User login

2018 AGA Fellows Program now accepting applications

The application period for the 2018 AGA Fellows Program is now open. The program recognizes members whose accomplishments demonstrate personal commitment to the field of gastroenterology with the distinction of fellowship.

AGA Fellows receive this honor from AGA for their superior professional achievement in clinical private or academic practice and in basic or clinical research.

AGA Fellows receive:

- The privilege of using the designation “AGAF” in professional activities.

- An official certificate and pin denoting your status.

- A listing on the AGA website.

And more.

Apply today to join this international community of excellence.

Find more information, including the list of benefits and criteria for fellowship, at www.gastro.org/fellowship. The deadline for application submissions is Monday, July 31, 2017.

The application period for the 2018 AGA Fellows Program is now open. The program recognizes members whose accomplishments demonstrate personal commitment to the field of gastroenterology with the distinction of fellowship.

AGA Fellows receive this honor from AGA for their superior professional achievement in clinical private or academic practice and in basic or clinical research.

AGA Fellows receive:

- The privilege of using the designation “AGAF” in professional activities.

- An official certificate and pin denoting your status.

- A listing on the AGA website.

And more.

Apply today to join this international community of excellence.

Find more information, including the list of benefits and criteria for fellowship, at www.gastro.org/fellowship. The deadline for application submissions is Monday, July 31, 2017.

The application period for the 2018 AGA Fellows Program is now open. The program recognizes members whose accomplishments demonstrate personal commitment to the field of gastroenterology with the distinction of fellowship.

AGA Fellows receive this honor from AGA for their superior professional achievement in clinical private or academic practice and in basic or clinical research.

AGA Fellows receive:

- The privilege of using the designation “AGAF” in professional activities.

- An official certificate and pin denoting your status.

- A listing on the AGA website.

And more.

Apply today to join this international community of excellence.

Find more information, including the list of benefits and criteria for fellowship, at www.gastro.org/fellowship. The deadline for application submissions is Monday, July 31, 2017.

Dual-task walking test may be effective dementia predictor

Poor performance in dual-task gait testing was significantly associated with dementia progression in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), according to a small prospective study.

The dementia prediction model could provide clinicians with a minimally invasive, low-cost analysis tool for patients with MCI and a compass to help guide decisions for further testing, according to Manuel Montero-Odasso, MD, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Western Ontario, London, and his colleagues.

In a study of 112 patients with MCI who were part of the Gait and Brain Study, investigators measured patients’ walking speed while only focusing on walking and then again while walking and counting backward from 100 by ones, counting backward from 100 by 7, or naming animals. The percentage difference between patients’ single-test walking speed and the dual-task speed was the dual-task gait cost. Patients received a biannual follow-up over a 6-year period.

Investigators found that higher gait costs in the dual gait test involving either counting backward by ones or naming animals were associated with a significantly increased risk of progression to dementia (JAMA Neurol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0643).

“Our sensitivity analysis showed that dual-task gait was comparable with cognitive testing to predict incident dementia,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso. “Clinicians may use dual-task gait testing in screening patients with MCI who could benefit the most from additional testing, optimizing recommendations for imaging, spinal fluid examinations, and genetic testing.”

Patients were an average of 75 years old, with an even distribution of men and women. Patients had an average of five comorbidities, most common among them hypertension (60.4%) and history of smoking (56.1%). Of the 112 participants, 24% progressed to dementia, an incidence rate of 121 per 1,000 person-years. A total of 39% of the study participants carried an APOE e4 allele.

Investigators confirmed the presence of MCI by evaluating patients’ levels of cognitive challenges, impairment in memory, executive function, attention, language, certain living activities, and an absence of dementia using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

When comparing the three dual-task gait tests, researchers found that higher gait cost when asking patients to count backward by ones or name animals presented a 3.8 times (P = .003) and 2.4 times (P = .04), respectively, increased risk of dementia progression. Gait cost when counting from 100 by sevens wasn’t significantly associated with dementia risk.

The researchers said that they still do not understand completely the relationship between walking velocity and cognitive function, although they hypothesized the connection may have to do with shared networks in the brain.

“What does seem clear is that executive demands used for gait and for the selected cognitive tasks may share a similar pathogenic mechanism at the brain level,” according to Dr. Montero-Odasso and his fellow investigators. “Episodic memory, a cognitive domain that was affected in all of our participants who progressed to dementia, relies on frontal-hippocampal circuits that are also central for gait control.”

The study was limited by the small population size, causing investigators to conclude that their findings are only generalizable at a clinic-based level. The investigators also noted the need for cross-validation in other MCI cohorts.

The model would be accessible for clinicians and researchers alike when identifying high-risk patients, designing further testing strategies, or planning primary prevention or intervention studies by more easily selecting patients with a greater risk of dementia progression, Dr. Montero-Odasso and his peers asserted.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research funded the study. One of the authors reported having been a part-time employee of Pfizer and owning employee stock options. The investigators reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Poor performance in dual-task gait testing was significantly associated with dementia progression in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), according to a small prospective study.

The dementia prediction model could provide clinicians with a minimally invasive, low-cost analysis tool for patients with MCI and a compass to help guide decisions for further testing, according to Manuel Montero-Odasso, MD, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Western Ontario, London, and his colleagues.

In a study of 112 patients with MCI who were part of the Gait and Brain Study, investigators measured patients’ walking speed while only focusing on walking and then again while walking and counting backward from 100 by ones, counting backward from 100 by 7, or naming animals. The percentage difference between patients’ single-test walking speed and the dual-task speed was the dual-task gait cost. Patients received a biannual follow-up over a 6-year period.

Investigators found that higher gait costs in the dual gait test involving either counting backward by ones or naming animals were associated with a significantly increased risk of progression to dementia (JAMA Neurol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0643).

“Our sensitivity analysis showed that dual-task gait was comparable with cognitive testing to predict incident dementia,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso. “Clinicians may use dual-task gait testing in screening patients with MCI who could benefit the most from additional testing, optimizing recommendations for imaging, spinal fluid examinations, and genetic testing.”

Patients were an average of 75 years old, with an even distribution of men and women. Patients had an average of five comorbidities, most common among them hypertension (60.4%) and history of smoking (56.1%). Of the 112 participants, 24% progressed to dementia, an incidence rate of 121 per 1,000 person-years. A total of 39% of the study participants carried an APOE e4 allele.

Investigators confirmed the presence of MCI by evaluating patients’ levels of cognitive challenges, impairment in memory, executive function, attention, language, certain living activities, and an absence of dementia using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

When comparing the three dual-task gait tests, researchers found that higher gait cost when asking patients to count backward by ones or name animals presented a 3.8 times (P = .003) and 2.4 times (P = .04), respectively, increased risk of dementia progression. Gait cost when counting from 100 by sevens wasn’t significantly associated with dementia risk.

The researchers said that they still do not understand completely the relationship between walking velocity and cognitive function, although they hypothesized the connection may have to do with shared networks in the brain.

“What does seem clear is that executive demands used for gait and for the selected cognitive tasks may share a similar pathogenic mechanism at the brain level,” according to Dr. Montero-Odasso and his fellow investigators. “Episodic memory, a cognitive domain that was affected in all of our participants who progressed to dementia, relies on frontal-hippocampal circuits that are also central for gait control.”

The study was limited by the small population size, causing investigators to conclude that their findings are only generalizable at a clinic-based level. The investigators also noted the need for cross-validation in other MCI cohorts.

The model would be accessible for clinicians and researchers alike when identifying high-risk patients, designing further testing strategies, or planning primary prevention or intervention studies by more easily selecting patients with a greater risk of dementia progression, Dr. Montero-Odasso and his peers asserted.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research funded the study. One of the authors reported having been a part-time employee of Pfizer and owning employee stock options. The investigators reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Poor performance in dual-task gait testing was significantly associated with dementia progression in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), according to a small prospective study.

The dementia prediction model could provide clinicians with a minimally invasive, low-cost analysis tool for patients with MCI and a compass to help guide decisions for further testing, according to Manuel Montero-Odasso, MD, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Western Ontario, London, and his colleagues.

In a study of 112 patients with MCI who were part of the Gait and Brain Study, investigators measured patients’ walking speed while only focusing on walking and then again while walking and counting backward from 100 by ones, counting backward from 100 by 7, or naming animals. The percentage difference between patients’ single-test walking speed and the dual-task speed was the dual-task gait cost. Patients received a biannual follow-up over a 6-year period.

Investigators found that higher gait costs in the dual gait test involving either counting backward by ones or naming animals were associated with a significantly increased risk of progression to dementia (JAMA Neurol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0643).

