – Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD) was associated with a fivefold increase in risk of squamous cell carcinoma and a nearly twofold rise in the rate of basal cell carcinoma, based on a meta-analysis of eight studies.

Acute GVHD was not tied to an increase in secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers, Pooja H. Rambhia and her associates reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. The findings highlight the need for multidisciplinary consults to distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD and for vigorous surveillance for skin cancer even years after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

GVHS has been linked to secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers in previous studies, but few have quantified the risk, according to the reviewers, who are from the department of dermatology and dermatopathology at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. The increased risk may be related to the heavy immunosuppression needed to treat chronic GVHD.

For the meta-analysis, the researchers identified 1,411 studies recorded in academic databases and reviewed those that reported both cases of skin cancers and GVHD. Seven retrospective, and one prospective, studies published between 1997 and 2012 measured both variables in all patients.

The studies included more than 56,000 patients followed for up to 36 years after undergoing allogeneic or syngeneic transplantation, the reviewers reported. During follow-up, between 17% and 73% of patients developed chronic GVHD, and 29% to 67% developed acute GVHD. There were 98 cases of basal cell carcinoma, 49 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, and 34 cases of malignant melanoma. Chronic GVHD was significantly associated with both squamous cell carcinoma (risk ratio, 5.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.4-11.8; P less than .001) and basal cell carcinoma (RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0; P = .002). In contrast, chronic GVHD showed a nonsignificant trend toward an inverse correlation with the risk of secondary melanoma. Acute GVHD was not linked with squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, or melanoma.

GVHD develops, up to half the time, after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and often becomes chronic, the reviewers noted. Catching skin cancer early is crucial, and transplant patients should undergo regular skin checks with multidisciplinary consults to promptly, accurately distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of GVHD, they added.

The researchers did not report external funding sources. They had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

AT SID 2017

Key clinical point: Chronic graft versus host disease was associated with a significantly increased risk of squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas.

Major finding: Chronic GVHD was associated with a fivefold increase in squamous cell carcinoma (risk ratio, 5.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.4 to 11.8; P less than .001).

Data source: A meta-analysis of eight cohort studies of 56,000 patients who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Disclosures: The researchers did not report external funding sources. They had no conflicts of interest.

Topical tretinoin resolves inflammatory symptoms in rosacea, in small study

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA – Treatment with topical tretinoin resulted in complete resolution of rosacea symptoms in a significant number of patients, in a small retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

“As an intermediary step between topical antibiotics and oral isotretinoin, we propose that topical tretinoin may be effective in the management and reduction of rosacea symptoms,” Emily Forward, MD, of the University of Sydney, said at the meeting. There has been recent discussion regarding the use of low-dose isotretinoin in the treatment of rosacea, but safety with long-term use is an issue, she noted.

More than 80% of patients had complete or excellent resolution of papules and pustules, with only one patient showing no benefit. Of the patients with erythema as the primary feature of their rosacea, 42% achieved complete resolution, 33% achieved excellent resolution, 17% achieved a good response, and 8% showed no benefit, Dr. Forward reported.

Among patients with telangiectasia, 40% achieved complete resolution, while 37% of those with flushing achieved complete resolution.

Topical tretinoin should be considered among the treatment options for rosacea “as it is effective, well tolerated, and has synergistic benefits in the prevention of photoaging,” Dr. Forward said. The ideal patient candidate would be someone with inflammatory features such as papules, pustules, or erythema, she added.

No patients experienced worsening of their symptoms with treatment, although one patient stopped treatment because of adverse effects. Dr. Forward also stressed that tretinoin is a known teratogen, so it should not be used during pregnancy or breastfeeding, or in patients trying to conceive.

In an interview, Dr. Forward said that she and her associates were surprised at the degree of improvement with topical tretinoin, particularly for erythema symptoms. However, she said it was important to educate patients about how to use topical tretinoin. “You use a pea-sized amount, at night, and in the beginning we advise them to use it every second or third day, and if they tolerate it they can increase the amount,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA – Treatment with topical tretinoin resulted in complete resolution of rosacea symptoms in a significant number of patients, in a small retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

“As an intermediary step between topical antibiotics and oral isotretinoin, we propose that topical tretinoin may be effective in the management and reduction of rosacea symptoms,” Emily Forward, MD, of the University of Sydney, said at the meeting. There has been recent discussion regarding the use of low-dose isotretinoin in the treatment of rosacea, but safety with long-term use is an issue, she noted.

More than 80% of patients had complete or excellent resolution of papules and pustules, with only one patient showing no benefit. Of the patients with erythema as the primary feature of their rosacea, 42% achieved complete resolution, 33% achieved excellent resolution, 17% achieved a good response, and 8% showed no benefit, Dr. Forward reported.

Among patients with telangiectasia, 40% achieved complete resolution, while 37% of those with flushing achieved complete resolution.

Topical tretinoin should be considered among the treatment options for rosacea “as it is effective, well tolerated, and has synergistic benefits in the prevention of photoaging,” Dr. Forward said. The ideal patient candidate would be someone with inflammatory features such as papules, pustules, or erythema, she added.

No patients experienced worsening of their symptoms with treatment, although one patient stopped treatment because of adverse effects. Dr. Forward also stressed that tretinoin is a known teratogen, so it should not be used during pregnancy or breastfeeding, or in patients trying to conceive.

In an interview, Dr. Forward said that she and her associates were surprised at the degree of improvement with topical tretinoin, particularly for erythema symptoms. However, she said it was important to educate patients about how to use topical tretinoin. “You use a pea-sized amount, at night, and in the beginning we advise them to use it every second or third day, and if they tolerate it they can increase the amount,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA – Treatment with topical tretinoin resulted in complete resolution of rosacea symptoms in a significant number of patients, in a small retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

“As an intermediary step between topical antibiotics and oral isotretinoin, we propose that topical tretinoin may be effective in the management and reduction of rosacea symptoms,” Emily Forward, MD, of the University of Sydney, said at the meeting. There has been recent discussion regarding the use of low-dose isotretinoin in the treatment of rosacea, but safety with long-term use is an issue, she noted.

