User login

Healthy lifestyle, tree nuts may protect against colon cancer recurrence

Oncologists whose patients with treated early colon cancer ask what they can do to prevent it from coming back can now more strongly endorse lifestyle modification, based on findings from a pair of cohort studies reported at a presscast leading up to the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Both studies were conducted among more than 800 patients with stage III colon cancer participating in a nationwide randomized adjuvant chemotherapy trial who completed comprehensive lifestyle questionnaires.

Data for the studies were collected prospectively, noted ASCO President Daniel F. Hayes, MD. “So, that takes a lot of the biases out of the classic retrospective observational studies where patients are asked, ‘Do you remember what you did several years ago?’ Most of us would not. In this case, it was in real time, so it makes these findings even more compelling, in my opinion.

“We can now present optimism to patients with early-stage colon cancer,” Dr. Hayes added. “The odds of surviving colon cancer if it is not metastatic are quite high these days, thanks to lots of hard work and a number of trials done over the last 30 years showing that adequate surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy improve survival.”

Therefore, patients today have even more reason to make a commitment to a healthy lifestyle, which may further improve their outcomes, in addition to its other benefits, he commented.

At the same time, the studies’ findings should not be used to justify skipping good standard of care treatment for early colon cancer, stressed Dr. Hayes, who is also clinical director of the breast oncology program and Stuart B. Padnos Professor in breast cancer research at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“Nobody wants to undergo chemotherapy. We understand that,” Dr. Hayes said. “But chemotherapy clearly saves lives, so people should not interpret these two abstracts as suggesting that, if you live a healthy lifestyle and if you eat tree nuts, you don’t need to take the chemotherapy that your oncologist would recommend. That’s a very dangerous interpretation, and it’s not what we’re trying to get across. It’s that healthy people live healthier.”

In the first study, Erin Van Blarigan, ScD, assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues assessed adherence to the American Cancer Society’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines for Cancer Survivors among 992 patients with stage III colon cancer who enrolled in the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 89803 adjuvant chemotherapy trial within 8 weeks of cancer resection.

“The guidelines are based on published scientific studies, but it’s not actually known if patients who follow the guidelines after diagnosis live longer,” she explained in the presscast.

All patients completed a validated lifestyle questionnaire during and 6 months after completing chemotherapy. Responses were used to assign patients points reflecting guideline adherence on body weight; regular physical activity; a dietary pattern high in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, and low in red meat and processed meat; and alcohol intake (not specifically included in the guidelines but described in the text).

When lifestyle scores were calculated without consideration of alcohol intake, 26% of patients had a score of 0-1, corresponding to the least healthy lifestyle, while 9% had a score of 5-6, corresponding to the most healthy lifestyle, Dr. Van Blarigan reported.

Risks of both disease-free and overall survival events fell significantly with increasing score (P = .01). Compared with peers who scored 0-1, patients who scored 5-6 had a 42% lower risk of death.

When lifestyle scores were calculated with consideration of alcohol intake, 19% of patients had a score of 0-2, while 16% had a score of 6-8.

Here, too, risks of both disease-free and overall survival events fell significantly with increasing score (P = .002). Compared with peers who scored 0-2, patients who scored 6-8 had a 51% lower risk of death.

“Colon cancer patients who had a healthy body weight, engaged in regular physical activity of approximately 1 hour 5 days a week, and ate a diet rich in a variety of vegetables and fruit – choosing whole grains over refined ones, avoiding red and processed meats, and drinking small to moderate amounts of alcohol – had longer disease-free and overall survival, compared with patients who did not engage in these behaviors,” summarized Dr. Van Blarigan.

The mechanism by which low to moderate alcohol intake, compared with none, may be protective is unclear, but the pattern is consistent with that seen for other diseases, she said.

“There has been some literature in cardiovascular disease about changes in insulin and inflammation and elasticity of blood vessels and things like that,” Dr. Van Blarigan noted. “So, I think that’s something to explore further for colon cancer.”

In the second study, Temidayo Fadelu, MD, a clinical fellow in medicine at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues assessed nut intake among 826 patients enrolled in the same trial. They used questionnaires completed 6 months after the end of chemotherapy, which asked about consumption of tree nuts, peanuts, and peanut butter.

“States of energy excess are associated with an increased risk of colon cancer death and recurrence … and one mechanism is thought to maybe be hyperinsulinemia,” he commented in the presscast. Research has found nut consumption to be associated with lower incidences of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance.

Study results showed that the adjusted risks of both disease-free survival and overall survival events fell with increasing frequency of total nut consumption. Patients eating nuts at least twice weekly (19% of the cohort) had a 42% lower adjusted risk of disease-free survival events and a 57% lower adjusted risk of death, relative to counterparts who never ate nuts.

“We don’t really know what the underlying biologic mechanism is for this association, but we hypothesize that it’s perhaps due to the influence of nuts on insulin resistance,” Dr. Fadelu said, noting that they contain fatty acids, fiber, and flavonoids and that insulin levels rise to a lesser degree after eating nuts than after eating foods such as simple sugars. “There need to be further studies to really evaluate this hypothesis,” he added.

“We did a secondary analysis, and we observed that the association described was limited to tree nuts; the association was not seen with peanuts or peanut butter intake,” noted Dr. Fadelu, who reported that he had no disclosures. “Peanuts are technically legumes, and this difference may perhaps be due to the different biochemical composition between peanuts and tree nuts.”

Dr. Van Blarigan reported that she had no disclosures. Dr. Fadelu reported that he had no disclosures.

Oncologists whose patients with treated early colon cancer ask what they can do to prevent it from coming back can now more strongly endorse lifestyle modification, based on findings from a pair of cohort studies reported at a presscast leading up to the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Both studies were conducted among more than 800 patients with stage III colon cancer participating in a nationwide randomized adjuvant chemotherapy trial who completed comprehensive lifestyle questionnaires.

Data for the studies were collected prospectively, noted ASCO President Daniel F. Hayes, MD. “So, that takes a lot of the biases out of the classic retrospective observational studies where patients are asked, ‘Do you remember what you did several years ago?’ Most of us would not. In this case, it was in real time, so it makes these findings even more compelling, in my opinion.

“We can now present optimism to patients with early-stage colon cancer,” Dr. Hayes added. “The odds of surviving colon cancer if it is not metastatic are quite high these days, thanks to lots of hard work and a number of trials done over the last 30 years showing that adequate surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy improve survival.”

Therefore, patients today have even more reason to make a commitment to a healthy lifestyle, which may further improve their outcomes, in addition to its other benefits, he commented.

At the same time, the studies’ findings should not be used to justify skipping good standard of care treatment for early colon cancer, stressed Dr. Hayes, who is also clinical director of the breast oncology program and Stuart B. Padnos Professor in breast cancer research at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“Nobody wants to undergo chemotherapy. We understand that,” Dr. Hayes said. “But chemotherapy clearly saves lives, so people should not interpret these two abstracts as suggesting that, if you live a healthy lifestyle and if you eat tree nuts, you don’t need to take the chemotherapy that your oncologist would recommend. That’s a very dangerous interpretation, and it’s not what we’re trying to get across. It’s that healthy people live healthier.”

In the first study, Erin Van Blarigan, ScD, assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues assessed adherence to the American Cancer Society’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines for Cancer Survivors among 992 patients with stage III colon cancer who enrolled in the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 89803 adjuvant chemotherapy trial within 8 weeks of cancer resection.

“The guidelines are based on published scientific studies, but it’s not actually known if patients who follow the guidelines after diagnosis live longer,” she explained in the presscast.