“Our sensitivity analysis showed that dual-task gait was comparable with cognitive testing to predict incident dementia,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso. “Clinicians may use dual-task gait testing in screening patients with MCI who could benefit the most from additional testing, optimizing recommendations for imaging, spinal fluid examinations, and genetic testing.”

Patients were an average of 75 years old, with an even distribution of men and women. Patients had an average of five comorbidities, most common among them hypertension (60.4%) and history of smoking (56.1%). Of the 112 participants, 24% progressed to dementia, an incidence rate of 121 per 1,000 person-years. A total of 39% of the study participants carried an APOE e4 allele.

Investigators confirmed the presence of MCI by evaluating patients’ levels of cognitive challenges, impairment in memory, executive function, attention, language, certain living activities, and an absence of dementia using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

When comparing the three dual-task gait tests, researchers found that higher gait cost when asking patients to count backward by ones or name animals presented a 3.8 times (P = .003) and 2.4 times (P = .04), respectively, increased risk of dementia progression. Gait cost when counting from 100 by sevens wasn’t significantly associated with dementia risk.

The researchers said that they still do not understand completely the relationship between walking velocity and cognitive function, although they hypothesized the connection may have to do with shared networks in the brain.

“What does seem clear is that executive demands used for gait and for the selected cognitive tasks may share a similar pathogenic mechanism at the brain level,” according to Dr. Montero-Odasso and his fellow investigators. “Episodic memory, a cognitive domain that was affected in all of our participants who progressed to dementia, relies on frontal-hippocampal circuits that are also central for gait control.”

The study was limited by the small population size, causing investigators to conclude that their findings are only generalizable at a clinic-based level. The investigators also noted the need for cross-validation in other MCI cohorts.

The model would be accessible for clinicians and researchers alike when identifying high-risk patients, designing further testing strategies, or planning primary prevention or intervention studies by more easily selecting patients with a greater risk of dementia progression, Dr. Montero-Odasso and his peers asserted.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research funded the study. One of the authors reported having been a part-time employee of Pfizer and owning employee stock options. The investigators reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Greater changes in the walking speeds of patients as they counted backward (hazard ratio, 3.79; P = .003) or named animals (HR, 2.41; P = .04) were associated with increased risk of progression to dementia.

Data source: A prospective cohort study of 122 MCI patients enrolled in the Gait and Brain Study, with follow-up reports gathered between July 2007 and March 2016.

Disclosures: The Canadian Institutes of Health Research funded the study. One of the authors reported having been a part-time employee of Pfizer and owning employee stock options. The investigators reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

