User login

Smoldering myeloma progressed more rapidly in patients with elevated BMIs

An elevated body mass index appears to be a risk factor for progression of smoldering multiple myeloma, according to Wilson I. Gonsalves, MD, and his colleagues at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The findings, based on median follow up data of 106 months from 306 patients diagnosed with smoldering multiple myeloma from 2000-2010 at the Mayo Clinic, need to be confirmed in larger studies. Nevertheless, the results imply that patient weight is a potentially modifiable risk factor for progression from smoldering disease to multiple myeloma, Dr. Gonsalves and his colleagues wrote.

At initial evaluation, 28% of patients had myeloma defining events, such as a serum free light chain ratio greater than 100 or over 60% clonal bone marrow plasma cells. Myeloma defining events were present in 17% of patients with normal BMIs and 33% of patients with elevated BMIs, a statistically significant difference (P = .011).

When the analysis was limited to the 187 patients without myeloma-defining events at initial evaluation, the 2-year rate of progression to symptomatic multiple myeloma was 15% in those with a normal BMI and 33% in those with an elevated BMI (P = .013).

In a multivariable model, only elevated BMI (P = .004) and increasing clonal bone marrow plasma cells (P = .001) were statistically significant in predicting 2-year progression to multiple myeloma.

At last follow-up, 66% of patients had progressed to symptomatic multiple myeloma.

Dr. Gonsalves had no relationships to disclose.

The impact of body mass index on the risk of early progression of smoldering multiple myeloma to symptomatic myeloma. 2017 ASCO annual meeting. Abstract No: 8032.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

An elevated body mass index appears to be a risk factor for progression of smoldering multiple myeloma, according to Wilson I. Gonsalves, MD, and his colleagues at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The findings, based on median follow up data of 106 months from 306 patients diagnosed with smoldering multiple myeloma from 2000-2010 at the Mayo Clinic, need to be confirmed in larger studies. Nevertheless, the results imply that patient weight is a potentially modifiable risk factor for progression from smoldering disease to multiple myeloma, Dr. Gonsalves and his colleagues wrote.

At initial evaluation, 28% of patients had myeloma defining events, such as a serum free light chain ratio greater than 100 or over 60% clonal bone marrow plasma cells. Myeloma defining events were present in 17% of patients with normal BMIs and 33% of patients with elevated BMIs, a statistically significant difference (P = .011).

When the analysis was limited to the 187 patients without myeloma-defining events at initial evaluation, the 2-year rate of progression to symptomatic multiple myeloma was 15% in those with a normal BMI and 33% in those with an elevated BMI (P = .013).

In a multivariable model, only elevated BMI (P = .004) and increasing clonal bone marrow plasma cells (P = .001) were statistically significant in predicting 2-year progression to multiple myeloma.

At last follow-up, 66% of patients had progressed to symptomatic multiple myeloma.

Dr. Gonsalves had no relationships to disclose.

The impact of body mass index on the risk of early progression of smoldering multiple myeloma to symptomatic myeloma. 2017 ASCO annual meeting. Abstract No: 8032.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

An elevated body mass index appears to be a risk factor for progression of smoldering multiple myeloma, according to Wilson I. Gonsalves, MD, and his colleagues at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The findings, based on median follow up data of 106 months from 306 patients diagnosed with smoldering multiple myeloma from 2000-2010 at the Mayo Clinic, need to be confirmed in larger studies. Nevertheless, the results imply that patient weight is a potentially modifiable risk factor for progression from smoldering disease to multiple myeloma, Dr. Gonsalves and his colleagues wrote.

At initial evaluation, 28% of patients had myeloma defining events, such as a serum free light chain ratio greater than 100 or over 60% clonal bone marrow plasma cells. Myeloma defining events were present in 17% of patients with normal BMIs and 33% of patients with elevated BMIs, a statistically significant difference (P = .011).

When the analysis was limited to the 187 patients without myeloma-defining events at initial evaluation, the 2-year rate of progression to symptomatic multiple myeloma was 15% in those with a normal BMI and 33% in those with an elevated BMI (P = .013).

In a multivariable model, only elevated BMI (P = .004) and increasing clonal bone marrow plasma cells (P = .001) were statistically significant in predicting 2-year progression to multiple myeloma.

At last follow-up, 66% of patients had progressed to symptomatic multiple myeloma.

Dr. Gonsalves had no relationships to disclose.

The impact of body mass index on the risk of early progression of smoldering multiple myeloma to symptomatic myeloma. 2017 ASCO annual meeting. Abstract No: 8032.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

FROM ASCO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 2-year rate of progression from smoldering disease to symptomatic multiple myeloma was 16% in patients with a normal BMI and 42% in patients with an elevated BMI (P less than 0.0001).

Data source: Median follow up data of 106 months from 306 patients diagnosed with smoldering multiple myeloma during 2000-2010 at the Mayo Clinic.

Disclosures: Dr. Gonsalves had no relationships to disclose.

Citation: The impact of body mass index on the risk of early progression of smoldering multiple myeloma to symptomatic myeloma. 2017 ASCO annual meeting. Abstract No: 8032.

Postop satisfaction scores not tied to restricted opioid prescribing

Reduced opioid prescribing did not correlate with inpatient pain management scores, a study has shown.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced recently that, as of 2018, pain management will no longer be rated in the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, citing concerns that patient satisfaction surveys given at the time of postoperative discharge incentivizes clinicians to over-prescribe pain medication. Surgical patients are key contributors to HCAHPS scores, and opioids account for almost 40% of surgical prescriptions, according to the study.

A new study throws some shade on the CMS decision to delete pain management from the HCAHPS survey.

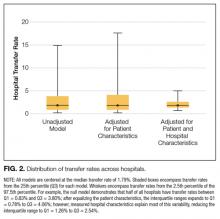

Pain management scores were calculated as the percentage of patients who reported that their pain was “always” well controlled. The pain dimension was calculated from the number of opioid prescriptions and also pain management scores compared to national benchmarks. Hospitals were then grouped into quintiles according to opioid prescriptions measured in oral morphine equivalents. The first quintile has the lowest number of prescriptions.

Unadjusted comparisons showed no significant differences in pain management or pain dimension scores between the first and fifth quintiles of hospitals. For pain management scores that ranked hospital staff as always controlling pain, the first quintile had a mean score of 69.5 (95% confidence interval, 66.7-71.7) out of 100, compared with 69.1 for the fifth quintile (95% CI, 67.2-71.4). On a scale of 1-10, pain dimension scores in the first quintile averaged 1.9 (mean 95% CI, 1.5-2.0), compared with 1.4 in the fifth quintile (mean 95% CI, 0.9-1.9).

So, for these institutions, the number of pain prescriptions was not correlated with HCAHPS scores for pain management. The study suggests that the concern that reducing opioid prescriptions may have a negative impact on patient satisfaction assessments may not be realized.

Other analyses controlling for a variety of comorbidities also showed no correlations between pain management scores and opioid prescribing. Of the surgeries considered – orthopedic, general, gynecologic, cancer, cardiac, and vascular – gynecologic procedures were most likely to be associated with improved pain management and pain dimension scores.

