User login

Patterns of care with regard to whole-brain radiotherapy technique and delivery among academic centers in the United States

Despite the recent advances in systemic therapy, metastatic spread to the brain continues to be the most common neurologic complication of many cancers. The clinical incidence of brain metastases varies with primary cancer diagnosis, with estimates ranging from 1.2%-19.8%.1,2 Metastatic spread to the brain is even more prevalent at autopsy, with evidence of intracranial tumor being found in 26% of patients in some series.3 It is possible that the clinical incidence of metastatic disease to the brain will continue to increase as newer therapeutic agents improve survival and imaging techniques continue to improve.

The management of brain metastases has changed rapidly as technological improvements have made treatment increasingly safe and efficacious. Traditionally, treatment consisted of radiotherapy to the whole brain, with or without surgical resection.4,5 More recently, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) has been adopted on the basis of evidence that it is safe and efficacious alone or in combination with radiotherapy to the whole brain.6 Further evidence is emerging that neurocognitive outcomes are improved when whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) is omitted, which possibly contributes to improved patient quality of life.7 Taking into account this and other data, the American Society for Radiation Oncology’s Choosing Wisely campaign now recommends not routinely adding WBRT to radiosurgery in patients with limited brain metastases.8

Despite this recommendation, many patients continue to benefit from WBRT, and it remains a common treatment in radiation oncology clinics across the US for several reasons. Many patients present with multiple brain metastases and are ineligible for radiosurgery. Even for technically eligible patients, WBRT has been shown to improve local control and decrease the rate of distant brain failure over radiosurgery alone.6 With higher rates of subsequent failures, patients receiving radiosurgery alone must adhere to more rigorous follow-up and imaging schedules, which can be difficult for many rural patients who have to travel long distances to centers. Furthermore, there is some suggestion that this decreased failure rate may result in improved survival in highly selected patients with excellent disease and performance status.9 Controversies exist, however, and strong institutional biases persist, contributing to significant differences in practice. We surveyed academic radiation oncologists and in an effort to identify and describe practice patterns in the delivery of WBRT at academic centers.

Methods

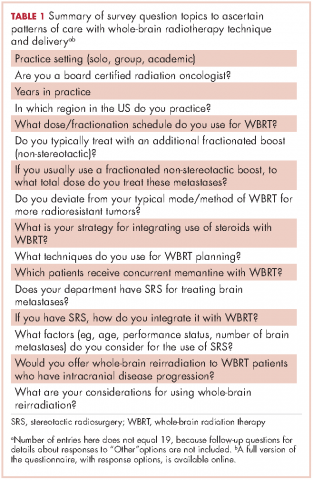

We conducted a thorough review of available literature on radiation for brain metastases and based on our findings, devised a survey 19 questions to ascertain practice patterns and treatment delivery among US academic physicians (Table 1). After obtaining institutional review board approval to do the study, we sent the survey to program coordinators at radiation oncology programs that are accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. We instructed coordinators to e-mail the survey to their practicing resident and attending physicians. The surveys were created using SurveyMonkey software. We obtained informed consent from the providers. A total of 3 follow-up e-mails were sent to each recipient of the survey to solicit responses, similar to the Dillman Total Design Survey Method.10

SPSS version 22.0 was used to analyze the data in an exploratory fashion. Statistical methods were used to assess the association of demographic data with SRS and WBRT delivery and treatment technique items when the analyses involved percentages that included the Pearson chi-square statistic and the chi-square test for linear trend. When the analysis focused on ranking data, the Kruskal-Wallis test, Mann-Whitney U test, the Jonckheere-Terpstra and the Kendall tau-b rank correlation were used as appropriate. If there were small sample sizes within some groups, then exact significant levels were assessed. Statistical significance was set by convention at P < .05.

Results

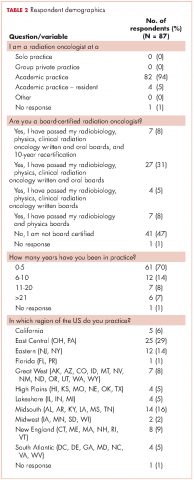

We received 95 responses of which 87 were considered complete for analysis. Forty-seven percent of the 87 respondents were not board-certified, and the remainder had passed their radiobiology and physics boards exams. A majority of respondents (70%, 61 of 87) were physicians who had been in practice for ≤5 years. Fifty-four percent of respondents were located in the Northeast US, 22% in the South, 14% in the West, and 10% in the Midwest and Hawaii (Table 2).

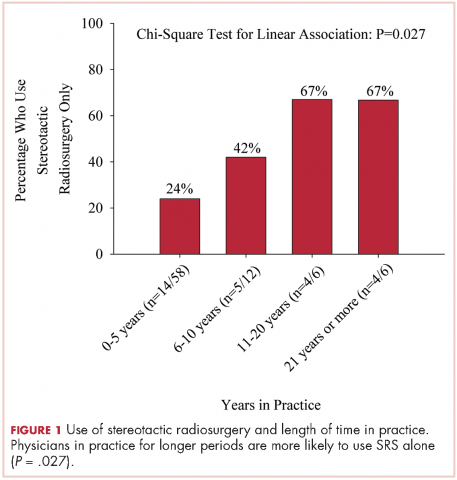

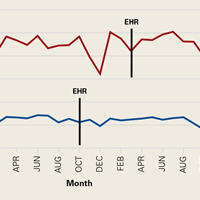

We used the chi-square test for linear trends to assess for a relationship between years of practice and whether respondents deviated from their typical method of WBRT therapy when treating more radioresistant tumors (melanoma, renal cell carcinoma). Respondents were classified by years in practice: 0-5, 6-10, 11-20, and >21 years. The results showed a linear association, with those in practice for longer periods more likely to use SRS alone, P = .027 (Figure 1).

Discussion

The incidence of brain metastases is increasing because of improvements in diagnostic imaging techniques and advancements in systemic therapy control of extracranial disease but not of intracranial disease or metastasis, because therapies do not cross the blood-brain barrier.11,12 Brain metastases are the most common type of brain tumor. Given that most chemotherapeutic agents cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, radiotherapy is considered a means of treatment and of controlling brain metastases. Early data from the 1950s13 and 1960s14 have suggested clinical improvement with brain radiation, making radiotherapy the cornerstone for treatment of brain metastases.

The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) has evaluated several fractionation schedules, with 5 schemas evaluated by the RTOG 6901 and 7361 studies: 30 Gy in 10 fractions, 30 Gy in 15 fractions, 40 Gy in 15 fractions, 40 Gy in 20 fractions, and 20 Gy in 5 fractions. The combined results from these two trials showed that outcomes were similar for patients treated with a shorter regimen than for those treated with a more protracted schedule. In our study, respondents reported that they most frequently treated brain metastases to a total dose of 30 Gy in 10 fractions. Given the results of the aforementioned RTOG trials and practice patterns among academic physicians, we recommend all practitioners consider a shorter hypofractioned course when treating brain metastases with WBRT. This will also reduce delays for patients who are likely to benefit greatly from earlier enrollment into hospice care, because protracted radiation schedules typically are not covered while a patient is in hospice.

Pharmacologic management for patients with brain metastases is important for symptomatic improvement. Glucocorticoids are important for palliation of symptoms from edema and increased intracranial pressure.15 However, steroids have a multitude of side effects and their use in asymptomatic patients is unnecessary. Improvements in imaging and detection11 have allowed us to find smaller and asymptomatic brain tumors. In our survey, it was promising to see a change in former practice patterns, with only 8% of academic practitioners regularly prescribing steroids to all of their patients receiving whole-brain radiation.

Diminished cognitive function and short-term memory loss are troublesome side effects of WBRT. As cancer patients live longer, such cognitive dysfunction will become more than just a nuisance. The RTOG has investigated the use of prophylactic memantine for patients receiving whole-brain radiation to determine if it would aid in the preservation of cognition. It found that patients who received memantine did better and had delayed time to cognitive decline and a reduced rate of memory decline, executive function, and processing speed.16 In our study, about a third of practitioners prescribed memantine and it was reserved for patients who had an otherwise favorable prognosis.