All patients completed a validated lifestyle questionnaire during and 6 months after completing chemotherapy. Responses were used to assign patients points reflecting guideline adherence on body weight; regular physical activity; a dietary pattern high in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, and low in red meat and processed meat; and alcohol intake (not specifically included in the guidelines but described in the text).

When lifestyle scores were calculated without consideration of alcohol intake, 26% of patients had a score of 0-1, corresponding to the least healthy lifestyle, while 9% had a score of 5-6, corresponding to the most healthy lifestyle, Dr. Van Blarigan reported.

Risks of both disease-free and overall survival events fell significantly with increasing score (P = .01). Compared with peers who scored 0-1, patients who scored 5-6 had a 42% lower risk of death.

When lifestyle scores were calculated with consideration of alcohol intake, 19% of patients had a score of 0-2, while 16% had a score of 6-8.

Here, too, risks of both disease-free and overall survival events fell significantly with increasing score (P = .002). Compared with peers who scored 0-2, patients who scored 6-8 had a 51% lower risk of death.

“Colon cancer patients who had a healthy body weight, engaged in regular physical activity of approximately 1 hour 5 days a week, and ate a diet rich in a variety of vegetables and fruit – choosing whole grains over refined ones, avoiding red and processed meats, and drinking small to moderate amounts of alcohol – had longer disease-free and overall survival, compared with patients who did not engage in these behaviors,” summarized Dr. Van Blarigan.

The mechanism by which low to moderate alcohol intake, compared with none, may be protective is unclear, but the pattern is consistent with that seen for other diseases, she said.

“There has been some literature in cardiovascular disease about changes in insulin and inflammation and elasticity of blood vessels and things like that,” Dr. Van Blarigan noted. “So, I think that’s something to explore further for colon cancer.”

In the second study, Temidayo Fadelu, MD, a clinical fellow in medicine at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues assessed nut intake among 826 patients enrolled in the same trial. They used questionnaires completed 6 months after the end of chemotherapy, which asked about consumption of tree nuts, peanuts, and peanut butter.

“States of energy excess are associated with an increased risk of colon cancer death and recurrence … and one mechanism is thought to maybe be hyperinsulinemia,” he commented in the presscast. Research has found nut consumption to be associated with lower incidences of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance.

Study results showed that the adjusted risks of both disease-free survival and overall survival events fell with increasing frequency of total nut consumption. Patients eating nuts at least twice weekly (19% of the cohort) had a 42% lower adjusted risk of disease-free survival events and a 57% lower adjusted risk of death, relative to counterparts who never ate nuts.

“We don’t really know what the underlying biologic mechanism is for this association, but we hypothesize that it’s perhaps due to the influence of nuts on insulin resistance,” Dr. Fadelu said, noting that they contain fatty acids, fiber, and flavonoids and that insulin levels rise to a lesser degree after eating nuts than after eating foods such as simple sugars. “There need to be further studies to really evaluate this hypothesis,” he added.

“We did a secondary analysis, and we observed that the association described was limited to tree nuts; the association was not seen with peanuts or peanut butter intake,” noted Dr. Fadelu, who reported that he had no disclosures. “Peanuts are technically legumes, and this difference may perhaps be due to the different biochemical composition between peanuts and tree nuts.”

Dr. Van Blarigan reported that she had no disclosures. Dr. Fadelu reported that he had no disclosures.

Oncologists whose patients with treated early colon cancer ask what they can do to prevent it from coming back can now more strongly endorse lifestyle modification, based on findings from a pair of cohort studies reported at a presscast leading up to the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Both studies were conducted among more than 800 patients with stage III colon cancer participating in a nationwide randomized adjuvant chemotherapy trial who completed comprehensive lifestyle questionnaires.

Data for the studies were collected prospectively, noted ASCO President Daniel F. Hayes, MD. “So, that takes a lot of the biases out of the classic retrospective observational studies where patients are asked, ‘Do you remember what you did several years ago?’ Most of us would not. In this case, it was in real time, so it makes these findings even more compelling, in my opinion.

“We can now present optimism to patients with early-stage colon cancer,” Dr. Hayes added. “The odds of surviving colon cancer if it is not metastatic are quite high these days, thanks to lots of hard work and a number of trials done over the last 30 years showing that adequate surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy improve survival.”

Therefore, patients today have even more reason to make a commitment to a healthy lifestyle, which may further improve their outcomes, in addition to its other benefits, he commented.

At the same time, the studies’ findings should not be used to justify skipping good standard of care treatment for early colon cancer, stressed Dr. Hayes, who is also clinical director of the breast oncology program and Stuart B. Padnos Professor in breast cancer research at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“Nobody wants to undergo chemotherapy. We understand that,” Dr. Hayes said. “But chemotherapy clearly saves lives, so people should not interpret these two abstracts as suggesting that, if you live a healthy lifestyle and if you eat tree nuts, you don’t need to take the chemotherapy that your oncologist would recommend. That’s a very dangerous interpretation, and it’s not what we’re trying to get across. It’s that healthy people live healthier.”

In the first study, Erin Van Blarigan, ScD, assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues assessed adherence to the American Cancer Society’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines for Cancer Survivors among 992 patients with stage III colon cancer who enrolled in the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 89803 adjuvant chemotherapy trial within 8 weeks of cancer resection.

“The guidelines are based on published scientific studies, but it’s not actually known if patients who follow the guidelines after diagnosis live longer,” she explained in the presscast.

All patients completed a validated lifestyle questionnaire during and 6 months after completing chemotherapy. Responses were used to assign patients points reflecting guideline adherence on body weight; regular physical activity; a dietary pattern high in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, and low in red meat and processed meat; and alcohol intake (not specifically included in the guidelines but described in the text).

When lifestyle scores were calculated without consideration of alcohol intake, 26% of patients had a score of 0-1, corresponding to the least healthy lifestyle, while 9% had a score of 5-6, corresponding to the most healthy lifestyle, Dr. Van Blarigan reported.

Risks of both disease-free and overall survival events fell significantly with increasing score (P = .01). Compared with peers who scored 0-1, patients who scored 5-6 had a 42% lower risk of death.

When lifestyle scores were calculated with consideration of alcohol intake, 19% of patients had a score of 0-2, while 16% had a score of 6-8.

Here, too, risks of both disease-free and overall survival events fell significantly with increasing score (P = .002). Compared with peers who scored 0-2, patients who scored 6-8 had a 51% lower risk of death.

“Colon cancer patients who had a healthy body weight, engaged in regular physical activity of approximately 1 hour 5 days a week, and ate a diet rich in a variety of vegetables and fruit – choosing whole grains over refined ones, avoiding red and processed meats, and drinking small to moderate amounts of alcohol – had longer disease-free and overall survival, compared with patients who did not engage in these behaviors,” summarized Dr. Van Blarigan.

The mechanism by which low to moderate alcohol intake, compared with none, may be protective is unclear, but the pattern is consistent with that seen for other diseases, she said.

“There has been some literature in cardiovascular disease about changes in insulin and inflammation and elasticity of blood vessels and things like that,” Dr. Van Blarigan noted. “So, I think that’s something to explore further for colon cancer.”

In the second study, Temidayo Fadelu, MD, a clinical fellow in medicine at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues assessed nut intake among 826 patients enrolled in the same trial. They used questionnaires completed 6 months after the end of chemotherapy, which asked about consumption of tree nuts, peanuts, and peanut butter.

“States of energy excess are associated with an increased risk of colon cancer death and recurrence … and one mechanism is thought to maybe be hyperinsulinemia,” he commented in the presscast. Research has found nut consumption to be associated with lower incidences of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance.