More than 80% of patients had complete or excellent resolution of papules and pustules, with only one patient showing no benefit. Of the patients with erythema as the primary feature of their rosacea, 42% achieved complete resolution, 33% achieved excellent resolution, 17% achieved a good response, and 8% showed no benefit, Dr. Forward reported.

Among patients with telangiectasia, 40% achieved complete resolution, while 37% of those with flushing achieved complete resolution.

Topical tretinoin should be considered among the treatment options for rosacea “as it is effective, well tolerated, and has synergistic benefits in the prevention of photoaging,” Dr. Forward said. The ideal patient candidate would be someone with inflammatory features such as papules, pustules, or erythema, she added.

No patients experienced worsening of their symptoms with treatment, although one patient stopped treatment because of adverse effects. Dr. Forward also stressed that tretinoin is a known teratogen, so it should not be used during pregnancy or breastfeeding, or in patients trying to conceive.

In an interview, Dr. Forward said that she and her associates were surprised at the degree of improvement with topical tretinoin, particularly for erythema symptoms. However, she said it was important to educate patients about how to use topical tretinoin. “You use a pea-sized amount, at night, and in the beginning we advise them to use it every second or third day, and if they tolerate it they can increase the amount,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

AT ACDASM 2017

Key clinical point: Topical tretinoin may be useful in treating erythema and the inflammatory symptoms of rosacea.

Major finding: More than 80% of patients with rosacea had complete or excellent resolution of papules and pustules with topical tretinoin 0.05%.

Data source: A retrospective study of 25 patients with mild to severe rosacea.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

My mundane genetic testing results

I’ve never been particularly curious about my genetic background. We have a pretty clear family history that I’m of central European and Russian descent, with my ancestors coming over in groups between 1900 and 1938.

Recently, my mother decided she wanted more genetic information on us, so she paid $99 for us to send saliva samples to a company that advertises such services.

A few weeks went by. You read about people who find out they have a genetic background that’s quite surprising. I began to wonder: Would there be some giant family history shocker when the results came in?

I’ve since spoken to others who had paid for this service and found most had the same experience. The test confirmed what was already well known, except for one friend whose results suggested a trace of Polynesian blood somewhere in his background. He believes this was likely artefactual, though he enjoys the idea that somewhere in history a Tongan warrior was blown off course at sea and somehow ended up in Odessa, Ukraine.

Of course, as I’ve now learned, that’s only the start of things. These days, I get emails advertising a more detailed panel (for an additional fee), looking for genetic markers for disease and more obscure traits. I also receive the occasional one from someone who, through the company’s anonymous servers, thinks they may be related to me.

I don’t answer either of those. I have no desire to expand my family circle beyond what it already is.

As for the disease testing? Not interested. Yes, some genetic tests may be helpful in making better choices, but the majority, at least to me, are still a work in progress. We deal with both false negatives and false positives in medicine. I routinely discourage my patients from spending money on unproven testing and treatments and have no desire to do the same myself. Maybe someday it will be worth the additional dollars, but I’m not convinced it’s there.

Money is, for better or worse, the driving force for all technologies, medical and otherwise. Maybe my $99 investment will help pay dividends down the road for someone, but today it only resulted in a shoulder shrug and chuckle at what I already knew.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ve never been particularly curious about my genetic background. We have a pretty clear family history that I’m of central European and Russian descent, with my ancestors coming over in groups between 1900 and 1938.

Recently, my mother decided she wanted more genetic information on us, so she paid $99 for us to send saliva samples to a company that advertises such services.

A few weeks went by. You read about people who find out they have a genetic background that’s quite surprising. I began to wonder: Would there be some giant family history shocker when the results came in?

I’ve since spoken to others who had paid for this service and found most had the same experience. The test confirmed what was already well known, except for one friend whose results suggested a trace of Polynesian blood somewhere in his background. He believes this was likely artefactual, though he enjoys the idea that somewhere in history a Tongan warrior was blown off course at sea and somehow ended up in Odessa, Ukraine.

Of course, as I’ve now learned, that’s only the start of things. These days, I get emails advertising a more detailed panel (for an additional fee), looking for genetic markers for disease and more obscure traits. I also receive the occasional one from someone who, through the company’s anonymous servers, thinks they may be related to me.

I don’t answer either of those. I have no desire to expand my family circle beyond what it already is.

As for the disease testing? Not interested. Yes, some genetic tests may be helpful in making better choices, but the majority, at least to me, are still a work in progress. We deal with both false negatives and false positives in medicine. I routinely discourage my patients from spending money on unproven testing and treatments and have no desire to do the same myself. Maybe someday it will be worth the additional dollars, but I’m not convinced it’s there.

Money is, for better or worse, the driving force for all technologies, medical and otherwise. Maybe my $99 investment will help pay dividends down the road for someone, but today it only resulted in a shoulder shrug and chuckle at what I already knew.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ve never been particularly curious about my genetic background. We have a pretty clear family history that I’m of central European and Russian descent, with my ancestors coming over in groups between 1900 and 1938.

Recently, my mother decided she wanted more genetic information on us, so she paid $99 for us to send saliva samples to a company that advertises such services.

A few weeks went by. You read about people who find out they have a genetic background that’s quite surprising. I began to wonder: Would there be some giant family history shocker when the results came in?

I’ve since spoken to others who had paid for this service and found most had the same experience. The test confirmed what was already well known, except for one friend whose results suggested a trace of Polynesian blood somewhere in his background. He believes this was likely artefactual, though he enjoys the idea that somewhere in history a Tongan warrior was blown off course at sea and somehow ended up in Odessa, Ukraine.