Systemic Interferon Alfa Injections for the Treatment of a Giant Orf

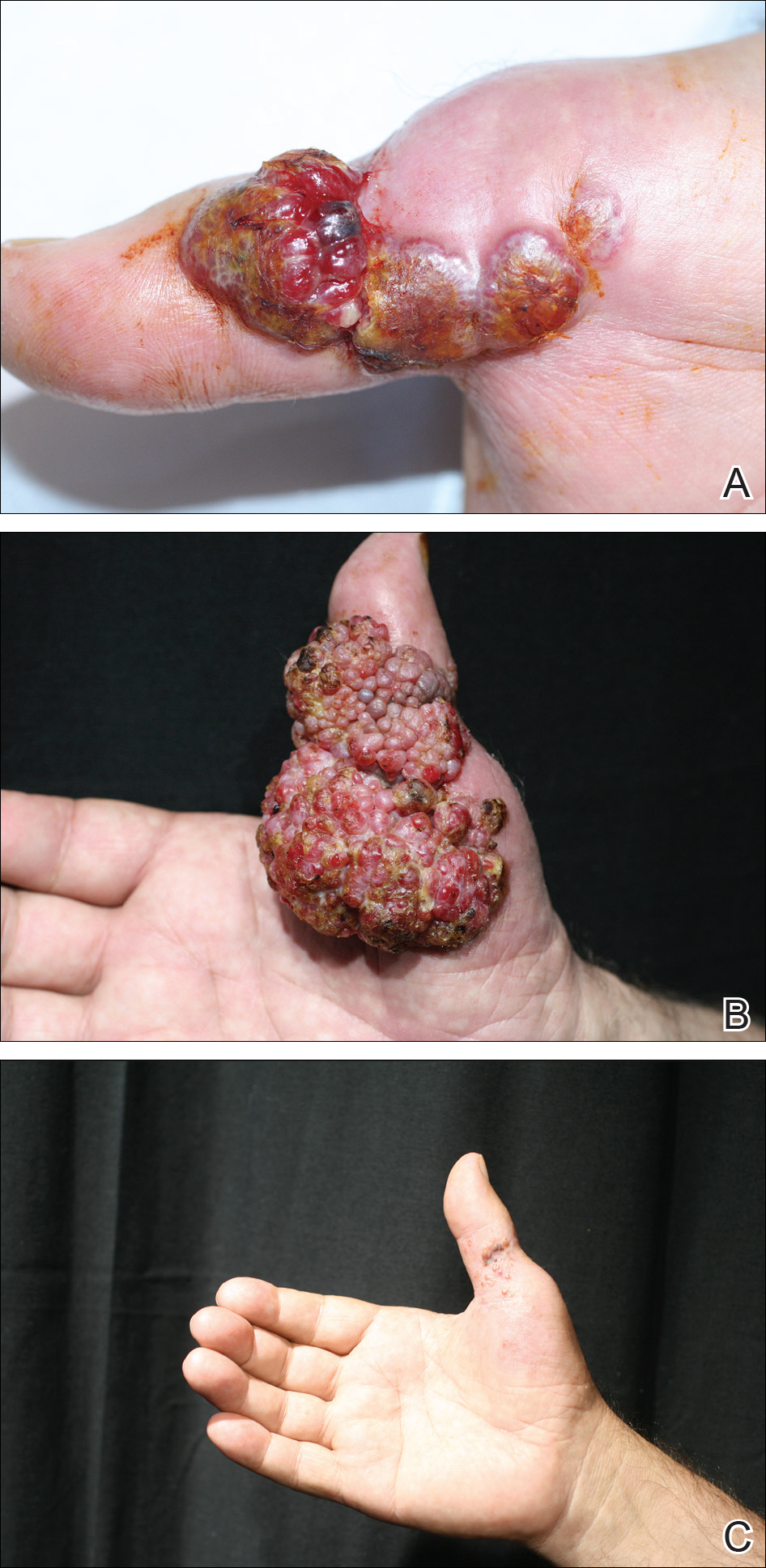

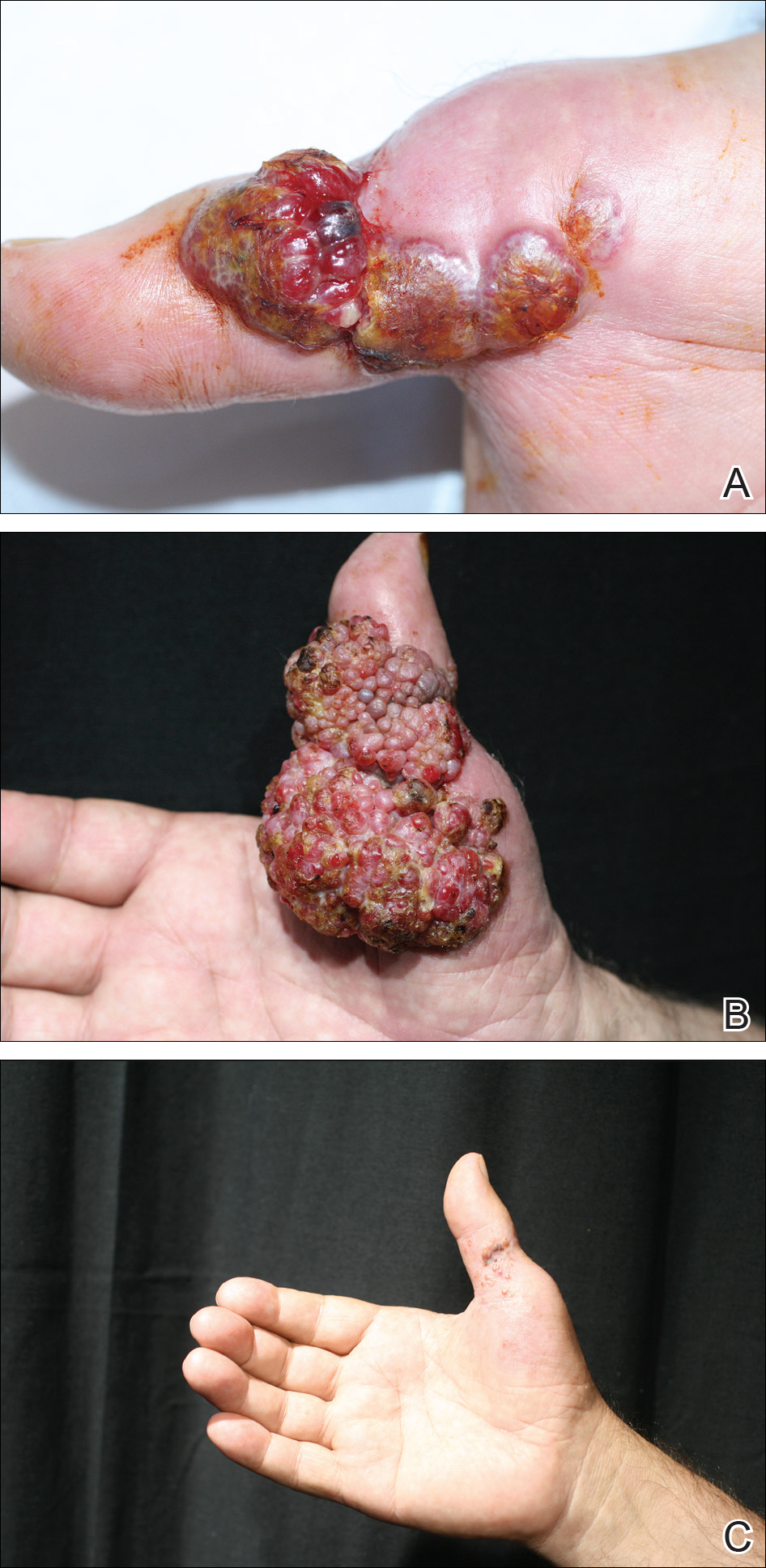

Orf, also known as ecthyma contagiosum, is a common viral zoonotic infection caused by a parapoxvirus. It is widespread among small ruminants such as sheep and goats, and it can be transmitted to humans by close contact with infected animals or contaminated fomites. It usually manifests as vesiculoulcerative lesions or nodules on the inoculation sites, mostly on the hands, but other sites such as the head and scalp occasionally may be involved.1 We report the case of an orf that proliferated dramatically and became giant after total excision. It was successfully treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections and imiquimod cream.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging mass on the left hand that developed 4 weeks prior after close contact with a freshly slaughtered sheep during an Islamic holiday in Turkey. His medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which was diagnosed one year prior. The patient had been treated with systemic prednisolone and cyclophosphamide therapies, but his disease was in remission at the current presentation and he currently was not receiving any treatment. On physical examination, a 2-cm, exophytic, pinkish gray, weeping nodule was observed on the proximal aspect of the right thumb. Based on the clinical findings and typical anamnesis, a diagnosis of an orf was concluded. It was decided to monitor the patient without any intervention; however, because the lesion did not resolve and remained stable, he was referred to a plastic surgeon for surgical removal after 6 weeks of follow-up.

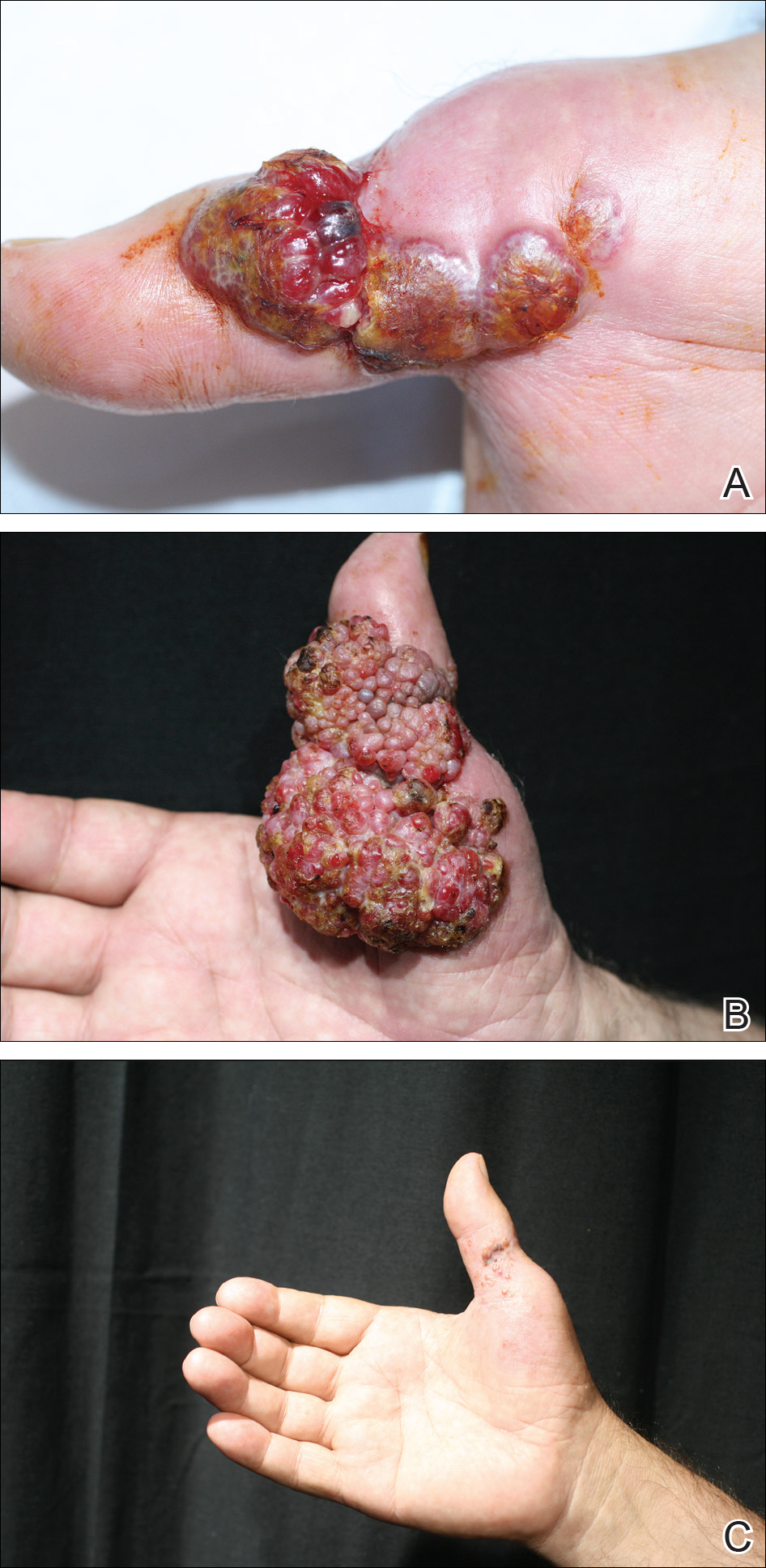

Histopathologic examination of the excision specimen revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, massive capillary proliferation, and viral cytopathic changes in keratinocytes characterized by ballooning degeneration and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, which was consistent with the clinical diagnosis of an orf. Unfortunately, the lesion relapsed rapidly following excision (Figure, A). Treatment with oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily) and imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) was initiated. However, this treatment was unsuccessful and was discontinued after 6 weeks, as the lesion kept growing, reaching a diameter of approximately 5 cm and becoming lobulated on the surface (Figure, B). Combination therapy was started with imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) and intralesional interferon alfa-2a injections (3 million IU twice weekly). The injections were so painful that the patient refused further therapy after only 2 injections. The therapy was switched from intralesional to systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon alfa-2a (3 million IU twice weekly) with concomitant imiquimod cream 5% 3 times weekly. This treatment was well tolerated by our patient with no notable side effects, except for mild fever on the night of each injection. Three weeks after the commencement of systemic injections, remarkable healing of the lesions with reduced size and exudation was noted. The frequency of injections was decreased to once weekly, which was then discontinued after 6 weeks when the lesion totally resolved (Figure, C). At 12 months’ follow-up, there were no signs of relapse.

Comment

Orf is an occupational disease that usually develops in farmers, butchers, and veterinarians; however, epidemic outbreaks of human orf are commonly observed in Turkey after the feast of sacrifice, as many individuals have close contact with the animals during sacrification.2 In Turkey, orf is well recognized by dermatologists, and clinical diagnosis usually is not difficult.