Dr. Brummett disclosed relationships with Tonix and Neuros Medical. He also holds a patent for peripheral perineural dexmedetomidine. Mr. Syrjamaki and Dr. Dupree received support from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for their respective roles in the Michigan Value Collaborative. Dr. Waljee is an unpaid consultant for 3MHealth.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Reduced opioid prescribing did not correlate with inpatient pain management scores, a study has shown.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced recently that, as of 2018, pain management will no longer be rated in the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, citing concerns that patient satisfaction surveys given at the time of postoperative discharge incentivizes clinicians to over-prescribe pain medication. Surgical patients are key contributors to HCAHPS scores, and opioids account for almost 40% of surgical prescriptions, according to the study.

A new study throws some shade on the CMS decision to delete pain management from the HCAHPS survey.

Pain management scores were calculated as the percentage of patients who reported that their pain was “always” well controlled. The pain dimension was calculated from the number of opioid prescriptions and also pain management scores compared to national benchmarks. Hospitals were then grouped into quintiles according to opioid prescriptions measured in oral morphine equivalents. The first quintile has the lowest number of prescriptions.

Unadjusted comparisons showed no significant differences in pain management or pain dimension scores between the first and fifth quintiles of hospitals. For pain management scores that ranked hospital staff as always controlling pain, the first quintile had a mean score of 69.5 (95% confidence interval, 66.7-71.7) out of 100, compared with 69.1 for the fifth quintile (95% CI, 67.2-71.4). On a scale of 1-10, pain dimension scores in the first quintile averaged 1.9 (mean 95% CI, 1.5-2.0), compared with 1.4 in the fifth quintile (mean 95% CI, 0.9-1.9).

So, for these institutions, the number of pain prescriptions was not correlated with HCAHPS scores for pain management. The study suggests that the concern that reducing opioid prescriptions may have a negative impact on patient satisfaction assessments may not be realized.

Other analyses controlling for a variety of comorbidities also showed no correlations between pain management scores and opioid prescribing. Of the surgeries considered – orthopedic, general, gynecologic, cancer, cardiac, and vascular – gynecologic procedures were most likely to be associated with improved pain management and pain dimension scores.

Dr. Brummett disclosed relationships with Tonix and Neuros Medical. He also holds a patent for peripheral perineural dexmedetomidine. Mr. Syrjamaki and Dr. Dupree received support from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for their respective roles in the Michigan Value Collaborative. Dr. Waljee is an unpaid consultant for 3MHealth.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Reduced opioid prescribing did not correlate with inpatient pain management scores, a study has shown.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced recently that, as of 2018, pain management will no longer be rated in the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, citing concerns that patient satisfaction surveys given at the time of postoperative discharge incentivizes clinicians to over-prescribe pain medication. Surgical patients are key contributors to HCAHPS scores, and opioids account for almost 40% of surgical prescriptions, according to the study.

A new study throws some shade on the CMS decision to delete pain management from the HCAHPS survey.

Pain management scores were calculated as the percentage of patients who reported that their pain was “always” well controlled. The pain dimension was calculated from the number of opioid prescriptions and also pain management scores compared to national benchmarks. Hospitals were then grouped into quintiles according to opioid prescriptions measured in oral morphine equivalents. The first quintile has the lowest number of prescriptions.

Unadjusted comparisons showed no significant differences in pain management or pain dimension scores between the first and fifth quintiles of hospitals. For pain management scores that ranked hospital staff as always controlling pain, the first quintile had a mean score of 69.5 (95% confidence interval, 66.7-71.7) out of 100, compared with 69.1 for the fifth quintile (95% CI, 67.2-71.4). On a scale of 1-10, pain dimension scores in the first quintile averaged 1.9 (mean 95% CI, 1.5-2.0), compared with 1.4 in the fifth quintile (mean 95% CI, 0.9-1.9).

So, for these institutions, the number of pain prescriptions was not correlated with HCAHPS scores for pain management. The study suggests that the concern that reducing opioid prescriptions may have a negative impact on patient satisfaction assessments may not be realized.

Other analyses controlling for a variety of comorbidities also showed no correlations between pain management scores and opioid prescribing. Of the surgeries considered – orthopedic, general, gynecologic, cancer, cardiac, and vascular – gynecologic procedures were most likely to be associated with improved pain management and pain dimension scores.

Dr. Brummett disclosed relationships with Tonix and Neuros Medical. He also holds a patent for peripheral perineural dexmedetomidine. Mr. Syrjamaki and Dr. Dupree received support from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for their respective roles in the Michigan Value Collaborative. Dr. Waljee is an unpaid consultant for 3MHealth.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Key clinical point:

Major finding: No significant differences between top and bottom quintiles of 47 Michigan hospitals’ opioid prescribing patterns existed when comparing their HCAHPS scores.

Data source: Pharmacy and insurance claims and HCAHPS pain management for 31,481 surgery patients between 2012 and 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Brummett disclosed relationships with Tonix and Neuros Medical. He also holds a patent for peripheral perineural dexmedetomidine. Mr. Syrjamaki and Dr. Dupree received support from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for their respective roles in the Michigan Value Collaborative. Dr. Waljee is an unpaid consultant for 3MHealth.

GOLD guidelines for the management of COPD – 2017 update

Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death in the United States1 and a major cause of mortality and morbidity around the world. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) released a new “2017 Report”2 with modified recommendations for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. The report contains several changes that are relevant to the primary care provider that will be outlined below.

Redefining COPD

GOLD’s definition of COPD was changed in its 2017 Report: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitations that are due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.” The report emphasizes that “COPD may be punctuated by periods of acute worsening of respiratory symptoms, called exacerbations.” Note that the terms “emphysema” and “chronic bronchitis” have been removed in favor of a more comprehensive description of the pathophysiology of COPD. Importantly, the report states that cough and sputum production for at least 3 months in each of 2 consecutive years, previously accepted as diagnostic criteria, are present in only a minority of patients. It is noted that chronic respiratory symptoms may exist without spirometric changes and many patients (usually smokers) have structural evidence of COPD without airflow limitation.

Changes to COPD initial assessment

The primary criterion for diagnosis is unchanged: post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.70. Spirometry remains important to confirm the diagnosis in those with classic symptoms of dyspnea, chronic cough, and/or sputum production with a history of exposure to noxious particles or gases.

The GOLD assessment system previously incorporated spirometry and included an “ABCD” system such that patients in group A are least severe. Spirometry has been progressively deemphasized in favor of symptom-based classification and the 2017 Report, for the first time, dissociates spirometric findings from severity classification.

The new system uses symptom severity and exacerbation risk to classify COPD. Two specific standardized COPD symptom measurement tools, The Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) questionnaire and COPD Assessment Test (CAT), are reported by GOLD as the most widely used. Low symptom severity is considered an mMRC less than or equal to 1 or CAT less than or equal to 9, high symptom severity is considered an mMRC greater than or equal to 2 or CAT greater than or equal to 10. Low risk of exacerbation is defined as no more than one exacerbation not resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months; high risk of exacerbation is defined as at least two exacerbations or any exacerbations resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months. Symptom severity and exacerbation risk is divided into four quadrants:

• GOLD group A: Low symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group B: High symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group C: Low symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group D: High symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

Changes to prevention and management of stable COPD

Smoking cessation remains important in the prevention of COPD. The 2017 Report reflects the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s guidelines for smoking cessation: Offer nicotine replacement, cessation counseling, and pharmacotherapy (varenicline, bupropion or nortriptyline). There is insufficient evidence to support the use of e-cigarettes. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are recommended. Pulmonary rehabilitation remains important.