Study results showed that the adjusted risks of both disease-free survival and overall survival events fell with increasing frequency of total nut consumption. Patients eating nuts at least twice weekly (19% of the cohort) had a 42% lower adjusted risk of disease-free survival events and a 57% lower adjusted risk of death, relative to counterparts who never ate nuts.

“We don’t really know what the underlying biologic mechanism is for this association, but we hypothesize that it’s perhaps due to the influence of nuts on insulin resistance,” Dr. Fadelu said, noting that they contain fatty acids, fiber, and flavonoids and that insulin levels rise to a lesser degree after eating nuts than after eating foods such as simple sugars. “There need to be further studies to really evaluate this hypothesis,” he added.

“We did a secondary analysis, and we observed that the association described was limited to tree nuts; the association was not seen with peanuts or peanut butter intake,” noted Dr. Fadelu, who reported that he had no disclosures. “Peanuts are technically legumes, and this difference may perhaps be due to the different biochemical composition between peanuts and tree nuts.”

Dr. Van Blarigan reported that she had no disclosures. Dr. Fadelu reported that he had no disclosures.

FROM THE 2017 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Compared with counterparts who have the least healthy lifestyle, patients with the healthiest lifestyle were 42%-51% less likely to die. Relative to peers who never ate nuts, patients who ate nuts at least twice a week had a 42% lower risk of disease-free survival events and a 57% lower risk of death.

Data source: A pair of prospective cohort studies among 992 patients and 826 patients with resected stage III colon cancer given adjuvant chemotherapy in a clinical trial (CALGB 89803).

Disclosures: Dr. Van Blarigan reported that she had no disclosures. Dr. Fadelu reported that he had no disclosures.

Adolescents and sleep, or the lack thereof

Every parent will attest that bright-eyed children grow into sleepy adolescents, and the science confirms their observations. There are multiple factors that prevent adolescents from getting the sleep they need, and inadequate sleep has serious consequences – from impaired learning to depressive symptoms, obesity to deadly accidents – all of which are potentially preventable with some practical strategies to promote adequate sleep.

Adolescence is a period of intense growth and development, so it is no surprise that adolescents require a lot of sleep, over 9 hours nightly. But surveys have shown that only 3% of American adolescents get 9 hours of sleep nightly, and the average amount of weeknight sleep is only 6 hours.1 Sleep deprivation is not a problem in childhood, so why can’t adolescents get enough sleep?

Over the last 15 years, a new factor – screen time – has worsened the adolescent sleep situation. Most teens have an electronic device in their bedroom and use it for homework, entertainment, and socializing well into the night. Multiple studies have confirmed that electronic exposure in the evening is associated with less sleep at night and more day time sleepiness,by competing with sleep and suppression of nocturnal melatonin release, which can delay the onset of sleep.2

It is ironic that many teens are staying up late for homework, when their lack of sleep can interfere with consolidation of learning. It also has powerful effects on working memory and reaction time, making both academic and athletic performance suffer. Chronically sleep-deprived teenagers often complain of difficulty with initiating and sustaining attention, which may lead to a mistaken diagnosis of ADHD, and stimulant treatment may further complicate sleep.

Good mental health is not the only casualty of inadequate sleep. A growing body of evidence links short sleep duration with an increased risk of obesity. This appears to be mediated by alterations in neurohormones associated with sleep, leading to higher carbohydrate and fat intake, more snacking and insulin resistance.

Anything that compromises attention and reaction time, including sleep deprivation, adds risk to driving, particularly for inexperienced and impulsive adolescent drivers. The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration estimates that drivers 25 and younger cause more than half of all “fall asleep” crashes.

Teenagers generally know that they are exhausted, but the strategies they might use to manage their fatigue can actually make things worse. Sleepy teenagers often consume large amounts of caffeine to get through their days and their homework at night. Caffeine, in turn, interferes with both the onset and quality of sleep, perpetuating the cycle. Even “catch-up” sleep on weekends is a strategy that can contribute to the problem, as it can lead to more disrupted sleep by pushing the onset of school night sleepiness even later.

While growing autonomy is part of why teenagers are sleep deprived, they will consider the caring and informed guidance of their pediatricians about their health. Ask your teenage patients how much sleep they usually get on a school night. It can be validating to show them how sleep deprived they are, and point out how strategies like caffeine and oversleeping might be making it worse. Explain that people (adults, too!) need to make time for sleep just as they might for exercise or friends. Tell them about “good sleep hygiene,” the practice of having consistent sleep times and routines that are conducive to restful sleep. This can include a hot shower before bed, reading for the last 30 minutes before lights out, and no screen time for at least 1 hour before bed. Indeed, it can be powerful to urge that everyone in the family takes screens out of their bedrooms.

Additionally, while they might sleep in on weekends, it shouldn’t be much more than an hour longer than on weekdays. And no naps after school! It is common for teens to feel overwhelmed by their commitments and that sleep must be the first thing to go. Use their growing sense of autonomy to remind them that they get to choose how to use their time, and balance will pay off much more than sacrificing sleep. A practical conversation about sleep can help them to make informed choices and thoughtfully take care of themselves before they head off to college.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Resources

1. “Adolescent Sleep Needs and Patterns: Research Report and Resource Guide.” (Arlington, Va.: National Sleep Foundation, 2000.)

2. Pediatrics. 2014 Sep;134(3):e921-32.

3. Sleep. 2004 Nov 1;27(7):1351-8.

Every parent will attest that bright-eyed children grow into sleepy adolescents, and the science confirms their observations. There are multiple factors that prevent adolescents from getting the sleep they need, and inadequate sleep has serious consequences – from impaired learning to depressive symptoms, obesity to deadly accidents – all of which are potentially preventable with some practical strategies to promote adequate sleep.

Adolescence is a period of intense growth and development, so it is no surprise that adolescents require a lot of sleep, over 9 hours nightly. But surveys have shown that only 3% of American adolescents get 9 hours of sleep nightly, and the average amount of weeknight sleep is only 6 hours.1 Sleep deprivation is not a problem in childhood, so why can’t adolescents get enough sleep?

Over the last 15 years, a new factor – screen time – has worsened the adolescent sleep situation. Most teens have an electronic device in their bedroom and use it for homework, entertainment, and socializing well into the night. Multiple studies have confirmed that electronic exposure in the evening is associated with less sleep at night and more day time sleepiness,by competing with sleep and suppression of nocturnal melatonin release, which can delay the onset of sleep.2

It is ironic that many teens are staying up late for homework, when their lack of sleep can interfere with consolidation of learning. It also has powerful effects on working memory and reaction time, making both academic and athletic performance suffer. Chronically sleep-deprived teenagers often complain of difficulty with initiating and sustaining attention, which may lead to a mistaken diagnosis of ADHD, and stimulant treatment may further complicate sleep.

Good mental health is not the only casualty of inadequate sleep. A growing body of evidence links short sleep duration with an increased risk of obesity. This appears to be mediated by alterations in neurohormones associated with sleep, leading to higher carbohydrate and fat intake, more snacking and insulin resistance.

Anything that compromises attention and reaction time, including sleep deprivation, adds risk to driving, particularly for inexperienced and impulsive adolescent drivers. The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration estimates that drivers 25 and younger cause more than half of all “fall asleep” crashes.

Teenagers generally know that they are exhausted, but the strategies they might use to manage their fatigue can actually make things worse. Sleepy teenagers often consume large amounts of caffeine to get through their days and their homework at night. Caffeine, in turn, interferes with both the onset and quality of sleep, perpetuating the cycle. Even “catch-up” sleep on weekends is a strategy that can contribute to the problem, as it can lead to more disrupted sleep by pushing the onset of school night sleepiness even later.