Of course, as I’ve now learned, that’s only the start of things. These days, I get emails advertising a more detailed panel (for an additional fee), looking for genetic markers for disease and more obscure traits. I also receive the occasional one from someone who, through the company’s anonymous servers, thinks they may be related to me.

I don’t answer either of those. I have no desire to expand my family circle beyond what it already is.

As for the disease testing? Not interested. Yes, some genetic tests may be helpful in making better choices, but the majority, at least to me, are still a work in progress. We deal with both false negatives and false positives in medicine. I routinely discourage my patients from spending money on unproven testing and treatments and have no desire to do the same myself. Maybe someday it will be worth the additional dollars, but I’m not convinced it’s there.

Money is, for better or worse, the driving force for all technologies, medical and otherwise. Maybe my $99 investment will help pay dividends down the road for someone, but today it only resulted in a shoulder shrug and chuckle at what I already knew.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How to work with specialists in value-based care

The typical primary care physician has a patient base that consumes $10 million of health care a year. Yet the PCP receives only 6%-7% of those payments, with the rest of the costs resulting largely from the PCP’s referrals or lack of PCP care management of that patient.

The average PCP makes 1,000 referrals a year. Often, the referee specialist or facility not only does not coordinate with the PCP’s patient-centered medical home, they make their own downstream referrals.

A revolution in your compensation is underway. Under MACRA and other accountable care models, providers across the continuum of care are now being held responsible for the overall costs of those patients, not just their charges.

This is still hard to grasp, isn’t it? I was recently talking to a preeminent primary care physician who was an active member of an accountable care organization board of directors. I was fairly excited about the new impact this highly professional community leader could have on patients, now that he was in the PCP-driven ACO, not to mention his shared savings payment opportunities.

I was on a roll until he said, “But Bo, I’m already as efficient in treating patients as I can get.” He was still fighting the barriers you all face to do the best he could under the circumstances for the patients in his office each day.

Later, however, on a better day for me, we were working together on a cardiac care white paper. The physician leader told me, “I get it now – the biggest value-adding impact I might have is for the patient I don’t ever see.”

The above statistics show just what an opportunity you have in the new value care.

You can legally control referrals and patient care coordination with specialists. They don’t have to be in your ACO. You don’t even need to be in an ACO to take advantage of high-value referrals under the Medicare Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program under MACRA. But how?

Let’s start by assuming the specialist you need to refer to is not in your ACO. You might be able to do this without an ACO, but it’s hard to get the critical mass of primary care physicians. If you’re under the Medicare Shared Savings Program or Next Gen initiative, there are important Stark Law and antikickback liability waivers that would benefit you by being in an ACO.

Otherwise, you should consider a high-value referral affiliation agreement.

If a critical mass of primary care physicians can access data that create a short list of high-value specialists, they can put them on the high-value specialist list. Specialists do not need to get part of the shared savings pool or other financial incentives – just referrals because of their high-quality and high-efficiency care. A superstar specialist or acute care or post–acute care facility may ultimately be invited into the ACO as a full participant.

The specialist/facility basically agrees to coordinate all care with the medical home and comanage that care with you. The agreement specifies that they will observe the care protocols of the ACO for that disease state. The provider will share data and agree to be monitored.

What is a high-value specialist/facility? The current common approach is to look at the insurance companies’ top tiers, but they are often too weighted to allowed charges. It’s really about being care coordinators and about readmission and complication rates.

For example, some bundled-payment specialists are selected solely based on the surgeons’ and anesthesiologists’ complication rates. If fees are mentioned at all, they are well down the list.

Of course, if the specialist is in the ACO with the primary care physician, this can be done internally.

How do you find value-added protocols involving specialists? I was lucky to be on a multiyear grant program whereby I worked with many primary care physicians and specialists to create white papers setting out high-value, practical initiatives. There are also guides for internists and family physicians. A condition of the grant was that they all can be accessed free of charge; they’re available at www.tac-consortium.org/resources.

This is a new day. Primary care is being asked to lead health care delivery today and be paid to do it. You are being rewarded or punished financially now based on the overall costs of your patients. You must have specialists and facilities coordinate with you in this new health care model. We have attempted to provide a road map to assist you on your journey.

Mr. Bobbitt is head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He is president of Value Health Partners, LLC, a health care strategic consulting company. He has years of experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected] or 919-821-6612.

The typical primary care physician has a patient base that consumes $10 million of health care a year. Yet the PCP receives only 6%-7% of those payments, with the rest of the costs resulting largely from the PCP’s referrals or lack of PCP care management of that patient.

The average PCP makes 1,000 referrals a year. Often, the referee specialist or facility not only does not coordinate with the PCP’s patient-centered medical home, they make their own downstream referrals.

A revolution in your compensation is underway. Under MACRA and other accountable care models, providers across the continuum of care are now being held responsible for the overall costs of those patients, not just their charges.

This is still hard to grasp, isn’t it? I was recently talking to a preeminent primary care physician who was an active member of an accountable care organization board of directors. I was fairly excited about the new impact this highly professional community leader could have on patients, now that he was in the PCP-driven ACO, not to mention his shared savings payment opportunities.

I was on a roll until he said, “But Bo, I’m already as efficient in treating patients as I can get.” He was still fighting the barriers you all face to do the best he could under the circumstances for the patients in his office each day.

Later, however, on a better day for me, we were working together on a cardiac care white paper. The physician leader told me, “I get it now – the biggest value-adding impact I might have is for the patient I don’t ever see.”

The above statistics show just what an opportunity you have in the new value care.

You can legally control referrals and patient care coordination with specialists. They don’t have to be in your ACO. You don’t even need to be in an ACO to take advantage of high-value referrals under the Medicare Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program under MACRA. But how?

Let’s start by assuming the specialist you need to refer to is not in your ACO. You might be able to do this without an ACO, but it’s hard to get the critical mass of primary care physicians. If you’re under the Medicare Shared Savings Program or Next Gen initiative, there are important Stark Law and antikickback liability waivers that would benefit you by being in an ACO.