The 2017 Report includes an expanded discussion of COPD medications. The role of short-acting bronchodilators (SABD) in COPD remains prominent. Changes include a stronger recommendation to use combination short-acting beta-agonists and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SABA/SAMA) as these seem to be superior to SABD monotherapy in improving symptoms and FEV1.

There were several changes to the pharmacologic treatment algorithm. For the first time, GOLD proposes escalation strategies. Preference is given to LABA/LAMA (long-acting beta-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonists) combinations over LABA/ICS (long-acting beta-agonist/inhaled corticosteroid) combinations as a mainstay of treatment. The rationale for this change is that LABA/LAMAs give greater bronchodilation compared with LABA/ICS, and one study showed a decreased rate of exacerbations compared to LABA/ICS in patients with a history of exacerbations. In addition, patients with COPD who receive ICS appear to have a higher risk of developing pneumonia. GOLD recommendations are:

• Group A: Start with single bronchodilator (short- or long-acting), escalate to alternative class of bronchodilator if necessary.

• Group B: Start with LABA or LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA if symptoms persist.

• Group C: Start with LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LABA/ICS if exacerbations continue.

• Group D: Start with LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LAMA monotherapy, escalate to LABA/LAMA/ICS (preferred) or try LABA/ICS before escalating to LAMA/LABA/ICS if symptoms persist or exacerbations continue; roflumilast and/or a macrolide may be considered if further exacerbations occur with LABA/LAMA/ICS.

Bottom line

1. GOLD classification of COPD severity is now based on clinical criteria alone: symptom assessment and risk for exacerbation.

2. SABA/SAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to either SABA or SAMA alone.

3. Patients in group A (milder symptoms, low exacerbation risk) may be initiated on either short- or long-acting bronchodilator therapy.

4. Patients in group B (milder symptoms, increased exacerbation risk) should be initiated on LAMA monotherapy.

5. LABA/LAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to LABA/ICS combination therapy and should be used when long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy fails to control symptoms or reduce exacerbations.

References

1. CDC MMWR 11/23/12

2. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2017 at http://goldcopd.org (accessed 3/10/2017)

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Lent is chief resident in the program.

Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death in the United States1 and a major cause of mortality and morbidity around the world. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) released a new “2017 Report”2 with modified recommendations for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. The report contains several changes that are relevant to the primary care provider that will be outlined below.

Redefining COPD

GOLD’s definition of COPD was changed in its 2017 Report: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitations that are due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.” The report emphasizes that “COPD may be punctuated by periods of acute worsening of respiratory symptoms, called exacerbations.” Note that the terms “emphysema” and “chronic bronchitis” have been removed in favor of a more comprehensive description of the pathophysiology of COPD. Importantly, the report states that cough and sputum production for at least 3 months in each of 2 consecutive years, previously accepted as diagnostic criteria, are present in only a minority of patients. It is noted that chronic respiratory symptoms may exist without spirometric changes and many patients (usually smokers) have structural evidence of COPD without airflow limitation.

Changes to COPD initial assessment

The primary criterion for diagnosis is unchanged: post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.70. Spirometry remains important to confirm the diagnosis in those with classic symptoms of dyspnea, chronic cough, and/or sputum production with a history of exposure to noxious particles or gases.

The GOLD assessment system previously incorporated spirometry and included an “ABCD” system such that patients in group A are least severe. Spirometry has been progressively deemphasized in favor of symptom-based classification and the 2017 Report, for the first time, dissociates spirometric findings from severity classification.

The new system uses symptom severity and exacerbation risk to classify COPD. Two specific standardized COPD symptom measurement tools, The Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) questionnaire and COPD Assessment Test (CAT), are reported by GOLD as the most widely used. Low symptom severity is considered an mMRC less than or equal to 1 or CAT less than or equal to 9, high symptom severity is considered an mMRC greater than or equal to 2 or CAT greater than or equal to 10. Low risk of exacerbation is defined as no more than one exacerbation not resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months; high risk of exacerbation is defined as at least two exacerbations or any exacerbations resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months. Symptom severity and exacerbation risk is divided into four quadrants:

• GOLD group A: Low symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group B: High symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group C: Low symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group D: High symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

Changes to prevention and management of stable COPD

Smoking cessation remains important in the prevention of COPD. The 2017 Report reflects the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s guidelines for smoking cessation: Offer nicotine replacement, cessation counseling, and pharmacotherapy (varenicline, bupropion or nortriptyline). There is insufficient evidence to support the use of e-cigarettes. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are recommended. Pulmonary rehabilitation remains important.

The 2017 Report includes an expanded discussion of COPD medications. The role of short-acting bronchodilators (SABD) in COPD remains prominent. Changes include a stronger recommendation to use combination short-acting beta-agonists and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SABA/SAMA) as these seem to be superior to SABD monotherapy in improving symptoms and FEV1.

There were several changes to the pharmacologic treatment algorithm. For the first time, GOLD proposes escalation strategies. Preference is given to LABA/LAMA (long-acting beta-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonists) combinations over LABA/ICS (long-acting beta-agonist/inhaled corticosteroid) combinations as a mainstay of treatment. The rationale for this change is that LABA/LAMAs give greater bronchodilation compared with LABA/ICS, and one study showed a decreased rate of exacerbations compared to LABA/ICS in patients with a history of exacerbations. In addition, patients with COPD who receive ICS appear to have a higher risk of developing pneumonia. GOLD recommendations are:

• Group A: Start with single bronchodilator (short- or long-acting), escalate to alternative class of bronchodilator if necessary.

• Group B: Start with LABA or LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA if symptoms persist.

• Group C: Start with LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LABA/ICS if exacerbations continue.

• Group D: Start with LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LAMA monotherapy, escalate to LABA/LAMA/ICS (preferred) or try LABA/ICS before escalating to LAMA/LABA/ICS if symptoms persist or exacerbations continue; roflumilast and/or a macrolide may be considered if further exacerbations occur with LABA/LAMA/ICS.

Bottom line

1. GOLD classification of COPD severity is now based on clinical criteria alone: symptom assessment and risk for exacerbation.

2. SABA/SAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to either SABA or SAMA alone.

3. Patients in group A (milder symptoms, low exacerbation risk) may be initiated on either short- or long-acting bronchodilator therapy.

4. Patients in group B (milder symptoms, increased exacerbation risk) should be initiated on LAMA monotherapy.

5. LABA/LAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to LABA/ICS combination therapy and should be used when long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy fails to control symptoms or reduce exacerbations.

References

1. CDC MMWR 11/23/12

2. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2017 at http://goldcopd.org (accessed 3/10/2017)

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Lent is chief resident in the program.

Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death in the United States1 and a major cause of mortality and morbidity around the world. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) released a new “2017 Report”2 with modified recommendations for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. The report contains several changes that are relevant to the primary care provider that will be outlined below.

Redefining COPD

GOLD’s definition of COPD was changed in its 2017 Report: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitations that are due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.” The report emphasizes that “COPD may be punctuated by periods of acute worsening of respiratory symptoms, called exacerbations.” Note that the terms “emphysema” and “chronic bronchitis” have been removed in favor of a more comprehensive description of the pathophysiology of COPD. Importantly, the report states that cough and sputum production for at least 3 months in each of 2 consecutive years, previously accepted as diagnostic criteria, are present in only a minority of patients. It is noted that chronic respiratory symptoms may exist without spirometric changes and many patients (usually smokers) have structural evidence of COPD without airflow limitation.

