User login

For opioid-related hospitalizations, men and women are equal

Equality is not always a good thing, particularly with opioids.

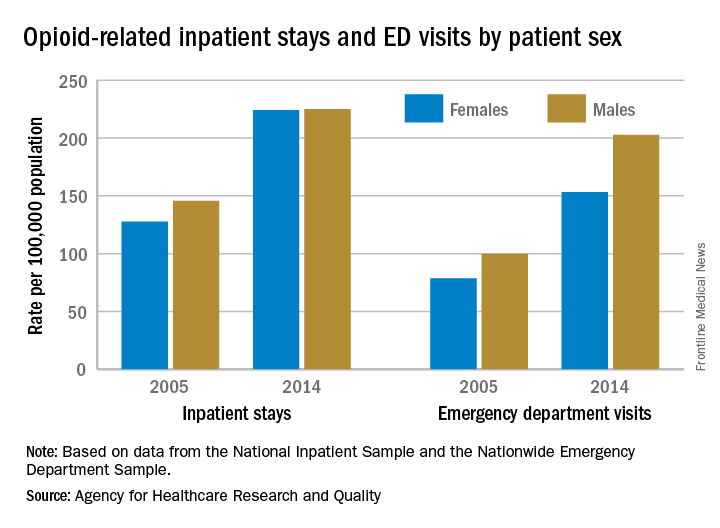

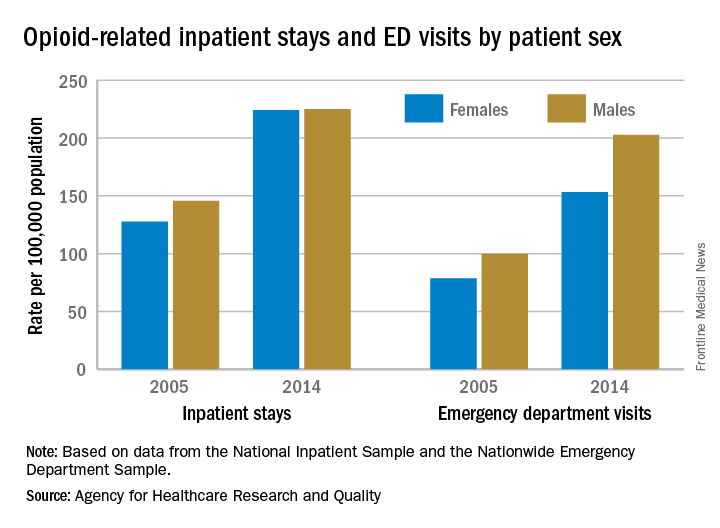

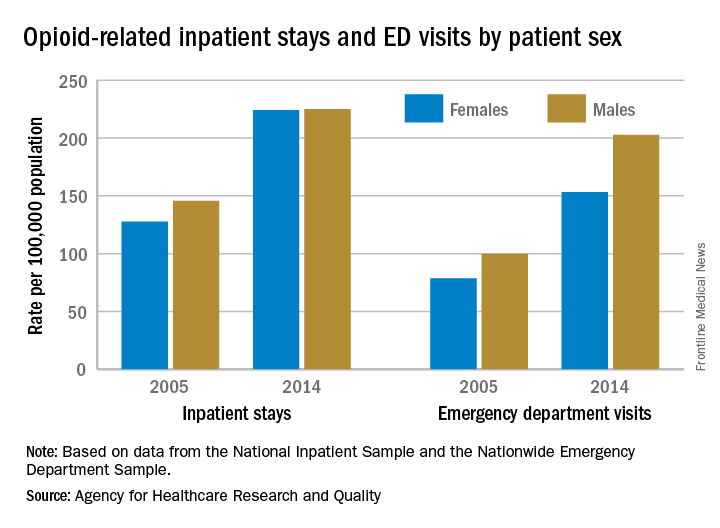

In 2005, the rate of opioid-related inpatient hospital stays was 145.6 per 100,000 population for males of all ages and 127.8 for females of all ages. By 2014, however, equality had arrived: Females had a rate of 224.1 per 100,000, compared with 225 for males, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Those increases in hospital admissions work out to 75% for females and 55% for males.

The states tell a similarly unequal story for opioid-related ED visits. In 2014, males had the higher rate in 23 states, and females had the higher rate in 7 states. (Washington, D.C., and 20 states do not participate in the State Emergency Department Databases and were not included in this analysis.)

Among the 30 participating states, Massachusetts had the highest visit rates for both males (598.8) and females (310.4), and Iowa had the lowest at 37 for males and 53.1 for females, AHRQ said.

The roles were reversed for opioid-related hospital admissions in the states in 2014: Females had the higher rate in 33 of the states participating in the State Inpatient Databases, compared with 11 states and the District of Columbia for males.

West Virginia had the highest rate for females at 371.2, and Washington, D.C., had the highest rate for males at 472. The lowest rates for both females (82.3) and males (63) were found in Iowa, according to the report.

Equality is not always a good thing, particularly with opioids.

In 2005, the rate of opioid-related inpatient hospital stays was 145.6 per 100,000 population for males of all ages and 127.8 for females of all ages. By 2014, however, equality had arrived: Females had a rate of 224.1 per 100,000, compared with 225 for males, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Those increases in hospital admissions work out to 75% for females and 55% for males.

The states tell a similarly unequal story for opioid-related ED visits. In 2014, males had the higher rate in 23 states, and females had the higher rate in 7 states. (Washington, D.C., and 20 states do not participate in the State Emergency Department Databases and were not included in this analysis.)

Among the 30 participating states, Massachusetts had the highest visit rates for both males (598.8) and females (310.4), and Iowa had the lowest at 37 for males and 53.1 for females, AHRQ said.

The roles were reversed for opioid-related hospital admissions in the states in 2014: Females had the higher rate in 33 of the states participating in the State Inpatient Databases, compared with 11 states and the District of Columbia for males.

West Virginia had the highest rate for females at 371.2, and Washington, D.C., had the highest rate for males at 472. The lowest rates for both females (82.3) and males (63) were found in Iowa, according to the report.

Equality is not always a good thing, particularly with opioids.

In 2005, the rate of opioid-related inpatient hospital stays was 145.6 per 100,000 population for males of all ages and 127.8 for females of all ages. By 2014, however, equality had arrived: Females had a rate of 224.1 per 100,000, compared with 225 for males, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Those increases in hospital admissions work out to 75% for females and 55% for males.

The states tell a similarly unequal story for opioid-related ED visits. In 2014, males had the higher rate in 23 states, and females had the higher rate in 7 states. (Washington, D.C., and 20 states do not participate in the State Emergency Department Databases and were not included in this analysis.)

Among the 30 participating states, Massachusetts had the highest visit rates for both males (598.8) and females (310.4), and Iowa had the lowest at 37 for males and 53.1 for females, AHRQ said.

The roles were reversed for opioid-related hospital admissions in the states in 2014: Females had the higher rate in 33 of the states participating in the State Inpatient Databases, compared with 11 states and the District of Columbia for males.

West Virginia had the highest rate for females at 371.2, and Washington, D.C., had the highest rate for males at 472. The lowest rates for both females (82.3) and males (63) were found in Iowa, according to the report.

Consortium Develops New Guideline for Dementia With Lewy Bodies

The international Dementia With Lewy Bodies Consortium has updated its guideline for diagnosing and treating this disease. “The updated clinical criteria and associated biomarkers hopefully will lead to earlier and more accurate diagnosis, and that is key to helping patients confront this challenging illness and maximize their quality of life,” said Bradley Boeve, MD, Professor of Neurology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and a coauthor. The guideline was published online ahead of print June 7 in Neurology.

The new guideline is a refinement of the consortium’s previous guideline, which was published in December 2005. To develop the new document, the consortium solicited and reviewed reports from four multidisciplinary expert working groups. The consortium also held a meeting in which patients and caregivers participated.

The revised consensus criteria distinguish between the clinical features and diagnostic biomarkers of the disease. The core clinical features are fluctuation in cognition, attention, and arousal; visual hallucinations (eg, of people, children, or animals); parkinsonism; and REM sleep behavior disorder, according to the authors. The criteria now list hypersomnia and hyposmia as supportive clinical features.