Otherwise, you should consider a high-value referral affiliation agreement.

If a critical mass of primary care physicians can access data that create a short list of high-value specialists, they can put them on the high-value specialist list. Specialists do not need to get part of the shared savings pool or other financial incentives – just referrals because of their high-quality and high-efficiency care. A superstar specialist or acute care or post–acute care facility may ultimately be invited into the ACO as a full participant.

The specialist/facility basically agrees to coordinate all care with the medical home and comanage that care with you. The agreement specifies that they will observe the care protocols of the ACO for that disease state. The provider will share data and agree to be monitored.

What is a high-value specialist/facility? The current common approach is to look at the insurance companies’ top tiers, but they are often too weighted to allowed charges. It’s really about being care coordinators and about readmission and complication rates.

For example, some bundled-payment specialists are selected solely based on the surgeons’ and anesthesiologists’ complication rates. If fees are mentioned at all, they are well down the list.

Of course, if the specialist is in the ACO with the primary care physician, this can be done internally.

How do you find value-added protocols involving specialists? I was lucky to be on a multiyear grant program whereby I worked with many primary care physicians and specialists to create white papers setting out high-value, practical initiatives. There are also guides for internists and family physicians. A condition of the grant was that they all can be accessed free of charge; they’re available at www.tac-consortium.org/resources.

This is a new day. Primary care is being asked to lead health care delivery today and be paid to do it. You are being rewarded or punished financially now based on the overall costs of your patients. You must have specialists and facilities coordinate with you in this new health care model. We have attempted to provide a road map to assist you on your journey.

Mr. Bobbitt is head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He is president of Value Health Partners, LLC, a health care strategic consulting company. He has years of experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected] or 919-821-6612.

The typical primary care physician has a patient base that consumes $10 million of health care a year. Yet the PCP receives only 6%-7% of those payments, with the rest of the costs resulting largely from the PCP’s referrals or lack of PCP care management of that patient.

The average PCP makes 1,000 referrals a year. Often, the referee specialist or facility not only does not coordinate with the PCP’s patient-centered medical home, they make their own downstream referrals.

A revolution in your compensation is underway. Under MACRA and other accountable care models, providers across the continuum of care are now being held responsible for the overall costs of those patients, not just their charges.

This is still hard to grasp, isn’t it? I was recently talking to a preeminent primary care physician who was an active member of an accountable care organization board of directors. I was fairly excited about the new impact this highly professional community leader could have on patients, now that he was in the PCP-driven ACO, not to mention his shared savings payment opportunities.

I was on a roll until he said, “But Bo, I’m already as efficient in treating patients as I can get.” He was still fighting the barriers you all face to do the best he could under the circumstances for the patients in his office each day.

Later, however, on a better day for me, we were working together on a cardiac care white paper. The physician leader told me, “I get it now – the biggest value-adding impact I might have is for the patient I don’t ever see.”

The above statistics show just what an opportunity you have in the new value care.

You can legally control referrals and patient care coordination with specialists. They don’t have to be in your ACO. You don’t even need to be in an ACO to take advantage of high-value referrals under the Medicare Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program under MACRA. But how?

Let’s start by assuming the specialist you need to refer to is not in your ACO. You might be able to do this without an ACO, but it’s hard to get the critical mass of primary care physicians. If you’re under the Medicare Shared Savings Program or Next Gen initiative, there are important Stark Law and antikickback liability waivers that would benefit you by being in an ACO.

Otherwise, you should consider a high-value referral affiliation agreement.

If a critical mass of primary care physicians can access data that create a short list of high-value specialists, they can put them on the high-value specialist list. Specialists do not need to get part of the shared savings pool or other financial incentives – just referrals because of their high-quality and high-efficiency care. A superstar specialist or acute care or post–acute care facility may ultimately be invited into the ACO as a full participant.

The specialist/facility basically agrees to coordinate all care with the medical home and comanage that care with you. The agreement specifies that they will observe the care protocols of the ACO for that disease state. The provider will share data and agree to be monitored.

What is a high-value specialist/facility? The current common approach is to look at the insurance companies’ top tiers, but they are often too weighted to allowed charges. It’s really about being care coordinators and about readmission and complication rates.

For example, some bundled-payment specialists are selected solely based on the surgeons’ and anesthesiologists’ complication rates. If fees are mentioned at all, they are well down the list.

Of course, if the specialist is in the ACO with the primary care physician, this can be done internally.

How do you find value-added protocols involving specialists? I was lucky to be on a multiyear grant program whereby I worked with many primary care physicians and specialists to create white papers setting out high-value, practical initiatives. There are also guides for internists and family physicians. A condition of the grant was that they all can be accessed free of charge; they’re available at www.tac-consortium.org/resources.

This is a new day. Primary care is being asked to lead health care delivery today and be paid to do it. You are being rewarded or punished financially now based on the overall costs of your patients. You must have specialists and facilities coordinate with you in this new health care model. We have attempted to provide a road map to assist you on your journey.

Mr. Bobbitt is head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He is president of Value Health Partners, LLC, a health care strategic consulting company. He has years of experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected] or 919-821-6612.

Illness-induced PTSD is common, understudied

SAN FRANCISCO – Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms triggered by a life-threatening medical illness differ from the more common PTSD, the source of which is an external trauma such as an assault or natural disaster, according to Renee El-Gabalawy, PhD.

“This suggests implications for diagnostic classification. Maybe, in future editions of the DSM, we should think of this as a subtype of PTSD or potentially as a new diagnostic category, although it’s far too early to make any conclusions about that,” Dr. El-Gabalawy said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

It’s estimated that PTSD occurs in 12%-25% of people who experience a life-threatening medical event.