While growing autonomy is part of why teenagers are sleep deprived, they will consider the caring and informed guidance of their pediatricians about their health. Ask your teenage patients how much sleep they usually get on a school night. It can be validating to show them how sleep deprived they are, and point out how strategies like caffeine and oversleeping might be making it worse. Explain that people (adults, too!) need to make time for sleep just as they might for exercise or friends. Tell them about “good sleep hygiene,” the practice of having consistent sleep times and routines that are conducive to restful sleep. This can include a hot shower before bed, reading for the last 30 minutes before lights out, and no screen time for at least 1 hour before bed. Indeed, it can be powerful to urge that everyone in the family takes screens out of their bedrooms.

Additionally, while they might sleep in on weekends, it shouldn’t be much more than an hour longer than on weekdays. And no naps after school! It is common for teens to feel overwhelmed by their commitments and that sleep must be the first thing to go. Use their growing sense of autonomy to remind them that they get to choose how to use their time, and balance will pay off much more than sacrificing sleep. A practical conversation about sleep can help them to make informed choices and thoughtfully take care of themselves before they head off to college.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Resources

1. “Adolescent Sleep Needs and Patterns: Research Report and Resource Guide.” (Arlington, Va.: National Sleep Foundation, 2000.)

2. Pediatrics. 2014 Sep;134(3):e921-32.

3. Sleep. 2004 Nov 1;27(7):1351-8.

Every parent will attest that bright-eyed children grow into sleepy adolescents, and the science confirms their observations. There are multiple factors that prevent adolescents from getting the sleep they need, and inadequate sleep has serious consequences – from impaired learning to depressive symptoms, obesity to deadly accidents – all of which are potentially preventable with some practical strategies to promote adequate sleep.

Adolescence is a period of intense growth and development, so it is no surprise that adolescents require a lot of sleep, over 9 hours nightly. But surveys have shown that only 3% of American adolescents get 9 hours of sleep nightly, and the average amount of weeknight sleep is only 6 hours.1 Sleep deprivation is not a problem in childhood, so why can’t adolescents get enough sleep?

Over the last 15 years, a new factor – screen time – has worsened the adolescent sleep situation. Most teens have an electronic device in their bedroom and use it for homework, entertainment, and socializing well into the night. Multiple studies have confirmed that electronic exposure in the evening is associated with less sleep at night and more day time sleepiness,by competing with sleep and suppression of nocturnal melatonin release, which can delay the onset of sleep.2

It is ironic that many teens are staying up late for homework, when their lack of sleep can interfere with consolidation of learning. It also has powerful effects on working memory and reaction time, making both academic and athletic performance suffer. Chronically sleep-deprived teenagers often complain of difficulty with initiating and sustaining attention, which may lead to a mistaken diagnosis of ADHD, and stimulant treatment may further complicate sleep.

Good mental health is not the only casualty of inadequate sleep. A growing body of evidence links short sleep duration with an increased risk of obesity. This appears to be mediated by alterations in neurohormones associated with sleep, leading to higher carbohydrate and fat intake, more snacking and insulin resistance.

Anything that compromises attention and reaction time, including sleep deprivation, adds risk to driving, particularly for inexperienced and impulsive adolescent drivers. The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration estimates that drivers 25 and younger cause more than half of all “fall asleep” crashes.

Teenagers generally know that they are exhausted, but the strategies they might use to manage their fatigue can actually make things worse. Sleepy teenagers often consume large amounts of caffeine to get through their days and their homework at night. Caffeine, in turn, interferes with both the onset and quality of sleep, perpetuating the cycle. Even “catch-up” sleep on weekends is a strategy that can contribute to the problem, as it can lead to more disrupted sleep by pushing the onset of school night sleepiness even later.

While growing autonomy is part of why teenagers are sleep deprived, they will consider the caring and informed guidance of their pediatricians about their health. Ask your teenage patients how much sleep they usually get on a school night. It can be validating to show them how sleep deprived they are, and point out how strategies like caffeine and oversleeping might be making it worse. Explain that people (adults, too!) need to make time for sleep just as they might for exercise or friends. Tell them about “good sleep hygiene,” the practice of having consistent sleep times and routines that are conducive to restful sleep. This can include a hot shower before bed, reading for the last 30 minutes before lights out, and no screen time for at least 1 hour before bed. Indeed, it can be powerful to urge that everyone in the family takes screens out of their bedrooms.

Additionally, while they might sleep in on weekends, it shouldn’t be much more than an hour longer than on weekdays. And no naps after school! It is common for teens to feel overwhelmed by their commitments and that sleep must be the first thing to go. Use their growing sense of autonomy to remind them that they get to choose how to use their time, and balance will pay off much more than sacrificing sleep. A practical conversation about sleep can help them to make informed choices and thoughtfully take care of themselves before they head off to college.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Resources

1. “Adolescent Sleep Needs and Patterns: Research Report and Resource Guide.” (Arlington, Va.: National Sleep Foundation, 2000.)

2. Pediatrics. 2014 Sep;134(3):e921-32.

3. Sleep. 2004 Nov 1;27(7):1351-8.

Highlights From the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology

Selected highlights from the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology

Selected highlights from the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology

Selected highlights from the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology

Systems modeling advances precision medicine in alopecia

PORTLAND – Alopecia areata can resist treatment stubbornly, but dermatologists might soon have better tools to predict response to therapy.

Personalized gene sequencing is key to this type of precision medicine, but conventional sequencing can be “extremely cumbersome and clinically impractical,” James C. Chen, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

During alopecia trials at Columbia, researchers routinely perform RNA sequencing of scalp biopsies to analyze therapeutic response on a molecular level. Using these RNAseq data from patients with untreated alopecia areata and gene regulatory network analysis data from the Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks, Dr. Chen and his associates modeled the molecular mechanisms of action of the pan–Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib, the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, the CTLA4 inhibitor abatacept, and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (IL-TAC). Heat maps of molecular responses to treatment showed distinct mechanisms of action between IL-TAC and abatacept, Dr. Chen said.

Furthermore, these therapies showed distinct and much less robust molecular effects than either ruxolitinib or tofacitinib. A Venn diagram of the biosignatures and molecular mechanisms of action of all four therapies showed little overlap. In fact, the probability of so little overlap between tofacitinib and IL-TAC occurring by chance was 0.023. The lack of overlap between the two JAK inhibitors was even more pronounced (P = 2.21 x 10–11).

Only 5-10 transcription factors are needed to capture these molecular mechanisms of action, which could greatly streamline precision dermatology in the future, according to Dr. Chen. “Systems biology offers a foundation for developing precision medicine strategies and selecting treatments for patients based on their individual molecular pathology,” he concluded. “Even when patients with alopecia areata have the same clinical phenotype, the molecular pathways they take to get there are not necessarily the same. We need to define those paths to maximize our chances of matching drugs to patients.”

Dr. Chen acknowledged support from the National Institutes of Health, epiCURE, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. He had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND – Alopecia areata can resist treatment stubbornly, but dermatologists might soon have better tools to predict response to therapy.

Personalized gene sequencing is key to this type of precision medicine, but conventional sequencing can be “extremely cumbersome and clinically impractical,” James C. Chen, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

During alopecia trials at Columbia, researchers routinely perform RNA sequencing of scalp biopsies to analyze therapeutic response on a molecular level. Using these RNAseq data from patients with untreated alopecia areata and gene regulatory network analysis data from the Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks, Dr. Chen and his associates modeled the molecular mechanisms of action of the pan–Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib, the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, the CTLA4 inhibitor abatacept, and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (IL-TAC). Heat maps of molecular responses to treatment showed distinct mechanisms of action between IL-TAC and abatacept, Dr. Chen said.