Human orf has a self-limited course in which lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, such as our patient with CLL, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant, requiring early and effective treatment. Treatment options for giant orf tumors in immunocompromised individuals include surgical excision,3 cryotherapy, topical imiquimod,4,5 topical or intralesional cidofovir,6 and intralesional interferon alfa injections.7 According to our clinical observations, surgical interventions for treatment of orfs usually cause a delay in the natural healing process; however, because surgical excision is a recommended treatment option for exophytic and recalcitrant orfs, we decided to treat our patient with surgical excision, which resulted in rapid recurrence and massive proliferation. A similar case of giant orf that was aggravated after surgery has been reported.8 In light of these cases, it is our opinion that treatment options other than surgery may be reasonable.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia may show features of both humoral and cell-mediated deficiency. Patients are known to be prone to viral infections such as varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and human papillomavirus. A giant orf infection on the background of CLL also has been described.9

Interferons were first discovered in 1957 and named after their ability to interfere with viral replication. They represent a family of cytokines that has an essential role in the innate immune response to virus infections. Because of their antiviral properties, recombinant forms of interferon alfa are widely used with success in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. A few other antiviral clinical applications of interferon alfa include infections caused by human herpesvirus 8 (the etiological agent in Kaposi sarcoma) and human papillomatosis virus (the etiological agent in juvenile laryngeal papillomatosis and condyloma acuminatum).10

In a report by Ran et al,7 intralesional interferon alfa injections were successfully used for treatment of giant orf lesions in an immunocompromised patient. As a result, we started treating the patient with intralesional interferon alfa-2a, but it was not well tolerated by our patient, as it was quite painful. We then decided to continue the therapy with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections, as we believed that it was a good option due to its antiviral, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenic properties. With the experimental combined therapy of systemic interferon alfa-2a and topical imiquimod, our patient achieved a complete response in 9 weeks (3 weeks of twice weekly injections and then 6 weeks of once weekly injections) and had no relapses during 12 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of a giant orf treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections. Because intralesional injections are quite painful, systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon might be a good and safe alternative for recalcitrant orf lesions in immunocompromised patients. However, more studies and reports are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.

The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

- Gurel MS, Ozardali I, Bitiren M, et al. Giant orf on the nose. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:183-185.

- Uzel M, Sasmaz S, Bakaris S, et al. A viral infection of the hand commonly seen after the feast of sacrifice: human orf (orf of the hand). Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:653-657.

- Ballanger F, Barbarot S, Mollat C, et al. Two giant orf lesions in a heart/lung transplant patient. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:284-286.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Lederman ER, Green GM, DeGroot HE, et al. Progressive ORF virus infection in a patient with lymphoma: successful treatment using imiquimod. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e100-e103.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma–like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Key SJ, Catania J, Mustafa SF, et al. Unusual presentation of human giant orf (ecthyma contagiosum). J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1076-1078.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Friedman RM. Clinical uses of interferons. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:158-162.

Orf, also known as ecthyma contagiosum, is a common viral zoonotic infection caused by a parapoxvirus. It is widespread among small ruminants such as sheep and goats, and it can be transmitted to humans by close contact with infected animals or contaminated fomites. It usually manifests as vesiculoulcerative lesions or nodules on the inoculation sites, mostly on the hands, but other sites such as the head and scalp occasionally may be involved.1 We report the case of an orf that proliferated dramatically and became giant after total excision. It was successfully treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections and imiquimod cream.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging mass on the left hand that developed 4 weeks prior after close contact with a freshly slaughtered sheep during an Islamic holiday in Turkey. His medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which was diagnosed one year prior. The patient had been treated with systemic prednisolone and cyclophosphamide therapies, but his disease was in remission at the current presentation and he currently was not receiving any treatment. On physical examination, a 2-cm, exophytic, pinkish gray, weeping nodule was observed on the proximal aspect of the right thumb. Based on the clinical findings and typical anamnesis, a diagnosis of an orf was concluded. It was decided to monitor the patient without any intervention; however, because the lesion did not resolve and remained stable, he was referred to a plastic surgeon for surgical removal after 6 weeks of follow-up.

Histopathologic examination of the excision specimen revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, massive capillary proliferation, and viral cytopathic changes in keratinocytes characterized by ballooning degeneration and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, which was consistent with the clinical diagnosis of an orf. Unfortunately, the lesion relapsed rapidly following excision (Figure, A). Treatment with oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily) and imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) was initiated. However, this treatment was unsuccessful and was discontinued after 6 weeks, as the lesion kept growing, reaching a diameter of approximately 5 cm and becoming lobulated on the surface (Figure, B). Combination therapy was started with imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) and intralesional interferon alfa-2a injections (3 million IU twice weekly). The injections were so painful that the patient refused further therapy after only 2 injections. The therapy was switched from intralesional to systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon alfa-2a (3 million IU twice weekly) with concomitant imiquimod cream 5% 3 times weekly. This treatment was well tolerated by our patient with no notable side effects, except for mild fever on the night of each injection. Three weeks after the commencement of systemic injections, remarkable healing of the lesions with reduced size and exudation was noted. The frequency of injections was decreased to once weekly, which was then discontinued after 6 weeks when the lesion totally resolved (Figure, C). At 12 months’ follow-up, there were no signs of relapse.

Comment

Orf is an occupational disease that usually develops in farmers, butchers, and veterinarians; however, epidemic outbreaks of human orf are commonly observed in Turkey after the feast of sacrifice, as many individuals have close contact with the animals during sacrification.2 In Turkey, orf is well recognized by dermatologists, and clinical diagnosis usually is not difficult.

Human orf has a self-limited course in which lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, such as our patient with CLL, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant, requiring early and effective treatment. Treatment options for giant orf tumors in immunocompromised individuals include surgical excision,3 cryotherapy, topical imiquimod,4,5 topical or intralesional cidofovir,6 and intralesional interferon alfa injections.7 According to our clinical observations, surgical interventions for treatment of orfs usually cause a delay in the natural healing process; however, because surgical excision is a recommended treatment option for exophytic and recalcitrant orfs, we decided to treat our patient with surgical excision, which resulted in rapid recurrence and massive proliferation. A similar case of giant orf that was aggravated after surgery has been reported.8 In light of these cases, it is our opinion that treatment options other than surgery may be reasonable.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia may show features of both humoral and cell-mediated deficiency. Patients are known to be prone to viral infections such as varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and human papillomavirus. A giant orf infection on the background of CLL also has been described.9

Interferons were first discovered in 1957 and named after their ability to interfere with viral replication. They represent a family of cytokines that has an essential role in the innate immune response to virus infections. Because of their antiviral properties, recombinant forms of interferon alfa are widely used with success in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. A few other antiviral clinical applications of interferon alfa include infections caused by human herpesvirus 8 (the etiological agent in Kaposi sarcoma) and human papillomatosis virus (the etiological agent in juvenile laryngeal papillomatosis and condyloma acuminatum).10

In a report by Ran et al,7 intralesional interferon alfa injections were successfully used for treatment of giant orf lesions in an immunocompromised patient. As a result, we started treating the patient with intralesional interferon alfa-2a, but it was not well tolerated by our patient, as it was quite painful. We then decided to continue the therapy with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections, as we believed that it was a good option due to its antiviral, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenic properties. With the experimental combined therapy of systemic interferon alfa-2a and topical imiquimod, our patient achieved a complete response in 9 weeks (3 weeks of twice weekly injections and then 6 weeks of once weekly injections) and had no relapses during 12 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of a giant orf treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections. Because intralesional injections are quite painful, systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon might be a good and safe alternative for recalcitrant orf lesions in immunocompromised patients. However, more studies and reports are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.

The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

Orf, also known as ecthyma contagiosum, is a common viral zoonotic infection caused by a parapoxvirus. It is widespread among small ruminants such as sheep and goats, and it can be transmitted to humans by close contact with infected animals or contaminated fomites. It usually manifests as vesiculoulcerative lesions or nodules on the inoculation sites, mostly on the hands, but other sites such as the head and scalp occasionally may be involved.1 We report the case of an orf that proliferated dramatically and became giant after total excision. It was successfully treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections and imiquimod cream.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging mass on the left hand that developed 4 weeks prior after close contact with a freshly slaughtered sheep during an Islamic holiday in Turkey. His medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which was diagnosed one year prior. The patient had been treated with systemic prednisolone and cyclophosphamide therapies, but his disease was in remission at the current presentation and he currently was not receiving any treatment. On physical examination, a 2-cm, exophytic, pinkish gray, weeping nodule was observed on the proximal aspect of the right thumb. Based on the clinical findings and typical anamnesis, a diagnosis of an orf was concluded. It was decided to monitor the patient without any intervention; however, because the lesion did not resolve and remained stable, he was referred to a plastic surgeon for surgical removal after 6 weeks of follow-up.