Changes to COPD initial assessment

The primary criterion for diagnosis is unchanged: post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.70. Spirometry remains important to confirm the diagnosis in those with classic symptoms of dyspnea, chronic cough, and/or sputum production with a history of exposure to noxious particles or gases.

The GOLD assessment system previously incorporated spirometry and included an “ABCD” system such that patients in group A are least severe. Spirometry has been progressively deemphasized in favor of symptom-based classification and the 2017 Report, for the first time, dissociates spirometric findings from severity classification.

The new system uses symptom severity and exacerbation risk to classify COPD. Two specific standardized COPD symptom measurement tools, The Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) questionnaire and COPD Assessment Test (CAT), are reported by GOLD as the most widely used. Low symptom severity is considered an mMRC less than or equal to 1 or CAT less than or equal to 9, high symptom severity is considered an mMRC greater than or equal to 2 or CAT greater than or equal to 10. Low risk of exacerbation is defined as no more than one exacerbation not resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months; high risk of exacerbation is defined as at least two exacerbations or any exacerbations resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months. Symptom severity and exacerbation risk is divided into four quadrants:

• GOLD group A: Low symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group B: High symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group C: Low symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group D: High symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

Changes to prevention and management of stable COPD

Smoking cessation remains important in the prevention of COPD. The 2017 Report reflects the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s guidelines for smoking cessation: Offer nicotine replacement, cessation counseling, and pharmacotherapy (varenicline, bupropion or nortriptyline). There is insufficient evidence to support the use of e-cigarettes. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are recommended. Pulmonary rehabilitation remains important.

The 2017 Report includes an expanded discussion of COPD medications. The role of short-acting bronchodilators (SABD) in COPD remains prominent. Changes include a stronger recommendation to use combination short-acting beta-agonists and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SABA/SAMA) as these seem to be superior to SABD monotherapy in improving symptoms and FEV1.

There were several changes to the pharmacologic treatment algorithm. For the first time, GOLD proposes escalation strategies. Preference is given to LABA/LAMA (long-acting beta-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonists) combinations over LABA/ICS (long-acting beta-agonist/inhaled corticosteroid) combinations as a mainstay of treatment. The rationale for this change is that LABA/LAMAs give greater bronchodilation compared with LABA/ICS, and one study showed a decreased rate of exacerbations compared to LABA/ICS in patients with a history of exacerbations. In addition, patients with COPD who receive ICS appear to have a higher risk of developing pneumonia. GOLD recommendations are:

• Group A: Start with single bronchodilator (short- or long-acting), escalate to alternative class of bronchodilator if necessary.

• Group B: Start with LABA or LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA if symptoms persist.

• Group C: Start with LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LABA/ICS if exacerbations continue.

• Group D: Start with LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LAMA monotherapy, escalate to LABA/LAMA/ICS (preferred) or try LABA/ICS before escalating to LAMA/LABA/ICS if symptoms persist or exacerbations continue; roflumilast and/or a macrolide may be considered if further exacerbations occur with LABA/LAMA/ICS.

Bottom line

1. GOLD classification of COPD severity is now based on clinical criteria alone: symptom assessment and risk for exacerbation.

2. SABA/SAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to either SABA or SAMA alone.

3. Patients in group A (milder symptoms, low exacerbation risk) may be initiated on either short- or long-acting bronchodilator therapy.

4. Patients in group B (milder symptoms, increased exacerbation risk) should be initiated on LAMA monotherapy.

5. LABA/LAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to LABA/ICS combination therapy and should be used when long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy fails to control symptoms or reduce exacerbations.

References

1. CDC MMWR 11/23/12

2. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2017 at http://goldcopd.org (accessed 3/10/2017)

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Lent is chief resident in the program.

ADHD medication may lower risk of motor vehicle crashes

Men with ADHD had a 38% lower risk of motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) when receiving ADHD medication, compared with months off medication. Women had a 42% lower risk, according to the results of a U.S. study.

Estimates suggested that up to 22% of MVCs in patients with ADHD could have been avoided if they had received medication during the whole length of the study, reported Zheng Chang, PhD, of the Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, and his colleagues (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 May 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0659)

“This study is the first, to date, to demonstrate a long-term association between receiving ADHD medication and decreased MVCs,” said Dr. Chang and his associates. If this result demonstrates a protective effect, it is possible that continuous ADHD medication use might lead to lower risk of other problems, such as substance abuse disorder, or provide long-term improvements in life functioning for people with ADHD.

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council and the National Institute of Mental Health, as well as grants to two of the researchers from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Chang and the other researchers had no relevant financial disclosures, except for Henrik Larsson, PhD, who received some speaker’s fees and research grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this work.

Prescribing medication to ADHD patients does not guarantee they will take it. Therefore, there is a chance that some of the motor vehicle crashes that occurred during a month when a patient reportedly was on medication may have occurred on a day when the patient had not actually taken medication. Also, using ED visits to measure the number of MVCs has a major drawback: vehicular accidents do not necessarily result in ED visits. Therefore, the study by Chang et al. may not accurately report the benefits of ADHD medication on safe driving.

Management of ADHD is not limited to school or the workplace but extends to other aspects of life, such as driving, which clinicians must consider when prescribing. It also is important to keep in mind, while prescribing, that the progression of ADHD often involves a decrease in hyperactivity during adulthood, while inattention and impulsivity may continue, and that the latter two traits can lead to distracted driving. Another important variable is that MVCs involving individuals with ADHD often happen later in the evening, when their medications may have worn off.

Customizing and improving ADHD pharmacotherapy, while being mindful of effects, is the most sensible way forward.

Vishal Madaan, MD, and Daniel J. Cox, PhD, are at the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville. Dr. Madaan reported receiving research support from Forest, Purdue, Aevi Genomic Medicine (formerly Medgenics), Sunovion, and Pfizer, as well as receiving royalties from Taylor & Francis. Dr. Cox reported receiving research support from the National Institutes of Health, Purdue, Johnson & Johnson, and Dexcom. They made these remarks in a commentary accompanying the study by Dr. Chang et al. (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 May 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0659).

Prescribing medication to ADHD patients does not guarantee they will take it. Therefore, there is a chance that some of the motor vehicle crashes that occurred during a month when a patient reportedly was on medication may have occurred on a day when the patient had not actually taken medication. Also, using ED visits to measure the number of MVCs has a major drawback: vehicular accidents do not necessarily result in ED visits. Therefore, the study by Chang et al. may not accurately report the benefits of ADHD medication on safe driving.

Management of ADHD is not limited to school or the workplace but extends to other aspects of life, such as driving, which clinicians must consider when prescribing. It also is important to keep in mind, while prescribing, that the progression of ADHD often involves a decrease in hyperactivity during adulthood, while inattention and impulsivity may continue, and that the latter two traits can lead to distracted driving. Another important variable is that MVCs involving individuals with ADHD often happen later in the evening, when their medications may have worn off.

Customizing and improving ADHD pharmacotherapy, while being mindful of effects, is the most sensible way forward.

Vishal Madaan, MD, and Daniel J. Cox, PhD, are at the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville. Dr. Madaan reported receiving research support from Forest, Purdue, Aevi Genomic Medicine (formerly Medgenics), Sunovion, and Pfizer, as well as receiving royalties from Taylor & Francis. Dr. Cox reported receiving research support from the National Institutes of Health, Purdue, Johnson & Johnson, and Dexcom. They made these remarks in a commentary accompanying the study by Dr. Chang et al. (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 May 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0659).