Direct biomarker evidence of Lewy body pathology is not available, said the authors. Indicative indirect biomarkers include reduced dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia demonstrated by single-photon emission computerized tomography or PET imaging, reduced uptake on metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy, and polysomnographic confirmation of REM sleep without atonia.

A neurologist can diagnose probable dementia with Lewy bodies if two or more of its core clinical features are present, with or without the presence of indicative biomarkers. This diagnosis also is warranted if only one core clinical feature is present, but one or more indicative biomarkers are present.

The document incorporates new information about previously reported aspects of dementia with Lewy bodies and gives greater diagnostic weight to REM sleep behavior disorder and 123iodine-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy. The authors describe the diagnostic role of other neuroimaging, electrophysiologic, and laboratory investigations. They recommend minor modifications to pathologic methods and criteria to take account of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic change, to add previously omitted Lewy-related pathology categories, and to include assessments for substantia nigra neuronal loss.

Because the literature contains few randomized controlled trials, the guideline’s recommendations about clinical management are based on expert opinion. Cholinesterase inhibitors can improve cognition, global function, activities of living, and neuropsychiatric symptoms, according to the authors. Nonpharmacologic management strategies should be developed and tested, they added.

“There remains a pressing need to understand the underlying neurobiology and pathophysiology of dementia with Lewy bodies, to develop and deliver clinical trials with both symptomatic and disease-modifying agents, and to help patients and carers worldwide to inform themselves about the disease, its prognosis, best available treatments, ongoing research, and how to get adequate support,” the authors concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017 Jun 7 [Epub ahead of print].

The international Dementia With Lewy Bodies Consortium has updated its guideline for diagnosing and treating this disease. “The updated clinical criteria and associated biomarkers hopefully will lead to earlier and more accurate diagnosis, and that is key to helping patients confront this challenging illness and maximize their quality of life,” said Bradley Boeve, MD, Professor of Neurology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and a coauthor. The guideline was published online ahead of print June 7 in Neurology.

The new guideline is a refinement of the consortium’s previous guideline, which was published in December 2005. To develop the new document, the consortium solicited and reviewed reports from four multidisciplinary expert working groups. The consortium also held a meeting in which patients and caregivers participated.

The revised consensus criteria distinguish between the clinical features and diagnostic biomarkers of the disease. The core clinical features are fluctuation in cognition, attention, and arousal; visual hallucinations (eg, of people, children, or animals); parkinsonism; and REM sleep behavior disorder, according to the authors. The criteria now list hypersomnia and hyposmia as supportive clinical features.

Direct biomarker evidence of Lewy body pathology is not available, said the authors. Indicative indirect biomarkers include reduced dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia demonstrated by single-photon emission computerized tomography or PET imaging, reduced uptake on metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy, and polysomnographic confirmation of REM sleep without atonia.

A neurologist can diagnose probable dementia with Lewy bodies if two or more of its core clinical features are present, with or without the presence of indicative biomarkers. This diagnosis also is warranted if only one core clinical feature is present, but one or more indicative biomarkers are present.

The document incorporates new information about previously reported aspects of dementia with Lewy bodies and gives greater diagnostic weight to REM sleep behavior disorder and 123iodine-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy. The authors describe the diagnostic role of other neuroimaging, electrophysiologic, and laboratory investigations. They recommend minor modifications to pathologic methods and criteria to take account of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic change, to add previously omitted Lewy-related pathology categories, and to include assessments for substantia nigra neuronal loss.

Because the literature contains few randomized controlled trials, the guideline’s recommendations about clinical management are based on expert opinion. Cholinesterase inhibitors can improve cognition, global function, activities of living, and neuropsychiatric symptoms, according to the authors. Nonpharmacologic management strategies should be developed and tested, they added.

“There remains a pressing need to understand the underlying neurobiology and pathophysiology of dementia with Lewy bodies, to develop and deliver clinical trials with both symptomatic and disease-modifying agents, and to help patients and carers worldwide to inform themselves about the disease, its prognosis, best available treatments, ongoing research, and how to get adequate support,” the authors concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017 Jun 7 [Epub ahead of print].

The international Dementia With Lewy Bodies Consortium has updated its guideline for diagnosing and treating this disease. “The updated clinical criteria and associated biomarkers hopefully will lead to earlier and more accurate diagnosis, and that is key to helping patients confront this challenging illness and maximize their quality of life,” said Bradley Boeve, MD, Professor of Neurology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and a coauthor. The guideline was published online ahead of print June 7 in Neurology.

The new guideline is a refinement of the consortium’s previous guideline, which was published in December 2005. To develop the new document, the consortium solicited and reviewed reports from four multidisciplinary expert working groups. The consortium also held a meeting in which patients and caregivers participated.

The revised consensus criteria distinguish between the clinical features and diagnostic biomarkers of the disease. The core clinical features are fluctuation in cognition, attention, and arousal; visual hallucinations (eg, of people, children, or animals); parkinsonism; and REM sleep behavior disorder, according to the authors. The criteria now list hypersomnia and hyposmia as supportive clinical features.

Direct biomarker evidence of Lewy body pathology is not available, said the authors. Indicative indirect biomarkers include reduced dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia demonstrated by single-photon emission computerized tomography or PET imaging, reduced uptake on metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy, and polysomnographic confirmation of REM sleep without atonia.

A neurologist can diagnose probable dementia with Lewy bodies if two or more of its core clinical features are present, with or without the presence of indicative biomarkers. This diagnosis also is warranted if only one core clinical feature is present, but one or more indicative biomarkers are present.

The document incorporates new information about previously reported aspects of dementia with Lewy bodies and gives greater diagnostic weight to REM sleep behavior disorder and 123iodine-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy. The authors describe the diagnostic role of other neuroimaging, electrophysiologic, and laboratory investigations. They recommend minor modifications to pathologic methods and criteria to take account of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic change, to add previously omitted Lewy-related pathology categories, and to include assessments for substantia nigra neuronal loss.

Because the literature contains few randomized controlled trials, the guideline’s recommendations about clinical management are based on expert opinion. Cholinesterase inhibitors can improve cognition, global function, activities of living, and neuropsychiatric symptoms, according to the authors. Nonpharmacologic management strategies should be developed and tested, they added.

“There remains a pressing need to understand the underlying neurobiology and pathophysiology of dementia with Lewy bodies, to develop and deliver clinical trials with both symptomatic and disease-modifying agents, and to help patients and carers worldwide to inform themselves about the disease, its prognosis, best available treatments, ongoing research, and how to get adequate support,” the authors concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017 Jun 7 [Epub ahead of print].

Can Cannabis Help Patients With Parkinson’s Disease?

VANCOUVER—Anecdotal reports, patient surveys, and studies have suggested that cannabis may help treat motor and nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Two studies presented at the 21st International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders further explored this possibility and assessed the effects of oral cannabidiol (CBD) and inhaled cannabis in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Cannabidiol

Maureen A. Leehey, MD, Professor of Neurology and Chief of the Movement Disorders Division at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and colleagues conducted a phase II, open-label, dose-escalation study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of CBD (Epidiolex) in Parkinson’s disease. In addition, the researchers looked at secondary efficacy measures, including change in tremor, cognition, anxiety, psychosis, sleep, daytime sleepiness, mood, fatigue, and pain.

The researchers enrolled 13 patients who had a rest tremor amplitude score of 2 or greater on item 3.17 of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). They excluded patients who had taken cannabinoids in the previous 30 days or had a history of drug or alcohol dependence.

Over a 31-day treatment period, patients received 5-, 7.5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-mg/kg/day doses of CBD. They received the highest dose on days 17–31. Patients had clinic visits at screening, baseline, and after the 31-day treatment period. Of the 13 patients enrolled, one failed the screening visit, another patient did not start the study drug, and another patient was on the study drug for two days. The 10 remaining patients were included in the adverse events analysis. Adverse events were mostly mild to moderate and included fatigue, diarrhea, somnolence, elevated liver enzymes, and dizziness. Three of the 10 patients dropped out of the study due to intolerance. One of the three patients had an allergic reaction and two had abdominal pain. There were no serious adverse events.