The RTOG has also investigated adjusting treatment technique for patients who receive WBRT. RTOG 0933 was a phase 2 trial that evaluated hippocampal avoidance during deliverance of WBRT with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). Results showed that avoiding the hippocampus during WBRT was associated with improved memory preservation and patient quality of life.17 In a survey of practicing radiation oncologists in the US, most reported that they did not use memantine or IMRT for hippocampal sparing when delivering whole-brain radiation.18 Given the positive results of RTOG 0933 and 0614, the NRG Oncology research organization is conducting a phase 3 randomized trial that compares memantine use for patients receiving whole-brain radiation with or without hippocampal sparing to determine if patients will have reduced cognitive decline. All patients receiving WBRT should be considered for enrolment on this trial if they are eligible.

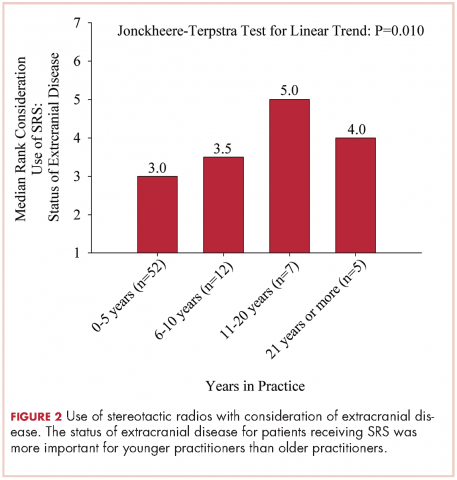

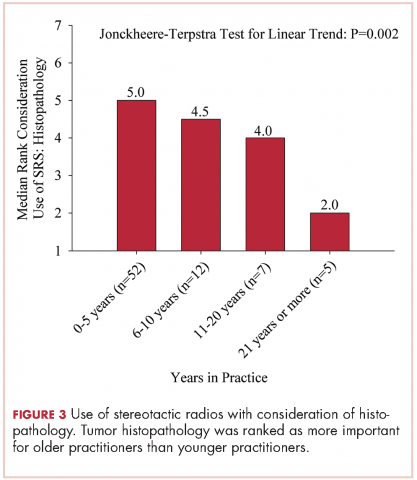

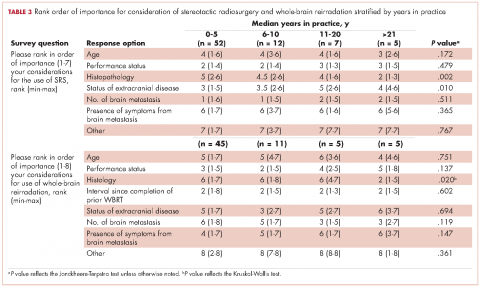

The delivery of brain radiation has continued to change, especially with the introduction of SRS. Recent publication of a meta-analysis of three phase 3 trials evaluating SRS with or without WBRT for 1-4 brain metastases showed that patients aged 50 years or younger experienced a survival benefit with SRS, and the omission of whole-brain radiation did not affect distant brain relapse rates. 19 The authors recommended that for this population, SRS alone is the preferred treatment. In our study, physicians who had been in practice for a longer time were more likely to treat using SRS alone. The results showed a linear association, with those in practice for a longer time being more likely to use SRS alone compared with those practicing for a shorter time (P = .027). Accordingly, 67% of respondents (8 of 12) who had been in practice for 11 or more years used SRS alone, whereas 24% (14 of 58) who had practiced for 0-5 years and 42% (5 of 12) who had practice from 6-10 years used SRS alone (Figure 1). When treating with SRS, younger practitioners placed more importance on the status of extracranial disease, whereas older practitioners placed more importance on tumor histopathology.

The use of repeat whole-brain reirradiation is more controversial among practitioners.20-22 Son and colleagues evaluated patients who needed whole-brain reirradiation after intracranial disease progression.22 The authors noted that patients with stable extracranial disease benefited from reirradiation. In our study, we found that when considering whole-brain reirradiation, older practitioners placed more importance on tumor histology than other factors.

As far as we know, this is the first study evaluating the practices and patterns of care with regard to the delivery of brain radiation in academic centers in the US. We found that time in practice was the most significant predictor of treatment technique and delivery. We also found that older practitioners place more importance on tumor histopathology compared with younger practitioners. A limitation of this study is that we had contact information only for program coordinators at ACGME-accredited programs. As such, we were not able to assess practice patterns among community practitioners. In addition, it seemed that residents and junior faculty were more likely to respond to this survey, likely because of the dissemination pattern. Given the evolution and diversity of treatment regimens for brain metastases, we believe that patients with brain metastases should be managed individually using a multidisciplinary approach.

1. Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Sloan AE, Davis FG, Vigneau FD, Lai P, Sawaya RE. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2865-2872.

2. Schouten LJ, Rutten J, Huveneers HA, Twijnstra A. Incidence of brain metastases in a cohort of patients with carcinoma of the breast, colon, kidney, and lung and melanoma. Cancer. 2002;94(10):2698-2705.

3. Takakura K. Metastatic tumors of the central nervous system. Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin; 1982.

4. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1485-1489.

5. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Walsh JW, et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. New Engl J Med. 1990;322(8):494-500.

6. Sahgal A, Aoyama H, Kocher M, et al. Phase 3 trials of stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiation therapy for 1 to 4 brain metastases: individual patient data meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(4):710-717.

7. Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR, et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1037-1044.

8. Choosing Wisely [ASTRO]. Don’t routinely add adjuvant whole-brain radiation therapy to stereotactic radiosurgery for limited brain metastases. http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-society-radiation-oncology-adjunct-whole-brain-radiation-therapy/. Updated June 21, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

9. Aoyama H, Tago M, Shirato H, Japanese Radiation Oncology Study Group I. Stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases: secondary analysis of the JROSG 99-1 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):457-464.

10. Hoddinott SN, Bass MJ. The Dillman total design survey method. Can Fam Physician. 1986;32:2366-2368.

11. Nayak L, Lee EQ, Wen PY. Epidemiology of brain metastases. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14(1):48-54.

12. Gavrilovic IT, Posner JB. Brain metastases: epidemiology and pathophysiology. J Neurooncol. 2005;75(1):5-14.

13. Chao JH, Phillips R, Nickson JJ. Roentgen-ray therapy of cerebral metastases. Cancer. 1954;7(4):682-689.

14. Nieder C, Niewald M, Schnabel K. Treatment of brain metastases from hypernephroma. Urol Int. 1996;57(1):17-20.

15. Ryken TC, McDermott M, Robinson PD, et al. The role of steroids in the management of brain metastases: a systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Neurooncol. 2010;96(1):103-114.

16. Brown PD, Pugh S, Laack NN, et al. Memantine for the prevention of cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(10):1429-1437.

17. Gondi V, Pugh SL, Tome WA, et al. Preservation of memory with conformal avoidance of the hippocampal neural stem-cell compartment during whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases (RTOG 0933): a phase II multi-institutional trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3810-3816.

18. Slade AN, Stanic S. The impact of RTOG 0614 and RTOG 0933 trials in routine clinical practice: The US Survey of Utilization of Memantine and IMRT planning for hippocampus sparing in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;47:74-77.

19. Sahgal A, Aoyama H, Kocher M, et al. Phase 3 trials of stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiation therapy for 1 to 4 brain metastases: individual patient data meta-analysis. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2015;91(4):710-717.

20. Hazuka MB, Kinzie JJ. Brain metastases: results and effects of re-irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15(2):433-437.

21. Sadikov E, Bezjak A, Yi QL, et al. Value of whole-brain re-irradiation for brain metastases — single centre experience. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2007;19(7):532-538.

22. Son CH, Jimenez R, Niemierko A, Loeffler JS, Oh KS, Shih HA. outcomes after whole-brain reirradiation in patients with brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(2):e167-e172.

Despite the recent advances in systemic therapy, metastatic spread to the brain continues to be the most common neurologic complication of many cancers. The clinical incidence of brain metastases varies with primary cancer diagnosis, with estimates ranging from 1.2%-19.8%.1,2 Metastatic spread to the brain is even more prevalent at autopsy, with evidence of intracranial tumor being found in 26% of patients in some series.3 It is possible that the clinical incidence of metastatic disease to the brain will continue to increase as newer therapeutic agents improve survival and imaging techniques continue to improve.