Furthermore, these therapies showed distinct and much less robust molecular effects than either ruxolitinib or tofacitinib. A Venn diagram of the biosignatures and molecular mechanisms of action of all four therapies showed little overlap. In fact, the probability of so little overlap between tofacitinib and IL-TAC occurring by chance was 0.023. The lack of overlap between the two JAK inhibitors was even more pronounced (P = 2.21 x 10–11).

Only 5-10 transcription factors are needed to capture these molecular mechanisms of action, which could greatly streamline precision dermatology in the future, according to Dr. Chen. “Systems biology offers a foundation for developing precision medicine strategies and selecting treatments for patients based on their individual molecular pathology,” he concluded. “Even when patients with alopecia areata have the same clinical phenotype, the molecular pathways they take to get there are not necessarily the same. We need to define those paths to maximize our chances of matching drugs to patients.”

Dr. Chen acknowledged support from the National Institutes of Health, epiCURE, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. He had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND – Alopecia areata can resist treatment stubbornly, but dermatologists might soon have better tools to predict response to therapy.

Personalized gene sequencing is key to this type of precision medicine, but conventional sequencing can be “extremely cumbersome and clinically impractical,” James C. Chen, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

During alopecia trials at Columbia, researchers routinely perform RNA sequencing of scalp biopsies to analyze therapeutic response on a molecular level. Using these RNAseq data from patients with untreated alopecia areata and gene regulatory network analysis data from the Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks, Dr. Chen and his associates modeled the molecular mechanisms of action of the pan–Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib, the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, the CTLA4 inhibitor abatacept, and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (IL-TAC). Heat maps of molecular responses to treatment showed distinct mechanisms of action between IL-TAC and abatacept, Dr. Chen said.

Furthermore, these therapies showed distinct and much less robust molecular effects than either ruxolitinib or tofacitinib. A Venn diagram of the biosignatures and molecular mechanisms of action of all four therapies showed little overlap. In fact, the probability of so little overlap between tofacitinib and IL-TAC occurring by chance was 0.023. The lack of overlap between the two JAK inhibitors was even more pronounced (P = 2.21 x 10–11).

Only 5-10 transcription factors are needed to capture these molecular mechanisms of action, which could greatly streamline precision dermatology in the future, according to Dr. Chen. “Systems biology offers a foundation for developing precision medicine strategies and selecting treatments for patients based on their individual molecular pathology,” he concluded. “Even when patients with alopecia areata have the same clinical phenotype, the molecular pathways they take to get there are not necessarily the same. We need to define those paths to maximize our chances of matching drugs to patients.”

Dr. Chen acknowledged support from the National Institutes of Health, epiCURE, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. He had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SID 2017

Readability of Orthopedic Trauma Patient Education Materials on the Internet

Take-Home Points

- The Flesch-Kincaid Readability Scale is a useful tool in evaluating the readability of PEMs.

- Only 1 article analyzed in our study was below a sixth-grade readability level.

- Coauthorship of PEMs with other subspecialty groups had no effect on readability.

- Poor health literacy has been associated with poor health outcomes.

- Efforts must be undertaken to make PEMs more readable across medical subspecialties.

Patients increasingly turn to the Internet to self-educate about orthopedic conditions.1,2 Accordingly, the Internet has become a valuable tool in maintaining effective physician-patient communication.3-5 Given the Internet’s importance as a medium for conveying patient information, it is important that orthopedic patient education materials (PEMs) on the Internet provide high-quality information that is easily read by the target patient population. Unfortunately, studies have found that many of the Internet’s orthopedic PEMs have been neither of high quality6-8 nor presented such that they are easy for patients to read and comprehend.1,9-12

Readability, which is the reading comprehension level (school grade level) a person must have to understand written materials, is determined by systematic formulae12; readability levels correlate with the ability to comprehend written information.2 Studies have consistently found that orthopedic PEMs are written at readability levels too high for the average patient to understand.1,9,13 The readability of PEMs in orthopedics as a whole9 and within the orthopedic subspecialties of arthroplasty,1 foot and ankle surgery,2 sports medicine,12 and spine surgery13 has been evaluated, but so far there has been no evaluation of PEMs in orthopedic trauma (OT).

We conducted a study to assess the readability of OT-PEMs available online from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) in conjunction with the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) and other orthopedic subspecialty societies. We hypothesized the readability levels of these OT-PEMs would be above the level (sixth to eighth grade) recommended by several healthcare organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.9,11,14 We also assessed the effect that orthopedic subspecialty coauthorship has on PEM readability.

Methods

In July 2014, we searched the AAOS online patient education library (Broken Bones & Injuries section, http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/menus/injury.cfm) and the AAOS OrthoPortal website (Trauma section, http://pubsearch.aaos.org/search?q=trauma&client=OrthoInfo&site=PATIENT&output=xml_no_dtd&proxystylesheet=OrthoInfo&filter=0) for all relevant OT-PEMs. Although OTA does not publish its own PEMs on its website, it coauthored several of the articles in the AAOS patient education library. Other subspecialty organizations, including the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM), the American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH), the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA), the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES), the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (AAHKS), and the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS), coauthored several of these online OT-PEMs as well.

Using the technique described by Badarudeen and Sabharwal,10 we saved all articles to be included in the study as separate Microsoft Word 2011 files. We saved them in plain-text format to remove any HTML tags and any other hidden formatting that might affect readability results. Then we edited them to remove elements that might affect readability result accuracy—deleted article topic–unrelated information (eg, copyright notice, disclaimers, author information) and all numerals, decimal points, bullets, abbreviations, paragraph breaks, colons, semicolons, and dashes.10Mr. Mohan used the Flesch-Kincaid (FK) Readability Scale to calculate grade level for each article. Microsoft Word 2011 was used as described in other investigations of orthopedic PEM readability2,10,12,13: Its readability function is enabled by going to the Tools tab and then to the Spelling & Grammar tool, where the “Show readability statistics” option is selected.10 Readability scores are calculated with the Spelling & Grammar tool; the readability score is displayed after completion of the spelling-and-grammar check. The formula used to calculate FK grade level is15: (0.39 × average number of words per sentence) + (11.8 × average number of syllables per word) – 15.59.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated for the FK grade levels. Student t tests were used to compare average FK grade levels of articles written exclusively by AAOS with those of articles coauthored by AAOS and other orthopedic subspecialty societies. A 2-sample unequal-variance t test was used, and significance was set at P < .05. Total number of articles written at or below the sixth- and eighth-grade levels, the reading levels recommended for PEMs, were tabulated.1,9-12 Intraobserver and interobserver reliabilities were calculated with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs): Mr. Mohan, who calculated the FK scores earlier, now 1 week later calculated the readability levels of 15 randomly selected articles10,11; in addition, Mr. Mohan and Dr. Yi independently calculated the readability levels of 30 randomly selected articles.10,11 The same method described earlier—edit plain-text files, then use Microsoft Word to obtain FK scores—was again used. ICCs of 0 to 0.24 correspond to poor correlation; 0.25 to 0.49, low correlation; 0.5 to 0.69, fair correlation; 0.7 to 0.89, good correlation; and 0.9 to 1.0, excellent correlation.10,11 All statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel 2011 and VassarStats (http://vassarstats.net/tu.html).

Results

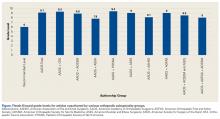

Of the 115 AAOS website articles included in the study and reviewed, 18 were coauthored by OTA, 10 by AOSSM, 14 by POSNA, 2 by ASSH, 2 by ASES, 1 by AAHKS, 3 by AOFAS, 1 by AOSSM and ASES, and 1 by AOFAS and AOSSM.