Among the seven patients who completed the treatment period and were included in the efficacy analysis, mean total UPDRS score significantly decreased from 45.9 at baseline to 36.4 at the final visit. UPDRS motor score significantly decreased from 27.3 to 20.3. Mean rigidity subscore significantly decreased from 9.14 to 6.29. In addition, data hinted that CBD treatment might have reduced pain and irritability, the researchers said.

These preliminary results indicate that CBD is tolerated, safe, and has beneficial effects in Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Leehey and colleagues said. The investigators next plan to conduct a crossover, double-blind, randomized controlled trial with 50 subjects.

Inhaled Cannabis

Laurie K. Mischley, ND, PhD, MPH, Associate Clinical Investigator at Bastyr University Research Institute in Kenmore, Washington, and colleagues evaluated the effect of inhaled cannabis on Parkinson’s disease tremor using motion sensors and qualitative interviews.

The study included patients with Parkinson’s disease who used cannabis in the state of Washington. Patients wore a movement monitor for two weeks and logged their cannabis use in a journal. Sensors recorded the frequency and amplitude of tremor during waking hours, and participants pressed a button on the motion sensor every time they used cannabis. The researchers compared tremor duration and magnitude in the hour before and after inhaled cannabis use. After two weeks, interviewers asked participants standardized, open-ended, nonleading questions about their perception of the effects of cannabis on their symptoms.

The 10 patients for whom they had data had a mean age of 60 (range, 40 to 74) and a mean time since diagnosis of 6.3 years. Among four participants who had more than 10 cannabis exposures and a measurable tremor more than 2% of the time in the hour before cannabis use during the study, the percent of the time with detected tremor significantly decreased in the hour after use. Sensor data suggested that tremor reduction may have been sustained for three hours after exposure to cannabis, the researchers said. “In those with a persistent tremor, there was a consistent decrease in the tremor persistence and in detected tremor magnitude following cannabis use,” the investigators said.

During the follow-up interview, nine of the 10 participants thought that cannabis helped their symptoms, and one patient thought it worsened symptoms. “The one participant who reported cannabis worsening symptoms specifically described, ‘sometimes it speeds up the tremor at the start’ but ‘then it relaxes it,’” the researchers said.

Side effects reported by patients included sleepiness, sluggishness, concerns about social stigma and driving, short-term memory, and dry throat.

“Improved sleep was an unsolicited theme during the qualitative interviews, with 60% of individuals reporting improvements,” Dr. Mischley and colleagues said. “The qualitative interviews suggest patients perceive cannabis to have therapeutic potential for Parkinson’s disease symptom management. These data suggest further investigation of cannabis for impaired sleep is warranted.”

The researchers noted that most subjects had a mild, intermittent tremor that was not reliably detected by the motion sensors. Future studies should enroll subjects with more pronounced tremor and use consistent cannabis strains, doses, and delivery systems, they said.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Chagas MH, Zuardi AW, Tumas V, et al. Effects of cannabidiol in the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(11):1088-1098.

Finseth TA, Hedeman JL, Brown RP 2nd, et al. Self-reported efficacy of cannabis and other complementary medicine modalities by Parkinson’s disease patients in Colorado. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:874849.

Koppel BS, Brust JC, Fife T, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014; 82(17):1556-1563.

Lotan I, Treves TA, Roditi Y, Djaldetti R. Cannabis (medical marijuana) treatment for motor and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson disease: an open-label observational study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2014;37(2):41-44.

Venderová K, Ruzicka E, Vorísek V, Visnovský P. Survey on cannabis use in Parkinson’s disease: subjective improvement of motor symptoms. Mov Disord. 2004;19(9):1102-1106.

Zuardi AW, Crippa JA, Hallak JE, et al. Cannabidiol for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(8):979-983.

VANCOUVER—Anecdotal reports, patient surveys, and studies have suggested that cannabis may help treat motor and nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Two studies presented at the 21st International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders further explored this possibility and assessed the effects of oral cannabidiol (CBD) and inhaled cannabis in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Cannabidiol

Maureen A. Leehey, MD, Professor of Neurology and Chief of the Movement Disorders Division at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and colleagues conducted a phase II, open-label, dose-escalation study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of CBD (Epidiolex) in Parkinson’s disease. In addition, the researchers looked at secondary efficacy measures, including change in tremor, cognition, anxiety, psychosis, sleep, daytime sleepiness, mood, fatigue, and pain.

The researchers enrolled 13 patients who had a rest tremor amplitude score of 2 or greater on item 3.17 of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). They excluded patients who had taken cannabinoids in the previous 30 days or had a history of drug or alcohol dependence.

Over a 31-day treatment period, patients received 5-, 7.5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-mg/kg/day doses of CBD. They received the highest dose on days 17–31. Patients had clinic visits at screening, baseline, and after the 31-day treatment period. Of the 13 patients enrolled, one failed the screening visit, another patient did not start the study drug, and another patient was on the study drug for two days. The 10 remaining patients were included in the adverse events analysis. Adverse events were mostly mild to moderate and included fatigue, diarrhea, somnolence, elevated liver enzymes, and dizziness. Three of the 10 patients dropped out of the study due to intolerance. One of the three patients had an allergic reaction and two had abdominal pain. There were no serious adverse events.

Among the seven patients who completed the treatment period and were included in the efficacy analysis, mean total UPDRS score significantly decreased from 45.9 at baseline to 36.4 at the final visit. UPDRS motor score significantly decreased from 27.3 to 20.3. Mean rigidity subscore significantly decreased from 9.14 to 6.29. In addition, data hinted that CBD treatment might have reduced pain and irritability, the researchers said.

These preliminary results indicate that CBD is tolerated, safe, and has beneficial effects in Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Leehey and colleagues said. The investigators next plan to conduct a crossover, double-blind, randomized controlled trial with 50 subjects.

Inhaled Cannabis

Laurie K. Mischley, ND, PhD, MPH, Associate Clinical Investigator at Bastyr University Research Institute in Kenmore, Washington, and colleagues evaluated the effect of inhaled cannabis on Parkinson’s disease tremor using motion sensors and qualitative interviews.

The study included patients with Parkinson’s disease who used cannabis in the state of Washington. Patients wore a movement monitor for two weeks and logged their cannabis use in a journal. Sensors recorded the frequency and amplitude of tremor during waking hours, and participants pressed a button on the motion sensor every time they used cannabis. The researchers compared tremor duration and magnitude in the hour before and after inhaled cannabis use. After two weeks, interviewers asked participants standardized, open-ended, nonleading questions about their perception of the effects of cannabis on their symptoms.

The 10 patients for whom they had data had a mean age of 60 (range, 40 to 74) and a mean time since diagnosis of 6.3 years. Among four participants who had more than 10 cannabis exposures and a measurable tremor more than 2% of the time in the hour before cannabis use during the study, the percent of the time with detected tremor significantly decreased in the hour after use. Sensor data suggested that tremor reduction may have been sustained for three hours after exposure to cannabis, the researchers said. “In those with a persistent tremor, there was a consistent decrease in the tremor persistence and in detected tremor magnitude following cannabis use,” the investigators said.

During the follow-up interview, nine of the 10 participants thought that cannabis helped their symptoms, and one patient thought it worsened symptoms. “The one participant who reported cannabis worsening symptoms specifically described, ‘sometimes it speeds up the tremor at the start’ but ‘then it relaxes it,’” the researchers said.

Side effects reported by patients included sleepiness, sluggishness, concerns about social stigma and driving, short-term memory, and dry throat.

“Improved sleep was an unsolicited theme during the qualitative interviews, with 60% of individuals reporting improvements,” Dr. Mischley and colleagues said. “The qualitative interviews suggest patients perceive cannabis to have therapeutic potential for Parkinson’s disease symptom management. These data suggest further investigation of cannabis for impaired sleep is warranted.”

The researchers noted that most subjects had a mild, intermittent tremor that was not reliably detected by the motion sensors. Future studies should enroll subjects with more pronounced tremor and use consistent cannabis strains, doses, and delivery systems, they said.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Chagas MH, Zuardi AW, Tumas V, et al. Effects of cannabidiol in the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(11):1088-1098.