The management of brain metastases has changed rapidly as technological improvements have made treatment increasingly safe and efficacious. Traditionally, treatment consisted of radiotherapy to the whole brain, with or without surgical resection.4,5 More recently, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) has been adopted on the basis of evidence that it is safe and efficacious alone or in combination with radiotherapy to the whole brain.6 Further evidence is emerging that neurocognitive outcomes are improved when whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) is omitted, which possibly contributes to improved patient quality of life.7 Taking into account this and other data, the American Society for Radiation Oncology’s Choosing Wisely campaign now recommends not routinely adding WBRT to radiosurgery in patients with limited brain metastases.8

Despite this recommendation, many patients continue to benefit from WBRT, and it remains a common treatment in radiation oncology clinics across the US for several reasons. Many patients present with multiple brain metastases and are ineligible for radiosurgery. Even for technically eligible patients, WBRT has been shown to improve local control and decrease the rate of distant brain failure over radiosurgery alone.6 With higher rates of subsequent failures, patients receiving radiosurgery alone must adhere to more rigorous follow-up and imaging schedules, which can be difficult for many rural patients who have to travel long distances to centers. Furthermore, there is some suggestion that this decreased failure rate may result in improved survival in highly selected patients with excellent disease and performance status.9 Controversies exist, however, and strong institutional biases persist, contributing to significant differences in practice. We surveyed academic radiation oncologists and in an effort to identify and describe practice patterns in the delivery of WBRT at academic centers.

Methods

We conducted a thorough review of available literature on radiation for brain metastases and based on our findings, devised a survey 19 questions to ascertain practice patterns and treatment delivery among US academic physicians (Table 1). After obtaining institutional review board approval to do the study, we sent the survey to program coordinators at radiation oncology programs that are accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. We instructed coordinators to e-mail the survey to their practicing resident and attending physicians. The surveys were created using SurveyMonkey software. We obtained informed consent from the providers. A total of 3 follow-up e-mails were sent to each recipient of the survey to solicit responses, similar to the Dillman Total Design Survey Method.10

SPSS version 22.0 was used to analyze the data in an exploratory fashion. Statistical methods were used to assess the association of demographic data with SRS and WBRT delivery and treatment technique items when the analyses involved percentages that included the Pearson chi-square statistic and the chi-square test for linear trend. When the analysis focused on ranking data, the Kruskal-Wallis test, Mann-Whitney U test, the Jonckheere-Terpstra and the Kendall tau-b rank correlation were used as appropriate. If there were small sample sizes within some groups, then exact significant levels were assessed. Statistical significance was set by convention at P < .05.

Results

We received 95 responses of which 87 were considered complete for analysis. Forty-seven percent of the 87 respondents were not board-certified, and the remainder had passed their radiobiology and physics boards exams. A majority of respondents (70%, 61 of 87) were physicians who had been in practice for ≤5 years. Fifty-four percent of respondents were located in the Northeast US, 22% in the South, 14% in the West, and 10% in the Midwest and Hawaii (Table 2).

We used the chi-square test for linear trends to assess for a relationship between years of practice and whether respondents deviated from their typical method of WBRT therapy when treating more radioresistant tumors (melanoma, renal cell carcinoma). Respondents were classified by years in practice: 0-5, 6-10, 11-20, and >21 years. The results showed a linear association, with those in practice for longer periods more likely to use SRS alone, P = .027 (Figure 1).

Discussion

The incidence of brain metastases is increasing because of improvements in diagnostic imaging techniques and advancements in systemic therapy control of extracranial disease but not of intracranial disease or metastasis, because therapies do not cross the blood-brain barrier.11,12 Brain metastases are the most common type of brain tumor. Given that most chemotherapeutic agents cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, radiotherapy is considered a means of treatment and of controlling brain metastases. Early data from the 1950s13 and 1960s14 have suggested clinical improvement with brain radiation, making radiotherapy the cornerstone for treatment of brain metastases.

The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) has evaluated several fractionation schedules, with 5 schemas evaluated by the RTOG 6901 and 7361 studies: 30 Gy in 10 fractions, 30 Gy in 15 fractions, 40 Gy in 15 fractions, 40 Gy in 20 fractions, and 20 Gy in 5 fractions. The combined results from these two trials showed that outcomes were similar for patients treated with a shorter regimen than for those treated with a more protracted schedule. In our study, respondents reported that they most frequently treated brain metastases to a total dose of 30 Gy in 10 fractions. Given the results of the aforementioned RTOG trials and practice patterns among academic physicians, we recommend all practitioners consider a shorter hypofractioned course when treating brain metastases with WBRT. This will also reduce delays for patients who are likely to benefit greatly from earlier enrollment into hospice care, because protracted radiation schedules typically are not covered while a patient is in hospice.

Pharmacologic management for patients with brain metastases is important for symptomatic improvement. Glucocorticoids are important for palliation of symptoms from edema and increased intracranial pressure.15 However, steroids have a multitude of side effects and their use in asymptomatic patients is unnecessary. Improvements in imaging and detection11 have allowed us to find smaller and asymptomatic brain tumors. In our survey, it was promising to see a change in former practice patterns, with only 8% of academic practitioners regularly prescribing steroids to all of their patients receiving whole-brain radiation.

Diminished cognitive function and short-term memory loss are troublesome side effects of WBRT. As cancer patients live longer, such cognitive dysfunction will become more than just a nuisance. The RTOG has investigated the use of prophylactic memantine for patients receiving whole-brain radiation to determine if it would aid in the preservation of cognition. It found that patients who received memantine did better and had delayed time to cognitive decline and a reduced rate of memory decline, executive function, and processing speed.16 In our study, about a third of practitioners prescribed memantine and it was reserved for patients who had an otherwise favorable prognosis.

The RTOG has also investigated adjusting treatment technique for patients who receive WBRT. RTOG 0933 was a phase 2 trial that evaluated hippocampal avoidance during deliverance of WBRT with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). Results showed that avoiding the hippocampus during WBRT was associated with improved memory preservation and patient quality of life.17 In a survey of practicing radiation oncologists in the US, most reported that they did not use memantine or IMRT for hippocampal sparing when delivering whole-brain radiation.18 Given the positive results of RTOG 0933 and 0614, the NRG Oncology research organization is conducting a phase 3 randomized trial that compares memantine use for patients receiving whole-brain radiation with or without hippocampal sparing to determine if patients will have reduced cognitive decline. All patients receiving WBRT should be considered for enrolment on this trial if they are eligible.

The delivery of brain radiation has continued to change, especially with the introduction of SRS. Recent publication of a meta-analysis of three phase 3 trials evaluating SRS with or without WBRT for 1-4 brain metastases showed that patients aged 50 years or younger experienced a survival benefit with SRS, and the omission of whole-brain radiation did not affect distant brain relapse rates. 19 The authors recommended that for this population, SRS alone is the preferred treatment. In our study, physicians who had been in practice for a longer time were more likely to treat using SRS alone. The results showed a linear association, with those in practice for a longer time being more likely to use SRS alone compared with those practicing for a shorter time (P = .027). Accordingly, 67% of respondents (8 of 12) who had been in practice for 11 or more years used SRS alone, whereas 24% (14 of 58) who had practiced for 0-5 years and 42% (5 of 12) who had practice from 6-10 years used SRS alone (Figure 1). When treating with SRS, younger practitioners placed more importance on the status of extracranial disease, whereas older practitioners placed more importance on tumor histopathology.

The use of repeat whole-brain reirradiation is more controversial among practitioners.20-22 Son and colleagues evaluated patients who needed whole-brain reirradiation after intracranial disease progression.22 The authors noted that patients with stable extracranial disease benefited from reirradiation. In our study, we found that when considering whole-brain reirradiation, older practitioners placed more importance on tumor histology than other factors.