Histopathologic examination of the excision specimen revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, massive capillary proliferation, and viral cytopathic changes in keratinocytes characterized by ballooning degeneration and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, which was consistent with the clinical diagnosis of an orf. Unfortunately, the lesion relapsed rapidly following excision (Figure, A). Treatment with oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily) and imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) was initiated. However, this treatment was unsuccessful and was discontinued after 6 weeks, as the lesion kept growing, reaching a diameter of approximately 5 cm and becoming lobulated on the surface (Figure, B). Combination therapy was started with imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) and intralesional interferon alfa-2a injections (3 million IU twice weekly). The injections were so painful that the patient refused further therapy after only 2 injections. The therapy was switched from intralesional to systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon alfa-2a (3 million IU twice weekly) with concomitant imiquimod cream 5% 3 times weekly. This treatment was well tolerated by our patient with no notable side effects, except for mild fever on the night of each injection. Three weeks after the commencement of systemic injections, remarkable healing of the lesions with reduced size and exudation was noted. The frequency of injections was decreased to once weekly, which was then discontinued after 6 weeks when the lesion totally resolved (Figure, C). At 12 months’ follow-up, there were no signs of relapse.

Comment

Orf is an occupational disease that usually develops in farmers, butchers, and veterinarians; however, epidemic outbreaks of human orf are commonly observed in Turkey after the feast of sacrifice, as many individuals have close contact with the animals during sacrification.2 In Turkey, orf is well recognized by dermatologists, and clinical diagnosis usually is not difficult.

Human orf has a self-limited course in which lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, such as our patient with CLL, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant, requiring early and effective treatment. Treatment options for giant orf tumors in immunocompromised individuals include surgical excision,3 cryotherapy, topical imiquimod,4,5 topical or intralesional cidofovir,6 and intralesional interferon alfa injections.7 According to our clinical observations, surgical interventions for treatment of orfs usually cause a delay in the natural healing process; however, because surgical excision is a recommended treatment option for exophytic and recalcitrant orfs, we decided to treat our patient with surgical excision, which resulted in rapid recurrence and massive proliferation. A similar case of giant orf that was aggravated after surgery has been reported.8 In light of these cases, it is our opinion that treatment options other than surgery may be reasonable.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia may show features of both humoral and cell-mediated deficiency. Patients are known to be prone to viral infections such as varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and human papillomavirus. A giant orf infection on the background of CLL also has been described.9

Interferons were first discovered in 1957 and named after their ability to interfere with viral replication. They represent a family of cytokines that has an essential role in the innate immune response to virus infections. Because of their antiviral properties, recombinant forms of interferon alfa are widely used with success in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. A few other antiviral clinical applications of interferon alfa include infections caused by human herpesvirus 8 (the etiological agent in Kaposi sarcoma) and human papillomatosis virus (the etiological agent in juvenile laryngeal papillomatosis and condyloma acuminatum).10

In a report by Ran et al,7 intralesional interferon alfa injections were successfully used for treatment of giant orf lesions in an immunocompromised patient. As a result, we started treating the patient with intralesional interferon alfa-2a, but it was not well tolerated by our patient, as it was quite painful. We then decided to continue the therapy with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections, as we believed that it was a good option due to its antiviral, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenic properties. With the experimental combined therapy of systemic interferon alfa-2a and topical imiquimod, our patient achieved a complete response in 9 weeks (3 weeks of twice weekly injections and then 6 weeks of once weekly injections) and had no relapses during 12 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of a giant orf treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections. Because intralesional injections are quite painful, systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon might be a good and safe alternative for recalcitrant orf lesions in immunocompromised patients. However, more studies and reports are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.

The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

- Gurel MS, Ozardali I, Bitiren M, et al. Giant orf on the nose. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:183-185.

- Uzel M, Sasmaz S, Bakaris S, et al. A viral infection of the hand commonly seen after the feast of sacrifice: human orf (orf of the hand). Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:653-657.

- Ballanger F, Barbarot S, Mollat C, et al. Two giant orf lesions in a heart/lung transplant patient. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:284-286.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Lederman ER, Green GM, DeGroot HE, et al. Progressive ORF virus infection in a patient with lymphoma: successful treatment using imiquimod. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e100-e103.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma–like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Key SJ, Catania J, Mustafa SF, et al. Unusual presentation of human giant orf (ecthyma contagiosum). J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1076-1078.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Friedman RM. Clinical uses of interferons. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:158-162.

- Gurel MS, Ozardali I, Bitiren M, et al. Giant orf on the nose. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:183-185.

- Uzel M, Sasmaz S, Bakaris S, et al. A viral infection of the hand commonly seen after the feast of sacrifice: human orf (orf of the hand). Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:653-657.

- Ballanger F, Barbarot S, Mollat C, et al. Two giant orf lesions in a heart/lung transplant patient. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:284-286.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Lederman ER, Green GM, DeGroot HE, et al. Progressive ORF virus infection in a patient with lymphoma: successful treatment using imiquimod. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e100-e103.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma–like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Key SJ, Catania J, Mustafa SF, et al. Unusual presentation of human giant orf (ecthyma contagiosum). J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1076-1078.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Friedman RM. Clinical uses of interferons. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:158-162.

Resident Pearl

- Human orf lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant. We observed that surgical interventions for treatment of orfs cause a delay in the natural healing process, and other treatment options such as subcutaneous interferon alfa-2a may be used.