Finseth TA, Hedeman JL, Brown RP 2nd, et al. Self-reported efficacy of cannabis and other complementary medicine modalities by Parkinson’s disease patients in Colorado. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:874849.

Koppel BS, Brust JC, Fife T, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014; 82(17):1556-1563.

Lotan I, Treves TA, Roditi Y, Djaldetti R. Cannabis (medical marijuana) treatment for motor and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson disease: an open-label observational study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2014;37(2):41-44.

Venderová K, Ruzicka E, Vorísek V, Visnovský P. Survey on cannabis use in Parkinson’s disease: subjective improvement of motor symptoms. Mov Disord. 2004;19(9):1102-1106.

Zuardi AW, Crippa JA, Hallak JE, et al. Cannabidiol for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(8):979-983.

VANCOUVER—Anecdotal reports, patient surveys, and studies have suggested that cannabis may help treat motor and nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Two studies presented at the 21st International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders further explored this possibility and assessed the effects of oral cannabidiol (CBD) and inhaled cannabis in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Cannabidiol

Maureen A. Leehey, MD, Professor of Neurology and Chief of the Movement Disorders Division at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and colleagues conducted a phase II, open-label, dose-escalation study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of CBD (Epidiolex) in Parkinson’s disease. In addition, the researchers looked at secondary efficacy measures, including change in tremor, cognition, anxiety, psychosis, sleep, daytime sleepiness, mood, fatigue, and pain.

The researchers enrolled 13 patients who had a rest tremor amplitude score of 2 or greater on item 3.17 of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). They excluded patients who had taken cannabinoids in the previous 30 days or had a history of drug or alcohol dependence.

Over a 31-day treatment period, patients received 5-, 7.5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-mg/kg/day doses of CBD. They received the highest dose on days 17–31. Patients had clinic visits at screening, baseline, and after the 31-day treatment period. Of the 13 patients enrolled, one failed the screening visit, another patient did not start the study drug, and another patient was on the study drug for two days. The 10 remaining patients were included in the adverse events analysis. Adverse events were mostly mild to moderate and included fatigue, diarrhea, somnolence, elevated liver enzymes, and dizziness. Three of the 10 patients dropped out of the study due to intolerance. One of the three patients had an allergic reaction and two had abdominal pain. There were no serious adverse events.

Among the seven patients who completed the treatment period and were included in the efficacy analysis, mean total UPDRS score significantly decreased from 45.9 at baseline to 36.4 at the final visit. UPDRS motor score significantly decreased from 27.3 to 20.3. Mean rigidity subscore significantly decreased from 9.14 to 6.29. In addition, data hinted that CBD treatment might have reduced pain and irritability, the researchers said.

These preliminary results indicate that CBD is tolerated, safe, and has beneficial effects in Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Leehey and colleagues said. The investigators next plan to conduct a crossover, double-blind, randomized controlled trial with 50 subjects.

Inhaled Cannabis

Laurie K. Mischley, ND, PhD, MPH, Associate Clinical Investigator at Bastyr University Research Institute in Kenmore, Washington, and colleagues evaluated the effect of inhaled cannabis on Parkinson’s disease tremor using motion sensors and qualitative interviews.

The study included patients with Parkinson’s disease who used cannabis in the state of Washington. Patients wore a movement monitor for two weeks and logged their cannabis use in a journal. Sensors recorded the frequency and amplitude of tremor during waking hours, and participants pressed a button on the motion sensor every time they used cannabis. The researchers compared tremor duration and magnitude in the hour before and after inhaled cannabis use. After two weeks, interviewers asked participants standardized, open-ended, nonleading questions about their perception of the effects of cannabis on their symptoms.

The 10 patients for whom they had data had a mean age of 60 (range, 40 to 74) and a mean time since diagnosis of 6.3 years. Among four participants who had more than 10 cannabis exposures and a measurable tremor more than 2% of the time in the hour before cannabis use during the study, the percent of the time with detected tremor significantly decreased in the hour after use. Sensor data suggested that tremor reduction may have been sustained for three hours after exposure to cannabis, the researchers said. “In those with a persistent tremor, there was a consistent decrease in the tremor persistence and in detected tremor magnitude following cannabis use,” the investigators said.

During the follow-up interview, nine of the 10 participants thought that cannabis helped their symptoms, and one patient thought it worsened symptoms. “The one participant who reported cannabis worsening symptoms specifically described, ‘sometimes it speeds up the tremor at the start’ but ‘then it relaxes it,’” the researchers said.

Side effects reported by patients included sleepiness, sluggishness, concerns about social stigma and driving, short-term memory, and dry throat.

“Improved sleep was an unsolicited theme during the qualitative interviews, with 60% of individuals reporting improvements,” Dr. Mischley and colleagues said. “The qualitative interviews suggest patients perceive cannabis to have therapeutic potential for Parkinson’s disease symptom management. These data suggest further investigation of cannabis for impaired sleep is warranted.”

The researchers noted that most subjects had a mild, intermittent tremor that was not reliably detected by the motion sensors. Future studies should enroll subjects with more pronounced tremor and use consistent cannabis strains, doses, and delivery systems, they said.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Chagas MH, Zuardi AW, Tumas V, et al. Effects of cannabidiol in the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(11):1088-1098.

Finseth TA, Hedeman JL, Brown RP 2nd, et al. Self-reported efficacy of cannabis and other complementary medicine modalities by Parkinson’s disease patients in Colorado. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:874849.

Koppel BS, Brust JC, Fife T, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014; 82(17):1556-1563.

Lotan I, Treves TA, Roditi Y, Djaldetti R. Cannabis (medical marijuana) treatment for motor and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson disease: an open-label observational study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2014;37(2):41-44.

Venderová K, Ruzicka E, Vorísek V, Visnovský P. Survey on cannabis use in Parkinson’s disease: subjective improvement of motor symptoms. Mov Disord. 2004;19(9):1102-1106.

Zuardi AW, Crippa JA, Hallak JE, et al. Cannabidiol for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(8):979-983.

Benign Epilepsy With Centrotemporal Spikes Entails a Risk of SUDEP

Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) is associated with a low risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), according to a study published in the June 1 JAMA Neurology. Clinicians should consider discussing this rare outcome with patients and their families and factoring this risk into treatment decisions, according to the authors.

“Our data suggest that even children with BECTS who have only focal motor or infrequent seizures are at risk for SUDEP,” said Kyra Doumlele, of New York University School of Medicine’s Department of Neurology, and colleagues.

BECTS is the most common focal epilepsy syndrome among children. This form of epilepsy typically has a good prognosis and tends to resolve before age 16. As a result, many neurologists do not prescribe antiseizure medications for patients with BECTS. However, patients with this disease have predominantly nocturnal seizures and some generalized tonic-clonic seizures, which could put them at risk for SUDEP.

SUDEP in well-characterized patients with BECTS has not been documented. Ms. Doumlele and colleagues sought to determine whether cases of BECTS were present in the North American SUDEP Registry (NASR), a clinical and biospecimen repository established to investigate the risk factors and mechanisms for SUDEP.

Researchers searched records of 189 decedents enrolled in the NASR from June 3, 2011, to June 3, 2016. Investigators identified cases based on a diagnosis of BECTS by parental report during the intake interview and confirmation from treating physicians. Diagnostic criteria for BECTS included the onset of epilepsy at age 3 to age 13, normal cognition and development before onset of seizures, no symptomatic cause of epilepsy, and EEG results reporting discharges consistent with BECTS.

Investigators identified three boys who had received a diagnosis of BECTS. The first patient and third patient met all clinical and EEG features for a diagnosis of BECTS. The second patient had limited EEG data, but had classic clinical features of BECTS.

The first patient (age 9) had seizure onset at age 5. He experienced an increase in focal motor and secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the six months before his death.

The second patient (age 12) developed epilepsy at age 11. Four months prior to death, he experienced at least three nocturnal generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The autopsy report listed his cause of death as “cardiac dysrhythmia associated with lymphocytic myocarditis, left anterior descending coronary artery intramuscular tunneling, and possible hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.”