As far as we know, this is the first study evaluating the practices and patterns of care with regard to the delivery of brain radiation in academic centers in the US. We found that time in practice was the most significant predictor of treatment technique and delivery. We also found that older practitioners place more importance on tumor histopathology compared with younger practitioners. A limitation of this study is that we had contact information only for program coordinators at ACGME-accredited programs. As such, we were not able to assess practice patterns among community practitioners. In addition, it seemed that residents and junior faculty were more likely to respond to this survey, likely because of the dissemination pattern. Given the evolution and diversity of treatment regimens for brain metastases, we believe that patients with brain metastases should be managed individually using a multidisciplinary approach.

Despite the recent advances in systemic therapy, metastatic spread to the brain continues to be the most common neurologic complication of many cancers. The clinical incidence of brain metastases varies with primary cancer diagnosis, with estimates ranging from 1.2%-19.8%.1,2 Metastatic spread to the brain is even more prevalent at autopsy, with evidence of intracranial tumor being found in 26% of patients in some series.3 It is possible that the clinical incidence of metastatic disease to the brain will continue to increase as newer therapeutic agents improve survival and imaging techniques continue to improve.

The management of brain metastases has changed rapidly as technological improvements have made treatment increasingly safe and efficacious. Traditionally, treatment consisted of radiotherapy to the whole brain, with or without surgical resection.4,5 More recently, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) has been adopted on the basis of evidence that it is safe and efficacious alone or in combination with radiotherapy to the whole brain.6 Further evidence is emerging that neurocognitive outcomes are improved when whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) is omitted, which possibly contributes to improved patient quality of life.7 Taking into account this and other data, the American Society for Radiation Oncology’s Choosing Wisely campaign now recommends not routinely adding WBRT to radiosurgery in patients with limited brain metastases.8

Despite this recommendation, many patients continue to benefit from WBRT, and it remains a common treatment in radiation oncology clinics across the US for several reasons. Many patients present with multiple brain metastases and are ineligible for radiosurgery. Even for technically eligible patients, WBRT has been shown to improve local control and decrease the rate of distant brain failure over radiosurgery alone.6 With higher rates of subsequent failures, patients receiving radiosurgery alone must adhere to more rigorous follow-up and imaging schedules, which can be difficult for many rural patients who have to travel long distances to centers. Furthermore, there is some suggestion that this decreased failure rate may result in improved survival in highly selected patients with excellent disease and performance status.9 Controversies exist, however, and strong institutional biases persist, contributing to significant differences in practice. We surveyed academic radiation oncologists and in an effort to identify and describe practice patterns in the delivery of WBRT at academic centers.

Methods

We conducted a thorough review of available literature on radiation for brain metastases and based on our findings, devised a survey 19 questions to ascertain practice patterns and treatment delivery among US academic physicians (Table 1). After obtaining institutional review board approval to do the study, we sent the survey to program coordinators at radiation oncology programs that are accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. We instructed coordinators to e-mail the survey to their practicing resident and attending physicians. The surveys were created using SurveyMonkey software. We obtained informed consent from the providers. A total of 3 follow-up e-mails were sent to each recipient of the survey to solicit responses, similar to the Dillman Total Design Survey Method.10

SPSS version 22.0 was used to analyze the data in an exploratory fashion. Statistical methods were used to assess the association of demographic data with SRS and WBRT delivery and treatment technique items when the analyses involved percentages that included the Pearson chi-square statistic and the chi-square test for linear trend. When the analysis focused on ranking data, the Kruskal-Wallis test, Mann-Whitney U test, the Jonckheere-Terpstra and the Kendall tau-b rank correlation were used as appropriate. If there were small sample sizes within some groups, then exact significant levels were assessed. Statistical significance was set by convention at P < .05.

Results

We received 95 responses of which 87 were considered complete for analysis. Forty-seven percent of the 87 respondents were not board-certified, and the remainder had passed their radiobiology and physics boards exams. A majority of respondents (70%, 61 of 87) were physicians who had been in practice for ≤5 years. Fifty-four percent of respondents were located in the Northeast US, 22% in the South, 14% in the West, and 10% in the Midwest and Hawaii (Table 2).

We used the chi-square test for linear trends to assess for a relationship between years of practice and whether respondents deviated from their typical method of WBRT therapy when treating more radioresistant tumors (melanoma, renal cell carcinoma). Respondents were classified by years in practice: 0-5, 6-10, 11-20, and >21 years. The results showed a linear association, with those in practice for longer periods more likely to use SRS alone, P = .027 (Figure 1).

Discussion

The incidence of brain metastases is increasing because of improvements in diagnostic imaging techniques and advancements in systemic therapy control of extracranial disease but not of intracranial disease or metastasis, because therapies do not cross the blood-brain barrier.11,12 Brain metastases are the most common type of brain tumor. Given that most chemotherapeutic agents cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, radiotherapy is considered a means of treatment and of controlling brain metastases. Early data from the 1950s13 and 1960s14 have suggested clinical improvement with brain radiation, making radiotherapy the cornerstone for treatment of brain metastases.

The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) has evaluated several fractionation schedules, with 5 schemas evaluated by the RTOG 6901 and 7361 studies: 30 Gy in 10 fractions, 30 Gy in 15 fractions, 40 Gy in 15 fractions, 40 Gy in 20 fractions, and 20 Gy in 5 fractions. The combined results from these two trials showed that outcomes were similar for patients treated with a shorter regimen than for those treated with a more protracted schedule. In our study, respondents reported that they most frequently treated brain metastases to a total dose of 30 Gy in 10 fractions. Given the results of the aforementioned RTOG trials and practice patterns among academic physicians, we recommend all practitioners consider a shorter hypofractioned course when treating brain metastases with WBRT. This will also reduce delays for patients who are likely to benefit greatly from earlier enrollment into hospice care, because protracted radiation schedules typically are not covered while a patient is in hospice.

Pharmacologic management for patients with brain metastases is important for symptomatic improvement. Glucocorticoids are important for palliation of symptoms from edema and increased intracranial pressure.15 However, steroids have a multitude of side effects and their use in asymptomatic patients is unnecessary. Improvements in imaging and detection11 have allowed us to find smaller and asymptomatic brain tumors. In our survey, it was promising to see a change in former practice patterns, with only 8% of academic practitioners regularly prescribing steroids to all of their patients receiving whole-brain radiation.

Diminished cognitive function and short-term memory loss are troublesome side effects of WBRT. As cancer patients live longer, such cognitive dysfunction will become more than just a nuisance. The RTOG has investigated the use of prophylactic memantine for patients receiving whole-brain radiation to determine if it would aid in the preservation of cognition. It found that patients who received memantine did better and had delayed time to cognitive decline and a reduced rate of memory decline, executive function, and processing speed.16 In our study, about a third of practitioners prescribed memantine and it was reserved for patients who had an otherwise favorable prognosis.

The RTOG has also investigated adjusting treatment technique for patients who receive WBRT. RTOG 0933 was a phase 2 trial that evaluated hippocampal avoidance during deliverance of WBRT with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). Results showed that avoiding the hippocampus during WBRT was associated with improved memory preservation and patient quality of life.17 In a survey of practicing radiation oncologists in the US, most reported that they did not use memantine or IMRT for hippocampal sparing when delivering whole-brain radiation.18 Given the positive results of RTOG 0933 and 0614, the NRG Oncology research organization is conducting a phase 3 randomized trial that compares memantine use for patients receiving whole-brain radiation with or without hippocampal sparing to determine if patients will have reduced cognitive decline. All patients receiving WBRT should be considered for enrolment on this trial if they are eligible.

The delivery of brain radiation has continued to change, especially with the introduction of SRS. Recent publication of a meta-analysis of three phase 3 trials evaluating SRS with or without WBRT for 1-4 brain metastases showed that patients aged 50 years or younger experienced a survival benefit with SRS, and the omission of whole-brain radiation did not affect distant brain relapse rates. 19 The authors recommended that for this population, SRS alone is the preferred treatment. In our study, physicians who had been in practice for a longer time were more likely to treat using SRS alone. The results showed a linear association, with those in practice for a longer time being more likely to use SRS alone compared with those practicing for a shorter time (P = .027). Accordingly, 67% of respondents (8 of 12) who had been in practice for 11 or more years used SRS alone, whereas 24% (14 of 58) who had practiced for 0-5 years and 42% (5 of 12) who had practice from 6-10 years used SRS alone (Figure 1). When treating with SRS, younger practitioners placed more importance on the status of extracranial disease, whereas older practitioners placed more importance on tumor histopathology.