“This is a fairly staggering proportion of people, and unfortunately this is a very overlooked area in the PTSD literature, almost all of which has been done in critical care units or oncology settings,” said Dr. El-Gabalawy, a psychologist at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg.

She presented an analysis of data from the 2012-2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, in which a nationally representative sample composed of 36,309 U.S. adults were interviewed face to face, with the current DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD being applied using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Association Disabilities Interview Schedule–5 (AUDADIS-5).

A total of 1,779 subjects (4.9%) indicated they had experienced physician-diagnosed PTSD during the previous year. Of those, 6.5% said their PTSD was triggered by an acute life-threatening medical event. The rest were attributed to nonmedical trauma.

There were sharp demographic differences between the two groups. Individuals with medical illness–induced PTSD were older – 35 years old at onset of their first episode, compared with age 23 in the others – with later onset of their PTSD. They were more likely to be men: 45.7% were male, compared with 31.8% for subjects with nonmedical PTSD. Comorbid depression was present in 25.4% of those with medical illness–induced PTSD, and comorbid panic disorder was present in 17%, significantly lower than the 37% and 24.5% rates in individuals with other triggers of PTSD.

Quality of life as measured by the Short Form-12 was similar in the two groups, after the investigators controlled for the number of medical conditions patients had.

Of people with medical illness–induced PTSD, 41% attributed their PTSD to a digestive disease, most often inflammatory bowel disease. In contrast, a digestive condition was present in 19.2% of subjects with nonmedical trauma as the source of their PTSD. Thus, a serious digestive disorder was associated with a 2.4-times increased risk of medical illness–induced PTSD in an analysis adjusted for socioeconomic factors and number of health conditions. Cancer, which was the trigger for 16.1% of cases of medical illness–induced PTSD and which had a prevalence of 5.8% in those with nonmedical sources of PTSD, was associated with a 2.64-times increased risk of medical illness–related PTSD.

“Those odds ratios are quite high for a population-based sample. This was a very dramatic effect,” Dr. El-Gabalawy commented.

The two groups of participants with PTSD had similar intensity of core PTSD symptom clusters with the exception of negative mood/cognition, which figured more prominently in those with medical illness–induced PTSD.

“This is very much in line with my clinical experience, that what’s really predominant in these folks are the maladaptive cognitions, their fear about their future health trajectory,” she said. “I tend to use cognitive processing therapy in these patients. It really taps into those maladaptive cognitions, and I’ve found that my patients are very receptive to this. Cognitive processing therapy might be more advantageous in this situation than prolonged exposure therapy .”

Dr. El-Gabalawy said she is a fan of the Enduring Somatic Threat model of medical illness–induced PTSD developed by Donald Edmondson, PhD, of Columbia University in New York (Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014 Mar 5;8[3]:118-34).

“It aligns with the literature and my own clinical experience,” she explained.

Dr. Edmondson’s model draws conceptual distinctions between medical illness–induced PTSD and other causes of PTSD. In medical illness–related PTSD, the trauma has a somatic source, the trauma tends to be chronic, and intrusive thoughts tend to be future oriented and highly cognitive in nature.

“It’s not uncommon that I’ll hear my patients with medical illness–induced PTSD say, ‘I’m really scared my disease is going to get worse.’ And behavioral avoidance is really difficult. Whereas, in the traditional conceptualization of PTSD, the intrusions are often past oriented and elicited by external triggers. Behavioral avoidance of those triggers is possible, but, in illness-related PTSD, arousal is keyed to internal triggers, often somatic in nature, such as heart palpitations,” according to the psychologist.

Her study was supported by the Canadian National Institutes of Health Research and the University of Manitoba. She reported having no financial conflicts.

SAN FRANCISCO – Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms triggered by a life-threatening medical illness differ from the more common PTSD, the source of which is an external trauma such as an assault or natural disaster, according to Renee El-Gabalawy, PhD.

“This suggests implications for diagnostic classification. Maybe, in future editions of the DSM, we should think of this as a subtype of PTSD or potentially as a new diagnostic category, although it’s far too early to make any conclusions about that,” Dr. El-Gabalawy said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

It’s estimated that PTSD occurs in 12%-25% of people who experience a life-threatening medical event.

“This is a fairly staggering proportion of people, and unfortunately this is a very overlooked area in the PTSD literature, almost all of which has been done in critical care units or oncology settings,” said Dr. El-Gabalawy, a psychologist at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg.

She presented an analysis of data from the 2012-2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, in which a nationally representative sample composed of 36,309 U.S. adults were interviewed face to face, with the current DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD being applied using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Association Disabilities Interview Schedule–5 (AUDADIS-5).

A total of 1,779 subjects (4.9%) indicated they had experienced physician-diagnosed PTSD during the previous year. Of those, 6.5% said their PTSD was triggered by an acute life-threatening medical event. The rest were attributed to nonmedical trauma.

There were sharp demographic differences between the two groups. Individuals with medical illness–induced PTSD were older – 35 years old at onset of their first episode, compared with age 23 in the others – with later onset of their PTSD. They were more likely to be men: 45.7% were male, compared with 31.8% for subjects with nonmedical PTSD. Comorbid depression was present in 25.4% of those with medical illness–induced PTSD, and comorbid panic disorder was present in 17%, significantly lower than the 37% and 24.5% rates in individuals with other triggers of PTSD.

Quality of life as measured by the Short Form-12 was similar in the two groups, after the investigators controlled for the number of medical conditions patients had.

Of people with medical illness–induced PTSD, 41% attributed their PTSD to a digestive disease, most often inflammatory bowel disease. In contrast, a digestive condition was present in 19.2% of subjects with nonmedical trauma as the source of their PTSD. Thus, a serious digestive disorder was associated with a 2.4-times increased risk of medical illness–induced PTSD in an analysis adjusted for socioeconomic factors and number of health conditions. Cancer, which was the trigger for 16.1% of cases of medical illness–induced PTSD and which had a prevalence of 5.8% in those with nonmedical sources of PTSD, was associated with a 2.64-times increased risk of medical illness–related PTSD.