The third patient (age 13) developed epilepsy at age 3. His severe postictal state indicated that he might have had two generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the year before he died. His death was unwitnessed, and no autopsy was performed. None of these patients had received antiseizure medications or counseling with their families about the risk of SUDEP.

“These cases illustrate that SUDEP is a rare complication of BECTS, and this information should be shared with families at or soon after diagnosis,” said Ms. Doumlele and colleagues.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Doumlele K, Friedman D, Buchhalter J, et al. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy among patients with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(6):645-649.

Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) is associated with a low risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), according to a study published in the June 1 JAMA Neurology. Clinicians should consider discussing this rare outcome with patients and their families and factoring this risk into treatment decisions, according to the authors.

“Our data suggest that even children with BECTS who have only focal motor or infrequent seizures are at risk for SUDEP,” said Kyra Doumlele, of New York University School of Medicine’s Department of Neurology, and colleagues.

BECTS is the most common focal epilepsy syndrome among children. This form of epilepsy typically has a good prognosis and tends to resolve before age 16. As a result, many neurologists do not prescribe antiseizure medications for patients with BECTS. However, patients with this disease have predominantly nocturnal seizures and some generalized tonic-clonic seizures, which could put them at risk for SUDEP.

SUDEP in well-characterized patients with BECTS has not been documented. Ms. Doumlele and colleagues sought to determine whether cases of BECTS were present in the North American SUDEP Registry (NASR), a clinical and biospecimen repository established to investigate the risk factors and mechanisms for SUDEP.

Researchers searched records of 189 decedents enrolled in the NASR from June 3, 2011, to June 3, 2016. Investigators identified cases based on a diagnosis of BECTS by parental report during the intake interview and confirmation from treating physicians. Diagnostic criteria for BECTS included the onset of epilepsy at age 3 to age 13, normal cognition and development before onset of seizures, no symptomatic cause of epilepsy, and EEG results reporting discharges consistent with BECTS.

Investigators identified three boys who had received a diagnosis of BECTS. The first patient and third patient met all clinical and EEG features for a diagnosis of BECTS. The second patient had limited EEG data, but had classic clinical features of BECTS.

The first patient (age 9) had seizure onset at age 5. He experienced an increase in focal motor and secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the six months before his death.

The second patient (age 12) developed epilepsy at age 11. Four months prior to death, he experienced at least three nocturnal generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The autopsy report listed his cause of death as “cardiac dysrhythmia associated with lymphocytic myocarditis, left anterior descending coronary artery intramuscular tunneling, and possible hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.”

The third patient (age 13) developed epilepsy at age 3. His severe postictal state indicated that he might have had two generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the year before he died. His death was unwitnessed, and no autopsy was performed. None of these patients had received antiseizure medications or counseling with their families about the risk of SUDEP.

“These cases illustrate that SUDEP is a rare complication of BECTS, and this information should be shared with families at or soon after diagnosis,” said Ms. Doumlele and colleagues.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Doumlele K, Friedman D, Buchhalter J, et al. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy among patients with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(6):645-649.

Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) is associated with a low risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), according to a study published in the June 1 JAMA Neurology. Clinicians should consider discussing this rare outcome with patients and their families and factoring this risk into treatment decisions, according to the authors.

“Our data suggest that even children with BECTS who have only focal motor or infrequent seizures are at risk for SUDEP,” said Kyra Doumlele, of New York University School of Medicine’s Department of Neurology, and colleagues.

BECTS is the most common focal epilepsy syndrome among children. This form of epilepsy typically has a good prognosis and tends to resolve before age 16. As a result, many neurologists do not prescribe antiseizure medications for patients with BECTS. However, patients with this disease have predominantly nocturnal seizures and some generalized tonic-clonic seizures, which could put them at risk for SUDEP.

SUDEP in well-characterized patients with BECTS has not been documented. Ms. Doumlele and colleagues sought to determine whether cases of BECTS were present in the North American SUDEP Registry (NASR), a clinical and biospecimen repository established to investigate the risk factors and mechanisms for SUDEP.

Researchers searched records of 189 decedents enrolled in the NASR from June 3, 2011, to June 3, 2016. Investigators identified cases based on a diagnosis of BECTS by parental report during the intake interview and confirmation from treating physicians. Diagnostic criteria for BECTS included the onset of epilepsy at age 3 to age 13, normal cognition and development before onset of seizures, no symptomatic cause of epilepsy, and EEG results reporting discharges consistent with BECTS.

Investigators identified three boys who had received a diagnosis of BECTS. The first patient and third patient met all clinical and EEG features for a diagnosis of BECTS. The second patient had limited EEG data, but had classic clinical features of BECTS.

The first patient (age 9) had seizure onset at age 5. He experienced an increase in focal motor and secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the six months before his death.

The second patient (age 12) developed epilepsy at age 11. Four months prior to death, he experienced at least three nocturnal generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The autopsy report listed his cause of death as “cardiac dysrhythmia associated with lymphocytic myocarditis, left anterior descending coronary artery intramuscular tunneling, and possible hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.”

The third patient (age 13) developed epilepsy at age 3. His severe postictal state indicated that he might have had two generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the year before he died. His death was unwitnessed, and no autopsy was performed. None of these patients had received antiseizure medications or counseling with their families about the risk of SUDEP.

“These cases illustrate that SUDEP is a rare complication of BECTS, and this information should be shared with families at or soon after diagnosis,” said Ms. Doumlele and colleagues.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Doumlele K, Friedman D, Buchhalter J, et al. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy among patients with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(6):645-649.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - June 2017

BY CATALINA MATIZ, MD, AND ANDREA WALDMAN, MD

Serum sickness

How does serum sickness–like reaction present?

At the time of initial evaluation, the patient presented with a recent history of fever, edema of the hands and feet, limited gait, and a diffuse, persistent serpiginous and annular dermatitis for 48 hours. Of note, the patient was prescribed a 10-day course of amoxicillin for otitis media 8 days prior to initial presentation.

The distribution and morphology of our patient’s cutaneous eruption, in combination with the systemic symptoms, facial and acral edema, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia, were highly suggestive of serum sickness–like reaction (SSLR). SSLR is an allergic reaction characterized by a cutaneous eruption, arthralgias, fever, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, and malaise. True serum sickness was originally distinguished in 1905 as a self-limited illness that occurred in several patients after administration of equine diphtheria antitoxin.1 Today this reaction is rarely noted in the pediatric population.

Pathogenically, true serum sickness represents a type III arthus hypersensitivity reaction to proteins in toxins or drugs, mediated by circulating antigen-antibody complexes. In contrast, SSLR is not associated with circulating immune complexes or hypocomplementemia.2 Histopathology frequently resembles the findings of urticaria, including a perivascular and dermal inflammatory infiltrate with associated neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes.2 Several hypotheses concerning the etiology of SSLR have been suggested in the literature, most commonly including an inflammatory response to defective drug metabolism. However, definitive pathology remains unknown.3

Initially, an urticarial rash and low-grade fever typically develop 7-21 days after exposure to the offending agent or sooner in individuals previously sensitized to the drug. The lesions quickly evolve to the classic purpuric lesions of SSLR over the following 24-48 hours. These dermatologic findings include pink to red oval and/or polycyclic lesions with large central areas of purple discoloration, classically involving the trunk, extremities, and/or face. The lesions may be discrete, scattered, or confluent.2

Several medications are associated with SSLR, but cefaclor is most frequently implicated, occurring in 0.2% of treated children.4,5 Other common culprits include penicillins, tetracycline, sulfonamides, macrolides, ciprofloxacin, rifampin, griseofulvin, bupropion, and fluoxetine.6-10 More recently, biologic agents have been implicated in SSLR, including rituximab, efalizumab, and infliximab.11,12 SSLR also has been described in association with immunizations (hepatitis B, tetanus, and rabies) and active infections with hepatitis B or C.13,14

The diagnosis of SSLR is primarily clinical, formulated based on the constellation of characteristic lesions, fever, adenopathy, facial edema, and/or arthralgia in conjunction with recent history (within 7-21 days) of offending medications or agents. Supporting laboratory findings include normal or mildly low complement C3 and C4 levels and mild proteinuria. Abnormalities in liver and renal function test results are rare, in contrast to true serum sickness. Biopsy and histopathology may be utilized to exclude other diagnoses.2

An extensive variety of cutaneous conditions bearing a resemblance to SSLR were considered in the differential, including urticaria multiforme, Kawasaki disease, erythema multiforme, and urticarial vasculitis. A common challenge for practitioners is distinguishing SSLR from similar dermatoses, particularly urticarial multiforme (UM), which some experts consider clinically related to SSLR. Despite the cutaneous similarities of UM and SSLR, including urticarial plaques with an associated central duskiness, SSLR tends to have a more delayed onset following offending agent exposure and more extracutaneous symptoms, especially arthralgias and/or arthritis, lymphadenopathy, and higher fevers.15 The rash of UM classically presents 1-3 days following agent exposure or illness, whereas SSLR presentation is delayed 1-3 weeks. Further distinguishing UM is the transient nature of the individual lesions, each lasting less than 24 hours.