The use of repeat whole-brain reirradiation is more controversial among practitioners.20-22 Son and colleagues evaluated patients who needed whole-brain reirradiation after intracranial disease progression.22 The authors noted that patients with stable extracranial disease benefited from reirradiation. In our study, we found that when considering whole-brain reirradiation, older practitioners placed more importance on tumor histology than other factors.

As far as we know, this is the first study evaluating the practices and patterns of care with regard to the delivery of brain radiation in academic centers in the US. We found that time in practice was the most significant predictor of treatment technique and delivery. We also found that older practitioners place more importance on tumor histopathology compared with younger practitioners. A limitation of this study is that we had contact information only for program coordinators at ACGME-accredited programs. As such, we were not able to assess practice patterns among community practitioners. In addition, it seemed that residents and junior faculty were more likely to respond to this survey, likely because of the dissemination pattern. Given the evolution and diversity of treatment regimens for brain metastases, we believe that patients with brain metastases should be managed individually using a multidisciplinary approach.

1. Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Sloan AE, Davis FG, Vigneau FD, Lai P, Sawaya RE. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2865-2872.

2. Schouten LJ, Rutten J, Huveneers HA, Twijnstra A. Incidence of brain metastases in a cohort of patients with carcinoma of the breast, colon, kidney, and lung and melanoma. Cancer. 2002;94(10):2698-2705.

3. Takakura K. Metastatic tumors of the central nervous system. Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin; 1982.

4. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1485-1489.

5. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Walsh JW, et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. New Engl J Med. 1990;322(8):494-500.

6. Sahgal A, Aoyama H, Kocher M, et al. Phase 3 trials of stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiation therapy for 1 to 4 brain metastases: individual patient data meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(4):710-717.

7. Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR, et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1037-1044.

8. Choosing Wisely [ASTRO]. Don’t routinely add adjuvant whole-brain radiation therapy to stereotactic radiosurgery for limited brain metastases. http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-society-radiation-oncology-adjunct-whole-brain-radiation-therapy/. Updated June 21, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

9. Aoyama H, Tago M, Shirato H, Japanese Radiation Oncology Study Group I. Stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases: secondary analysis of the JROSG 99-1 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):457-464.

10. Hoddinott SN, Bass MJ. The Dillman total design survey method. Can Fam Physician. 1986;32:2366-2368.

11. Nayak L, Lee EQ, Wen PY. Epidemiology of brain metastases. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14(1):48-54.

12. Gavrilovic IT, Posner JB. Brain metastases: epidemiology and pathophysiology. J Neurooncol. 2005;75(1):5-14.

13. Chao JH, Phillips R, Nickson JJ. Roentgen-ray therapy of cerebral metastases. Cancer. 1954;7(4):682-689.

14. Nieder C, Niewald M, Schnabel K. Treatment of brain metastases from hypernephroma. Urol Int. 1996;57(1):17-20.

15. Ryken TC, McDermott M, Robinson PD, et al. The role of steroids in the management of brain metastases: a systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Neurooncol. 2010;96(1):103-114.

16. Brown PD, Pugh S, Laack NN, et al. Memantine for the prevention of cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(10):1429-1437.

17. Gondi V, Pugh SL, Tome WA, et al. Preservation of memory with conformal avoidance of the hippocampal neural stem-cell compartment during whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases (RTOG 0933): a phase II multi-institutional trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3810-3816.

18. Slade AN, Stanic S. The impact of RTOG 0614 and RTOG 0933 trials in routine clinical practice: The US Survey of Utilization of Memantine and IMRT planning for hippocampus sparing in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;47:74-77.

19. Sahgal A, Aoyama H, Kocher M, et al. Phase 3 trials of stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiation therapy for 1 to 4 brain metastases: individual patient data meta-analysis. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2015;91(4):710-717.

20. Hazuka MB, Kinzie JJ. Brain metastases: results and effects of re-irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15(2):433-437.

21. Sadikov E, Bezjak A, Yi QL, et al. Value of whole-brain re-irradiation for brain metastases — single centre experience. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2007;19(7):532-538.

22. Son CH, Jimenez R, Niemierko A, Loeffler JS, Oh KS, Shih HA. outcomes after whole-brain reirradiation in patients with brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(2):e167-e172.

1. Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Sloan AE, Davis FG, Vigneau FD, Lai P, Sawaya RE. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2865-2872.

2. Schouten LJ, Rutten J, Huveneers HA, Twijnstra A. Incidence of brain metastases in a cohort of patients with carcinoma of the breast, colon, kidney, and lung and melanoma. Cancer. 2002;94(10):2698-2705.

3. Takakura K. Metastatic tumors of the central nervous system. Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin; 1982.

4. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1485-1489.

5. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Walsh JW, et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. New Engl J Med. 1990;322(8):494-500.

6. Sahgal A, Aoyama H, Kocher M, et al. Phase 3 trials of stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiation therapy for 1 to 4 brain metastases: individual patient data meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(4):710-717.

7. Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR, et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1037-1044.

8. Choosing Wisely [ASTRO]. Don’t routinely add adjuvant whole-brain radiation therapy to stereotactic radiosurgery for limited brain metastases. http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-society-radiation-oncology-adjunct-whole-brain-radiation-therapy/. Updated June 21, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

9. Aoyama H, Tago M, Shirato H, Japanese Radiation Oncology Study Group I. Stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases: secondary analysis of the JROSG 99-1 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):457-464.

10. Hoddinott SN, Bass MJ. The Dillman total design survey method. Can Fam Physician. 1986;32:2366-2368.

11. Nayak L, Lee EQ, Wen PY. Epidemiology of brain metastases. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14(1):48-54.

12. Gavrilovic IT, Posner JB. Brain metastases: epidemiology and pathophysiology. J Neurooncol. 2005;75(1):5-14.

13. Chao JH, Phillips R, Nickson JJ. Roentgen-ray therapy of cerebral metastases. Cancer. 1954;7(4):682-689.

14. Nieder C, Niewald M, Schnabel K. Treatment of brain metastases from hypernephroma. Urol Int. 1996;57(1):17-20.

15. Ryken TC, McDermott M, Robinson PD, et al. The role of steroids in the management of brain metastases: a systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Neurooncol. 2010;96(1):103-114.

16. Brown PD, Pugh S, Laack NN, et al. Memantine for the prevention of cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(10):1429-1437.

17. Gondi V, Pugh SL, Tome WA, et al. Preservation of memory with conformal avoidance of the hippocampal neural stem-cell compartment during whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases (RTOG 0933): a phase II multi-institutional trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3810-3816.

18. Slade AN, Stanic S. The impact of RTOG 0614 and RTOG 0933 trials in routine clinical practice: The US Survey of Utilization of Memantine and IMRT planning for hippocampus sparing in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;47:74-77.

19. Sahgal A, Aoyama H, Kocher M, et al. Phase 3 trials of stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain radiation therapy for 1 to 4 brain metastases: individual patient data meta-analysis. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2015;91(4):710-717.

20. Hazuka MB, Kinzie JJ. Brain metastases: results and effects of re-irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15(2):433-437.

21. Sadikov E, Bezjak A, Yi QL, et al. Value of whole-brain re-irradiation for brain metastases — single centre experience. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2007;19(7):532-538.

22. Son CH, Jimenez R, Niemierko A, Loeffler JS, Oh KS, Shih HA. outcomes after whole-brain reirradiation in patients with brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(2):e167-e172.

Distress management in cancer patients in Puerto Rico

A comprehensive, patient-centered approach is required to accomplish cancer best standards of care.1 This approach reflects the holistic conceptualization of health in which the physical, emotional, and social dimensions of the human being are considered when providing medical care. As a result, to look after all patient needs, interdisciplinary and well-coordinated interventions are recommended. Cancer patients should be provided not only with diagnostic, treatment, and follow-up clinical service, but also with the supportive assistance that may positively influence all aspects of their health.