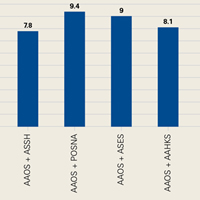

Mean FK grade level was 9.1 (range, 6.2-12; 95% CI, 8.9-9.3) for all articles reviewed and 9.1 (range, 6.2-12; 95% CI, 8.8-9.4) for articles exclusively written by AAOS. For coauthored articles, mean FK grade level was 9.3 (range, 7.6-11.3; 95% CI, 8.8-9.8) for AAOS-OTA; 8.9 (range, 7.4-10.4; 95% CI, 8.4-9.6) for AAOS-AOSSM; 9.4 (range, 7-11.8; 95% CI, 8.9-10.1) for AAOS-POSNA; 7.8 (range, 7.8-9.1; 95% CI, 7.2-9.8) for AAOS-ASSH; 9 (range, 8.2-9.6; 95% CI, 7.6-10.2) for AAOS-ASES; 9 (range, 7.9-9; 95% CI, 7.9-9.3) for AAOS-AOFAS; 8.1 for the 1 AAOS-AAHKS article; 8.5 for the 1 AAOS-AOSSM-ASES article; and 8 for the 1 AAOS-AOFAS-AOSSM article (Figure).

For FK readability calculations, interobserver reliability (ICC, 0.9982) and intraobserver reliability (ICC, 1) were both excellent.

Discussion

Although increasing numbers of patients are using information from the Internet to inform their healthcare decisions,12 studies have shown that online PEMs are written at a readability level above that of the average patient.1,9,13 In the present study, we also found that OT-PEMs from AAOS are written at a level considerably higher than the recommended sixth-grade reading level,16 potentially impairing patient comprehension and leading to poorer health outcomes.17

The pervasiveness of too-high PEM readability levels has been found across orthopedic subspecialties.2,9,12,13 Following this trend, the OT articles we reviewed had a ninth-grade reading level on average, and only 1 of 115 articles was below the recommended sixth-grade level.10 The issue of too-high PEM readability levels is thus a problem both in OT and in orthopedics in general. Accordingly, efforts to address this problem are warranted, especially as orthopedic PEM readability has not substantially improved over the past several years.18In this study, we also tried to identify any readability differences between articles coauthored by orthopedic societies and articles that were not coauthored by orthopedic societies. We hypothesized that multidisciplinary authorship could improve PEM readability; for example, orthopedic societies could collaborate with other medical specialties (eg, family medicine) that have produced appropriately readable PEMs. One study found that the majority of PEMs from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) were written below the sixth-grade reading level because of strict organizational regulation of the production of such materials.19 By noting and adopting successful PEM development methods used by groups such as AAFP,19,20 we might be able to improve OT-PEM readability. However, this was not the case in our study, though our observations may have been limited by the small sample of reviewable articles.

One factor contributing to the poor readability of orthopedic PEMs is that orthopedics terminology is complex and includes words that are often difficult to translate into simpler terms without losing their meaning.10 When PEMs are written at a level that is too complex, patients cannot fully comprehend them, which may lead to poor health literacy. This problem may be even more harmful when considering the poor literacy levels of patients at baseline. Kadakia and colleagues16 found that OT patients had poor health literacy; for example, fewer than half knew which bone they fractured. As health literacy is associated with poorer health outcomes and reduced use of healthcare services,21 optimizing patients’ health literacy is of crucial importance to both their education and their outcomes.

Our study should be viewed in light of some important limitations. As OTA does not publish its own PEMs, we assessed only OT-related articles that were available on the AAOS website and were exclusively written by AAOS, or coauthored by AAOS and by OTA and/or another orthopedic subspecialty organization. As these articles represent only a subset of the full spectrum of OT-PEMs available on the Internet, our results may not be generalizable to the entire scope of such materials. However, as AAOS and OTA represent the most authoritative OT organizations, we think these PEMs would be among those most likely to be recommended to patients by their surgeons. In addition, although we used a well-established tool for examining readability—the FK readability scale10-13—this tool has its own inherent limitations, as FK readability grade level is calculated purely on the basis of words per sentence and total syllables per word, and does not take into account other article elements, such as images, which also provide information.1,10 Nevertheless, the FK scale is an inexpensive, easily accessed readability tool that provides a reproducible readability value that is easily comparable to results from earlier studies.10 The final limitation is that we excluded from the study AAOS website articles written in a language other than English. Such articles, however, are important, as a large portion of the patient population speaks English as a second language. Indeed, the readability of Spanish PEMs has been investigated—albeit using a readability measure other than the FK scale—and may be a topic pertinent to orthopedic PEMs.22Most of the literature on the readability of orthopedic PEMs has found their reading levels too high for the average patient to comprehend.1,9-12 The trend continues with our study findings regarding OT-PEMs available online from AAOS. Although the literature on the inadequacies of orthopedic PEMs is vast,1,9-12 more work is needed to improve the quality, accuracy, and readability of these materials. There has been some success in improving PEM readability and producing appropriately readable materials within the medical profession,19,23 so we know that appropriately readable orthopedic PEMs are feasible.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):E190-E194. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Polishchuk DL, Hashem J, Sabharwal S. Readability of online patient education materials on adult reconstruction web sites. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):716-719.

2. Bluman EM, Foley RP, Chiodo CP. Readability of the patient education section of the AOFAS website. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(4):287-291.

3. Hoffmann T, Russell T. Pre-admission orthopaedic occupational therapy home visits conducted using the Internet. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14(2):83-87.

4. Rider T, Malik M, Chevassut T. Haematology patients and the Internet—the use of on-line health information and the impact on the patient–doctor relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(2):223-238.

5. AlGhamdi KM, Moussa NA. Internet use by the public to search for health-related information. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(6):363-373.

6. Beredjiklian PK, Bozentka DJ, Steinberg DR, Bernstein J. Evaluating the source and content of orthopaedic information on the Internet. The case of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(11):1540-1543.

7. Meena S, Palaniswamy A, Chowdhury B. Web-based information on minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2013;21(3):305-307.

8. Labovitch RS, Bozic KJ, Hansen E. An evaluation of information available on the Internet regarding minimally invasive hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(1):1-5.

9. Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Assessing readability of patient education materials: current role in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(10):2572-2580.

10. Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Readability of patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America web sites. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):199-204.

11. Yi PH, Ganta A, Hussein KI, Frank RM, Jawa A. Readability of arthroscopy-related patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Arthroscopy Association of North America web sites. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(6):1108-1112.

12. Ganta A, Yi PH, Hussein K, Frank RM. Readability of sports medicine–related patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine. Am J Orthop. 2014;43(4):E65-E68.

13. Vives M, Young L, Sabharwal S. Readability of spine-related patient education materials from subspecialty organization and spine practitioner websites. Spine. 2009;34(25):2826-2831.

14. Strategic and Proactive Communication Branch, Division of Communication Services, Office of the Associate Director for Communication, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. Simply Put: A Guide for Creating Easy-to-Understand Materials. 3rd ed. http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/pdf/Simply_Put.pdf. Published July 2010. Accessed February 7, 2015.

15. Wallace LS, Keenum AJ, DeVoe JE. Evaluation of consumer medical information and oral liquid measuring devices accompanying pediatric prescriptions. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(4):224-227.

16. Kadakia RJ, Tsahakis JM, Issar NM, et al. Health literacy in an orthopedic trauma patient population: a cross-sectional survey of patient comprehension. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(8):467-471.

17. Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, et al. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1695-1701.