Urticarial vasculitis (UV), morphologically similar to SSLR and UM, causes persistent urticarial-like plaques that last longer than 24-48 hours and resolve with bruising. Biopsy results revealing leukocytoclastic vasculitis distinguish UV, but case reports exist reporting leukocytoclastic vasculitis in association with SSLR.

Erythema multiforme (EM), a hypersensitivity reaction usually triggered by infections (most commonly herpes simplex virus), also may appear morphologically similar to SSLR. These lesions also persist for longer than 24-48 hours and often have a target appearance with central duskiness that sometimes can blister. Patients may have mucosal involvement with vesicles and erosions, compared with patients with SSLR in whom mucosal lesions are rarely seen. Medications are an uncommon trigger for EM, occurring in less than 10% of cases, and alternative drug eruptions including SSLR should be excluded prior to diagnosis.

Other disorders commonly presenting with similar extracutaneous manifestations to SSLR and concomitant dermatitis were further excluded based on the morphologic appearance of the lesions and other clinical dissimilarities. Henoch-Schönlein purpura, which also may present with arthralgia, fever, GI symptoms, and extremity edema, was unlikely given the urticarial appearance of the lesions, rather than palpable purpura. Furthermore, the arthritis/arthralgia of Henoch-Schönlein purpura is typically oligoarticular, affecting the large joints of the lower extremities most frequently.

If the patient presents with persistent fever for more than 5 days, Kawasaki disease may be considered in the differential and ruled out with clinical and laboratory assessment. The presence of fever, lymphadenopathy, and acute rash similarly should prompt consideration of a clinical and laboratory work-up for drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Morphologically, this drug reaction is characterized by a maculopapular eruption more than 3 weeks after exposure to an offending agent. Patients with SSLR respond favorably to cessation of the causative drug and supportive care with antipyretics, NSAIDs, and antihistamines. The cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations of this drug reaction typically disappear within 2-3 weeks after discontinuation of the offending agent. If symptoms are severe, a short systemic corticosteroid course may be warranted. Our patient’s symptoms completely resolved within 2-3 weeks of discontinuing amoxicillin therapy.

Dr. Matiz is assistant professor of dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Waldman is a clinical research fellow at the hospital. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. von Pirquet, C. Frh, and Bela Schick. “Serum Sickness.” Translated by B. Schick. (London: Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, 1951).

2. Cutis. 2002 May;69(5):395-7.

3. J Pediatr. 1994 Nov;125(5 Pt 1):805-11.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991 Nov;25(5 Pt 1):805-8.

5. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003 Dec;39(9):677-81.

6. Ann Pharmacother. 1996 May;30(5):481-3.

7. J Hosp Med. 2011 Apr;6(4):231-2.

8. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014 Mar;6(2):183-5.

9. Ann Pharmacother. 2004 Apr;38(4):609-11.

10. Ann Pharmacother. 2000 Apr;34(4):471-3.

11. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013 Sep;19(6):360.

12. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012 Feb;15(1):e6-7.

13. Am J Med Sci. 2013 May;345(5):412-3.

14. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007 Sep;26(3):179-87.

15. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013 Mar;6(3):34-9.

BY CATALINA MATIZ, MD, AND ANDREA WALDMAN, MD

Serum sickness

How does serum sickness–like reaction present?

At the time of initial evaluation, the patient presented with a recent history of fever, edema of the hands and feet, limited gait, and a diffuse, persistent serpiginous and annular dermatitis for 48 hours. Of note, the patient was prescribed a 10-day course of amoxicillin for otitis media 8 days prior to initial presentation.

The distribution and morphology of our patient’s cutaneous eruption, in combination with the systemic symptoms, facial and acral edema, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia, were highly suggestive of serum sickness–like reaction (SSLR). SSLR is an allergic reaction characterized by a cutaneous eruption, arthralgias, fever, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, and malaise. True serum sickness was originally distinguished in 1905 as a self-limited illness that occurred in several patients after administration of equine diphtheria antitoxin.1 Today this reaction is rarely noted in the pediatric population.

Pathogenically, true serum sickness represents a type III arthus hypersensitivity reaction to proteins in toxins or drugs, mediated by circulating antigen-antibody complexes. In contrast, SSLR is not associated with circulating immune complexes or hypocomplementemia.2 Histopathology frequently resembles the findings of urticaria, including a perivascular and dermal inflammatory infiltrate with associated neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes.2 Several hypotheses concerning the etiology of SSLR have been suggested in the literature, most commonly including an inflammatory response to defective drug metabolism. However, definitive pathology remains unknown.3

Initially, an urticarial rash and low-grade fever typically develop 7-21 days after exposure to the offending agent or sooner in individuals previously sensitized to the drug. The lesions quickly evolve to the classic purpuric lesions of SSLR over the following 24-48 hours. These dermatologic findings include pink to red oval and/or polycyclic lesions with large central areas of purple discoloration, classically involving the trunk, extremities, and/or face. The lesions may be discrete, scattered, or confluent.2

Several medications are associated with SSLR, but cefaclor is most frequently implicated, occurring in 0.2% of treated children.4,5 Other common culprits include penicillins, tetracycline, sulfonamides, macrolides, ciprofloxacin, rifampin, griseofulvin, bupropion, and fluoxetine.6-10 More recently, biologic agents have been implicated in SSLR, including rituximab, efalizumab, and infliximab.11,12 SSLR also has been described in association with immunizations (hepatitis B, tetanus, and rabies) and active infections with hepatitis B or C.13,14

The diagnosis of SSLR is primarily clinical, formulated based on the constellation of characteristic lesions, fever, adenopathy, facial edema, and/or arthralgia in conjunction with recent history (within 7-21 days) of offending medications or agents. Supporting laboratory findings include normal or mildly low complement C3 and C4 levels and mild proteinuria. Abnormalities in liver and renal function test results are rare, in contrast to true serum sickness. Biopsy and histopathology may be utilized to exclude other diagnoses.2

An extensive variety of cutaneous conditions bearing a resemblance to SSLR were considered in the differential, including urticaria multiforme, Kawasaki disease, erythema multiforme, and urticarial vasculitis. A common challenge for practitioners is distinguishing SSLR from similar dermatoses, particularly urticarial multiforme (UM), which some experts consider clinically related to SSLR. Despite the cutaneous similarities of UM and SSLR, including urticarial plaques with an associated central duskiness, SSLR tends to have a more delayed onset following offending agent exposure and more extracutaneous symptoms, especially arthralgias and/or arthritis, lymphadenopathy, and higher fevers.15 The rash of UM classically presents 1-3 days following agent exposure or illness, whereas SSLR presentation is delayed 1-3 weeks. Further distinguishing UM is the transient nature of the individual lesions, each lasting less than 24 hours.

Urticarial vasculitis (UV), morphologically similar to SSLR and UM, causes persistent urticarial-like plaques that last longer than 24-48 hours and resolve with bruising. Biopsy results revealing leukocytoclastic vasculitis distinguish UV, but case reports exist reporting leukocytoclastic vasculitis in association with SSLR.