Few states fully support HCV prevention, treatment

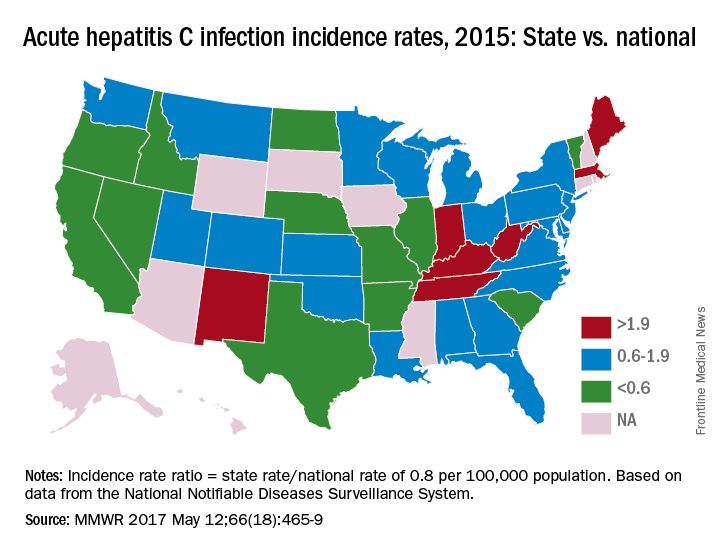

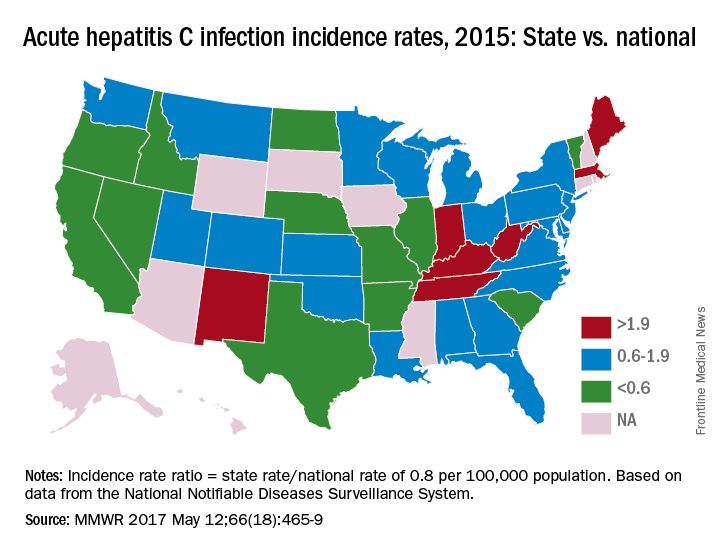

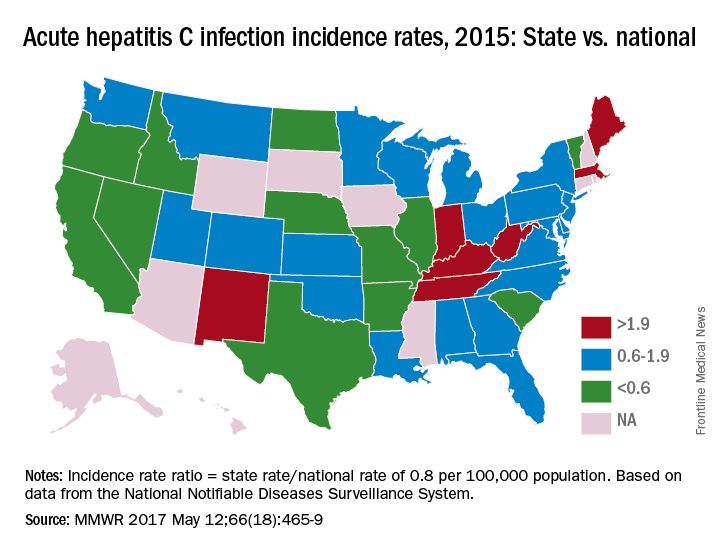

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The U.S. incidence of HCV jumped by 294% from 2010 to 2015, and “this increase in acute cases of HCV is largely attributed to injection drug use,” the CDC investigators said. Since state laws and policies affect access to HCV preventive and treatment measures, the researchers reviewed laws related to access to clean needles and policies on Medicaid fee-for-service treatment.

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

AGA Resource

The AGA HCV Clinical Service Line offers tools to help you become more efficient, understand quality standards and improve the process of care for patients. Read more at http://www.gastro.org/patient-care/conditions-diseases/hepatitis-c.

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The U.S. incidence of HCV jumped by 294% from 2010 to 2015, and “this increase in acute cases of HCV is largely attributed to injection drug use,” the CDC investigators said. Since state laws and policies affect access to HCV preventive and treatment measures, the researchers reviewed laws related to access to clean needles and policies on Medicaid fee-for-service treatment.

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

AGA Resource

The AGA HCV Clinical Service Line offers tools to help you become more efficient, understand quality standards and improve the process of care for patients. Read more at http://www.gastro.org/patient-care/conditions-diseases/hepatitis-c.

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The U.S. incidence of HCV jumped by 294% from 2010 to 2015, and “this increase in acute cases of HCV is largely attributed to injection drug use,” the CDC investigators said. Since state laws and policies affect access to HCV preventive and treatment measures, the researchers reviewed laws related to access to clean needles and policies on Medicaid fee-for-service treatment.

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

AGA Resource

The AGA HCV Clinical Service Line offers tools to help you become more efficient, understand quality standards and improve the process of care for patients. Read more at http://www.gastro.org/patient-care/conditions-diseases/hepatitis-c.

FROM MMWR

Lower Leg Fracture Irreducibility Resulting From Entrapment of the Fibula Within the Tibial Shaft

Take-Home Points

- Preoperative orthogonal radiographs need to be carefully scrutinized in irreducible fractures.

- Open reduction is often necessary when soft-tissue or bone is interposed in a fracture site.

- The fibula’s size and interosseous connection to the tibia can lead to entrapment.

- High-energy mechanisms can lead to significant deformity at time of injury, with spontaneous partial reduction prior to initial assessment.

- Consider intramedullary entrapment of adjacent long bones.

The tibia is the most commonly fractured long bone; each year, almost 500,000 tibia fractures occur in the United States alone.1 Low-energy mechanisms of injury usually result from torsional forces and produce less comminuted fractures. Very high-energy injuries apply direct forces to the shin and are often highly comminuted or open, owing to the limited soft-tissue envelope. The extent of soft-tissue injury occurring with these fractures is the best predictor of the development of a complication, particularly nonunion or infection.1 Low-energy closed fractures with limited comminution and sufficient cortical apposition may be treated with closed reduction and casting, but the most common treatment for tibial shaft fractures is intramedullary nailing.2

In the acute setting, closed reduction allows for temporization of soft tissues and prevention of further damage to neurovascular structures. Whether eventual treatment consists of casting or intramedullary fixation, closed reduction must first be achieved.

In this article, we report a unique case of tibial shaft fracture irreducibility caused by telescoping of the distal fibula within the proximal tibial diaphysis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 23-year-old unrestrained driver of a tow truck rear-ended another vehicle at high speed (~45 mph) and became trapped in the vehicle. Extrication time was prolonged. The driver was brought to the emergency department at a level I trauma center, where he was found to have an obvious closed deformity of the right lower leg but remained neurovascularly intact. Radiographs showed a highly comminuted fracture of the right tibial and fibular midshaft with more than 100% medial displacement of the distal fragment (Figure 1).

The next morning, the patient was taken to the operating room for planned closed intramedullary nailing through a suprapatellar approach. After entry to the tibial medullary canal was obtained, a ball-tipped guide wire was advanced proximal to the fracture site, until significant resistance was met. With the aid of intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging, it was determined that the distal fibula fracture segment was entrapped in the medullary canal of the proximal tibia (Figure 2).

After the fibula was liberated, additional closed manipulative reduction techniques were used on the tibia to restore length, alignment, and rotation, and an appropriately sized nail was advanced distally past the fracture segment and fixed with interlocking screws proximally and distally (Figure 4).

The postoperative course was uncomplicated. At most recent follow-up, radiographs showed near anatomical alignment, and the patient was back to normal activities without use of any pain medication or assistive device.

Discussion

Although other irreducible tibia fracture patterns have been described, midshaft tibia fracture irreducibility caused by entrapment of the fibula within the intramedullary space was a previously unreported difficulty of this very common fracture. More commonly, irreducible tibia fractures are caused by entrapment of soft-tissue structures or fracture fragments.3,4

There are no previous documented cases of fracture patterns in which one long bone telescopes into another. Although not previously reported as occurring traumatically, the fibula was previously used as a vascularized graft in the intramedullary canal of the tibia and elsewhere.

The most well described irreducible fracture-dislocation of the lower leg is the Bosworth type, in which the proximal fragment of the fibula becomes displaced behind the tibia at the ankle joint. In addition, because of the torsional nature of most ankle fractures and the multitude of accompanying soft-tissue structures crossing at the joint, entrapment leading to irreducibility has had several different causes. These soft-tissue entrapment injures are often difficult to distinguish on plain radiographs and require further definition by computed tomography.

The high-energy mechanism of injury we have described is thought to result from lateral translation of the upper portion of the leg with the foot and lower leg fixed in place. We can posit that momentary hypervarus angulation of the tibia and the fibula with subsequent spontaneous partial reduction caused by tissue elasticity could lead to this unique injury pattern.

Although this is the first reported case of entrapment of the fibula within the intramedullary canal of the tibia, the injury should be considered when difficult closed reductions are encountered. It was only after attempted reduction for intramedullary nailing in the operating room that the telescoping fibula and the irreducibility were identified, and open reduction performed. There were no soft-tissue or neurovascular complications, but, had there been, they could have become of urgent concern and altered treatment.

In this case report, we have described a unique fracture pattern that could cause significant morbidity if not appropriately identified and treated in a timely manner.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):E160-E162. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Karladani AH, Granhed H, Kärrholm J, Styf J. The influence of fracture etiology and type on fracture healing: a review of 104 consecutive tibial shaft fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121(6):325-328.

2. McGanity P. Tibial shaft fractures. In: Heckman JD, Schenck RC Jr, Agarwal A, eds. Current Orthopedic Diagnosis & Treatment. New York, NY: Springer; 2000:184-185.

3. Ermis MN, Yagmurlu MF, Kilinc AS, Karakas ES. Irreducible fracture dislocation of the ankle caused by tibialis posterior tendon interposition. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49(2):166-171.

4. Green RN, Pullagura MK, Holland JP. Irreducible fracture-dislocation of the knee. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48(3):363-366.

Take-Home Points

- Preoperative orthogonal radiographs need to be carefully scrutinized in irreducible fractures.

- Open reduction is often necessary when soft-tissue or bone is interposed in a fracture site.

- The fibula’s size and interosseous connection to the tibia can lead to entrapment.

- High-energy mechanisms can lead to significant deformity at time of injury, with spontaneous partial reduction prior to initial assessment.

- Consider intramedullary entrapment of adjacent long bones.