18. Feghhi DP, Agarwal N, Hansberry DR, Berberian WS, Sabharwal S. Critical review of patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Am J Orthop. 2014;43(8):E168-E174.

19. Schoof ML, Wallace LS. Readability of American Academy of Family Physicians patient education materials. Fam Med. 2014;46(4):291-293.

20. Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients With Low Literacy Skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1996.

21. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97-107.

22. Berland GK, Elliott MN, Morales LS, et al. Health information on the Internet: accessibility, quality, and readability in English and Spanish. JAMA. 2001;285(20):2612-2621.

23. Sheppard ED, Hyde Z, Florence MN, McGwin G, Kirchner JS, Ponce BA. Improving the readability of online foot and ankle patient education materials. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(12):1282-1286.

Take-Home Points

- The Flesch-Kincaid Readability Scale is a useful tool in evaluating the readability of PEMs.

- Only 1 article analyzed in our study was below a sixth-grade readability level.

- Coauthorship of PEMs with other subspecialty groups had no effect on readability.

- Poor health literacy has been associated with poor health outcomes.

- Efforts must be undertaken to make PEMs more readable across medical subspecialties.

Patients increasingly turn to the Internet to self-educate about orthopedic conditions.1,2 Accordingly, the Internet has become a valuable tool in maintaining effective physician-patient communication.3-5 Given the Internet’s importance as a medium for conveying patient information, it is important that orthopedic patient education materials (PEMs) on the Internet provide high-quality information that is easily read by the target patient population. Unfortunately, studies have found that many of the Internet’s orthopedic PEMs have been neither of high quality6-8 nor presented such that they are easy for patients to read and comprehend.1,9-12

Readability, which is the reading comprehension level (school grade level) a person must have to understand written materials, is determined by systematic formulae12; readability levels correlate with the ability to comprehend written information.2 Studies have consistently found that orthopedic PEMs are written at readability levels too high for the average patient to understand.1,9,13 The readability of PEMs in orthopedics as a whole9 and within the orthopedic subspecialties of arthroplasty,1 foot and ankle surgery,2 sports medicine,12 and spine surgery13 has been evaluated, but so far there has been no evaluation of PEMs in orthopedic trauma (OT).

We conducted a study to assess the readability of OT-PEMs available online from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) in conjunction with the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) and other orthopedic subspecialty societies. We hypothesized the readability levels of these OT-PEMs would be above the level (sixth to eighth grade) recommended by several healthcare organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.9,11,14 We also assessed the effect that orthopedic subspecialty coauthorship has on PEM readability.

Methods

In July 2014, we searched the AAOS online patient education library (Broken Bones & Injuries section, http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/menus/injury.cfm) and the AAOS OrthoPortal website (Trauma section, http://pubsearch.aaos.org/search?q=trauma&client=OrthoInfo&site=PATIENT&output=xml_no_dtd&proxystylesheet=OrthoInfo&filter=0) for all relevant OT-PEMs. Although OTA does not publish its own PEMs on its website, it coauthored several of the articles in the AAOS patient education library. Other subspecialty organizations, including the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM), the American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH), the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA), the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES), the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (AAHKS), and the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS), coauthored several of these online OT-PEMs as well.

Using the technique described by Badarudeen and Sabharwal,10 we saved all articles to be included in the study as separate Microsoft Word 2011 files. We saved them in plain-text format to remove any HTML tags and any other hidden formatting that might affect readability results. Then we edited them to remove elements that might affect readability result accuracy—deleted article topic–unrelated information (eg, copyright notice, disclaimers, author information) and all numerals, decimal points, bullets, abbreviations, paragraph breaks, colons, semicolons, and dashes.10Mr. Mohan used the Flesch-Kincaid (FK) Readability Scale to calculate grade level for each article. Microsoft Word 2011 was used as described in other investigations of orthopedic PEM readability2,10,12,13: Its readability function is enabled by going to the Tools tab and then to the Spelling & Grammar tool, where the “Show readability statistics” option is selected.10 Readability scores are calculated with the Spelling & Grammar tool; the readability score is displayed after completion of the spelling-and-grammar check. The formula used to calculate FK grade level is15: (0.39 × average number of words per sentence) + (11.8 × average number of syllables per word) – 15.59.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated for the FK grade levels. Student t tests were used to compare average FK grade levels of articles written exclusively by AAOS with those of articles coauthored by AAOS and other orthopedic subspecialty societies. A 2-sample unequal-variance t test was used, and significance was set at P < .05. Total number of articles written at or below the sixth- and eighth-grade levels, the reading levels recommended for PEMs, were tabulated.1,9-12 Intraobserver and interobserver reliabilities were calculated with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs): Mr. Mohan, who calculated the FK scores earlier, now 1 week later calculated the readability levels of 15 randomly selected articles10,11; in addition, Mr. Mohan and Dr. Yi independently calculated the readability levels of 30 randomly selected articles.10,11 The same method described earlier—edit plain-text files, then use Microsoft Word to obtain FK scores—was again used. ICCs of 0 to 0.24 correspond to poor correlation; 0.25 to 0.49, low correlation; 0.5 to 0.69, fair correlation; 0.7 to 0.89, good correlation; and 0.9 to 1.0, excellent correlation.10,11 All statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel 2011 and VassarStats (http://vassarstats.net/tu.html).

Results

Of the 115 AAOS website articles included in the study and reviewed, 18 were coauthored by OTA, 10 by AOSSM, 14 by POSNA, 2 by ASSH, 2 by ASES, 1 by AAHKS, 3 by AOFAS, 1 by AOSSM and ASES, and 1 by AOFAS and AOSSM.

Mean FK grade level was 9.1 (range, 6.2-12; 95% CI, 8.9-9.3) for all articles reviewed and 9.1 (range, 6.2-12; 95% CI, 8.8-9.4) for articles exclusively written by AAOS. For coauthored articles, mean FK grade level was 9.3 (range, 7.6-11.3; 95% CI, 8.8-9.8) for AAOS-OTA; 8.9 (range, 7.4-10.4; 95% CI, 8.4-9.6) for AAOS-AOSSM; 9.4 (range, 7-11.8; 95% CI, 8.9-10.1) for AAOS-POSNA; 7.8 (range, 7.8-9.1; 95% CI, 7.2-9.8) for AAOS-ASSH; 9 (range, 8.2-9.6; 95% CI, 7.6-10.2) for AAOS-ASES; 9 (range, 7.9-9; 95% CI, 7.9-9.3) for AAOS-AOFAS; 8.1 for the 1 AAOS-AAHKS article; 8.5 for the 1 AAOS-AOSSM-ASES article; and 8 for the 1 AAOS-AOFAS-AOSSM article (Figure).

For FK readability calculations, interobserver reliability (ICC, 0.9982) and intraobserver reliability (ICC, 1) were both excellent.

Discussion

Although increasing numbers of patients are using information from the Internet to inform their healthcare decisions,12 studies have shown that online PEMs are written at a readability level above that of the average patient.1,9,13 In the present study, we also found that OT-PEMs from AAOS are written at a level considerably higher than the recommended sixth-grade reading level,16 potentially impairing patient comprehension and leading to poorer health outcomes.17

The pervasiveness of too-high PEM readability levels has been found across orthopedic subspecialties.2,9,12,13 Following this trend, the OT articles we reviewed had a ninth-grade reading level on average, and only 1 of 115 articles was below the recommended sixth-grade level.10 The issue of too-high PEM readability levels is thus a problem both in OT and in orthopedics in general. Accordingly, efforts to address this problem are warranted, especially as orthopedic PEM readability has not substantially improved over the past several years.18In this study, we also tried to identify any readability differences between articles coauthored by orthopedic societies and articles that were not coauthored by orthopedic societies. We hypothesized that multidisciplinary authorship could improve PEM readability; for example, orthopedic societies could collaborate with other medical specialties (eg, family medicine) that have produced appropriately readable PEMs. One study found that the majority of PEMs from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) were written below the sixth-grade reading level because of strict organizational regulation of the production of such materials.19 By noting and adopting successful PEM development methods used by groups such as AAFP,19,20 we might be able to improve OT-PEM readability. However, this was not the case in our study, though our observations may have been limited by the small sample of reviewable articles.