Erythema multiforme (EM), a hypersensitivity reaction usually triggered by infections (most commonly herpes simplex virus), also may appear morphologically similar to SSLR. These lesions also persist for longer than 24-48 hours and often have a target appearance with central duskiness that sometimes can blister. Patients may have mucosal involvement with vesicles and erosions, compared with patients with SSLR in whom mucosal lesions are rarely seen. Medications are an uncommon trigger for EM, occurring in less than 10% of cases, and alternative drug eruptions including SSLR should be excluded prior to diagnosis.

Other disorders commonly presenting with similar extracutaneous manifestations to SSLR and concomitant dermatitis were further excluded based on the morphologic appearance of the lesions and other clinical dissimilarities. Henoch-Schönlein purpura, which also may present with arthralgia, fever, GI symptoms, and extremity edema, was unlikely given the urticarial appearance of the lesions, rather than palpable purpura. Furthermore, the arthritis/arthralgia of Henoch-Schönlein purpura is typically oligoarticular, affecting the large joints of the lower extremities most frequently.

If the patient presents with persistent fever for more than 5 days, Kawasaki disease may be considered in the differential and ruled out with clinical and laboratory assessment. The presence of fever, lymphadenopathy, and acute rash similarly should prompt consideration of a clinical and laboratory work-up for drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Morphologically, this drug reaction is characterized by a maculopapular eruption more than 3 weeks after exposure to an offending agent. Patients with SSLR respond favorably to cessation of the causative drug and supportive care with antipyretics, NSAIDs, and antihistamines. The cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations of this drug reaction typically disappear within 2-3 weeks after discontinuation of the offending agent. If symptoms are severe, a short systemic corticosteroid course may be warranted. Our patient’s symptoms completely resolved within 2-3 weeks of discontinuing amoxicillin therapy.

Dr. Matiz is assistant professor of dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Waldman is a clinical research fellow at the hospital. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. von Pirquet, C. Frh, and Bela Schick. “Serum Sickness.” Translated by B. Schick. (London: Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, 1951).

2. Cutis. 2002 May;69(5):395-7.

3. J Pediatr. 1994 Nov;125(5 Pt 1):805-11.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991 Nov;25(5 Pt 1):805-8.

5. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003 Dec;39(9):677-81.

6. Ann Pharmacother. 1996 May;30(5):481-3.

7. J Hosp Med. 2011 Apr;6(4):231-2.

8. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014 Mar;6(2):183-5.

9. Ann Pharmacother. 2004 Apr;38(4):609-11.

10. Ann Pharmacother. 2000 Apr;34(4):471-3.

11. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013 Sep;19(6):360.

12. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012 Feb;15(1):e6-7.

13. Am J Med Sci. 2013 May;345(5):412-3.

14. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007 Sep;26(3):179-87.

15. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013 Mar;6(3):34-9.

BY CATALINA MATIZ, MD, AND ANDREA WALDMAN, MD

Serum sickness

How does serum sickness–like reaction present?

At the time of initial evaluation, the patient presented with a recent history of fever, edema of the hands and feet, limited gait, and a diffuse, persistent serpiginous and annular dermatitis for 48 hours. Of note, the patient was prescribed a 10-day course of amoxicillin for otitis media 8 days prior to initial presentation.

The distribution and morphology of our patient’s cutaneous eruption, in combination with the systemic symptoms, facial and acral edema, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia, were highly suggestive of serum sickness–like reaction (SSLR). SSLR is an allergic reaction characterized by a cutaneous eruption, arthralgias, fever, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, and malaise. True serum sickness was originally distinguished in 1905 as a self-limited illness that occurred in several patients after administration of equine diphtheria antitoxin.1 Today this reaction is rarely noted in the pediatric population.

Pathogenically, true serum sickness represents a type III arthus hypersensitivity reaction to proteins in toxins or drugs, mediated by circulating antigen-antibody complexes. In contrast, SSLR is not associated with circulating immune complexes or hypocomplementemia.2 Histopathology frequently resembles the findings of urticaria, including a perivascular and dermal inflammatory infiltrate with associated neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes.2 Several hypotheses concerning the etiology of SSLR have been suggested in the literature, most commonly including an inflammatory response to defective drug metabolism. However, definitive pathology remains unknown.3

Initially, an urticarial rash and low-grade fever typically develop 7-21 days after exposure to the offending agent or sooner in individuals previously sensitized to the drug. The lesions quickly evolve to the classic purpuric lesions of SSLR over the following 24-48 hours. These dermatologic findings include pink to red oval and/or polycyclic lesions with large central areas of purple discoloration, classically involving the trunk, extremities, and/or face. The lesions may be discrete, scattered, or confluent.2

Several medications are associated with SSLR, but cefaclor is most frequently implicated, occurring in 0.2% of treated children.4,5 Other common culprits include penicillins, tetracycline, sulfonamides, macrolides, ciprofloxacin, rifampin, griseofulvin, bupropion, and fluoxetine.6-10 More recently, biologic agents have been implicated in SSLR, including rituximab, efalizumab, and infliximab.11,12 SSLR also has been described in association with immunizations (hepatitis B, tetanus, and rabies) and active infections with hepatitis B or C.13,14

The diagnosis of SSLR is primarily clinical, formulated based on the constellation of characteristic lesions, fever, adenopathy, facial edema, and/or arthralgia in conjunction with recent history (within 7-21 days) of offending medications or agents. Supporting laboratory findings include normal or mildly low complement C3 and C4 levels and mild proteinuria. Abnormalities in liver and renal function test results are rare, in contrast to true serum sickness. Biopsy and histopathology may be utilized to exclude other diagnoses.2

An extensive variety of cutaneous conditions bearing a resemblance to SSLR were considered in the differential, including urticaria multiforme, Kawasaki disease, erythema multiforme, and urticarial vasculitis. A common challenge for practitioners is distinguishing SSLR from similar dermatoses, particularly urticarial multiforme (UM), which some experts consider clinically related to SSLR. Despite the cutaneous similarities of UM and SSLR, including urticarial plaques with an associated central duskiness, SSLR tends to have a more delayed onset following offending agent exposure and more extracutaneous symptoms, especially arthralgias and/or arthritis, lymphadenopathy, and higher fevers.15 The rash of UM classically presents 1-3 days following agent exposure or illness, whereas SSLR presentation is delayed 1-3 weeks. Further distinguishing UM is the transient nature of the individual lesions, each lasting less than 24 hours.

Urticarial vasculitis (UV), morphologically similar to SSLR and UM, causes persistent urticarial-like plaques that last longer than 24-48 hours and resolve with bruising. Biopsy results revealing leukocytoclastic vasculitis distinguish UV, but case reports exist reporting leukocytoclastic vasculitis in association with SSLR.

Erythema multiforme (EM), a hypersensitivity reaction usually triggered by infections (most commonly herpes simplex virus), also may appear morphologically similar to SSLR. These lesions also persist for longer than 24-48 hours and often have a target appearance with central duskiness that sometimes can blister. Patients may have mucosal involvement with vesicles and erosions, compared with patients with SSLR in whom mucosal lesions are rarely seen. Medications are an uncommon trigger for EM, occurring in less than 10% of cases, and alternative drug eruptions including SSLR should be excluded prior to diagnosis.

Other disorders commonly presenting with similar extracutaneous manifestations to SSLR and concomitant dermatitis were further excluded based on the morphologic appearance of the lesions and other clinical dissimilarities. Henoch-Schönlein purpura, which also may present with arthralgia, fever, GI symptoms, and extremity edema, was unlikely given the urticarial appearance of the lesions, rather than palpable purpura. Furthermore, the arthritis/arthralgia of Henoch-Schönlein purpura is typically oligoarticular, affecting the large joints of the lower extremities most frequently.

If the patient presents with persistent fever for more than 5 days, Kawasaki disease may be considered in the differential and ruled out with clinical and laboratory assessment. The presence of fever, lymphadenopathy, and acute rash similarly should prompt consideration of a clinical and laboratory work-up for drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Morphologically, this drug reaction is characterized by a maculopapular eruption more than 3 weeks after exposure to an offending agent. Patients with SSLR respond favorably to cessation of the causative drug and supportive care with antipyretics, NSAIDs, and antihistamines. The cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations of this drug reaction typically disappear within 2-3 weeks after discontinuation of the offending agent. If symptoms are severe, a short systemic corticosteroid course may be warranted. Our patient’s symptoms completely resolved within 2-3 weeks of discontinuing amoxicillin therapy.