The tibia is the most commonly fractured long bone; each year, almost 500,000 tibia fractures occur in the United States alone.1 Low-energy mechanisms of injury usually result from torsional forces and produce less comminuted fractures. Very high-energy injuries apply direct forces to the shin and are often highly comminuted or open, owing to the limited soft-tissue envelope. The extent of soft-tissue injury occurring with these fractures is the best predictor of the development of a complication, particularly nonunion or infection.1 Low-energy closed fractures with limited comminution and sufficient cortical apposition may be treated with closed reduction and casting, but the most common treatment for tibial shaft fractures is intramedullary nailing.2

In the acute setting, closed reduction allows for temporization of soft tissues and prevention of further damage to neurovascular structures. Whether eventual treatment consists of casting or intramedullary fixation, closed reduction must first be achieved.

In this article, we report a unique case of tibial shaft fracture irreducibility caused by telescoping of the distal fibula within the proximal tibial diaphysis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 23-year-old unrestrained driver of a tow truck rear-ended another vehicle at high speed (~45 mph) and became trapped in the vehicle. Extrication time was prolonged. The driver was brought to the emergency department at a level I trauma center, where he was found to have an obvious closed deformity of the right lower leg but remained neurovascularly intact. Radiographs showed a highly comminuted fracture of the right tibial and fibular midshaft with more than 100% medial displacement of the distal fragment (Figure 1).

The next morning, the patient was taken to the operating room for planned closed intramedullary nailing through a suprapatellar approach. After entry to the tibial medullary canal was obtained, a ball-tipped guide wire was advanced proximal to the fracture site, until significant resistance was met. With the aid of intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging, it was determined that the distal fibula fracture segment was entrapped in the medullary canal of the proximal tibia (Figure 2).

After the fibula was liberated, additional closed manipulative reduction techniques were used on the tibia to restore length, alignment, and rotation, and an appropriately sized nail was advanced distally past the fracture segment and fixed with interlocking screws proximally and distally (Figure 4).

The postoperative course was uncomplicated. At most recent follow-up, radiographs showed near anatomical alignment, and the patient was back to normal activities without use of any pain medication or assistive device.

Discussion

Although other irreducible tibia fracture patterns have been described, midshaft tibia fracture irreducibility caused by entrapment of the fibula within the intramedullary space was a previously unreported difficulty of this very common fracture. More commonly, irreducible tibia fractures are caused by entrapment of soft-tissue structures or fracture fragments.3,4

There are no previous documented cases of fracture patterns in which one long bone telescopes into another. Although not previously reported as occurring traumatically, the fibula was previously used as a vascularized graft in the intramedullary canal of the tibia and elsewhere.

The most well described irreducible fracture-dislocation of the lower leg is the Bosworth type, in which the proximal fragment of the fibula becomes displaced behind the tibia at the ankle joint. In addition, because of the torsional nature of most ankle fractures and the multitude of accompanying soft-tissue structures crossing at the joint, entrapment leading to irreducibility has had several different causes. These soft-tissue entrapment injures are often difficult to distinguish on plain radiographs and require further definition by computed tomography.

The high-energy mechanism of injury we have described is thought to result from lateral translation of the upper portion of the leg with the foot and lower leg fixed in place. We can posit that momentary hypervarus angulation of the tibia and the fibula with subsequent spontaneous partial reduction caused by tissue elasticity could lead to this unique injury pattern.

Although this is the first reported case of entrapment of the fibula within the intramedullary canal of the tibia, the injury should be considered when difficult closed reductions are encountered. It was only after attempted reduction for intramedullary nailing in the operating room that the telescoping fibula and the irreducibility were identified, and open reduction performed. There were no soft-tissue or neurovascular complications, but, had there been, they could have become of urgent concern and altered treatment.

In this case report, we have described a unique fracture pattern that could cause significant morbidity if not appropriately identified and treated in a timely manner.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):E160-E162. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Preoperative orthogonal radiographs need to be carefully scrutinized in irreducible fractures.

- Open reduction is often necessary when soft-tissue or bone is interposed in a fracture site.

- The fibula’s size and interosseous connection to the tibia can lead to entrapment.

- High-energy mechanisms can lead to significant deformity at time of injury, with spontaneous partial reduction prior to initial assessment.

- Consider intramedullary entrapment of adjacent long bones.

The tibia is the most commonly fractured long bone; each year, almost 500,000 tibia fractures occur in the United States alone.1 Low-energy mechanisms of injury usually result from torsional forces and produce less comminuted fractures. Very high-energy injuries apply direct forces to the shin and are often highly comminuted or open, owing to the limited soft-tissue envelope. The extent of soft-tissue injury occurring with these fractures is the best predictor of the development of a complication, particularly nonunion or infection.1 Low-energy closed fractures with limited comminution and sufficient cortical apposition may be treated with closed reduction and casting, but the most common treatment for tibial shaft fractures is intramedullary nailing.2

In the acute setting, closed reduction allows for temporization of soft tissues and prevention of further damage to neurovascular structures. Whether eventual treatment consists of casting or intramedullary fixation, closed reduction must first be achieved.

In this article, we report a unique case of tibial shaft fracture irreducibility caused by telescoping of the distal fibula within the proximal tibial diaphysis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 23-year-old unrestrained driver of a tow truck rear-ended another vehicle at high speed (~45 mph) and became trapped in the vehicle. Extrication time was prolonged. The driver was brought to the emergency department at a level I trauma center, where he was found to have an obvious closed deformity of the right lower leg but remained neurovascularly intact. Radiographs showed a highly comminuted fracture of the right tibial and fibular midshaft with more than 100% medial displacement of the distal fragment (Figure 1).

The next morning, the patient was taken to the operating room for planned closed intramedullary nailing through a suprapatellar approach. After entry to the tibial medullary canal was obtained, a ball-tipped guide wire was advanced proximal to the fracture site, until significant resistance was met. With the aid of intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging, it was determined that the distal fibula fracture segment was entrapped in the medullary canal of the proximal tibia (Figure 2).

After the fibula was liberated, additional closed manipulative reduction techniques were used on the tibia to restore length, alignment, and rotation, and an appropriately sized nail was advanced distally past the fracture segment and fixed with interlocking screws proximally and distally (Figure 4).

The postoperative course was uncomplicated. At most recent follow-up, radiographs showed near anatomical alignment, and the patient was back to normal activities without use of any pain medication or assistive device.

Discussion

Although other irreducible tibia fracture patterns have been described, midshaft tibia fracture irreducibility caused by entrapment of the fibula within the intramedullary space was a previously unreported difficulty of this very common fracture. More commonly, irreducible tibia fractures are caused by entrapment of soft-tissue structures or fracture fragments.3,4

There are no previous documented cases of fracture patterns in which one long bone telescopes into another. Although not previously reported as occurring traumatically, the fibula was previously used as a vascularized graft in the intramedullary canal of the tibia and elsewhere.

The most well described irreducible fracture-dislocation of the lower leg is the Bosworth type, in which the proximal fragment of the fibula becomes displaced behind the tibia at the ankle joint. In addition, because of the torsional nature of most ankle fractures and the multitude of accompanying soft-tissue structures crossing at the joint, entrapment leading to irreducibility has had several different causes. These soft-tissue entrapment injures are often difficult to distinguish on plain radiographs and require further definition by computed tomography.

The high-energy mechanism of injury we have described is thought to result from lateral translation of the upper portion of the leg with the foot and lower leg fixed in place. We can posit that momentary hypervarus angulation of the tibia and the fibula with subsequent spontaneous partial reduction caused by tissue elasticity could lead to this unique injury pattern.

Although this is the first reported case of entrapment of the fibula within the intramedullary canal of the tibia, the injury should be considered when difficult closed reductions are encountered. It was only after attempted reduction for intramedullary nailing in the operating room that the telescoping fibula and the irreducibility were identified, and open reduction performed. There were no soft-tissue or neurovascular complications, but, had there been, they could have become of urgent concern and altered treatment.

In this case report, we have described a unique fracture pattern that could cause significant morbidity if not appropriately identified and treated in a timely manner.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):E160-E162. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Karladani AH, Granhed H, Kärrholm J, Styf J. The influence of fracture etiology and type on fracture healing: a review of 104 consecutive tibial shaft fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121(6):325-328.

2. McGanity P. Tibial shaft fractures. In: Heckman JD, Schenck RC Jr, Agarwal A, eds. Current Orthopedic Diagnosis & Treatment. New York, NY: Springer; 2000:184-185.

3. Ermis MN, Yagmurlu MF, Kilinc AS, Karakas ES. Irreducible fracture dislocation of the ankle caused by tibialis posterior tendon interposition. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49(2):166-171.