“Those odds ratios are quite high for a population-based sample. This was a very dramatic effect,” Dr. El-Gabalawy commented.

The two groups of participants with PTSD had similar intensity of core PTSD symptom clusters with the exception of negative mood/cognition, which figured more prominently in those with medical illness–induced PTSD.

“This is very much in line with my clinical experience, that what’s really predominant in these folks are the maladaptive cognitions, their fear about their future health trajectory,” she said. “I tend to use cognitive processing therapy in these patients. It really taps into those maladaptive cognitions, and I’ve found that my patients are very receptive to this. Cognitive processing therapy might be more advantageous in this situation than prolonged exposure therapy .”

Dr. El-Gabalawy said she is a fan of the Enduring Somatic Threat model of medical illness–induced PTSD developed by Donald Edmondson, PhD, of Columbia University in New York (Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014 Mar 5;8[3]:118-34).

“It aligns with the literature and my own clinical experience,” she explained.

Dr. Edmondson’s model draws conceptual distinctions between medical illness–induced PTSD and other causes of PTSD. In medical illness–related PTSD, the trauma has a somatic source, the trauma tends to be chronic, and intrusive thoughts tend to be future oriented and highly cognitive in nature.

“It’s not uncommon that I’ll hear my patients with medical illness–induced PTSD say, ‘I’m really scared my disease is going to get worse.’ And behavioral avoidance is really difficult. Whereas, in the traditional conceptualization of PTSD, the intrusions are often past oriented and elicited by external triggers. Behavioral avoidance of those triggers is possible, but, in illness-related PTSD, arousal is keyed to internal triggers, often somatic in nature, such as heart palpitations,” according to the psychologist.

Her study was supported by the Canadian National Institutes of Health Research and the University of Manitoba. She reported having no financial conflicts.

SAN FRANCISCO – Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms triggered by a life-threatening medical illness differ from the more common PTSD, the source of which is an external trauma such as an assault or natural disaster, according to Renee El-Gabalawy, PhD.

“This suggests implications for diagnostic classification. Maybe, in future editions of the DSM, we should think of this as a subtype of PTSD or potentially as a new diagnostic category, although it’s far too early to make any conclusions about that,” Dr. El-Gabalawy said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

It’s estimated that PTSD occurs in 12%-25% of people who experience a life-threatening medical event.

“This is a fairly staggering proportion of people, and unfortunately this is a very overlooked area in the PTSD literature, almost all of which has been done in critical care units or oncology settings,” said Dr. El-Gabalawy, a psychologist at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg.

She presented an analysis of data from the 2012-2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, in which a nationally representative sample composed of 36,309 U.S. adults were interviewed face to face, with the current DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD being applied using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Association Disabilities Interview Schedule–5 (AUDADIS-5).

A total of 1,779 subjects (4.9%) indicated they had experienced physician-diagnosed PTSD during the previous year. Of those, 6.5% said their PTSD was triggered by an acute life-threatening medical event. The rest were attributed to nonmedical trauma.

There were sharp demographic differences between the two groups. Individuals with medical illness–induced PTSD were older – 35 years old at onset of their first episode, compared with age 23 in the others – with later onset of their PTSD. They were more likely to be men: 45.7% were male, compared with 31.8% for subjects with nonmedical PTSD. Comorbid depression was present in 25.4% of those with medical illness–induced PTSD, and comorbid panic disorder was present in 17%, significantly lower than the 37% and 24.5% rates in individuals with other triggers of PTSD.

Quality of life as measured by the Short Form-12 was similar in the two groups, after the investigators controlled for the number of medical conditions patients had.

Of people with medical illness–induced PTSD, 41% attributed their PTSD to a digestive disease, most often inflammatory bowel disease. In contrast, a digestive condition was present in 19.2% of subjects with nonmedical trauma as the source of their PTSD. Thus, a serious digestive disorder was associated with a 2.4-times increased risk of medical illness–induced PTSD in an analysis adjusted for socioeconomic factors and number of health conditions. Cancer, which was the trigger for 16.1% of cases of medical illness–induced PTSD and which had a prevalence of 5.8% in those with nonmedical sources of PTSD, was associated with a 2.64-times increased risk of medical illness–related PTSD.

“Those odds ratios are quite high for a population-based sample. This was a very dramatic effect,” Dr. El-Gabalawy commented.

The two groups of participants with PTSD had similar intensity of core PTSD symptom clusters with the exception of negative mood/cognition, which figured more prominently in those with medical illness–induced PTSD.

“This is very much in line with my clinical experience, that what’s really predominant in these folks are the maladaptive cognitions, their fear about their future health trajectory,” she said. “I tend to use cognitive processing therapy in these patients. It really taps into those maladaptive cognitions, and I’ve found that my patients are very receptive to this. Cognitive processing therapy might be more advantageous in this situation than prolonged exposure therapy .”

Dr. El-Gabalawy said she is a fan of the Enduring Somatic Threat model of medical illness–induced PTSD developed by Donald Edmondson, PhD, of Columbia University in New York (Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014 Mar 5;8[3]:118-34).

“It aligns with the literature and my own clinical experience,” she explained.

Dr. Edmondson’s model draws conceptual distinctions between medical illness–induced PTSD and other causes of PTSD. In medical illness–related PTSD, the trauma has a somatic source, the trauma tends to be chronic, and intrusive thoughts tend to be future oriented and highly cognitive in nature.

“It’s not uncommon that I’ll hear my patients with medical illness–induced PTSD say, ‘I’m really scared my disease is going to get worse.’ And behavioral avoidance is really difficult. Whereas, in the traditional conceptualization of PTSD, the intrusions are often past oriented and elicited by external triggers. Behavioral avoidance of those triggers is possible, but, in illness-related PTSD, arousal is keyed to internal triggers, often somatic in nature, such as heart palpitations,” according to the psychologist.