Prescribing medication to ADHD patients does not guarantee they will take it. Therefore, there is a chance that some of the motor vehicle crashes that occurred during a month when a patient reportedly was on medication may have occurred on a day when the patient had not actually taken medication. Also, using ED visits to measure the number of MVCs has a major drawback: vehicular accidents do not necessarily result in ED visits. Therefore, the study by Chang et al. may not accurately report the benefits of ADHD medication on safe driving.

Management of ADHD is not limited to school or the workplace but extends to other aspects of life, such as driving, which clinicians must consider when prescribing. It also is important to keep in mind, while prescribing, that the progression of ADHD often involves a decrease in hyperactivity during adulthood, while inattention and impulsivity may continue, and that the latter two traits can lead to distracted driving. Another important variable is that MVCs involving individuals with ADHD often happen later in the evening, when their medications may have worn off.

Customizing and improving ADHD pharmacotherapy, while being mindful of effects, is the most sensible way forward.

Vishal Madaan, MD, and Daniel J. Cox, PhD, are at the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville. Dr. Madaan reported receiving research support from Forest, Purdue, Aevi Genomic Medicine (formerly Medgenics), Sunovion, and Pfizer, as well as receiving royalties from Taylor & Francis. Dr. Cox reported receiving research support from the National Institutes of Health, Purdue, Johnson & Johnson, and Dexcom. They made these remarks in a commentary accompanying the study by Dr. Chang et al. (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 May 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0659).

Men with ADHD had a 38% lower risk of motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) when receiving ADHD medication, compared with months off medication. Women had a 42% lower risk, according to the results of a U.S. study.

Estimates suggested that up to 22% of MVCs in patients with ADHD could have been avoided if they had received medication during the whole length of the study, reported Zheng Chang, PhD, of the Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, and his colleagues (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 May 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0659)

“This study is the first, to date, to demonstrate a long-term association between receiving ADHD medication and decreased MVCs,” said Dr. Chang and his associates. If this result demonstrates a protective effect, it is possible that continuous ADHD medication use might lead to lower risk of other problems, such as substance abuse disorder, or provide long-term improvements in life functioning for people with ADHD.

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council and the National Institute of Mental Health, as well as grants to two of the researchers from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Chang and the other researchers had no relevant financial disclosures, except for Henrik Larsson, PhD, who received some speaker’s fees and research grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this work.

Men with ADHD had a 38% lower risk of motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) when receiving ADHD medication, compared with months off medication. Women had a 42% lower risk, according to the results of a U.S. study.

Estimates suggested that up to 22% of MVCs in patients with ADHD could have been avoided if they had received medication during the whole length of the study, reported Zheng Chang, PhD, of the Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, and his colleagues (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 May 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0659)

“This study is the first, to date, to demonstrate a long-term association between receiving ADHD medication and decreased MVCs,” said Dr. Chang and his associates. If this result demonstrates a protective effect, it is possible that continuous ADHD medication use might lead to lower risk of other problems, such as substance abuse disorder, or provide long-term improvements in life functioning for people with ADHD.

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council and the National Institute of Mental Health, as well as grants to two of the researchers from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Chang and the other researchers had no relevant financial disclosures, except for Henrik Larsson, PhD, who received some speaker’s fees and research grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this work.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients with ADHD have 22% less risk for motor vehicle crashes when they are on medication.

Data source: Data were gathered from commercial insurance claims of a national cohort of 2,319,450 patients with ADHD and ED visits for motor vehicle crashes.

Disclosures: This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council and the National Institute of Mental Health, as well grants to two of the researchers from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Chang and the other researchers had no relevant financial disclosures, except for Dr. Larsson who received some speaker’s fees and research grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this work.

Myeloma patients who get solid tumor cancers do as well as other cancer patients

With improved treatment, patients with multiple myeloma are surviving long enough to develop other cancers, Jorge J. Castillo, MD, and Adam J. Olszewski, MD, reported in a poster to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The good news is that myeloma patients, when diagnosed with a subsequent solid tumor, are just as likely to respond to treatment and do just as well as patients without myeloma, according to Dr. Castillo of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and Dr. Olszewski of Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, R.I.

They based their conclusion on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for patients diagnosed with six common cancers from 2004-2013.

“Among them, we identified [nearly 1,300] myeloma survivors, and we matched each to 50 randomly sampled controls with the same cancer by age, sex, race, and year of diagnosis. We then compared [cancer specific survival], cumulative incidence function (CIF) for death from the non-myeloma index cancer, and whether patients had surgery for non-metastastic, stage-matched tumors only,” the researchers wrote in their abstract.

They did analyses for breast, lung, prostate, colorectal, melanoma, and bladder cancers. The median time from diagnosis of myeloma to diagnosis of the second ranged from 35 months (bladder [133 myeloma patients] and lung [286 myeloma patients] cancers) to 50 months (melanoma [140 myeloma patients]). The median time after myeloma diagnosis was 40 months for those patients who developed breast, prostate, or colorectal cancers.

In the comparisons, myeloma survivors were significantly older (P less than .001) than patients initially diagnosed with the same respective cancers. In the case-control analysis, breast (P = .002) and lung cancers (P = .003) were more often diagnosed at an early stage among myeloma survivors.

The hazard ratio (HR) for cancer-specific survival for 189 myeloma patients diagnosed with breast cancer as compared to other breast cancer patients, for example, was 0.99, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.61-1.61. The HR for the cumulative incidence function of cancer death was 0.82, 95% CI 0.50-1.35.

Myeloma patients were no less likely than were case-control subjects to have surgery for their cancers, with the exception of the 330 myeloma patients who developed prostate cancer (odds ratio, 0.59, 95% CI, 0.44-0.81).

Cancer-specific survival significantly differed (P less than .05) only for lung cancer, and was better among the 286 myeloma patients with lung cancer even when stratified by stage (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.54-0.75). For cumulative incidence function of cancer death for lung cancer, the hazard ratio was 0.52 (95% CI 0.44-0.61). Better outcomes in lung cancer are not fully explained by earlier detection, suggesting a biological difference, the researchers reported.

Cumulative incidence function of cancer death was significantly lower for myeloma patients with lung and colorectal cancers.

Dr. Castillo disclosed honoraria from Celgene and Janssen; a consulting or advisory role with Biogen, Otsuka, and Pharmacyclics; and institutional research funding from Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Millennium, and Pharmacyclics. Dr. Olszewski disclosed institutional research funding from Genentech, Incyte, and TG Therapeutics.

Citation: Outcomes of secondary cancers among myeloma survivors. 2017 ASCO annual meeting. Abstract No. 8043.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

With improved treatment, patients with multiple myeloma are surviving long enough to develop other cancers, Jorge J. Castillo, MD, and Adam J. Olszewski, MD, reported in a poster to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The good news is that myeloma patients, when diagnosed with a subsequent solid tumor, are just as likely to respond to treatment and do just as well as patients without myeloma, according to Dr. Castillo of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and Dr. Olszewski of Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, R.I.

They based their conclusion on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for patients diagnosed with six common cancers from 2004-2013.

“Among them, we identified [nearly 1,300] myeloma survivors, and we matched each to 50 randomly sampled controls with the same cancer by age, sex, race, and year of diagnosis. We then compared [cancer specific survival], cumulative incidence function (CIF) for death from the non-myeloma index cancer, and whether patients had surgery for non-metastastic, stage-matched tumors only,” the researchers wrote in their abstract.