One factor contributing to the poor readability of orthopedic PEMs is that orthopedics terminology is complex and includes words that are often difficult to translate into simpler terms without losing their meaning.10 When PEMs are written at a level that is too complex, patients cannot fully comprehend them, which may lead to poor health literacy. This problem may be even more harmful when considering the poor literacy levels of patients at baseline. Kadakia and colleagues16 found that OT patients had poor health literacy; for example, fewer than half knew which bone they fractured. As health literacy is associated with poorer health outcomes and reduced use of healthcare services,21 optimizing patients’ health literacy is of crucial importance to both their education and their outcomes.

Our study should be viewed in light of some important limitations. As OTA does not publish its own PEMs, we assessed only OT-related articles that were available on the AAOS website and were exclusively written by AAOS, or coauthored by AAOS and by OTA and/or another orthopedic subspecialty organization. As these articles represent only a subset of the full spectrum of OT-PEMs available on the Internet, our results may not be generalizable to the entire scope of such materials. However, as AAOS and OTA represent the most authoritative OT organizations, we think these PEMs would be among those most likely to be recommended to patients by their surgeons. In addition, although we used a well-established tool for examining readability—the FK readability scale10-13—this tool has its own inherent limitations, as FK readability grade level is calculated purely on the basis of words per sentence and total syllables per word, and does not take into account other article elements, such as images, which also provide information.1,10 Nevertheless, the FK scale is an inexpensive, easily accessed readability tool that provides a reproducible readability value that is easily comparable to results from earlier studies.10 The final limitation is that we excluded from the study AAOS website articles written in a language other than English. Such articles, however, are important, as a large portion of the patient population speaks English as a second language. Indeed, the readability of Spanish PEMs has been investigated—albeit using a readability measure other than the FK scale—and may be a topic pertinent to orthopedic PEMs.22Most of the literature on the readability of orthopedic PEMs has found their reading levels too high for the average patient to comprehend.1,9-12 The trend continues with our study findings regarding OT-PEMs available online from AAOS. Although the literature on the inadequacies of orthopedic PEMs is vast,1,9-12 more work is needed to improve the quality, accuracy, and readability of these materials. There has been some success in improving PEM readability and producing appropriately readable materials within the medical profession,19,23 so we know that appropriately readable orthopedic PEMs are feasible.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):E190-E194. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- The Flesch-Kincaid Readability Scale is a useful tool in evaluating the readability of PEMs.

- Only 1 article analyzed in our study was below a sixth-grade readability level.

- Coauthorship of PEMs with other subspecialty groups had no effect on readability.

- Poor health literacy has been associated with poor health outcomes.

- Efforts must be undertaken to make PEMs more readable across medical subspecialties.

Patients increasingly turn to the Internet to self-educate about orthopedic conditions.1,2 Accordingly, the Internet has become a valuable tool in maintaining effective physician-patient communication.3-5 Given the Internet’s importance as a medium for conveying patient information, it is important that orthopedic patient education materials (PEMs) on the Internet provide high-quality information that is easily read by the target patient population. Unfortunately, studies have found that many of the Internet’s orthopedic PEMs have been neither of high quality6-8 nor presented such that they are easy for patients to read and comprehend.1,9-12

Readability, which is the reading comprehension level (school grade level) a person must have to understand written materials, is determined by systematic formulae12; readability levels correlate with the ability to comprehend written information.2 Studies have consistently found that orthopedic PEMs are written at readability levels too high for the average patient to understand.1,9,13 The readability of PEMs in orthopedics as a whole9 and within the orthopedic subspecialties of arthroplasty,1 foot and ankle surgery,2 sports medicine,12 and spine surgery13 has been evaluated, but so far there has been no evaluation of PEMs in orthopedic trauma (OT).

We conducted a study to assess the readability of OT-PEMs available online from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) in conjunction with the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) and other orthopedic subspecialty societies. We hypothesized the readability levels of these OT-PEMs would be above the level (sixth to eighth grade) recommended by several healthcare organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.9,11,14 We also assessed the effect that orthopedic subspecialty coauthorship has on PEM readability.

Methods

In July 2014, we searched the AAOS online patient education library (Broken Bones & Injuries section, http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/menus/injury.cfm) and the AAOS OrthoPortal website (Trauma section, http://pubsearch.aaos.org/search?q=trauma&client=OrthoInfo&site=PATIENT&output=xml_no_dtd&proxystylesheet=OrthoInfo&filter=0) for all relevant OT-PEMs. Although OTA does not publish its own PEMs on its website, it coauthored several of the articles in the AAOS patient education library. Other subspecialty organizations, including the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM), the American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH), the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA), the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES), the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (AAHKS), and the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS), coauthored several of these online OT-PEMs as well.

Using the technique described by Badarudeen and Sabharwal,10 we saved all articles to be included in the study as separate Microsoft Word 2011 files. We saved them in plain-text format to remove any HTML tags and any other hidden formatting that might affect readability results. Then we edited them to remove elements that might affect readability result accuracy—deleted article topic–unrelated information (eg, copyright notice, disclaimers, author information) and all numerals, decimal points, bullets, abbreviations, paragraph breaks, colons, semicolons, and dashes.10Mr. Mohan used the Flesch-Kincaid (FK) Readability Scale to calculate grade level for each article. Microsoft Word 2011 was used as described in other investigations of orthopedic PEM readability2,10,12,13: Its readability function is enabled by going to the Tools tab and then to the Spelling & Grammar tool, where the “Show readability statistics” option is selected.10 Readability scores are calculated with the Spelling & Grammar tool; the readability score is displayed after completion of the spelling-and-grammar check. The formula used to calculate FK grade level is15: (0.39 × average number of words per sentence) + (11.8 × average number of syllables per word) – 15.59.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated for the FK grade levels. Student t tests were used to compare average FK grade levels of articles written exclusively by AAOS with those of articles coauthored by AAOS and other orthopedic subspecialty societies. A 2-sample unequal-variance t test was used, and significance was set at P < .05. Total number of articles written at or below the sixth- and eighth-grade levels, the reading levels recommended for PEMs, were tabulated.1,9-12 Intraobserver and interobserver reliabilities were calculated with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs): Mr. Mohan, who calculated the FK scores earlier, now 1 week later calculated the readability levels of 15 randomly selected articles10,11; in addition, Mr. Mohan and Dr. Yi independently calculated the readability levels of 30 randomly selected articles.10,11 The same method described earlier—edit plain-text files, then use Microsoft Word to obtain FK scores—was again used. ICCs of 0 to 0.24 correspond to poor correlation; 0.25 to 0.49, low correlation; 0.5 to 0.69, fair correlation; 0.7 to 0.89, good correlation; and 0.9 to 1.0, excellent correlation.10,11 All statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel 2011 and VassarStats (http://vassarstats.net/tu.html).

Results

Of the 115 AAOS website articles included in the study and reviewed, 18 were coauthored by OTA, 10 by AOSSM, 14 by POSNA, 2 by ASSH, 2 by ASES, 1 by AAHKS, 3 by AOFAS, 1 by AOSSM and ASES, and 1 by AOFAS and AOSSM.