4. Green RN, Pullagura MK, Holland JP. Irreducible fracture-dislocation of the knee. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48(3):363-366.

1. Karladani AH, Granhed H, Kärrholm J, Styf J. The influence of fracture etiology and type on fracture healing: a review of 104 consecutive tibial shaft fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121(6):325-328.

2. McGanity P. Tibial shaft fractures. In: Heckman JD, Schenck RC Jr, Agarwal A, eds. Current Orthopedic Diagnosis & Treatment. New York, NY: Springer; 2000:184-185.

3. Ermis MN, Yagmurlu MF, Kilinc AS, Karakas ES. Irreducible fracture dislocation of the ankle caused by tibialis posterior tendon interposition. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49(2):166-171.

4. Green RN, Pullagura MK, Holland JP. Irreducible fracture-dislocation of the knee. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48(3):363-366.

Threat of SUDEP is Remote in Children, Less So in Adults

The risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in children with epilepsy is very small, affecting about 1 in 4500 individuals. The risk of SUDEP in adults is a relatively more common, but still rare, occurrence, affecting 1 in 1000 adults, according to a recent review of the evidence published in Neurology. The major risk factor for SUDEP is generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS), which prompted experts to recommend that clinicians should actively monitor patients with GTCS and inform patients of the value of remaining free of GTCS to reduce their risk of SUDEP.

Harden C, Tomson T, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline summary: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy incidence rates and risk factors. Neurology. 2017;88:1674-1680.

The risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in children with epilepsy is very small, affecting about 1 in 4500 individuals. The risk of SUDEP in adults is a relatively more common, but still rare, occurrence, affecting 1 in 1000 adults, according to a recent review of the evidence published in Neurology. The major risk factor for SUDEP is generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS), which prompted experts to recommend that clinicians should actively monitor patients with GTCS and inform patients of the value of remaining free of GTCS to reduce their risk of SUDEP.

Harden C, Tomson T, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline summary: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy incidence rates and risk factors. Neurology. 2017;88:1674-1680.

The risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in children with epilepsy is very small, affecting about 1 in 4500 individuals. The risk of SUDEP in adults is a relatively more common, but still rare, occurrence, affecting 1 in 1000 adults, according to a recent review of the evidence published in Neurology. The major risk factor for SUDEP is generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS), which prompted experts to recommend that clinicians should actively monitor patients with GTCS and inform patients of the value of remaining free of GTCS to reduce their risk of SUDEP.

Harden C, Tomson T, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline summary: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy incidence rates and risk factors. Neurology. 2017;88:1674-1680.

MRI Reveals Connectivity Pattern in Postsurgical Patients

In order to determine if there are any biomarkers that might help explain why some patients with unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy do well after surgery and some do not, researchers used MRIs to investigate patients and healthy controls. Their analysis revealed a seizure propagation network that suggests a consistent connectivity pattern among patients who remain seizure free for a prolonged period. The seizure free connectivity model was able to differentiate between patients with poor outcomes and those who fared well (P= .0005).

Morgan VL, Englot DJ, Rogers BP, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging connectivity for the prediction of seizure outcome in temporal lobe epilepsy [published online April 27, 2017]. Epilepsia. doi:10.1111/epi.13762.

In order to determine if there are any biomarkers that might help explain why some patients with unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy do well after surgery and some do not, researchers used MRIs to investigate patients and healthy controls. Their analysis revealed a seizure propagation network that suggests a consistent connectivity pattern among patients who remain seizure free for a prolonged period. The seizure free connectivity model was able to differentiate between patients with poor outcomes and those who fared well (P= .0005).

Morgan VL, Englot DJ, Rogers BP, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging connectivity for the prediction of seizure outcome in temporal lobe epilepsy [published online April 27, 2017]. Epilepsia. doi:10.1111/epi.13762.

In order to determine if there are any biomarkers that might help explain why some patients with unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy do well after surgery and some do not, researchers used MRIs to investigate patients and healthy controls. Their analysis revealed a seizure propagation network that suggests a consistent connectivity pattern among patients who remain seizure free for a prolonged period. The seizure free connectivity model was able to differentiate between patients with poor outcomes and those who fared well (P= .0005).

Morgan VL, Englot DJ, Rogers BP, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging connectivity for the prediction of seizure outcome in temporal lobe epilepsy [published online April 27, 2017]. Epilepsia. doi:10.1111/epi.13762.

Is Amygdala Enlargement a Unique Feature of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy?

Although an enlarged amygdala (AE) has been found in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, a recent analysis found that AE exists among those without epilepsy. The study used high resolution T1-weighted MRI scans and analyzed healthy controls and patients with epilepsy. The investigation revealed that AE was more common in nonlesional localization related epilepsy, when compared with idiopathic generalized epilepsy and healthy controls.

Reyes A, Thesen R, Kuzniecky R, et al. Amygdala enlargement: temporal lobe epilepsy subtype or nonspecific finding? Epilepsy Res. 2017;132:34-40.

Although an enlarged amygdala (AE) has been found in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, a recent analysis found that AE exists among those without epilepsy. The study used high resolution T1-weighted MRI scans and analyzed healthy controls and patients with epilepsy. The investigation revealed that AE was more common in nonlesional localization related epilepsy, when compared with idiopathic generalized epilepsy and healthy controls.

Reyes A, Thesen R, Kuzniecky R, et al. Amygdala enlargement: temporal lobe epilepsy subtype or nonspecific finding? Epilepsy Res. 2017;132:34-40.

Although an enlarged amygdala (AE) has been found in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, a recent analysis found that AE exists among those without epilepsy. The study used high resolution T1-weighted MRI scans and analyzed healthy controls and patients with epilepsy. The investigation revealed that AE was more common in nonlesional localization related epilepsy, when compared with idiopathic generalized epilepsy and healthy controls.

Reyes A, Thesen R, Kuzniecky R, et al. Amygdala enlargement: temporal lobe epilepsy subtype or nonspecific finding? Epilepsy Res. 2017;132:34-40.

Marijuana-related visits to Colorado ED steadily increasing

SAN FRANCISCO – Visits to the emergency department and urgent care by adolescents using marijuana in Colorado increased from 2005 to 2015, a retrospective study showed.

The state legalized medical marijuana use in 2000 and recreational marijuana use in 2014.

“Adolescents with psychiatric illness comprised a large proportion of marijuana exposures,” said lead author George Sam Wang, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver in Aurora. “Coingestants were common and included ethanol, amphetamines, and opiates,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

However, only eight states have legalized recreational use, and federal data may not reflect the reality within states with legalization. In Colorado, 8% of youth in that age range have used marijuana in the past month.

Dr. Wang and his colleagues therefore conducted a retrospective review of adolescent and young adult visits to the Children’s Hospital Colorado ED or any of the system’s urgent care clinics between January 2005 and December 2015. They included all individuals 13-21 years old who had a positive urine drug screen for marijuana or whose visit was coded for marijuana use (ICD-9 codes of 305.20, 969.6, or E854.1).

During those 11 years, 3,844 visits occurred, and the rate of visits related to cannabis increased from 2/1,000 emergency department/urgent care visits in 2009 to 4/1,000 in 2015. A little over half (55%) of the patients were male, and the average age was 16 years.

A nearly linear steady increase in the number of visits occurred over the study period, from 146 visits in 2005 to 639 visits in 2015. Similarly, the number of annual psychiatry evaluations increased fivefold, from 75 in 2005 to 394 in 2015. Two-thirds of the patients overall (66%) underwent a psychiatric evaluation.

The most common ICD codes reported were for unspecified cannabis use (50% of visits), unspecified episodic mood disorder (20%), and alcohol abuse (15%). Urine drug screens for alcohol were positive in 70% of the patients, while amphetamines, benzodiazepines, opiates, and cocaine were each present in 4% of the patients. Less than 1% had positive drug screens for phencyclidine, barbiturates, oxycodone, and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine.

Close behind unspecified alcohol abuse were codes for suicidal ideation and depressive disorder, both noted in 14% of visits. Additional codes, present in 9%-12% of visits, included educational circumstance, ADHD, unspecified anxiety, unspecified asthma, and tobacco use disorder.

Just over half of all patients (53%) were discharged home. Approximately one-quarter (27%) were admitted, and 10% were transferred to another facility. Information was not provided for the remaining 10%.

“Targeted education and prevention strategies for marijuana use are necessary in the adolescent population to reduce the public health impact,” Dr. Wang said, adding that the ED should initiate behavioral health screenings and/or interventions, such as referral to treatment, with adolescents using marijuana.