They did analyses for breast, lung, prostate, colorectal, melanoma, and bladder cancers. The median time from diagnosis of myeloma to diagnosis of the second ranged from 35 months (bladder [133 myeloma patients] and lung [286 myeloma patients] cancers) to 50 months (melanoma [140 myeloma patients]). The median time after myeloma diagnosis was 40 months for those patients who developed breast, prostate, or colorectal cancers.

In the comparisons, myeloma survivors were significantly older (P less than .001) than patients initially diagnosed with the same respective cancers. In the case-control analysis, breast (P = .002) and lung cancers (P = .003) were more often diagnosed at an early stage among myeloma survivors.

The hazard ratio (HR) for cancer-specific survival for 189 myeloma patients diagnosed with breast cancer as compared to other breast cancer patients, for example, was 0.99, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.61-1.61. The HR for the cumulative incidence function of cancer death was 0.82, 95% CI 0.50-1.35.

Myeloma patients were no less likely than were case-control subjects to have surgery for their cancers, with the exception of the 330 myeloma patients who developed prostate cancer (odds ratio, 0.59, 95% CI, 0.44-0.81).

Cancer-specific survival significantly differed (P less than .05) only for lung cancer, and was better among the 286 myeloma patients with lung cancer even when stratified by stage (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.54-0.75). For cumulative incidence function of cancer death for lung cancer, the hazard ratio was 0.52 (95% CI 0.44-0.61). Better outcomes in lung cancer are not fully explained by earlier detection, suggesting a biological difference, the researchers reported.

Cumulative incidence function of cancer death was significantly lower for myeloma patients with lung and colorectal cancers.

Dr. Castillo disclosed honoraria from Celgene and Janssen; a consulting or advisory role with Biogen, Otsuka, and Pharmacyclics; and institutional research funding from Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Millennium, and Pharmacyclics. Dr. Olszewski disclosed institutional research funding from Genentech, Incyte, and TG Therapeutics.

Citation: Outcomes of secondary cancers among myeloma survivors. 2017 ASCO annual meeting. Abstract No. 8043.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

With improved treatment, patients with multiple myeloma are surviving long enough to develop other cancers, Jorge J. Castillo, MD, and Adam J. Olszewski, MD, reported in a poster to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The good news is that myeloma patients, when diagnosed with a subsequent solid tumor, are just as likely to respond to treatment and do just as well as patients without myeloma, according to Dr. Castillo of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and Dr. Olszewski of Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, R.I.

They based their conclusion on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for patients diagnosed with six common cancers from 2004-2013.

“Among them, we identified [nearly 1,300] myeloma survivors, and we matched each to 50 randomly sampled controls with the same cancer by age, sex, race, and year of diagnosis. We then compared [cancer specific survival], cumulative incidence function (CIF) for death from the non-myeloma index cancer, and whether patients had surgery for non-metastastic, stage-matched tumors only,” the researchers wrote in their abstract.

They did analyses for breast, lung, prostate, colorectal, melanoma, and bladder cancers. The median time from diagnosis of myeloma to diagnosis of the second ranged from 35 months (bladder [133 myeloma patients] and lung [286 myeloma patients] cancers) to 50 months (melanoma [140 myeloma patients]). The median time after myeloma diagnosis was 40 months for those patients who developed breast, prostate, or colorectal cancers.

In the comparisons, myeloma survivors were significantly older (P less than .001) than patients initially diagnosed with the same respective cancers. In the case-control analysis, breast (P = .002) and lung cancers (P = .003) were more often diagnosed at an early stage among myeloma survivors.

The hazard ratio (HR) for cancer-specific survival for 189 myeloma patients diagnosed with breast cancer as compared to other breast cancer patients, for example, was 0.99, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.61-1.61. The HR for the cumulative incidence function of cancer death was 0.82, 95% CI 0.50-1.35.

Myeloma patients were no less likely than were case-control subjects to have surgery for their cancers, with the exception of the 330 myeloma patients who developed prostate cancer (odds ratio, 0.59, 95% CI, 0.44-0.81).

Cancer-specific survival significantly differed (P less than .05) only for lung cancer, and was better among the 286 myeloma patients with lung cancer even when stratified by stage (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.54-0.75). For cumulative incidence function of cancer death for lung cancer, the hazard ratio was 0.52 (95% CI 0.44-0.61). Better outcomes in lung cancer are not fully explained by earlier detection, suggesting a biological difference, the researchers reported.

Cumulative incidence function of cancer death was significantly lower for myeloma patients with lung and colorectal cancers.

Dr. Castillo disclosed honoraria from Celgene and Janssen; a consulting or advisory role with Biogen, Otsuka, and Pharmacyclics; and institutional research funding from Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Millennium, and Pharmacyclics. Dr. Olszewski disclosed institutional research funding from Genentech, Incyte, and TG Therapeutics.

Citation: Outcomes of secondary cancers among myeloma survivors. 2017 ASCO annual meeting. Abstract No. 8043.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

FROM 2017 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Cancer-specific survival significantly differed (P less than .05) only for lung cancer, and was better among the 286 myeloma patients with lung cancer even when stratified by stage (HR, 0.64, 95% CI 0.54-0.75).

Data source: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for patients diagnosed with six common cancers from 2004-2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Castillo disclosed honoraria from Celgene and Janssen; a consulting or advisory role with Biogen, Otsuka, and Pharmacyclics; and institutional research funding from Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Millennium, and Pharmacyclics. Dr. Olszewski disclosed institutional research funding from Genentech, Incyte, and TG Therapeutics.

Citation: Outcomes of secondary cancers among myeloma survivors. 2017 ASCO annual meeting. Abstract No. 8043.

HM17 session summary: Focus on POCUS – Introduction to Point-of-Care Ultrasound for pediatric hospitalists

Presenters

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM; Thomas Conlon, MD; Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FHM; Daniel Schnobrich, MD

Summary

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly gaining acceptance in the medical community as a goal-directed examination that answers a specific diagnostic question or guides a bedside invasive procedure. Adoption by pediatric hospitalists is increasing, aided by multiple training pathways, opportunities for scholarship, and organization development.

The use of POCUS is increasing among nonradiologist physicians due to the expectation for perfection, desire for improved patient experience, and increased availability of ultrasound machines. POCUS is rapid and safe, and can be used serially to monitor, provide procedural guidance, and lead to initiation of appropriate therapies.

Training in POCUS in limited applications is possible in short periods of time. One recent study showed that approximately 40% of POCUS cases led to new findings or alteration of treatment. However, POCUS requires training, monitoring for competence, transparency of training/competence, and a QA process that supports the training. One solution at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia was to use American College of Emergency Physician guidelines for POCUS training.

Pediatric applications include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia and associated parapneumonic effusion, and IV placement. More advanced applications include diagnosis of appendicitis, intussusception, and increased intracranial pressure. Novel applications conceived by nonradiologist physicians have included sinus ultrasound.

Initial training can be provided by “in-house experts,” such as pediatric ED physicians and PICU physicians. Alternatively, an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups. Consideration should be given to mentorship, with comparison to formal imaging and/or clinical progression. Relationships with traditional imagers should be cultivated, as POCUS can potentially be misunderstood. In fact, formal US utilization has been found to increase once clinicals begin to use POCUS.

Key takeaways for HM

- Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly being adopted by pediatric hospitalists.