To appraise physical, social, emotional and spiritual issues and to develop supportive interventional action plans, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends screening all cancer patients for distress.2 In particular, screening the emotional component of distress occupies a prominent place in this process because it is now recognized as the sixth vital sign in oncology.3 Even though the influence of emotional distress over cancer mortality rates and disease progression is still under scrutiny,4 its plausible implications over treatment compliance have been pointed out. Patients with higher levels of emotional distress show lower adherence to treatment and poorer health outcomes.5 Furthermore, prevalence rates of emotional distress in cancer patients from ambulatory settings6 and oncology surgical units have been studied and have provided justification for distress management.7 Studies have shown low ability among oncologists to identify patients in distress and oncologists’ tendency to judge distress higher than the patients themselves.8 As a consequence, to achieve systematic distress evaluations and appropriate referrals for care, guidelines for distress management should be implemented in clinical settings. It is recommended that tests are conducted to find brief screening instruments and procedures to assure accurate interventions according to patient specific needs.

This article presents the process of implementing a distress management program at HIMA-San Pablo Oncologic Hospital in Caguas, Puerto Rico, with particular emphasis on the management of emotional distress, which has been defined as the feeling of suffering that cancer patients may experience after diagnosis. In addition, we have included data from a pilot study that was completed for content validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to estimate depression levels in Puerto Rican cancer patients.

Methods

HIMA-San Pablo operates a group of privately owned hospitals in Puerto Rico. It established a cancer center in Caguas in 2007, recruiting a multispecialty medical faculty to provide cancer care and bone marrow transplants for adult and pediatric patients. The cancer center, currently named HIMA-San Pablo Oncologic Hospital (HSPOH), is a hospital within a hospital licensed by the Puerto Rico Department of Health. In 2007, a cancer committee was established as the steering committee to ensure the delivery of cancer care according to best standards of care. The committee took responsibility for developing all activities needed to achieve the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation under the category of Comprehensive Community Cancer Center. The committee established a psychosocial team to develop a protocol for the delivery of distress management for adult patients. (The psychosocial needs of pediatric patients are assessed through other procedures.)

To develop the protocol, principles of input-output model of research and quality analysis in health care were applied.9 The input-output model, with its origin in engineering, helped map systematic activities to transform empirical data on cancer psychosocial care into operational procedures. Focus was given to data gathering (input), information organization and analysis (throughput), and the schematization of emotional distress management care (output).

The input phase

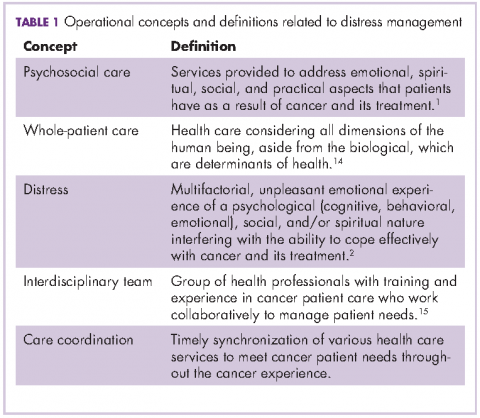

In the input phase, elements of psychosocial care and operational definitions related to distress management in general were identified through literature review (Table 1). Basic parameters for distress management were clarified, resulting in a conceptual framework based in four remarks: First, according to NCCN, distress is a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological, social, and spiritual nature. It may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its symptoms and its treatment. Its intensity may fluctuate from feelings of suffering and fear to incapacitating manifestations of anxiety and depression2 and its severity may hamper patient quality of life and treatment compliance.

Second, distress management requires the intervention of an interdisciplinary team with both medical and allied health professionals. This may include mental health specialists and other professionals with training and experience in cancer-related issues, who work with reciprocal channels of communication for the exchange of patient information.

Third, NCCN recommends using the Distress Thermometer for patient initial distress screening.10-12 It consists of a numeric scale ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (severe distress) in which patients classify their level of distress. The numeric scale is followed by a section in which patients identify areas of practical, familiar, emotional, spiritual/ religious, and physical concerns. Based on responses, interviews may follow to set distress management interventions.

Fourth, screening and assessment are different but sequential and complementary stages of distress management. Screening is viewed as a rapid strategy to identify cancer patients in distress. Assessment looks out for a broader appraisal and documentation of factors with repercussions over patient distress level and resiliency capability.13 In many instances, the patient’s emotional distress is better understood in the assessment phase.

The throughput phase

Within the throughput phase of information organization and analysis, an inventory of health professionals and other in-house consultants needed for distress management was completed. Roles and procedures for information sharing were determined, and we established collaborative agreements with professionals in the community who could contribute to distress management. Members of the psychosocial team held workshops to discuss elements of NCCN guidelines for distress management and to create an action plan for the implementation of the protocol. Data analyses were performed to create a demographic profile of the oncology population at the hospital and assess patient willingness to receive emotional support services,16 which led to the implementation of support group meetings at which additional substantive information was collected about issues affecting cancer patients’ emotions.

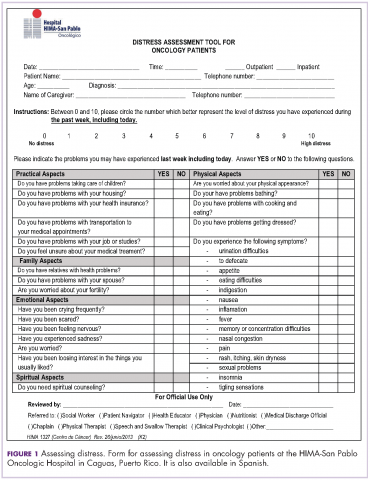

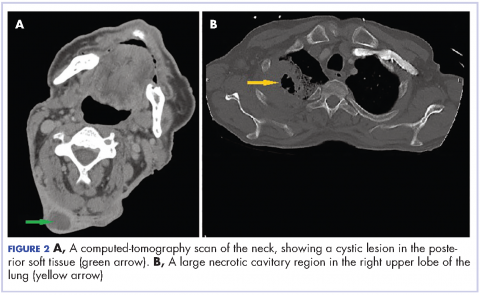

The NCCN Distress Thermometer for measuring distress was translated to Spanish. Its format was adapted, and it was identified as a distress screening tool (DST), which we named Distress Assessment Tool for Oncology Patients (Figure 1). The instrument helps for rapid screening of patient needs and proper determination of initial interventions. In addition, psychometric properties of several instruments were reviewed for instances when patient emotional distress could not be clearly determined. We decided to proceed with the validation of the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to estimate patient depression level. A proposal for content validation of the PHQ-9 was approved by the University of Puerto Rico institutional review board, and patients were recruited to participate in the pilot study.

The PHQ-9. The PHQ-9 is a self-report version of the PRIME-MD instrument developed to assess mental disorders in clinical settings. It is based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria.17 The PHQ-9 is the depression module with nine depression symptoms to check off if they become the cause of emotional impairment. Respondents categorized depression symptoms in four frequency degrees representing numeric values: 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days), 3 (nearly every day). Measures of depression severity are subsequently determined in a Likert-type scale according to numeric calculations of responses: 0-4 (none severe depression), 5-9 (mild), 10-14 (moderate), 15-19 (moderately severe), and 20-27 (severe-major depression).

The instrument is widely used because of its validity in small and large populations. It showed adequate reliability and validity in a small sample of head and neck cancer patients, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 and a correlation coefficient of 0.71.18 Similarly, it showed good performance in identifying major depression in 4264 cancer outpatients, with sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 81%, and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 25% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 99%.19 Even when administered on a touch screen computer, the instrument showed valid data of depression from patients in treatment.20

The Beck Depression Inventory. We used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) Spanish version as the gold standard measure for the validation study. It is a 22-items inventory that measures attitudes and symptoms of depression.21 It can be administered in 10 minutes and has shown good psychometric measures when administered in Spain and Puerto Rico.22, 23

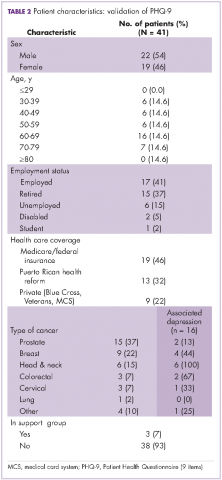

The pilot study. In all, 44 cancer patients who were receiving outpatient treatment at the radiotherapy unit agreed to participate in the study. The participants signed a consent form after the confidentiality protection measures and the main objectives of the study had been explained to them. Patients were interviewed individually during November and December 2012, with the Spanish versions of the PHQ-9 and BDI-II administered by one of two interviewers. At the beginning of each interview, the patient was asked 10 questions so that we could gather demographic data and confirm participant eligibility: aged 21 years or older, born and raised in Puerto Rico, being a Spanish speaker, and having a primary cancer diagnosis with no previous disease. Three patients were excluded from the sample because they either had cancer previously or had a recurrence or metastasis. The final sample consisted of 41 outpatients (N = 41).