Her study was supported by the Canadian National Institutes of Health Research and the University of Manitoba. She reported having no financial conflicts.

AT ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Individuals with PTSD and a serious digestive disease were 2.4-times more likely to have medical illness–induced PTSD than PTSD triggered by a nonmedical cause.

Data source: A cross-sectional study of a nationally representative sample of more than 36,000 U.S. adults, 4.9% of whom met DSM 5 criteria for PTSD.

Disclosures: The presenter reported no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the Canadian National Institutes of Health Research and the University of Manitoba.

Emergency department use by recently diagnosed cancer patients in California

In 2017 there will be nearly 1.7 million new cancer cases diagnosed, and over 600,000 cancer deaths in the Unites States.1 A 2013 Institute of Medicine report highlighted problems with the current quality of cancer care, including high costs and fragmentation of care.2 Other national reports have called for improvements in the overall quality of care and for reducing costly and possibly avoidable use of health services such as emergency department (ED) visits.3-6 Reduction of avoidable ED visits is often cited as a pathway to reduce costs by avoiding unnecessary tests and treatments that occur in the ED and subsequent hospital admissions.7,8

ED crowding, long waits, and unpredictable treatment environments can also make an ED visit an unpleasant experience for the patient. ED visits during cancer treatment can be particularly troubling and present health concerns for patients who are immunocompromised. In particular, cancer patients in the ED have been found to experience delays in the administration of analgesics, antiemetics, or antibiotics.9

Few studies have examined ED use or its associated predictors among cancer patients. Reports to date that have described ED use have focused on different cancers, which makes comparisons across studies difficult.10 Moreover, the time frames of interest and the type of event after which ED use is evaluated (ie, diagnosis or treatment) are inconsistent in the existing literature.10 Some studies quantifying ED use excluded patients admitted to the hospital after an ED visit.11,12 Taken together, these studies do not provide a clear overview of the extent of ED use by cancer patients or the amount of cancer-related care provided by EDs.

Patterns of ED use among cancer patients derived from large and generalizable samples may help inform providers about true risk factors for ED use. In addition, prioritizing new interventions and focusing future research on groups of patients who are at higher risk for preventable ED use could also improve overall care. To address these issues, accurate estimates of ED use among cancer patients are required.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe ED use across a range of cancers in a large population-based sample and to consider the timing of ED visits in relation to initial diagnosis. The findings could provide benchmark comparison data to inform future efforts to identify the subset of possibly preventable ED visits and to design interventions to address preventable ED use.

Material and methods

Data source

California’s Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) manages the patient discharge dataset (PDD) and the emergency department use (EDU) dataset, providing a high-quality source of information on inpatient and ED use in the state.13 A principal diagnosis and up to 24 secondary diagnoses are recorded in OSHPD datasets. The EDU dataset was used to identify treat-and-release ED visits, and the PDD was used to identify hospitalizations initiated in the ED. The California Cancer Registry (CCR) obtains demographic and diagnosis information for every new invasive cancer diagnosed in California, and data collected by the registry are considered to be complete.14 CCR-OSPHD-linked data provide high-quality health care use information for cancer patients in California.15,16 Using an encrypted version of the social security number called the record linkage number (RLN), we linked the CCR records to the corresponding OSHPD files from 2009-2010.

Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained from the University of California, Davis, Human Subjects Committee and the State of California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Analysis

ED visits. Visits were included if they occurred on or up to 365 days after the date of cancer diagnosis recorded in the CCR. The visits were coded in mutually exclusive groups as occurring within 30, 31-180, and 181-365 days of diagnosis. Subsequently, we flagged each person as having any ED visit (Yes/No) within 180 days and within 365 days of diagnosis, and we tallied the total number of visits occurring within these time frames for each person.

Cancer type. We used relevant site and histology codes to classify cancer type into 24 mutually exclusive categories using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result‘s International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition (ICD-O-3) Recode Definitions17-19 (Suppl Figure 1).

Individual-level variables. Sociodemographic information for each person was collected from the CCR including gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, health insurance status, rural residence, survival time in months, neighborhood socio-economic (SES) status based on the Yang index, and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage.20,21

Data analysis

Demographic information was analyzed for the cohort using descriptive statistics (frequencies, proportions, means, standard deviations, and ranges) and evaluated for correlations. Fewer than 20 observations had missing data and we removed those observations from our analyses on an item-specific basis.

We tabulated ED visits by cancer type and time from diagnosis and then collapsed visit-level data by RLN to determine the number of ED visits for each person in the sample. The number of days from diagnosis to first ED visit was also tabulated. The cohort was stratified by cancer type and cumulative rates of ED visits were tabulated for individuals with ED visits within 0-180 and 0-365 days from diagnosis. To test the robustness of the findings adjusting for confounding factors known to impact ED use, we used logistic regression to model any ED use (Yes/No) as a function of age, gender, race/ethnicity, cancer stage, insurance status, marital status, urban residence, and Yang SES. After model estimation, we used the method of recycled predictions controlling for the confounding variables to compute the marginal probabilities of ED use by cancer type.22 To adjust for the possible impact of survival on ED use, we performed sensitivity analyses and estimated predicted probabilities adjusting for survival. Separate analyses were performed first adjusting for whether the patient died during the course of each month after diagnosis and then adjusting for whether or not the patient died within 180 days of diagnosis. All analyses were conducted using Stata 13.1.23