- Pediatric applications are still being developed, but include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia/associated effusions, and IV placement.

- Initial training can be provided by pediatric ED physicians/PICU physicians or an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups.

- Relationships with radiologists should be established at the outset to avoid misunderstanding of POCUS.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Presenters

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM; Thomas Conlon, MD; Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FHM; Daniel Schnobrich, MD

Summary

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly gaining acceptance in the medical community as a goal-directed examination that answers a specific diagnostic question or guides a bedside invasive procedure. Adoption by pediatric hospitalists is increasing, aided by multiple training pathways, opportunities for scholarship, and organization development.

The use of POCUS is increasing among nonradiologist physicians due to the expectation for perfection, desire for improved patient experience, and increased availability of ultrasound machines. POCUS is rapid and safe, and can be used serially to monitor, provide procedural guidance, and lead to initiation of appropriate therapies.

Training in POCUS in limited applications is possible in short periods of time. One recent study showed that approximately 40% of POCUS cases led to new findings or alteration of treatment. However, POCUS requires training, monitoring for competence, transparency of training/competence, and a QA process that supports the training. One solution at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia was to use American College of Emergency Physician guidelines for POCUS training.

Pediatric applications include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia and associated parapneumonic effusion, and IV placement. More advanced applications include diagnosis of appendicitis, intussusception, and increased intracranial pressure. Novel applications conceived by nonradiologist physicians have included sinus ultrasound.

Initial training can be provided by “in-house experts,” such as pediatric ED physicians and PICU physicians. Alternatively, an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups. Consideration should be given to mentorship, with comparison to formal imaging and/or clinical progression. Relationships with traditional imagers should be cultivated, as POCUS can potentially be misunderstood. In fact, formal US utilization has been found to increase once clinicals begin to use POCUS.

Key takeaways for HM

- Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly being adopted by pediatric hospitalists.

- Pediatric applications are still being developed, but include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia/associated effusions, and IV placement.

- Initial training can be provided by pediatric ED physicians/PICU physicians or an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups.

- Relationships with radiologists should be established at the outset to avoid misunderstanding of POCUS.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Presenters

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM; Thomas Conlon, MD; Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FHM; Daniel Schnobrich, MD

Summary

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly gaining acceptance in the medical community as a goal-directed examination that answers a specific diagnostic question or guides a bedside invasive procedure. Adoption by pediatric hospitalists is increasing, aided by multiple training pathways, opportunities for scholarship, and organization development.

The use of POCUS is increasing among nonradiologist physicians due to the expectation for perfection, desire for improved patient experience, and increased availability of ultrasound machines. POCUS is rapid and safe, and can be used serially to monitor, provide procedural guidance, and lead to initiation of appropriate therapies.

Training in POCUS in limited applications is possible in short periods of time. One recent study showed that approximately 40% of POCUS cases led to new findings or alteration of treatment. However, POCUS requires training, monitoring for competence, transparency of training/competence, and a QA process that supports the training. One solution at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia was to use American College of Emergency Physician guidelines for POCUS training.

Pediatric applications include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia and associated parapneumonic effusion, and IV placement. More advanced applications include diagnosis of appendicitis, intussusception, and increased intracranial pressure. Novel applications conceived by nonradiologist physicians have included sinus ultrasound.

Initial training can be provided by “in-house experts,” such as pediatric ED physicians and PICU physicians. Alternatively, an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups. Consideration should be given to mentorship, with comparison to formal imaging and/or clinical progression. Relationships with traditional imagers should be cultivated, as POCUS can potentially be misunderstood. In fact, formal US utilization has been found to increase once clinicals begin to use POCUS.

Key takeaways for HM

- Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly being adopted by pediatric hospitalists.

- Pediatric applications are still being developed, but include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia/associated effusions, and IV placement.

- Initial training can be provided by pediatric ED physicians/PICU physicians or an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups.

- Relationships with radiologists should be established at the outset to avoid misunderstanding of POCUS.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Omitting ALND in some breast cancer patients may be the right choice

PHILADELPHIA – The safety of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) alone without axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) has been established for patients with cT1-2N0 cancer that are found to have one or two metastatic sentinel lymph nodes who undergo breast conservation therapy, but questions regarding the role of regional radiation have persisted.

This issue is addressed by the results of a large, prospective, 5+ year study at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center which confirmed the safety of omitting axillary lymph node dissection and suggested that regional radiation provides minimal benefit.

Dr. Morrow explained that, in August 2010, the breast surgery service at MSKCC adopted the guidelines that arose from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group’s multicenter Z0011 trial and abandoned routine use of ALND in eligible patients. The goal of the study, she reported, was to determine how frequently axillary dissection was avoided in a consecutive, otherwise unselected, series of patients and to determine the incidence of local regional recurrence after SLNB alone in a population treated with known radiotherapy fields.

Eligible subjects had T1 or T2 node-negative breast cancer, were undergoing breast-conserving surgery with planned whole-breast irradiation, and were found to have hematoxylin-eosin-detected sentinel node metastases. Patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or requiring conversion to mastectomy, or those in whom partial breast irradiation or no radiotherapy was planned, were ineligible. Axillary imaging was not used in select patients. Criteria for axillary dissection were metastases in three or more sentinel nodes or the presence of matted nodes identified intraoperatively. The researchers did not use the MSKCC nomogram to predict the likelihood of non–sentinel node metastases.

Median patient age was 58 years and median tumor size 1.7 cm. With regard to tumor pathology, 87% had infiltrating ductal tumors, 94% had grade 2 or 3 disease, and the most common subtype was HR+, HER2– disease in 84%. “In this node-positive cohort of patients, 98% received adjuvant systemic therapy, most commonly both chemotherapy and endocrine therapy (received by 65%), and 93% completed radiotherapy,” Dr. Morrow said.

In the entire patient cohort, 84% (663) were treated with SLNB alone, Dr. Morrow said. Among the 130 patients requiring ALND, 68% (88) had metastases in three or more nodes, 26% (34) were found to have had matted nodes intraoperatively, and 6% (8) were eligible for SLNB alone but opted for ALND or had it recommended by their surgeon. “All of these occurred early in our experience, and this has not been repeated since,” Dr. Morrow said.

Among the SLNB-only patients, the 5-year event-free survival was 93%. “There were no isolated axillary recurrences,” Dr. Morrow said. The study reported four combined breast and axillary recurrences, three in nonradiated patients, and four combined nodal and distant recurrences, only one of which involved the axillary nodes. “The median time to any nodal recurrence was 25 months,” Dr. Morrow added. Among 484 patients who had 1 year or more of follow-up, 58% (280) received conventional supine breast tangents, 21% were treated prone – “meaning their axilla received essentially no radiotherapy,” Dr. Morrow said – and 21% had node field irradiation.

“If we compare patient characteristics based on radiotherapy fields treated, it’s clear that the patients who received nodal irradiation were a higher-risk group,” Dr. Morrow said. While all three groups had a median of one positive sentinel node, that “skewed towards two” in the nodal irradiation group, she said. This group also had higher rates of lymphovascular invasion (72% vs. 56% and 49% in the supine and prone groups, respectively) and extracapsular extension (41% vs. 31% and 25%).

The rates of nodal relapse were not statistically significant among the three groups: 1% in the prone group, 1.4% in the supine group, and 0% in the node irradiation group.