Data analysis for demographics was completed with STATA v.12 software. Measures of central tendency and dispersion as well as PHQ-9 internal consistency analysis were made through Cronbach alpha with SPSS.

From a total of 41 patients surveyed, 22 (54%) were men and 19 (46%) were women, with an overall median age of 61 years. Among the men, 15 (68%) had a prostate cancer diagnosis and among women, 9 (47.4%) had a breast cancer diagnosis. In regard to health insurance, 19 (46%) had Medicare or Veterans/federal insurance coverage, and 13 (32%) had Reforma, the Puerto Rican government health insurance program partially funded by Medicaid funds. In addition, 8 participants (20%) were unemployed or disabled. As previously stated, all of the patients were in ambulatory care. Only 3 (7%) were participating in support groups.

Of all the respondents, 16 (39%) reported some level of depression. In particular, 2 (5%) showed severe-major depression, 4 (10%) moderately severe depression, and 10 (24%) moderate depression. Of those with depression, 8 (50%) were women, 8 (50%) were men. All 6 of the patients with head and neck cancer showed moderate or moderately severe depression (Table 2).

When respondent PHQ-9 scoring reflected moderate to severe depression (>10), a letter was sent to the patient’s radio-oncologist for referral to counseling and clinical psychological evaluation. All participants had access to the support group program, to a radiotherapy education program meeting weekly, and written information about their cancer diagnosis and treatment. They also were interviewed by the psychosocial coordinator or patient navigator for further assessment.

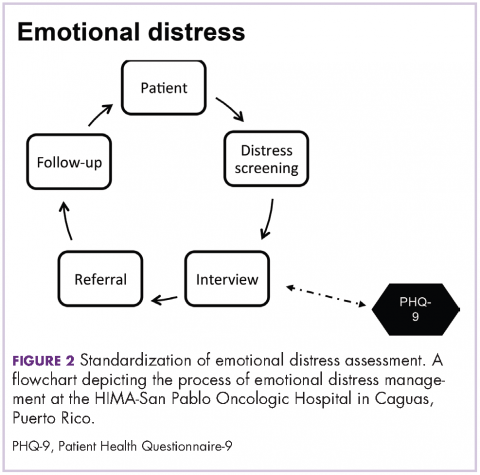

The output phase

In the output phase, a graphic representing the process of emotional assessment at the institution was created and then modified. PHQ-9 was added to the process when it was found suitable to assess level of depression contributing to the identification of patients requiring psychological and psychiatric assistance which by other means would be missed. PHQ-9 was useful in the busy clinical setting as it was completed, scored and interpreted in minutes. It showed the potential for routine evaluations when looking to identify improvement or deterioration in depression levels thus helping to monitor responses to treatment and providing insights for follow up interventions. As stated by NCCN guidelines, distress should be monitored, documented and managed at all stages of the cancer continuum.

Results and discussion

The protocol for distress management at HSPOH is based on the 2013 NCCN guidelines. Cancer patients are screened for levels of distress in all settings (inpatients and outpatients). Screening is held with the DST Spanish translation at the moment of diagnosis or as soon as possible after a diagnosis is made. Screening for distress is also done before or after surgery, in recurrence or progression, and when clinically indicated. Patients are informed that distress management is an essential part of their care and are encouraged to provide information so that we can make a proper need assessment.

Patients are screened by the psychosocial coordinator or patient navigator who administers the DST followed by in-depth interviews for additional appraisal. An action plan is designed based on patient needs, which include their intervention and the intervention of other members of the psychosocial team from the institution and/or from the community. Additional in-house health professionals contributing in distress management include, but are not limited to: physicians; clinical psychologists; health educators; social workers; dietitians; chaplains; and physical, respiratory, speech, and/or swallow therapists. Follow-up and rescreening sessions are scheduled to assure coordination of services between those health professionals as well as to secure continuity of distress management during all stages of the cancer continuum.

The results of the DST are filed in patient medical records. Members of the psychosocial team also document their interventions in the patient medical record, which helps in the exchange of information among the cancer care team. The psychosocial team meets once a month – or as required for extraordinary cases – to review and discuss the cases, determine the best options for distress management, and identify areas for psychosocial care improvement. Those findings and the results of distress management in patient level of satisfaction are then reported and discussed quarterly by the psychosocial coordinator and the cancer committee.

Figure 2 shows in what phase of emotional distress assessment the PHQ-9 was included. Patients reporting four or more of the six areas of concern related to emotional distress in the DST (Figure 1) are automatically referred to a mental health specialist. But when patients report three areas of concern with no clear data on their specific level of depression, PHQ-9 is administered to differentiate those who need a mental health specialist from those who could be adequately supported by health education and support group interventions. In this way detrimental outcomes such as duplicity and over or underuse of services and resources are reduced. In addition, it is recognized that using an interview after the administration of the DST to determine distress management actions does not always provide enough information about a patient’s emotional circumstances and previous comorbidities. Patient responses during interviews may be influenced by the patient’s level of literacy, verbal comprehension, and communication style,24 so emotional distress can go unrecognized during interviews, resulting in delays for treatment and supportive care.

National guidelines in oncology consider such socio-ecological models emphasizing the delivery of patient-centered, interdisciplinary, and evidence-based care. That does not mean that institutions should apply protocols of psychosocial care as previously developed, but that they should test, review, adapt, and improve them during the implementation of the care. In fact, NCCN encourages conducting trials to examine protocols, screening instruments, and models of intervention to determine applicability to particular settings.2

Findings from a study by NCCN member institutions to evaluate progress of implementing distress management guidelines found that 53% (n = 8) of respondent institutions conducted routine distress screening. Of those, 37.5% (3) relied only on interviews. That finding is of concern because if interviews are not standardized and have not been systematically evaluated, then their sensitivity and specificity in identifying distressed patients is unknown.26 Accordingly, the process described in this article and the PHQ-9 validation was an effort to standardize emotional distress management, and was underlined as an achievement during the CoC accreditation visit to the cancer center in December 2013. The hospital was accredited as a comprehensive community cancer center with gold commendations, becoming the first privately owned hospital in Puerto Rico to achieve the accreditation.

1. Commission on Cancer, American College of Surgeons. Cancer Programs Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Version 1.2.1. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx. Published 2012. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): Distress management. Version I. 2012. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#supportive. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Bultz BD, Groff SL. Screening for distress, the 6th vital sign in oncology: from theory to practice: http://www.oncologyex.com/issue/2009/vol8_no1/8_comment2_1.html. Published February 2009. Accessed February 16, 2017.

4. Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009;115:5349-5361.

5. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Int Med. 2000;160:2101-2107.

6. Jadoon NA, Munir W, Shahzad MA, Choudhry ZS. Assessment of depression and anxiety in adult cancer outpatients: a cross sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:594.

7. Fisher D, Wedel B. Anxiety and depression disorders in cancer patients: incidence, diagnosis and therapy. Mag Eur Med Oncol. 2012;5:52-54.

8. Sollner W, DeVries A, Steixner E, et al. How successful are oncologists in identifying patient distress, perceived social support, and in need for psychosocial counselling? Br J Cancer. 2001;84:179-185.

9. Scott RD, Solomon SL, McGowan JE. Applying economic principles to health care: special issue. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:282-285.

10. Adler NE, Page AEK. A model for delivering psychosocial health services. In: Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2008.

11. Holland JC, Alici Y. Management of distress in cancer patients. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:4-12.

12. Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103:1494-1502.

13. Maihoff SE. Assessment. In Washington CM, Leaver D, eds. Principles and practice of radiation therapy. St Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2004:243-264.

14. National Academy of Sciences. Adler NE, Page AEK, eds. Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK4015/. Published 2008. Accessed February 22, 2012.

15. Nancarrow SA, Booth A, Ariss

16. Baker-Glenn EA, Park B, Granger L, Symonds P, Mitchell AJ. Desire for psychological support in cancer patients with depression or distress: validation of a simple help question. Psychooncology. 2011;20:525-531.

17. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

18. Omoro SA, Fann JR, Weymuller EA, Macharia IM, Yueh B. Swahili translation and validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression scale in the Kenyan head and neck cancer patient population. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:367-381.

19. Thekkumpurath P, Walker J, Butcher I, et al. Screening for major depression on cancer outpatients: the diagnostic accuracy of the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire. Cancer. 2011;117:218-227.

20. Fann JR, Berry DL, Wolpin S, et al. Depression screening using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 administered on a touch screen computer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:14-22.

21. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:651-571.

22. Sanz J, Perdigón AL, Vázquez C. The Spanish adaptation of Beck’s Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II): psychometric properties in the general population. Clínica y Salud. 2003;14:249-280.

23. Bonilla J, Bernal G, Santos A, Santos D. A revised Spanish version of the Beck Depression Inventory: psychometric properties with a Puerto Rican sample of college students. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60:119-130.

24. Alcántara C, Gone JP. Multicultural issues in the clinical interview and diagnostic process. In Leong FTL, ed. APA handbook of multicultural psychology. Vol 2. Applications and training. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2014:153-163.

25. Sharma M, Romas JA. Theoretical foundations of health education and health promotion. 2nd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Barlett Learning; 2012.

26. Jacobsen PB, Ransom S. Implementation of NCCN distress management guidelines by member institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:99-103.

A comprehensive, patient-centered approach is required to accomplish cancer best standards of care.1 This approach reflects the holistic conceptualization of health in which the physical, emotional, and social dimensions of the human being are considered when providing medical care. As a result, to look after all patient needs, interdisciplinary and well-coordinated interventions are recommended. Cancer patients should be provided not only with diagnostic, treatment, and follow-up clinical service, but also with the supportive assistance that may positively influence all aspects of their health.

To appraise physical, social, emotional and spiritual issues and to develop supportive interventional action plans, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends screening all cancer patients for distress.2 In particular, screening the emotional component of distress occupies a prominent place in this process because it is now recognized as the sixth vital sign in oncology.3 Even though the influence of emotional distress over cancer mortality rates and disease progression is still under scrutiny,4 its plausible implications over treatment compliance have been pointed out. Patients with higher levels of emotional distress show lower adherence to treatment and poorer health outcomes.5 Furthermore, prevalence rates of emotional distress in cancer patients from ambulatory settings6 and oncology surgical units have been studied and have provided justification for distress management.7 Studies have shown low ability among oncologists to identify patients in distress and oncologists’ tendency to judge distress higher than the patients themselves.8 As a consequence, to achieve systematic distress evaluations and appropriate referrals for care, guidelines for distress management should be implemented in clinical settings. It is recommended that tests are conducted to find brief screening instruments and procedures to assure accurate interventions according to patient specific needs.

This article presents the process of implementing a distress management program at HIMA-San Pablo Oncologic Hospital in Caguas, Puerto Rico, with particular emphasis on the management of emotional distress, which has been defined as the feeling of suffering that cancer patients may experience after diagnosis. In addition, we have included data from a pilot study that was completed for content validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to estimate depression levels in Puerto Rican cancer patients.

Methods

HIMA-San Pablo operates a group of privately owned hospitals in Puerto Rico. It established a cancer center in Caguas in 2007, recruiting a multispecialty medical faculty to provide cancer care and bone marrow transplants for adult and pediatric patients. The cancer center, currently named HIMA-San Pablo Oncologic Hospital (HSPOH), is a hospital within a hospital licensed by the Puerto Rico Department of Health. In 2007, a cancer committee was established as the steering committee to ensure the delivery of cancer care according to best standards of care. The committee took responsibility for developing all activities needed to achieve the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation under the category of Comprehensive Community Cancer Center. The committee established a psychosocial team to develop a protocol for the delivery of distress management for adult patients. (The psychosocial needs of pediatric patients are assessed through other procedures.)

To develop the protocol, principles of input-output model of research and quality analysis in health care were applied.9 The input-output model, with its origin in engineering, helped map systematic activities to transform empirical data on cancer psychosocial care into operational procedures. Focus was given to data gathering (input), information organization and analysis (throughput), and the schematization of emotional distress management care (output).

The input phase

In the input phase, elements of psychosocial care and operational definitions related to distress management in general were identified through literature review (Table 1). Basic parameters for distress management were clarified, resulting in a conceptual framework based in four remarks: First, according to NCCN, distress is a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological, social, and spiritual nature. It may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its symptoms and its treatment. Its intensity may fluctuate from feelings of suffering and fear to incapacitating manifestations of anxiety and depression2 and its severity may hamper patient quality of life and treatment compliance.

Second, distress management requires the intervention of an interdisciplinary team with both medical and allied health professionals. This may include mental health specialists and other professionals with training and experience in cancer-related issues, who work with reciprocal channels of communication for the exchange of patient information.

Third, NCCN recommends using the Distress Thermometer for patient initial distress screening.10-12 It consists of a numeric scale ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (severe distress) in which patients classify their level of distress. The numeric scale is followed by a section in which patients identify areas of practical, familiar, emotional, spiritual/ religious, and physical concerns. Based on responses, interviews may follow to set distress management interventions.

Fourth, screening and assessment are different but sequential and complementary stages of distress management. Screening is viewed as a rapid strategy to identify cancer patients in distress. Assessment looks out for a broader appraisal and documentation of factors with repercussions over patient distress level and resiliency capability.13 In many instances, the patient’s emotional distress is better understood in the assessment phase.

The throughput phase

Within the throughput phase of information organization and analysis, an inventory of health professionals and other in-house consultants needed for distress management was completed. Roles and procedures for information sharing were determined, and we established collaborative agreements with professionals in the community who could contribute to distress management. Members of the psychosocial team held workshops to discuss elements of NCCN guidelines for distress management and to create an action plan for the implementation of the protocol. Data analyses were performed to create a demographic profile of the oncology population at the hospital and assess patient willingness to receive emotional support services,16 which led to the implementation of support group meetings at which additional substantive information was collected about issues affecting cancer patients’ emotions.

The NCCN Distress Thermometer for measuring distress was translated to Spanish. Its format was adapted, and it was identified as a distress screening tool (DST), which we named Distress Assessment Tool for Oncology Patients (Figure 1). The instrument helps for rapid screening of patient needs and proper determination of initial interventions. In addition, psychometric properties of several instruments were reviewed for instances when patient emotional distress could not be clearly determined. We decided to proceed with the validation of the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to estimate patient depression level. A proposal for content validation of the PHQ-9 was approved by the University of Puerto Rico institutional review board, and patients were recruited to participate in the pilot study.

The PHQ-9. The PHQ-9 is a self-report version of the PRIME-MD instrument developed to assess mental disorders in clinical settings. It is based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria.17 The PHQ-9 is the depression module with nine depression symptoms to check off if they become the cause of emotional impairment. Respondents categorized depression symptoms in four frequency degrees representing numeric values: 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days), 3 (nearly every day). Measures of depression severity are subsequently determined in a Likert-type scale according to numeric calculations of responses: 0-4 (none severe depression), 5-9 (mild), 10-14 (moderate), 15-19 (moderately severe), and 20-27 (severe-major depression).

The instrument is widely used because of its validity in small and large populations. It showed adequate reliability and validity in a small sample of head and neck cancer patients, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 and a correlation coefficient of 0.71.18 Similarly, it showed good performance in identifying major depression in 4264 cancer outpatients, with sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 81%, and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 25% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 99%.19 Even when administered on a touch screen computer, the instrument showed valid data of depression from patients in treatment.20