Dr. Matiz is assistant professor of dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Waldman is a clinical research fellow at the hospital. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. von Pirquet, C. Frh, and Bela Schick. “Serum Sickness.” Translated by B. Schick. (London: Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, 1951).

2. Cutis. 2002 May;69(5):395-7.

3. J Pediatr. 1994 Nov;125(5 Pt 1):805-11.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991 Nov;25(5 Pt 1):805-8.

5. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003 Dec;39(9):677-81.

6. Ann Pharmacother. 1996 May;30(5):481-3.

7. J Hosp Med. 2011 Apr;6(4):231-2.

8. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014 Mar;6(2):183-5.

9. Ann Pharmacother. 2004 Apr;38(4):609-11.

10. Ann Pharmacother. 2000 Apr;34(4):471-3.

11. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013 Sep;19(6):360.

12. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012 Feb;15(1):e6-7.

13. Am J Med Sci. 2013 May;345(5):412-3.

14. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007 Sep;26(3):179-87.

15. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013 Mar;6(3):34-9.

Make the diagnosis

The day prior to presentation, the family took the patient to the ED for evaluation of the lesions and concomitant swelling of the face, eyelids, hands, and feet, as well as fever and irritability. The ED discharged the patient after comprehensive examination and arranged follow-up in the dermatology clinic the following day. Review of systems further revealed limited gait. Parents denied any recent travel or pets residing in the home. Family history is noncontributory.

Physical exam

The patient is a well-appearing toddler, who is in no acute distress but is irritable. Patient is afebrile, with a temperature of 99.5°F, and vital signs are within normal limits. On skin examination, there are serpiginous and annular confluent erythematous urticarial plaques with a central ecchymotic discoloration over the eyes, peripheral malar distribution, neck, chest, abdomen, back, buttock, extremities, hands, and feet. There is notable eyelid, hand, and feet edema. There was no mucosal involvement. The patient has posterior cervical lymphadenopathy but no hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. The patient refused to walk.

Effect of Non–Insulin-Based Glucose-Lowering Therapies on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes

While type 2 diabetes (T2D) is commonly seen in primary care, it is difficult to control successfully over time. This series offers brief eNewsletters written by clinical experts that are designed to assist in the clinical management of patients with T2D.

This fourth eNewsletter in the series, entitled Effect of Non–Insulin-Based Glucose-Lowering Therapies on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes, was written by Szymon L. Wiernek, MD, PhD, and Matthew A. Cavender, MD, MPH. It presents an overview of commonly used non–insulin-based glucose-lowering drugs in the context of cardiovascular disease risk. The basic mechanisms of action for each pharmacotherapeutic class and the effects of these medications on cardiovascular events are discussed so that physicians can make informed treatment decisions

Click here to read the supplement

Department of Medicine University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, NC

Department of Medicine University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, NC

While type 2 diabetes (T2D) is commonly seen in primary care, it is difficult to control successfully over time. This series offers brief eNewsletters written by clinical experts that are designed to assist in the clinical management of patients with T2D.

This fourth eNewsletter in the series, entitled Effect of Non–Insulin-Based Glucose-Lowering Therapies on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes, was written by Szymon L. Wiernek, MD, PhD, and Matthew A. Cavender, MD, MPH. It presents an overview of commonly used non–insulin-based glucose-lowering drugs in the context of cardiovascular disease risk. The basic mechanisms of action for each pharmacotherapeutic class and the effects of these medications on cardiovascular events are discussed so that physicians can make informed treatment decisions

Click here to read the supplement

Department of Medicine University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, NC

Department of Medicine University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, NC

While type 2 diabetes (T2D) is commonly seen in primary care, it is difficult to control successfully over time. This series offers brief eNewsletters written by clinical experts that are designed to assist in the clinical management of patients with T2D.

This fourth eNewsletter in the series, entitled Effect of Non–Insulin-Based Glucose-Lowering Therapies on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes, was written by Szymon L. Wiernek, MD, PhD, and Matthew A. Cavender, MD, MPH. It presents an overview of commonly used non–insulin-based glucose-lowering drugs in the context of cardiovascular disease risk. The basic mechanisms of action for each pharmacotherapeutic class and the effects of these medications on cardiovascular events are discussed so that physicians can make informed treatment decisions

Click here to read the supplement

Department of Medicine University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, NC

Department of Medicine University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, NC

When Should Neurologists Discontinue Disease-Modifying Treatments in Patients With MS?

NEW ORLEANS—Discontinuation of disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) may be considered for patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) age 55 or older with ongoing progression and no clinical relapses or new MRI lesions consistent with MS in the previous five years, according to research presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Consortium of MS Centers. Data from the study also suggest that it is reasonable to consider discontinuing DMTs for patients in the same age range with stable relapsing remitting (RR) MS who have had no clinical relapses or new MRI lesions consistent with MS in the previous five years.

Although DMTs can reduce relapse rates and progression of disability early in the course of RRMS, it remains unknown whether these treatments maintain efficacy late in the course of RRMS, in SPMS, or in older patients. Considerations for discontinuing treatment include potential inefficacy of DMTs and adverse effects in this cohort, said the authors.

Devyn Parsons, a medical student at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, working with Anthony Traboulsee, MD, and colleagues, conducted a systematic search to examine literature relevant to the discontinuation of DMTs and to provide guidance about when DMTs may be discontinued. The investigators used the keywords “multiple sclerosis,” “disease modifying treatments,” “treatment withdrawal,” “stopping medication,” and “medication withdrawal” to search PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The search included articles up to June 2016 and was limited to English-language publications.

The review yielded what Ms. Parsons described as a “paucity of information.” The investigators found evidence that disease activity in RRMS declined with increasing age and longer disease duration. Some observational studies suggested that older patients who continuously receive DMT and are free of disease activity for several years might be good candidates for discontinuation of DMTs. Since DMTs are associated with adverse events that may affect quality of life or pose serious safety risks, it is important to consider patient preference, said the authors.

Safety monitoring following discontinuation of DMTs should include annual clinical assessment and annual brain MRIs for two to five years, with consideration of reinitiation of DMTs if evidence of new clinical relapse emerges or more than two new MRI lesions consistent with MS appear, said the researchers.

This study was supported by Sanofi Genzyme.

NEW ORLEANS—Discontinuation of disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) may be considered for patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) age 55 or older with ongoing progression and no clinical relapses or new MRI lesions consistent with MS in the previous five years, according to research presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Consortium of MS Centers. Data from the study also suggest that it is reasonable to consider discontinuing DMTs for patients in the same age range with stable relapsing remitting (RR) MS who have had no clinical relapses or new MRI lesions consistent with MS in the previous five years.

Although DMTs can reduce relapse rates and progression of disability early in the course of RRMS, it remains unknown whether these treatments maintain efficacy late in the course of RRMS, in SPMS, or in older patients. Considerations for discontinuing treatment include potential inefficacy of DMTs and adverse effects in this cohort, said the authors.

Devyn Parsons, a medical student at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, working with Anthony Traboulsee, MD, and colleagues, conducted a systematic search to examine literature relevant to the discontinuation of DMTs and to provide guidance about when DMTs may be discontinued. The investigators used the keywords “multiple sclerosis,” “disease modifying treatments,” “treatment withdrawal,” “stopping medication,” and “medication withdrawal” to search PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The search included articles up to June 2016 and was limited to English-language publications.

The review yielded what Ms. Parsons described as a “paucity of information.” The investigators found evidence that disease activity in RRMS declined with increasing age and longer disease duration. Some observational studies suggested that older patients who continuously receive DMT and are free of disease activity for several years might be good candidates for discontinuation of DMTs. Since DMTs are associated with adverse events that may affect quality of life or pose serious safety risks, it is important to consider patient preference, said the authors.

Safety monitoring following discontinuation of DMTs should include annual clinical assessment and annual brain MRIs for two to five years, with consideration of reinitiation of DMTs if evidence of new clinical relapse emerges or more than two new MRI lesions consistent with MS appear, said the researchers.

This study was supported by Sanofi Genzyme.