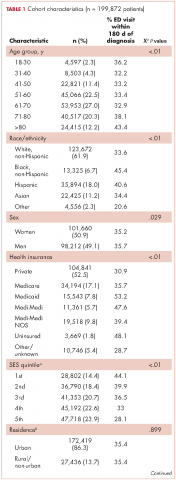

Results

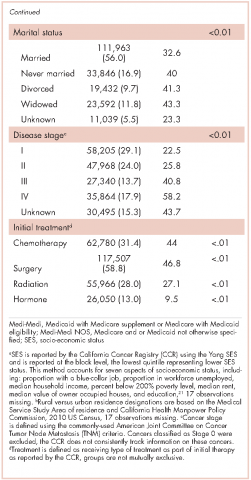

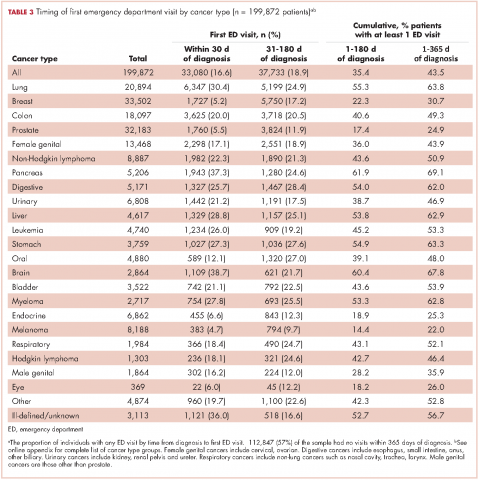

The CCR identified 222,087 adults with a new primary cancer diagnosis in 2009-2010. After excluding those with Stage 0 cancer (n = 21,154) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (n = 1,031), for whom data are inconsistently collected by CCR, a total of 199,872 individuals were included in the analytic sample. Of those patients (Table 1), most were white non-Hispanic (62%), women (51%), holders of private insurance (53%), married (56%), and urban residents (86%). Most were older than 50 years and had either Stage I or Stage II cancer. The most common cancer types were breast (17%), prostate (16%), lung (11%), and colon (9%; results not shown). In unadjusted comparisons, the incidence of ED use was significantly higher among those who were older, of non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity, uninsured, in the lowest SES group, widowed, or diagnosed with Stage IV cancer (Table 1).

ED visits

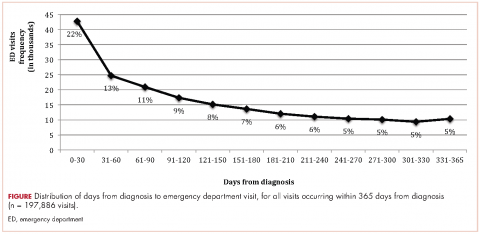

Within 365 days after initial cancer diagnosis, 87,025 cancer patients made a total of 197,886 ED visits (not shown in tables). Of those visits, 68% (n = 134,556) occurred within 180 days of diagnosis, with 22% (n = 43,535) occurring within the first 30 days and 46% (n = 91,027) occurring within 31-180 days after diagnosis (Figure). Given that most of the visits occurred within 180 days of diagnosis, we used that time frame in subsequent analyses. Among all ED visits within 180 days of diagnosis (Table 2), the largest proportions of visits were made by those with lung cancer (16%), breast cancer (11%), and colon cancer (10%).

About 51% of visits resulted in admission to the hospital and 45% in discharge (Table 2). For some cancers (lung, colon, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, pancreatic, digestive, liver, stomach, leukemia, and myeloma) most of the visits resulted in admission to the hospital (Table 2). Among visits resulting in admission, the top three principal diagnoses were: septicemia (8%), cardiovascular problems (7%), and complications from surgery (5%) (not shown in tables). Among visits resulting in a discharge home, the three top principal diagnoses were abdominal pain (7%), cardiovascular problems (6%), and urinary, kidney, and bladder complaints other than a urinary tract infection (5%) (results not shown).

Individuals

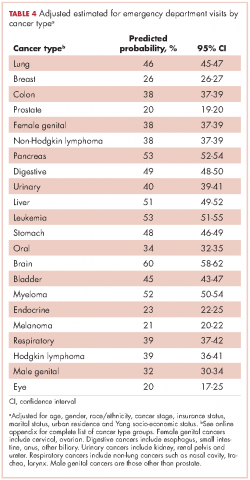

The cumulative incidence of at least one ED visit was 35% (n = 70,813) within 180 days after diagnosis (Table 3). Visit rates varied by cancer type: individuals with pancreatic (62%), brain (60%), and lung (55%) cancers had the highest cumulative incidences of ED use within 180 days of diagnosis (Table 3). Those with melanoma (14%), prostate (17%), and eye (18%) cancers had the lowest cumulative incidences of ED visits (Table 3).

Recycled predictions from logistic regression models, accounting for potential confounding factors, yielded substantively similar results for the cumulative incidence of ED use across cancer types (Table 4). Results did not differ substantially after accounting for survival. Differences in the predicted probability of an ED visits adjusting for death within 180 days of diagnosis were noted to be 2% or greater from estimates reported in Table 4 for only four cancers. Estimates of having any ED visits for those with lung cancer decreased from 46% to 44% (95% CI: 43.0-44.4%), pancreatic cancer from 53% to 49% (95% CI: 48-51%), liver cancer from 51% to 47% (95% CI: 49-53%), and those with eye cancers increased from 20% to 22% (95% CI: 18-26%) (not shown in tables).

For patients with certain cancers (eg, lung, pancreas, leukemia) the proportion of individuals with an initial ED visit was highest in the first 30 days after diagnosis (Table 3). For individuals with other cancers (eg, breast, prostate, melanoma) the proportion of individuals with an initial ED visit increased by more than 5% during the 31-181–day time period. Those with the remaining cancers had less than 5% change in cumulative ED use between the two time periods.

The number of visits per person ranged from 0-44 during the first 180 days after diagnosis (results not shown in tables). Of all patients diagnosed with cancer, 20% (n = 39,429) had one ED visit, 8% (n = 16,238) had two visits, and 7% (n = 14,760) had three or more visits. Of those patients having at least one ED visit within 180 days of diagnosis, 44% (n = 31,080) had two or more visits and 21% (n = 14,760) had 3 or more visits.

Discussion