“Factors associated with a higher risk of distant metastases, such as young patient age, estrogen receptor negativity, or HER2 over-expression, were not associated with the need for axillary dissection and should not be used as priority selection criteria,” Dr. Morrow said. “Nodal recurrence was uncommon in the absence of routine nodal radiation therapy, and no isolated nodal failures were observed.

In his comments, Armando Giuliano, MD, of Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, principal investigator of the Z0011 trial, said the MSKCC study “extends and informs” the Z0011 findings. He noted that the prone treatment group in the MSKCC trial had a low rate of axillary recurrence. “Can you speculate how such excellent results are achieved without resection or irradiation?” he asked Dr. Morrow. “To me it appears that nodal irradiation provides very little benefit to this selected group of patients.”

The patients in the prone group were in the lowest-risk category of the study, Dr. Morrow said, but the fact that not all nodal disease becomes clinically evident, even in patients who do not receive radiotherapy or systemic therapy, along with the high use of systemic therapy in this group, may explain the low rates of axillary recurrence. “What I think we still need to find out, though, is whether or not failure to irradiate the nodes at all is in any way associated with decreased survival, as would be suggested in the MA.20 trial,” she said. “I think we will find that out from ongoing trials looking at no axillary dissection in mastectomy patients.”

Dr. Morrow and Dr. Giuliano reported no financial disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 137th Annual Meeting, April 2017, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is to be published in Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

PHILADELPHIA – The safety of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) alone without axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) has been established for patients with cT1-2N0 cancer that are found to have one or two metastatic sentinel lymph nodes who undergo breast conservation therapy, but questions regarding the role of regional radiation have persisted.

This issue is addressed by the results of a large, prospective, 5+ year study at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center which confirmed the safety of omitting axillary lymph node dissection and suggested that regional radiation provides minimal benefit.

Dr. Morrow explained that, in August 2010, the breast surgery service at MSKCC adopted the guidelines that arose from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group’s multicenter Z0011 trial and abandoned routine use of ALND in eligible patients. The goal of the study, she reported, was to determine how frequently axillary dissection was avoided in a consecutive, otherwise unselected, series of patients and to determine the incidence of local regional recurrence after SLNB alone in a population treated with known radiotherapy fields.

Eligible subjects had T1 or T2 node-negative breast cancer, were undergoing breast-conserving surgery with planned whole-breast irradiation, and were found to have hematoxylin-eosin-detected sentinel node metastases. Patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or requiring conversion to mastectomy, or those in whom partial breast irradiation or no radiotherapy was planned, were ineligible. Axillary imaging was not used in select patients. Criteria for axillary dissection were metastases in three or more sentinel nodes or the presence of matted nodes identified intraoperatively. The researchers did not use the MSKCC nomogram to predict the likelihood of non–sentinel node metastases.

Median patient age was 58 years and median tumor size 1.7 cm. With regard to tumor pathology, 87% had infiltrating ductal tumors, 94% had grade 2 or 3 disease, and the most common subtype was HR+, HER2– disease in 84%. “In this node-positive cohort of patients, 98% received adjuvant systemic therapy, most commonly both chemotherapy and endocrine therapy (received by 65%), and 93% completed radiotherapy,” Dr. Morrow said.

In the entire patient cohort, 84% (663) were treated with SLNB alone, Dr. Morrow said. Among the 130 patients requiring ALND, 68% (88) had metastases in three or more nodes, 26% (34) were found to have had matted nodes intraoperatively, and 6% (8) were eligible for SLNB alone but opted for ALND or had it recommended by their surgeon. “All of these occurred early in our experience, and this has not been repeated since,” Dr. Morrow said.

Among the SLNB-only patients, the 5-year event-free survival was 93%. “There were no isolated axillary recurrences,” Dr. Morrow said. The study reported four combined breast and axillary recurrences, three in nonradiated patients, and four combined nodal and distant recurrences, only one of which involved the axillary nodes. “The median time to any nodal recurrence was 25 months,” Dr. Morrow added. Among 484 patients who had 1 year or more of follow-up, 58% (280) received conventional supine breast tangents, 21% were treated prone – “meaning their axilla received essentially no radiotherapy,” Dr. Morrow said – and 21% had node field irradiation.

“If we compare patient characteristics based on radiotherapy fields treated, it’s clear that the patients who received nodal irradiation were a higher-risk group,” Dr. Morrow said. While all three groups had a median of one positive sentinel node, that “skewed towards two” in the nodal irradiation group, she said. This group also had higher rates of lymphovascular invasion (72% vs. 56% and 49% in the supine and prone groups, respectively) and extracapsular extension (41% vs. 31% and 25%).

The rates of nodal relapse were not statistically significant among the three groups: 1% in the prone group, 1.4% in the supine group, and 0% in the node irradiation group.

“Factors associated with a higher risk of distant metastases, such as young patient age, estrogen receptor negativity, or HER2 over-expression, were not associated with the need for axillary dissection and should not be used as priority selection criteria,” Dr. Morrow said. “Nodal recurrence was uncommon in the absence of routine nodal radiation therapy, and no isolated nodal failures were observed.

In his comments, Armando Giuliano, MD, of Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, principal investigator of the Z0011 trial, said the MSKCC study “extends and informs” the Z0011 findings. He noted that the prone treatment group in the MSKCC trial had a low rate of axillary recurrence. “Can you speculate how such excellent results are achieved without resection or irradiation?” he asked Dr. Morrow. “To me it appears that nodal irradiation provides very little benefit to this selected group of patients.”

The patients in the prone group were in the lowest-risk category of the study, Dr. Morrow said, but the fact that not all nodal disease becomes clinically evident, even in patients who do not receive radiotherapy or systemic therapy, along with the high use of systemic therapy in this group, may explain the low rates of axillary recurrence. “What I think we still need to find out, though, is whether or not failure to irradiate the nodes at all is in any way associated with decreased survival, as would be suggested in the MA.20 trial,” she said. “I think we will find that out from ongoing trials looking at no axillary dissection in mastectomy patients.”

Dr. Morrow and Dr. Giuliano reported no financial disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 137th Annual Meeting, April 2017, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is to be published in Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

PHILADELPHIA – The safety of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) alone without axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) has been established for patients with cT1-2N0 cancer that are found to have one or two metastatic sentinel lymph nodes who undergo breast conservation therapy, but questions regarding the role of regional radiation have persisted.

This issue is addressed by the results of a large, prospective, 5+ year study at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center which confirmed the safety of omitting axillary lymph node dissection and suggested that regional radiation provides minimal benefit.

Dr. Morrow explained that, in August 2010, the breast surgery service at MSKCC adopted the guidelines that arose from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group’s multicenter Z0011 trial and abandoned routine use of ALND in eligible patients. The goal of the study, she reported, was to determine how frequently axillary dissection was avoided in a consecutive, otherwise unselected, series of patients and to determine the incidence of local regional recurrence after SLNB alone in a population treated with known radiotherapy fields.

Eligible subjects had T1 or T2 node-negative breast cancer, were undergoing breast-conserving surgery with planned whole-breast irradiation, and were found to have hematoxylin-eosin-detected sentinel node metastases. Patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or requiring conversion to mastectomy, or those in whom partial breast irradiation or no radiotherapy was planned, were ineligible. Axillary imaging was not used in select patients. Criteria for axillary dissection were metastases in three or more sentinel nodes or the presence of matted nodes identified intraoperatively. The researchers did not use the MSKCC nomogram to predict the likelihood of non–sentinel node metastases.